#also i feel like so many stances from these revolutionary marxists are like

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Also it's fucked up to yell at members of marginalized communities for acting within the two party system and not burning it all down when you don't have a plan. People are not your fucking sacrificial lambs to skewer and roast on a stick

#okay i actually need to stop but i am genuinely so angry at this virtue signalling and hyperindividualism#horseshoe theory at its finest#also it's super odd they claim to oppose genocide and we're selfish for HOLDING A CANDIDATE ACCOUNTABLE for ending a genocide when their#third party candidates dont fucking know what they are talking about and are Russia apologists?????#like are you fucking kidding me#grace rants#delete later#kamala harris#joe biden#donald trump#jd vance#election 2024#also i feel like so many stances from these revolutionary marxists are like#omfggggg i hate america it's terrible we need to overhaul everything but they fail to mention or empathize with the populations actually#living here their community members!!!! like okay you seem to hate america and americans which I AM so i dont really fuckin trust you to#fight for me

155 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on the American Communist Party (ACP) or its members (Haz Al Din, Jackson Hinkle, etc)?

I like ACP and I am hopeful for them. I started out critical of them initially (back when they were the infrared collective), but I tried to focus on the actual content of their message as oppose to the presentation of it (the abrasive characters they had). And a while back, before ACP was a thing, i said to a friend who is now in the ACP, that I believe overtime infrared will mature. I felt that with the unparalleled strong historical and Marxist analysis they had, they would either have to mature or it would lead them to mature regardless.

I mean they are talking about things that, I for example have mentioned many times before. Gender stuff being a ruling class microidentity and pharma exploitation. Or that the type of revolutionary involvement that the people participate in the west being ineffective because they're ruling class's version of protests. But they present that with an effective Marxist analysis which is something that has been missing from the western left.

At the moment I see them as the only Communist party that is openly and properly Marxist. Has an anti-sex trade stance, openly venerates Hamas as freedom fighters. You will notice that all of their existing communist and socialist parties dont take a stance or cannot take a stance because they are pandering to liberals. CPUSA openly told their members to vote for Kamala. So they tail liberals.

They've done a lot of work in their community for a party that's barely 3 months old. They're implementing some proper historical methods of organizing (which CPUSA PSL etc don't imo). So I do think they will be successful.

Now the following part is purely based on gut and vibes, not necessarily a logical thing: Jackson Hinkle is someone that I feel, something is off about him. He is important to the ACP because he reaches the masses in a more layman way. While Haz does the theory well. But actually find Jackson to be more immature. Haz was immature initially back when he started this collective and he was 25. And I predicted that he would mature and stop saying rage bait things, and he has.

I think that online leftists can't get past the original rage baiting infrared did. Or like the MAGA Communism thing. Or fully understand their tactics. Online leftists also don't want to reach out to conservatives in any manner because they think every single conservative is a Nazi. Which is of course wrong. There are about 50% of the population. A communist vanguard party must reach out to them.

I also think that more women should join this party so as to drive change internally for women's issues. Also interestingly I've been hearing Buzz from Chinese media and accounts within China celebrating ACP and saying that they have been waiting for a proper American Communist party. So the world knows that America didn't have a proper Communist party for ages. Everyone except Americans know that the CPUSA was defanged back in the 60s. Every version of communist that has appeared within the left in America has basically just been a liberal with communist veneers.

I now know a number of people in the ACP. Many were critics initially. So I think it's worthwhile to actually listen to their materials. Call in to their show and ask questions.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Got a theory on how socialism went from “working class idpol” to “PMC idpol”, while still claiming to be the former?

There is, as they say, a lot to unpack here.

So first of all, calling socialism ‘working class idpol’ isn’t necessarily wrong but a) phrasing it like that makes me physically cringe and b) it’s really pretty reductionist. The official Marxist doctrine isn’t that the proletariat is especially virtuous or enlightened or deserving, its that it’s exploitation is necessary to the functioning of capitalism, meaning that as capitalism becomes ever more universal workers will have both the means and motive to overthrow it. Though, like, not to say that there isn’t a lot of ‘working class idpol’ in there. If you want to get all Early Christian Heresy about it, I think that got denounced as I want to say Workerism at some point? Something like that.

(Though, like, the period of early Soviet history where people’s class histories was explicitly taken into account in court when determining how harsh a sentence to give them is just very funny in terms of ‘American conservative fever dreams that turn out to have actually happened’. I have a weird sense of humour. Though come to think of it Ascribing Class is actually a pretty useful read in terms of how identity is socially constructed and assigned from on high).

But honestly, well socialism has always been for the working class, the critique that it’s actually by a bunch of genteel delinquents cosplaying as revolutionaries is basically as old as the term. Like, ‘came from a well-to-do family, radicalized when they joined an illicit reading group in school and found Marx’ is basically a cliche of early Bolshevik biographies, and the closest to industrial labour quite a lot of them got was volunteering to teach night schools for the actual proletariat. Like, it was something of an embarrassment for a while the degree that the movement of the working class was actually composed almost entirely of professional revolutionaries and radical intelligentsia – the creation of a socialist labour movement was a deliberate and conscious project which took a decent amount of time to really work, with many (many, many, many) failures along the way. (Too radical and anti-religious and feminist and internationalist for the salt of the earth working types, you understand)

But anyway, all that’s mostly tangential, mostly to say that lawyers and teachers being strident Marxists isn’t even close to new. To at least approach answering your actual question – okay, with apologies to Barbara Ehrenreich, I really feel like ‘Professional-Managerial Class” as a term has gotten so warped by The Discourse that it’s actual use is fairly limited. Like, the Wikipedia article somehow includes ‘teachers’ and ‘nurses’ as central examples (even leaving aside accuracy if you’re a serious socialist on I feel like preemptively disavowing one of the only halfway vital sections of the American labour movement is anathema on a purely tactical level). A lot of the use is just, well, vulgar identity politics – imagining class divides based on culture and affect rather than material circumstances. And to the people the term is actually useful for – wait, have you seriously met many managers or corporate lawyers who call themselves socialists? Like, seriously? I mean, I guess so did Louis Napoleon, but I wouldn’t exactly call him central to the movement.

Alright, sorry, I’m being intentionally obtuse, here. So to answer the question I think you’re asking-

The contemporary boost in the prominence of socialism (in the discourse and in terms of number of publications, if nothing else) has been largely driven by the downwardly mobile children of relatively comfortable parents, both white collar workers and yes, of the professional-managerial class. Due to shifts in economics, culture, and government policy over the last several decades, they overwhelmingly at least attempted to get a college degree. Generally speaking, they were radicalized at least as much by the fact that the system that supported their parents has singularly failed to do so for them as by any particular points of history or theory. Once a significant number in various social circles and cultural scenes were genuinely radicalized, it just became a generally fashionable or acceptable stance to strike, and a useful vocabulary for anyone with even vaguely compatible issues or interests to articulate themselves in.

The natural and inevitable consequence of this is that the modern, western iteration of the socialist movement (such as it is) is generally expressed in the cultural vernacular of people raised as comfortable, liberal children of the American dream, or people directly reacting and responding to that culture. It also means that the focuses and idiosyncratic neuroses of the movement are going to have at least as much to do with the culture as with the ideology – such is human nature, unfortunately.

#reply#anon#political theory#socialism#in this essay I will#this is theoretically a writing blog#long#Anonymous

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Jakarta Method, final takeaways

CW: mass death, torture, genocide

The Jakarta Method was a masterpiece. It tells you the story of individual humans while spending most of its time talking about the bigger picture, allowing for a book that informs you while feeling like more than a dry recitation of facts. Bevins puts a lot of effort into humanizing the people in the stories he tells, examining the things they could control and the things they couldn’t. It’s a very empathetic way of telling the story he wants to tell, and the book hurts more because of it.

So, onto the takeaways:

As a leftist, I would like to believe in the resilience of the human spirit, of the impossibility of suppressing the will of the people indefinitely. As it turns out, there’s a very simple four step plan that will crush any leftist organizing that is not underground or heavily armed:

1. Get a bunch of people with guns.

2. Identify anyone who seems like a leftist or community leader.

3. Kidnap them and torture them to death.

4. Rinse and repeat on their allies, friends, and families, as necessary.

This is the titular Jakarta Method, and it was employed (to various degrees) in at least 22 different countries from the 1960s to the 1980s, most notably in Indonesia, where over one million leftists were murdered.

While it’s true that in the literal sense, not all anticommunists are fascists, many are, and all anticommunists are willing to work with fascists to kill communists. There are, as far as I can tell, no exceptions to this rule - anyone claiming the title “anticommunist” will justify just about anything if it means “fighting communism”.

It’s impossible to deny the interconnected nature of anticolonial politics and leftist politics. Anticommunist forces committed anti-indigenous genocide repeatedly in Latin American countries, with the logic that indigenous people were either already communists or natural allies of communists.

A lot of religious leftists were killed and it’s not like communists were killed for being atheists, but it is worth noting how religious (primarily christian) anti-atheist sentiment was used to justify atrocities against communists.

When the death squads come, they don’t distinguish between anarchists and communists, democratic socialists and marxist revolutionaries, social democratics and stalinists, or union organizers and ivory tower intellectuals. They just come for leftists. A lesson worth remembering.

Speaking of, some of the leaders killed or toppled were not truly leftists, for most definitions of the word. Some were just liberals who were insufficiently anticommunist, or hinted at land reform, or otherwise accidentally poked the bear.

Appeasement does not work, or at least it didn’t at the time. You could be as friendly with the US and the capitalist powers that be as you wanted, but if you were on the left, they would come for you eventually. Similarly, on the other side of things, Jimmy Carter did much less than he should have to stop the anticommunist death machine run by the CIA, but the little bit that he did do was taken very poorly by the anticommunists, many of whom felt completely abandoned by the US. If you’re going to take a hammer to the system, don’t half-ass it.

I alluded to this previously, but these death campaigns made the left much worse. For almost the entirety of the 20th century, being a democratic socialist got you killed, even if you won. As a result, the only successful leftist states of the 20th century were the ones with guns. I believe deeply in democracy, but at some point you need a plan for dealing with opponents who don’t.

These lessons still have relevance today. Bolsonaro, in Brazil, made his name as a fervent anticommunist, someone who supported the worst of Brazil’s military regime. He is the most prominent example, but many of the soldiers who filled the mass graves are alive today, and many of them have gone into politics or are now high up in their country’s military hierarchy. If they are given the chance, they will do it again.

Bevins has a few other conclusions, which I haven’t fully evaluated my stance on, but that I think are interesting nonetheless. First, he notes (with compelling data) that aside from five outliers, post-communist countries are mostly worse off than they were under communism, both in terms of their economic power when compared to the US and often also in terms of their political systems.

Second, he points out that the gap between the US and the third world is actually larger than most Americans think it is. The US has profited massively from taking the place of European countries as the primary beneficiary of the worldwide system of colonial extraction, and as a direct result of US meddling from the mid 20th century to the present, the gap is continuing to widen. The countries that closed the gap (South Korea, Japan) were able to do so largely because of a special relationship to the West for Cold War strategic reasons.

Third, and finally, he believes that communism’s defeat in the 20th century was unavoidable. Not due to any intrinsic flaw in communist ideology (though he hardly takes a rosy view of the USSR) but rather due to the resource gap between the First and Second World, and the ruthlessness with which the West was willing to leverage that gap.

It left me with a lot to think about.

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

leftist suriya characters appreciation post

since soorarai pottru, been thinking more about all the explicit leftist characters suriya has played in his career. and i actually mean explicit - characters that are supported by the narrative framing and structure and not just my own headcanons and stuff or a throwaway generic goody-shoe typical hero line. i have been itching to talk about this cos it’s obviously in my field of interests

suriya has played 4 openly various brands of leftist now, and that’s pretty cool! i love that none of them are cookie cutter personalities of each other, they all have their own select trait. this post is a toast to them;

michael vasanth (ayutha ezhuthu, 2004)

vimalan (maattraan, 2012)

iniyan (thaanaa serndha koottam, 2018)

maara (soorarai pottru, 2020)

[small write up on each character with pics behind the cut]

*****

1. michael vasanth (ayutha ezhuthu, 2004)

so michael was his first, said to be inspired by an actual university popular marxist student leader, george reddy. michael is very obviously somewhere along these lines - he himself is within the film known as the leftist student leader on campus with a huge following, much to the chagrin of his professors who want to stamp that out of him. he’s openly engaged in campus politics as well as politics outside, and he’s most definitely no weak willed liberal because he has no problems with violence or direct action, which he organises. he organises villagers to stand against others on their own feet, never once preaches about lying down and taking it easy or playing polite. which was nice to see lol i hate liberals who have morals about property damage but in ayutha ezhuthu, michael clearly doesn’t give a fuck. he and his group break things and smash cars and lorries on their way and threaten physical violence on their opponents too which is the way it should be because to him human lives are worth more than any property or vehicular damage. he never shies away from that. hell yes to violence and structural damage!

probably the most definite trait of michael compared to other suriya leftist characters is that michael still believes in the establishment and electoral politics, which u don’t particularly see his other leftist ones talk about. but here, michael works within the system, and trusts it to bring change if u put in the effort into that. though, it’s not as frustrating as it sounds cos michael’s work is not geared towards other liberals, but in villages and rural districts where he goes to spread word, and makes them choose their own leadership to represent. it’s way more marxist aligned and ~rise of the proletariat~ here instead cos he bypasses liberal bougie nonsense and never once is his voice used for that, but used towards and for the working class directly to both take up arms and resist violently themselves + hold ranks for themselves and choose their own leaders to influence their local politics/protect their environment.

michael is fundamentally very marxist, with a dose of direct action plus violent resistance if need be, and supports organised proletariat uprising within an established political system playing towards electoral politics

(of course, a point to note in why this isn’t as frustrating as it sounds as mentioned above is cos this film was released in 2004. would michael still believe in the establishment and electoral politics now? things in 2020 are very different with all of us more aware of things around us and globally, it’s definitely a debate to be held. i doubt he will, since he’s not a pacifist or liberal. he’d say fuck electoral politics, all my homies hate electoral politics)

2. vimalan (maattraan, 2012)

second very openly communist character he played. prob gone a bit forgotten for others since he does die halfway through the film (which itself isn’t a favourite of anyone either, fans or neutrals) rip but can’t go by without mentioning cos i remember liking this character a lot and i teared up in the cinema first watch when he died. i was mad they killed the suriya i loved instead of the other one whom i found annoying lmao

vimal supports workers’ strikes and unions against bosses, even when that boss is their own shitty father. this automatically makes him stand out instantly considering he is sympathetic to the working class despite at the cost of his father’s annoyance with him. he’s also the first character suriya plays who’s explicitly anti-capitalist with line(s) about it, since michael had no canon lines regarding capitalism from what i recall. vimal outright does.

the leftist imagery tied to vimal the most is che, which is a nice touch. his room has at least one poster of him, and his phone’s wallpaper is also him. u can also see bhagat singh and ho chi minh books on his shelf. so.. safe to claim where vimal’s political ideologies are. it’s both tied in pictures and him siding with workers for their rights against corporations, since he obviously likes revolutionaries. vimalan was a class traitor and a supporter of the working class poor bb tragically gone too soon. ilu u didn’t deserve your terrible fate, sweet commie good boi :(

3. iniyan (thaanaa serndha koottam, 2018)

iniyannnnnn i love him and i think it’s a suriya char with one of the best character arcs in his whole career. mostly cos he had a very distinct ‘’yes i want to work for the government and change things from within’’ phase which gets squashed over the course of the film. we see him start off obviously in a very blatantly communist neighbourhood in a song that is also very specifically anti-establishment/politicians with a lot of hard resistance vibes. the entirety of sodakku is a very good introduction to him and what he stands for - in general the film promises upon wealth disparity, useless bougie politicians, and the rest of us being crushed under them.

what happens to him at the end of the movie is FANTASTIC because he no longer gels with what he wanted at the start of the movie. iniyan’s key leftist trait to me is that he’s the most anarchist of suriya characters, varying from other leftist suriya characters. he refuses to work with government powers and authorities, he looks down on their entire establishment and institutions (he does not at the start of the film, which is vital cos again, he wanted to work alongside them at first), and depends more on the good will of individual people over job titles, while clearly engaging in mutual aid and distributing wealth. these are very distinct anarchist ideals. i’d still peg him as anarcho-communist but would say he leans more towards anarchy and progressing on mutual aid over official state resources or state people for any kind of positive change since his faith in them has pretty much diminished by the climax. he does not give a shit about politicians, cops, or any kind of authorities at all, leaving them in the dust to raise his black flag and do his own anarchist hot shit.

iniyan is a good example of an anarchist arc for me in tamil cinema in simple commercial terms without heading too deep into actual words and phrases in a big hero movie, cos it’s also very easy to explain to anyone the shift in his ideas and his eroding faith in institutions with power. good for him!

4. maara (soorarai pottru, 2020)

this should be fresh in everyone’s memory, but yes, a character who is obviously in your face about it since he has an actual line - ‘’you’re a socialite, i’m a socialist’’ which caused all of us with good taste to whoop and cheer. plus he was very sexy in this whole scene, so what a bonus. it’s the most explicit thing said by him in the film, but there are also other little things peppered into his speech and background imagery showing u the kind of person maara is.

he gets married to bommi in a self-respect wedding ceremony. no priests or any kind of traditional hindu iyers/chants involved. u see it clearly with a periyar pic hanging behind him explaining who he is. he wears black a lot in the film, which fits him being a periyarist so i’d label him as such and consider it his standout trait from other leftist characters suriya has played previously because this is the only character with explicit periyar symbolism (i kid u not i saw multiple sanghis being very angry suriya dressed in black in this movie and were harassing him on twitter constantly since sp released. die mad, uglies). obviously, this also fuses well with the little things we see of him implying he’s ~lower caste~ like his in-laws being embarrassed about him on behalf of their own caste, and paresh sanitising his hands after shaking hands with maara on the plane, which is not subtle at all and trademark casteist behaviour about touching someone ‘’lesser’’ than you and u view them as ‘’dirty’’ or beneath you. as well as maara’s remark about breaking the class and caste barrier during his radio interview. being a periyarist fits seamlessly.

there’s also a bts vid of suriya on his bike where you can see an ambedkar pic pasted onto the side. i can’t remember any scene in the film where u can see his bike from this angle but it doesn’t matter, cos u can definitely tell the kind of person maara is and how he was envisioned as a character - an explicit socialist and periyarist, with a natural fondness for ambedkar too since ofc they overlap as many do irl as well. it is very in tune with his background in the film and i liked seeing the tiny aspects of these things seeded within the movie throughout from beginning to end. it’s explicit in a way that isn’t jarring or artificial, and a nice layer to him and feel endeared to since maara is a great character. u support him all the way with him being unquestionable in his stance and ideology. the sexiest leftist suriya character, if i say so myself, ahem.

/////

5. ngk (ngk, 2019)

bonus: THIS IS IT. THE BIGGEST SIKE. THE BIGGEST WHIPLASH. THE BIGGEST BASTARD.

it’s here cos damn, when they released that first look, i completely lost my shit cos that poster was sooo heavily che inspired and very, very obviously marxist. cue me thinking that holy shit suriya is openly playing some kind of marxist guerilla revolutionary in ngk and he’s gonna be some brand of violent radical leftist i’m gonna fall in love with. the beret, the raised fists, the red.. i was ready to be head over heels for this guy.

except of course, none of this was true, cos once the film released, u know that poster was only meant to signify how his village looked up to him before he sold them all out. it’s literally just a mural on the wall where a kid stares up at him in a larger extended poster. he COULD have been that character, but ngk’s character arc was a negative character arc and his moral downfall from the start to the end of the film, sacrificing all he stood for to arrive at his end point which was just dragging his village and all the youngsters who believed in him to the pits before jumping party to the winning group and abandoning all of them after manipulating them to act in his favour to gain sympathy. not to mention, also selling out to corporate tools to harness their power and influence in order to rise to the top himself, something he very openly states at the beginning of the film to his mum and wife that working like that is no way to live. he has a full reverse by this point, compared to how ngk was introduced to us as an audience with that first look of him.

the marxist poster was a complete 180 to how ngk falls on the spectrum at the end, but it was a great ride nevertheless and at least one thing was still true - i still fell in love with him cos he was such an asshole bastard but still so hot i had to give in. biiiicchh. i love u, non-leftist regressive jerk. u may have pulled the biggest sike on me, but.. my heart is yours, slut <3

*****

ok that’s really it and all i wanted to say so hopefully at least a few people read this lmafooo. i do think these characters and time have sort of seeped into suriya over the years as evident by his shifting left in the last couple of years, and openly also saying he has had a lot of perspective changes on things around him. he has been noted in recent interviews saying stuff like how he’s in favour of a cashless society, talking about a whole new level of poverty class being created during this pandemic. his written articles/statements/agaram related speeches takes jibes at india’s education system being brahministic/casteist in nature and how it creates barriers for the lowest strata of society while also being very sensitive about student suicides, showing understanding of it as a systematic failure and not an individual one, courts not functioning for justice, not demonising protests as it’s the only act left for the voiceless, etc. it’s nice. i wouldn’t go as far as to call him a leftist until he proves that to me (suriya is still very much in that liberal zone of appreciating the police and military institutions so i will never consider him one of us until he sheds these allegiances and rethinks his stance on them in society), but i’d say he’s definitely the furthest left of all prominent actors in tamil cinema as no one else really has said or written the things that he has, for which i’m very proud of him.

so keep up the good work and hot shit comments and ballsy articles, suriya, i look forward to u shifting further left and pissing off everyone from right wing patriotic assholes, to centrist bootlickers, and even cowardly liberal pacifists. i believe in u and i hope he crosses that steep liberal curve soon since we were all there at some point as well.

that’s all goodbye i love suriya thanks for reading

#hooo lads finally wrote this like i wanted to! target audience? spare target audience??#suriya#tamil cinema#kollywood#mix#mine*#commentary#politics

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT SHOULD SOCIALISTS DO ABOUT THE INTERNET?

By Daniel Joseph

Socialists need to seriously contend with the economic and structural role the internet is playing today in our politics and struggles, both here in Canada and around the world.

In October 2016, Breitbart News Network, a far-right political website headed by eventual for-one-year White House Chief Strategist,

Steve Bannon — with close (and publically verified - see Bernstein, [2017]) ties to the white supremacist “alt right” movement — opened an online store to sell branded merchandise. On this store, Breitbart was to sell t-shirts with an assortment of racist dog-whistles and anti- immigration rhetoric celebrating the soon-to- be President Elect’s border wall (Daro, 2016). The functioning of this store was made possible with tools provided to them by Shopify, a Canadian e-commerce company based in Ottawa. Shopify provides the interface, the point-of- sale system, inventory management, and other tools for, typically, small-to-medium-sized businesses whose primary activity is conducted online. Essentially, Shopify functions as an intermediary or middleman for the circulation of capital (which Marx [1893] discusses in detail in Capital, Volume II).

On February 2, 2017 it came to light that behind the scenes at Shopify, numerous employees were “quietly urging” management to end their business relationship with Breitbart (Daro, 2016). Six days later, Shopify’s CEO, Tobias Lütke, published a defence of Shopify’s official stance to continue supplying ecommerce tools for Breitbart. Lütke stated: “products are speech and we are pro-free- speech. This means protecting the right of organizations to use our platform even if they are unpopular or if we disagree with their premise,” (Lütke, 2017).

Shopify, a company whose products usually keep them out of the spotlight, found itself at the centre of a public conflict: employees and critics pointed out that by providing tools for Breitbart, they were implicitly endorsing the hate that Breitbart used to peddle its clickbait articles like t-shirts. Yet according to Lütke’s professed fidelity to an unsophisticated liberalism, a private company had no right to restrict the speech — in this case, the buying and selling of products — of others. This public relations crisis surrounding Shopify and Breitbart is just one example of the increasing conflicts that are made apparent by the growth and increasing monopolistic status of companies that have based their business model on and around the internet.

While this conflict was quickly forgotten in the churn of the news cycle and the eventual election of Donald Trump, I think it illustrates that socialists need to seriously contend with the economic and structural role the internet is playing today in our politics and struggles, both here in Canada and around the world. There are two good reasons for this. The first is that we use the internet to communicate, build solidarity, and organize. It’s a powerful infrastructure that enables all kinds of communication in tangible ways. This is especially apparent when considering the growth of progressive movements around the world, including ours, in the last 10 years. Because we rely on them it is incumbent upon us to understand the history and workings of the technologies we use to build our movement.

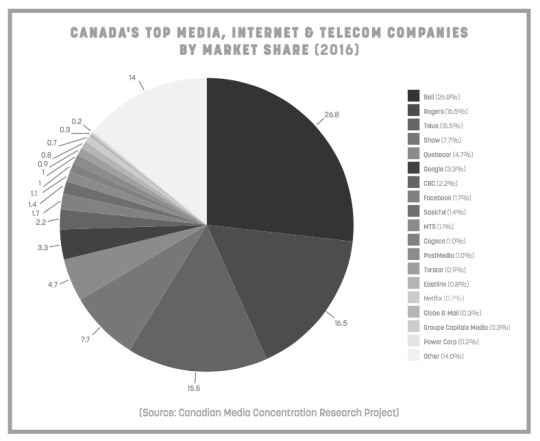

The second reason we should understand the internet is that it’s at the centre of today’s version of monopoly capitalism. While resource extraction, commodity production, and agriculture undergird the majority of global capitalism’s ongoing operation and reproduction, the advanced capitalist countries have simultaneously put the internet at the centre of their economies, rhetorically and literally. It’s not that the biggest companies by revenue will necessarily be companies whose business exists only on the internet. In Canada, for example, the biggest companies remain in the hands of our banks and mining corporations. Instead, it’s that every company, in pursuit of what Marx called “relative surplus value” can’t be competitive without relying heavily on the communication tools provided by internet-based platform owners (such as Facebook, Shopify, Alphabet [formerly Google], etc). The internet is where capitalists go to try to transcend space and time, because if they find the right tool, they will find themselves at the cutting edge faster than their global competitors. If they play their cards right, they will leverage that, gain advantage and possibly even restructure the market.

In academia, one book that addresses this process, Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism (2017), is an important (if limited) look at the growing importance of platforms in the global economy, written from an explicitly Marxist perspective. In it Srnicek describes how businesses on the internet function just like any others: “we can learn a lot about major tech companies by taking them to be economic actors within a capitalist mode of production.”

The argument of the book rests on the economic history of capitalism that is laid out by Robert Brenner (2006) in The Economics of Global Turbulence, which itself was a critique of some of the core arguments in Sweezy and Baran’s (1956) Monopoly Capital. Brenner’s argument is that competition from East Asia, Russia, and Brazil exacerbated the decline in profits for manufacturing in the core capitalist countries. As a result, less and less capital was finding its way into manufacturing, and found itself in need of productive use. So, something we are now very familiar with, it found its way into finance. Part of this move towards finance resulted in the dot com-crash of the late 1990s, as well as the housing bubble of the last decade. It also found its way into companies specializing in business on the internet, many of them promising low fixed capital costs, room for expansion, and high margins.

Srnicek argues that this money-capital, sitting in bank accounts in desperate need of investment is what explains the massive growth of internet-based companies like Alphabet, Microsoft, and Facebook — all successful companies making money from a variety of sources. It also explains the recent growth of other companies, what Srnicek calls “lean platforms”, like Uber or Airbnb: companies that specialize in making themselves the mandatory go-between for the so-called “sharing economy”. From these platforms, Srnicek argues that there are roughly four tendencies for the future of platform capitalism: the expansion of extraction (the intensification of data mining, which is productively sold to advertisers and marketing companies for a profit), a company positioning itself as a gatekeeper (gaining control over vital exchange points for capital and labour), convergence of markets (the tendency for companies in previously different markets to find themselves in competition), and the enclosure of ecosystems (putting users into walled, fully controlled “gardens”, like Apple’s iOS).

It is in this vortex of capital that we currently find ourselves. All the time it feels like platforms and corporations like Facebook, Google, or Apple are what the internet “is”, instead of the network being what provides their infrastructure. There’s also the ever- present and depressing daily pressure on the working class, on our friends and family, to sell off their lives to companies like Uber or Airbnb to cover the crisis of rising fixed living costs like rent.

Srnicek suggests that one possible solution goes beyond state regulation of these technologies: “Rather than just regulating corporate platforms, efforts should be made to create public platforms — platforms owned and controlled by the people” (p. 128). I certainly think that’s a noble goal, and it could be something those advocating for socialism should incorporate into our analysis and policies. Platforms — the places where goods and services are exchanged and where all kinds of communication takes place — can and will be genuinely useful and important technologies for the development of socialism. At the same time, we should also recognize that existing platforms are there to extract data from us and exercise control over us. Platforms shape how we consume, and they function as a propaganda distribution system, while also doubling as a surveillance system for the repressive bourgeois state. It would be a huge misstep to argue that the internet and the technologies it enables are neutral in the class struggle.

If I have an immediate pointed criticism of Srnicek’s case for emancipatory platforms, it’s that there’s no historical discussion of past struggles concerning communication technologies. Communication has been, and continues to be, an important consideration for any revolutionary program for a better world, especially in the multitude of struggles of the twentieth century. There’s a history of Marxist political economy that took imperialism very seriously, and centred on the struggles of people under the thumb of imperialism who attempted to use communications technologies against it. They didn’t hedge their bets by imagining a utopian society: instead they had to start with the state of communication technology at the moment of struggle, and to do what they could at that specific historical juncture.

For example, take what Herbert Schiller and Dallas Smythe wrote in a report titled Chile: An End to Cultural Colonialism while consulting with Armand Mattleart and Salvadore Allende’s Popular Unity coalition in Chile in 1972:

“It seems clear that this gap [between the nationalization of basic infrastructure and the relative free market treatment of the culture industries] will be a site of a coming struggle – a battle for control of the mass media, a battle which the left in Chile is a long way from resolving in a strategy for winning. First they must decide what policies a proto-socialist mass media structure would follow. The problem is incredibly more complex than, say, how to nationalize copper. Among the reasons it is difficult to analyze is that in concentrating its attention on man as affected by his production relations, Marxists have relatively neglected man as affected by his consciousness, his leisure relationships, his cultural relations. It is in analyzing this problem and solving it that Chile has the opportunity to make an historically new contribution to the development of socialism.” (p. 61)

Clearly, the success of the fascist coup that came soon after illustrated that this aspect of the struggle was by no means solved conclusively. It could very well have been fatal.

Applying Schiller and Smythe’s concerns about the complexities of proto-socialist communications systems in a time of struggle and revolution to the internet increases the complexity drastically. The relative decline of broadcasting, the rise of platform owners and software as service companies, the proliferation of intermediaries and our dependence on social media mean that the question extends way beyond the (still very important) questioning of who owns this or that radio tower, TV station, or newspaper chain. Instead, we have to think about what companies, such as Shopify, maintain and profit by maintaining the infrastructure of the internet. Complicating matters for Canadians, very few of these organizations are based in Canada. Our local media monopolies like Rogers and Shaw own the physical infrastructure that allows us to access the internet, but in the end most of us rely on Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Netflix and dozens of other US-based platform owners to filter, organize, secure, and regulate our communication. I don’t have an answer to these problems. The only way we will get to them, however is by our analysis taking them into account. It’s important to not put the cart before the horse. Start with things as they are, and then go from there. If this is the case, it’s doubtful that any of the existing platforms could in practice be nationalized, much less used to build socialism. Whatever comes next will have to be built anew, conditions permitting.

We need answers because in the meantime those advocating for a socialist future are sadly tied to media platforms with no meaningful democratic accountability, despite being considered by liberals as the guardians of a democratic discourse. For example, there was Facebook’s January 2018 change to its news feed towards personal items, which was, by their account, designed to encourage what they describe as “meaningful interactions”. In other words, the one platform that is most relied on for news is shifting its focus away from news. Facebook justified this choice partly on psychological research they had conducted about what kind of posts they thought people wanted to interact with. The place where the majority of people get their news was fundamentally changed, with no democratic input, entirely on the basis of what Facebook thought would increase their bottom line.

Hanging over the corporation, and much discussed, was also the moral panic surrounding state-sponsored Russian “fake news” proliferating through Facebook, and presumably swinging undecided voters towards Donald Trump. No doubt by shifting focus towards social interaction with no news content, Facebook can safely tell their lobbyists to assuage the hypocritical liberal Russophobia and paranoid concerns of their political benefactors. Justin Trudeau’s meeting with Sheryl Sandburg, Facebook’s Chief Operating

Officer, was clearly related to such public relations concerns about possible government regulation of advertising and news distribution.

At the same time, we know from past efforts that Facebook’s tackling the “fake news” problem is likely to target both reactionary right-wing news outlets, and also, though, critical, progressive and explicitly socialist outlets. Not long ago, Facebook sounded like Shopify’s Tobais Lutke, professing a maximalist liberal conception of the neutrality of platforms towards content in “the marketplace of ideas”. Now Facebook has stated that they do, in fact, have an opinion about what qualifies as “real” journalism. Anybody who understands the history of how media monopolies function and what their actual goal is (to collect and sell audiences to advertisers and collect subscriptions) knows that the kind of journalism they will protect will be that which stands up for, and protects the bourgeois state and order of things.

It’s up to us as socialists to keep challenging this narrative, and keep a critical eye on the internet in general.

REFERENCES

Baran, P. A., & Sweezy, P. (1966). Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order (1st Modern reader paperback ed edition). New York: Monthly Review Press.

Bernstein, J. (n.d.). Here’s How Breitbart And Milo Smuggled Nazi and White Nationalist Ideas Into The Mainstream. Retrieved October 14, 2017, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/josephbernstein/heres-how-breitbart-and-milo- smuggled-white-nationalism

Brenner, R. (2006). The Economics of Global Turbulence (1st edition). London ; New York: Verso.

Daro, I. N. (2017, February 2). Shopify Employees Want The Company To Stop Doing Business With Breitbart. Retrieved September 5, 2017, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/ishmaeldaro/shopify-breitbart-store

Farnsworth, M. (2018, February 9). Watch the interview: Facebook’s heads of News Feed and news partnerships. Retrieved February 13, 2018, from https://www.recode.net/2018/2/9/16996696/how-to-watch-livestream- facebook-head-of-news-feed-partnerships-campbell-brown-adam-mosseri

Marx, K. (1893). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. (F. Engels, Ed.) (Vol. 2). Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Schiller, H., & Smythe, D. (1972). Chile: An End to Cultural Colonialism. Society, 9(5), 35–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF02697609

Daniel Joseph is a political economist and freelance writer researching digital distribution platforms, games, and labour.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Talk I gave on the “Day without a woman”

On January 20th 2017, as I am sure all of you know, Donald J Trump was inaugurated president of the United States. Since then the American political community has been in disarray on how to respond to this sexist, racist, enemy of the working class seated in the white house.

The very next day on January 21st 2017 as you also know, the nation was shocked at the magnitude of the said response. Over four million people at 915 women’s marches organized worldwide stood up to reject Donald trump’s brand of Right wing populism and all that it entailed

Criticism of the Women’s march was swift. Pundits from the right raged that the march had no message, and no political content. They decried the fact that marches were largest in cities that Clinton took by huge margins, not surprising considering that these cities had been disenfranchised during the election by the racist electoral college system. Meanwhile on the liberal “left” they argued that it was an outpouring from privileged white women who only now had begun to feel the heat of American neo-liberalism that had been destroying marginalized communities for decades. However, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writing for the Socialist Worker counselled that the marches were “the beginning, not the end” of resistance to Trump and this certainly proved to be true.

In the following weeks, Trump has landed one metaphorical blow after another with relatively little resistance from elected democratic party lawmakers. He successfully appointed an oil baron, war-criminal and enemy of public schools to his cabinet, revived both the Dakota Acess and Keystone XL pipelines, moved to hire 5,000 additional Border Patrol agents & 10,000 additional immigration officers, prioritized the deportation of millions more undocumented immigrants included those who have only been accused of crimes, all but ended Obama’s limited refugee program, Suspended the entry of all “immigrants and nonimmigrants” from Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Yemen, Somalia and Syria, Ended protections for Trans students in the public school system and more.

These actions horrified many, and have lead the resistance to Trump into an explosion of frantic marches and resistance action often announced days before they take place allowing little time for organization, which has lead to varying degrees of sucess. In response to the renewed DAPL threat encampments grew again in Standing Rock before being effectively destroyed five days ago by police and federal agents working in tandem. In response to the immigration executive order, nationwide protests at airports forced a judge to temporarily halt the action and eventually it was struck down by an appellate court pending appeal or revision. In response to Trump’s actions on undocumented immigrants, a national “day without immigrants” was organized.

This demonstration, its name a reference to the highly successful 2006 demonstration of the same name, was a call for a “General strike” of immigrants with the end goal being a show of force against the Trump administration of the economic power of immigrant workers. There is some confusion surrounding this idea of a “General Strike”. So, what is a General Strike? Broadly it is when a large group of workers across trades and traditional boundaries strike together. There are many reasons to do this from demanding better treatment from bosses such as the 1892 New Orleans general strike where a striking group of both black and white workers forced New Orlean’s board of trade to grant them 10-hour day and overtime pay to making a political stance. Traditionally such efforts have been associated with the labor movement. Unfortunately, the recent general strikes have not involved any real attachment to trade unionism due to the crack down on the trade-unionist left in this country in the late 70s. Without the organisation that unions provide, the “day without immigrants” ended up being more of a symbolic sporadic strike that resulted in at least 100 workers being fired.

This brings us to the current topic at hand. The organizers of the Women’s March have come forward with a new demonstration. “A day without women” A women’s general strike to be held on International Women’s Day. There is however, a fundamental difference between this call to action and previous poorly organized general strikes. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor put it “there is another history of a ‘women's strike’ that is intended to call attention to the unpaid and often overlooked contributions of women's labor”

To quote the organizers of the event themselves: “The goal is to highlight the economic power and significance that women have in the US and global economies, while calling attention to the economic injustices women and gender nonconforming people continue to face.” As Marxists we are part of a radical tradition that has stood for the liberation of women against this very power imbalance from the beginning. In Friedrich Engels’ 1884 Tour de force “The origin of the family, private property, and the state” the Marxist critique of patriarchy was centered squarely on the institution of the family for, as Engels points out,

“With the single monogamous family, a change came. Household management lost its public character. It no longer concerned society. It became a Private Service; the wife became the head servant, excluded from all participation in social production. Not until the coming of modern large-scale industry was the road to social production opened to her again—and then only to the proletarian wife. But it was opened in such a manner that, if she carries out her duties in the private service of her family, she remains excluded from public production and unable to earn; if she wants to take part in public production and earn independently, she cannot carry out family duties.”

Thus, the women’s role in the family confers upon her work that is not valued by society as actual work but merely as chores that women are required to fulfil ONTOP of any other work that they might undertake for a wage. What’s more, this arrangement also allows for the capitalist class to pay much less for many public services like child care, education and health care as much of those costs are passed on to the woman in her role in the family.

Engels goes on to say that this gives men a “position of supremacy” over women “without need for special legal titles” This in and of itself gives rise to the patriarchal nature of society as the subjugated position of women gives proof to the sexist argument that it is in “women’s nature” to be subjugated leading to the rise of the system of patriarchal oppression.

Thus, by stepping back and refusing to do work, women make a profound statement that it is valuable regardless of its social standing or its status as unpaid under the capitalist system. This statement is a break with the earlier criticism of the women’s march as it lends the women’s strike a deep political message. Highlighting how the capitalist system strengthens and defends social hierarchies such as patriarchy.

Lenin, who had nothing but disdain for those who cared only about class struggle and no other forms of oppression, took Engels’ Critique of the family one step further when he said that

“We… hate everything, and will abolish everything which tortures and oppresses the woman worker, the housewife, the peasant woman, the wife of the petty trader, yes, and in many cases the women of the possessing classes. The rights and social regulations which we demand for women from bourgeois society show that we understand the position and interests of women... Not of course, as the reformists do, lulling them to inaction and keeping them in leading strings… but as revolutionaries who call upon the women to work as equals in transforming the old economy and ideology.”

Thus he decried not just the patriarchal oppression of proletarian women but of all women it is in this spirit that we must avoid dismissing these demonstrations as merely outlets for privileged bourgeois women and build a revolutionary organization truly dedicated to the liberation of all oppressed peoples.

#revolution#lenin#engels#marxism#day without a woman#womans march#iso#speeching#my writing#feminism#marxist feminism#materialism#politics#strikes#trade unionism#us#american politics#international socialist organization#socialist worker

1 note

·

View note

Text

Between Levinas and Lacan: Self, Other, Ethics - Mari Ruti

Preface

vii

This book charts the ethical terrain between Levinasian phenomenology and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

If Levinas views the other as a site of unconditional ethical accountability, Lacan is interested in the subject’s capacity to dissociate itself from the (often coercive) desire of the other— whether the big Other of symbolic law or more particular others who, for the subject, embody this law.

[W]hile Levinas laments our failure to adequately meet the ethical demand arising from the other, Lacan laments the consequences of our failure to adequately escape the normative forms this demand frequently takes.

This explains why Lacan does not join Levinas in celebrating the inviolability of the other but instead seeks to rupture the unconscious fantasies that render us overly compliant with respect to the other’s desire; it explains why Lacanian ethics sometimes sounds like a mockery of everything that Levinas stands for.

viii

Undoubtedly, the Levinasian approach speaks more easily to our everyday notion of ethics in the sense that we are used to thinking that we should respect the other regardless of how confusing or repellent she may seem. This stance in fact —explicitly or implicitly— underpins many of the difference-based ethical paradigms of contemporary theory. And it has generated one of the most powerful ethical visions of the last decade: Judith Butler’s ethics of precarity as an ethics that posits shared human vulnerability—our primordial exposure to others—as an ontological foundation for global justice.

Žižek has theorized the so-called Lacanian “act” —a destructive or even suicidal act that allows the subject to sever its ties with the surrounding social fabric— as a countercultural intervention with potentially far-reaching ethical and political consequences. Badiou, in turn, has explained how the truth-event (a sudden revelation of a hitherto invisible truth) can compel the subject to revise its entire mode of being despite the potentially high social cost of doing so. In other words, if for Levinas and Butler, ethics is a matter of recognizing the primacy of the other, for Lacan, Žižek, and Badiou, it is a matter of a profound reconfiguration of subjectivity — of the kind of realignment of priorities that makes it impossible for the subject to stay on the path that it has, consciously or unconsciously, chosen for itself (and that others may expect it to follow).

However, this quest should not be confused with the attempt to revive the universalism of Western metaphysics, for if Levinas, Butler, Lacan, Žižek, and Badiou have one thing in common, it is their rejection of the sovereign Enlightenment subject, which means that the universalism they advocate cannot be based on principles such as rationality or autonomy but must, instead, seek alternative forms of legitimation. For Levinas and Butler, it is the subject’s relational ontology that offers such legitimation: insofar as the subject owes its very existence to the other, its responsibility to the other is non-negotiable and without exception. Žižek and Badiou, in turn, maintain that even though the act or the event always arises from a specific situation, and even though it annihilates the subject’s fantasies of rational self-mastery, the illumination it provides strikes the subject with the force of a universal truth (which is precisely why it cannot be ignored).

How do we meet the suffering of others without reducing them to objects of our pity? Does ethics arise from the vulnerable face of the other, as it does in Levinas?

X

Her ethics of precarity, I will illustrate, cannot work without a grounding in a generalizable ontology of human vulnerability, with the result that her efforts to downplay its universality ring false.

Simply put, I wish to ask why autonomy is such a red flag for Butler despite the fact that most of the world’s population is arguably not suffering from an excess of smug confidence. If, as Butler herself repeatedly reminds us, we are precarious and broken, why insist on breaking us more?

xi

At the same time, Levinas draws a clear distinction between ethics (where normative considerations have no place) and justice (which arbitrates between individuals on the basis of a priori norms of right and wrong), thereby suggesting that justice curtails our ethical accountability.

xii

Yet I also question Butler’s conviction that grief serves as a basis for ethical and political accountability, for it seems to me that grief could just as well have the opposite effect of paralyzing action. Even more insidiously, the emphasis on grief could make relatively privileged Western subjects feel like they are accomplishing something —working for social justice— when in fact nothing is changing in the world; the notion that there is something inherently “decent” about grief could make it too easy for Westerners to feel so good about their “virtuous” capacity to mourn the losses of the rest of the world that they (conveniently) cease to feel any urgency about doing anything else.

Essentially, Žižek and Badiou believe that when we choose to define the human being as a victim, we foreclose the possibility of the kinds of courageous acts (or events) that disturb the status quo of the hegemonic cultural order and that, potentially at least, allow new social configurations, including more just collective arrangements, to come into being.

Žižek and Badiou themselves advocate a more radical approach, arguing that it is only when the subject risks its ordinary way of being (including, perhaps, its grief) that it becomes a “real” subject— a subject with agency and thus the capacity for ethical and political action.

Chapter 3

The Lacanian rebuttal: Žižek, Badiou, and Revolutionary Politics

77

[Butler’s] last book, although it does not mention Badiou, is de facto a kind of anti-Badiou manifesto: hers is an ethics of finitude, of making a virtue out of our very weakness, in other words, of elevating into the highest ethical value the respect for our very inability to act with full responsibility.

At the same time, I have expressed my reservations about the masochistic, disempowering tendencies of both Levinasian and Butlerian ethics, and these reservations are what steer me to the more rebellious Marxist-Lacanian ethical paradigms of Žižek and Badiou.

79

What I mean by this will become clear as my discussion progresses, but let me say right away that this basic Lacanian stance manifests itself in the theories of Žižek and Badiou as the conviction that the point of ethics is not to fixate on our entrapment in hegemonic power but, rather, to make the impossible possible. In other words, if Butler tends to underscore the impossibility of breaking our psychic attachment to wounding forms of social power, Žižek and Badiou insist on our ability to do precisely this.

81

While there may be some truth to this claim, it also overstates the issue because, as I explained in Chapter 1, Levinas does not actually depict the face as a locus of straightforward identification. Rather, he describes it as “a being beyond all attributes” (EN 33), as what escapes the kinds of conceptual and perceptual categories that would allow us to reduce it to what is familiar to us. The face is a site of utter singularity, of utter self-sameness, which means that it by definition defeats our attempts to classify it. Consequently, far from facilitating immediate empathy, the face alerts us to the limits of empathetic affinity, which is exactly why it elicits unqualified responsibility — why, in Levinasian terms, we are supposed to protect the other regardless of how this other appears to us, regardless of whether or not we experience the other’s face as benevolent.

[L]ike Badiou, Žižek wishes to demonstrate that multiculturalism works only as long as the other is someone with whom we can identify (and let us not forget that Butler’s ethics of precarity calls for exactly this type of identificatory capacity); Žižek reminds us that multiculturalism makes sense as long as the other possesses qualities, ideals, or values we can relate to but that matters become complicated when the other no longer makes any sense to us, when the other is, say, a suicide bomber who does not hesitate to kill random civilians for the sake of his or her cause.

82

We have in fact had to confront the problematic Badiou highlights, namely that despite our rhetoric of respecting differences, it is difficult for us to respect those who refuse to respect differences.

Are there not situations where the Levinasian respect for the face is overrated and it would be better to heed Žižek’s call to smash the other’s face (N 142)?

This is why the Butlerian solution is to humanize those faces that have been deprived of their human resonance by both global and more local structures of power. Žižek’s strategy is the exact opposite in the sense that justice, in his opinion, calls for a radical dehumanization of the subject—a move away from the face.

83

In other words, justice begins when I recall the distant multitude that eludes my relational grasp.

Along related lines, Badiou asserts that it is not respect for differences but rather a kind of studied indifference to them that founds ethics.

What we have here is a clash between the Levinasians and the Lacanians, the defenders of the face and those who see the aesthetics of the face as a decoy that distracts us from impartial justice.

84

But what most interests me is that, despite their obvious disagreements, both sides of the clash, in this particular instance at least, seem to be on a quest for a universal foundation for ethics.[BÖ1] After all, whether we are looking to make every face count equally, or to studiously ignore every face, we are striving for a general principle that levels distinctions between individuals; we are trying, in our divergent ways, to say that either everyone matters or no one does.

86

My main point is that the post-metaphysical critics I have chosen to analyze in detail are all, in one way or another, willingly or not, attracted to the idea that there might be a way to theorize a universalist ethics even in the absence of the sovereign humanist subject[BÖ2] . However, where they diverge is in how they conceptualize the relationship between the singular and the universal.

86

Žižek and Badiou, in contrast, see no contradiction between singularity and universality; as their statements about the “coldness” of justice (Žižek) and the “indifference” of ethics (Badiou) indicate, they believe that the universal can, potentially at least, accommodate a multitude of singularities.

Žižek and Badiou take it for granted that every singularity can claim an immediate membership in the universal.[BÖ3]

87

In practice, this means that women have always had trouble transcending their coding as female first, human second; blacks have always had trouble transcending their coding as “colored” first, human second; gays have always had trouble transcending their coding as “deviants” first, human second; non-Westerners have always had trouble transcending their coding as “other” first, human second, and so on. This is the dynamic that Žižek and Badiou ignore in their wholesale rejection of all “identitarian,” group-based political movements, such as feminism, antiracism, queer solidarity, and anticolonial struggles.[BÖ4]

The reason they want to go directly from the singular to the universal[BÖ5] is that they see the identitarian focus on particular identity categories such as race, gender, sexuality, religion, and nationality as a “reactionary” political stance (PP 75 ) — one that at best traps individuals in narrow and self-serving preoccupations, and at worst leads to the extreme violence of nationalist uprisings, ethnic cleansings, and religious fundamentalisms. However, Žižek and Badiou do not adequately distinguish between different identitarian movements, so it becomes difficult to see the difference between the Civil Rights movement and National Socialism.[BÖ6]

89

By this I do not mean to suggest that feminism is more important than class politics —not at all— for what most bothers me about the approach of Žižek and Badiou is precisely that they engage in such a counterproductive ranking of political causes. And, unfortunately, their efforts to elevate the class struggle over all other political struggles[BÖ7] give the impression that what is, in the final analysis, at stake for them is an old-fashioned Marxism that seeks “universal” emancipation for white men while being entirely willing to leave everyone else behind.

Interestingly, this is exactly the complaint leveled against Žižek by Laclau, who notes the same problem I have just outlined, namely that the idea that the class struggle is somehow more intrinsically universal than other political struggles, such as multiculturalism, is based on a spurious ranking of political causes.

In Laclau’s opinion, not only is it possible to demonstrate the potentially universalist appeal of the causes that Žižek labels “identitarian,” or “particularist,” but it is also possible to show that the class struggle is no less identitarian than any other struggle, centered as it is on the worker’s self-understanding of himself as having a particular identity—an identity that can be undermined in various ways. The class struggle, on this view, arises when the worker feels that his identity is somehow threatened, for instance, when he fears that below a certain level of wages, he cannot live a decent life. As a result, Laclau declares that his “answer to Žižek’s dichotomy between class struggle and identity politics is that class struggle is just one species of identity politics, and one which is becoming less and less important in the world in which we live.”[BÖ8]

95

Žižek’s dismissal of the ways in which the particularity of subject positions continues to matter cannot be divorced from his resistance to defining the human being as a victim — a resistance that he shares with Badiou. In other words, what creates a chasm between Butler in the Levinasian camp on the one hand and Žižek and Badiou in the Lacanian camp on the other is the latter’s rejection of the premise of constitutive precariousness, the very premise that is central to Butlerian ethics.

96

[T]hrough Badiou’s argument that to equate the human with the victim —to reduce the human being to the fragility of his constitution— is to deny the rights of the “immortal.”

Perhaps most important, the truth-event represents an ethical opportunity that allows the subject to pierce the canvas of the established order of things so as to identify what Badiou calls “the void” of the situation.

97

In unveiling the void of a given situation, the truth-event creates an ethical opening, an opportunity to see and do things differently.

In Lacanian terms, Nazism did not disturb “the fundamental fantasy” of a world without social antagonisms but merely avoided confrontation with such antagonisms by displacing them onto the figure of the Jew, which it, then, sought to destroy in order to eradicate the specter of collective rifts as such.

As Žižek specifies, the inauthentic event “legitimizes itself through reference to the point of substantial fullness of a given constellation (on the political terrain: Race, True Religion, Nation . . .): it aims precisely at obliterating the last traces of the ‘symptomal torsion’ which disturbs the balance of that constellation” (“CS” 125).

98

Badiou believes that when we categorize the human as a victim, we effectively shut down the possibility of authentic events: we make it impossible for new ways of interpreting things to enter the world. We, as it were, sacrifice the rights of the immortal for those of the mortal, denying that it is only as something “other than a victim,” something “other” than a mortal being, that man accedes to the status of ethical subjectivity. This is why Badiou concludes that defining man as a victim only ensures that he will “be held in contempt” (E 12). Badiou further asserts that the victim, in the Western imagination, tends to be associated with the disempowered postcolonial subject, so that behind the Levinasian outlook that underscores our responsibility for the (suffering) other hides “the good-Man, the white-Man” (E 13).

What is awkward about Badiou’s formulation is its implication that victimization is something that can be avoided or rejected at will. It may be that Badiou does not mean to vilify the victimized themselves but merely ethical models —such as that of Levinas— centered around the notion of victimization. But this distinction is not always easy to uphold, with the result that Badiou at times sounds as if he thought that some people “allow” themselves to be victimized, whereas others (those capable of truth-events, those we admire rather than hold in contempt) are heroic enough to resist it.

The problem is akin to the one I noted above with regard to Badiou and Žižek’s assumption that every singularity has equal access to the universal.

0 notes

Text

Why Historical Figures Always Had One Hand in Their Jackets

Everett Historical/Shutterstock

If you peruse portraits and photographs of notable men from the 18th and 19th centuries, you might notice that many of them sport the same fairly unnatural-looking pose. They sit or stand while keeping one hand tucked into the front of their jackets. They look like they’re trying to appear stately for the picture while also trying to keep the painter from pick-pocketing their wallet. With depictions of everyone from Napoleon to Joseph Stalin using the gesture, historians and curious art aficionados have puzzled over its meaning. Get a look at some rarely seen historical photos you won’t find in textbooks.

No, it’s not a secret Masonic code or a reference to an Illuminati ritual. The tradition actually dates back long before the 1700s. According to Today I Found Out, some societal circles in ancient Greece considered it disrespectful to speak with your hands outside of your clothing. Statuary from the sixth century BC, therefore, showed celebrated orators such as Solon with their hands tucked into their cloaks.

Little did the ancient Greeks know that their legacy would carry on a whopping 24 centuries later. In the 18th century, artists began looking to antiquity for inspiration. What did they find but statues of celebrated speakers, posed with their hands in their cloaks. Portraitists began representing subjects in a similar pose, believing that it conveyed a noble, calm comportment and good breeding.

One of the most recognizable historical figures to be depicted in this pose was Napoleon Bonaparte himself. Several portraits of the French emperor show him with one hand in his jacket, leading theorists to wonder if he was clutching a painful stomach ulcer. One painter, Thomas Hudson, painted so many men in this pose that his contemporaries wondered if he simply wasn’t good at painting hands.

With the advent of photography in the early 19th century, the trend continued. Major historical figures—everyone from U.S. president Franklin Pierce to Communist Manifesto author Karl Marx—were photographed with unbuttoned jackets and hidden hands. It wasn’t until the end of the 1800s that the pose’s prevalence began to decline. But, even after that, it popped up in photographs every now and then; Joseph Stalin adopted the stance in a 1948 photo. Next, see if you can identify these historical figures from only one image.

10 Historical Figures You’ve Been Picturing All Wrong

Buddha

Norbert Eisele-Hein/imageBROKER/REX/Shutterstock You’ve likely seen fat, smiling “Buddha” statues in Chinese restaurants, antique stores, or gardens, but did you know that little guy is not actually the “real” Buddha? It’s actually Budai, the “laughing Buddha,” who is a reincarnation of the “real” Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. The “real” Buddha was actually thin, because in the Buddhist tradition, once you’ve become “enlightened,” you no longer crave the pleasures of the world. Gautama spent half of his life in wealth and half in poverty, in order to find the ideal balance. His philosophy became the modern Buddhist religion.

Pocahontas

Universal History Archive/UIG/REX/Shutterstock Thanks to Disney, Pocahontas is perhaps the world’s most misunderstood historical figure. She was born in 1596 under the name Ammonite (she also had the more private name Matoaka), and the name Pocahontas was actually her nickname. When the Europeans came to colonize the Powhatan land, Pocahontas did not turn her back on her family to join the European crusade. She occasionally brought food to the settlers to ease tensions between the two peoples, and was later imprisoned by the Europeans and converted to Christianity. Contrary to popular belief, Pocahontas did not marry John Smith––she actually married a tobacco farmer named John Rolfe. She died in 1617 from an illness, but was instrumental in attempting to make peace between the Powhatan people and the Europeans. Learn more fascinating facts about America that your history teacher didn’t tell you.

Che Guevara

ShutterstockThe charismatic Marxist revolutionary, who helped overthrow the Cuban government with the Castro brothers, is often seen as just that. He is seen by some as inspirational and by others insufferable. However, while most people are aware of his rebellion and passion for the counterculture, they don’t know that he was also a ruthless executioner. He oversaw the executions of hundreds of men in Cuba during the early days of Fidel Castro’s government. Feeling like everything you thought you knew has been debunked? Find out the 16 history questions everyone gets wrong.

Oliver Cromwell

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/REX/ShutterstockCromwell was Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the mid-1600s. In 1653 he declared the Parliament corrupt and got rid of them by force; many saw him as a hero for this. Afterward, he became the Lord Protector. But what many don’t know is that Cromwell actually was involved in Irish massacres in a move to help the English gain control of the country. So, while many have seen him as a hero for destroying the corrupt Parliament, he was actually pretty corrupt himself.

Cleopatra

Historia/ShutterstockCleopatra is widely known for her beauty and sex appeal. However, she was the last Pharaoh of ancient Egypt. She began ruling with her father, but later was the sole ruler… of an entire empire! That’s not a simple feat. Most people reduce her to her looks, especially because of her relations with Caesar and Mark Antony, despite her powerful reign. Check out the 12 historical predictions that totally, completely missed the mark.

Alexander Graham Bell

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/REX/ShutterstockAlexander Graham Bell. who is recognized as the inventor of the telephone, is actually a phone-y (pun intended!). The actual inventor was an Italian living in New York named Antonio Meucci. He invented a functioning telephone five years before Bell, and filled out a “patent caveat,” which is a precursor to a real patent. As the story goes, Meucci couldn’t afford to file the official patent, and Bell stole it right under his nose.

Pontius Pilate

Historia/REX/ShutterstockPilate is typically known as the ruler who joyfully ordered the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, but that may be a myth. While Pilate was certainly a harsh ruler, some historians suggest that Pilate was reluctant to crucify Jesus and believed he was innocent. Check out the messed-up history facts you definitely didn’t learn in school.

Vincent Van Gogh

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/REX/ShutterstockThe “Starry Night” painter we know and love actually fits the “tortured artist” persona, despite many of his bright paintings. Van Gogh suffered from depression and lived in poverty—he was an unknown and unloved artist in his time. Even though he had over 2,000 paintings which now sell for millions of dollars, he only sold one in his lifetime.

Confucius

Historia/REX/ShutterstockConfucius is typically regarded as a religious figure. The founder of the Chinese philosophy of Confucianism, Confucius actually had nothing to do with religion. The traditions of Confucianism were based on typical Chinese beliefs and morals: family, respect for elders, and the rights of others. While many people associate these morals with religions, Confucianism is known as a philosophy––no deity involved. Confucius was just the teacher and politician that became recognized by the Chinese government for his principles. Find out the 10 famous people that may have never actually existed.

Christopher Columbus