#amsterdam 1944

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (6 June 1868 – c. 11 February 1944) - a mixed bag of woodcuts, lithographs and leftovers.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The weather's been wonderful since yesterday /.../ I go to the attic almost every morning to get the stale air out of my lungs /.../ I also looked out of the open window, letting my eyes roam over a large part of Amsterdam, over the rooftops and on to the horizon, a strip of blue so pale it was almost invisible. 'As long as this exist,' I thought, 'this sunshine and this cloudless sky, and as long as I can enjoy it, how can I be sad?' The best remedy for those who are frightened, lonely or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere they can be alone, alone with the sky, nature and God. For then and only then can you feel that everything is as it should be and that God wants people to be happy amid nature's beauty and simplicity."

(Anne in her diary, February 23, 1944)

🌱🌸

Photo: Anne, May 1942.

Shared by Linda 🕎

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

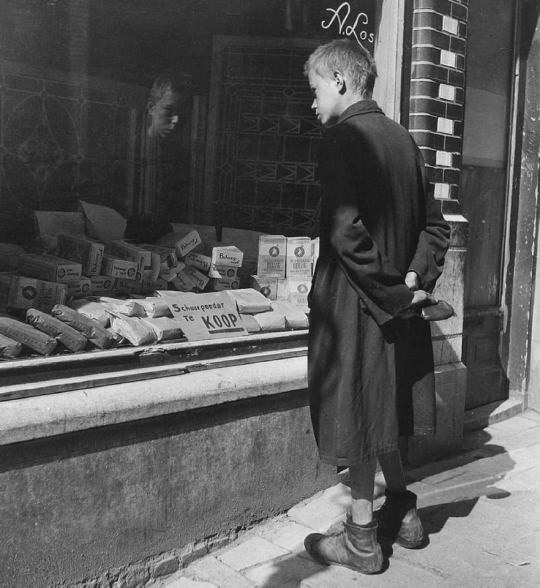

Emmy Andriesse. Child with a saucepan - ''Winter of Hunger'', Amsterdam, 1944-1945.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winter, Amsterdam, 1944/45 - by Emmy Andriesse (1914 -1953), Dutch

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

For nearly all of Jewish history people recognized that antisemitism was a reaction to the Jews and Judaism. But today, Jew-hatred is generally attributed to factors having little to do with Jews and Judaism; rather, its causes are generally held to be economic, political (the use of Jews as scapegoats), ethnic prejudice, and the psychopathology of hate - all of which dejudaize antisemitism.

Among those most committed to these dejudaizing interpretations are secular and non-Jewish Jews committed to the notion that the Jews are a people like all other peoples. Accordingly, they want to believe that antisemitism is but another form of bigotry, and that in the secular world it will die out. These individuals believe that there are no rational reasons for Jew-hatred and/or that antisemitism is a kind of societal sickness. Another reason why many modern Jews believe in these explanations for Jew-hatred, rather than in the one held by Jews for thousands of years, is simply that these explanations are more or less the only ones offered. Modern scholars tend to promote secular and universalist explanations for nearly all human problems, including, of course, antisemitism. In contrast, the traditional Jewish understanding of antisemitism has been the opposite - religious and particularist.

Among modern scholars there are a large number of Jews whose universalist worldviews make them particularly averse to the Jewish explanation of antisemitism. Indeed, they oppose any thesis, about anything, not only antisemitism, which depicts the Jews as distinctive, let alone unique. Accordingly, they have expended great efforts to prove that the Jews are not different from anyone else.

The dejudaization of antisemitism reached its nadir in the 1955 theatrical adaptation of the most famous document of the Holocaust, The Diary of Anne Frank. As an adolescent in Amsterdam, Anne Frank and her family spent more than two years hiding before being captured by the Nazis. During this time Anne Frank kept a diary that was found and published after the war.

Though raised in a secular and assimilated home, Anne came to feel during her years in hiding that there were specific Jewish reasons for the suffering she and other Jews were undergoing. On April 11, 1944, she wrote: "Who has inflicted this upon us? Who has made us Jews different from all other people? Who has allowed us to suffer so terribly up till now? It is God who has made us as we are, but it will be God, too, who will raise us up again. If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left, when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will be held up as an example. Who knows, it might even be our religion from which the world and all peoples learn good, and for that reason and that reason only do we now suffer. We can never become just Netherlanders, or just English, or representatives of any country for that matter. We will always remain Jews, but we want to, too."

But Anne Frank's beliefs that Judaism was at the root of Jew-hatred and that the Jews were different were eliminated in the Broadway version of The Diary of Anne Frank. The authors, Alfred and Frances Hackett, with the advice of the Jewish playwright and political radical Lillian Hellman, simply deleted the above passage, which had been central to Anne's thinking, as well as to writer Meyer Levin's original version of the play. Instead, the Hacketts' put into her mouth words she had never said but that reflected their own universalist views: "We are not the only people that have had to suffer....sometimes one race, sometimes another."

The Hacketts thus presented their dejudaized interpretation of antisemitism in place of the Jewish interpretation offered by Anne Frank, that the Jews are hated precisely because of the Jews' unique role in the world.

- Why the Jews? The Reason for Antisemitism, Dennis Prager and Joseph Telushkin, pages 56-58

#dennis prager#joseph telushkin#rabbi joseph telushkin#why the jews the reason for antisemitism#antisemitism#jumblr#jews and judaism#judaism#anne frank#diary of anne frank

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Interview: Refugees & Reformation in 16th-Century Frankfurt

In the 16th century, German cities and territories welcomed thousands of refugees fleeing the religious persecution sparked by the Protestant Reformation. In Strange Brethren: Refugees, Religious Bonds, and Reformation in Frankfurt, 1554-1608, Professor Maximilian Miguel Scholz explores one major destination for refugees—Frankfurt am Main—and underscores how they inspired new religious bonds, religious animosities, and religious institutions. In this interview, James Blake Wiener speaks to him about his title and the unique social climate that pervaded the Hessian city.

Cover: Strange Brethren: Refugees, Religious Bonds, and Reformation in Frankfurt, 1554-1608

Association of University Presses (Copyright, fair use)

JBW: Professor Scholz, thank you so much for speaking with me on behalf of World History Encyclopedia (WHE). When many think of Protestant refugees in the Early Modern Era, their minds usually turn to the plight of Huguenots or Anabaptists. Many of them found refuge in cities like London, Amsterdam, Geneva, and Hamburg. What was it that first attracted you to the history of 16th-century Frankfurt am Main? Moreover, what differentiated Frankfurt am Main from other Protestant cities within the Holy Roman Empire?

MS: Frankfurt hosted thousands of refugees in the 16th century. It still does today! But the city is often overlooked because the documents pertaining to its 16th-century experience of refugee accommodation were destroyed by the U.S. and British militaries in 1944. I wanted to shine new light on Frankfurt’s centrality in the story of Protestant refugees. Frankfurt lay at the center of Germany, which it still does today. It was also the symbolic capital of Germany, where the Holy Roman Emperors were elected and crowned. (After the Second World War, there was a push to make Frankfurt the capital of Germany once more.) Frankfurt was the transportation hub of Germany then as it still is now. If we want to understand how refugees impacted German society, Frankfurt is the ideal place to start. Beyond its prominence in Germany, Frankfurt was different from other German cities because its Reformation had followed the lead of Martin Bucer rather than Martin Luther (though of course Frankfurters loved Luther too). Bucer had advocated for reforms that fell somewhere between the later Calvinist and Lutheran camps.

Religions in Europe in the 16th Century

Simeon Netchev (CC BY-NC-ND)

JBW: Repeated bombing by British and American air forces destroyed many of Frankfurt’s churches and archives in 1944. If I’m not mistaken, Frankfurt was formerly the largest half-timbered city center in Germany too, so a great deal was lost in a very short period of time. Could you comment on the tremendous hurdles you and fellow scholars face in researching Frankfurt am Main’s Early Modern history as a result?

MS: Yes, Frankfurt’s archive suffered grievously. The archive’s director believed the Nazi fantasy that Germany was impervious to assault, so he did not protect the archive’s treasures by moving them underground. Thus, the bombings of 1944 destroyed about 70% of the archive’s holdings, including the Acta Ecclesiastica, which documented the birth of Protestantism in Frankfurt. Historians interested in the religious changes of the 16th century need to use either non-civic sources (like the records of the Dutch and French Reformed communities in Frankfurt, which were not housed at the archive) or reproductions of the original sources, which can be found in the appendices of many pre-WWII histories of Frankfurt. My book relied on documents from an imperial court case in 1720. The Dutch and French Reformed (i.e. Calvinists) sued the city of Frankfurt at the imperial supreme court, and both the sides collected and printed documents from the Reformation that they believed helped their case.

Reformation Wall

Henri Bouchard and Paul Landowski (CC BY-SA)

JBW: Frankfurt am Main received French-, Dutch-, and English-speaking Protestant refugees throughout the 1550s, 1560s, and 1570s. Many of the earliest refugees were the so-called “Marian exiles.” Who were these early exiles, what brought them to Frankfurt am Main, and how long did they stay in Hesse?

MS: These exiles were the earliest Protestants (though they did not call themselves that), and they were fleeing Catholic rulers. The point of contention was the Catholic mass. The refugees in my book refused to attend the Catholic mass, because they rejected the idea that a priest could perform a ritual on an altar that would summon forth the actual body of Jesus. These people considered this idolatrous and believed the mass should be replaced by a simplified eucharist, which would focus on the Bible and memorialize the Last Supper. The Catholic authorities began to violently persecute those who did not attend the mass, and these early Protestants faced a choice: be martyred at home or flee abroad. Thousands fled to Frankfurt, which as an independent city (it was not then part of Hesse) could rule its own religious affairs, to an extent. In the case of English Protestants fleeing the Catholic Queen Mary I of England (the Marian exiles), they returned when she died and was replaced by the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I of England. Thus, they were in Frankfurt for just five years. Other refugees from the Low Countries settled in Frankfurt and have descendants who still live in the city.

JBW: Professor Scholz, how did Lutheran elites and ordinary citizens in Frankfurt am Main first react to the presence of Calvinist refugees? What subsequently changed over the next few decades?

MS: At first, they welcomed them. They considered these newcomers brethren, who had suffered under the cruel rule of tyrannical Catholics like Charles V and Mary Tudor. But it proved difficult to live alongside these newcomers, many of whom were richer than the citizens of Frankfurt. When Frankfurters witnessed the church services of the refugees, they realized that these people practiced Christianity differently. Frankfurters were scandalized that the refugees took the bread of the eucharist into their own hands. And they were further disgusted that the refugees brought their screaming children with them into the churches. Frankfurt’s pastors were the first to turn on the newcomers, demanding that they conform to Frankfurt’s ritualistic practices or leave the city. The pastors whipped up a popular hatred of the refugees.

Martin Bucer

Unknown Artist (Public Domain)

JBW: I think some readers who are relatively unfamiliar with the history of the Protestant Reformation may be surprised to learn about the high degree of confessional strife and rivalry between Calvinists and Lutherans. Could you thus explain to us how officials in Frankfurt am Main ultimately circumscribed Calvinist worship and freedom?

MS: The refugees and native Frankfurters split into two religious camps that we now call Calvinist (they called themselves Reformed) and Lutheran (they called themselves Evangelical), and this division became violent at times. For Americans, living in a country that has separated religion from government, it can be hard to imagine how little differences in worship or belief could have resulted in legal trouble, expulsion, or worse. Once Frankfurt’s leaders concluded that the refugees were “Calvinists” they banned them from applying for citizenship and closed their churches. Periodic riots against the refugee community resulted in deaths and the burning down of a small chapel the Reformed had built outside the city wall.

JBW: How would you characterize the Calvinist refugees’ religious and civic impact upon Frankfurt am Main? Can we still detect their legacy in the city today?

MS: They enriched Frankfurt enormously by bringing in goods and industry from the Low Countries. The Low Countries were the most industrially advanced part of Europe, and the Protestants who fled places like Antwerp took their industrial know-how with them into German cities like Frankfurt. And when Frankfurt began to harass these newcomers, they settled in little towns outside of Frankfurt, towns which became (and still are) hubs of industry, like Hanau and Offenbach.

Frankfurt on the Main, c. 1617

Matthäus Merian (Public Domain)

JBW: What lessons can we draw from the experiences of the Calvinist refugees in Frankfurt am Main that could perhaps be applied to our own era?

MS: Welcoming, resettling, and integrating refugees into a city can be very difficult and may provoke problems that persist for generations. But it is not impossible. The internal cultural organizations of a refugee community (like the Calvinist consistory in 16th-century Frankfurt) can help facilitate financial support for refugees, management of their affairs, and integration into the host city. We need to confront the reality that it may take generations for refugees and their descendants to embrace (and be embraced by) host societies.

JBW: Professor Scholz, thanks so much for your time and consideration! I wish you many happy adventures in writing and research.

MS: Thank you so much for your questions.

Professor Maximilian Miguel Scholz

Association of University Presses (Copyright, fair use)

Biographical précis:

Professor Maximilian Miguel Scholz specializes in the social and religious history of early modern Europe and teaches at Florida State University. His first book, Strange Brethren: Refugees, Religious Bonds, and Reformation in Frankfurt, 1554-1608 (University of Virginia Press, 2022) explores the fate and impact of Reformation refugees by looking at one center of European refugee life, the city of Frankfurt am Main. His second book, tentatively titled The Great Refugee Realignment: How Forced Migrants Transformed Government in Northern Europe, 1550-1750 uses refugee treaties collected from archives across Europe to illuminate the ways refugees transformed governments, stimulating the growth of centralized bureaucracies and contributing new ideas about political membership and new systems for managing religious, ethnic, and migration-status diversity.

Continue reading...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jaap Bakema (1914-81) without doubt was one of the most important and most prominent architects of postwar Netherlands whose work in collaboration with Jo van den Broek was received well beyond Dutch borders. At the same time Bakema not only through his architecture but also as one of the editors of the „Forum“ magazine and as professor at TH Delft influenced both the architectural discourse and a young generation of architects.

Last year Annette Jansen published her biography „Totale ruimte. Jaap Bakema 1914-1981 - In de voetsporen van een bouwkunstenaar“ with Querido Fosfor, a book that takes a closer look at the person behind the architecture. Bakema was born in Groningen and grew up in the first Tuindorp of the Netherlands in humble circumstances. At the age of 16 he entered the Hogere Technische School in Groningen in order to study civil, road and hydraulic engineering. During his time at the HTS Bakema also met his future wife who had very different, bourgeoise family background that had a great impact on the young Bakema. Especially his future father in law greatly influenced his intellectual formation with regard to architecture, music and politics.

After a brief stint in the office of Willem Reitsma and his military service Bakema in 1937 began his Hoger Bouwkundig Onderricht in Amsterdam, studies in architecture he completed cum laude under Mart Stam in 1941. Already in 1939 Bakema was offered a position in the Rotterdam office of Willem van Tijen and Hugh Maaskant, a chance he couldn’t let pass but one that was interrupted by the German occupation: in 1943 the Germans passed a law that obligated all Dutch men between 18 and 45 to do work in Germany. In order to avoid fatigue duty Bakema and his friend Jan Rietveld sought to escape to England but were caught in France and deported to a camp in March 1943. Miraculously and after passing through different camps the two were able to escape in Fall 1944 and returned alive to the Netherlands. For the first time Annette Jansen had access to Bakema's internment diaries which are reproduced in the book.

With the end of WWII Bakema got involved with the reconstruction of Rotterdam and in 1948 joined the office of Johannes Brinkman and Jo van den Broek. At this point the author starts to follow Bakema’s development by means of his most important buildings, e.g. the Nagele village, ’t Hool in Eindhoven or the Terneuzen Town Hall. For each project Jansen also interviewed former collaborators as well as Bakema’s children, a profitable approach as it allows for multiple perspectives on his architecture and the ideas behind it.

Annette Jansen’s book isn’t the usual architect’s biography but a well-written, elucidating exploration of an architect’s personality and ideals and how they show in his built work. A great read!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nazi Gestapo captured 15-year-old Jewish diarist Anne Frank and her family #OnThisDay in 1944. The Franks were in the Amsterdam warehouse they had sheltered in for two years.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in history

Anne Frank writes her last diary entry

August 1 1944

Anne Frank, the young Jewish girl hiding out in Nazi-occupied Holland whose diary came to serve as a symbol of the Holocaust, writes her final entry three days before she and her family are arrested and placed in concentration camps.

Frank, 15 at the time, received the diary on her 13th birthday, writing in it faithfully during the two years she and seven others (including her parents, Otto and Edith, and sister, Margot; her father’s business associate Hermann van Pels, his wife, Auguste, and son, Peter; and Fritz Pfeffer, the dentist of Otto Frank’s secretary) lived in a secret annex behind her father’s business in Amsterdam during World War II.

In her final entry, Frank wrote of how others perceive her, describing herself as “a bundle of contradictions.” She wrote: “As I’ve told you many times, I’m split in two. One side contains my exuberant cheerfulness, my flippancy, my joy in life and, above all, my ability to appreciate the lighter side of things. By that I mean not finding anything wrong with flirtations, a kiss, an embrace, an off-color joke. This side of me is usually lying in wait to ambush the other one, which is much purer, deeper and finer. ….”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro-Palestinians: We're not antisemitic!

Also Pro-Palestinians:

#anne frank#antisemitism#free palestine#free gaza#even in death anne is still victimized by antisemites#cant wait to block all the antisemites that are gonna react to this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

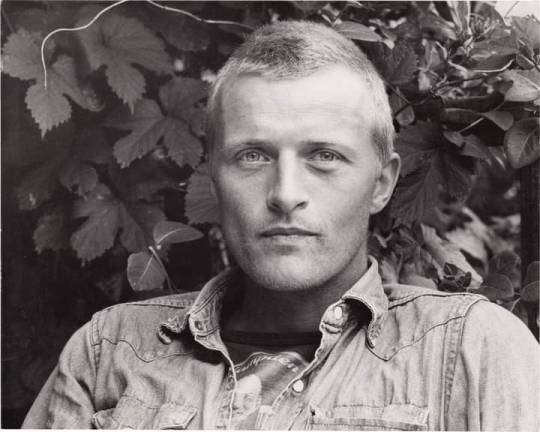

In MEMORY of RUTGER HAUER on his BIRTHDAY - (January 23, 1944 - July 19, 2019)

Career years: 1969 - his death

Born Rutger Oelsen Hauer, Dutch actor. In 1999, he was named by the Dutch public as the Best Dutch Actor of the Century.

Hauer's career began in 1969 with the title role in the Dutch television series Floris and surged with his leading role in Turkish Delight (1973), which in 1999 was named the Best Dutch Film of the Century. After gaining international recognition with Soldier of Orange (1977) and Spetters (1980), he moved into American films such as Nighthawks (1981) and Blade Runner (1982), starring in the latter as self-aware replicant Roy Batty. His performance in Blade Runner led to roles in The Osterman Weekend (1983), Ladyhawke (1985), The Hitcher (1986), The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988), and Blind Fury (1989), among other films.

From the 1990s on, Hauer moved into low-budget films, and supporting roles in major films like Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992), Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), Batman Begins (2005), Sin City (2005), and The Rite (2011). Hauer also became well known for his work in commercials. Towards the end of his career, he made a return to Dutch cinema, and won the 2012 Rembrandt Award for Best Actor in recognition of his lead role in The Heineken Kidnapping (2011).

Hauer supported environmentalist causes and was a member of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. He also founded the Rutger Hauer Starfish Association, an AIDS awareness organization. He was made a knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion in 2013.

Early life -

Hauer was born in Breukelen, in the Province of Utrecht, while the Netherlands was under German occupation during World War II. He stated in a 1981 interview, "I was born in the middle of the war, and I think for that reason I have deep roots in pacifism. Violence frightens me." His parents were Teunke (née Mellema) and Arend Hauer, both actors who operated an acting school in nearby Amsterdam. He had three sisters. According to Hauer, his parents were more interested in their art than their children. He did not have a close relationship with his father, and writer Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema later became a father figure to Hauer after they met during the filming of Soldier of Orange.

Hauer attended a Rudolf Steiner school, as his parents wanted him to develop his creativity. At the age of 15, he left school to join the Dutch merchant navy. He spent a year travelling the world aboard a freighter, but was unable to become a captain due to his colourblindness. Returning home, he worked odd jobs while finishing his high school diploma at night. He then entered the Academy for Theater and Dance in Amsterdam for acting classes, but soon dropped out to join the Royal Netherlands Army. He received training as a combat medic, but left the service after a few months as he opposed the use of deadly weapons. He subsequently returned to acting school and graduated in 1967.

Career:

Early works -

Hauer had his first acting role at the age of 11, as Eurysakes in the play Ajax. After graduating from the Academy for Theater and Dance, he became a stage actor with the Toneelgroep Noorder Compagnie. Hauer made his screen debut in 1969 when Paul Verhoeven cast him in the lead role of the television series Floris, a Dutch medieval action drama. The role made him famous in his native country, and Hauer reprised his role for the 1975 German remake Floris von Rosemund.

Hauer's career changed course when Verhoeven cast him in Turkish Delight (1973), which received an Oscar nomination for best foreign-language film. The film found box office favour abroad and at home, and Hauer looked to appear in more international films. Within two years, Hauer made his English-language debut in the British film The Wilby Conspiracy (1975). Set in South Africa, the film was an action-drama with a focus on apartheid. Hauer's supporting role, however, was barely noticed in Hollywood, and he returned to Dutch films for several years. During this period, he made Katie Tippel (1975) and worked again with Verhoeven on Soldier of Orange (1977), and Spetters (1980). These two films paired Hauer with fellow Dutch actor Jeroen Krabbé. At the 1981 Netherlands Film Festival, Hauer received the Golden Calf for Best Actor for his overall body of work.

American breakthrough -

Hauer made his American debut in the Sylvester Stallone film Nighthawks (1981) as a psychopathic and cold-blooded terrorist named Wulfgar. With his sights set on a long-term career in Hollywood, Hauer worked with an accent coach in the early 1980s to develop a convincing American accent. Unafraid of controversial roles, he portrayed Albert Speer in the 1982 American Broadcasting Company production Inside the Third Reich. The same year, Hauer appeared in arguably his most famous and acclaimed role as the eccentric and violent but sympathetic antihero Roy Batty in Ridley Scott's 1982 science fiction thriller Blade Runner, in which he delivered the famous tears in rain monologue. Hauer composed parts of the monologue the evening prior to filming, "cutting away swathes of the original script before adding the speech’s poignant final line". He went on to play the adventurer courting Theresa Russell in Eureka (1983), investigative reporter opposite John Hurt in The Osterman Weekend (1983), hardened mercenary Martin in Flesh & Blood (1985), and knight paired with Michelle Pfeiffer in Ladyhawke (1985).

He appeared in The Hitcher (1986), in which he played a mysterious hitchhiker tormenting a lone motorist and murdering anyone in his way. He received the 1987 Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in the television film Escape from Sobibor. At the height of Hauer's fame, he was set to be cast as RoboCop (1987), but Verhoeven, the film's director, considered his frame as too large to move comfortably in the character's suit. Also in 1987, Hauer starred as Nick Randall in Wanted: Dead or Alive as the descendant of the character played by Steve McQueen in the television series of the same name.

In 1988, he played a homeless man in Ermanno Olmi's The Legend of the Holy Drinker. This performance won Hauer the Best Actor award at the 1989 Seattle International Film Festival. Hauer was chosen to portray a blind martial artist superhero in Phillip Noyce's action film Blind Fury (1989). He initially struggled with the implausibility of the character, but learned to "unfocus my eyes, to react to smells and sounds" after meeting with blind judo practitioner Lynn Manning during his research for the role. Hauer returned to science fiction in 1989 with The Blood of Heroes, in which he played a gladiator in a post-apocalyptic world.

Commercials and later roles -

By the 1990s, Hauer was well known for his humorous Guinness commercials as well as his screen roles, which had increasingly involved low-budget films, such as Split Second (1992); The Beans of Egypt, Maine (1994); Omega Doom (1996) and New World Disorder (1999). In 1992, he appeared in the horror-comedy film Buffy the Vampire Slayer as the main antagonist vampire Lothos. He also appeared in the Kylie Minogue music video "On a Night Like This" (2000). During this time, Hauer acted in several British, Canadian and American television productions, including Amelia Earhart: The Final Flight (1994) as Earhart's navigator Fred Noonan, Fatherland (1994), Hostile Waters (1997), The Call of the Wild: Dog of the Yukon (1997), Merlin (1998), The 10th Kingdom (2000), Smallville (2003), Alias (2003), and Salem's Lot (2004).

Hauer played an assassin in Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2003), a villainous cardinal with influential power in Sin City (2005) and a devious corporate executive running Wayne Enterprises in Batman Begins (2005). Also in 2005, he played the title role in Patrick Lussier's film Dracula III: Legacy. Seven years later, he portrayed the vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing in Dario Argento's Dracula 3D. Hauer hosted the British reality television documentary Shock Treatment in 2005, and featured in Goal II: Living the Dream (2007) as Real Madrid coach Rudi Van der Merwe. He also recorded voice-overs for the British advertising campaign for the Danish butter brand Lurpak.

In 2008, Hauer received the Golden Calf Culture Prize for his contributions to Dutch cinema. The award recognised his work as an actor as well as his efforts to aid the development of young filmmakers and actors, through initiatives such as the Rutger Hauer Film Factory. In 2009, his role in avant-garde filmmaker Cyrus Frisch's Dazzle received positive reviews; it was described in Dutch press as "the most relevant Dutch film of the year". The same year, Hauer starred in the title role of Barbarossa, an Italian film directed by Renzo Martinelli. In April 2010, he was cast in the live action adaptation of the short and fictitious Grindhouse trailer Hobo with a Shotgun (2011). Hauer played Freddie Heineken in The Heineken Kidnapping (2011), for which he received the 2012 Rembrandt Award for Best Actor. Also in 2011, Hauer appeared in the supernatural horror film The Rite as an undertaker named Istvan, the protagonist's father.

From 2013 to 2014, Hauer featured as Niall Brigant in HBO's True Blood. In 2015, he starred as Ravn in The Last Kingdom and as Kingsley in Galavant. In 2016, he joined the film jury for ShortCutz Amsterdam, an annual film festival promoting short films in Amsterdam. Hauer voiced the role of Daniel Lazarski in the 2017 video game Observer, set in post-apocalyptic Poland. Lazarski is a member of a special elite police unit that can hack into minds and interact with memories within. Hauer also provided the voice of Xehanort in the 2019 video game Kingdom Hearts III, replacing the late Leonard Nimoy and was himself replaced by Christopher Lloyd following his death.

Personal life -

Hauer was married twice:

Hauer and his first wife, Heidi Merz, produced Hauer’s only child, Aysha Hauer (born 1966). An actress, she gave birth to Hauer's grandson in 1987.

Hauer was with his second wife, Ineke ten Cate, from 1968, and they married in a private ceremony on 22 November 1985. Cate was the daughter of Laurens ten Cate, the editor-in-chief of the Friesland-based newspaper Leeuwarder Courant.

Although born in Utrecht, Hauer had strong links to Friesland. He once stated in an interview with the Algemeen Dagblad that he "needed to feel the Frisian clay under his feet".

Hauer was an environmentalist. He supported the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and was a member of its board of advisors. He also established an AIDS awareness organization called the Rutger Hauer Starfish Association.

In April 2007, he published his autobiography, All Those Moments: Stories of Heroes, Villains, Replicants, and Blade Runners (co-written with Patrick Quinlan), in which he discussed many of his acting roles. Proceeds from the book go to the Rutger Hauer Starfish Association.

Death -

Hauer died at his home in Beetsterzwaag, following a short illness. He was 75 years old. A private funeral service was held on 24 July. On 23 January 2020, which would have been Hauer's 76th birthday, a ceremony was held in Beetsterzwaag in his honour. Attendees included Sharon Stone, Miranda Richardson, Diederik van Rooijen, and Prince Pieter-Christiaan of Orange-Nassau, van Vollenhoven.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The weather's been wonderful since yesterday /.../ I go to the attic almost every morning to get the stale air out of my lungs /.../ I also looked out of the open window, letting my eyes roam over a large part of Amsterdam, over the rooftops and on to the horizon, a strip of blue so pale it was almost invisible. 'As long as this exist,' I thought, 'this sunshine and this cloudless sky, and as long as I can enjoy it, how can I be sad?' The best remedy for those who are frightened, lonely or unhappy is to go outside, somewhere they can be alone, alone with the sky, nature and God. For then and only then can you feel that everything is as it should be and that God wants people to be happy amid nature's beauty and simplicity."

(Anne in her diary, February 23, 1944)

🌱🌸

Photo: Anne, May 1942.

Shared by Linda 🕎

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Day of Days: Eighty Years After

It was a brisk summer night, almost like any other June night in England.

The terror of the Blitz was long over. Four years ago, the Battle of Britain long had been won. Two years ago in the Pacific the Americans had shocked the world with impossible victories at Midway and Guadalcanal. A year ago, the last German forces had surrendered in North Africa, and the Communists of the Soviet Union had done the impossible and stopped the German war machine in its tracks at the gates of Stalingrad and Moscow before, finally, turning the tide at Kursk. A month early the British Army in India had stopped the Imperial Japanese Army in its tracks at Kohima Ridge, and for the first time in three years the Japanese were on the run. Just a day before, the American Fifth Army had liberated Rome, freeing the "Eternal City" from fascism after twenty years.

They were winning - just. The war was still going on, ever-present in their minds, but they could sleep soundly under a quiet, friendly sky.

But in the dark, in army camps and airfields and naval bases and offices across the southwest of England, the scene was very different. Men whispered to each other, prayers and jokes, trying to lighten the tension in the air, so thick they could cut it with a knife. John Ford - the famed Hollywood director turned Navy Field Photographic unit captain - supposedly told his wife he was going off for a little local skirmish. And in his private office, Dwight D. Eisenhower - Commander, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force - typed the resignation he hoped he'd never have to give. If the unthinkable happened, if this gamble failed...they might never get another chance.

All at once, all across the southwest of England, just before midnight, the quiet was shattered by the roar of thousands upon thousands of piston engines, and thousands of men, some barely out of high school, clambered aboard planes and landing craft for a journey into the dark.

Eisenhower penned a short note, and ensured that a copy was given to every single one of the men under his command. It read, very simply:

"You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world."

It was June 6th, 1944, and after three years of begging by Josef Stalin, and a year of intense planning, brutal training, unparalleled deception, and massive buildup, the time had come to do the impossible.

The Allies were going to break the Atlantic Wall, or die trying.

It was a herculean task. The Germans had spent four years preparing for just this day, filling every beach from Cherbourg to Amsterdam with every kind of mine imaginable, dotting Czech hedgehogs and wooden posts tipped with high explosives along the shallow coastlines, and building bunkers with encased machine guns and artillery, pre-sighting mortars and artillery, digging trenches and building tens of thousands of pillboxes, and digging enough anti-aircraft positions to turn night into day. In command was Erwin Rommel, the famed "Desert Fox", a veteran of the brutal World War I Italian front, and one of the best tank commanders in the world who had fought across France and North Africa. Under his command were almost half a million German troops, including battle hardened veterans of France, Africa, and Russia.

Standing against them, over a thousand planes and gliders carrying over 23,000 paratroopers from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. Behind them, thousands of fighters and bombers and almost seven thousand landing craft and ships carrying more than 160,000 men from thirteen nations.

The Day of Days began just after midnight.

At 00:48 on June 6th, 1944, the men of the 101st Airborne became the first of to make a terrifying jump into the dark.

It was the beginning of the single largest amphibious invasion ever attempted. Six hours after the paratroopers took the plunge, at 06:30 local time, the first men stumbled onto shore, and into the jaws of death.

Almost immediately, the entire plan fell apart. Fog, cloud cover, a lack of navigators, and brutal anti-aircraft fire forced many pilots to signal the paratroopers to drop outside their assigned zones, mixing units and men and causing absolute chaos on the ground. The weather in the channel was not much better: high seas swamped many of the landing craft and amphibious tanks, and strong currents pushed entire regiments out of their landing zones.

When the men finally made it to the beach, they faced a desperate run across the dreaded shingle: a nearly half-mile expanse of open sand and rock, with no protection at all from the waiting German defenders. Their fire support - the naval vessels waiting offshore, bristling with guns of all calibers - was of little help; the captains refused to close any farther than the extreme ranges for fear of counter fire. And the bad weather in the skies above prevented pilots from accurate close air support.

Over ten thousand men from both sides would have their lives ripped apart on beaches in just that first day.

On Omaha Beach alone, almost two thousand men were killed. Some didn't even get a chance to face the enemy - instead, they simply drowned, their heavy equipment weighing them down into the cold waters of the North Atlantic. The beaches themselves, its said, turned red with blood as men were killed by the dozen. At Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches, the Canadians and British managed to make it off the beach, only to be forced into fortified towns, where they endured the brutality and chaos of house-to-house urban warfare. At Pointe du Hoc, between Omaha and Utah Beach, the U.S. 2nd Ranger Battalion were forced to scale a one hundred foot cliff under withering enemy fire, only to become totally cut off. When they were finally relieved after two days, only 65 of the original 200 men were left standing, and they were forced to use captured German weapons as theirs ran out of ammunition, resulting in some of their number being killed due to friendly fire.

The paratroopers faired even worse - of the more than 20,000 American paratroopers and aircrew who made the desperate flight across the Channel, it's estimated that more than twelve thousand were killed.

The carnage was unlike anything anyone in the Allied forces had seen before, unlike Operation Torch or El Alamein in North Africa, unlike the Miracle of Dunkirk or the Battle of Britain, unlike Guadalcanal and New Guinea, unlike Salerno, Anzio, and Sicily.

For this untold sacrifice, this bloody hell that almost two hundred thousand men endured, they had only managed to capture a few square miles, only two of five beaches were connected, and they had failed to capture a single major city or port. The Allies failed to achieve even one of their major objectives - save one.

After five years of war, the Allies had a foothold.

The mother of all Hail Mary's had worked.

By the end of D-Day, almost 160,000 men had crossed the Channel into Fortress Europe.

On D+6, the beaches were finally connected.

On D+7, the city of Carentan was freed by the 101st Airborne, the first major French town to be liberated.

By D+20, the port city of Cherbourg was taken, and the Cotentin Peninsula was free after four long years.

On D+50, the city of Caen was freed, and the objectives of D-Day had finally been completed. By this time, more than 1.5 million men from 15 nations had landed in Europe.

On D+70, the Allies landed on the beaches of Côte d'Azur, and in only four weeks broke the southern German front line, and liberated the entire south of France.

On D+76, the Falaise Pocket collapsed, and the Battle of Normandy was finally declared over in a resounding Allied victory.

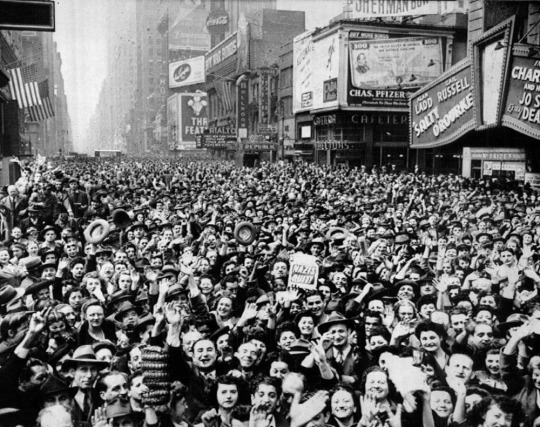

Then, at long last, on D+80, General der Infanterie Dietrich von Cholitz, at 3:30 PM local time, surrended the city of Paris to General Phillipe Leclerc. After four years of occupation, the first Allied capital was free. The footage of that day has been called some of the most thrilling and ecstatic footage in history.

The march continued, and on D+89, the Welsh Guards marched into the Belgian capital of Brussels.

But the war was far from over - on D+193, the Wehrmacht launched Operation Nordwind; the Battle of the Bulge had begun. It would be Germany's last offensive, at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives.

On D+274, the Allies crossed the Rhine, and liberated the Netherlands, and then finally entered Germany.

On D+303, the U.S. 4th Armored Division stumbled upon a scene of unimaginable cruelty: it was a camp named Ohrdruf, part of the Buchenwald complex, the first concentration camp to be liberated by the United States. Allied intelligence services had long suspected what was going on, that their were camps across Europe for Hitler's "undesirables", and the Allies had even signed a declaration making public and condemning the killing of Jews in Poland, but no one was prepared to see the true scale of the atrocities. Eisenhower demanded that every single piece of the camp be photographed, videotaped, and documented, that everyone possible be brought to see it to impress upon them the reality of what the Germans had done. Hollywood director George Stevens was given the task of making movies describing the horrors of the Holocaust, movies that were later shown to the world at the Nuremberg Trials. The movies were said to be the moment that changed the course of the Nuremberg Trials.

Then, on April 30th, 1945 - three-hundred and twenty eight days after the 'Longest Day' - Adolf Hitler, the man who had been the head of so much destruction, who had started the most destructive war in human history and presided over the worst genocide mankind has ever perpetrated, commits suicide in a bunker in Berlin.

Three days later, on May 2nd, 1945, the surrender of German Army Group C goes into effect, and the Gothic Line that had long since stymied the Allied advance in Italy finally collapses.

And on D+336, eleven months after landing on the beaches of France, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel would sign the German Instrument of Surrender, and the German Wehrmacht laid down its arms.

The Reich that Adolf Hitler had once boasted would last for a thousand years had fallen after just twelve.

The War in Europe was over.

Eleven months after he wrote it, the promise Eisenhower made to his men - the destruction of the German Army, the end of Nazi tyranny in Europe - had finally come true.

It had been five and a half long, blood-soaked years since the war in Europe began, but at long last, Europe was free. It would takes years, even decades, to rebuild from the destruction, but finally, there was a tomorrow to live for.

Eighty years on, we still grapple with their sacrifice, and the choices they made afterwards in the world they built. But because of them, we were given a tomorrow to argue in - and a tomorrow to live for. All because thousands from across the world stepped onto a small, windswept beach, and seared the name of Normandy into history.

#history#ww2#d day#normandy#tw death mention#will anyone on tumblr care about this? doubtful#but i wrote it anyways because it's been 80 years and that has decided to occupy all of my writing brain cells

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is Miep Gies. She was the last remaining survivor who helped in hiding the Frank family during WWII. Miep was born to a Catholic family in Vienna on February 15, 1909. Following WWI, conditions in Austria worsened and food supplies were sparse, Miep’s parents sent her to the Netherlands for a healthier life with a foster family.

In 1933, Miep started working as a secretary for Otto Frank. The two worked together for several years as things in Amsterdam became increasingly dangerous for Jews. One day, in July 1942, Otto sat down with Miep to share his plans of hiding in a Secret Annex in Otto’s office building and asked if she was able to help. Without any hesitation, Miep immediately agreed. She, together with her husband Jan, put their lives at risk by providing food, news and other supplies. The Franks were joined in the attic by another Jewish family and Miep’s dentist. In August 1944, all 8 individuals were found by the Gestapo after 25 months in hiding. Miep was working in the building at the time and immediately ran to save Anne’s notebooks and put in her desk drawer for safekeeping.

Following their deportation to concentration camps, Otto was the only one to survive. In January 1945, he returned to Amsterdam and reunited with Miep. It was then that she shared Anne’s diary. After the war, Otto lived with Miep’s family and organized Anne’s notes into a book which was first published in the Netherlands in 1947. “Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl” went on to sell tens of millions of copies worldwide.

In 1987, Miep published a memoir, ‘Anne Frank Remembered’. “I am not a hero. I stand at the end of the long, long line of good Dutch people who did what I did and more–much more–during those dark and terrible times years ago, but always like yesterday in the heart of those of us who bear witness. Never a day goes by that I do not think of what happened then.” In January 2010, Miep died in the Netherlands at 100 years old.

Humans of Judaism

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dutch children with bread and soup during the Hunger Winter, Amsterdam, 1944 - by Cas Oorthuys (1908 - 1975), Dutch

132 notes

·

View notes