#armigerous

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

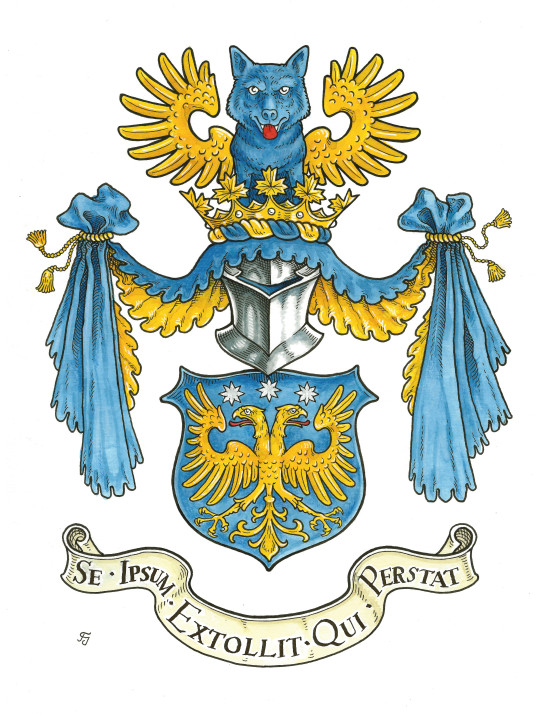

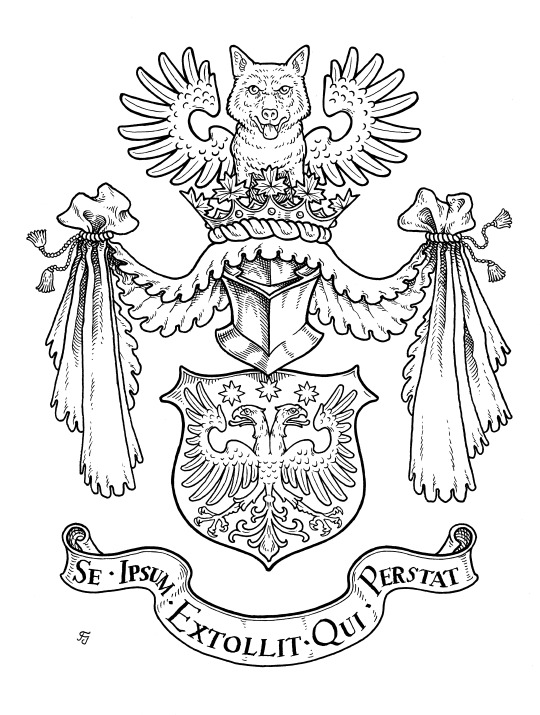

Emblazonment of my father’s armorial achievement by Fritz Jahn (fritzorino), gifted to him for his 64th birthday,

#Canadian heraldry#coat of arms#heraldry#crest#heraldic#Se Ipsum Extollit Qui Perstat#Armiger#armigerous#double headed eagle#winged wolf#Fritz Jahn#fritzorino#family arms#family history

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

'You are armigerous, Nobby.' Nobby nodded. 'But I got a special shampoo for it, sir.'

Terry Pratchett, Feet of Clay

#Terry Pratchett#Feet of Clay#Sam Vimes#Commander Vimes#Corporal Nobby Nobbs#Nobby Nobbs#Nobby#Nobbs

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nobility of Soul Society

So how exactly do the noble ranks in Soul Society work by comparison with more familiar European ranks? Let's start from the top.

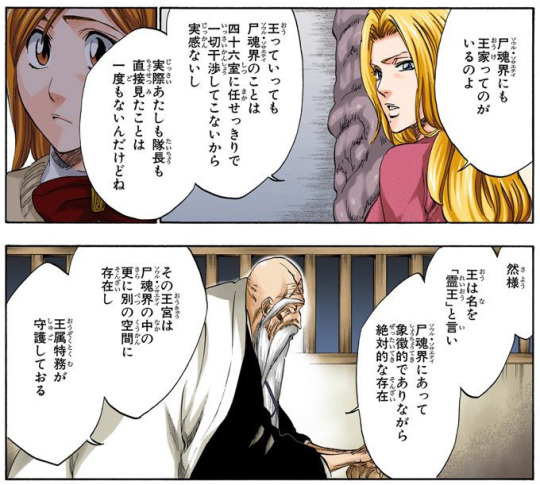

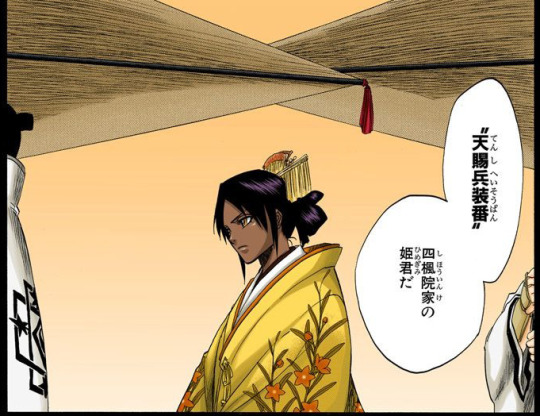

We're told in chapter 223 that there is a royal family. The first speech bubble is:

尸魂界にも王家つてのがいるのよ

The key component of this is 王家, Ōke, "royal family". So far so good, nothing to see here. Except we know this is purely propaganda, because the Soul King is a dismembered body with no direct living relatives, only his discarded parts and pieces absorbed into unrelated individuals. "The emperor has no clothes", quite literally in this case, and no power, and there is no royal family, just the Soul King himself. This is backed up by CFYOW, which never once mentions a royal family. Likewise, in WDKALY, we learn that the events of TYBW have been dubbed "The Great Soul King Protection War," with the royal family never being mentioned. This will become important later.

This is from chapter 159. The second speech bubble is:

四楓院家の姫君だ

The key component of this is 姫君, hime-gimi, "princess", but also more literally "daughter of a person of high rank (esp. eldest daughter)". However... this doesn't mean what you would think it means from a direct English translation.

It's instructive at this point to turn to this article, Modes of Address for Japanese nobility. If we search for hime-gimi, we get:

A title useful for armigers is –gimi, which means, literally, Lord [Lady] —. Again, through an odd twist of linguistic fate, the same kanji is now read –kun, and is the condescending form used by superiors in offices to their inferiors, and by upperclassmen to their lessers in academe. One hundred years ago, it would have been Yorimasa-gimi, a term of respect, but now it is Yorimasa-kun, less respectful and a bit condescending. Women would be addressed formally by their last name (with –dono or –sama as appropriate); armigerous women would properly be addressed by their first name with an appended –hime. The word alone may be used to address titled women; e.g., “Hime, are you ready for court?” It was commonly used for any aristocratic lady. Alternately, women of rank could be addressed by their given names to which is appended the title gozen, another difficult to translate term but one which essentially means “honorable [person]-in-front-[of me].” ) Actually, gozen can be used for both men and women, but only in specific situations. For example, a priest may be called “gozen-sama.” One important note; even when talking about someone who is not present — especially in a formal or polite setting — one should always use the honorifics. Leaving them off is a slight, and shows lack of consideration and near complete disregard for the individual in question.

You have here an explanation for quite a wide variety of things, although I'll return to those in a moment. First, I want to direct your attention to the terminology chart located at the bottom of the article:

We know from our earlier observation that the so-called royal family simply does not exist and that the Soul King is a puppet, so we may safely ignore the King, Queen, Crown Prince, Crown Princess, Territorial Prince, and Territorial Princess ranks. And so we are left with the Ducal ranks, which is the first place we see Hime-gimi. While it's used for lesser ranks too, as this is the highest place we see it, we can safely ascribe it to the Five Great Noble Clans (and later Four Great Noble Clans).

Yoruichi is not a "princess" in rank, or only one of the Shihōin Clan. Yoruichi is a Duke, and probably such rather than a Duchess because she is the first woman to hold the rank for her clan. She also already holds the rank as of this time. This would suggest she is already Clan Head as of this scene, even though she is not the Gundanchō (Unit Commander) of the Punishment Force yet (it's spoken of in the future tense), and presumably not Sōshireikan (Supreme Commander) of the Onmitsukidō.

The best description of Yoruichi's office would be Duke of Shihōin, however her actual title is not Kugyō, a particular real Japanese institution, but is led in with the quotations in the remark before: Tenshiheisōban (天賜兵装番). Thus, contra the last time I talked about this term and contra Viz itself, the title does not apply to the Shihōin—it applies solely to Yoruichi. She is the Tenshiheisōban. The Feng family member is referring to her specifically, as is Soifon in chapter 154. (This title, incidentally, seems not so different in framing than the full term for the Shogun, 征夷大将軍, Sei-i Taishōgun, "Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force Against the Barbarians".)

(For more about this, see Tenshiheisōban is the Title of Only the Head of House Shihōin.)

As discussed in the last link, why Viz persistently insists upon including an extra note in dialogue of "the Defender of the Realm", which is not present in the original Japanese, remains somewhat unclear. However, it would make more sense to not directly translate the term if it was Yoruichi's official title, and to instead provide an approximate meaning rather than a direct translation. This is Viz's take on it. What it actually means is a separate issue. (A question that arises as to what is heaven sent: the armaments, the guardian, or both? It would seem to be the former, but is more likely actually the latter...)

Anyway, if you believe in the chart absolutely, using hime-gimi to reference her is wrong as it should only be used to address her, but perhaps some obscure rules are at work here. It would be proper to address her as "Yoruichi-dono", much as Tessai does, or like how Rukia calls Kaien by "Kaien-dono". The article notes that -dono and -sama have gone up and down over time as to which is more prestigious relative to one another, but at any rate this readily shows why Soifon calls her "Yoruichi-sama".

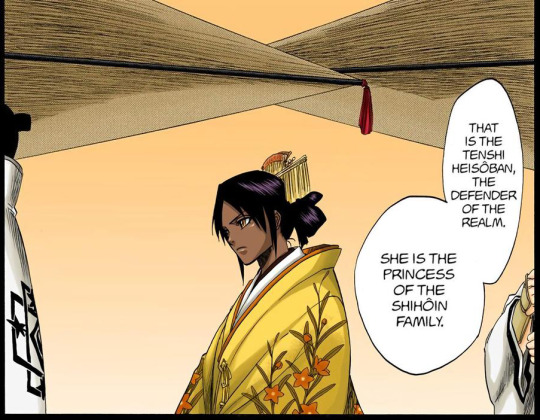

Speaking of that, in chapter 159, we get to see Soifon's original term of address: 軍団長閣下, gundanchō kakka, "your excellency the Unit Commander". This seems rather explicitly less related (though not inappropriate) to Yoruichi's rank in the nobility, but rather to her military rank. (I've noted before that the Feng are oddly obsessed with Yoruichi's status as Gundanchō rather than her more all-encompassing rank of Sōshireikan, as both the older Feng in the flashback uses it, as does Soifon upon fighting Yoruichi; they seemingly only care about the Punishment Force, not the Onmitsukidō as a whole.)

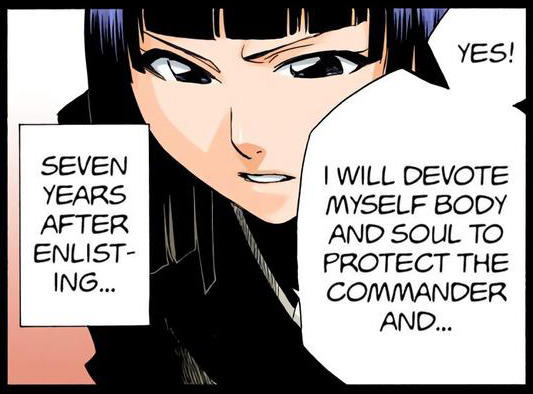

Yoruichi then notes that 閣下, "your excellency", is too formal, and directs Soifon to call her 夜一さん, "Yoruichi-san", instead. You can tell because these are in quotes. So Viz's use of "commander" is wrong and Yoruichi is actually somewhat more formal here than Viz portrays her as. (This suggests that Kisuke habitually calling her Yoruichi-san is either exactly what she wants, or he's teasing her by using a more formal register from back when more decorum was necessary.)

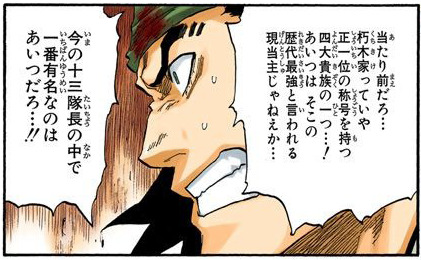

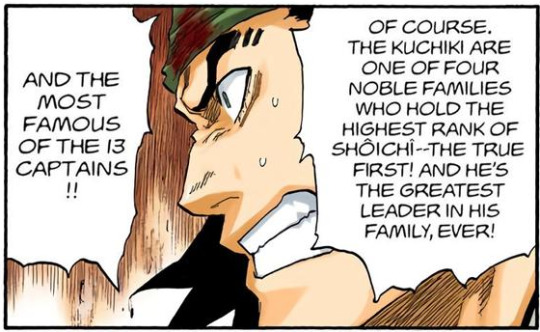

You might be wondering how we can assert that the Four Great Noble Clans are indeed the highest ranking nobility. Well, we can see in chapter 114 that Ganju describes Byakuya as:

当たり前だろ…朽木家つていや正��位称号を持つ四大貴族��一つ…!

Viz's translation is fundamentally correct, although in leaving Shōichī initially untranslated and then clarifying what it means, we can see that Viz doesn't care to immediately translate titles (affirming earlier remarks on the Tenshiheisōban).

This also means that the Bleach Wiki is yet again wrong in ascribing the title of Shōichī purely to the Kuchiki Clan—it applies to all the Four Great Noble Clans equally. (We learn in CFYOW that the Tsunayashiro seem to have a primus inter pares status among them, but this is seemingly sort of informal.)

In short, we can say that the Four Great Noble Clans represent Dukes, with a distinct status which may push them more toward pseudo-royalty (in the sense that Duchies or Dukedoms can be independent countries). Other nobles represent Marquess, Counts, Viscounts, and Barons, with the possibility of something like the German ranks of Ritter and Edler considering we know Shinigami can be promoted into the nobility.

The head of the Kasumiōji Clan, which is anime-only but is described as being just below the Four Great Noble Clans in prestige, would thus be a Marchioness (female Marquess). The head of the Kyōraku Clan would presumably be a Count. The head of the Ukitake Clan, which is described as lower nobility in Jūshirō's datasheet, would presumably be a Viscount or Baron.

This is from chapter -105. Byakuya's third speech bubble is:

そもそも朽木家次期当主たる私に遊びなどなどだ!

The key component of this is 当主, tōshu, "family/clan head". Theoretically Byakuya could be described as 朽木家の当主, Kuchiki-ke no tōshu, "clan head of the Kuchiki Clan", but I've been informed that this isn't properly a title that would be used to describe him.

Presumably, much like Yoruichi has a particular title in Tenshiheisōban, Byakuya would also have a particular title. (As would have Tokinada, and presumably Kaien.) Why we only appear to learn Yoruichi's in particular is a mystery.

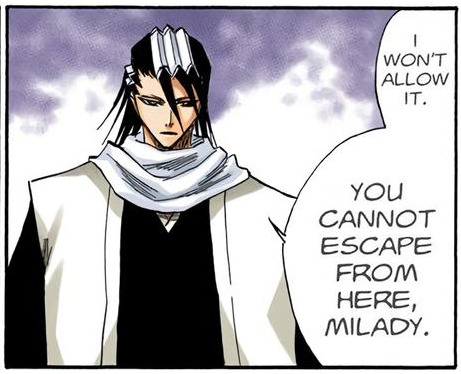

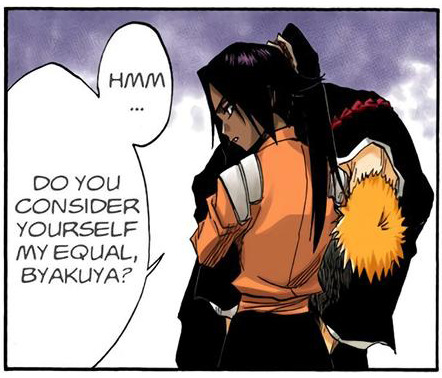

It's worth noting that this "milady" here in chapter 118 is completely wrong. Byakuya says in the lower speech bubble:

兄はここから逃げることはできぬ

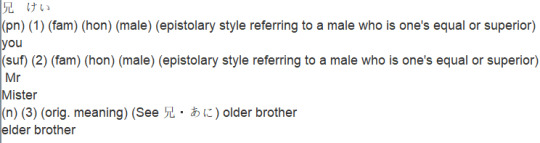

He uses 兄, ani, "older brother":

I have to imagine that this is an insult directed at Yoruichi since this is a purely masculine term. He's presumably making fun of her voice in cat form (which she used to torment him) and/or her use of a nominally masculine personal pronoun in washi.

While Yoruichi's reply seems to directly refute the implication of equality between them, I think Viz does a bad job here. Yoruichi pauses first, and her remarks are hard to get a good translation of. I think it might be some kind of Japanese idiom. I think the vibe of what she's saying is best rendered in English as something like, "Looks like little Byakuya has gotten too big for his britches," or perhaps, "Looks like little Byakuya has learned how to play with the big boys." In any event, she's definitely making fun of him right back.

There are probably some things I've missed, but I think the bolded sections provide a good overview of the relative rankings of the nobles in European terms.

CFYOW makes it fairly clear that the power of the Four Great Noble Clans was reduced by the expulsion of the Shiba Clan, to the benefit of Central 46, and Central 46 seems to be largely controlled by the relatively lesser nobility as a means of imposing restraints upon the Four Great Noble Clans.

I don't have an exact point of comparison, but by analogy you might say they sort of resemble the Minamoto, Taira, Fujiwara, and Tachibana Clans during the Heian Period, collectively sort of "substituting" for the (in Soul Society's case effectively vacant) imperial throne. (This is essentially what Aizen alludes to upon leaving Soul Society.) The Soul King is basically a fictional monarch in whose name they operate, but they have actually ruled all along. However their power is in turn checked by Central 46, which the ordinary nobles use to actually govern day-to-day affairs.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLAN CARRUTHERS: Irving of Bonshaw and Carruthers, the sharing of a historical path.

We know that of the 17 clans mentioned in the Act of Parliament of 1587 regarding the suppression of Unruly Clans, that not all currently have a Chief ie they remain armigerous. Of these, those that have official clan status are Elliot, Carruthers, Graham, Irving, Jardine, Johnstone, Moffat and Scott. Some others however, are pursuing official status through the Lord Lyon and Clan Bell springs…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Clan MacFarlane (Scottish Gaelic: Clann Phàrlain [ˈkʰl̪ˠãũn̪ˠ ˈfaːrˠl̪ˠɛn]) is a Highland Scottish clan. Descended from the medieval Earls of Lennox, the MacFarlanes occupied the land forming the western shore of Loch Lomond from Tarbet up-wards. From Loch Sloy, a small sheet of water near the foot of Ben Vorlich, they took their war cry of Loch Slòigh.

The clan was noted for the night time cattle raiding of neighbouring clan lands, (particularly those of Clan Colquhoun), and as such a full moon became known locally as "MacFarlane's Lantern". The ancestral lands of the clan were held by the chiefs until they were sold off for debts, in 1767. Since 1866 the chiefship has been dormant, no one having claimed or obtained rematriculation of the Chief Arms making Clan MacFarlane a supposed Armigerous clan.[2]

https://www.tripadvisor.com/RestaurantsNear-g42130-d7623065-Fairlane_Town_Center-Dearborn_Michigan.html

Stella Ristorante - Fairlane Subdivision - GrabFood

Grabhttps://food.grab.com › Home › Restaurant

Looking for food delivery from Stella Ristorante - Fairlane Subdivision? Check their favourite menu, prices, promos, and order now with GrabFood.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I have no memory of references to Australia (pertaining to Watson at least), but I think I have an explanation for the idea that he lived in either Australia or Scotland as a child.

Scotland seems to come from the fact that he was part of the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers as Assistant Surgeon (STUD) and the Northumberland region of England borders Scotland. “Watson” is also a Scottish surname with the Watson Clan being an armigerous clan.

Additionally, Watson says in STUD that he has “neither kith nor kin in England.” We know that his father and brother are dead, but having not even distant family in England could hint that his extended family lives somewhere else. One possible answer being Scotland. There’s also it being a way to explain why Mary seems to call him James in TWIS. Some attribute his middle name to being “Hamish” since we only learn his middle initial and Hamish is the Scottish equivalent of James.

If I remember properly, the concept of Australia may also come from the “neither kith nor kin” bit as well as the fact that that he claims experience with women “over many nations and three separate continents.” (SIGN) We know two of the continents are Europe and Asia because of time spent in India and Afghanistan, but the third one is never explicitly mentioned. Thus there is possibility of the third continent being living in Australia as a child.

While I was reading some facts about Watson (I remember him being described as blond at some point and wanted to check that but I think that was a dream?? Am I the only one??) I came across this piece of information where it says that he lived in Australia as a child??? I can't seem to be able to find the source in the canon and it's the first time I hear about that (I thought he actually lived in Scotland as a child, was that also a dream??)

#Holmes posting#I’m certain I’ve read both origins in fanfic honestly#I’m quite partial to Scotland personally#but I also have always assumed that his third continent was Africa#quite the ramble of me

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

+ @armigerous

« ☀️ » : he looked upon the other with a bottom lip jutted out, hands on hips. this man was in all black! “hey! why are you wearing such negative clothing? you look as if you are embodying an evil spirit! you should be wearing much brighter clothes! come, i will take you to find something more suited for the spirit of this city!” he grabbed the stranger’s wrist, taking a few steps before stopping in his spot. he glanced over his shoulder and canted his head, “um, do you know where we can find garments?” he’s brand new here, what is he doing.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

⍟ ✹

⍟ any games on their phone? what kind? how often do they play?

Hinami doesn’t have a whole lot of games--in fact, she’s very new to having a phone in the first place. But she does love word games, things like scrabble and trivia games. It’s a nice little brain exercise! other than that, she might try some puzzle games, like bejeweled or something similar. She probably doesn’t play very often though, too busy getting distracted by a good book.

✹ five - ten songs on their iPod/phone?

Years ago, it probably would have been cheerful, upbeat songs, stuff an optimistic kid would listen to. But these days, it’s more things like Little Talks and Slow and Steady, both by Of Monsters and Men, Smokestacks by Layla, Hero by Ruelle, and probably some Lauren Aquillina sprinkled in.

#;;answered#[ thanks for sending!! ]#[ the last one required a lot of thought because i was like what would hinami even listen to?? ? ]#armigerous

1 note

·

View note

Text

#canadian heraldry#coat of arms#crest#double headed eagle#family history#heraldic#heraldry#se ipsum extollit qui perstat#armiger#armigerous#heraldic standard#heraldic badge#livery badge#heraldic art#brazeau

1 note

·

View note

Text

@armigerous

her intention had been to spend some time exploring the city, getting her bearings, making new connections and establishing herself in general. her plan had never, at any point, included stumbling across what seemed to be a small, lost, and very stray cat.

she knew better than to try to approach the cat quickly, but her gentle nature still had her unable to walk away and leave it alone. gently moving her skirts to the side, she looked from side to side, eyes settling on the first passerby who might be able to offer assistance -- or at least insight.

“--Pardon me, ser... Is this cat yours?”

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

On prior reserve, here is Noctis Lucis Caelum! Application is /app.

Luckily for you, it seems you won’t have problems makingfriends here! I think there are some people that would be glad to see you…

You’ll be housed in Hummingbird Hotel Room #207! Enjoy your stay!

♏ virgo

0 notes

Text

The regency era class system

Do not miss the opportunity to vote for the prompts for the event, and afterwards you can indulge in this information about the regency era class system.

Cottagers and laborers ~ Cottagers were a step below husbandmen, in that they had to work for others for wages. Lowest order of the working castes; perhaps vagabonds, drifters, criminals or other outcasts would be lower.

Husbandman (or other tradesmen) ~ A tradesman or farmer who either rented a home or owned very little land was a husbandman. In ancient feudal times, this person likely would have been a serf, and paid a large portion of his work or produce to the land-holding lord.

Yeoman ~ The yeoman class generally included small farmers who held a reasonable amount of land and were able to protect themselves from neighbouring lords et cetera. They played a military role as longbowmen. Sometimes merchant citizens are placed between yeoman and gentry in early modern social hierarchy.

Gentry/gentleman ~ The gentry by definition held enough assets to live on rents without working, and so could be well educated. If they worked it was in law, as priests, in politics, or in other educated pursuits without manual labour. The term Esquire was used for landowners who were not knighted. Many gentry families were armigerous and of ancient lineage possessing great wealth and large estates.

Knight ~ By the seventeenth century a knight was a senior member of the gentry, and the military role would be one of sheriff of a county, or organising a larger body of military forces, or in civil service exercising judicial authority. He was a large land owner, and his younger sons would often be lawyers, priests, or officials of some sort.

Baronet (hereditary, non peer) ~ A baronet held a hereditary style of knighthood, giving the highest rank below a peerage.

Peer (Noble/Archbishop) ~ The peers were generally large land holders, living solely off assets, sat in the House of Lords and either held court or played a role in court depending upon the time frame referenced, such as: Duke/Duchess; Marquess/Marchioness; Earl/Countess; Viscount/Viscountess; Baron/Baroness

Royal ~ A member of the royal family, a prince, a close relative of the queen or king.

Reference

#YOIregencyweek#YOI#yuri!!! on ice#yuri on ice#yuuri katsuki#victor nikiforov#yuri plisetsky#victuuri#yoiregencyweek#fandom event#yoi

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think you've written about this before, but where exactly are the landed gentry in terms of the aristocracy? Are they petty lords, or slightly higher/lower? Or are they separate from the aristocracy, and if so, what is the distinction? This is a source of constant confusion for me when studying British history.

I wrote about this here.

The gentry were a liminal class, existing at the very boundary of the aristocracy and the “commonalty,” and sharing both cultural and material characteristics of both.

Like the aristocracy, the gentry were defined by landed wealth; they didn’t work for a living (which would make them “in trade”), but lived off of rental income from their estates, which made them “gently born” and thus “gentlemen.” (This also meant sharing the aristocracy’s cultural values and practices.) In no small part because their economic basis came from inherited wealth, they shared the aristocracy’s obsession with lines of descent, arranged marriages with people from the “right families,” and of course, with coats of arms. One of the few remaining perks of being ex-noble was that you got to keep your coat of arms, and were thus from an “armigerous” family.

Like the commonalty, the gentry did not have peerages or knighthoods, because possessing those lifted you out of the gentry and into the nobility. In part because estate management isn’t cheap, the gentry would from time-to-time make marriage alliances with cash-rich merchant families looking for social advancement, so that the boundaries between the two classes could be somewhat porous and ambiguous. They occupied a similar position in the political system as well: if urban seats in the House of Commons were over-represented by elite merchants, guildmasters, and movers and shakers in local government, rural seats in the House of Commons were dominated by the gentry.

I hope that helps.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Euron: The Deconstruction of the Romantic Pirate Captain

Portrait courtesy of Mike Hallstein.

Warning: Spoilers for The Winds of Winter

Pirate fiction is a popular sub-genre with a rich history in both literature and film from Treasure Island to Pirates of the Caribbean. As David Cordingly pointed out in Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates, pirate fiction’s popularity can be given to these stories often taking place in far off places with many of the readers coming from the colder Northern hemisphere, and the bulk of these pirate stories taking place in the tropical Caribbean during the Golden Age of Piracy (1650-1730). It is also the adventure providing a form of escapism with many readers and viewers often living monotonous lives. As a result, pirates have been embedded in public consciousness from real-life pirates like Blackbeard to the fictional Long John Silver. Of course, as we’ll later get into, these fun images often contrast with real-life pirates.

In A Song of Ice and Fire, Martin creates an entire culture of pirates known to themselves as the Ironborn though they are less the pirates of the Caribbean and more pseudo-Vikings. Piracy is enshrined in the Old Way, which has the Ironborn “pay the iron price,” or obtain plunder (which can even include people) by taking them at the point of an axe or sword. Many Ironborn have made names for themselves through daring raids, and it is through these exploits that they raise their standing in society, both in material wealth and reputation. However, there is one such Ironborn who stands out.

"Some men look larger at a distance," Asha warned. "Walk amongst the cookfires if you dare, and listen. They are not telling tales of your strength, nor of my famous beauty. They talk only of the Crow's Eye; the far places he has seen, the women he has raped and the men he's killed, the cities he has sacked, the way he burnt Lord Tywin's fleet at Lannisport . . ."

-A Feast for Crows, The Iron Captain

Euron “Crow’s Eye” Greyjoy is introduced in A Feast for Crows right after the death of his brother Balon who had exiled him. In a family of pirates and reavers, he is the black sheep of the family, the one who’s hated by everyone else. He manages to stand out from his family and all the other Ironborn through both his cunning and his sadistic cruelty as well as by boldly sailing places where no Ironborn has gone before like Asshai and (dubiously) Valyria. He is the Ironborn closest to a romantic pirate in appearance (which is intentional).

Euron’s character, from sailing to far-off places and his treasure to his charisma and even his eye patch, makes it clear that Martin borrowed from other pirates in fiction.

Let’s start with the titular character in Captain Blood: His Odyssey, who is not a Romantic Pirate Captain™, he is the Romantic Pirate Captain™. The book was adapted into the 1935 film seen by a young George R.R. Martin with Blood portrayed by the ever-handsome, charming actor who was typecast as the dashing swashbuckler, Errol Flynn. The film’s final duel between Blood and Levasseur (portrayed by Basil Rathbone) is ranked as one of the top sword fights on-screen, with Martin himself ranking it alongside the duel between Inigo Montoya and the Man in Black in The Princess Bride.

A common trope in pirate fiction (though less so in real-life in the Golden Age of Piracy) is the pirate captain being an aristocrat or an educated man of some standing in society who is forced to become a pirate as a result of unfortunate circumstances. Peter Blood is a sharp-witted, handsome Irish doctor and veteran who is arrested for treason for attending to a wounded rebel during the Monmouth Rebellion. Blood is later sold as a slave and transported to Barbados to serve under the brutal master, Colonel Bishop, and manages to form a relationship with Bishop’s niece, Arabella. Subsequently, he is forced to become a pirate after the Spanish attack on Barbados, leading a crew of his fellow convict-slaves to freedom, and becoming one of the most feared and well-known pirates in the Caribbean. However, he manages to adhere to his own personal code and maintain some semblance of honor as a pirate while the legitimate authority figures in this story like Deputy-Governor Bishop, French commander Baron de Rivarol and Admiral Don Miguel de Espinoza as well as King James II (unseen) tend to be worse than the actual pirates. He preys on only Spanish ships and settlements (enemies of Great Britain who are treated as stock villains in the story) never on English or Dutch ones, operating more as a privateer than a pirate. He also chivalrously rescues women from other pirates and Spanish soldiers.

I have said already that he was a papist only when it suited him.

-Captain Blood, Chapter XVI: The Trap

No godless man may sit the Seastone Chair."

-A Feast for Crows, The Prophet

Peter and Euron both can claim descent from island nations (Ireland and Iron Isles) with a history of nationalist sentiment against domination by a larger neighbor (England/Great Britain and mainland Westeros under the Iron Throne). Euron is sharp-witted and “the most comely of Lord Quellon's sons,” coming from the most powerful noble house on the Iron Islands, and is forced to leave after being condemned and exiled by his brother Balon. Euron then pursues a life of piracy, and earns the moniker of “as black a pirate as ever raised a sail,” one of the most feared pirates in the known world. In their respective stories, Euron and Peter demonstrate themselves to be brilliant, talented commanders, always managing to defeat their foes and win battles with their wits, with examples being Blood’s gambit in managing to escape past Espinosa in the raid on Maracaibo and Euron’s strategy in the taking of the Shield Islands. They are also known for their boldness and daring among their fellows.

What but ruin and disaster could be the end of this grotesque pretension? How could it be hoped that England would ever swallow such a Perkin? And it was on his [James, 1st Duke of Monmouth] behalf, to uphold his fantastic claim, that these West Country clods, led by a few armigerous Whigs, had been seduced into rebellion!

“Quo, quo, scelesti, ruitis?” [Latin for “Where, where are you rushing to, wicked ones?”]

-Captain Blood: His Odyssey, Chapter I: The Messenger

“I shall give you Lannisport. Highgarden. The Arbor. Oldtown. The riverlands and the Reach, the kingswood and the rainwood, Dorne and the marches, the Mountains of the Moon and the Vale of Arryn, Tarth and the Stepstones. I say we take it all! I say, we take Westeros."

- A Feast for Crows, The Drowned Man

Of course, while Blood saw the Monmouth Rebellion as madness with his only involvement being healing a wounded rebel, Euron (described as madder than Balon) actually fought in the Greyjoy Rebellion (where Balon like James, 1st Duke of Monmouth, unsuccessfully tried to crown himself), and hatched the plan to burn the Lannister fleet at port. Blood is an innocent man unjustly condemned for following his Hippocratic Oath while Euron is a guilty man condemned for raping and impregnating his brother’s salt wife. Euron's crew is made up of slaves like Blood’s, but unlike Blood, he was never a slave himself whose slave crewmen joined him willingly, but a slave master who bought or captured them, and then compelled them to serve in his crew. Captain Blood returns after being pardoned (after the king who convicted him, James II, is overthrown) for saving Jamaica from a French assault, and chosen to be its governor, replacing his nemesis, Colonel Bishop, who ironically, was removed for abandoning his post in search of Blood. Euron likewise returns to the Iron Islands after arranging Balon’s death, and takes his post as King of the Iron Islands and Lord of Pyke, at first through intimidation, violence and bribes and later through a kingsmoot. Although, I would argue that like Colonel Bishop, Balon was an unsympathetic, incompetent ruler with an ultimately doomed invasion of the North and uprisings to go with Bishop’s doomed pursuit of Blood.

Blood looks out for his countrymen, and went to great lengths to avoid the sacrificing of his own men while Greyjoy only looks out for himself, even sacrificing and murdering his fellow Ironborn for his own ends. Peter rescues women from would-be rapists and kidnappers while Euron kidnaps and rapes them.

If he resisted so long, it was, I think, the thought of Arabella Bishop that restrained him. That they should be destined never to meet again did not weigh at first, or, indeed, ever. He conceived the scorn with which she would come to hear of his having turned pirate, and the scorn, though as yet no more than imagined, hurt him as if it were already a reality. And even when he conquered this, still the thought of her was ever present. He compromised with the conscience that her memory kept so disconcertingly active. He vowed that the thought of her should continue ever before him to help him keep his hands as clean as a man might in this desperate trade upon which he was embarking. And so, although he might entertain no delusive hope of ever winning her for his own, of ever even seeing her again, yet the memory of her was to abide in his soul as a bitter-sweet, purifying influence. The love that is never to be realized will often remain a man's guiding ideal. The resolve being taken, he went actively to work. Ogeron, most accommodating of governors, advanced him money for the proper equipment of his ship the Cinco Llagas, which he renamed the Arabella. This after some little hesitation, fearful of thus setting his heart upon his sleeve.

-Captain Blood: His Odyssey, Chapter XIII: Tortuga

"Who knows more of gods than I? Horse gods and fire gods, gods made of gold with gemstone eyes, gods carved of cedar wood, gods chiseled into mountains, gods of empty air . . . I know them all. I have seen their peoples garland them with flowers, and shed the blood of goats and bulls and children in their names. And I have heard the prayers, in half a hundred tongues. Cure my withered leg, make the maiden love me, grant me a healthy son. Save me, succor me, make me wealthy . . . protect me! Protect me from mine enemies, protect me from the darkness, protect me from the crabs inside my belly, from the horselords, from the slavers, from the sellswords at my door. Protect me from the Silence." He laughed.

-A Feast for Crows, The Iron Captain

Peter is loyal to one woman, Arabella, never finding companionship with another, and even rescues her from Don Miguel. Euron, by contrast, never had a single romantic relationship, just taking the daughter of the Lord of Oakenshield as his mistress, and later cutting her tongue out, and having her chained to his ship’s prow. Peter named his ship for Arabella, whose name means “yielding to prayer.” As well as reflecting his love for a certain woman, it represented his personal commitment to keeping to some semblance of honor and morality. Euron, in direct contrast, named his ship Silence, as a way of mocking his victims’ prayers of protection that are answered with only silence from both the gods and with death. The ship itself tellingly has a black iron likeness of a beautiful woman without a mouth.

Peter is shown to be merciful as he spared his enemies like Colonel Bishop and Don Miguel, as opposed to Euron’s mercilessness shown by having Blacktyde cut into seven pieces and Lord Hewett killed after capturing him. Peter is a noble gentleman and honorable rogue while Euron is an ignoble, black-hearted scoundrel. I would argue that as a character, Peter Blood is closer to Jon Snow than he is to Euron Greyjoy, or if you’re going for characters on the Iron Isles, he is closer to Lord Rodrik “the Reader” Harlaw with a shared scholarly disposition, and Harlaw’s attitude towards the Greyjoy rebellions being virtually the same as Blood’s towards the Monmouth Rebellion.

GRRM likely also had at least one other pirate in fiction in mind when writing Euron.

Long John Silver is the prototypical pirate from Treasure Island where many pirate tropes in pop culture get their inspiration from, and in Long John’s case, he has the talking parrot and the missing leg. He is the ship’s cook who turns out to be the pirate captain organizing a mutiny on the Hispaniola.

intelligent and smiling. Indeed, he seemed in the most cheerful spirits, whistling as he moved about among the tables, with a merry word or a slap on the shoulder for the more favoured of his guests.

Now, to tell you the truth, from the very first mention of Long John in Squire Trelawney's letter I had taken a fear in my mind that he might prove to be the very one-legged sailor whom I had watched for so long at the old Benbow. But one look at the man before me was enough. I had seen the captain, and Black Dog, and the blind man, Pew, and I thought I knew what a buccaneer was like — a very different creature, according to me, from this clean and pleasant-tempered landlord.

-Treasure Island, VIII: At the Sign of the Spy-glass

Euron had seduced them with his glib tongue and smiling eye

-A Feast for Crows, The Reaver

Euron and Long John both manage to stand out from their fellow pirates in a number of ways. What people often miss in Treasure Island is that Long John being a pirate captain is a plot twist. Jim doesn’t suspect Silver of being a pirate upon meeting him given while the first pirates we met in the book clearly gave the impression that they’re pirates though their heavy drinking, cursing and violent, threatening behavior, Silver by contrast is polite, well-mannered, courteous, warm and charming. He is usually sober and self-controlled, and greets you with a warm smile on his face. Likewise, the Ironborn reavers tend to display the same rough characteristics as the pirates in Stevenson’s book while Euron by contrast is charming and well-spoken, and we usually see him with a smile on his face. Long John also stands out through his intelligence which is shown in the way he manages his money well rather than spending it all away like other pirates, thinking about long-term planning, and coming up with a plan to find Flint’s treasure by deceiving Squire Trelawney into recruiting his men as crew members on the Hispaniola. Euron is shown to be intelligent and cunning as well when he takes the Shield Islands by not following the coastline and sailing out to sea to avoid being seen, and marrying Asha off to Erik Ironmaker, effectively removing her as a threat. Both men win their leadership positions through their charisma, force of personality, intelligence and lofty promises with taking Flint’s treasure in Long John’s case and all of Westeros in Euron’s case. Of course, Euron’s plan like Long John’s will likely not end well for his followers.

However, both pirates are basically con men with their friendly demeanor being masks. Ben Gunn noted that Captain Flint feared no one, but added the exception of Silver. One could see why as Silver could be charming and courteous on the outside, but upon reaching the titular island, one witnessed the rage and capacity for violence that existed within this man when he coldly murdered Tom Redruth for refusing to join him. Euron likewise can be charming on the outside, but his true nature comes out in certain moments like drowning Lord Botley in a cask of seawater, and cutting Lord Blacktyde into seven pieces for refusing to submit to him.

The similarities seem to end there. Look more closely, and you’ll find plenty of contrasts that separate the two characters.

I’m [Long John] fifty mark you; once, back from this cruise, I set up gentleman in earnest.

-Treasure Island, XI: What I Heard in the Apple Barrel

Lord Balon's eldest brother had never given up the Old Way, even for a day. His Silence, with its black sails and dark red hull, was infamous in every port from Ibben to Asshai, it was said.

-A Clash of Kings, Theon II

Long John Silver has a talking parrot that repeated phrases while Euron in direct contrast has an entire crew of mutes. Silver is actually missing a leg while Euron wears an eye patch despite not missing an eye. Although to be fair, many pirates wore eye patches despite having both eyes, since they frequently had to move above and below decks, from daylight to near darkness. Keeping a patch over one eye adapted it to the darkness, and if a pirate went below decks, he could just switch the patch to the other eye and see in the darkness more easily. In this case, Euron keeps his eye patch to hide his black “crow’s eye” and show his blue “smiling eye,” symbolically showing how he uses his smiling, charming light exterior to hide his dark side. Long John Silver also managed to be a legitimate businessman by owning a pub in Bristol in between acting as a pirate, and he planned to use his share of Flint’s treasure to settle down as a gentleman and retire from piracy. Euron was never engaged in anything resembling legitimate business as he stuck to piracy, and he only left piracy to set himself up as a reaver king of the Ironborn, and basically just do a large-scale version of what he did before.

While Long John Silver did employ murder, he used it in a calculated manner in pursuit of a larger goal. He didn’t kill people randomly, but to get rid of the people likely to stand in the way of his obtaining Flint’s treasure: the sailors who wouldn’t mutiny with him and the people commanding the voyage. Euron also uses murder in a calculated manner against people who oppose him such as his brothers and dissident lords, but he also engages in random acts of violence that don’t provide any clear benefit to himself such as when he murdered a hedge wizard and cut out the tongue of Falia. There is also a level of sadism to his actions that Long John’s lacked such as feeding a warlock to his cohorts, chaining people to the bows of ships, and making the Hewett women serve naked.

Long John Silver also does have some redemptive qualities such as seeming to genuinely care for Jim Hawkins to the point of risking his life when his crew wanted to harm him. Euron wouldn’t have stuck his neck out for Jim, but had the kid’s tongue cut out and used him as a slave at best. Long John also seems to be good to his wife going by the level of trust he put in her while Euron never really seems to genuinely care for anyone but himself. He is unmarried, and doesn’t seem to treat the women he’s laid with well if his mistress Falia is anything to go.

At first glance, Euron Greyjoy has a lot of the qualities that invite admiration of the romantic pirate captain: intelligence, charm, charisma and boldness/daring. However, he lacks the human qualities, ie the honor and nobility often found in these characters that keep them from being just villainous rogues. He is a handsome aristocrat who turns to piracy after being exiled from his home, but unlike other pirates in this trope, neither his backstory nor his present situation evoke any sympathy. He isn’t a good man who is unjustly condemned, but an admitted rapist and murderer who managed to avoid justice for his deeds. He uses the pirate tropes to win support from the Ironborn who esteem the Old Way that glorifies piracy. Martin effectively uses Euron to deconstruct the romantic pirate captain trope by showing how romanticism is often used to pretty up ugly things, in this case, piracy, by revealing the dark reality behind them. Piracy is, at the end of the day, a profession of armed robbery with pirate captains usually being capable of savage cruelty and violence. In real life, good pirate captains like the fictional Peter Blood amongst others were incredibly difficult to find given good people generally avoided such line of work. Even so, no matter how good a man a character like Blood was, he still obtained much of his wealth and prestige from robbing ships and settlements with the justification being that they were Spanish, enemies of Britain. Essentially, it is an argument based on the premise of total war. The Ironborn philosophy is practically the same mindset, but unlike with Blood, we got to see the side of the victims of their predations on the Shield Islands and the North.

The way the Ironborn view piracy can be similar to how plenty of people in the real world view piracy in fiction and even real-life. The reader could ask how could the Ironborn admire people like Euron, to which one could just as easily ask how could people esteem Sir Henry Morgan to the point of naming a popular rum label for him (with the slogan “Live like the Captain”)? Euron and the rest of the Ironborn effectively have the reader critique the romantic attitudes towards piracy found in popular culture.

On a final note, another key difference between Euron and the romantic pirate captain will likely be how his story ends. The pirate captain usually gets a happy ending, settling down with all the considerable wealth he acquired over his career in piracy. After his victory against the French in Jamaica in a final battle, Peter Blood gets his pardon, is made Deputy-Governor of Jamaica, gets the girl, Arabella, and settles down to a comfortable retirement from piracy. Long John Silver, even though he was the main antagonist rather than the protagonist, escaped the Hispaniola with "three hundred or four hundred guineas” likely to reunite with his wife. Euron’s story likely won’t be a happy ending with him winning a glorious final battle before settling down to a comfortable retirement with the beautiful girl, Daenerys, but more likely him being killed with the battle turning out to be a disastrous defeat for his fellow Ironborn.

In this story, where the romantic pirate captain is the villain, he and his fellow pirates will get no hero’s reward, but instead their comeuppance.

We will likely see how his story ends in The Winds of Winter.

#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#euron greyjoy#euron#treasure island#long john silver#captain blood#pirate#robert louis stevenson#grrmartin#grrm#george rr martin#a feast for crows#pirates#game of thrones#piracy#balon greyjoy#house greyjoy

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dunwich Horror

H.P. Lovecraft (1928)

Gorgons and Hydras, and Chimaeras - dire stories of Celaeno and the Harpies - may reproduce themselves in the brain of superstition - but they were there before. They are transcripts, types - the archtypes are in us, and eternal. How else should the recital of that which we know in a waking sense to be false come to affect us all? Is it that we naturally conceive terror from such objects, considered in their capacity of being able to inflict upon us bodily injury? O, least of all! These terrors are of older standing. They date beyond body - or without the body, they would have been the same... That the kind of fear here treated is purely spiritual - that it is strong in proportion as it is objectless on earth, that it predominates in the period of our sinless infancy - are difficulties the solution of which might afford some probable insight into our ante-mundane condition, and a peep at least into the shadowland of pre-existence.

- Charles Lamb: Witches and Other Night-Fears

I.

When a traveller in north central Massachusetts takes the wrong fork at the junction of Aylesbury pike just beyond Dean's Corners he comes upon a lonely and curious country.

The ground gets higher, and the brier-bordered stone walls press closer and closer against the ruts of the dusty, curving road. The trees of the frequent forest belts seem too large, and the wild weeds, brambles and grasses attain a luxuriance not often found in settled regions. At the same time the planted fields appear singularly few and barren; while the sparsely scattered houses wear a surprisingly uniform aspect of age, squalor, and dilapidation.

Without knowing why, one hesitates to ask directions from the gnarled solitary figures spied now and then on crumbling doorsteps or on the sloping, rock-strewn meadows. Those figures are so silent and furtive that one feels somehow confronted by forbidden things, with which it would be better to have nothing to do. When a rise in the road brings the mountains in view above the deep woods, the feeling of strange uneasiness is increased. The summits are too rounded and symmetrical to give a sense of comfort and naturalness, and sometimes the sky silhouettes with especial clearness the queer circles of tall stone pillars with which most of them are crowned.

Gorges and ravines of problematical depth intersect the way, and the crude wooden bridges always seem of dubious safety. When the road dips again there are stretches of marshland that one instinctively dislikes, and indeed almost fears at evening when unseen whippoorwills chatter and the fireflies come out in abnormal profusion to dance to the raucous, creepily insistent rhythms of stridently piping bull-frogs. The thin, shining line of the Miskatonic's upper reaches has an oddly serpent-like suggestion as it winds close to the feet of the domed hills among which it rises.

As the hills draw nearer, one heeds their wooded sides more than their stone-crowned tops. Those sides loom up so darkly and precipitously that one wishes they would keep their distance, but there is no road by which to escape them. Across a covered bridge one sees a small village huddled between the stream and the vertical slope of Round Mountain, and wonders at the cluster of rotting gambrel roofs bespeaking an earlier architectural period than that of the neighbouring region. It is not reassuring to see, on a closer glance, that most of the houses are deserted and falling to ruin, and that the broken-steepled church now harbours the one slovenly mercantile establishment of the hamlet. One dreads to trust the tenebrous tunnel of the bridge, yet there is no way to avoid it. Once across, it is hard to prevent the impression of a faint, malign odour about the village street, as of the massed mould and decay of centuries. It is always a relief to get clear of the place, and to follow the narrow road around the base of the hills and across the level country beyond till it rejoins the Aylesbury pike. Afterwards one sometimes learns that one has been through Dunwich.

Outsiders visit Dunwich as seldom as possible, and since a certain season of horror all the signboards pointing towards it have been taken down. The scenery, judged by an ordinary aesthetic canon, is more than commonly beautiful; yet there is no influx of artists or summer tourists. Two centuries ago, when talk of witch-blood, Satan-worship, and strange forest presences was not laughed at, it was the custom to give reasons for avoiding the locality. In our sensible age - since the Dunwich horror of 1928 was hushed up by those who had the town's and the world's welfare at heart - people shun it without knowing exactly why. Perhaps one reason - though it cannot apply to uninformed strangers - is that the natives are now repellently decadent, having gone far along that path of retrogression so common in many New England backwaters. They have come to form a race by themselves, with the well-defined mental and physical stigmata of degeneracy and inbreeding. The average of their intelligence is woefully low, whilst their annals reek of overt viciousness and of half-hidden murders, incests, and deeds of almost unnameable violence and perversity. The old gentry, representing the two or three armigerous families which came from Salem in 1692, have kept somewhat above the general level of decay; though many branches are sunk into the sordid populace so deeply that only their names remain as a key to the origin they disgrace. Some of the Whateleys and Bishops still send their eldest sons to Harvard and Miskatonic, though those sons seldom return to the mouldering gambrel roofs under which they and their ancestors were born.

No one, even those who have the facts concerning the recent horror, can say just what is the matter with Dunwich; though old legends speak of unhallowed rites and conclaves of the Indians, amidst which they called forbidden shapes of shadow out of the great rounded hills, and made wild orgiastic prayers that were answered by loud crackings and rumblings from the ground below. In 1747 the Reverend Abijah Hoadley, newly come to the Congregational Church at Dunwich Village, preached a memorable sermon on the close presence of Satan and his imps; in which he said:

"It must be allow'd, that these Blasphemies of an infernall Train of Daemons are Matters of too common Knowledge to be deny'd; the cursed Voices of Azazel and Buzrael, of Beelzebub and Belial, being heard now from under Ground by above a Score of credible Witnesses now living. I myself did not more than a Fortnight ago catch a very plain Discourse of evill Powers in the Hill behind my House; wherein there were a Rattling and Rolling, Groaning, Screeching, and Hissing, such as no Things of this Earth could raise up, and which must needs have come from those Caves that only black Magick can discover, and only the Divell unlock".

Mr. Hoadley disappeared soon after delivering this sermon, but the text, printed in Springfield, is still extant. Noises in the hills continued to be reported from year to year, and still form a puzzle to geologists and physiographers.

Other traditions tell of foul odours near the hill-crowning circles of stone pillars, and of rushing airy presences to be heard faintly at certain hours from stated points at the bottom of the great ravines; while still others try to explain the Devil's Hop Yard - a bleak, blasted hillside where no tree, shrub, or grass-blade will grow. Then, too, the natives are mortally afraid of the numerous whippoorwills which grow vocal on warm nights. It is vowed that the birds are psychopomps lying in wait for the souls of the dying, and that they time their eerie cries in unison with the sufferer's struggling breath. If they can catch the fleeing soul when it leaves the body, they instantly flutter away chittering in daemoniac laughter; but if they fail, they subside gradually into a disappointed silence.

These tales, of course, are obsolete and ridiculous; because they come down from very old times. Dunwich is indeed ridiculously old - older by far than any of the communities within thirty miles of it. South of the village one may still spy the cellar walls and chimney of the ancient Bishop house, which was built before 1700; whilst the ruins of the mill at the falls, built in 1806, form the most modern piece of architecture to be seen. Industry did not flourish here, and the nineteenth-century factory movement proved short-lived. Oldest of all are the great rings of rough-hewn stone columns on the hilltops, but these are more generally attributed to the Indians than to the settlers. Deposits of skulls and bones, found within these circles and around the sizeable table-like rock on Sentinel Hill, sustain the popular belief that such spots were once the burial-places of the Pocumtucks; even though many ethnologists, disregarding the absurd improbability of such a theory, persist in believing the remains Caucasian.

II.

It was in the township of Dunwich, in a large and partly inhabited farmhouse set against a hillside four miles from the village and a mile and a half from any other dwelling, that Wilbur Whateley was born at 5 a.m. on Sunday, the second of February, 1913. This date was recalled because it was Candlemas, which people in Dunwich curiously observe under another name; and because the noises in the hills had sounded, and all the dogs of the countryside had barked persistently, throughout the night before. Less worthy of notice was the fact that the mother was one of the decadent Whateleys, a somewhat deformed, unattractive albino woman of thirty-five, living with an aged and half-insane father about whom the most frightful tales of wizardry had been whispered in his youth. Lavinia Whateley had no known husband, but according to the custom of the region made no attempt to disavow the child; concerning the other side of whose ancestry the country folk might - and did - speculate as widely as they chose. On the contrary, she seemed strangely proud of the dark, goatish-looking infant who formed such a contrast to her own sickly and pink-eyed albinism, and was heard to mutter many curious prophecies about its unusual powers and tremendous future.

Lavinia was one who would be apt to mutter such things, for she was a lone creature given to wandering amidst thunderstorms in the hills and trying to read the great odorous books which her father had inherited through two centuries of Whateleys, and which were fast falling to pieces with age and wormholes. She had never been to school, but was filled with disjointed scraps of ancient lore that Old Whateley had taught her. The remote farmhouse had always been feared because of Old Whateley's reputation for black magic, and the unexplained death by violence of Mrs Whateley when Lavinia was twelve years old had not helped to make the place popular. Isolated among strange influences, Lavinia was fond of wild and grandiose day-dreams and singular occupations; nor was her leisure much taken up by household cares in a home from which all standards of order and cleanliness had long since disappeared.

There was a hideous screaming which echoed above even the hill noises and the dogs' barking on the night Wilbur was born, but no known doctor or midwife presided at his coming. Neighbours knew nothing of him till a week afterward, when Old Wateley drove his sleigh through the snow into Dunwich Village and discoursed incoherently to the group of loungers at Osborne's general store. There seemed to be a change in the old man - an added element of furtiveness in the clouded brain which subtly transformed him from an object to a subject of fear - though he was not one to be perturbed by any common family event. Amidst it all he showed some trace of the pride later noticed in his daughter, and what he said of the child's paternity was remembered by many of his hearers years afterward.

'I dun't keer what folks think - ef Lavinny's boy looked like his pa, he wouldn't look like nothin' ye expeck. Ye needn't think the only folks is the folks hereabouts. Lavinny's read some, an' has seed some things the most o' ye only tell abaout. I calc'late her man is as good a husban' as ye kin find this side of Aylesbury; an' ef ye knowed as much abaout the hills as I dew, ye wouldn't ast no better church weddin' nor her'n. Let me tell ye suthin - some day yew folks'll hear a child o' Lavinny's a-callin' its father's name on the top o' Sentinel Hill!'

The only person who saw Wilbur during the first month of his life were old Zechariah Whateley, of the undecayed Whateleys, and Earl Sawyer's common-law wife, Mamie Bishop. Mamie's visit was frankly one of curiosity, and her subsequent tales did justice to her observations; but Zechariah came to lead a pair of Alderney cows which Old Whateley had bought of his son Curtis. This marked the beginning of a course of cattle-buying on the part of small Wilbur's family which ended only in 1928, when the Dunwich horror came and went; yet at no time did the ramshackle Wateley barn seem overcrowded with livestock. There came a period when people were curious enough to steal up and count the herd that grazed precariously on the steep hillside above the old farm-house, and they could never find more than ten or twelve anaemic, bloodless-looking specimens. Evidently some blight or distemper, perhaps sprung from the unwholesome pasturage or the diseased fungi and timbers of the filthy barn, caused a heavy mortality amongst the Whateley animals. Odd wounds or sores, having something of the aspect of incisions, seemed to afflict the visible cattle; and once or twice during the earlier months certain callers fancied they could discern similar sores about the throats of the grey, unshaven old man and his slattemly, crinkly-haired albino daughter.

In the spring after Wilbur's birth Lavinia resumed her customary rambles in the hills, bearing in her misproportioned arms the swarthy child. Public interest in the Whateleys subsided after most of the country folk had seen the baby, and no one bothered to comment on the swift development which that newcomer seemed every day to exhibit. Wilbur's growth was indeed phenomenal, for within three months of his birth he had attained a size and muscular power not usually found in infants under a full year of age. His motions and even his vocal sounds showed a restraint and deliberateness highly peculiar in an infant, and no one was really unprepared when, at seven months, he began to walk unassisted, with falterings which another month was sufficient to remove.

It was somewhat after this time - on Hallowe'en - that a great blaze was seen at midnight on the top of Sentinel Hill where the old table-like stone stands amidst its tumulus of ancient bones. Considerable talk was started when Silas Bishop - of the undecayed Bishops - mentioned having seen the boy running sturdily up that hill ahead of his mother about an hour before the blaze was remarked. Silas was rounding up a stray heifer, but he nearly forgot his mission when he fleetingly spied the two figures in the dim light of his lantern. They darted almost noiselessly through the underbrush, and the astonished watcher seemed to think they were entirely unclothed. Afterwards he could not be sure about the boy, who may have had some kind of a fringed belt and a pair of dark trunks or trousers on. Wilbur was never subsequently seen alive and conscious without complete and tightly buttoned attire, the disarrangement or threatened disarrangement of which always seemed to fill him with anger and alarm. His contrast with his squalid mother and grandfather in this respect was thought very notable until the horror of 1928 suggested the most valid of reasons.

The next January gossips were mildly interested in the fact that 'Lavinny's black brat' had commenced to talk, and at the age of only eleven months. His speech was somewhat remarkable both because of its difference from the ordinary accents of the region, and because it displayed a freedom from infantile lisping of which many children of three or four might well be proud. The boy was not talkative, yet when he spoke he seemed to reflect some elusive element wholly unpossessed by Dunwich and its denizens. The strangeness did not reside in what he said, or even in the simple idioms he used; but seemed vaguely linked with his intonation or with the internal organs that produced the spoken sounds. His facial aspect, too, was remarkable for its maturity; for though he shared his mother's and grandfather's chinlessness, his firm and precociously shaped nose united with the expression of his large, dark, almost Latin eyes to give him an air of quasi-adulthood and well-nigh preternatural intelligence. He was, however, exceedingly ugly despite his appearance of brilliancy; there being something almost goatish or animalistic about his thick lips, large-pored, yellowish skin, coarse crinkly hair, and oddly elongated ears. He was soon disliked even more decidedly than his mother and grandsire, and all conjectures about him were spiced with references to the bygone magic of Old Whateley, and how the hills once shook when he shrieked the dreadful name of Yog-Sothoth in the midst of a circle of stones with a great book open in his arms before him. Dogs abhorred the boy, and he was always obliged to take various defensive measures against their barking menace.

III.

Meanwhile Old Whateley continued to buy cattle without measurably increasing the size of his herd. He also cut timber and began to repair the unused parts of his house - a spacious, peak-roofed affair whose rear end was buried entirely in the rocky hillside, and whose three least-ruined ground-floor rooms had always been sufficient for himself and his daughter.

There must have been prodigious reserves of strength in the old man to enable him to accomplish so much hard labour; and though he still babbled dementedly at times, his carpentry seemed to show the effects of sound calculation. It had already begun as soon as Wilbur was born, when one of the many tool sheds had been put suddenly in order, clapboarded, and fitted with a stout fresh lock. Now, in restoring the abandoned upper storey of the house, he was a no less thorough craftsman. His mania showed itself only in his tight boarding-up of all the windows in the reclaimed section - though many declared that it was a crazy thing to bother with the reclamation at all.

Less inexplicable was his fitting up of another downstairs room for his new grandson - a room which several callers saw, though no one was ever admitted to the closely-boarded upper storey. This chamber he lined with tall, firm shelving, along which he began gradually to arrange, in apparently careful order, all the rotting ancient books and parts of books which during his own day had been heaped promiscuously in odd corners of the various rooms.

'I made some use of 'em,' he would say as he tried to mend a torn black-letter page with paste prepared on the rusty kitchen stove, 'but the boy's fitten to make better use of 'em. He'd orter hev 'em as well so as he kin, for they're goin' to be all of his larnin'.'

When Wilbur was a year and seven months old - in September of 1914 - his size and accomplishments were almost alarming. He had grown as large as a child of four, and was a fluent and incredibly intelligent talker. He ran freely about the fields and hills, and accompanied his mother on all her wanderings. At home he would pore dilligently over the queer pictures and charts in his grandfather's books, while Old Whateley would instruct and catechize him through long, hushed afternoons. By this time the restoration of the house was finished, and those who watched it wondered why one of the upper windows had been made into a solid plank door. It was a window in the rear of the east gable end, close against the hill; and no one could imagine why a cleated wooden runway was built up to it from the ground. About the period of this work's completion people noticed that the old tool-house, tightly locked and windowlessly clapboarded since Wilbur's birth, had been abandoned again. The door swung listlessly open, and when Earl Sawyer once stepped within after a cattle-selling call on Old Whateley he was quite discomposed by the singular odour he encountered - such a stench, he averred, as he had never before smelt in all his life except near the Indian circles on the hills, and which could not come from anything sane or of this earth. But then, the homes and sheds of Dunwich folk have never been remarkable for olfactory immaculateness.

The following months were void of visible events, save that everyone swore to a slow but steady increase in the mysterious hill noises. On May Eve of 1915 there were tremors which even the Aylesbury people felt, whilst the following Hallowe'en produced an underground rumbling queerly synchronized with bursts of flame - 'them witch Whateleys' doin's' - from the summit of Sentinel Hill. Wilbur was growing up uncannily, so that he looked like a boy of ten as he entered his fourth year. He read avidly by himself now; but talked much less than formerly. A settled taciturnity was absorbing him, and for the first time people began to speak specifically of the dawning look of evil in his goatish face. He would sometimes mutter an unfamiliar jargon, and chant in bizarre rhythms which chilled the listener with a sense of unexplainable terror. The aversion displayed towards him by dogs had now become a matter of wide remark, and he was obliged to carry a pistol in order to traverse the countryside in safety. His occasional use of the weapon did not enhance his popularity amongst the owners of canine guardians.

The few callers at the house would often find Lavinia alone on the ground floor, while odd cries and footsteps resounded in the boarded-up second storey. She would never tell what her father and the boy were doing up there, though once she turned pale and displayed an abnormal degree of fear when a jocose fish-pedlar tried the locked door leading to the stairway. That pedlar told the store loungers at Dunwich Village that he thought he heard a horse stamping on that floor above. The loungers reflected, thinking of the door and runway, and of the cattle that so swiftly disappeared. Then they shuddered as they recalled tales of Old Whateley's youth, and of the strange things that are called out of the earth when a bullock is sacrificed at the proper time to certain heathen gods. It had for some time been noticed that dogs had begun to hate and fear the whole Whateley place as violently as they hated and feared young Wilbur personally.

In 1917 the war came, and Squire Sawyer Whateley, as chairman of the local draft board, had hard work finding a quota of young Dunwich men fit even to be sent to development camp. The government, alarmed at such signs of wholesale regional decadence, sent several officers and medical experts to investigate; conducting a survey which New England newspaper readers may still recall. It was the publicity attending this investigation which set reporters on the track of the Whateleys, and caused the Boston Globe and Arkham Advertiser to print flamboyant Sunday stories of young Wilbur's precociousness, Old Whateley's black magic, and the shelves of strange books, the sealed second storey of the ancient farmhouse, and the weirdness of the whole region and its hill noises. Wilbur was four and a half then, and looked like a lad of fifteen. His lips and cheeks were fuzzy with a coarse dark down, and his voice had begun to break.

Earl Sawyer went out to the Whateley place with both sets of reporters and camera men, and called their attention to the queer stench which now seemed to trickle down from the sealed upper spaces. It was, he said, exactly like a smell he had found in the toolshed abandoned when the house was finally repaired; and like the faint odours which he sometimes thought he caught near the stone circle on the mountains. Dunwich folk read the stories when they appeared, and grinned over the obvious mistakes. They wondered, too, why the writers made so much of the fact that Old Whateley always paid for his cattle in gold pieces of extremely ancient date. The Whateleys had received their visitors with ill-concealed distaste, though they did not dare court further publicity by a violent resistance or refusal to talk.

IV.

For a decade the annals of the Whateleys sink indistinguishably into the general life of a morbid community used to their queer ways and hardened to their May Eve and All-Hallows orgies. Twice a year they would light fires on the top of Sentinel Hill, at which times the mountain rumblings would recur with greater and greater violence; while at all seasons there were strange and portentous doings at the lonely farm-house. In the course of time callers professed to hear sounds in the sealed upper storey even when all the family were downstairs, and they wondered how swiftly or how lingeringly a cow or bullock was usually sacrificed. There was talk of a complaint to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals but nothing ever came of it, since Dunwich folk are never anxious to call the outside world's attention to themselves.

About 1923, when Wilbur was a boy of ten whose mind, voice, stature, and bearded face gave all the impressions of maturity, a second great siege of carpentry went on at the old house. It was all inside the sealed upper part, and from bits of discarded lumber people concluded that the youth and his grandfather had knocked out all the partitions and even removed the attic floor, leaving only one vast open void between the ground storey and the peaked roof. They had torn down the great central chimney, too, and fitted the rusty range with a flimsy outside tin stove-pipe.

In the spring after this event Old Whateley noticed the growing number of whippoorwills that would come out of Cold Spring Glen to chirp under his window at night. He seemed to regard the circumstance as one of great significance, and told the loungers at Osborn's that he thought his time had almost come.

'They whistle jest in tune with my breathin' naow,' he said, 'an' I guess they're gittin' ready to ketch my soul. They know it's a-goin' aout, an' dun't calc'late to miss it. Yew'll know, boys, arter I'm gone, whether they git me er not. Ef they dew, they'll keep up a-singin' an' laffin' till break o' day. Ef they dun't they'll kinder quiet daown like. I expeck them an' the souls they hunts fer hev some pretty tough tussles sometimes.'

On Lammas Night, 1924, Dr Houghton of Aylesbury was hastily summoned by Wilbur Whateley, who had lashed his one remaining horse through the darkness and telephoned from Osborn's in the village. He found Old Whateley in a very grave state, with a cardiac action and stertorous breathing that told of an end not far off. The shapeless albino daughter and oddly bearded grandson stood by the bedside, whilst from the vacant abyss overhead there came a disquieting suggestion of rhythmical surging or lapping, as of the waves on some level beach. The doctor, though, was chiefly disturbed by the chattering night birds outside; a seemingly limitless legion of whippoorwills that cried their endless message in repetitions timed diabolically to the wheezing gasps of the dying man. It was uncanny and unnatural - too much, thought Dr Houghton, like the whole of the region he had entered so reluctantly in response to the urgent call.

Towards one o'clock Old Whateley gained consciousness, and interrupted his wheezing to choke out a few words to his grandson.

'More space, Willy, more space soon. Yew grows - an' that grows faster. It'll be ready to serve ye soon, boy. Open up the gates to Yog-Sothoth with the long chant that ye'll find on page 751 of the complete edition, an' then put a match to the prison. Fire from airth can't burn it nohaow.'

He was obviously quite mad. After a pause, during which the flock of whippoorwills outside adjusted their cries to the altered tempo while some indications of the strange hill noises came from afar off, he added another sentence or two.

'Feed it reg'lar, Willy, an' mind the quantity; but dun't let it grow too fast fer the place, fer ef it busts quarters or gits aout afore ye opens to Yog-Sothoth, it's all over an' no use. Only them from beyont kin make it multiply an' work... Only them, the old uns as wants to come back...'

But speech gave place to gasps again, and Lavinia screamed at the way the whippoorwills followed the change. It was the same for more than an hour, when the final throaty rattle came. Dr Houghton drew shrunken lids over the glazing grey eyes as the tumult of birds faded imperceptibly to silence. Lavinia sobbed, but Wilbur only chuckled whilst the hill noises rumbled faintly.

'They didn't git him,' he muttered in his heavy bass voice.

Wilbur was by this time a scholar of really tremendous erudition in his one-sided way, and was quietly known by correspondence to many librarians in distant places where rare and forbidden books of old days are kept. He was more and more hated and dreaded around Dunwich because of certain youthful disappearances which suspicion laid vaguely at his door; but was always able to silence inquiry through fear or through use of that fund of old-time gold which still, as in his grandfather's time, went forth regularly and increasingly for cattle-buying. He was now tremendously mature of aspect, and his height, having reached the normal adult limit, seemed inclined to wax beyond that figure. In 1925, when a scholarly correspondent from Miskatonic University called upon him one day and departed pale and puzzled, he was fully six and three-quarters feet tall.

Through all the years Wilbur had treated his half-deformed albino mother with a growing contempt, finally forbidding her to go to the hills with him on May Eve and Hallowmass; and in 1926 the poor creature complained to Mamie Bishop of being afraid of him.

'They's more abaout him as I knows than I kin tell ye, Mamie,' she said, 'an' naowadays they's more nor what I know myself. I vaow afur Gawd, I dun't know what he wants nor what he's a-tryin' to dew.'

That Hallowe'en the hill noises sounded louder than ever, and fire burned on Sentinel Hill as usual; but people paid more attention to the rhythmical screaming of vast flocks of unnaturally belated whippoorwills which seemed to be assembled near the unlighted Whateley farmhouse. After midnight their shrill notes burst into a kind of pandemoniac cachinnation which filled all the countryside, and not until dawn did they finally quiet down. Then they vanished, hurrying southward where they were fully a month overdue. What this meant, no one could quite be certain till later. None of the countryfolk seemed to have died - but poor Lavinia Whateley, the twisted albino, was never seen again.

In the summer of 1927 Wilbur repaired two sheds in the farmyard and began moving his books and effects out to them. Soon afterwards Earl Sawyer told the loungers at Osborn's that more carpentry was going on in the Whateley farmhouse. Wilbur was closing all the doors and windows on the ground floor, and seemed to be taking out partitions as he and his grandfather had done upstairs four years before. He was living in one of the sheds, and Sawyer thought he seemed unusually worried and tremulous. People generally suspected him of knowing something about his mother disappearance, and very few ever approached his neighbourhood now. His height had increased to more than seven feet, and showed no signs of ceasing its development.

V.

The following winter brought an event no less strange than Wilbur's first trip outside the Dunwich region. Correspondence with the Widener Library at Harvard, the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, the British Museum, the University of Buenos Ayres, and the Library of Miskatonic University at Arkham had failed to get him the loan of a book he desperately wanted; so at length he set out in person, shabby, dirty, bearded, and uncouth of dialect, to consult the copy at Miskatonic, which was the nearest to him geographically. Almost eight feet tall, and carrying a cheap new valise from Osborne's general store, this dark and goatish gargoyle appeared one day in Arkham in quest of the dreaded volume kept under lock and key at the college library - the hideous Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred in Olaus Wormius' Latin version, as printed in Spain in the seventeenth century. He had never seen a city before, but had no thought save to find his way to the university grounds; where indeed, he passed heedlessly by the great white-fanged watchdog that barked with unnatural fury and enmity, and tugged frantically at its stout chaim.

Wilbur had with him the priceless but imperfect copy of Dr Dee's English version which his grandfather had bequeathed him, and upon receiving access to the Latin copy he at once began to collate the two texts with the aim of discovering a certain passage which would have come on the 751st page of his own defective volume. This much he could not civilly refrain from telling the librarian - the same erudite Henry Armitage (A.M. Miskatonic, Ph.D. Princeton, Litt.D. Johns Hopkins) who had once called at the farm, and who now politely plied him with questions. He was looking, he had to admit, for a kind of formula or incantation containing the frightful name Yog-Sothoth, and it puzzled him to find discrepancies, duplications, and ambiguities which made the matter of determination far from easy. As he copied the formula he finally chose, Dr Armitage looked involuntarily over his shoulder at the open pages; the left-hand one of which, in the Latin version, contained such monstrous threats to the peace and sanity of the world.