a blog for me to ramble about the “Pantheon” universe, where Bronze Age deities struggle to make their mark and survive in a multicultural divine world. | a synthesis of Egyptian, Amorite, Hurrian, Mesopotamian, and Anatolian mythology and history | Current Projects: Papyrus Nabayat - The Baal Cycle - The Battle of Kadesh |

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Kherty, god of the netherworld and ferryman of Duat

Very little is known about Kherty, primarily because he’s not the most social deity and would prefer to keep it that way. Kherty likes hiding hanging out deep in the watery depths of the netherworld where he can’t be bothered. As a minor deity, this seems to be his best option for staying out of shenanigans, but alas, it does seem the shenanigans manage to find him—typically in the form of his brother Sokar making a stupid decision or another.

As a ferryman, his duties involve logistics and transport for the chthonic deities’ offerings — after all, those offerings don’t just teleport to the tables of their gods, someone has to go collect them and bring them to the estates of the chthonic deities. Kherty prefers not transporting any beings and would rather work with supplies only (maybe because objects don’t gossip or cause drama), but when a lot of deceased come through Duat, sometimes he doesn’t have much of a choice.

Though a timid deity, he does end up gaining some spine around the First Intermediate Period. Maybe Usire is just a bad influence - who knows - but Kherty seems engaged in eating hearts, cursing others, and being generally troublesome toward the deceased in the netherworld, enough that they beg Ra through prayer to save them from Kherty and Usire. Perhaps some topside propaganda against the netherworld deities? It wouldn’t be the first time, and certainly won’t be the last.

Additional information about Kherty:

Both he and his elder brother Sokar are chthonic deities that were born underground in the realm of Duat. Despite this, both are nonetheless connected to the skies, though the connection for Kherty is more tenuous and related to his lineage than his divinity. While Sokar only wears a hawk headdress, Kherty has both a hawk and a ram to wear. The hawk headdresses are influenced by the ones that their father, Khenty-irty, used to wear.

Kherty also goes by the name of Khenty-irty (the younger), hence the hawk headdress that he doesn’t wear. He still frequents his cult city, Khem, where he’s worshipped both under his own name (Kherty) and his father’s name (Khenty-irty) out of a desire to preserve his family legacy.

Kherty only transported offerings from the surface for Sokar, for obvious reasons (he doesn’t like Anpu or Wepwawet given the contention between their families). When Usire became the Lord of the Dead, Kherty took a shine to him and started transporting his as well. Moving the offerings into Duat for two of the most famous chthonic deities keeps both him and his barque plenty busy.

Kherty is not married and considers himself too flighty to ever consider a long-term relationship. He also gets second hand embarrassment from Sokar’s crush behavior (particularly with Ptah) and would rather not act that way himself. He can practically guess he himself would be a lost cause.

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#lore#ancient kemet#papyrusnabayat#kherty

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ra, god of the afternoon sun

Few deities have attained as a high a position with the mortals as Ra, and his ego matches his worship. Confident, elitist, and with a nasty temper, you can tell that all those violent eye-goddesses are definitely Ra’s daughters. The rage and power of the sun is known to all, and his grip on control of Kemet ever since the 3rd Dynasty can be tyrannical to some, but Ra has been difficult to shake from his position. Well, until Amun came along, anyway.

Ra understands the value of both power and politics. As a result he has a habit of marrying his daughters (of which most of his children are daughters, given he has only two sons) to deities he wants to control or keep subjugated under his thumb. And that worked great up until he married Mut to Montu, to gain some control down in the area of Waset… until Mut decided she’d rather date that hot Nubian god named Amun, and Ra’s problems formally began.

He hates, hates, hates Amun. There is nothing Ra despises more than the fact that Amun gets the honorific position in their Amun-Ra synchronism. Kingship has always belonged to Ra and his carefully decided descendants, and when the Third Intermediate Period came along and the Priests of Amun decided they ought to be running the south instead of the pharaoh in the north, or that set of Nubian pharaohs empowered by Amun, well… suffice to say Ra is on the verge of an all-out war with Amun, a war that no one can afford to engage in with all the changes happening in the world around them. Who’s going to defend Kemet against the Assyrians if Ra and Amun are busy in-fighting?

Some bonus information about him:

In search of power and immortality like the Sumerian gods, who did not have to deal with ba’s and ka’s, Ra was cursed early in his life to reflect his three names - Khepri, Ra, and Atum (though these are technically the nicknames for each phase of his identity and not the names themselves). In simplified form: as the sun changes positions in the sky, he experiences a mortal life and is reborn at sunrise as Khepri, becomes strong and youthful again as Ra at high noon, then ages into an elderly form as Atum in the evening before becoming reborn again.

He was cursed by the snake god Rerek right before the First Intermediate Period, in which Ra started physically changing as he entered each phase. The story is a whole thing on its own that stretches back to Ra’s jealousy over Rerek’s ability to revive his form directly as an ahk-spirit (or divine soul) without having to unite a ba and ka together. Ra could see that Rerek’s divinity was different and was immensely jealous over it. (Bonus lore: Rerek is the snake that stole the herb of immortality from Gilgameš. You pull that kind of shit and you get kicked out of your homeland by Ninazu.)

Ra’s aging isn’t exactly like a mortal’s in its transition. At 6 AM, the sun rises and he is Khepri, who appears about 15 years old. He slowly ages at a rate of 2.5 years/hour until 12 PM, when he looks about 30 and becomes Ra. He ages at a rate of 2.5 years/hour again until he’s 45 at 6 PM, then continues aging at that same rate. At midnight, when he appears about 60, his rejuvenation triggers and he starts aging backwards at a rate of 7.5 years/hour then eventually reaches the age of Khepri at 6 AM and starts aging forward again at the slower rate.

This means that when Ra encounters Apep in the seventh hour of the night (1 AM) his rejuvenation has already triggered and he’s one hour into reversing his aging back into Ra (which takes, in this compressed time period, three hours). So he’s 52.5 years old, roughly, when he fights Apep as Atum. Because he’s not at his strongest (30-45) he struggles with fighting the serpent alone and needs assistance of other gods—though Atum is still very strong, and by no means helpless.

Ra does have three names. Names are powerful and allow a degree of compelling against the being they’re tied to, so deities keep their true names secret. Aset knows Ra’s true name, but she doesn’t know Atum or Khepri’s. This means that from 3 AM - 6 AM and 12 PM - 6 PM, Aset can compel Ra using his true name.

#ra#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#lore#papyrusnabayat#ancient kemet#re#ra sun god#re sun god#sun god#god of the afternoon sun

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aššur, god of the city of Aššur ⛰️

Aššur iconography can be a little elusive. Some depictions alongside Neo-Assyrian kings show what looks like to me like a winged mountain god with a bow and arrow.

I chose osprey details out of pure vibes. Ospreys are native to the area and it makes sense that, if he’s a bird, he’s probably a bird that enjoys high places (large cliff I mean mountain!) and enjoys a good fish out of the river beside his cliff. Osprey markings look nice, too.

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#assur#aššur#assyrian#assyrian mythology#mesopotamia#mesopotamian mythology#mesopotamian gods#assyrian gods#ashur#when you and your city are named the same thing#which assur are we talking about? the city or the god? maybe it’s both

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telipinu, storm god of Hatti 🌩️

Telipinu was well known for his ferocious temper. Frequently mortals had to engage in a mugawar to draw him back after he’d departed in a rage. Frankly, Telipinu just wanted to take a sullen nap; wouldn’t anyone be angry if awoken with a bee sting?

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#telipinu#hittite mythology#hittite#hattusa#hattuša#hattian mythology#luwian mythology#because let’s be honest the disappearing deity myth has luwian influence written all over it#you think i don’t see those wool threads? i see those wool threads#land of hatti#hatti#nešian#neshian#luwian#lore

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Djehuty, god of scribes 📜

One of Djehuty’s most important tasks was protecting mortal scribes. He inspired them to learn and grow in their literacy and was often depicted sitting over them in his baboon form.

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#lore#ancient kemet#djehuty#thoth#tehuti#mythological fiction

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sutekh, god of Naqada ☀️

The ancient city of Naqada (Nubt, Nabayat, choose your vocalization) has always been his home. A place he could go where his most demonized actions would never follow. They know who their protector is and who it always has been.

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#lore#papyrusnabayat#ancient kemet#sutekh#suty#setekh#set#seth#naqada

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baal of Ugarit ⛈️

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#baal#balu#baal of ugarit#ugarit#ugaritic mythology#ugaritic#amorite mythology#amorite-mythology#he looks like he’s trying to advertise a new vacation spot#come visit ugarit! we have newly renovated hotel rooms in my temple for visiting deities!#just don’t mind the snail smell#baal hadad#hadad#haddu

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, are you telling me Sutekh used la chancla as the murder weapon?

#sutekh#bronze gods#pantheon#lore#bronzegods#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#listen i have a healthy fear of la chancla i think this is a completely legit murder weapon

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nebet-hut, goddess of darkness and mourning

If there’s one goddess who feels like she’s drawn the short stick in the bunch, it’s Nebet-hut. While she’s undoubtedly part of a quartet of siblings that play some of the biggest roles in Kemet’s divine sphere, Nebet-hut is often left feeling like an afterthought tacked on to balance Sutekh. If he didn’t exist, would she, when she was the last one born and everyone comes in balanced pairs?

Her relationship with her sister, Aset, has always been complicated. She loves her sister, but can’t help but feel like everyone—from their parents to their worshippers—consider her like an extension of Aset. Aset is more important, more powerful, the queen. What is Nebet-hut but a shadow of her sister? How does a goddess make an identity for herself when she’s always envisioned as a double to Aset? Nebet-hut is forever entangled in trying to figure out what she wants out of her existence, independent of what Aset or their brother Usire needs.

And then there’s Sutekh. Good grief, she did not want to be married to him. Not only is Nebet-hut not attracted to him, but she resents the fact that yet another aspect of her independence and identity has been ripped from her. If she’s not Aset’s Sister, then she’s Sutekh’s Wife. Why can’t she be herself? To make matters worse, Nebet-hut has figured out one thing she wants out of life—she wants to be a mother—and Sutekh is infertile and cannot even give her that. It adds yet another layer of frustration and anger on top of everything else.

Nebet-hut already feels like goddesses play second sistrum to gods. She sees the pain and struggle that Aset goes through, trying to earn respect for her position as queen despite what feels like the world working against her. And Nebet-hut will always support her in that endeavor. But Aset doesn’t seem to comprehend how truly invisible Nebet-hut is to the world when not linked to one of her siblings, and Nebet-hut honestly wishes she would.

Highlights of her life include:

- Nebet-hut has generally tried to play the role she was forced into without complaint, as she was socialized to do so, but when Sutekh couldn’t make her a mother she took matters into her own hands. Nebet-hut, though she feels bad about stepping outside her marriage to try to conceive children, has figured out that no one is going to give her what she wants or needs out of life; only she can do that for herself.

- She has a strong relationship with her mother, Nut, stronger than Aset has, which is one of the few things Nebet-hut has over Aset. And it’s sad that she has to silently compete over something like that to boost her self-esteem, but it is what it is.

- In her efforts to achieve her own independence and shape her life independently of her siblings, she has actually found herself to be quite fond of Sokar. The two have a good affinity with each other. Her relationships with the Duat gods in general is far healthier than her other siblings, and she cares deeply for the deceased mortals that pass through Duat itself. It does seem that if ever there was a time that Kemet considered a Queen of the Underworld like Sumer has, she would be the best option. A Kemetic Ereškigal, anyone? Maybe? Perhaps? It would be nice…

Lines commissioned from Argenemartwork

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#papyrusnabayat#ancient kemet#lore#nebethut#nebet-hut#nephthys#nebethet#nebet-het

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hathor, goddess of love, sexuality, music, and the sun

Hathor is the middle child in Ra’s brood of sun goddess daughters (and the twin to Sekhmet) and one of the famous wrathful Eye Goddesses, but from the way she behaves, you’d think she was the youngest. Hathor tends to flip between behaving very cutesy and speaking in a high-pitched voice and snarling at and threatening other deities, and because of her powerful nature, those threats are pretty potent. She’s independent, goal-oriented, and ruthless in her pursuit of what she wants. Nobody can get in the way of her desires, no matter who they might be.

She has long disliked the fact that her eldest sister, Tefnut, was the one who gained access to the queenship. Hathor has tried her best to weasel her way into power, but the fact that the royal couples tend to result from married twins has made her efforts difficult. It’s not until Heru is born—alone, without being the twin of a goddess—that Hathor sees her opportunity. When Heru comes of age, Hathor swoops in and easily becomes his royal queen, finally achieving the goal that she had her eye on after hundreds of years of yearning. This causes a lot of drama with Aset, but Hathor doesn’t care what Aset wants or what she approves of. She has Heru wrapped around her finger, and now the Kemet pantheon is in her hands.

But what to do with it? Well, she has some ideas, and they involve capitalizing on her popularity among foreigners. Hathor has long had contacts outside of Kemet stretching into Sinai. Her close relationship with Baalat Gebal in Gubla (Byblos) makes her a powerful trade negotiator and has given Kemet a strong foothold in Retjenu. And as the goddess that oversees the turquoise mines in the Sinai peninsula, she has access to rare and valuable trade materials, allowing her influence to stretch even further north and east. Hathor is a force to be reckoned with, one that Aset grows ever more cautious of as her son slips further and further away into the realm of Hathor’s influence.

Highlights in her life include:

- Getting very, very close to seducing Hor the Older, which was why she felt her right to queenship was snatched out of her hands. When her father and sisters planned to go to war with Hor the Older, Hathor tried a more… alternative way of solving the problem. But when she found out Hor had aspirations for marrying Neith (who had zero interest in that arrangement whatsoever), Hathor lost her temper and switched tactics back to violence.

- She has one son with Heru, Ihy, the god of music and joy. Hathor has struggled to get pregnant again and Heru seems uncomfortable about passing the kingship to a god without some sort of war or sun divine aspect, so Ihy seems out of the running as the next king. (As for the “Sons of Horus,” they are his sons in name only and not related to him or Hathor, but that’s a story for another day.)

- Starting quite the rivalry with her family members. She and Aset do not get along in the slightest, and honestly it’s understandable why. She and Tefnut don’t have a very good relationship either due to her jealousy over Tefnut’s firstborn daughter position. She and Sekhmet developed bad blood when Hathor hit on Sekhmet’s husband Ptah at a family gathering. Her youngest sister Bastet mostly ignores her, and Hathor returns the same.

Commissioned lines from Argenemartwork

#papyrusnabayat#pantheon#bronzegods#bronze gods#mythological fiction#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#ancient kemet#lore#hathor#granted the mentions of Heru don’t happen during Papyrus Nabayat as it takes place prior to Heru’s birth for the most part#hathor and aset are definitely the equivalent of an unmovable object meeting an unstoppable force#both of them are super powerful and can’t seem to get rid of each other#egyptian-mythology

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Siege of Aleppo comic script snippet

A brief view of Ninurta’s perspective regarding his adoption into the Assyrian pantheon (becomes quite relevant at the end of the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age - the Assyrian kings really like him!) and his experience in Kassite Babylon.

Adad is more ride or die for Assur, but they’ve also known each other since the Assyrian trading colony period.

#siege of aleppo#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#ninurta#adad#assur#lore#textcorpus#Ninurta really hates the Kassite gods and that’s the only reason he went north to Assyria anyway#Marduk hates them too but that’s to be expected lol#assyrian-mythology

0 notes

Text

Last night’s stinky writing session: Ninurta can’t resist taking a shot at the Hurrian gods.

Siege of Aleppo comic.

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#ninurta#tessub#hurrian#The pantheon universe is a series of comic strips so this is how I write them in preparation for the comic#lore#This is actually set after the Battle of Kadesh story#it’s the Seige of Aleppo that happens when Assyria makes eyes at aleppo while Hatti and Mitanni are exhausted from fighting Egypt#text corpus

0 notes

Text

The internal crisis of deities who have fallen out of power

Power shifts frequently in history. New empires arise, new leaders make better use of their resources and people, and old centers of power can fall or become subjugated. What happens to deities who once enjoyed power and find themselves becoming more and more irrelevant as time goes on?

Enki is the case study here. The god of the subterranean waters was one of the big three most powerful and well-known deities in the Sumerian pantheon, alongside his brother Enlil and his father Anu. Even when the Akkadian Empire defeated the Sumerian city-states, Enki’s position hardly changed in the paradigm of divine power, though he found it shifted somewhat to accompany the authority of new deities like Ilaba and Dagan. Still, he was respected. The Akkadian conquerors renamed him to Ea and continued venerating him.

But what happened after that?

The world continued changing. New centers of power arose in Syria and Anatolia, and with it, new gods were born. Enki, once considered one of the most powerful deities, slowly watched himself be eclipsed by younger ones. Fame was a double-edged sword for him — he was famous enough to command some respect from foreign deities, but this clashed with the fact that he simply wasn’t the terrifying force of nature he used to be and many of them were more than willing to defy him. New wisdom and knowledge gods were born, new crafting gods were born, new gods of subterranean waters were born. Where did that leave him?

In crisis, apparently. Enki started taking on new identities to run away from the fact that the world was leaving him behind. He took on the name of Hayya and became a Hurrian crafting god, seeking new purpose in life given that his city, Eridu, was abandoned because of climate change.

Having power and then losing it tends to be detrimental to deities. Marduk has suffered from deep depression since Babylon fell to Hatti and remains in the hands of the Kassites. Enlil has gone deep underground, seeking some sort of peace away from the chaos above. Enki continues to have an identity crisis, seeking out new names and, in a way, a new life for himself.

And situations where a city has been lost, like with the gods of Ebla? They scattered after its final fall, some of them carrying the scars of trauma on their psyches as they sought out new pantheons to join. Some of them were successful.

Unfortunately, many aren’t.

#lore#bronze gods#mythological fiction#pantheon#bronzegods#enki#mesopotamian mythology#mesopotamian gods#mesopotamia

0 notes

Text

Marduk and Assur - Babylon and Assyria

Marduk and Assur are two Mesopotamian deities tied closely to their respective cities - Marduk with the city of Babylon and Assur with the city of Assur. In Pantheon, their destinies have been linked from early on, with their origins beginning in the Sumerian period…

The two deities are brothers, born at roughly the same time and sired by Enki, the famous god of the subterranean waters. Marduk, then named Asalluhe, was his child by Damkina, his wife, and therefore was more legitimate than Assur. Assur’s mother was an Amorite goddess that Enki was fooling around with, and given that Amorites were poorly looked upon by the Sumerians in this time period, Enki tried his damned hardest to conceal knowledge of said fooling around. Unfortunately, it’s more difficult to hide a godling baby that looks like you and has your family’s distinctive winged deity appearance, so he was left with a child that was for all intents and purposes unwanted.

Asalluhe and Assur grew up with disparate lives. Enki, not exactly known for his parenting skills, shoved his young sons off on other deities to raise them. In Asalluhe’s case, Utu the sun god was given the responsibility to raise one child. Dumuzi was given the responsibility to raise Assur.

Unfortunately, with Dumuzi’s proximity to Inanna, that didn’t bode well for Assur. While Asalluhe adored his “Uncle Utu” and changed his name to Marduk (calf of the sun) in appreciation, Assur moved away from the south as quickly as possible and returned to the outcrop of rock he’d been born at. The city of Assur formed around him, and as far as he was concerned, he was more than happy to stay far away from the south and all the bad memories it held.

As the climate changed, the southern Sumerian city-states dried up and Babylon came into power. With it, Marduk raised to power, finding himself beloved by the Amorite conquerors who took over Babylon. Marduk enjoyed kingship and power… until the gods of Hatti sacked Babylon and left him shattered. Damn Hittites didn’t even bother sticking around; the Kassite gods soon moved in and subjugated Marduk under their feet.

Assur fared hardly better. He built an impressive trade network, but his city fell into the control of the Akkadian Empire, the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia (Shamshi-Adad’s empire), and the Mitanni Empire. Only at the tail end of the Bronze Age did Assur start to regain his independence, enough to start challenging Hatti, Mitanni, and (Kassite) Babylon.

The Iron Age, though, is when the two really start to clash…

Illustrations commissioned from Eaglidots

#bronze gods#mythological fiction#pantheon#bronzegods#assur#marduk#mesopotamian mythology#mesopotamian-mythology#assyrian#babylon#mesopotamia#mesopotamian gods#lore#iconography

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

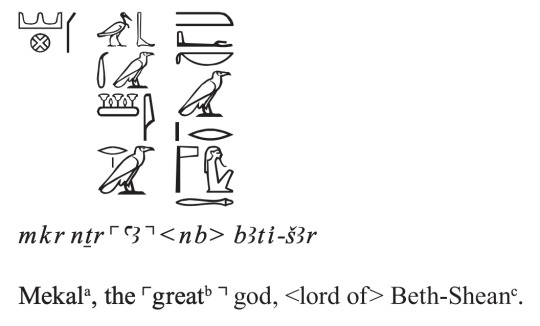

Mekal (or Mekar), the lord of Beth-Shean

I strongly hold that the Baal Cycle is not "Canaanite mythology." The Ugarites themselves identified Canaanites as "foreign people," and Mot, in particular, is strongly suspected to be a literary invention of Ilumilku, the scribe who wrote the Baal Cycle. To subsume the myths under the vague title of 'Canaanite mythology' is a disservice to Ugarit and its creativity, in my opinion.

So that naturally brought a question to mind: are there any Bronze Age deities who are distinctly Canaanite?

Enter Mekal/Mekar. A Fresh Look at the Mekal Stele (Levy 2018) introduces us to a deity who was attested in northern Palestine during the Bronze Age.

(Levy 2018: 361)

That "r" at the end of his name can be either an "r" or a Semitic "l", hence the Mekal/Mekar options for his name. And he's attested as the lord of Beth-Shean (or Bit-Shani, if you fancy the syllabic Akkadian transcription). How cool is that?

Some thoughts about this deity: his iconography is closely aligned with Baal's known iconography from the time period (which should make one wonder if there isn't some possible synchronization afoot, as if Seth-Baal wasn't strong enough evidence, lol), with one caveat: he has Resheph's headband. So some differences!

What I draw from that is Mekal/Mekar is a Baal-like deity but with some differences. In the Pantheon universe, thus, Mekal is primarily a vegetation god with some rain-bringing abilities, not a storm god proper. He doesn't have the weather manipulation capability that Baal does, but he's good at making flowers and helping agriculture grow!

Given the strong Egyptian influence here, Mekal strikes me as the type who really likes lotuses, too. Maybe he really looks forward to the few visits that Nefertem makes in the foreign northern lands? Well, assuming Sekhmet's willing to let him out...

Anyway, Beth-Shean is a major Egyptian administrative center in the Late Bronze Age, so Sutekh likely stops in Beth-Shean often before continuing onward to Gubla (Byblos), another Egyptian holding. Mekal, with his minimal attestation, seems like a very young god (and it's suspicious that he's not attested afterward). Perhaps he was educated in Kemet as a godling and then brought back to Beth-Shean to rule it, as the Egyptians were known for doing with foreign princes. Couldn't get him to get rid of the beard, though. Some cultural influences refuse to die.

Artwork commissioned from Eaglidots

#canaanite mythology#canaanite deity#canaanite god#mekal#mekar#beth-shean#mekal stele#pantheon#bronzegods#bronze gods#don't we love obscure deities#I sure love them because I want to populate the story's world with more than just the most well known deities#lore#amorite-mythology#perhaps… Amorite is the precursor to Hebrew#iconography

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aset, goddess of magic and wisdom

One thing stuck out to me throughout my research: while it’s clear why the ancients envisioned a patriarchal world for their deities (it’s what they were used to socially), how does that work when you really think about it? How do you end up with a society that oppresses powerful magical women? Their society clearly isn’t egalitarian.

Human women are oppressed due to male physical domination over women and attempted control of their reproductive capabilities. But what about goddesses? If a goddess has strong magical powers or possesses superhuman strength equivalent to a male deity, how could goddesses be oppressed the way that human women are?

Social conditioning seems the most likely answer - both by older deities and by the human societies they guard. Kemet has a lot of extremely powerful goddesses, notable among them being Aset, and social conditioning isn’t going to work on all of them. I feel Aset is one of those (like Neith, Hathor, and Sekhmet) who would challenge the social paradigm their pantheons accept as a status quo.

I think mythological settings really need to take into account systems of oppression and how they would play out in a society as different as one composed of deities. It results in a lot of interesting food for thought.

Commissioned lines by ArgenemArtwork

#aset#egyptian mythology#bronze gods#kemet pantheon#mythological fiction#pantheon#bronzegods#papyrusnabayat#ancient kemet#isis#isis goddess#goddess isis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aset, goddess of magic and wisdom

A sharp intelligence has always come easy to Queen Aset. She was the first among her siblings to learn to shapeshift, the first to achieve competency in magic, and the first to challenge and rival Djehuty with her cunning. But it seems that despite the effort she puts in, it’s never been enough to earn the respect of the elder gods. All eyes were on on Usire, her husband, to lead Kemet and enable it to prosper. To them, she’s just an afterthought, the Deified Wife, and she’s determined to change that - for herself, for her sister, and for every young goddess who will be born in Kemet in the future.

But it’s not easy to shift this paradigm in a world steeped in centuries of misogyny. With her husband gone, it’s painfully obvious that Kemet refuses to envision a pantheon with a goddess at its head, even though she was the one drafting and executing all the agreements with surrounding foreign pantheons. The truth is, they don’t want to be ruled by a single queen. And that’s just too damn bad, because she’s not letting them crush her aspirations underfoot. A better future for Kemet will arise, whether they like it or not.

Tricking Ra into giving up his secret name was the first step. With Ra being the biggest source of the dismissive sexism leveled at her, controlling him was a key mission. But now she has a new challenge - her own brother, Sutekh, threatens her sovereignty after he kills her husband and makes a claim to the throne. Sutekh rivals her in magical prowess and exceeds her in raw strength, making him a formidable enemy. There are only two ways this can go if she wants to stay queen: either she marries Sutekh, as Ra has demanded, or she kills him.

The second is a far more attractive option.

Highlights in her life include:

Famously tricking Ra into revealing his secret name. The power of his secret name allows her to compel him when he’s in his powerful afternoon sun form, which prevents him from outright smiting her for defying him. She has been unsuccessful at doing the same to Atum, the evening sun, which complicates her plans - she can out-magic him, but his political power still makes him dangerous. Fortunately, Khepri, the morning sun, has proven himself to be little trouble.

Negotiating and executing a treaty with the underworld gods, who are headed by Khenti-Amentiu and his myriad of jackal god sons. Inviting Anpu to participate in Iunu’s royal court has given Kemet unprecedented peace with the Duat gods, a much needed change after a prolonged war between her father and previous king Geb and Khenti-Amentiu.

Securing the loyalty of Baalat of Gubla, in the Retjenu city of Gubla (modern Byblos), which has given Kemet access to communications and trade with pantheons as far east as Mari, Ebla, and the land between the two rivers itself (the Sumerian city-states, notably its biggest city, Ur).

Her relationship with her brother-husband Usire was all right, but she did resent that she put in all the political work and he got all the credit. Usire wasn’t a bad fellow, but he was far more interested in the natural landscape (the Nile inundations and vegetation, unsurprisingly, given his affinities) than playing politics. The two balanced each other out well, and Usire respected her, but he couldn’t quite grasp the frustration she dealt with at being a woman in a man’s world.

She does have some hope that Kemet can change, though. Of all the elder gods, one in particular supports her sovereignty strongly — Min, the god of Koptos. She never expected he of all deities would align with her political goals, but Min has always been full of surprises, and continues to be a valuable confidant and friend.

Commissioned Lineart by Argenemartwork

#aset#isis goddess#isis#bronze gods#egyptian mythology#kemet pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#pantheon#papyrusnabayat#ancient kemet#egyptian gods#The delicious irony is that she desperately wants change for Kemet and Sutekh is the god of change and the one most likely to support it#but they have a lot of reconciling to do before they can ever get to that point

5 notes

·

View notes