#and not ambiguous or in flux in any way; and most important of ALL she can never have experienced racism.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ok sorry the OTHER thing about lucienne is like. as previously stated she is dream's handpicked emissary from the waking world to the dreaming she's the diplomat in chief she's the translator she's the bridge. because the dreaming is, in a very real way, dream's own psyche, this is tantamount to giving lucienne a tremendous degree of access to his interiority and by transitive property also tantamount to entering into a deeply emotionally intimate relationship with her (unimportant for the purposes of this post whether that relationship is platonic or romantic).

now, in general, looking at the pattern of dream's close emotional relationships—dream doesn't share himself with people as a rule (beyond the access that all things that live have to the dreaming; but i'm talking about his self here, the one he doesn't like to acknowledge he even has), but when he does share with people, it's with people who have some shadow on the soul, so to speak. just looking at attested relationships in show canon, his deepest emotional connection seems to be with death, who embodies the duality of light and dark even better than he does himself. calliope is the muse of epic poetry—heroism and tragedy—and also bears the sort of divine pride that led her to cut dream off for hundreds or thousands of years when he wronged her. the less said about that other guy, the better, but he's no sunshine-rainbows-unicorns type—he's a soldier of fortune, a bandit and a killer, a man who profits from the sale of human life. even best bird matthew, in comix canon, had a sordid past that will maybe be partially retconned for the show but has still been gestured at.

dream likes the complicated ones. he's drawn to them. they speak to something in him that he won't acknowledge in himself (he has to be Whole, fully integrated, without reservation, because he is the king and he is the dreaming and if the dreaming ain't whole then the universe is in trouble—but he feels that ache nonetheless).

all that is to say: when people try to portray lucienne as dream's Designated Well-Adjusted Neurotypical Friend, i begin to harm and maim.

#chatter#as usual there is a larger pattern of behavior around this post that has been making me crazy for some time#it's the ''holder of the braincell'' trope but it's also just like the flattening of female characters of color in every possible dimension#so many people are terrified. TERRIFIED. to imagine a woman of color's pain#because the demands of shallow progressivism are such that they require you to acknowledge that A Black Woman Has Suffered More#Than Anyone Else Ever In The History Of The World Ever; Because Of Racism#but the demands of wider fandom are such that they require you to buy into the concept that A White Man's Suffering#Is The Only Suffering Worthy Of Care Attention Or Interest.#can't handle the dichotomy so instead they create the imago of a Black woman who has never suffered anything ever#she cannot be mentally ill; she cannot be disabled; if she is queer then it is in a way that is wholly self-contained and complete#and not ambiguous or in flux in any way; and most important of ALL she can never have experienced racism.#because racism As We Know is the worst form of suffering. so if she'd suffered racism then that would make her more worthy of#compassion than White Guy No. 37. which must not be#the very idea that lucienne is simply at peace with herself and the dreaming with no further complication.......like!#WOMEN OF COLOR ARE NEVER AFFORDED THAT KIND OF CERTAINTY. ARE YOU STUPID.#and by the way being reserved/calm/unassuming/practical are NOT absolute indicators of mental wellness.#y'all can see this when it's a white guy what is your fucking DAMAGE when it comes to women of color.#OPEN YOUR EYES. USE YOUR POWERS OF DEDUCTIVE REASONING. DREAM DIDN'T CHOOSE HER TO BE HIS THERAPIST.#DREAM CHOSE HER BECAUSE; PRESUMABLY; SHE ACHES. SHE CONTRADICTS. SHE GRAPPLES WITH THE SHADOW ON THE MIND.#SOMETHING IN HIM SEES A KINDRED SOUL IN HER. WAKE UP FOR THE LOVE OF GOD.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Become with Others

A reflection on the importance of intra-action in my performance practice.

I am sitting.

I am sitting in a rehearsal space.

It’s a big space.

And it’s mostly empty.

I could…

I could…

I could do a lot of things,

here

in this big open space.

I stand up.

I walk across the room.

I try moving my body a bit.

It feels good but it’s not what I’m looking for.

I try filling the void with my voice, which feels good too, but…

But

The stakes are low.

I try writing things on big pieces of paper. I hope it will fill the vastness around me, but...

But all it does is echo the expanse of my mind. So I try moving these big pieces of paper around, my generous handwriting seems flimsy against their broadness. And sitting somewhere in all this space is the thing I’ve tried so hard to bat away, with my body or with my voice or with my writing. Thinking if I fill it, it won’t have the space to exist.

“But if I were a real artist I would know what to do."

What am I supposed to do here?

How can I best use this space for my research?

What can I uncover?

Here.

Alone.

Who am I without anyone else?

via Somatic_based_content_only on Instagram. 19.04.21

This scenario repeated itself during a workshop with Dagmar Slagmolen, director of the Amsterdam-based music theatre company, Via Berlin. Over the past few months my research has focused on vulnerability and its role in audience participation. My aim is to create a method for accessing and utilizing my own emotional vulnerability to better connect with my audience in order to enhance and expand the participatory experience. In our initial meetings, Dagmar was very excited about this project, particularly my interest in the links between shame and vulnerability. The piece I am creating in order to explore some of these techniques, focuses around my personal sexual history and hopes to buff out some of the shame which is so deeply ingrained in the patriarchal narratives surrounding sexuality in western society. In the days prior to the physical workshop, I discussed my work with Dagmar and the three other workshop participants, which helped me condense and clarify my research so far. I was then given the task of continuing to think about and experiment with vulnerability during the workshop.. Therefore, after a brief talk with Dagmar upon arriving in the studio, I was left with, none other than….. space and time to experiment.

Spaces which I had time to experiment in

Sitting in this studio, I became increasingly aware of a considerable obstacle. Explore vulnerability with who? Myself? Can one even be vulnerable with one’s self? Vulnerability is an act of revealing, an act of (emotional) exposure (Brown 2012). I find this an impossibility considering the omnipresence of the self. At least for me personally, the idea of exposing my self to myself seems nonsensical, as my emotional vulnerabilities exist in relation to others. This notion of impossibility seems to parallel the more ambiguous feeling that I described in the introduction, which creeps in whenever I undergo a solo studio practice in order to create work. The work I make is not only the presentation of a skill or story or technique, but the intra-action of space, time, set parameters and most importantly, other people. While I may use studio time to learn or refine certain physical techniques, this is usually a small element of my practice. Just as I cannot experiment or rehearse my vulnerability alone due to the fact that the very notion of my vulnerability is conditional to the presence of others, so is it impossible for me to experiment or rehearse a performance which is reliant on inter and intra-actions with people around me.

Pieces of paper, large and small

If all the world’s a stage, then when and where do we rehearse? When and where do we experiment? According to performance scholar Richard Schechner, the extended childhood particular to humans is a rehearsal, where we learn the behaviours which we ‘restore’ each day in our performance as adults (2013, 29). However, as restored behaviour may be combined and adjusted in a multitude of ways, and as our co-performers, sets and scenery are invariably interchanged, one’s performances of restored behaviour are thus in eternal flux. The performance of everyday interactions is a constant improvisation structured through certain social parameters. Each experience becomes the rehearsal for the next. It is an act of becoming, an intra-action of the players, the space, the audience etc. Scholar and physicist Karan Barad defines intra-action as “a mutual constitution of entangled agencies” (2007, 33). As I understand intra-action, it negates the idea that anything can be independent from anything else. If I think about it in the context of interactions with others, I understand that my presence and actions do not come from a self that is independent of those around me, but instead materializes through my relationships with others. Moreover, because of the multiplicitous constellations of people, places and things that come into contact throughout daily life, this diffracts into exponential infinity.

As much of my practice relies on such intra-action between myself and the other persons in the performance space, I must then question the where, how and why’s of rehearsal in my practice. Improvisation has always been wildly fulfilling to me, and even more so when I have an audience. This overused saying of ‘dance like no one's watching’ has never made sense to me. It is the eyes of others that grant me the ability to take the risks that make for an exhilarating performance. It is here where I get an embodied sense of intra-action between the audience, and myself where our relationship invokes a disassembly of any and all facades of self.

Some reflections on my relationship to improvisation as a 14-year-old

As I better understand this relationship, it also becomes clear as to why cabaret has remained at the heart of my practice. While I may wear the same costume and perform to the same music for any given act, the stage which I step on is always different, anywhere from a small piece of cleared floor with an audience member given a light with which to illuminate it, to a circus tent in the middle of a music festival as swarms of drunk people wander in after a headliner rock band. I have given myself the same task and the same tools in each however, I must remain nimble and responsive to my audience’s and surroundings. In an interview with José Esteban Muñoz, Nao Bustamante, describes a similar working method “It’s very important for me to maintain a fresh space.. I have these 12 positions that I hit within the piece… and then within those 12 positions anything can happen, and I just allow myself to watch myself, watch the audience, watch the interaction, focus on that particular moment or balance” (2002). My performance is not one of set actions, but a response (to a response to a response…) within a microcosm of intertwined energies in a room. In speaking about the work of Bustamente, Jack Halberstam writes, ‘Her body must respond on the spot and in the moment of performance to the new configurations of space and uncertainty" (2011, 144). As I have noted in previous reflections on my practice, a frequent piece of feedback I receive is along the lines of ‘It was so great to watch you when everything went wrong’. This is usually in reference to some technical difficulties that I’ve had to fix before or during a performance, crouching awkwardly on the floor in whatever absurd costume I’m wearing. These moments are moments of failure in which holes of uncertainty are pulled and stretched and the audience engages in a different way than they have rehearsed. We are together in a liminal space of both watching and non-watching. I think that the reason why I seem to be adept at such moments is because I invite my audience to continue to engage with me as I make plain my failure. “It’s those moments of failure that also build empathy for the character” (Bustamante 2002). The intra-action between myself, the audience, the liminal space of performance/not performance and failure coalesce to create a space of vulnerability and empathy that is near impossible to recreate alone with myself in a rehearsal space.

“For I do not exist: there exist but the thousands of mirrors that reflect me. With every acquaintance I make, the population of phantoms resembling me increases. Somewhere they live, somewhere they multiply. I alone do not exist.” (Nabokov, 2011, 118).

A phrase I have repeated many times in collaborations over the years is, ‘It’s not about me’, which is both entirely true and entirely not all at once. It is, of course, always about me. I am always present, inescapable even, as the protagonist of my own life story. However, I am also unsure, as indicated by Nabokov above, and in relation to Barad’s concept of intra-action, if there is any essence of self that is able to exist independently of the world and the people in it. A friend from many years ago always talked about how everyone we encountered was only a reflection of ourselves, which is something I still ponder on often. In contrast, the artist, Ann Liv Young, under the guise of her persona Sherry (whose work I investigated recently in relation to my own) suggests that the opposite is true. She is a reflection of others, rather than vice-versa. Sherry is a highly confrontational and contradictory semi-autobiographical character which Young uses to create improvisational participatory work. During performances, she maintains that Sherry is merely a reflection of her audience, making statements such as, “I only work with what’s in the room. I am very boring. I am essentially a mirror” (Good Sherry, 2018). These proclamations are used particularly at moments when her audience seems uncomfortable with what Sherry is saying or doing. Young and I are both interested in using vulnerability in our work, however I find that Young as Sherry wants to draw out vulnerability from her audience, while using Sherry to deflect her own vulnerability. Whereas the methodology of my approach is more about creating space and leading by example. However, when one uses intra-action to examine these relationships we see that they may both exist concurrently or not at all. One is both a reflection and reflects others. If everyone we encounter is standing with a metaphorical mirror in order to call into our existence, then we too must be holding a mirror to realize all other’s existences. Similarly to the elusivity of an objective truth, the idea of a self, independent of the world around it, slips from the realm of possibility. The self is in a continual flux of intra-actions with what is outside of us. Thus, as I explore my practice and how I might better engage with vulnerability within it, I understand the centrality of intra-action, particularly with other human beings and come to understand how important the methods of performance-as-research and performance-as-practice are to my work. Moreover, while I may have engaged with both of these methods in my practice for many years, it is an element which I have often wished I could pull back from. However, by switching my focus in order to better understand how and why I use performance-as-practice, I will be able to explore the full depth and range of how performance-as practice might be used to its full potential within my practice.

Reflective reflections. Some props I acquired.

vimeo

....becoming something with others.

Barad, K. M. (2007) Meeting the universe halfway: quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. Brown, B. (2012) Listening to shame. (TED2012). Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/brene_brown_listening_to_shame (Accessed: 15 November 2020). Felden Krisis (@somatic_based_content_only) • Instagram photos and videos (no date). Available at: https://www.instagram.com/somatic_based_content_only/ (Accessed: 25 April 2021). Halberstam, J. (2011) The queer art of failure. Durham: Duke University Press. Muñoz, J. E. (2006) ‘The Vulnerability Artist: Nao Bustamante And the Sad Beauty of Reparation’, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 16(2), pp. 191–200. doi: 10.1080/07407700600744386. Nabokov, V. V. and Nabokov, D. (2011) The eye. New York: Vintage International/Vintage Books. Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=722896 (Accessed: 25 April 2021). Schechner, R. and Brady, S. (2013) Performance studies: an introduction. 3. ed. London: Routledge. Tactical Aesthetics (2019) Ann Liv Young: Everybody has a responsibility to respond (excerpt from ‘Good Sherry’). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqEJyWxWzzs&ab_channel=MGM (Accessed: 3 March 2021). Video: Interview with Nao Bustamante [videorecording]. (2002). Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/2333.1/5dv41nv8 (Accessed: 25 April 2021).

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay...

So the theory goes that Jumpman, the Mario from Donkey Kong, is actually the father of Mario and Luigi (based on the fact that the original DK is supposedly now Cranky Kong and the current DK, who has faced off against the current Mario, is the son of DK Jr.)

If that is true, then Jumpman is likely the same Mario that worked as a demolition man in Wrecking Crew, given both the era of the game and the fact that Jumpman could easily have been a generalized construction worker (as he was stated to be a carpenter in DK). There is a Luigi in Wrecking Crew, though, so maybe not, but who knows, twins could easily run in the family and maybe Jumpman named one of his sons after his brother

Either way, that would mean that Jumpman, the father of the Mario brothers, worked with Foreman Spike, who for some reason hated Jumpman and his brother. Depending on the game, Foreman Spike bears a striking resemblance to either Wario or Waluigi. Now, we already know that Wario and Waluigi are canonically not brothers, so I’m not saying that Spike is both of their dads.

Just one of them.

(Long post under the cut. This whole thing really got away from me, but I think it ended pretty nicely, so I hope y’all enjoy it)

Probably Wario’s, if I had to bet, given that we know Mario and Wario have known each other since childhood (stated explicitly in the instruction manual for Six Golden Coins), so it would make sense for them to know each other if their parents were work “friends,” and it would especially make sense for Wario to be as hateful of Mario if his dad, Spike, were hateful of Jumpman. Hell, it would even explain his name. Jumpman has a kid and names him after himself, and then Spike has a kid around the same time and decides to invoke some nominative determinism and labels his kid “bad Mario.”

How Waluigi fits into the picture is ambiguous, but with a number of simple solutions. While some early sources indicate that they are brothers (strategy guides, official websites, etc.), while later sources refer to them as either cousins (Mario and Sonic at the Olympic Winter Games) or as friends (Mario Sluggers, voice actor Charles Martinet). They could be adoptive brothers, but this wouldn’t really explain the visual similarities, unless Waluigi explicitly modeled his appearance after Wario or Foreman Spike. This wouldn’t require that they be brothers at all, though, as Waluigi could have done that even if he was just a friend. The cousin aspect works best at explaining the visual similarity and even the name, as that would mean that his name was chosen to spite Luigi just the same way that Wario’s was chosen to spite Mario. The only issue there is that we’ve never heard of Spike having any siblings. He’s had multiple conflicting designs, so MAYBE there’s multiple Spikes and Spike is a family name, but I doubt it.

Personally, while the cousin angle wraps everything up the most neatly, I’m still a fan of the idea that Waluigi is some kind of shapeshifted disguise for Tatanga, since the two are both purple misanthropes with an unhealthy obsession with Princess Daisy, a hatred for the Mario brothers and an odd friendship with Wario. This would also of course explain why the exact nature of their relationship is so unclear, since it would imply that they’re outright lying but can’t keep the story straight. I would rather the cousin thing, though, since I would like Tatanga to be able to make a comeback, but that would still be a really fun twist.

The one major hole in all of this, though, is that Pauline appears in Mario Odyssey and gives no indication that she’s not the same Pauline from Donkey Kong, implying that Mario and Jumpman are, as they’ve always been presented, the same person. However, there is surprisingly an explanation for this. You see, in the original Donkey Kong, the damsel in distress was a blonde woman referred to as Lady. It wasn’t until the remake for the GameBoy that she was redesigned to be the brunette Pauline that we know today. While particularly damning sources (Shigeru Miyamoto, Smash 4) have claimed that Pauline and Lady are the same person, various extended Mario media present them separately (The Cat Mario Show, a 1994 encyclopedia, various Mario manga), and even present them as having opposing personality types. Naturally, Shigeru Miyamoto should be considered the most credible source here, but that’s no fun, and he also said he was Bowser Jr’s mom, so I’m going to ignore him.

So.

Jumpman’s pet Cranky Kong kidnaps his girlfriend, Lady, and he has to save her. Sometime later, Jumpman orders two children from the stork with Lady, whom he names after himself and his twin brother, Luigi, after a somewhat delayed delivery. His work rival, Spike, and Spike’s brother...Stanley the Bugman, why not, maybe he blames Mario for DK getting into his green house, both have children delivered around the same time, and name them Wario and Waluigi to spite Jumpman’s children. The Mario brothers and Spike children grow up to hate each other, and DK Jr. has also grown up and decides to kidnap Mario’s girlfriend, Pauline, just as his father did to Lady all those years ago. Mario saves Pauline, but unlike Jumpman and Lady who were brought closer together by their trauma, they break up, although they remain friends. Some years later, after Mario has established himself as a recurring hero to the Mushroom Kingdom, gets a toy line which DK III becomes weirdly infatuated with, leading to Pauline’s second kidnapping by a DK (or this is the first time, and Mario vs. Donkey Kong 2 was just a remake of DK on the GameBoy to give more context, the specifics aren’t too important here). Sometime after this, Pauline becomes mayor of New Donk City, which is adorned with references to Donkey Kong and his family’s crimes as if it’s all one big joke to these people. But I digress.

Somewhere in all that, Mario is given a castle for some reason, which is the last straw for Wario, who I imagine is working on a farm at the time, given that his best friend is a hen named Hen. Deciding that back breaking labor doesn’t satisfy his ambitions while his rival lives it up as a hero, Wario enlists the help of the alien Tatanga (who now that I think of it, he may well have met on his farm during an attempt to abduct a cow or something) to trick Mario to leave his castle so that Wario may steal it.

After Mario foils Wario’s plot and reclaims his castle, Mario extends an olive branch and invites Wario to play tennis with everyone, as that’s just the kind of guy he is. Wario, realizing he doesn’t have a partner, either a) invites his cousin Waluigi, who has gone into construction like uncle Spike (evidenced by his excavator in Mario Kart), since he loves sports and hates the Mario brothers as much as Wario does, or b) recruits Tatanga and has him disguise himself as someone who could ostensibly pass as a family member to lay low in case anyone tries to hold him responsible for his crimes (which they wouldn’t since they never try to arrest Bowser or Wario, but apparently he doesn’t know that)

As far as I can tell, the only thing we’re missing is where Waluigi was when Wario and the other Star Children were being delivered by the Stork and intercepted by Kamek. Perhaps he got passed over since he didn’t have a star? Maybe Bowser captured him and found he didn’t have a star, then discarded him.

Actually, what if...

Waluigi was SUPPOSED to be delivered to Spike.

Waluigi was SUPPOSED to be Wario’s brother.

But when Bowser went back in time to find the seven Star Children, he messed up the route that Waluigi was supposed to be on. When the Stork got Waluigi back, he accidentally delivered Waluigi to the wrong house, the way he did to Mario and Luigi at the end of Yoshi’s Island (as shown in Yoshi’s New Island). Unlike with the Mario brothers, though, the Stork didn’t catch this mistake, and Waluigi grew up in the wrong household. Maybe it was even Stanley’s, and Waluigi’s inherently nasty personality clashed with Stanley’s kindly personality, but he still inherited his adoptive father’s love of plants! Can’t believe I was able to work that back in.

That’s why no one knows if they’re brothers, cousins or strangers! Because they don’t know who he was supposed to be delivered to, but they can’t deny the visual similarity! That’s why Waluigi’s so misanthropic, because he wasn’t delivered to the right house and he felt out of place!

That last bit could easily be explained by being raised under Spike’s influence, though, since Spike is apparently the kind of jerk who would sabotage his own employees to get a bigger paycheck for himself.

Either way, I think that lends to a really solid idea for the story of a Waluigi game.

A long time ago, I suggested a game where Waluigi somehow travels through time and goes through levels themed around various Mario franchise titles (Waluigi’s Time to Shine), but now I know how to frame it! Waluigi, feeling odd about his family situation, asks Bowser how he travels through time so he can see where he comes from. Bowser throws him through a wormhole and Waluigi witnesses the events that lead to the Stork delivering him to the wrong house. He decides this is either Bowser or the Stork’s fault (Bowser makes more sense, but it would be super funny if the Stork ends up being the final boss) and journeys to exact revenge. The spell or technology tethering him to the past messes up, however, resulting in Waluigi being in flux and going through all of the Mario franchise.

It’d be really funny if when playing through the Yoshi’s Island section he becomes his baby self and knocks Mario off of Yoshi (resulting in Mario’s capture by the Toadies), giving Yoshi some weird new ability the way the Star Children did in Yoshi’s Island DS, but I’m not sure that having one level have a completely different control scheme would be the best idea.

It could also be that Waluigi rides Yoshi as a full grown adult, which would also be pretty silly given his lanky proportions.

A Wrecking Crew level near the end would also be a fun way to bring the story full circle, revealing Waluigi’s relation to Spike and Wario, and establishing that Mario and Luigi are the children of Jumpman and Lady.

Waluigi, Nintendo’s ultimate loose end, would be the catalyst through which all of the loose ends of the Mario franchise are tied.

Get on that, @nintendo

Edit: This ended up having a couple of revisions, but rather then amend this post, I just ended up making two others. You can check those here and here

#super mario#waluigi#wario#foreman spike#mayor pauline#stanley the bugman#pauline#long post#speculation#my theories#game ideas

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Translating the Cyberpunk Future

I'm a video game translator, and I love my job. It's odd work, sometimes stressful, sometimes bewildering, but it always provides interesting and inspiring challenges. Every project brings new words, slang, and cultural trends to discover, but translating also forces me to reflect on language itself. Each job also comes with its own unique set of problems to solve. Some have an exact solution that can be found in grammar or dictionaries, but others require a more... creative approach.

Sometimes, the language we’re translating from uses forms and expressions that simply have no equivalent in the language we’re translating to. To bridge such gaps, a translator must sometimes invent (or circumvent), but most importantly they must understand. Language is ever in flux. It’s an eternal cultural battleground that evolves with the lightning speed of society itself. A single word can hurt a minority, give shape to a new concept, or even win an election. It is humanity’s most powerful weapon, especially in the Internet Age, and I always feel the full weight of responsibility to use it in an informed manner.

One of my go-to ways for explaining the deep complexity of translation is the relationship between gender (masculine and feminine) and grammar. For example, in English this is a simple sentence:

"You are fantastic!"

Pretty basic, right? Easy to translate, no? NOT AT ALL!

Once you render it into a gendered language like Italian, all its facets, its potential meanings, break down like shards.

Sei fantastico! (Singular and masculine)

Sei fantastica! (Singular and feminine)

Siete fantastici! (Plural and masculine)

Siete fantastiche! (Plural and feminine)

If we were translating a movie, selecting the correct translation wouldn't be a big deal. Just like in real life, one look at the speakers would clear out the ambiguity in the English text. Video game translation, however, is a different beast where visual cues or even context is a luxury, especially if a game is still in development. Not only that, but the very nature of many games makes it simply impossible to define clearly who is being addressed in a specific line, even when development has ended. Take an open world title, for example, where characters have whole sets of lines that may be addressed indifferently to single males or females or groups (mixed or not) within a context we don't know and can't control.

In the course of my career as a translator, time and time again this has led into one of the most heated linguistic debates of the past few years: the usage of the they/them pronoun. When I was in grade school, I was taught that they/them acted as the third person plural pronoun, the equivalent of the Italian pronoun "essi." Recently, though, it has established itself as the third person singular neutral, both in written and spoken English. Basically, when we don't know whether we're talking about a he/him or a she/her, we use they/them. In this way, despite the criticism of purists, the English language has brilliantly solved all cases of uncertainty and ambiguity. For instance:

“Somebody forgot their backpack at the party.”

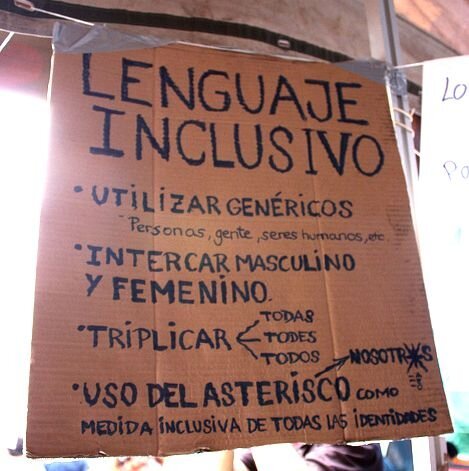

Thanks to the use of the pronoun "their," this sentence does not attribute a specific gender to the person who has forgotten the backpack at the party. It covers all the bases. Smooth, right? Within the LGBT circles, those who don’t recognize themselves in gender binarism have also adopted the use of they/them. Practically speaking, the neutral they/them pronoun is a powerful tool, serving both linguistic accuracy and language inclusiveness. There's just one minor issue: We have no "neutral pronouns" in Italian.

It's quite the opposite, if anything! In our language, gender informs practically everything, from adjectives to verbs. On top of that, masculine is the default gender in case of ambiguity or uncertainty. For instance:

Two male kids > Due bambini

Two female kids > Due bambine

One male kid and one female kid > Due bambini

In the field of translation, this is a major problem that often requires us to find elaborate turns of phrase or different word choices to avoid gender connotations when English maintains ambiguity. As a professional, it’s not only a matter of accuracy but also an aesthetic issue. In a video game, when a character refers to someone using the wrong gender connotation, the illusion of realism is broken. My colleagues and I have been navigating these pitfalls for years as best we can. Have you ever wondered why one of the most common Italian insults in video games is "pezzo di merda"? That's right. "Stronzo" and "bastardo" give a gender connotation, while "pezzo di merda" does not.

A few months ago, together with the Gloc team, I had the pleasure of working on the translation of Neo Cab, a video game set in a not too distant future with a cyberpunk and dystopian backdrop (and, sadly, a very plausible one). The main character is Lina, a cabbie of the "gig economy," who drives for a hypothetical future Uber in a big city during a time of deep social unrest. The story is told mainly through her conversation with the many clients she picks up in her taxi. When the game’s developers gave us the reference materials for our localization, they specified that one of the client characters was "non-binary" and that Lina respectfully uses the neutral "they/them" pronoun when she converses with them.

"Use neutral pronouns or whatever their equivalent is in your language," we were told.

I remember my Skype chat with the rest of the team. What a naive request on the client's part! Neutral pronouns? It would be lovely, but we don't have those in Italian! So what do we do now? The go-to solution in these cases is to use masculine pronouns, but such a workaround would sacrifice part of Lina’s character and the nuance of one of the interactions the game relies on to tell the story. Sad, no? It was the only reasonable choice grammatically-speaking, but also a lazy and ill-inspired one. So what were we to do? Perhaps there was another option...

Faced with losing such an important aspect of Lina’s personality, we decided to forge ahead with a new approach. We had the opportunity to do something different, and we felt like we had to do the character justice. In a game that's completely based on dialogue, such details are crucial. What's more, the game's cyberpunk setting gave us the perfect excuse to experiment and innovate. Language evolves, so why not try to imagine a future where Italian has expanded to include a neutral pronoun in everyday conversations? It might sound a bit weird, sure, but cyberpunk literature has always employed such gimmicks. And rather than take away from a character, we could actually enrich the narrative universe with an act of "world building" instead.

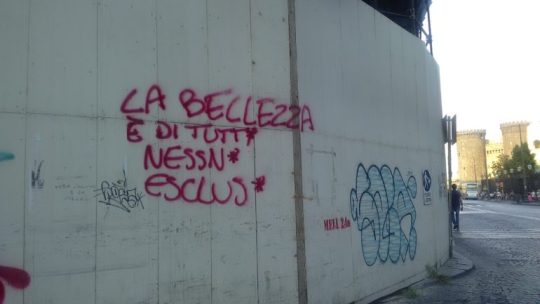

After contacting the developers, who enthusiastically approved of our proposal, we started working on creating a neutral pronoun for our language. But how to go about that was a question in itself. We began by studying essays on the subject, like Alma Sabatini's Raccomandazioni per un uso non sessista della lingua italiana (Recommendations for a non-sexist usage of the Italian language). We also analyzed the solutions currently adopted by some activists, like the use of asterisks, "x," and "u."

Siamo tutt* bellissim*.

Siamo tuttx bellissimx.

Siamo tuttu bellissimu.

I’d seen examples of this on signs before, but it had always seemed to me that asterisks and such were not meant to be a solution, but rather a way to highlight the issue and start a discourse on something that's deeply ingrained in our language. For our cyberpunk future, we wanted a solution that was more readable and pronounceable, so we thought we might use schwa (ə), the mid central vowel sound. What does it sound like? Quite familiar to an English speaker, it's the most common vowel sound. Standard Italian doesn’t have it, but having been separated into smaller countries for most of its history, Italy has an extraordinary variety of regional languages (“dialetti”) and many of them use this sound. We find it in the final "a" of "mammeta" in Neapolitan, for instance (and also in the dialects of Piedmont and Ciociaria, and in several other Romance languages). To pronounce it, with an approximation often seen in other romance languages, an Italian only needs to pretend not to pronounce a word's last vowel.

Schwa was also a perfect choice as a signifier in every possible way. Its central location in phonetics makes it as neutral as possible, and the rolled-over "e" sign "ə" is reminiscent of both a lowercase "a" (the most common feminine ending vowel in Italian) and of an unfinished "o" (the masculine equivalent). The result is:

Siamo tuttə bellissimə.

Not a perfect solution, perhaps, but eminently plausible in a futuristic cyberpunk setting. The player/reader need only look at the context and interactions to figure it out. The fact that we have no "ə" on our keyboards is easily solved with a smartphone system upgrade, and though the pronunciation may be difficult, gender-neutrals wouldn't come up often in spoken language. Indeed, neutral alternatives are most needed in writing, especially in public communication, announcements, and statements. To be extra sure our idea worked as intended and didn't overlook any critical issues, we submitted it to a few LGBT friends, and with their blessing, then sent our translation to the developers.

Fast forward to now, and the game is out. It has some schwas in it, and nobody complained about our proposal for a more inclusive future language. It took us a week to go through half a day's worth of work, but we're happy with the result. Localization is not just translation, it's a creative endeavour, and sometimes it can afford to be somewhat subversive. To sum up the whole affair, I'll let the words of Alma Sabatini wrap things up:

"Language does not simply reflect the society that speaks it, it conditions and limits its thoughts, its imagination, and its social and cultural advancement." — Alma Sabatini

Amen.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dusted’s Decade Picks

Heron Oblivion, still the closest thing to a Dusted consensus pick

Just as, in spring, the young's fancy turns to thoughts of love, at the end of the decade the thoughts of critics and fans naturally tend towards reflection. Sure, time is an arbitrary human division of reality, but it seems to be working out okay for us so far. We're too humble a bunch to offer some sort of itemized list of The Best Of or anything like that, though; a decade is hard enough to wrap your head around when it's just your life, let alone all the music produced during said time. Instead these decade picks are our jumping off points to consider our decades, whether in personal terms, or aesthetic ones, or any other. The records we reflect on here are, to be sure, some of our picks for the best of the 2010s (for more, check back this afternoon), but think of what follows less as anything exhaustive and more as our hand-picked tour to what stuck with us over the course of these ten years, and why.

Brian Eno — The Ship (Warp, 2016)

youtube

You don’t need to dig deep to see that our rapidly evolving and hyper-consciously inclusive discourse is taking on the fluidity of its surroundings. In 2016, a year of what I’ll gently call transformation, Brian Eno had his finger on multiple pulses; The Ship resulted. It’s anchored in steady modality, and its melody, once introduced, doesn’t change, but everything else ebbs and flows with the Protean certainty of uncertainty. While the album moves from the watery ambiguities of the title track, through the emotional and textural extremes of “Fickle Sun” toward the gorgeously orchestrated version of “I’m Set Free,” implying some kind of final redemption, the moment-to-moment motion remains wonderfully non-binary. Images of war and of the instants producing its ravaging effects mirror and counterbalance the calmly and increasingly gender-fluid voice as it concludes the titular piece by depicting “wave after wave after wave.” Is it all Salman Rushdie’s numbers marching again? The lyrics embody the movement from “undescribed” through “undefined” and “unrefined’” connoting a journey toward aging, but size, place, chronology and the music encompassing them remain in constant flux, often nearly but never quite recognizable. Genre and sample float in and out of view with the elusive but devastating certainty of tides as the ship travels toward silence, toward that ultimate ambiguity that follows all disillusion, filling the time between cycles. The disconnect between stasis and motion is as disconcerting as these pieces’ relationship to the songform Eno inherited and exploded. The album encapsulates the modernist subtlety and Romantic grace propelling his art and the state of a civilization in the faintly but still glowing borderlands between change and decay.

Marc Medwin

Cate Le Bon — Cyrk (Control Group, 2012)

youtube

There's no artist whose work I anticipated more this decade than Cate Le Bon, and no artist who frustrated me more with each release, only to keep reeling me in for the long run. Le Bon's innate talent is for soothing yet oblique folk, soberly psychedelic, which she originally delivered in the Welsh language, and continued into English with rustic reserve.

Except something about her pastoralism seems to bore her, and the four-chord arpeggios are shot through with scorches of noise, or sent haywire with post-punk brittleness. In its present state, her music is built around chattering xylophones and croaking saxophone, even as the lyrics draw deeper into memory and introspection, with ever more haunting payoffs. It's as if Nick Drake shoved his way into the leadership of Pere Ubu. She's taken breaks from music to work on pottery and furniture-making, and retreats to locales like a British cottage and Texas art colony to plumb for new inspirations. She's clearly energized by collaboration and relocation, but there’s a force to her persona that, despite her introverted presence, dominates a session. Rare for our age, she's an artist who gets to follow her muse full time, bouncing between record labels and seeing her name spelled out in the medium typefaces on festival bills.

Cyrk, from 2012, is the record where I fell in, and it captures her at something close to joyous, a half smile. Landing between her earliest folk and later surrealism, it is open to comparison with the Velvet Underground. But not the VU that is archetypical to indie rock – Cyrk is more an echo of the solo work that followed. There’s the sharp compositional order and Welsh lilt of John Cale. Like Lou Reed, she makes a grand electric guitar hook out of the words “you’re making it worse.” The homebound twee of Mo Tucker and forbidding atmosphere of Nico are present in equal parts. Those comparisons are reductive, but they demonstrate how Cyrk feels instantly familiar if you’ve garnered certain listening habits. Songs surround you with woolly keyboard and guitar hooks, and one can forget a song ends with an awkward trumpet coda even after dozens of listens. The awkwardness is what keeps the album fresh.

She lulls, then dowses with cold water. So Cyrk isn't an entirely easy record, even if it is frequently a pretty one. The most epic song here, reaching high with those woolly hums and twang, is "Fold the Cloth.” It bobs along, coiling tight as she reaches into the strange register of female falsetto. Le Bon cranks out a fuzz solo – she's great at extending her sung melodies across instruments. Then the climax chants out, "fold the cloth or cut the cloth.” What is so important about this mundane action? Her mystery lyrics never feel haphazard, like LSD posey. They are out of step with pop grandiose. Maybe when her back is turned, there's a full smile.

Who are "Julia" and "Greta,” two mid-album sketches that avoid verse-chorus structure? Julia is represented by a limp waltz, Greta by pulses on keyboards. Shortly after the release, Le Bon followed up with the EP Cyrk II made up of tracks left off the album. To a piece, they’re easier numbers than "Julia" and "Greta.” The cryptic and the scribble are essential to how Cyrk flows, which is to say it flows haltingly.

This approach dampens her acclaim and her potential audience, but that's how she fashions decades-old tropes into fresh art. She’s also quite the band leader. Drummers have a different thud when they play on her stage. Musicians' fills disappear. She brings in a horn solo as often as she lays down a guitar lead. The closer tracks, "Plowing Out Pts 1 & 2," aren't inherently linked numbers. By the second part, the group has worked up to a carnival swirl, frothing like "Sister Ray" yet as sweet as a children's TV show theme. Does that sound sinister? The effect is more like heartbreak fuelling abandon, her forlorn presence informing everyone's playing.

Fuse this album with the excellent Cyrk II tracks, and you can image a deluxe double LP 10th anniversary reissue in a few years. Ha ha no. I expect nothing so garish will happen. It sure wouldn't suit the artist. In a decade where "fan service" became an everyday concept, Le Bon is immune. She's a songwriter who seems like she might walk away from at all without notice, if that’s where her craftsmanship leads. The odd and oddly comfortable chair that is Cyrk doesn't suit any particular decor, but my room would feel bare without it.

Ben Donnelly

Converge — All We Love We Leave Behind (Epitaph)

youtube

Here’s the scenario: Heavily tatted guy has some dogs. He really loves his dogs. Heavily tatted guy goes on tour with his band. While he’s on the road, one of his dogs dies. Heavily tatted guy gets really sad. He writes a song about it.

That should be the set-up for an insufferably maudlin emo record. But instead what you get is Converge’s “All We Love We Leave Behind” and the searing LP that shares the title. The songs dive headlong into the emotional intensities of loss and reflect on the cost of artistic ambition. The enormously talented line-up that recorded All We Love We Leave Behind in 2012 had been playing together for just over a decade, and vocalist Jacob Bannon and guitarist Kurt Ballou had been collaborating for more than twenty years. It shows. The record pummels and roars with remarkable precision, and its songs maniacally twist, and somehow they soar.

Any number of genre tags have been stuck on (or innovated by) Converge’s music: mathcore, metalcore, post-hardcore. It’s fun to split sonic hairs. But All We Love… is most notable for its exhilarating fury and naked heart, musical qualities that no subgenre can entirely claim. Few bands can couple such carefully crafted artifice with such raw intensity. And few records of the decade can match the compositional wit and palpable passion of All We Love…, which never lets itself slip into shallow romanticism. It hurts. And it ruthlessly rocks.

Jonathan Shaw

EMA — The Future’s Void (City Slang, 2014)

youtube

When trying to narrow down to whatever my own most important records of the decade are, I tried to keep it to one per artist (as I do with individual years, although it’s a lot easier there). Out of everyone, though, EMA came by far the closest to having two records on that list, and this could have been 2017’s Exile in the Outer Ring, which along with The Future’s Void comes terrifyingly close to unpacking an awful lot of what’s going wrong, and has been going wrong, with the world we live in for a while now. The Future’s Void focuses more on the technological end of our particular dystopia, shuddering both emotionally and sonically through the dead end of the Cold War all the way to us refreshing our preferred social media site when somebody dies. EMA is right there with us, too; this isn’t judgment, it’s just reporting from the front line. And it must be said, very few things from this decade ripped like “Cthulu” rips.

Ian Mathers

The Field — Looping State of Mind (Kompakt, 2011)

Looping State of Mind by The Field

On Looping State of Mind, Swedish producer Axel Willner builds his music with seamlessly jointed loops of synths, beats, guitars and voice to create warm cushions of sound that envelop the ears, nod the head and move the body. Willner is a master of texture and atmosphere, in lesser hands this may have produced mere comfort food but there is spice in the details that elevates this record as he accretes iotas of elements, withholding release to heighten anticipation. Although this is essentially deep house built on almost exclusively motorik 4/4 beats, Willner also plays with ambient, post-punk and shoegaze dynamics. From the slow piano dub of “Then It’s White,” which wouldn’t be out of place on a Labradford or Pan American album, to the ecstatic shuffling lope of “Arpeggiated Love” and “Is This Power” with its hint of a truncated Gang of Four-like bass riff, Looping State of Mind is a deeply satisfying smorgasbord of delicacies and a highlight of The Field’s four album output during the 2010s.

Andrew Forell

Gang Gang Dance — “Glass Jar” (4AD, 2011)

youtube

Instead of telling you my favorite album of the decade — I made my case for it the first year we moved to Tumblr, help yourself — it feels more fitting to tell you a story from my friend Will about my favorite piece of music from the last 10 years, a song that arrived just before the rise of streaming, which flattened “the album experience” to oppressive uniformity and rendered it an increasingly joyless, rudderless routine of force-fed jams and AI/VC-directed mixes catering to a listener that exists in username only. The first four seconds of “Glass Jar” told you everything you needed to know about what lie ahead, but here’s the kind of thing that could happen before everything was all the time:

I took eight hours of coursework in five weeks in order to get caught up on classes and be in a friend's wedding at the end of June. Finishing a week earlier than the usual summer session meant I had to give my end-of-class presentations and turn in my end-of-class papers in a single day, which in turn meant that I was well into the 60-70 hour range without sleep by the time I got to the airport for an early-morning flight. (Partly my fault for insisting that I needed to stay up and make a “wedding night” mix for the couple — real virgin bride included — and even more my fault for insisting that it be a single, perfectly crossfaded track). I was fuelled only by lingering adrenaline fumes and whatever herbal gunpowder shit I had been mixing with my coffee — piracetam, rhodiola, bacopa or DMAE depending on the combination we had at the time. At any rate, eyes burning, skull heavy, joints stiff with dry rot, I still had my wits enough to refuse the backscatter machine at the TSA checkpoint; instead of the usual begrudging pat-down, I got pulled into a separate room. Anyway, it was a weird psychic setback at that particular time, but nothing came of it. Having arrived at my gate, I popped on the iPod with a brand new set of studio headphones and finally got around to listening to the Gang Gang Dance I had downloaded months before. "Glass Jar," at that moment, was the most religious experience I’d had in four years. I was literally weeping with joy.

Point being: It is worth it to stay up for a few days just to listen to ‘Glass Jar’ the way it was meant to be heard.

Patrick Masterson

Heron Oblivion — Heron Oblivion (Sub Pop, 2016)

Heron Oblivion by Heron Oblivion

Heron Oblivion’s self-titled first album fused unholy guitar racket with a limpid serenity. It was loud and cathartic but also pure beauty, floating drummer Meg Baird’s unearthly vocals over a sound that was as turbulent and majestic as nature itself, now roiled in storm, now glistening with dewy clarity. The band convened four storied guitarists—Baird from Espers, Ethan Miller and Noel Harmonson from Comets on Fire and Charlie Sauffley—then relegated two of them to other instruments (Baird on drums and Miller on bass). The sound drew on the full flared wail and scree of Hendrix and Acid Mothers Temple, the misty romance of Pentangle and Fairport Convention. It was a record out of time and could have happened in any year from about 1963 onward, or it could have not happened at all. We were so glad it did at Dusted; Heron Oblivion’s eponymous was closer to a consensus pick than any record before or since, and if you want to define a decade, how about the careening riffs of “Oriar” breaking for Baird’s dream-like chants?

Jennifer Kelly

The Jacka — What Happened to the World (The Artist, 2014)

youtube

Probably the most prophetic rap album of the 2010s. The Jacka was the king of Bay rap since he started MOB movement. He was always generous with his time, and clique albums were pouring out of The Jacka and his disciples every few months. Even some of his own albums resembled at times collective efforts. This generosity made some of the albums unfocused and disjointed, yet what it really shows is that even in the times when dreams of collective living were abandoned The Jacka still had hopes for Utopia and collective struggles. It was about the riches, but he saw the riches in people first and foremost.

This final album before he was gunned down in the early 2014 is full of predictions about what’s going to happen to him. Maybe this explains why it’s focused as never before and even Jacka’s leaned-out voice has doomed overtones. This music is the only possible answer to the question the album’s title poses: everything is wrong with the world where artists are murdered over music.

Ray Garraty

John Maus — We Must Become Pitiless Censors of Ourselves (Upset The Rhythm, 2011)

We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves by John Maus

Minnesota polymath John Maus’ quest for the perfect pop song found its apotheosis on his third album We Must Become Pitiless Censors of Ourselves in 2011. On the surface an homage to 1980s synth pop, Maus’ album reveals its depth with repeated listens. Over expertly constructed layers of vintage keyboards, Maus’ oft-stentorian baritone alternately intones and croons deceptively simple couplets that blur the line between sincerity and provocation. Lurking beneath the smooth surface Maus uses Baroque musical tropes that give the record a liturgical atmosphere that reinforces the Gregorian repetition of his lyrics. The tension between the radical ironic banality of the words and the deeply serious nature of the music and voice makes We Must Become Pitiless Censors of Ourselves an oddly compelling collection that interrogates the very notion of taste and serves an apt soundtrack to the post-truth age.

Andrew Forell

Joshua Abrams & Natural Information Society — Mandatory Reality (Eremite, 2019)

Mandatory Reality by Joshua Abrams & Natural Information Society

Any one of the albums that Joshua Abrams has made under the Natural Information Society banner could have made this list. While each has a particular character, they share common essences of sound and spirit. Abrams made his bones playing bass with Nicole Mitchell, Matana Roberts, Mike Reed, Fred Anderson, Chad Taylor, and many others, but in the Society his main instrument is the guimbri, a three-stringed bass lute from Morocco. He uses it to braid melody, groove, and tone into complex strands of sound that feel like they might never end. Mandatory Reality is the album where he delivers on the promise of that sound. Its centerpiece is “Finite,” a forty-minute long performance by an eight-person, all-acoustic version of Natural Information Society. It has become the main and often sole piece that the Society plays. Put the needle down and at first it sounds like you are hearing some ensemble that Don Cherry might have convened negotiating a lost Steve Reich composition. But as the music winds patiently onwards, strings, drums, horns, and harmonium rise in turn to the surface. These aren’t solos in the jazz sense so much as individual invitations for the audience to ease deeper into the sonic entirety. The music doesn’t end when the record does, but keeps manifesting with each performance. Mandatory Reality is a nodal point in an endless stream of sound that courses through the collective unconscious, periodically surfacing in order to engage new listeners and take them to the source.

Bill Meyer

Mansions — Doom Loop (Clifton Motel, 2013)

youtube

I knew nothing about Mansions when I first heard about this record; I can’t even remember how I heard about this record. But I liked the name of the album and the album art, so I listened to it. Sometimes the most important records in your decade have as much to do with you as with them. I’d been frantically looking for a job for nearly two years at that point, the severance and my access Ontario’s Employment Insurance program (basically, you pay in every paycheck, and then have ~8 months of support if you’re unemployed) had both ran out. I was living with a friend in Toronto sponsoring my American wife into the country (fun fact: they don’t care if you have an income when you do that), feeling the walls close in a little each day, sure I was going to wind up one of those kids who had to move back to the small town I’d left and a parent’s house. There were multiple days I’d send out 10+ applications and then walk around my neighbourhood blasting “Climbers” and “Out for Blood” through my earbuds, cueing up “La Dentista” again and dreaming of revenge… on what? Capitalism? There was no more proximate target in view. That’s not to say that Doom Loop is necessarily about being poor or about the shit hand my generation (I fit, just barely) got in the job market, or anything like that; but for me it is about the almost literal doom loop of that worst six months, and I still can’t listen to “The Economist” without my blood pressure spiking a little.

Ian Mathers

Protomartyr — Under Colour of Official Right (Hardly Art, 2014)

Under Color of Official Right by Protomartyr

By my count, Protomartyr made not one but four great albums in the 2010s, racking up a string of rhythmically unstoppable, intellectually challenging discs with absolute commitment and intent. I caught whiff of the band in 2012, while helping out with editing the old Dusted. Jon Treneff’s review of All Passion No Technique told a story of exhilarant discovery; I read it and immediately wanted in. The conversion event, though, came two years later, with the stupendous Under Color of Official Right, all Wire-y rampage and Fall-spittled-bile, a rattletrap construction of every sort of punk rock held together by the preening contempt of black-suited Joe Casey. Doug Mosurock reviewed it for us, concluding, “Poppier than expected, but still covered in burrs, and adeptly analyzing the pain and suffering of their city and this year’s edition of the society that judges it, Protomartyr has raised the bar high enough for any bands to follow, so high that most won’t even know it’s there.” Except here’s the thing: Protomartyr jumped that bar two more times this decade, and there’s no reason to believe that they won’t do it again. The industry turned on the kind of bands with four working class dudes who can play a while ago, but this is the band of the 2010s anyway.

Jennifer Kelly

Tau Ceti IV — Satan, You’re the God of This Age, but Your Reign Is Ending (Cold Vomit, 2018)

Satan, You're The God of This Age But Your Reign is Ending by Tau Ceti IV

This decade was full of takes on American primitive guitar. Some were pretty good, a few were great, many were forgettable, and then there was this overlooked gem from Jordan Darby of Uranium Orchard. Satan, You’re the God of This Age, but Your Reign Is Ending is an antidote to bland genre exercises. Like John Fahey, Darby has a distinct voice and style, as well as a sense of humor. Also like Fahey, his playing incorporates diverse influences in subtle but pronounced ways. American primitive itself isn’t a staid template. Though there are also plenty of beautiful, dare I say pastoral moments, which still stand out for being genuinely evocative.

Darby’s background in aggressive electric guitar music partly explains his approach. (Not sure if he’s the only ex-hardcore guy to go in this direction, but there can’t be many.) His playing is heavier than one might expect, but it feels natural, not like he’s just playing metal riffs on an acoustic guitar. But heaviness isn’t the only difference. Like his other projects, Satan is wonderfully off-kilter. This album’s strangeness isn’t reducible to component parts, but here are two representative examples: “The Wind Cries Mary” gradually encroaches on the last track, and throughout, the microphone picks up more string noise than most would consider tasteful. It all works, or at least it’s never boring.

Ethan Milititisky

Z-Ro — The Crown (Rap-a-Lot, 2014)

youtube

When singing in rap was outsourced to pop singers and Auto Tune, Z-Ro remained true to his self, singing even more than he ever did. He did his hooks and his verses himself, and no singing could harm his image as a hustler moonlighting as a rapper. He can’t be copied exactly because of his gift, to combine singing soft and rapping hard. It’s a sort of common wisdom that he recorded his best material in the previous decade, yet quite apart from hundreds of artists that continued to capitalize on their fame he re-invented himself all the past decade, making songs that didn’t sound like each other out of the same raw material. The Crown is a tough pick because since his post-prison output he made solid discs one after each other.

Ray Garraty

#dusted magazine#best of 2010s#brian eno#marc medwin#cate le bon#ben donnelly#EMA#ian mathers#the field#andrew forell#gang gang dance#patrick masterson#heron oblivion#jennifer kelly#the jacka#ray garraty#john maus#joshua abrams#bill meyer#mansions#protomartyr#tau ceti iv#Ethan Milititsky#z-ro#converge#jonathan shaw

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gallifrey Relisten: A Blind Eye

The end of Series 1! (I will admit I had to stop myself from immediately jumping into Lies because that’s when things really get going for me.) Some thoughts:

Mentions of/spoilers for: Neverland, Zagreus, Spirit, Insurgency, Enemy Lines, the Time War audios (but in a vague way).

Romana announces her name and title and then immediately follows that up with “I want no record of my being here” lol.

This episode is the closest we get to “everyone has to dress up fancy for an event” and it’s a shame we don’t get more of this! I would love more off-world and/or dress up episodes that are less......dire probably isn’t the right word because there’s some heavy things going on in this episode...maybe frantic? There is definitely a difference between the degree of tension in A Blind Eye and the degree of tension in the off-world episodes in Time War, for instance. (Also A Blind Eye has more banter.) I’m pretty sure it’s just A Blind Eye and Spirit that capture this sense of “we’re going to do something different for an episode” and I like it! (I feel like this is part of my ongoing push for a post-Enemy Lines, pre-Time War series of misc. CIA missions and shenanigans. Please someone just shove more side adventures into gaps in the timeline.)

The banter! The banter. (“You have your business face on. / You’re a transtemporal crook Arkadian, meeting you could never be a pleasure.”) 1. Arkadian is a supremely entertaining villain, and 2. he’s a tremendously good villain opposite Romana specifically, purely for snark and banter reasons.

I was never a big fan of the Sissy Pollard portrayal — the character’s personality feels too....exaggerated? Over the top? And not in an effective or interesting way.

Romana’s defense of Charley is actually quite sweet, given that they weren’t super friendly in Neverland/Zagreus.

Romana chastises Leela for careless talk, but uhhh if you wanted to keep things subtle and not reveal anything, maybe don’t have Leela suddenly grab Sissy?

“Madam, the Alps are in the other direction.” “Are they? Damn.” / “Be careful, you’ll break it!” “I’ll break you in a minute.” Truly, maximum levels of scathing Romana snark in this episode.

I have never seen anyone mention this, so I always assumed I’m not hearing it right, but....when the original!timeline train is about to crash into them....does Romana tell Narvin to fuck off?

Andred has a whole scene with no other Time Lord witnesses in which he could have told Leela the truth and yet.

“I am a Guard Commander of Gallifrey” apparently I never paid enough attention to what he actually said here because I think that was the first time I noticed that Andred gave his Chancellery Guard title, not his CIA title.

“Arkadian! You’ve met with that crook!?” Shoutout to Narvin for some A+ false indignation here.

I’m not sure there was a way to write a parallel between between real world Naziism and Leela’s fictional past without having it come off a bit as oversimplifying/cheapening the horrors of Nazi Germany. (But I’m white and raised Christian, so I’m also really not the person to be speaking in depth about the portrayal of Nazis in this episode.)

Does Arkadian know about Andred? I assume that he would just because he generally knows most things, but hmm it adds another layer.

Narvin is genuinely surprised when Romana gives in and agrees to leave lol.

Ms. Joy — it’s funny because we the listeners know that the one random character must be there for a reason, so it feels like the only reason the characters don’t know she’s suspicious is that they don’t know they’re in an audio drama episode and so she must be important to the plot.

Did Narvin really intend for Romana to go with “Torvald”? “At least he’s have been exposed?” Way to throw your President under the bus sir (although possibly he assumed that Torvald wouldn’t actually assassinate the President?)

“See, it is always a monster.” Wait, I take it back, Leela knows she’s in a Doctor Who (adjacent) episode.

“The only name in town where there’s temporal naughtiness to be done” — the Arkadian = Brax crack(?) theory is the most “I can’t unhear this” thing that’s happened to me since Narvin/Torvald. What is it with y’all and Series 1, I’m losing it.

...does Andred have a plan when he lowkey kidnaps Romana or is he just panicking? He is quite genuinely pleading with Romana to go along with him into the TARDIS and sounds genuinely desperate. But then he seems to regain control and starts more tactically trying to persuade Romana to work along side him without giving her any real answers. Although really, he must know that he’s very close to discovery — maybe he wants to resolve the past!Torvald situation first? Or maybe he’s not thinking that far ahead?

“I have no paws.” Awww K9.

“I think you’re a bad President. I think you’ve willfully sacrificed Gallifreyan influence upon the altar of your own increasingly cranky liberal agenda.” 1. “increasingly cranky liberal agenda” is such a specific insult wow, 2. I can’t tell how much of this is Andred still trying to be Torvald and how much he actually means this? The politics of this incarnation of Andred were always a bit fuzzy to me, even in series 2.

Also. Any conversation between Romana and Andred has a whole weird vibe on relisten when you know about the uhhh future murdering that’s going to happen.

I do love a Dramatic Reveal, and this one is incredibly dramatic.

....does the train crash? Does the train not crash? I’ve always been a bit confused about what happens in that moment — I assume Romana doesn’t actually plan on the train hitting the TARDIS, and we hear the TARDIS dematerialize so I think the train is fine? But it’s a weirdly ambiguous sound/end of scene.

“I can tell you are lying. It’s when your lips move.” Okay Leela snarking at Arkadian is also very good.

It is genuinely so interesting how connected this plot is to Neverland/Zagreus — if I had to pick one “you should listen to this audio before Gallifrey” I'd go for the Apocalypse Element because of the enormous ripples it casts in terms of Romana’s characterization (and also it’s more stand alone), but I imagine this episode would be particularly confusing without Neverland/Zagreus? (Would be curious to hear people’s experiences.)

“I never lie!” Romana, that’s the biggest lie you’ve ever told.

The narration of what happened to Andred by Andred and Romana is um. It’s a little bit obviously an info dump for the listener, but I’m not sure it’s the best way for Leela to find out? I mean, hearing the context and explanation probably was a better idea than just “oh btw I’m Andred”.....possibly this felt weird to me because of the acting? It’s very emotionally detached, very “so this is what happened” — Andred manages some emotion afterwards when he’s pleading with Leela but uh. He could have sounded more apologetic here.

Leela. Leela. “You have watched me suffer and worn my enemy’s clothes?” / “The man that I loved is dead.” Goddddd I want to give her a hug so much ughhhhh. Leela just goes through so many awful things throughout....all of Gallifrey actually, and she still remains such a good person with such a genuinely caring heart......give her a break please.

“I think the only person who’d actually benefit from a temporal war would be a...dealer in arms? A trader in secrets? A fixer and a fiddler. A dishonest broker with no scruples and no shame.” / “An interesting theory Madam. Prove it.” I just really like the delivery of this bit. Although: I realize there were several things going on at this point, but really, they just let Arkadian walk away at the end?

And thus ends Series 1. It has some highs and lows but it honestly ranks near the bottom on my constantly-in-flux list of favorite-to-least favorite Gallifrey series. (Weapon of Choice is probably the only episode I actively look forward to relistening to?) I said in my Weapon of Choice post that Series 1 was a nice “palate cleanser” after Apocalypse Element and the Charley arc through Zagreus, and that was true for the first time listening, but I think some of those same attributes mean I’m kinda meh about relistening to it. It just doesn’t hold my interest quite as much as many of the other series. (Series 2 though....👀)

EDIT: I realized I forgot to tell my personal story of my first time listening to the Andred reveal, and I wanted to have some record of that, even if I don’t quite remember the specifics of my reaction. In general, my first listen of Gallifrey was shaped by knowing a lot of major spoilers, which is what happens when you spent a lot of time lurking on Tumblr blogs in advance of listening to the series. (It actually led to a lot of super fascinating experiences of “well I know X happens, but I don’t know how or why” and being really curious to find out how X played out.)

So I knew something about Andred and Torvald going in, and I think I should have known that it was simply Torvald = Andred, but somehow I got it in my head that oh no, no it’s weirder and more complicated than that. But of course there are a lot of hints throughout series 1 that Torvald is Andred, so the first listen was this cycle of me going “I think maybe Torvald is just Andred? Nah, it’s going to be more convoluted than that. But no really, it makes sense that Torvald is Andred...” etc. etc. So it was a weird experience of knowing pretty early on that Torvald might be Andred, but still not being quite sure until the end of series one. The other bit of this is that I can’t remember at what point I knew that Andred died (and how) — I think I may have known he died before I listening to Gallifrey (or at the very least I knew that he was written out in some way or another earlier on), so that may have also confused me further re: the series one question of: what actually happened to Andred? All around, an odd experience of “I was spoiled...but somehow I still wasn’t sure what was going on” and I wasn’t surprised per se but it was still a reveal.

Next Episode Reaction: Lies

Previous Episode Reaction: The Inquiry

#gallifrey audios#i think i've timed this correctly to post around the same time as the podcast episode is coming out?#because i've decided i do like relistening on my own first and gathering my personal thoughts#and then hearing others' thoughts#it's a bit daunting because i feel the need to go 'i reserve the right to change my opinions if i'm persuaded in a particular direction'#but yeah!#edit: added what i remembered of my initial reaction to the andred thing because i meant to talk about that#romana#leela#narvin#andred#ramblings#emily listens to big finish#the relisten of rassilon

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘Postmodern art challenges all conventions within art — even the legitimacy of art itself.’ - an essay

Many times, I have pondered this quote. Twisting it through my brain... Myself having always preferring a Bosch over a Hirst, I attempt to push it past my own reservations towards postmodern art.

For postmodern art to be considered as a challenge of artistic convention, there would have to be an applied definition of art available to be contested. By the 1950s, many philosophers had been led to “despair of the possibility of defining ‘art,’” as George Dickie has noted. In an influential article published in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism in 1956, Morris Weitz declared, for example, that “the very expansive, adventurous character of art, its ever-present changes and novel creations, makes it logically impossible to ensure any set of defining properties.” Thus the postmodernist philosophy behind the art of Francis Bacon, and the postmodern art of the likes of Marina Abramovic and Cy Twombly, must be viewed as a natural evolution and trajectory of the art world, and should not be aligned to the viewpoint that their art is inherently an act of challenging (which in itself would restrict the true intention of the artist). In terms of the legitimacy of art, postmodern art encourages legitimacy, as it presents a rejection of teachings about the supremacy of reason and the notion of truth and the belief that man could be made perfect through art and architecture; which are all highly legitimate areas of sociological and philosophical debate that when interpreted through the vessel of the artwork, solidify the importance of artistic expression within our modern society.

The idea of a postmodernist ‘challenge’ is besides the point of postmodernist art, as it is more definitively a change of focusing — to art based on ideas rather than on formal features that characterised the Modernists (such as realism, landscape, narrative and history painting). To understand why postmodernism is currently such a dominant mode of art practice, it only takes a few moments to consider the progression of art to date, and to understand it as a constant conversation between an exchange of ideas and a response to the trajectory of society. Marina Abramovic is one such artist who proves this theory perfectly. Today Marina Abramovic is known as “the grandmother of performance art”, due to her role as a pioneer of the use of performance art as a visual arts medium. Abramovic began her career in performance in 1973, when she was already in her late twenties. Before that, as a student of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, Abramovic explored her interest in the body through paintings influenced by the abstract forms of Picasso. However, Abramovic found herself frustrated by the limits of expression in painting, and thus in a logical artistic progression upon her exposure to the performance art medium while at school in Zagred, her works became increasingly immaterial. Abramovic cited Marcel Duchamp and Dada, as well as the fluxes movement, as being immensely influential in her work. The early philosophy behind postmodernism is evident in her work, as Abramovic herself explains ‘I have arrived at the conclusion that… the performance has no meaning without the public because, as Duchamp said, it is the public that completes the work of art. In the case of performance, I would say that public and performance are not only complimentary but also inseparable.’ It is important to know that the movements origins can be traced to the more fundamental critique on capitalist society of the late nineteen sixties and early nineteen seventies. Perhaps Abramovic’s most famous piece is Rhythm 0 (1974). With a description reading “I am the object”, and “During this period I take full responsibility,” Abramovic invites spectators to use any of 72 objects on her body in any way they desire, completely giving up control. Rhythm 0 is exemplary of Abramovic’s belief that confronting physical pain and exhaustion was important in making a person completely present and aware of his or her self; a nod to the introspection of postmodernism. This work also reflects her interest in performance art as a way to transform both the performer and the audience. She wants spectators become collaborators, rather than passive observers. Although the use of collaboration and the body as the medium could be considered as a challenge of artistic convention, it is more insightful to consider it as an upward trajectory from modernist concepts to our contemporary status of practice. Abramovic’s work does not attempt to defy traditionalism, but rather to free art from the restriction of paint and canvas to ensure that art remains reflective to our innovative present.