#albigensian crusade

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Death of Simon de Monfort by Ramon Acedo

#simon de monfort#siege of toulouse#art#ramon acedo#albigensian crusade#toulouse#medieval#middle ages#crusades#crusaders#knights#knight#crusade#crusader#history#cathar#cathars#languedoc#occitania#occitanie#france#europe#european#heraldry#mangonel#stone#despertaferro magazine#ramón acedo

551 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1209 CE, in response to the perceived presence of "Cathar" heretics, the city of Beziers in the county of Toulouse was sacked. This attack marks the beginning of the 20-year-long 'Albigensian Crusade'

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

"There's nothing left for you here"

A little experimental doodle.

#my art#artists on tumblr#ink#alcohol markers#traditional art#trencavel#albigensian crusade#knightcore#medieval aesthetic#dreamcore#haireomai#ghostcore#pastelcore#doodle#イラスト#オリジナル#アナログ#languedoc#13th century#ruins

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Albigensian Crusade.

#royaume de france#capétiens#louis viii#roi de france#vive le roi#crusades#crusader#kingdom of france#capetians#Albigensian Crusade#royalry#Croisade des albigeois#cathar crusade#croisade contre les albigeois

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The crusade against the Albigensians, 13th century.

by @LegendesCarto

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do the King of France and the Pope consider the Cathar’s to be such a threat that they needed to mount a crusader to exterminate them? Weren’t they a pacifist group?

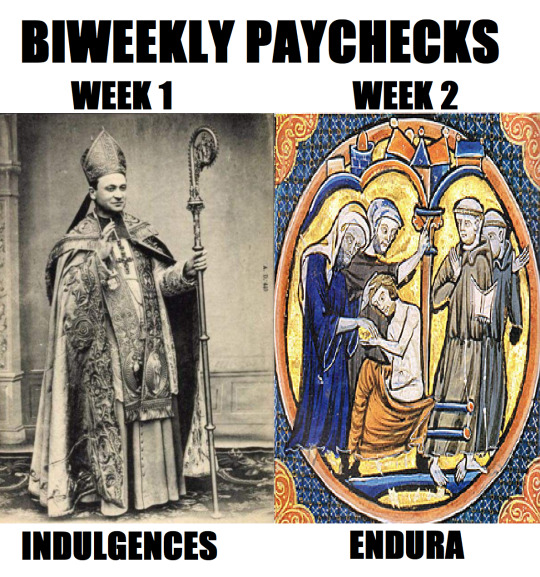

Like most anti-heretical movements of Christianity, it was primarily regarding doctrinal orthodoxy, but also their rejection of all forms of physical authority both temporal and spiritual. The Catharis were inspired by Gnosticism, and so the physical world was impure, and Jesus was an angel in a phantom body that only appeared human (similar to Docetism). They also rejected civil authority as it was subjugation by the physical, which was impure, and so ticked off secular leaders something fierce. They preached a universal priesthood, incorporated reincarnation into their belief structure, and so on.

Thanks for the question, Anon.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Albigensian Crusade is one of the more important and the more neglected wars of the medieval era:

This book serves as a companion to the other book on the Occitan War (that conveniently skipped over the bits with the two French kings providing the first steps to the territorial linkage of what's now southern France with the northern part). That book opened and rightly so the idea of examining the concept of heresy based on actual evidence.....and yet even it has to concede that there was a select group of elites who had a kind of Gnostic aspect to their appeal and most bluntly rejected entirely the authority of the Pope and the bishops. This, more than anything else, was the real seed of the heresy and of the bloodthirsty war that followed.

In the annals of Crusading the Albigensian Crusade rivals that of the Northern Crusades for often being overlooked and yet for being one of the most revealing examples. In a sequence of bloody battles and sieges the so-called Cathars were brought to heel and then exterminated by the rise of the medieval Inquisition, which did not target witches but heretics and Jewish people at that time.

In the annals, too, of medieval civilization the Albigensian Crusade marks like the Northern Crusades a point of transition, where older entities ground against the first steps of what history would show were new paths. The establishment of a French monarchy that ruled more of France than the King of England did, the first of the many steps to imploding the various languages and cultures in the soft genocidal policies of the French state that rendered those languages and cultures all but extinct.

This war also points to the reality that medieval Crusades were international enterprises by the standard of the time in theory but in practice in Europe itself were neatly folded into statebuilding in all its unholy and bloodstained paths. There is no bloodless rise of the state, only a set of choices of very specific horrors.

And it's almost an ironic afterthought that the most famous leader of this crusade would be overshadowed by his son Simon de Montfort of the same name, the man who was a prototype of Oliver Cromwell in the eyes of Whig historians and in reality every bit the avid empire and statebuilder his father was with shorter successes and mostly a bloodied speedbump in the career of Edward I Longshanks, the warrior-king who for a time virtually united Britain until his son took over and wrecked his successes by incompetence.

7/10.

#lightdancer comments on history#book reviews#european history#medieval history#albigensian crusade#aka the 'kill them all for God will know his own' war#no the man who was said to have said that did not technically say it#but it was an entirely believable thing that he did given his writings to the Pope#it's in the same category as 'death solves all problems no man no problem' attributed to Stalin

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Albigensian Crusade and the Cathars

The Cathars were an interesting bunch. They believed that while God had been a creator, they believed too that Satan had been. Satan, in Catharism, created all the material and physical aspects of the world. God, on the other hand, took on the creation of all things spiritual (Cartwright). This separation explained the presence of evil in the world. “Humanity must, as a consequence of this evil, find a way to escape their material bodies and join the pure Good of the spiritual world” (Cartwright). This idea created a duality in the creation story not present in the actual Bible. It also changed the act of man’s fall. It implied that there were many humans at first. “The devil seduced the souls of those in heaven and ripped a hole open to hell, promising for those who followed the freedom from God and many other great pleasures and boons. Many followed and instead were trapped in bodies” (Mark). Thus God’s creations were bound to Satan’s creations. One could only return to the Kingdom of Heaven once one had fully renounced Satan’s earthly pleasures.

This was a fairly unpopular position to take, to say the least, as this separation made it so that Cathars also did not believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ. In fact, the cross, the symbol of Christianity, they believed was the symbol of Rex Mundi, the false god of material things (Mark). This would directly associate the figure Jesus Christ with the figure of Satan and further would alienate the Cathars from standard Catholicism. It was this belief above the rest that would lead to the crusade against the Cathar Heresy.

“Cathar beliefs ultimately derived from the Persian religion of Manichaeism but directly from another earlier religious sect from Bulgaria known as the Bogomils who blended Manichaeism with Christianity” (Mark). This Manichaean religion came via the Silk Road to Europe from the Byzantine Empire, where it then blended with Christianity to create the Catharist belief (Mark). Manichæism was, as a religion, purely based in reason as opposed to Christianity’s credulity (Arendzen). Among the Manichæins and later the Cathars, there were two levels: “Those who entirely devoted themselves to this work were the ‘Elect’ or the ‘Perfect’, the Primates Manichaeorum; those who through human frailty felt unable to abstain from all earthly joys, though they accepted Manichæan tenets, were ‘the Hearers’, auditores, or catechumens” (Arendzen). The mixing of these two beliefs was fairly easy, as both Christianity and Manichæism had very similar codes of ten commandments.

Catharism was not especially widespread, and besides its centers in Albi and Toulouse was also found in Lombardy, the Rhineland and Champagne regions. And while the crusade against them took its name from Albi, the epicenter was at Toulouse (Cartwright).

Much like the later Protestants, Cathars lived very simply, as to be worldly was to fall further into Satan’s creation of the physical world. They called for no taxes or penalties, nor did they own more than the barest of necessities. Among them, men and women were seen as equals. In their equality, they also believed in dignity through labor; all members of the church worked, be they clergy or layman (Mark). This set the church against their ways on many fronts.

The Cathars also believed in both a male and female aspect of God. “God was both male and female. The female aspect of God was Sophia, “wisdom”. This belief encouraged equality of the sexes in Cathar communities” (Mark).

They did believe in reincarnation. The purpose of life, they said, was to refuse the pleasures and enticements of the world around them. Through this, they would cast off their worldliness through repeated cycles of rebirth (Mark). They continued through their reincarnations. Some Cathars practiced celibacy, but they all believed sex to be a natural aspect of life. Sex for pleasure was seen as fine and in fact was less frowned on than sex for procreation (Mark). This is, of course, exactly counter to the standardized Catholic belief.

This love for love’s sake attitude spawned the idea of courtly love in the minds of southern troubadours and writers (Mark). Courtly love was embodied in the knight and his married lady love. Take Lancelot’s original relationship with Guinivere; this was the triumph of romantic love over strategic marriage, devoid of love. The very idea of the love of a married woman was not especially cool with the church. “The damsel-in-distress was the feminine principle of God, Sophia, who had been abducted by the Catholic Church, and the brave knight was the Cathar adherent who loved, served, and was sworn to rescue her. According to this theory, Catharism spread as widely and quickly as it did through the troubadours who traveled through France performing these works” (Mark). The lady symbolized good as spirit, and as such, the knight could never reach her fully. The marriage she was trapped in, sanctified by the Church, symbolized the evil of the world (Mark 2). Of the Catharist beliefs, this had the most lasting effect, as it bore itself into the literature and poetry of the time and persisted, unlike the movement that sired it.

They were seen as major heretics by the church, as they rejected all of the New Testament except for the gospels (Mark). Of these, they fell into line most with that of John (Mark). They cast off the idea of Jesus having died for the sins of man, as they believed he had never been born, made to suffer, died, or had subsequently been resurrected. He had, according to Catharist belief, been present since the beginning (Mark). There was such a fundamental break between the main church and Catharist church that the destruction of the latter became the primary focus of the former. Catharism, though it shared a few themes with the Protestant reformation, was in fact a far more radical and dramatic form of Christianity. This religious strife gave perfect excuse for a massive land grab by the church as well (Cartwright). Though the Cathars would not have lasted long under most circumstances, it was their rejection of God as the singular creator that put them first and foremost on the headsman’s block. Their belief in the duality of creation implied, and in fact blatantly stated, that the Pope and clergy of the time were corrupt in their vast tracts of wealth, and were not on the track to salvation.

Thus the Church launched a great bloody crusade against these Cathars of southern France. First came a short and unsuccessful campaign to put down the Languedoc Cathars that lasted from 1178 to 1181 until it was halted. The murder of a papal legate in 1208 by an agent of the Lord of Toulouse, Count Raymond VI, was the catalyst that kicked off the crusade (Cartwright). “The idea of attacking fellow Christians gained ground thanks to such figures as Saint Mary of Oignies who claimed to have had a vision in which Jesus Christ expressed his concern at the heresy in southern France” (Cartwright). With Pope Innocent III’s command, and with supposed divine backing, an international force was raised to choke the life out of the heretical Cathars (Cartwright). This second movement was also backed by the French king Phillip II and later his son Louis VIII. The kings were especially interested in seizing the lands of southern France (Cartwright). In 1209, taxes were raised in order to fund an army. King Phillip supplied a royal contingent. Notable among their ranks were Simon IV de Montfort and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria (Cartwright).

“Arnald-Amaury, Abbot of Citeaux, was put in charge of recruitment and an army of barons and knights from northern France, who saw prospects of rich pickings for themselves in the lands of the conquered southern French lords, responded to the call” (Cavendish). Though the Pope had gathered a great force, he was forced to declare that only a minimum of forty days in military service would fully absolve each crusader of his sins. He also, to ensure the northern lords would stay by him, promised them the lands and riches of southern France (Mark).

In 1208, Pope Innocent III had sent the lawyer-monk Pierre de Castelnau to Southern France to enlist the aid of Raymond. Raymond promptly had him murdered (Mark). Although Raymond of Toulouse had been the Cathar figurehead and had previously vehemently denied any agreement with the Pope, he almost immediately opened up negotiations with the Pope. After a suitable penance and giving up a spot of land, he joined the Crusader army as an ally (Cartwright). Thus the first striking point for the crusading host was not Toulouse, as Raymond did penance, but rather was the land of Raymond Roger Trencavel (Cartwright).

Trencavel was not himself a Cathar, but within his lands he housed a great population of Cathars. He also did not stand and wait to be crushed, as he hoofed it out of Beziers to Carcassonne on 21 July 1209 CE, shortly before it fell under siege by Crusaders. Those defending at Beziers refused a truce with the church’s forces and were brutally sacked soon thereafter. Of the nearly ten thousand people in the city, only around seven hundred numbered as Cathars, yet every man, woman, and child was slaughtered (Cartwright). “Kill them all, God will recognise His own” was the cry that went up from Arnald-Amaury (Cavendish). The message was abundantly clear: this was no more a crusade based in the cleansing of the Catharist heretics than it was a conquest and a land grab and purging. The city of Narbonne surrendered immediately, and most nearby inhabitants fled very soon after Beziers’s fall.

The next target of the crusading army would be Carcassonne. Carcassonne was more heavily fortified and was better manned as well. However, the castle was a distance away from the river Aude, from which it took its supply of water. This supply was soon seized, despite Trencavel’s’ best efforts. On the 14 of August, the church’s forces attempted to scale the walls of Carcassonne but were driven away with heavy casualties. Arnald-Amaury offered brutal surrender terms in exchange for letting Trencavel and his family to flee with their belongings, but this was turned down (Cavendish).

As morale dropped in the water deprived castle, Amaury again offered terms for surrender. He wanted to take the city whole and thus proposed that all of its inhabitants would be spared and set free, provided they left their things to the crusading army. Trencavel agreed to negotiate. However, the safe passage offered to the parlay was breached, and Trencavel was shackled and captured (Cavendish).

The castle at Carcassonne fell on 14 August 1209 CE. Trencavel was imprisoned by the crusading army and would die several weeks later by an unknown cause (Cavendish). Simon de Montfort claimed his lands. The city of Lavaur was Simon de Montfort’s next target. When Lavaur was captured by De Montfort in 1211 CE, Aimery, the lord of Lavaur and Montréal, was hanged, his sister was thrown into a well, 80 of his knights were executed and up to 400 Cathars were burned to death (Cartwright). This burning was an important symbol. Because the Cathars were heretics, they had to be burnt. “The smallest trace of “sin” had to be extirpated, the corrupt body had to be destroyed and evil exorcised in the flames. Burning inflicted a double punishment, both temporal and spiritual, since the Cathar church considered that burial of a body was a necessary condition for resurrection” (Costagliola).

After the fall of Carcassonne, a period of the Albigensian crusade called “the war of castles” began (Costagliola). The four castles of Lastours, Cabaret, Tour Régine, Quertinheux and Surdespine, were perched on rocky cliffs and presented a challenge that De Montfort would not be able to conquer, so he turned on the city of Minerve. “Minerve was the first great siege of the crusade under Simon de Montfort's leadership, as well as the first example of his skillful use of siege warfare to take castles in geographically hostile conditions. Unlike Beziers and Carcassonne, both medium-sized towns in relatively open areas, Minerve sat atop a steep, rocky cliff surrounded by two deep river gorges” (Marvin). Along with Simon de Montfort and his troop of crusaders were men from Anjou, Brittany, Champagne, Frisia and Maine, as well as some German fighters (Marvin).

“Minerve's location made it virtually invulnerable to assault from all sides except the north, and the northern side was guarded by the citadel” (Marvin). However, being situated in a gorge, Minerve was particularly vulnerable to missile fire and was well with range. This may have also been the first use of a counterweighted trebuchet in the Crusades to that point (Marvin).

On 15 June 1210, after a siege of six weeks, it became the first place to be martyred. 150 Cathars were burned at the stake, all the while singing hymns (Castagliola). Prior, in Beziers, Cathars and citizens alike were slaughtered without questioning or offered repentance. Those at Minerve were martyrs because they held their faith till the bitter end. In 1211, De Montfort defeated the Toulouse-foix army and took large swaths of land (Cartwright). In 1213, he tried his hand at capturing Toulouse but soon turned his sights on the castle Muret instead (Castagliola). Pedro of Aragon lent a hand to Raymond IV but was more a hindrance than a benefit as he died in battle soon after. At his death and the bloodbath on the field that followed, Raymond IV and his family withdrew into Toulouse (Castagliola). However, Toulouse was overtaken bloodlessly, and Raymond VI and his young son Raymond VII took refuge at the English court in June 1215 (Castagliola). With this victory, Simon de Montfort was given the title “Count of Toulouse.” Guerrilla warfare too had broken out across southern France, and all captured towns were sacked and burned. For this, Pope Innocent III rescinded crusade status on the Cathar operation, though he would re-award it several more times over the following 15 years (Cartwright).

On July 16, 1216, Raymond VII took a force to Marseille and laid siege to the castle of Beaucaire. Recapture had begun once he had forced Simon’s brother to surrender the castle. Simon de Montfort was killed in 1218 when he was killed by a rock (Cartwright). It is disputed what kind of rock; either he was crushed by a rock thrown by a mangonel catapult or by a woman hurling said stone. Louis, soon to be Louis VIII, made a few appearances including the capture of Marmande in 1219 (Cartwright). Amaury, Simon’s son, was far less successful in his campaign than his father. Amaury was promptly defeated at Baziège and Castelnaudary and in 1224 would leave off the crusade and head for Paris (Castagliola). Both King Philippe Auguste of France and Raymond VI died in 1222. Raymond VI was succeeded by his son Raymond VII who reclaimed Carcassonne from Amaury, as well as much of his father’s land. Thus the first act of the Albigensian Crusade was finished (Castagliola).

With the death of his father, Louis VIII wanted to expand his kingdom. With the backing of Pope Honorius III, a new crusade was launched in 1223 (Castagliola). Avignon was besieged and captured in 1226. Most Languedoc lords swore oaths to the king then, as they could see what was coming, yet Raymond VII held his ground. When, in 1226, Louis died of dysentery, his son Louis IX took up his father’s crusader mantle and in fact turned out to be so zealous in his crusading that he would later be sainted (Cartwright).

The new pope, Gregory IX, was intent on wiping out the Cathar heresy, so he granted full powers to the bishoprics of Toulouse and Albi and to the Dominican preaching order. Foulques, the new bishop of Toulouse, also hated Cathars with a burning passion and so he organized a private militia called “The White Confraternity” that went after Jews and heretics. In 1229 he took part in the preparation of the treaty of Paris, known as the Treaty of Meaux. This treaty put the submission of Raymond VII onto paper (Castagliola). The Languedoc region now belonged to the king of France.

However, even with such a devastating blow, the Cathars were not ended. The Faydits were an assembly of landless knights, exiles, and above all suspected Cathar heretics who came together at Montségur, which was dubbed “the the church of Satan” by the crusaders. In May of 1242, Faydit knights, led by one Ramon d’Alfaro, murdered a handful of inquisitors. By 1243, the siege of Montségur had begun. “The castle itself stands on a limestone peak at an altitude of 1207 metres, surrounded by cliffs 80 to 150 metres high” (Castagliola). It would be an ordeal to besiege. After 11 grueling months, Hugues des Arcis, seneschal of Carcassonne, took the city. Thus commenced the burning of 200 some Cathars at Prat des Cramats, the field of the burned (Castagliola). The year 1255 saw the fall of Quéribus, on the borders of France and Aragon. The last Cathar Parfait was Bélibaste, who refused to recant and was therefore burned in 1326. Thus was marked the end of the Albigensian Crusade and the Catharist culture, at least in public.

The church was merciless. Thousands upon thousands were killed in the Albigensian Crusade, and of their number, most were women and children; non-combatants. No one of the Catharist belief was suffered to live, as they were such radicals in their heresy. Considering how much outrage Martin Luther got from his reformation, it’s no wonder the church pounced so quickly and brutally on Catharism.

With the end of the Cathar Heresy, so too was the vibrant southern French culture of the time erased. The only persisting element of the Cathars was the concept of courtly love, which had blossomed from their beliefs around the equality of all people. “Prior to the development of this genre, women appear in medieval literature as secondary characters and their husbands’ or fathers’ possessions; afterward, women feature prominently in literary works as clearly defined individuals” (Mark 2).

Protestantism would be the challenge to the church, but it would also be born of a religious reformer’s zeal and be carried onward by multiple powerful figures in royal positions including Henry VIII. It shunned material goods because shunning worldly things was at the core of the teachings in the Bible. There was no mixing of beliefs. In fact, it was the cleansing of the church from the outside influence of the world. Catharism on the other hand, was a full deviation from the church; instead of splitting from the church on grounds of purity, they became an offshoot and simply lived beside it. Their Dualist beliefs alone set them as far more radical than the Protestant movement. Also, Catharism itself was an amalgamation of Manichæism and Christianity. However, some Protestants argued that Catharism was little different in essence from Protestantism. In fact, they said, the persecution of the Cathar heresy had marked the switch of the church from pure Christianity to Catholicism (McCaffrey). “Protestant historical writing staunchly defended its new faith and used a similar argument based on lineage to link Catharism with Protestantism to create and promote the ‘rêve albigeois,’ or the insistence on the historical continuity of ‘true’ faith in the face of papal persecution” (McCaffrey).

While it’s not a perfect link between the two movements Cathar areas of Languedoc took more easily to the Protestant ideas (Walther). “Languedoc had not, like some other areas of France, undergone monastic reforms, and thus a spiritual vacuum where alien ideas penetrated easily could result” (Walther). It is in this way that Manichæism took hold in the region and why Catharism itself manifested. Catholics must have been glad that Protestants would consider the heretical neo-Manichaean dualists of the 13th century as their spiritual ancestors (Walther). Catharism was, as a movement, somewhat destined to be wrent from the earth by the church’s utter hatred of heresy and by the greed possessed by virtually every nobleman or lord of northern France.

Bibliography:

Mark Cartwright

Joshua J. Mark

Michel Costagliola

Joshua J. Mark (different article)

JSTOR

Memory and Collective Identity in Occitanie: The Cathars in History and Popular Culture

Emily McCaffrey

Daniel Walther

Arendzen, John. "Manichæism." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 6 May 2020 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09591a.htm>.

Richard Cavendish

JSTOR

War in the South: A First Look at Siege Warfare in the Albigensian Crusade, 1209–1218

Laurence W. Marvin

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

cathar.info

0 notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (August 25)

Louis IX, commonly revered as Saint Louis, was born on 25 April 1215 at Poissy, near Paris, the son of Louis the Lion and Blanche of Castile.

He was baptized in La Collégiale Notre-Dame Church.

His grandfather on his father's side was Philip II, King of France. His grandfather on his mother's side was Alfonso VIII, King of Castile.

Louis was taught in Latin, public speaking, writing, military arts, and government.

He was nine years old when his grandfather Philip II died, and his father became King Louis VIII.

Following the death of his father, Louis VIII, he was crowned in Reims at the age of 12.

His mother, Blanche of Castile, effectively ruled the kingdom as regent until he came of age and continued to serve as his trusted adviser until her death.

During his formative years, Blanche successfully confronted rebellious vassals and championed the Capetian cause in the Albigensian Crusade, which had been ongoing for the past two decades.

He led an exemplary life, bearing constantly in mind his mother's words:

"I would rather see you dead at my feet than guilty of a mortal sin."

He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians.

His biographers have written of the long hours he spent in prayer, fasting and penance without the knowlege of his people.

The French king was an avid lover of justice who took great measures to ensure that the process of arbitration was carried out properly.

All of 13th-century Christian Europe willingly looked upon him as an international judge.

He was renowned for his charity.

"The peace and blessings of the realm come to us through the poor," he would say.

Beggars were fed from his table. He ate their leavings, washed their feet, ministered to the wants of the lepers, and daily fed over one hundred poor.

He founded many hospitals and houses: the House of the Felles-Dieu for reformed prostitutes, the Quinze-Vingt for 300 blind men (1254), as well as hospitals at Pontoise, Vernon, Compiégne.

The Sainte Chappelle, an architectural gem, was constructed in his reign as a reliquary for the Crown of Thorns.

It was under his patronage that Robert of Sorbonne founded the "Collège de la Sorbonne," which became the seat of the theological faculty of Paris, the most illustrious seat of learning in the medieval period.

Louis died of the plague on 25 August 1270 near Tunis during the Second Crusade.

He was canonized by Pope Boniface VIII on 11 July 1297.

He is the patron of architecture, masons and builders.

He is also honoured as co-patron of the Third Order of St. Francis, which claims him as a member of the Order.

0 notes

Text

I've been attending a weekly pub quiz for over a year now, but last night I actually hosted it for the first time! It involves an ice-breaker round of 50/50 style questions (ie sit down if you get it wrong, stay standing if you get it right), and I am having sooo much fun making up obscure questions about all my favourite interests for next week 😂

#obscure for the regular folks at quiz anyway#these guys aren't going to know what's hit them#... 'which Catholic heresy was the Albigensian Crusade designed to eliminate? was it the Fraticelli heresy or the Cathar heresy?'#I'll have to wait until my parents sit down before I start asking questions about figure skating...#maybe I should bust out some Latin or Putonghua#... 'what is the literal translation of the Chinese cheer phrase 加油? is it “add oil!” or “fight!”?'#Beatles questions are ubiquitous in pub quizzes but I think this one will still be difficult:#'which song was the b-side to the Beatles' 1963 single Please Please Me? was it P.S. I Love You or Ask Me Why?'#does anyone have some of their own obscure/nerdy questions I could use?#nerdery#and my ultimate weakness: figure skating nerdery

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

in love with the way everything was so scary for them

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sack of Jerusalem, 1st Crusade. For the literal lowest hanging fruit.

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

i agree with the right wingers who say the united states is a christian country

it's just that they're fucking heretics

#they like crusades right?#i could go for a nice albigensian crusade#(that's a joke; the cathars seem pretty cool)#(unlike these assholes)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The dagger talisman specifically calls them "white-garbed field surgeons", so they were field surgeons, but it's sort of implied that due to the scale of the Shattering there was no medicine to be performed. Historically, the misericorde was a companion weapon of knights in the High Middle Ages, often for backstabs or euthanasia. It was also really popular with criminals and assassins, due to its small size.

Medics could perform euthanasia, but so could other knights. It doesn't really make sense to me that there would be a completely separate faction just for mercy killing, even in Elden Ring.

"A sense of mercy is a catalyst for bloodlust." means that Varré began his career as a surgeon out of a desire to do good, but the bloodshed has led him to sadism and disregard for human life.

It seems plausible putting so many soldiers out of their misery, coupled with the miserable work conditions (Varré wears a filthy tarp + rats, crows, dogs, flies) would lead him to think poorly of the Greater Will ("no love for our kind"), which would make him sympathise with Omens. He's also particularly cruel to the player and other Tarnished specifically because Tarnished are by definition pawns of the Two Fingers, previously abandoned by them ("Your loyalties are misplaced with them.").

Varré can take you to the Roundtable Hold and has very good insight into how Grace looks.

He asks you to see the Two Fingers "in the inner chamber", "So that you may see for yourself". Varré knows the exact location of the Fingers and "for yourself" implies he has been granted audience before, meaning he once served Godfrey.

Perhaps he even believed death was acceptable as long as the Erdtree recycled the corpses, but the instability and unjustified cruelty of the Greater Will slowly dented his faith.

Real life example, during the Albigensian Crusade: "Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius" meaning "Kill them all; let God sort them out."

Part 2: Misericorde

89 notes

·

View notes