#another question better to be answered by a scholar of religious studies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Which major characters were created just for the novel and later became worshipped?

Well considering that most of the cast is already full of deities that are worshiped in other Taoism, Buddism, or Chinese folklore I can't really say that the novel created any new characters considering that Wu Cheng'en was taking these already popular stories and legends and just fitting them in a consumable narrative for the public to enjoy.

So short story.... none?

Long story...

I'll say this, I'm not sure if the publication of Wu Cheng'en's version of Xiyouji was the catalyst for making deities like Sun Wukong or Zhu Bajie more well-known or if they were already set practices around that time and place and that the novel created a more 'canon' lore to follow. That sounds more like a historical question if anything that should be looked into like... academic articles would best answer when it comes to early Chinese religious practices.

I know that Sun Wukong was already worshiped before the publication, though I am not sure how widespread the practice was. There are shrines to his earlier name Qi Tian Da Sheng or Sun Xingzhe that are still present today. These acts of worship probably are what lead to including a monkey acolyte in XuanZang's first pilgrimage. From there his name became more widespread and a lot of the modern shrines today are made in the last century or so.

Zhu Bajie was already created before Wu Cheng'en's publication, seen as a deity that is the Taoist marshal Tian Peng Yuan Shuai. Again, I am not aware of how widely known he was but I knew today that Zhu Bajie has been seen as a patron protector for sex workers in Taiwan.

Sha Wujing has legends that he is based upon a sand deity that protected XuanZang when he went to India to fetch the scriptures, a Japanese Buddhist source claiming that he was an avatar of King Vaisravana. I am not sure if this has a lot of bases but he wasn't created for the purpose of the novel at least.

All that being said, all these characters already had creditable backgrounds that were used within the novel but I don't doubt that the publication of the novel is what has kept their legends alive to this day.

Xiyouji is all about religious meanings from many different aspects so it's not crazy to think that Wu Cheng'en was able to find and re-work already established figures into his narrative to create a memorable impression of these deities to new generations.

#journey to the west#xiyouji#wu cheng'en#anon ask#anonymous#anon#another question better to be answered by a scholar of religious studies#zhu bajie#sha wujing#ask

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Institute of Islamic Knowledge

In a fast-paced, constantly evolving world, the need for solid Islamic knowledge has never been more essential. For Muslim families, especially immigrants, ensuring their children and themselves stay rooted in Islamic teachings can be challenging. This is where The Institute of Islamic Knowledge plays a pivotal role. With its comprehensive approach to Islamic education, this institute offers families the opportunity to stay connected to their faith and deepen their understanding of Islamic principles, regardless of where they are in the world.

What is The Institute of Islamic Knowledge?

The Institute of Islamic Knowledge is an online platform dedicated to providing high-quality Islamic education for learners of all ages. It aims to offer structured, accessible, and flexible learning paths to those who seek knowledge about Islam. Whether you’re a beginner learning the basics of Islamic teachings or an advanced student aiming to study the deeper aspects of Islamic jurisprudence, this institute has a wide variety of courses.

At Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm, we strive to offer a similar approach, focusing on delivering a well-rounded Islamic education to help students grow spiritually and intellectually.

Flexibility for Modern Muslim Families

One of the primary reasons immigrant Muslim families turn to The Institute of Islamic Knowledge is its flexible online learning environment. In today’s world, where work schedules, family commitments, and daily responsibilities can often interfere with religious learning, flexibility becomes crucial. This is especially true for those who have relocated to new countries and are adapting to a different way of life.

At Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm, we understand the specific needs of Muslim families living abroad. Our programs are tailored to fit around the busy schedules of working parents, students, and individuals looking to deepen their faith at their own pace.

High-Quality Curriculum Focused on Authentic Islamic Teachings

The courses offered by The Institute of Islamic Knowledge cover a wide array of subjects, including Quranic studies, Hadith, Fiqh, and Islamic history. What sets this institute apart is its commitment to providing authentic and traditional Islamic education that aligns with classical interpretations. Each course is carefully designed to ensure that learners acquire knowledge that not only enriches their understanding of Islam but also prepares them to apply this knowledge in everyday life.

We offer similarly robust curriculums. Our Islamic courses are designed to cater to a diverse audience, from children to adults, ensuring that each participant gains knowledge that is both practical and spiritually uplifting.

Access to Expert Scholars and Teachers

Another benefit of enrolling in Our Islamic platform is the access to knowledgeable scholars and teachers who are well-versed in various branches of Islamic knowledge. These educators offer personalized guidance, ensuring that students understand the subject matter deeply.

Likewise, Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm employs highly qualified instructors who bring years of experience in teaching Islamic studies. Our educators are available to provide support, answer questions, and guide learners in their journey to acquiring Islamic knowledge.

The Role of Islamic Knowledge in Preserving Muslim Identity

For immigrant families, maintaining a strong Muslim identity can be challenging, especially in foreign cultures. By enrolling in institutions, families are better equipped to nurture their children’s understanding of Islamic values and teachings. With access to courses on Islamic etiquette, the stories of the Prophets, and the moral framework of Islam, parents can ensure that their children grow up with a solid foundation in their faith.

At Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm, we are deeply committed to helping families nurture Islamic values. Our platform offers courses tailored for children, young adults, and parents alike, creating a space where the entire family can learn and grow together in their Islamic knowledge.

The Benefits of Online Islamic Learning for Immigrant Families

Online platforms like The Institute of Islamic Knowledge provide significant advantages, especially for Muslim families who may not have access to local mosques or Islamic schools. Some of the benefits include:

Convenience: Courses can be accessed from anywhere, at any time.

Affordability: Online classes are often more cost-effective than in-person sessions.

Wide Range of Topics: Students can choose from various subjects, ensuring a comprehensive Islamic education.

Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm similarly offers a flexible and affordable way for Muslim families to pursue Islamic education. Whether you’re looking to learn how to recite the Quran, understand Islamic jurisprudence, or learn about the lives of the Prophets, our courses provide the perfect solution for busy families.

How to Get Started

Enrolling in The Institute of Islamic Knowledge is easy. Students can register online, choose from a variety of courses, and begin learning right away. The platform offers a range of flexible payment options and even provides access to trial classes for those who wish to explore before committing.

Similarly, at Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm, we offer a 7-day free trial to allow families to experience our courses and see the value we provide. Signing up is simple, and we provide all the tools necessary to start your journey toward gaining Islamic knowledge.

Conclusion

In today’s rapidly changing world, Islamic education is crucial in maintaining and strengthening the faith of Muslim families. For immigrant Muslims, platforms like The Institute of Islamic Knowledge and Madrasatu Nuurul ‘Ilm provide the perfect opportunity to deepen their understanding of Islam while balancing the demands of modern life.

#onlinelearning#learning#quranlearning#islamic#quran kareem#islamic knowledge#islamic teachings#islamicreminders

0 notes

Text

Witches Among Us Book Review

I've been waiting to read this one! This time I've checked it out from work (I work at an academic library) but I plan on buying it once the holidays are over. I really think a book like this is missing within the community and I'm so glad Thorn is the one to have written it.

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

Contents:

Synopsis

What I Liked

What I Didn't Like

Overall Thoughts

Conclusion

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

Published 2024

"Occult references ripple frequently through mainstream culture, Wiccan and witchcraft movements appear trendier than ever, and chances are that you're unknowingly acquainted with at least one witch. Drawing on her expertise as a magical practitioner and religious studies scholar, Thorn Mooney pulls back the curtain, introducing you to this complex world and helping you understand why it holds such intense appeal for so many.

Thorn answers all your questions and dispels common misconceptions while delving into what it means to be a witch, including beliefs and practices. Discover what magic really is and what casting it entails. Gain insights into Wicca's distinctions from witchcraft and how these communities are structured. With this fascinating yet concise guide, you can better understand the witches in your life and the reasons why magical thinking thrives."

-from the back of the book

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

What I Liked

The first thing Thorn Mooney tackles is the question "is witchcraft a religion?" I'm sure everyone reading this immediately has an answer, but what I like about Mooney's answer, which is from a religious scholar perspective, is the nuance. Specifically how categorizing witchcraft as a religion is a boon politically. She then lists all the ways in which witchcraft could be considered a religion, especially when you stop looking at religion from a specifically Christian perspective, which is generally how we model our ideas of religion in the western world. However, she also has an argument for why it ISN'T considered a religion by many practitioners. Such as the political statement of rebellion in not being religious.

There's a chapter which encapsulates some of the more prominent witchcraft traditions, speaking about the differences between traditional Wicca and eclectic Wicca as well as the different Traditional Witchcraft traditions, such as Reclaiming, Feri, Clan of Tubal Cain, etc. Laying out how these differ and are similar can help those from the outside looking in understand what people mean when they are describing traditions outside of Wicca as well as what they mean when they say they are Wiccan (which is misunderstood by people within the witchcraft community, let alone outside of it).

Another chapter ran down the late 19th to early 20th century movements that are integral to the development of the modern witchcraft movement as we know it today. This section I think would be good for all practicing witches to look at. Some things that some people seem to think are exclusive to witchcraft or come from it specifically, don't.

While we all love our independence as witches (which Mooney repeats throughout the book), we do have some common beliefs that are shared throughout the community. Maybe not by all, but definitely by a large majority. Mooney breaks these down in a way which is inclusive of all the different thoughts I've seen floating around the community. There's also a mention of some late 20th century happenings related to "rules" from when the community was trying to become more organized (though this wasn't a sentiment shared by everyone at the time). One discussed was the Principles of Wiccan Belief set out by the Council of American Witches in 1974 Minneapolis, Minnesota. Rarely do I see this list discussed by anyone teaching online but you may run into this in books from the early 2000s or 1990s, among a few other sets of values Mooney discusses as well. It's just a history I don't see discussed and think is good to know even if you don't want to follow it yourself (I don't).

The last chapter discusses controversies in witchcraft as well as social justice in our spaces. This is basically a breakdown of how the community is largely becoming more concerned about cultural appropriation and working for the marginalized. Though she also points out some of the areas in the community which tend to sway the other direction as well. It's a very good look at how we relate to one another as well as the outside world in social justice. If that makes sense.

The last bit I think is really great. Each chapter ends with scholarly sources to learn more as well as sources written by witches themselves. These are considered secondary and primary sources respectively, and I highly encourage anyone reading the book to pick a few from each category in each chapter to put on their reading list. This is a great way to learn more about different subjects discussed in those sections. She also puts a blurb about why certain books are chosen for the extra reading sections.

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

What I Didn't Like

The only aspect I found disappointing about this book was it's discussion of folk/folkloric witchcraft. While discussing both, she focused on people practicing folk magic calling themselves folk witches, whether that be Catholic folk magic or others. While folkloric witchcraft is more about following folklore for inspiration, and folk witchcraft being a shortened form of folkloric. I do think these two are starting to separate however, despite folkloric witchcraft also drawing from folk practices, I would not call a straight folk practitioner a witch. Mostly because this is how the marginalized folk practitioners (such as conjure men and women and hoodoo) have been persecuted in the past (and still today) for their folk ways. But then again, if you're the one calling yourself a witch who am I to say? I just wish there had been more discussion on the importance of folklore.

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

Overall Thoughts

This is a great overview of what witches throughout our community believe, are doing, thinking about and discussing. You could give this book to your mom or coworker to help explain the culture of the modern witchcraft community, both online and off. This can also give a practitioner, especially a newer one, some perspective on what everyone else is talking about and thinking, where ideas are stemming from and what in the world people are talking about when it comes to traditions.

✩₊˚.⋆☾⋆⁺₊✧

Conclusion

If you've been thinking about reading this book, I highly recommend that you do. I don't think it's a necessary read, though I do think it's worth it. You can find the book on Amazon, Audible, with the publisher Llewellyn, Barnes and Noble, Quail Ridge Books, Pentagram Salem, and more.

Other Reviews:

Benebell Wen

1 note

·

View note

Note

Heya, Gemini! Sorry if I'm late for WbW, and I hope you don't mind if I try and make up for it. Going off the other one you already answered, it's a two parter, but no pressure for either!

What's an example of a "Culture between cultures" in any of your settings? As in, some shared identity or cultural phenomenon that can be seen across cultures which otherwise view themselves as very, very distinct. How does each individual group let their uniqueness shine through, within this otherwise common practice?

And now, Politics. Keeping to TCHH (since I think we've had the chance to talk about this one before!), could you tell me more about the institutions and power relationships within the Holy City? Who leads it, who runs it, is there a difference?

Cheers for the ask, mate!

Well, in regards to the question about culture, I do think one of most prevalently shared traits between them (in TCHH) has, in most part, to do with religion, which is especially surprising since all of them are so exceedingly different! Most of the religions in TCHH, in one way or another, incorporate the element fire into their religious practices—from Brechic cremation, to Enitiya’s funerary ‘baptism of fire,’ to fire-eating and fire-dancing as a tradition when it comes to Yeskeli priestesses, as well as ‘burning’ prayers written on slips of paper soaked in naphtha (a flammable liquid) . I didn’t even do this on purpose; I just found that fire as used in religious rites was really cinematic. However, considering how these cultures are entwined, it is not completely implausible that this cultural phenomenon might be the result of a cultural exchange of sorts from the past.

To be completely honest, I did end up making some small tweaks. First, renaming The Holy City. Second, giving The Holy City a twin—so now there are two, and they are, in fact, twin cities. The Sacred Cities of Raniz and Vrene. The first, Raniz, is believed to be where life began, and the other, Vrene, where life will come to an end. The Holy Powers do still reside in Raniz, though. And, just a really quick note, for clarification The Holy Powers refer to the institution at large, while The Holy Order are the sort of social stratum within The Holy Powers, as well as they rank in order of ‘importance.’ I will almost certainly be changing these names once I’ve developed this particular conlang or come across something more distinguishable.

At the top of this social ladder is TCHH’s pope-like equivalent, The Archon (I am still currently undecided on the name, but I’ll use it for now as a placeholder). The Archon, it is said, speaks to and for The Virtues (of which there are six), and has ‘final’ say on all religious doctrine. Directly beneath him are The Prophets, of whom serve a miscellany of functions depending on where The Sacred Cities are politically. They were more so soldiers during The Sacred Cities’ ‘dark age,’ and now they’re glorified missionaries, for lack of a better term. They also stand as rep. for The Archon on foreign soil—the arrival of a prophet from the Raniz to perform a matrimonial or funerary ceremony can and is symbolically interpreted as The Archon himself performing said ceremony.

The High Priests don’t necessarily fall beneath them—they’re quite neck and neck when it comes to ‘rank,’ and can even outrank Prophets in specific cases, since they serve on The Archon’s private council; The Archon himself is picked from this pool of High Priests via secret ballot, though, of course, these ballots can be tampered with or manipulated. Bribery is very common. Below The High Priests, though, are pretty much everyone else—acolytes, who are essentially a priests- and-prophets in training (most acolytes tend to be youth and children captured from borderland villages), as well as religious scholars who study manuscripts of the Hajad (which is the name of the palace where The Archon and The Holy Order reside specifically). There are an abundance of priests within The Sacred Cities—it honestly seems like there’s a prayer house on every corner, but there are priests who fall outside of the jurisdiction of The Holy Powers because of the fact that they don’t live in The Sacred Cities at all.

So, to summarise: religious scholars and acolytes are outranked by priests, who are outranked by arch-priests, who are outranked by high priests and prophets, all of whom answer to The Archon. The hierarchical system of The Holy Powers are quite complex (even I have a difficult time keeping track of all its components). I’ll probably simplify it down the line.

#so much i didn’t get to mention#and it’s not even wbw anymore smh#long post#asks#asks answered#worldbuilding#tchh#writeblr stuff

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

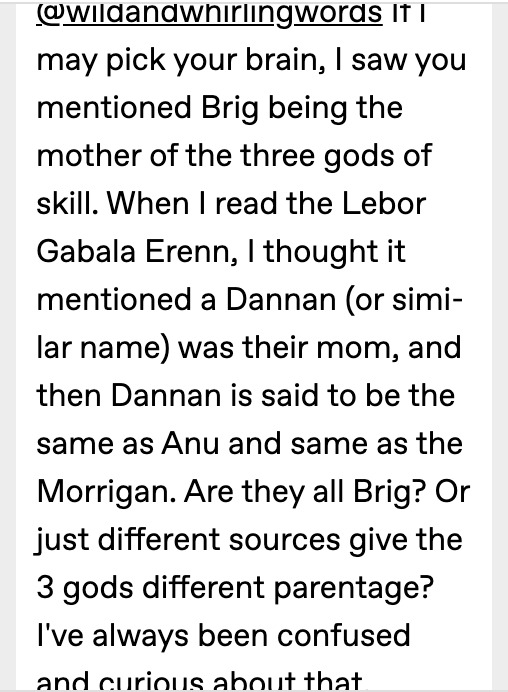

@inkandglitter21

This is a VERY good question! And one that I think keeps quite a few people in the field up at night, to be honest, but I’m going to give the best answer I possibly can, hence why I’m giving it its own post. My apologies in advance if this gets slightly technical - Some of this is kind of inherently technical and complicated. I also am going to HAVE to mention that I’m doing my best to represent the closest thing we can get to a consensus of the field, but that doesn’t mean that someone, in a week or so, can’t publish an article that blows this out of the water. It happens.

As a further warning, which I give every single time I discuss the issues inherent to the study of this material: I am not a religious authority. I’m a Celticist. I love the Tuatha Dé, but I can’t claim any form of spiritual connection with them. (As LGE would say, “Though the author enumerates them, she does not worship them.”) So, to anyone who reads this who might have a connection to the figures described....I can’t say anything about the relationship that you, personally, have with them. I can only say what we know, what we don’t know, and what we’re still kind of scratching our heads at with regards to the medieval material. Part of why I’ve, traditionally, sworn off talking about Bríg, Danu, and Morrigan is specifically because they tend to arouse some very strong feelings, and I never really wanted to get caught in something I couldn’t handle.

But, also. What use is a geas if you don’t break it, likely leading you to your tragic-yet-inevitable doom?

So, first off, let’s talk Lebor Gabála Érenn. MAGNIFICENT text, and a personal baby of mine. Chock full of information about the Tuatha Dé, the Fir Bolg, the Milesians, the High Kings of Ireland....basically everything a person could ever want to know. A mythographer’s dream and nightmare all in one. But, there’s a problem with it, and it’s one that I feel like Celticists have never stressed enough to the public, not the least because Celticists, as a group, tend to be a little....terrified of LGE. There are relatively few scholars who want to work with it after Macalister’s edition (to understand the reception to Macalister: A personal hobby of mine is collecting remarks other scholars have made about his edition, because they can be BRUTAL.) It has been described as “almost unreadable.” Which is kind of forgivable given the man was DYING when he made it, but still.

Why are so many scholars scared of LGE? Well, primarily, because it’s hard to say that there was one singular LGE. LGE, as we know it, was compiled in about the 11th century. Or, it began to be compiled in the 11th century. It’s a Middle Irish text (so, it’s coming significantly later than, say, Tochmarc Étaíne or Cath Maige Tuired, which are both ~9th century texts, though CMT was given revisions in the 11th century to bring it in line with LGE). And it is based off of a MUCH bigger genre of pseudohistorical texts, with many of the older texts being missing or destroyed. (The one generally most mourned by us is the one in Cín Dromma Snechta, which could have dated to as early as the 8th century and definitely contained a sort of proto-LGE. We know this because LGE cites it on occasion, so the tradition didn’t fully die out, we just don’t have the full thing.) So, to begin with, LGE is a mixed bag, based off of essentially all the work that came before it, with the scribes involved basically playing a juggling game with what prior scribes jotted down. (You can see it every once in a while, where a redactor will say something like “Certain ignorant people believe ____, but it is clearly not the case, for _________.”)

It’s almost better to view it as a scrapbook than a single text - You have about 3-4 recensions (different scholars identified different recensions) spread out over around 20 surviving manuscripts, each recension containing significant amounts of detail that vary from their counterparts. Also, studded across LGE, you have a variety of poems that are believed to date either before or at around the same time that LGE was being compiled. (Part of what drives scholars up a WALL with Macalister’s translation is that, besides not identifying the original poets for the poems featured in LGE, he also separated the poems from the text around them. And, as someone who did have to work with that translation....yeah, it is a hot mess. Sorry and RIP, Macalister, but it’s a mess.)

Now, you might wonder: Why am I telling you this? You came at me with a mythography question and I’m hitting you with manuscript studies. But THIS is the context that it’s existing in - I know it’s fairly popular to kind of talk shit about the scribes writing this stuff down, but it’s very important to understand that they were really trying their best to understand this stuff, just like we were. And, between the various recensions of LGE, we can actually SEE the tradition evolve. One of the key ways to know that Something Pre-Christian is going on is if NONE of the redactors could agree on someone. If you see someone’s depiction REALLY shifting around, you know that the redactors were having an issue with them, possibly dealing with multiple contradictory traditions.

Enter the Bríg/Dana/Anu/Morrigan problem. AKA “Things that will cause me to have nightmares.” So, let’s try to take this piece by piece.

The term “Tuatha Dé Danann” is generally accepted to be a later addition. There was not, before a certain time in the Irish mythological tradition, any notion of a goddess named “Danu”. (Established by John Carey in the article, “The name Tuatha Dé Danann”-- Essentially, the term “Tuatha Dé” was the original, but then, with the influence of the term Tuatha Dé, or “Tribe of God” to refer to the Israelites, they felt they had to disambiguate it to “Tuatha Dé Danann”, or “People of Skill”, and then people mistook “Danann” as being the name of a goddess...if I remember correctly, since I don’t have it to hand at the moment.) It is very important to establish this off the bat. Now, how did this get started? And where does this web begun to be woven? Well, I feel like someone could probably write at LEAST a MA dissertation on the topic, possibly even a PhD, and it definitely isn’t going to be me, but I can try my best.

So. The Trí Dé Dána (Three Gods of Skill).

Originally, it seems very likely that the genitive component Dána in their name was not meant to be a proper name. They were not MEANT to be perceived as “The Three Gods of Dana”, but “the three gods of skill”. As noted by O’Rahilly (and GOD, it hurts me when he’s right), the first time we really have the phrase referenced is in Cath Maige Tuired, where, he argues, and I have to agree with him, that it refers to Goibhniu, Luchta, and Credne, who Lugh goes to for weapons to fight against the Fomoire. Additionally, you have a gloss on the 9th century text “Immacallam in Dá Thuarad: Ecna mac na tri nDea nDána” that says that their mother was Bríg, though also seems to indicate, specifically, a connection with the filid, which keeps neatly with the LGE reference (and to the image of Bríg as a poetess. I don’t have enough time to talk Bríg here, but if you want to see what I had to say a while back, I made a post here) After the 12th century, though, when the name “Danu” became associated with the Tuatha Dé, a bunch of medieval scribes looked at “Trí Dé Dána” and thought, not UNREASONABLY, “Oh? This is a reference to Danu? Let’s fix that grammar!” So you have, in some later recensions of LGE, the name “Trí Dé Dána” replaced by “Tré dée Danann/Donand/Danand.” It is vital to mention, as Williams does in Ireland’s Immortals (189), that “Danu/Donu” is never attested, it’s always Donand/Danand. So, from the get-go, trying to identify “Danand” with “Anu” was going to be problematic at best. The general consensus seems to be that Bríg and Bres were the original parents of the Trí Dé, and that it’s very possible that they were, originally, specifically associated with the filid, or poets, with this fitting very neatly into both Bres and Bríg’s associations with the Dagda, Ogma, and, of course, Elatha, but that, with Cath Maige Tuired in the 9th century and the new tradition of Bres as a tyrant, it all got muddled, with traces of it lingering into LGE. (Myth and Mythography)

But, what about “Anu?” Who is this figure? And THIS, my friends, is where things REALLY begin to get fucky. She is identified in Cormac’s Glossary as mater deorum hibernensium, “Mother of the gods of Ireland” - That is beyond doubt. This ties in very naturally with the conflation of Danand/Danu as the mother of the Trí Dé Dána that we discussed earlier. It was, to a certain extent, natural that the two of them would become intertwined.

So, this means that Anu is a genuine pre-Christian figure who became entangled up with the whole Danu business?

Well....

Michael Clarke, in his exploration of the intellectual environment of medieval Ireland, points out that the reference to “Anu” is, in fact, VERY similar to both Isidore of Sevile and in Carolingian mythographical compilations relating to the Greek goddess Cybele, indicating that the scribe, when he was jotting that down, might have very well had that in mind (52-53). Does this mean that they invented ANOTHER goddess and then conflated that goddess with another invented goddess?

...not quite.

Because we still have to account for things like, for example, a mountain known as “The Paps of Anand”, which isn’t easily ascribed to a classical influence. (As noted by Mark Williams, with the typical mixture of good humor and good sense that characterizes his writing,“It beggars belief to think that the Pre-Christian Irish would not have associated so impressively breasted a landscape with a female deity.”) (189). Also, as noted by Williams, even the most skeptical argument cannot explain where Anu comes from. It seems unlikely that they would simply create a goddess out of thin air. Even Danu, as sketchy as her existence is, came from SOMEWHERE, even if it was a linguistic, instead of spiritual, basis. But THEN we have to deal with another question: If this figure is so important, why doesn’t she show up in any of the myths? Why let the Dagda, Lugh, the Morrigan, Midir, Óengus, Ogma, and Nuada have all the fun? The Dagda in particular is as close to a BLATANTLY pre-Christian deity as you can get on-page, so it can’t be chalked up to a simple “They didn’t want to depict the mother of the gods on page.” Mark Williams suggests, tentatively, that Anu might have been a minor Munster figure who swelled in popularity, possibly dropped in by some Munster-based scribes who wanted to bolster their own province’s reputation and, equally tentatively, without further evidence to go on, I have to agree with him. I believe there’s too much evidence to suggest that there was SOMETHING, but that there’s also too little to say that she had the range or influence described, and that it’s very likely that, at the very least, the scribe writing that entry had Cybele on his mind. It’s really, really a mystery, though.

Furthermore, as John Carey notes in “Notes on the Irish War Goddess”....why conflate Anu with the Morrigan? “While it may be plausible....to explain a war-goddess’s possession of sexual characteristics...it is considerably more difficult to follow that chain of thought in reverse in order to account for a land goddess with martial traits. Not is there any evident reason for a conflation of Anu/Anann and the Morrígan unless the former were to some extent linked with war already” pointing out that, relevant to the first paragraph of this, it SEEMS like her inclusion among the daughters of Ernmas was forced on the redactor by a prior tradition (271). Sometimes, she’s a fourth daughter of Ernmas, sometimes she’s a replacement for the Morrigan, sometimes, in the later texts, she’s associated with Danu. It’s like the various authors KNEW they had to include her in there somehow, but they didn’t know how, and she didn’t fit in smoothly once they did. Are we looking at a war/land goddess , obscure enough that the redactor didn’t know where to put her, deciding that she HAD to be the Morrigan/one of the Morrigan’s sisters but not knowing exactly how to fit her in? It wouldn’t be the first time multiple traditions clashed like this. Also, as noted by Sharon Paice Macleod, who gave a very thorough (if not always, in my opinion, sufficiently contextual) account of the tradition, there is a location called the “Paps of the Morrigan”, further suggesting a fertility aspect to the Morrigan that also features into Carey’s earlier argument of dual aspects to the Irish war goddess, along with Bhreatnach’s suggestion of the sovereignty goddess, who represents the land in the medieval Irish literary tradition (and into the present) also functioning as a goddess of death. (Indeed, as noted by Bhreatnach, the hag Cailb from Togail Bruidne Dá Derga, who functions as a sort of anti-sovereignty goddess, identifies herself with Nemain and Badb, at 255. Sovereignty giveth, sovereignty taketh away when you don’t fulfill your place as king.)

Basically, as with almost everything relating to pre-Christian religion in Ireland, we’ve really, really got to shrug our shoulders and go “Fuck if I know, mate.”

My best attempt at a tl;dr for...this:

LGE - WEIRD

Danu - Help us.

Trí Dé - Who’s your daddy? (Most likely? Bres originally, though it got out of hand after, like, the 12th century.)

Anu - Who are you? (Who, Who?)

Sources:

Scowcroft, “Leabhar Gabhála Part I: The growth of the text" (For the discussion on the different recensions of LGE.)

John Carey, “The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory”

T.F O’Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology

Máire Bhreathnach, “The Sovereignty Goddess as Goddess of Death”

John Carey, “The name Tuatha Dé Danann”

Mark Williams, Ireland’s Immortals (Who, really, puts this all together in a so much more cohesive way in his book, I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to get an idea of how these things develop.)

John Carey, “Myth and Mythography in Cath Maige Tuired.”

Michael Clarke, “Linguistic Education and Literary Creativity in Medieval Ireland”.

John Carey, “Notes on the Irish War Goddess”

Sharon Paice Macleod, “Mater Deorum Hibernensium: Identity and Cross-Correlation in Early Irish Mythology.”

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who’s right about the myths and what does it mean to be culturally Christian? (using Pan as an example)

Thanks to @will-o-the-witch for looking over the part on Judaism!! : )

Disclaimer:

The ancient world was incredibly diverse and ideas about the gods themselves and the myths varied a lot across space and time, which is something I’ll be mentioning again later. I feel like it’s important to have a better understanding about the myths since they’re so prevalent in culture. Essentially, while many people today may tend to think there’s only one “right” way to see the myths or a god this was and is not the case for many faiths. To show this, I wanted to use Pan and his parentage as an example. This also connects to a broader idea: cultural Christianity (which isn’t “bad” or “good”, it’s just something to be aware of). This isn’t about Christians either, just about how cultural Christianity can affect peoples’ perception of other faiths. Whether or not someone is Christian themselves, growing up in a Christian place can incorrectly inform how they learn about other faiths which can lead to misinformation being spread. Sometimes it can (even accidentally) reinforce very harmful ideas that can contribute to bigotry like antisemitism, which we have to fight against! (Seriously, bigotry sucks! Also I hope the way I word all this makes sense because it’s something I care a lot about!)

So, who are Pan’s parents and who’s right?

Pan is often known as Hermes’ son, even the Homeric hymn to Pan says so (1). Hermes is widely known as the “second youngest Olympian”, which would make Pan among the very youngest if this genealogy is considered (2).

However, that isn’t the genealogy everyone in the ancient world used to describe Pan. There are many variations on his parentage, and I think it’s worth going over because of how interesting it is. Who Pan’s parents are often changes depending on who you ask or where you ask it. For example, at times he has been called the son of Hermes (1, 3: pg90,151), if you ask 5th century Athenians he is the son of Chronos (3: pg42, 88), he was also known as the son of Zeus and twin of Arcas’ (3: pg43), the great grandson of Pelasgos who was a mortal, bother or foster brother of Zeus (3: pg113) and in Thebes he was believed to be the son of Apollo (3: pg180). He was also called Son of Aix (the solar goat too bright to look at, equated with Amalthea nurse of Zeus) (3: pg100). There were likely other variations too that were lost to history.

One thing worth noting is that Pan originated in Arcadia and before the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, his worship was mainly preformed here and it was only after that battle that his worship spread widely to the rest of Greece (4, 5). So, the myths of Pan from Arcadia are typically older and reflected older views that worshipers held of him. One example is that Pan helped Zeus in the war against the titans and these myths point to Pan’s father being Chronos (or at least placing him before Hermes’ birth):

Pan has been described as “the source of that "panic" fear with whose aid he helped the gods in their war against the Titans …” and the son of Cronos and a she-goat (3: pg42). In fact, Aeschylus believed Pan to be two gods: both of which had the power of panic and one of them fought against the titans with Zeus (3: pg42) this is interesting because in other myths Pan was able to split up into a swarm of pans, so Pan being a multiplicity of gods and also a single god isn’t unheard of (3: pg100). Overall, most people understood him to be one god (like we do today), but this just shows how much diversity there was in how people saw him.

And in Egypt he was viewed similarly to the Pan who fought in the war with the titans (as one of the oldest gods):

“…the Egyptians Pan is considered very ancient and one of the eight gods said to be the earliest…(6)”

Here he was identified with the Egyptian god Min, which may seem a bit problematic to some because otherwise they were revered as different gods (6). However, the practice of identifying gods with other gods (aka syncretism) was not uncommon in the ancient world; Hekate-Artemis, Selene-Hekate, and Selene-Artemis were identified with each other commonly (7, 8). Other syncretisms were between Isis and Demeter, Isis and Persephone, Isis and Aphrodite, and Isis and Venus (9: pg 20). I am not a classics student, but what I have taken away from this is that the identity of the ancient gods is somewhat fluid and many worshipers could have differing and even contradictory views without either of them being “wrong”, even though some likely did argue or disagree to some extent (6). I’m not claiming there wasn’t debate in the ancient world about the gods, there definitely was. What I’m saying is that people did not fight to discredit new or different ideas just because they conflicted with already established ideas. There was a great deal of variation in how people worshiped and most weren’t interested in a one “right way” to do things.

This isn’t only an ancient practice: it still happens today in Shinto in general and with the kamisama* Inari Ōkami (稲荷大神), who has been portrayed as a group of kamisama, as masculine, androgynous, and feminine (10). So in general this practice of seeing kamisama (or supernatural beings, or gods) in many different ways with acceptance is more common than one might expect (10, 11). This also happens today in Judaism, where debate is very common:

“Nevertheless, the general trend throughout Jewish history is to value debate and not to stifle it, and the history of Jewish texts supports that trend. (12)” Some examples of this are how many Jewish people debate the Talmud (a religious text) and how there are many different sects of Judaism.

One important thing for people who are interested in this subject and were raised in a Christian culture (even if they aren’t religious) is to not overextend the characteristics of Christianity onto other religions ancient or modern (this is often accidental, which makes it even more important to be aware of it). This is relevant to both ancient and modern religions such as Shinto and Judaism because misunderstanding these faiths can contribute to terrible things like antisemitism and xenophobia (more so with Judaism). So, we need to guard against bigotry like that by being open to learning and changing our opinions when they are wrong both for learning and fighting bigotry.

In fact, one scholar noted that even in Arcadia Pan’s cult and myth were not standardized although what I have mentioned before was certainly the more popular (13: pg 63) So, even though Herodotus heard from people in Egypt who worshiped Min, it is not unheard of or unreasonable to understand that some people did understand him that way. To answer the question I asked earlier: each myth about Pan’s parentage has some element of truth to it and none of them are completely “right” or “wrong”. For example, Hermes being Pan’s father echoes the fact that both of them are liminal deities and usually are shown being close to mortals (3: 178).

Conclusion:

Pan is commonly considered the son of Hermes, however there was immense variation in how others saw him, both across space and time. One specific idea- that Pan helped Zeus in the war against the titans and that he is among the eldest of the gods- would contradict the Hermes genealogy and was prevalent in some areas. This is the case in Egypt where he was conflated with the local god Min. While this could seem confusing to modern readers (both the Min thing and the various genealogy thing), many faiths both ancient and modern do not push for one “right way” of seeing things and this is important to understand when learning about these things.

Another way of looking at this concept is the idea of cultural Christianity. It does not matter if a person is religious or even Christian, by growing up in a culturally Christian place their assumptions about other faiths are automatically informed by Christianity, which does not reflect most other faiths. This is not good or bad, it’s just something to be aware of and work around so that we can better understand these other faiths. It is especially important to keep in mind today as misunderstandings about religions can contribute to dangerous bigotry like antisemitism, which we must stand against!

*In Shinto kami (or kamisama) are supernatural beings who inspire awe, they are the main object of worship in Shinto. Please don’t call Shinto kamisama “gods”, it’s inaccurate and doesn’t represent how people see them. Due to how Shinto and Japanese mythology are different from Western mythology we need to take care when talking about it to keep it in its original context.

Citations:

1: Hymn 19 to Pan Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Ed. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=HH+19

2: da Costa Martins, P. A., Leptidis, S., & De Windt, L. J. (2014). Nuclear Calcium Transients: Hermes Propylaios in the Heart. Doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010675

3: Borgeaud, P., & Atlass, K. (1988). The cult of Pan in ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 13: 9780226065953

4: GARTZIOU-TATTI, A. (2013). GODS, HEROES, AND THE BATTLE OF MARATHON. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, (124), 91-110. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/44216258

5: Haldane, J. (1968). Pindar and Pan: Frs. 95-100 Snell. Phoenix, 22(1), 18-31. doi:10.2307/1087034

6: Griffiths, J. G. (1955). The orders of Gods in Greece and Egypt (according to Herodotus). The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 75, 21-23. Doi: 10.2307/629164

7: MANOLEDAKIS, M. (2012). Hekate with Apollo and Artemis on a Gem from the Southern Black Sea Region. Istanbuler Mitteilungen, 62, 289-302.

8: E. Hijmans, S. (2012). Moon deities, Greece and Rome. In The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (eds R.S. Bagnall, K. Brodersen, C.B. Champion, A. Erskine and S.R. Huebner). doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17276

9: Witt, R. E. (1997). Isis in the ancient world. JHU Press. ISBN-13: 978-0801856426

10: Smyers, K. (1996). "My Own Inari": Personalization of the Deity in Inari Worship. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 23(1/2), 85-116. Retrieved June 23, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/30233555

11: Lya. 2015. Interview with Gary Cox - Inari Faith International (VO) https://www.equi-nox.net/t10647-interview-with-gary-cox-inari-faith-international-vo

12: Mjl. Conversation & Debate. www.myjewishlearning.com. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/conversation-debate/

13: Ogden, D. (Ed.). (2010). A companion to Greek religion. John Wiley & Sons. Print ISBN:9781405120548 |Online ISBN:9780470996911 |DOI:10.1002/9780470996911

#pandeity#hellenic gods#cultural christianity#i hope i worded this well enough because i really care about this issue#happy to hear other peoples' thoughts too!#greek mythology#hellenic polytheism

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

BASICS OF ISLAM : Morals and Manners : Studying and Learning.Part4

The Qur’an mentions the adab of sitting in the gatherings where a scholar or spiritual guide is teaching to increase one’s faith and knowledge:

O you who believe! When you are told, “Make room in the assemblies (for one another and for new comers),” do make room. God will make room for you (in His grace and Paradise). And when you are told, “Rise up (and leave the assembly),” then do rise up. God will raise (in degree) those of you who truly believe (and act accordingly), and in degrees those who have been granted the knowledge (especially of religious matters). Surely God is fully aware of all that you do. (Mujadila 58:11)

When knowledge, which leads one to greater piety and a better religious life, and allows others to benefit, is added to faith, God will exalt its owner by many ranks.

God commanded the Prophet, “(O Muhammad,) Say, ‘O my Lord, increase me in knowl- edge!’” (TaHa 20:114).

In full submission to this Divine order, the Prophet prayed,

“O God, make the knowledge You have taught me benefit me, and continue to teach me knowledge that will benefit me. Increase me in knowledge. God be praised at all times.”

This prayer in which Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, asks God to make his knowledge beneficial to him is also complemented by another prayer in which he sought refuge in God from knowledge that would not prove beneficial.

Why do humans learn?

Why should knowledgeable people be so highly regarded above all others? The answer to these questions can be found in the Qur’an:

“Of all His servants, only those possessed of true knowledge stand in awe of God…” (Fatir 35:28).

So it can be said that one reason for this is that scholars make it possible for others to know God better and to better understand the message of the Prophets of God.

God’s Messenger taught that it was worthwhile to envy two things. One of these is when someone takes the possessions God has bestowed on them and spends them in the way of God. The other is when someone blessed with knowledge and wisdom becomes a teacher and shares that wisdom with others.This means that when one acquires knowledge, one should then teach it to others; it is not wrong to “envy” (desire to be like) a person who does this.

The Prophet said the following regarding studying, literacy, education, making our knowledge a source of good for others, and educating others:

“It is incumbent upon all Muslims to acquire knowledge.”

As we can see, studying and learning are of critical importance in Islam. These hadith confirm the Prophet’s teaching,

“Knowledge and wisdom are the common property of every believer; wherever they are found, they should be acquired.”

The technology we have today is without a doubt the product of knowledge. It is easy to understand, looking from the perspective of the heights of knowledge, from the science and technology that have been achieved in the modern world, why Islam emphasizes knowledge and education so strongly. Is it possible to ignore its importance when we are surrounded by all the useful fruits and products of intellectual inquiry?

Certainly we must listen well to the teachings of Islam on this matter and show greater concern for educating the next generation if we are to solve some of the current harmful trends. Instead of leaving them material possessions, we should spend our money to make sure they receive opportunities to become truly “rich” in knowledge.

Ali ibn Abu Talib said,

“Someone who has money will have to protect it, whereas a person who has knowledge will be protected by it. Knowledge is a king; possessions are captives. And when possessions are spent they diminish, while knowledge increases when shared.”

Highlighting the excellence of knowledge Prophet Muhammad, peace and blessings be upon him, said,

“Be of those who teach or those who learn, those who listen, or those who love knowledge. If you are not in at least one of these groups, you are headed for destruction.”

The adab of learning applies not only to those who are teaching and learning religious studies but all types of useful knowledge. Here we give some details for our younger brothers and sisters who are students, regarding the adab of learning to add to what has been quoted above:

If at first you don’t succeed do not lose heart.

Classes should be entered with a mind that is prepared and willing.

Listen to a teacher with your spiritual ears.

When you don’t understand something, always ask.

Try to make friends with successful students and get tips from them.

Always plan and organize your time.

Always try to be the best.

Don’t go on to something else until you have understood what you are working on.

If what you are studying is practically applicable, learn it through application.

Do not maintain ties with people who discourage you from learning or dislike your studying.

Be respectful and humble towards your teachers.

#allah#god#islam#muslim#quran#revert#convert#conevrt islam#revert islam#reverthelp#revert help#revert help team#help#islamhelp#converthelp#prayer#salah#muslimah#reminder#pray#dua#hijab#religion#mohammad#new muslim#new revert#new convert#how to convert to islam#convert to islam#welcome to islam

1 note

·

View note

Text

A History Of God – The 4,000-year quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam

“I say that religion isn’t about believing things. It’s ethical alchemy. It’s about behaving in a way that changes you, that gives you intimations of holiness and sacredness.” — Karen Armstrong on Powells.com

book by Karen Armstrong (2004)

The idea of a single divine being – God, Yahweh, Allah – has existed for over 4,000 years. But the history of God is also the history of human struggle. While Judaism, Islam and Christianity proclaim the goodness of God, organised religion has too often been the catalyst for violence and ineradicable prejudice. In this fascinating, extensive and original account of the evolution of belief, Karen Armstrong examines Western society’s unerring fidelity to this idea of One God and the many conflicting convictions it engenders. A controversial, extraordinary story of worship and war, A History of God confronts the most fundamental fact – or fiction – of our lives.

____________________________________

Review: Armstrong, a British journalist and former nun, guides us along one of the most elusive and fascinating quests of all time – the search for God. Like all beloved historians, Armstrong entertains us with deft storytelling, astounding research, and makes us feel a greater appreciation for the present because we better understand our past. Be warned: A History of God is not a tidy linear history. Rather, we learn that the definition of God is constantly being repeated, altered, discarded, and resurrected through the ages, responding to its followers’ practical concerns rather than to mystical mandates. Armstrong also shows us how Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have overlapped and influenced one another, gently challenging the secularist history of each of these religions. – Gail Hudson

____________________________________

The Introduction to A History of God:

As a child, I had a number of strong religious beliefs but little faith in God. There is a distinction between belief in a set of propositions and a faith which enables us to put our trust in them. I believed implicitly in the existence of God; I also believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the efficacy of the sacraments, the prospect of eternal damnation and the objective reality of Purgatory. I cannot say, however, that my belief in these religious opinions about the nature of ultimate reality gave me much confidence that life here on earth was good or beneficent. The Roman Catholicism of my childhood was a rather frightening creed. James Joyce got it right in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: I listened to my share of hell-fire sermons. In fact Hell seemed a more potent reality than God, because it was something that I could grasp imaginatively. God, on the other hand, was a somewhat shadowy figure, defined in intellectual abstractions rather than images. When I was about eight years old, I had to memorise this catechism answer to the question, ‘What is God?’: ‘God is the Supreme Spirit, Who alone exists of Himself and is infinite in all perfections.’ Not surprisingly, it meant little to me and I am bound to say that it still leaves me cold. It has always seemed a singularly arid, pompous and arrogant definition. Since writing this book, however, I have come to believe that it is also incorrect.

As I grew up, I realised that there was more to religion than fear. I read the lives of the saints, the metaphysical poets, T. S. Eliot and some of the simpler writings of the mystics. I began to be moved by the beauty of the liturgy and, though God remained distant, I felt that it was possible to break through to him and that the vision would transfigure the whole of created reality. To do this I entered a religious order and, as a novice and a young nun, I learned a good deal more about the faith. I applied myself to apologetics, scripture, theology and church history. I delved into the history of the monastic life and embarked on a minute discussion of the Rule of my own order, which we had to learn by heart. Strangely enough, God figured very little in any of this. Attention seemed focused on secondary details and the more peripheral aspects of religion. I wrestled with myself in prayer, trying to force my mind to encounter God but he remained a stern taskmaster, who observed my every infringement of the Rule, or tantalisingly absent. The more I read about the raptures of the saints, the more of a failure I felt. I was unhappily aware that what little religious experience I had, had somehow been manufactured by myself as I worked upon my own feelings and imagination. Sometimes a sense of devotion was an aesthetic response to the beauty of the Gregorian chant and the liturgy. But nothing had actually happened to me from a source beyond myself. I never glimpsed the God described by the prophets and mystics. Jesus Christ, about whom we talked far more than about ‘God’, seemed a purely historical figure, inextricably embedded in late antiquity. I also began to have grave doubts about some of the doctrines of the Church. How could anybody possibly know for certain that the man Jesus had been God incarnate and what did such a belief mean? Did the New Testament really teach the elaborate – and highly contradictory – doctrine of the Trinity or was this, like so many other articles of the faith, a fabrication by theologians centuries after the death of Christ in Jerusalem?

Eventually, with regret, I left the religious life and once freed of the burden of failure and inadequacy, I felt my belief in God slip quietly away. He had never really impinged upon my life, though I had done my best to enable him to do so. Now that I no longer felt so guilty and anxious about him, he became too remote to be a reality. My interest in religion continued, however, and I made a number of television programmes about the early history of Christianity and the nature of the religious experience. The more I learned about the history of religion, the more my earlier misgivings were justified. The doctrines that I had accepted without question as a child were indeed man-made, constructed over a long period of time. Science seemed to have disposed of the Creator God and biblical scholars had proved that Jesus had never claimed to be divine. As an epileptic, I had flashes of vision that I knew to be a mere neurological defect: had the visions and raptures of the saints also been a mere mental quirk? Increasingly, God seemed an aberration, something that the human race had outgrown.

Despite my years as a nun, I do not believe that my experience of God is unusual. My ideas about God were formed in childhood and did not keep abreast of my growing knowledge in other disciplines. I had revised simplistic childhood views of Father Christmas; I had come to a more mature understanding of the complexities of the human predicament than had been possible in the kindergarten. Yet my early, confused ideas about God had not been modified or developed. People without my peculiarly religious background may also find that their notion of God was formed in infancy. Since those days, we have put away childish things and have discarded the God of our first years.

Yet my study of the history of religion has revealed that human beings are spiritual animals. Indeed, there is a case for arguing that Homo sapiens is also Homo religiosus. Men and women started to worship gods as soon as they became recognisably human; they created religions at the same time as they created works of art. This was not simply because they wanted to propitiate powerful forces but these early faiths expressed the wonder and mystery that seems always to have been an essential component of the human experience of this beautiful yet terrifying world. Like art, religion has been an attempt to find meaning and value in life, despite the suffering that flesh is heir to. Like any other human activity, religion can be abused but it seems to have been something that we have always done. It was not tacked on to a primordially secular nature by manipulative kings and priests but was natural to humanity. Indeed, our current secularism is an entirely new experiment, unprecedented in human history. We have yet to see how it will work. It is also true to say that our Western liberal humanism is not something that comes naturally to us; like an appreciation of art or poetry, it has to be cultivated. Humanism is itself a religion without God – not all religions, of course, are theistic. Our ethical secular ideal has its own disciplines of mind and heart and gives people the means of finding faith in the ultimate meaning of human life that were once provided by the more conventional religions.

When I began to research this history of the idea and experience of God in the three related monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, I expected to find that God had simply been a projection of human needs and desires. I thought that ‘he’ would mirror the fears and yearnings of society at each stage of its development. My predictions were not entirely unjustified but I have been extremely surprised by some of my findings and I wish that I had learned all this thirty years ago, when I was starting out in the religious life. It would have saved me a great deal of anxiety to hear – from eminent monotheists in all three faiths – that instead of waiting for God to descend from on high, I should deliberately create a sense of him for myself. Other Rabbis, priests and Sufis would have taken me to task for assuming that God was – in any sense – a reality ‘out there’; they would have warned me not to expect to experience him as an objective fact that could be discovered by the ordinary rational process. They would have told me that in an important sense God was a product of the creative imagination, like the poetry and music that I found so inspiring. A few highly respected monotheists would have told me quietly and firmly that God did not really exist – and yet that ‘he’ was the most important reality in the world.

This book will not be a history of the ineffable reality of God itself, which is beyond time and change, but a history of the way men and women have perceived him from Abraham to the present day. The human idea of God has a history, since it has always meant something slightly different to each group of people who have used it at various points of time. The idea of God formed in one generation by one set of human beings could be meaningless in another. Indeed, the statement: ‘I believe in God’ has no objective meaning, as such, but like any other statement it only means something in context, when proclaimed by a particular community. Consequently there is not one unchanging idea contained in the word ‘God’ but the word contains a whole spectrum of meanings, some of which are contradictory or even mutually exclusive. Had the notion of God not had this flexibility, it would not have survived to become one of the great human ideas. When one conception of God has ceased to have meaning or relevance, it has been quietly discarded and replaced by a new theology. A fundamentalist would deny this, since fundamentalism is anti-historical: it believes that Abraham, Moses and the later prophets all experienced their God in exactly the same way as people do today. Yet if we look at our three religions, it becomes clear that there is no objective view of ‘God’: each generation has to create the image of God that works for them. The same is true of atheism. The statement ‘I do not believe in God’ has always meant something slightly different at each period of history. The people who have been dubbed ‘atheists’ over the years have always been denied a particular conception of the divine. Is the ‘God’ who is rejected by atheists today, the God of the patriarchs, the God of the prophets, the God of the philosophers, the God of the mystics or the God of the eighteenth-century deists? All these deities have been venerated as the God of the Bible and the Koran by Jews, Christians and Muslims at various points of their history. We shall see that they are very different from one another. Atheism has often been a transitional state: thus Jews, Christians and Muslims were all called ‘atheists’ by their pagan contemporaries because they had adopted a revolutionary notion of divinity and transcendence. Is modern atheism a similar denial of a God’ which is no longer adequate to the problems of our time?

Despite its other-worldliness, religion is highly pragmatic. We hall see that it is far more important for a particular idea of God to work than for it to be logically or scientifically sound. As soon as it ceases to be effective it will be changed – sometimes for something radically different. This did not disturb most monotheists before our own day because they were quite clear that their ideas about God were not sacrosanct but could only be provisional. They were man-made – they could be nothing else – and quite separate from the indescribable Reality they symbolised. Some developed quite audacious ways of emphasising this essential distinction. One medieval mystic went so far as to say that this ultimate Reality – mistakenly called ‘God’ – was not even mentioned in the Bible. Throughout history, men and women have experienced a dimension of the spirit that seems to transcend the mundane world. Indeed, it is an arresting characteristic of the human mind to be able to conceive concepts that go beyond it in this way. However we choose to interpret it, this human experience of transcendence has been a fact of life. Not everybody would regard it as divine: Buddhists, as we shall see, would deny that their visions and insights are derived from a supernatural source; they see them as natural to humanity. All the major religions, however, would agree that it is impossible to describe this transcendence in normal conceptual language. Monotheists have called this transcendence ‘God’ but they have hedged this around with important provisos. Jews, for example, are forbidden to pronounce the sacred Name of God and Muslims must not attempt to depict the divine in visual imagery. The discipline is a reminder that the reality that we call ‘God’ exceeds all human expression.

This will not be a history in the usual sense, since the idea of God has not evolved from one point and progressed in a linear fashion to a final conception. Scientific notions work like that but the ideas of art and religion do not. Just as there are only a given number of themes in love poetry, so too people have kept saying the same things about God over and over again. Indeed, we shall find a striking similarity in Jewish, Christian and Muslim ideas of the divine. Even though Jews and Muslims both find the Christian doctrines of the Trinity and Incarnation almost blasphemous, they have produced their own versions of these controversial theologies. Each expression of these universal themes is slightly different, however, showing the ingenuity and inventiveness of the human imagination as it struggles to express its sense of ‘God’.

Because this is such a big subject, I have deliberately confined myself to the One God worshipped by Jews, Christians and Muslims, though I have occasionally considered pagan, Hindu and Buddhist conceptions of ultimate reality to make a monotheistic point clearer. It seems that the idea of God is remarkably close to ideas in religions that developed quite independently. Whatever conclusions we reach about the reality of God, the history of this idea must tell us something important about the human mind and the nature of our aspiration. Despite the secular tenor of much Western society, the idea of God still affects the lives of millions of people. Recent surveys have shown that ninety-nine per cent of Americans say that they believe in God: the question is which ‘God’ of the many on offer do they subscribe to?

Theology often comes across as dull and abstract but the history of God has been passionate and intense. Unlike some other conceptions of the ultimate, it was originally attended by agonising struggle and stress. The prophets of Israel experienced their God as a physical pain that wrenched their every limb and filled them with rage and elation. The reality that they called God was often experienced by monotheists in a state of extremity: we shall read of mountain tops, darkness, desolation, crucifixion and terror. The Western experience of God seemed particularly traumatic. What was the reason for this inherent strain? Other monotheists spoke of light and transfiguration. They used very daring imagery to express the complexity of the reality they experienced, which went far beyond the orthodox theology. There has recently been a revived interest in mythology, which may indicate a widespread desire for a more imaginative expression of religious truth. The work of the late American scholar Joseph Campbell has become extremely popular: he has explored the perennial mythology of mankind, linking ancient myths with those still current in traditional societies, is often assumed that the three God-religions are devoid of mythology and poetic symbolism. Yet, although monotheists originally rejected the myths of their pagan neighbours, these often crept back into the faith at a later date. Mystics have seen God incarnated a woman, for example. Others reverently speak of God’s sexuality and have introduced a female element into the divine.

This brings me to a difficult point. Because this God began as a specifically male deity, monotheists have usually referred to it as ‘he’. In recent years, feminists have understandably objected to this. Since I shall be recording the thoughts and insights of people who called God ‘he’, I have used the conventional masculine terminology, except when ‘it’ has been more appropriate. Yet it is perhaps worth mentioning that the masculine tenor of God-talk is particularly problematic in English. In Hebrew, Arabic and French, however, grammatical gender gives theological discourse a sort of sexual counterpoint and dialectic, which provides a balance that is often lacking in English. Thus in Arabic al-Lah (the supreme name for God) is grammatically masculine, but the word for the divine and inscrutable essence of God – al-Dhat – is feminine.

All talk about God staggers under impossible difficulties. Yet monotheists have all been very positive about language at the same time as they have denied its capacity to express the transcendent reality. The God of Jews, Christians and Muslims is a God who – in some sense – speaks. His Word is crucial in all three faiths. The Word of God has shaped the history of our culture. We have to decide whether the word ‘God’ has any meaning for us today.

____________________________________

Biography Karen Armstrong is the author of numerous other books on religious affairs –including A History of God, The Battle for God, Holy War, Islam, Buddha, and The Great Transformation – and two memoirs, Through the Narrow Gate and The Spiral Staircase. Her work has been translated into forty-five languages. She has addressed members of the U.S. Congress on three occasions; lectured to policy makers at the U.S. State Department; participated in the World Economic Forum in New York, Jordan, and Davos; addressed the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington and New York; is increasingly invited to speak in Muslim countries; and is now an ambassador for the UN Alliance of Civilizations. In February 2008 she was awarded the TED Prize and is currently working with TED on a major international project to launch and propagate a Charter for Compassion, created online by the general public and crafted by leading thinkers in Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism, to be signed in the fall of 2009 by a thousand religious and secular leaders. She lives in London.

_______________________________________

From Publishers Weekly This searching, profound comparative history of the three major monotheistic faiths fearlessly illuminates the sociopolitical ground in which religious ideas take root, blossom and mutate. Armstrong, a British broadcaster, commentator on religious affairs.., argues that Judaism, Christianity and Islam each developed the idea of a personal God, which has helped believers to mature as full human beings. Yet Armstrong also acknowledges that the idea of a personal God can be dangerous, encouraging us to judge, condemn and marginalize others. Recognizing this, each of the three monotheisms, in their different ways, developed a mystical tradition grounded in a realization that our human idea of God is merely a symbol of an ineffable reality. To Armstrong, modern, aggressively righteous fundamentalists of all three faiths represent “a retreat from God.” She views as inevitable a move away from the idea of a personal God who behaves like a larger version of ourselves, and welcomes the grouping of believers toward a notion of God that “works for us in the empirical age.”

_______________________________________

My wish: The Charter for Compassion – Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong TED Talk given in 2008

What God is, or isn’t, will continue to morph indefinitely unless…

_______________________________________

Richard Barlow:

‘The whole thing about the messiah is a human construct’

The Divine Principle: Questions to consider about Old Testament figures

How “God’s Day” was established on January 1, 1968

_______________________________________

Divine Principle – Parallels of History

_______________________________________

“… Many Koreans therefore have difficulty understanding and accepting religions that have only one god and emphasize an uncertain and unknowable afterlife rather than the here and now. In the Korean context of things, such religions are anti-life and do not really make sense…” LINK

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Make a Move Just to Stay in the Game (part two)

y’all already know. it’s me. it’s @ichlugebulletsandcornnuts (who probably hates how many mentions she has in her notifs (but that’s showbiz baby))

[part one]

[Part 2: Rather be a Comma than a Full Stop]

for the next couple of hours, parr walks her through some basic translations before letting the girl try a short paragraph by herself. katherine is deep in thought attempting to work out whether this particular word meant “book” or “to throw”, as well as wondering why on earth two such different meanings were assigned to the same word, when parr speaks.

“may i ask you a question?”

“of course,” katherine says politely, looking up from her translation.

“if you’ll forgive me for my curiosity, how long have you and her majesty known each other? you seem to be very close.” parr’s voice is free from judgement or skepticism, merely a natural interest from seeing them interact.

“only a couple of months,” katherine admits with a shrug. “we met the end of september, it’s february now?”

parr gives a mysterious grin.

“what?” katherine asks.

parr gives a gentle laugh, covered by her hand. “nothing, i promise.” katherine narrows her eyes slightly and parr relents. “i’ve known the queen for a while, you know. she always has claimed favorites among her staff, but then they are generally asked to leave by the king himself.” katherine cringes at this. “but it seems she’s taken you, lady katherine.” she smiles. “quite taken indeed.”

katherine frowns slightly, and parr speaks again, apparently worried. “i don’t mean to offend. i think it’s wonderful, actually.”

katherine unconsciously relaxes and she gives parr a small smile. “thank you,” she says, returning to her translations. it doesn’t take her long to finish and parr takes the paper from her, checking it through and making corrections as she goes. she hands the paper back to katherine with a grin.

“excellent work, lady katherine. there were only some small mistakes; you just need to watch out so you don’t mistake a ‘t’ ending for an ‘nt’ ending. overall, a very good first try by yourself.”

katherine grins. she looks the paper over as she shakes out her wrists and cracks her neck.

parr glances at her pocket watch then looks back to katherine.

just as she opens her mouth to speak, lady eleanor walks in, holding a tea tray.

“i was just about to ask about tea time,” parr laughs. “perfect timing.”

eleanor gives a tiny smile and ducks her head. “thank you, lady parr.”

parr is admittedly surprised as she watches katherine fix her tea: very little sugar at all, mostly milk. parr follows suit.

“lady parr?” katherine asks. parr raises her eyebrows and katherine remembers. “sorry, just parr.” the other woman smiles and gestures for her to continue. “can you tell me a bit more about you?”

parr is slightly surprised, but nods. “well, as you know, i’m catherine parr- well, catherine neville, but I can’t say i’ve ever been fond of that name. although i can’t say my first husband’s surname was much better. burgh,” she explains with a dramatic roll of her eyes that makes katherine giggle slightly. “i’m working on a book, currently.”

“what’s it about?” katherine asks curiously. parr pauses for a moment.

“methods of prayer,” she says finally.

katherine wrinkles her nose a bit and looks just above parr’s head in thought. “i’m not much of the religious sort,” she admits. a vision flashes before her eyes - one of tiny katherine howard praying every night to be saved from her horrid life, but no prayers were ever answered. “but it still sounds very interesting,” she continues. “would you let me read it someday?”

parr seems to think the question over in her head. “if i ever finish it, then i’d be happy to let you read it,” she says with a nod. “it... may be best not to mention this book to anybody else, though.”

“why?” katherine asks, confused, and parr sighs.

“it’s not entirely... safe for me to be outspoken in my religious beliefs right now.” she shakes her head slightly. “but let us not dwell on that. why don’t you tell me some things about yourself, lady katherine?”

katherine’s smile fades slightly. “well, um, there’s not too much to tell.” she looks down at the tea saucer in front of her. “i’m katherine seymour, formerly howard. i’m fifteen, hailing from lambeth. my grandmother is the dowager duchess.” she fights to hide the chill down her spine at the thought of that place. “i was brought here to serve jane...her majesty... in september as a lady in waiting, and she just took me on as her ward around six weeks ago.”

parr still looks curious. “you do seem to have a bit of formal education, and i feel i may know your father from a passing meeting, so what was your childhood like?”

“I, um...” katherine shifts awkwardly in her chair. “my mother died when i was five.”

“oh, i’m sorry,” parr says softly. katherine shakes her head.

“it’s okay, I don’t remember much about her.” she misses the pained expression that flits across parr’s face at that. “i, uh, went to a school run my my step-grandmother. we had lessons there, just not enough to teach me everything i need to know.” she decides to stay quiet about what happened for the moment; she likes parr, but she’s only just met her.

parr senses that katherine is holding back, and doesn’t know whether to press on or not. she pretends to have not seen it, then pursues a different line of questioning. “so you learned to read and write?” katherine seems a bit relieved at the change of topic. “what’s your favorite book?”