#aššurism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

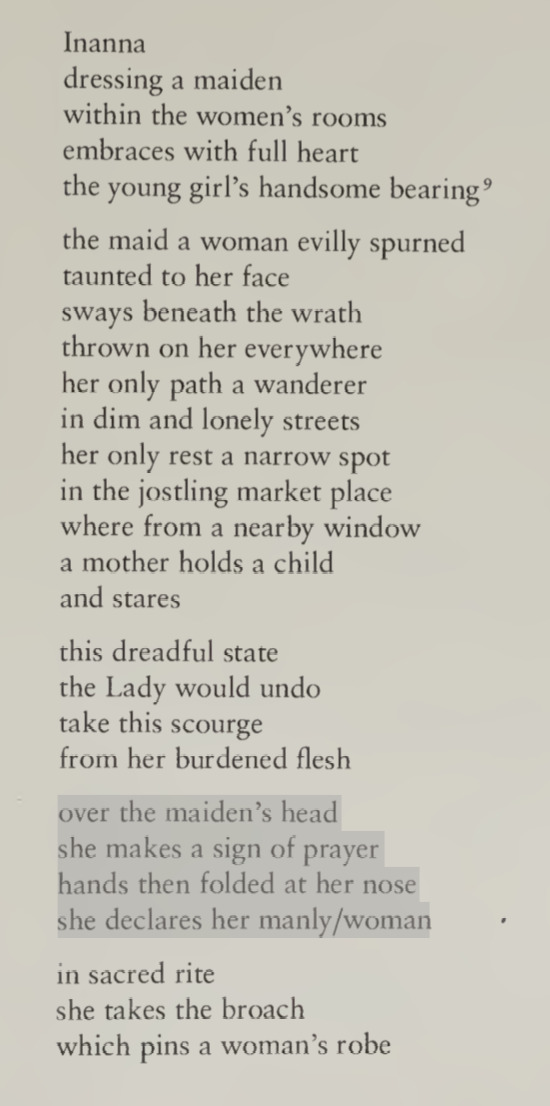

from Lady of the Largest Heart, a poem by High Priestess Enheduanna & translated by Betty De Shong Meador.

#m.#inanna#ishtar#enheduanna#aššurism#mesopotamian polytheism#trans theology#trans paganism#transmasc#transfem

902 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aššur, god of the city of Aššur ⛰️

Aššur iconography can be a little elusive. Some depictions alongside Neo-Assyrian kings show what looks like to me like a winged mountain god with a bow and arrow.

I chose osprey details out of pure vibes. Ospreys are native to the area and it makes sense that, if he’s a bird, he’s probably a bird that enjoys high places (large cliff I mean mountain!) and enjoys a good fish out of the river beside his cliff. Osprey markings look nice, too.

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#assur#aššur#assyrian#assyrian mythology#mesopotamia#mesopotamian mythology#mesopotamian gods#assyrian gods#ashur#when you and your city are named the same thing#which assur are we talking about? the city or the god? maybe it’s both

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great find!

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw you have a link in your pinned post about where to start with hellenic polytheism. Do you have anything like that for Sumerian polytheism?

Unfortunately no, I never had the energy to make one that intense for Sumerian. So here is the best I can do now. Revivalist Perspective.

I used "Mesopotamian" over Sumerian here because research cannot be parsed out to "just Sumerian" it will always include Akkadian and all time periods. However, in this post, when it comes to Gods, I am discussing their role in the Sumerian pantheons. Not later Akkadian with Babylonian Marduk or Assyrian Aššur as king. "Mesopotamian Religion" is kind of a misnomer, there were multiple religions, pantheons, and related but distinct cultures. These are usually broken up in academia based on time period for example Ur III vs Neo-Assyrian; by city Uruk vs Isin; and by the ruling "ethnic group" such as Amorites vs the Kassites. It is a maze of information, you don't have to be concerned about it in the beginning but I just wanted to mention that there is a large variety of religious traditions.

Diĝir Sumerian for God/Goddess. Diĝirene is plural.

🌾 To begin I suggest:

Learn a bit, even just reading Oracc's information, on the Diĝir.

Get some water (or other drink, especially beer) for them.

Offer them up some words of praise, tell them the liquid is for them.

"Holy An, Unalterable Decision Maker, Who Determines The Place of all Diĝir. May this water show my reverence for your power."

Pour the water out.

Tah dah you worshiped a Diĝir.

Now go learn some more.

Rinse repeat adding to your worship as you learn.

Practicing and learning can be side by side events, doing both at once.

Your research doesn't need to be academically intense like your taking a course. Go at your own pace when researching information, and don't force yourself to read things you won't understand. But don't neglect it either it's still important to learn, especially about the Diĝirene themselves.

Don't fear making mistakes. If you do something you think is a mistake simply say sorry and give a libation, that is enough. Thus don't be afraid to start despite little knowledge — the Diĝirene will not be mad at you so long as you are a sincere worshipper.

🌾 Learning

Use a combination of Frayne, Black, Leick's dictionaries and Oracc to learn about a specific Diĝir (linked below). Sources will conflict with each other. This can be due to multiple reasons: publication timing & something being out of date; differences of opinions/interpretations of the academics; differences in translations by academics; and honestly I think Assyriologists just enjoy fighting each other...that is only half a joke.

In other words, be willing to combine the things you learn into your own composite view of information on any Diĝir. Actually basically any topic in Mesopotamia.

My Post on Resources for Researching — Link

Some tips:

Make sure it's a reliable source. Vetting sources — Link

Focus on academics of various disciplines especially Assyriologists; but also archeologists; anthropologists specializing in that region; historians whose topic is related.

Websites specifically designed for Mesopotamian History by academics / academic institutions.

Check the publication date. If the date is newer it probably is more accurate. Unless the concept is 100% novel, in which case they will usually explain why this new interpretation is more accurate.

Use three sources. If source A and B conflict. Search for source C and see if it agrees with A or B. ... sometimes it'll agree with neither.

Being real for a second as a worshipper: sometimes something from an academic will just resonate with you and sometimes it just won't. For example Jacobsen's view of Inana did (link); while Boterro's view of religion lacking love did not (link). Despite both being Assyriologists.

Links to Dictionaries, Websites, Online Books etc — Link

Not available online but I highly suggest:

A Handbook To Life in Ancient Mesopotamia by Stephen Bertman 2005 for general Mesopotamian history — Google Books 43 pages available

Introduction to Ancient Mesopotamian Religion by Tammi Schneider 2011 — Google Books 33 pages available

Both are written for the average reader not academically thick.

❗️If you can't do a lot of research for whatever reason (disability, education level, access to information etc) then I suggest reading Jeremy Black's dictionary cover to cover like a book. Some info is outdated, but if it's all you can manage it's a good way to have a base of knowledge for your practice.

For more information about learning see the part about Inana below.

🌾 Prayer & Praise

In Mesopotamian cultures giving praise to a Diĝir is important. Period. Even if it's "you're awe inspiring" or something else simple.

For prayers you can say what you feel comfortable with in the moment, you can write your own, you can adapt from the ETCSL or other reliable translations. I suggest reading through the ETCSL hymns or other reliable translation to get a feel for how the Diĝirene were praised even if you don't use those hymns directly.

Something specifically about that Diĝir, or lines taken from the ETCSL hymns to that Diĝir, add an extra touch to show your appreciation for them in my opinion.

Based on artwork praying position was either hands up, bent at the elbow so hands are level with your shoulders, and palms facing outwards. Or hands clasped together at your sternum. The first one is easier if you have a cup in your hand.

ETCSL Hymns — Link

How to end Mesopotamian prayers — Link

Prayer to a personal Diĝir adapted from ETCSL, can be replaced with a named Diĝir — Link

🌾 Offerings & Libations

I do not have a historical example of a Mesopotamian libation or offering incantation or prayer so I use the steps I outlined in the first section.

Say a prayer, designate the offering as for that Diĝir/Diĝirene then:

Any libations should be poured out and made "unrecoverable"

Food is eaten

Objects offered can either be used or set aside on an altar/shrine.

Incense is lit and let burn to the end if possible.

Mesopotamian Offerings — Link

Historical Incense — Link

Low Spoon / No Spoon offerings — Link

🌾 Altar / Shrine

The most important thing to Mesopotamian religious cult was the animated cult statue. While you don't need an altar/shrine I do suggest having a spot for them with a representation if you can. The Word Cult — Link

There were also street shrines located in the city for the average (acceptable) citizen to use, but I don't know anything about them except that they existed. So I stick to what is known about temple cults.

The representation doesn't have to be a statue it could be anything so long as it is chosen thoughtfully, is clean, and specifically set aside as a representation for them not used for anything else. For example for me: Gibil is a candle, Dumuzid is beads, Ninazu is a pendant, Damu is a snake ring that I will not wear... so on.

Assuming you don't have to worry about being secret: Put the representation in a clean spot, and you would add something like an incense holder to light some (alternatively a good smelling candle), or a bowl/cup to use for libations.

Again, this isn't absolutely necessary. However, with the importance of temples and cult statues in Mesopotamian history, combined with the fact that we don't have a dedicated priesthood at a temple in our cities/towns to diligently worship the Gods, I think its a good way to adapt a very important aspect of the religion to the modern world.

There is no difference between altar vs shrine. The Sumerian dictionary gives 18 results for "shrine" and 2 results for "altar." So usage of those words is defined by yourself.

🌾 Good Diĝir to Start With

An — Sky, Heaven, Highest Authority. He received some worship, but importantly he was frequently invoked in the worship of other Diĝirene. For example, Inana is made significantly important by An's power. He might be a good stepping stone to give your first libations to if you really don't know where to start, since he is the highest of them all and gave them their authority. His symbol 𒀭 was the divine marker in cuneiform; written at the beginning of (almost) all divine names.

Enlil — King of Gods. Since he is literally king I suggest worshipping him along side an intercessor Diĝir such as his wife Ninlil or sukkal Nuska. Then again that advice could go for any high ranking Diĝir.

Enki — He is significantly more involved with humanity than An or Enlil is. He is usually the Diĝir willing to help humans in myth (like the flood myths), or willing to help other Diĝir that have deemed unworthy of help (like Inana in her descent myth). In one myth he is also the Diĝir who brings order to the world. He is also in some ways the source of life as he is fresh water.

Utu — The Sun and Justice

Nanna/Suen — The Moon and Cycles (time, the tides, etc); also fertility of cows.

Iškur — Storm God

Gula — Goddess of Health

Inana — See below.

Dumuzid* — [Edit] Shepherd, Milk, Agriculture, Spring Vegetarian, (later) Power of Grain

*Treasures of Darkness by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Chapter 1 is a very good resource for this, even if his opinions on Inana are not always agreed upon, I have found his conclusions on "Dying Gods of Fertility" to be accepted in academic literature — Google Books [Edit] I messed up with wording and used "Dying and Rising God" which is an archetype idea proposed by James Frazer in 19th century and his iteration of this concept is rejected. I meant to write what Jacobsen uses "Dying God of Fertility" which discusses his death and possible return outside Frazer's archetype framework and based on an amalgamation of different local cultus and ancient texts. Frayne's Dictionary p 75-77 is also a good overview of his roles.

🌾View of The Diĝirene

A pantheon of over three thousand gods seems too large to consist solely out of distinct, well defined natural and cultural agents, and in fact it didn't. The most important agencies are covered by a relatively small and stable core pantheon of some ten to twenty deities of nature, in the texts summarized as the seven or twelve "Great Gods". These few great gods, the ones that "determine destiny", constitute an overarching national pantheon, while the many lesser gods, the "gods of the land", head local city panthea, or serve the courts of the great gods in specialized functions: spouse, child, vizier, herald, deputy, messenger, constable, singer, throne, weapon, ship, or harp. — The Mesopotamian Pandemonium by Frans Wiggerman Link

There are many more Diĝir, even extremely important ones. Those I listed are very straight forward in my opinion and thus good options for someone just beginning. Except perhaps Dumuzid where I messed up.

In Mesopotamian Religions we are not equal to the Diĝirene we are below them, that is undisputed. Unless you are an Ur III king... and even then those divine Kings were below the cosmic Diĝir.

Serving the Gods was of high importance. My opinion, based on ancient texts, about how modern individuals can "serve the Gods" without temples, theocracy, or religious tax etc is to maintain 'The Order' — Link.

While Mesopotamians feared their Gods I don't suggest adding that into your religious mindset until you can really understand it and divorce it from anxiety, self-esteem, self-doubt, trauma, etc— which I doubt is easy.

The important part is: their love is not unconditional for example you could lose their favor if: you cheat on your partner, snub the poor, or purposely try to curse a God (which occasionally happens on TikTok). Additionally, they embody the forces of nature including destruction.

You can lament to them about dire situations and seek their help and guidance; lamentation is said to sooth their hearts. But again divorce this from "Gods are mad at me"

🌾 A Word About Inana

Usually spelled Inanna, I use ETCSL proper noun spelling. She probably has the most available information but also the most misinformation unfortunately. Straight up disinformation as well in my opinion.

She was a Goddess that spread far and wide geographically and is found in basically every time period of Mesopotamian history, and spread to many neighboring cultures. She absorbed many local Goddesses and covered many aspects of life, depending on which culture, location, and time. Most well known for fertility, love/lust, great power, and war.

While she is a very utilitarian Goddess, I only suggest starting with her if you know how to parse out the disinformation and misinformation spread about her. Which can be done but it will take a bit more diligence when researching.

Good ways to do that:

🔹Stick to academic sources where the author is an Assyriologist or historian in a related field like ancient literature or archeology.

Good book specifically for her would be Ishtar by Louise M Pyrke (2017) Google Books 57 Pages Available

If you're willing to learn about numerous Goddesses at the same time the book: Goddesses in Context by Julia Asher-Greve and Joan Goodnick Westenholz (2013) PDF Book Full

Do not use neo-pagan, new age, occult, witchcraft, by polytheists-for-polytheist, books about her.

Don't use books written by Jungian Analysts. My beef with them is A.) Jungian archetypes specifically are inherently Euro-centric western and try to shove all world cultures into them. B.) Every single piece of information on Mesopotamia I have ever read from these authors is always inaccurate C.) Education/Degree/License as a Jungian Analyst is not an academic credential for Ancient Mesopotamian resources. | If you work with archetypes in your religion that is up to you, but as sources of accurate information these authors are not useful.

People often try to find sources on a singular Mesopotamian God, but thats very uncommon. If you want to learn about any Diĝir in-depth you will end up reading articled and books on a variety of ancient religious topics.

🔹Utilize translations by academics not other sources:

ETCSL Inana Entries: Inana Myth — Link • Inana & Dumuzid Myth — Link • Hymns to Inana — Link • Hymns to Inana & Dumuzid — Link

The Harps that Once by Jacobsen (1987), Google Books 109 Pages Available

Enheduana by Sophus Helle (2023), Google Books 58 Pages Available. Companion Website Link, he offers up other translations for the same compositions too.

Not Inanna Queen of Heaven and Earth by Diane Wolkstein. A good story but not fully faithful to the ancient story as it shoves compositions together leaving out entire sections of those compositions. It then presents those 3 hacked up compositions as if they were one story and changes the meaning of some. All of the actual compositions are available on the ETCSL in order of how she used them: Inana-Dumuzid A 4.08.01; Dumuzid and Enkimdu 4.08.33; Dumuzid-Inana I 4.08.09. Her "Introduction" barely goes a sentence without misinformation.

Not Lady of The Largest Heart by Betty De Shong Meador, no translator credentials. Shes also a Jungian Analyst.

Nor anyone else that doesn't have direct credentials to translate Sumerian or Akkadian.

.▪️.

I hope this is helpful in some way.

-Dyslexic, not audio proof read-

#polytheism#paganism#landof2rivers#sumerian#mesopotamian#mesopotamia#sumerian polytheism#mesopotamian polytheism#religion#polytheist revivalism#inanna

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Naqiʾa (c. 730– 668 BCE), wife of Sennacherib (705– 681), mother of the Neo- Assyrian king Esarhaddon (681– 669) and grandmother of Ashurbanipal (668– 627), is the best documented and in all probability most influential royal woman of the Neo- Assyrian period.

It was often suggested that Naqiʾa was the driving force behind Sennarcherib’s installment of Esarhaddon as crown prince. This was a truly exceptional case, as Esarhaddon was one of Sennacherib’s younger sons and most probably, even as a young man, suffered from an illness that would later kill him. Sickness was often interpreted as a sign of divine wrath in Mesopotamia; therefore, it was a severe obstacle for a claimant to the throne and any sickness of the king could be used to question his status as the darling of the gods. Maybe we will never know what the reasons for Esarhaddon’s promotion were, but we are sure about the results of Sennacherib’s decision.

Sennacherib was assassinated by his other sons and Esarhaddon had to fight his brothers in order to be enthroned. While the rebellion was going on, Naqiʾa explored the future of her son by asking for prophetic messages, something that was usually a privilege of the kings. The answer highlights the role of Ishtar, here called the Lady of Arbela, and the privileged position, of Naqiʾa:

I am the Lady of Arbela! To the king’s mother, since you implored me, saying: “The one on the right and the other on the left you have placed in your lap. My own offspring you expelled to roam the steppe!” No, king, fear not! Yours is the kingdom, yours is the power! By the mouth of Aḫat- abiša, a woman from Arbela.

Seemingly, the prophecy was right: it took Esarhaddon only two months to defeat his brothers and he was enthroned as Assyrian king. In this text Naqiʾa is already designated as queen mother; according to Melville this was “the highest rank a woman could achieve.”

In earlier research Naqiʾa was often seen as the strong woman behind a weak, sick, and superstitious king. Newer research has demonstrated that despite all of his problems, Esarhaddon was a capable ruler, who brought the Neo-Assyrian Empire to its maximal extension and pacified Babylonia, at least for a while.

During his reign Naqiʾa became really powerful and commissioned her own building inscription. To undertake large building projects and praise them in inscriptions is typical for kings, but extraordinary for a royal woman. The inscription introduces Naqiʾa in a bombastic tone, which is quite typical for inscriptions commissioned by kings:

I, Naqiʾa … wife of Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria, daughter- in- law of Sargon [II], king of the world, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of the world [and] king of Assyria; the gods Aššur, S.n, Šamaš, Nab., and Marduk, Ištar of Niniveh, [and] Ištar of Arbela … He [Essarhaddon] gave to me as my lordly share the inhabitants of conquered foes plundered by his bow. I made them carry hoe [and] basket and they made bricks. I … a cleared tract of land in the citadel of [the city of] Nineveh, behind the temple of the gods Sîn and Šamaš, for a royal residence of Esarhaddon, my beloved son …

We can clearly see that Naqiʾa held an extraordinarily powerful position during the reign of her son and this continued even after Esarhaddon’s death. She was eager to assure the enthronement of her grandson Assurbanipal. The loyalty treaty that was intended to secure his reign is called the treaty of Zakutu, another name of Naqiʾa. Its first lines read:

The treaty of Zakutu, the queen of Sannacherib, king of Assyria, mother of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, with Šamaš- šumu- ukin, his equal brother, with Šamaš- metu- uballiṭ and the rest of his brothers, with the royal seed, with the magnates and the governors, the bearded and the eunuchs, the royal entourage, with the exempts and all who enter the Palace, with Assyrians high and low: Anyone who (is included) in this treaty which Queen Zakutu has concluded with the whole nation concerning her favorite grandson Assurbanipal […]

That Naqiʾa was able to conclude a treaty with the most powerful persons throughout the empire and to establish her favorite grandson on the throne is clear evidence for her powerful position, even if she simply continued the plans she had made earlier with Esarhaddon. It seems that Naqiʾa died shortly after Assurbanipal was enthroned as king."

Fink Sebastian, “Invisible Mesopotamian royal women?”, in: The Routledge companion to women and monarchy in the ancient mediterranean world

#naqi'a#queens#ancient history#ancient world#history#women in history#mesopotamia#neo-assyrian empire#women's history#historical figures#8th century BC#7th century BC#assyria#middle-eastern history

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

fragment depicting a mountain goat | c. 800-601 BCE | aššur (modern-day iraq), neo-assyrian

in the staatliche museen zu berlin collection

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is sooooo funny. oh, you have something mean to say about poor ol' Israel? well what about Aššur-dān II, King of the Universe, who reigned in glory in the first millennium before christ?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The destruction of Elam was not the Holocaust, just as the Rwandan Genocide wasn’t the Holocaust or the Cambodian Genocide. The destruction of Elam wasn’t the Rwandan Genocide. The destruction of Elam wasn’t even the Assyrian destruction of Israel a century or so beforehand. The St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, the anti-Huguenot pogrom that killed between 5,000 and 20,000 people in France in 1572, differed meaningfully from the many anti-Jewish pogroms in the later Russian Empire. The Holocaust wasn’t the same as the Herero and Namaqua Genocide, the mass murder of indigenous people in what is now Namibia by the German Empire between 1904 and 1907, despite the fact that both were carried out by German authorities just a generation apart. Each of those incidents and campaigns of mass violence stands on its own. Their logic was different. They proceeded in different ways, with death tolls ranging from the dozens to the millions. Some were straightforward land grabs in which killing was incidental. Others were ideologically motivated campaigns of murder for which the groundwork had been laid for decades or centuries. Still others were the result of sudden explosions of ethnic or religious hatred against a background of oppression or conflict. But what ties them together, aside from the mass violence, is the fact that utterly ordinary people participated in all of them. It doesn’t take all that much for a baker from Aššur or a truck-driver from Hamburg to turn into a willing enslaver and killer, even a mass murderer who pulled a lethal trigger hundreds of times, under the right circumstances. If those in positions of authority tell them that it’s acceptable or even admirable, if they’re given the tools and the opportunity to do so, then even the most average people can commit horrifying acts.

-Patrick Wyman, Ordinary People Do Terrible Things

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Did ancient near east have any equivalent supernatural beings to nymphs

Overall not really, with small exceptions restricted pretty much just to Hittite Anatolia.

Jenniffer Larson in Greek Nymphs: Myth, Cult, Lore (p. 33) suggests the notion of nymphs - or rather of minor female deities associated specifically with bodies of water and with trees - was probably an idea which originated among early speakers of Indo-European languages. While I often find claims about reconstructed “PIE deities” and whatnot dubious, I think this checks out and explains neatly why despite being a vital feature of Greek local cults nymphs have little in the way of equivalents once we start moving further east.

Mesopotamian religion wasn’t exactly strongly nature-oriented. Overall even objects were more likely to be deified than natural features; for an overview see Gebhard J. Selz’s ‘The Holy Drum, the Spear, and the Harp’. Towards an understanding of the problems of deification in Third Millennium Mesopotamia. It should be pointed out that in upper Mesopotamia mountains were personified quite frequently, but mountain deities (Ebih is by far the most famous) are almost invariably male (Wilfred G. Lambert’s The God Aššur remains a pretty good point of reference for this phenomenon) Rivers are a mixed bag but in Mesopotamia the most relevant river deity was the deified river ordeal (idlurugu referred to both the procedure and the god personifying it), who was also male, and ultimately an example of a judiciary deity rather than deified natural feature. Alhena Gadotti points out that there is basically no parallel to dryads, and supernatural beings were almost never portrayed as residing in trees in Mesopotamia (‘Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld’ and the Sumerian Gilgamesh Cycle, p. 256). You can find tree deities like Lugal-asal (“lord of the poplar”) but there’s a decent chance this reflects originating in an area named after poplars and we aren’t dealing with something akin to a male dryad (also, Lugal-asal specifically fairly consistently appears in available sources first and foremost as a local Nergal-like figure).

All around, it’s safe to say there’s basically no such a thing as a “Mesopotamian nymph”. Including Hurrian evidence won’t help much either - more firmly male deified mountains, at least one distinctly male river, but no minor nature goddesses in sight.

Probably the category of deities most similar to nymphs would be various minor Hittite goddesses representing springs - Volkert Haas in fact referred to them as Quellnymphen (“spring nymphs”). Ian Rutherford (Hittite Texts and Greek Religion: Contact, Interaction, and Comparison, pp. 199-200) points out that the descriptions of statues of deities belonging to this class indicate a degree of iconographic overlap with nymphs in Greek art. Notably, in both cases depictions with attributes such as shells, dishes or jugs are widespread. There’s even a case of possibly cognate names: Hittite Kuwannaniya (from kuwanna, “of lapis lazuli”) and Kuane (“blue”) worshiped in Syracuse. They aren’t necessarily directly related though, since arguably calling a water deity “the blue one” isn’t an idea so specific it couldn’t happen twice.

There is also one more case which is considerably more peculiar - s Bronze Age Anatolian goddess seemingly being reinterpreted as a nymph by Greek authors: it is generally accepted that Malis, a naiad mentioned by Theocrtius, is a derivative of Bronze Age Maliya, who started as a Hittite craftsmanship goddess (she appears in association with carpentry and leatherworking, to be specific). There is pretty extensive literature on her and especially her reception after the Bronze Age, I’ve included pretty much everything I could in the bibliography of her wiki article some time ago. Note that there is no evidence the Greek interpretation of Maliya/Malis as a nymph was accepted by any inhabitants of Anatolia themselves. While most Bronze Age Anatolian deities either disappeared or remained restricted to small areas in the far east of Anatolia in the first millennium BCE, in both Lycia and Lydia there is quite a lot of evidence for the worship of Maliya. In both cases there is direct evidence for local rulers considering her a counterpart of Athena (presumably due to shared civic role and connection to craftsmanship; or maybe they simply aimed to emulate Athens). There’s even at least one instance of Maliya appearing in place of Athena in a depiction of the judgment of Paris (or rather, appearing in the guise of Athena, since the iconography isn’t altered).

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography:

Alchemy and the Occult:

Western:

Alchemy Unveiled, Johannes Helmond (Translated into English and Edited by

Gerard Hanswille and Deborah Brumlich); (1963)

Practical Alchemy, A Guide To The Great Work; Brian Cotnoir (2006)

The Black Arts (50th Anniversary Edition); Richard Cavendish (1968)

Alchemy & Mysticism: The Hermetic Cabinet; Alexander Roob (2009)

The Forge and the Crucible: The Origins and Structures of Alchemy (2nd Edition); Mircea Eliade (1962, 1978)

History of Alchemy; M. M. Pattison (1902)

Alchemy (Revised Edition); E. J. Holmyard (1990)

Dictionary of Symbolism, Cultural Icons and the Meanings Behind Them; Hans Biedermann, Translated by James Hulbert (1994)

The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft, and Wicca; Rosemary Ellen Guiley (1989)

The Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits; Rosemary Ellen Guiley (1992)

Levantine:

The Jewish Alchemists: A History and Source Book; Raphael Patai (1994)

Ancient Magic and Divination, A Microhistorical Study of the Neo-Assyrian Healer Kiṣir-Aššur; Troels Pank Arbøll (2017)

Fuck Your "Magic" Antisemitism: A Lesser Key To The Appropriation Of Jewish Magic & Mysticism; Ezra Rose (2022)

“His wind is released” - The Emergence of the Ghost Ritual of passage in Mesopotamia; Dina Katz, Leiden (2014)

Cursed Are You! The Phenomenology of Cursing in Cuneiform and Hebrew Texts; Anne Marie Kitz (2014)

Egyptian Magic; E.A. Wallis Budge (1901)

Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology (Cuneiform Monographs); David Brown (2000)

Astrology in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Science of Omens and the Knowledge of the Heavens; Michael Baigent (July 20, 2015)

Ancient Jewish Magic: A History; Gideon Bohak (2008)

PERFORMING DEATH: SOCIAL ANALYSES OF FUNERARY TRADITIONS IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST AND MEDITERRANEAN; Nicola Laneri, Ellen F. Morris, Glenn M. Schwartz, Robert Chapman, Massimo Cultraro, Meredith S. Chesson, Alessandro Naso, Adam T. Smith, Dina Katz, Seth Richardson, Susan Pollock, Ian Rutherford, John Pollini, John Robb, and James A. Brown (2007)

Mesopotamian Conceptions of Dreams and Dream Rituals; Sally A. L. Butler (1998)

Forerunners to Udug-Hul: Sumerian exorcistic incantations; Markham J. Geller (1985)

Šurpu. A Collection of Sumerian and Akkadian Incantations; Erica Reiner (1958)

Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts; F. A. M. Wiggermann (1992)

The Alchemist's Handbook- Manual for Practical Laboratory Alchemy; Frater Albertus (1960)

Licit Magic: The Life and Letters of al-Ṣāḥib b. ʿAbbād (d. 385/995); Maurice A. Pomerantz (09 Nov 2017)

Further Studies on Mesopotamian Witchcraft Beliefs and Literature; Tzvi Abusch (2002)

The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture; Francesca Rochberg (2004)

Greco-Roman:

Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook; Daniel Ogden (2002)

Far East Asia:

I Ching; Fu Xi (~1000 BCE)

Myths, Legends, Religious Texts And Folktales

Levantine:

The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion; Thorkild Jacobsen (1976)

Persian Myths; Jake Jackson (2022)

Myths of Babylon; Jake Jackson (2018)

The Epic Of Gilgamesh (2nd Edition); Anonymous, Andrew George (????, 2000)

The First Ghost Stories; Dr. Irving Finkel (2021)

On Jewish Folklore; Raphael Patai (1983)

Sumerian Mythology, a Deep Guide Into Sumerian History and Mesopotamian Empire and Myths; Joshua Brown (2021)

Sumerian Mythology, a Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C. (Revised Edition); Samuel Noah Kramer (1961)

Sumerian Liturgies; Anonymous, Stephen Langdon (1919)

Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart, Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna; Enheduanna, Betty De Shong Meador (1989)

Ninurta's Journey to Eridu; Daniel Reisman (1971)

A Sumerian Proverb Tablet in Geneva With Some Thoughts on Sumerian Proverb (2006)

Enki's Journey to Nippur: The Journeys of the Gods; Al-Fouadi, Abdul-Hadi A. (1969)

The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature by Rachel Bromwich (1991)

Encyclopedia of American Folklore; Linda S. Watts (2006)

Jewish Magic and Superstition: A Study in Folk Religion; Joshua Trachtenberg (1939)

Amulets and Talismans; E.A. Wallis Budge (The copy I have was published in 1992 but he died in 1934. Not sure when the original work was created.)

Ashkenazi Herbalism: Rediscovering the Herbal Traditions of Eastern European Jews; Deatra Cohen, Adam Siegel (2021)

Encyclopedia of Catholicism; Frank K. Flinn (2007)

As Through a Veil: Mystical Poetry in Islam; Annemarie Schimmel (1982)

You Will Have Other Goddesses in Addition to Me: Polytheism Among Ancient Israelite Women; Liora Finke (2022)

Gods That Travel: On The Ritual Aspects of Divine Journeys And Processions; Klaus Wagensonner (2014)

NINURTA AND ENKI; A new divine journey of the warrior god to Eridu; Klaus Wagensonner (2013)

Jewish Music in Its Historical Development; Abraham Zevi Idelsohn (1929)

The God Enki in Sumerian Royal Ideology and Mythology; Peeter Espak (2010)

The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic & Mysticism: Second Edition; Geoffrey W. Dennis (2007)

Book of Jewish Knowledge: An Encyclopedia of Judaism and the Jewish People, Covering All Elements of Jewish Life from Biblical Times to the Present (03 May 1948); Nathan Ausubel

Encyclopedia of Judaism (Encyclopedia of World Religions); Sara E. Karesh & Mitchell M. Hurvitz (2006)

Aboriginal Australia:

Gadi Mirrabooka: Australian Aboriginal Tales from the Dreaming; Pauline E. McLeod, Francis Firebrace Jones, June E. Barker, Helen F. McKay (2001)

The Two Rainbow Serpents Travelling: Mura Track Narratives from the 'Corner Country'; Jeremy Beckett, Luise Hercus (2009)

Mixed or Other:

Egyptian Myths & Tales; Japanese Myths & Tales, Aztec Myths & Tales, Scottish Folk & Fairytales, Viking Folk & Fairytales, Chinese Myths & Tales, Greek Myths & Tales, African Myths & Tales, Native American Myths & Tales, Persian Myths & Tales, Celtic Myths & Tales, Irish Fairy Tales; Anonymous, Flame Tree Publishing

Tales of King Arthur & The Knights Of The Round Table (Le Morte D’Arthur); Thomas Malory

The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore; Patricia Monaghan (2004)

Academic (Science including Psychology)

Stellar Alchemy: The Celestial Origin of Atoms, Michel Cassé, Stephen Lyle (2003)

Aboriginal Suicide Is Different: A Portrait of Life And Self Destruction; Colin Tatz (2005)

Fruit Domestication in the Near East; Shahal Abbo, Avi Gopher & Simcha Lev-Yadun (2015)

Astronomical Cuneiform Texts: Babylonian Ephemerides of the Seleucid Period for the Motion of the Sun, the Moon, and the Planets (Sources in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, 5); Otto E. Neugebauer (1945)

Studies in the History of Science; E. A. Speiser; Otto E. Neugebauer; Hermann Ranke; Henry E. Sigerist; Richard H. Shryock; Evarts A. Graham; Edgar A. Singer; Hermann Weyl (Compiled In 2017)

Studies in Civilization; Alan J. B. Wace; Otto E. Neugebauer; William S. Ferguson (Compiled In 2016)

Astronomy and History: Selected Essays; Otto E. Neugebauer (Compiled In 1983)

The Encyclopedia of the Brain and Brain Disorders; Carol Turkington (2002)

The Encyclopedia of Poisons and Antidotes; Deborah R. Mitchell & Carol Turkington (2010)

The Encyclopedia of Suicide; Glen Evans, Norman L. Farberow, Ph.D. & Kennedy Associates (1988)

Academic (History)

Western:

Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes; Carl Waldman (2006)

Levantine:

Sounds from the Divine: Religious Musical Instruments in the Ancient Near East; Dahlia Shehata (2014)

Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia: The Gilgamesh Epic and Other Ancient Literature; Rivkah Harris (05/12/2003)

House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia; A. R. George (1993)

The Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East; Michael Roaf (1990)

The Meaning of Color in Ancient Mesopotamia; Shiyanthi Thavapalan (2020)

The Loss of Male Sexual Desire in Ancient Mesopotamia; Gioele Zisa (2021)

Materials and Manufacture in Ancient Mesopotamia: The evidence of Archaeology and Art. Metals and metalwork, glazed materials and glass; P. R. S. Moorey (3/1/1985)

Collections; Bendt Alster, Takayoshi Oshima (2006)

Political Agency of Royal Women; Paula Sabloff (2019)

Studies in Sumerian Civilization: Selected Writings Of Miguel Civil; Miguel Civil, edited by Lluís Felu (2017)

A study on the natural heritage and its importance in the Sumerian civilization in southern Iraq; Al-Hussein Nabeel Al-Karkhi, Isam Hussain T. Al-Karkhi (2021)

A Sumerian Riddle Collection; Bendt Alster (1976)

SUMERIAN “CHILD”; Vitali Bartash (2018)

The civilizing of Ea-Enkidu an unusual tablet of the Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic; Andrew R George (2007)

Celibacy in the Ancient World: Its Ideal and Practice in Pre-Hellenistic Israel, Mesopotamia, and Greece; Dale Launderville OSB (07/01/2010)

House and Household Economies in 3rd Millennium B.C.E. Syro-Mesopotamia; Federico Buccellati ,Tobias Helms & Alexander Tamm (2014)

The Harps That Once… Sumerian Poetry In Translation; Thorkild Jacobsen (1987)

The Divine Origin Of The Craft Of The Herbalist; Sir E. A. Wallis Budge (1928)

Disease in Babylonia; Edited by Irving Finkel and Markham (Mark) Geller (2007)

Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia; Gianni Marchesi and Nicolo Marchetti (2011)

Myths of Enki, The Crafty God; Samuel Noah Kramer, John Maier (1989)

Household and State in Upper Mesopotamia; Patricia Wattenmaker (July 17, 1998)

Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium; Albert Kirk Grayson (1987)

Gudea's Temple Building: The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image (Cuneiform Monographs); Claudia E. Suter (January 1, 2000)

Reading Sumerian Poetry (Athlone Publications in Egyptology & Ancient Near Eastern Studies); Jeremy Black (2001)

Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia; Stephen Bertman (2002)

Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East; Amanda H. Podany (2022)

History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine Firsts in Recorded History; Samuel Noah Kramer (1981)

A History of the Animal World in the Ancient Near East; Edited by Billie Jean Collins (2002)

The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character; Samuel Noah Kramer (1963)

The Ancient Near East in Transregional Perspective: Material Culture and Exchange Between Mesopotamia, the Levant and Lower Egypt from 5800 to 5200 ... Sudan and the Levant; Katharina Streit (11/10/2020)

Colonialism and Christianity in Mandate Palestine; Laura Robson (September 1, 2011)

Poetic Astronomy in the Ancient Near East The Reflexes of Celestial Science in Ancient Mesopotamian, Ugaritic, and Israelite Narrative; Jeffrey L. Cooley (2013)

Hasidism, Haskalah, Zionism: Chapters in Literary Politics (Jewish Culture and Contexts); Hannan Hever (October 17, 2023)

Mourning in the Ancient Near East and the Hebrew Bible; Xuan Huong Thi Pham (1999)

Medieval Hebrew Poetry in Muslim Egypt; Joachim J.M.S. Yeshaya (2011)

The Land that I Will Show You: Essays on the History and Archaeology of the Ancient Near East in Honor of J. Maxwell Miller; J. Andrew Dearman & M. Patrick Graham (January 9, 2002)

Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition; Thomas L. Thompson (2003)

Prisons in Ancient Mesopotamia, Confinement and Control until the First Fall of Babylon; Dr. J. Nicholas Reid (2022)

Prophets Male and Female: Gender and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, the Eastern Mediterranean, and the Ancient Near East; Jonathan Stökl & Corrine L. Carvalho (2013)

The Calm before the Storm- Selected writings of Itamar Singer on the late Bronze Age in Anatolia and the Levant; Itamar Singer (2012)

"Holiness" and "purity" in Mesopotamia; E. Jan Wilson (1994)

The Material Culture of the Northern Sea Peoples in Israel; Ephraim Stern (2013)

Family and Household Religion in Ancient Israel and the Levant; Rainer Albertz and Rüdiger Schmitt (2012)

Scribal Education in Ancient Israel: The Old Hebrew Epigraphic Evidence; Christopher A. Rollston (11/2006)

Neanderthals in the Levant- Behavioural Organization and the Beginnings of Human Modernity; Donald O. Henry (10/2003)

Suddenly, the Sight of War- Violence and Nationalism in Hebrew Poetry in the 1940s; Hannan Hever (2016)

Gender and Law in the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East; Victor H. Matthews, Victor H. Matthews, Bernard M. Levinson, Tikva Frymer-Kensky (1998)

The concept of fate in ancient Mesopotamia of the 1st millennium: Toward an understanding of 'simtu'; Jack N. Lawson (1992)

The Myth of the Jewish Race; Raphael Patai, Jennifer Patai Wing (01/01/1975)

The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492; Peter Cole (01/22/2007)

Encyclopedia of Jewish Folklore and Traditions; Raphael Patai (2013)

Hebrew Myths; Robert Graves and Raphael Patai (2005)

Vast as the Sea - Hebrew Poetry and the Human Condition; Samuel Hildebrandt (12/05/2023)

Sex & Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature; Gwendolyn Leick (1994)

Far East Asian:

Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations; Charles Higham (2004)

Aboriginal Australia:

Aboriginal Peoples: Fact and Fiction; Pierre Lepage, Maryse Alcindor, Jan Jordon (2009)

Visions from the Past: The Archaeology of Australian Aboriginal Art; M.J. Morwood, Douglas Hobbs, D.R. Hobbs (2002)

Mixed or Other:

Early Civilizations of the Old World: The Formative Histories of Egypt, The Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China; Charles Keith Maisels (May 20, 2001)

20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment; Francois Boucher (1967)

Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam; Chouki El Hamel (2012)

The Birth of Science: Ancient Times to 1699; Ray Spangenburg & Diane Kit Moser (2004)

The Architecture of Castles: A Visual Guide; Reginald Allen Brown (1984)

Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide; Leslie Alan Horvitz and Christopher Catherwood (2006)

Linguistic

Cuneiform; Irving Finkel, Jonathan Taylor (2015)

An Introduction to the Grammar of Sumerian; Gábor Zólyomi (2017)

Learn to Read Ancient Sumerian: An Introduction for Complete Beginners; Joshua Aaron Bowen, Megan Lewis (2020) Learn to Read Ancient Sumerian: An Introduction for Complete Beginners, Volume 2; Joshua Aaron Bowen, Megan Lewis (2023)

The Sur₉-Priest, the Instrument giš Al-gar-sur₉, and the Forms and Uses of a Rare Sign; Niek C. (1997/1998)

Sumerian Grammar (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section One, the Near [And] Mi) (English and Sumerian Edition); Dietz Otto Edzard (2003)

A Late Old Babylonian Proto-Kagal / Nigga Text and the Nature of the Acrographic Lexical Series; Niek VELDHUIS -Groningen (1998)

Learning To Pray In A Dead Language, Education And Invocation in Ancient Sumerian; Joshua Bowen (2020)

Aboriginal Sign Languages of The Americas and Australia: Volume 1; North America Classic Comparative Perspectives; Garrick Mallery (auth.), D. Jean Umiker-Sebeok, Thomas A. Sebeok (eds.) (1978)

The Literature of Ancient Sumer; Jeremy Black, Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, Gabor Zolyomi (2004)

Sumerian Lexicon: A Dictionary Guide to the Ancient Sumerian Language; John Alan Halloran (2006)

A Sumerian Chrestomathy; Konrad Volk (1911)

Online Articles, Dictionaries And Other Resources:

https://nationalclothing.org/middle-east/305-traditional-clothing-of-mesopotamia-what-did-it-look-like.html

https://www.getty.edu/news/meet-the-mesopotamian-demons/

https://factsanddetails.com/world/cat56/sub363/

https://ehistory.osu.edu/articles/marriage-ancient-mesopotamia-and-babylonia

https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section5/tr561.htm

http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/nepsd-frame.html

https://www.britannica.com/place/Africa/Trade

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2185/festivals-in-ancient-mesopotamia/

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/25/well/family/cutting-out-the-bris.html

http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/nannasuen/

https://phys.org/news/2023-08-idea-imprisonment-prisoners-earliest-texts.html

http://www.mathematicsmagazine.com/Articles/TheSumerianMathematicalSystem.php

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ooHEYR30oNCdI4Xxop9qBjKQGnqTPwLHQzT8cvv5oxA/edit Sumerian Grammar Made Easy! (2022 Edition)

Historians, linguists, etc:

https://sumerianlanguage.tumblr.com/ aka http://www.jamesbarrettmorison.com/sumerian.html

https://sumerianshakespeare.com/

https://www.youtube.com/c/DigitalHammurabi aka https://www.digitalhammurabi.com/

https://twitter.com/digi_hammurabi and https://twitter.com/DJHammurabi1

Podcasts and online-exclusive documentaries, video essays, etc

8. The Sumerians - Fall of the First Cities (2020)

13. The Assyrians - Empire of Iron (2021)

The Complete and Concise History of the Sumerians and Early Bronze Age Mesopotamia (7000-2000 BC) (2021)

The Royal Death Pits of Ur (2022)

Gilgamesh and the Flood (2021)

The Birth of Civilisation - Rise of Uruk (6500 BC to 3200 BC) (2021)

The Earliest Creation Myths - Mythillogical (2022)

Enuma Elish | The Babylonian Epic of Creation | Complete Audiobook | With Commentary (2020)

Eridu Genesis | The Sumerian Epic of Creation (2021)

Irving Finkel | The Ark Before Noah: A Great Adventure (2016)

Cracking Ancient Codes: Cuneiform Writing - with Irving Finkel (2019)

Ancient Demons with Irving Finkel I Curator's Corner S3 Ep7 #CuratorsCorner (2018)

How to perform necromancy with Irving Finkel (2017)

Mesopotamian ghostbusting with Irving Finkel I Curator's Corner + #CuratorsCorner (2018)

Video Games

Sonic The Hedgehog Encyclospeedia; Ian Flynn (2021)

Direct Inspiration

The Golden Compass (1995), The Subtle Knife (1997); The Amber Spyglass (2000); Philip Pullman

The Last Unicorn; Peter S. Beagle (1968)

The 13 and ½ Lives Of Captain Bluebear: A Novel; Walter Moers (1999)

Allerleirauh; Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (1812)

The Epic of Beowulf; Anonymous (c. 700–1000 AD)

The Writing In The Stone; Irving Finkel (October 10, 2017)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ashurnasirpal II and the Greatest Party Ever Thrown

By Anthony Huan - https://www.flickr.com/photos/anthonyhuan/44841858665/, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91494202

Ashurnasipal II was the third king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, was born in 910 BCE, and reigned from 883-859 BCE. He was particularly know for his cruelty, as well as for building a new capital for Assyria at what is now known as Nimrud in 15 years. For the labor, he used enslaved captives from his campaigns to expand the boundaries of the Assyrian Empire. To maintain control over his empire, he installed Assyrian governors as opposed to allowing localities to just pay tribute which had been the standard practice before he ruled. He led campaigns along the Euphrates and into Lebanon and Phoenicia. Any revolts were harshly put down, preventing further revolts. In contrast to this violence, the artwork that Ashurnasipal left behind is rich and varied, including many reliefs and bronze bands that held up gates. He also created a zoo within his new capital as well as botanical gardens.

source: https://www.academia.edu/30872972/Merciful_messages_in_the_reliefs_of_Ashurnasirpal_II_the_land_of_Su%E1%B8%ABu

It was at the inauguration of his new palace that Ashurnasipal held a huge 10-day banquet in about 679 BCE. He inscribed on the walls of his palace about this feast. Invitations went out to the entire country, of whom 69,574 accepted. Among these were 16,000 citizens of the new capital and 5,000 dignitaries. To feed the guests required a lot of food, which included:

'1,000 oxen

1,000 domestic cattle and sheep

14,000 imported and fattened sheep

1,000 lambs

500 game birds

500 gazelles

10,000 fish

10,000 eggs

10,000 loaves of bread

10,000 measures of beer

10,000 containers of wine'

in addition to the spices and side dishes to go with these foods.

source: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1849-0502-1

Exactly why Ashurnasipal decided to host such a gathering was not recorded or has not been found. What has been found is something called the Standard Inscription because it was posted many times through the palace, which traces Ashurnasipal's ancestors three generations as well as his military victories and the boundaries of his empire. It then recounts the founding of Kalhu (modern-day Nimrud). The text of the Standard Inscription begins

'Palace of Assurnasirpal, vice-regent of Aššur [national god of Assyria], chosen one of the gods Enlil and Ninurta beloved of the gods Anu and Dagan destructive weapon of the great gods, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Tukulti-Ninurta, great king, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, son of Adad-Nirari great king, strong king, king of the universe, king of Assyria; valiant man who acts with the support of Aššur, his lord, and has no rival among the princes of the four quarters, marvelous shepherd, fearless in battle, unopposable mighty floodtide, king who subdues those insubordinate to him, he who rules all peoples, strong male who treads upon the necks of his foes, trampler of all enemies, he who smashes the forces of the rebellious, king who acts with the support of the great gods, his lords, and has conquered all lands, gained dominion over all the highlands and received their tribute, capturer of hostages, he who is victorious over all countries…'

and then describes his campaigns then the rebuilding of Kalhu. Exactly what the dignitaries thought of the party or of Kahlu hasn't been found, though the use of the title 'king of the universe' was contested by the kings of other nations.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the oldest goddesses in the historical record is Inanna of Mesopotamia, who was referred to, among other honorifics, as “She who makes a woman into a man, she who makes a man into a woman.” The power to alter such fundamental categories was evidence of her divine power. Inanna was served by at least half a dozen different types of transgendered priests, and one of her festivals apparently included a public celebration in which men and women exchanged garments. The memory of a liminal third-gender status has been lost, not only in countries dominated by Christian ideology, but also in many circles dedicated to the modern revival of goddess worship. Images of the divine feminine tend to appear alone, in Dianic rites, surrounded only by other women, or the goddess is represented with a male consort, often one with horns and an erect phallus. But it is equally valid to see her as a fag hag and a tranny chaser, attended by men who have sex with other men and people who are, in modern terms, transgendered or intersexed.

— Speaking Sex to Power: The Politics of Queer Sex by Patrick Califia

#m.#ishtar#aššurism#inanna#trans spirituality#galli#trans history#paganism#trans devotees#purposefully trans#trans is divine

828 notes

·

View notes

Text

And just for fun, the Bronze Age equivalent of “do it for her.”

#my workspace#props if you can recognize all the archeological sites and various reconstructions#still love trading colony era Kaneš#wrote a few stories set in that time period#awkward Aššur trying to trade with the Hattic gods#he is just terrible at socialization

1 note

·

View note

Text

The coronation of the king of Assyria by the gods

The Assyrian king receives the insignia of power from the gods Aššur (Ashur) and Ištar (Ishtar).

Ashur is in front of the Assyrian king and Ishtar is behind him and puts the king's hat on the king's head.

Read More:

What does ashurbanipal name mean (Text Post)

How does Ashurbanipal introduce himself (Text Post)

#archaeology#ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamia#ancient history#akkadian#ancient iraq#ancient assyria#assyrian#ancient empire#ancient assyrian king#history of mesopotamian kings#history of ancient assyrfia#god of ashur#god of ishtar#gods of mesopotamia

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inana & Ištar's Husbands

Sumerian Inana is married to Dumuzid [5 p1] [2 p31-32] in at least the cults of Badtibira, Uruk, and Ur [3 p75-76].

Akkadian Ištar was married to Semitic Tammuz. Based on linguistic texts. His name spelt with logograms DUMU.ZI in Akkadian. This could be pronounced Dumūzu, Duwūzu, Du'ūzu, Dūzu or Tamūzu depending on time and location [7 p21] with Tammuz being the name pronunciation rendered in Biblical Hebrew [8].

Inana-galga-sud (Inana of Profound Council) equated with Ištar of Babylon was married to Amurru [3 p147].

Inana of Kiš [1 pg 187] or Ištar of Kiš was married to Zababa, a war God [4.1].

Ištar Aššuritum was married to Aššur [4.2] the national God of the Assyrian Empire. He collected innumerable roles from syncretism making him rather lacking in distinct characterization [1 p38].

.▪️.

Dumuzid a shepherd God of fertility whose death was frequently mourned in cultus maintained by women. Inana is responsible for Dumuzid's death in "Inana's Descent" and "Dumuzid & Ĝeštinana" which is unusual in Dumuzid literature [6 p48][7 p35]. In many other literature it is not her fault but demons, acting on their own or possibly at the behest of higher powers; or bandits raiding his sheepfold [6 p48][5 p1].

🔹Notes & Sources

Different sources such as the three dictionaries I use can contradict each other at times, hence the usage of synthesizing research information is always necessary.

Inana and Ištar gathered up other Goddesses all over the Ancient Near East and became equated with them; far outlasting the worship of the original Goddesses she was syncretized with. I was going to add them to this list but it's a very big undertaking so I'll stick with those Goddesses named Ištar or Inana for now.

This was a part of a draft post that I am discarding, but I thought this information might be interesting anyways!

Sources

[1] Illustrated Dictionary of Gods Demons and Sumbols of The Ancient Near East by Black and Greene — Link

[2] Ancient Near Eastern Mythology by Leick — Link

[3] A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East by Frayne and Stuckey — Link

[4] - ORACC Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses Project. | 4.1 Zababa— Link | 4.2 Inana/Ishtar— Link,

[5] Harps That Once by Thorkild Jacobsen — Google Books Link

[6] Treasure's of Darkness by Thorkild Jacobsen

[7] Dying & Rising Gods by Ayali Darshan Noga Link

[8] Bible, Book of Ezekiel 8:14

#inana#inanna#ishtar#ištar#gods#goddess#goddesses#divine#deity#syncretism#mesopotamia#mesopotamian#sumerian#akkadian#sumer#polytheism#polytheist#pagan#history#ancient history#landof2rivers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The group of ten men who profited from the sale of Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter in the city of Aššur were entirely ordinary. That group included a baker, a weaver, a cook, a shepherd, an ironsmith, and a goldsmith, some of whom worked for a local temple. The most likely explanation for how they came into the possession of Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter is that these ten men formed a kisru, or “knot,” the standard unit in which Assyrians performed their required services to the king. These ten ordinary men were thus part-time soldiers, called up for the campaign to Elam, and Nanaya-ila’i and her daughter were their payment for their service on that campaign. When they got back to Aššur, the ten-man kisru couldn’t easily divide up two captives, so they sold her and split the profits: about 50 grams of silver per man, which they then took back to their homes, families, and occupations as iron- and goldsmiths, bakers, and cooks. The two Elamite women were enslaved, and the ten Assyrian men benefited directly from their participation in that campaign.

Did the weaver and cook talk about it, we might wonder? Did they tell their wives and children about what they had seen during the vicious sack of the Elamite capital of Susa, the fire and the ransacked royal tombs and desecrated temples that the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal bragged about in his account of these events, the wanton killing and sexual assault, the enslaved who died on the march back to Aššur? Were they proud of what they’d done, did they feel shame, or did they even think about those events? Did they seem like the actions of other people in other lives, unconnected to the workaday existence of an ironmonger and a baker going about their lives in the spiritual home of the Assyrian Empire?

We simply don’t know the answers to those questions, and we never will. The source material that would allow us to formulate an answer doesn’t exist.

Patrick Wyman, Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future Substack, 2024

#the podcast ep talking about these two people was a particularly memorable one#tides of history#patrick wyman#history

2 notes

·

View notes