#alex tizon

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Image in discussion: The New Yorker's newest cover image, which pictures two women of color (it is assumed they are nannies) taking care of white children in a playground.

Recommended Literature: Disposable Domestics (Immigrant Women Workers in the Global Economy), by professor Grace Chang

Tangentially Related Reading: Alex Tizon's Atlantic Article titled "My Family's Slave" (+ my own recommended accompanied reading, "Survivors Respond to 'My Family's Slave'")

Reminder to non-Filipino readers of "My Family's Slave", especially if you are European/American: Do not try to Westernjack the conversation. Do not simplify. Acknowledge the international privilege that amplifies your voice by simple fact of your citizenship (built up by the colonial powers that still command the cultural/economic/military force it does today).

#signal boost#the new yorker#human rights#twitter#history#economic inequality#tw abuse#immigration#migrant rights#modern slavery#listen to survivors of trafficking

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

私の家族の奴隷 My Family’s Slave/Alex Tizon

遺灰は、トースターくらいの大きさの箱に収まった。プラスチック製の黒い箱で、重さは1kg半。それをトートバッグに入れてスーツケースにしまい、マニラ行きの飛行機に乗って太平洋を横断したのは2016年7月のことだ。

マニラに降り立つと、車で田舎の村へと向かう。到着したら、私の家で奴隷とし��56年間を過ごした女性の遺灰を受け渡すことになっている。

彼女の名前は、エウドシア・トマス・プリド。私たちは、彼女を「ロラ」と呼んでいた。背は150cmで、肌はチョコレート色だった。アーモンドの形をしたロラの目が、私の目をのぞきこんでいるのが人生最初の記憶だ。

祖父が私の母にロラを“贈り物”として与えたとき、ロラは18歳だった。そして、家族が米国に移住したとき、彼女も一緒に連れていった。

ロラが送った人生を言い表すのに、「奴隷」という言葉以外には見つからない。彼女の1日は、ほかのみんなが起きる前に始まり、誰もが寝静まったあとに終わった。1日3食を用意し、家を掃除し、私の両親に仕え、私を含め5人の兄妹の世話をした。

両親が彼女に給料を与えることは1度もなく、常に叱りつけていた。鉄の鎖につながれていたわけではないけれど、そうされていたのも同然だった。夜中、トイレに行きたくなって目が覚めて、彼女が家の片隅で眠り込んでいるのを見つけたのは1度や2度の話ではない。洗濯物の山にもたれかかり、畳んでいる途中の服をしっかり握りながら──。

米国では、私たちは模範的な移民家族だった。みんなにそう言われた。父は法律の学位を持っていたし、母は医者になろうとしていた。それに私たち兄妹は成績が良く、礼儀正しい子供たちだった。

だが、家の外でロラの話をすることはなかった。それは、私たちが「どういう存在であるか」という根幹の部分に関わる秘密だったからだ。さらに、少なくとも子供たちにとっては、「どういう存在になりたいか」という問題に深く関係していた。

娘に「奴隷」をプレゼント

マニラに到着して預けた荷物を引き取ると、スーツケースを開き、ちゃんとロラの遺灰があることを確認した。外へ出ると、懐かしい匂いがした。排気ガスやゴミ、海や甘い果物、そして人間の汗が入り混じった濃い匂いだ。

翌朝早く、私は愛想の良い中年の運転手を見つけて出発��た。「ドゥーズ」というニックネームだった。彼のトラックは、車のあいだをすいすいと通り抜けていく。

何度見ても衝撃を受ける光景が広がっていた。おびただしい��の車やバイク、そして乗り合いタクシー。まるで雄大な茶色い川のように、そのあいだをすり抜け、歩道を進む人々。車の横を小走りする裸足の物売りたちが、タバコや咳止めドロップの袋を売り歩く。物乞いの子供たちが、窓に顔を押しつける。

ドゥーズと私が向かっていたのは、ロラの物語が始まったタルラック州だ。また、そこは私の祖父トマス・アスンシオンという陸軍中尉の故郷でもある。家族によれば、土地をたくさん所有していたのにお金はなく、所有地の別々の家に愛人たちをそれぞれ住まわせていた。妻は、初めてのお産で命を落とした。そのときに生まれたのが私の母だ。母は「ウトゥサン」たちに育てられた。要するに、「命令される人々」だ。

フィリピン諸島における奴隷の歴史は長い。スペインに征服される前、島民たちはほかの島から連れてきた人々を奴隷にした。主に戦争の捕虜や犯罪人、債務者などだ。奴隷にはさまざまな形態があった。手柄を挙げれば自由を勝ち取ることができる戦士もいれば、財産として売り買いされたり交換されたりする召使いもいたという。

地位の高い奴隷は地位の低い奴隷を所有することができたし、地位の低い奴隷は最底辺の奴隷を所有することができた。生き延びるために自ら奴隷となる人もいた。労働の対価に食料や寝床が与えられるし、保護してもらえるからだ。

16世紀にスペイン人が到来すると、彼らは島民を奴隷にし、のちにアフリカやインドの奴隷を連れてきた。その後、スペイン王室は自国や植民地で奴隷を段階的に廃止していったが、フィリピンはあまりに遠く離れていたので、監視の目が行き届かなかったという。

1898年に米国がフィリピンを獲得してからも、隠れた形で伝統は残った。現在でも、貧困層でさえ「ウトゥサン」や「カトゥロング(ヘルパー)」、「カサンバハイ(メイド)」を持つことができる。自分より貧しい人がいる限りはそれが可能であり、下には下がいるものなのだ。

祖父は、多いときで3家族のウトゥサンを自分の土地に住まわせていた。フィリピンが日本の占領下にあった1943年春、彼は近くの村に住む少女を連れて帰ってきた。

彼のいとこで、米農家の娘だった。祖父は狡猾だった。この少女は一文無しで、教育を受けていなかったし、従順に見えた。さらに彼女の両親は、2倍も年の離れた養豚家と結婚させようとしていた。彼女はどうしようもなく不幸だったが、ほかに行くあてがなかった。そこで、祖父は彼女にある提案をした。 12歳になった���かりの娘の世話をしてくれるなら、食料と住まいを与えよう──。

彼女、つまりロラ��承諾した。ただ、死ぬまでずっとだとは思っていなかった。

「彼女はおまえへのプレゼントだ」と、祖父は私の母に告げた。

「いらない」と母は答えた。だが、受け入れるしかないのはわかっていた。やがて陸軍中尉だった祖父は日本との戦いへ赴き、田舎の老朽化した家で、母はロラと2人きりになった。ロラは母に食べさせ、身づくろいをしてやった。市場へ出かけるときは、傘をさして母を太陽から守った。犬にエサをやり、床掃除をして、川で手洗いした洗濯物を畳んだ。そして、夜になると母のベッドの端に座り、眠りにつくまでうちわで扇いだ。

戦争中のある日、帰宅した祖父が、母のついた嘘を問い詰めた。絶対に言葉を交わしてはいけない男の子について、何らかの嘘をついたらしい。激高した祖父は、「テーブルのところに立て」と母に命じた。

母はロラと一緒に、部屋の隅で縮こまった。そして震える声で、「ロラが代わりに罰を受ける」と父に告げたのだ。ロラはすがるような目で母を見ると、何も言わずにダイニングテーブルへ向かい、その端を握った。祖父はベルトを振り上げ、12発ロラを打った。打ち下ろすたびに、「俺に」「決して」「嘘を」「つくな」「俺に」「決して」「嘘を」「つくな」と吠えた。ロラはひとことも発さなかった。

のちに母がこの話をしたとき、あまりの理不尽さを面白がっているようだった。「ねえ、私がそんなことしたなんて信じられる?」とでも言っているようだった。これについてロラに訊くと、彼女は母がどのように語ったのか知りたがった。彼女は目を伏せながらじっと聞き入り、話が終わると悲しそうに私を見てこう言った。

「はい。そういうこともありました」

彼女が「奴隷」だと気づいた日

ロラと出会ってから7年後の1950年、母は父と結婚し、マニラへ引っ越した。その際、ロラも連れていった。祖父は長年のあいだ「悪魔に取り憑かれて」いて、1951年、それを黙らせるために自分のこめかみへ弾丸を打ち込んだ。母がその話をすることはほとんどなかった。

彼女は父親と同じく気分屋で、尊大で、内側には弱さを抱えていた。父の教えはどれも肝に銘じていて、その1つが、田舎の女主人にふさわしい振る舞い方だった。つまり、自分より地位の低い者に対しては、常に上に立つ者として行動する、ということだ。

それは、彼ら自身のためでもあり、家庭のためでもある。彼らは泣いて文句を言うかもしれないが、心の底では感謝しているはずだ。神の御心のままに生きられるよう助けてくれた、と。

1951年に、私の兄アーサーが生まれた。その次が私で、さらに3人が立て続けに生まれた。ロラは、両親に尽くしてきたのと同じように、私たち兄妹にも尽くすことを求められた。ロラが私たちの世話をしているあいだ、両親は学校に通い、「立派な学位はあるけれど仕事がない大勢の人々」の仲間入りをした。

だが、そこへ大きなチャンスが訪れた。父が、外務省でアナリストとして雇ってもらえることになったのだ。給料はわずかだったが、職場は米国だった。米国は、両親が子供の頃から憧れていた国だ。彼らにとって、願っていたことすべてが叶うかもしれない、夢の場所だった。

父は、家族とメイドを1人連れていくことを許された。おそらく共働きになると考えていたので、子供の世話や家事をしてくれるロラが必要だった。母がロラにそのことを告げると、母にとって腹立たしいことに、ロラはすぐには承諾しなかった。

それから何年も経ったあとにロラが当時のことを話してくれたのだが、実は恐ろしかったのだという。

「あまりに遠くて。あなたのお母さんとお父さんが私を帰らせてくれないんじゃないかと思ったんです」

結局、ロラが納得したのは、米国に行けばいろんなことが変わると、父が約束したからだった。米国でやっていけるようになったら、「おこづかい」をやると父は言った。そうすれば、ロラは両親や村に住む親戚に仕送りができる。

彼女の両親は、地面がむき出しの掘っ立て小屋に暮らしていた。ロラは彼らのためにコンクリートの家を建ててやれるし、そうすれば人生が変わる。ほら、考えてもごらんよ。

1964年5月12日、私たちはロサンゼルスに降り立った。ロラが母のところへ来てからすでに21年が経っていた。いろいろな意味で、自分にとっては父や母よりも、ロラのほうが親という感じがしていた。毎朝最初に見るのは彼女の顔だったし、寝る前に最後に見るのも彼女だった。

赤ちゃんの頃、「ママ」や「パパ」と言えるようになるよりずっと前に、ロラの名前を呼んでいた。幼児の頃は、ロラに抱っこしてもらうか、少なくともロラが近くにいないと絶対に眠れなかった。

家族が渡米したとき、私は4歳だった。まだ幼かったので、ロラが我が家でどういう立場なのかを問うことはできなかった。だが、太平洋のこちら側で育った兄妹や私は、世界を違った目で見るようになっていた。海を越えたことで、意識が変わったのだ。一方で、母と父は意識を変えることができなかった。いや、変えることを拒んでいた。

結局、ロラがおこづかいをもらうことはなかった。米国へ来て数年が経った頃、それとなく両親に訊いてみたことがあるという。当時、ロラの母親は病気で、必要な薬を買うお金がなかった。

「可能でしょうか?」

母はため息をついた。「よくそんなことを言えたもんだ」と父はタガログ語で答えた。

「カネに困っているのはわかってるだろ。恥ずかしいと思わないのか」

両親は、米国へ移住するために借金をしていて、米国に残るためにさらに借金していた。父は、ロサンゼルスの総領事館からシアトルのフィリピン領事館に異動した。年収5600ドルの仕事だった。収入を補うためにトレーラーの清掃の仕事を始め、それに加えて、借金の取り立てを請け負うようになった。

母は、いくつかの医療研究所で助手の仕事を見つけた。私たちが両親に会えることはほとんどなく、会えたとしても彼らはたいてい疲れ切っていて不機嫌だった。

母は帰宅すると、家がきちんと掃除されていないとか、郵便受けを確認していないなどと言っては、ロラを叱責した。「帰るまでに、ここに郵便を置いておけって言ったでしょ?」と、敵意をむき出しにタガログ語で母は言う。

「難しいことじゃないし、バカでも覚えられるでしょ」

そして父が帰宅すると、今度は彼の番だった。父が声を荒らげると、家中の誰もが縮こまった。ときには、ロラが泣き出すまで2人がかりで怒鳴りつけた。まるで、ロラを泣かせることが目的だったかのように。

私にはよくわからなかった。両親は子供たちによくしてくれたし、私たちは両親が大好きだった。だが、子供たちに優しくしていたかと思うと、次の瞬間にはロラに悪態をつくのだ。

ようやくロラの立場をはっきりと理解するようになったのは、11歳か12歳の頃だった。8歳年上の兄アーサーは、ロラの扱いに怒りを覚えるようになってから何年も経っていた。ロラの存在を理解するために「奴隷」という言葉を教えてくれたのはアーサーだった。その言葉を知る前は、ただ不運な家庭の一員だとしか思っていなかった。

両親が彼女を怒鳴りつけるのは嫌だったが、それがモラルに反することであり、彼女の立場そのものがモラルに反することだとは考えてみたこともなかった。

「彼女みたいに扱われてる人を、1人でも知ってるか?」とアーサーは私に聞いた。そして、ロラの境遇を次のようにまとめた。

無給。毎日働きっぱなし。長く座ったままだったり早く就寝したりすると、こっぴどく叱られる。口答えをすると殴られる。着ているのはおさがりばかり。キッチンで残り物を独りで食べる。ほとんど外出しない。家族のほかに友人はいないし、趣味もない。自分の部屋もない(彼女はどこか空いた場所に寝るのが普通だった。ソファかクローゼットか、妹たちの寝室の片隅か。よく洗濯物に囲まれて寝ていた)。

ロラと似たような立場の人を探しても、見つかるとしたらテレビや映画に出てくる奴隷だった。

奴隷の存在を隠し続けるしかなかった

ある晩、当時9歳だった妹のリングが夕食をとっていないと知った父が、ロラの怠慢を叱った。父は、ロラを見下ろしてにらみつけた。「食べさせようとしたんです」とロラは訴えた。だが彼女の返答は説得力がなく、さらに父をいら立たせるだけだった。そして、彼はロラの腕を殴った。ロラは部屋を飛び出した。動物のように泣き叫ぶ彼女の声が聞こえてきた。

「リングはお腹がすいてないって言ったんだ」と私は言った。

両親が振り返って私を見た。驚いた様子だった。いつも涙がこぼれる前にそうなるように、自分の顔がピクピクしているの��感じた。でも、絶対に泣くまいと思った。母の目には、これまで見たことのないものが浮かんでいた。もしかして、妬みだろうか?

「ロラを守ろうとしているのか」と父は訊いた。「そうなのか?」

「リングはお腹がすいてないって言ったんだ」

私はすすり泣くように、そう繰り返した。

私は13歳だった。私の世話に日々を費やしていたロラを弁護しようとしたのは、初めてのことだった。いつもタガログ語の子守唄を歌ってくれたし、私が学校に行くようになると、朝には服を着せて朝食を食べさせ、送り迎えをしてくれた。あるときは、長いあいだ病気で弱りきって何も喉を通らなかった私のために食べ物を噛み砕き、小さなかけらにして食べさせてくれたこともあった。

私が両脚にギ���スをしていたときは、彼女は手ぬぐいで体を洗ってくれたし、夜中に薬を持ってきてくれたりして、数ヵ月におよぶリハビリを支えてくれた。そのあいだずっと私は不機嫌だった。それでもロラが文句を言ったり、怒ったりすることは1度たりともなかった。

そんな彼女が泣き叫ぶ声を聞いて、頭がおかしくなりそうだったのだ。

祖国フィリピンでは、両親はロラの扱いを隠す必要性を感じなかった。米国では、さらにひどい扱い方をしたが、それを隠すために苦心した。家に客が来れば、彼女を無視するか、何か訊かれたら嘘をついてすぐに話題を変えた。

シアトル北部で暮らしていた5年間、私たちはミスラー家の向かいに住んでいた。ミスラー家は賑やかな8人家族で、サケ釣りやアメリカン・フットボールのテレビ観戦の楽しみを教えてくれた。

テレビ中継を観て応援する私たちのところへ、ロラが食べ物や飲み物を持ってくる。すると両親はほほ笑んで「ありがとう」と言い、ロラはすぐに姿を消す。あるとき、ミスラー家の父が、「キッチンにいるあの小柄な女性は誰?」と尋ねた。「フィリピンの親戚だよ」と父は答えた。「とてもシャイでね」と。

@@@@@

だが、私の親友だったビリー・ミスラーは、そんな話を信じなかった。よくうちに遊びに来ていたし、週末に泊まることもあったので、我が家の秘密を垣間見ていた。

彼は一度、私の母親がキッチンで叫んでいるのを聞き、何事かとその場を覗き、顔を真っ赤にした私の母とキッチンの隅で震えていたローラを見た。私はその数秒後にその場を目撃した。ビリーはきまり悪さと混乱が混ざったような表情をしていた。"あれはなんだ?" 私はそれを無視して忘れるように彼に言った。

ビリーはおそらくローラをかわいそうだと思ったことだろう。彼はローラの料理を誉め、彼女をよく笑わせた、私が見たことがないような笑顔をローラは見せていた。お泊り会の時にはローラはビリーの好きなフィリピン料理、白米の上に牛肉のタパを乗せた料理を作った。(beef tapa:薄切りの牛肉を魚醤・ニンニク・砂糖・塩・コショウなどで炒めたフィリピンの家庭料理)

料理はローラ唯一の自己主張の方法であり、それは雄弁だった。少なくとも私たちは彼女の作る料理に愛情というものがこもっていたことをはっきりと認識していた。

そしてある日、私がローラを遠い親戚だと言及したとき、ビリーは私と最初に会った時に私が彼女を祖母だと言っていたことを思い出した。

「なんていうかまあ、彼女はそのどちらでもあるというか...」と私は言葉を濁した。

「なぜ彼女はいつも働いているのんだ?」

「彼女は仕事が好きなんだよ」私は答えた。

「君のお父さんとお母さん、彼らはなぜ彼女を怒鳴りつけるんだ?」

「彼女は耳があまり良くないんだ...」

真実を認めてしまうことは、私たち家族の秘密を暴露することを意味していた。 アメリカに来て最初の10年、私たちはこの新しい土地になじむ努力をした。だが奴隷を持つという事実だけはこの国ではなじみようがなかった。奴隷を持つことは、私たち家族に対する、私たちのこれまですべてに対する強い疑問を私にもたらした。

私たちはこの国に受け入れられるに足るべき存在なのか?

私はそれらをすべて恥じていた、私自身もまた共犯者であることを含めて。彼女が調理した料理を食べ、彼女が洗濯しアイロンをかけクローゼットに掛けた服を着たのは誰だ? しかしそれでも、仮に彼女を失うことになっていたとしたらそれは耐えがたいことだっただろう。

そして奴隷を持つということ以外にもう一つ、私たち家族には秘密があった。私たちが米国に到着してから5年後、ローラの滞在許可は1969年に失効していたのだ。彼女は私の父の仕事に関連付けられた特殊なパスポートで渡米した。

父は上司との度重なる仲たがいの後に勤めていた領事館を辞め、その後も米国に滞在するため家族の永住権を手配したが、ローラにはその資格がなかった。父はローラを国に返すべきだったのにそうしなかった。

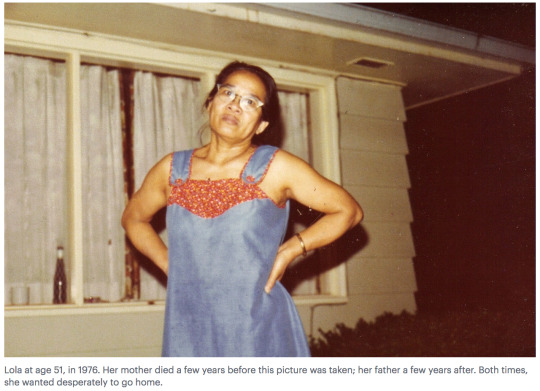

51歳当時のローラ。彼女の母親はこの写真が撮影される数年前に亡くなった。彼女の父親はその数年後に亡くなった。いずれの時も、ローラは家に帰ることを必死に望んでいた。

All photos courtesy of Alex Tizon and his family ローラの母、フェルミナは1973年に亡くなった。彼女の父、ヒラリオは1979年に亡くなった。いずれの時も、ローラは家に帰ることを必死に望んでいた。 そのいずれの時も、私の両親は "すまない" "金銭的な余裕がないんだ" "時間を作れない" "子供たちは君を必要としている" と答えた。

私の両親は後に私に告白したが、そこには彼女を返すことのできない別な理由もあったという。当局がローラの存在を知れば、そして彼女が望む通りアメリカを離れようとすれば当然知られることになる、そんな事態になれば私の両親は大きな問題を抱えることになり、国外追放される可能性も十分にあったのだ。

彼らはそのような危険を犯すことはできなかった。ローラの法的地位は「逃亡者」となっていた。彼女はほぼ20年間 "逃亡者" としてこの国に滞在したのだ。

彼女の両親がそれぞれ亡くなった後、ローラは何ヶ月も陰鬱に、寡黙になった。私の両親がしつこく言っても彼女はほとんど答えなかった。だがしつこく言うことが終わるわけでもなく、ローラは顔を下げたまま仕事をした。

そして父が仕事を辞めたことで私たち家族にとって波乱となる時期が始まった。金銭的に苦しくなり、両親は次第に仲たがいするようになった。シアトルからホノルルへ、そしてまたシアトルへと戻り今度はブロンクスへ、転々と住む場所を変え、最終的にはオレゴン州の人口750人の小さな町、ウマティラに移った。

その間、母は医療インターンとして、その後に研修医として24時間シフトで働き、父は何日も姿を消すようになっていた。父はよくわからない仕事をしており、それとは別に私たちは後に浮気やらなにやらしていたことを知った。突然家に帰り、ブラックジャックで新しく買ったステーションワゴンを失ったと言い出したこともあった。

家では、ローラが唯一の大人になる日が何日も続くようになった。彼女は家族の中で最も私たち子供の生活を知る人となっていた、私の両親にはそのような精神的な余裕がなかったがゆえに。

私たち兄弟はよく友人を家に連れてきた。彼女は私たちが学校の事や女の子の事、男の子の事、私たちが話す様々な事を聞いていた。彼女は私たちの会話をただ立ち聞きしていただけで、私が6年生から高校までフラれたすべての女の子の名前を挙げることができたのにはまいった。

そして私が15歳の時、父は家族から去っていった。私は当時それを信じたくなかったが、父が私たち子供を捨てて、25年の結婚生活の後に母を捨てたという事実だけがそこにあった。

母はその時点で正式な医師になるまであと1年を要しており、また彼女の専門分野である内科医は特に儲かる仕事ではなく、さらに父は養育費を払わなかったので、お金のやりくりはいつも大変だった。

母は仕事に行ける程度には気持ちをしっかり保っていたが、夜は自己憐憫と絶望で崩壊した。この時期の母の慰めとなったのはローラだった。

母が小さなことで彼女にきつく言う度に、ローラはより かいがいしく母の世話をした。母の好きな料理を作り、母のベッドルームをより丁寧に掃除した。夜遅くにキッチンカウンターで母がローラに愚痴をこぼしたり、父のことについて話したり、時には意地悪く笑ったり、父の非道にを怒ったりしていたのを何度も目撃した。

ある夜、母は泣きながらローラを探しリビングルームに駆け入り、彼女の腕の中で崩れ落ちた。ローラは、私たちが子供の頃にそうしてくれたように母に穏やかに話しかけていた。私はそんな彼女に畏敬の念を抱いた。

"母と私は一晩中言い争った。お互い泣きじゃくっていたが、私たちはそれぞれ全く違った理由で泣いた。"

私の両親が離婚してから数年後、私の母親は友人を通して知り会ったクロアチアの移民イワンという男性と再婚し母はローラに対し新しい夫にも忠誠を誓うことを要求した。イワンは高校を中退し過去4回結婚しているような男で、私の母の金を使いギャンブルに興じる常習的なギャンブラーだった。

だがそんなイワンは、私が見たことのないローラの一面を引き出した。 彼との結婚生活は当初から不安定であり、特に彼が母の稼いだお金を使い込むことが問題となっていた。

ある日、言い争いの末に母が泣きイワンが怒鳴り散らしていると、ローラは歩いて両者の間に立ちふさがった。彼は250ポンド(約113kg)の大柄な男でその怒鳴り声は家の壁を揺らすような大きさだった。だがローラはそんなイワンの正面を向き、毅然とした態度で彼の名前を呼んだ。彼は面食らったような顔でローラの顔を見た後、何か言いたそうにしながらも側の椅子に座った。

そんな光景を何度も目撃したが、ローラはそんほとんどにおいて母が望んだとおりイワンに粛々と仕えていた。私は彼女のそのような様を、特にイワンのような男に隷属する様を見るのがとても辛かった。だがそれ以上に私の感情を高ぶらせ、最終的に母と間で大喧嘩に発展させたのはもっと"日常的"なことだった。

母はローラが病気になるといつも怒っていた。ローラが動けないことで生じる混乱とその治療にかかる費用に対処することを望んでいなかった母は、ローラに対し嘘を言っているのだろうと、自分自身のケアを怠った結果だと非難した。

そして1970年代後半にローラの歯が病気によって抜け落ちた時も母は適切な対処を拒んだ。ローラは何ヶ月も前から歯が痛いと言っていた。

「きちんと歯を磨かないからそうなるんでしょ」母は彼女にそう言った。私は彼女を歯医者に連れていかなければならないと何度も言った。もう50代になる彼女はこれまで一度として歯医者に行ったことがなかった。当時私は1時間ほど離れた大学に通っており家に帰るたびにそのことを母に言った。

ローラは毎日痛み止めのためのアスピリンを服用し、彼女の歯はまるで崩れかけたストーンヘンジのようになっていた。そしてある晩、ローラがかろうじてまともな状態で残っていた奥歯でパンを必死に噛んでいる様を見て、私は怒りのあまり我を失った。

@@@@

母と私は、夜通し口げんかした。2人とも泣きじゃくった。

母は、みんなを支えるために身を粉にして働くのに疲れ切っているし、いつも子供たちがロラに味方するのにうんざりしているし、ロラなんてどこかへやってしまえばいいじゃないか、そもそも欲しくなんかなかったし、私のような傲慢で聖人ぶった偽善者なんか産まなければよかった──とまくし立てた。

彼女の言葉を反芻して、私は反撃に出た。

偽善者ならそっちだ。ずっと見せかけの人生を生きているじゃないか。自己憐憫に浸ってばかりだから、ロラの歯が腐ってほとんど食べられないことに気づかないんだろ。1度でいいから、自分に仕えるために生きている奴隷ではなく、1人の人間として見てあげたらどうなんだ?

「奴隷って言ったわね」

母はその言葉をかみしめた。

「奴隷ですって?」

母は、ロラとの関係は私には絶対に理解できないと言い放ち、その晩はそれで終わった。

何年も経ったいまでも、痛みをこらえるような、あのうめき声を思い返すだけで腹を殴られたような気分になる。自分の母親を憎むのは最悪だが、その晩は母を憎んだ。彼女の目を見る限り、母も私を憎んでいるのは明らかだった。

けんかの結果、ロラが自分から子供たちを奪ったという母の恐怖は強まり、ロラ本人にそのつけが回った。母はよりいっそうつらく当たった。

「私があなたの子供たちに嫌われてさぞかしうれしいでしょうね」などと言って苦しめた。私たちがロラの家事を手伝うと、母は憤った。「ロラ、もう寝たほうがいいんじゃないの」と皮肉たっぷりに言うのだ。

「働きすぎよ。あなたの子供たちが心配してるわよ」

そのあとで、寝室へロラを呼び出し、ロラは目をパンパンに腫らせて戻ってくるのだった。

ついにロラは、自分を助けようとするのはやめてくれと訴えた。

「なぜ逃げないの?」と私たちは訊いた。

「誰が料理をするんですか?」と彼女は答えた。誰が仕事を全部やるのか、と言いたかったのだろう。誰が子供たちの世話をするのか? 誰が母の世話をするのか?

別のときには、「逃げるところなんてどこにあるんですか?」と言った。この返事のほうが真実味があった。米国へ来るときは大慌てだったし、息をつく間もなく10年が経った。振り返ると、さらに10年が経とうとしていた。ロラは白髪が増えていた。

噂によれば、故郷の親戚たちは、約束された仕送りが届かないので、何が起きたのかといぶかしんでいたという。彼女はもはや恥ずかしくて帰れなかったのだ。

ロラには米国に知り合いもいなかったし、移動手段もなかった。電話に戸惑ったし、ATMやインターホン、自動販売機、キーボードのついているもの全般など、機械を見るとパニックに陥った。早口な人の前では言葉を失い、逆に彼女のたどたどしい英語を聞くと相手が言葉を失った。予約をしたり、旅行を企画したり、用紙に記入したり、自分で食事を注文したりすることができなかった。

あるとき、私の銀行口座からお金を下ろせるキャッシュカードをロラに与え、使い方を教えてやったことがある。1度は成功したが、2度目は動揺してしまい、それっきり試そうともしなかった。でも、私からの贈り物だと思ってカードは大切にしてくれていた。

また、車の運転を教えようとしたこともある。彼女は手を振って拒否したが、私はロラを抱き上げて車のところへ連れていき、運転席に座らせた。お互い笑い転げていた。

20分かけて、ギアやメーターなどをひと通り説明してあげた。初めは楽しそうにしていた彼女の目が、恐怖におびえはじめた。エンジンをかけてダッシュボードが点灯すると、あっという間に彼女は車を飛び出して家のなかへ駆け込んでしまった。あと数回やってみたが、結果は同じだった。

私は、運転ができるようになれば、彼女の人生が変わると思ったのだ。自分でいろんなところへ行ける。母との生活が耐えられなくなったら、どこかへ逃げて、2度と戻らなければいい。

高まる緊張

4車線が2車線になり、舗装道路が砂利道になった。竹を大量に載せた水牛や車が行き交うなか、三��車が通り抜ける。ときおり私たちのトラックの前を犬やヤギが走り抜け、バンパーをかすめそうになる。でもマニラで雇った中年の運転手、ドゥーズはスピードを落とさない。

私は地図を取り出し、目的地のマヤントクという村までの道のりをたどった。窓の外には、遠くのほうで大量の折れた釘のように腰を曲げている人々がかすかに見えた。数千年前からずっと変わらないやり方で、米を収穫しているのだ。到着まであと少しだ。

自分の膝の上に置いた安っぽいプラスチックの箱をトントンと叩き、磁器や紫檀で作られた本物の骨壷を買わなかったことを後悔した。ロラの親族はどう思うだろう?

もちろん、そんなに大勢いるわけではなかった。唯一残った兄妹が妹のグレゴリアで、年齢は98歳を数え、物忘れが激しくなっているとのことだった。親戚によると、ロラの名前を聞くとわっと泣き出し、次の瞬間にはなぜ泣いているのかわからなくなるという。

私は、ロラの姪と連絡をとっていた。彼女は次のように1日を計画していた。私が到着したら、ささやかな追悼式をおこない、祈りを捧げ、マヤントクの共同墓地の一画に遺灰を埋葬する──。

ロラが亡くなってから5年が経っていたが、まだ最後のさようならを言っていなかった。間もなくそのときが訪れようとしていた。

朝からずっと、激しい悲しみを抑え込もうと必死だった。ドゥーズの前で泣いたりしたくなかった。自分の家族のロラに対する扱いを恥じるよりも、マヤントクの親族が私にどんな態度をとるだろうかという不安よりも、彼女を失ったことの重さのほうが強かった。まるで前の日に亡くなったばかりのようだった。

ドゥーズは、ロムロ・ハイウェイを北西へと進み、カミリングで急カーブを左に曲がった。母と祖父の出身地だ。2車線が1車線になり、砂利道が泥道になった。道は、カミリング川沿いを走っていた。竹でできた家々が並び、前方には緑の丘が見えた。いよいよ大詰めだ。

物語の脇役であり続けたロラ

母の葬儀で述べた私の弔辞は、すべて本当のことだった。母は、勇敢で、活発だったこと、貧乏くじを引くこともあったけれど、彼女にできる限りのことをしたこと。幸せなときはキラキラしていたし、子供たちを溺愛していて、オレゴン州セイラムに正真正銘の「我が家」を作ってくれたこと。

1980年代と90年代を通して、その家は私たちがそれまで持ち得なかった「定住地」となった。もう1度ありがとうと言えたらいいのに。

私たちみんなが母を愛していた。

だが、ロラの話はしなかった。母が晩年になると、私は彼女といるときにはロラのことを考えないようにしていた。自分の脳にそういう細工をしないと、母を愛することができなかった。それが、親子関係を続ける唯一の方法だったのだ。

とくに、90年代半ばから母が病気がちになってからは、良い関係を保ちたかった。糖尿病、乳がん、そして、血液と骨髄の癌である急性骨髄性白血病。まるで1晩のう���に健常から虚弱へと転落したようだった。

あの大げんかのあと、私は家を避けるようになり、23歳でシアトルに移り住んだ。ただ、実家を訪れると、変化が見られるようになった。母はいつもの母だったが、前のように容赦ない人間ではなかった。

ロラに立派な入れ歯と寝室を与えた。ロナルド・レーガンによる画期的な1986年の移民法で、何百万人という不法移民に合法的な滞在が認められたとき、ロラのTNT(フィリピン人が言う「タゴ・ナング・タゴ」の略。「逃亡中という意味)としての立場を変えようと尽力した兄妹と私に母も協力した。

手続きは長引いたが、1998年10月にロラは米国籍を取得した。母が白血病と診断されてから4ヵ月後のことであり、母はそれから1年間しか生きられなかった。

そのあいだ、母と後夫のアイヴァンはよくオレゴン州の海岸にあるリンカーンシティへ出かけた。ロラを連れていくこともあった。ロラは海が大好きだった。海の向こう側には、いつの日か戻れることを夢見る島々があった。

それに、母がくつろいでいるとロラは幸せだった。海辺で過ごす午後や、田舎で暮らした日々の思い出話をするキッチンでの15分間だけで、ロラは長年の苦悩を忘れてしまうようだった。

だが、私はそんな簡単に忘れることはできなかった。でも、母の違う面が見えるようにもなってきた。亡くなる前に、母はトランク2つにぎっしり詰められた日記を見せてくれた。彼女が寝ているすぐそばで日記に目を通していると、長年私が目を向けようともしなかった母の人生が垣間見えた。

彼女は、女性が医者になることが珍しかった時代に医学部へ通った。米国へ来て、女性として、また移民の医者として、尊敬を勝ち取るために闘った。セイラムにある「フェアビュー・トレーニングセンター」で20年働いた。そこは、発達障害者のための公共機関だった。

皮肉なことに、母はキャリアを通じて弱者を助け続けていたのだ。彼らは母を崇拝した。女性の同僚たちと仲良くなり、一緒にたわいのない女子っぽいことをして遊んだ。靴を買いに行ったり、お互いの家でおめかしパーティーをしたり、冗談で男性器の形をした石けんや半裸の男性たちのカレンダーを贈り合ったりした。そのあいだずっと、彼女たちは笑い転げていた。

当時のパーティーの写真を見ていると、母は家族とロラに見せるのとは別の自分を持っていたことがわかった。それは当然のことだろう。

母は子供たち一人ひとりについて詳しく書いていた。誇りに思ったり、愛しく感じたり、憤慨したり、その日に感じたことを綴っていた。さらに、夫たちについての記述は膨大な量におよんだ。彼らは、母の物語に登場する複雑な性格の人物として描かれていた。

ただし、私たちはみんな重要な登場人物だったのに、ロラは付随的な存在だった。登場するとすれば、別の誰かの物語における端役としてだった。

「最愛のアレックスをロラが新しい学校へ連れていった。新しい友だちが早くできると��いな。引っ越ししたことの寂しさがまぎれるように……」

それから私について2ページ書かれ、ロラはもう登場しない。そんな調子だった。

母が亡くなる前日、カトリックの神父が臨終の秘跡をおこなうために訪れた。ロラはベッドの脇に座り、ストローを差したカップをいつでも母の口元へ持っていけるように備えていた。これまで以上に母を気づかい、これまで以上に優しくしていた。弱りきった母につけ込むこともできたし、復讐をすることもできたのに、ロラの態度は真逆だった。

神父は母に、赦したいこと、または赦しを請いたいことはないかと尋ねた。

彼女はまぶたが半ば閉じたまま部屋を見回したが、何も言わなかった。そして、ロラを直接見ることなく、伸ばした手を彼女の頭に乗せた。一言も発さずに。

「奴隷」から抜けきれない日々

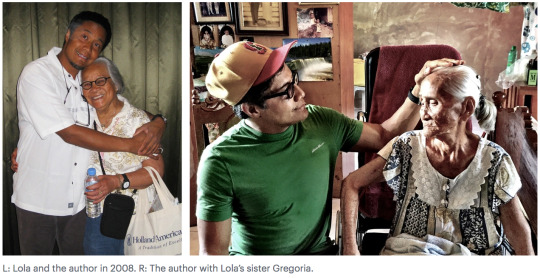

ロラを私のところへ呼び寄せたのは、彼女が75歳のときだった。私はすでに結婚して2人の娘がいて、周りに木が生い茂る居心地の良い家に住んでいた。2階からはピュージェット湾を見渡せた。

ロラには寝室を与え、何をしてもいいよと伝えた。朝寝するなり、テレビドラマを観るなり、1日中ゆっくりするなりすればいい。人生で初めて、思いっきりリラックスして、自由になればいい、と。でも、そう簡単にはいかないと覚悟しておくべきだった。

私は、ロラの厄介なところをすっかり忘れてしまっていた。風邪をひくからセーターを着ろとしつこいこと(すでに私は40歳を超えているというのに)。常に父とアイヴァンの不平を言うこと(父は「怠け者」で、アイヴァンは「ヒル」だった)。

私は次第に彼女を無視する方法を身につけた。でも、異常なまでの倹約ぶりは無視しにくかった。ロラは何も捨てたがらなかったのだ。しかも、私たちがまだ使えるものを捨てていないか、ゴミを漁って確認していた頃もあった。紙タオルがもったいないと、何度も洗って使い回し、しまいには手のひらでボロボロになるほどだった(誰もそれを触ろうとしなかった)。

キッチンはレジ袋やヨーグルト容器、空の瓶でいっぱいになり、家の一部はゴミ置き場になった。そう、ゴミだ。それ以外に言いようがない。

朝はみんな時間がなくて、バナナかグラノーラ・バーをかじりながら家を飛び出すというのに、ロラは朝食を作った。ベッドメイクをして、洗濯物をした。家の掃除をした。最初は辛抱強く、私はこう言い続けた。

「ロラ、そんなことはしなくていいんだよ」「ロラ、自分たちでやるからね」「ロラ、それは娘たちの仕事だよ」

だが、「オーケー」と彼女は言ってそのまま続けるのだった。

ロラがキッチンで立ったまま食事をとっていたり、私が部屋に入ってくると体をこわばらせて掃除を始めたりするのを目にすると、イライラさせられた。数ヵ月経ったある日、話がある、と彼女を呼んだ。

「私は父じゃない。あなたは奴隷じゃないんだ」

そう言って、ロラの奴隷のような行動を一つひとつ挙げていった。彼女が驚いた様子なのに気づいたので、ゆっくり深呼吸してロラの顔を手のひらで包んだ。エ��フのような顔のロラが、探るような目で私を見つめ返す。私はその額にキスをした。

「ここはあなたの家だ。私たちに仕えるために来たわけじゃない。リラックスしていいんだ。オーケー?」

「オーケー」と彼女は言った。そして、掃除に戻った。

彼女は、それ以外どうしていいかがわからなかったのだ。次第に、リラックスするべきなのは自分だ、と気づいた。夕食を作りたがるなら、やらせてあげよう。ありがとうと言って、自分たちは皿洗いをすればいい。何度も自分に言い聞かせなければならなかった。やりたいようにやらせてあげろ、と。

ある晩、帰宅するとロラがソファでパズルをしているところを見つけた。脚を伸ばして、テレビをつけ、隣にはお茶を用意して。彼女は私をチラッと見て、きまり悪そうに真っ白な入れ歯を見せて笑い、パズルを続けた。良い調子だ、と私は思った。

さらに彼女は、裏庭でガーデ��ングを始めた。バラやチューリップや、あらゆる種類の蘭を植えて、それにかかりっきりになる日もあった。また、近所を散歩するようにもなった。

80歳くらいになると関節炎がひどくなり、杖をつくようになった。キッチンでは、かつては下働きの料理人のようだったのが、その気になったときだけ創作する職人肌のシェフのようになった。ときに豪華な食事を作っては、ガツガツ食べる私たちを見てにっこり笑うのだった。

ロラの寝室の前を通ると、よくフィリピンのフォークソングのカセットが聞こえてきた。彼女は同じテープを何度も繰り返し聴いていた。私と妻は週に200ドルを彼女に渡していたが、ほぼ全額を故郷の親戚に送金していることを知っていた。そしてある日、裏のベランダに座り込んだ彼女が、誰かから送られてきた村の写真をじっと眺めているのを発見した。

「ロラ、帰りたいの?」

彼女は写真を裏返しにして、そこに書かれた文字を指でなぞった。それから再び表に返し、1点を食い入るように見つめた。

「はい」と彼女は答えた。

83歳の誕生日のすぐあとに、彼女が帰国するための飛行機代を出してあげた。1ヵ月後に私もそこへ行き、米国に戻る意志があるなら連れて帰ることになっていた。はっきり口にしていたわけではないが、旅の目的は、長年のあいだ戻りたいと切望していた場所が、今なお故郷のように感じられるかどうかを見極めることだった。

彼女は答えを見つけた。

「何もかも違っていた」と、故郷のマヤントクを私と散歩しながら彼女は言った。昔の畑はなくなっていた。家もなかった。両親も、兄妹のほとんども亡くなっていた。まだ生きていた子供時代の友人は、他人のようだった。再会できてうれしかったけれど、昔と同じではなかった。ここで死にたいけれど、まだその心構えができていない。

「じゃあ庭の世話に戻る?」と私は訊いた。すると、ロラはこう答えた。

「はい。帰りましょう」

奴隷としての一生

ロラは、幼い頃の私や兄妹たちと同じように、私の娘たちの世話をしてくれた。学校が終わると、話を聞いてあげて、おやつを与えた。妻や私と違って(主に私だが)、学校の行事や発表会を最初から最後まで楽しんだ。もっと見たくて仕方がないようだった。いつも前のほうに座り、プログラムは記念���とっておいた。

ロラを喜ばせるのは簡単だった。家族旅行にはいつも連れていったが、家から丘を降りたところのファーマーズ・マーケットに行くだけで興奮した。遠足に来た子供のように目を丸くして、「見て、あのズッキーニ!」と言うのだ。

毎朝、起きると必ずやることと言えば、家中のブラインドを開けることだった。そして、どの窓でも一瞬立ち止まって外の景色を眺めるのだ。

さらに、自力で字を読めるようになった。驚くべき進歩だった。長年かけて、彼女は文字をどう発音するかを解明したようだった。たくさん並べられた文字のなかから、単語を見つけてマルで囲むパズルをよくやっていた。

部屋にはワードパズルの冊子が積み上げられていて、鉛筆で何千という単語がマルで囲まれていた。毎日ニュースを見て、聞き覚えのある単語を拾った。それから、新聞で同じ単語を見つけ、意味を推測した。そのうち、新聞を最初から最後まで毎日読むようになった。

父は、彼女のことを「無知だ」と言っていた。でも、8歳から田んぼで働くのではなく、読み書きを学習していたら、どんな人になっていただろうかと考えずにいられなかった。

一緒に暮らしていた12年のあいだずっと、私は彼女の人生についていろいろ質問をした。私が彼女の身の上話の全容を明らかにしようとするのを、彼女は不思議がった。私が質問すると、たいていまずは「なぜ?」と返すのだった。

なぜ彼女の幼少期のことを知りたがるのか? どうやってあなたの祖父と出会ったのかなんて、なぜ知りたがるのか?

妹のリングに、ロラの過去の恋愛について訊いてもらおうとしたことがある。妹のほうが話しやすいと思ったからだ。リングにそう頼むと、彼女はケラケラ笑った。その笑い方は、要するに協力する気がないということだ。

@@@@@

ある日ローラと私がスーパーで買った食料品をしまっている時に、私はついこんな質問をしてしまった。

「ローラ、君は誰かとロマンチックな経験をしたことはあるかい?」

彼女は微笑んで、彼女が唯一持つ異性との話を私に語った。

彼女が15歳くらいの頃、近くの農場にペドロというハンサムな男の子がおり数ヶ月間彼らは一緒に米を収穫したという。そして一度、彼女はその作業に使っていたボロという農具を手から落としてしまったことがあり、彼はすぐにそれを拾い上げ手渡してくれた。

「私は彼が好きでした。」ローラはそう言った。

しばらく、お互い黙ったままで

「それから?」

「彼はその後すぐに立ち去ってしまいました。」

「それから?」

「それだけです。」

「ローラ、君はセックスをしたことがある?」私は、まるで誰か他人が言ったのを聞いたように、そう質問する自分の声を聞いた。

「いいえ。」彼女はそう答えた。

彼女は個人的な質問に慣れていなかった。彼女は私の質問に1つまたは2つの単語で答えることが多く、単純な物語でさえも引き出すには何十もの質問が必要だった。私はそれらの質問を通してそれまで知り得なかった彼女の一面を知った。

ローラは母の残酷な仕打ちにはらわたが煮えたぎる思いをしたが、それにも��かわらず母が亡くなったことを悲しく思っていたことを知った。彼女がまだ若かった頃、時々どうしようもなく寂しさを感じ泣くことしかできなかった日が何度もあったことを知った。

何年も異性と付き合うことを夢見ていたことを知った、私は彼女が夜に大きな枕で抱かれるように包まれた状態で寝ている光景を目撃したことがある。だが老後の今、私に語ってくれた話によると、母の夫たちと一緒に暮らすうちに独り身でいることはそれほど悪くないと思ったという。彼女はその二人、父とイワンについては全く懐旧の情に駆られないそうだ。

もしかしたら、彼女が私の家族に迎えられることなく故郷マヤントクで暮らしていたら、結婚し、彼女の兄妹のように家族を持っていたら、彼女の人生はより良いものになっていたかもしれない。だがもしかしたら、それはもっと悪いものになっていたかもしれない。ローラの2人の妹、フランシスカとゼプリャナは病気で亡くなり、兄弟であるクラウディオは殺されたと後に聞かされた。

そんな話をしているとローラは、今そんな "もし" の話をして何になるのかと言った。"Bahala na" が彼女の基本理念だった。

bahalaの本来の意味は「責任」。フィリピン人の性格を表現する時によく使われる「Bahala na(バハーラ ナ)」:何とかなるさは、「Bahala na ang Diyos(バハーラ ナ アン(グ) ジョス)」:神の責任である→神の思し召しのままに→運を天にまかせよう、というところから来ている。「Bahala」自体はそんないい加減な意味の表現ではないので注意が必要。 フィリピン語(タガログ語) Lesson 1より http://www.admars.co.jp/tgs/lesson01.htm

ローラは彼女が送ってきた人生は、家族の別の形のようなものだったと語った。その家族には8人の子供がいた、私の母と、私とその4人の兄弟、そして今共に過ごす2人の私の娘だ。その8人の子供たちが、自分の人生に生きた価値を作ってくれたと、彼女はそう言った。

私たちの誰もが彼女の突然の死に準備ができていなかった。

"彼女は当時字を読めなかったが、とにかくそれを取っておこうとしたのだ。"

ローラは夕食を作っている最中に台所で心臓発作を起こし、その時私は頼まれた使いに出ていた。家に戻り倒れている彼女を見つけた私はすぐさま病院に運んだ。数時間後の午後10時56分、病院で、何が起きているのか把握する前に彼女は去ってしまった。すぐに全ての子供たちと孫たちがその知らせを受け取ったが、どう受け止めていいかわからない様子だった。ローラは11月7日、12年前に母が亡くなった日と同じ日に永眠した。86歳だった。

私は今でも車輪付き担架で運ばれる彼女の姿を、その光景を鮮明に思い出せる。ローラの横に立った医師は この褐色の子供くらいの身長の女性がどんな人生を歩んできたか想像もつかないだろうと思ったのを覚えている。

彼女は私たち誰もが持つ利己的な野心を持たず、持てなかった。彼女の周りの人々のためにすべてをあきらめる様は、私たちに彼女に対する愛と絆と尊敬をもたらした。彼女は私の大家族の中で崇敬すべき神聖な人となっていた。

屋根裏部屋にしまわれた彼女の荷物を解く作業には数ヶ月かかった。そこで私は、彼女がいつか字を読むことができるようになった時のために保管しておいた1970年代の雑誌のレシピの切り抜きを見つけた。私の母の写真が詰まったアルバムを見つけた。 私の兄弟姉妹が小学校以降獲得した賞の記念品も見つけた、そのほとんどは私たち自身が捨たもので彼女はそれらを "救いあげて" くれていた。

そしてある日、そこに黄色く変色した新聞の切り抜きが、私がジャーナリストとして書いた記事が大切に保管されているのを見つけ、泣き崩れそうになった。彼女は当時字を読めなかったが、とにかくそれを取っておこうとしたのだ。

竹と板でできた家々が並ぶ村の中央にある小さなコンクリートの家に私を乗せたトラックが止まる。村の周囲には田んぼと緑が無限に広がっているようだった。 私がトラックから出る前に人々が家の外に出てきた。運転手は座席をリクライニングにして昼寝を取りはじめた。私はトートバッグを肩に掛け、息を呑み、ドアを開けた。

「こちらです」

柔らかい声で、私はそのコンクリート製の家へ続く短い道に案内された。私の後を20人ほどの人が続く。若者もいたがその多くが老人だった。

家に入ると、私以外の人たちは壁に沿って並べられた椅子とベンチに座った。部屋の中央には何もなく私だけが立っていた。私はそのまま立ちながら私のホストを待った。それは小さな部屋で暗かった。人々は待ち望んだ様子で私を見ていた。

「ローラはどこですか?」

隣の部屋から声が聞こえ、次の瞬間には中年の女性が笑顔を浮かべこちらに向かってきた。ローラの姪、エビアだった。ここは彼女の家だった。彼女は私を抱きしめて、「ローラはどこですか?」と言った。

私はトートバッグを肩から降ろし彼女に渡した。彼女は笑顔を浮かべたままそのバッグを丁寧に受け取り、木製のベンチに向かって歩みそこに座った。彼女はバッグから箱を取り出しじっくりと眺めた。

「ローラはどこですか?」

と彼女は柔らかく言った。この地域の人々は愛する人を火葬する習慣がなかった。彼女は、ローラがそのような形で帰ってくることを予想していなかった。

彼女は膝の上に箱を置き、その額を箱の上に置くように折れ曲がった。彼女はローラの帰還を喜ぶのではなく、泣き始めた。

彼女の肩が震え始め、泣き叫び始める。それは私がかつて聴いたローラの嘆き悲しむ声と同様の悲痛な叫び声だった。

私はローラの遺灰をすぐに彼女の故郷に返さなかった、これほど彼女を気にしていた人がいたことを、このような悲しみの嵐が待ち受けていることを想像していなかったのだ。私がエビアを慰めようとする前に、台所から女性が歩み寄り彼女を抱きしめ共に泣き始めた。

そして部屋が嘆き声の轟音で包まれた。目の見えなくなった人、歯が抜け落ちた人、皆がその感情をむき出しにすることをはばからず泣いた。それは約10分続いた。気づけば私も涙を流していた。むせび泣く声が止み始め、再び静寂が部屋を包んだ。

エビアは鼻をすすりながら、食事の時間だと言った。誰もが列を成してキッチンに入る。誰もが目を腫らしていた。そして急に顔を明るくして、故人について語り合い、故人を偲ぶ準備を始めた。

私はベンチの上に置かれた空のトートバッグをチラリと見て、ローラが生まれた場所に彼女を戻すことが正しいことだったと実感した。

原典

『My Family’s Slave』By Alex Tizon(The Atlantic)

She lived with us for 56 years. She raised me and my siblings without pay. I was 11, a typical American kid, before I realized who she was.

翻訳

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/06/lolas-story/524490/

https://kaikore.blogspot.com/2018/01/lolas-story.html

https://courrier.jp/news/archives/89516/?utm_source=article_link&utm_medium=longread-lower-button&utm_campaign=articleid_89495

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Family’s Slave

By Alex Tizon

--

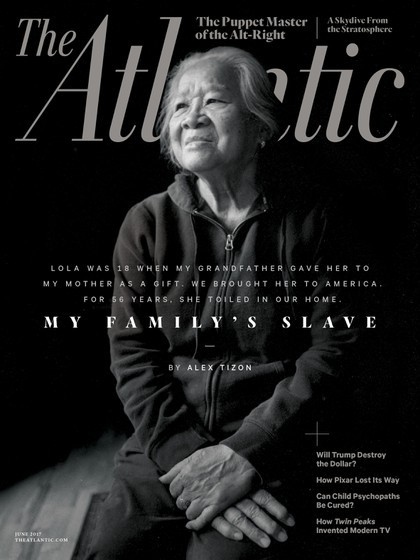

The ashes filled a black plastic box about the size of a toaster. It weighed three and a half pounds. I put it in a canvas tote bag and packed it in my suitcase this past July for the transpacific flight to Manila. From there I would travel by car to a rural village. When I arrived, I would hand over all that was left of the woman who had spent 56 years as a slave in my family’s household.

Her name was Eudocia Tomas Pulido. We called her Lola. She was 4 foot 11, with mocha-brown skin and almond eyes that I can still see looking into mine—my first memory. She was 18 years old when my grandfather gave her to my mother as a gift, and when my family moved to the United States, we brought her with us. No other word but slave encompassed the life she lived. Her days began before everyone else woke and ended after we went to bed. She prepared three meals a day, cleaned the house, waited on my parents, and took care of my four siblings and me. My parents never paid her, and they scolded her constantly. She wasn’t kept in leg irons, but she might as well have been. So many nights, on my way to the bathroom, I’d spot her sleeping in a corner, slumped against a mound of laundry, her fingers clutching a garment she was in the middle of folding.

To our American neighbors, we were model immigrants, a poster family. They told us so. My father had a law degree, my mother was on her way to becoming a doctor, and my siblings and I got good grades and always said “please” and “thank you.” We never talked about Lola. Our secret went to the core of who we were and, at least for us kids, who we wanted to be.

After my mother died of leukemia, in 1999, Lola came to live with me in a small town north of Seattle. I had a family, a career, a house in the suburbs—the American dream. And then I had a slave.

At baggage claim in Manila, I unzipped my suitcase to make sure Lola’s ashes were still there. Outside, I inhaled the familiar smell: a thick blend of exhaust and waste, of ocean and sweet fruit and sweat.Early the next morning I found a driver, an affable middle-aged man who went by the nickname “Doods,” and we hit the road in his truck, weaving through traffic. The scene always stunned me. The sheer number of cars and motorcycles and jeepneys. The people weaving between them and moving on the sidewalks in great brown rivers. The street vendors in bare feet trotting alongside cars, hawking cigarettes and cough drops and sacks of boiled peanuts. The child beggars pressing their faces against the windows.

Doods and I were headed to the place where Lola’s story began, up north in the central plains: Tarlac province. Rice country. The home of a cigar-chomping army lieutenant named Tomas Asuncion, my grandfather. The family stories paint Lieutenant Tom as a formidable man given to eccentricity and dark moods, who had lots of land but little money and kept mistresses in separate houses on his property. His wife died giving birth to their only child, my mother. She was raised by a series of utusans, or “people who take commands.”

Slavery has a long history on the islands. Before the Spanish came, islanders enslaved other islanders, usually war captives, criminals, or debtors. Slaves came in different varieties, from warriors who could earn their freedom through valor to household servants who were regarded as property and could be bought and sold or traded. High-status slaves could own low-status slaves, and the low could own the lowliest. Some chose to enter servitude simply to survive: In exchange for their labor, they might be given food, shelter, and protection.

When the Spanish arrived, in the 1500s, they enslaved islanders and later brought African and Indian slaves. The Spanish Crown eventually began phasing out slavery at home and in its colonies, but parts of the Philippines were so far-flung that authorities couldn’t keep a close eye. Traditions persisted under different guises, even after the U.S. took control of the islands in 1898. Today even the poor can have utusans or katulongs (“helpers”) or kasambahays (“domestics”), as long as there are people even poorer. The pool is deep.

Lieutenant Tom had as many as three families of utusans living on his property. In the spring of 1943, with the islands under Japanese occupation, he brought home a girl from a village down the road. She was a cousin from a marginal side of the family, rice farmers. The lieutenant was shrewd—he saw that this girl was penniless, unschooled, and likely to be malleable. Her parents wanted her to marry a pig farmer twice her age, and she was desperately unhappy but had nowhere to go. Tom approached her with an offer: She could have food and shelter if she would commit to taking care of his daughter, who had just turned 12.

Lola agreed, not grasping that the deal was for life.

“She is my gift to you,” Lieutenant Tom told my mother.

“I don’t want her,” my mother said, knowing she had no choice.

Lieutenant Tom went off to fight the Japanese, leaving Mom behind with Lola in his creaky house in the provinces. Lola fed, groomed, and dressed my mother. When they walked to the market, Lola held an umbrella to shield her from the sun. At night, when Lola’s other tasks were done—feeding the dogs, sweeping the floors, folding the laundry that she had washed by hand in the Camiling River—she sat at the edge of my mother’s bed and fanned her to sleep.

One day during the war Lieutenant Tom came home and caught my mother in a lie—something to do with a boy she wasn’t supposed to talk to. Tom, furious, ordered her to “stand at the table.” Mom cowered with Lola in a corner. Then, in a quivering voice, she told her father that Lola would take her punishment. Lola looked at Mom pleadingly, then without a word walked to the dining table and held on to the edge. Tom raised the belt and delivered 12 lashes, punctuating each one with a word. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. You. Do. Not. Lie. To. Me. Lola made no sound.

My mother, in recounting this story late in her life, delighted in the outrageousness of it, her tone seeming to say, Can you believe I did that? When I brought it up with Lola, she asked to hear Mom’s version. She listened intently, eyes lowered, and afterward she looked at me with sadness and said simply, “Yes. It was like that.”

Seven years later, in 1950, Mom married my father and moved to Manila, bringing Lola along. Lieutenant Tom had long been haunted by demons, and in 1951 he silenced them with a .32‑caliber slug to his temple. Mom almost never talked about it. She had his temperament—moody, imperial, secretly fragile—and she took his lessons to heart, among them the proper way to be a provincial matrona: You must embrace your role as the giver of commands. You must keep those beneath you in their place at all times, for their own good and the good of the household. They might cry and complain, but their souls will thank you. They will love you for helping them be what God intended.

My brother Arthur was born in 1951. I came next, followed by three more siblings in rapid succession. My parents expected Lola to be as devoted to us kids as she was to them. While she looked after us, my parents went to school and earned advanced degrees, joining the ranks of so many others with fancy diplomas but no jobs. Then the big break: Dad was offered a job in Foreign Affairs as a commercial analyst. The salary would be meager, but the position was in America—a place he and Mom had grown up dreaming of, where everything they hoped for could come true.

Dad was allowed to bring his family and one domestic. Figuring they would both have to work, my parents needed Lola to care for the kids and the house. My mother informed Lola, and to her great irritation, Lola didn’t immediately acquiesce. Years later Lola told me she was terrified. “It was too far,” she said. “Maybe your Mom and Dad won’t let me go home.”

In the end what convinced Lola was my father’s promise that things would be different in America. He told her that as soon as he and Mom got on their feet, they’d give her an “allowance.” Lola could send money to her parents, to all her relations in the village. Her parents lived in a hut with a dirt floor. Lola could build them a concrete house, could change their lives forever. Imagine.

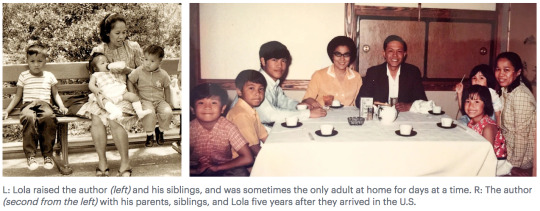

We landed in Los Angeles on May 12, 1964, all our belongings in cardboard boxes tied with rope. Lola had been with my mother for 21 years by then. In many ways she was more of a parent to me than either my mother or my father. Hers was the first face I saw in the morning and the last one I saw at night. As a baby, I uttered Lola’s name (which I first pronounced “Oh-ah”) long before I learned to say “Mom” or “Dad.” As a toddler, I refused to go to sleep unless Lola was holding me, or at least nearby.

I was 4 years old when we arrived in the U.S.—too young to question Lola’s place in our family. But as my siblings and I grew up on this other shore, we came to see the world differently. The leap across the ocean brought about a leap in consciousness that Mom and Dad couldn’t, or wouldn’t, make.

Lola never got that allowance. She asked my parents about it in a roundabout way a couple of years into our life in America. Her mother had fallen ill (with what I would later learn was dysentery), and her family couldn’t afford the medicine she needed. “Pwede ba?” she said to my parents. Is it possible? Mom let out a sigh. “How could you even ask?,” Dad responded in Tagalog. “You see how hard up we are. Don’t you have any shame?”

My parents had borrowed money for the move to the U.S., and then borrowed more in order to stay. My father was transferred from the consulate general in L.A. to the Philippine consulate in Seattle. He was paid $5,600 a year. He took a second job cleaning trailers, and a third as a debt collector. Mom got work as a technician in a couple of medical labs. We barely saw them, and when we did they were often exhausted and snappish.

Mom would come home and upbraid Lola for not cleaning the house well enough or for forgetting to bring in the mail. “Didn’t I tell you I want the letters here when I come home?” she would say in Tagalog, her voice venomous. “It’s not hard naman! An idiot could remember.” Then my father would arrive and take his turn. When Dad raised his voice, everyone in the house shrank. Sometimes my parents would team up until Lola broke down crying, almost as though that was their goal.

It confused me: My parents were good to my siblings and me, and we loved them. But they’d be affectionate to us kids one moment and vile to Lola the next. I was 11 or 12 when I began to see Lola’s situation clearly. By then Arthur, eight years my senior, had been seething for a long time. He was the one who introduced the word slave into my understanding of what Lola was. Before he said it I’d thought of her as just an unfortunate member of the household. I hated when my parents yelled at her, but it hadn’t occurred to me that they—and the whole arrangement—could be immoral.

“Do you know anybody treated the way she’s treated?,” Arthur said. “Who lives the way she lives?” He summed up Lola’s reality: Wasn’t paid. Toiled every day. Was tongue-lashed for sitting too long or falling asleep too early. Was struck for talking back. Wore hand-me-downs. Ate scraps and leftovers by herself in the kitchen. Rarely left the house. Had no friends or hobbies outside the family. Had no private quarters. (Her designated place to sleep in each house we lived in was always whatever was left—a couch or storage area or corner in my sisters’ bedroom. She often slept among piles of laundry.)

We couldn’t identify a parallel anywhere except in slave characters on TV and in the movies. I remember watching a Western called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. John Wayne plays Tom Doniphon, a gunslinging rancher who barks orders at his servant, Pompey, whom he calls his “boy.” Pick him up, Pompey. Pompey, go find the doctor. Get on back to work, Pompey! Docile and obedient, Pompey calls his master “Mistah Tom.” They have a complex relationship. Tom forbids Pompey from attending school but opens the way for Pompey to drink in a whites-only saloon. Near the end, Pompey saves his master from a fire. It’s clear Pompey both fears and loves Tom, and he mourns when Tom dies. All of this is peripheral to the main story of Tom’s showdown with bad guy Liberty Valance, but I couldn’t take my eyes off Pompey. I remember thinking: Lola is Pompey, Pompey is Lola.

One night when Dad found out that my sister Ling, who was then 9, had missed dinner, he barked at Lola for being lazy. “I tried to feed her,” Lola said, as Dad stood over her and glared. Her feeble defense only made him angrier, and he punched her just below the shoulder. Lola ran out of the room and I could hear her wailing, an animal cry.

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said.

My parents turned to look at me. They seemed startled. I felt the twitching in my face that usually preceded tears, but I wouldn’t cry this time. In Mom’s eyes was a shadow of something I hadn’t seen before. Jealousy?

“Are you defending your Lola?,” Dad said. “Is that what you’re doing?”

“Ling said she wasn’t hungry,” I said again, almost in a whisper.

I was 13. It was my first attempt to stick up for the woman who spent her days watching over me. The woman who used to hum Tagalog melodies as she rocked me to sleep, and when I got older would dress and feed me and walk me to school in the mornings and pick me up in the afternoons. Once, when I was sick for a long time and too weak to eat, she chewed my food for me and put the small pieces in my mouth to swallow. One summer when I had plaster casts on both legs (I had problem joints), she bathed me with a washcloth, brought medicine in the middle of the night, and helped me through months of rehabilitation. I was cranky through it all. She didn’t complain or lose patience, ever.

To now hear her wailing made me crazy.

In the old country, my parents felt no need to hide their treatment of Lola. In America, they treated her worse but took pains to conceal it. When guests came over, my parents would either ignore her or, if questioned, lie and quickly change the subject. For five years in North Seattle, we lived across the street from the Misslers, a rambunctious family of eight who introduced us to things like mustard, salmon fishing, and mowing the lawn. Football on TV. Yelling during football. Lola would come out to serve food and drinks during games, and my parents would smile and thank her before she quickly disappeared. “Who’s that little lady you keep in the kitchen?,” Big Jim, the Missler patriarch, once asked. A relative from back home, Dad said. Very shy.

Billy Missler, my best friend, didn’t buy it. He spent enough time at our house, whole weekends sometimes, to catch glimpses of my family’s secret. He once overheard my mother yelling in the kitchen, and when he barged in to investigate found Mom red-faced and glaring at Lola, who was quaking in a corner. I came in a few seconds later. The look on Billy’s face was a mix of embarrassment and perplexity. What was that? I waved it off and told him to forget it.

I think Billy felt sorry for Lola. He’d rave about her cooking, and make her laugh like I’d never seen. During sleepovers, she’d make his favorite Filipino dish, beef tapa over white rice. Cooking was Lola’s only eloquence. I could tell by what she served whether she was merely feeding us or saying she loved us.

When I once referred to Lola as a distant aunt, Billy reminded me that when we’d first met I’d said she was my grandmother.

“Well, she’s kind of both,” I said mysteriously.

“Why is she always working?”

“She likes to work,” I said.

“Your dad and mom—why do they yell at her?”

“Her hearing isn’t so good …”

Admitting the truth would have meant exposing us all. We spent our first decade in the country learning the ways of the new land and trying to fit in. Having a slave did not fit. Having a slave gave me grave doubts about what kind of people we were, what kind of place we came from. Whether we deserved to be accepted. I was ashamed of it all, including my complicity. Didn’t I eat the food she cooked, and wear the clothes she washed and ironed and hung in the closet? But losing her would have been devastating.

There was another reason for secrecy: Lola’s travel papers had expired in 1969, five years after we arrived in the U.S. She’d come on a special passport linked to my father’s job. After a series of fallings-out with his superiors, Dad quit the consulate and declared his intent to stay in the United States. He arranged for permanent-resident status for his family, but Lola wasn’t eligible. He was supposed to send her back.

Lola’s mother, Fermina, died in 1973; her father, Hilario, in 1979. Both times she wanted desperately to go home. Both times my parents said “Sorry.” No money, no time. The kids needed her. My parents also feared for themselves, they admitted to me later. If the authorities had found out about Lola, as they surely would have if she’d tried to leave, my parents could have gotten into trouble, possibly even been deported. They couldn’t risk it. Lola’s legal status became what Filipinos call tago nang tago, or TNT—“on the run.” She stayed TNT for almost 20 years.

After each of her parents died, Lola was sullen and silent for months. She barely responded when my parents badgered her. But the badgering never let up. Lola kept her head down and did her work.

My father’s resignation started a turbulent period. Money got tighter, and my parents turned on each other. They uprooted the family again and again—Seattle to Honolulu back to Seattle to the southeast Bronx and finally to the truck-stop town of Umatilla, Oregon, population 750. During all this moving around, Mom often worked 24-hour shifts, first as a medical intern and then as a resident, and Dad would disappear for days, working odd jobs but also (we’d later learn) womanizing and who knows what else. Once, he came home and told us that he’d lost our new station wagon playing blackjack.

For days in a row Lola would be the only adult in the house. She got to know the details of our lives in a way that my parents never had the mental space for. We brought friends home, and she’d listen to us talk about school and girls and boys and whatever else was on our minds. Just from conversations she overheard, she could list the first name of every girl I had a crush on from sixth grade through high school.

When I was 15, Dad left the family for good. I didn’t want to believe it at the time, but the fact was that he deserted us kids and abandoned Mom after 25 years of marriage. She wouldn’t become a licensed physician for another year, and her specialty—internal medicine—wasn’t especially lucrative. Dad didn’t pay child support, so money was always a struggle.

My mom kept herself together enough to go to work, but at night she’d crumble in self-pity and despair. Her main source of comfort during this time: Lola. As Mom snapped at her over small things, Lola attended to her even more—cooking Mom’s favorite meals, cleaning her bedroom with extra care. I’d find the two of them late at night at the kitchen counter, griping and telling stories about Dad, sometimes laughing wickedly, other times working themselves into a fury over his transgressions. They barely noticed us kids flitting in and out.

One night I heard Mom weeping and ran into the living room to find her slumped in Lola’s arms. Lola was talking softly to her, the way she used to with my siblings and me when we were young. I lingered, then went back to my room, scared for my mom and awed by Lola.

Doods was humming. I’d dozed for what felt like a minute and awoke to his happy melody. “Two hours more,” he said. I checked the plastic box in the tote bag by my side—still there—and looked up to see open road. The MacArthur Highway. I glanced at the time. “Hey, you said ‘two hours’ two hours ago,” I said. Doods just hummed.

His not knowing anything about the purpose of my journey was a relief. I had enough interior dialogue going on. I was no better than my parents. I could have done more to free Lola. To make her life better. Why didn’t I? I could have turned in my parents, I suppose. It would have blown up my family in an instant. Instead, my siblings and I kept everything to ourselves, and rather than blowing up in an instant, my family broke apart slowly.

Doods and I passed through beautiful country. Not travel-brochure beautiful but real and alive and, compared with the city, elegantly spare. Mountains ran parallel to the highway on each side, the Zambales Mountains to the west, the Sierra Madre Range to the east. From ridge to ridge, west to east, I could see every shade of green all the way to almost black.

Doods pointed to a shadowy outline in the distance. Mount Pinatubo. I’d come here in 1991 to report on the aftermath of its eruption, the second-largest of the 20th century. Volcanic mudflows called lahars continued for more than a decade, burying ancient villages, filling in rivers and valleys, and wiping out entire ecosystems. The lahars reached deep into the foothills of Tarlac province, where Lola’s parents had spent their entire lives, and where she and my mother had once lived together. So much of our family record had been lost in wars and floods, and now parts were buried under 20 feet of mud.

Life here is routinely visited by cataclysm. Killer typhoons that strike several times a year. Bandit insurgencies that never end. Somnolent mountains that one day decide to wake up. The Philippines isn’t like China or Brazil, whose mass might absorb the trauma. This is a nation of scattered rocks in the sea. When disaster hits, the place goes under for a while. Then it resurfaces and life proceeds, and you can behold a scene like the one Doods and I were driving through, and the simple fact that it’s still there makes it beautiful.

A couple of years after my parents split, my mother remarried and demanded Lola’s fealty to her new husband, a Croatian immigrant named Ivan, whom she had met through a friend. Ivan had never finished high school. He’d been married four times and was an inveterate gambler who enjoyed being supported by my mother and attended to by Lola.

Ivan brought out a side of Lola I’d never seen. His marriage to my mother was volatile from the start, and money—especially his use of her money—was the main issue. Once, during an argument in which Mom was crying and Ivan was yelling, Lola walked over and stood between them. She turned to Ivan and firmly said his name. He looked at Lola, blinked, and sat down.

My sister Inday and I were floored. Ivan was about 250 pounds, and his baritone could shake the walls. Lola put him in his place with a single word. I saw this happen a few other times, but for the most part Lola served Ivan unquestioningly, just as Mom wanted her to. I had a hard time watching Lola vassalize herself to another person, especially someone like Ivan. But what set the stage for my blowup with Mom was something more mundane.

She used to get angry whenever Lola felt ill. She didn’t want to deal with the disruption and the expense, and would accuse Lola of faking or failing to take care of herself. Mom chose the second tack when, in the late 1970s, Lola’s teeth started falling out. She’d been saying for months that her mouth hurt.

“That’s what happens when you don’t brush properly,” Mom told her.

I said that Lola needed to see a dentist. She was in her 50s and had never been to one. I was attending college an hour away, and I brought it up again and again on my frequent trips home. A year went by, then two. Lola took aspirin every day for the pain, and her teeth looked like a crumbling Stonehenge. One night, after watching her chew bread on the side of her mouth that still had a few good molars, I lost it.

Mom and I argued into the night, each of us sobbing at different points. She said she was tired of working her fingers to the bone supporting everybody, and sick of her children always taking Lola’s side, and why didn’t we just take our goddamn Lola, she’d never wanted her in the first place, and she wished to God she hadn’t given birth to an arrogant, sanctimonious phony like me.

I let her words sink in. Then I came back at her, saying she would know all about being a phony, her whole life was a masquerade, and if she stopped feeling sorry for herself for one minute she’d see that Lola could barely eat because her goddamn teeth were rotting out of her goddamn head, and couldn’t she think of her just this once as a real person instead of a slave kept alive to serve her?

“A slave,” Mom said, weighing the word. “A slave?”

The night ended when she declared that I would never understand her relationship with Lola. Never. Her voice was so guttural and pained that thinking of it even now, so many years later, feels like a punch to the stomach. It’s a terrible thing to hate your own mother, and that night I did. The look in her eyes made clear that she felt the same way about me.

The fight only fed Mom’s fear that Lola had stolen the kids from her, and she made Lola pay for it. Mom drove her harder. Tormented her by saying, “I hope you’re happy now that your kids hate me.” When we helped Lola with housework, Mom would fume. “You’d better go to sleep now, Lola,” she’d say sarcastically. “You’ve been working too hard. Your kids are worried about you.” Later she’d take Lola into a bedroom for a talk, and Lola would walk out with puffy eyes.

Lola finally begged us to stop trying to help her.

Why do you stay? we asked.

“Who will cook?” she said, which I took to mean, Who would do everything? Who would take care of us? Of Mom? Another time she said, “Where will I go?” This struck me as closer to a real answer. Coming to America had been a mad dash, and before we caught a breath a decade had gone by. We turned around, and a second decade was closing out. Lola’s hair had turned gray. She’d heard that relatives back home who hadn’t received the promised support were wondering what had happened to her. She was ashamed to return.

She had no contacts in America, and no facility for getting around. Phones puzzled her. Mechanical things—ATMs, intercoms, vending machines, anything with a keyboard—made her panic. Fast-talking people left her speechless, and her own broken English did the same to them. She couldn’t make an appointment, arrange a trip, fill out a form, or order a meal without help.

I got Lola an ATM card linked to my bank account and taught her how to use it. She succeeded once, but the second time she got flustered, and she never tried again. She kept the card because she considered it a gift from me.

I also tried to teach her to drive. She dismissed the idea with a wave of her hand, but I picked her up and carried her to the car and planted her in the driver’s seat, both of us laughing. I spent 20 minutes going over the controls and gauges. Her eyes went from mirthful to terrified. When I turned on the ignition and the dashboard lit up, she was out of the car and in the house before I could say another word. I tried a couple more times.

I thought driving could change her life. She could go places. And if things ever got unbearable with Mom, she could drive away forever.

Four lanes became two, pavement turned to gravel. Tricycle drivers wove between cars and water buffalo pulling loads of bamboo. An occasional dog or goat sprinted across the road in front of our truck, almost grazing the bumper. Doods never eased up. Whatever didn’t make it across would be stew today instead of tomorrow—the rule of the road in the provinces.

I took out a map and traced the route to the village of Mayantoc, our destination. Out the window, in the distance, tiny figures folded at the waist like so many bent nails. People harvesting rice, the same way they had for thousands of years. We were getting close.

I tapped the cheap plastic box and regretted not buying a real urn, made of porcelain or rosewood. What would Lola’s people think? Not that many were left. Only one sibling remained in the area, Gregoria, 98 years old, and I was told her memory was failing. Relatives said that whenever she heard Lola’s name, she’d burst out crying and then quickly forget why.

I’d been in touch with one of Lola’s nieces. She had the day planned: When I arrived, a low-key memorial, then a prayer, followed by the lowering of the ashes into a plot at the Mayantoc Eternal Bliss Memorial Park. It had been five years since Lola died, but I hadn’t yet said the final goodbye that I knew was about to happen. All day I had been feeling intense grief and resisting the urge to let it out, not wanting to wail in front of Doods. More than the shame I felt for the way my family had treated Lola, more than my anxiety about how her relatives in Mayantoc would treat me, I felt the terrible heaviness of losing her, as if she had died only the day before.

Doods veered northwest on the Romulo Highway, then took a sharp left at Camiling, the town Mom and Lieutenant Tom came from. Two lanes became one, then gravel turned to dirt. The path ran along the Camiling River, clusters of bamboo houses off to the side, green hills ahead. The homestretch.

I gave the eulogy at Mom’s funeral, and everything I said was true. That she was brave and spirited. That she’d drawn some short straws, but had done the best she could. That she was radiant when she was happy. That she adored her children, and gave us a real home—in Salem, Oregon—that through the ’80s and ’90s became the permanent base we’d never had before. That I wished we could thank her one more time. That we all loved her.

I didn’t talk about Lola. Just as I had selectively blocked Lola out of my mind when I was with Mom during her last years. Loving my mother required that kind of mental surgery. It was the only way we could be mother and son—which I wanted, especially after her health started to decline, in the mid‑’90s. Diabetes. Breast cancer. Acute myelogenous leukemia, a fast-growing cancer of the blood and bone marrow. She went from robust to frail seemingly overnight.

After the big fight, I mostly avoided going home, and at age 23 I moved to Seattle. When I did visit I saw a change. Mom was still Mom, but not as relentlessly. She got Lola a fine set of dentures and let her have her own bedroom. She cooperated when my siblings and I set out to change Lola’s TNT status. Ronald Reagan’s landmark immigration bill of 1986 made millions of illegal immigrants eligible for amnesty. It was a long process, but Lola became a citizen in October 1998, four months after my mother was diagnosed with leukemia. Mom lived another year.

During that time, she and Ivan took trips to Lincoln City, on the Oregon coast, and sometimes brought Lola along. Lola loved the ocean. On the other side were the islands she dreamed of returning to. And Lola was never happier than when Mom relaxed around her. An afternoon at the coast or just 15 minutes in the kitchen reminiscing about the old days in the province, and Lola would seem to forget years of torment.

I couldn’t forget so easily. But I did come to see Mom in a different light. Before she died, she gave me her journals, two steamer trunks’ full. Leafing through them as she slept a few feet away, I glimpsed slices of her life that I’d refused to see for years. She’d gone to medical school when not many women did. She’d come to America and fought for respect as both a woman and an immigrant physician. She’d worked for two decades at Fairview Training Center, in Salem, a state institution for the developmentally disabled. The irony: She tended to underdogs most of her professional life. They worshipped her. Female colleagues became close friends. They did silly, girly things together—shoe shopping, throwing dress-up parties at one another’s homes, exchanging gag gifts like penis-shaped soaps and calendars of half-naked men, all while laughing hysterically. Looking through their party pictures reminded me that Mom had a life and an identity apart from the family and Lola. Of course.

Mom wrote in great detail about each of her kids, and how she felt about us on a given day—proud or loving or resentful. And she devoted volumes to her husbands, trying to grasp them as complex characters in her story. We were all persons of consequence. Lola was incidental. When she was mentioned at all, she was a bit character in someone else’s story. “Lola walked my beloved Alex to his new school this morning. I hope he makes new friends quickly so he doesn’t feel so sad about moving again …” There might be two more pages about me, and no other mention of Lola.

The day before Mom died, a Catholic priest came to the house to perform last rites. Lola sat next to my mother’s bed, holding a cup with a straw, poised to raise it to Mom’s mouth. She had become extra attentive to my mother, and extra kind. She could have taken advantage of Mom in her feebleness, even exacted revenge, but she did the opposite.

The priest asked Mom whether there was anything she wanted to forgive or be forgiven for. She scanned the room with heavy-lidded eyes, said nothing. Then, without looking at Lola, she reached over and placed an open hand on her head. She didn’t say a word.

Lola was 75 when she came to stay with me. I was married with two young daughters, living in a cozy house on a wooded lot. From the second story, we could see Puget Sound. We gave Lola a bedroom and license to do whatever she wanted: sleep in, watch soaps, do nothing all day. She could relax—and be free—for the first time in her life. I should have known it wouldn’t be that simple.

I’d forgotten about all the things Lola did that drove me a little crazy. She was always telling me to put on a sweater so I wouldn’t catch a cold (I was in my 40s). She groused incessantly about Dad and Ivan: My father was lazy, Ivan was a leech. I learned to tune her out. Harder to ignore was her fanatical thriftiness. She threw nothing out. And she used to go through the trash to make sure that the rest of us hadn’t thrown out anything useful. She washed and reused paper towels again and again until they disintegrated in her hands. (No one else would go near them.) The kitchen became glutted with grocery bags, yogurt containers, and pickle jars, and parts of our house turned into storage for—there’s no other word for it—garbage.

She cooked breakfast even though none of us ate more than a banana or a granola bar in the morning, usually while we were running out the door. She made our beds and did our laundry. She cleaned the house. I found myself saying to her, nicely at first, “Lola, you don’t have to do that.” “Lola, we’ll do it ourselves.” “Lola, that’s the girls’ job.” Okay, she’d say, but keep right on doing it.

It irritated me to catch her eating meals standing in the kitchen, or see her tense up and start cleaning when I walked into the room. One day, after several months, I sat her down.

“I’m not Dad. You’re not a slave here,” I said, and went through a long list of slavelike things she’d been doing. When I realized she was startled, I took a deep breath and cupped her face, that elfin face now looking at me searchingly. I kissed her forehead. “This is your house now,” I said. “You’re not here to serve us. You can relax, okay?”

“Okay,” she said. And went back to cleaning.

She didn’t know any other way to be. I realized I had to take my own advice and relax. If she wanted to make dinner, let her. Thank her and do the dishes. I had to remind myself constantly: Let her be.

One night I came home to find her sitting on the couch doing a word puzzle, her feet up, the TV on. Next to her, a cup of tea. She glanced at me, smiled sheepishly with those perfect white dentures, and went back to the puzzle. Progress, I thought.

She planted a garden in the backyard—roses and tulips and every kind of orchid—and spent whole afternoons tending it. She took walks around the neighborhood. At about 80, her arthritis got bad and she began walking with a cane. In the kitchen she went from being a fry cook to a kind of artisanal chef who created only when the spirit moved her. She made lavish meals and grinned with pleasure as we devoured them.

Passing the door of Lola’s bedroom, I’d often hear her listening to a cassette of Filipino folk songs. The same tape over and over. I knew she’d been sending almost all her money—my wife and I gave her $200 a week—to relatives back home. One afternoon, I found her sitting on the back deck gazing at a snapshot someone had sent of her village.

“You want to go home, Lola?”

She turned the photograph over and traced her finger across the inscription, then flipped it back and seemed to study a single detail.

“Yes,” she said.

Just after her 83rd birthday, I paid her airfare to go home. I’d follow a month later to bring her back to the U.S.—if she wanted to return. The unspoken purpose of her trip was to see whether the place she had spent so many years longing for could still feel like home.

She found her answer.

“Everything was not the same,” she told me as we walked around Mayantoc. The old farms were gone. Her house was gone. Her parents and most of her siblings were gone. Childhood friends, the ones still alive, were like strangers. It was nice to see them, but … everything was not the same. She’d still like to spend her last years here, she said, but she wasn’t ready yet.

“You’re ready to go back to your garden,” I said.

“Yes. Let’s go home.”

Lola was as devoted to my daughters as she’d been to my siblings and me when we were young. After school, she’d listen to their stories and make them something to eat. And unlike my wife and me (especially me), Lola enjoyed every minute of every school event and performance. She couldn’t get enough of them. She sat up front, kept the programs as mementos.

It was so easy to make Lola happy. We took her on family vacations, but she was as excited to go to the farmer’s market down the hill. She became a wide-eyed kid on a field trip: “Look at those zucchinis!” The first thing she did every morning was open all the blinds in the house, and at each window she’d pause to look outside.

And she taught herself to read. It was remarkable. Over the years, she’d somehow learned to sound out letters. She did those puzzles where you find and circle words within a block of letters. Her room had stacks of word-puzzle booklets, thousands of words circled in pencil. Every day she watched the news and listened for words she recognized. She triangulated them with words in the newspaper, and figured out the meanings. She came to read the paper every day, front to back. Dad used to say she was simple. I wondered what she could have been if, instead of working the rice fields at age 8, she had learned to read and write.

During the 12 years she lived in our house, I asked her questions about herself, trying to piece together her life story, a habit she found curious. To my inquiries she would often respond first with “Why?” Why did I want to know about her childhood? About how she met Lieutenant Tom?

I tried to get my sister Ling to ask Lola about her love life, thinking Lola would be more comfortable with her. Ling cackled, which was her way of saying I was on my own. One day, while Lola and I were putting away groceries, I just blurted it out: “Lola, have you ever been romantic with anyone?” She smiled, and then she told me the story of the only time she’d come close. She was about 15, and there was a handsome boy named Pedro from a nearby farm. For several months they harvested rice together side by side. One time, she dropped her bolo—a cutting implement—and he quickly picked it up and handed it back to her. “I liked him,” she said.

Silence.

“And?”

“Then he moved away,” she said.

“And?”

“That’s all.”

“Lola, have you ever had sex?,” I heard myself saying.

“No,” she said.

She wasn’t accustomed to being asked personal questions. “Katulong lang ako,” she’d say. I’m only a servant. She often gave one- or two-word answers, and teasing out even the simplest story was a game of 20 questions that could last days or weeks.

Some of what I learned: She was mad at Mom for being so cruel all those years, but she nevertheless missed her. Sometimes, when Lola was young, she’d felt so lonely that all she could do was cry. I knew there were years when she’d dreamed of being with a man. I saw it in the way she wrapped herself around one large pillow at night. But what she told me in her old age was that living with Mom’s husbands made her think being alone wasn’t so bad. She didn’t miss those two at all. Maybe her life would have been better if she’d stayed in Mayantoc, gotten married, and had a family like her siblings. But maybe it would have been worse. Two younger sisters, Francisca and Zepriana, got sick and died. A brother, Claudio, was killed. What’s the point of wondering about it now? she asked. Bahala na was her guiding principle. Come what may. What came her way was another kind of family. In that family, she had eight children: Mom, my four siblings and me, and now my two daughters. The eight of us, she said, made her life worth living.

None of us was prepared for her to die so suddenly.

Her heart attack started in the kitchen while she was making dinner and I was running an errand. When I returned she was in the middle of it. A couple of hours later at the hospital, before I could grasp what was happening, she was gone—10:56 p.m. All the kids and grandkids noted, but were unsure how to take, that she died on November 7, the same day as Mom. Twelve years apart.

Lola made it to 86. I can still see her on the gurney. I remember looking at the medics standing above this brown woman no bigger than a child and thinking that they had no idea of the life she had lived. She’d had none of the self-serving ambition that drives most of us, and her willingness to give up everything for the people around her won her our love and utter loyalty. She’s become a hallowed figure in my extended family.

Going through her boxes in the attic took me months. I found recipes she had cut out of magazines in the 1970s for when she would someday learn to read. Photo albums with pictures of my mom. Awards my siblings and I had won from grade school on, most of which we had thrown away and she had “saved.” I almost lost it one night when at the bottom of a box I found a stack of yellowed newspaper articles I’d written and long ago forgotten about. She couldn’t read back then, but she’d kept them anyway.

Doods’s truck pulled up to a small concrete house in the middle of a cluster of homes mostly made of bamboo and plank wood. Surrounding the pod of houses: rice fields, green and seemingly endless. Before I even got out of the truck, people started coming outside.

Doods reclined his seat to take a nap. I hung my tote bag on my shoulder, took a breath, and opened the door.

“This way,” a soft voice said, and I was led up a short walkway to the concrete house. Following close behind was a line of about 20 people, young and old, but mostly old. Once we were all inside, they sat down on chairs and benches arranged along the walls, leaving the middle of the room empty except for me. I remained standing, waiting to meet my host. It was a small room, and dark. People glanced at me expectantly.“

Where is Lola?” A voice from another room. The next moment, a middle-aged woman in a housedress sauntered in with a smile. Ebia, Lola’s niece. This was her house. She gave me a hug and said again, “Where is Lola?”

I slid the tote bag from my shoulder and handed it to her. She looked into my face, still smiling, gently grasped the bag, and walked over to a wooden bench and sat down. She reached inside and pulled out the box and looked at every side. “Where is Lola?” she said softly. People in these parts don’t often get their loved ones cremated. I don’t think she knew what to expect. She set the box on her lap and bent over so her forehead rested on top of it, and at first I thought she was laughing (out of joy) but I quickly realized she was crying. Her shoulders began to heave, and then she was wailing—a deep, mournful, animal howl, like I once heard coming from Lola.

I hadn’t come sooner to deliver Lola’s ashes in part because I wasn’t sure anyone here cared that much about her. I hadn’t expected this kind of grief. Before I could comfort Ebia, a woman walked in from the kitchen and wrapped her arms around her, and then she began wailing. The next thing I knew, the room erupted with sound. The old people—one of them blind, several with no teeth—were all crying and not holding anything back. It lasted about 10 minutes. I was so fascinated that I barely noticed the tears running down my own face. The sobs died down, and then it was quiet again.

Ebia sniffled and said it was time to eat. Everybody started filing into the kitchen, puffy-eyed but suddenly lighter and ready to tell stories. I glanced at the empty tote bag on the bench, and knew it was right to bring Lola back to the place where she’d been born.

----------

Alex Tizon was a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and the author of Big Little Man: In Search of My Asian Self. This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of The Atlantic and needless to say it was difficult to hold back the tears while reading this incredibly moving piece.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This iteration of Best Nonrequired looks exceptional, edited by Sheila Heti: an extended Kara Walker artist’s statement, a Hanif Abdurraqib excerpt from They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, the Tizon piece from The Atlantic on his "family’s slave”, and from Roxanne Gay’s Hunger. Heti edited in collaboration with high school students in the 826 National program, and the documentation of their work together is pretty enlightening too.

#best american nonrequired reading 2018#sheila heti#kara walker#hanif abdurraqib#roxanne gay#alex tizon#826 national

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist’s memoir—an intimate look at the mythology, experience, and psyche of the Asian American male—including an extraordinary posthumous coda, “My Family’s Slave”

“A ruthlessly honest personal story and a devastating critique of contemporary American culture.” —Seattle Times

Shame, Alex Tizon tells us, is universal—his own happened to be about race. To counteract the steady diet of American television and movies that taught Tizon to be ashamed of his face, his skin color, his height, he turned outward. (“I had to educate myself on my own worth. It was a sloppy, piecemeal education, but I had to do it because no one else was going to do it for me.”) Tizon illuminates his youthful search for Asian men who had no place in his American history books or classrooms. And he tracks what he experienced as seismic change: the rise of powerful, dynamic Asian men like Yahoo! cofounder Jerry Yang, actor Ken Watanabe, and NBA starter Jeremy Lin.

Included in this new edition of Big Little Man is Alex Tizon’s “My Family’s Slave”—2017’s best-read digital article. Published only weeks after Tizon’s death in 2017, it delivers a provocative, haunting, and ultimately redemptive coda.

“Alex Tizon writes with acumen and courage, and the result is a book at once illuminating and, yes, liberating.” —Peter Ho Davies, author of The Fortunes

ALEX TIZON, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, was former Seattle bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, and longtime staff writer for the Seattle Times. He coproduced a 60 Minutes segment on Third World mail-order brides in Asia, and taught at the University of Oregon. Big Little Man was the winner of the prestigious Work in Progress Prize from the J. Anthony Lukas Prize Project.

Buy here | Indiebound | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | iBooks | Kobo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s 2017 and the phrase “Slavery is wrong, no matter what the circumstances” is actually controversial. Good to know you guys all support owning another human being.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m still fucked up over the fact that some guy is being commended for having written a navel-gazing thinkpiece about how he inherited his family’s slave. He could have freed her, let her go back to live with her family in the Philippines, but nope. He waited until she died, took her ashes back to her relatives, and then made the front cover of the Atlantic by “telling her story,” i.e., telling his perspective on how she was physically and emotionally consumed and discarded by others, his guilt and anxiety about her mistreatment, his failure to make anything but small, futile gestures towards recognizing her humanity.

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

If you’re wondering why all your Filipino friends are especially introspective and/or devastated today, this may be the reason why.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing all this stuff about the Alex Tizon discourse is making me wanna throw up.

Listen. What they did? It’s slavery. We know. We get it. But it’s not your slavery, it is a product of the broken system which we have been mired in, one which America has been directly complicit in. It’s an unfortunate case, horrifying, not entirely unexpected, but not exactly the norm. The issue here is that foreigners are trying to put words in our mouth and making this discussion about them instead of letting Filipinos process this and have a proper conversation about it without them shutting us down and screaming BUT SLAVERY!!! APOLOGISTS!!! not only that but they’re deliberately misunderstanding our language and honorifics, they are making things out to be something they’re not.

The system is broken. Any Filipino can tell you that. Yelling at us isn’t going to fix it unless you can somehow fix an entire culture with a press of a button and magically remove 400 years of colonialism and oppression, both by foreigners and fellow Filipinos, which has directly contributed to how desperate and helpless our people have become. It just doesn’t work that way.

But what really pisses me off about this? It’s because we’ve already been silenced before. We have been colonized, mistreated, our culture erased and labeled as inferior, our country gutted for resources and labor and this is still happening, just now its happening on more socially acceptable terms.

Context and the underlying culture does matter, especially when our culture has already been so abused and erased that we have no idea what kind of culture or history we would have had if it hadn’t been beaten out of us by colonizers for 400 years, even the name of our country, our very identity. To this day we still struggle with our identity as a people, with the colonial mentality and nation-wide inferiority complex instilled in us by colonizers.

Keep in mind that every time you yell at us about how culture doesn’t matter, you’re all slavery apologists, without taking into consideration our views, our culture and the system which contributes to this, and how people are still working to correct it despite the fact that progress will likely not come for another 20? 30? years maybe even longer. Progress is slow when you live in a country where every system is designed against you. We are seeing people from a country which oppressed us, attempting to once again erase our narrative and tell us they know better, perhaps then you can forgive us for being wary of foreigners dismissing our culture and views to propagate their own.

#i didnt want rant but this keeps bugging me#stop erasing our story#alex tizon#my family's slave#you guys would be pissed if someone stepped in and put words in your mouth#so at least understand where some of this anger is coming from#i could go on about filipino family dynamics but honestly im out of steam#maybe later#i think theres lots of other posts out there that explain it quite well#so you can go look those up

738 notes

·

View notes

Text

real talk

I told this one American-POC who wouldn’t stop harassing Filipinos about slavery to start helping. Since she was so passionate about the issue I figured Hey! Arguing over 2 dead people wont change the fact that so many Filipino women like Eudocia are still suffering right now!

I asked her to help me spread the message on different NGOs who are actively helping in saving these women. And what did she do?

Shut me down. Accuse me of asking for “free labor” (because donations are free labor now?).

And then I get it. Some of you don’t REALLY care about us or this issue. All you care about is lashing out in public, showing how your American-centric morals makes you a better human than people from 3rd world countries.

You deny to listen to our voices because we are beneath you. You feel accomplished that you enforced your U.S.-centric worldview to other countries because in your American eyes YOU ARE RIGHT. But you won’t REALLY do anything about it.

Even if you are a POC, remember that you still have AMERICAN privilege. White people can never understand the black experience, and Americans can never understand the Filipino experience. The only way to resolve this is to LISTEN AND ACTUALLY HELP EXISTING VICTIMS. WHICH YOU ARE NOT DOING.

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

so when the ny times reports about duterte being practically responsible for over 7k random deaths in one year, in metro manila alone i might add, y’all r silent af

but one guy decides to write about his (again, very EXTREME) lifelong experience with his house help in the atlantic and suddenly y’all are up in arms???? suddenly the philippines is a relevant country and u suddenly KNOW EVERYTHING about what goes on here???