#and not a lot of labial consonants

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Looking at some northern Athabaskan languages. How often do you see dental affricates?! Cool stuff.

(Source: Kaska language on Wikipedia)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

actually just came up with an amazing phonology for a protoclong like

i think i have like 2 plans generally for the daughter langs:

first option, dorsal consonants become palatal bc of /j/, potentially they then shift further to alveolar, labiovelars could lenite, losing their labialness and becoming plain ol velars, ends up with the standard like labial-alveolar-velar system

second, dorsal consonants could shift even further back to uvular/glottal sounds, labiovelars could lose labialness again, ends up with a labial-(labio)velar-uvular/glottal system which is a lot more unique fr

and then with the vowels i wanna merge i-u and e-a in at least one of the daughters bc i think itd be pretty cool

im hoping i can use this in a conworld i wanna make, might post updates on that here if it keeps me motivated

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arknights: Durin Conlang

So... I just learned that Arknights and its world of Terra has its own version of the vertically challenged underground-dwelling comedy relief people. so, like any sane artist I decided that they too will get their own language alongside the other languages I have cooking for the other nations (which I should make a list for, like the Mass Effect one).

in under an hour of brainstorming, I know these things will be featured:

Grammatical features will be governed by affixes that change and or remove the existing phonemes/suprasegmentals of the root word. in other words, changing the stress and/or tone, the place/ manner of articulation of the consonants, and/or the openness, frontness, nasality, length, voicing, etcetera of the vowel will determine things like tense, plurality, person, and other features that I haven't seen in any other natural or constructed language.

Derivational affixes (those that change the definition of the word itself down to whether it's now a noun or a verb) will use the more traditional prefixes, suffixes, circumfixes, and the rare infix. as well as good old compounding.

derivation includes a tool for doing the verb, a person who does the verb, and the person who is the receiver of the verb. e.g. "weapon", "warrior/soldier", and "murder victim" could have the same root.

the two systems above have their own metaphorical terms to describe how they work and are viewed by native speakers. respectively, they are called "Sculpture" and "decoration". with grammar being viewed as -- in this case -- literally changing and refining the shape of the word. while the derivations are viewed as adding little touches to an already finished work.

The phonology of this language will have lots of plosive. perhaps in addition to using most places of articulation, they are more diversified by secondary articulations like aspiration, palatalization, labialization. maybe there are additional phonemes such as affricates, nasal releases, lateral releases, rhotic releases, that will drive up that plosive count.

Syllables might have plosives and/or affricates in the onset and the other consonants like nasals and liquids in the coda. this is based on English onomatopoeia like "bam", "clang", "crash", etcetera. a sort of friendly acknowledgement at the literary roots that the race is no doubt based on.

These are the things that I am most sure to include in the final version of the language. but they are also subject to change. already I am wondering if I should switch the morphological nature of the grammar and derivational morphologies. seeing as derivation is more like changing the shape of a word more deeply while morphology is more like the bits and pieces you would add afterwards. what would you think?

there are also some features I am considering but not yet sure about committing to just yet. some of those features being:

subject and object person being marked by the manner of articulation in the onset and coda.

tense/aspect/mood/other marking via the properties of the vowel in the root's nucleus.

direction words encoding three-dimensional information due to living in an underground maze-like environment.

a metaphor for time going from light to dark.

This is all I got for now, I'll try to keep you updated on any progress. till then, feedback is appreciated. till next time... ;).

#mvtjournalist speaks#conlang#conlanging#constructed language#conlang idea#fanlang#fanfiction#fanfiction writing#creative writing#arknights#durin#arknights durin#durin arknights#arknights fanfic#arknights fanfiction

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

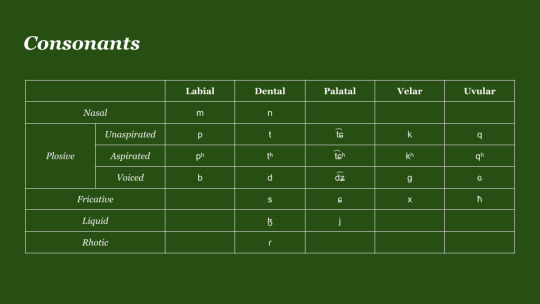

Movelang #001 - Phonology and Sound System

Nophhurra, and hello again everyone! It's time for another post showing off my experimental conlang, Movelang! This time around, I'll be going over Movelang's sound system: the consonants and vowels used, along with a currently loosely-defined syllable structure, as well as allophony!

Admittedly, the Phonology has been one of the aspects of Movelang which has been altered several times over, and has gone through several iterations before reaching the point at which it exists in the present. Since the emphasis for this conlang was moreso on grammar than on the phonoaesthetic, I had largely loosely defined it at the start, with only a vague idea of what Movelang would sound like. At the start, I took a lot of inspiration from the Coptic Language, as well as several African and Caucasian Languages. Later on as I began being more deterministic about the phonetic inventory of the language, it did change from this original vision in several ways, but I ended up ultimately with something I really like!

(My charts tend to prioritize neatness over exactness, so if there's a sound somewhere that doesn't exactly describe it completely correctly, please don't fight me 😭)

Phonemically, the consonant inventory consists of 2 nasals, 15 plosives, 4 fricatives, 2 liquids, and 1 tap. The plosives are split three ways by mode of articulation, where 5 stops are unaspirated: /p t t͡ɕ k q/, 5 stops are aspirated: /pʰ tʰ t͡ɕʰ kʰ qʰ/, and 5 are voiced: /b d d͡ʑ g ɢ/. Each mode of articulations contains a labial, dento-alveolar, palatal, velar, and uvular stop respectively. This was a choice inspired by both Ancient Greek, as well as the Coptic and Caucasian influence I mentioned earlier, and in an earlier version of the phonology, the palatal affricates were instead alveolar affricates: /t͡s t͡sʰ d͡z/. Accompanying the stops are 4 fricatives that roughly match 4/5 of the same manners of articulation: /s ɕ x ħ/. These were selected mainly for that reason, that they lie in the same POA as their stop counterparts, but I decided to throw in an oddball for the fricative furthest towards the back of the mouth. Originally, this was /h/ phonemically, but I was intrigued by Maltese's presence of /ħ/ as the sole voiceless fricative closest to the back of the mouth, so I decided to do this for Movelang, and I do love how it sounds! I personally think /x/ and /ħ/ pair nicely with each other! The Approximants and Nasals then weren't that hard to reckon, I simply filled in the gaps in the chart respectively. When I got to my /l/ sound though, I decided to make this a little bit different as well, and follow the lead of Mongolian, and make it /ɮ/ instead. I also made the decision to omit /w/ or any similar sound, since I have a habit of using this sound a lot whenever I make new sound systems, as a bit of a monkey-wrench to try and make myself work with.

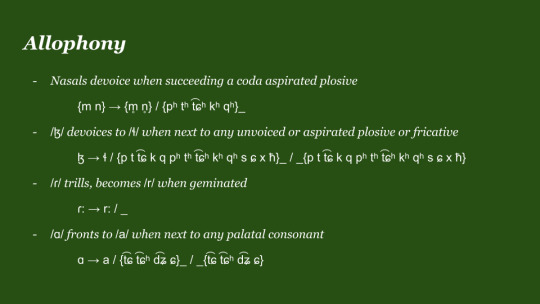

For Allophony, most of this deals with the pronunciation of consonants. There are 3 major rules that come into effect when pronouncing consonants in particular places within a word. First, the nasals, /m n/, devoice to /m̥ n̥/ whenever they are preceded by a syllable that has an aspirated plosive in the coda, any of /pʰ tʰ t͡ɕʰ kʰ qʰ/. Secondly, /ɮ/ may devoice to /ɬ/ when next to any voiceless sound: a voiceless plosive or fricative. Finally, the alveolar tap /ɾ/ becomes trilled /r/ when it is geminated. These rules as you'll notice mostly depend on a sound's locale within a syllable, which I'll explain in greater detail when discussing syllable structure...

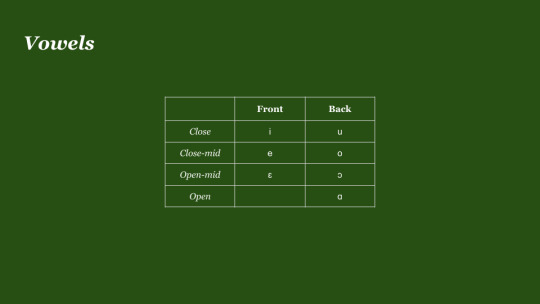

As for the vowels, these are quite simple. Movelang consists of seven phonemic vowels, which compliment the front and the back of the mouth. Movelang contains no phonemic length, tone, nasality, or anything else that would affect vowel quality in this way, at least phonemically, and only has these 7 plain oral vowels. There are 3 front vowels: /ɛ e i/, all of which are unrounded, and 4 back vowels: /ɑ ɔ o u/, all of which are rounded, except for the open back vowel.

In terms of vowel allophony, nothing really major happens to vowels. The only major rule which takes place with vowels, is that /ɑ/ goes to /a/ when near a palatal sound.

Additionally, the syllable shape in Movelang is pretty straightforward, it's pretty much CVC, but with a few additional caveats. The main difference, is that /j/ cannot be a coda consonant, which is reflected by the use of D for the coda consonant in my syllable shape notation, and additionally, only 6 consonants can end a word: /m t k q s r/, which is reflected by the use of K for a word-final coda consonant.

In addition to these tactical features, hiatus is permitted in Movelang, meaning that the onset consonant in syllables is optional even word-internally, and when this happens, the parallel vowels flow together smoothly, rather than having some epenthetic consonant placed between them, like a glottal stop. Gemination also happens quite frequently in Movelang, especially in compounds, and it is under these circumstances when /j/ technically can appear in the coda of a syllable, but only as a part of a geminate /j:/.

=-=-=-=

Alright! Well, that's pretty much it for phonology, at this point I'm going to try and stick to this phonology and not impulsively change it again, but knowing me, I can't make any promises XD. I hope you all enjoyed this look at the sound system! I look forward to posting some lexical samples in the next post, with these sounds intact, where I'll be showing you Movelang's class system in action! More on that later of course... Until then, I look forward to it, and I hope you all enjoyed this post! If you all have any questions, feel free to leave me a comment, or an ask!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

After making several images featuring my conlangs, I feel like I should actually explain what they are and how they work. So here’s a showcase of the one I made first, Arihuran (I’ll show off the others at a later date).

First, to explain the lore behind all of the languages. These languages are spoken in a world where cats evolved language comprehension sometime while being domesticated in the Middle East, adopting the language of their domesticators (Proto-Afro-Asiatic). Their version of PAA was different in that there were some sounds cats couldn’t pronounce, so sounds changed or were dropped (Proto-Cattic). As cats spread across the world, their language diverged into 4 separate languages (realistically it would be a lot more but 4 is all you’re getting from me).

Things the Cattic languages have in common (so I won’t have to repeat myself in the other showcases):

SOV word order

Adjectives before nouns

Adverbs before verbs

No definite article (except in Chattish)

No grammatical number

No case system

While yes these do make them very simple languages, I mean they’re cats, they’re simple creatures, compared to humans anyway (also I’m lazy). Now on to Arihuran specifically. Arihuran is spoken around the Mediterranean, primarily in the Middle East. Arihuran has had little to no real outside influence, yet it is very different from its proto language. It’s consonants are:

The first thing to notice is that there’s no labial consonants, this is because cats don’t have lips, so labial sounds wouldn’t be phonemic to them. What’s not because of their biology is the lack of alveolar plosives or fricatives. This is due to a sound change that shifted them further back into the mouth (explaning palatal /c/ and /ɟ/). Onto the vowels:

Again because cats don’t have lips, there are no rounded vowels. Arihuran has vowel length distinction (“hoor” /həːɹ/ (language) and “hor” /həɹ/ (fly)). /ɑ/ is an allophone of /a/ when before /ɹ/, which then becomes [ɑ˞] (“kkar” [kxɑ˞] (horn)). Similarly /əɹ/ becomes [ɚ] (so “hoor” and “hor” from before are actually pronounced [hɚː] and [hɚ] respectively).

All of the Cattic languages have a past-tense prefix and an action prefix, in Arihuran these are “sar-“ and “sa-“ respectively (“dä’ü” (walk), “sardä’ü” (walked), “sadä’ü” (walking)). There’s also the possessive prefix “i-“ that’s consistent across all the Cattic languages too (“su” (he), “isu” (his)).

As Arihuran is an Afro-Asiatic language it has cognates with other Afro-Asiatic languages, here are a few:

I’ll end this showcase with a sentence in Arihuran:

an ġîlloq ya sar sarya saräl, an kkarloq sarya saräl, syäg an añot häya saräl.

[I rabbit day ago yesterday PAST.see, I deer yesterday PAST.see, and I you today PAST.see]

“(The) day before yesterday I saw a rabbit, yesterday I saw a deer, and today I saw you.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danganronpa in toki pona part 1: names

toki!

since Im both a danganronpa fan and a conlang enjoyer, I had the idea a while ago to try and translate parts of it into toki pona (not whole games, god no. just snippets, maybe some ftes). while I assume this is mostly going to interest people who already know about conlangs, I still want it to be readable by people who have never heard of them in their life. so

what is toki pona?

toki pona is a conlang (short for constructed language, a language someone made up, think: esperanto or tolkiens languages. theres a lot I could talk about here but rn thats all you need to know) made by sonja lang. it was created to be as minimalistic as possible with a vocabulary of about 120 - 150 words depending on who you ask. it onls has 9 consonants and 5 vowels, which means theres some restrictions for how you can transliterate names into toki pona (called 'tokiponization').

lets get into how that works

tokiponization

since tokiponization is based on pronounciation rather than spelling, its important to know what sounds were working with. this is where I might lose some folks that dont know any linguistics stuff, but this section is optional. you only need to read it to find out how the names turned out the way they did, and how to say them out loud.

consonants

the nine consonants of toki pona are m, n, p, t, k, s, w, l, j. these are pronounced like their ipa (international phonetic alphabet) counterparts. its not necessary to know what that means, just know that [j] is pronounced like english <y> (as in yes, not as in synth). everything is else is p much how an english speaker would expect it.

the way consonants are tokiponized goes as follows:

voiced stops and fricatives are devoiced (z, d, g, b > s, t, k, p)

labial fricatives (f, ɸ) become p

coronal fricatives (and affricates) (θ, ʃ, ɕ, ts, tʃ, tɕ) become s

the japanese r [r] becomes l (the english r [ɻ] becomes w)

h is dropped word-initially and becomes w or j intervocalically

v can become p or w but Ill use w here

vowels

toki ponas vowels are a, e, i, o, u. this is almost the same as japanese, which has ɯ instead of u, but since its just the same sound with a rounding difference its tokiponized as u. japanese also has a length distinction, which toki pona doesnt, meaning long and short vowels will simply be the same length.

syllables

toki ponas syllable structure is CV(n) meaning that each syllable must have a consonant and a vowel (except word-initially where it can be just a vowel) and can optionally end in n. this is fairly similar to japanese syllable structure, but one thing is that japanese has palatalized consonants. this is pretty easy to solve by just inserting -ij- to mimic the sound. generally with tokiponization its preferable to preserve syllable count rather than add extra sounds but 1) if you say it quickly its barely noticable and 2) its my project and I can do what I want.

the other thing is that while in toki pona, vowels need to be seperated by at least one consonant, japanese allows you to theoretically chain together as many vowels as you want. I tried to find out whether vowel sequences are pronounced as diphthongs or disyllabically and turns out its a little complicated because those terms are defined in terms of syllables and japanese is mora-timed rather than syllable-timed. Ill admit I only have the faintest clue what a mora is but for the purposes of this project I will be treating vowel sequences as seperate syllables when possible. if it isnt, due to the syllables wu, wo, ji, and ti being forbidden in toki pona, Ill treat them like diphthongs in that the second vowel is just dropped entirely.

some smaller notes:

the only phoneme allowed in syllable codas is n, so for example gundham becomes kantan

stress always falls on the first syllable

and the final, rather important thing

the way names work in toki pona is that you have to describe what the thing is before saying the name (for example, canada is called ma Kanata, which literally means canada-place). therefore people are generally called jan [name], however, some tokiponists use a different term before their name (called a head noun) either for fun or to express something about themselves (such as many plural systems using kulupu ("group")).

theres quite a few options for varying what head nouns someone uses for themselves or others to add nuances. for example, I think gundham might refer to himself as a jan wawa ("powerful (in the sense of supernatural powers in this case) person"), or perhaps hiyoko might call mikan a jaki instead of a jan to insult her. theres a lot of fun to be had here.

the actual names

THH:

jan Makoto Najeki

jan Kijoko Kilikili (note: kili is the toki pona word for fruit so her name here literally says fruit-fruit)

jan Pijakuja Tokami

jan Toko Pukawa

jan (moli) So (note: jan moli here would mean killer to translate the spirit of her original title better, but since her talent would include it anyways Im not sure whether to use it?)

jan Sajaka Masono

jan Lejon Kuwata

jan Siwilo Pusisaki (note: yes this means their name is pronounced pussysaki. do with this info what you will)

jan ante/jasima (note: alter ego. lit: "different/reflection person", I feel like jasima fits more but Im also kinda unsura abt using nimi pu ala in the names and talents. I would definitely use at least nimi ku suli in the actual translations but for names and talents its like. hm :/)

jan Monto Owata

jan Kijotaka Isimalu

jan Ipumi Jamata

jan Selesija Lutenbeku/Tajeko Jasuwilo

jan Jasuwilo Akakule

jan Sakula Okami

jan Awi Asawina

jan Mukulo Ikusapa

jan Sunko Enosima

soweli Monokuma

SDR2

jan Asime Inata

jan Isulu Kamukula

jan Sijaki Nanami

jan Nakito Komajeta (note: I think he may also switch to a more self deprecating head noun when hes having a Moment)

jan Sakisi/Pijakuja Tukami (note: since tu means two, the togami/twogami thing works just as much in toki pona as it does in english)

jan Lijota Mitala

jan Telutelu Anamula

jan Mawilu Kowisumi

jan Peko Pekojama

jan Pujuwiko Kusuliju

jan Ipuki Mijota

jan Ijoko Sajonsi

jan Mikan Sumiki

jan Akane Owali

jan Nekomalu Nita

jan Kantan Tanaka (note: probably calls himself jan wawa or perhaps even usawi ("magic/supernatural") if I feel spicy enough to include nimi sin)

jan Sonja Newaman

jan Kasuwisi Sota

soweli Usami/Monomi

NDRV3

jan Kajete Akamasu

jan Suwisi Sajala

jan Kato Momota

jan Maki Alukawa

jan Kokisi Oma

jan Lantalo Amami

jan Lijoma Osi

jan Kilumi Toso

jan Imiko Jumeno

jan Ansi Jonaka

jan Tenko Sapasila

jan Kolekiju Sinkusi

jan Miju Iluma (note: I think she may also call herself jan sona or smth like that for "genius")

jan Konta Kokuwala

jan Kipo (note: possibly he gets called jan ilo (robot, lit: "tool/machine-person") to convey how the others set him apart from humans at times. kokichi probably calls him just ilo when he wants to get a rise out of him)

jan Sumuki Silokane

soweli Monotalo

soweli Monosuke

soweli Monopani

soweli Monotan

soweli Monokito

UDG. I guess

jan Komalu Najeki

jan Monaka Towa

jan Masalu Tamon

jan Satalo Kemuli

jan Kotoko Usuki

jan Nakisa Sinkesu

jan anpa (note: this is servant, anpa means "below, downward, lowly")

jan Asi Towa

jan Iloko Akakule

jan Tasi Pusisaki

jan Juta Asawina

soweli Silokuma

soweli Kulokuma

#this is my personal little autism project <3 even if it has an audience of like -2 people#danganronpa#dr#thh#sdr2#ndrv3#udg#toki pona#conlangs#tokidr

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

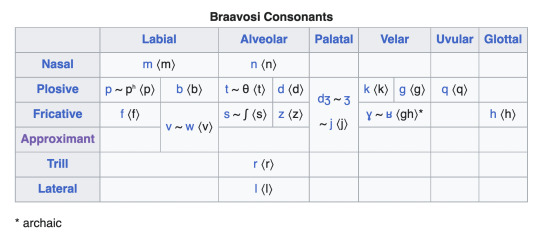

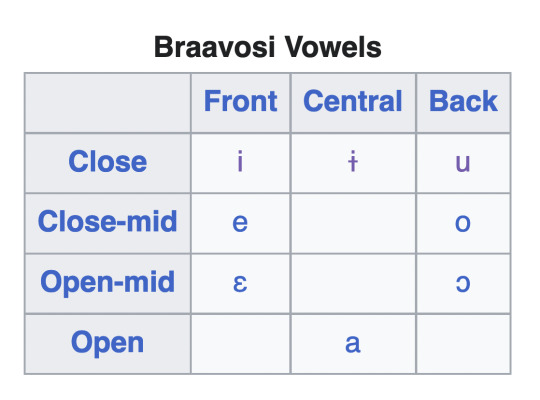

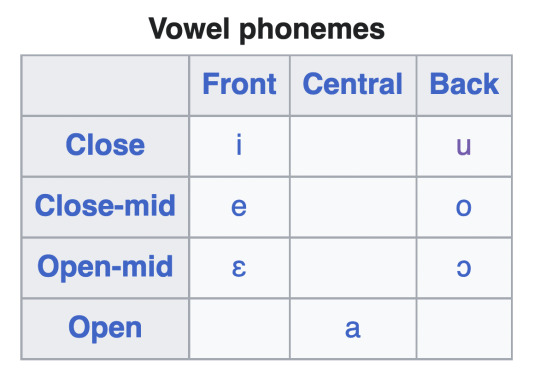

The Titan’s Tongue: The Language and Script of Braavos

Been thinking a lot about Braavos and the writing system of its tongue. Arya and Sam’s chapters exploring the city are so full of flavor and life that I wanted to gain a glimpse into its writing as well, and see what it would be like. We unfortunately have very little information about the Braavosi language, with it being completely absent from the show and only mentioned in passing in the books that the Waif is teaching it to Arya as part of her training in the House of Black and White. What little we know is largely names, but from this we can ascertain a bit about the language, and what we need for the script itself. The language seems to be to High Valyrian what Italian was to Latin: reduced vowel system (no distinction between short and long vowels, similar to Astapori Vayrian), eschewal of consonant clusters in favor of gemination (like in Tagganaro and Bellegere), and preference to end words in vowels.

Over the course of this post I will be trying to determine the sounds we would find in Braavosi and create an alphabet for the city’s people

Phonology

I imagine that the Braavosi have had a script loosely descendant from the High Valyrian writing systems, developed about 400 years ago when the first escaped slaves landed in the shrouded lagoon that is now the city’s harbor. These slaves and Moonsingers would have likely spoken a Low Valyrian tongue absent of some of the sounds that are represented in High Valyrian. By loose descent, I mean essentially that the letters are not necessarily one-to-one drawn from specific Valyrian glyphs (like Phoenician and Egyptian) but instead used as general inspiration. I also imagine that the Braavosi script is rather rounded and elegant, primarily written by quill and inkbrush, unlike Valyrian. Using @dedalvs ‘s wonderfully crafted High Valyrian and its phonology, as well as the phonologies of its descendant tongues in Astapor and Meereen, we can construct the following statements about Proto-Braavosi Low Valyrian:

no [r̥] (merged with r)

no [ʎ] (pronounced instead as [lij] or simply as [l] based on word context)

no [ɲ] (pronounced instead as [nij] or simply as [l] based on word context)

no long vowels (merged with short vowels)

the “gh” sound ([ɣ ~ ʁ]) is present in Proto-Braavosi, but does not seem to persist into modern Braavosi as we will see

Based on the attested spellings of the Braavosi names (factoring the fact that it is filtered through a Westerosi’s ears), we can extract the following information.

Consonants: l qu f g n t r y/j s d b sh th c/k/ch q m z ph h

Vowels: a e i o u y

Diphthongs: aa (Braavos), ae (Baelish), ay (Prestayn), ey (Jeyne, Wendeyne)

Since ph and f seem to be transcribed as distinct (such as in the name Phario Forel) they seem to be phonologically distinct sounds and not simply allophones. Thus, ph can either be an aspirated stop [pʰ] or a bilabial fricative [ɸ]. Since no unvoiced ‘p’ is represented, let us say that this is an allophonic variant of \p\ in Braavosi speech, transcribed by foreigners as “ph.” The “ch” in Tycho Nestoris could be an affricate [t͡ʃ] or a [k]; the latter seemed more natural to me. The “qu” in Allaquo seemed it could simply be represented as [k] + [w] or [q] + [w], or otherwise a labialized [kʷ] or [qʷ]; I think it can be ignored when creating our letters, particularly as it is not attested in High Valyrian. The sound sh ([ʃ]) exists only in the name Baelish, which very well may be Westeros-ized by its speakers, seeing especially as the sound does not exist in High Valyrian; we will thus treat it as an allophone of [s]. Finally, “th” is used to spell many Braavosi names (Uthero, Otherys, Lotho); this may be interpreted as a fricative [θ] or simply as another spelling of [t]; for the sake of simplicity, we will represent this allophone (if it is even an allophone at all) as another variant of “t.” Thus our final consonant inventory is as follows:

Consonants: p/ph b t/th d k/c/ch g q gh* s/sh f v/w z m n l y/j r h

*gh = Proto-Braavosi only

Or, represented in an IPA chart:

Apart from the loss of distinction in vowel length, there are two changes of note. One is that the rounded close front vowel [y] in Valyrian has shifted to an unrounded close central vowel [ɨ] in Braavosi. Furthermore, although not represented in writing, the vowels ɛ and ɔ are found in Braavosi speech (basically leaning hard on the medieval Florence/Italian parallels).

We are left with the following vowels.

(For context, here is modern Italian phonology lol.)

As for diphthongs, I won’t elaborate too much except to say that they are simply written using a combination of vowels (and the semivowel j/y), though their spelling patterns don’t always match onto their pronunciations. This post dwells little on orthography, but I think with more than 400 years of history the Braavosi script will have had time to develop concrete spelling patterns and crystallized standards which no longer reflect modern speech (though due to the somewhat egalitarian economy and political systems of Braavos, at least compared to Westeros and the other Free Cities, I think the script will not have diverged too radically from “common sense”). For instance due to sound changes representing an older form of Braavosi, a name like “Baelish” would likely be spelled something like “Bayelis,” with the spelled cluster “aye” represent the name.

I think there are two sound changes at play: one from High to Low Valyrian led to the loss of diphthongs (ae => e, so Daenerys => Denerys), and the second one from Low Valyrian to Braavosi which led to the elision of “y” between vowels(aye => ae, so Bayelis => Baelis/Baelish).

Script

With the phonology and basic history of Braavosi speech outlined, we can present the final writing system of the language, which I show in my next post:

https://www.tumblr.com/greenbloods/722222867516915712/the-idea-of-a-braavosi-alphabet-has-been-churning?source=share

Though it is bog-standard for fantasy scripts, I decided to make the writing system a bicameral alphabet, as it would best showcase the aesthetics of the script. I also wanted there to be a feel as if there were some far-back connection between Braavosi and the alphabet of the Common Tongue of Westeros (they would simply be using the Latin alphabet), which is also why I decided to make the “o” letter a blatant imitation of our letter O. The letter f is derived from the letter p as a visual reminder of the “newness” of the letter

Keep in mind that the script is only a snapshot of written conventions in one medium during one period of time, and there may be many variants for the script as well.

#yeah ik ik bicameral scripts get some flak but i think it works#braavos#valyrian#high valyrian#asoiaf#game of thrones#neography#david j peterson#linguistics#my posts

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

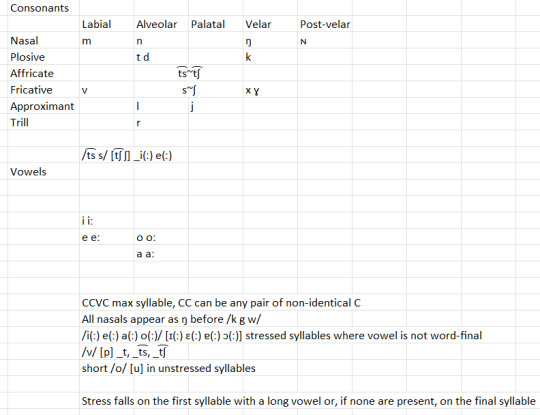

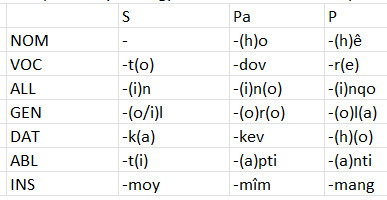

so I made a language where the consonants have daily pileups and the noun cases hate you

H̵̫̰̤̝̣̥̻͍̘̱̰͎̭̅̏̽̃͐̃̊͂̐̕͜͜͝ẽ̴̖̾r̶̨̯͌ę̷̨̛̛͎͔̰͓̹̠̣̦̝̻̞͔͇̔̈́͒̆̆́̆̽͘͝͠ ̵̛͍̞̲͔̺͓̗̞͉̘̻͆̏̽̄w̷̡̧͚̠̟͉̳͇̼̯͗͂̾̄͝ë̸͍̹̟̬̩̗̹̼̩͇͇͈̇͌̂͆̒̃̕̚͘ ̸̳̫͍̖̙̬̮̫͚̻͙̱̲̍̈́͋͌̑͑g̵̛̪̼̻͔̜̮͑̈̓͐̋̊̏̄̒͊̚ǫ̶̡͕̗͕͕͍̟̯̞͇̂͊̈́̓̀͗̃̎ ̶̢̛̠̦̣̝̩̖͎͈͚͊̒̄̌̒̃̀͊͂̍͊̽̈́ͅą̸̛̣̳̫̣̱̫̘̔̏̈̒͠͠͠g̸̢̡̖̟̝̠̲̤̙̣̳̣͓̰̃̒a̶̛̛̬͛͆͒̀̃̾̇̐̈́͒͌̋i̵̝͚̩͍̤͚͐̍́͐̀̆͑̔͌̽͗̚͠͠͝ň̶̢̡̛͙͎̿͒̍̔̐̕͠͝!̷̙͓͓̭͖̝̔̍̀̍̍̑̿̍̈́̏͌̓́

Want your brain cells boiled? you've come to the right spot, because same apparently.

This post is about my latest linguistic creation, Câynqasang [ˈt͡sɐːjɴasaŋ]. It's an isolate, set in a fictional distant future near the outer edge of the Milky Way. This one comes with an in-universe linguistic fringe theory linking it to Scots of all things and trying (very falsely) to frame Old English as Proto-Milky-Way. That theory is bullshit, but the language does in fact happen to have a few dozen loan words from English, which has been kept around for diplomacy across all the millennia somehow.

Yeah. It's weird. Also, as much as I have and will shitpost about it, I'm super proud of this one. It's efficient in ways English isn't, and clunky as fuck in other ways English isn't. It's got all kinds of weird irregularities. There's loads of stuff I have to work around a little bit to translate directly, and a lot of beautiful metaphorical extensions and derivational morphology and so on. I really like this one. Though it can sure be obnoxious to use, as accustomed to not-this as my brain is. One of these days I might fuck around and learn it to fluency. One of these days.

Let's get into this.

PHONOLOGY

Yeah.

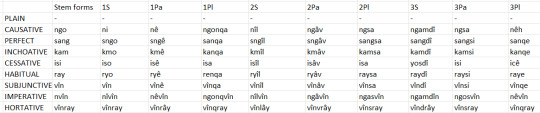

So if you're familiar with this kind of stuff, you might've caught that the first phonotactic rule means that any combination of consonants is allowed in the onset of initial syllables. This is not consistent across all speakers, in fact being one of the major sites of dialectical variation in Câynqasang, but it does mean that many speakers have, for just one of the wilder examples, ngsa [ŋsa] as the third-person paucal and second-person singular forms of the causative auxiliary verb. Many speakers shift nasal or liquid initials to syllabic consonants, i.e. in this case, ngsa [ŋ̍ˈsa], but that's a dialect thing and not within the main scope of what I'm covering here (though my recordings will likely have many of these realized as syllabic consonants). Also, this doesn't really happen with /j/, which just becomes the vowel /i/ in those situations.

Aside from that, the only properly wild things are the uvular nasal with this small of a consonant inventory and the absence of labial stops other than as allophones of /v/ before the voiceless alveolar stops and affricates. The rest of what's going on is some stress variations and palatalization, basically.

I'll spare an analysis of Câynqasang's phonological evolution here, but suffice it to say that the syllable structure has become far more complex, and that *q, *h, and the old central vowels give rise to considerable irregularity in some grammatical structures by the modern language, ca. 52: 8639. So expect some surprises. For one example of that happening in a noun, the word so means "hard vacuum". (Culture is spacefaring and has been for actual geological timespans, so it's an old, common term.) Because of various sound changes, this comes from *seqɞ; e was lost because short vowels before a stressed syllable are usually lost, short ɞ became o, q was lost, and so on. But this one gets weird with any suffix. Take for example what happens when the instrumental case is applied. In the protolang it would be *seqɞ *seqɞbuj, but through the same set of sound changes, the instrumental case form in the modern language is semuy [ʃeˈmɔj]. The vowel, and in this case thanks to the palatalization, the consonant as well, mutates. Another result of all this is visible in a derived term, using an affix whose meaning I'll descrive as ḻ̷̍i̴̼͛v̵̭̓ḭ̸͌n̶͙͂g̴̹͂, sehîng [ʃexɪːŋ] "dangerous extradimensional entity". In this case *q surfaces as /x/ because it was between two vowels and *o was lost. Suffice it to say that what I'm going to outline later as the grammar is kind of just the "regular" rules, and some crazy shit goes down in some roots including this one.

ORTHOGRAPHY

Câynqasang has two writing systems in modern use. For the purposes of this post, I'll be focusing primarily on the Latin alphabet system; someday I will make a follow-up post about the other system, which is in declining usage in-universe.

In both cases, most relevant today in the Latin alphabet, Câynqasang shows some considerable historical spelling, mostly resulting from the palatal series and central vowels in the protolanguage, though there are some other quirks that will quickly become visible in examples. I'll list the "regular" rules and then explain exceptions.

Modern Câynqasang uses the circumflex accent to mark long vowels. There aren't really exceptions to that. Anything with a circumflex means the vowel is long.

The regular forms are as follows:

/m n ŋ ɴ t k d s~ʃ x ɣ v t͡s~t͡ʃ l j r i iː e eː o oː a aː/ <m n ng nq t k d s h g v c l y r i î e ê o ô a â>

However, long /iː/ is sometimes also written <û>, and short <u> and <o> appear for short /o/ in fairly similar proportions regardless of stress.

Also, when /v/ surfaces as [p] before alveolar stops, it is often (not always) written <p>.

/ŋ/ sometimes is written as <ny>.

On rare occasions, /m/ is written <b>, but this is falling out of use.

Sometimes ɴ is written <mq>.

Also, in some environments where a historical voiced fricative has been lost neighboring a nasal, the former fricative is still present in writing, i.e. sumga [suˈma] "hormone" .

So that's pretty rad. Now let's get even wackier with it.

GRAMMAR

Main word order is subject verb object, with descriptors typically following what they modify aside from converb clauses, which vary in position. Articles precede the noun. Auxiliary verbs precede the lexical verb and carry TAM and person marking, while main verbs are marked with a participle. Relative clauses are marked using a pronoun.

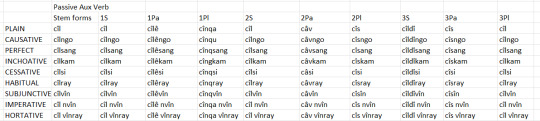

NOUNS

Câynqasang nouns mark for singular, paucal, and plural number and take seven cases. Here's a table of the regular forms:

The plural dative is either -h or -o depending on the presence of a final consonant in the root, or -ho in some nouns with final nasals or approximants or in some short vowel only roots. The paucal allative and genitive and plural genitive change considerably depending on where the stress falls in the root. If the root is all short vowels they'll take that -CV form because of the final stress, and the final vowel in the root will typically be lost; if there's a final long vowel it's just going to be the consonant.

It's also worth explaining some details about how each of these cases works; there's a bit of weird variance with them in addition to the fact that all of them sometimes appear marking the subject of the sentence.

The nominative is the unmarked case, common in both subject and object. It might make more sense to call it something like nominative/absolutive for that reason; there isn't really an accusative. Examples: i ongdo = the seed; yi ongdoho = these several seeds; nê ongdohê = these (many) seeds

The vocative is typically a way of calling out to something or someone like "O gods" and so on, or indicating that something is addressed to something or someone. In these uses, an article differentiates between such cases, i.e. Rayelto = "Hey, Rayel" vs. i tarto = "Addressed to this summit". The latter use is far more common in situations like correspondence or formal speech. Additionally, it's used as part of a naming convention for spacecraft and similar vehicles, i.e. i Galcît, a name referencing the galcî, a sort of balloonlike plant that hovers in the sky like a hot air balloon in large clusters for most of its life and is native to one of the three life-bearing worlds in the system where the language is spoken, known locally as Ulîtu. Additionally, the vocative case is used in imperatives where no other case marking is present on the subject, i.e. îlto kaylisûl i amdî! = 2S.VOC explain-2S DEF.SPEC 3S "Explain this!" (In the formal register, this same phrase would appear as îlto nîlvîn kaylsetadêv i amdî!; the auxiliary verb is not mandatory here in the informal register.)

The allative is a prepositional case referring to motion towards or into something or, especially if less permanent i.e. not referring to landforms, anatomy, and so on, location at something. Examples: ve tongin dênysumin = DEF.NSPEC transformation-ALL beautiful-ALL "towards a beautiful transformation"; Vo nrêdti ômdrây îdêv i Hîvin-ôyvêltêvusin = INDEF.NSPEC war-ABL NEG.HAB.3S live-PTCP DEF.SPEC city-ALL unbreakable-ALL "No war lives in Ba Sing Se" (lit: "the unbreakable city"; I tried to calque it). The allative case is additionally used as a subject marking for motion away from the "object" of the sentence (it's funky, but that's how it operates syntactically) in motion verbs and for negative volition in stative and action verbs. Examples: îlin nîlvîn cudêv! = 2S.ALL IMP.2S go-PTCP "Go away (from me)!"; mon mtâmtûlvu mka = 1S.ALL cut-PST.1S 1S.DAT "I have accidentally cut myself". (mtâm- "to cut" here is a stative verb, by the way. That's why the second pronoun here takes the dative. The dative is not necessary in the informal register here, and sometimes poetic registers that otherwise lean into formal speech will play fast and loose with this. Also, this kind of thing is the proper way to construct reflexives for stative verbs.)

The genitive is most often used as a possessive, i.e. lâmhu mol = leg 1S.GEN "my leg". However, it's also the main way of constructing reflexives for action and sensory verbs, i.e. sro mândengsa = 3Pa.GEN blame-3Pa "they (several) blame themselves".

The dative case is most often used for indirect objects, i.e. cdânyvu nâ lâh amdûk = give-1S DEF.NSPEC.P bread 3S.DAT "I gave some loaves of bread to them". It is additionally used to mark the subject of sensory verbs when the sensation is "passively" taken in as opposed to if someone is "actively" looking for something, i.e. mka sîtûlvu ven sedon = 1S.DAT see-PST.1S INDEF.SPEC spacesuit "I happened to see a spacesuit".

The ablative case is a prepositional referring to motion out of or away from something, sometimes to a more static presence outside of something. It can also refer to the source of something. Example: mon cumo Anqêsyat = 1S.ALL go-1S Anqêsya-ABL "I am leaving from Anqêsya (a city)". Additionally, the ablative case can mark the subject of a motion verb to show motion towards something, i.e. mti kenymo = 1S.ABL come-1S "I am coming".

The instrumental case indicates benefiting from, using, or accompanying something or someone, i.e. mon cûlvu Ancimoy = 1S.ALL go-PST.1S Anci-INS "I left with Anci". The instrumental also marks the subjects of stative and action verbs to show "positive" volition, i.e. the intent to do something, and sensory verbs to show that the sensation was actively sought, i.e. moy sîtûlvu i sedon = 1S.INS see-PST.1S DEF.SPEC spacesuit "I found the spacesuit", sîm lamnyutûsa mka = 3Pa.INS calm-3Pa 1S.DAT "they (several) took steps to calm me".

So that's noun cases, and a window into something I'll discuss again in more specific detail later that verbs do. Subject marking is wild.

Let's move on to the articles you'll doubtless have noticed by now. They're kinda funky.

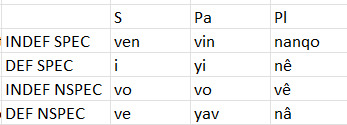

So, they agree in number to the noun they're attached to. There's a definite and an indefinite.

And a specific vs. non-specific distinction that applies to both.

From top to bottom, indefinite-specific refers to a defined object or set of objects but it's not clear which one, i.e. ven cnguy = INDEF.SPEC bird "a bird". It's not unlike the English indefinite article. Definite-specific refers to a defined and clearly specified object or set of objects, i.e. i râkum = DEF.SPEC tree "the(/this/that) tree". It carries the senses of the English definite article, but also a couple of other determiners. But unlike English determiners it can't stand alone, so if no noun is specified then a pronoun must be included, i.e. i amdî = DEF.SPEC 3S "this/that". Indefinite-nonspecific refers to an indefinite object without subset or other context, not unlike the English term "any", but again it must refer attach to something in the way an article does, i.e. vo hâptôuy = INDEF.NSPEC person "anyone". Definite-nonspecific refers to any member or members of a defined subset of objects, i.e. ve vênyay = DEF.NSPEC laser.rifle "one of these laser rifles. English doesn't have a single term for this, but "one of these" is a solid direct translation. And in this case, though it's defining a subset of many items, the noun must be singular, unless the article is paucal plural in which case you're referring to more than one of a subset. The noun would then agree to the article.

Also, here's a quick table of all the personal pronouns.

It's rare in the modern language that the allative case pronouns are used in the same capacity as the old accusative case, but some older speakers will do this in relative clauses and converb clauses with objects and so on. This can also be a more common feature in some dialects. Also, Câynqasang lacks gendered pronouns.

ADJECTIVES

Adjectives are relatively simple. They follow what they modify and agree in case and number if it's a noun, i.e. Ôdamoy ôtahiraymoy vuynomraymoy nola = mandate-INS self.destructive-INS cursed-INS 2P.GEN "By way of your accursed mandate"

Alright. Let's see what other madness this language has to offer.

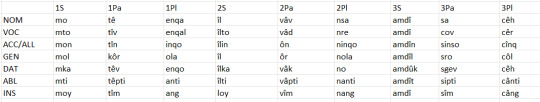

VERBS

First I'll cover what you can do without needing an auxiliary verb. You can do imperfective, past, present, and future without an auxiliary verb, and there is a paradigm for person-marking, agreeing in person and number, singular, paucal, and plural, to the subject.

The imperfective was marked in the protolanguage by reduplication of the first syllable of the verb stem. However, sound changes have in some cases severely obscured that relationship over time, and it's rather common that a random vowel will appear in the reduplication that isn't present in the perfective stem anymore, i.e. mco- to rot > mamco-. Often, not always but often, that same vowel will be retained when the verb takes an ending, i.e. masvâv = rot-2Pa "y'all (several) rot".

Here are the endings for person marking including simple past and future. Bear in mind that I include two of each category, but the endings are the same; this is mostly to remind myself that the imperfective exists and is reduplicative. I make these posts with screenshots of my own kind of messy documentation.

Again, some of them change with the stress patterns. The alternation between m and v in the first-person singular is because it was *b in the protolanguage, and what the modern reflex is changes based on stress patterns in the same way as the vowel does, becoming /m/ in stressed syllables and /v/ elsewhere.

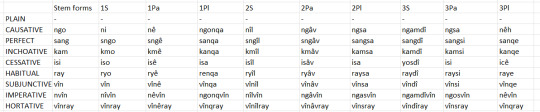

For everything else, you need auxiliary verbs.

I'm going to share the sum total of those in the form of several tables, one set for the formal register and one set for the informal register.

These are the formal register auxiliary verbs. Notice how the other forms have compounded or juxtaposed with the passive and negative auxiliaries. Most of these forms have by now lost other semantic meanings entirely and serve only as these auxiliaries.

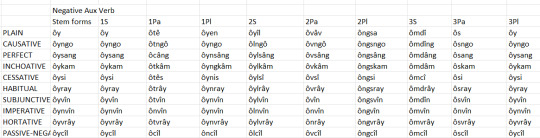

Here are the informal register ones:

In these, the ones that were juxtaposed are blended together instead and many of them have eroded away some syllables, so that just about all of the informal register ones are disyllabic at most.

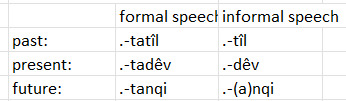

When these are used, the lexical verb is marked with participles. I'll include the table I have in my documentation that has the formal and informal register forms of these side by side:

Notice again that a syllable tends to be eroded in the informal register. This notably does not happen in converbs even in the informal register, even though the participles serve double duty as-is for three of them. Anyway, that's participles.

So, with all of that information, we can finally construct a sentence using other TAM than just simple past, simple present, and imperfective. The imperfective, by the way, still marks on the lexical verb when these are used. Example: ômdîn agaltîl nê cêh = NEG.3S IPFV-eat-PTCP.PST DEF.SPEC.P 3P "They should not have been eating those"

We also have to touch on the four classes of verbs, though. This is what determines how those subject case-marking paradigms I was discussing earlier operate. These classes don't strictly follow what you'd expect, both because Câynqasang just handles some concepts differently and because semantic drift makes them funky sometimes. For one example, tkâranco- "to sabotage" seems like it should be an action verb, but it's a sensory verb, because it meant "to deceive" in the proto language. That's one of the wilder ones.

Stative verbs deal with states of being. Their subjects take the nominative case, the vocative in imperatives where the others aren't present, and for volition marking, the instrumental to mark a willing subject and the allative to mark an unwilling one.

Verbs of motion deal with motion, either physical or in some cases, metaphorical. Their subjects take the ablative for motion towards the object or destination, the allative for motion away from the object or destination, the nominative for unclear direction or motion that doesn't change distance, and the vocative for imperatives that would otherwise be nominative.

Sensory verbs are the only verb class that can't take a nominative subject. They take the dative case for passive perception, the instrumental case for intentional perception (so a slightly different volition paradigm than for statives), the genitive case for reflexives, and (sometimes) the vocative for imperatives. The vocative is in somewhat less common use in the modern time.

The class of action verbs contains all other verbs. They take the allative to mark unwilling subjects, the instrumental to mark willing subjects, the nominative when volition can be assumed from context, the genitive for reflexives, and the vocative in some imperatives.

These categories are something a learner would mostly just have to memorize. Like, there are some vague patterns you can pick up from semantics, but they're very far from consistent and it doesn't work the same way you'd think it would in English.

One last little footnote before we move on to converbs, to negate something other than a verb, simply use the stem form of the negative auxiliary following it.

Alrighty.

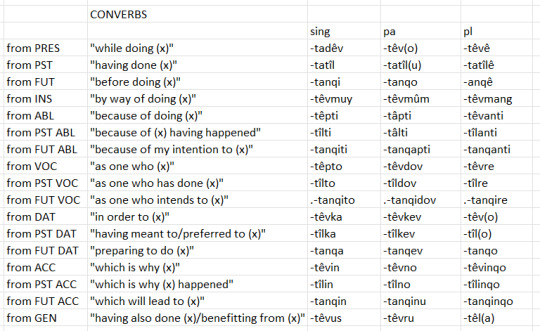

CONVERBS

I'm not incredibly familiar with the typical nomenclature for these, so I list their etymologies and meanings to the left of the table here:

Converb clauses most often precede the main verb phrase. If a converb is used, also, a separate participle need not be if the clause involves an auxiliary verb. They are derived from participles.

Example: Ye i côl sanqe kamesîtêl, yâkînghê ola lamnyunqicêh = And DEF.SPEC 3P.GEN PERF.3P happen-CONV.GEN.P soul-P 1P.GEN peaceful-FUT.3P "And having felt all of these things come to pass, our souls will know peace".

So those are pretty rad.

RELATIVE CLAUSES AND INTERROGATIVES

Relative clauses are constructed with the relative pronoun (below) and, where relevant, an interrogative.

Relative clauses can either precede or follow the main clause, but in either case the relative pronoun agrees to the subject of the clause in number. Also, when they involve an interrogative (below), it precedes the relative pronoun.

Example: gôv nâs sâyin nola cîldîsang rircâmtatîl, ang onqûnqinqa ven nymûm sunyul. = where REL dust-ALL 2P.GEN PASS.PERF.2P IPFV-imprison-PTCP.PST 1P.INS build-FUT.1P INDEF.SPEC meeting.place love.GEN "where your ashes have been imprisoned, there we will build a meeting place of love."

Questions are constructed with one of these interrogatives immediately preceding the verb or, if the question is related to the nature of the subject or object, in subject or object position. Examples: galtûlûl kay? = eat-PST.2S which.P "Which ones did you eat?";

IMPERATIVES

Imperatives are constructed somewhat differently in the formal register than in the informal, in at least some cases. The subject of the sentence often takes the vocative case, but where other subject case marking is present, it can be omitted. If the vocative is present, in the informal register the imperative auxiliary verb is not required; in the formal register, the auxiliary verb is always mandatory. Here I give three examples assembled from elsewhere in this post, first one using an allative subject, then the same sentence in the informal and then formal registers:

îlin nîlvîn cudêv! = 2S.ALL IMP.2S go-PTCP "Go away (from me)!"

îlto kaylisûl i amdî! = 2S.VOC explain-2S DEF.SPEC 3S "Explain this!" îlto nîlvîn kaylsetadêv i amdî! = 2S.VOC IMP.2S explain-PTCP DEF.SPEC 3S "Explain this!"

That's just about it for grammar. Now for a brief discussion of derivational strategies.

DERIVATION

Most derivation involves a set of suffixes, most of which a screenshot will sufficiently explain, but I'll go into more detail about a couple of these.

The profession derivational produces a set of nouns which in the formal register double-mark number, i.e. sînqangâtmoy = pilot.INS, sînqangârmang = pilot.INS.P and in the informal register have an entirely separate paradigm derived not from the regular one but from the historical imperative, present in the protolanguage but no longer functional. In the informal register all noun cases will attach to these nouns in the singular form, i.e. sînqangât "pilot" but sînqangârmoy = pilot.INS.P

That -îng(i) suffix often has fairly abstract meanings, though it can very much function as simply making a term for a plant or animal. From the same suffix you get such things as nâlkîngi "rabbit" from nâlk- "to flee" galîng "dissociative state" from gla- "to sleep", kalîng "waterfall" from kali "water", râkmîngi "the mood or atmosphere of a remote, dense forest" from râkum "tree", teyresnîng "a type of extradimensional entity that operates by ensnaring victims' minds and molding them to its will" from teyrsin- "to be uncertain", and so on. It can get fairly wild.

The suffix -uy can also create a term for a plant or animal, as in cnguy "bird" from cong "air", though it typically ends up as a type of person.

So that, in a nutshell, is Câynqasang. I'm still developing it, but nearly all of that work anymore is happening in the lexicon. I'm really proud of this one. As always, I'll wrap this up with a couple of fun translations. And, this time, also a rather long original work in Câynqasang.

TRANSLATIONS

Cave Johnson rant:

Nre dês sanqe cîl ngûyinytinyutêv ûyûngamang nûlul gônîngudêv: cdânyvu hâyrunîhê mûlîhê ye vâyâhê [nre dɛːʃ saˈɴe t͡ʃɪːl ˈŋɪ��jiŋtiŋuteːv ˈɪːjiːŋamaŋ ˈnɪːlul ɣɔːniːŋudeːv ˈt͡sdɐːŋvu ˈxɐːjruniːxeː ˈmɪːliːheː je vɐːjaːxeː]

2P.VOC REL.P 3S.PERF PASS.3P inject-CONV.PURP DNA-INS.P mantis-GEN.P volunteer-PTCP.PST | give-1S message-P good-P and bad-P

"To you all who have volunteered to be injected with the DNA of mantises: I give good and bad messages." I vâyâ: ang cingvûnenqa sînin ôykîvringtatîlin nê ûngsânê [i ˈvɐːjaː ɐŋ t͡ʃiŋˈvɪːneɴa ˈʃɪːnin ˈɔːjkiːvriŋtatiːlin neː ˈɪːŋsaːneː]

DEF.SPEC bad | 1P.INS delay-1P day-ALL unknown-ALL DEF.SPEC experiment-P

"The bad: We delay those experiments until an unknown date." I mûlî: nyuenqa ven ûngsâny mûlu mûlu; hînûnqinsa ven lvêng nûl-hâptôuymang [i ˈmɪːliː ŋueˈɴa vɛn ˈɪːŋsaːŋ ˈmɪːlu ˈmɪːlu | ˈxɪːniːɴinsa vɛn lvɛːŋ nɪːl ˈxɐːptoːujmaŋ]

DEF.SPEC good | have-1P INDEF.SPEC test better REDUP | fight-2P.FUT INDEF.SPEC army mantis-mantis-P

"The good: We have a much better test; you will fight an army of mantis people." Ngasvîn ûmqemdêv ven înîv ye mîdêv i tânyôy sîm. [ŋasˈvɪːn ˈɪːɴemdeːv vɛn ɪːniːv je ˈmɪːdeːv i ˈtɐːŋoːj ʃɪːm]

IMP.2P carry-PTCP INDEF.SPEC rifle and follow-PTCP DEF.SPEC line yellow

"Take one of these rifles and follow the yellow line." No mgnônqinsa nâs gî i ûngsâny nyamnyumdî. [no ˈmŋɔːɴinsa nɐːs ɣiː ˈɪːŋsaːŋ ŋamŋumˈdiː]

2P.DAT know-2P.FUT REL when DEF.SPEC experiment start-3S

"You will know (without seeking) when the experiment starts."

Recording of the above. It's kinda mid tier but it'll work.

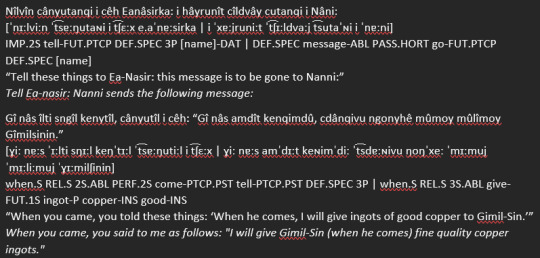

Partial translation of the Ea-Nasir complaint tablet:

And a link to an original work. It's long as fuck, so putting it directly in this post would feel a bit ridiculous.

Anyway, I really did do the thing, didn't I.

Cheers!

#conlang#cave johnson#ea nasir#i really made a wild one this time didnt i#i love this#im proud of this one#one day i will shatter my brain by learning this crazy language to fluency >:3

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm posting so much about linguistics lately as if that's even remotely my field i don't know why. i guess i think about it a lot. ok, basic yup'ik orthography intro so that i can complain:

there's a series of stops, p t c k q. these sound like what you'd expect (c is ch/ts depending on context) & don't contrast based on voicing

there's a series of voiced fricatives (sensu lato, some of these are approximants but they work the same) v l s y g r (ipa v l z j ɣ ʁ). these are doubled (vv ll ss gg rr, ipa f ) to denote a series of voiceless fricatives (the voiceless equivalent of y is ss) when the voicing isn't predictable based on other rules

there's three voiced nasals, m n ng. they have voiceless counterparts written ḿ ń ńg (again except when the voicelessness is predictable). this is kind of sad because it breaks the double-to-make-voiceless rule but it's not the worst thing in the world. i don't see why it couldn't be mm nn nng, as far as i can figure out phonological rules keep this from causing any ambiguities but like. whatever, i guess 'nng' is kind of ugly

there's also another three-to-six more sounds that i didn't tell you about! these are all rare, similarly to the voiceless nasals. they're rounded versions of back consonants. i'll give you them in ipa: kʷ qʷ ɣʷ xʷ ʁʷ χʷ. of these, ɣʷ, xʷ & ʁʷ are phonemes & present in all dialects afaik, χʷ is an allophone of ʁʷ & not present in all dialects & kʷ & qʷ are... i don't know? they're not mentioned in the grammar i have but they are mentioned in the dictionary by the same author from a year earlier. i guess they're rare & dialectal, probably. anyways they're obviously not written like that in practice, that would be silly & make writing them completely untenable on any normal keyboard. instead they're written like this:

u͡k u͡q u͡g w u͡r u͡rr

WHYYYYYYYYYY. WHY ARE THEY WRITTEN LIKE THIS. WHY?

ignoring the first two weird ones that i don't understand & the last one that's allophonic & therefore not ever actually written they're u͡g w u͡r. this is just........................ so completely baffling to me. why are they like this??? this isn't like, a purely technical orthography, it's supposedly designed to avoid diacritics & it's thee orthography in use today. i guess it was designed pre-computers more or less so the typing difficulty wouldn't have been such a big problem, but like... still... it's so bad!!!! "u͡gasek" is a two syllable word that starts with a consonant... it should not be that way... there's no other w used in the orthography, why could labialization not be indicated by adding a w? i guess it'd leave you with a trigraph ggw which is weird but... it's not remotely a common sound anyways, it's definitely better than having random fucking ligatures!!! & for that matter vouldn't the voiceless nasals be indicated by adding an h afterwards? there's no h anywhere either. i'm sure there's some kind of reasoning here. dialects??? maybe??? it's just completely incomprehensible to me

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I watched the latest episode of Langtime Studio, and wanted to create a version of my own of the phonemic inventiry they made, because it seemed very interesting. here is the process I went through to come up with it:

The original inventory:

Consonants

First thing I did was to rearrange the table to include a seperate row for pharyngealized stops, and add seperate columns for the labialized consonants.

3 things that jump out to me first:

There are pharyngeal labial and alveolar stops, but no velar or uvular. I think collapsing th uvular and velar columns under "dorsal", and leaving a note for future sound changes that the fricatives and pharyngealized velars are technically uvular is a good way to "fill the gaps" and make the table more compact.

I don't think it's that important for the plain unvoiced stop to be written as aspirated, just another note for the pronounciation guide like the uvulars.

because labialization comes in this phonoloy as a set I think it's fine to have /ʟʷ/

I also changed "alveolar" to dorsal, because /ɹ/ can be either alveolar or postalvelar, and also that wording fits the vibe I'm going for, more on that later.

After those changes we end up with this:

After that I got rid of the pharyngeal fricative, because it's out of place, with pharyngealization being a feature of stop only, other than it. I also think that it's not very needed from a sound change point of view - I think that the dorsal fricative can make anything that the pharyngeal one could.

Using the terms "dorsal" and "coronal" reminded me of Australian languages, and that reminded me of how they are usually grouped there into a natural class of "peripheral consonants" that share similar features. That gave me the idea of making labialization a feature that is exclusive to the periphral POAs. There are many labio-velar consonants, and there are more "velo-labial" ones than labial alveolars (/mʷ w/ vs /ɹʷ/, so I think it fits.

That decision removes /ɹʷ/, and gives us /bʷ bʷˤ ɸʷ βʷ β̞/

Because the distinction between /β/ and /β̞/, /βʷ/ and /w/ isn't very strong (and I can't really hear it, I dropped the fricatives.

I also dropped the unvoiced bilabial ficative, with the idea that each POA some of these 4 features - voicing distinction in stops, nasals, fricatives, and labiolization:

Dorsal is the "Strong" POA, having 3 out of the 4 - labialization, voicing of stops, and fricatives. (I also remember Jessie saying that she feels like the dogs will use the back of their tongues more, so dorsal being strong here fits that.)

after that is Bilabial, with 2 out of 4 - labialization and nasal vowels.

And last but not least is Coronal, the "Weak POA", having only one of the 4 - Voicing distinction in stops but no labialization, fricatives or nasal stops.

That leaves us with a final proto-consonat inventory of 25* consonants:

*I thought about dropping /β̞/ aswell because I feel like it's not that distinct from /w/, but I'm not 100% sure either way.

Vowels

There isn't much to say in this section. Jessie suggested a 4 vowels system which I think is a neat idea, so I think this system is a nice fit:

With all the labialized and pharyngealized consonants I don't think it'll be hard to get a lot of back vowels, and having 2 front vowels can give us a lot of front round vowels which I like.

So yeah that's it! I hope you liked it, and @dedalvs and @quothalinguist if you see this I hope it doesn't come off as a FixEd uR aRT sort of thing, but as me participating and sharing ideas on stream! (which I can't really watch live because of time zones, oof)

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phonological terminology is confusing

Like it’s so hard to remember. Which one is debuccalization? What’s the difference between labiovelar and labialvelar? Unless you speak Greek and Latin, it’s so confusing.

So I propose: IPA 2.0, with expanded mnemonics.

Labial has a labial sound in it, so it’s fine. But to help people remember dental, we should pronounce it ðental. Alveolar has the L to remind us, but postalveolar misleadingly has lots of alveolars in it, so poʃtalveolar’d be better. We’ll have ɻeʈroflexion. Gone is palatal, in favor of paʎataʎ. Velar should be replaced by veʟar. Uvular lost for the superior uvulaʁ. Labialvelar becomes lag͡bialvelar.

and not just PoAs… debuccaliɦation. Labʷialization. Hell, bring in the phˤaryngealized consonants. ɬateral fricatives. Everything.

Have a good day everyone!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, I have The Itch™ to create some English Words That Never Existed Despite Sounding English for my campaign, and I've had Tumblr eat this post three times, so we are speedrunning it.

First, you'll need equipment:

A Linguistic History of English, Volume I: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic by Don Ringe.

A Linguistic History of English, Volume II: The Development of Old English by Don Ringe and Ann Taylor.

A Source of Proto-Indo-European roots or words. I use Wiktionary bc I'm a scrub.

If you don't have the money or library access to get either, both volumes of Don Ringe's Linguistic History of English are available on LibGen.

Great. Now we need to cover: What the fuck is Proto-Indo-European?, What the fuck is Indo-European ablaut?, What the fuck are these damn numbered 'h's?, how the fuck do you pronounce a 'ǵ'?

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed protolanguage from which a shit load of languages spoken all across Eurasia (before Colonialism proper) and was likely spoken six-thousand years ago on the steppe north of the Caucasaus, between modern Ukraine and Kazakhstan. It spread so far so fast that we have loanwords from Tocharian in Old Chinese. How many languages? here's an incomplete cladogram:

How far, how fast?

That far, that fast.

Next: Indo-European Ablaut. PIE had a system of vowel gradation that it would use to decline nouns into other cases, throw verbs into other tense or mood. The fundamental vowel of PIE is short "e", which can ablaut to nothing or to "o". It can also be lengthened. The typical ablaut for PIE is e-Ø-o. However, we often find 'a', 'ā', 'o' ans 'ṓ'. where we don't expect.

That's where Laryngeal Theory comes in! because of the screwy vowels, certain vowels popping in and out of existence, and miscellaneous unexpected consonant changes, linguists created a model that posits three laryngeal phonemes in PIE: h₁, h₂, and h₃. Their exact pronunciation is impossible to reconstruct, but we do know that they existed and the broad place of articulation due to vowel coloring effects. The first of the laryngeals is h₁, which appeared to be neutral, causing no vowel shifts when in contact with /e/, and only lengthens the vowel when following him; this one was very likely to just be "plain" ol' /h/. The next laryngeal, h₂, is decidedly not neutral and colors every /e/ to /a/ and /ē/ to /ā/; the pronunciation for this one could be the uvular fricative /χ/, or the pharyngeal fricatives /ħ/ or /ʕ/. Because of it's o-coloring effects, h₃ is often assumed to be labial; good candidates for the pronunciation on the ground , likely voiced labialized velar fricative [ɣʷ], with a syllabic allophone [ɵ], i.e. a close-mid central rounded vowel.Kümmel instead suggests [ʁ]. In cases where the exact nature of the phoneme cannot be determined, 'H' is used to denote the presence of an indeterminant laryngeal (seen a lot between "o"s, IIRC the PIE genitive plural ending is *-oHom, because we have two valid reconstructions from different lines, one as *-oh₁om, the other as *-oh₃om; since h₁ doesn't affect vowel quality and h₃ is o-coloring and is between two "o"s, either have the same effect in this position). Laryngeals are cool and PIE's daughters do cool things with them! The last thing we need to cover to get caught up enough to jump into just doin' some wordin' is explaining what the fuck is up with PIE's consonants. See, PIE has three series of obstruent consonants (sometimes called "plosive" or "stop" consonants---all three names refer to the manner of articulation: the tongue or lips completely occlude the oral cavity, preventing air from the lungs from escaping, allowing pressure to build before release), termed voiceless, voiced, and voiced aspirated. And that seems really straight forward! You have your [ p, t, k ], your [ b, d, g ] and your [ bʰ, dʰ, gʰ ] which is the same as the prior set but with a little puff of air after/during articulation! Except. That's wrong. In two big ways.

The first way is that that's not all the obstruents! PIE has a series of three "dorsal" consonants, of uncertain place of articulation. Traditionally, the dorsals consist of palatal, velar, and labiovelar consonants in each of the three consonant series: [ ḱ́, k, kʷ ], [ ǵ, g, ǵʷ ], and [ ǵʰ, gʰ, ǵʷʰ]. It's worse than that, though! See, we posited the existence of the palatal series because of the Centum-Satem Isogloss, where having these three sorts of "dorsal" consonants explained this split: "centum" languages merged the "palatal" and "plain" series, leaving the labiovelars distinct, whereas the "satem" languages merged the "plain" and labiovelar series together, leaving the "palatals" distinct, which were then assibilated (made into sibilant fricatives like /s/ or /ʃ/ or sibilant affricates like /ts/ or /tʃ/). We figured the palatal series had to be, well, palatal---because we already have a lot of living languages that take velar consonants to sibilant fricatives/affricates when palatized (Like English and nearly every Romance language).

But it's wrong! Like, much ink has been spilled over their actual realizations, but the consensus is that the palatal series weren't palatal. Not even palatized. What they were pronounced as isn't settled. One that I particularly like is that the "palatal" series were plain velar stops, the "plain" velars were actually uvular, and the labiovelars could have been either, giving us the dorsal series: [ k, q, kʷ/qʷ ], [ g, G, gʷ/Gʷ ], [ gʰ, Gʰ, gʷʰ/Gʷʰ]. This isn't agreed upon, but if h₃ is the labialized uvular fricative /χʷ/, then it would be weird to not have any uvulars anywhere else. But this isn't widely accepted, and since all my sources stick to the traditional orthography, so shall I. The second way the PIE consonant series is wrong is that there's good evidence that the voiceless, voiced, voiced aspirate labels are wildly incorrect. One big thing is that while /bʰ/ is common, /b/ is vanishingly rare. Which is weird! usually if you lose a labial, it's /p/, and if you lose a voiced obstruent in general, it's /g/. Others get into more technical reasons that I don't quite get. One popular reconstruction re-labels the series, voiceless remains voiceless, but voiced aspirate is relabels as (plain) voiced, and voiced as voiced glottalized. This has the really neat (for our purposes) effect of making Grimms law make more sense, as the "plain" voiced and voiceless stops become their respective fricatives, while the glottalized consonants become voiceless stops. Unfortunately this isn't widely accepted/used, and since all my sources will be using the traditional orthography, so will I. But keep it in mind!

And that's everything, I think? Next post we'll think of what kind of words we want to coin, what roots we want to work with, and what suffixes we will append to them before, and go through our first round of sound changes!

See you then!

#linguistics#PIE#proto indo european#conlanging#conlang#infodump#surprise cladogram#damn#prototoindoeauropeans sure got around#laryngeals are for real cool

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phonology: Places of Articulation

Last Post:

Okay! So

I want to apologize because I forgot to mention that I'd have to make the decision that phonology would be spoken. I just don't have any experience with a sign language (or languages in other media).

With that said...

Starting with Phonology won with 43%

Skip to the bottom if you just want to vote.

---

I typed out like three books on OT theory and explained the prosodic hierarchy. I think I'll spare the excruciating details because it's less digestable to frontload everything.

But suffice it to say, because of the nested nature of language, high order decisions about how you group things can affect how the individual pieces come into contact. It's kind of like atoms - the configuration of their electrons determines their chemical properties. Likewise, the converse is true; the chemical properties are determined by the configuration of electrons.

I kind of wanted to start from the top, because I thought that more accurately decided the sound of the language early. But it requires kind of knowing everything beneath it, in the same kind of way deciding to want water implies hydrogen and oxygen, while deciding to want hydrogen and oxygen could imply water, hydrogen peroxide, or so on.

I'll explain features, look at natlangs, sketch out a generalization of place, and ask the first question.

--- Information and Features

If we start with empty set, we can't really make much with it. The powerset, which is the set of all subsets or combinations of elements of something, of the empty set is just the empty set. It's not until we add a bit of information to that we start to get more information: the power set of {a} is {{}, {a}}. The powerset of {a,b} is {{}, {a}, {b}, {a,b}}. The powerset of {a,b,c} is {{},{a},{b},{a,b}{c},{a,c},{b,c},{a,b,c}}. Etc. Notice how fast the size of that grows: size 0 gives a power set size 1, 1 2, 2 4, 3 8.

Language use obeys something called Zipf's distribution. Basically, word use correlates inversely to how much information it encodes. This is probably straightforward; you use the word "is" a lot, but the more and rarer words you string together in a sentence makes it more likely you've made a unique utterance. So a little goes a long way.

For what it's worth, I've seen it estimated that most languages use around 8,000 to 20,000 unique words with reasonable frequency (perhaps, the vocabulary size of a fluent speaker of a language), with about 2000 words in daily conversation, expressable in about 500 to 800 unique roots (which generally correspond to unique feet minus one nucleus' worth of information) which in turn reflects inventory sizes around 20 consonants and 5 vowels large (note how 20 cons × 5 vowels × 20 consonants is ~= 2000 daily use words) . Obviously, some languages don't conform to these generalizations. And the generalizations could be wrong themselves but that seems to fit what seems to be about average from the studies I've read.

The unit of information in phonology is probably the feature. But features are like quarks in physics; they're confined to only appear in small bundles called segments. And sometimes features are incompatible, or neutralized together, creating inventories that aren't just x * y. Still, incompatibilities and neutralizations both *remove* possibilities from our total set, so our inventories are going to only be subsets of our big x * y early choice.

Vowels and consonants for some reason have different x * y s, and while not always the case, tend to inversely correlate in inventory sizes. So we'll arbitrarily decide to start with the consonants.

-- Some Minimalistic Natlangs

We're doing something naturalistic, so we should look at the Places and Manners of Articulation for the smallest languages.

Hawaiian has Labials, Linguals, and Glottals by Sonorants, Nasals, and Obstruents with an extra consonant at obstruent x glottal.

Piraha has just three kinds of obstruent with labial, lingual, and glottal places; likely also a single velar obstruent.

Central Rotokas has Labials, Coronals, and Dorsals, by a voicing distinction.

Obokuitai has just stops contrasting with fricatives at labial, coronal, and dorsal places, with an extra voiced coronal stop.

It seems that it's minimal to have 3 POAs and 2 MOAs.

Let's just start with place.

--- Generalizing about Place

Broadly place can be generalized into

labials, which don't tend to get submarked or split into subclasses

Coronals which can split into secondary manner distinctions based on flexing the front of the tongue and place distinctions

*** (roughly, front (dental, alveolar) and

*** back (postalveolar, palatalveolar, retroflex))

dorsals (palatals, velars, uvulars, glottals), which tend to split mostly on place (roughly

***front,

***mid, and

***back).

Exotic places (epiglottals, pharyngeals) do exist as well, but they often conspicuously fit into a hole in the chart in one of the other series. So they probably encode the same information phonologically, even if they're different phonemically. We can make the finer distinctions later.

---

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

You can also use this to create names that fit a certain sound.

Let's say that your language is supposed to be very sibilant. So a lot of s, z, sh, and zh sounds, and probably not as many sounds that require the lips (m, b, p, f, v, w).

So, instead of a vowel shift, we need to shift the consonants from these labial ones to something else. As for vowels, let's de-emphasize rounded vowels, though that is more pronunciation than spelling.

So, let's try...

M -> N or L

B -> Z

P -> S

F -> Sh

V -> Zh

W -> Th or T

U / OO-sound -> schwa

So some sample names:

Benjamin -> Zenjalon

Timothy -> Tinothy

Penelope -> Senelosy (e to y to prevent "looz")

Phillip -> Shillis

Beatrice -> Zeatrice

But then combine this with some vowel shifts as above...

Zenjalon -> Zanjelon

Tinothy -> Tenathe

Senelosy -> Sanilisy

Shillis -> Sholles

Zeatrice -> Zietrece

And now you have some names that sound like they fit within a language that sounds a bit hiss-like.

Name Generator: Vowel Shift

Swap each vowel with one of the suggested vowels or combos to generate names that feel like names, but aren't ones you'd see in casual use.

A -> E or O E -> A or I I -> E or O O -> I or A U -> Y or OE Y -> U or IA

For example:

Catherine to Cetharona

Benjamin to Banjemon

Daniel to Doneil

Justin to Jysten

Audrey to Eldraia

Joshua to Jashyo

Lucy to Lycia or Loecia

Nicole to Nocila

Jennifer to Jannefir

Irene to Erina

Timothy to Temathu

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

My main aesthetic goal for the Kyemuti languages is to have a lot of secondary articulations on consonants. I initially envisioned a three-way contrast between plain, palatalized, and labialized consonats (i.e. t tʲ tʷ), but I wasn't liking the look of it and labialized labial and coronal consonants are pretty rare cross-linguistically anyway. But I also liked the idea of having more variation on the velars and coronals than just palatalized/not palatalized.

So I started by throwing in a series of labialized velars (kʷ gʷ and maybe xʷ) which would be present before the palatalization stage, with the result that some of them would end up labiopalatalized (kʷʲ gʷʲ xʷʲ). This will have various results in the daughter languages (kʲ kʷʲ -> tʃ kʲ, kʲ kʷʲ -> tʃ tʃʷ).

Then I decided to add another series of coronals (t̺ d̺ s̺). These could be retroflexes, or reflect a dental/alveolar or laminal/apical distinction--it's not important at this point. What is cool is that this resolves another dilemma I had. I want the language to have a length distinction at later stages, but not earlier ones. So I thought about having /s/ drop out at the end of syllables and lengthen the preceding vowel, but I didn't want all branches to lose syllable-final /s/. Now that I have two sibilant phonemes, I can drop one and keep the other (which will later be dropped in some but not all daughter languages).

So I've got the consonant system for the proto-lang pretty much figured out. The vowels are still giving me trouble.

See, I'm starting out just before the palatalization becomes phonemic, and I was thinking of doing something like this:

i -> ʲi

e -> ʲe

æ -> ʲa

ø -> ʲo

y -> ʲu

a -> a

o -> o

u -> u

ei -> ʲiː

æi -> ʲeː

ai -> eː

oi -> iː

eu -> ʲuː

æu -> ʲoː

au -> oː

ou -> uː

I'm unhappy with this for a few reasons:

Plain stops before front vowels end up being pretty rare. I'm fine with there being a tendency in one direction but this is a little much.

I'm planning on dropping short /i/ and /u/ in most unstressed positions pretty early on, and under this system, word-final consonants will end up disproportionately palatalized.

As far as I can tell from looking at Index Diachronica, ø -> o pretty much never happens.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The History of Thai Dating App Refuted

Blaine Erickson, 2001. “On the Origins of Labialized Consonants in Lao” Archived 2017-10-11 at the Wayback Maker. Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. We have no doubts thinking that we spoke with real ladies, as communication doesn’t appear automated, over 95% of ladies had filled profiles and lots of photos were added. We haven’t talked to any female 24/7 however after talking for a week…

View On WordPress

0 notes