#and an adverb describes verbs (which are 'doing words' that show the action in a sentence)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I just started learning Thai so I’m interested. What is the difference between jing and jingjing? On your tags about favorite Thai words

oh! so in Thai, repeating an adjective turns it into an adverb.

in this case, jing is an adjective that means true or real or honest, and jingjing is an adverb that means really, trully, honestly. they're just my favourite Thai words because I like the way they sound lol.

my other favourite is ning, which doesn't have a perfect English translation but that you might recognise from My Engineer. it means cool as in (a person who is) cold, distant, or aloof, or alternatively calm and self-controlled. it's often used sarcastically when describing other people. ningning is an adverb that means something like carefully or calmly - you hear people saying "ningning!" to tell someone to calm down or take more care. kind of like "chill out!" in English lol. I like these because their English translations are so interesting! and because of RamKing and ai'Ning, obviously.

#oooh thank u i love talking about language!#also just to cover all bases -#an adjective is a descriptive word that describes nouns (nouns are things - including people places and concepts)#and an adverb describes verbs (which are 'doing words' that show the action in a sentence)#for example. 'she is careful'. careful is an adjective describing the 'she' in this sentence.#'she walked carefully'. carefully is an adverb describing how the action of walking took place.#adverbs in english usually end in -ly so that helps with identifying them#sorry if this is incredibly obvious#linguistics is one of those things that's been a special interest for so long that i genuinely have no baseline for what is common knowledg#darcey.txt#ask#darcey.lang#linguistics posting

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to say "receptively" in Russian?

Last night, while enjoying a quiet evening with a book, I stumbled upon an intriguing word: “receptively.” I was reading J.D. Salinger’s short stories when I came across this sentence: “I waited for more information, receptively, but none came.”

Why did this word catch my attention? Because I couldn’t easily translate it into Russian! Though I immediately grasped its meaning, it was the first time I encountered it. The Latin roots made it somewhat intuitive: recipe, recipient, receptacle, reception, and of course, receive. In the context, the character was curious, anticipating more information that never arrived. This subtle sense of openness, the act of being ready to receive information, is beautifully summed up in one adverb: receptively. But how do you translate that into Russian?

When we talk about receiving information in Russian, we usually use the verb воспринимать (to perceive). However, the related adjective восприимчивый describes a person as being susceptible or receptive—more of a character trait than a momentary action. As for the adverb восприимчиво, well, it doesn’t exist in Russian, as confirmed by the Russian National Corpus. You can’t perform an action восприимчиво.

In the comments on my poll, we explored possible alternatives and landed on заинтересованно (with interest). It’s close, suggesting a willingness to receive information—not just being open to it but actually wanting it.

The official translation by Sulamith Minita reads: “Весь обратившись в слух, я ждал дальнейшей информации, но ее не последовало” (I waited, all ears, for more information, but none came). Instead of a direct equivalent for receptively, the translator used an idiom, confirming my suspicion: there’s no exact adverb in Russian that conveys the same idea.

Interestingly, when I discussed this word with my English-speaking friends, some said receptively feels almost made-up, and my poll echoed that—about 10 percent of respondents agreed! Even Context Reverso shows that some English speakers confuse receptively with respectively, which is why I included both in the poll.

Once again, I’m reminded of the incredible challenge translators face. They constantly navigate these subtle linguistic nuances, and it’s nothing short of impressive. Let this post serve as a heartfelt appreciation for their work!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Seven Levels.

Muhammad said there are Seven Levels above the clay that creates divinity within man and helps him reach the state of perfection called Allah.

They represent stages of evolution man undergoes both as individuals sojourner and a civilization. They are represent the primary axis God gave Moses in the Torah. The number of Days is infinite, but the progression shows the closer one gets to infinity, the closer to Allah one gets. Watch.

Each Day or Level has a position in the spectrum, specific milestones, and details a way the mind of man grows more sophisticated as he practices religion and finds God. After he finds God at Day Six, he practices finding himself and others during Days > 7. As with all scripture the angels planted a hidden message under the letters that requires Gematria to understand. I am going to focus on the hidden portion in this frame.

1 Day: The Value in Gematria is 500. Hamesh Meowth, "The God of the Protective Wall Around the Ticket."

2 Days: The Number is 495, דטה, dtha, "the Edicts."

3 Days: The Number is 405, םה, meh, "how to gather in brother hood in ten sets of ten."

This refers to the fact a soul has to have a Number of 100 which is a perfect score if one achieves the understanding of God's plan for humanity. Recall Hebrew and the Numbers or polynomials. They do not mean what they appear to look like at face value they must be solved for the best meaning each one contains in the context of the scripture one is reading.

4 Days: The Number is 962, טוב, by the Fourth Day man should be capable of "Wellness, kindness" which means he does not need to follow the rules or be disciplined in order to cohabitate with others.

5 Days: The Number is 647, ודז, "and vdez"= the Vedas, called Hedus in Hebrew which refers to hedonism which requires food, wine, and a place to celebrate.

"The adjective ηδυς (hedus) means sweet or pleasant. It stems from the widely attested Proto-Indo-European root "swehd-" that also gave English the word "sweet".

Our adjective occurs often in Homer to describe the pleasant taste or smell of meat or wine. In the classics our word may describe the sweetness of pleasant words, feelings, a sweet welcome given to friends, or even sweet friends themselves. Our word could be used adverbially, and describe the gladness with which an action was undertaken (to gladly ask or to be pleased with some situation).

Our adjective ηδυς (hedus) appears to mostly describe physical or sensual pleasure. It's perhaps closely similar to the Hebrew verb נעם (na'em), to be pleasant, delightful or sweet (hence names like Naomi and Naamah). Our adjective isn't used independently in the New Testament and only the following derivatives occur:

The adverb ηδιστα (hedista), meaning most sweetly (2 Corinthians 12:9 and 12:15 only). This adverb derives from the accusative, neutral plural of the superlative of ηδυς (hedus), sweet or pleasant.

The verb ηδομαι (hedomai) circumscribes a broad array of ways to have pleasure or be pleased by, to be glad or delighted or amused with, to or in. This verb is also not used in the New Testament but from it come:

The adverb ασμενος (asmenos), meaning gladly or with pleasure (Acts 2:41 and 21:17 only). It's not wholly clear how this word was formed, or how (even if) it connects to our verb ηδομαι (hedomai) but possibly via a dialectal swing on a passive participle.

Together with the pronoun αυτος (autos), meaning self: the adjective αυθαδης (authades), denoting someone who is or wants to be pleased with himself and not too much with others; someone who values his own pleasure (or general worth) over that of others (Titus 1:7 and 2 Peter 2:10 only).

The noun ηδονη (hedone), meaning pleasure; not in some abstract sense, but rather pleasure had or experienced: that which pleasure-seekers seek or pleasure-havers have (hence our English word "hedonism"). It's essentially the Greek word for what we moderns call entertainment. Our noun is used 5 times; see full concordance. From it in turn comes:

Together with the familiar noun φιλος (philos), lover or friend: the adjective φιληδονος (philedonos), meaning pleasure-loving (2 Timothy 3:4 only).

Day 6: The Number is 1025, יבה, yevha, "Ya Hawa." "To act as defined."

The verb היה (haya), or its older version הוה (hawa), means to be busy acting out the behavior that defines that which acts. This verb never describes static existence (the dog is outside) but always the performance of a specific behavior that defines whichever is behaving in such a way (the dog is outside barking, sniffing, chasing squirrels, digging up bones and running off the mailman).

Very curiously, the verb הוה (hawa II), which is identical to the older version of the verb that means "to act definingly," appears to mean to fall. This may be an inconvenient coincidence, but much more likely reflects the deep insight that the development of defining behavior inevitably requires the falling away of certain rejected behaviors. This connection between "being" and "falling" may even be among the few driving forces of evolution.

Noun הוה (hawwa) means either a bad kind of desire or lust, or ruin or destruction. Nouns היה (hayya) and הוה (howa) describe destruction, calamity or ruin.

Day 7: The Number is 1466, ידוו, "Hand and Hand."

The culmination of the Seven Levels are Seven Laws:

The 7 Noahide Laws are rules that all of us must keep, regardless of who we are or from where we come. Without these seven things, it would be impossible for humanity to live together in harmony.

Do not profane G‑d’s Oneness in any way. Acknowledge that there is a single G‑d who cares about what we are doing and desires that we take care of His world.

Do not curse your Creator. No matter how angry you may be, do not take it out verbally against your Creator.

Do not murder. The value of human life cannot be measured. To destroy a single human life is to destroy the entire world—because, for that person, the world has ceased to exist. It follows that by sustaining a single human life, you are sustaining an entire universe.

Do not eat a limb of a still-living animal. Respect the life of all G‑d’s creatures. As intelligent beings, we have a duty not to cause undue pain to other creatures.

Do not steal. Whatever benefits you receive in this world, make sure that none of them are at the unfair expense of someone else.

Harness and channel the human libido. Incest, adultery, and homosexual relations are forbidden. The family unit is the foundation of human society. Sexuality is the fountain of life and so nothing is more holy than the sexual act. So, too, when abused, nothing can be more debasing and destructive to the human being.

Establish courts of law and ensure justice in our world. With every small act of justice, we are restoring harmony to our world, synchronizing it with a supernal order. That is why we must keep the laws established by our government for the country’s stability and harmony.

If we survive and agree to abide by the Seven Laws, the Quran says we may one day reach heaven, which is signified by the One Millionth Level:

Day One Million: 804, ףד, "the Ephod", AKA Enlightenment, called the Passport to Heaven.

So now we know where the system came from and it is not possible the ancients used the translation table I use, nor did they have Google as we know. The creation of the Torah and its Seven Level Logic was impossible for them but they did it nonetheless and Muhammad clearly understood it. The same logic is strewn throughout the Tanakh and the Gospels, it cannot be separated from these other documents.

This is all the proof we need of the divinity of the Torah, the Quran and the worthiness of Muhammad, God's Prophet, who said "do not fight, give alms to the poor, and protect the property of others."

Now will you do it? Will you hold the meeting, create the Emirates, make peace with Israel and force America and Russia and the rest to come out of the night, enter the Light and remain there?

This must be done as a result of prophecy not under duress, without temporary outside interference. The result must create permanent stability or the final level shall never take place during our lifetimes. It must be sown and grown by us, then deeded to the residents of the land as a benefit of citizenship. This, a foreign governmnet cannot grant.

0 notes

Text

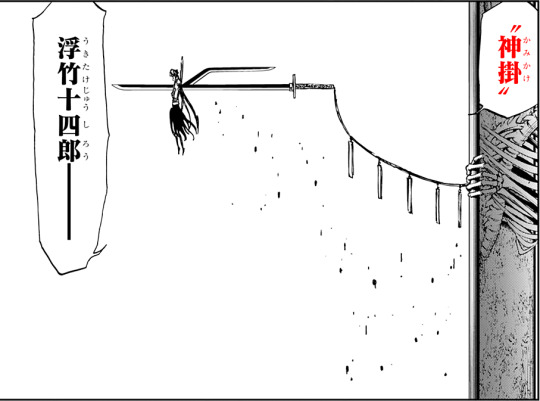

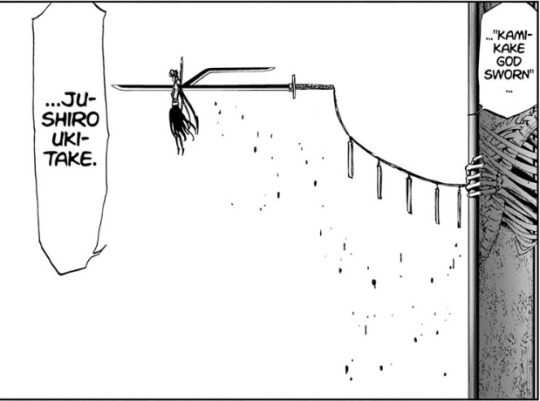

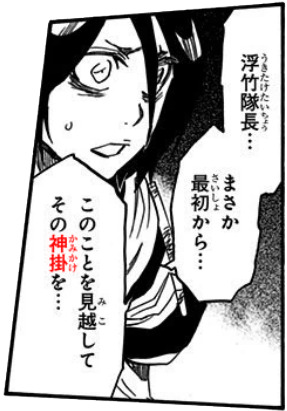

I was wondering if there was anything funky about the term "Kamikake," either the kanji or the English translations. And there kind of is, but also kind of isn't?? For one, both "God Sworn" and "Divine Vow" are sort of a weird degree removed from what I feel would be an accurate translation, but they do still rub up against the right idea... so they aren't exactly wrong either? But they feel like they lack context to be read correctly in English.

The immediate word/term referenced here is kamikakete[神掛けて] which most English translations seem to take as "swear by god" but very specifically it is an adverb, not a verb. Alternatively, "absolutely" shows up in a few sources, and less frequently "utterly," "dead," and "perfectly." So the practical use seems to be to describe something as being done with great certainty or without fail. Kubo however, uses just the kanji [神掛] in quotes and as a noun.

So right off the bat, the English use of it based on the adjectival "God Sworn" is wrong, because that seems to put the emphasis on the act of swearing (swearing how? to god.) rather than the idea that a different act was what was sworn. (you did what? how did you do it? in a godsworn fashion.)

To put it another way: The word is used more in the sense of something like, "I swear to god, I'm telling the truth!" where the phrase is kind of more clunky in English, rather than being a singular article in Japanese, but what it's describing is the act of "telling." In this kind of way a synonymous phrase might be something like "In all honesty, I'm telling the truth!" or "Without a doubt, I'm telling the truth!" the phrases don't actually involve or evoke an act of "swearing" or "vowing" the way it might otherwise imply in English, it's an emphasis of on the assurance of the action it's linked to. With all the certainty that "God assures..." or perhaps which "God has been assured..."

Sorry, got kind of carried away... Point being: That term I just described is the thing that Kubo turned from an adverb into a noun, and not the very similar sounding adjective in English. So, obviously this means we need to break down the colloquial phrase to the root words if we expect any kind of clarity...

The individual kanji read as [神]: "god(s)"/"[the] divine," and is of course pretty commonly used, so it's not like there's a lot of room for variations there... but [掛] can read a few ways...

The most readily available interpretation is "credit (as in finance)" or "money owed." Another is "-rest"/"-rack"/"-hanger" and although these might seem wildly disparate it does make a certain linguistic sense, especially in this particular case; A thing upon which someone's money "rests" is effectively a financial credit, or a debt depending on context. That upon which "god rests", or "god's credit(account)", or "a god debt" all describe Ukitake's circumstances with a little more clarity than "god sworn" or "god vow." (Also, a bit of a tangent, but it does evoke something like "god is resting on you" in a sense, which kinda relates to a point I'll get to later...)

So, it is effectively, "[The Thing] Sworn to God" or "Indebted to God" or with a little liberty, "What God is Assuredly Owed." And certainly calling it something just "Divine Vow" doesn't really imply all that. (or did it make sense to everyone else and I just did a lot of talking to point out the obvious?)

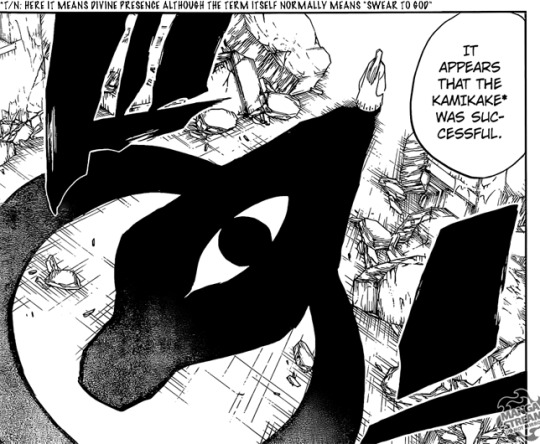

And what is the god Mimihagi "owed?" What was "sworn" to it? Ukitake's body and longevity, which was granted to him and his parents, effectively on loan, and which Mimihagi then collects on. Ukitake's parents basically sold their child to a creepy hand deity, because so long as that deity had use for him one day, it would keep him alive until then. And Ukitake understood that he owed his life to Mimihagi, so when he invoked the Kamikake himself, he was effectively choosing to repay his debt: Choosing to make good on his (parents') "vow."

And interestingly it's actually very much like what YHWACH's powers and the Sternritter Schrift were described as; Where YHWACH was born without any powers, or even basic bodily senses of his own, but could grant health and powers to others. Then they develop and cultivate further power by their own effort and merits, only to eventually die and give their accumulated power, talent, and experience back to YWHACH, making him stronger. And in the case of the Sternritter specifically, they also swore themselves to him via their blood oath, like what we saw Uryuu do. (Which btw links back to the christian references in the Vollstandig's use of the kanji for Eucharist/Holy-Communion)

Both Mimihagi and YHWACH have this ability to effectively loan their power and more importantly to collect on that loan with interest. (And if Kubo hadn't retconned Chad and Orihime's powers as having come from their proximity to the hogyoku, instead of Ichigo, we might have even been able to say Ichigo had such an effect as well...)

So, what's interesting about Szayel (and really, Kubo) bringing it up in the new chapter is that it's not just a random fancy epithet he's throwing at Ukitake, he's evoking that debt as a part of Ukitake. It makes it sound like Ukitake's being in Hell is somehow part of his debt. It's part of what he owes Mimihagi or the Soul King or perhaps a more nebulous god/the gods. So it may very well be that Ukitake is uniquely the new big scary skelly-door knife-hand guy because of that, and not because of a more general process of being a powerful shinigami in Hell. It's possible that other captains like Yamamoto and Unohana are in a role closer to Szayel's as prisoners, than they are to Ukitake's position or relative power as some kind of enforcer of Hell's boundaries.

112 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any suggestions for writing dialogues? I mean, when it comes to punctuations and actions the characters perform.

Okay, this ask has been in my inbox for months at this point, and I've been saving it because 1) I wanted to write something meaningful and 2) I didn't know what I could write that hasn't already been said ad nauseam by other writers. I still don't know if anything I say will be particularly groundbreaking, but I'll try to be helpful. Keep in mind, I'm a young writer, myself. I'm still learning new things every day, and I'm far from a guru in the field.

This got long, so I’m going to put it under the cut:

The first thing I did was ask my mother this question, because I was interested in hearing her answer. She doesn't write fiction, herself, but she has been in the editing game for 30 some-odd years. She edits fiction for Harper Collins Publishing and has an eye for these things. However, her answer to this was very plain and simple.

She said, "All editing and punctuation exists to serve one key purpose: to not confuse the reader."

As far as grammar goes, that's the main goal. I was looking for something a little more hard and fast--some sort of rule in a style guide--and y'know, I'm sure there is a rule out there. But in a fairly fluid world of fiction writing and "rules are meant to be broken" mentalities, the most important thing to heed is the comprehension of your reader. As soon as you’ve confused your reader, you’ve made a mistake. Not a failure--but a mistake that needs to be fixed. I’ve made them; I’ve fixed them. Dialogue can be a particularly tricky area, because it’s like a minefield for these mistakes.

I’ll add an example of my dialogue and break it down a little bit:

‘“Soldier?’ Red said, interrupting the beginning of another gushing tirade.

Larb's grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up. ‘…Yes?’

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line.’

His eyes dropped back down to the controls. ‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again.’”

First and foremost, it should be clear who is speaking. I help this along by making sure the characters’ actions are in the same paragraph as their speech. It keeps it more comprehensive. Otherwise, it would read like this:

‘“Soldier?’ Red said, interrupting the beginning of another gushing tirade.

Larb's grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up.

‘…Yes?’

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line.’

His eyes dropped back down to the controls.

‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again.’”

Not completely indecipherable, but distracting enough to make the reader re-read it a few times. As far as formatting goes, it’s also not very pretty. Now, I’m not perfect with this. In fact, I still need to go through Parade and reformat some sections that might read like the above. However, it is a readability rule that I’m trying to follow more closely.

Another difficulty with ensuring you’re making it clear who’s speaking can be the use of pronouns. I’ll be the first to admit, writing with multiple characters who all use the same pronouns can be incredibly difficult. You can’t always just use “he said” as a tag. It’s too easy to hit a snag where the reader gets confused and doesn’t know who “he” is.

‘“Soldier?’ he said, interrupting the beginning of another gushing tirade.

His grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up. ‘…Yes?’

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line.’

His eyes dropped back down to the controls. ‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again.’”

Sure, maybe this short passage isn’t so bad; It’s still fairly clear who’s speaking. But imagine if the entire book was that way: three, maybe four characters in the same room who all use he/his pronouns speaking without any further identification. It would get confusing and distracting. Lots of reading passages over again to try to decipher who is saying what and lots of frustration on the reader’s part. At the same time, always using the characters’ names can be tedious and unnecessary. Finding a good balance isn’t always easy, but it is worth it.

The golden rule, for me, is exactly as my mother said: “Do not confuse the reader.”

Below, I’ll add some additional dialogue tips I have picked up:

Constantly adding a tag can get tedious.

‘“Soldier?’ Red interrupted, cutting off the beginning of another gushing tirade.

Larb's grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up. ‘…Yes?’ he inquired.

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line,” Red replied.

His eyes dropped back down to the controls. ‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again,’” he muttered.

Sure, this makes sense. It’s clear who’s speaking. But it also doesn’t read as smoothly. Not to mention, the overabundance of different transitive verbs (interrupted, inquired, muttered), is stilted and almost mechanical in how the dialogue reads. Oftentimes, “said” is perfectly fine. Fun words like “muttered” and “interrupted” are great, too, but in moderation. Finding a happy medium can make all the difference.

Sometimes, a tag isn’t necessary at all.

This segues into my next piece of advice: it’s important to write dialogue in a way that still allows the reader to use their imagination. This is where I’ll go off on a bit of a rabbit trail, because this is something I’ve had to learn for myself recently.

Put trust in your reader to make up their own mind on how dialogue is spoken

I recently finished reading On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King (which, regardless of your opinions on King, was a very helpful book. I enjoyed it a lot). In one passage, he tells the reader to imagine an orange sitting on a table. Just that. He doesn’t give any further details. There is a 100% chance that we are all going to see something different in our minds. We are going to imagine a different table, a different room, and maybe even a different orange.

Sometime, description helps. Sometimes, a carefully placed lack of description lets the reader make up their own mind and encourages imagination. This advice has served me well in writing dialogue. I know it’s a tired old saying in any writer’s workshop: “never use adverbs in dialogue!” And to be honest, I still believe there can be a time and a place. But relying heavily on adverbs doesn’t do anything for the reader, except maybe shoehorn them into a state where they have to re-read dialogue with the new inflection.

‘“Soldier?’ Red said solemnly, interrupting the beginning of another gushing tirade.

Larb's grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up. ‘…Yes?’ he asked weakly.

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line,” he replied sternly, in a flat monotone.

His eyes dropped back down to the controls. ‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again,’ he said lowly, almost inaudibly.

Again, this feels stilted, and doesn’t really leave anything to the imagination.

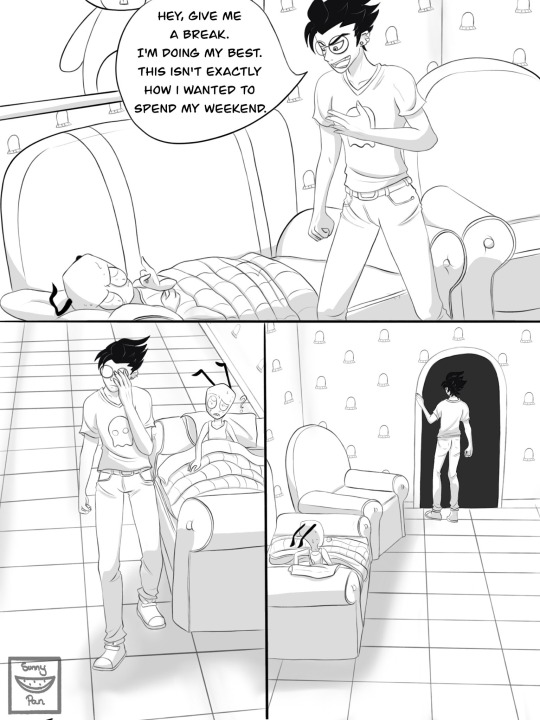

To better emphasize what I mean by this, I want to use a real example of it in action. (I hope you don’t mind, @sunnymelonpan!) Shortly after I read this advice and starting cutting down on over-describing dialogue and using adverbs, I wrote some IZ sickfic prompts. A friend of mine decided to draw up a comic based on one of them. This was not only incredibly flattering, but unexpectedly enlightening. I was able to see firsthand how other readers interpreted my dialogue. And lemme tell you, it wasn’t always exactly how I had envisioned it.

Here’s some dialogue I wrote for the prompt in question:

“Dib swiped the thermometer from him and pushed his glasses up his nose while he read it. ‘That’s because it isn’t going down. Huh.’

‘S-some help y-y-you are,’ Zim sneered.

‘Hey, give me a break. I’m doing my best. This isn’t exactly how I wanted to spend my weekend.’

Dib’s outline rose to its full height in Zim’s dimmed living room. He disappeared into the kitchen with the thermometer, then returned with something else in his hands. Without any warning, he placed it onto Zim’s forehead, scowling at the death glare he received in return.”

When I wrote this, I personally imagined Dib acting and speaking in a sort of annoyed, deflated way. Like he wasn’t really taking Zim’s harsh words seriously. Just a sort of eye-roll “yeah, whatever, Zim,” demeanor. That’s how I saw it.

This is how Sunny saw it:

In Sunny’s comic, Dib is genuinely angry. He gets annoyed, stands up, and actually berates Zim with these words.

I never made it clear how Dib spoke this line. Some people might look at this and say I failed as a writer because I didn’t explicitly say that Dib’s line was more casual than angry. I disagree. I left it up to the reader to interpret it as they chose. And Sunny surprised me by interpreting it in a way that was different. Not wrong! Just different. I positively loved seeing Sunny’s interpretation of my prompt. It let me see my writing in the eyes of others; it showed me that I was able to describe scenes while still allowing my readers to use their imaginations.

As a fiction writer, it is not my job to be a stagehand and tell the reader every minute detail of the scene I’m writing. Instead, it is my job to guide them through the story and allow them to envision parts of the story as they see fit. This is especially true with dialogue.

So let’s go back to the original excerpt from Parade that I was using as an example:

‘“Soldier?’ Red said, interrupting the beginning of another gushing tirade.

Larb's grin faded a bit around the edges as he glanced up. ‘…Yes?’

‘Just remember: you're walking a very thin line.’

His eyes dropped back down to the controls. ‘Yes, my Tallest… It won't happen again.’”

In this passage, I tried to apply all these rules:

Make it clear who’s speaking.

Use tags sparingly. Sometimes, “said” works just fine.

Use adverbs sparingly and don’t fall over yourself trying to describe everything.

The dialogue flows smoothly, it is clear who is speaking, and the reader can decide how it’s being spoken. Is Red angry? Impatient? Completely void of emotion in his words? Is Larb scared out of his wits? Trying to keep up a facade of bravery? Who knows! I sure don’t! I’m just the writer! It’s up to YOU to decide.

So... yeah! I know my advice wasn’t particularly groundbreaking, but I hope it was an interesting read, nonetheless.

#writing advice#rissy's asks#rissy rambles#ladyanaconda#keep in mind#i am not a professional writer#i have my degree in communication not english#i just write a lot and have the help of some professionals in my life#i also still have a lot to learn#so i am in no way some sort of sacred fountain of wisdom#sorry if i have some grammar errors too#i know that must make me look like a hypocrite#i'll try to go through later and fix as many as i can catch#this was kind of a 'stream of consciousness' post

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Catford's Translation Shifts

In this #translation post, we will look at another translation theory that might prove useful in the language teaching and learning process. Catford's translation shifts highlight the differences between languages. Recognizing them will help learners and teachers alike be more conscious of how languages function differently in terms of grammar, syntax, and structure

Translation shifts - definition

What does 'shift' mean? The word itself is defined as:

: to exchange for or replace by another: change (Merriam-Webster)

In translation, then, shifts refer to the changes that occur when a translator replaces, for example, passive voice in the source language with active voice in the target language. Why would they do that, though? Simply because the culture of the target language prefers active verbs. For instance, in Japanese, when you feel like you were a victim in a certain situation, you are more likely to use passive voice to stress that feeling. However, English speakers may or may not use passive voice to emphasize that feeling. Consider this example:

私はともだちにくるまをつかわれました。 I had my car used by a friend.

In Genki II (chapter 21), we read:

The victim is affected by an event. Marked with the particle は or が. The villian preforms an action which causes the suffering. Marked with に. The evil act is described with the passive form of a verb.

Does the English translation sound like it emphasizes the feeling of being a victim? It could be, depending on the context. But it could also sound like a very unnatural thing to say when you're upset.

Types of shifts

There are two types of shifts:

LEVEL SHIFTS

CATEGORY SHIFTS

Level shifts

In his book A Linguistic Theory of Translation, Catford explains that a level (or rank) shift refers to a situation where an element in the source language exists at one linguistic level, but its equivalent in the target language exists at a different level (Catford, 1978: 73). Simply put, the target language doesn’t have a corresponding word but a grammatical construction. We replace grammatical constructions with words or vice versa. For instance, in English you say:

I want to eat an apple.

To express your desire, you use the verb "to want." In Japanese, though, such desires are expressed through a verb ending ~たい.

リンゴが食べたい。

In Polish, to express that an action is happening at the moment of speaking, you will use the adverb teraz (now) without changing the aspect/tense of a verb. In English, you need to change the aspect/tense of a verb to the Present Continuous tense.

I’m working. Teraz pracuję.

In Polish, you must add the word teraz (now) to show that the action is happening now. The verb alone could indicate the Present Simple tense as well. Of course, if the context is clear, you can omit teraz.

We changed the Present Continuous tense to teraz (Grammar ⇒ Lexis).

Category shifts

Structure (syntax) Shifts

It refers to changes in the arrangement of the sentence's elements (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs). English is known for its SVO (subject, verb, object) syntax. However, Polish is a very flexible language. Sentences can start with adjectives, verbs, nouns, or even adverbs. In Japanese, though, sentences always end with verbs.

I have a dog. (Subject = I; Verb = have; Object = a dog)

犬を飼っている。 (Subject = omitted; Verb = 飼っている; Object = 犬)

Mam psa. (Subject = omitted; Verb = mam; Object = psa)

The Polish and English sentences don't differ in the arrangement of its elements, apart from the fact that the subject is omitted in the Polish sentence (the subject is implied; I can, but I don't have to include it). It is possible to say

"Psa mam" in Polish (in an appropriate context), while in English not so much (A dog I have; unless you are master Yoda).

Class (parts of speech) Shifts

Adjectives change to verbs, or nouns to verbs, etc.

I’m (verb) thirsty (adjective). || Chcę (verb) mi się pić (verb).

I want (verb) a dog. || 犬がほしい (adjective/noun)。

Unit (sentences, clauses, phrases, etc.) Shifts

Some languages are wordy and some are rather concise and flexible when it comes to word-formation. Polish tend to be wordy and prefers verbal structures, while in English it is easy to create nominal structures using fewer words. Japanese, on the other hand, thanks to its kanji, can express a variety of meanings through a single word.

生きがい (single word) = a reason for being (phrase)

物の哀れ (phrase) = a whole description because we can’t even put the meaning into one sentence

Dining room (phrase) = jadalnia (one word)

Intra-system Shifts

It refers to grammatical constructions that are present in both languages but are used differently. In Japanese, plural nouns are technically non-existent. The context will tell you if we talk about one thing or many things. However, we can create plural nouns when we talk about animate objects. The concept of plural nouns does exist, but is used differently in Japanese and English.

Bonnieたち = Bonnie and friends/and others

In Japanese, we use a suffix indicating that there is more than one person, but in English, we used an extra plural word to show it.

Another good example is an English grammar referred to as 'causative have' (which encompasses verbs like make, get, do as well). It's a structure that is used in English regularly. However, Polish speakers rarely use it while speaking English. It's not that there is no equivalent of it in Polish. There is, but in Polish, connotations with that grammar are a tad different.

Off-topic

Halliday states that language is realized at 4 different levels: lexis, phonology, graphology, and grammar. I’m not sure if graphology can influence a language learning process, but lexis, grammar, and phonology surely can. I mean, graphology (the way we write) can definitely slow down the whole process (looking at you Japanese! You and your kanji… ugh). Studying phonology (comparing sounds in different languages), on the other hand, can help you work on your accent (studying phonetics would be even better in this case).

So, how this knowledge can help you?

It will help you ask better questions in class.

Understanding how your native language works will speed up your learning process tremendously.

If comparing languages is your favorite language learning method, Catford’s translation shifts can give an idea where to start and what to notice.

If you’re a teacher, it can help you explain some grammatical phenomena.

If you help others learn your native language, you’ll be able to explain grammatical issues, or at least give examples.

You’ll speed up your translation abilities.

Sources

https://stba-pertiwi.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Translation-shift-of-STBAs-Students-by-Susiyati.pdf

my notes from college

A Linguistic Theory of Translation

#english#translation#linguistics#langblr#translation theories#Catford#translation shifts#study tips#rants about language

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common Advice: when to use it, and when to ignore it

When it comes to writing, there are the pieces of advice you've heard over and over ad infinitum. You know them, "show don't tell," "don't use adverbs," "always use said," "said is dead," etc. Unfortunately, these pieces of advice aren't as helpful when they're seen as absolutes, or as monoliths. For the most part, the pieces of advice that these sayings stem from have been overgeneralized to make it easier to recite them.

(this is a semi-long post. All tips below the cut)

Show don't tell

Frequently, this is excelent advice. This is saying that for the most part, you should err on the side of showing what a concept manifests it as, rather than stating the concept specifically. For example, if you have a character who is excited, it's a lot more effective to SHOW that xe's grinning, and can't sit still, bouncing in xir seat. It is far less effective to TELL "xe was excited." The reason why is that as readers, we latch onto characters using our power of empathy. We feel what are characters are feeling. Empathy is something that relies more on details to create a general picture, rather than the other way around. If we hear "xe was sad" we might feel sympathy, which is more removed, but if we see how that character shows their sadness, we're more likely to feel for them too.

The exception:

Showing is great when talking about the character's interactions, but you should ABSOLUTELY tell when talking about backgrounds. Saying "the curtains and walls were clashing shades of orange" and moving on with the relevant stuff is far, far more effective than taking up a whole paragraph to talk about how the subtle hues of the light passing through the curtains created an aura of longing within your MC, and then going on with a seperate paragraph showing how the walls had a different shade, and how that made the characters feel and then showing how that clashed. It's too much. The other exception is that while you should always show if characters come up with a plan that doesn't work, you should always tell if it does, so that readers won't know exactly what to expect.

In short:

When to use show don't tell: when it increases reader's empathy of a character, and/or when it is important to the plot.

When not to use show don't tell: when it is something that is irrelevant to the plot, such as setting details, or when it is characters creating a plan that works.

Don't use adverbs

(Adverbs are like adjectives for verbs. They describe qualities of the verb, similar to how adjectives describe qualities of nouns. Most adverbs end in -ly)

Like show don't tell, this is often perfectly fine advice. Many times, there's just not much of a justification for using adverbs: it creates a much more passive reading experience, whereas if you use stronger verbs, you can create a much more active experience. Adverbs are also redundant most of the time. For example, instead of running, "xe ran quickly," you might just write "xe sprinted." Sprinted is a much more engaging verb. It also creates a more vivid image in the reader's mind. Also, running is inherantly quick. Saying it twice just uses more words, and that's valuable space on the page. If you're trying to get rid of adverbs from your manuscript, try searching "ly" in the find and replace function, as most adverbs end in -ly.

The exception:

Adverbs can slide if they change the meaning of an action. For example, if you write "she smiled sadly," you've ascribed to the verb "smiled" a quality it does not inherantly have. The adverb now has a purpose. If you were to cut it, the meaning of the whole sentence would change.

In Stort

When to avoid adverbs: when it doesn't change the meaning of the verb, and/or it is redundant.

When you can use adverbs: when it does change the meaning of the verb.

Always use "said"

There actually seems to be a fair bit of debate about whether or not you should use said, or if you should use alternate dialogue tags, a camp who frequently uses the phrase "said is dead," as their dialogue tag motto. For the most part, using said more often than not seems to be what many experienced authors recommend, and for good reason: said is basically invisible to the reader. It's such a common word that readers pretty much gloss over it, absorb the information they need, and then just move on. This means the focus is mostly on the dialogue, and the action statements, which are the more important aspects of a scene. Unless you are putting tags on every single line of dialogue (don't), it doesn't even get too repetitive. While fancy dancy dialogue tags aren't likely going to be repetitive, they will make your prose sound a bit ridiculous if used in excess. If every character is hissing, mumbling, snarling, roaring, slurring, moaning, cawing, screaming, etc, it gets overwhelming and a little.... yeah, ridiculous. "Said," on the other hand, is much simpler, and also more malleable to whatever tone you're trying to achieve.

The exception:

(This is where, if you listen closely, you can hear cries of "said is dead!") The most common exception to always use "said" is using the word "asked." "Asked," like "said," is neutral - you can mold it to whatever you're trying to write fairly easily. If you do want to use alternate dialogue tags, use them sparingly so you don't run into the problems listed above. These alternate dialogue tags should be used more for emphasis than anything else.

In short:

When to use "said": when you want the reader to focus on the dialogue and action, but still be aware of who is talking.

When not to use "said": If you want to create extra emphasis on a line of dialogue (use sparingly), or when a character is asking something, in which case "ask" works well.

#writing#writing advice#writing tips#writeblr#writers on tumblr#common writing advice#common writing tips#always use said#said is dead#don't use adverbs#show don't tell#olive's writing vibes

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obedience is Rewarded

Exegetical exposition of a text from Malachi 3:13-18

Malachi, in this text, tried to awaken Israel from carelessness in relating to God. Cyrus the king of Persia who allows Jews to return to Palestine, and rebuilds the temple (2Chronicle 36:22, 23; Ezra1:3; 6:3-12). People come to Jerusalem from Babylon with high hopes, because the prophets in exile prophesied about the restoration of Israel. They come to Jerusalem thinking that the messianic age will dawn immediately. And there will be peace and joy. Not only that Haggai and Zachariah also added to their hopes by assuring the people, that if they will rebuild the temple the glory of the Lord would come with unprecedented blessings. Therefore they built the temple and waited, but there was no glory, no prosperity. People were so depressed and disappoint. Because they were aroused to expect plenty but there was nothing.

In this situation, Jews in Palestine lost their Theocentric consciousness. They fail to acknowledge that they are the special possession of the Lord. “They fail to acknowledge God as their father and Lord” (Pieter A.Verhoef 160). And they opened themselves to the Persian Empire. Many Ammonite and Moabites started mingling and submit into the community life of covenant people. “The priest Eliashib fitted out a room for his relative, Ammonite Tobiah (Nehemiah 2:10), in the court of the house of God (Nehemiah 13:7-9) (161). They began to have marriages with heathen people. As a result, there were divorces and unfaithfulness. There was a desecration of Sabbath; there was the carelessness of temple offerings. They became disobedient. They profaned the covenantal relationship with God. They opened their mouth to speak harshly against God. They became a community of murmuring and complaining. A nation that was chosen by God to become his people turned their back to God. In this situation, Malachi a messenger of God called to fulfil his prophetic ministry and brings the message for them.

Verses 13 to 15 Murmuring Israel

V.13, who are these people who are speaking against God? “Scholars differ in their opinion” (312), some say that they are pious people; some say that they are a priest. But when we read we will find that they are the people who once were serving and obeying God but they have stopped now. In 2:17-3:5 the speakers are the covenant people without any distinction. In this verse, God is accusing these people of murmuring against him. He says that “you have spoken harsh words against me” (3:13a NRSV: Catholic Edition). According to George Coats, “these words were words of open rebellion. The act of murmuring poses a challenge to the object of murmuring is sometimes Moses and Aaron and other leaders of people and sometimes it is Yahweh (Exodus 16:7, 8; Number 14:27, 29, and 35: 16:11; 17:20).” Their words are so harsh and strong that is unbearable to God. What is that so harsh so strong words which unbearable to God? Let’s see v.14.

That harsh word which people were saying is that “it is vain to serve God” (3:14a NRSV). According to Verhef, “serving the Lord does not make sense. It is futile, in vain. The Hebrew word ‘saw’ denotes that which is without substance or content, which is in itself worthless. The notion that is vain to serve God is expounded in (v.14b) notably.” The Hebrew word ‘saw’ of the first phrase is similar to the Hebrew verb ‘besa’ which means gain or profit. “In this text very idea of profit in connection with the service of the Lord is harshly questioned: what do we profit by keeping his command? What benefit do we derive from it? What does it benefit to keep his commandments, to walk in his way” (315)? In this verse profit in connection with the service of the Lord. People wanted material blessings for their service and obedience. According to the Malachi between these periods when Nehemiah visits Palestine, these harsh words reveal the mind of covenant people that they are not happier to serving the Lord. The renewal of the covenant with God accepted with joyfully of its obligation as history as far as their concerned (Nehemiah 8-10), and not as mandatory because as per their experiences there was no benefit in serving the Lord. And when they saw no material blessings they murmured. And they were saying, what do we gain by observing his charges? And they were saying, “what have we gained by keeping His requirements and walking mournfully before the LORD of Hosts?” (The Apologetics Study Bible). The specific form of the Hebrew words for mourning is ‘qedorannit’ which is used only here but similar to another Hebrew word ‘qadar’ meaning to darken, to be dart, unattended and in mourning attire. Sometimes its use as synonyms of grieve or mourn (Jer.4:28; 14:2; Ezek.31:15; Isa.50:3). As well as both meaning and expression are found in the psalmist's words in (Ps.38:5) and in (Job 30:28). Verify says, perhaps to please God and to become righteous before God, these people became religious persons (316-17). They show themselves as mourners. But they said that is also vain.

In verse 15, these people are comparing themselves with wicked. And they say that “So now we consider to arrogant to be fortunate. Not only do those who commit wickedness prosper, they even test God and escape” (The Apologetics Study Bible). The experienced promised people is to serve God does not benefit or prosper to righteous (3:10-12), and think that in this situation wicked is better seems to be blessed. Because arrogant and evildoers prosper and escape though they don’t obey and serve God. They are asking God, what you have given us as the reward of our obedience and the service.

As we know murmuring as an act of disobedient. Laetsch rightly calls this “a blasphemous perversion of God’s challenge. Their testing of God is arrogant and does not evolve from the fear of the Lord. Despite their arrogant words and behaviour, the assumption is that they will escape the judgement of God.” God does not like murmuring. Murmuring hides blessings and it brings punishment instead of blessings. Israel is a good example before us. Whenever they murmur God punished them.

Verse 16, God-fearers

Who these God-fearers? According to Joyce Baldwin, “those who feared Yahweh are not necessarily a different group from those who had been complaining, but they are those who have taken the rebuke, and they begin to encourage each other to renewed faith”(338). But then, Eiselen wrote, “it is not possible to identify the God-fearing persons of (v16) with the persons who gave expression to their doubt in the language of (v14-15); two distinct classes are meant” (38). We accept that God-fearers are a separate group. What they are speaking to each other is unknown here. But God listened to them. Two verbs are used for listening; in NRSV Lord Look note and listened. It means that God listens carefully to the talk of the people both obedient and disobedient. He listened to the talk of obedient because their talk pleases him for their praise and thanks to him for everything whereas disobedient makes him angry. Because they always murmur and speak filthy words, further it says that there is a book of remembrance before God. The expression of the book of remembrance is found only here. But the idea that God having a book is found in the Bible. Like, the book of life, Exodus 32. It was a custom of ancient Asian kings to have a record written of the most important events at their courts and their kingdom. This expression shows that God is present everywhere. The idea can be drawn here that God is not certainly an observer of the things, but he takes note of everything. God knows every action and word, whether it is good or bad. He knows every person both good and bad.

Verses 17-18, the distinction between righteous and wicked

In these verses, we will see a reward for obedient and punishment for disobedient. Let’s see the first reward. V.17, tells on the day of God, the God-fearers will be his treasured possession. The term treasure possession usually applied to Israel as people of God. And this term here shows “pious remnant” (22). Every God-fearer who obeys and serves him is his property. “I will spare them as parents spare their children who serve them” (3:17b NRSV). The Hebrew word for a spare is ‘hamal’ meaning have compassion on. On the day of judgement, when there will be tribulation and sorrows, God will have compassion on those who do not murmur, obey and serve him without question.

V18, Then the verse starts with “then once more” (3:18b NRSV). Smith suggests that “the precise meaning of ‘return’ here is not clear. Does it mean ‘repent’ as it often does? You will return from your present mind and see.” However, most modern translations read it in an adverbial sense ‘again’ (KJV, NAB, RSV and JB). “The verb ‘sub’ is used in the sense of an adverb” (23). “I will make the distinction between the righteous and the wicked” (v.18a Net Bible: First edition). There are two Hebrew words for righteous and wicked are ‘Sadiq’ and ‘rasa’. Both words are used in the plural form and described as those who serve God and those who do not. One should look at with a religious and spiritual perspective because it does not merely mean serving the Lord but a covenantal relationship with God and his pious remnant people. God had tried throughout history in various ways to impress the distinction between the righteous and the wicked. But people could not see that. But on the day of judgement people will see a clear distinction between righteous and wicked.

Application

We know that the day of God is coming soon when he will judge everyone. He will punish all wicked and evildoers. He will punish everyone who murmurs and complains against him. But he will reward all obedient who trust in his promises and serve him. We should not compare the evil one with us. They look prosper and well. But they have nothing in reality. But the one who obey and trust God will enjoy all prosperity one day. Though there are troubles and problems it will be over soon. As Jesus answers to Peter in (Mark10:29-30).

God was always faithful towards Israelites. But when a Persian king allows them to return their homeland and build a temple, they build with a high expectation of worldly pleasures as they look at others. And in this course of time, they fail to wait, obey and faithful to his covenant. Instead of waiting upon Yahweh they opened themselves to heathen people and started those entire things which were not pleasing to him. They started comparing with mourners and expecting profit with the serving of Lord. In this situation Malachi a messenger of God comes and rebukes them. Those who listen to rebuke and stops murmuring, God addressed them as special possession in his sight and will reward them but those who do not listen to rebuke to them God will punish. Malachi says you will see the difference between righteous and wicked on the day of God.

Cited Work

Smith, Ralph. “32 Word Biblical Commentary: Micah-Malachi.” Word Books: Waco, Texas, 1984.

Verhoef, Pieter A. “The New International Commentary on the Old Testament: The book of Haggai and Malachi.” William B.Eerdmans Publishing Company: Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1987.

Clark.T.T. “The International Critical Commentary: On Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi and Jonah.” T.andT.Clark LTD, 36 George roads Street: Edinburg, 1980.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thursday Thoughts: Writing Advice (Part 1 of 3)

I recently stumbled across this writer ask meme about pieces of writing advice, and I was having so much fun thinking about it that I decided to just respond to them all!

1. Nothing is perfect

This is one of those truths that can be used for good or ill.

It’s easy to see the flaws in your own work, to hold your own writing to a higher standard than literally anyone else would. It’s good to say “nothing is perfect” to assure yourself that your work is good enough.

But if someone has called you out for using racist stereotypes in your writing, and your response is, “Well, nothing is perfect! So leave me alone and don’t tell me to fix it!” That’s bad!

Allow me to misquote the Talmud and tell you to keep two pieces of paper in your pocket, and take each out as you need it. The first says “nothing is perfect.” The second says “I can, and should, always do better.”

2. Don’t use adverbs

Adverbs are tools. Understand their purpose and use them wisely.

To prove my own point, I could not have written that second sentence without an adverb – “wisely.” The purpose of an adverb is to modify a verb or an adjective. It wouldn’t be enough for me to just say, “use them.” How should one use them? Wisely!

The best advice I ever got about adverbs is that they should be used when they are necessary for clarity.

If I write, “Sophie smiled happily,” that is not a necessary adverb. It is already obvious from the fact that I am smiling that I am happy. Using “happily” is redundant and uninteresting.

If I write, “Sophie smiled sadly,” on the other hand – that is necessary. The adverb changes the picture that you make in your head, and the sentence is more interesting as a result.

3. Write what you know

I get why people use this as advice. I’m much more a fan of saying “know what you write.”

Feel free to go beyond your own individual experience when you write – but for god’s sake, do your research. Expand what you know, so that you can write.

4. Avoid repetition

Like adverbs, repetition is a tool. Use it wisely.

What can repetition accomplish?

Emphasis – highlighting something as important.

Memorability – helping the audience remember.

Familiarity – we tend to like and believe what we hear over and over.

Musicians understand this. Listen to the Hadestown soundtrack and keep a tally of how many times Orpheus is referred to as “a poor boy” or Eurydice as “a hungry young girl.” Listen to the Hamilton soundtrack and count how many times Burr opens a song with “How does a –?” Think back on all the times you heard the new hit song of the year and you shrugged it off, but a couple weeks later, after you heard it on every radio station, on everyone’s Spotify playlist, in every YouTube ad – it “grew on you.”

The trick is using repetition just enough that it provides a useful structure, but not so much that it’s noticed to the point of instilling boredom.

5. Write every day

Sure, why not. If you write just ten words every day for a year, you’ll have nearly 4,000 words at the end of it – a short story. If you write a hundred words every day for a year, that’s almost 40,000 words – a decent novella. Writing every day is a good way to end up with something written.

But don’t beat yourself up if you don’t or can’t write every day. Writing takes effort. You have other things to devote energy to – work, school, groceries, cleaning, socializing, confronting your own mortality, finding out how season seven of Clone Wars ends.

I encourage you to notice all the things that you do every day which isn’t officially “writing” but is still a part of being a writer.

Now, this is something I struggle with. I go months without touching my novel, and it’s easy for me to dismiss that time as “not writing.”

But I send emails. And I write essays for school. And I jot down thoughts and dreams in my journal. And I read – you have to read in order to write. And I spend time on my walks and in the shower imagining dialogue and figuring out character paths and themes for my novel, all things that will help me when I do get back to writing it. And I have all the smaller projects I gave myself – this weekly blog post, my weekly poem or quote, my fanfiction.

If you’re a writer, then you’re a writer, whether or not you write every day.

6. Good writers borrow from other writers, great writers steal from them outright

I’m not sure what the distinction is here between “borrowing” and “stealing.”

Stealing is definitely a part of writing, though. I’ve written about this before – check out my old article on stealing bicycles as a writing metaphor.

7. Just write

Oh I am a BIG fan of this one. Even if you don’t know what to write, just write. So many pages of my journal open with the line “I have no idea what to write about.” Eventually, as you ramble, you start writing about what you wished you would be writing about. And then you find yourself actually writing.

8. There’s nothing new under the sun

Sure, but the art is in making something familiar feel new. I wrote about this a couple weeks ago in this Thursday Thoughts.

9. Read

Yes, yes, yes! Read to find out what’s out there. Read to learn the conventions of your genre. Read to ignite your love of the craft. Read to discover your people. Read to add tools to your toolbox (or pieces to your bicycle). Read to find agents and editors and publishing imprints. Read to learn what stories are not being told. Read to be a writer.

10. Don’t think!

Thinking is a tool. Use it wisely.

The best parts of my writing I’ve discovered not while writing, but while thinking about writing.

Just don’t think yourself out of writing altogether.

11. Write what you love

You’ll certainly be happier writing something you love than something you don’t love. You won’t love everything you write, though. It can still be good and valuable even if you don’t love it. But if you love it, or if you can remember why you loved it, you will come back and finish it.

12. Never use a long word where a short one will do

Forget the length of the word. Is it the right word?

To paraphrase Mark Twain and Josh Billings, the difference between the right word and the almost-right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.

If you do find yourself needing to choose between two words with identical definitions, and the only difference between them is their length, then think about the effect of the word on your reader. Read the sentence aloud a few times with either option. Different words have different connotations; they evoke different moods. It may in the end just come down to which word feels right for this moment.

13. Less is more

No, it definitionally is not. See my above thoughts about adverbs, repetition, and long words vs short words.

All words are tools. All words have a purpose. Is it the right word for this moment?

14. Never use the passive when you can use the active voice

Again, active voice and passive voice are tools! They have purposes!

The simplest way to differentiate between the two is that active voice is “the girl threw the ball” and passive voice is “the ball was thrown by the girl.” Both make sense. Both describe the same action. But one places the emphasis on the girl – the subject – while the other places the emphasis on the ball – the object.

Are you trying to create a sense of immediacy, to immerse the reader in the moment? Use active voice. He did this! She did that! Bam! Pow! It’s happening right now, and we know exactly who did it!

Are you trying to create distance between the reader and something in the moment? Use passive voice. He was being followed – by who, we don’t know. Passive voice adds a touch of mystery or disassociation.

15. Show don’t tell

How do you show? How do you tell? There are engaging ways to do both, and boring ways to do both. Do what the moment needs.

In prose, I recommend setting up with showing and then hitting your reader with a tell. Say your protagonist is standing alone in a room. Then, a woman enters. Show the protagonist’s reaction to that woman – their heart pounds, they tear up, they grab a chair for support…

And then, in the narration: “Her mother had been dead for five years, and yet there she stood.” Bam! A well-placed tell which contextualizes the reaction.

Plays and screenplays come down on different sides of the “show vs tell” debate. Film usually does more “showing,” while a stage play usually has more “telling.”

This comes from writers leaning into the limitations of the mediums. The first few lines of any scene in a Shakespeare play lets you know the location and time of day, because they didn’t have the scenic or lighting elements available to show it.

While a film can cut to different places and times quickly and easily, many plays are set in just one or two locations to remove the need for frequent scene changes. A play will capitalize on the characters’ reactions to and conversations about unseen offstage events, while a film will show these offstage events.

These are not hard and fast rules, of course. Plenty of films stay in one location, and plenty of plays jump around from place to place. It’s worth noting that standard formatting for plays and screenplays highlight this typical difference. In a stage play script, the dialogue (what we’re told) is left-aligned while the action (what we’re shown) is indented. In a screenplay, the action is left-aligned and the dialogue is indented.

Neither showing nor telling is superior. They are both tools. Use them wisely.

To be continued...

#writing#advice#writing advice#writblr#writers#writers of tumblr#show don't tell#thursday thoughts#listicles#shakespeare#active voice#passive voice#word choice#just write#write what you know#adverbs#write what you love

1 note

·

View note

Text

Red Velvet “So Good” Lyrics Breakdown + Translation

빛을 등진 커튼 사이 작은 바람결에 살랑이는 몸짓 Oh I love 까만 실루엣도 좋아 난 말이 막힐 만큼

빛 - light, ray, beam, twinkle, glow, gleam

~을/를 - object particle

등 - back, position, ranking

지다 - to fall, to sink down/into, to settle

V + ~는 - used to turn verbs into present tense direct modifiers (ex.: 읽는 책 - the book that is being read)

커튼 - curtain

사이 - gap, space, relationship

작다 - to be small, to be little

V + ~ㄴ/은 - used to turn descriptive verbs into adjectives

바람결 - rumor, hearsay, gossip, (lit.) movement on/of the wind

~에 - time/location particle

살랑살랑 - onomatopoeic word for “gently” (typically used to describe how things move in the wind)

~이는 - attaches to nouns in order to prep them to be modified by a following verb/verb phrase (이는 —> ~이다 + ~는)

몸짓 - gesture, motion

(새)까맣다* - black

실루엣 - silhouette

~도 - also, too, even

좋다 - to be good, to be nice, to be fine

~은/는 - topic particle

말 - word, speech, language, term, expression

~이/가 - subject particle

막히다 - to be stopped up, to be clogged, to be blocked

V + ~ㄹ/을 만큼 - as much as [verb].../to the point of being [verb]...

Think of this as an adverb phrase of sorts since it’s used to describe another verb when 만큼 is sandwiched between two verb [(ex.: 많을 만큼 필요없어. - I don’t need much. (NOTE: This is not the most natural way to say that; I used this specific wording, though, to help illustrate this point since those are very common words that are most likely very familiar to you.)]

Translation: Between the light beams slipping past the curtain / The dust dances in the gentle breeze of your movement / Oh I love even your darkened silhouette / It’s so perfect, I’m speechless

* - In Korean, colors are descriptive verbs.

좀 더 멀리 아니 깊이 내 머릿속을 헤엄치고서 아득히 퍼진 이 느낌 뭐였니 사랑이라는 이름이 맞겠지

좀 - few, little; contraction of 조금

더 - more, further, farther, again, another

멀리 - far (away)

아니다 - to not be

깊이 - depth, deep, deeply

~의 - possessive particle (내 —> 나 + ~의)

머릿속 - in one’s head

머리 - hair, head

속 - inside, in

헤엄치다 - to swim

~고서 - so, therefore, thus

아득히 - far off, vaguely

퍼지다 - to spread, to flare out, to go around

이 - this

느낌 - feeling, sense, sensation

뭐 - what, something

~이다 - to be

~니 - informal/casual question ending

사랑 - love

~(이)라는 - used to either refer to something by its name (i.e.- “...[thing] that is called…”; ex.저기 길에 “다이소”이라는 ���게가 있습니다. - There’s a store called “Daiso” over on that street.) or to discuss an abstract concept & its characteristics (ex. 남들이 사랑이라는 너무 힘들은데 제일 쉬운 것은 한다고 말해요. - People say that love is difficult but that it’s the easiest thing to do.); this is a contraction of ~(이)라고 하는

이름 - name

맞다 - to be right, to be correct, to prove true

~지 - informal/casual question ending (typically used when asking a rhetorical question)

Translation: A little further, no, deeper / Until my head is swimming / What is this feeling taking over me? / It must be love, right?

스며든 그 향기가 좋아 이 기분이 좋아 가까이 와

스며들다 - to soak (in), to permeate, to penetrate, to infiltrate, to pervade, to sink

그 - that, the, he, his

향기 - scent, perfume, fragrance, aroma

기분 - feeling, mood

가까이 - close, nearby

오다 - to come, to visit, to show up

Translation: I love the way your scent lingers / I could get used to this feeling, come a little closer

이미 빠져들어 고요한 파도가 쳐 넌 나에게로 (가득 번지고) 난 뛰어들어 (맘은 넘쳤어)

이미 - already

빠져들다 - to fall (into)

고요하다 - to be quiet, to be tranquil, to be peaceful, to be still, to be placid

파도 - wave

치다 - to hit, to strike, to surge, to undulate, to smack, to punch, to slug, to slap, to beat

~에게 - “to/toward” particle

~(으)로 - means by which/method particle (think: “for,” “by,” “toward,” etc.)

가득 - full, to capacity

번지다 - to spread, to run, to grow, to escalate

V + ~고 - “and” connective used with verbs

뛰어들다 - to run, to dash, to rush, to dive/plunge into

맘 - heart, feeling, mind; contraction of 마음

넘치다 - to overflow, to brim over, to explode with/into, to flood

Translation: I’ve already fallen for you / Like a calm wave rolling in / You come to me (Wash over me) / I’m diving in headfirst (My heart’s overflowing)

온전히 깊은 울림인 걸 귓가를 간지럽혀 넌 나를 채워 (맘은 넘쳤어) Um 이대로 so good so good to me

온전히 - in full measure, wholly

깊다 - to be deep, to be bottomless, to be profound, to be strong, to be serious

울림 - echo, reverberation

~인 - contraction of 이는 (see above)

V + ~는 것 - pattern used to turn verbs into direct modifiers of nouns

걸 - thing, contraction of 것을

귓가 - rim of the ear

간지럽히다 - to tickle

채우다 - to fill in/up, to pack, to stuff, to satisfy, to complete, to fulfill, to fasten, to lock

이대로 - as it is, like this, in this way

Translation: Like an endless echo ringing in my ears / You fill me up (My heart’s overflowing) / Um, just like this, you’re so good, so good to me

들뜬 나를 어루만져 그 손길 난 사로잡혀 (oh 나를)

들뜨다 - to be excited

어루만지다 - to pat, to soothe, to stroke, to comfort

손길 - touch

사로잡히다 - to be caught alive, to be taken captive, to be seized, to be fascinated by

Translation: You keep my feet on the ground / I’m a prisoner to your touch

잉크같이 한 방울씩 하루하루 번져가는 너 점점 난 너라는 짙은 색을 입어가 때로는 은은히 모르는 새

잉크 - ink

~같이 - same as; derived from 같다 (to be similar to, to be equal, to be identical, to be the same as)

한 - modifying form of 하나

방울 - drop

~씩 - attaches to counters to indicate/highlight that the thing/action being counted will be split into the quantity specified by any number preceding the counter

하루 - day

하루하루 - day by/after day

번져가다 - to go spread/grow out (번져가다 —> 번지다 + 가다)

점점 - gradually, increasingly, little by little, bit by bit

짙다 - to be deep, to be dark, to be heavy, to be dense, to be thick

색 - color

입다 - to dress, to put on, to wear (입어가다 —> 입다 + 가다)

때로는 - occasionally, sometimes, in some cases, at times

은은히 - indistinctly, delicately, dimly, faintly, distantly

모르다 - to not know, to not understand, to not be aware of, to be ignorant

새 - time, span, gap, space, distance

Translation: Just like ink, drop by drop, everyday you’re spreading / Bit by bit until I’m covered in you / Sometimes without me even knowing

이 시작은 중요하지 않아 오직 지금이야 끌리잖아 woah

시작 - beginning, start

중요하다 - to be important, to be significant, to be crucial, to be critical, to be vital, to be momentous

V + ~지 않다 - verb pattern used to negate verb

오직 - only, solely, alone, exclusively

지금 - (right) now, present moment

끌리다 - to drag, to be drawn to, to be attracted by

~잖아 - particle denoting one’s previous awareness or knowledge of something (think “you/I already did/knew”)

Translation: How we got here isn’t important / All that matters is right here, right now, I’m spellbound

말해줘 여러 번 여러 번 너도 내게만 속삭여 yeah

���하다 - to speak, to talk, to tell, to express, to communicate

V + 주다 (to give) - used to soften a command into a request when used with/after another verb

여러 번 - many times

속삭이다 - to (be a) whisper

Translation: Tell me, over and over, again and again / Just whisper it to me

요동치는 머릿속은 (속은) 너로 가득 차서 정신없고 (없고) 감출 수 없게 해 난 너를 원해 퍼져가 흘러든 감정 벗어날 수 없어

요동치다 - to fluctuate, to shake, to jolt, to rock, to roll, to pitch

차다 - to be full of, to be filled with

~서 - so, because; contracted form of 그래서

정신 - mind, spirit, soul, consciousness

없다 - to not have, to not exist

감추다 - to hide

V + ~ㄹ/을 수 없다 - to be unable to do

V + ~(으)게 - future tense verb pattern (can only be used in first person; add “~요” to make it more polite)

하다 - to do

원하다 - to desire, to want, to wish, to hope, to long for

흘러들다 - to flow in, to pour in, to empty into, to find one’s way into

감정 - feelings, emotion, sentiment

벗어나다 - to get out, to free, to break away, to rid oneself of

Translation: In my scattered mind (In my mind) / It’s so filled with you, for my senses there’s no room (No room) / I’m not gonna hide it, I only want you / My feelings keep growing, I can’t escape

이미 깊이 빠져 마음에 나를 맡겨 넌 나에게로 (가득 번지고) 난 뛰어들어 (맘은 넘쳤어)

빠지다 - to fall out/in, to deflate, to drain

맡기다 - to leave, to check, to deposit, to put, to assign, to entrust

Translation: I’ve already fallen so hard, I’m giving into my heart / Just come to me (Wash over me) / I’m diving in headfirst (My heart’s overflowing)

온전히 작은 숨결은 또 (숨결은 또) 귓가를 간지럽혀 넌 나를 채워 (맘은 넘쳤어) 이대로 so good so good to me

숨결 - breath, breathing

또 - again, once more, also, too, as well

Translation: Even your tiniest of breaths (even your breath) / Rings in my ears / You fill me up (My heart’s overflowing) / Um, just like this, you’re so good, so good to me

Pssst…

Want a downloadable copy of this post?

Want super early access to posts just like this as well as other exclusive rewards/content?

Check out my Patreon page for more info!

#red velvet#korean#korean vocab#korean grammar#korean studyblr#korean langblr#korean learning#korean lesson#korean vocabulary#audio

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Present Perfect Passive - Rules and Examples

The Present Perfect is one of the most challenging verb tenses for English learners. It is used in certain situations and often with quite different meanings. But with some good reference at hand and regular practice, you can easily get into using it! Let’s review when we should use the Present Perfect in the Active voice and then see how it can be used in the Passive.

Present Perfect: meaning

First of all, let's see what Present Perfect means. The Present Perfect tense denotes an action or state that occurred at an indefinite time in the past (e.g., we have met before) or began in the past and continued to the present time (e.g., I’ve worked here for five years). These actions have started in the past but continue up to the present moment.

image via https://parentingpatch.com/past-perfect-passive-english-verbs/ See? It's always related to the past and irrespective of its name 'Present Perfect' expresses a past event. But why is it called "Present Perfect"? Present Perfect is called like that because it combines the present grammatical tense (she has) and the perfect grammatical aspect (done). The Present Perfect is used to denote a link between the present and the past. It expresses actions in the past that still have an effect on the present moment. My new bicycle has been delivered already, so now I can ride it all day long.Your dog looks sad, has it been fed today?Old chairs in the hall have been replaced with the new ones. The time of the action is before now but not specified, and we are often more interested in the result than in the action itself. Why is she sad?She has read your letter. Why are you going outside?My boyfriend has arrived. Use of time expressions The Present Perfect uses time adjuncts referring to the present and does not allow the use of time adjuncts referring to the past. We have completed our project by now.We have finished our work last week. (incorrect)We finished our work last week. (Past Simple should be used instead)

Present Perfect: structure

Let's revise how Present Perfect Active is formed. The construction of the Present Perfect is simple. The first element is the auxiliary (helping) verb 'have' or 'has' depending on the subject the verb is connected with. The second element is the past participle of the verb.

via https://www.onlinemathlearning.com/present-perfect-tense.html In most cases (for regular verbs), to form the Past Participle we add ‘-ed’ to the base form of the verb: to listen → listenedto like → likedto drop → dropped See spelling rules for verbs when adding ‘-ed’ here. Some common verbs in English have irregular Past Participle forms:- go - went - gone - be - was/were - been - feel - felt - felt, etc. You should remember them or consult a dictionary or irregular verb list. Read the examples with Present Perfect: We have worked here since 2008.We have seen this movie already. I have made you a cup of tea.He has cut his finger.

Present Perfect: usage

When is the Present Perfect tense used? Present Perfect tense for unfinished past We may use the Present Perfect to talk about actions or events that started in the past but continue to the present or to describe something we have done several times in the past and continue to do: I’m a teacher.I started teaching five year ago.I’ve been a teacher for five years. I have a bike.My Dad gave it to me a long time ago.I’ve had it for ages. Present Perfect tense with 'just'/'already' and 'yet' We use the Present Perfect to talk about actions or events in the past that still have an effect on the present moment. These actions have started in the past but continue up to the present moment. We can use ‘just’ or 'already' to talk about something that happened a short time ago: I have just came from school.They have just cooked dinner. We often use ‘yet’ with negative and question forms of the Present Perfect. It means something like ‘until now’. It usually comes at the end of the sentence. Has he arrived yet? I haven’t seen Susan yet. Present Perfect Tense for Experience We use the Present Perfect to ask about life experiences. We often use the adverb ‘ever’ to talk about experience up to the present: I’ve been to India twice.She hasn’t eaten sushi. This tense expresses actions of duration that occurred in the past (before now) but are of unspecified time: Tom has been to London. Have you ever met George?Yes, but I’ve never met his wife. Other common usages of Present Perfect are: To put emphasis on the result: – She has broken a cup.To express an action that started in the past and continues up to the present: – I have worked for this company for 10 years.To talk about life experiences: – I’ve never traveled alone.To say about an action repeated in an unspecified period between the past and now: – I have visited them many times.When the precise time of action is not important or unknown: – Someone has stolen my bike! Remember: the focus of the Present Perfect is mainly the result we have in present. We've revised the Present Perfect tense in the Active voice. Let's see what's the difference between Present Perfect Active and Present Perfect Passive.