#and was born in fort gibson.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Dum Spiro Spero

Link to Wattpad

❛While I breathe, I hope.❜ 𝘈𝘯𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶? 𝘞𝘩𝘢𝘵 𝘸𝘰𝘶𝘭𝘥 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘥𝘰 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘭𝘰𝘷𝘦? ❝You were born reaching for your mother's hands, Victim of your father's plans.❞ The son of Hermes and the daughter of Apollo were always enough for each other. What happens when one of them starts yearning for more? ❝To rule the world.❞

✧ Pairing: Luke Castellan x Fem!oc

✧ Warnings: Violence, Major Character Death, possible mentions of substance and/or alcohol abuse, Mild gore, Language, Mature themes.

Any potential triggers will be marked as will any potential mature content!

✧ Status: Ongoing

Prologue

Character Aesthetics

Hannah Dorothea Anatolia Gibson

'I found myself falling before I even noticed I stepped off that ledge.'

19. daughter of apollo. beloved. sunshine and rainy days. credulous. sand by dove cameron

☀︎ Hannah meaning meaning gracious, merciful, one who gives or favoured of god. Named by her father.

☀︎ Dorothea meaning gift from god. Named by Apollo.

☀︎ Anatolia meaning sunrise. Named by Apollo.

☀︎Gibson meaning son of Gilbert. Name of instrument brand Gibson. Father's family name.

The name literally translates to 'the favoured gift of god given at sunrise.'

☀︎⋆.ೃ࿔*:・

Luke Alastor Arlo Castellan

'Funny. I stepped off that same ledge willingly.'

19. son of hermes. amor. harsh winds at sea. excessive wrath. blue by billie eilish.

* Luke meaning luminous or light-giving. Named by his mother.

* Alastor meaning man's defender, avenger or vengeance. Links to his fatal flaw of excessive wrath. Named by Hermes.

* Arlo meaning fortified hill or between two hills. Signifying his stance between two world, mortal vs gods and his choices good vs evil or Hannah vs Kronos. Named by Hermes.

* Castellan meaning governor or warden of a castle/fort. Mother's family name.

☀︎⋆.ೃ࿔*:・

Luke & Hannah

'Our story is woven in the stars.'

the star-crossed lovers. the ill-fated. doomed from the start.

☀︎⋆.ೃ࿔*:・

son of thieves and wind

daughter of sight and sun

doomed to love the other one.

fate has plans of other for them

their story forever condemned.

☀︎⋆.ೃ࿔*:・

#luke castellan smut#luke castellan#lukexoc#daughter of apollo#son of hermes#pjo#percyjackson#percy jackson fic#fanfic#yorspage#yorsfics#yors<3#percy jackon and the olympians#percy jackson

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

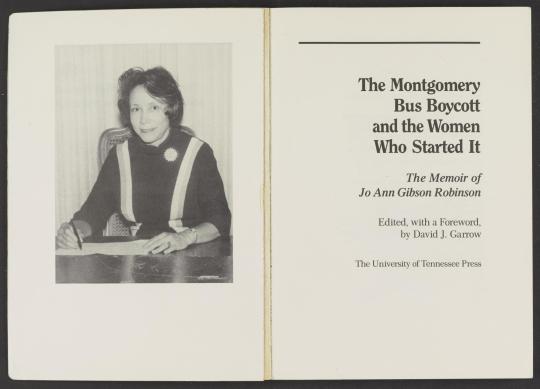

Jo Ann Gibson Robinson ,unsung activist (April 17, 1912 – August 29, 1992) was a civil rights activist and educator in Montgomery, Alabama.Known for initiating the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery, AL, USA

Born near Culloden, Georgia, she was the youngest of twelve children. She attended Fort Valley State College and then became a public school teacher in Macon, where she was married to Wilbur Robinson for a short time. Five years later, she went to Atlanta, where she earned an M.A. in English at Atlanta University. After teaching in Texas she then accepted a position at Alabama State College in Montgomery. It was there she joined the Women's Political Council, which Mary Fair Burks had founded three years earlier. In 1949, Robinson was verbally attacked by a bus driver for sitting in the front "Whites only" section of the bus. Her response to the incident was to attempt to start a protest boycott. But, when she approached her fellow members of the Woman’s Political Council with her story and proposal, she was told that it was “a fact of life in Montgomery.” In late 1950, she succeeded Burks as president of the WPC and helped focus the group's efforts on bus abuses. Robinson was an outspoken critic of the treatment of African-Americans on public transportation. She was also active in the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

The Women's Political Council had made complaints about the bus seating to the Montgomery City Commission and about abusive drivers, and achieved some concessions, including an undertaking that drivers would be courteous and having buses stopping at every corner in black neighborhoods, as they did in European areas. After Brown vs. Board of Education, Robinson had informed the mayor of the city that a boycott would come and then after Rosa Parks arrest, they seized the moment to plan the boycott of the buses in Montgomery.

On Thursday, December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to move from her seat in the African area of the bus she was travelling on to make way for a white passenger who was standing. Mrs. Parks, a civil rights organizer, had intended to instigate a reaction from white citizens and authorities. That night, with Mrs. Parks permission, Mrs. Robinson stayed up mimeographing 52,500 handbills calling for a boycott of the Montgomery bus system. The boycott was initially planned to be for just the following Monday. She passed out the leaflets at a Friday afternoon meeting of AME Zionist clergy among other places and Reverend L. Roy Bennett requested other ministers attend a meeting that Friday night and to urge their congregations to take part in the boycott. Robinson, Reverend Ralph David Abernathy, two of her senior students and other Women's Council members then passed out the handbills to high school students leaving school that afternoon. After the success of the one-day boycott, African citizens decided to continue the boycott and established the Montgomery Improvement Association to focus their efforts. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was elected president. Jo Ann Robinson became a member of this group. She had denied an official position to the Montgomery Improvement Association because of her teaching position at Alabama State. She served on its executive board and edited their newsletter. In order to protect her position at Alabama State College and to protect her colleagues, Robinson purposely stayed out of the limelight even though she worked diligently with the MIA. Robinson and other WPC members also helped sustain the boycott by providing transportation for boy-cotters.

Robinson was the target of several acts of intimidation. In February 1956, a local police officer threw a stone through the window of her house. Then two weeks later, another police officer poured acid on her car. Then the governor of Alabama ordered the state police to guard the houses of the boycott leaders. The boycott lasted over a year because the bus company would not give in to the demands of the protesters. After a student sit-in in early 1960, Robinson and other teachers that had supported the students, resigned their positions at Alabama State College. Robinson left Alabama State College and moved out of Montgomery that year. She taught at Grambling College in Louisiana for one year and then moved to Los Angeles and taught English in the public school system. In Los Angeles she continued to be active in local women's organizations. She taught in the LA schools until she retired from teaching in 1976. Jo Ann Robinson was also a part of the bus boycott and was strongly against discrimination.

#african#kemetic dreams#afrakan#africans#afrakans#brown skin#brownskin#Jo Ann Robinson#alabama state college#macon#fort valley college

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

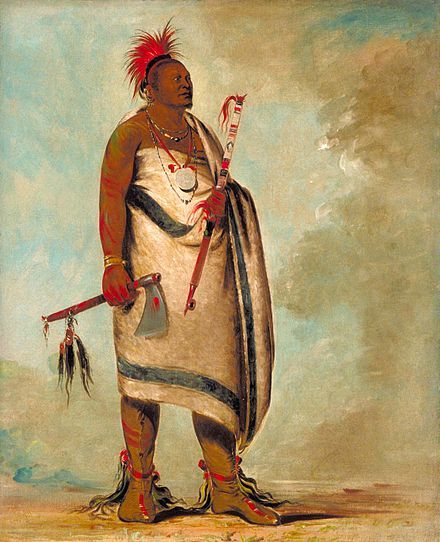

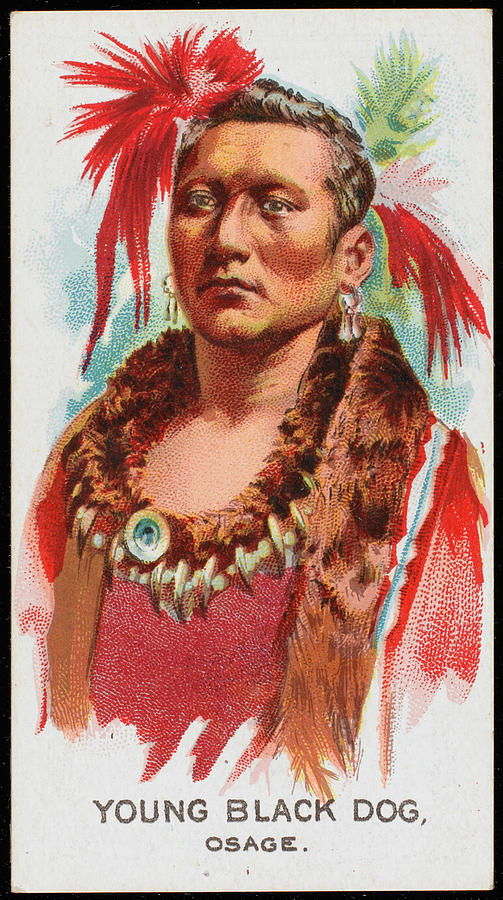

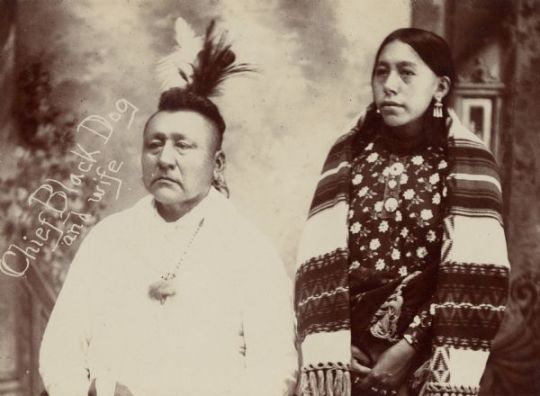

Black Dog (Osage, Manka-Chonka, ca. 1780–1848) was a Chief of the Hunkah band of the Osage Indians that lived in an area around present Baxter Springs, Kansas. In the fall of 1803, the band moved to the village of Pasuga (Big Cedar), present day Claremore, Oklahoma. His towering height was around seven feet tall, his weight some 300 pounds, and he was blind in the left eye ... He took his band on hunts as far away as Santa Fe, then part of Mexico, possibly earning the designation Manka-Chonka in battles with the Comanche. He is credited with engineering a trail known as the Black Dog Trail east of present Baxter Springs, Kansas to the Great Salt Plains in present Alfalfa County, Oklahoma ... On a visit to Fort Gibson in 1834, George Catlin painted Black Dog's picture, giving his name as "Tchong-tas-sab-bee, Black Dog, Second Chief" ... Black Dog is known to have had at least one son, also called Black Dog (1827–1910), who became an Osage chief in 1870, Pictures 2 & 3 Black Dog's only son ...

(20101.9, Frank F. Finney Sr. Collection, OHS).

BLACK DOG (ca. 1780–1848) ... The Osage chief Black Dog was born circa 1780 near St. Louis, Missouri. His village, Pasuga (or Big Cedar), was located at present Claremore, Oklahoma. His original name, Zhin-gawa-ca (or Shinka-Wah-Sa), meant Dark Eagle or Sacred Little One ... He possibly earned the designation Manka-Chonka, or Black Dog, against the Comanche ... At a Fort Gibson meeting during March 1833, he was called Shonkah-Sabe, or Black Horse ... An Osage trail in Kansas and Oklahoma was known as the Black Dog Trail. Engineered by Black Dog, it extended from east of present Baxter Springs, Kansas, to the Great Salt Plains in Alfalfa County, Oklahoma ... Under his leadership a substantial proportion of the Osage hunted west to the Salt Plains and the upper Arkansas River ... It was not uncommon for members of his band to raid, hunt, and trade as far away as Mexico and Santa Fe ...

Portraits (picture 1) of Black Dog were painted by artists George Catlin in 1834 and John Mix Stanley in 1843 ...

Blind in his left eye, he stood around seven feet tall and weighed an estimated three hundred pounds. His only son, also called Black Dog, was born in 1827 and died in 1910. Black Dog was a contemporary of and shared power with chiefs Claremore and Pawhuska. His political control perhaps extended over a third of the tribe. He was on generally friendly terms with U.S. authorities and occasionally ordered his braves to hunt and scout for American troops ...

Black Dog died at the present site of Claremore, Oklahoma, on March 24, 1848.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenora Obituaries: Honoring Community Heritage and Legacy

Kenora Obituaries serve as a profound tribute to the lives of community members who have shaped the town's culture, values, and history. Every story captured in these obituaries provides insight into personal achievements, family legacies, and the rich relationships that bind the town’s social fabric. The recent obituaries of Kenora residents illustrate how individuals have contributed meaningfully to both their families and the community, providing a lasting legacy that continues to inspire. Each life honored showcases the diverse paths taken, each contributing uniquely to Kenora’s legacy.

Celebrating Diverse Life Journeys in Kenora

The town of Kenora sees each resident’s life as a chapter in its collective history. The narratives found in recent obituaries reflect a broad spectrum of life experiences, from those of dedicated professionals to caring family members, each with their own special place in the community. For example, Edythe Mary Gibson, a celebrated writer at the age of 96, exemplified Kenora’s enduring connection to storytelling and tradition. Her renowned column, “Around the Town with Edith,” chronicled local life, bringing people together through a shared appreciation of community stories.

Another notable figure, Kenneth "Ken" Delbert Ames, demonstrated the importance of craftsmanship and community service. As a respected plumber and gas fitter who worked in Kenora his entire life, Ken embodied the values of hard work, resilience, and dedication to serving the town. His contributions remind us of the essential skills that quietly support the town’s daily life.

The Core of Family Ties and Community Support

Kenora obituaries highlight the strength of family connections and their lasting impact on both individual lives and community values. Individuals like Vivian (Vicky) McKay, known for her compassion and commitment to family, reveal how family-oriented values shape personal legacies. Vicky’s journey from Fort Frances to Kenora with her husband and children showcases how family ties create foundational roots in the community.

Similarly, Rowena Miriam Hoppe, a mother of six, exemplified the nurturing and sacrificial spirit vital to building future generations. Her story represents the roles that many women in Kenora have played in strengthening family bonds and fostering a close-knit community. These personal histories remind us that Kenora’s community spirit thrives through generations of love, responsibility, and care.

Contributions to Community Life and Local Initiatives

Many Kenora residents dedicate their lives to improving the town’s quality of life through career paths and community work, leaving a legacy that influences and inspires those around them. Figures like John Meredith “Pete” Bradley, who was remembered for his joy, kindness, and close family bonds, demonstrate how personality traits contribute to Kenora’s collective well-being. His impact, though intangible, is deeply felt by those who knew him, underscoring the role of positive relationships in fostering a sense of belonging and community pride.

Rodney “Hambone” McCammon, known for his humor and warmth, also had a profound effect on the people around him. His lively presence was a reminder of the power of individual character in shaping community spirit. Such examples illustrate that community contributions are not solely about formal achievements but also about the ways in which personal qualities can uplift those around us.

Shifting Perspectives: From Mourning to Celebrating Life

The recent trend in Kenora’s obituaries highlights a shift from traditional mourning practices to celebrations of life, where families and friends come together to honor the deceased in uplifting ways. Instead of solely focusing on loss, these celebrations foster unity and provide a platform to share memories and strengthen bonds. Bill Kyle’s upcoming celebration of life, for instance, will gather loved ones to commemorate his achievements, symbolizing the resilience of community ties and the value of shared remembrance.

Memorial services in Kenora also spotlight the impact of residents’ work on local projects and initiatives. By honoring the contributions of individuals like Bruce Richard Lund, who played a significant role in community projects, these events encourage others to carry on their work. In this way, each life continues to inspire, providing a legacy of community service that endures even after their passing.

Building a Shared Legacy Through Kenora’s Obituaries

Kenora’s obituaries play a critical role in preserving the town’s shared memory, capturing the personal achievements, values, and sacrifices of its residents. By recording these legacies, obituaries contribute to a living history that honors both the past and present. Families use these tributes to ensure their loved ones’ stories are remembered, helping to build a community narrative that fosters unity and resilience.

More than simple announcements of death, Kenora obituaries are a medium through which lives are celebrated and remembered. Each story enriches the town’s identity and serves as a reminder of the enduring bonds between individuals and their community. As Kenora continues to grow and evolve, these memories ensure that the contributions of past residents remain a part of the town’s legacy, guiding future generations.

Conclusion

The Kenora Obituaries are more than commemorative passages; they are an enduring tribute to those who have shaped the community’s heart and soul. Every story told is a piece of Kenora’s collective history, reminding us of the impact that each person, through their unique journey, has left on their family, friends, and town. Through these memories, Kenora’s community is continually strengthened, offering inspiration to those who carry forward its legacy. As new chapters are written, the town’s collective memory grows, preserving the spirit of Kenora for future generations.

0 notes

Text

William Madison McDonald (June 22, 1866 - July 4, 1850) was born in Kaufman County, Texas to former enslaved George McDonald and Flora Scott McDonald. His mother died when he was five, and his father married his second wife, Belle Crouch.

He worked for attorney and rancher Z.T. Adams, who took an interest in his young employee, lecturing him on business and law while he worked. He attended Roger Williams University in Tennessee, with support from Adams. He became principal of the African American high school in Forney, Texas, where his wife Alice Gibson McDonald taught. He remained principal for several years.

He sought wealth and power. In doing so he used three positions—as a politician (Republican), as a businessman (banker), and as a fraternalist (Masons). With this foundation, he led Texas’ Republican Party “Black and Tan” faction for thirty years, a group opposed to the machinations of the “Lily Whites.” His political partnership with wealthy businessman E.H.R. Green provided him with a strong voice in state politics. In 1899 he became Grand Secretary of the Prince Hall Free and Accepted Masons of Texas, a powerful and influential position he held for almost 50 years. He cemented his influence by membership in at least three other fraternal groups. He received voting and financial support from his fraternal brothers (and sisters).

He moved in 1906 to Fort Worth where he was a civic leader and successful businessman. He built his bank, the Fraternal Bank and Trust Company in 1912, with support from the Black fraternities. The bank was successful and well-run, surviving even during the Great Depression. For the last years of his life, he stayed out of politics, let others run the fraternities, and lived a leisurely life. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Text

The first pharmacies in what today is US were stablished on Feb 1st, 1770, by Spanish Governor of Louisiana Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga. Nicknamed "The Peacemaker", he issued the first licenses to the New Orleans' chapter of the time.

He also aided US army in the Independence War of the Colonies:

Unzaga was noted for allowing open trade. During the summer of 1776, he secretly helped Patrick Henry and the Americans by privately delivering five tons of gunpowder from the king's stores to Captain George Gibson and Lieutenant Linn of the Virginia Council of Defense. The gunpowder was moved up the Mississippi under the protection of the flag of Spain, and was used to thwart British plans to capture Fort Pitt in Pennsylvania. Unzaga was the first Spanish official to provide direct military aid to the Continental Army during the American Revolution. After repeated requests from New Orleans merchant Oliver Pollock, Unzaga approved the secret transfer of a load of gunpowder up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers to Fort Pitt, where it arrived in May 1777. Later, additional supplies were shipped from New Orleans to Philadelphia. Pollock provided the vessels for both shipments.

NOTE: the picture Wikipedia has of him is not correct as it portraits someone from the 17th century even if Unzaga was born in the 18th century.

#Pharmacies#Louisiana#Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga#18th century#Spain#Spanish Crown#Spanish History#Patrick Henry#Fort Pitt#Mississippi#Ohio#New Orleans#Philadelphia#American Revolution

1 note

·

View note

Text

Song of the Day: Lee Wiley, "Manhattan"

Jazz chanteuse Lee Wiley was born on this day in 1909. She was born in Fort Gibson, Oklahoma, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation (appropriate for Indigenous People’s Day). This recording of Rodgers & Hart’s “Manhattan” was made in 1951.

youtube

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

strlitmemries replied to your post “wayne’s just what eliot would have been if he stayed home and took...”

LETTERKENNY ELIOT & QUINN AU WHEN

ELIOT’S THE TOUGHEST GUY IN FORT GIBSON QUINN.

#strlitmemries#>> : out of targets // ooc : <<#need you to take about 20% off bud.#actually i think eliot didn't live IN fort gibson.#but near it.#and was born in fort gibson.#yurp.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

LIST OF ACTORS WHO WORKED WITH TOM CRUISE... AND YOU DIDN'T KNOW OR DON'T REMEMBER:

(Illustrative gif, sorry for the poor quality)

James Spader (Endless Love)

Director Robert Altman (Endless Love)

Giancarlo Esposito (Taps)

Sofia Coppola (The Outsiders)

Flea, from the rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers (The Outsiders)

Singer Iggy Pop (The Color of Money)

Forest Whitaker (The Color of Money)

William Baldwin (Born on the Fourth of July)

Stephen Baldwin (Born on the Fourth of July)

Vivica A. Fox (Born on the Fourth of July)

Daniel Baldwin (Born on the Fourth of July)

Holly Marie Combs (Born on the Fourth of July)

Tom Sizemore (Born on the Fourth of July)

Tom Berenger (Born on the Fourth of July)

Margo Martindale (Days of Thunder, The Firm)

Jared Harris (Far and Away)

Paul Sorvino (The Firm)

Dean Norris (The Firm)

Helen McCrory (Interview with the Vampire)

Sam Douglas (Mission: Impossible, Eyes Wide Shut)

Drake Bell (Jerry Maguire)

Eric Stoltz (Jerry Maguire)

Lucy Liu (Jerry Maguire)

Beau Bridges (Jerry Maguire)

Cate Blanchett (Eyes Wide Shut)

Alan Cumming (Eyes Wide Shut)

Patton Oswalt (Magnolia)

Paul F. Tompkins (Magnolia)

Robert Downey Sr. (Magnolia)

Dominic Purcell (Mission: Impossible 2)

Johnny Galecki (Vanilla Sky)

Laura Fraser (Vanilla Sky)

Tommy Lee, from the rock band Motley Crue (Vanilla Sky)

Michael Shannon (Vanilla Sky)

Paul Wesley (Minority Report)

Meredith Monroe (Minority Report)

Scott Wilson (The Last Samurai)

Jason Statham (Collateral)

David Harbour (War of the Worlds)

Amy Ryan (War of the Worlds)

Channing Tatum (War of the Worlds)

Timothy Omundson (Mission: Impossible 3)

Aaron Paul (Mission: Impossible 3)

Bellamy Young (Mission: Impossible 3)

Tyra Banks (Tropic Thunder)

Jennifer Love Hewitt (Tropic Thunder)

Jason Bateman (Tropic Thunder)

Lance Bass (Tropic Thunder)

Alicia Silverstone (Tropic Thunder)

Tobey Maguire (Tropic Thunder, Rock of Ages producer)

Justin Theroux (Tropic Thunder executive producer and screenwriter, Rock of Ages screenwriter)

Gal Gadot (Knight and Day)

Will Forte (Rock of Ages)

Eli Roth (Rock of Ages)

Kevin Cronin, from the rock band Reo Speedwagon (Rock of Ages)

Debbie Gibson (Rock of Ages)

Sebastian Bach (Rock of Ages)

Jason Douglas (Jack Reacher 2)

#tom cruise#textpost#misc#Sofia Coppola#eric stoltz#lucy liu#cate blanchett#Jason Statham#channing tatum#Gal Gadot#tobey maguire#justin theroux

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mysterious Death of a Hollywood Director

This is the tale of a very famous Hollywood mogul and a not-so-famous movie director. In May of 1933 they embarked together on a hunting trip to Canada, but only one of them came back alive. It’s an unusual tale with an uncertain ending, and to the best of my knowledge it’s never been told before.

I. The Mogul

When we consider the factors that enabled the Hollywood studio system to work as well as it did during its peak years, circa 1920 to 1950, we begin with the moguls, those larger-than-life studio chieftains who were the true stars on their respective lots. They were tough, shrewd, vital, and hard working men. Most were Jewish, first- or second-generation immigrants from Europe or Russia; physically on the small side but nonetheless formidable and – no small thing – adaptable. Despite constant evolution in popular culture, technology, and political and economic conditions in their industry and the outside world, most of the moguls who made their way to the top during the silent era held onto their power and wielded it for decades. Their names are still familiar: Zukor, Goldwyn, Mayer, Jack Warner and his brothers, and a few more. And of course, Darryl F. Zanuck. In many ways Zanuck personified the common image of the Hollywood mogul. He was an energetic, cigar-chewing, polo mallet-swinging bantam of a man, largely self-educated, with a keen aptitude for screen storytelling and a well-honed sense of what the public wanted to see. Like Charlie Chaplin he was widely assumed to be Jewish, and also like Chaplin he was not, but in every other respect Zanuck was the very embodiment of the dynamic, supremely confident Hollywood showman.

In the mid-1920s he got a job as a screenwriter at Warner Brothers, at a time when that studio was still something of a podunk operation. The young man succeeded on a grand scale, and was head of production before he was 30 years old. Ironically, the classic Warners house style, i.e. clipped, topical, and earthy, often dark and sometimes grimly funny, as in such iconic films as The Public Enemy, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and 42nd Street, was established not by Jack, Harry, Sam, or Albert Warner, but by Darryl Zanuck, who was the driving force behind those hits and many others from the crucial early talkie period. He played a key role in launching the gangster cycle and a new wave of sassy show biz musicals. At some point during 1932-33, however, Zanuck realized he would never rise above his status as Jack Warner’s right-hand man and run the studio, no matter how successful his projects proved to be, because of two insurmountable obstacles: 1) his name was not Warner, and 2) he was a Gentile. Therefore, in order to achieve complete autonomy, Zanuck concluded that he would have to start his own company.

In mid-April of 1933 he picked a public fight with Jack Warner over a staff salary issue, then abruptly resigned. Next, he turned his attention to setting up a company in partnership with veteran producer Joseph Schenck, who was able to raise sufficient funds to launch the new concern. And then, Zanuck invited several associates from Warner Brothers to accompany him on an extended hunting trip in Canada.

Going into the wilderness and killing wild game, a pastime many Americans still regard as a routine, unremarkable form of recreation, is also of course a conspicuous show of machismo. But in this realm, as with his legendary libido, Zanuck was in a class by himself. He had been an enthusiastic hunter most of his life, dating back to his boyhood in Nebraska. Once he became a big wheel at Warners in the late ’20s he took to organizing high-style duck-hunting expeditions: the young executive and his fellow sportsmen would travel to the appointed location in private railroad cars, staffed by uniformed servants. Heavy drinking on these occasions was not uncommon. (Inevitably, film buffs will recall The Ale & Quail Club from Preston Sturges’ classic comedy The Palm Beach Story, but DFZ and his pals were not cute old character actors, and their bullets were quite real.) Members of Zanuck’s studio entourage were given to understand that participation in these outings was de rigueur if they valued their positions, and expected desirable assignments in the future. Director Michael Curtiz, who had no fondness for hunting, remembered the trips with distaste, and recalled that on one occasion he was nearly shot by a casting director who had no idea how to properly handle a gun.

But ducks were just the beginning. In 1927 Zanuck took his wife Virginia on an African safari. In Kenya Darryl bagged a rhinoceros and posed for a photo with his wife, crouched beside the rhino’s carcass. Virginia, an erstwhile Mack Sennett bathing beauty and former leading lady to Buster Keaton, appears shaken. Her husband looks exhilarated. During this safari Zanuck also killed an elephant. He kept the animal’s four feet in his office on the Warners lot, and used them as ashtrays. If any animal lover dared to express dismay, the Hollywood sportsman would retort: “It was him or me, wasn’t it?” Zanuck made several forays to Canada with his coterie in this period, gunning for grizzly bears. Director William “Wild Bill” Wellman, who was more of an outdoorsman than Curtiz, once went along, but soon became irritated with Zanuck’s bullying. The two men got into a drunken fistfight the night before the hunting had even begun. In the course of the ensuing trip the hunting party was snowbound for three days; Zanuck sprained his ankle while trailing a grizzly; the horse carrying medical supplies vanished; and Wellman got food poisoning. “It was the damnedest trip I’ve ever seen,” the director said later, “but Zanuck loved it.”

Now that Zanuck had severed his ties with the Warner clan and was on the verge of a new professional adventure, a trip to Canada with a few trusted associates would be just the ticket. This time the destination would be a hunting ground on the banks of the Canoe River, a tributary of the Columbia River, 102 miles north of Revelstoke, British Columbia, a city about 400 miles east of Vancouver. There, in a remote scenic area far from any paved roads, telephones, or other niceties of modern life, the men could discuss Zanuck’s new production company and, presumably, their own potential roles in it. Present on the expedition were screenwriter Sam Engel, director Ray Enright, 42nd Street director Lloyd Bacon, producer (and former silent film comedian) Raymond Griffith, and director John G. Adolfi, best known at the time for his work with English actor George Arliss. Adolfi, who was around 50 years old and seemingly in good health, would not return.

II. The Director

Even dedicated film buffs may draw a blank when the name John Adolfi is mentioned. Although he directed more than eighty films over a twenty-year period beginning in 1913, most of those films are now lost. He worked in every genre, with top stars, and made a successful transition from silent cinema to talkies. He seems to have been a well-respected but self-effacing man, seldom profiled in the press.

According to his tombstone Adolfi was born in New York City in 1881, but the exact date of his birth is one of several mysteries about his life. His father, Gustav Adolfi, was a popular stage comedian and singer who emigrated to the U.S. from Germany in 1879. Gustav performed primarily in New York and Philadelphia, and was known for such roles as Frosch the Jailer in Strauss’ Die Fledermaus. But he was a troubled man, said to be a compulsive gambler, and after his wife Jennie died (possibly of scarlet fever) it appears his life fell apart. Gustav’s singing voice gave out, and then he died suddenly in Philadelphia in October 1890, leaving John and his siblings orphaned. (An obituary in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent reported that Gustav suffered a stroke, but family legend suggests he may have committed suicide.) After a difficult period John followed in his father’s footsteps and launched a stage career, and was soon working opposite such luminaries of the day as Ethel Barrymore and Dustin Farnum. Early in the new century the young actor wed Pennsylvania native Florence Crawford; the marriage would last until his death.

When the cinema was still in its infancy stage performers tended to regard movie work as slumming, but for whatever reason John Adolfi took the plunge. He made his debut before the cameras around 1907, probably at the Vitagraph Studio in Brooklyn. There he appeared as Tybalt in J. Stuart Blackton’s 1908 Romeo and Juliet , with Paul Panzer and Florence Lawrence in the title roles. He worked at the Edison Studio for director Edwin S. Porter, and at Biograph in a 1908 short called The Kentuckian which also featured two other stage veterans, D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett. Most of Adolfi’s work as a screen actor was for the Éclair Studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, the first film capital. The bulk of this company’s output was destroyed in a vault fire, but a 1912 adaptation of Robin Hood in which Adolfi appeared survives. That same year he also appeared in a famous docu-drama, as we would call it, Saved from the Titanic. This ten-minute short premiered less than a month after the Titanic disaster, and featured actress Dorothy Gibson, who actually survived the voyage, re-enacting her experience while wearing the same clothes she wore in the lifeboat. (This film, unfortunately, is among the missing.) After appearing in dozens of movies Adolfi moved behind the camera.

Much of his early work as a director was for a Los Angeles-based studio called Majestic, where he made crime dramas, Westerns, and comedies, films with titles like Texas Bill’s Last Ride and The Stolen Radium. In 1914 the company had a new supervisor: D. W. Griffith, now the top director in the business, who had just departed Biograph. Adolfi was one of the few Majestic staff directors who kept his job under the new regime. A profile in the February 1915 issue of Photoplay describes him as “a tallish, good-looking man, well-knit and vigorous, dark-haired and determined; his mouth and chin suggest that their owner expects (and intends) to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better.” It was also reported that Adolfi had developed something of a following as an actor, but that he dropped out of the public eye when he became a director. Presumably, that’s what he wanted.

Adolfi left Majestic after three years, worked at Fox Films for a time as a staff director, then freelanced. During the remainder of the silent era he guided some of the screen’s legendary leading ladies: Annette Kellerman (Queen of the Sea, 1918), Marion Davies (The Burden of Proof, 1918), Mae Marsh (The Little ‘Fraid Lady, 1920), Betty Blythe (The Darling of the Rich, 1922), and Clara Bow (The Scarlet West, 1925). Not one of these films survives. A profile published in the New York World-Telegram during his stint at Fox reported that Adolfi was well-liked by his employees. He was “reticent when the conversation turned toward himself, but frank and outspoken when it concerned his work. Mr. Adolfi is not only a director who is skilled in the technique of his craft; he is also a deep student of human nature.” Asked how he felt about the cinema’s potential, he replied, with unconscious irony, “it is bound to live forever.”

III. The Talkies

In spring of 1927 Adolfi was offered a job at Warner Brothers. His debut feature for the studio What Happened to Father? (now lost) was a success, or enough of one anyway to secure him a professional foothold, and he worked primarily at WB thereafter. Thus he was fortuitously well-positioned for the talkie revolution, for although talking pictures were not invented at the studio it was Sam Warner and his brothers, more than anyone else, who sold an initially skeptical public on the new medium. After Adolfi had proven himself with three talkie features Darryl Zanuck handed him an expensive, prestige assignment, a lavish all-star revue entitled The Show of Shows which featured every Warners star from John Barrymore to Rin-Tin-Tin.

Other important assignments followed. In March of 1930 a crime melodrama called Penny Arcade opened on Broadway. It was not a success, but when Al Jolson saw it he sensed that the story had screen potential. He purchased the film rights at a bargain rate and then re-sold the property to his home studio, Warner Brothers. Adolfi was chosen to direct, but was doubtless surprised to learn that Jolson had insisted that two of the actors from the Broadway production repeat their performances before the cameras. One of the pair, Joan Blondell, had already appeared in three Vitaphone shorts to good effect, but the other, James Cagney, had never acted in a movie. Any doubts about Jolson’s instincts were quickly dispelled. Rushes of the first scenes featuring the newcomers so impressed studio brass that both were signed to five-year contracts. While Adolfi can’t be credited with discovering the duo, the film itself, re-christened Sinners’ Holiday,remains his strongest surviving claim to fame: he guided Jimmy Cagney’s screen debut.

At this point the director formed a professional relationship that would shape the rest of his career. George Arliss was a veteran stage actor who went into the movies and unexpectedly became a top box office draw. He was, frankly, an unlikely candidate for screen stardom. Already past sixty when talkies arrived, Arliss was a short, dignified man who resembled a benevolent gargoyle. But he was also a journeyman actor, a seasoned professional who knew how to command attention with a sudden sharp word or a raised eyebrow. Like Helen Hayes he was valued in Hollywood as a performer of unblemished reputation who lent the raffish film industry a touch of Class, in every sense of the word.

In 1929 Arliss appeared in a talkie version of Disraeli, a role he had played many times on stage, and became the first Englishman to take home an Academy Award for Best Actor. Thereafter he was known for stately portrayals of History’s Great Men, such as Voltaire and Alexander Hamilton, as well as fictional kings, cardinals, and other official personages. The old gentleman formed a close alliance with Darryl Zanuck, whom he admired, and was in turn granted privileges highly unusual for any actor at the time. Arliss had final approval of his scripts and authority over casting. He was also granted the right to rehearse his selected actors for two weeks before filming began. All that was left for the film’s director to do, it would seem, would be to faithfully record what his star wanted. Not many directors would accept this arrangement, but John Adolfi, who according to Photoplay “was determined to have his own way unless he is convinced that the other fellow’s is better,” clearly had no problem with it. His first film with Arliss was The Millionaire, released in May 1931; and in the two years that followed Adolfi directed eight more features, six of which were Arliss vehicles. He had found his niche in Hollywood.

One of Adolfi’s last jobs sans Arliss was a B-picture called Central Park, which reunited the director with Joan Blondell. It’s a snappy, topical, crazy quilt of a movie that packs a lot of incident into a 58-minute running time. Central Park was something of a sleeper that earned its director positive critical notices, and must have afforded him a lively holiday from those polite period pieces for the exacting Mr. Arliss.

In spring of 1933, after completing work on the Arliss vehicle Voltaire, Adolfi accompanied Darryl Zanuck and his entourage to British Columbia to hunt bears. Arliss intended to follow Zanuck to his new company, while Adolfi in turn surely expected to follow the star and continue their collaboration. Things didn’t work out that way.

IV. The Hunting Trip

It’s unclear how long the men were hunting before tragedy struck. On Sunday, May 14th, newspapers reported that film director John G. Adolfi had died the previous week – either on Wednesday or Thursday, depending on which paper one consults – at a hunting camp near the Canoe River. All accounts give the cause of death as a cerebral hemorrhage. According to the New York Herald-Tribune the news was conveyed in a long-distance phone call from Darryl Zanuck to screenwriter Lucien Hubbard in Los Angeles. Hubbard subsequently informed the press. The N.Y. Times reported that the entire hunting party (Zanuck, Engel, Enright, Bacon, and Griffith) accompanied Adolfi’s remains in a motorboat down the Columbia River to Revelstoke. From there the body was sent to Vancouver, B.C., where it was cremated. Write-ups of Adolfi’s career were brief, and tended to emphasize his work with George Arliss, though his recent success Central Park was widely noted. John’s widow Florence was mentioned in the Philadelphia City News obituary but otherwise seems to have been ignored; the couple had no children.

V. The Aftermath

Darryl F. Zanuck went on to found Twentieth Century Pictures, a name suggested by his hunting companion Sam Engel. One of the company’s biggest hits in its first year of operation was The House of Rothschild, starring George Arliss and directed by Alfred Werker. The venerable actor returned to England not long afterwards and retired from filmmaking in 1937. In his second book of memoirs, published three years later, Arliss devotes several pages of warm praise to Zanuck, but refers only fleetingly to the man who directed seven of his films, John Adolfi, and misspells his name.

In 1935 Zanuck merged his Twentieth Century Pictures with Fox Films, and created one of the most successful companies in Hollywood history. He would go on to produce many award-winning classics, including The Grapes of Wrath, Laura, and All About Eve. Zanuck’s trusted associates at Twentieth-Century Fox in the company’s best years included Sam Engel, Raymond Griffith, and Lloyd Bacon, all survivors of the Revelstoke trip. Personal difficulties and vast changes in the film industry began to affect Zanuck’s career in the 1950s. He left the U.S. for Europe but continued to make films, and sporadically managed to exercise control over the company he founded. He died in 1979.

In 1984 a onetime screenwriter and film critic named Leonard Mosley, who had known Zanuck slightly, published a biography entitled Zanuck: The Rise and Fall of Hollywood’s Last Tycoon. Aside from his movie reviews most of Mosley’s published work concerned military matters, specifically pertaining to the Second War World. His Zanuck bio reveals a grasp of film history that is shaky at times, for the book has a number of obvious errors. Nevertheless, it was written with the cooperation of Darryl’s son Richard, his widow Virginia, and many of the mogul’s close associates, so whatever its errors in chronology or studio data the anecdotes concerning Zanuck’s personal and professional activities are unquestionably well-sourced.

When Mosley’s narrative reaches May 1933, the point when Zanuck is on the verge of founding his new company, we’re told that he and several associates decided to go on a hunting trip to Alaska. The location is not correct, but chronologically – and in one other, unmistakable respect – there can be no doubt that this refers to the Revelstoke trip. From Mosley’s book:

“There is a mystery about this trip, and no perusal of Zanuck’s papers or those of his former associates seems to elucidate it,” he writes. “Something happened that changed his whole attitude towards hunting. All that can be gathered from the thin stories that are still gossiped around was that the hunting party went on the track of a polar bear somewhere in the Alaskan wilderness [sic], and when the vital moment came it was Zanuck who stepped out to shoot down the charging, furious animal. His bullet, it is said, found its mark all right, but it did not kill. The polar bear came on, and Zanuck stood his ground, pumping away with his rifle. Only this time it was not ‘him or me,’ but ‘him’ and someone else. The wounded and enraged bear, still alive and still charging, swerved around Zanuck and swiped with his great paw at one of the men standing behind him – and only after it had killed this other man did it fall at last into the snow, and die itself. That’s the story, and no one seems to be able to confirm it nor remember the name of the man who died. The only certain thing is that when Zanuck came back, he announced to Virginia that he had given up hunting. And he never went out and shot a wild animal again, not even a jackrabbit for his supper.”

VI. The Coda

Was John Adolfi killed by a bear? It certainly seems possible, but if so, why didn’t the men in the hunting party simply report the truth? Even if their boss was indirectly responsible, having fired the shots that caused the bear to charge, he couldn’t be blamed for the actions of a dying animal. But it’s also possible the event unfolded like a recent tragedy on the Montana-Idaho border. There, in September 2011, two men named Ty Bell and Steve Stevenson were on a hunting trip. Bell shot what he believed was a black bear. When the bear, a grizzly, attacked Stevenson, Bell fired again – and killed both the bear and his friend.

That seems to be the more likely scenario. If Zanuck fired at the wounded bear, in an attempt to save Adolfi, and killed both bear and man instead, it would perhaps explain a hastily contrived false story. It would most definitely explain the prompt cremation of Adolfi’s body in Vancouver. Back in Hollywood Joe Schenck was busy raising money, and lots of it, to launch Zanuck’s new company. Any unpleasant information about the new company’s chief – certainly anything suggestive of manslaughter – could jeopardize the deal. A man hit with a cerebral hemorrhage in the prime of life is a tragedy of natural causes, but a man sprayed with bullets in a shooting, accidental or not, is something else again. That goes double if alcohol was involved, as it reportedly was on Zanuck’s earlier hunting trips.

Of course, it’s also possible that Adolfi did indeed suffer a cerebral hemorrhage. Like his father.

John G. Adolfi is a Hollywood ghost. Most of his works are lost, and his name is forgotten. (Even George Arliss couldn’t be bothered to spell it correctly.) Every now and then TCM will program one of the Arliss vehicles, or Sinners’ Holiday. Not long ago they showed Adolfi’s fascinating B-picture Central Park, that slam-bang souvenir of the early Depression years in which several plot strands are deftly inter-twined. One of the subplots involves a mentally ill man, a former zoo-keeper who escapes from an asylum and returns to the place where he used to work, the Central Park Zoo. He has a score to settle with an old nemesis, an ex-colleague who tends the big cats. As the story approaches its climax, the escaped lunatic deliberately drags his enemy into the cage of a dangerous lion and leaves him there. In the subsequent, harrowing scene, difficult to watch, the lion attacks and practically kills the poor bastard.

by William Charles Morrow

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

My sources for this article, in addition to the Mosley biography cited in the text, include Stephen M. Silverman’s The Fox That Got Away: The Last Days of the Zanuck Dynasty at Twentieth-Century Fox (1988), and Marlys J. Harris’s The Zanucks of Hollywood: The Dark Legacy of an American Dynasty (1989). For material on John Adolfi I made extensive use of the files of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Special thanks to James Bigwood for his prodigious research on the Adolfi family genealogy, and to Mary Maler, John Adolfi’s great-niece, for information she provided on her family.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This Indian Country: American Indian Activists and the Place They Made by Frederick Hoxie (2012)

Frederick E. Hoxie, one of our most prominent and celebrated academic historians of Native American history, has for years asked his undergraduate students at the beginning of each semester to write down the names of three American Indians. Almost without exception, year after year, the names are Geronimo, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The general conclusion is inescapable: Most Americans instinctively view Indians as people of the past who occupy a position outside the central narrative of American history. These three individuals were warriors, men who fought violently against American expansion, lost, and died. It's taken as given that Native history has no particular relationship to what is conventionally presented as the story of America. Indians had a history too; but theirs was short and sad, and it ended a long time ago.In This Indian Country, Hoxie has created a bold and sweeping counter-narrative to our conventional understanding. Native American history, he argues, is also a story of political activism, its victories hard-won in courts and campaigns rather than on the battlefield. For more than two hundred years, Indian activists—some famous, many unknown beyond their own communities—have sought to bridge the distance between indigenous cultures and the republican democracy of the United States through legal and political debate. Over time their struggle defined a new language of "Indian rights" and created a vision of American Indian identity. In the process, they entered a dialogue with other activist movements, from African American civil rights to women's rights and other progressive organizations.Hoxie weaves a powerful narrative that connects the individual to the tribe, the tribe to the nation, and the nation to broader historical processes. He asks readers to think deeply about how a country based on the values of liberty and equality managed to adapt to the complex cultural and political demands of people who refused to be overrun or ignored. As we grapple with contemporary challenges to national institutions, from inside and outside our borders, and as we reflect on the array of shifting national and cultural identities across the globe, This Indian Country provides a context and a language for understanding our present dilemmas.

Image 1

15: My informal quiz is intended to prod students to look beneath the surface of the popular beliefs that define Native people as exotic and irrelevant. I also ask students to consider why it is that Americans so easily accept the romantic stereotype of Indians as heroic warriors and princesses? Why don’t we demand a richer, three-dimensional story? I pose a Native American version of the question the African American writer James Baldwin often asked white audiences a generation ago: “Why do you need a nigger?” My question is the same: Why do Americans need “Indians”—brave, exotic, and dead—as major figures in national culture?

17: This book counters that preference by presenting portraits of American Indians who neither physically resisted, nor surrendered to, the expanding continental empire that became the United States. The men and women portrayed here were born within the boundaries of the United States, rose to positions of community leadership, and decided to enter the nation’s political arena—as lawyers, lobbyists, agitators, and writers—to defend their communities. They argued that Native people occupied a distinct place inside the borders of the United States and deserved special recognition from the central government. Undaunted by their adversary’s military power, these activists employed legal reasoning, political pressure, and philosophical arguments to wage a continuous campaign on behalf of Indian autonomy, freedom, and survival. Some were homegrown activists whose focus was on protecting their local homelands; others had wider ambitions for the reform of national policies. All sought to overcome the predicament of political powerlessness and find peaceful resolutions for their complaints. They struggled to create a long-term relationship with the United States that would enable Native people to live as members of both particular indigenous communities and a large, democratic nation.

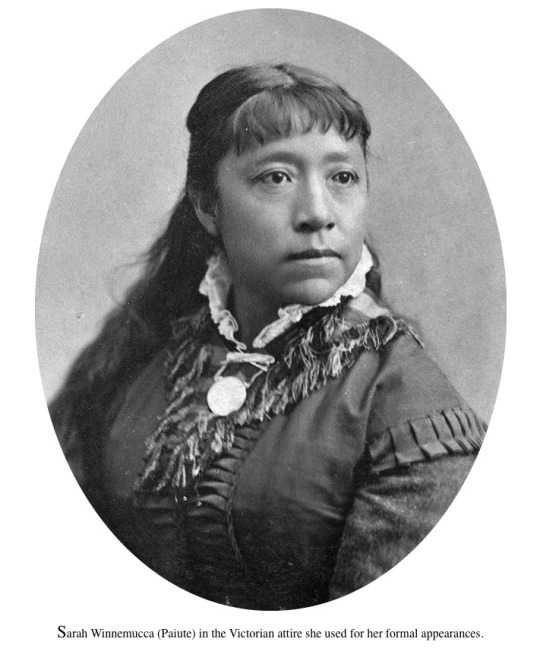

The story of these activists crosses several centuries. It opens in the waning days of the American Revolution, as negotiators in Paris set geographical boundaries for the new nation that ignored Indian nations that had fought in the conflict and had been recognized previously in international diplomacy. Native activists take center stage in the 1820s, when nationalistic U.S. leaders abandoned an earlier diplomatic tradition and pressed Indian leaders to surrender their homes to American settlers. The Choctaw James McDonald, the first Indian in the United States to be trained as a lawyer, is the protagonist of chapter two. McDonald became his tribe’s legal adviser and drew on American political ideals to defend Indian rights, thereby laying the foundation for future claims against the United States.A generation after McDonald, the Cherokee leader William Potter Ross developed and widened the young Choctaw’s arguments. During the middle decades of the nineteenth century he traveled among Indian tribes in the West as well as to Washington, D.C., to recruit other Native leaders to defend tribal sovereignty. Among those who followed in Ross’s wake were Sarah Winnemucca, a Nevada Paiute who in the 1880s became a nationally famous writer, lecturer, and lobbyist, and a group of remarkable Minnesota Ojibwe tribal leaders who battled both at home and in Washington, D.C., to preserve their tiny community on the shores of Mille Lacs Lake.In the twentieth century the leading activists were often polished professionals like Thomas Sloan, an Omaha Indian who became an attorney and established a legal practice in Washington, D.C. The first Indian to argue a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, Sloan helped found the Society of American Indians in 1911 (serving as its first president) and encouraged other community leaders to create similar networks of support. In the 1930s, when Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal offered those leaders opportunities to speak out in defense of their tribes, these networks brought forth tribal advocates such as the Seneca Alice Jemison and the Crow leader Robert Yellowtail, as well as a new generation of intellectuals and thinkers, among them the Salish writer and reformer D’Arcy McNickle and the visionary scholar Vine Deloria, Jr., who by the time of his death in 2005 had become the leading proponent of indigenous cultures and tribal rights in the United States.

..

Vocal opposition to Indian landholding in Mississippi began in 1803, after Napoleon had suddenly decided to sell the entire territory to the Americans. The French emperor’s decision immediately transformed the Choctaw homeland from a distant border area to an inland province that boasted hundreds of miles of frontage on a river that was destined to become the nation’s central highway.15 Secure borders and the lure of plantation agriculture triggered a surge of settlement. The American population in the region doubled between 1810 and 1820 and then doubled again by 1830. New towns clustered along the east bank of the Mississippi as well as on the lower reaches of the Tombigbee River, two hundred miles to the east.The American immigrants were soon calling for the creation of two territorial governments in the area. Congress had first organized Mississippi Territory in 1798 as a hundred-mile-wide swath of unsurveyed land hugging the east bank of the great river and then in 1803, had expanded its borders so that it stretched south from Tennessee to the Gulf. Finally, in 1817, the region took its modern shape when the Tombigbee settlements became the Alabama Territory, Mississippi’s eastern neighbor.Events on America’s northwestern frontier echoed those along the Gulf. Secure borders, a surging settler population, and aggressive local leaders encouraged the rapid organization of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois into territories and states during Jefferson’s presidency. (Ohio became a state in 1803; Indiana in 1816; Illinois in 1818.) Jefferson championed both traditional Indian diplomacy and westward expansion. He understood the value of traditional diplomacy, but he also understood the rising power of western politicians and was far more likely to accommodate them.In 1808 Jefferson supported a major purchase of Choctaw land. He noted that while it was “desirable that the United States should obtain from the native population the entire left (east) bank of the Mississippi,” federal authorities were also determined “to obliterate from the Indian mind an impression . . . that we are constantly forming designs on their lands.” The Choctaws’ current debt of more than forty-six thousand dollars, he explained, provided a solution to this dilemma. Owing to “the pressure of their own convenience,” Jefferson reported, the Choctaws themselves had initiated this sale of five million acres of their land. He wrote that he welcomed this “consolidation of the Mississippi Territory,” and the Senate quickly ratified the agreement.16

...

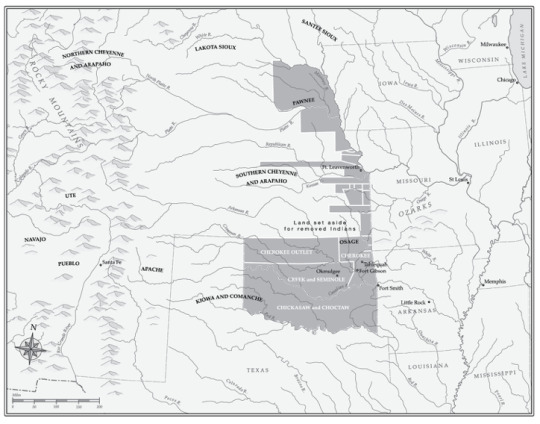

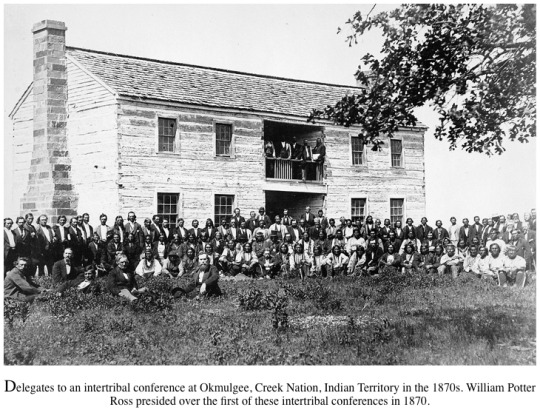

95: Leaders of the removed tribes were quick to promote the idea of multitribal “international councils” aimed at promoting peaceful relations among the tribes in Indian Territory and the surrounding region. These councils grew out of a tradition of peace conferences that U.S. officials had organized prior to removal to reduce tensions between western tribes (particularly the Osages, Pawnees, Kiowas, and Comanches) and the eastern Indians who had begun to migrate voluntarily to the West early in the century. Fort Gibson, erected in 1822 along the Arkansas River at a spot near the future site of the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah, had been the scene for several of these gatherings. One such meeting in 1834 involved more than a dozen tribes (including recently arrived Delawares and Senecas from the Midwest) that pledged friendship to one another and agreed to meet again to conclude a formal treaty. The 1835 Camp Holmes treaty, negotiated on the prairies west of Fort Gibson, fulfilled that goal. It established peaceful relations between the eastern tribes such as the Cherokees, Choctaws, and Creeks, and local groups such as the Wichitas and Osages. A second gathering the following year extended the Camp Holmes agreement to the Kiowas and Kiowa-Apaches.15In the 1840s the Cherokee tribal government, along with the governments of neighboring groups, began hosting their own intertribal meetings. They took this step both because they were eager to maintain good relations with the powerful tribes that had previously occupied their new homelands—particularly the Osages, Kiowas, and Comanches—and because they were increasingly conscious of threats to their borders. To the south, the new Republic of Texas, dominated by slaveholders, seemed determined to remove its resident tribes and create a homogeneous, independent settler nation on the model of the United States. The Cherokees had little interest in antagonizing these aggressive neighbors, many of whom were recent arrivals from Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Tribal leaders in Tahlequah were also aware that Mexican officials to the west, still resentful of the Texans’ recent success in their war of independence, were eager to form alliances with Comanches and other groups who had traditionally raided agricultural communities along the Arkansas River. To the north, resettled tribes from the American Midwest—particularly Delawares, Shawnees, Potawatomis, and Wyandots—were making new homes on the Missouri frontier. The disruptions accompanying their arrival triggered yet another round of retaliation and resentment among indigenous groups.16Large intertribal gatherings began in 1843. In June of that year more than three thousand representatives of twenty-two tribes gathered at Tahlequah in response to invitations sent out by John Ross and Roly McIntosh, the chief of the Creeks. For four weeks the delegates made camp across a two-mile-wide prairie and participated in round dances, ball games, and parades. William Potter Ross, barely a year removed from his Princeton graduation, was among them.When the formal sessions began, Chief John Ross reminded the delegates of the serious work before them. “Brothers,” he cried, “it is for renewing in the West the ancient talk of our forefathers, and of perpetuating forever the old pipe of peace . . . and of adopting such international laws as may redress the wrongs done by the people of our respective tribes to each other that you have been invited to attend the present council.” In addition to securing pledges of peace from all who attended, Ross won approval for eight written resolutions that established rules of conduct and included the declaration “No nation party to this compact shall without the consent of all the other parties, cede or in any manner alienate to the United States any part of their present territory.”17One white observer predicted that the 1843 gathering would “disperse without having done anything,” but the resolution regarding land cessions was a clear signal that the men who had been victims of removal had a serious purpose. They wanted to forge an alliance that could hold their enemies at bay.18 Often ignored by outsiders, these gatherings continued throughout the coming decade.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venus Ebony Starr Williams (born June 17, 1980) is a professional tennis player. A former world #1, she is generally regarded as one of the all-time greats of women’s tennis and, along with younger sister Serena Williams, is credited with ushering in a new era of power and athleticism on the women’s professional tennis tour.

She has been ranked world #1 by the Women’s Tennis Association on three occasions, for a total of 11 weeks. The first African American woman to do so in the Open Era, and the second all-time since Althea Gibson. Her seven Grand Slam singles titles are tied for 12th on the all-time list, and 8th on the Open Era list, more than any other active female player except her sister. She has reached the 16 Grand Slam finals. She has won 14 Grand Slam Women’s doubles titles, all with Serena; the pair is unbeaten in the Grand Slam doubles finals. She has two Mixed Doubles titles. Her five Wimbledon singles titles tie her with two other women for eighth place on the all-time list but give her sole possession of #4 on the Open Era List. From the 2000 Wimbledon Championships to the 2001 US Open, she won four of the six Grand Slam singles tournaments in that span. She extended her record as the all-time leader, male or female, in Grand Slams played, with 85. With her run to the Wimbledon singles final, she broke the record for the longest time between her first and most recent Grand Slam singles finals appearances.

She has won four Olympic gold medals, one in singles and three in women’s doubles, along with a silver medal in mixed doubles, pulling even with the most Olympic medals won by a male or female tennis player. She is the only tennis player to have won a medal at four Olympic Games.

She received her AA in Fashion Design from the Art Institute of Fort Lauderdale. She received a BS in Business Administration from Indiana University East.

She was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Link

Harold Newton did something that took guts.

An African American artist from Georgia, Newton in 1955 walked through the front door of a well-known white artist’s home in Fort Pierce, Florida, to ask A. E. Backus for advice.

“Backus had a reputation here in town for being inclusive and open to people no matter their gender, no matter their beliefs, no matter their race,” said J. Marshall Adams, Executive Director of the A.E. Backus Museum and Gallery in Fort Pierce. “Backus was very encouraging of his work, gave him critiques, gave him demonstrations, gave him art supplies to help encourage him.”

Newton soaked up everything Backus taught him.

Selling paintings along the highway

But Newton had one more hurdle to overcome if he wanted to sell his own landscape paintings.

“He couldn’t set up his own gallery, his own space in those segregated times and attract white clientele to a black studio so he had to figure out a way to get his art to his clients, to his customers,” Adams said.

Newton's solution: sell his paintings out of his car along U.S. 1. That method spread and was adopted by more than two dozen artists in the area, leading to more than 200,000 paintings and a vibrant African American art scene up and down the Treasure Coast. The artists were later given the name: Highwaymen.

Alfred Hair wasn't the first Highwaymen artist, but he was seen as the African American art movement's charismatic leader whose hustle to sell art out of the trunk of his car led to a successful career before his life was cut short when he was shot and killed at a local hangout in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Historical and museum photos of Florida's Highwaymen Artists

Alfred Hair wasn't the first Highwaymen artist, but he was seen as the African American art movement's charismatic leader whose hustle to sell art out of the trunk of his car led to a successful career before his life was cut short when he was shot and killed at a local hangout in Fort Pierce, Florida.1 of 47 Highwaymen artist Al "Blood" Black with one of his paintings in 2014.

Highwaymen artist Curtis Arnett with Attorney General Pam Bondi, left, and curator Jeanna Brunson at the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee in 2011.

Fort Pierce Highwaymen Artist James Gibson brings one of his paintings into the Sunrise Theater to be hung in preparation for the 2007 Highwaymen Florida Artist Hall of Fame Artist Award Celebration held in November 2007.

R.L. Lewis standing in front of his Highwaymen art in 2008.

Mary Ann Carroll, the only woman of the 26 Highwaymen artists in the Florida Artists Hall of Fame, poses for a photo in her garage studio at her home on Oct. 7, 2014, in Fort Pierce. Vero Beach painter Ray McLendon shares a laugh with fifth-grade students on March 2, 2017, at Beachland Elementary School as he signs autographs after giving a talk about Florida Highwaymen art. Florida Highwaymen painter, R. L. Lewis puts finishing touches on painting while attending the Tallahassee Museum's (Jr. Museum) annual Market Days fund raiser held at the North Florida Fairgrounds in 2006.

Highwaymen artist James Gibson at the Tallahassee Museum of History and Natural Science's annual Market Days fund raiser at the Leon County Fairgrounds in 2007.

Highwaymen artist R.L. Lewis painting at the Tallahassee Museum of History and Natural Science's annual Market Days fund raiser at the Leon County Fairgrounds in 2007.

A. E. "Bean" Backus working on one of his paintings sometime in the 1980s.

Robert Butler, Highwayman Artist, working on a painting at the Old Capitol - Tallahassee, Florida, in 2006.

Each year the A.E. Backus Museum in Fort Pierce holds an exhibit celebrating the works of the Florida Highwaymen artists. Backus is credited for giving lessons to Harold Newton and Alfred Hair, two original Florida Highwaymen artists. The 2020 exhibit looked at the art of the Hair, who was considered the charismatic leader of the African American art movement in the area.

The A.E. Backus Museum in Fort Pierce celebrates the work and life of one of the great early Florida landscape artists. Backus also is credited for giving lessons to Harold Newton and Alfred Hair, two original Florida Highwaymen artists.

Doretha Hair Truesdell, widow of original Florida Highwaymen artist Alfred Hair, with Marshall Adams, the executive director of the A.E. Backus Museum, in Fort Pierce. Alfred Hair was considered the charismatic leader of the African American group of artists from Fort Pierce and the surrounding areas. The Backus museum has a permanent display of Highwaymen art.

The Florida Highwaymen were a group of African American artists, generally from Fort Pierce and the surrounding areas, who drove up and down U.S. 1 selling the landscape art during the 1950s and 60s.

The A.E. Backus Museum in Fort Pierce has a permanent display of Highwaymen art, and each January into February, expands that collection to encompass much of the museum. This is part of the expanded 2020 exhibit called "Driving Force."

The story of Alfred Hair

One of the artists considered to be the scene's leader was Alfred Hair. When Hair was 14 years old, he, like Newton, fell into Backus' orbit.

Hair went to the nearby segregated school in Fort Pierce — Lincoln Park Academy. It was Hair’s teacher who suggested Backus take him under his wing.

Backus taught Hair how to paint landscapes and how to make frames. Hair started to believe he could turn painting into a career, something unheard of for blacks of the time.

"The only jobs you could get was working in the fields, that was your job, in the orange groves," said Hair’s widow, Doretha Hair Truesdell. "Alfred didn’t see himself doing that. He said painting is what I’m going to do. This is my job. This is my employment."

Doretha Hair Truesdell, widow of original Florida Highwaymen artist Alfred Hair, with Marshall Adams, the executive director of the A.E. Backus Museum, in Fort Pierce. Alfred Hair was considered the charismatic leader of the African American group of artists from Fort Pierce and the surrounding areas. The Backus museum has a permanent display of Highwaymen art.

As Hair grew in the industry, he knew he would have to do things differently from his white mentor, who could set up in galleries and share his paintings with mass audiences.

So Hair came up with his own business model.

A new business model

“What he could do is lean into his talents, and one of those talents was painting fast,” Adams said. “If he could learn how to paint faster and paint more volume he would have more to sell — he would sell them for a less expensive price point than an established artist — but at the end of the day make as much money.”

Soon, Hair took a page from Newton’s playbook. He began driving up and down the highway selling his paintings.

It worked. During the early part of the 1960s Hair, and many other artists with a similar painting style, thrived.

“On Oct. 16, 1965, we moved into our house that we had built from those paintings,” said Hair Truesdell. “When we moved into that house that’s when we really exploded. We could produce about 20 paintings a day. We hired salespeople. Some of the people that are Highwaymen now were our salespeople. They sold for us, so we were really making a lot of money for that time.”

Hair and Newton’s practice of selling art out of their cars came to be used by many African American artists along the U.S. 1 corridor on Florida’s Treasure Coast.

Many found success.

More: Harry T. Moore helped thousands of blacks register to vote. It led to his assassination on Christmas night

More: Mary McLeod Bethune was born the daughter of slaves. She died a retired college president

When everything changed

However, in 1970, the African American art scene lost its charismatic leader when Hair was gunned down in a bar. He was only 29.

“Overnight, everything dies," said Hair's widow. "Nothing is left.”

Many of the African American landscape artists continued to paint, but waning interest after Hair's death coupled with new tastes and styles in the 1970s and 1980s saw much of the success fade away.

“We survived it all,” Hair Truesdell said. “We’re still living. Still standing and still we have the memory and we will always have the memory of Alfred, of his vision.”

In the mid-1990s Jim Fitch, a Florida art historian, discussed the African American painting movement of the 1960s in the St. Petersburg Times, using a label to describe their art.

How the 'Highwaymen' came to be

“That term is ‘The Highwaymen,’” Adams said. “The name came from the artery of U.S. 1 being the chief way to go up and down and sell your works of art. So it’s easy for us to, now that we have a term, to describe these artists.”

This created a new interest in their art, which is estimated to include 200,000 paintings.

One of the distinctive things that make the Highwaymen art unique is the frames and vibrant colors of the landscapes.

Especially early on, because they lacked the resources and supplies, Hair and others would paint on upson board. They framed paintings with crown molding and brushed them with gold or silver to give them a rustic look.

“I really think the board that we painted on, I just think it gave it vibrancy that you don’t get from canvas,” Hair Truesdell said. “Also, we shellacked our board, and then we put a sealant on the board, and then the paint just adhered to that sealant and I just think that it gave it life.”

The true number of Highwaymen artists has been debated, with some being considered second or third generation Highwaymen.

However, in 2004, the number of identified Highwaymen was set at 26 when they were inducted into the Florida Artists Hall of Fame.

They include: Curtis Arnett, Hezekiah Baker, Al "Blood" Black, brothers Ellis Buckner and George Buckner, Robert Butler, Mary Ann Carroll, brothers Johnny Daniels and Willie Daniels, Rodney Demps, James Gibson, Alfred Hair, Isaac Knight, Robert Lewis, John Maynor, Roy McLendon, Alfonso "Pancho" Moran, brothers Sam Newton, Lemuel Newton and Harold Newton, Willie Reagan, Livingston "Castro" Roberts, Cornell "Pete" Smith, Charles Walker, Sylvester Wells and Charles "Chico" Wheeler.

“Even though they might be painting similar subjects in a similar manner they each have their own individual viewpoints,” Adams said. “I think it’s important to honor these individual artists as well as the collective group. The collective story is really important, but it shouldn’t obscure the idea that these are individuals who are looking at subjects and painting with their own style. If you look closely you can see a wide range of different perspectives of how they approached a single subject.”

The A.E. Backus Museum in Fort Pierce celebrates the work and life of one of the great early Florida landscape artists. Backus also is credited for giving lessons to Harold Newton and Alfred Hair, two original Florida Highwaymen artists.

Highwaymen paintings can be seen at the A.E. Backus Gallery & Museum in Fort Pierce, as well as the Museum of Florida History in Tallahassee.

Many can be purchased at various websites in their honor.

There are also some pieces on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It’s wonderful that these artists are being recognized today and they’re continuing to be recognized,” Adams said. “These works have a timeless beauty. They are of a certain time and there were certain social and political and cultural forces that shaped how they were made and how the people made them, were able to make them. They really speak beyond that.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musical Mondays

Greetings and Salutations,

It is the first official Musical Monday! Woo-hoo! Cue the confetti and party music (Party in the USA by Miley Cyrus is acceptable). Now, my layout will be a bit odd, so I’m going to take the time to explain it this one time and that’ll be all as far as the actual posts themselves go, however, you are always welcome to message me if you’re confused about anything!

I will first name and give a brief description (serious Lex mode) of every artist mentioned as well as their social media information in case you would like to see more of them. After that, I will talk about specific songs since a lot of you probably are not looking for complete albums. I will then go into recent album drops, or my absolute favorites, that I loved. This is when I drop the “serious Lex mode” and act a little silly while gushing about the music. I will not be doing this for individual songs, instead, I will be doing a rating system!

The ratings will range from 1 through 5, with 1 being the most calming and 5 being more upbeat and fun. I think this will be easier when categorizing the individual songs themselves just so I don’t end up writing an essay about every song on the list. Plus, the artist summary should clue you in on their general aesthetic and groove.

I will note, however, that some artists will either have shorter bios or none at all for the simple fact that I cannot find any information outside of their music. For example, in this post, we have a SoundCloud artist that is very small and does not have the same fanbase as the others on the list do. I just briefly stated that he does not have much information about him, but I know he is releasing an EP soon. Now with all the boring stuff out of the way, lets jam out.

Some of these artists have completely taken over my playlist, and I have no idea how I survived without them before, while others have held a special place in my heart for years. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do, and please go send them some love by clicking on the links to their social media accounts.

Thanks

Lex

Artists:

Cigarettes After Sex

Cigarettes After Sex is an American Dream Pop band from El Paso, Texas. The group consists of lead singer/ songwriter, Greg Gonzalez who founded the band in 2008. Gonzalez, over the years, has also brought upon the help of keyboard player Josh Marcus, bassist Randy Miller, and drummer Jacob Tomsky. The group is known for its dream-like sound, ethereal vibe, and Gonzalez’s “androgynous” voice. The band’s first EP I. was released in 2012, with their single Nothing’s Gonna Hurt You Baby being a huge commercial hit. In 2015, the band released their single Affection, and two years later their self-titled album dropped. In August of this year, the group then announced their new album Cry was announced as well as the released of their solo song Heavenly. The album was released on October 25, 2019.

Show ‘em some love: Instagram Twitter YouTube Spotify

Brent Faiyaz

Christopher Brent Wood, or better known as Brent Faiyaz, is an American singer and producer from Columbia, Maryland. However, Faiyaz moved to Charlotte, South Carolina, and then ultimately to Los Angeles, California to further his music career. January 19, 2015, he released his debut single Allure followed by the release of his song, and lead single on his EP A.M. Paradox released in 2016, Invite Me. In October of 2016, Faiyaz along with producers Dpat and Atu formed a group called Sonder, releasing their debut single Too Fast on October 25, 2016. December 16, 2016, Faiyaz was a featured artist on Goldlink’s song Crew, alongside fellow rapper Sly Grizzly. This is Faiyaz’s most known song and has gained him a lot of success.

Show ‘em some love: Instagram Twitter YouTube Spotify

Kyle Dion

Kyle Dion is an American R&B singer from Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Dion began making music back in 2013 with the release of his song Better. After which he released a cover of Frank Ocean’s song Thinking About You which boosted his popularity. His first EP dropped in 2014 gaining over 1.6 million plays, which ultimately gained Dion a loyal fanbase. This only furthered his passion, and in 2016 he dropped his EP Painting Sounds. All of this success has led up to the release of his debut album SUGA dropping in March of this year. According to The Fader, “The funk-infused album takes listeners on a journey of self-discovery, love and timeless nostalgia all through the eyes of Dion's alter ego, Suga, as he grapples with fame and battles his inner demons.”

Show ‘em some love: Instagram Twitter YouTube Spotify

LilBootyCall