#an incredibly fraught transitional period

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I’m glad Joanna Newsom isn’t on Spotify because The Milk Eyed Mender is so powerfully and painfully evocative of a very bittersweet time in my life that I have to treat it as a rare and expensive bottle of wine that requires a half day’s journey by foot to the wine cellar of an eccentric old man who will allow me to drink the wine, but I may only do so if I sit crosslegged on the earthen floor of his in-ground wine cellar, which he dug by hand, and he closes the wooden hatch over my head and latches it from the outside so I can give the wine and its intricate symphony of notes the proper attention it requires, alone in the dark, and dank, and scent and quiet, and he comes back in a few hours to let me out and hand me a soft cotton handkerchief embroidered by his late wife (he has been a widow for 15x the length of time he was ever married) so I can clean the tears and loam from my cheeks. Aka I have to let it play from the YouTube browser website from my phone and can’t do anything else throughout.

#or whatever#you can imagine how exhausting it is to be my friend in real life. there come times when I watch my loved ones’ eyes glaze over in real#time#basically there was a Milk Eyed Mender vinyl in an incredibly specific few week span of my life#an incredibly fraught transitional period#and it makes me so powerfully sick to listen to#so thank you joanna newsom for that decision bc though I sometimes would love to have it easily accessible…it really hurts LOL!

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite boxing writers, Malissa Smith, has finally published a sequel to her book on women’s boxing history!

The Promise of Women’s Boxing: A Momentous New Era for the Sweet Science is now available!

The must-read book on the rise of elite women’s boxing

On April 30th, 2022, the first boxing super-fight of the era, headlined by two women and fought at Madison Square Garden, lived up to its hype and then some. The two contestants fought the battle of their lives in front of a sold-out crowd and garnered 1.5 million views through online streaming. It was the culmination of a long, three-centuries arc of women’s boxing history, a history fraught with highs and lows but always imbued with the heart and passion of the women who fought.

In The Promise of Women's Boxing: A Momentous New Era for the Sweet Science, Malissa Smith details the exciting period from the 2012 Olympics through the true “million-dollar baby” women’s super-fights of 2022 and beyond. Rich in content, the stories that emerge focus on boxing stars new and old, important battles, and the challenges women still face in boxing. Smith examines the development of the sport on a global basis, the transition of amateur boxers to the pros, the impact of online streamlining on the sport, the challenges boxing has faced from MMA, and the unprecedented gains women’s boxing has made in the era of the super-fight with extraordinary seven-figure opportunities for elite female stars.

Featuring the stories of women’s boxing icons Katie Taylor, Amanda Serrano, Savannah Marshall, and more, and with a foreword by two-time Olympic gold medalist and three-time undisputed champion Claressa Shields, The Promise of Women’s Boxing offers unprecedented insight into the incredible growth of the sport and the women who have fought in and out of the ring to make it all possible.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Border: Arabela's Journey Through Adolescence

"Adolescence is a border between childhood and adulthood. Like all borders, it’s teeming with energy and fraught with danger." - Mary Pipher

Mary Pipher's quote captures the essence of adolescence perfectly—this "border" is a dynamic space, alive with both opportunities and challenges. It’s a time of incredible growth, where individuals balance between who they have been and who they are becoming.

Adolescence is a time of transformation and self-discovery. It is the phase of life when we transition from childhood to adulthood, and it is marked by a rollercoaster of emotions, experiences, and growth. During this period, teenagers are in a time of both confusion and clarity. It is a time when we question the world around us, explore our identity, and strive to find our place in society

This phase isn’t just a transition; it’s a journey of self-discovery, where each experience and each emotion contributes to the foundation of adulthood. Every challenge faced during adolescence, every question asked, and every boundary tested all play a role in shaping who they will eventually become.

Arabela, a 17-year-old Grade 12 student at Davao Doctors College. She enjoys drawing, watching anime and reading manhwa, reading books, and writing short stories. She stands out for her authenticity and simplicity. Though she may initially appear shy and reserved (demure), she is genuinely engaging when she shares her experiences. As she navigates adolescence, Arabela openly reflects on the changes and challenges that come with this stage, offering thoughtful insights into her journey of self-discovery. Her ability to communicate her thoughts and feelings highlights her growth and resilience, as well as her curiosity about understanding herself and the world around her.

As she approaches the end of her high school journey, she is navigating the challenges and opportunities that come with being on the cusp of young adulthood. Her studies not only prepare her for academic success but also shape her ambitions and aspirations for the future, providing a foundation for her to pursue her goals with resilience and determination."

Physical Milestone (Puberty, Height/Weight, Exercise and Nutrition and Sleep)

At 17, Arabela is experiencing the physical changes that come with adolescence, when Arabela was asked about her experiences during puberty, she noted that she has noticed some recent changes in her height and body shape. She mentioned that during her junior high school years, she always sat at the front of the classroom, but now she finds herself seated at the back, where the taller students are placed. Additionally, she shared that her breasts have enlarged. Arabela reflected on her childhood, recalling that she was quite thin and participated in feeding programs due to her weight. Despite these changes, she mentioned that she has not gained significant weight since she was a child, which she attributes to her genetics or heredity from her parents.

When asked if there have been any changes in her appearance, such as her skin, hair, or voice, Arabela replied that her voice has remained unchanged. However, she did experience acne breakouts during this period. In response to a follow-up question about how she handles these changes, she discussed her skincare routine. Arabela emphasized that she applies skincare products to maintain her skin’s health and freshness, indicating her proactive approach to managing the challenges associated with puberty.

Arabela also experiences the challenges of menstruation. When asked about the age at which she first experienced menarche, she shared her experience as part of adolescence that brings difficulties, including the pain and fatigue that often accompany her menstrual cycle.

She described these sensations as sometimes overwhelming and unexplained, making it harder for her to focus on her studies and daily activities. Despite these discomforts, Arabela is learning to navigate this aspect of her adolescence. She understands that these experiences are common among her peers, and she seeks ways to manage her symptoms, such as practicing self-care and ensuring she gets enough rest during her cycle.

Through this process, Arabela is beginning to appreciate the importance of listening to her body and taking the necessary steps to care for herself. While the physical changes of adolescence can be challenging, she remains resilient, knowing that these experiences are part of her journey toward becoming a young adult.

Regarding the physical changes that have surprised her the most, Arabela reflected on the rapid growth she has experienced. She mentioned that her hair, which was once curly or frizzy as a child, now flows naturally as she has entered adolescence. This transformation has allowed her to embrace her evolving sense of self.

Finally, when asked how she feels about the changes in her body shape and appearance, Arabela conveyed that she is not shocked by these changes. While she did not mention any specific aspects that she has come to appreciate, she expressed that she views these transformations as a normal part of growing up. Arabela embraces her experiences as integral to her journey through adolescence, acknowledging that what she is going through is manageable and a natural aspect of her development.

As we asked Arabella regarding Nutrition and Physical Activities at this stage, During the interview, Arabela discussed her weight and eating habits, reflecting on the changes she has experienced. When asked, “Have you experienced any changes in weight or appetite recently? What kinds of foods do you find yourself craving more?” She shared that during her early childhood, her meals primarily consisted of rice and a main dish at every breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Now, at this stage in her life, she finds herself craving snacks after meals, particularly biscuits, fast food, and sweet drinks. Despite these cravings, she also makes a conscious effort to include fruits in her diet, maintaining a balance between unhealthy and healthy foods.

The interviewer further inquired, “Have your eating habits changed recently? Are there any foods you find yourself craving more, or ways you’re focusing on staying healthy?” Arabela replied that her eating habits have remained relatively consistent, although she is more aware of her cravings.

When asked whether she is more conscious about her physical appearance now than before and how it affects her daily routine or self-care, Arabela responded affirmatively. However, she noted that she has not engaged in any physical activities or exercises.

In response to the question, “What’s one way your physical strength or stamina has changed over the past year? Do you feel more capable in sports or physical activities?” Arabela expressed that she easily gets tired when performing exercises or engaging in any physical activities.

Lastly, when the interviewer asked, “How do you feel about your overall health, fitness, and energy levels these days?” Arabela shared that she feels more productive and healthier than before. In her childhood, she would often fall ill, but now she believes she is better equipped to manage her health and resist illnesses. This newfound resilience marks a significant change in her overall well-being as she navigates through adolescence.

Now in the last part regarding her sleep, the interviewer when asked about her sleep patterns, Arabela described the changes she has experienced over time. During the pandemic, she often went to bed between midnight and 2 a.m. However, now that she is older, she typically goes to sleep around 11 p.m., especially when she feels tired after finishing her workload. She recognizes that when she begins to feel drowsy, it’s a clear indication that it's time for her to rest.

In a follow-up question regarding her sleep pattern, the interviewer asked, “Do you find it easier or harder to get enough rest? What helps you feel rested during this time?” Arabela explained that she has maintained this routine; when she feels tired and drowsy, she prioritizes sleep as a way to recharge from her busy school activities and responsibilities. This commitment to getting adequate rest is crucial for her to manage her workload and maintain her overall well-being as she navigates the challenges of adolescence.

Arabela's physical development during adolescence is characterized by significant changes that mark her transition into young adulthood. At 17, she has grown taller, moving from sitting in the front of her class to the back with her taller peers, and has experienced breast enlargement. While she has encountered challenges like acne, she actively manages her skincare routine. Although her weight has remained stable, her eating habits have shifted; she now craves snacks like biscuits and fast food, alongside fruits for balance. Despite feeling more self-conscious about her appearance, she hasn't engaged in regular physical activities, often feeling fatigued. Nevertheless, she reports feeling healthier and more resilient compared to her childhood, with improved sleep patterns as she prioritizes rest. These changes reflect the complex nature of adolescence, where physical growth, diet, and self-awareness intertwine.

Cognitive Milestones (Formal Operational Stage: Hypothetical-Deductive Reasoning, Adolescents Egocentrism: Imaginary Audience and Personal Fable. Cognitive Control, Emotional Decision-Making)

Arabela, as she’s at 17-years-old. She is navigating the complexities of her cognitive development, particularly as she transitions into the formal operational stage. When asked about a time she solved a problem using abstract thinking, she was presented with a complex scenario: “If you had the power to change one thing in your school, what would it be and why?” Arabela took a moment to consider the implications of her decision, outlining how her proposed change could foster a more inclusive environment for students. This exercise allowed her to explore hypothetical outcomes and the reasoning behind her choices.

In another instance, she reflected on a situation where imagining different outcomes helped her make a decision. When presented with the hypothetical scenario of choosing between morning and afternoon school sessions, Arabela weighed the pros and cons of each option. She expressed a preference for morning sessions, as they would allow her to have more time in the afternoon for extracurricular activities, illustrating her capacity for future-oriented thinking.

She understood that proper planning and reasoning are essential to navigate through challenges effectively. She is a very future-oriented person who always makes plans for her future. Whatever happens in the present, she considers how it might affect her future, often making extensive revisions and setting new goals to align with her future aspirations. She frequently states that her future is more important than her current goals, preferring to focus on long-term plans rather than immediate objectives. Adolescents often engage in extended speculation about ideal characteristics—qualities they wish to embody and see in others. Such thoughts lead them to compare themselves with others based on these ideal standards, and their reflections often become imaginative journeys into future possibilities.

However despite her wit and capabilities for critical thinking she also experiences things like the Theory of Jean Piaget about “Adolescent Egocentrism.” As an adolescent, she sometimes feels like everyone is watching and judging her actions. This self-consciousness was especially evident during a painting project where she feared criticism from her peers. Reflecting on this, Arabela acknowledged how her perception of others’ judgments influenced her behavior, demonstrating the concept of an imaginary audience that often accompanies adolescence.

For her Cognitive Control (Cold-Executive function), To cope with distractions while studying, Arabela shared that she uses headphones to block out noise, even without music, indicating her awareness of the importance of focus. She described a strategy for managing interruptions, such as putting her phone out of reach during study sessions, highlighting her development of time management skills this

However she mentioned her vulnerability when making choices. For her Decision-Making (Hot Executive Function), Arabela illustrated her emotional decision-making skills when giving her a scenario where she faced a strong emotional reaction during a school event. When a friend dared her to participate in a risky activity, she considered the excitement to join the activity versus the potential consequences, reflecting her emotional impulses. She spoke about peer pressure and how it sometimes leads her to engage in risky behavior to fit.

At 17, Arabela exemplifies the Formal operational stage of cognitive development, engaging in abstract thinking and hypothetical reasoning. Her reflection on potential school changes demonstrates her ability to evaluate outcomes and consider future implications. While she effectively weighs options, such as preferring morning classes for more afternoon time, she also experiences adolescent egocentrism, feeling scrutinized by peers. This self-consciousness is evident during a painting project, highlighting the imaginary audience concept common in adolescence. Arabela employs cognitive control strategies, like using headphones and minimizing phone distractions to enhance focus. However, she admits vulnerability in emotional decision-making, especially when faced with peer pressure, balancing excitement against potential consequences.Overall, her experiences reflect the complexities of adolescence, where cognitive, emotional, and social factors intersect, shaping her journey toward maturity.

Socioemotional Milestones

Arabela's socioemotional development is marked by a complex interplay of self-esteem, self-regulation, self-identity, spiritual development, family dynamics, and friendships. Recently, she has been grappling with feelings of inadequacy, describing her self-esteem as fluctuating. She admits that she hasn't been performing at her best academically, which contributes to her lack of confidence. However, she finds pride in her patience and intelligence, qualities that help her maintain a positive view of herself even in challenging times.

When faced with stress or overwhelming situations, Arabela employs reading as a coping mechanism, finding solace in books that allow her to calm down and regain focus. Reflecting on her growth, she recognizes a shift in how she manages emotions and impulses compared to her younger self. Unlike before, when she was more open to sharing her feelings, she now prefers to navigate challenges more privately, indicating a maturation in her self-regulation.

In defining her identity, Arabela acknowledges that her interests and values play a significant role. She expresses a desire to explore new experiences, yet admits that she can be easily influenced by the opinions of others. This struggle to assert her self-identity sometimes leaves her feeling uncertain about where she fits in, a challenge she navigates by seeking activities that resonate with her interests and values.

Arabela's spiritual beliefs also contribute to her sense of self. She embraces a “go with the flow” attitude and actively participates in church activities, which provide her with a framework for her values and decision-making processes. These spiritual practices help her ground herself amid the chaos of adolescence.

Her relationship with her family is supportive, although she experiences some boundaries that occasionally hinder her independence. While she appreciates her family’s guidance, she feels pressure to conform to their expectations, leading to occasional conflicts over her time and priorities. Resolving these conflicts can be challenging for her, as she often struggles to find effective communication strategies.

Arabela's relationship with her parents is characterized by an understanding that, while they are supportive, their busy work schedules often leave little room for open communication. Although conflicts arise, they are not typical arguments; instead, disagreements stem from the pressures of time and responsibilities. Arabela recognizes that her parents' demanding jobs mean they have limited time to engage with her on various issues, which can create a sense of distance.

Interestingly, because there are no significant conflicts or arguments in her household, Arabela has not developed specific strategies for resolving disagreements. Instead, she navigates her relationship with her parents by being patient and understanding of their circumstances. She tries to make the most of the moments they do share, finding ways to connect when they can. This approach allows her to maintain a positive relationship with her parents, even amid their busy lives.

Friends play a crucial role in Arabela’s life, providing emotional support and encouragement. She values her friends for their patience and ability to lift her spirits, which significantly boosts her self-esteem. However, she also feels pressure from her outgoing peers, which sometimes challenges her sense of self. Reflecting on her friendships, she recalls a specific challenge in seventh grade that tested her relationships, emphasizing the importance of open communication in resolving conflicts and maintaining strong bonds.

When it comes to dating and romantic relationships, Arabela feels she needs more personal development before committing to a relationship. Although she hasn’t encountered challenges or rewards in romantic experiences yet, she understands that as she matures, navigating these relationships will require her to balance her emotional readiness with her desire for connection.

Overall, Arabela's socioemotional journey reflects her continuous efforts to build self-esteem, regulate her emotions, define her identity, navigate family dynamics, and cultivate friendships, all while preparing for the future that lies ahead.

Challenges, Satisfaction and Lessons

Arabela currently grapples with significant pressures that stem from various sources, including academic expectations, social dynamics, and family responsibilities. The weight of these pressures often affects her daily routine and mental well-being, as she feels compelled to meet the high expectations set by those around her. This constant pressure can be overwhelming, leading to moments of stress and self-doubt as she navigates her responsibilities.

Setbacks and disappointments are part of her journey, and Arabela describes how she handles these challenges with a sense of resilience. When faced with failure, whether in academics or personal projects, she takes time to reflect on what went wrong and adjusts her plans for the future. This ability to revise her approach demonstrates her developing capacity to learn from experiences, adapt, and move forward despite obstacles.

Despite these challenges, Arabela finds pride and satisfaction in her accomplishments. One of her most notable achievements came during her Grade 11 first quarter, where she excelled academically and earned the title of top student in her class. This recognition not only boosted her self-esteem but also served as a reminder of her capabilities amidst the pressures she faces.

However, when asking about her feeling being in her stage, she stated that she’s feeling confused with her life events and choices. Reflecting on her adolescent journey, Arabela acknowledges that this period is filled with confusion and significant changes. She often feels as though she is falling behind in certain aspects of her life, grappling with the complexities of growing up. These feelings are common for adolescents “Erik Erikson Identity role vs Identity Confusion”, this add another layer of challenge to her experience. Nevertheless, Arabela strives to find her footing, learning valuable lessons about resilience and self-acceptance along the way.

Arabela feels that her family's influence on her choices and values is significant, especially as she strives for greater autonomy. However, her parents have expressed doubts about her talents, often telling her she lacks the skills needed to pursue certain interests. This feedback has led her to question her abilities and has made her cautious in exploring new opportunities.

While she values her family's support, their skepticism sometimes creates tension as she seeks to assert her independence. Arabela is learning to navigate this dynamic by reflecting on her own strengths and interests, ultimately aiming to carve out a path that resonates with her identity, despite her family's reservations.

Furthermore, Arabela expresses feelings of confusion during this stage of her life, recognizing that she is maturing and capable of making decisions similar to her friends. However, she also acknowledges that she still possesses a sense of innocence, which adds to her internal conflict. This duality makes her feel uncertain about her choices as she navigates the complexities of adolescence.

As she strives to carve out her own path, the pressure to conform to the expectations of her peers and the realization of her own evolving identity contribute to her confusion. Arabela is in a process of self-discovery, trying to balance her youthful innocence with the responsibilities and expectations that come with growing up, leaving her feeling both empowered and bewildered.

Ultimately, her journey is a testament to the complexities of growing up, as she learns to balance her achievements with the inevitable challenges, forging her path toward self-discovery and personal growth.

During our hour-long conversation, Arabela came across as genuine, cute, and simple. We appreciated her wit, kindness, and friendly demeanor, which made the discussion feel comfortable and open. As she navigates the border between adolescence and adulthood, grappling with her identity and the pressures of growing up, we hope she finds her true path. This transitional phase is filled with confusion and uncertainty, but her authenticity shines through.

Ultimately, the border of adolescence is a powerful catalyst for transformation. It challenges young individuals to reflect on their aspirations and fears, pushing them to carve out their own paths. For Arabela, and many others like her, this journey is an opportunity to embrace their uniqueness, learn from setbacks, and emerge with a clearer vision of who they are and who they want to become. As they navigate this complex terrain, the hope is that they will find the courage to embrace their true selves and step confidently into adulthood.

“Adolescence is a period of great vulnerability and confusion.” – Louise J. Kaplan “and Adolescence is a time when young people are trying to find their place in the world, and that can be incredibly difficult.” – Mary Pipher

But remember!

“Every man is the architect of his own fortune.” – Appius and “It’s what no one knows about you that allows you to know yourself.” – Don Delillo

1 note

·

View note

Text

No Vision To Visionary: Jerry Brazie’s Journey From Struggle To Success…

➡️Listen: https://anchor.fm/richard-kaufman/episodes/From-Stealing-food-to-Millions-How-Jerry-Brazie-did-it-ekpdpj

My Hot 🥵 Take…

Jerry Brazie's life story is a vivid testament to resilience 💪, determination 🎯, and the relentless pursuit of success 🚀 against daunting odds.

Born into a bustling household with nine siblings 👨👩👧👦, Jerry's early days were fraught with challenges, from financial hardship to a severe eye condition that threatened his sight

👁️. From the tender age of 11, he was already working, learning the invaluable lesson that hard work is directly linked to survival and independence 🍽️.

Jerry's adolescence was marked by his incredible tenacity and resourcefulness. Despite facing the threat of losing his vision, he hustled pool 🎱 at 16 to make ends meet, showcasing his grit and adaptability.

This period of his life wasn't just about personal struggle but also about immense growth 🌱 and transformation, with the streets serving as both his battleground and his classroom.

Embracing entrepreneurialism at 28, Jerry's ventures have spanned over two decades, during which he's bought and sold numerous companies, amassing over $450 million in revenue 💼.

His transition from a youth marred by adversity to a successful entrepreneur highlights the essence of staying calm under pressure and addressing challenges methodically.

Jerry's narrative from poverty to success illustrates how discipline, hard work, and relentless personal development can elevate one from the depths of hardship to the heights of achievement.

In Jerry Brazie's journey, we find a powerful message of hope and inspiration 🌟.

His life reaffirms that our origins don't determine our destinies, that adversity can mold rather than break us, and that with perseverance, the most formidable obstacles can be overcome.

His path from the gritty streets to the executive boardroom embodies the quintessential American dream 🇺🇸, proving that success is earned through resilience, hard work, and an unwavering belief in oneself.

Thank You To Our Sponsors:

Tammi Moses Of The Hoarding Solution

Billy Caughey Brad Caughey Kevin Bekkr Of Double B Creates

Annette Whittenberger Of A Wild Ride Called Life

Sean Douglas The Master Of Public Speaking.

#entrepreneurmindset #success

0 notes

Photo

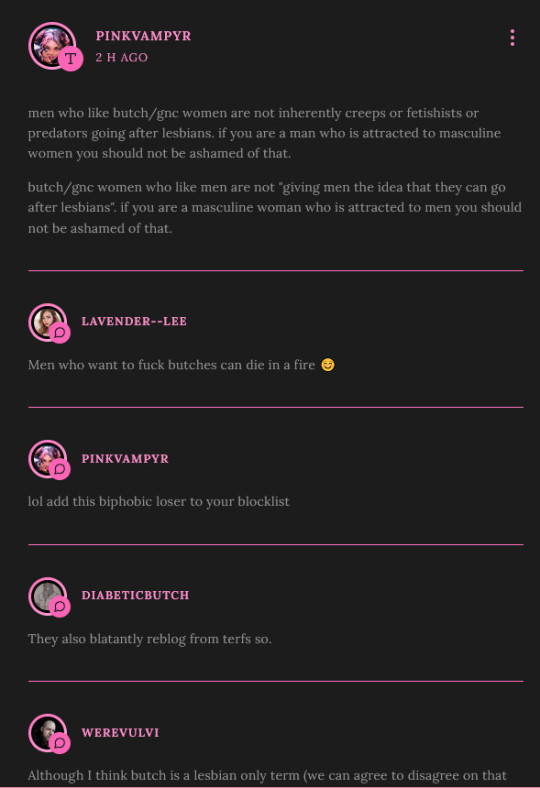

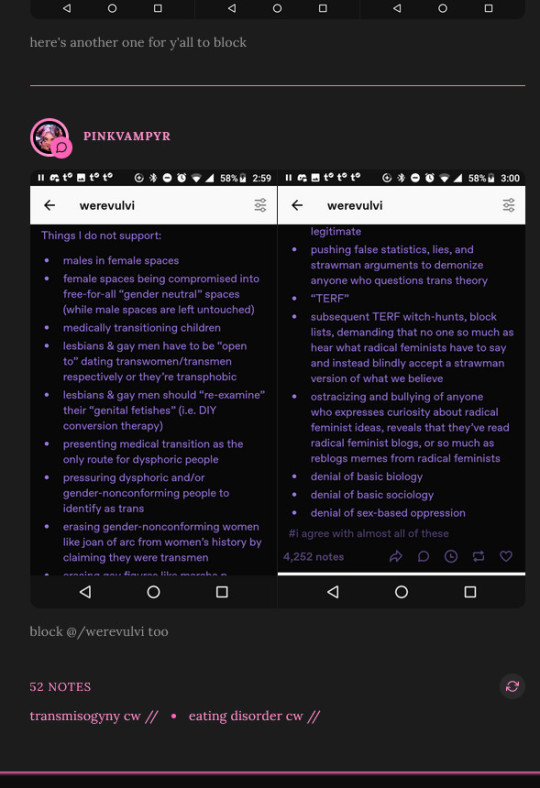

I hope these show up in the right order. This kinda stuff is exactly what makes me feel lost about my transness. Like I was just trying to be nice and agreed with this person's post. I had no interest in being an asshole or arguing what bio sex, or even what butch, is. I was just declaring myself as a bio female because it felt relevant to the topic and how I relate to it. It amazes me how even the pro self-ID types are against self-ID when someone identifies in a way that doesn't suit their narrative, even when it's a trans person whose identity they deny.

They blocked me and I don't want anyone going after them, I just wanna rant. And not even about this specific post or person, but more so about trying to exist as a gender critical trans person in general. I've been thinking about that for days, weeks, perhaps months or even years already, so it's really not about this specific person. I guess it was just what triggered me to finally start writing.

I guess I feel like both most other trans people and most other gender critical people, view transness as incompatible with gender critical opinions, and like that makes me feel pulled in two opposing directions. But anyone of any ideology can be dysphoric and transition because it helps them cope. I don't think that my opinions, or my choice to hang out with radfems, means that I'm self-hating, or even that I'm going against the needs of my own trans demographic. My own trans demographic is just all too good at confusing wants with needs... generally speaking. I see sex and gender the way I do because it makes sense to me personally, and I don't even argue that it's necessarily the objective truth. I don't think there is such a thing. It's just my truth, my perception of the world.

That I can't make myself see myself as a man for real, despite my dysphoria and transition, doesn't mean that I think it's wrong to transition, or that my body is damaged by it, or that transitioning is useless. Because it's not. I love my transition and everything it has given me. I'm comfortable with my transitioned body. It deserves love, especially my love. And although I still struggle with some insecurities, I feel like I love my body. It's been... incredibly good to me. It's stayed very healthy, and even keeping up a strong immune system despite my smoking, self harm, careless sexual escapades, etc. I may still have a fraught relationship with being female, but as long as I transition, I seem to be managing it fairly well. Except then I have a more fraught relationship with society instead. Can't win, but that's life, innit?

I don't think either my transness or my political opinions are my real problem or ever was. I think it's society's constant fighting about trans people's genders, lives and choices, that makes me constantly cave in on myself. Can't handle the pressure.

It feels like it's only ever getting worse. Ten years ago my biggest concern was people not ever finding me attractive because I was turning myself into some kind of a freak, which luckily I was proven to be wrong about. Five years ago my biggest concern was nonbinary people trying to normalize asking people their pronouns, which made me fear that people would never leave me alone about my gender, unless I forced myself to be hyper-masculine, which I still worry about. Three years ago my biggest concern was having been stripped of my sex-based rights and dehumanized for how I had chosen to treat my dysphoria, which I still worry about as well, and now...

...my biggest concerns are being treated as a third gender, fetishistic predator who should be shoved away into gender neutral spaces, and I fear that one day medical transition will be taken away as an option to treat dysphoria if transness is continued to be rejected as a medical condition. My heart rate is ever increasing. Can I even realistically "just go on with my life" anymore? I feel compelled to do something, but I also feel like there isn't anything I can do. No matter how many people I try to "educate" about dysphoria and why transition is incredibly important, all the while being as humble as I can, I am seriously lacking behind the much faster spread of harmful misinformation.

Thing is, I do not blame gender critical people for spreading some of that misinformation. For example of trans women as fetishistic predators, which people apply to trans men when they still fail to understand that MtF is not the only kinda trans there is, or when we dare to be just a little bit feminine while passing as male. If anything, I blame the true sources of such harmful claims, which slowly increase my anxious heart rate, over years, turning into decades, of living as openly trans. I blame opportunistic men who pretend to be trans women for gaining access to women's spaces, be it prisons, spas, shelters, sports, what have you, when they cannot possibly be dysphoric judging by how happily they swing their dicks around women as if it's no big deal and make no attempt at transitioning, but also who cares if they are dysphoric, no one should behave that way either way. I blame the trans rights activists who say lesbians have to suck dick if it's attached to a trans woman, and those who say that gay men have to be into pussy and date trans men. I blame those who say that trans women are bio female by virtue of identifying as female, and claiming that they can get periods, by virtue of... bowel cramps?! I'd also blame those who try to change female specific language on behalf of shielding trans men from our own dysphoria, in the rare cases we'd end up getting pregnant or manage to drag our asses to the gyno office for a pap smear, which... most of us really don't, regardless of if you call us women or uterus-havers, sincerely, please stop. It makes people think trans women are trying to take over the term "woman" entirely for themselves, which of course they don't.

I could go on, but I won't, as this post is not about these things. It's more so about how estranged I feel from the people who spout these things, knowing that they think they're speaking for me and my supposed needs as a tranny. But I see no point in trying to educate them, as they won't listen any more to me than they would to a radfem, and again, I think this post in my screenshots shows just how unwilling they are to listen to me.

I guess living with my transition on constant display is what's hard, and I guess I just need to vent about that, as it's always judged one way or the other; as either me having made myself into a man, or that I'm a delusional woman who mutilated herself; and it's kinda hard to find a kind and sane middle ground, that perhaps I'm just a victim of circumstances, and trying to make the most of my own life, regardless of what the fuck I am. That social shit, on top of dealing with dysphoria, makes it really difficult to not hate myself, I guess. But I have tried to live stealth and that made it if possible even worse, as it felt like I was lying, keeping a huge secret that grew in me like a spreading virus.

What I want is to just live my life, and for neither my bio sex, nor my transition, to stop me from doing that. I want to work through the worst of my autism, enough to be able to pursue a career in some low-paying labor, blue-collar job; get a car and driver's licence, find a suitable husband to have a child and cats with; I want my own garden, an art studio; I want to build muscle to become strong and even more independent (and perhaps strong enough to carry that husband, but at least to carry myself), and so on. When I picture myself in that potential future, it is with this male-like appearance I transitioned my body into, but it is also as a mother and wife.

And thinking about all of that makes me happy, it makes me smile and feel joy, meaningfulness, hope... While thinking about arguing online with some miserable fuck, who's deadset on arguing semantics and calling me a terf, when all I wanted was to show a little bit of kindness, that "hey, I agree with you, you make a good point here, and I'm not here to fight" only to be spat right back into my face... just makes me feel sad. Whatever happened to diversity of opinion? It's gone, it became labeled as bad, and left people like me with no place to be.

There is no point in arguing with such people, or even trying not to argue. There's no winning in that, there's no reward, no accomplishment. It's better to walk away.

I know I just have to get over this, this inner conflict of going against my transness with my gender critical opinions, and that I'm going against my womanhood with my transition - and be stronger than the political climate that's pulling me into pieces. But if it's peace that I want... I can just forget about it. There's no road there. But I have trouble letting go of that simple dream. The internet is constantly manipulating me into thinking I have an exciting social life, when in fact it's non-existent, and the lie is destructive. With internet vs real life, I'm living a double life. One of those lives has a future, the other one does not.

I'm glad I made this rant. It actually made me feel better, and reminded me that it's still worth it. Being trans, moving forward, focusing on what is good and what can become good in life. And it reminded me that the internet is merely an imitation of life, a substitute for human connection, and can... as with much else, be both good and bad.

#discourse#venting#tired of being pulled in opposing directions#because im not the right kinda trans#or the right kinda feminist#i have to live with myself and i dont know how#focusing back on what actually matters in life#just thoughts#gender politics#ok to rb

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Under the Stars.

On the UK release of Harry Macqueen’s tender Supernova, the writer-director talks to Ella Kemp about timeless love stories, his favorite screen lovers and working with best buds Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci.

Love is patient and love is kind in Supernova, Harry Macqueen’s tender story of marriage, memory and maps. It’s an autumnal study of a mature, rock-solid love and the unfair illness that threatens to undo it. We’ve seen stories about gay lovers that end in tragedy before, but this one is different: a sense of security and trust infuses the final holiday of husbands Sam and Tusker, as they come to terms with Tusker’s recent diagnosis of early-onset dementia.

Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci play the couple—a pairing written in the stars, since the actors have been best friends for twenty years—who are traveling England in an RV, visiting places and people they have loved. Sam is a pianist, Tusker a star-gazing novelist. Together, they mine emotions that manifest in everyday care rather than grand, theatrical gestures. Julien describes Supernova as “a marvel of tiny moments that feel so real they register like bullet wounds,” while Lola feels the destabilizing power of these lovers. “I love love,” she writes, “but love is painful, beautiful, heart wrenching, frightening and forever.”

Supernova is the second feature from Macqueen as a writer and director after 2015’s Hinterland, in which he starred opposite Lori Campbell in a contemporary, rural tale of a companionship that spans decades. A London-trained actor, he made his debut in the under-seen Richard Linklater film, Me and Orson Welles. On Supernova, however, Macqueen remains firmly behind the camera.

The filmmaker opened up about the stars in the sky, the ones on our screens, intimacy, pride and more for his Life in Film questionnaire.

Harry Macqueen on location with Colin Firth for ‘Supernova’.

What do you think the connection is between stars—the celestial kind—and lovers? Harry Macqueen: Historically, we’ve always found the cosmos to be both perplexing and inspiring. I suppose there’s a kind of infinite beauty in space that is definitely related to love, and especially for a character like Tusker, who is contemplating his mortality. He’s looking up at the stars and thinking about what they mean, and what he means in that context, and it seemed like something that would be a natural thing to do if you were in that situation.

In terms of the other kind of stars—your incredible actors Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci—how did you find the right people to bring Sam and Tusker’s love to life? I think that what they do in the film is very surprising, in a way that’s beautiful and delicate. But it was also one of the easiest casting processes of any film, ever. Stanley was the first person we sent the script to and he read it very quickly and responded to it in the way that you hope that people will. We were really interested in one of the characters being not British—we felt there was something potentially quite stuffy about having two Brits bumbling around the countryside, so another culture would add a bit of a different energy to it.

Stanley loved the script and we got on really well. I really wanted, hopefully, to get two actors who knew each other and had a shared history for these intimate roles. And he said, “I don’t know whether you know, but my best mate is Colin, and I could get the script to him.” I obviously said yes and he said, “Okay, well, I already have, and he loves it and he wants to meet you.” So it was all a bit of a dream!

Let’s talk about the inception of the script. Supernova is obviously a story about love, but it’s about illness and death and mortality and all of these things, which feels significant in terms of it being a gay love story. A lot of queer love stories in cinema are tragic, but also are often very specifically reckless and youthful, and don’t really linger on this later chapter in life. How early did you know, then, that this film would be about two men? If you’re talking about early-onset dementia, you’re naturally talking about people in their fifties or sixties, so I knew that I was always going to tell a story about romantic love of some kind in that part of your life. I had done a lot of research around that, and I realized I had never worked with a same-sex couple. All the couples and families that I’d worked with, the central relationship had been a heterosexual one. So my initial reaction was to write that story, but then I countered that really quickly and wanted to challenge why that was my initial inkling.

I just thought, I’m writing about really universal themes—love and death and life and trust and companionship—and it seems to me that no one sexual orientation or gender has a monopoly on those things.

And you’re right, LGBTQ+ cinema over the years, quite often for very, very important and understandable reasons, has been about that period of flux, transitioning or coming out, the moment of becoming your true self at a certain time of life, when you’re usually quite young. And that is quite fraught, frantic and a bit grimy sometimes. So I was aware that there was a gap in cinema to present a love story about two people of the same sex who were in this stage of life. That romantic, mature love we don’t talk about very often.

The film also aspires to be the type of story in this type of community that I hope that I live in, even if perhaps I don’t—to tell a story in which the sexuality of the characters isn’t mentioned. It’s just accepted, embraced and loved. The sexuality of the characters doesn’t impact the story or inform anything, it’s just their lived experience in the world. I’m really proud that we did that, because I genuinely think, in its own tiny way, it’s a revelation.

Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci navigate love and illness in the Lake District.

This film, materially and aesthetically, is beautiful. The landscapes, the actors, Sam and Tusker’s knitwear. How did you navigate the balance between creating this very cozy world that also understands heartbreak and decay as potent things? What I want to try and do in films generally is wrap an audience up in an intimate world between two people, and hopefully allow the audience to fall in love with those people. That shared history they have meant that all of these things felt quite organic. They’ve got some money, but they’re in a camper van, they’re not loaded. They’re reasonably creatively successful, but they’re not famous, necessarily. They’re just two guys trying to live under quite extreme conditions.

The intimacy in the film is really, really important to me. What degree of romantic intimacy these characters have, how you film that, and how you plonk an audience in there. Because you don’t want to make a dirge—the film is life-affirming because they love each other so much, and because of that, it’s also devastating.

So that informs every choice you make stylistically. It’s quiet, and it’s patient, and it felt like exactly the right way to tell this story, to not intrude on this beautiful relationship, to not impose anything on it, to be very simple, really—which, as I’m sure you know, it’s not simple!

I know that kind of filmmaking is not to everyone’s taste, that avoidance of melodrama, that lightness of touch. I find it beautiful, but others probably don’t.

Gordon Warnecke and Daniel Day-Lewis in ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’ (1985).

Now, a few Life in Film questions. Who are your favorite gay lovers on-screen? Carol and Therese in Carol, Russell and Glen in Weekend, Marianne and Héloïse in Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Johnny and Omar in My Beautiful Laundrette.

What is your favorite timeless love story? This is so difficult! Maybe Alice in the Cities, Wendy and Lucy or the Before... trilogy.

What is the best film about pride, the definition of which is very much open to interpretation? Jiro Dreams of Sushi—a brilliant film about having pride in your craft.

What should we watch after Supernova? I tend to be a bit controversial and say the couple from Amour by Michael Haneke. Or maybe Life of Brian, or a Studio Ghibli film—but definitely not Grave of the Fireflies.

What was the film that made you want to be a filmmaker? I’m not certain there is a specific one, but there are films you encounter all the time that make you want to be a filmmaker all over again. The two films that made me think it might actually be possible were Old Joy and Katalin Varga—they inspired me before I had any budget or experience. But it could also be any Yasujirō Ozu film, or Taste of Cherry by Abbas Kiarostami. All very inspiring in their own way.

Related content

Queer Love and Desire: a list by the Criterion Channel

The Pride of Sundance: 400 LGBTQ+ films to watch this June, curated by the Sundance Film Festival

101 Must-See Movies for Lesbians: Jenni Olson’s list (including Carol)

Follow Ella on Letterboxd

‘Supernova’ is in UK theaters now, and available to stream on Hulu, or rent/buy from other VOD services in the US.

#harry macqueen#supernova#queer love#queer film#queer cinema#pride#pride 2021#gay film#colin firth#stanley tucci#early-onset dementia#road movie#letterboxd

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exit Review: My Country

Synopsis

This drama is set in the transition between the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, and follows turbulent friendship turned fraught rivalry between Seo Hwi and Nam Seon Ho. Seo Hwi’s late father was the greatest swordsman of Goryeo, but after being framed for embezzling military supplies he was executed as a traitor, a stain which hangs over Hwi and his sister’s lives. Seon Ho is the illegitimate son of a powerful state official, but due to his mixed parentage he can never fully belong to his father’s world and has an insatiable ambition and bitter resentment toward his father which drives him.

Hwi and Seon Ho have been close since childhood, but when they end up going head to head in the state military exam a tragedy follows that will drive a terrible wedge between them. Eventually circumstances will force them to pick sides between General Yi Seong Gye (the first King of Joseon) an his ruthless son, Yi Bang Won, in the fight which will give shape and purpose to a newborn country.

Review

Story: My Country is a difficult drama for me to review objectively, in part because I loved it so much. Watching this drama was a truly absorbing and gripping experience for me, and it plays to so many of my story preferences. I was unequivocally obsessed with this drama from the premier to the finale, but during the weeks between airings I couldn’t help but feel like I was arm wrestling with the script.

It was characterization more than anything that gave me fits. I wouldn’t go so far as to accuse the show of giving us thin or two dimensional characters. To the contrary, each of these characters has a fully realized matrix of conflicting desires, loyalties and ambitions that inform their choices and alignments. However, it is often difficult to sift through those murky motivations and draw a clear line between a character’s internal desires and their external actions.

This drama starts out with an incredible cold open that raises all sort so questions about who these characters are and immediately invests you in finding out how they ended up in this situation. It’s truly masterfully done, and I probably rewatched it upwards of 10 times through the run. It kept me asking those questions all the way until the pay off. But because the writers were so invested in keeping their cards close to the chest, clear characterization was sometimes lost in the shuffle.

That said, this drama really is one beautiful, tragic escalation after another. Just taking the first two episodes in isolation is quite a ride. I really thought after the first few weeks, or hell, the first half, that the drama would get bogged down in plotting and politics or have nowhere left to go, but to my great joy it really doesn’t let up a single moment until the finale.

Acting: Where to even begin with the acting in this drama? All three of the main male leads: Yang Se Jong, Woo Do Hwan and the inimitable Jang Hyuk are perfectly cast and give inspired performances. Everything from posture to voice to subtle microexpressions is so stunningly on point.

I came into the drama already a big fan of both Woo Do Hwan and Jang Hyuk as actors, having followed them through other projects, so it wasn’t surprising to me that I liked them both here as well. However, what did surprise me was the extent to which they were able to show off their range and talent. As a long time Jang Hyuk fangirl, I would confidently argue that this particular rendition of the Yi Bang Won character is him at his absolute best. I also went into My Country relatively indifferent to Yang Se Jong, or at least not overly familiar with or impressed by his previous work. I’m happy to announce that that is no longer the case, as his performance of Hwi is one of the most memorable of the year for me, and his sheer level of commitment to the role is awe inspiring. There’s a video of him talking behind the scenes about a moment early on where he actually yelled himself hoarse embodying a moment of panic and grief, which made me appreciate the level thought and effort he put into playing this character.

I don’t want to limit my praise to just that trio of actors either, because the entire cast is incredible. I didn’t know much about Seolhyun before this role, but I thought she was really strong as well, though her character doesn’t feature as heavily as one might like or expect from the promotional material around this drama. The villains too are captivating, especially the detestable Nam Jeon played by veteran actor Ahn Nae Sang. Wow, you are really going to love to despise this guy. I just cannot say enough about the performances from top to bottom, because we would be here all day. The acting is really what makes the drama, especially the stunning chemistry between the characters, and more specifically the chemistry Yang Se Jong has with all the other leads.

Production: There is some movie quality cinematography throughout this drama. It just looks very, very good both in the way it is shot and the attention to detail, the props, the costumes the sets. There is a beautiful long tracking shot following Hwi through a battle field in episode 3 or 4 that was just jaw dropping. It really felt like they were flexing, honestly, and it’s refreshing to see this kind of cable quality coming out of South Korea and ending up on American Netflix for people to watch and appreciate.

I love the music in this drama. Some of it can come across a bit camp, like the electric guitar and strings heavy instrumental “My Country” that accompanies many of the sword fight scenes, but I loved Bang Won’s wailing violin theme music every time it showed up, and the OST definitely sets a mood.

One of the more distracting choices the drama made was to allude to certain historical characters like Poeun, Sambong and Choi Young but never have them actually appear as characters, in the present or in flashbacks, opting to address certain important events and philosophies through fictional expys such as Nam Jeon and Seo Geon instead. They even resort to filming certain scenes in strange oblique ways so that we understand Sambong is in the room but we don’t see his face.

The only thing I can figure is the writers wanted to use the audience’s familiarity with these historical figures without chaining the story too closely to the actual flow of historical events. Or perhaps they decided to exclude these characters in order to avoid too much direct comparison to the critically well-received and highly rated drama, Six Flying Dragons, which covers much of the same time period.

Feels: For me My Country watches like a bitter-sweet tragi-romantic melodrama centering on a toxic love triangle with a historical backdrop. And when I say “love triangle”, I am 100% referring to the interplay between Seon Ho, Hwi and Bang Won (my sincere apologies to poor Hui Jae) because that’s how the entire drama is structured. My Country is one of the most purely homoerotic things I’ve ever watched. If it weren’t for a few limp attempts to imply Seon Ho’s romantic interest was in Hui Jae and not his former friend, I would say “unapologetically homoerotic” but alas, South Korea isn’t quite there yet.

The romance between Hui Jae and Hwi never quite caught fire for me, though lord knows they were trying. It always felt like a side dish to the main course that the drama really wanted to serve: namely the star-crossed relationship of Hwi and Seon Ho. (And this is not meant as a dig toward those who liked the Hui Jae/Hwi romance. This section of the review is just about my subjective experience.)

There were moments where I worried, or couldn’t quite tell where the drama was taking us with regard to Seon Ho and Hwi, or where I feared everything was going to end in senseless destruction and they couldn’t successfully bring the plot to closure in just 16 episodes. But for the handful of issues I had with the writing of the drama, its final resolution was poetically, heart-wrenchingly, perfect.

My Country just pushes so many of my narrative and aesthetic buttons and plays heavily to my id. This is a drama that I’m going to be thinking about for a long, long time. I will definitely be watching it again and I will try to get as many other people to watch it as possible. I liked it that much.

Would I recommend My Country: The New Age? Yes, oh god yes. Please watch it. Watch it and then come talk to me about it. Definitely one of the best of the year.

9/10

#my country#my country: the new age#woo do hwan#yang se jong#jang hyuk#kim seolhyun#kdrama reviews#exit review

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Fëanor and Indis

Something that’s always bugged me? Indis and Fëanor’s relationship. Or rather the lack thereof of a relationship. If we go with the canon dates then Míriel died c. 1170 in the Year of the Trees when Fëanor was little more than an infant in Elven terms.

While Indis was Míriel’s closest friend. She was friends with Finwë too.

I doubt that she left Finwë alone during this period. And I suspect that she wouldn’t have left Míriel’s newborn child alone either. Indis might very well have inserted herself into Finwë’s household so as to look after Fëanor. Because something that we can’t forget is that Finwë was devastated by Míriel’s death. Canonically we’re given a hint as to how Finwë must have felt in the passage that talks about his and Indis’ marriage.

This is going to be long. So I’m putting a Read-More here.

"Now it came to pass that Finwë took as his second wife Indis the Fair. She was a Vanya, close kin of Ingwë the High King, golden-haired and tall <…>. Finwë loved her greatly, and was glad again."

That last sentence jumps out to me as particularly important. Especially the last part “...and was glad again.”

Considering that Míriel literally died of depression (general or post-partum, we don’t know) and physical/spiritual exhaustion that bit talking about Finwë’s emotional state stands out suspiciously. I have to wonder if Finwë himself might have suffered from depression after Míriel’s death.

If he didn’t just marry Indis randomly but rather that it was the result of a prolonged relationship of some sort. I suspect that Indis would have essentially moved to Tirion after Míriel’s pregnancy took a turn for the worse so as to offer Míriel her support. Maybe completing the transition after her death. Because Finwë’s alone now. His wife is dead and resting in the Halls. His newborn son has lost his mother and it’s entirely possible that Finwë was in no condition to look after his child here. Indis likely took on the task of raising Fëanáro. She might have even offered what support she could to Finwë here. Helping by taking over the day to day running of the palace’s household. Taking care of Fëanáro’s household as well. Nurses, governesses, etc. etc. Essentially becoming the Acting-Queen/Queen-Consort in absentia while Finwë mourns his loss and struggles/grapples with his grief.

I feel like Fëanáro grew up with a doting and loving but slightly distant father for a few years here (which might have had an effect on a young Fëanáro). Because Finwë more than likely took a few years to begin to recover from his loss. Míriel was gone but her memory never truly faded. Grief is a thing that cannot be underestimated or ignored. Especially in this situation. The elves came to Aman to escape the horrors that hunted them in Cuiviénen. They were supposed to be coming to a land where death among the Eldar would be a historical footnote. Míriel died, however, and became the first and last of the Eldar to (notably) die in Aman until Alqualondë. And elves bond on a spiritual and mental level. Not just physically.

This is something that can’t be underestimated.

Míriel’s death wasn’t supposed to happen.

And if it did? Then their dead were suppose to return from the Halls. But Míriel was so affected by her condition (depression/exhaustion) that she would not leave the Halls. Not even for her husband and young son. She needed the time to rest and recover. She couldn’t or at least was unwilling to subject herself to life while still fraught with the issues that had led to her death.

This is understandable and she shouldn’t be blamed for making her choice. Because it must have been a difficult one to make.

But this left Finwë to deal with the aftermath. And he might not have been up for it. He might have needed help. Indis was there. Indis who had been friends (best friends, even) with Míriel and Finwë. Indis who’d likely joked with Míriel and looked forward to her friends’ child with eagerness. Indis who was the sister of a king and was herself one of the Awakened Elves of Cuiviénen. She’d likely known Míriel and Finwë for a very very long time.

And this is where we come back to Fëanor.

Fëanor likely grew up with Indis as his honorary aunt. Someone who took on a maternal role in his life without explicitly taking on that role in his life. Fëanáro might have called Indis ‘mom’ or ‘mommy’ a few times when he was especially young and she’d have gently corrected him. Indis would have taken care of Fëanáro’s education. Carefully selecting tutors for the young prince from a list of Noldorin scholars and masters. Ever mindful of the fact that she was a Vanya and he was the prince of the Noldor and thus needed to curate his education in a direction that suited his birth.

Indis likely spoke to Fëanáro of Míriel from the very beginning. First as a baby, rocking him in her arms and singing to him songs that she’d heard Míriel sing to her swollen belly as she worked on her pieces. Mindless ditties of shining threads and jewel-tone colors and embroidering. Singing Vanyarin songs of beauty and perspective and thought that Míriel had enjoyed for their rather pretty and bright evocative turns of phrase.

Telling him bed-time stories of laughter and joy and expectation. Míriel’s grey eyes shining with mirth. Her mouth curved into an impish smile. A long-fingered and elegant hand splayed over a pregnant belly. Silver-grey hair falling in a mass of loose curls over a slender shoulder. Each strand shining and lovely. Of a bright and fierce temper that could cow any uppity noble and only gave way before her loved ones.

Drawing a blanket over Fëanáro’s chest. Míriel’s work. One of her finest and final masterpieces. Indis had spun the materials that went into the thread. Brought from Valmar the materials that Míriel needed for her jewel-toned dyes. Míriel had woven and sown the squares that sealed the goosedown. She’d embroidered the blanket itself. Her final gift to the child she’d loved and never gotten the chance to watch grow up.

We know that Míriel’s body lay in-repose in the Gardens of Lorien.

We know that Fëanor went to visit her often. Finw�� likely went as well. Not quite as often and more than likely because it was more than he could bear.

I can see Indis being the one to accompany Fëanáro when he was still young enough to want her to come with him. Before the marriage that is. Indis running a careful hand through Míriel’s hair while her other arm is wrapped around Fëanáro. Ensuring that he doesn’t run off or clamber onto his mother’s body.

Let me just say too. Míriel’s body being held in-repose could only have exacerbated Fëanor’s issues here. Especially since Finwë clearly struggled with the loss of his wife. Míriel died but she was never laid to rest. Her memory lingered on. In her husband. In her friend. Among her people as well. Fëanor never had a chance to come to terms with his loss. Especially since his loss occurred when he was a baby and thus never had a chance to properly know his mother and was instead left with her lingering memory.

I don’t doubt that Finwë loved him. But considering that he might have been struggling with depression after Míriel’s death and might have been a distant parent during those initial years of Fëanáro’s childhood. I can definitely see him trying to make up for it by overcompensating. Showering Fëanáro with affection and making time for his wants and needs. Even at the expense of his later children. And Fëanáro himself might not have recognized that Finwë was attempting to make up for those years that he couldn’t be a good parent.

If Finwë was struggling with depression here. He would definitely not have told his son. I tend to think that Finwë kept as much of Míriel’s circumstances from Fëanáro. Because it’d have been very easy for the boy to blame himself for his mother’s death and who knows how servants or nobles saw the whole situation. I can also see him wanting to keep Fëanáro in the dark of his own personal issues out of fear and worry that Fëanáro himself might be susceptible to depression as well. Plus fearing that he himself might fade from grief/depression and not wanting his son to have that on his mind.

All of this would lead to Fëanáro not understanding and not taking it well that Finwë’s immediately affectionate with his and Indis’ children. Because the thing here? It’s not Fëanor’s fault. Finwë was likely in a better mental state and was thus capable of involving himself with his younger children from the get-go. Whereas he couldn’t do the same with Fëanor himself at first.

It’s incredibly likely that Námo had informed Finwë of Míriel’s reluctance to return. Perhaps even told him that it was unlikely that she’d be ready for re-embodiment anytime soon. This may or may not have worsened Finwë’s own condition. I think that he began to lean more on Indis on a more personal level after this. For mental or emotional support. As well as realizing just how much Indis had taken on for his sake (running the palace and household/raising his son in his stead). Which could have very easily led to a far stronger connection and to marriage.

When we add all of the above to Finwë and Indis getting married during Fëanáro’s childhood? It’d be easy to see Fëanáro taking offense to the whole affair. Fëanáro likely knew that dead elves can return from the Halls of Mandos once they’re ready. Indis herself likely told him of this while relating stories of the Valar and perhaps the reasons for why the Eldar left Cuiviénen. A young Fëanáro would have seen this as a betrayal from the woman that had raised him. She’d told him all of his life that his mother loved him and his father. That she’d come back from the Halls to be his mom again and they’d all be happy.

Fëanáro could and would have absolutely taken this badly. And it’d be easy for a young boy to blame his new step-mother/formerly beloved aunt-figure rather than his father in this situation. Especially if he desperately adores his previously distant but still loving father.

This would then lead to Fëanáro resenting Indis. And Indis herself having to deal with the fact that she’s lost Fëanáro’s love and trust. Perhaps hoping that things will get better as time goes on. But knowing that they won’t once Ñolofinwë is born. Because Fëanáro likely took Findis’ birth with some ambivalence. If he was still young then he might be genuinely curious and affectionate with Findis because he hasn’t had time to internalize a lot of his issues. Plus Findis is tiny and pretty and eager to interact with her elder brother.

A brother, however, changes things. And Fëanáro was likely old enough (the equivalent of a Human 9 year old, I’d say) to realize that it changed things. One: Fëanáro’s position as Crown Prince was potentially threatened by Ñolofinwë. It wasn’t really but Fëanáro no doubt had begun to tie his father’s love and affection to the position which would eventually make him possessive of it. Two: Because Fëanáro watched as Finwë eagerly welcomed the arrival of the new baby. Watched as he didn’t struggle to connect or dote on Ñolofinwë the way he did with Fëanáro himself.

I suspect that ultimately led to his resentment of his younger siblings (Ñolofinwë especially). As well as encouraging his belief that Indis had stolen his mother’s chance at life and intended to take everything from him. Thus leading to Fëanáro possessively and almost obsessively defending his mother’s memory.

Just... give me Fëanor in the Halls of Mandos having to come to terms with his childhood and the Indis that had raised him and the woman he’d come to hate for taking his mother’s place in life as wife and mother. Maybe having a long and much needed discussion with Finwë about what occurred during Fëanor’s childhood. Having to realize that nothing had truly changed between them. He’d simply refused to see it for a very long time.

#Indis#Fëanor#Finwë#The Silmarillion#Esme's Musings#I'm sorry#This is long and rambly#but I have Feelings about Fëanor and Indis' whole general relationship#And Finwë himself of course

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

73. Alice by Heart, by Steven Sater

Owned?: Yes Page count: 267 My summary: London, 1940. Alice Spencer shelters from the Blitz in the Underground, with her dearest friend Alfred. He will survive through the night. He has to. Despite the fact that his tuberculosis is eating him alive. In a spin, Alice resorts to the last comfort she knows...their favourite book, Alice in Wonderland. My rating: 3.5/5 My commentary:

Ah, Alice by Heart. A little musical that ran for a couple of months off-Broadway, which for some reason captured my entire soul and forced me to love it unconditionally. The show’s relative inaccessibility - there’s an album out, but it’s hard to divine the story from it - means it’s actually perfect to be adapted into a novel, as this will help provide context on the show’s musical numbers for an audience who wasn’t able to experience the musical when it was being performed.

I am very familiar with this show, and so I am not the target audience for this book. Nonetheless, I got it. Let’s see how that went.

So first of all, because of my familiarity with the musical, I have to judge this as an adaption, and it fares...weirdly. See, the advantage one has with theatre is a certain sense of unreality. You can have an actor walk out onto a completely bare stage and invoke wartime London, or the far-off future, or the inner mind of a character, in a way you can’t really do in a lot of mediums. The musical uses its format to transition seamlessly between Wonderland and the real world - the first time this happens, it’s in the space of a musical number, where reality is already altered just because everyone started singing and dancing. Here in the novel, surreal passages are used when Alice transitions from reality to the dream-world, and I’m not sure it works as well. Part of the issue here is the stream-of-consciousness state of the narrative (more on that later). In addition, large swathes of dialogue are lifted verbatim from the musical - granted, 99% of people reading this wouldn’t notice, but it stuck out to me, and it was jarring when there were slight changes. (Also, he cut the stuff with the birds from Chapter Three! That’s one of the best parts!)

I have a few britpicks as well. Sater, English people don’t use ‘period’ to mean ‘full stop’. That’s an Americanism. Also, Angus is said to be from Leeds, but just sounds like a Dick van Dyke mockney, as opposed to having an actual northern accent. It’s jarring to me, as someone from the northwest of England myself. Sater’s definitely done some research - he cites his bibliography in the back - but the story could really have done with an English person reading it over for stuff like this. Plus, there’s that whole London-centric thing going on - Angus seems to be the only non-Londoner in the cast, though Harold is described as northern once but then his mum is said to be glad that he’s out of London? No idea what’s going on there. It bugs me, and I say this as someone who once spent half an hour trying to figure out if Americans use the word ‘sofa’ for a fic. I get it, our linguistic differences are small enough that it trips you up easily.

Let’s talk about Alice, who is our main character. I actually ended up liking her a lot less here than in the musical. Here, we have more flashbacks into her relationship with Alfred, which makes her look incredibly codependant. She abandons her mother after a bombing raid just to be with him. I mean, sure, it’s a fraught situation and I don’t blame her for acting emotionally, it’s just that in the show the impression I got was less ‘I devote my life to Alfred’ and more ‘I am fixated on him now because he’s literally dying right in front of me’. In addition, I was uncomfortable with the focus on her breasts and body as a symbol of her growing up. She’s 15, Sater. You don’t need to talk about her breasts every few paragraphs.

Alfred, meanwhile, is both more and less of a character in this book - more because we see more of him, less because thanks to the book’s page count, his appearances seem lesser, and more attention is drawn to the fact that the Wonderland White Rabbit version of him isn’t really him by virtue of being able to distinguish them better in prose, while on stage they’re played by the same person so the line is blurred. I like Alfred, for the most part. His illness, his personality, and his quirks are expanded on further, and make for a few cute moments between him and Alice in the backstory.

And then we get to other characters, and here’s where I need to raise my eyebrow. See, most of the show’s minor characters have been adapted into the novel, and given the names of their show counterparts even if these weren’t stated on-stage. All apart from one. Clarissa, whose Wonderland counterparts are a Canary, a playing card Queen, and one of the mock-Mock Turtles, has been replaced with a girl who is exactly the same in characterisation, but whose name is Mamie. This is notable because Clarissa is the only musical character who has received this treatment, and because Mamie is described as blonde and white, while on stage Clarissa was played by actresses with some Asian heritage. This...is straight up whitewashing. Did Sater not think an upper-class Asian woman would be believable in 1940s London? A quick google search tells me that London’s had a Chinese expatriate community since the 1800s, 20k people of South Asian descent emigrated to Britain from 1800 to 1945...I’m sure something more thorough can come up with more information. It’s incredibly noticeable, especially since Mamie and Clarissa are otherwise identical.

As to the rest...they’re relatively inconsequential, but for the roles they play in Wonderland. This is Alice and Alfred’s story, after all. One bizarre thing is Harold Pudding, who abruptly disappears halfway through the book and is never seen again? Ok. The most fleshed-out of the minor characters is Tabatha, otherwise known as the Cheshire Cat, who helps Alice and urges her to finish the story, helping guide her through her grief and pain. I’m glad to see she comes across as just as much of a massive lesbian as she does in the show! ‘Sister’, my ass. This Cat Is Gay. I don’t think Sater knows that, though.

One final thing - the novel is written in a very stream-of-consciousness, rambling style. (Much like this review.) This can be hard reading at times, especially if you read fast, like I do. I had to go back and reread some passages just to make sure I’d understood what happened - not helped by the surreal nature of the narrative, as befits a Wonderland story.

I’ve done a lot of complaining here. I did enjoy this novel, honest. I’m just not sure about a lot of it? I get the feeling, though, that if you’re much less word-for-word familiar with the show than I am, you’ll have a better time with this book. It’s for you, after all, not me!

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Send “💓” and I’ll tell you how I think a romantic relationship between our muses would go - Dicenne

You might not know this about me, but I’m extremely biased and I totally feel like a romantic relationship between Lyn and Dicenne would be actually really wonderful, great and perfect.

Well, maybe not that last one, but I’m sure you catch my drift.

I think this one would wind up being a fairly long, slow burn. One fraught with minor but conquerable complications. They’re both in fairly transitional periods in their lives so a relationship really does need, to use a baking metaphor, proving time to come out successful.

If they ever started the dating dance, Lyn’s personally not at all interested in rushing into something serious, and she knows Dice has a preference of taking the lead in these sorts of things -- this won’t stop her from asking him to go dancing or surfing. Lots of little fun dates that just give them time together, both friendship and relationship building. I feel like it’s probably pretty important to both of them at this stage in their lives to be good friends with their partner. I can absolutely see them keeping it a little quiet at first, too, for personal privacy’s sake more than anything else.

However keeping it a little quiet at first might be hard because they’re both really into physical affection. It’s a love language they both share, and they already do a little here and there, but this would absolutely get dialed up to 11. Lyn would even let him touch her hair. Wild. Any kind of physical affection Dice chose to give out would just be soaked up and dished right back. It’s been years since anybody really handled her with good touches and she’s super starved for it.

The Other Job is a blip of a complication -- a lot of her current jealousy is because she isn’t getting much affection (and she desperately wants it). Dice would absolutely have to put in some time and effort on occasion to remind and reassure Lyn that it is just work and she’s still the guiding star on his horizon, and that’s something he probably understands or would just do without needing much prompting. This is something that would naturally taper off in time once a really solid foundation is set, especially as it’s a condition of his life that Lyn is fully aware of and has no desire to interfere with if he enjoys it.

Communication would probably be totally fine. Neither of them is really the type to let things just linger unsaid or to be left to too much interpretation. Lyn’s a little more blunt and less tactful than he is, but they don’t dance around each other now and that would be incredibly unlikely to change. They’re both very independent people who will continue to do their own thing the way they like to, and being able to talk frankly without awkwardness is important in reducing misunderstandings. Communication is a major factor in downplaying or negating a lot of Lyn’s worse traits.