#also like the man's a biographer and a playwright

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Did y'all know that Jim Beaver is like an expert on George Reeves?

#we love a hyperfixation#jim what#like the second man to ever play superman george reeves?#btw how i got here is from judging which celebrities from the midwest would watch tornados from their porch#and then which superman/clark kent actors would do the same#shout out george reeves and brandon routh for being good ol iowa boys#also like the man's a biographer and a playwright#i didnt know any of this and im delighted#jim beaver#spn

1 note

·

View note

Photo

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (1564-1616) was an English poet, playwright, and actor who flourished during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean eras. Known as the 'Bard of Avon,' he wrote 38 plays, 154 sonnets, and three longer narrative poems. His plays, often written in blank verse and composed in iambic pentameter, were incredibly popular in their day and continue to be performed around the world; they include comedies such as A Midsummer Night's Dream and Twelfth Night, tragedies like Hamlet and Macbeth, histories such as Henry V, and tragicomedies like The Tempest. Arguably the most influential dramatist of all time, Shakespeare's legacy has only grown throughout the centuries. In the words of fellow playwright Ben Jonson, Shakespeare was "not of an age, but for all time."

Early Life & Marriage

Little is known for certain about the life of William Shakespeare. As a commoner, his life did not merit the same attention as that of a nobleman or other public figure. Even after his rise to prominence, contemporary audiences were much more interested in his work than his personal life, and no attempt to write his biography was made until decades after his death. As a result, most of his biographical details have been lost to history, leaving behind only a rough outline of the man he might have been. This outline, however, can be colored in with public documents from the era; indeed, the Bard of Avon lives on in the yellowed, bureaucratic pages of tax records, payment transactions, lawsuits, and wills. From these records, scholars have been able to track Shakespeare's activities, allowing them to piece together the story of his life. This information is supplemented by comments made by other playwrights, like Robert Greene (1558-1592) and Ben Jonson (1572-1637), who occasionally alluded to Shakespeare in their works, conversations, and literary critiques. Only with these tiny fragments, as well as a careful scholarly analysis of Shakespeare's works and the time in which he lived, can we hope to get a fuller picture of one of the most influential writers to ever live.

What is beyond dispute is that Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, a "handsome small market town" of about 1,400 residents in Warwickshire, England (quoted in Bevington, xlviii). His father, John Shakespeare (circa 1531-1601), was a successful glover and leatherworker who had moved to Stratford sometime before 1552. His mother, Mary Arden (circa 1537-1608), was the daughter of a wealthy gentleman who had leased land to the Shakespeare family in nearby Snitterfield; having grown up on the Arden property, it is likely that John Shakespeare had known Mary Arden all his life. The match greatly improved John's social status, helping him pursue various public offices in Stratford, including alderman and even bailiff (a position roughly corresponding to mayor). As his prosperity grew, John acquired several houses, including the one on Henley Street that has been traditionally regarded as William's birthplace. The third of eight children born to John and Mary Shakespeare (and the eldest to survive childhood), William Shakespeare was baptized in Stratford on 26 April 1564; though his exact birthdate was unrecorded, it has been traditionally celebrated on 23 April.

Most scholars agree that Shakespeare received a grammar school education, likely at King's New School at Stratford, in which he would have enrolled around 1571 at the age of 7. In this one-room schoolhouse, Shakespeare would have undergone a rigorous curriculum centering around Latin studies; the standard text was Grammatica Latina by William Lyly (grandfather of the poet John Lyly), but Shakespeare would have also read from Aesop's Fables and studied the works of ancient Roman literature, such as poems by Plautus and Ovid, each of whom would greatly influence his own plays. In 1577, Shakespeare's family fell on hard times for reasons that are still unknown – John Shakespeare stopped showing up to town council meetings, mortgaged his wife's property, and became involved in a lawsuit over his unlicensed dealings in wool. Amidst these financial difficulties (though not necessarily because of them), Shakespeare stayed in Stratford and never went to university. Instead, he got married. A bishop's license issued on 27 November 1582 records a marriage between William Shakespeare and Anne 'Whately'. This was a misprint, however, as the bond of sureties issued the next day corrected her name to Anne Hathaway.

Throughout the centuries, Shakespeare's marriage has been the topic of much speculation. There was a significant age difference between the couple – Anne was 26 and William only 18 – leading some scholars to believe that Shakespeare was forced into marriage by the Hathaway family after accidentally getting her pregnant. While this seems to be supported by the fact that Anne gave birth only six months after their marriage, there is no evidence that Shakespeare was strong-armed into what would today be called a 'shotgun wedding'. On the contrary, some scholars argue Shakespeare had pursued her; at a time when his family was still suffering financially, a match with the well-off Hathaway family would have improved his standing. In any case, the couple welcomed their first child, Susanna, on 26 May 1583. Two more Shakespeare children, twins Hamnet and Judith, were baptized in Stratford on 2 February 1585.

Read More

⇒ William Shakespeare

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Frank Rich

Sept. 28, 1982

IF Tennessee Williams wants to depend on the kindness of strangers, that's his business -but perhaps he should get references first. In ''a/k/a Tennessee,'' which opened at the South Street Theater Sunday night, the playwright has permitted some well-meaning but misguided souls to create a trivial, anthological revue out of his life's work.

The star and principal creator of ''a/k/a Tennessee'' is Maxim Mazumdar, who was last seen (though not by me) in his one-man celebration of Oscar Wilde, ''Oscar Remembered.'' In his new endeavor, Mr. Mazumdar is joined by two acting accomplices, Carrie Nye and J.T. Walsh. Together and separately they perform fragments culled from more than a dozen Williams plays, ranging from a sweet, early curiosity like ''The Case of the Crushed Petunias'' up to the mishaps of recent vintage. In between comes the narration, which loots the playwright's autobiographical writings to sketch in the details of his life and career. As the entire show runs just over two hours including intermission, it's inevitable that both the author's work and personal history receive short shrift.

Audiences not intimately familiar with the Williams canon may lose their way in ''a/k/a Tennessee.'' Those who love his best works may be shocked to see how cursorily they are treated in this ostensible tribute. Far too often, Mr. Mazumdar seems to select a scene because it either mentions or explains the title of the play at hand; sometimes he throws out the scenes entirely and keeps only the most memorable lines, as if they were song snatches to be stitched into a medley. The acting, under Albert Takazauckas's direction, doesn't help. Because no one in the cast much differentiates one role from the next, ''a/k/a Tennessee'' inadvertently supports the fashionable but spurious contention that Mr. Williams writes the same play over and over again.

As the only woman on stage, Miss Nye bears a crushing burden. Looking immaculately glamorous and speaking in an actressy drawl of the Tallulah Bankhead persuasion, she is ill-suited to virtually every Williams heroine she attempts except the forlorn movie star of ''Sweet Bird of Youth.'' She makes game stabs at Amanda Wingfield and Blanche DuBois, but the whole notion of the icy, dolled-up Miss Nye playing these ravaged belles proves absurd. Her Amanda seems to have flown on to the St. Louis fire escape of ''The Glass Menagerie'' by way of Palm Springs.

The men aren't much better. Mr. Walsh, a pleasant young man with a warm smile, is too soft for a tough customer like Wayne Chance; while he might be perfect for the Gentleman Caller in ''Menagerie,'' he does the son instead - and is promptly chewed up alive by Miss Nye. As for Mr. Mazumdar, he spends most of the evening playing Mr. Williams himself, complete with appropriate eyeglass frames and white-linen suit. Though his affection for his alter ego always shines through, his Southern accent sounds like Peter Sellers doing an impersonation of an Indian.

In his offstage role as the evening's ''deviser,'' Mr. Mazumdar makes progressively more perverse choices. The biographical narratives, accompanied by the rat-a-tat of a news ticker, condense decades into skimpy bulletins: Mr. Williams's personal tragedies (his lover Frank Merlo's death, his sister Rose's lobotomy) pass by almost as perfunctorily as the listing of his Drama Critics Circle awards. Mr. Mazumdar also devotes a lopsided percentage of time to the late Williams plays. If there is indeed a case to be made for ''Outcry'' or ''The Milk Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore,'' it isn't furthered by the painful excerpts we see here. Yet ''a/k/a Tennessee'' dawdles over such failures to the point that some of the playwright's unassailable masterworks emerge as footnotes by comparison.

In one of his early monologues, Mr. Mazumdar actually boasts that ''this entertainment was put together by free association.'' Surely Mr. Williams, who is one of the few giants in the American theater, deserves a tribute from people who might take the trouble to think. Scenes From a Life a/k/a TENNESSEE, facts and fictions of Thomas Lanier Williams: words by Tennessee Williams; devised by Maxim Mazumdar; directed by Al- bert Takazauckas; production design, Peter Harvey; lighting design, Mal Sturchio; production stage manager, William Hare; executive producer, Lawrence Goossen. Presented by June Hunt Mayer. At the South Street Theater, 424 West 42d Street.

WITH: Maxim Mazumdar, Carrie Nye and J.T. Walsh.

A version of this article appears in print on Sept. 28, 1982, Section C, Page 17 of the National edition with the headline: THEATER: AN EDITED TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

0 notes

Note

In Norway, what books are classic? Could you recommend some books that you had to read because of school or books that was written by a Norwegian author and you enjoyed it?

Sure!

Hope you don't mind that I put the titles in the original Norwegian, it's because I didn't want to look up every single official translation.

Anything by Amalie Skram is great, she was a 19th century realist writer and a hardcore feminist. Many of her works are biographical. Specifically, I will recommend her Hellemyrsfolket series, Forraadt, Hieronymus, and Lucie.

Henrik Ibsen is famous, and it's for a reason. His plays are great and way ahead of their time, he's one of the great playwrights in history. Vildanden, Peer Gynt, and En folkefiende (which inspired Jaws! Same themes, only replace "sharks" with "bad drinking water") are my recs for him.

Ludvig Holberg, Denmark insists he's theirs but he was born in Norway so sucks to be them. Erasmus Montanus is my big rec for Holberg, as it's about Rasmus Berg (Berg means Hill), a village boy who returns from college and has now become An Educated Man, thereby changing his name to the more intellectual-sounding Erasmus Montanus. It's a comedy making relentless fun of the educated elite.

Alexander Kielland, another realist writer. The short story Karen is beautiful, and the novel Gift is a delightful critique of the late 19th century Norwegian school system. It's so bad that our main character dies from Latin studies.

Knut Hamsun won the Nobel prize in literature and proceeded to give it to Adolf Hitler as a gift, because he was a nazi. He welcomed the occupation, and was a terrible person in general. If you struggle to separate the art from the artist, don't read Hamsun. If you don't struggle, then the man is infuriatingly good at writing. His prose is just out of this world, and it makes me so mad. Start with Sult, and when you're done hallucinating you can thank me.

Sigrid Unset also won the Nobel prize in literature, and unlike Hamsun she was firmly opposed to the nazis. She won the prize for her Kristin Lavransdatter series, which is historical fiction about a woman living in medieval Norway. Big recommend.

Selma Lagerlöf, not Norwegian but damn good. Another Nobel laureate. I recommend Jerusalem.

H.C. Andersen in case you haven't read him, he's Danish but SO GOOD.

Dag Solstad, I never read him but I intend to, he seems like he'll be right up my alley.

Gerd Nyqvist, I've only read the one novel by her but I liked it very much, it was very Agatha Christie-esque. Avdøde ønsket ikke blomster.

Jostein Gaarder, he's... an interesting guy, and I'll put it this way, if he'd been an English-speaking author he would have been picked up by HBO or Netflix by now. Kabalmysteriet comes to mind.

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there! I'm having a debate with my mother and thought I'd ask an actual Frederick expert. So did he actually have STDs/broken dick to explain his lack of children, was he gay or both? Like what is the source situation? Thanks.

Hi! Oh boy, I am not used to asks and I'm sick, this is gonna get rambly... :'D

Frederick's sexuality has been a subject of debate pretty much since the man himself was a teenager. The story about him sleeping with farm girls and sex workers "because his father kept him away from reputable women" and contracting syphilis/gonnorhea in his youth originates with Johann Georg Zimmermann. Zimmermann was Frederick's contemporary and a doctor. And also Frederick's biggest fan. I vaguely remember a story about him meeting his idol and breaking down in tears afterwards because there was "nobody he loved more than the King of Prussia".

Anyway.

Zimmermann became Frederick's physician in the last months before his death and published multiple books about him afterwards, one of which contained the theory mentioned above. According to him, Frederick was actually super into his wife (and women in general) and they had an amazing time together before the gonnorhea flared back up. This flare up was allegedly treated with a surgery that deformed Frederick's nether region and thus he pretended that he had no interest in his marriage despite loving Elisabeth Christine so very much. Instead, he pretended to be gay for clout in enlightenment circles and so the public would know that the King was still able to fuck.

Sounds wild? Tabloid-y? Absolutely.

Now one would think that, as the last royal physician, Zimms would know best about the state of Frederick's dick. However, a surgeon who also saw the King naked (albeit post mortem) said that there was absolutely nothing unusual to report. Zimmermann doesn't give a source for any of his biographical claims either and even other contemporaries thought he was full of shit (Kotzebue was on his side though. You may know Kotzebue as the reactionary poet and playwright who got assassinated in 1819, in part leading to the so called Karlsbader Beschlüsse. Old Zimms sure moved in a popular crowd).

Still, Zimmermann's writing was used as a source on Frederick's sexuality up until the early 2010s because nothing says "great source!" like unsourced claims about maritial love from someone who was five years old and in Switzerland at the time. Other than Zimmermann, some people (Venohr, Ohff quoting Venohr) also quote an excerpt from an alleged letter from Frederick to an unspecified friend that basically just says "I love my wife's vagina", but that one is probably fake. I'd love to know when it started showing up in literature though.

In the early 2010s, the overall tone shifted (not that nobody noticed that Frederick was queer before, there are 19th century articles about that too iirc and Mitford alluded to it in the 1970s). Newer biographies, like Burgdorf and Blanning, as well as an article for the big Friederisiko exhibition of 2012 clearly state that there is no reasonable doubt that Frederick was (primarily) interested in men (there were a few women that he may have had feelings for, but this post is getting long).

There are other contemporary accounts that suggest relations with men (even if we're not counting Voltaire), there's his poetry (oh God, his poetry...), letters, his general group of associates, and, funnily enough, even Zimmermann, who says that everyone close to the King said he "loved like Socrates Alcibiades" (Zimms, of course, knows better and saw right past the facade or something).

Frederick did definitely try to have kids (at least partly because his dad promised him a trip outside of Prussia if he produced an heir...) and was not successful. This could be due to many reasons, we probably won't ever know the real answer. Maybe his dick really did fall off, maybe he just thought he was impotent, maybe there were some issues on EC's part, maybe he just didn't try enough. What we do know is that he evnetually outsourced the heir-department to his brother (Augustus) William, who was definitely into women and from whom the modern main line of the Hohenzollern descends.

Boy this post is a mess, I hope that any sort of insight was gained from this :'D For a more orderly analysis of Frederick's sexuality and more source quotes I would suggest reading Blanning. Burgdorf is fun to read too, especially for an overview of the people close to Frederick, but he doesn't source his claims properly and is kind of the opposite extreme to the "he was totally straight"-crowd.

TL;DR: Zimmermann was full of shit, but maybe his dick was broken, who are we to judge. He was probably not straight anyway.

Stuff that's not necessarily directly relevant but that I can link to: A personal favourite primary source are the Marwitz letters (which @your-disobedient-servant translated), which are mostly proof for the sexuality of Frederick's younger brother Henry, but which are hilarious to read nonetheless. There's also a man shown in William Hogarth's satirical painting Marriage a la mode from 1743/44 who plays the flute, has Frederick's nose and tan, and is positioned among "the homosexuals" in front of a painting of Ganymede being captured by Zeus in the form of an eagle... That's not really a good source for Frederick's own life, but a fun tidbit on the side about the european gossip situation. Marriage a la mode is an interesting painting. (Article about Frederick's nose in contemporary paintings, I'm sorry I only provide links to useless knowledge)

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is “creative nonfiction,” exactly? Isn’t the term an oxymoron? Creative writers—playwrights, poets, novelists—are people who make stuff up. Which means that the basic definition of “nonfiction writer” is a writer who doesn’t make stuff up, or is not supposed to make stuff up. If nonfiction writers are “creative” in the sense that poets and novelists are creative, if what they write is partly make-believe, are they still writing nonfiction?

Biographers and historians sometimes adopt a narrative style intended to make their books read more like novels. Maybe that’s what people mean by “creative nonfiction”? Here are the opening sentences of a best-selling, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of John Adams published a couple of decades ago:

This does read like a novel. Is it nonfiction? The only source the author cites for this paragraph verifies the statement “weeks of severe cold.” Presumably, the “Christmas storm” has a source, too, perhaps in newspapers of the time (1776). The rest—the light, the exact depth of frozen ground, the packed ice, the ruts, the riders’ mindfulness, the walking horses—seems to have been extrapolated in order to unfold a dramatic scene, evoke a mental picture. There is also the novelistic device of delaying the identification of the characters. It isn’t until the third paragraph that we learn that one of the horsemen is none other than John Adams! It’s all perfectly plausible, but much of it is imagined. Is being “creative” simply a license to embellish? Is there a point beyond which inference becomes fantasy?

One definition of “creative nonfiction,” often used to define the New Journalism of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, is “journalism that uses the techniques of fiction.” But the techniques of fiction are just the techniques of writing. You can use dialogue and a first-person voice and description and even speculation in a nonfiction work, and, as long as it’s all fact-based and not make-believe, it’s nonfiction.

The term “creative nonfiction” is actually a fairly recent coinage, postdating the advent of the New Journalism by about twenty years. The man credited with it is the writer Lee Gutkind. He seems to have first used “creative nonfiction,” in print, anyway, thirty years ago, though he thought that the term originated in the fellowship application form used by the National Endowment for the Arts. The word “creative,” he explained, refers to “the unique and subjective focus, concept, context and point of view in which the information is presented and defined, which may be partially obtained through the writer’s own voice, as in a personal essay.”

But, again, this seems to cover most writing, or at least most writing that holds our interest. It’s part of the author function: we attribute what we read not to some impersonal and omniscient agent but to the individual named on the title page or in the byline. This has little to do with whether the work is classified as fiction or nonfiction. Apart from “just the facts” newspaper journalism, where an authorial point of view is deliberately suppressed, any writing that has life has “unique and subjective focus, concept, context and point of view.”

Maybe Gutkind wasn’t naming a new kind of writing, though. Maybe he was giving a new name to an old kind of writing. Maybe he wanted people to understand that writing traditionally classified as nonfiction is, or can be, as “creative” as poems and stories. By “creative,” then, he didn’t mean “made up” or “imaginary.” He meant something like “fully human.” Where did that come from?

One answer is suggested by Samuel W. Franklin’s provocative new book, “The Cult of Creativity” (Chicago). Franklin thinks that “creativity” is a concept invented in Cold War America—that is, in the twenty or so years after 1945. Before that, he says, the term barely existed. “Create” and “creation,” of course, are old words (not to mention, as Franklin, oddly, does not, “Creator” and “Creation”). But “creativity,” as the name for a personal attribute or a mental faculty, is a recent phenomenon.

Like a lot of critics and historians, Franklin tends to rely on “Cold War” as an all-purpose descriptor of the period from 1945 to 1965, in the same way that “Victorian” is often used as an all-purpose descriptor of the period from 1837 to 1901. Both are terms with a load of ideological baggage that is never unpacked, and both carry the implication “We’re so much more enlightened now.” Happily, Franklin does not reduce everything to a single-factor Cold War explanation.

In Franklin’s account, creativity, the concept, popped up after the Second World War in two contexts. One was the field of psychology. Since the nineteenth century, when experimental psychology (meaning studies done with research subjects and typically in laboratory settings, rather than from an armchair) had its start, psychologists have been much given to measuring mental attributes.

For example, intelligence. Can we assign amounts or degrees of intelligence to individuals in the same way that we assign them heights and weights? One way of doing this, some people thought, was by measuring skull sizes, cranial capacity. There were also scientists who speculated about the role of genetics and heredity. By the early nineteen-hundreds, though, the preferred method was testing.

The standard I.Q. test, the Stanford-Binet, dates from 1916. Its aim was to measure “general intelligence,” what psychologists called the g factor, on the presumption that a person’s g was independent of circumstances, like class or level of education or pretty much any other nonmental thing. Your g factor, the theory goes, was something you were born with.

The SAT, which was introduced in 1926 but was not widely used in college admissions until after the Second World War, is essentially an I.Q. test. It’s supposed to pick out the smartest high-school students, regardless of their backgrounds, and thus serve as an engine of meritocracy. Whoever you are, the higher you score the farther up the ladder you get to move. Franklin says that, around 1950, psychologists realized that no one had done the same thing for creativity. There was no creativity I.Q. or SAT, no science of creativity or means of measuring it. So they set out to, well, create one.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘A dead man will lie’: a poetic resistance walk through Nâzım Hikmet’s Istanbul

Lennart Kruijer, ANAMED Post-doctoral Fellow (2022–2023)

The painting shown above, titled Death of the Poet, was painted in 1967 by Cihat Burak (1915–1994) and can be admired at Istanbul Modern, which hopefully will open again soon. On a rainy afternoon in November 2021, I spent a long time observing this colorful triptych.

It depicts the life and death of the famous Turkish poet, playwright, and novelist Nâzım Hikmet (1902–1963). In a semi-biographical fashion, Burak painted several key episodes and aspects of Hikmet’s eventful life: his early upbringing in a wealthy Ottoman family in Istanbul (top right); the almost fifteen years he spent in prisons across Turkey, a result of his communist sympathies (left); his innovative free-verse poetry, scribbled on the prison walls and bursting from his mind (top left); and, his enduring impact on new generations of protesters (right center). Instead of reiterating Hikmet’s biographical facts here—excellent biographies and introductions are available in English[1]—I want to use this blog post as an opportunity to follow some of the poet’s steps in Istanbul, the city he loved so much and missed so dearly while he was in prison, and later, during his exile in Russia and Bulgaria.[2] I hope that, by tracing Nâzım Hikmet’s Istanbul through poetry and photographs, some well-trodden places in the city may acquire new poetic layers.[3]

Our Nâzım-walk begins on Beyazit Square, the spacious stepped plaza with grey cobblestones in front of the elaborate gate to Istanbul University. Standing on the square, we see people moving in all directions, on their way to attend lectures, to go shopping in the Grand Bazaar, or to be on time for prayer at the nearby Beyazit Camii. Flocks of pigeons also cross the open space, frightened by the constant stream of traffic on the adjacent Ordu Caddesi or attracted by generous tourists sharing their simit. Nowadays, nothing on Beyazit Square reminds one of the tragedy that happened here approximately sixty years ago. A poem by Nâzım Hikmet, titled In Beyazit Square, however, vividly remembers what occurred:

In Beyazit Square

A dead man lies,

a youth of nineteen years,

in the sun by day,

under the stars by night,

in Istanbul, in Beyazit Square.

A dead man lies,

in one hand a notebook,

in one hand his dream gone

before it began, in April 1960,

in Istanbul, in Beyazit Square.

A dead man lies

shot

a bullet-wound

like a red carnation open on his forehead,

in Istanbul, in Beyazit Square.

A dead man will lie,

his blood seeping into the earth

until my country comes with arms and freedom songs

and takes

the great square

by force.

(Original title: Beyazıt Meydanı'ndaki Ölü , transl. by Ruth Christie, from Beyond the Walls, p. 218)[4]

Nâzım wrote this poem in May 1960 as a reaction to the student protests of the so-called “28–29 April Events” (28–29 Nisan Olayları) that took place in Istanbul and Ankara in April of that year. While socio-political unrest had already been building in Turkey for some time—not least because of a strong devaluation of the Turkish Lira and the related rise in commodity prices—these protests were particularly targeted at the authoritarian and repressive rule of the center-right Democrat Party (DP) which ruled in Turkey between 1950 and 1960. The Republican People's Party (CHP), forming the political opposition, was increasingly curtailed by bans on political gatherings, and İsmet İnönü, the party’s leader, was obstructed and even attacked while campaigning. The immediate cause of the protests was the installation of the so-called Committee of Inquest (Tahkikat Komisyonu), which effectively acted as a political court that imprisoned political opponents. During the Istanbul protests on Beyazit Square, the police used excessive violence against the protesting crowd. Besides hundreds of injured students and staff members, a 19-year-old student in Forestry Studies, Turan Emeksiz, was shot in the head and killed.

On the central panel of Burak’s painting, the death of Nâzım Hikmet is situated on Beyazit Square, purposefully conflating the poet’s death with that of his poem’s subject, Turan Emeksiz. This poetic license—Hikmet was not actually killed on the streets but died from a heart attack in Moscow—makes sense: it is likely that Nâzım wrote his poem because he felt a strong affinity with the much younger Turan. The painted metamorphosis and the triptych composition both add to the poem’s theme of resurrection, further evoking its suggestion that each generation produces new heroes, new voices against oppression and social injustice. Years before the horrible events of April 1960, Nâzım had already written about this theme in the magnificent epic poem about Sheikh Bedreddin, a fifteenth-century ‘socialist’ peasant in western Anatolia, whose short-lived revolt was ultimately violently suppressed by the Sultan—staged by Hikmet as a preview of the twentieth-century social revolts he so much supported (“When we say Bedreddin will come again we are saying that his words, his eyes, his breath, will come again through our midst”).

While contemplating these prophetic words, we take Ordu Caddesi and walk to Sultanahmet Square. On the southern side of that square, you can see an imposing building that is strikingly yellow. Between 1938 and 1939, and again in 1950, Nâzım was imprisoned here. The Sultanahmet Jail, also known as the Dersaadet Cinayet Tevkifhanesi (Dersaadet Murder Jail), was one of the most notorious prisons of the city, particularly used to imprison writers, journalists, intellectuals, and artists that were considered political dissidents. Orhan Kemal, a good friend of Nâzım and another influential Turkish author, also spent time behind bars here.[5] Nowadays, the building has been repurposed to accommodate the wealthy, serving as the luxurious environs of the Four Seasons Hotel. The hotel proudly advertises its former use as a prison, exclaiming on their website that “It's not every day you get to stay in a century-old Turkish prison, refurbished for luxury living.” Nâzım Hikmet wrote several poems during his imprisonment here; the following one was written in 1939. I fantasized about reciting it out loud to hotel guests entering and leaving the building or writing it as graffiti on those tempting yellow walls:

In Istanbul, in Tevkifane Prison Yard

In Istanbul, in Tevkifane prison yard,

A sunny winter’s day after the rain,

Clouds, red roof tiles, walls and my face

Trembling in the puddles on the ground.

I am so brave in my spirit, so cowardly,

Whatever there is, strong or weak,

I carry it all,

I thought of the world, my country, and you…

(Original title: İstanbul'da, Tevkifane avlusunda, transl. by Richard McKane, from Beyond the Walls, p. 97)

From the Sultanahmet Prison, we continue our tour, walking across Sultanahmet Square, passing the Hagia Sofia, and then turning right to Gülhane Park, behind Topkapı Sarayı. For once, you are allowed to ignore all these well-known touristic attractions! Instead, go into the park and try to find a walnut tree like the one on the picture. Then read the following poem:

The Walnut Tree

My head is a foaming cloud, inside and outside I’m the sea.

I am a walnut tree in Gülhane Park,

an old walnut tree with knots and scars.

You don’t know this and the police don’t either.

I am a walnut tree in Gülhane Park.

My leaves sparkle like fish in water,

my leaves flutter like silk handkerchiefs.

Break one off, my darling, and wipe your tears.

My leaves are my hands—I have a hundred thousand hands.

Istanbul I touch you with a hundred thousand hands.

My leaves are my eyes, and I am shocked at what I see.

I look at you, Istanbul, with a hundred thousand eyes,

And my leaves beat, beat with a hundred thousand hearts.

I am a walnut tree in Gülhane Park.

You don’t know this and the police don’t either.

(original title: Ceviz Ağacı, transl. by Richard McKane, from Beyond the Walls, p. 197)

This popular poem was written while Nâzım traveled to Balçık (Bulgaria), where he stayed in exile. In some sense, it evokes a feeling of absence, the fate of a fugitive in hiding; the author seems to yearn for his Istanbul roots—a recurrent theme in his later work, especially. A romantic but unverified story goes that Nâzım based the poem on a memory of Gülhane Park from several years before, when he was already sought after by the police. While waiting in the park to meet secretly with his former lover Piraye, he witnessed two cops approaching in the distance, who had been tipped off by an untrustworthy ‘friend.’ Not knowing where to run, Nâzım allegedly decided to climb the nearest walnut tree and hid among its foliage. From there, he saw how the cops, but also Piraye, were looking for him—in vain. Many Turkish people know The Walnut Tree by heart, not in the least through rock musician Cem Karaca’s famous interpretation. Like Nâzım himself, it has become a symbol of resistance. The poem acquired further prominence during the 2013 Istanbul Gezi Park protests, when it featured on the banners and in speeches of the defenders of the park and its trees.[6] As is well known, this peaceful sit-in ended in an extremely violent eviction by the police, killing 22 people and injuring thousands. Returning from Fatih back to ANAMED, you might want to take a little detour and consider Gezi Park the last stop of this poetic resistance walk.

My leaves are my eyes, and I am shocked at what I see. From Bedreddin to Turan Emeksiz to Gezi. Looking at Istanbul through his poems and through the canvas of Burak’s painting, Hikmet would probably still be shocked at what he saw today.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Edward Timms and Saime Göksü, Romantic Communist: the life and Work of Nâzım Hikmet (London: Hurst, 1999).

[2] Some caveats are in place here: I am not a literary scholar, let alone a specialist on the work of Hikmet. I merely write about this subject as a passionate reader of his poetry. Furthermore, I realize many more places and poems could have been included here. Among these, I should definitely mention the Nâzım Hikmet Kültür Merkezi in Kadıköy, which has a great bookstore and a lovely tea garden.

[3] Poetry schmoetry, what about the white cat in the painting?! It seems that Burak painted a so-called Van cat (Van kedisi), which are known for their fluffy white fur and heterochromic eyes; the cute specimen in the painting has a blue and a yellow eye. Hikmet wrote about the presence of cats in the prisons where he stayed (see, for example, the poem Lodos,which was written in Bursa prison), but most likely the painted cat is a reference to the third poem Hikmet ever wrote, Samiye’nin Kedisi, an ode to the old and scruffy cat of his sister Samiye.

[4] I will provide several citations from Hikmet’s work, in English translation. Although I believe in Robert Frost’s dictum that poetry is what gets lost in translation, I think Hikmet’s poetry deserves to be read by non-Turkish readers also. Fortunately, excellent translations are available; I quote primarily from the 2002 volume Nâzım Hikmet. Beyond the Walls. Selected Poems, with translations by Ruth Christie, Richard McKane, and Talât Sait Halman, the latter of whose insightful introduction I also used.

[5] Orhan Kemal and Nâzım Hikmet did not spend time together in this prison. They had become friends in the Bursa Prison, where they stayed between 1940 and 1943. Kemal’s moving memoir In Jail with Nâzım Hikmet (2012, translated by Bengisu Rona) gives a detailed account of these early years. The small but charming Orhan Kemal Museum in Cihangir, not far from ANAMED, also contains some pictures and letters attesting to their friendship.

[6] See Kim Fortuny’s excellent article “Nâzım Hikmet’s ecopoetics and the Gezi Park protests;” Fortuny 2016, Middle Eastern Literatures 19, no. 2: 162–84.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

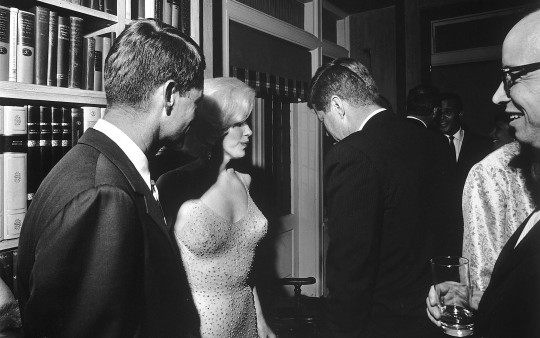

The Story Behind the Only Known Photo of Marilyn Monroe and John F. Kennedy Together

Back in the day, Fred Otash was a hundreds-of-dollars-per-day L.A. private investigator who snooped on the era's biggest names: John Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Rock Hudson. A new Hollywood Reporter story says he claimed he recorded the president and his presumed paramour having sex (the tape has since gone missing).

In notes obtained by THR, Otash writes that he "listened to Marilyn Monroe die." Hours earlier he bugged a heated argument between Monroe, Bobby Kennedy and Peter Lawford. "She said she was passed around like a piece of meat. It was a violent argument about their relationship and the commitment and promises he made to her. She was really screaming and they were trying to quiet her down. She's in the bedroom and Bobby gets the pillow and he muffles her on the bed to keep the neighbors from hearing. She finally quieted down and then he was looking to get out of there."

August 5, 1962, marks the anniversary of the death of Marilyn Monroe, after a barbiturate overdose in her home in the exclusive Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Her sudden death at just 36 years old shocked the nation — in part because just three months prior she had given one of her most famous performances. Decked out in a skin-tight, nude-colored dress, she sang “Happy Birthday” to President John F. Kennedy, who was turning 45 later that month, at a rally at Madison Square Garden on May 19, 1962.

The performance remains a cultural touchstone decades later, and is also noteworthy because that event produced what is considered the only known photograph of Monroe and Kennedy together.

The image, shown here, was taken that night at an after-party at the Manhattan townhouse of Hollywood exec Arthur Krim, by official White House photographer Cecil Stoughton. A print of that image is now for sale, which the auction house Lelands says it was discovered after Stoughton died in 2008; Lelands claims it could be the only surviving version of the photo that Stoughton printed himself from the original negative. (Another version of the photo is part of the LIFE Images Collection.)

Also pictured are the President’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, on the viewer’s left, and Harry Belafonte, who sang “Michael Row the Boat Ashore” that night, in the center back. The bespectacled smiling man on the right is the historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., who admitted later that he was indeed as starstruck as he looks. Monroe had also brought her ex-father-in-law Isidore Miller, playwright Arthur Miller’s father, to meet the President that night. “I thought this would be one of the biggest things in his life” as an “immigrant,” a 1964 LIFE magazine feature reported her saying.

“It was Marilyn who was the hit of the evening,” according to TIME’s recap of the concert in 1962. “Kennedy plainly meant it when he said, ‘I can now retire from politics after having had Happy Birthday sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way.'”

The performance added to rumors that both Kennedy brothers were having affairs with the actor. Among the JFK files released to the public was the FBI’s warning to Bobby Kennedy about an upcoming book that was going to say the two had an affair. “It was pretty clear that Marilyn had had sexual relations with both Bobby and Jack,” James Spada, one of her biographers, told People on the 50th anniversary of her death. (Any claims that the brothers had a role in her death, he clarified, were unsubstantiated.)

According to another biographer, Donald Spoto, Monroe and JFK met four times between October 1961 and August 1962. Their only “sexual encounter” is believed to have taken place two months before the concert in a bedroom at Bing Crosby’s house on Mar. 24, 1962, her masseur Ralph Roberts has said.

So, while rumors of their affair may have ramped up after her performance at Madison Square Garden, their interest in each other may have been winding down at that point, Roberts has claimed. Referring to their March encounter, he said, “Marilyn gave me the impression that it was not a major event for either of them: it happened once, that weekend, and that was that.”

And yet, especially given Monroe’s death and Kennedy’s assassination not too long after, the idea of their relationship still holds its grip on many Americans’ imaginations.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

46 notes

·

View notes

Link

“The difference between Europe and America is that in America 100 years is a long time and in Europe 100 miles is a long distance.” - Dick Gaughan

"At twenty, New York had been authentically the wonder city of the world, a city of wide avenues with the sea at its edge and the smell of the sea in its winds; men from the ends of the earth jostling one in its streets and the loot of the world for sale in its shops. At forty, he reflected, New York was the office in which you worked and the bedroom in which your slept, and in between too many people living too close together. At twenty, nothing was more certain than that you were going to be rich and famous. At forty you knew you'd never be, and you couldn't even pretend you didn't care that money after all wasn't everything, because by the time you were forty you had learned that it very nearly was. At twenty the world made sense; at forty you looked around you with the helpless, numb bewilderment of a man lost in a strange land. At twenty you had a whole lifetime before you; at forty you had, with luck, twenty years. And twenty years wasn't so much. It could be spanned with a memory. It could pass in the twinkling of an eye. It had." - Thomas Bell, There Comes a Time (Little, Brown) 1946

Lemkos are an ethnic minority native to the Carpathian mountains around the present-day Polish-Slovak border. Tens of thousands of them arrived in the U.S at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries, settling mainly around Pittsburgh (Andy Warhol’s family among them) and Cleveland. Thomas Bell’s great novel Out of This Furnace describes several generations of Lemkos around the steel mill in Braddock, Pennsylvania.

Walter Maksimovich and Bogdan Horbals’s wonderful monograph Lemko Folk Music in America, 1928-30 (published by the authors in 2008) describes the details of the recordings of Lemko music for the Okeh, Columbia, and Brunswick labels, instigated and developed by Stefan Shkimba, a streetcar motorman from Brooklyn. Much of that music, along with that of other Rusyns of the old district of Galicia, has been reissued on the CD that accompanies Maksimovich’s book as well as his YouTube channel and other reissues including Christopher King’s Ukrainian and Lemko String Bands in America (JSP, 2011). A handful of labels during the 1940s continued the attempt to document and proliferate music made in the U.S. of Lemkos and Rusyns during the 1940s.

Among them was Poprad, named for the region surrounding the river of the same name that flows from northern Slovakia to southern Poland. The label was apparently run by cultural worker and Lemko activist Nicholas A. Cislak (b. May 8, 1910; d. July 4, 1988). Cislak was born in Uscie Ruskie, Poland, according to his WWII draft registration and married in 1937 in Toronto to a 16 year old named Mary who was born in Brooklyn. The two came to the U.S. together in October, settling in Manhattan where Cislak worked at Schrafft’s Restaurant on W. 23rd St in the 1940s. He was an artist, playwright, and an active member of the Lemko Association based in Philadelphia. About a dozen discs are known to have been made in the late 40s and early 50s on the Poprad label in Elizabeth, New Jersey according to Maksimovich. Poprad’s first releases were by the violinist Orest Turkowsky, but Cislak also brought in a singing accordionist named Wolodya Gonos and a Brooklyn musician named Andrew Kuriplach. Kuriplach, in turn, brought in a few other musicians who recorded the performances presented on this collection.

Andrej Kuriplach was born Oct. 27, 1903. Walter Maksimovich was told by an acquaintance of Kuriplach’s that he was from a village called Woroblyk (Wroblik in Polish) near Rymanow Zdroj in present-day Poland, but Kuriplach’s Ellis Island documentation and his Declaration of Intent to naturalize as a U.S. citizen gives his hometown as Kobulinka (Koberljutza), about 70 miles due south of Rymanow Zdroj near Michalovce in present-day eastern Slovakia He arrived Jan. 16, 1921 and married a woman named Miriam (Mary b. 1901 in Pennsylvania; d. 2002). He delcared his trade on arrival as "cooper" and wound up working for the National Sugar Company on Long Island. He lived intially at 177 Indian St. in the Greepoint section of Brooklyn, before moving six blocks away to 52 Clay St. (His house burned down in a five alarm fire in originating in a nearby warehouse in 1952.) They had two at least two children, John (b. 1928) and Eva (b. 1930).

We have, at present, no biographical data on the performers on these recordings. We know only that they were “produced” or “managed” by Kuriplach and were likely members of his community.

Coincident with these recordings was the ethnic cleansing of Lemkos from their native home by the Communist regime that had taken charge in Poland. During the period 1944-46, Lemko and other Rusyn mountain villagers were quickly, systemically, and forcibly resettled and assimilated in the interiors of the countries in which their homelands were bordered. The efforts of their diaspora in the U.S. in particular have been significant to the conservation of their language and culture.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black bi/lesbian women

Day 1 - Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (1886-1939)

Ma Rainey was the first Vaudeville entertainer to incorporate the blues into her performances, which led to her to – perhaps justifiably – become known as the “Mother of the Blues.” Although she was married, Rainey was known to take women as lovers, and her song “Prove It on Me Blues” directly references her preference for male attire and female companionship. Rainey often found herself in trouble with the police for her lesbian behavior, including an incident in 1925 when she was arrested for taking part in an orgy at home involving women in her chorus. Bessie Smith bailed her out of jail.

Day 2 - Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960)

Zora Neale Hurston was an American folklorist, anthropologist, and author during the Harlem Renaissance. During her lifetime, she published four novels and more than 50 short stories, plays and essays. She is perhaps best known for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937. Today, nearly every black woman writer of significance – including Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker – acknowledges Hurston as a key influence. Although she was never public about her sexuality, the book Wrapped in Rainbows, the first biography of Zora Neale Hurston in more than 25 years, explores her deep friendships with luminaries such as Langston Hughes, her sexuality and short-lived marriages, and her mysterious relationship with vodou.

Day 3 - Bessie Smith (1894-1937)

Widely referred to as The Empress of the Blues, Bessie Smith is considered one of the most popular female blues singers of the 1920s and 1930s and is credited, along with Louis Armstrong, as a major influence on jazz vocalists to this day. Bessie Smith began her professional career in 1912 by singing with Ma Rainey and subsequently performed in various touring minstrel shows and cabarets. As a solo artist, Smith was an integral part of Columbia’s Race Records, and her albums each sold 20,000 copies or more. Although married to a man named Jack Gee, Smith had an ongoing affair with a chorus girl named Lillian Simpson.

Day 4 - Mabel Hampton (1902–1989)

Mabel Hampton was a dancer during the Harlem Renaissance and later became an LGBT historian, philanthropist and activist. She met her partner, Lillian Foster, in 1932 and the two stayed together until Foster’s death in 1978. Hampton marched in the first National Gay and Lesbian March on Washington, and she appeared in the films Silent Pioneers and Before Stonewall. In 1984, Hampton spoke at New York City’s Lesbian and Gay Pride Parade. Hampton’s collection of memorabilia, ephemera, letters and other records documenting her history are housed at the Lesbian Herstory Archives and provide a window into the lives of black women and lesbians during the Harlem Renaissance.

Day 5 - Josephine Baker (1906–1975)

Josephine Baker was the 20th century’s “first black sex symbol.” An American dancer, singer and actress, Baker renounced her American citizenship in 1937 to become French. Despite the fact she was based in Europe, she participated in the American Civil Rights Movement in her own way. She adopted adopting 12 multi-ethnic orphans (long before Angelina Jolie) whom she called the “Rainbow Tribe,” she refused to perform for segregated audiences (which helped to force the integration of performance venues in the United States) and she was the only woman invited to speak at the March on Washington with Martin Luther King, Jr. Although she was married four times, her biographers have since confirmed her multiple affairs with women, including Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.

Day 6 - Gladys Bentley (1907-1960)

Gladys Bentley was an imposing figure. She was a 250-pound, masculine, dark-skinned, deep-voiced jazz singer who performed all night long at Harlem’s notorious gay speakeasies during the Harlem Renaissance while wearing a white tuxedo and top hat. Bentley was notorious for inventing obscene lyrics to popular songs, performing with a chorus line of drag queens behind her piano, and flirting with women in her audience from the stage. Unlike many in her day, she lived her life openly as a lesbian and claimed to have married a white woman in Atlantic City. An article in Ebony magazine quoted her as saying, “It seems I was born different. At least, I always thought so …. From the time I can remember anything, even as I was toddling, I never wanted a man to touch me.”

Day 7 - Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965)

Lorraine Hansberry was an African-American playwright and author. Her best known work, A Raisin in the Sun, was inspired by her family’s own battle against racial bias in Chicago. Hansberry explored controversial themes in her writings in addition to racism in America, including abortion, discrimination, and the politics of Africa. In 1957 she joined the lesbian organization Daughters of Bilitis and contributed letters to their magazine, The Ladder, that addressed feminism and homophobia. While she addressed her lesbian identity in the articles she wrote for the magazine, she wrote under the initials L.H. for fear of being discovered as a black lesbian.

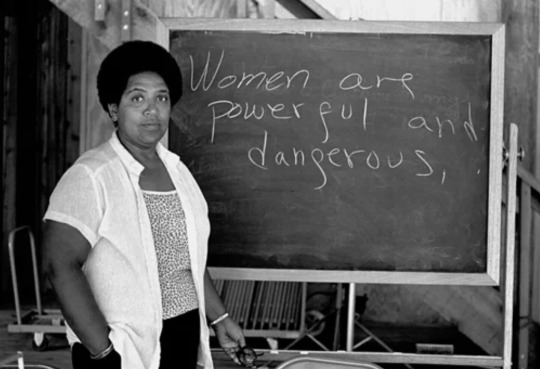

Day 8 - Audre Lorde (1934–1992)

In her own words, Audre Lorde was a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Lorde began writing poetry at age 12 and published her first poem in Seventeen magazine at age 15. She helped found Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the world’s first publisher run by women of color, in 1980. Her poetry was published regularly throughout her life and she served as the State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992. Lorde explored issues of class, race, age, gender and – after a series of cancer diagnoses — health, as being fundamental to the female experience. She died of liver cancer in 1992.

Day 9 - Barbara Jordan (1936–1996)

Representative Barbara Jordan (D-Texas) was the first African-American woman elected to Congress from a southern state. In 1976, she delivered the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention, marking the first time an African-American woman had ever done so. Her speech has since been ranked as one of the top 100 American Speeches of the 20th century and is considered by some historians to be among the best convention keynote speeches in modern history. Although Jordan never publicly acknowledged her sexual orientation, her Houston Chronicle obituary mentioned her longtime companion of more than 20 years, Nancy Earl. Her legacy inspired the Jordan Rustin Coalition, a Los Angeles-based organization dedicated to the empowerment of Black LGBT people and families.

Day 10 - June Jordan (1936-2002)

June Jordan was one of the most widely-published and highly-acclaimed African-American writers of her generation. A poet, playwright, speaker, teacher, journalist and essayist Jordan was also known for her fierce commitment to human rights political activism. Jordan said of her bisexuality, “bisexuality means I am free and I am as likely to want to love a woman as I am likely to want to love a man, and what about that? Isn’t that what freedom implies?” Her influential voice defined the cutting edge of both American poetry and politics during the Civil Rights Movement. She published 27 before her death from breast cancer in 2002 at the age of 65. Three more of her books have been published posthumously.

7K notes

·

View notes

Note

28, 24, 19, 9

In response to: Tumblr History Ask Meme: https://lady-plantagenet.tumblr.com/post/643743359209472000/ive-seen-plenty-of-tumblr-ask-challenges-but

24. Who do you consider to be one of the most underrated historical figures?

Ok. I won’t say Vlad the Impaler because he’s not strictly speaking underrated as much as he is misunderstood. I think a lot of you expect me to say George of Clarence but as much as I believe he should be studied far more than he is - maybe not much for himself (from an academic point of view I say this) as for a case study on the instability of the late medieval faith in the sanctity of the crown, the bastard feudalism phenomenon, private justice and maybe how a posterity can develop strangely throughout the centuries with little historicity. But his short life and the fact that he is stronger in his impact on history via his failure than his deeds I would say Richard Neville 16th Earl of Warwick is truly history’s most underrated figure. I have yet to read a biography of him but the fact of the matter is that his presence in the tale of the development of British history, society and constitution seems strong enough to merit a mention of him in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and even among most of the works of Whig and Enlightenment historians who centuries later feel threatened by the type of person he represented to them (‘anti-progress’, ‘an impediment to the development of democracy’). Clarence is always a question of what could have been whereas Warwick lived long enough to live a truly studeable life. There was no one like him before in English Medieval history and there would be no one like him - I’ve seen strange takes on him by his biographers ‘populist’, ‘self-publicist’, ‘visionary’ and of course ‘legend’ (and indeed as it seems of a presence made known to all people). I have yet to check if these claims have any logic behind them but from what I can see they very well could. He indeed personified an era in itself and yet he’s hardly a household name nowadays??

28. Do you have a favourite “dream team” of historical figures living at the same time in a specific era of history?

The three dudes I mentioned above DEFINITELY. They could have all met had Edward IV also answered Pius II’s call to crusade. Of course, I’d rather there not be a crusade... because well... no one wants that. Vlad the Impaler was at the other side of the continent and tbh circumstances would need to probably involve the Holy Roman Empire for the three parties to ever intersect in any way. Warwick and Vlad were at opposite ends where policy was concerned... Vlad culled the boyars who he deemed corrupt at the gathering of the Tîrgoviste court and Warwick (and Clarence) was basically their English counterpart. Although, Vlad believed his nobles to have sold out the country to the Ottomans and been responsible for his father and brother’s death so there’s that going. All three did care for their country though so I guess they can unite under that and had reputations for embodying late medieval chivalry. Of course the caveat is that while Warwick (and Clarence at one point) was popular with the nobles, Vlad was deeply hated by them. But yeah I still cannot genuinely believe they were all alive at the same time like that’s actually insane. Of course, throw in Louis XI of France (another very interesting monarch) but technically speaking he and Warwick were a dream team XD.

19. What’s your favourite historical book?

Ive answered this before here :)x . I would otherwise switch to favourite fiction book but I’ve also spoken about that on here XD. And I’ll not talk about another because one can only have one favourite ey? I’ll link them here:

9. Favourite historical film?

Hmm... It’s a toss-up between Man for All Seasons and Lion in Winter. The former is about Thomas More and is extremely smart about how it handles the real cause of his downfall and the dialogue is utterly superb together with the acting. It also gets the aesthetics very down to a t and is one of those pieces that doesn’t attempt to simplify everything by making a hero or a villain out of anyone and that’s what it makes it a true tragedy. I also feel that the playwright truly understood how Catholicism= ignorance is not ok (a trope I rly hate). I also appreciate how Thomas More is shown as someone dedicated to his ideals not team Catherine, Anne or whatever; the aforementioneds are actually insignificant to the whole thing, which while might not be very accurate is refreshing.

The latter is an fictionalised Angevin drama set at the fictional Christmas court of Chignon with the whole Angevin crew: Henry, Eleanor, the three remaining sons and of course Philippe of France ready to throw a wrench. For a comedy it is extraordinary smart and I feel like it also has this vague self-awareness to it which has really survived the test of time (like the ‘it’s 1183 and we all still carry knives’ line hhh). Yet somehow it had its heartfelt moments eg Richard I and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s exchange in the gardens. Geoffrey of Brittany is also a trip to watch (who can forget the ‘I know, you know, you know I know, I know you know I know you know’ line?). Also it was great to see Peter O’Toole reprise his role as Henry II from Becket. I must say I much prefer him here. Despite being a comedy, the aesthetics and musical soundtrack never fail to draw in the necessary splendour and emotion and the acting is sensational.

#🍷❤️#I did say I would answer something today!#btw I’ll post fancy underline links tommorow when I get back onto my laptop#I appreciate it looks a bit trash#vlad the impaler#richard neville 16th earl of warwick#richard neville earl of warwick#lord warwick#warwick the kingmaker#george of clarence#george duke of clarence#george plantagenet

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie Dressler (born Leila Marie Koerber, November 9, 1868 – July 28, 1934) was a Canadian stage and screen actress, comedian, and early silent film and Depression-era film star. In 1914, she was in the first full-length film comedy. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress in 1931.

Leaving home at the age of 14, Dressler built a career on stage in traveling theatre troupes, where she learned to appreciate her talent in making people laugh. In 1892, she started a career on Broadway that lasted into the 1920s, performing comedic roles that allowed her to improvise to get laughs. From one of her successful Broadway roles, she played the titular role in the first full-length screen comedy, Tillie's Punctured Romance (1914), opposite Charlie Chaplin and Mabel Normand. She made several shorts, but mostly worked in New York City on stage. During World War I, along with other celebrities, she helped sell Liberty bonds. In 1919, she helped organize the first union for stage chorus players.

Her career declined in the 1920s, and Dressler was reduced to living on her savings while sharing an apartment with a friend. In 1927, she returned to films at the age of 59 and experienced a remarkable string of successes. For her performance in the comedy film Min and Bill (1930), Dressler won the Academy Award for Best Actress. She died of cancer in 1934.

Marie Dressler's original name was Leila Marie Koerber. She was born on November 9, 1868, Cobourg, Ontario. She was one of the two daughters of Anna (née Henderson), a musician, and Alexander Rudolph Koerber (b. April 13, 1826, Lindow, Neu-Ruppin, Germany – d. November 1914, Wimbledon, Surrey, England), a German-born former officer in the Crimean War. Leila's elder sister, Bonita Louise Koerber (b. January 1864, Ontario, Canada – d. September 18, 1939, Richmond, Surrey, England), later married playwright Richard Ganthony.

Her father was a music teacher in Cobourg and the organist at St. Peter's Anglican Church, where as a child Marie would sing and assist in operating the organ. According to Dressler, the family regularly moved from community to community during her childhood. It has been suggested by Cobourg historian Andrew Hewson that Dressler attended a private school, but this is doubtful if Dressler's recollections of the family's genteel poverty are accurate.

The Koerber family eventually moved to the United States, where Alexander Koerber is known to have worked as a piano teacher in the late 1870s and early 1880s in Bay City and Saginaw (both in Michigan) as well as Findlay, Ohio. Her first known acting appearance, when she was five, was as Cupid in a church theatrical performance in Lindsay, Ontario. Residents of the towns where the Koerbers lived recalled Dressler acting in many amateur productions, and Leila often irritated her parents with those performances.

Dressler left home at the age of 14 to begin her acting career with the Nevada Stock Company, telling the company she was actually 18. The pay was either $6 or $8 per week, and Dressler sent half to her mother. At this time, Dressler adopted the name of an aunt as her stage name. According to Dressler, her father objected to her using the name of Koerber. The identity of the aunt was never confirmed, although Dressler denied that she adopted the name from a store awning. Dressler's sister Bonita, five years older, left home at about the same time. Bonita also worked in the opera company. The Nevada Stock Company was a travelling company that played mostly in the American Midwest. Dressler described the troupe as a "wonderful school in many ways. Often a bill was changed on an hour's notice or less. Every member of the cast had to be a quick study". Dressler made her professional debut as a chorus girl named Cigarette in the play Under Two Flags, a dramatization of life in the Foreign Legion.

She remained with the troupe for three years, while her sister left to marry playwright Richard Ganthony. The company eventually ended up in a small Michigan town without money or a booking. Dressler joined the Robert Grau Opera Company, which toured the Midwest, and she received an improvement in pay to $8 per week, although she claimed she never received any wages.

Dressler ended up in Philadelphia, where she joined the Starr Opera Company as a member of the chorus. A highlight with the Starr company was portraying Katisha in The Mikado when the regular actress was unable to go on, due to a sprained ankle, according to Dressler. She was also known to have played the role of Princess Flametta in an 1887 production in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She left the Starr company to return home to her parents in Saginaw. According to her, when the Bennett and Moulton Opera Company came to town, she was chosen from the church choir by the company's manager and asked to join the company. Dressler remained with the company for three years, again on the road, playing roles of light opera.

She later particularly recalled specially the role of Barbara in The Black Hussars, which she especially liked, in which she would hit a baseball into the stands. Dressler remained with the company until 1891, gradually increasing in popularity. She moved to Chicago and was cast in productions of Little Robinson Crusoe and The Tar and the Tartar. After the touring production of The Tar and the Tartar came to a close, she moved to New York City.

In 1892, Dressler made her debut on Broadway at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in Waldemar, the Robber of the Rhine, which only lasted five weeks. She had hoped to become an operatic diva or tragedienne, but the writer of Waldemar, Maurice Barrymore, convinced her to accept that her best success was in comedy roles. Years later, she appeared in motion pictures with his sons, Lionel and John, and became good friends with his daughter, actress Ethel Barrymore. In 1893, she was cast as the Duchess in Princess Nicotine, where she met and befriended Lillian Russell.

Dressler now made $50 per week, with which she supported her parents. She moved on into roles in 1492 Up To Date, Girofle-Girofla, and A Stag Party, or A Hero in Spite of Himself After A Stag Party flopped, she joined the touring Camille D'Arville Company on a tour of the Midwest in Madeleine, or The Magic Kiss, as Mary Doodle, a role giving her a chance to clown.

In 1896, Dressler landed her first starring role as Flo in George Lederer's production of The Lady Slavey at the Casino Theatre on Broadway, co-starring British dancer Dan Daly. It was a great success, playing for two years at the Casino. Dressler became known for her hilarious facial expressions, seriocomic reactions, and double takes. With her large, strong body, she could improvise routines in which she would carry Daly, to the delight of the audience.

Dressler's success enabled her to purchase a home for her parents on Long Island. The Lady Slavey success turned sour when she quit the production while it toured in Colorado. The Erlanger syndicate blocked her from appearing on Broadway, and she chose to work with the Rich and Harris touring company. Dressler returned to Broadway in Hotel Topsy Turvy and The Man in the Moon.

She formed her own theatre troupe in 1900, which performed George V. Hobart's Miss Prinnt in cities of the northeastern U.S. The production was a failure, and Dressler was forced to declare bankruptcy.

In 1904, she signed a three-year, $50,000 contract with the Weber and Fields Music Hall management, performing lead roles in Higgeldy Piggeldy and Twiddle Twaddle. After her contract expired she performed vaudeville in New York, Boston, and other cities. Dressler was known for her full-figured body, and buxom contemporaries included her friends Lillian Russell, Fay Templeton, May Irwin and Trixie Friganza. Dressler herself was 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall and weighed 200 pounds (91 kg).

In 1907, she met James Henry "Jim" Dalton. The two moved to London, where Dressler performed at the Palace Theatre of Varieties for $1500 per week. After that, she planned to mount a show herself in the West End. In 1909, with members of the Weber organization, she staged a modified production of Higgeldy Piggeldy at the Aldwych Theatre, renaming the production Philopoena after her own role. It was a failure, closing after one week. She lost $40,000 on the production, a debt she eventually repaid in 1930. She and Dalton returned to New York. Dressler declared bankruptcy for a second time.

She returned to the Broadway stage in a show called The Boy and the Girl, but it lasted only a few weeks. She moved on to perform vaudeville at Young's Pier in Atlantic City for the summer. In addition to her stage work, Dressler recorded for Edison Records in 1909 and 1910. In the fall of 1909, she entered rehearsals for a new play, Tillie's Nightmare. The play toured in Albany, Chicago, Kansas City, and Philadelphia, and was a flop. Dressler helped to revise the show, without the authors' permission, and in order to keep the changes she had to threaten to quit before the play opened on Broadway. Her revisions helped make it a big success there. Biographer Betty Lee considers the play the high point of her stage career.

Dressler continued to work in the theater during the 1910s, and toured the United States during World War I, selling Liberty bonds and entertaining the American Expeditionary Forces. American infantrymen in France named both a street and a cow after Dressler. The cow was killed, leading to "Marie Dressler: Killed in Line of Duty" headlines, about which Dressler (paraphrasing Mark Twain) quipped, "I had a hard time convincing people that the report of my death had been greatly exaggerated."

After the war, Dressler returned to vaudeville in New York, and toured in Cleveland and Buffalo. She owned the rights to the play Tillie's Nightmare, the play upon which her 1914 movie Tillie's Punctured Romance was based. Her husband Jim Dalton and she made plans to self-finance a revival of the play. The play fizzled in the summer of 1920, and the production was disbanded. In 1919, during the Actors' Equity strike in New York City, the Chorus Equity Association was formed and voted Dressler its first president.

Dressler accepted a role in Cinderella on Broadway in October 1920, but the play failed after only a few weeks. She signed on for a role in The Passing Show of 1921, but left the cast after only a few weeks. She returned to the vaudeville stage with the Schubert Organization, traveling through the Midwest. Dalton traveled with her, although he was very ill from kidney failure. He stayed in Chicago while she traveled on to St. Louis and Milwaukee. He died while Marie was in St. Louis, and Marie then left the tour. His body was claimed by his ex-wife, and he was buried in the Dalton plot.

After failing to sell a film script, Dressler took an extended trip to Europe in the fall of 1922. On her return she found it difficult to find work, considering America to be "youth-mad" and "flapper-crazy". She busied herself with visits to veteran hospitals. To save money she moved into the Ritz Hotel, arranging for a small room at a discount. In 1923, Dressler received a small part in a revue at the Winter Garden Theatre, titled The Dancing Girl, but was not offered any work after the show closed. In 1925, she was able to perform as part of the cast of a vaudeville show which went on a five-week tour, but still could not find any work back in New York City. The following year, she made a final appearance on Broadway as part of an Old Timers' bill at the Palace Theatre.

Early in 1930, Dressler joined Edward Everett Horton's theater troupe in Los Angeles to play a princess in Ferenc Molnár's The Swan, but after one week, she quit the troupe. Later that year she played the princess-mother of Lillian Gish's character in the 1930 film adaptation of Molnar's play, titled One Romantic Night.

Dressler had appeared in two shorts as herself, but her first role in a feature film came in 1914 at the age of 44. In 1902, she had met fellow Canadian Mack Sennett and helped him get a job in the theater. After Sennett became the owner of his namesake motion picture studio, he convinced Dressler to star in his 1914 silent film Tillie's Punctured Romance. The film was to be the first full-length, six-reel motion picture comedy. According to Sennett, a prospective budget of $200,000 meant that he needed "a star whose name and face meant something to every possible theatre-goer in the United States and the British Empire."

The movie was based on Dressler's hit Tillie's Nightmare. She claimed to have cast Charlie Chaplin in the movie as her leading man, and was "proud to have had a part in giving him his first big chance." Instead of his recently invented Tramp character, Chaplin played a villainous rogue. Silent film comedian Mabel Normand also starred in the movie. Tillie's Punctured Romance was a hit with audiences, and Dressler appeared in two Tillie sequels and other comedies until 1918, when she returned to vaudeville.

In 1922, after her husband's death, Dressler and writers Helena Dayton and Louise Barrett tried to sell a script to the Hollywood studios, but were turned down. The one studio to hold a meeting with the group rejected the script, saying all the audiences wanted is "young love." The proposed co-star of Lionel Barrymore or George Arliss were rejected as "old fossils". In 1925, Dressler filmed a pair of two-reel short movies in Europe for producer Harry Reichenbach. The movies, titled the Travelaffs, were not released and were considered a failure by both Dressler and Reichenbach. Dressler announced her retirement from show business.

In early 1927, Dressler received a lifeline from director Allan Dwan. Although versions differ as to how Dressler and Dwan met, including that Dressler was contemplating suicide, Dwan offered her a part in a film he was planning to make in Florida. The film, The Joy Girl, an early color production, only provided a small part as her scenes were finished in two days, but Dressler returned to New York upbeat after her experience with the production.

Later that year, Frances Marion, a screenwriter for the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio, came to Dressler's rescue. Marion had seen Dressler in the 1925 vaudeville tour and witnessed Dressler at her professional low-point. Dressler had shown great kindness to Marion during the filming of Tillie Wakes Up in 1917, and in return, Marion used her influence with MGM's production chief Irving Thalberg to return Dressler to the screen. Her first MGM feature was The Callahans and the Murphys (1927), a rowdy silent comedy co-starring Dressler (as Ma Callahan) with another former Mack Sennett comedian, Polly Moran, written by Marion.

The film was initially a success, but the portrayal of Irish characters caused a protest in the Irish World newspaper, protests by the American Irish Vigilance Committee, and pickets outside the film's New York theatre. The film was first cut by MGM in an attempt to appease the Irish community, then eventually pulled from release after Cardinal Dougherty of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia called MGM president Nicholas Schenck. It was not shown again, and the negative and prints may have been destroyed. While the film brought Dressler to Hollywood, it did not re-establish her career. Her next appearance was a minor part in the First National film Breakfast at Sunrise. She appeared again with Moran in Bringing Up Father, another film written by Marion. Dressler returned to MGM in 1928's The Patsy as the mother of the characters played by stars Marion Davies and Jane Winton.

Hollywood was converting from silent films, but "talkies" presented no problems for Dressler, whose rumbling voice could handle both sympathetic scenes and snappy comebacks (the wisecracking stage actress in Chasing Rainbows and the dubious matron in Rudy Vallée's Vagabond Lover). Frances Marion persuaded Thalberg to give Dressler the role of Marthy in the 1930 film Anna Christie. Garbo and the critics were impressed by Dressler's acting ability, and so was MGM, which quickly signed her to a $500-per-week contract. Dressler went on to act in comedic films which were popular with movie-goers and a lucrative investment for MGM. She became Hollywood's number-one box-office attraction, and stayed on top until her death in 1934.

She also took on serious roles. For Min and Bill, with Wallace Beery, she won the 1930–31 Academy Award for Best Actress (the eligibility years were staggered at that time). She was nominated again for Best Actress for her 1932 starring role in Emma, but lost to Helen Hayes. Dressler followed these successes with more hits in 1933, including the comedy Dinner at Eight, in which she played an aging but vivacious former stage actress. Dressler had a memorable bit with Jean Harlow in the film:

Harlow: I was reading a book the other day.

Dressler: Reading a book?

Harlow: Yes, it's all about civilization or something. A nutty kind of a book. Do you know that the guy said that machinery is going to take the place of every profession?

Dressler: Oh my dear, that's something you need never worry about.

Following the release of Tugboat Annie (1933), Dressler appeared on the cover of Time, in its issue dated August 7, 1933. MGM held a huge birthday party for Dressler in 1933, broadcast live via radio. Her newly regenerated career came to an abrupt end when she was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 1934. MGM head Louis B. Mayer learned of Dressler's illness from her doctor and reportedly asked that she not be told. To keep her home, he ordered her not to travel on her vacation because he wanted to put her in a new film. Dressler was furious but complied. She appeared in more than 40 films, and achieved her greatest successes in talking pictures made during the last years of her life. The first of her two autobiographies, The Life Story of an Ugly Duckling, was published in 1924; a second book, My Own Story, "as told to Mildred Harrington," appeared a few months after her death.