#telipinu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Telipinu, storm god of Hatti 🌩️

Telipinu was well known for his ferocious temper. Frequently mortals had to engage in a mugawar to draw him back after he’d departed in a rage. Frankly, Telipinu just wanted to take a sullen nap; wouldn’t anyone be angry if awoken with a bee sting?

Commissioned from Kiwibon

#bronze gods#pantheon#bronzegods#mythological fiction#telipinu#hittite mythology#hittite#hattusa#hattuša#hattian mythology#luwian mythology#because let’s be honest the disappearing deity myth has luwian influence written all over it#you think i don’t see those wool threads? i see those wool threads#land of hatti#hatti#nešian#neshian#luwian#lore

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Telipinu was Huzziya's brother-in-law and received just in time news that he was going to kill himself and his wife. He did not kill Huzziya, but exiled him and his five brothers from the capital. By doing so, he may have hoped to put an end to the chain of murder that has gripped the dynasty for four generations: 'They have done me wrong, but I will not do them any harm' (van den Hout 1997).

Telipinu, Huzziya'nın kayınbiraderiydi ve kendisini ve karısını öldüreceği haberini tam zamanında aldı. Huzziya'yı öldürmedi ama onu ve beş kardeşini başkentten sürgün etti. Bunu yaparak, dört nesildir hanedanı pençesine alan cinayet zincirine son vermeyi ummuş olabilir: 'Bana yanlış yaptılar ama ben onlara zarar vermeyeceğim' (van den Hout 1997).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

List of Gods, most of which are no longer worshipped. via /r/atheism

List of Gods, most of which are no longer worshipped.

Middle-East

A, Adad, Adapa, Adrammelech, Aeon, Agasaya, Aglibol, Ahriman, Ahura Mazda, Ahurani, Ai-ada, Al-Lat, Aja, Aka, Alalu, Al-Lat, Amm, Al-Uzza (El-'Ozza or Han-Uzzai), An, Anahita, Anath (Anat), Anatu, Anbay, Anshar, Anu, Anunitu, An-Zu, Apsu, Aqhat, Ararat, Arinna, Asherali, Ashnan, Ashtoreth, Ashur, Astarte, Atar, Athirat, Athtart, Attis, Aya, Baal (Bel), Baalat (Ba'Alat), Baau, Basamum, Beelsamin, Belit-Seri, Beruth, Borak, Broxa, Caelestis, Cassios, Lebanon, Antilebanon, and Brathy, Chaos, Chemosh, Cotys, Cybele, Daena, Daevas, Dagon, Damkina, Dazimus, Derketo, Dhat-Badan, Dilmun, Dumuzi (Du'uzu), Duttur, Ea, El, Endukugga, Enki, Enlil, Ennugi, Eriskegal, Ereshkigal (Allatu), Eshara, Eshmun, Firanak, Fravashi, Gatamdug, Genea, Genos, Gestinanna, Gula, Hadad, Hannahanna, Hatti, Hea, Hiribi, The Houri, Humban, Innana, Ishkur, Ishtar, Ithm, Jamshid or Jamshyd, Jehovah, Jesus, Kabta, Kadi, Kamrusepas, Ki (Kiki), Kingu, Kolpia, Kothar-u-Khasis, Lahar, Marduk, Mari, Meni, Merodach, Misor, Moloch, Mot, Mushdama, Mylitta, Naamah, Nabu (Nebo), Nairyosangha, Nammu, Namtaru, Nanna, Nebo, Nergal, Nidaba, Ninhursag or Nintu, Ninlil, Ninsar, Nintur, Ninurta, Pa, Qadshu, Rapithwin, Resheph (Mikal or Mekal), Rimmon, Sadarnuna, Shahar, Shalim, Shamish, Shapshu, Sheger, Sin, Siris (Sirah), Taautos, Tammuz, Tanit, Taru, Tasimmet, Telipinu, Tiamat, Tishtrya, Tsehub, Utnapishtim, Utu, Wurusemu, Yam, Yarih (Yarikh), Yima, Zaba, Zababa, Zam, Zanahary (Zanaharibe), Zarpandit, Zarathustra, Zatavu, Zazavavindrano, Ziusudra, Zu (Imdugud), Zurvan

China:

Ba, Caishen, Chang Fei, Chang Hsien, Chang Pan, Ch'ang Tsai, Chao san-Niang, Chao T'eng-k'ang, Chen Kao, Ch'eng Huang, Cheng San-Kung, Cheng Yuan-ho, Chi Po, Chien-Ti, Chih Jih, Chih Nii, Chih Nu, Ch'ih Sung-tzu, Ching Ling Tzu, Ch'ing Lung, Chin-hua Niang-niang, Chio Yuan-Tzu, Chou Wang, Chu Niao, Chu Ying, Chuang-Mu, Chu-jung, Chun T'i, Ch'ung Ling-yu, Chung Liu, Chung-kuei, Chung-li Ch'üan, Di Jun, Fan K'uei, Fei Lien, Feng Pho-Pho, Fengbo, Fu Hsing, Fu-Hsi, Fu-Pao, Gaomei, Guan Di, Hao Ch'iu, Heng-o, Ho Po (Ping-I), Hou Chi, Hou T'u, Hsi Ling-su, Hsi Shih, Hsi Wang Mu, Hsiao Wu, Hsieh T'ien-chun, Hsien Nung, Hsi-shen, Hsu Ch'ang, Hsuan Wen-hua, Huang Ti, Huang T'ing, Huo Pu, Hu-Shen, Jen An, Jizo Bosatsu, Keng Yen-cheng, King Wan, Ko Hsien-Weng, Kuan Ti, Kuan Ti, Kuei-ku Tzu, Kuo Tzu-i, Lai Cho, Lao Lang, Lei Kung, Lei Tsu, Li Lao-chun, Li Tien, Liu Meng, Liu Pei, Lo Shen, Lo Yu, Lo-Tsu Ta-Hsien, Lu Hsing, Lung Yen, Lu-pan, Ma-Ku, Mang Chin-i, Mang Shen, Mao Meng, Men Shen, Miao Hu, Mi-lo Fo, Ming Shang, Nan-chi Hsien-weng, Niu Wang, Nu Wa, Nu-kua, Pa, Pa Cha, Pai Chung, Pai Liu-Fang, Pai Yu, P'an Niang, P'an-Chin-Lien, Pao Yuan-ch'uan, Phan Ku, P'i Chia-Ma, Pien Ho, San Kuan, Sao-ch'ing Niang, Sarudahiko, Shang Chien, Shang Ti, She chi, Shen Hsui-Chih, Shen Nung, Sheng Mu, Shih Liang, Shiu Fang, Shou-lao, Shun I Fu-jen, Sien-Tsang, Ssu-ma Hsiang-ju, Sun Pin, Sun Ssu-miao, Sung-Chiang, Tan Chu, T'ang Ming Huang, Tao Kung, T'ien Fei, Tien Hou, Tien Mu, Ti-tsang, Tsai Shen, Ts'an Nu, Ts'ang Chien, Tsao Chun, Tsao-Wang, T'shai-Shen, Tung Chun, T'ung Chung-chung, T'ung Lai-yu, Tung Lu, T'ung Ming, Tzu-ku Shen, Wa, Wang Ta-hsien, Wang-Mu-Niang-Niang, Weiwobo, Wen-ch'ang, Wu-tai Yuan-shuai, Xi Hou, Xi Wangmu, Xiu Wenyin, Yanwang, Yaoji, Yen-lo, Yen-Lo-Wang, Yi, Yu, Yu Ch'iang, Yu Huang, Yun-T'ung, Yu-Tzu, Zaoshen, Zhang Xi, , Zhinü, , Zhongguei, , Zigu Shen, , Zisun, Ch'ang-O

Slavic:

Aba-khatun, Aigiarm, Ajysyt, Alkonost, Almoshi, Altan-Telgey, Ama, Anapel, As-ava, Ausaitis, Austeja, Ayt'ar, Baba Yaga (Jezi Baba), Belobog (Belun), Boldogasszony, Breksta, Bugady Musun, Chernobog (Crnobog, Czarnobog, Czerneboch, Cernobog), Cinei-new, Colleda (Koliada), Cuvto-ava, Dali, Darzu-mate, Dazhbog, Debena, Devana, Diiwica (Dilwica), Doda (Dodola), Dolya, Dragoni, Dugnai, Dunne Enin, Edji, Elena, Erce, Etugen, Falvara, The Fates, The Fatit, Gabija, Ganiklis, Giltine, Hotogov Mailgan, Hov-ava, Iarila, Isten, Ja-neb'a, Jedza, Joda-mate, Kaldas, Kaltes, Keretkun, Khadau, Khursun (Khors), Kostrubonko, Kovas, Krumine, Kupala, Kupalo, Laima, Leshy, Marina, Marzana, Matergabiae, Mat Syra Zemlya, Medeine, Menu (Menulis), Mir-Susne-Khum, Myesyats, Nastasija, (Russia) Goddess of sleep., Nelaima, Norov, Numi-Tarem, Nyia, Ora, Ot, Patollo, Patrimpas, Pereplut, Perkuno, Perun, Pikuolis, Pilnytis, Piluitus, Potrimpo, Puskaitis, Rod, Rugevit, Rultennin, Rusalki, Sakhadai-Noin, Saule, Semargl, Stribog, Sudjaje, Svantovit (Svantevit, Svitovyd), Svarazic (Svarozic, Svarogich), Tengri, Tñairgin, Triglav, Ulgen (Ulgan, Ülgön), Veles (Volos), Vesna, Xatel-Ekwa, Xoli-Kaltes, Yamm, Yarilo, Yarovit, Ynakhsyt, Zaria, Zeme mate, Zemyna, Ziva (Siva), Zizilia, Zonget, Zorya, Zvoruna, Zvezda Dennitsa, Zywie

Hindu

Aditi, Adityas, Ambika, Ananta (Shesha), Annapurna (Annapatni), Aruna, Ashvins, Balarama, Bhairavi, Brahma, Buddha, Dakini, Devi, Dharma, Dhisana, Durga, Dyaus, Ganesa (Ganesha), Ganga (Ganges), Garuda, Gauri, Gopis, Hanuman, Hari-Hara, Hulka Devi, Jagganath, Jyeshtha, Kama, Karttikeya, Krishna, Krtya, Kubera, Kubjika, Lakshmi or Laksmi, Manasha, Manu, Maya, Meru, Nagas, Nandi, Naraka, Nataraja, Nirriti, Parjanya, Parvati, Paurnamasi, Prithivi, Purusha, Radha, Rati, Ratri, Rudra, Sanjna, Sati, Shashti, Shatala, Sitala (Satala), Skanda, Sunrta, Surya, Svasti-devi, Tvashtar, Uma, Urjani, Vach, Varuna, Vayu, Vishnu (Avatars of Vishnu: Matsya; Kurma; Varaha; Narasinha; Vamana; Parasurama; Rama; Krishna; Buddha; Kalki), Vishvakarman, Yama, Sraddha

Japan: Aji-Suki-Taka-Hi-Kone, Ama no Uzume, Ama-terasu, Amatsu Mikaboshi, Benten (Benzai-Ten), Bishamon, Chimata-No-Kami, Chup-Kamui, Daikoku, Ebisu, Emma-O, Fudo, Fuji, Fukurokuju, Gekka-O, Hachiman, Hettsui-No-Kami, Ho-Masubi, Hotei, Inari, Izanagi and Izanami, Jizo Bosatsu, Jurojin, Kagutsuchi, Kamado-No-Kami, Kami, Kawa-No-Kami, Kaya-Nu-Hima, Kishijoten, Kishi-Mojin, Kunitokotatchi, Marici, Monju-Bosatsu, Nai-No-Kami, No-Il Ja-Dae, O-Kuni-Nushi, Omoigane, Raiden, Shine-Tsu-Hiko, Shoten, Susa-no-wo, Tajika-no-mikoto, Tsuki-yomi, Uka no Mitanna, Uke-mochi, Uso-dori, Uzume, Wakahirume, Yainato-Hnneno-Mikoi, Yama-No-Kami, Yama-no-Karni, Yaya-Zakurai, Yuki-Onne

India

Agni, Ammavaru, Asuras, Banka-Mundi, Brihaspati, Budhi Pallien, Candi, Challalamma, Chinnintamma, Devas, Dyaush, Gauri-Sankar, Grhadevi, Gujeswari, Indra, Kali, Lohasur Devi, Mayavel, Mitra, Prajapati, Puchan, Purandhi, Rakshas, Rudrani, Rumina, Samundra, Sarasvati, Savitar, Siva (Shiva), Soma, Sura, Surabhi, Tulsi, Ushas, Vata, Visvamitra, Vivasvat, Vritra, Waghai Devi, Yaparamma, Yayu, Zumiang Nui, Diti

Other Asian: Dewi Shri, Po Yan Dari, Shuzanghu, Antaboga, Yakushi Nyorai, Mulhalmoni, Tankun, Yondung Halmoni, Aryong Jong, Quan Yin , Tengri, Uminai-gami, Kamado-No-Kami, Kunitokotatchi, Giri Devi, Dewi Nawang Sasih, Brag-srin-mo, Samanta-Bhadra, Sangs-rgyas-mkhá, Sengdroma, Sgeg-mo-ma, Tho-og, Ui Tango, Yum-chen-mo, Zas-ster-ma-dmar-mo, Chandra, Dyaus, Ratri, Rodasi, Vayu, Au-Co

African Gods, Demigods and First Men:

Abassi , Abuk , Adu Ogyinae , Agé , Agwe , Aida Wedo , Ajalamo, Aje, Ajok, Akonadi, Akongo, Akuj, Amma, Anansi, Asase Yaa, Ashiakle, Atai , Ayaba, Aziri, Baatsi, Bayanni, Bele Alua, Bomo rambi, Bosumabla, Buk, Buku, Bumba, Bunzi, Buruku, Cagn, Candit, Cghene, Coti, Damballah-Wedo, Dan, Deng, Domfe, Dongo, Edinkira, Efé, Egungun-oya, Eka Abassi, Elephant Girl Mbombe, Emayian, Enekpe, En-Kai, Eseasar, Eshu, Esu, Fa, Faran, Faro, Fatouma, Fidi Mukullu, Fon, Gleti, Gonzuole, Gû, Gua, Gulu, Gunab, Hammadi, Hêbiesso, Iku, Ilankaka, Imana, Iruwa, Isaywa, Juok, Kazooba, Khakaba, Khonvum, Kibuka, Kintu, Lebé, Leza, Libanza, Lituolone, Loko, Marwe, Massim Biambe, Mawu-Lisa (Leza), Mboze, Mebeli, Minepa, Moombi, Mukameiguru, Mukasa, Muluku, Mulungu, Mwambu, Nai, Nambi, Nana Buluku, Nanan-Bouclou, Nenaunir, Ng Ai, Nyaliep, Nyambé, Nyankopon, Nyasaye, Nzame, Oboto, Obumo, Odudua-Orishala, Ogun, Olokun, Olorun, Orisha Nla, Orunmila, Osanyin, Oshe, Osun, Oya, Phebele, Pokot-Suk, Ralubumbha, Rugaba, Ruhanga, Ryangombe, Sagbata, Shagpona, Shango, Sopona, Tano, Thixo, Tilo, Tokoloshi, Tsui, Tsui'goab, Umvelinqangi, Unkulunkulu, Utixo, Wak, Wamara, Wantu Su, Wele, Were, Woto, Xevioso, Yangombi, Yemonja, Ymoa, Ymoja, Yoruba, Zambi, Zanahary , Zinkibaru

Australian Gods, Goddesses and Places in the Dreamtime:

Alinga, Anjea, Apunga, Arahuta, Ariki, Arohirohi, Bamapana, Banaitja, Bara, Barraiya, Biame, Bila, Boaliri, Bobbi-bobbi, Bunbulama, Bunjil, Cunnembeille, Daramulum, Dilga, Djanggawul Sisters, Eingana, Erathipa, Gidja , Gnowee, Haumia, Hine Titama, Ingridi, Julana, Julunggul, Junkgowa, Karora, Kunapipi-Kalwadi-Kadjara, Lia, Madalait, Makara, Nabudi, Palpinkalare, Papa, Rangi, Rongo, Tane, Tangaroa, Tawhiri-ma-tea, Tomituka, Tu, Ungamilia, Walo, Waramurungundi, Wati Kutjarra, Wawalag Sisters, Wuluwaid, Wuragag, Wuriupranili, Wurrunna, Yhi

Buddhism, Gods and Relatives of God:

Aizen-Myoo, Ajima,Dai-itoku-Myoo, Fudo-Myoo, Gozanze-Myoo, Gundari-Myoo, Hariti, Kongo-Myoo, Kujaku-Myoo, Ni-O

Carribean: Gods, Monsters and Vodun Spirits

Agaman Nibo , Agwe, Agweta, Ah Uaynih, Aida Wedo , Atabei , Ayida , Ayizan, Azacca, Baron Samedi, Ulrich, Ellegua, Ogun, Ochosi, Chango, Itaba, Amelia, Christalline, Clairmé, Clairmeziné, Coatrischie, Damballah , Emanjah, Erzuli, Erzulie, Ezili, Ghede, Guabancex, Guabonito, Guamaonocon, Imanje, Karous, Laloue-diji, Legba, Loa, Loco, Maitresse Amelia , Mapiangueh, Marie-aimée, Marinette, Mombu, Marassa, Nana Buruku, Oba, Obtala, Ochu, Ochumare, Oddudua, Ogoun, Olokum, Olosa, Oshun, Oya, Philomena, Sirêne, The Diablesse, Itaba, Tsilah, Ursule, Vierge, Yemaya , Zaka

Celtic: Gods, Goddesses, Divine Kings and Pagan Saints

Abarta, Abna, Abnoba, Aine, Airetech,Akonadi, Amaethon, Ameathon, An Cailleach, Andraste, Antenociticus, Aranrhod, Arawn, Arianrod, Artio, Badb,Balor, Banbha, Becuma, Belatucadros, Belatu-Cadros, Belenus, Beli,Belimawr, Belinus, Bendigeidfran, Bile, Blathnat, Blodeuwedd, Boann, Bodus,Bormanus, Borvo, Bran, Branwen, Bres, Brigid, Brigit, Caridwen, Carpantus,Cathbadh, Cecht, Cernach, Cernunnos, Cliodna, Cocidius, Conchobar, Condatis, Cormac,Coronus,Cosunea, Coventina, Crarus,Creidhne, Creirwy, Cu Chulainn, Cu roi, Cuda, Cuill,Cyhiraeth,Dagda, Damona, Dana, Danu, D'Aulnoy,Dea Artio, Deirdre , Dewi, Dian, Diancecht, Dis Pater, Donn, Dwyn, Dylan, Dywel,Efnisien, Elatha, Epona, Eriu, Esos, Esus, Eurymedon,Fedelma, Fergus, Finn, Fodla, Goewyn, Gog, Goibhniu, Govannon , Grainne, Greine,Gwydion, Gwynn ap Nudd, Herne, Hu'Gadarn, Keltoi,Keridwen, Kernunnos,Ler, Lir, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, Lludd, Llyr, Llywy, Luchta, Lug, Lugh,Lugus, Mabinogion,Mabon, Mac Da Tho, Macha, Magog, Manannan, Manawydan, Maponos, Math, Math Ap Mathonwy, Medb, Moccos,Modron, Mogons, Morrig, Morrigan, Nabon,Nantosuelta, Naoise, Nechtan, Nedoledius,Nehalennia, Nemhain, Net,Nisien, Nodens, Noisi, Nuada, Nwywre,Oengus, Ogma, Ogmios, Oisin, Pach,Partholon, Penard Dun, Pryderi, Pwyll, Rhiannon, Rosmerta, Samhain, Segidaiacus, Sirona, Sucellus, Sulis, Taliesin, Taranis, Teutates, The Horned One,The Hunt, Treveni,Tyne, Urien, Ursula of the Silver Host, Vellaunus, Vitiris, White Lady

Egyptian: Gods, Gods Incarnate and Personified Divine Forces:

Amaunet, Amen, Amon, Amun, Anat, Anqet, Antaios, Anubis, Anuket, Apep, Apis, Astarte, Aten, Aton, Atum, Bastet, Bat, Buto, Duamutef, Duamutef, Hapi, Har-pa-khered, Hathor, Hauhet, Heket, Horus, Huh, Imset, Isis, Kauket, Kebechsenef, Khensu, Khepri, Khnemu, Khnum, Khonsu, Kuk, Maahes, Ma'at, Mehen, Meretseger, Min, Mnewer, Mut, Naunet, Nefertem, Neith, Nekhbet, Nephthys, Nun, Nut, Osiris, Ptah, Ra , Re, Renenet, Sakhmet, Satet, Seb, Seker, Sekhmet, Serapis, Serket, Set, Seth, Shai, Shu, Shu, Sia, Sobek, Sokar, Tefnut, Tem, Thoth

Hellenes (Greek) Tradition (Gods, Demigods, Divine Bastards)

Acidalia, Aello, Aesculapius, Agathe, Agdistis, Ageleia, Aglauros, Agne, Agoraia, Agreia, Agreie, Agreiphontes, Agreus, Agrios, Agrotera, Aguieus, Aidoneus, Aigiokhos, Aigletes, Aigobolos, Ainia,Ainippe, Aithuia , Akesios, Akraia, Aktaios, Alalkomene, Alasiotas, Alcibie, Alcinoe, Alcippe, Alcis,Alea, Alexikakos, Aligena, Aliterios, Alkaia, Amaltheia, Ambidexter, Ambologera, Amynomene,Anaduomene, Anaea, Anax, Anaxilea, Androdameia,Andromache, Andromeda, Androphonos, Anosia, Antandre,Antania, Antheus, Anthroporraistes, Antianara, Antianeira, Antibrote, Antimache, Antimachos, Antiope,Antiopeia, Aoide, Apatouria, Aphneius, Aphrodite, Apollo, Apotropaios, Areia, Areia, Areion, Areopagite, Ares, Areto, Areximacha,Argus, Aridnus,Aristaios, Aristomache, Arkhegetes, Arktos, Arretos, Arsenothelys, Artemis, Asclepius, Asklepios, Aspheleios, Asteria, Astraeos , Athene, Auxites, Avaris, Axios, Axios Tauros,Bakcheios, Bakchos, Basileus, Basilis, Bassareus, Bauros, Boophis, Boreas , Botryophoros, Boukeros, Boulaia, Boulaios, Bremusa,Bromios, Byblis,Bythios, Caliope, Cedreatis, Celaneo, centaur, Cerberus, Charidotes, Charybdis, Chimera, Chloe, Chloris , Choreutes, Choroplekes, Chthonios, Clete, Clio, clotho,Clyemne, cockatrice, Crataeis, Custos, Cybebe, Cybele, Cyclops, Daphnaia, Daphnephoros, Deianeira, Deinomache, Delia, Delios, Delphic, Delphinios, Demeter, Dendrites, Derimacheia,Derinoe, Despoina, Dikerotes, Dimeter, Dimorphos, Dindymene, Dioktoros, Dionysos, Discordia, Dissotokos, Dithyrambos, Doris, Dryope,Echephyle,Echidna, Eiraphiotes, Ekstatophoros, Eleemon, Eleuthereus, Eleutherios, Ennosigaios, Enodia, Enodios, Enoplios, Enorches, Enualios, Eos , Epaine, Epidotes, Epikourios, Epipontia, Epitragidia, Epitumbidia, Erato, Ergane, Eribromios, Erigdoupos, Erinus, Eriobea, Eriounios, Eriphos, Eris, Eros,Euanthes, Euaster, Eubouleus, Euboulos, Euios, Eukhaitos, Eukleia, Eukles, Eumache, Eunemos, Euplois, Euros , Eurybe,Euryleia, Euterpe, Fates,Fortuna, Gaia, Gaieokhos, Galea, Gamelia, Gamelios, Gamostolos, Genetor, Genetullis, Geryon, Gethosynos, giants, Gigantophonos, Glaukopis, Gorgons, Gorgopis, Graiae, griffin, Gynaikothoinas, Gynnis, Hagisilaos, Hagnos, Haides, Harmothoe, harpy, Hegemone, Hegemonios, Hekate, Hekatos, Helios, Hellotis, Hephaistia, Hephaistos, Hera, Heraios, Herakles, Herkeios, Hermes, Heros Theos, Hersos, Hestia, Heteira, Hiksios, Hipp, Hippia, Hippios, Hippoi Athanatoi, Hippolyte, Hippolyte II,Hippomache,Hippothoe, Horkos, Hugieia, Hupatos, Hydra, Hypate, Hyperborean, Hypsipyle, Hypsistos, Iakchos, Iatros, Idaia, Invictus, Iphito,Ismenios, Ismenus,Itonia, Kabeiria, Kabeiroi, Kakia, Kallinikos, Kallipugos, Kallisti, Kappotas, Karneios, Karpophoros, Karytis, Kataibates, Katakhthonios, Kathatsios, Keladeine, Keraunos, Kerykes, Khalinitis, Khalkioikos, Kharmon, Khera, Khloe, Khlori,Khloris,Khruse, Khthonia, Khthonios, Kidaria, Kissobryos, Kissokomes, Kissos, Kitharodos, Kleidouchos, Kleoptoleme, Klymenos, Kore, Koruthalia, Korymbophoros, Kourotrophos, Kranaia, Kranaios, Krataiis, Kreousa, Kretogenes, Kriophoros, Kronides, Kronos,Kryphios, Ktesios, Kubebe, Kupris, Kuprogenes, Kurotrophos, Kuthereia, Kybele, Kydoime,Kynthia, Kyrios, Ladon, Lakinia, Lamia, Lampter, Laodoke, Laphria, Lenaios, Leukatas, Leukatas, Leukolenos, Leukophruene, Liknites, Limenia, Limnaios, Limnatis, Logios, Lokhia, Lousia, Loxias, Lukaios, Lukeios, Lyaios, Lygodesma, Lykopis, Lyseus, Lysippe, Maimaktes, Mainomenos, Majestas, Makar, Maleatas, Manikos, Mantis, Marpe, Marpesia, Medusa, Megale, Meilikhios, Melaina, Melainis, Melanaigis, Melanippe,Melete, Melousa, Melpomene, Melqart, Meses, Mimnousa, Minotaur, Mneme, Molpadia,Monogenes, Morpho, Morychos, Musagates, Musagetes, Nebrodes, Nephelegereta, Nereus,Nete, Nike, Nikephoros, Nomios, Nomius, Notos , Nyktelios, Nyktipolos, Nympheuomene, Nysios, Oiketor, Okyale, Okypous, Olumpios, Omadios, Ombrios, Orithia,Orius,Ortheia, Orthos, Ourania, Ourios, Paelemona, Paian, Pais, Palaios, Pallas, Pan Megas, Panakhais, Pandemos, Pandrosos, Pantariste, Parthenos, PAsianax, Pasiphaessa, Pater, Pater, Patroo s, Pegasus, Pelagia, Penthesilea, Perikionios, Persephone, Petraios, Phanes, Phanter, Phatria, Philios, Philippis, Philomeides, Phoebe, Phoebus, Phoenix, Phoibos, Phosphoros, Phratrios, Phutalmios, Physis, Pisto, Plouton, Polemusa,Poliakhos, Polias, Polieus, Polumetis, Polydektes, Polygethes, Polymnia, Polymorphos, Polyonomos, Porne, Poseidon, Potnia Khaos, Potnia Pheron, Promakhos, Pronoia, Propulaios, Propylaia, Proserpine, Prothoe, Protogonos, Prytaneia, Psychopompos, Puronia, Puthios, Pyrgomache, Python, Rhea, Sabazios, Salpinx, satyr, Saxanus, Scyleia,Scylla, sirens, Skeptouchos, Smintheus, Sophia, Sosipolis, Soter, Soteria, Sphinx, Staphylos, Sthenias, Sthenios, Strife, Summakhia, Sykites, Syzygia, Tallaios, Taureos, Taurokeros, Taurophagos, Tauropolos, Tauropon, Tecmessa, Teisipyte, Teleios, Telepyleia,Teletarches, Terpsichore, Thalestris, Thalia, The Dioskouroi, Theos, Theritas, Thermodosa, Thraso, Thyonidas, Thyrsophoros, Tmolene, Toxaris, Toxis, Toxophile,Trevia, Tricephalus, Trieterikos, Trigonos, Trismegestos, Tritogeneia, Tropaios, Trophonius,Tumborukhos, Tyche, Typhon, Urania, Valasca, Xanthippe, Xenios, Zagreus, Zathos, Zephryos , Zeus, Zeus Katakhthonios, Zoophoros Topana

Native American: Gods, Heroes, and Anthropomorphized Facets of Nature

Aakuluujjusi, Ab Kin zoc, Abaangui , Ababinili , Ac Yanto, Acan, Acat, Achiyalatopa , Acna, Acolmiztli, Acolnahuacatl, Acuecucyoticihuati, Adamisil Wedo, Adaox , Adekagagwaa , Adlet , Adlivun, Agloolik , Aguara , Ah Bolom Tzacab, Ah Cancum, Ah Chun Caan, Ah Chuy Kak, Ah Ciliz, Ah Cun Can, Ah Cuxtal, Ah hulneb, Ah Kin, Ah Kumix Uinicob, Ah Mun, Ah Muzencab, Ah Patnar Uinicob, Ah Peku, Ah Puch, Ah Tabai, Ah UincirDz'acab, Ah Uuc Ticab, Ah Wink-ir Masa, Ahau Chamahez, Ahau-Kin, Ahmakiq, Ahnt Alis Pok', Ahnt Kai', Aholi , Ahsonnutli , Ahuic, Ahulane, Aiauh, Aipaloovik , Ajbit, Ajilee , Ajtzak, Akbaalia , Akba-atatdia , Akhlut , Akhushtal, Akna , Akycha, Alaghom Naom Tzentel, Albino Spirit animals , Alektca , Alignak, Allanque , Allowat Sakima , Alom, Alowatsakima , Amaguq , Amala , Amimitl, Amitolane, Amotken , Andaokut , Andiciopec , Anerneq , Anetlacualtiliztli, Angalkuq , Angpetu Wi, Anguta, Angwusnasomtaka , Ani Hyuntikwalaski , Animal spirits , Aningan, Aniwye , Anog Ite , Anpao, Apanuugak , Apicilnic , Apikunni , Apotamkin , Apoyan Tachi , Apozanolotl, Apu Punchau, Aqalax , Arendiwane , Arnakua'gsak , Asdiwal , Asgaya Gigagei, Asiaq , Asin , Asintmah, Atacokai , Atahensic, Aticpac Calqui Cihuatl, Atira, Atisokan , Atius Tirawa , Atl, Atlacamani, Atlacoya, Atlatonin, Atlaua, Atshen , Auilix, Aulanerk , Aumanil , Aunggaak , Aunt Nancy , Awaeh Yegendji , Awakkule , Awitelin Tsta , Awonawilona, Ayauhteotl, Azeban, Baaxpee , Bacabs, Backlum Chaam, Bagucks , Bakbakwalanooksiwae , Balam, Baldhead , Basamacha , Basket Woman , Bead Spitter , Bear , Bear Medicine Woman , Bear Woman , Beaver , Beaver Doctor , Big Heads, Big Man Eater , Big Tail , Big Twisted Flute , Bikeh hozho, Bitol, Black Hactcin , Black Tamanous , Blind Boy , Blind Man , Blood Clot Boy , Bloody Hand , Blue-Jay , Bmola , Bolontiku, Breathmaker, Buffalo , Buluc Chabtan, Burnt Belly , Burnt Face , Butterfly , Cabaguil, Cacoch, Cajolom, Cakulha, Camaxtli, Camozotz, Cannibal Grandmother , Cannibal Woman , Canotila , Capa , Caprakan, Ca-the-ña, Cauac, Centeotl, Centzonuitznaua, Cetan , Chac Uayab Xoc, Chac, Chahnameed , Chakwaina Okya, Chalchihuitlicue, Chalchiuhtlatonal, Chalchiutotolin, Chalmecacihuilt, Chalmecatl, Chamer, Changing Bear Woman , Changing Woman , Chantico, Chaob, Charred Body , Chepi , Chibiabos ,Chibirias, Chiccan, Chicomecoatl, Chicomexochtli, Chiconahui, Chiconahuiehecatl, Chie, Child-Born-in-Jug , Chirakan, Chulyen , Cihuacoatl, Cin-an-ev , Cinteotl, Cipactli, Cirapé , Cit Chac Coh, Cit-Bolon-Tum, Citlalatonac, Citlalicue, Ciucoatl, Ciuteoteo, Cizin, Cliff ogre , Coatlicue, Cochimetl, Cocijo, Colel Cab, Colop U Uichkin, Copil, Coyolxauhqui, Coyopa, Coyote , Cripple Boy , Crow , Crow Woman , Cum hau, Cunawabi , Dagwanoenyent , Dahdahwat , Daldal , Deohako, Dhol , Diyin dine , Djien , Djigonasee , Dohkwibuhch , Dzalarhons , Dzalarhons, Eagentci , Eagle , Earth Shaman , Eeyeekalduk , Ehecatl, Ehlaumel , Eithinoha , Ekchuah, Enumclaw , Eototo, Esaugetuh Emissee , Esceheman, Eschetewuarha, Estanatlehi , Estasanatlehi , Estsanatlehi, Evaki, Evening Star, Ewah , Ewauna, Face , Faces of the Forests , False Faces , Famine , Fastachee , Fire Dogs , First Creator , First Man and First Woman, First Scolder , Flint Man , Flood , Flower Woman , Foot Stuck Child , Ga'an, Ga-gaah , Gahe, Galokwudzuwis , Gaoh, Gawaunduk, Geezhigo-Quae, Gendenwitha, Genetaska, Ghanan, Gitche Manitou, Glispa, Glooskap , Gluscabi , Gluskab , Gluskap, Godasiyo, Gohone , Great Seahouse, Greenmantle , Gucumatz, Gukumatz, Gunnodoyak, Gyhldeptis, Ha Wen Neyu , Hacauitz , Hacha'kyum, Hagondes , Hahgwehdiyu , Hamatsa , Hamedicu, Hanghepi Wi, Hantceiitehi , Haokah , Hastseoltoi, Hastshehogan , He'mask.as , Hen, Heyoka , Hiawatha , Hino, Hisakitaimisi, Hokhokw , Hotoru, Huehuecoyotl, Huehueteotl, Huitaca , Huitzilopochtli, Huixtocihuatl, Hummingbird, Hun hunahpu, Hun Pic Tok, Hunab Ku, Hunahpu Utiu, Hunahpu, Hunahpu-Gutch, Hunhau, Hurakan, Iatiku And Nautsiti, Ich-kanava , Ictinike , Idliragijenget , Idlirvirisong, Igaluk , Ignirtoq , Ikanam , Iktomi , Ilamatecuhtli, Illapa, Ilya p'a, i'noGo tied , Inti, Inua , Ioskeha , Ipalnemohuani, Isakakate, Ishigaq , Isitoq , Issitoq , Ite , Itzamná, Itzananohk`u, Itzlacoliuhque, Itzli, Itzpapalotl, Ix Chebel Yax, Ixbalanque, Ixchel, Ixchup, Ixmucane, Ixpiyacoc, Ixtab, Ixtlilton, Ixtubtin, Ixzaluoh, Iya , Iyatiku , Iztaccihuatl, Iztacmixcohuatl, Jaguar Night, Jaguar Quitze, Jogah , Kaakwha , Kabun , Kabun , Kachinas, Kadlu , Ka-Ha-Si , Ka-Ha-Si , Kaik , Kaiti , Kan, Kana'ti and Selu , Kanati, Kan-u-Uayeyab, Kan-xib-yui, Kapoonis , Katsinas, Keelut , Ketchimanetowa, Ketq Skwaye, Kianto, Kigatilik , Kilya, K'in, Kinich Ahau, Kinich Kakmo, Kishelemukong , Kisin, Kitcki Manitou, Kmukamch , Kokopelli , Ko'lok , Kukulcan, Kushapatshikan , Kutni , Kutya'I , Kwakwakalanooksiwae ,Kwatee , Kwekwaxa'we , Kwikumat , Kyoi , Lagua , Land Otter People , Lawalawa , Logobola , Loha, Lone Man , Long Nose , Loon , Loon Medicine , Loon Woman , Loo-wit, Macaw Woman, Macuilxochitl, Maho Peneta, Mahucutah, Makenaima , Malesk , Malina , Malinalxochi, Malsum, Malsumis , Mam, Mama Cocha, Man in moon , Manabozho , Manetuwak , Mani'to, Manitou , Mannegishi , Manu, Masaya, Masewi , Master of Life , Master Of Winds, Matshishkapeu , Mavutsinim , Mayahuel, Medeoulin , Mekala , Menahka, Meteinuwak , Metztli, Mexitl, Michabo, Mictecacihuatl, Mictlan, Mictlantecuhtli, Mikchich , Mikumwesu , Mitnal, Mixcoatl, Mongwi Kachinum , Morning Star, Motho and Mungo , Mulac, Muut , Muyingwa , Nacon, Nagenatzani, Nagi Tanka , Nagual, Nahual, Nakawé, Nanabojo, Nanabozho , Nanabush, Nanahuatzin, Nanautzin, Nanih Waiya, Nankil'slas , Nanook , Naum, Negafook , Nerrivik , Nesaru, Nianque , Nishanu , Nohochacyum, Nokomis, Nootaikok , North Star, Nujalik , Nukatem , Nunne Chaha , Ocasta, Ockabewis, Odzihozo , Ohtas , Oklatabashih, Old Man , Olelbis, Omacatl, Omecihuatl, Ometecuhtli, Onatha , One Tail of Clear Hair , Oonawieh Unggi , Opochtli, Oshadagea, Owl Woman , Pah , Pah, Paiowa, Pakrokitat , Pana , Patecatl, Pautiwa, Paynal, Pemtemweha , Piasa , Pikváhahirak , Pinga , Pomola , Pot-tilter , Prairie Falcon , Ptehehincalasanwin , Pukkeenegak , Qaholom, Qakma, Qiqirn , Quaoar , Quetzalcoatl, Qumu , Quootis-hooi, Rabbit, Ragno, Raven, Raw Gums , Rukko, Sagamores , Sagapgia , Sanopi , Saynday , Sedna, Selu, Shakuru, Sharkura, Shilup Chito Osh, Shrimp house, Sila , Sint Holo , Sio humis, Sisiutl , Skan , Snallygaster , Sosondowah , South Star, Spider Woman , Sta-au , Stonecoats , Sun, Sungrey , Ta Tanka , Tabaldak , Taime , Taiowa , Talocan, Tans , Taqwus , Tarhuhyiawahku, Tarquiup Inua , Tate , Tawa, Tawiscara, Ta'xet , Tcisaki , Tecciztecatl, Tekkeitserktock, Tekkeitsertok , Telmekic , Teoyaomqui, Tepeu, Tepeyollotl, Teteoinnan, Tezcatlipoca, Thobadestchin, Thoume', Thunder , Thunder Bird , Tieholtsodi, Tihtipihin , Tirawa , Tirawa Atius, Tlacolotl, Tlahuixcalpantecuhtli, Tlaloc, Tlaltecuhtli, Tlauixcalpantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tohil, Tokpela ,Tonantzin , Tonatiuh, To'nenile, Tonenili , Tootega , Torngasak, Torngasoak , Trickster/Transformer , True jaguar, Tsentsa, Tsichtinako, Tsohanoai Tsonoqwa , Tsul 'Kalu , Tulugaak , Tumas , Tunkan ingan, Turquoise Boy , Twin Thunder Boys, Txamsem , Tzakol, Tzitzimime, Uazzale , Uchtsiti, Udó , Uentshukumishiteu , Ueuecoyotl, Ugly Way , Ugni , Uhepono , Uitzilopochtli, Ukat , Underwater Panthers , Unhcegila , Unipkaat , Unk, Unktomi , Untunktahe , Urcaguary, Utea , Uwashil , Vassagijik , Voltan, Wabosso , Wabun , Wachabe, Wah-Kah-Nee, Wakan , Wakanda , Wakan-Tanka, Wakinyan , Wan niomi , Wanagi , Wananikwe , Watavinewa , Water babies , Waukheon , We-gyet , Wemicus , Wendigo , Wentshukumishiteu , White Buffalo Woman, Whope , Wi , Wicahmunga , Wihmunga , Windigo, Winonah, Wisagatcak , Wisagatcak, Wishpoosh , Wiyot , Wovoka , Wuya , Xaman Ek, Xelas , Xibalba, Xilonen, Xipe Totec, Xiuhcoatl, Xiuhtecuhtli, Xiuhtecutli, Xmucane, Xochipili , Xochiquetzal, Xocotl, Xolotl, Xpiyacoc, Xpuch And Xtah, Yacatecuhtli, Yaluk, Yanauluha , Ya-o-gah , Yeba Ka, Yebaad, Yehl , Yeitso, Yiacatecuhtli, Yolkai Estsan, Yoskeha , Yum Kaax, Yuwipi , Zaramama, Zipaltonal, Zotz

Norse Deities, Giants and Monsters:

Aegir, Aesir, Alfrigg, Audumbla, Aurgelmir, Balder, Berchta, Bergelmir, Bor, Bragi, Brisings, Buri, Etin, Fenris, Forseti, Frey, Freyja, Frigga, Gefion, Gerda, Gode, Gymir, Harke, Heimdall, Hel, Hermod, Hodur, Holda, Holle, Honir, Hymir, Idun, Jormungandr, Ljolsalfs, Loki, Magni, Mimir, Mistarblindi, Muspel, Nanna, Nanni, Nerthus, Njord, Norns, Odin, Perchta, Ran, Rig, Segyn, Sif, Skadi, Skirnir, Skuld, Sleipnir, Surt, Svadilfari, tanngniotr, tanngrisnr, Thiassi, Thor, Thrud, Thrudgelmir, Thrym, Thurs, Tyr, Uller, Urd, Vali, Vali, Valkyries, Vanir, Ve, Verdandi, Vidar, Wode, Ymir

Pacific islands: Deities, Demigods and Immortal Monsters:

Abeguwo, Abere, Adaro, Afekan, Ai Tupua'i, 'Aiaru, Ala Muki, Alalahe, Alii Menehune, Aluluei, Aruaka, Asin, Atanea, Audjal, Aumakua, Babamik, Bakoa, Barong, Batara Kala, Buring Une, Darago, Dayang-Raca, De Ai, Dogai, Enda Semangko, Faumea, Giriputri, Goga, Haumea, Hiiaka', Hina, Hine, Hoa-Tapu, 'Imoa, Io, Kanaloa, Kanaloa, Kane, Kapo, Kava, Konori, Ku, Kuhuluhulumanu, Kuklikimoku, Kukoae, Ku'ula, Laka, Laulaati, Lono, Mahiuki, MakeMake, Marruni, Maru, Maui, Melu, Menehune, Moeuhane, MOO-LAU, Ndauthina, Ne Te-reere, Nevinbimbaau, Ngendei, Nobu, Oro, Ove, Paka'a, Papa, Pele, Quat, Rangi, Rati, Rati-mbati-ndua, Ratu-Mai-Mbula, Rua, Ruahatu, Saning Sri, Ta'aroa, Taaroa, Tamakaia, Tane, Tanemahuta, Tangaroa, Tawhaki, Tiki, Tinirau, Tu, Tuli, Turi-a-faumea, Uira, Ukupanipo, Ulupoka, Umboko Indra, Vanuatu, Wahini-Hal, Walutahanga, Wari-Ma-Te-Takere, Whaitiri, Whatu, Wigan

South American: Deities, Demigods, Beings of Divine Substance:

Abaangui, Aclla, Akewa, Asima Si, Atoja, Auchimalgen, Axomama, Bachué, Beru, Bochica, Boiuna, Calounger, Catequil, Cavillaca, Ceiuci, Chasca, Chie, Cocomama, Gaumansuri, Huitaca, Iae, Ilyap'a, Ina, Inti, Ituana, Jamaina , Jandira, Jarina, Jubbu-jang-sangne, Ka-ata-killa, Kilya, Kuat, Kun, Luandinha, Lupi, Mama Allpa, Mama Quilla, Mamacocha, Manco Capac, Maret-Jikky, Maretkhmakniam, Mariana, Oshossi, Pachamac, Pachamama, Perimbó, Rainha Barba, Si, Supai, Topétine, Viracocha, Yemanja (Imanje), Zume

Submitted May 28, 2023 at 04:42PM by dreamer100__ (From Reddit https://ift.tt/uTlQcN4)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

from perkunos to indra & zeus

Anatolian languages:

tarhuan, tarhunna, tarhunnaradu - hittite (linked w bull in anatolia)

tarhu, tarhunz, tarhunta, tarhuwant - luwian

tarhuwanta - palaic

trqqas - lycian

taru - hattian

teshub - hurrian

turvant - sanskrit cognate for indra?

aleppo -

hadad - mesopotamia?

iskur - sumeria?

zeus - greek

indra - vedic

trokondas - rome

jupiter dolichenus - armenian/roman

- associated with sky, weather, lightning, thunder, battlefield, commander, mountains, helpful, slaying enemies with an axe, vanquishing, decided whether would be drought and famine or fertile fields and good harvests, thunderbolt becomes axe

religious treatment

- "Weather god of the thunderbolt, glow on me like the moonlight, shine over me like the son god of heaven!" - KUB 6.45 iii 68-70, Hittite king Muwatalli II’s personal god who he referred to as “my lord, king of heaven” (associated with Anatolia’s bulls instead of horses)

- Hittite king Warpalawas II made rock relief and animals were sacrificed to him

- Luwian magic rituals intended to bring rain or heal the sick

- chief god of the luwians, whose chariot was pulled by horses. later depicted standing on a bull.

- cows + sheep were sacrificed to him for grain + wine to grow

- in curses, he was called upon to “smash enemies with his axe” and gave the king royal power, courage and marched him in battle - in late Luwian texts

- Pegasus, Greek winged horse which carries Zeus’ thunderbolt name comes from one of his epithets piḫaššašši meaning “of the thunderblot”

cult sites

- Aleppo, Syria, major city of the weather god - conquered by Hittite king Suppiluluima I who installed his son Telipinu as priest-king. Temple for weather god was modified to conform to Hittite cult

snake/dragon slayer myth near Mount Kasios in Syria & Corycus in Turkey

- Illuyanka in Hittite

- Hedammu in Hurrian

- Typhon in Greek (taken from Cilicia)

- Naga in Sanskrit

#weather god#zeus#indra#taru#tarhunta#mythology#prehistory#syria#anatolia#india#south asia#levant#archaeology#comparisons#indo european#greek#luwian#anatolian#aleppo#hittite#hurrian#hatti#compare

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Sumerian word for bee was nim-làl", literally "honey fly". In the lexical list ḫar-ra = ḫubullu, tablet XIV, lines 325-327, it is equated with three different Akkadian words: lallartu, nambubtu, and zumbi dišpi (that is also literally "honey fly"). But we know more, as you rightfully pointed out in your original post!

Fun fact: In the Hittite epic about Telipinu, the god of fertility and nature, the bee plays a crucial role: Telipinu is angry, for reasons we do not know since the passage in question is not extant, and he leaves his temple. That causes all kinds of problems because nothing is growing anymore: pregnant animals and humans can't give birth, they are constantly pregnant, the crop dies, nothing can grow anymore. The other deities try to find Telipinu but they fail: the sun god sends an eagle that flies to every corner of the earth, but it cannot find Telipinu. The weather god himself tries to find Telipinu and fails. But the mother goddess Ḫannaḫanna finally sends the bee to find and sting Telipinu. The other deities laugh about this idea, since the bee is so small and has such small wings. The bee does exactly what she was supposed to do: It finds Telipinu and stings him. Telipinu gets angry again. But the other deities and the humans can calm him down by making him his favourite food. He returns to his temple and growth and fertility resume in the country.

It is one of my favourite stories from the Ancient Near East! Unfortunately, we don't know the Hittite word for bee, as the Hittites only ever used the logogram NIM.LÀL in the texts (and that's where I know the word from).

Silim!!

I was thinking about bees (don't we all), and was wondering if you may know/ have sources that may know about beekeeping in Sumer? I know hives have been recorded in Egypt, but wasn't sure what the words and practices were like for Mesopotamia

🐝

Silim! Turns out this answer took more research than I expected, since bees weren't prominent in Mesopotamia as they are today.

Wild bee honey has been harvested across the greater Near East and North Africa for many millennia, dating back at least to the last ice age. Bees were first domesticated and kept in manmade hives around the third millennium BCE in Egypt. They were used for pollination of crops as well as honey production, and honey was both a significant economic product in Egypt (people sometimes paid their taxes in honey!) and a major export from there.

However, beekeeping didn't arrive in Mesopotamia until after the Sumerian period. The earliest references to beekeeping in cuneiform literature come from after 1000 BCE, long after Sumerian was no longer the major spoken language of the region, and bees appear rarely or never in pre-1000 BCE Mesopotamian art.

There are a number of references to honey in Mesopotamian literature; usually it is used as a metaphor for opulence, rarity or sensual pleasure. For example, multiple balbale to Inanna make reference to honey: In Shu-Suen B, it says lale dangega / e kinua lal hab duggaba "let me bring you honey / in the bedchamber dripping sweetly with thick honey" while the Song of the Lettuce has a whole long section about the lu lale "honey-man" shuni lale merini lale "with honey hands, with honey feet". (This "honey-man" is intended to be alluring and praiseworthy, not sticky and gross.) But words like lal "honey" could also mean "date syrup" or other sugary foods, so it's not always clear if specifically bee honey is meant. (I've previously answered about the Sumerian words for "honey" and "beeswax" here.)

In contrast to honey, I can't find a single reference to bees themselves in the entirety of the ETCSL, nor in any of the dictionaries I have access to. They may have had a word for the bee, but given the lack of beekeeping or use of bees in text this word hasn't been passed down to us. The Sumerians' successor, the Akkadians, did have several words for bee, most notably ḫabūbītu, also source of bēt ḫabūbāti "beehive", and nūbtu "honeybee", source of pār nūbti "beeswax".

If anybody has more Mesopotamian bee references, please let me know!

63 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But this only, once again, points to the transitory character of most scholarly categories. More urgent, in the present context, is another phenomenon: the migration and wholesale acceptance not of a single story, but of an entire body of stories, a mythology. The archives of Hattusha not only contained the different versions and translations of Gilgamesh, they presented an extraordinary collection of mythical texts written in Hittite, Hurrian, and Akkadian and concerning divinities who were Hittite (such as Telipinu), Hurrian (such as Kumarbi), Mesopotamian (such as Anu or Enki/Ea), and Ugaritic (such as Baal or Anat). One reason for this variety seems to lie in the character of Hittite domination: the empire was multicultural, and the cults that the king attended to were not just his own ancestral cults, they comprised the worship of various divinities all over his kingdom. Myths were indispensable for the performance of cult- hence their presence in the royal archives. Not that this explains everything; the versions of the Gilgamesh story, for example, must have been collected for reasons not very different from those that make the story still worth reading and thinking about some millennia later: the story has no connection whatsoever with cult but talks about general themes- the quest for friendship and the urge to overcome mortality.

“Myth” by Fritz Graf in Ancient Religions edited by Sarah Iles Johnston (p 55-6)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ah, yes, telipinu, god of “would you please just do your DBT homework already there’s a reason you feel bad”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Telepinu/Talapinu/Talipinu/Telepinus/Telipinu

Origin: Hittite

God of: Farming, Agriculture, Fertility, Storms, & Crops

Popularity: Semi-Popular

Relationships: Son of Tarhunt & Hebat or Teššub and Arinniti, Brother of Inara, & Husband of Hatepuna, Šepuru, &/or Kašha

Epithets: Exalted Son

Worship: Telepinu was honored every nine years with an extravagant autumn festival, where 1,000 sheep and 50 oxen were sacrificed, and an oak tree, the symbol of the god, was planted; He was also invoked in a daily prayer put in place by King Muršili II; His name was adopted by several Hittite kings to honor him.

#mythology#gods#hittite#hittite gods#hittite mythology#farming#agriculture#fertility#storms#crops#agricultural god#fertility god#storm god

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

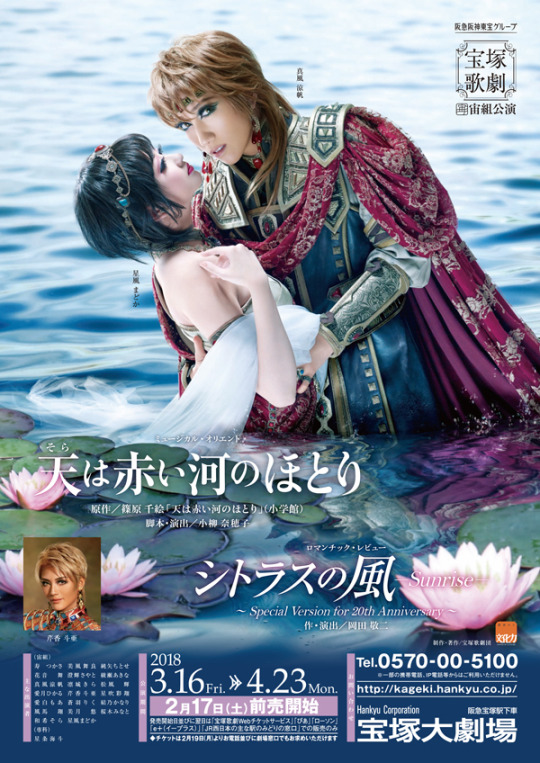

Takarazuka Soragumi All Female Musical Red River/Anatolia Story Roles Announced:

Kail Mursili - Makaze Suzuho

Yuri/ Suzuki Yuri - Hoshikaze Madoka

User Ramses - Serika Toa

Urhi Shalma - Seijou Kaito

King Suppililiuma - Kotobuki Tsukasa

Hathor Nefert - Mikaze Maira

Queen Nakia - Junya Chitose

Princess consort - Kanon Mai

Nefertiti - Sumiki Sayato

Princess consort - Ayase Akina

Kikkuri - Rinjou Kira

Thutmose - Matsukaze Akira

Prince of Darkness Mattiwaza - Aizuki Hikaru

Sari Arnuwanda - Hoshibuki Ayato

Princess consort - Aishiro Moa

Rusafa - Sorahane Riku

Nepis Ilra - Yuino Kanari

Talos - Fuuma Kakeru

Ilbani - Mitsuki Haruka

Princess consort - Hanasaki Airi

Princess consort - Sakurane Rei

Priest - Hoshizuki Rio

Princess consort - Aisaki Maria

Rois Telipinu - Haruse Ouki

Zannanza Hattusili - Sakuragi Minato

Priest - Mirei Jun

Horemheb - Asao Ren

Mali Piyasili - Nanao Maki

Kash - Kazuki Sora

Court Lady - Setohana Mari

Priest - Akine Hikaru

Mittannamuwa - Rui Makise

Hathor Nefert - Haruha Rara

Shubas - Rukaze Hikaru

Nakia (As a young girl) - Hanaki Maia

Himuro Satoshi - Kihou Kanata

Suzuki Eimi - Amase Hatsuhi

Hadi - Amairo Mineri

Zora - Yuuki Shion

Tito - Manami Hikaru

Prince of Darkness Mattizawa (As a young boy) - Takato Chiaki

Urhi (As a young boy) - Manase Mira

Ryui - Mizune Shiho

Shala - Hanamiya Sara

Juda Haspasrupi - Kazeiro Hyuga

Tatukia - Yumeshiro Aya

182 notes

·

View notes

Note

Make me choose: 1. between Telipinu and Muwatalli II, and talk about: 8. a favourite random historical anecdote or fact and 15. a historical headcanon you have :)

Thank you:-D

1. Telipinu or Muwatalli II

Ahahaha, that’s a difficult choice. Both were intelligent and capable, and I love how much Telipinu cared about doing things the civilized way, but... Muwatalli II. Because of the general badassery and those sweet, sweet chariotZ.

8. A random anecdote or fact.

The Zannanza incident! Can’t help but find it fascinating!

I mean... come on.

Suppiluliuma: Don’t mind me, just chillin’, layin’ siege to Karkamis.

Ankhesenamun: Dear foreign king, my husband is dead and I have no sons. I’m a queen, blood of the Gods, and not marrying a servant (particularly not an old & creepy one, tyvm). Plz send me one of your boys to marry and rule the Two Lands, you have enough to spare, don’t you? ;-)

Suppiluliuma: Whut? Nothing like this has happened to me in my entire life! TM. Gotta double-check this.

Ankhesenamun: Hey! Don’t insult me. >_

Suppiluliuma: Well, okay, this seems legit. Zannanza, you go.

Zannanza: ok (goes and gets killed, very likely on Ay’s orders)

Ankhesenamun, probably: ... Why did you have to be such a slowpoke *facepalm*

This says so much about the personalities of everyone involved. One can practically SEE the proud queen put in a desperate situation, and determined to claw her way out of it. The king stroking his chin ponderously while History rushes past him. The young prince, probably apprehensive and excited at the same time. The opportunistic “servant” Ay. And Future! Mursili II just shaking his head in confusion when he remembers all this.

15. A historical headcanon

So, so many.

Enheduanna had a particularly beautiful voice, powerful and clear, and she knew damn well the effect it had on people.

Muwatalli II remembered the names of his fave horses, and spending time with them was his idea of a Good and relaxiing time.

Perikles respected Aspasia’s intelligence much more than he wanted to admit. Even to himself.

Euripides and Aristophanes: one opens his mouth in the other’s presence, and you have a Debate to end all debates. Endless, full of snark and salt, but also genuinely intelligent and well-argued.

Hannibal being a philhellene is canon, but I imagine he was also on excellent terms with the Numidians. Probably learned to ride the Numidian way, spoke the language, knew quite a lot about their traditions, etc.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pantheon universe, a summary

What is the Pantheon universe?

Pantheon is a series of mythological stories that take place from approximately 3000 BCE to 1200 BCE in the area known in modern times as SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa).

The stories assume the existence of each ancient culture’s deities while taking into account the historical conflicts between those cultures, resulting in a kind of “historical mythology” where historical conflict reflects upon the divine realm (E.G.: the Egyptian pantheon fighting the Hittite pantheon and allies in the Battle of Kadesh story).

What tags organize this blog?

Find Pantheon artwork: #iconography

Find Pantheon written work: #textcorpus

Find Pantheon lore (short posts): #lore

Find Papyrus Nabayat content: #papyrusnabayat

Find Baal Cycle content: #baalcycle

Find Battle of Kadesh content: #battleofkadesh

Individual mythology groups have their own tags below, as do some of the gods. Not all gods can be linked below for space reasons, but they are tagged.

Which gods have a prominent place in Pantheon?

Tags below the cut!

Syrian and Amorite Deities - #amorite mythology

Baal, Ugaritic god of storms #baal

Yam, Ugaritic god of the sea #yam

Mot, Ugaritic god of death #mot

Anat, Ugaritic goddess of war #anat

Astarte, Ugaritic goddess of hunting #astarte

Horon, Ugaritic god of exorcism #horon

Resheph, Ugaritic god of war, plague, and healing #resheph

Kothar, Ugaritic god of crafting #kothar

Khasis, Ugaritic goddess of crafting and war #khasis

Gupan, Ugaritic god of vineyards #gupan

Ugar, Ugaritic god of fields #ugar

Egyptian Deities - #egyptian mythology

Sutekh, god of storms, deserts, chaos, war #sutekh

Djehuty, god of knowledge, wisdom, scribes, the moon #djehuty

Hathor, goddess of love, sex, war, the sun, and music #hathor

Usire, god of the underworld and vegetation #usire

Aset, goddess of magic, wisdom, and motherhood #aset

Nebethut, goddess of darkness and mourning #nebethut

Ra, god of the afternoon sun #ra (also #khepri and #atum )

Khonsu, god of the moon, healing, and childhood #khonsu

Heru the Younger, god of kingship, the sun, and the moon #heru

Anpu, god of embalming the underworld #anpu

Ptah, god of crafting and creation #ptah

Sekhmet, goddess of war, plague, fire, healing #sekhmet

Nefertem, god of beauty and lotuses #nefertem

Sokar, god of the Memphite necropolis #sokar

Aten, god of the sun disc #aten

Hatti and Anatolian Deities - #anatolian mythology

Tarhunt, Nesian god of storms, war, and vineyards #tarhunt

Arinna, Hattic goddess of the sun #arinna

Telipinu, Hattic god of storms, fertility, and vegetation #telipinu

Nerik, Hattic god of storms and war #nerik

Ziplantil, Hattic god of storms and the underworld #ziplantil

Inara, Hattic goddess of hunting #inara

Aruna, Luwian god of the sea #aruna

Hasameli, Hattic god of crafting #hasameli

Taru, Hattic-Kaskian god of storms #taru

Zilipuri, Hattic-Kaskian god of crafting #zilipuri

Iluyanka, Hattic-Kaskian god of the Black Sea #iluyanka

Arma, Nesian god of the moon #arma

Kasku, Hattic god of the moon #kasku

Hurrian Deities - #hurrian mythology

Teššub, god of storms #tessub

Sauska, goddess of war and sex #sauska

Tasmisu, god of war #tasmisu

Aranzah, god of the Tigris River #aranzah

Kumarbi, god of grain and the underworld #kumarbi

Hebat, goddess of queenship #hebat

Kiase, god of the sea #kiase

Sarruma, god of the mountains #sarruma

Simige, god of the sun #simige

Kusuh, god of the moon #kusuh

Mukišanu, sukkal of Kumarbi #mukisanu

Impaluri, sukkal of Kiase, #impaluri

Umbu, Alalakhian god of the moon #umbu

Hedammu, god of the sea #hedammu

Sumerian and Babylonian Deities - #babylonian mythology

Enlil, god of storms and wind #enlil

Enki, god of the subterranean waters, crafting, wisdom #enki

Iškur, god of storms #iskur

Marduk, tutelary god of Babylon #marduk

Nabu, god of scribes, knowledge, and wisdom #nabu

Nisaba, goddess of scribes and grain #nisaba

Ninurta, god of war and storms #ninurta

Sharur, divine mace of Ninurta #sharur

Inanna, goddess of war and sexuality #inanna

Nergal, god of war #nergal

Nanna, god of the moon #nanna

Utu, god of the sun #utu

Ereškigal, goddess of the underworld #ereskigal

Assyrian Deities - #assyrian mythology

Aššur, tutelary god of the city Aššur #assur

Adad, Akkadian god of storms and war #adad

Erra, Akkadian god of war, pestilence, fire, and disorder #erra

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The discussion about “literature” in Asia Minor has received new impulses in recent years, in that questions have been raised about the transmission history, origin and compilation, but also about the purpose and sponsorship of such texts. For some time now, literary theories have also been given greater consideration in the development of texts from Asia Minor. Such questions were therefore - in the casual connection to two conferences held in 2003 and 2005, which primarily focused on religious topics of Anatolian tradition - at the center of a symposium in February 2010 in the Department of Religious Studies of the Institute for Oriental and Asian Studies from the University of Bonn. The reference to the two earlier conferences is not only established by the same place of publication, but also, in terms of content, there are undoubtedly points of contact between the history of religion and the history of literature in Hittite Asia Minor; for a considerable part of the written tradition of the Hittites is related to rituals, mythologies and the transmission of religious ideas.

As a pragmatic basis, “literature” was understood as a culture worthy of handing down written material for the symposium's question, without making this description too narrow for the symposium. This made it possible in the context of the contributions to raise a number of questions that could focus on different aspects of the literary tradition of Hittite culture depending on the interests. Some of the questions discussed during the symposium focused on literary theories, and some of the processes of literary production and dissemination were outlined, whereby stylistic forms of expression and motifs in this function were also considered.

Despite the different approaches of the authors, it is not difficult to see thematic similarities in the present volume. Questions of literary theory and literary genres are mainly in the center of the contributions by Birgit Christiansen, Paola Dardano, Amir Gilan, Manfred Hutter, Maria Lepši and Jared L. Miller; Complementary to this literary block are the contributions by Silvia Alaura, José L. García Ramón, Alwin Kloekhorst, Elisabeth Rieken and Zsolt Simon, who examine motifs and linguistic forms of expression in Anatolian texts. How understanding of literature - be it with regard to the statements of a literary work or be it with regard to the conception of such a work - is also promoted by the comparison of texts can be seen in the present volume in the contributions by Sylvia Hutter-Braunsar, Michel Mazoyer, Ian Rutherford, Karl Strobel and Joan Goodnick Westenholz. Finally, the last - no less important - group is the contributions by Gary Beckman, Carlo Corti, Magdalena Kapełuś and Piotr Taracha, who focus on the reconstruction and compilation of individual texts - as the basis for future literary analyzes of these texts.

For the present volume, the individual contributions have been editorially standardized as far as possible, but spellings of names and sometimes also transcriptions of Anatolian words, for which the authors have good reasons, have been left in different forms within the texts. The editorial standardization therefore primarily concerned citation methods and abbreviations, the latter can be broken down using the attached list of abbreviations.

1. The Illuyanka text is undoubtedly one of the best-known Hittite stories. The text was presented by Archibald Sayce in the 1920s. Shortly thereafter, the linguist Walter Porzig drew attention to parallels to the ancient Greek traditions, especially to the Typhon myth. The first "modern" editing of the text was done by Gary Beckman. In the meantime, numerous translations and studies have appeared that illuminate the text from different perspectives. The fascination that the Illuyanka text exudes is partly due to the fact that the myth has been handed down in two different versions - on one and the same board. The text also owes its popularity to the numerous parallels to other narratives of the type "snake dragon slayer". Tales of this kind about a hero who defeats and kills a serpentine dragon have been widespread throughout history in many parts of the world and continue to be so today. They are as good as universal. History can fulfill numerous functions - etiologies of extraordinary natural phenomena, ideological claims to rule, cosmological considerations about the beginnings of the world, religious symbolism or literary entertainment - which often show fairly constant plot structures and are subject to their own narratological logic. As Calvert Watkins (1995) was able to show, many of these narratives also share poetic formulas which are documented for the first time in the Hittite Illuyanka text. It is noticeable that many kite snakes have an affinity for water in common - an ambivalent and conflicting element in itself. "The fundamental element in the dragon’s power is the control of water. Both in its beneficent and destructive aspects water was regarded as animated by the dragon ”, stated G. Elliot Smith (1919: 103). Also Illuyanka, the (eel) snake, if one follows Joshua Katz (1998) and favors the old etymology of Illuyanka as illi / u (eel, English eel) and -anka (snake, cf. Latin anguis) (see now also Melchert, in press), is closely associated with water in both stories. In addition, in many cultures dragons have a special affinity for water sources (Zhao 1992: 113-114), which also play a role in the Illuyanka text. In the ancient Orient, the role of this hero is in most cases a weather god in one of his characters. The role of the enemy is occupied in different epochs and regions of the Ancient Orient by the (primordial) sea and a number of eerie creatures that inhabit it or originate from it. In the Syrian region, the battle of the weather god against têmtum is already mentioned in ancient Babylonian times; in a letter from the ambassador Maris in Aleppo, the weather god of Aleppo traces the kingship back to the investiture of his weapons with which he fought against têmtum (Durand 1993: 41-61; Schwemer 2001, 226-232). The weapons of the weather god from this fight, as well as the mountains Namni and Ḫazzi, are mentioned in the Hittite Bišaiša text (CTH 350), a mythological story that has unfortunately only survived fragmentarily. There the mountain god Bišaisa tells the goddess Ištar - after he raped the sleeping goddess, but was caught by her and begged for his life - about the weapons of the weather god with which he defeated the sea (Schwemer 2001: 233; Haas 2006: 212f .). The famous passage in the Puḫānu text, which is often interpreted as the “crossing of the Taurus”, is in my opinion linked. to this mythologist (Gilan 2004: 277-279). The fight of the weather god against the sea is also a theme of the Hurrian-Hittite Kumarbi cycle. In order to regain control over the world of gods, Kumarbi creates several terrible adversaries who are supposed to defeat the weather god Teššop. Three of these adversaries are closely related to water. At first the sea god himself was an opponent of the weather god. The song from the sea, which is mentioned in Hurrian and Hittite fragmentary myth and ritual fragments as well as in table catalogs, was probably made during a festival for Mount Ḫazzi (Zaphon, Kasion, today Keldağ on the Bay of İskenderun, the scene of many war and dragon stories ) presented.

Ullikummi was also closely associated with water. Another adversary was Ḫedammu, a snake-like monster (André-Salvini / Salvini 1998: 9-10; Dijkstra 2005). Ḫedammu was conceived by Kumarbi with the gigantic daughter of the sea and because of his voracity caused a famine that threatened to destroy mankind. Help was provided by Ištar, who went to the beach for nude bathing, seduced Ḫedammu there, who crawled excitedly out of the water to land, where he met his end. The Ḫedammu story shows many similarities to the first Illuyanka story (most recently Hoffner 2007: 125), while the "Anatolian" myth of "Telipinu and the daughter of the sea" (Hoffner 1998: 26-28; Haas 2006: 115-117) has a lot in common with the second Illuyanka story. In both narratives, a marriage - and the obligation associated with it - served to prevent danger. 2. The great importance of the Illuyanka text for the history of religion, however, is primarily due to the fact that the mythical narratives seem to be embedded in the ritual - an assumption that has strongly influenced the interpretation of the narratives in research. It is precisely this supposed connection between myth and ritual that will occupy me in the following. Before I get into that, however, I would like to briefly outline the scientific discussion about the relationship between myth and ritual, as the discussion is of crucial importance in interpreting the Illuyanka narrative (s). The question of the relationship between myth and ritual has shaped myth and ritual theory like no other since the end of the 19th century. It is associated with scholars such as the Old Testament scholar William Robertson Smith, who was the first to point out "the dependence of myth on ritual". The theory was further developed by Sir James Frazer in his monumental masterpiece "The Golden Bough", which grew from edition to edition. Frazer examined various ancient gods, which he interpreted as vegetation gods - including Adonis, Attis, Demeter, Tammuz, Osiris and Dionysus. The myth of death and resurrection of these deities was ritually performed annually during the New Year celebrations to guarantee the revitalization of the vegetation (Versnel 1990: 29f.). “Under the names of Osiris, Tammuz, Adonis, and Attis, the people of Egypt and Western Asia represented the yearly decay and revival of life, especially of vegetable life, which they personified as a god who died annually and rose again from the dead . In name and detail the rites varied from place to place: in substance they were the same ”(Frazer 1961: 164). Segal (2004: 66) describes the meaning of the myth for Frazer as follows: “Myth gives ritual its original and soul meaning. Without the myth of the death and rebirth of that god, the death and rebirth of the god of vegetation would scarcely be ritualistically enacted. ”In the second, more influential Frazerian myth-ritual theory, the deified king is at the center. To end the winter and to guarantee the food supply, the king is killed by the community as soon as he shows weakness but still has strength. The weak phase of the king is equated with winter. His premature killing is to ensure that the soul of the deity who dwells in him can be transferred to his successor (Segal 2004: 66). The "Cambridge Ritual School" around Gilbert Murray, F.M. Cornford and Jane Ellen Harrison took Frazer's theories further. They transferred Frazer's story of the ritual royal drama - his death and resurrection - to Greek society and saw in this basic ritual structure the origins of Greek mythology and Greek drama (Versnel 1990: 30-35; Bell 1997: 5f.). The ritual was considered the source of the myth. Myths originally emerged only as a textual accompaniment to a ritual: "The primary meaning of myth ... is the spoken correlative of the acted rite, the thing done" (Jane Ellen Harri-son, quoted in Segal 1998: 7). However, myths could live on in literary forms after the rituals from which they arose have long since disappeared (Bell 1997: 6). The Old Testament scholar Samuel Henry Hooke turned to the ancient oriental religions (Versnel 1990: 35-38) and was able to reconstruct a ritual scheme (cult pattern) that is reminiscent of Frazer's ritual royal drama (Segal 1998; 2004: 70-72). Here too, the focus is on the deified king, who represents the deity in the festive ritual. According to Hooke, the following elements belong to the great New Year celebrations - the climax of the cult calendar year - as well as to other rituals (Hooke [1933] in Segal 1998: 88-89):

(1) The dramatic representation of the death and resurrection of the god.

(2) The recitation or symbolic representation of the myth of creation.

(3) The ritual combat, in which the triumph of the god over his enemies was depicted.

(4) The sacred marriage.

(5) The triumphal procession, in which the king played the part of the god followed by a train of lesser gods or visiting deities.

The Babylonian Akītu festival was of central importance for the development of the cult pattern as well as other theories of the myth and ritual school. Scenes such as the humiliation of the king in Esagila on the 5th of Nissanu, the recitation of Enūma eliš in the festival and the so-called Marduk Ordal offered the myth ritualists perfect parallels between king and deity, myth and ritual. For them, the ritual treatment of the king, his humiliation and possible re-enthronement reflected exactly the original mythological event in illo tempore - the fight of Marduk against Ti’amat and her troop of demonic monsters in enūma eliš (Versnel 1990: 36f.). Hooke's ritual narrative was further developed and modified by Theodor Gaster. For Gaster (1954: 198) too, myths are only myths if they are used or used in the ritual. Myths supplement the practical, functional level of the rituals with an eternal, ideal component. The myth "stands in fact in the same relationship to Ritual as God stands to the king, the 'heavenly‘ to the earthly city and so forth "(Gaster 1954: 197f.). With the simultaneous performance of myth and ritual, a cultic drama arises in which the myth is brought to mind (Gaster 1950: 17). The focus of his ritual theory is the seasonal pattern. "Seasonal rituals are functional in character. Their purpose is periodically to revive the topocosm, that is, the entire complex of any given locality conceived as a living organism. They fall into the two clear divisions of Kenosis, or Emptying, and Plerosis, or Filling, the former representing the evacuation of life, the latter its replenishment. Rites of Kenosis include the observance of fasts, lents, and similar austerities, all designed to indicate that the topocosm is in a state of suspended animation. Rites of Plerosis include mock combats against the forces of drought or evil, mass mating, the performance of rain charms and the like, all designed to effect the reinvigoration of the topocosm "(Gaster 1961: 17). In Thespis Gaster (1950: 315-380) offers a selection of ancient oriental mythological texts, partly also in translation, in which he discovered the traces of this seasonal cult scheme, including a number of Hittite texts, myths that are even still in their "original" ritual packaging are handed down. These include the Telipinu myth, the myth of the frost Ḫaḫḫima, the myth of the disappearance and return of the sun deity and The snaring of the Dragon, i.e. the Illuyanka text embedded in the Purulli festival. The myth ritualists gained great influence in many areas of the humanities, especially in literary studies. However, criticism has increased over time. This is why Clyde Kluckhohn (1942: 54) writes in his influential essay: “The whole question of the Primacy of ceremony and Mythology is as meaningless as all questions of the hen or the egg form”, a quote that also inspired the title of this article . Kluckhohn pointed out that myths often appear in connection with rituals, but just as often they do not. Rites and myths can stand in the most varied of relationships to one another, and can also arise in total independence from one another. A myth can contain motifs from other myths; these can be transferred between different cult contexts (Bremmer 1998: 74). Many other critics followed who pointed to errors and misunderstandings in myth and ritual literature and thus shook its foundations. E.g. Kirk (1974: 31-37) comes to the conclusion, based on the Greek material, that the vast majority of Greek myths arose without any special relation to rituals (1974: 253). The mytho-ritualistic interpretation of the Akītu festival was also decidedly rejected (von Soden 1955; Black1981). From today's point of view, the seasonal scheme of parallel mythical and ritual death and resurrection is considered outdated (Smith 1982: 91; Versnel 1990: 44). The works of the myth ritualists have themselves become myths and are particularly interesting from a research historical perspective: "The Study of Ritual arose in an age of Unbounded Confidence in its ability to explain everything fully and scientifically and the construction of Ritual as a category is part of this worldview "(Bell 1997: 21). However, Frazer's great narrative of ritual drama - battle, death, and resurrection - still enjoys popularity. One good reason to deal with Frazer's ritual drama here is above all that this concept shapes the Hittite literature on the Illuyanka text to this day.

3. Volkert Haas undertakes a decidedly Frazerian interpretation of the Illuyanka story, who sees Ḫupašiya as a “kind of priest and year king” who, after a hieros gamos with the goddess, “from a priestess of the Inar (a) to a limited, perhaps even annual, rule cycle would have been killed ”(Haas1982: 45f.). The characterization of the text in its Hittite literary history also has Frazerian roots (Haas 2006: 97): “With the Illuyanka text, there is a seasonal myth in which the order and forces of the cosmos are renewed in the cultic reconstruction of prehistoric events. The myth has been handed down in two versions. At the end of the agricultural year in the autumn after the harvest, the Hittite python Illuyanka, the personification of winter, defeats the weather god Tarhunta, who embodies the forces of spring and who has now ceased to function and is in the power of the Illuyanka during the winter months. At the beginning of spring, with the awakening of the forces of growth, a second battle follows, in which the weather god defeats the Illuyanka with the help of his son or the human Ḫupašiya. The myth that is part of the Old Hittite New Year ritual ends with the etiology of sacred royalty. He was probably also represented by miming. ”- The elements of the Frazerian story cannot be overlooked: ritual drama of primeval times, renewal of the cosmos, order and chaos, revitalization of the forces of nature, the close connection to royalty and the performance in ritual. Some elements of this interpretation have meanwhile been strongly questioned, such as the suggestion to view Ḫupašiya as the king of the year or the cohabitation with Inara as hieros gamos (Hoffner 1998: 11). The identification of the Purulli festival as the Old Ethite New Year festival could not establish itself either (CHD P, 392b; Taracha 2009: 136). Other “mythos-ritualistic” elements are still the state of research. 3.1 This includes embedding the Illuyanka myth in the Purulli festival. In a fundamental essay on Hittite mythology, Hans G. Güterbock set himself the research task of tracing the origins of the various myths and their ways of transmission (Güterbock 1961: 143). "In doing so we immediately make an observation concerning the literary form in which mythological tales have been handed down: only the myths of foreign origin were written as real literary compositions - we may call them epics - whereas those of local Anatolian origin were committed to writing only in connection with rituals. " This distinction between local mythological material embedded in a ritual context and “more literary”, imported mythological narratives of “foreign” origin has since established itself in Hittitology (most recently Lorenz / Rieken 2010). For research in this context, the Illuyanka text represents the prime example of the embedding of myth in the Anatolian cult. As Güterbock (1961: 150f.) Notes: “The text states expressly that the story was recited at the purulli festival of the Storm-god, one of the great yearly cult ceremonies ”. This assessment, too, has practically established itself in Hittitology and has a major impact on the religious-historical interpretation of the two Illuyanka stories. There is far less agreement on the question of whether the myths in the festival were also represented by facial expressions, as Gaster suspected at the time (1950). In his review, Goetze was skeptical about this. The idea came back to life with Pecchioli Daddi's proposal (1987: 361-379; 2010: 261; but see Taracha 2009: 136) to identify the festival ritual for the deity Tetešḫabi (CTH 738) as part of the Purulli festival. She observes (Pecchioli Daddi 1987: 378) that the “daughter of the poor man” functions in the cult of the Teteš “abi, a figure who also plays a role in the second Illuyanka story and leads to the assumption that the myth is in the cult facial expressions (Haas 1988: 286). In addition, the connections between myth and ritual in the Illuyanka text are varied and complex. The Illuyanka stories were recorded on a board along with "ritual descriptions" which may, but not necessarily, represent parts of the Purulli festival. In addition, the first Illuyanka story also provides the aetiology for the Purulli festival celebrated in spring (Goetze 1952: 99; Neu 1990: 103; Klinger 2007: 72).

3.2 The Illuyanka stories are often interpreted as seasonal myths which symbolically represent the regeneration of nature, if not even magically bring it about. According to this interpretation, the defeat of the weather god, who is the lord of rain, endangers nature and agriculture (Hoffner 2007: 124). The eventual victory of the weather god symbolizes the revival of the vegetation in spring (Schwemer 2008: 24). Illuyanka's role is interpreted differently as the personification of winter (Neu 1990: 103; Haas 2006: 97), the Kaškäer (Gonnet 1987: 93-95) or, in my opinion, true as the master of underground water (Hoffner 2007: 124). 3.3 A close relationship between the narratives and the Hittite kingdom is postulated. "The mythic story about the dragon Illuyanka could be interpreted as an aetiological legitimation of the invention of kingship ... very secure are the close ties between the Hittite kings and the festival respectively the place where the mythological drama is located - namely the city of Nerik "(Klinger 2009: 99). The close connection to royalty is primarily based on the identification of Ḫupašiya as an archaic, mythological king as well as on the role of the goddess Inara as the protective deity of Ḫattuša with close connections to the Hittite kingdom. But can the Illuyanka text meet all of these expectations? 4. The text (CTH 321) has survived in eight or nine Young Hittite copies - the affiliation of duplicate J (KUB 36.53) in Košak's Concordance has meanwhile been disputed - but the text contains linguistic archaisms that could refer to an older model. Hoffner (2007: 122) notes the small number of archaisms which for Klinger (2009: 100) show “the characteristic features of a moderately modernized text typical of the process of copying an older tablet”. The text itself is introduced as the speech of Kella, the GUDU priest of the weather god of Nerik. The GUDU priest was part of the basic equipment of Hittite temples and was mainly anchored in the northern and central Anatolian, Hittite-Hittite cult tradition. He served in traditional Anatolian cult centers such as Nerik, Zipplanda or Arinna and was primarily active as an incantation priest and as a reciter in festive events (most recently Taggar-Cohen 2006: 229-278; Taracha 2009: 66). As the report of a GUDU priest, however, the Illuyanka text is quite singular. In reality, the text is unique in itself, a property that unfortunately went relatively uncommented in research. In contrast to other mythological texts of Anatolian tradition, the Illuyanka text does not represent a mūgawar "invocation" and did not serve to appease and bring about disappeared deities (Lepši 2009: 23). The text is not a festive ritual text and does not contain any magical practices (but now see Lorenz / Rieken 2010: 219). I will come back to the genre definition of the text, but first we will deal with the question of how myth and ritual are embedded. The text is presented in the words of Kella (KBo 3.7 i 1-11 with duplicate KBo 12.83): [U]MMA mKell[a LÚGUDU12] ŠA d10 URUNerik nepišaš dI[ŠKUR-ḫ]u-[n]a? purulliyaš uttar nu mān kiššan taranzi utne=wa māu šešdu nu=wa utnē paḫšanuwan ēšdu nu mān māi šešzi nu EZEN4 purulliyaš iyanzi mān dIŠKUR-aš MUŠIlluyankašš=a INA URUKiškilušša arga(-)tiēr nu=za MUŠIlluyankaš dIŠKUR-an taraḫta

As follows Kell [a, the GUDU12 priest of the] weather god of Nerik: This (is) the word / matter of the purulli [...] of the weather god of heaven. When one says in this way: “Let the land prosper and multiply! - The land should be protected! ”And as soon as / so that it flourishes and multiplies, the purulli festival is celebrated. When the weather god and the snake fought in Kiškilušša, the snake defeated the weather god. The rest of the story should be known. The weather god begs all gods for help, the goddess Inara prepares a festival and brings Ḫupašiya to help. Ḫupašiya shows himself to be helpful, but demands in return to sleep with the goddess. The snake and its children are lured out of their hole in the ground; they eat and drink too much; The story, however, follows Inara, the actual heroine of the story (Pecchioli Daddi / Polvani 1990: 42), who builds a house for herself on a rock in the country of Tarukka and lets Ḫupašiya quarter there on the condition that he never looks out the window . But the relationship does not last longer than 20 days, because aupašiya does what he is not allowed to do. It is unclear whether Inara Ḫupašiya ultimately kills, but it is often suspected. For our question, the last paragraph in history is of particular interest (KBo 3.7 ii 15'-20'):

Inaraš INA URUKiškil[ušša wit] É-ŠU ḫunḫuwanašš[=a ÍD ANA] QATI LUGAL mān dāi[š] ḫa[nt]ezziyan purull[iyan] kuit iyaueni Ù QAT [LUGAL É-ir] dInaraš ḫunḫuwanašš=a ÍD […]

Inara [came] to Kiškil [ušša]. And when she put her house and [the river] of underground water [in] the hand of the king [...] - that's why / since then we celebrate the first purull [i] festival - and the hand [of the The king is said to be the house] of the Inara and the [river] of the underground water [...] So much for the first and longer mythical story. However, it cannot be overlooked that nowhere does the text suggest that the snake narrative is recited in the Purulli festival itself, as is so often assumed. At the beginning (lines 4-8), Kella explains to his addressees what Purulli actually means: A spring festival that is celebrated as soon as the land flourishes and multiplies (with Hoffner 2007: 131) or so that it flourishes and multiplies, as it did recently Melchert (in press), who revived Stefanini's suggestion (Pecchioli Daddi / Polvani 1990: 50) that it should be read here as a final conjugation, exceptionally and depending on the context. The cited speech "from the cult event" is clearly limited to the short blessing. Immediately afterwards, Kella begins to tell the first snake story. As the end of the story (lines 15-20) makes clear, with his first myth, Kella provides an etiology for what he believes was the first / original Purulli festival. The addressees of this speech are not the festival participants in Nerik / Kiškilušša, but the recipients of the text in Ḫattuša, who are informed by Kella about the meaning of the festival and its history. The widespread assumption that the myth was presented at the Purulli festival itself cannot be confirmed in the Illuyanka text itself. The brevity and the unadorned style of the narrative - epithets are missing e.g. completely - speak against the assumption that the story, at least in this form, was ever presented in a festive manner (Lepši 2009: 23). Can the presumption of recitation be explained as a projection of myth and ritual theory, originating in analogy to the Babylonian Akītu festival? Kiškilušša, however, is far from Babylon in many ways. If the Illuyanka myth was not recited during cult events, as is so often assumed, the assumption that the story symbolized the regeneration of the forces of nature, even magically and creatively caused it, becomes all the more improbable. The substance of the story itself speaks against this assumption; Hoffner (2007: 129) rightly remarks: "Unlike the so-called Disappearing Deity Myths the text does not elaborate the natural catastrophes that must have followed from the Storm-god’s disablement." Nor does he describe the healing states afterwards. The narrator's interest is obviously elsewhere. Kella only wants to explain how it came about that Inara placed her house and the river of underground water in the hands of the king (KBo 3.7 ii 15-19), an event that founded the first Purulli festival for him. As Gary Beckman (1982: 24) rightly remarked, the handover is the etiology for a royal cult in Kiškilušša, a scarcely occupied village not far from Tarukka, which, however, claims to be the site of a large one primeval struggle, the traces of which could still be seen in cultural legacies (the house on a rock in the Tarukka country) and in local, extraordinary natural phenomena (the flow of underground water) (Hoffner 2007: 126-127). Only the victory over the snake made the handover by Inara possible, who in turn founded the first / original Purulli festival for the weather god of the sky (KBo 3.7 i 2).