#atots analysis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i know its been said before but what the fuck ford. 😇😇 your brother, known dumbass, spent over half his life fixing his mistake, SAVING you, without knowing if it'd work, or if you were even alive, and then the first thing you do is SOCK HIM IN THE FACE. i love you babygirl but stan is literal saint dont touch my ANGEL..........

started thinking of this when i was rewatching of AToTS rn and how when stan first sees ford he opens his arms to hug him (and then ford punches him) but when mabel was telling them to "hug it out" ford actually looks back at stan like Wow alex hirsch i am going to END IT ALL....

anyway i Love my angels stanley Pines and STANFORD FILBRICK PINES (even if theyre a Little gay)

#gravity falls#gf#stanford pines#stanley pines#a tale of two stans#AToTS#FREAKING OUT#beating up my ford plushie rn#i love u bookie bear ford but i’ll acyually fuck you up if youre mean2 stan again.....#ON SITE BUDDY..#all jokes i have a serious analysis of AToTS that im not fully done with#allies blurbs

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

so i've always related more to dipper, for many reasons that aren't worth mentioning now, but recently i had a thought that made me take pause...

i've always related to mabel's gut instinct to make a joke or goad others, especially my family, with silly jokes or bits or whatnot. at least for myself, this gut instinct to make others laugh isn't always just for the sake of making a joke. i mean, yeah, i enjoy a good bit myself, but i know the real reason is something much deeper.

in the book of bill, we learn that mabel and dipper's parents are in the middle of a divorce, or at least gearing up for one, at any rate. while it seems like mainly dipper is affected by this in tbob, at least in his nightmares, i 100% believe that mabel knows about it, and is probably just as affected. only, she has a different reaction.

mabel's a do-er, whereas dipper is more the stew in it and let it consume him type of person. i believe she's an extremely emotionally intelligent person.

the girl literally carried around a list where she kept tabs on the emotional states of all of her friends and felt an extreme desire to “fix” their sadness and in turn, hers. she notices when the people around her are upset, and it makes her uncomfortable. she sees it as a problem to be solved rather than something she should let others deal with on their own terms.

and, yeah, i know what you're thinking. mabel's a child. she's silly and funny and makes jokes because that's what kids do. but it's also a defense mechanism children develop, and it’s rooted in childhood trauma (like witnessing longstanding domestic disputes, parents who can't emotionally regulate, etc.) this desire to constantly keep tabs on how others are feeling keeps us safe — if we've grown up in environments where people may lash out if they're experiencing turbulent emotions or longstanding fights.

my point is: mabel is portrayed as being silly and “unserious” but really she uses humor and optimism as a shield, taking on immense emotional labor for her friends and family and trying oh so desperately to bear the weight of others’ hardships. i think its a wonderful argument against the “mabel is selfish” crowd. she's avoidant, sometimes, under extreme duress, and other times she's proactive in tracking the emotional states of the people in her life.

#gravity falls#mabel pines#character analysis#back to analyzing gf characters#i want to be a fly on the wall in the pines home and psychoanalyze everyone#children parenting parents#dont get me started on atots#she definitely overheard that fight

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS A MUST-READ if you've watched and appreciated Mix Sahaphap's work (and even if you've not). A wonderful analysis and I must doff my hat and bow 🤩🙌

Mix Sahaphap gets to perform (and has the performance chops to perform) in a style that I’ve never seen any other male actor get to embody. Mix gets to unironically play the #strongfemalecharacter. The Beatrice, the Elizabeth Bennett, the Jo March. Strong-willed, emotional, kind-hearted.

Not only the the plot points line up, but Mix, more than any BL actor I’ve seen, fully leans into the embodiment of this archetype. In his roles, he rolls his eyes, pouts, banters flirtatiously, softens his posture and expression at small details. He doesn’t over-exaggerate and imposition other characters but his face also doesn’t hold back his character’s thoughts and judgments. And when the moments arrive, he lets all the hurt and anguish pour out in shatters of tears and visible heartbreak—the star-counting scene, anyone????—in a way that harkens to the operatic emotionality of well-done melodramas, soap-operas, and their contemporary Thai equivalent of Lakorn. It’s only that these have never been men’s roles in those.

It’s no surprise that one of Mix’s roles—Cupid’s Last Wish—is explicitly a gender body-swap, and Tian in A Tale of Thousand Stars is (albeit explicitly denied within the show) heavily connected to gender body-swapping. What Mix specializes in as an actor, and does exceptionally well, has been defined as feminine. To depict a kind of queer expression in this style is novel because it’s not camp, it’s not okama, it’s not a soft or femboy, it’s not a BL twink (Mix has been mostly excluded from the schoolyards and quads of the BL universe except for a role as a senior crush in Fish Upon the Sky). It’s too sincere and too adult for any of that.

In Moonlight Chicken we get to see, without the pretense of gendered mysticism, this performance style’s seduction, warmth, wit, and explosiveness within the framework of a general gay form of expression. It says that this kind of femininity might just be a gay thing. Not all gay men exhibit it, obviously—queer men aren’t a monolith. Still, it gives us something to consider about how we observe performance of queerness on screen, especially in front of an audience that puts so much more emphasis on ships, heat, and pairing chemistry to assess how well they perform a BL role. Could we look for other features to judge performance of queerness instead of how well they kiss?

Seme and uke roles would be the major performance style categories loyal BL fans assess actors with, yet even within the archetype his character’s fill within BL narratives, Mix’s performances differ from the typical uke depiction in BL because he really doesn’t perform them as passive. Rather, Mix’s characters and his portrayal of them are dynamic and demanding. It certainly fits certain stereotypes of ukes (Gilbert!) and their gay stereotype equivalent of bottoms as pillow princesses and brats. Mix’s characters, though, have more drive, agency, and compassion than that, and he plays them with all of those currents running underneath.

We certainly have openly gay writer/director Aof Noppharnach to thank for writing this kind of queer character for Mix to play in Tian and Wen. But for Mix’s specific commitment to the performance starting off with his (debut!?) role in ATOTS, we first have Earth to thank for believing in Mix’s ability and recommending him to portray the role of Tian, and then Aof’s acceptance despite his differing initial expectations for the character. Mix, Earth, and Aof have all been open about how Mix in his personal life and nature holds a lot of similarities to both his role as Tian in ATOTS and Wen in Moonlight Chicken. Some people might knock points off his performances because he’s like them. But his relationship to the characters, rather than dampening my enthusiasm for Mix’s performances, helps me appreciate his willingness to give an authentic performance in a style that hasn’t been encouraged on screens previously. It’s made more impactful that he chose to risk vulnerability to bring something personal that had previously been excluded from screens because of its gender deviance (and in broader society explicitly condemned). This doesn’t make a claim on Mix’s actual identity, but simply shows his willingness to understand and perform the expressions of his queer characters with an effort at empathy that many other actors would feel challenged to bring.

Some actors are chameleons, but some actors have a gift of a type within which they can explore depths and range that no one else can best. For me, that’s what Mix does in his work when directors and casting understands his talent. There’s a BTS video of Mix actually fainting during a scene while in Earth/Phupa’s embrace on the mountain that immediately brought to mind the wildly famous final scene in the film Camille where Greta Garbo as Camille dies in her lover’s arms.

For Mix, it was a serious incident due to regrettably extreme conditions and requiring the on-set paramedics, but these levels of theatrics, for me, are emblematic of what Mix is capable of as a performer, as well. After all, he had to faint in Phupa’s arms multiple times on purpose. It’s the kinds of Old Hollywood and heightened sentimental romance realms Mix takes his performances to! Then he can turn around and make it look easy to take that same character into grounded quips or dedicated everyday tasks. It only takes writers, directors, and audiences willing to see that men can feel this way and act this way. Mix has paved the way.

#mix sahaphap#oh wow i wasn't expecting something like this years after atots and mlc#plus i'm not that much a fan of mix's#but this is an excellent EXCELLENT analysis of mix and his acting#with references to wider bl and thai lakorn#and even old hollywood#i love this 😍#so wonderful to read#thanks so much op!#a tale of thousand stars#atots#moonlight chicken

848 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stan twins: codependency & identity issues

“I tell you it’s unnatural for siblings to get along as well as you do,” says Stan to Dipper and Mabel in Not What He Seems, clearly missing his own relationship with Ford before things started to change. “We used to be like Dipper and Mabel,” says Ford in Weirdmageddon 3: Take Back the Falls. Were they really, though?

I think what many people don’t get about Stan and Ford’s dynamic as children, or even as teenagers, is that, no matter what Stan and Ford think or say about it, they were not like Mabel and Dipper. That just highlights their lack of self-awareness. Here’s a canon analysis for anyone who cares to understand my point:

Mabel and Dipper have overall very different interests and hobbies and act separately on them. They have other friends and spend time with them—well, at least Mabel has Candy and Grenda, as the bubbly social butterfly she is; Dipper, on the other hand, seems way more preoccupied with deciphering the mysteries of Journal 3, but doesn’t miss an opportunity to be included in Wendy’s cool teenage group, as seen in episodes The Inconveniencing and The Love God (in the latter, he seems to be actually succeeding). As fraternal twins of different genders, no matter how alike they look (and despite Mabel’s joke of being “girl Dipper”), they still manage to retain pretty distinct identities. No issue here.

Mabel does her sleepovers, goes to boy band shows, and has encounters with potential crushes. When a surprised Dipper asks her about her vampire love in The Deep End, she points out, “I don’t tell you everything.” Dipper, meanwhile, explored the town with Soos, went to Wendy’s house, hung out with her teen gang, and overall lived many adventures without Mabel, such as trying to prove himself a man with help of the Manotaurs. I think the episode that shows the healthy independence Dipper and Mabel had from each other the best is probably Carpe Diem, inspired in Alex’s real life frustration with his sister, Ariel, but it can be observed all through the series:

What is shown to us in AToTS already differs from that. The Stan twins were inseparable, and each other’s only friends, as Stan establishes early on in his narrative: “Those bullies may have been right about us not making many friends, but when push comes to shove, you only really need one.”

With his question to Ford in the Lost Legends comic, The Jersey Devil’s in the Details, Stan implies they really did everything together, in a way reminiscent of Phineas and Ferb: “So what’re we gonna do today, buddy?”

Even small details, like the toys in their room, served to show the difference between the Stans and Dipper & Mabel, as Matt Chapman clarifies on the episode’s official commentary:

You also see that at this age, all the stuff that would cross over, that would appeal to both of them. You know, it’s not just like, oh, there’s science stuff here and then there’s like—I don’t know—what little Stan would be into. It’s like, no, they both like all this.

“But Mabel was just as desperate in Dipper and Mabel vs the Future as Stan was in A Tale of Two Stans!” Yes, true. She was, and I do believe her relationship with Dipper was the most important one in her life. But do you think the facts that a) she was already terrified of growing up, as shown in the episode Summerween, b) Candy and Grenda declined her invitations to their birthday party, c) Wendy showed her the apparently terrible reality of being a teenager, and d) Stan told her that it would be fine because at least she would always have Dipper... had nothing to with it? Originally her parents were going to forbid her from bringing Waddles to Piedmont, as revealed in the episode commentary of Dipper and Mabel vs. the Future, as just one more heartbreaking thing on the pile of Mabel’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. (Of course, teen Stan’s circumstances were aggravated by the bad home situation he was being “left alone” in by Ford—just like Mabel! Whose parents were arguing, per TBoB canon, to the point of giving Dipper recurring nightmares.)

Another very important thing is that the poor girl was twelve years old, while Stan was presumably seventeen-ish, an age at which separation would be normal and even expected, with the time for college approaching. In fact, differently from what happened with Mabel, whose imminent separation from Dipper came out of left field through an unexpected proposal by Ford (foreshadowed only by her slight discomfort over how close Ford and Dipper were becoming), there was a blatant rift between the teen Stans that Ford went so far as to acknowledge to Stan’s face. Using Stan’s own words from the Land Before Swine commentary: “Anyway, cut to high school, the guy’s never kissed a girl, prom is coming up, and he asked me for advice. ‘Stanley, I know things have been a little weird between you and me with college, but can you talk to me about girls?’” That was before prom (the one in which a girl threw fruit punch at Ford), mind you.

And still, this is what Stan thinks when he realizes Ford is going to accept the scholarship: “Without Ford, I was just half of a dynamic duo. I couldn’t make it without him.” He saw himself as only half of a whole—no wonder, with the way both twins were pushed to believe this since their birth, when they were both named Stan.

When asked about Shermie, Alex observed that a crucial part of their dynamic is that they only had each other. No younger or older brother to support them. The quote from HanaHyperfixates’ and ThatGFFan’s interview:

In terms of Shermie, I remember asking Rob or somebody at some point, like, “Would Shermie be here, logically? Do we have to see him?” I don’t really wanna see him. I’m not interested in that. I’m interested in Stan and Ford being—sort of having only each other and then losing each other because of their different life paths.

I think the suggestion was, “Maybe Shermie would be a baby. Maybe that would happen.” And being like, “okay sure.”

Let’s not forget, too, the only time Ford ever mentions Shermie in Journal 3—“Sherman Pines’s,” surname and all:

From my own observations about their parents, that point is only driven further home.

Filbrick is, well, Filbrick. I don’t think I need to explain much here; every one of us has different interpretations and headcanons about him, but they seem to all agree on the common factor he wasn’t a good father—how much that can be justified by their time period or stretched to accommodate the most heartwrenching stangst is up for debate, just not a subject for this post.

Caryn is more complicated. I think Filbrick was definitely ‘worse’ than her, so to speak, at least in a more obvious way, and she has canonically demonstrated considerable fondness for Stan in particular—according to her, Stan’s rambunctiousness can be attributed to an excess of “personality,” he’s her “little free spirit.” She was, most notably, one of the two people present at Stan’s funeral if the info on the new website is to be trusted. We see her smiling brightly in the picture of the baby Stan twins included in TBoB, which hints at the fact she indeed liked her kids.

But the fact that she, as an adult, didn’t intervene when Stan was kicked out is simply, in my point of view, inexcusable. One could say she was momentarily paralyzed from an overwhelming fear of Filbrick, as a supposed victim herself, but a) that’s already entering headcanon domain, and b) I think that’s far from the truth and directly contradicting the comics, in which she looks happy and relaxed in the company of Filbrick: initiating contact and kissing him on the cheek, comfortingly stroking his back, looking at him with can only be described as tenderness... I don’t think Filbrick is meant to be seen as a monster, not in an exaggerated way. (He’s shown to be touched by Stan’s little stunt with the golden chain, too.) Just a really shitty father, in a common, boring, more nuanced, no less traumatizing, way.

Borrowing a paragraph from a previous analysis:

To me, the most telling thing of all is the fact Stan calls for Ford to help him, not his own mother. Ford, his brother, same age as him, who was at the moment beyond furious with him and very unlikely to show any compassion. Ford, whose attempts to change Filbrick’s mind would more likely than not have been unsuccessful. Not Caryn, adult, who probably had much greater sway over Filbrick. They say a child’s first instinct is to call for their mama. Clearly not in this case!

I’m not saying, here, that Caryn didn’t care about her boys. I elaborate more on her in the meta referenced above, here.

I find it adorable how easily, without any previous prompting, baby Stanley opens up to Ford about his feelings in the comics. The sheer vulnerability of this moment, seeking Ford’s reassurance that he wasn’t a bad kid; the implicit, profound trust, especially coming from someone like Stan, who grows into a man packed to the gills with toxic masculinity due to what he learned from his father. And the manner in which Ford gently comforts him, as if he were used to doing so. As Stan, too, had been shown to do when Crampelter mocked Ford’s fingers. They were clearly accustomed to being each other’s emotional pillars, in the way that kids who learned early on that they can’t count on adults or lean on the authority figures in their lives start building their own little safe space.

The way I see it, the Stan twins got along extremely well, for better or for worse. No obnoxious sibling bickering. No fights and conflict. How could they? They were literally each other’s only friend. If anything, their first major fight was caused by lack of communication, among many other things; they repressed their frustrations with each other to a ridiculous point instead of simply externalizing them like you would expect of an average sibling dynamic.

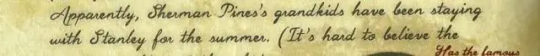

Second of all, they were monozygotic aka identical twins, as strongly hinted in the show, comics, and books, and as confirmed by Alex on the TBoB website, the behind-the-scenes DVD commentaries, and Twitter. The first mention of it, in 2015, below:

They were both named Stan, they had the same face. I’ve read irl identical twins’ confessions about the nature of such a relationship re: identity issues and how people tend to treat you, and it’s often not pretty. In the Stan twins’ case, their sense of identity was beyond blurry, and it’s not difficult to see why. If you pay attention to the show or the comics, you’ll see many hints of this unhealthiness: the way they were both called to the principal’s office (“Pines twins,” even though only Ford was an interested party), the way Stan was called “a dumber, sweatier version” of Ford by Crampelter, the way they had already pretended to be each other before, not in their childhood but adolescence (Stan’s idea, according to hilarious extra material in the DVDs).

Baby Ford, in the comics, has demonstrated a tendency to shoulder the blame that should only be attributed to Stan. For example, when he exclaims, “Oh my God! We killed the Sibling Brothers!” Ford, honey, if anyone had killed the Sibling Brothers, it would’ve been your brother, the person who shoved them in the first place. Not you.

I find it adorable that he also grounded himself for Stan! Filbrick had been very clear about grounding Stan, only, not both twins. But Ford stays with him as if he were grounded as well, as if he didn’t even have a choice. Where Stan was, there was Ford, not far behind.

They were an unit. Inseparable. As simple as that.

Until they weren’t.

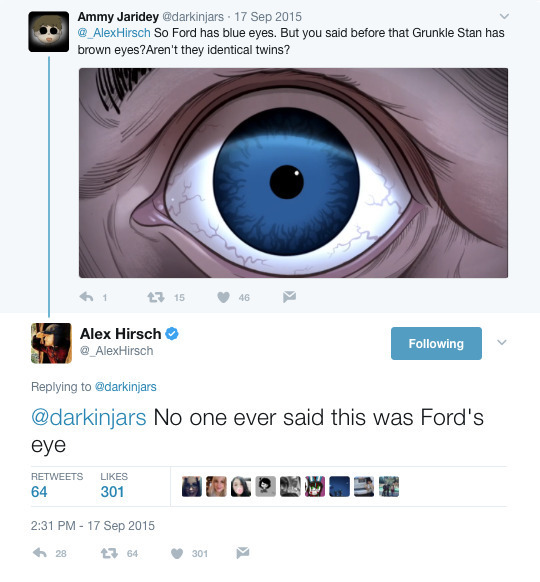

The science fair incident happens, of course—and it’s worth noting Ford doesn’t consider the possibility that Stan sabotaged him out of jealousy or envy of his success for even a second! Instead, he immediately assumes Stan broke his machine so Ford would stay with him!

Did their codependency end with their separation, then? I’ve seen many people believing that yes, it did.

But mullet!Stan, now an adult, ten years after his fight with Ford, still resents Ford for not staying with him “forever”:

Not only that, but as Rob Renzetti (who is Gravity Falls’ supervising producer and story editor and the co-author of Journal 3) phrased it in this separate interview by HanaHyperfixates, Ford’s absence in Stan’s life haunted him and shaped all his relationships:

Um, I mean, to me that’s—I mean, really, Stan—Stan’s life has been… it’s been… sad, and lonely, since—he really… his brother was his best friend, and he loved him so, and I don’t think, you know, I don’t think any other relationship ever worked out for him, because of what happened between him and his brother.

And by the end of it all, you get Bill calling Stan “co-dependant” (British Bill?) on the TBoB website:

I know you might think, at first, that we should take Bill’s insults with a grain of salt, since he’s 1) Bill and 2) petty and desperate. But Bill has also a track record of trying to hit where he thinks will hurt the most, and he knows people. His insult here is not an isolated thing either. It might have been easily dismissed, I agree, if not for all the other evidence for the Stans’ codependency that I’m currently showing you. It’s just one proof out of many, just reinforcing an idea that’s already presented quite clearly.

If you’re still not convinced, Alex has revealed in HanaHyperfixates and ThatGFFan’s interview that Ford’s entire character was built around the type of person that could plausibility explain Stan’s neediness:

Ford was very much us building backwards. The same way you know a black hole is there by the light warped around it, it’s like, you know the damage someone’s family has done to them by all of their weird tics and behaviors. So who is the character who would result in Stan being this hurt and needy and mad and also longing?

But Stan’s codependency, imo, was always easier to see than Ford’s, to the point people mistakenly think Stan cared more about Ford than Ford about him. (I’ve dedicated an entire meta to debunking that assumption as well, here.)

In the commentary of Society of the Blind Eye, though, Alex added, referring to Ford and Fiddleford’s friendship:

Ford as somebody who lost Stan is kinda looking for—even though he rejected his brother, he kinda needs, he needs that other person, and he tried to find that in this kinda sweet prodigy and he just pushed him too far.

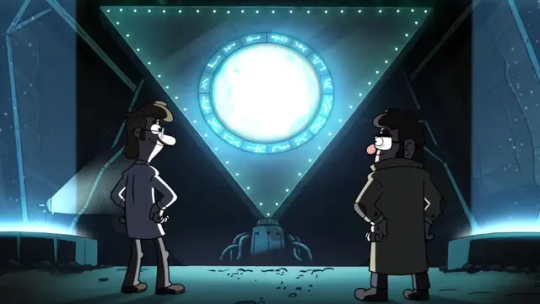

What Alex said about Ford’s relationship with Fiddleford can easily be applied to Ford’s relationship with Bill and with Dipper, since Ford needs “that other person,” needs to be one half of a duo. Ford has tried to recreate his dynamic with Stan again, and again, and again:

And then, of course, we have Ford’s proposal.

What’s really cool about this first image (below) is that it was drawn before Stan even accepted Ford’s proposal, and parallels their childhood picture in Ford’s pocket (one that, per Word of God, Ford has always carried with him, even before his portal days, as explained here) in a very obvious manner:

Ford was already excitedly fantasizing, drawing fanart of them together, picking their outfits and the name of the boat.

But more than that, he also says:

[...] I think it’s time for the Pines twins to join forces again. At least, I hope so. I haven’t discussed my idea with Stan yet. But if I know my brother, he will jump at the chance to find “money and babes.”

And this, to me, expresses both his hope that Stan would welcome his idea and agree to sail away with him and his almost certainty that it is exactly what is going to happen. Ford does mention Stan’s love for “money and babes,” but do you guys think Ford didn’t know what (or better yet, whom) Stan actually loved? In AToTS, Journal 3, and TBoB’s new canon material, we can observe that same certainty. In all three instances, Ford immediately assumes that Stan will show up and come for his call via postcard with no indication whatsoever that the possibility of Stan declining showed up in his mind.

Alex has also commented, in the first interview I’ve referenced:

Those characters at sea—it was so rich. They’re really really funny, because they both have major major blind spots. I can kinda write stories about them as a duo forever, because you can always excuse them both getting hyped on a bad idea for their own reasons, and then you can always come up with a reason for them to disagree about it, and it’s always sweet to see them come together again, because they’re so full of themselves, but they are also both so damaged they desperately need each other.

Not only reinforcing the idea that their codependency was—or at least eventually became—mutual, but confirming that things returned to their status quo. Ford has a black & white mindset, the only way he knows how to be with Stan is a codependent way. They’re either separated and estranged or they’re sailing completely alone on a boat for the rest of their lives. Either rivals or best friends forever. There’s no middle ground for him.

#stanford pines#ford pines#stanley pines#stan pines#stan twins#gravity falls#gravity falls meta#stan twins meta

545 notes

·

View notes

Text

we see from Stanley's perspective that he thinks of himself as the "bad twin." so a lot of the fandom assumes that everyone in Stan and Ford's lives treated them like the "bad twin" and the "good twin" when they were younger. that that's just how things were. but I'm not so sure that's actually the case.

because when they were kids, Stan was also the stronger one. yes, Ford was also put in boxing with him, but Stan is the one who actually puts those lessons to use more often. I think it's just as possible that Ford saw himself and Stan as "the strong twin" and "the weak twin," and I think that double, opposite designation of a "better" twin is a) way more interesting and b) much more in line with the show than automatically making Ford the golden/favored child.

there's a few other analyses that I'm gonna link back to in this if I can find them later, but they're excellent takes on two things: Ford's complex around his own physical strength and his focus on developing it throughout his life, and Filbrick's lack of acknowledgement of Ford's intelligence for what it is until it was possible for that intelligence to make him money. (one thing I haven't seen mentioned a lot when it comes to Ford, Stan, and physical strength is their primary choice of weapons: Stan uses things that require strength of the user, such as bats, brass knuckles, and fists. Ford's weapons of choice are always guns of some sort, which require good aim, but not much in the way of inherent physical strength, unless it's like a massive unwieldy sci-fi space gun, and I think that says something about how they view their own strengths and weaknesses maybe.) I might also try to find that analysis on Ford being just as much of a menace as Stan.

anyway what I'm trying to get at here is that the "good twin, bad twin" angle isn't entirely accurate. it's the one that Stan ascribes to himself and his brother in the climax of the show, so it makes sense that's the one that sticks with fans. but the whole point of their childhood is that they only really had each other, because everyone else looked down on them. they weren't "the dumb twin and the smart twin", or "the behaved twin and the misbehaving twin", or "the strong twin and the weak twin," or "the freak twin and the not-a-genetic-freak twin."

they were "the weak twin and the stupid twin." "the freak twin and the misbehaving twin."

there's a reason Crampelter's taunts are highlighted in ATOTS. "hey, look, it's the loser twins." "you're a six-fingered freak, and you're just a dumber, sweatier version of him." they were both looked down on by others, in different ways.

but working on the Stan-O-War, things were different. "good thing you've got your smarts, Poindexter. I've got the other thing. what is it called? oh, right, punching!"

when it was just the two of them, they could be the smart twin and the strong twin. they each took the traits they were better at—the traits they were at least not bullied for, if not praised for—and each formed their sense of self around it. they saw themselves as two halves of a whole, each with one good quality that they could use to work together.

(@canadianno essay one have fun)

#gravity falls#stan pines#ford pines#stan twins#stanford pines#stanley pines#gravity falls analysis#I could have written this a lot better but I was just trying to get it Written

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

fiddleford's dialogue transcribed

here's the link!

same deal as the ford and bill posts. still inspired by this post.

fiddleford is obviously a character who is kind of all over the place because he was originally meant to be this comic relief villain who then became an Extremely Important Character with all sorts of stuff going on so this is an interesting one. as always, i ignore sounds characters make like laughter and grunting, which is notable because he does a lot of cackling that aaalmost sounds like words but. its usually laughter.

anyway, more notes under the cut

when fiddleford says “hey! hey!” in land before swine to get the group's attention, it does NOT sound like him at all. it just sounds like alex yelling hey. but it is definitely him. just a funny thing there

watching northwest mansion mystery again, it just occurred to me that when he's talking to dipper, that is the SECOND time he is telling a member of the pines family that the portal is about to bring something apocalyptic upon the world and is completely brushed off. LOL

i didnt realize how much he yells. realizing many characters in this show yell A LOT. the really intense screams are much more concentrated in early season one, which makes sense because thats before they knew what they were doing with him and were just being real goofy with him

in the society of the blind eye video, he juust vaguely sounds southern. in the atots and tlm excerpts, i think alex was leaning into his accent a liiittle more. i dont think thats intentional at all, but my watsonian analysis is i think fiddleford was suppressing his accent to be taken more seriously at work. i kind of dont understand the logistics of the blind eye video-- are all the tubes actual footage they took to mark what memory they took, and in fiddlefords case, its just this big video diary? if thats the case, then he was probably intending to use the video to prove his invention works and make some money off it i guess, so it could make sense he was trying to hide his accent there, vs when speaking with ford where he relaxes a little.

also listening to the "where are these ideas comin from?! who are you workin with?!" again, damn he sounds so pissed. it sounds like this has been coming to a head for a while, or that they fight about this often! but obviously ford says fiddleford doesnt know about bill. did fiddleford try to find out what all was going on there and then erase the memory of him doing so from fords mind? or did they just argue about this and ford would just completely shut it down? shit is juicy

"...in retrospect, it seems a bit contrived!" is still the best line in the whole show it kills me every time

also i didnt really think about this when writing fords stuff up, but i guess you could also argue that the memories from ford may not be 100% confirmed to be exactly the way fiddleford says it i guess?? because they show him reacting to fiddleford falling in the portal two ways, because memories can be unreliable, stan saying "i had a sophisticated new business strategy" while hes in his car, yadda yadda unreliable narrators, whatever. but im just gonna completely disregard that because 1, i think thats dumb, and 2, listen man ive only got so much material to work with here.

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

I recently watched your analysis of ATOTS, and since you’re not feeling great, may I offer you some extra facts that aren’t super important but might be mildly interesting/provide context in this difficult time?

If no, feel free to delete this! Just wanted to share cause they were mentioned in the video and I went “Oh! I know about this! Kind of!”

If yes:

1. The “Either 1800’s or Amish” woman using the Sham Total is actually wearing a very time accurate dress!

In the 70’s, 1910’s prairie fashion came into style: frills on leather jackets, leather boots, and “peasant” blouses and dresses, which is the style of dress the woman in the clip wears! I do not know why they called them “peasant” dresses but they sure did call them that!

You can actually see remnants of this in the 2010’s when the 70’s came into style (In general, fashion is always on a 30-year cycle, so whatever is in style now was probably in style 30, 60 or 90 years ago, as a rule of thumb)

2. Caryn’s storyboard design might be a nod to Jeanne Dixon, a psychic of the 60’s who famously claimed to have predicted the JFK assassination. It’s pretty subtle and if it is on purpose, they probably thought Jackie O was the deepest they could cut and changed Caryn’s design lol.

3. I have no doubt you checked this but a little hc I have: Stan and Ford would have been drafted for the war, being born June 15th.

But since there’s that slight confusion about June 15/16th I like to headcanon they were born around midnight, so Ford was born on the 15th, and Stanley was born between 15 minutes later on the 16th. Meaning that, by a huge stroke of luck, Stanley wouldn’t have been drafted.

That’s all I got — The analysis was a pure delight, thank you for all the work you put into your projects! <3

I saw your comment on the video and yes yes yes, thank you for the fashion analysis!

But also all of this is incredible historical context ty

70 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh my god!! Your analysis is so good and spot on. Just like the previous anon, I also don’t really have a favorite CP these days. I used to be an OffGun truther, but their last two series disappointed me, and I kind of drifted away from shipping. Now I just wait for good stories instead (Japanese BLs are my thing lately).

That said, I really want to ask you about some other GMMTV couples. Do you think anyone at GMMTV is actually dating? I don’t know why, but I’m 99% sure EarthMix are together—I'm even more certain about them than ZeeNuNew, who literally said they are. (I only watched Atots and I tried their latest series, but it didn’t click with me.)

Also, GMMTV couples definitely follow a regular fanservice routine. There’s a pattern there, I think. And I’m 100% sure JD(this is so clear also maybe joong had something with est not sure , maybe I just fall for the conspiracy theories) and PP are just good friends who do fs, but their fans would kill me in the spot if I said that out loud.

As for FirstKhao and AouBoom, they kind of give off that vibe where there’s something going on, but they’re not actually dating. I don’t follow FK much, but every time I see content about them, it just feels like First has a huge crush on Khao. Also, they’re one of the few CPs I’ve seen actually spend time together off-cam without posting it all on social media.

Don’t mind me if you found this ask weird but I’m just really glad to finally find someone who talks about BL CPs like they’re actual humans doing their jobs, and not some destined-to-be-together 24/7 soulmates sent from heaven.

Hello anon and thank you for the ask! It's not weird at all; I love reading about other people's takes and opinions on this wild genre we all tune in to 😊 keep 'em coming 🥰

And love that you're watching the JBLs. The Japanese BL industry is so unique and wonderful in its own right, my only complaint is that their shows are quite short 😅 But their cinema is just a masterclass in symbolism, pacing and cinematography. Love me a good JBL.

Anyway I'm just beating around the bush because I'm deciding on how to answer the main ask, but here we go:

Honestly my friend, I don't think I'm the best person to definitively say which BL branded pairs are actually dating in real life. Not because I'm acting all holier-than-thou (I speculate too just like the rest of us), but because my track record for predicting IRL couples is SHIT.

If you were an OffGun truther, oh my friend, I was a MewGulf AND a MaxTul truther 🤣🤣🤣 Look at how DISASTROUS the past five years has been for my fan career. 😄 And in such a specific way too, because waddayamean Mew and Tul ended up together? I would've accepted any other outside iceberg to sink my ships, but for them to collide headfirst into each other and set fire to the entire industry? I had to change soc med accounts twice! 🤣🤣🤣This is my honest track record friend, so take everything I say moving forward with a boatload of salt.

Not just for GMMTV, but of all BL cps I've encountered so far, I only 100% believe that one of them is an IRL couple, and that's DaouOffroad. Only (and only) because these two are so adamant in defending their relationship, and absolutely hate when fans speculate about them.

Speculation is a key ingredient of fanservice, as the more people talk about your IRL status, the more hype for shows and promotions a branded pair gets. Companies have learned to weaponize this by requiring their pairs to hang out outside of work in extremely public places, and get photographed by as many of their fans as possible (👀 side-eyes Mandee and MMY's Songkran activities).

Daou especially hates it when people speculate about him and Offroad, as he's said multiple times verbatim that they are together, and would like fans to take that as explanation enough to stop probing into their lovelife (a bad choice for their popularity honestly). He and Offroad have been known to ask fans to stop posting candid pictures and videos of them on social media, going so far as to threaten to sue a fan who posted a video of them holding hands and kissing when Daou attended his university's alumni concert (which wasn't open to the general public).

Candid (or staged-candid) photos and videos fuel speculation and fanservice. These sell very big bucks actually. To have those taken down, despite it directly translating to a loss in sales and popularity-- this action can only be driven by a force as strong as love. I'd tell Daou and Offroad to get out of the BL industry entirely if they wanted to protect their relationship, but they are artists first, and artists are paid for the harsh experience of entertaining others.

(I will not speculate on ZeeNunew with a ten-foot pole because I live in FEAR of their very large fandom with often angry X fans. If they say they're dating, then I believe them until proven otherwise).

That said, do I believe any of the GMMTV couples are dating? Sadly no, my friend, even EarthMix. I WANT to be proven wrong, and I would be more than happy to find out down the line that mr.-so-and-so are actually dating. But I believe none of them are dating IRL because of the premise DaouOffroad has already presented-- that an IRL couple would value their privacy more than the actual money and popularity that a speculated ship brings in. Granted, EarthMix might be THE closest to an IRL couple I can find in the current GMM roster, just because they post about their private activities very coyly ("coincidental" shots of the same landscape, or ig photos where one of them is partially hidden but still recognizable). But if there's one thing I've learned about the MewGulf fiasco of 2021, is that there's nothing coincidental or coy on social media. GMMTV, like any other conglomerate, has a marketing and social media team tasked to carefully curate their artists' posts, and these mystery photos and shy interview answers are tactics to still generate hype for an older couple, especially one that doesn't like to constantly engage with their fandom as much as other branded pairs. Moreover, GMMTV has outright admitted that they "encourage" their couples to spend time outside of work in order to build rapport, and often book joint hotel rooms and quarters for their branded pairs during filming in order to establish chemistry (as documented multiple times across their variety programs). Spending time outside of the company isn't proof of authentic relationships anymore, sadly.

(Again I would like to be proven wrong).

Don't think that I'm too jaded though, my friend. I do believe that though many BL actors are heterosexual (and hopefully allies of the cause), a great portion of the current BL actor roster are actually LGBTQ+ members. And I love that on this factoid, I am constantly being proven right (as with the case of Noeul and some KinnPorsche cast members coming out as bisexual).

That means, do I believe some GMM actors have a crush (even just a platonic, happy crush) on their partners? OH ABSOLUTELY, and that's where the fun is 😅 First does have a crush on Khao, he said it himself! He said he was in awe of Khao's acting, and once he got to know him, his personality. We've all been to grade school, isn't awe the first marker of a crush? 🤣

Aou and Boom have that fun, relaxed dynamic I first saw in Tay and New (before THEY got jilted by the industry they pioneered, woah boy isn't that a post for another day), and I think Aou totally admires his bestie Boom, and Boom looks up to Aou as a mentor. Est loves William's singing, and looks totally fond when William's on stage. William, has a thing for Est's random shows of strength. Pond and Phuwin like each others' faces 😅 (they said it themselves, dont @ me!), and finding someone handsome is peak crush behavior.

Isn't this fun? Even actors enjoy these light teasings during their fanmeets and stage shows. If only fandom speculation stays this light. Sadly we had to bring the bitchfighting and queerbaiting into this 🤣🤣🤣

All I'm saying, is that you're right my friend, shipping can be quite fun for both artists and their audience (I am currently finding BossNoeul fs HILARIOUS without the delulu stans ruining the fun), and who are we to deprive ourselves of the fun? But in terms ot the IRL couple status, I just think none of them pass my newly reinforced litmus test. PROVE ME WRONG GMM *laughs maniacally*

Also super sorry this got long! Hope it was worth its stupid length.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay, not (quite) anonymous any more, but still not (that) active yet. With all the recent discussion of episode 5 and the rooftop scene, I think I've yet to see analysis of 5 [4/4] 9:06-9:13, from when Pran says "We're not even friends" to when Pat says "That's right." Of course, we didn't know it on first viewing, but based on what we learn later from episode 12 [4/4] 12:58-13:54, what Pran says must have hurt. And we see it in Pat/Ohm's reaction. I'd love to see that deconstructed.

Hi @pandasmagorica! 😍 Sorry this reply is so late; I was struggling with my post about OS2 x BBS x ATOTS and also some work deadlines.

With regard to the Ep.5 rooftop, I must agree with you that Pran's comment "We're not even friends" must really have stung for Pat.

By this point he'd been totally swept away in the rush of his new-found feelings that he also knew were returned. But Pran, contrarian as ever, was vehemently denying the existence of closeness to his face. And to deny that they were even friends when they had actually been so close and affectionate behind the scenes before must have felt like a gut punch to Pat, who was laying himself so bare and vulnerable here.

For almost all of Ep.5 we watched as Pat sank deeper and deeper into the disorientating realization that he had somehow fallen in love with his supposed rival. And he must have been pushed so close to the brink of despair by the swell of these anguished, bottled emotions that he couldn't wait even a second longer than necessary to confess it all to Pran (which of course is quite in character for our open-hearted boy).

(above) Bad Buddy Ep.5 [4/4] 1.18

This was why he waited up for Pran down at the base of their block, drunk as he was, so as not to miss his return. And when he was prevented – by Wai's presence – from expressing all that was churning within him, of course he couldn't contain that pressure and it all erupted into a brawl.

But Pat on the rooftop is now showered and clearheaded, and once again focused on his task of confessing all to Pran.

(above) Bad Buddy Ep.5 [4/4] 7.45

Unfortunately, as before, Pran is unaware of Pat's true feelings and is expecting their usual jostling, competitive dynamic to be the framework of their exchange. And so Pran continues to toss barbs at Pat, thinking he'll find some way to lob them back as he'd always done before.

And in a sense he does, but Pat's energy is different now. For him it's not a game anymore and the usual teasing impishness that we saw so much of in preceding episodes (and at the start of Ep.5 too) is gone.

This scene is also a callback to (and a parallel with) Ep.3 [4/4] 6.09 – in the corridor there, Pran had been so moved by Pat's generosity and help with the bus‑stop that he decided to dial back on the rivalry and was wanting to take things to the next level.

(above) Bad Buddy Ep.3 [4/4] 6.51

This was the motivation behind his seemingly off-the-cuff "Have you eaten?" at Ep.3 [4/4] 7.20 – he was wanting to interact with Pat socially instead of as a competitor (see this write-up linked here for more analysis). Before this, the only other time we'd seen them at a meal together was at the wonton noodle stall (Ep.3 [1I4] 6.20), and it only happened by accident (and Pat soon turned it into a chopstick battle anyway) so I like to think Pran was wanting a romantic do-over in Ep.3 [4/4] by asking Pat out for a meal.

But there in the corridor Pat only seemed to want more of their usual relationship dynamic (more gameplay), and he signaled this with another of his bait-and-switch moves, lulling Pran with the return of his guitar and then saying "I just like to see your face… when you lose."

Here on the rooftop the tables have turned. In the corridor of Ep.3 [4/4] Pran was left resigned with Pat's unchanging focus on their rivalry (and yet maybe still relieved that they could continue their relationship, even if it was based on competition). But on the rooftop it's now Pat – all ready to bare his soul – who is thwarted and exasperated by Pran instead.

During the fight scene we already saw Pat getting annoyed at Pran (who was operating in their default mode of pretending to be bitter enemies). And he retaliated with a refusal to play along, turning snarky when Pran said "Why? Is it so hard to accept defeat?" at Ep.5 [4/4] 2.41. Pat's snide response "Defeated by that lousy song. Why would I feel anything?" landed like a slap too (though Pran couldn't have felt it, unlike Pat and us viewers who knew the truth behind his sarcasm). Because of course Pat had his heart torn to shreds when he finally understood that the song Just Friend? was really about Pran's unrequited love for him, and was now speaking to his feelings for Pran in return.

So on the rooftop Pat – perhaps annoyed at having to delay the confessing of his own truths – calls out the double-sidedness of Pran's comment and laces his response with more sarcasm and layers of unspoken meaning. His skewed, sardonic smile when he says "That's right" is a mix of sadness and derision, a colloid of contrasts ironically just like the relationship that they've always known – a forced mix of enmity and friendship, a combination of two opposites that will never truly meld.

If we're being generous, it's possible to read that Pran intended his "We're not even friends" to mean something like they're not allowed to be friends in the fullest sense of the word, in front of society and the world at large, even though they were always friends behind the scenes. But what Pat does is to take the literal meaning of this and flip it on its head.

They're both aware that their illicit friendship exists, but it's a friendship that dare not speak its name because of outside disapprobation. Pat's answer in the affirmative also snorts cynically, not just at Pran's surface denial, but also at their pitiless circumstances that don't allow them ever to be seen in front of others as anything besides bitter rivals.

And this is why he goes on to list why others might think they're not friends – in spite of the fact that (for all intents and purposes, except for how their relationship is presented to the world) – they actually are:

"How can we be friends when our parents despise one another?"

"How can we be friends if we live next door to each other yet can't even talk?"

"How can we be friends if we have to compete against one another in everything?"

But just like his sarcastic "That's right" and the cynicism of his mirthless smile, his words here are rhetorical, and are meant to highlight the opposite of what they seem to be saying – because his list is only made up of obstacles to friendship, but not reasons for enmity.

Their parents' mutual hostility, the ban on communicating with the boy next door, the enforced competition – these were constraints imposed on their friendship, but in themselves are no foundation or justification for any kind of animosity between them. And early on, little Pat and Pran found ways to get around the barriers and become firm friends in all but name, because there was never any justifiable reason for them not to be so.

Pat is calling Pran out here; he's telling Pran that he's just repeating what they'd been told since childhood, but the two of them, despite having drifted apart after Pran was sent away – they know better. And he's also calling for an end to the verbal gameplaying, and for them to face their truths.

Because after each rhetorical question is the silent, unspoken answer that BOTH know to be true:

"How can we be friends when our parents despise one another?" "But we ARE friends…"

"How can we be friends if we live next door to each other yet can't even talk?" "But we found a way around it…"

"How can we be friends if we have to compete against one another in everything?" "The competition was never a barrier to us ACTUALLY becoming friends…"

He's using rhetoric and sarcasm to illustrate that they weren't allowed to be friends and they've been conditioned not to call themselves that – but it doesn't change the truth about their friendship.

And I think Pran hears him loud and clear – despite what the world's been telling them all their lives, they are close and they have been friends, which is why there's a discernible softening on Pran's part.

I think Ohm did a fantastic job in Ep.5, heaving onto his shoulders the weighty stone that was also BBS's glowing heart, when it was Nanon doing all the heavy emotional lifting in the first four episodes. You can see what Pat is going through – but just in case you want further insight regarding his inner turmoil, BBS actually lets us in on a little more info.

Pat's audition as Riam in Ep.7 [4/4] 5.26 was also a play-by-play repetition of the Ep.5 rooftop scene, but Pat/Riam verbalizes his feelings a bit more directly, and adds further dimension to our understanding of Pat's motivations while on the rooftop.

(above) Bad Buddy Ep.7 [4/4] 5.26

Using Riam's voice, what he says in Ep.7 [4/4] cuts out all of his previous rhetoric, and instead speaks plainly of his weariness with the gameplay and of his willingness to give it up (repudiating his playful corridor self of Ep.3 [4/4]):

"I’m tired. Tired of pretending to hate you while your face has taken over my heart. Aren’t you tired too?... Let’s stop it. I don’t want to play this game anymore. I don’t want to lie to people anymore. You asked if I still wanted us to be friends. What if my answer is no? What do you say?"

Part of why Ep.5's rooftop scene hits so hard is not just because Pran walking away embodies the loss of a romantic story that could have been. It hits also because we see just how far battle-weary Pat has come, on a rollercoaster journey of grappling with emotions (over the course of just one episode) that Pran had taken years to integrate as part of his reality.

The loss is all the greater because we see how much it cost them to get to this point. For Pat it meant dismantling his worldview and lifelong sense of self as Pran's rival in every respect – and yet he was willing to cast it all aside, after recognizing the truth underlying his closeness to Pran.

As BBS is also an allegory for the lives of queer people, all the rumination around "friends who are not friends" here (also calling out to Pat's favorite among all of Pran's personally-scented tees) parallels how closeted LGBTQ+ relationships are often not allowed to speak their truth to wider society.

But while the allegorical message may speak to us intellectually, I think it gets drowned out by the molten magma at the searing core of this scene on the rooftop, which communicates directly – deafeningly – with the heart. All intellectual preoccupations aside, it's also just two young, would-be lovers stumbling through a conversation where so much is unknown and so much has yet to be said, trying to find the truth of their relationship in the maze of all the semantics – which is what many of us who have had to navigate young love must have experienced at some point.

Some of us get beyond the maze and fall into the truth behind the words straightaway. Others, like Pat and Pran, will have to take a little longer to get there. But as they ultimately demonstrate, it's always worth the journey when your erstwhile "friend" (or "enemy") turns out to be your soulmate instead. 💖

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

As semi-promised on Thursday night: here is a fuller explication of my thoughts after reading @zephrunsimperium's post about Ford and anger (which you should go check out their various Ford analysis pieces if you haven’t, they’re excellent and, unlike me, actually get to the point in a timely manner!)...thoughts which ultimately melded with some attempts at another essay I had semi-abandoned a few months ago, so hold on tight, friends, you’re in for quite the long ride with this one, should you choose to wade through it to the end, for this essay is more than 10,000 words long. Numbers in parentheses indicate endnotes, which can be found at the, well, end. Trigger warnings for extended discussions of multiple kinds of abuse portrayed/only thinly made into metaphors in the GF canon, and for discussion of mental health. For anyone feeling up to dealing with all that...read on below the cut.

To my way of thinking, one of the most essential things for understanding Ford lies in recognizing all the gaps between who he is, who he wants to be, and who he wants other people to think he is, and the intersection of anger, the performance of masculinity, and his long, long history of relational traumas is the fateful crossroads which those gaps emanate from. At the risk of sounding unduly like a pop psychologist, I also think his father is an important individual to consider in light of these issues.

Filbrick, as Stan tells us in ATOTS, was a strict man who had “the personality of a cinderblock.” Stan is not always a terribly reliable narrator, but he seems to lack the ability to lie to the flashback camera, and the first few flashbacks of the episode give us a glimpse at what the Pines family was like in the sixties which supports Stan’s assertion about his father. In those scenes, Filbrick is the only character we don’t see expressing strong emotion of some kind before the science fair, something that makes the ‘sound and fury’ of the scene where Stan is disowned, when it comes around, all that much more shocking. Until this point, Filbrick came about as close to physically resembling a cinderblock as his personality was said to; even when he expressed approval of Ford in the principal’s office, it was a relatively muted display, barely more emotive than his earlier “I’m not impressed” or his silent disappointment in the season one flashback when Stan recalls the summer Filbrick first sent him to boxing lessons. We learn after the science fair that he can, apparently, express anger very vividly, but “Lost Legends” further underlines how he is otherwise mostly emotionally inaccessible to his family; Stan (despite being far more aware of his emotions than he might like to admit that he is) cannot just talk to his father about how he feels, and once again, the only concrete emotion Filbrick shows on-screen is anger. Pictures near the end suggest possible mild experiences of a few other feelings, and the adult Ford, narrating many years after the fact and very probably after Filbrick’s death, speculates about what might have been going on in his head, but those feelings are never made explicit the way his anger is. We don’t know why Filbrick is this way (the closest thing to a hint we get is the information that he was a World War II veteran - there is, after all, a reason for the common portrayal of the Stan twins’ entire generation as one which was saddled with cruddy fathers in the aftermaths of World War II and Korea – but for all we know, Filbrick could have been like that before the War, too. What was his family life like, growing up? His financial condition? Could he just be someone who was born with a strong predisposition toward an emotional or personality disorder, regardless of whatever else happened in his life? We just don’t have enough information about him to say for sure), but it seems safe to speculate that he was this way pretty consistently: whatever else was going on with him, the only emotion he seems to have felt comfortable expressing was anger.

And this is the guy Ford and Stan had held up to them as their first, and quite possibly most influential, example of what being a man is.

I’d argue that – when they were children, at least – this was more of a problem for Stan than for Ford. Filbrick presumably saw them both as shamefully weak as children, but Ford, at least, had another route to the old man’s approval readily available to him. If Filbrick was at least grudgingly proud of Ford’s intelligence, then Ford could receive the measure of parental approval which Stan craved and could never get; we also see that Ford could apparently hold his own while sparring with Stan by the time they were teenagers, so it’s likely enough that he no longer had to worry about physical assault from his classmates by the time he was in high school, either. Though still isolated and insecure underneath it all because of his childhood experiences and probably in part due to his ongoing social isolation, Ford was able to find a path to a kind of self-esteem: he was both brilliant and quite capable of using his six fingers to break your nose if you had too much to say about them, and he knew it, and everyone else knew it, too. He also had his brother as a constant source of support. When Ford was made to look ridiculous by having a drink thrown in his face in public, Stan promptly threw a drink in his own face in order to look even more ridiculous. When Ford won competitions, which he seems to have started doing at an impressive rate very early in life, Stan seems to have been almost over-enthusiastic in his approval: he looks as delighted about Ford winning the science fair (at the time, before the meeting with the principal) as Ford himself does, if not even happier about it. Even his habit of copying off Ford’s papers in class could have served as a reinforcement for Ford’s ego: he not only could manage for himself, but he could even allow someone else to depend on him.

In this way, by the time everything went wrong, the teenaged Ford had probably already developed a degree of self-respect and self-sufficiency that Stan was still struggling to reliably maintain forty years later. Neither of them could ever be the kind of man Filbrick was, or of which they thought he would approve, they were both too emotionally vulnerable and expressive for that, but it’s probably noteworthy that Ford kept pictures of famous scientists (instead of family photographs) around him during his college and young adult years: because he could also do something Filbrick never could, he was able, to some degree, to carve out an idea of “how to be a man” on his own terms. If Filbrick’s approval was an immovable object in the path between Stan, Ford, and healthy expressions of adult masculinity, then where Stan flailed against it, Ford simply walked around it by choosing new conscious role models.

Tesla, Sagan, Einstein, and company were “great men,” successful (well, at least remembered posthumously) and respected, who were also given to Nerdy Enthusiasms. Said enthusiasm, an open delight in the marvels of the natural world, was therefore an emotion besides anger that Ford could express freely without compromising his view of himself, and it seems that he did so regularly. This appears to have worked well for him; we know very little about his college years – only that he worked very hard, that he made at least one close friend and (based on his usage of the plural ‘friends’ when discussing DD&MD) possibly even had a social group of sorts, and that he continued to indulge his creative side to a degree by playing DD&MD, which was as close as someone in his late teens and early twenties could probably get to continuing the kind of fantasy play he’d enjoyed as a child without sabotaging his probable adolescent desire to feel very grown up – but it seems they were productive and reasonably happy. Six years after them, a slice of his life comes into focus for us in the form of his journal. He was probably around thirty to thirty-three years old when it was written(1), give or take a year or two, and we find him several years into the circumstances he was in when he says, as a much older man, that he’d finally found somewhere to belong. He could be lying - Ford, unusually, even has the ability to lie to the flashback camera, or at least omit things - but we don't really have any reason to believe this; when the flashbacks turn to Stan making an abortive attempt at contact, Ford on the phone sounds cheery. His lack of paranoia and surprise about someone phoning him is also not the only evidence that, at this time, he may not even have been totally socially isolated in Gravity Falls – in the same years, he goes to the public library with some regularity, he declines to buy cookies from a zombie Boy Scout, he converses sometimes with the mailman, and he is on friendly enough terms with Dan Corduroy, even some years after Dan finished building Ford’s house, to know that Dan’s family had a holiday cabin and to ask to use it. Clearly nobody was too close to Ford even then, but his chosen path was going reasonably well for him; it's possible that Stan might have found him rather harder to replace at this point than he did later, after an unspecified time lapse, which may have lasted as long as a year,(2) during which Ford had gradually became a complete recluse as he became more and more consumed by his relationship with Bill Cipher. Before that time lapse, Ford the man seems like a logical enough place for Ford the boy to have ended up; after it…..

Well, after it is where we get back to the topics of anger and its intersection with various aspects of identity and self-concept.

A decent place to begin is with Fiddleford, and with why, exactly, Ford asked him to come to Gravity Falls. Ford tells us that he asked Fiddleford to come because he (Ford) did not have the technical know-how to complete the Portal. There is some evidence to support the veracity of this idea: Fiddleford is, after all, the man who later proves able to build astonishingly lifelike robot monsters whilst homeless (and thus, it seems safe to assume, without conventional sources of funds or supplies), and he is the one who sees the flaws in the Portal design. Indeed, he seems to start spotting them before he even has a chance to physically see them: Ford tells us that Fiddleford started suggesting revisions to the plans over the phone while still in California, in the same conversation where he agreed to come. In the third portion of the Journal, the sixtysomething Ford also mentions hearing about how a Parallel Earth Fiddleford was convinced to come back to the project, at which point the Parallel Portal was stabilized and became something that could be used the way Ford had intended to use it (as opposed to how Bill had intended to use it). The implication is that Ford not only didn’t understand how to complete the Portal, but that he also didn’t understand the plans even as far as he thought he understood them. Certainly the Fiddleford of the main timeline, who would have worked with him before, was instantly suspicious about the existence of a third collaborator once he saw how far Ford had gotten without him, which further supports the idea that Ford was more of a theoretician than a mechanic. This does, however, run somewhat against the grain of much of what we see Ford do on-screen. As a teenager of modest economic means, he was shown to be as comfortable working with his hands as with his pencil, and he was able to build something which acted enough like a perpetual motion device that he won a state-wide competition and drew the attention of an elite university. At university, he created the mind control tie – something which appears, both by its existence and by the glimpse we get of how it’s wired in “The Stanchurian Candidate,” to involve electronics more sophisticated than what Fiddleford was shown working with in roughly the same time period. I tend to run with the idea that the events of the episode “The Stanchurian Candidate” only happened in a particularly vivid nightmare of Stan’s, and therefore include the tie simply because it was in the Journal, but if one goes with official canon and accepts that “Stanchurian Candidate” happened, then Ford somehow, in a matter of hours, with no budget or supplies, invented a thousand-year lightbulb that also improves the complexion of the user in the same episode that shows us the wiring of the tie. In the eighties, he also seems to have developed his mind-encrypting machine as a private project, and in the Multiverse, he survived entirely on what he could steal or construct for thirty years, and it seems he had progressed a long way toward the development of the Quantum Destabilizer on his own before he stumbled into the ‘Better World’ dimension; Parallel Fiddleford really just sped the completion process up because he’d happened to discover a useful fuel source for presumably completely unrelated reasons years before Ford showed up. Clearly, Ford can more than hold his own as an engineer, and as one with a particular flair for doing impossible things with electricity and the laws of energy conservation; even Fiddleford trusted his gift in that area enough to, however reluctantly, briefly accept his claim that he had been working alone despite his serious doubts about the idea, and to allow Ford to bully him into silence about the Portal’s design flaws for weeks or possibly months before the confrontation at the diner. Why, then, did he suddenly become convinced, during that fateful July, that he could not finish the Portal without Fiddleford?

The answer may lay a few pages further back in the Journal. Not long before he calls Fiddleford, Ford makes notes on the plans for the Portal that Bill had showed him in a dream. One of these notes is “I MUST NOT LOSE MY NERVE!” Later, in a state of mind where he is increasingly paranoid and beginning to lose a degree of touch with reality, he reflects repeatedly about Fiddleford’s nerve in similar terms. There may well have been some level, deep down, on which Ford knew he was getting in over his head, and he was scared out of his mind by that realization. If this is true, then, on some level, he knew something was...off, with what was going on around him. He knew he needed help from someone he trusted and who was not Bill. And so he reached out to his college roommate for that help, and he did so in a way that allowed him to still plausibly deny just how much trouble he was in, both to himself and everyone else, and he didn’t only need that deniability because he was inviting a third party into the isolation of an increasingly abusive relationship and would need an excuse if Bill took exception to the idea of Ford relying on anyone or anything other than Bill. He also needed that plausible deniability to preserve his self-concept, because by this time, whatever he had or hadn’t been earlier, Ford Pines had become a deeply, deeply dishonest man.

One of the key moments for understanding this - and, in many ways, the character overall - occurs in “Dungeons, Dungeons, and More Dungeons.” There, Ford delivers the exasperated line, “if my hands were free, I’d break every part of your face!” If that line was taken totally out of context and shown to a casual viewer, the casual viewer would likely misidentify it as a line of Stan’s. Stan is, after all, the character with the hair-trigger temper and violent tendencies, right?

To an extent, yes. In “The Golf War,” Stan asks Soos if it would be “wrong” to punch a child (Pacifica) – probably more of an indirect threat in response to Pacifica’s insults toward the Pineses than a true question, but Stan’s moral code is sufficiently different from the standard issue that one can’t completely dismiss the possibility that he really wanted to, well, punch a child. And who can forget his antics in “The Land Before Swine” or “Scaryoke,” where he punches his way single-handed through monsters which had defeated the rest of the cast? Or in “Not What He Seems,” where he takes on multiple government agents in zero gravity while, for at least part of the time, he had his hands fastened behind his back? Or that glorious moment in the finale when he did, in fact, break every part of Bill Cipher’s glitched-out face? Stan is also the character who lost his temper to the extent that he lashed out at Ford physically in the middle of the save-the-world ritual, and Stan is the one who keeps his old boxing gloves around his bedroom, along with owning at least one set of brass knuckles. As an old man, he still seems to take pride in having learned to fight back against the world physically as a child, and he recommends that Dipper try knocking Robbie unconscious bare-handed when Dipper is challenged to a fight. And, of course, the man is a menace whenever he gets within a certain radius of the Stanmobile, the vehicle that can take out roadway railings, light poles, and theme park gates without showing a scratch. There’s no denying it: Stan is perhaps many other things, too, but he’s also a very physically aggressive kind of guy. If, therefore, someone in this series was going to threaten to break someone’s face, it seems obvious it would be Stan…but it wasn’t. It was his supposedly milder-mannered, “goody nerd-shoes,” brother who, on examination, actually behaves far more casually violently than Stan does throughout his sadly short time in the series. To demonstrate:

Ford sets foot in his house for the first time in thirty years and identifies the first person he sees as his brother. Later, writing in his reclaimed journal, Ford describes his own reaction thus: “instinct took over and I punched him right in the face. I feel kind of bad about that!”

In the very next episode - aside from his antics in the first scenes(3) and the already-mentioned description of what he’d like to do to Probabilitator after the wizard captures him - we also have Ford’s immediate reaction to the wizard’s materialization. Stan is, naturally, most clearly unnerved by an evil math wizard suddenly materializing in the TV room, but there’s a moment where he glances sideways at Ford after Ford pulls a gun; to me, at least, this glance made it seem like he found that behavior pretty disturbing as well. For the past several hours, after all, Ford had been playing board games. Most people do not bring concealed guns to game night with their nephews. Ford does.

Stan and Ford both have wanted posters that show up ‘on screen’ – Stan’s in his box of memorabilia in “Not What He Seems,” and Ford’s in Journal 3. Stan’s talks about “scams, frauds, and identity theft” - all potentially serious crimes that can ruin the lives of the people on the other ends of them, but ones which follow the general tendency (per the reading I did last March) of real-world con men to avoid violence in the commission of their crimes. Ford’s, on the other hand, refers to its subject as ‘armed and dangerous,’ and as someone with a bounty on his head. From the way Ford depicts his own appearance in it, it seems likely that particular version of the poster is at least ten to fifteen years old, but in “Lost Legends,” he is still instantly recognizable in the multiverse for his criminal shenanigans, even in the company of his near-identical twin. In his own words, “a number of dimensions consider me an outlaw to this day.” If one uses the dictionary definition of the term - and considering how much variety comes up just in the few examples Ford gives of worlds he’s visited, there’s no reason to assume he hasn’t visited a few Premodern Justice Dimensions - this means there could be multiple dimensions out there where the authorities took the time and trouble to formally declare that he had done something shocking enough to justify the revocation of all rights and protections he might have otherwise enjoyed under the law, thus allowing anyone to do anything they could physically manage to him with no fear of any negative repercussions except those he could personally inflict on them. He also refers to his own exploits as “swashbuckling” (a term which brings piracy to mind) and offhandedly mentions travels with “bandits” (a term which describes practitioners of behavior usually classified under the ‘organized crime’ umbrella due to the cooperative nature of the often violent or potentially violent crimes in question).

Much of this behavior, it’s true, can be attributed to a combination of trauma responses and, in the Multiverse, sheer necessity. He refers in the journal to talking “my way into and out of food and shelter,” and the “out of” comment underlines how, like Stan before him, he very abruptly went from having a relatively stable situation (at least in the material sense) to being homeless, which would be at least a serious shock to the system of almost anyone, including people in much better mental health than he was in at that time. Then there’s the more complicated non-material aspects of his previous situation. As an adult reader, it’s stomach-knotting to go through the 1980s portion of the journal, because if you look at the behaviors and dynamics and leave out the “incorporeal eldritch abomination” element, it only takes a very little extrapolation from the material for his ‘partnership’ with Bill becomes an uncomfortably realistic depiction of a domestic abuse situation. Considering that either of these major traumas of 1981-1982 could (and, if the fantastical elements are stripped out, regularly do) induce PTSD in nearly anyone, and considering how many more traumatic events he doubtless went through in the years following, it’s not implausible that the man would develop a tendency toward believing that the best defense is a good offense. However, there is also evidence that at least some of these tendencies predated Ford’s major traumas, and that – despite how he would very likely insist this was not the case - the trigger-happy adrenaline addict we meet in “A Tale of Two Stans” may not represent a total change in character from who he was before the Portal – or even before Bill. The evidence here is admittedly scarcer and more ambiguous, but to illustrate:

In Journal 3, Ford seems sincerely puzzled about why Fiddleford would show signs of trauma after the gremlobin incident. This incident involved Fiddleford being shown his worst fear (something which ended in tourists being removed from the Mystery Shack via stretcher in apparent catatonic states. Fiddleford was a man who probably had an anxiety disorder to begin with, who was just accepting the reality of the supernatural, and who was living, for at least several months, hours away from where his wife and young son were, something which seems to have troubled him at the best of times. It's remarkable he was functioning at all after the gremlobin incident). He was also hit with a bunch of venomous quills, and flown through the air by something which clearly had no good intentions for him in mind…and that was all before the solution to the situation ended up involving Ford crash-landing everyone through the roof of a barn, breaking Fiddleford’s arm in the process.