#alberta native plants

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

First 15 of my series of linocuts of native plants in Alberta are now available for order in my shop! Letter Mail Option // Rigid Mailer Option

Each print is drawn, carved, and printed by myself on handmade paper, also made by me!

You can find some quick facts about each plant in my highlighted stories on insta if you wish! From top left in the first image we have: Pineapple weed, Jacob's ladder, Pussytoes, Goldenrod, Yarrow, Purple Coneflower, Mountain Hollyhock, Gumweed, Red Paintbrush, Prickly Rose, Rocky Mountain Bee Plant, Blue Beardtongue, aaaand Columbines! Let me know which ones your favourite so far- and which native plant I should carve next! (prairie smoke and strawberry spinach are already in the works!)

#botanical art#floral art#floral prints#alberta native plants#black and white#flowers#plants#cottagecore#forager art#foraging#medicinal herbs#witchy art#garden witch#kitchen witch#edible plants#natural dye#pineapple weed#wild chamomile#jacobs ladder#pussytoes#golden rod#yarrow#coneflower#echinacea#hollyhock#mallow#gumweed#paintbrush#rose#prickly rose

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erodium cicutarium (common stork's-bill)

Common stork's bill is another European wildflower branded a 'weed' outside it's native environment. This Mediterranean plant prefers warm, dry soils and is now found throughout Eurasia, North America, South America, central and southern Africa, New Zealand, Australia, and Tasmania. Common stork's bill has a deep taproot and is lush and green compared to the sundried grass that surrounds it.

As the French say, "La fleur, elle est très petite." (roughly translated: "The flower, she is very small.") Typically about a third of an inch wide (8.5 mm), these tiny pink flowers sure stir up a lot of resentment from people who prefer native wildflowers. The Alberta Native Plant Council even has a nice photo of Erodium cicutarium in it's 'Rouges' Gallery'.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#stork's bill#A beautiful thing in an unlikely place.#Just another roadside attraction.#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Vancouver

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

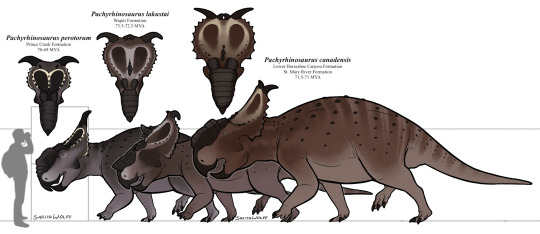

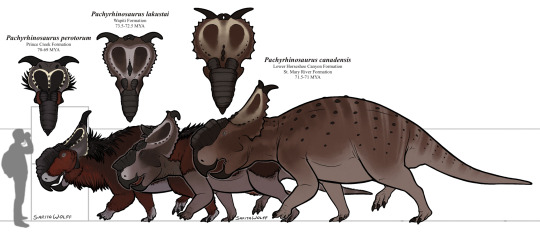

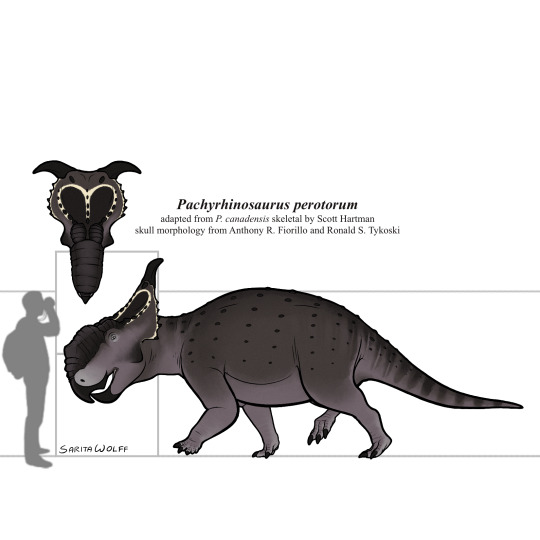

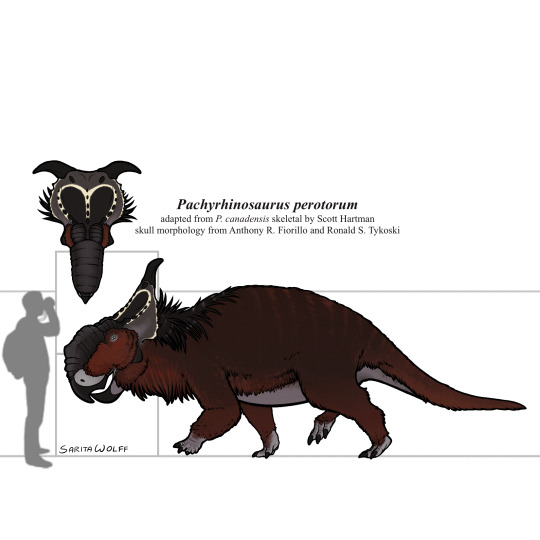

A Patreon request for rome.and.stuff (Instagram) - Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum… that I went a bit overboard with lol. I’ve been waiting for an excuse to draw my favorite ceratopsian, and to digitally adapt my old Pachy marker drawing design.

So! Pachyrhinosaurus! As seen above, there were three known species of Pachyrhinosaurus, living in different locations and eras in Late Cretaceous North America.

The oldest, P. lakustai, was native to the Wapiti Formation of Alberta and British Columbia, Canada. It’s known for the extra spikes it has at the center of its frill.

The slightly younger P. canadensis was native to the lower Horseshoe Canyon Formation and the St. Mary River Formation of Alberta and northwestern Montana. It was the largest of the three.

The youngest, P. perotorum, was native to the Prince Creek Formation of Alaska. As this ceratopsid seemingly stayed put during the long, dark, cold Alaskan Winters, it likely had adaptations for keeping warm.

The depiction of a “woolly” Pachyrhinosaurus was first popularized by Mark Witton as a speculative work, but the trope has prevailed. While many paleontologists find a heavy feather covering on a centrosaurine to be highly unlikely, and maintain that the animal’s size and homeothermy would have kept it warm enough, we still have no skin impressions to suggest that P. perotorum was fully scaly. So a feather coating is not completely out of the question (though it is unlikely). Still, I love the look of a woolly Pachyrhinosaurus and how it challenges our previous conceptions of non-avian dinosaurs. Stranger things exist in nature. I had to include a “woolly” option, especially since I already use the guy as my avatar on my paleo Instagram account, SaritaPaleo.

Pachyrhinosaurus was particularly unique in that it seemingly traded off something that had previously worked for other ceratopsians, horns, for a large nasal boss instead. For Pachyrhinosaurus, a battering ram worked better than a sword.

It was herbivorous, using its strong cheek teeth to chew tough, fibrous plants. Perhaps during the dark and cold Winters, P. perotorum would have also dug for roots or even scavenged carcasses. At any rate, from observations of their unusually conspicuous growth banding, it appears growth for P. perotorum would have been stunted during the harsh Winter, but was extremely rapid in the warmer months, an adaptation for the Alaskan climate.

The tundra of the Prince Creek Formation housed a surprising amount of diversity. Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum would have lived alongside smaller ceratopsians like Leptoceratopsids, as well as other ornithischians like the pachycephalosaurine Alaskacephale and the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus. Theropods such as Dromaeosaurus and Saurornitholestes, as well as a yet unidentified giant Troodontid, lived here as well. P. perotorum’s main predator would have been the tyrannosaur Nanuqsaurus. Small mammals were also somewhat common here, such as Cimolodon, Gypsonictops, Sikuomys, Unnuakomys, and an indeterminate marsupial.

(Btw, the request tier for Patreon starts at only $5 a month. 😉 Link is pinned at the top of my blog.)

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Pachyrhinosaurus#Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum#Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai#Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis#Centrosaurines#ceratopsians#ceratopsids#ornithischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Prince Creek Formation#Wapiti Formation#Horseshoe Canyon Formation#St. Mary River Formation#Late Cretaceous#Canada#United States of America

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good story from Yale Environment 360, without a paywall (I think), about beavers, public land, wildfires, endangered species, the largest beaver dam in the world, the degradation of that land and the large pond behind the dam due to the tar sands mining activity in the vicinity. In other words, a microcosm of all the bad stuff and good stuff intersecting in one place in Canada. Excerpt from this story:

Wood Buffalo National Park, the largest national park in Canada, covers an area the size of Switzerland and stretches from Northern Alberta into the Northwest Territories. Only one road enters it from Alberta, and one from the NWT. If not for people observing it from airplanes and helicopters, and satellites photographing it, little would be known about big parts of it. The park is a variety of landscapes — boreal swamps, fens, bogs, black spruce forests, salt flats, gypsum karst, permafrost islands, and prairies that extend the continent’s central plains to their northern limit. The wood buffalo in the park’s name are bison related to the Great Plains bison. In this remoteness, the buffalo descend from the original population, and the wolves that prey on them are also the wild originals. Millions of birds summer and breed here. The park holds one of the last remaining breeding grounds of the whooping crane.

Other superlatives and near-superlatives: the delta in the park’s southeast where the Peace River and the Athabasca River come together is one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world; last summer, some of Canada’s largest forest fires burned in the park and around it; and — just inside the park’s southern border — is the largest beaver dam in the world.

The dam is about a half-mile long and in the shape of an arc made of connected arcs, like a recurve bow. The media has known about it for 16 years, and in that time no bigger beaver dam has come to light, so it’s still known as the biggest, and scientists believe it almost certainly is. Animal technology created it, but human technology revealed it.

Many of the beavers that have reestablished themselves globally are descended from beavers that were planted by wildlife biologists. The thriving beaver population of Tierra del Fuego (another place Thie has studied) is descended from beavers brought to Argentina from Canada’s Saskatchewan River, who are themselves scions of beavers transplanted from upstate New York. No reintroduction of beavers was done in Wood Buffalo Park. Thie believes that the beavers who built the dam are of original stock. Like the wood buffalo and the wolves, they were too remote to be wiped out.

The park is suffering the worst drought in its history. Flows are down by half in many places, owing to climate change, water diversion, poor seasonal snowpack, and dams on the Peace River, upstream in British Columbia. A danger that seems inescapable comes from the oil sands that are being mined for crude-oil-containing bitumen, and from tailing ponds that hold trillions of liters of mine-contaminated water. The ponds are near the banks of the Athabasca River, just upstream from the park boundary. They are fatal to birds that land on them. Given the direction that water flows, conservationists and native people fear the tailings will pollute the park eventually. Toxic chemicals have already been found in McClelland Lake, just southeast of the park. Locals stopped taking their drinking water from the lake years ago.

Gillian Chow-Fraser, the boreal program manager for the Northern Alberta chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, in Edmonton, travels in the park often by helicopter, canoe, and foot. She has described the park’s environment as “super degraded.” When I spoke with her by phone not long ago, she talked about a recent tailing basin leak that was not reported to the First Nations downstream of it for nine months. In places that used to flood regularly but now don’t, the land is drying out and vegetation disappearing. Though she crisscrosses the park, she has never seen the world’s largest beaver dam, but she’s grateful that it’s there and bringing the park attention.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists use a refrain to sum up in the impact of earthworms [...]: “Good in your garden, bad in the forest.” It’s a quip that can sometimes come as a surprise to people used to thinking of earthworms as symptoms of healthy soil.

In Canada’s northern forests, there’s increasing evidence of a worm problem.

According to research from 2013, tiny soil invertebrates, like mites and springtails, decrease in abundance by more than 50 percent when earthworms are present. These minute creatures play an important role in the decomposition and nutrient-cycling of plants, and their decline can likely be attributed to the rapid way earthworms devour leaf litter. [...] And earthworms, it seems, are spreading everywhere. Research on their presence in northern US forests, where invasions are more advanced, suggests that they could have cascading effects including everything from more severe drought to greater human allergies. [...]

[N]early all native species of earthworms in Canada were wiped out over 12,000 years ago, during the last period of glaciation. Earthworms, we now know, have been present in southern Canada for only a few short centuries, the first having hitched a ride with colonizing Europeans [...].

---

Lumbricus terrestris -- the common earthworms people find in their gardens, which are often called dew worms or Canadian nightcrawlers in fishing circles -- are one of the worm species that were transported from Europe and have settled into their new home so successfully that they’ve emerged as a valuable commodity. According to Steckley’s later research on the subject, demand for these worms as fishing bait exploded as recreational fishing became popular in the wake of the Second World War. But earthworms defy attempts at commercial cultivation and have to be plucked from the wild.

In the 1980s, southwestern Ontario, with its rich soil, abundant volume of introduced nightcrawlers, and steady supply of immigrant labour, quickly eclipsed the other worm-producing regions of North America. By the time Steckley drove past the worm pickers,

Ontario had become the epicentre of global nightcrawler production, with an estimated 500 million to 700 million worms picked and shipped across North America every year.

---

Steckley, who is now a doctoral candidate at the University of Toronto researching Ontario’s bait-worm industry, says that he was actually right about his initial impression: there were bags of money in that farmer’s field, at least in the figurative sense. Worm pickers usually make around $30 per 1,000 worms, and a picker in the right conditions can scoop up to 20,000 worms a night.

“Farmers who rent their land [for an entire year] can make more from worm pickers than any other crop that they feasibly plant,” says Steckley, who’s heard of rents of up to $1,500 an acre. The industry is worth around $230 million today, Steckley estimates.

Despite the spread, Steckley says there have been few efforts to regulate its downstream environmental effects -- in fact, most people he’s encountered have been unaware that earthworms are invasive. [...]

---

But, in the boreal forest, most of the carbon is stored in organic matter -- that thick layer of fallen leaves, roots, moss, and rotting wood that, under normal conditions, decomposes slowly. But deep-burrowing earthworms feed on this material [...]. Justine Lejoly, who is conducting doctoral work with the University of Alberta and the Canadian Forest Service, found that, in some invaded parts of the Canadian boreal, 96 percent of this layer has disappeared. “Most of the forest floor is gone, so that means a lot of carbon is gone,” she says. This finding, which Lejoly made alongside her supervisor Sylvie Quideau is striking because 28 percent of the boreal forest is found in Canada and as much as one-third of terrestrial carbon is stored in the boreal worldwide. [...]

---

Text by: Moira Donovan. “Revenge of the Earthworms.” The Walrus. With illustration by Joey Ng. 13 June 2022. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks added by me.]

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native American History Month: Fiction Recommendations

And Then She Fell by Alicia Elliott

On the surface, Alice is exactly where she thinks she should be: She’s just given birth to a beautiful baby girl, Dawn; her charming husband, Steve - a white academic whose area of study is conveniently her own Mohawk culture - is nothing but supportive; and they’ve moved into a new home in a posh Toronto neighborhood. But Alice could not feel like more of an impostor. She isn’t connecting with her daughter, a struggle made even more difficult by the recent loss of her own mother, and every waking moment is spent hiding her despair from Steve and their ever-watchful neighbors, among whom she’s the sole Indigenous resident. Even when she does have a minute to herself, her perpetual self-doubt hinders the one vestige of her old life she has left: her goal of writing a modern retelling of the Haudenosaunee creation story.

Then, as if all that wasn’t enough, strange things start to happen. She finds herself losing bits of time and hearing voices she can’t explain, all while her neighbors’ passive-aggressive behavior begins to morph into something far more threatening. Though Steve assures her this is all in her head, Alice cannot fight the feeling that something is very, very wrong, and that in her creation story lies the key to her and Dawn’s survival.... She just has to finish it before it’s too late.

Bad Cree by Jessica Johns

When Mackenzie wakes up with a severed crow's head in her hands, she panics. Only moments earlier she had been fending off masses of birds in a snow-covered forest. In bed, when she blinks, the head disappears.

Night after night, Mackenzie’s dreams return her to a memory from before her sister Sabrina’s untimely death: a weekend at the family’s lakefront campsite, long obscured by a fog of guilt. But when the waking world starts closing in, too - a murder of crows stalks her every move around the city, she wakes up from a dream of drowning throwing up water, and gets threatening text messages from someone claiming to be Sabrina - Mackenzie knows this is more than she can handle alone.

Traveling north to her rural hometown in Alberta, she finds her family still steeped in the same grief that she ran away to Vancouver to escape. They welcome her back, but their shaky reunion only seems to intensify her dreams - and make them more dangerous. What really happened that night at the lake, and what did it have to do with Sabrina’s death? Only a bad Cree would put their family at risk, but what if whatever has been calling Mackenzie home was already inside?

Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline

Joan has been searching for her missing husband, Victor, for nearly a year - ever since that terrible night they'd had their first serious argument hours before he mysteriously vanished. Her Métis family has lived in their tightly knit rural community for generations, but no one keeps the old ways... until they have to. That moment has arrived for Joan.

One morning, grieving and severely hungover, Joan hears a shocking sound coming from inside a revival tent in a gritty Walmart parking lot. It is the unmistakable voice of Victor. Drawn inside, she sees him. He has the same face, the same eyes, the same hands, though his hair is much shorter and he's wearing a suit. But he doesn't seem to recognize Joan at all. He insists his name is Eugene Wolff, and that he is a reverend whose mission is to spread the word of Jesus and grow His flock. Yet Joan suspects there is something dark and terrifying within this charismatic preacher who professes to be a man of God... something old and very dangerous.

The Seed Keeper by Diane Wilson

Rosalie Iron Wing has grown up in the woods with her father, Ray, a former science teacher who tells her stories of plants, of the stars, of the origins of the Dakhóta people. Until, one morning, Ray doesn't return from checking his traps. Told she has no family, Rosalie is sent to live with a foster family in nearby Mankato - where the reserved, bookish teenager meets rebellious Gaby Makespeace, in a friendship that transcends the damaged legacies they've inherited.

On a winter's day many years later, Rosalie returns to her childhood home. A widow and mother, she has spent the previous two decades on her white husband's farm, finding solace in her garden even as the farm is threatened first by drought and then by a predatory chemical company. Now, grieving, Rosalie begins to confront the past, on a search for family, identity, and a community where she can finally belong. In the process, she learns what it means to be descended from women with souls of iron - women who have protected their families, their traditions, and a precious cache of seeds through generations of hardship and loss, through war and the insidious trauma of boarding schools.

#indigenous heritage#fiction books#fiction#reading recommendations#reading recs#book recommendations#book recs#library books#tbr#tbr pile#to read#booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog#readers advisory

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The prairies

the prairies have a huge image problem through no fault of their own. When talking about conservation it’s easy to sell people on preserving areas with mountains, the boreal forest, ocean, rainforests etc. But the prairies have been a tough sell. It’s not because the prairies aren’t beautiful and captivating and important. It’s because so many people don’t even know what an actual prairie is. There’s a good chance when you read prairie you pictures fields of wheat/barley/oats/canola/whatever crops are common to your area. But that’s not a prairie. A prairie is a thriving eco system with a shit ton of bio diversity. It may not look it but it has some of the most bio diversity of any land eco system. It is also one of the best eco systems for sequestering carbon. The absence of much bush should not make an eco system disposable.

This is one of my biggest issues with people advocating for less livestock production in favour of crops. Crops don’t sequester nearly as much as a native grass prairie. But a native grass prairie not only can support livestock but needs grazing animals to thrive. I know we’ve all heard about cows and emissions but what people don’t consider is the amount of emissions being sequestered by allowing these animals to graze an in tact prairie, while also allowing a bio diverse eco system to flourish. Yes there is bad cattlemen out there, just like there’s good ones who care a lot about conservation (despite your notions thay all ranchers/cowboys don’t give a shit about the land). I could continue on about this about how 99% of ranchers care a lot about the welfare of their livestock but that’s a different conversation.

my point is the preservation of prairies are not only an absolutely vital part of protecting bio diversity and in turn helping fight climate change but tue revitalization of these prairies needs to happen too. Currently only 6% of native prairie in North America is in tact (there is tame pasture and prairie which is better than crops but not as good as native plants). Some places are better than others (but nobody is great) like Alberta (26% left), Saskatchewan(21%). But some are absolutely terrible like Iowa and Texas.

prairies are not a barren wasteland waiting for humans to plant crops. They are an amazing and complex eco system just as deserving as the mountains and forests of our protection

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fig 1: A boxelder

How to Guerilla Trees (in CALGARY)

In my region of Southern Alberta, there are a few trees worth planting in order to enhance the urban forest. Granted, these trees are partially or completely removed from their ecological context half the time, but they still provide some services- shade, carbon storage, habitat for birds or certain insects. The list goes on.

The species I'd recommend here are Acer negundo, Fraxinus pennsylvannica, Populus balsamifera, Populus deltoides occidentalis, and Salix sp. for their ease of cultivation... In some cases I think Prunus sp. can be a decent choice... I'll use common names from here on... boxelder/Manitoba maple, ash, cottonwood / poplar, willow. Maybe cherry, maybe "moutain ash" or Rowan (sorbus sp).

What is a microhabitat?

This tree here is a boxelder on the third summer of it's little life. It is in a small depression in the soil that collects slightly more water than the surrounding. It is protected by stones, a ribbon, and stakes. This tree is watered every week or two in the heat of summer, if it hasn't rained. I believe it has a good future ahead of it.

You might notice that small trees sprout quite often along the shade of fences, or between a fence and a shed, etc. These places are sheltered from trampling and mowing, and the soil stays more moist and cool in the heat of the summer.

You may also notice that ash and Russian elms particularily can grow in cracks on the sidewalk. Growing out of the concrete isn't as bad as it appears, because there is much less competition for the soil beneath a concrete slab, especially for a plant that can grow a large root system like a tree does. Even if the soil doesn't get rained on directly, water percolates through the soil from the surroundings.

Also, the direction of a slope can significantly affect the amount of direct sunlight the soil recieves, or the amount of water that collects there. The bottom of ravines, and north slopes are the most moist. The top of a ridge or a south facing slope is the driest.

Boxelder and Ash

Boxelder and to a lesser extend ash are very hardy trees that can hold their own in this climate without having to be watered once established. These trees grow reasonably fast and are native at least to the great plains of North America. They are well adapted to growing in sites disturbed by human activities, and can also be found as far south as Texas or Arizona along sheltered streams- so their ability to survive the changing climate seems pretty certain. I also have a hunch that before the last glaciation, the range of these species probably extended further north than it does now, along with perhaps oaks and elms. Boxelder is considered a low value tree, and maybe I'll change my mind someday, but for now, it is useful because it is so easy to grow. These trees are partially tolerant of shade when they are young - and ash seedlings in particular can be found growing underneath spruce trees.

It is easy to source seedlings of boxelder, ash, and cherry. If they are in a spot that isn't exactly a good long term site for a tree, and you can either pot them or plant them somewhere else right away. Sometimes vacant lots can have dozens of tree seedlings. You have to be careful digging up even a small tree as the taproot can be a lot longer than you would expect even for a seedling that is barely 10 cm tall. I think it is better to pot them and keep them for at least a season so that they get large enough to be conspicuous.

There are multiple reasons to prefer growing a tree to conspicuous size-

1- You can find them again. You ought to mark a tree with a stake anyway, though.

2- Once a tree is 2 feet tall, it might be safe from public mowing because it has crossed the threshold of looking like nothing or a little weed to looking like a little tree.

3- you can be sure that it didn't die from being dug up.

4- A tree that is around 2 feet tall can graduate from significant competition with weeds

I choose a microhabitat where there is a depression in the land, or at the base of a slope, or especially on a north or east facing slope. These places will dry out the least.

It is also easy to collect and sprout boxelder and ash from seed en mass - you can collect kilograms of seed in the fall and winter. The seeds probably have less than a 1 in 1000 chance of surviving their first year on barren soil, but they provide mulch for their own germination. Barren soil is good enough to get them started anywhere that isn't likely to be mowed. Ravines and north or east slopes are better, as they can have a hard time getting enough water. They probably will need some water in hot stretches from July through September to survive the first 2 summers, unless they are in a particularly good site.

It helps to mark them with stakes, to mulch them. The mulch legitimizes the planting as "intentional and human," along with helping reduce competition from weeds and maintaining soil moisture. In places with mowing risk, mark them with a ring of large stones. They aren't as prized as the poplars for their bark but they can be fodder for rodents and could benefit from some protection.

Cherry and Rowan

There are native species in both the genus Prunus and Sorbus, but neither of these native species are popular or even common within urban habitats compared to the horticultural cultivars- the native cherry is scrubby, but common in grassland habitats - it can be difficult to identify with certainty, but P. virginiana (the native variety) has shorter racemes with sparser, slightly larger flowers and fruits , and has a less tree-like shape. The native rowan are very small trees or scawny shrubs and a very minor component of cooler forests habitats.

Both of these genera are popular flowering trees and decently hardy, and they provide a lot of food for birds.

Willow and Poplar-Staking

These trees can be grown from seed, but they typically reproce vegetatively- and are easy to produce with "cuttings." You can take a branch that is about thumb-diameter, cut it into about 30-60 cm stakes, and stick them into wet soil. You'll get pretty decent survival rate as long as they stay moist and are not girdled by rodents. You can keep them in a pot for the first year, or stick them into mud near permanent sources of water. . .

This willow was not watered at all- I put a dozen stakes into the mud on a seep along a south-facing slope.

Poplar

There are four species in the bow-river valley and 3 of them are in the "cottonwood" subgenera (if that's valid) that appear to have a more recent ancestor with each other than with the aspens (which is the 4th species). The cottonwoods are easier to grow because they can be started from stakes like willow. Trees in this genus tree NEED full sun, and will create a quite open canopy forest with a very rich understory.

Poplar is the best tree in the bow river valley, as they are a keystone species that supports pretty much the entire ecosystem. Forests of cottonwoods create an extremely diverse patchwork of sub-habitats for a variety of shrubs and wildflowers, and they are food for a huge number of insects. They also have the handy habit of growing extremely quickly and volunteering in turfgrass. The easiest tree to grow is a volunteer poplar- I put a stake on either side of the sucker when it is around 1m tall, surround the base with a 1m ring of softball sized stones, and weed everything within that ring, and place mulch within that ring. The tree should be safe from mowing, but nothing is guaranteed. They can easily become taller than a person by their second complete growing season, and from then on, you don't have to care for them, really.

The deep rooting system and the support of their parent tree (which they are connected to underground) means a volunteer poplar doesn't have to be watered.

The bark can be food for rodents and the leaves are a favorite of aphids, so they might benefit from some protection- a cage of chicken wire, or a wrap around the trunk to protect the bark. I don't do anything about aphids personally, as they are the "base of the food chain," but if I was to do something to control them, maybe wiping them off of the leaves would help reduce the damage.

Aspen

Although aspen is ecologically important, it takes extra effort to grow. You can try to protect a sucker in the same way, but they do not grow quite as quickly (less than 1m per year). Aspen cannot grow roots from a branch cutting easily (but allegedly can be done), allegedly they can be grown from a root cutting, or suckers can be dug up. The seeds can be started from the cottony fluff in late spring if the soil is kept perpetually moist and not too HOT. The seedlings are a little bit fragile and a favorite food of rabbits and rodents, so they have to be protected until they are probably about a meter high, and even then the bark is vulnerable to gnawing until they are probably thicker than a thumb.

As of this writing, my only aspen have been eaten by rodents. Some of them roasted in the late summer sun. These trees need some care when they are young.

Conifers

I've tried digging up and transplanting tiny saplings of spruce, sowing spruce, and marking and protecting small spruce saplings. They grow quite slowly and can have a hard time getting established without shade. These trees are later successional and really benefit from a forested environment- at least in the Calgary metropolitan area, they don't do extremely well without care - besides, the most common spruce in city limits is the non-native Colorado blue spruce. The Alberta white spruce (p. glauca) definitely needs to keep it's feet in the shade- north facing slopes and ravines only- but it does well growing behind fences, in the shade of other trees, between houses, etc.

Pines are not native to the Calgary area, or at least are very rare in natural environments. The lodgepole pine benefits from a slightly cooler climate. The Ponderosa pine is the second closest to being a native species and it may be a decent choice here in the future, but they seem to come from places with much milder winters.

Birch

Birch is sensitive to heat and drought. The seeds can be collected en mass and sown on moist barren soil. I haven't grown birch. I think the paper birch is at its limit for heat tolerance as the climate changes beyond the 21st century in Calgary', and it probably will not compete well with boxelder or ash or the elms in the future. I'm sure it could be grown if it has shaded soil- the north side of a house, behind a fence, etc. The scrubby Betula occidentalis is a common large shrub in the communities of plants along natural water bodies. Collecting and sowing seeds seems easy enough if there is disturbed soil along the margins of a creek. They need constant supply of moisture. I have not cared for a sapling of birch.

Elm

Elms are not native to Alberta, but they are found to the East and the South. They are river valley trees. The American elm is a lovely tree but it doesn't reproduce easily naturally in Calgary, probably because it isn't a great climate for the sensitive seedlings. The russian elm is hardier and can be found naturalized in Montana. It probably will become more common in the future. I do not plant elms. I do not plant oaks either. There is a species of oak native to places East of here. It is possible that in the distant past, Alberta was home to elms and oaks.

Happy sprouting. Wear an orange vest so people know you are doing important work, and I don't recommend digging with a full sized shovel within the city because of underground wires, and because it's super illegal.

0 notes

Text

Unforgettable Sojourn at Royal Canadian Lodge with Culinary Delights at Evergreen Restaurant

Located in the center of Banff National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site, the Royal Canadian Lodge is a perfect mix of luxury and nature, rendering visitors a memorable experience. Either you are exploring the perfect splendour of the Canadian Rockies, adventuring into on outdoor sight-seeing or just relaxing, this classy lodge renders the ideal halt for every tourist. However, a paradise for foodies the restaurant assures not just a dining, but also a gastronomic trip that you will linger in mind for a long time.

In this blog post, looks at closely what makes a halt at this lodge so extraordinary, and how the culinary delight at Evergreen Restaurant banff enhances the experience to the higher level.

A Lavish Retreat in Banff At The Royal Canadian Lodge

This lodge is an epitome of countryside fascination and contemporary amenity. Positioned along Banff Avenue, the main road that passes through the town of Banff, the lodge is just at short distance from the town center and many natural charms. The lodge provides a perfect base for sightseeing Banff National Park, rendering convenient approach to legendary milestones like- Lake Louise, Moraine Lake the Banff Gondola etc.

Accommodation that Blends Luxury with Classiness

Visitors at the lodge can select from a range of rooms and suites, all planned with cosiness and unwinding in mind. Each room is stylishly equipped with modern amenities, like- luxury beds, firesides and large windows that makes you to immerse in the splendid sights of the nearby peaks. The warm, earthy hues decoration emanates a cozy, hilly lodge atmosphere, making it the perfect retreat after a day of exploring the great outdoors.

Furthermore, to the lavish rooms, the lodge provides a variety of facilities including an indoor mineral pool, a fully furnished wellness center and a spa that specializes in revitalising cures intended to unwind body and mind both.

But the highlight of your stay at this lodge may very well be the feasting experience at its signature restaurant- Evergreen Restaurant.

Gastronomic Delight at Evergreen Restaurant: A Feast for the Taste Buds

One of the foremost reasons guests speak out about the lodge is the food delight at Evergreen Restaurant. Famous for its novel approach to Canadian delicacy, the restaurant provides a menu that reflects the abundance of the native scenery, highlighting fresh, indigenously obtained materials.

A Celebration of Canadian Cuisines

Evergreen Restaurant is a festivity of the ironic and varied tastes which Canada has to render. The restaurant takes pride in providing delicacies which are not only exquisite to watch, but also choke block with taste. The chefs at Evergreen have prepared a menu that perfectly fuses conventional Canadian flavour with current techniques, creating a feasting experience that feels both familiar and thrilling.

Commence your food journey with a starter like- the Alberta Bison Tartare, a sign to the indigenous wildlife and culture. Skilfully seasoned with aromatic plant and spices, the Bison Trtare is a robust, yet sophisticated delicacy to what Evergreen has to provide. One more dish is the- Seared Quebec Foie Gras served with a seasonal fruit sweet course and artistic toast. The moderate balance of rich, spicy Foie Gras with the sweet and sour dessert of fruit cooked in syrup renders this delicacy a generous delight.

A Display of the Best Indigenous Materials The Main Course

For the main course, restaurant truly excels. The Grilled Alberta AAA Beef Tenderloin is a prominent dish, prepared to precision and served with roasted root vegetables and a decadent red wine sauce. The tenderloin, obtained from the finest farms in Alberta, illustrates the high-quality ingredients the restaurant is famous for.

For seafood fans, the Pan-Seared Atlantic Salmon is another must-try cuisine. Combined with a Lemon Beurre Blanc Sauce and fresh seasonal vegetables, the delicacy matches the seamless equilibrium between lightness and richness. The precision in preparation makes sure that each morsel is brimming with taste, while the stylish serving makes it a feast as a treat to watch.

Those looking for a vegetarian choice too won’t be disheartened either. The Wild Mushroom Risotto is a filling and nutritious dish, prepared with earthy mushrooms, creamy Arborio rice and a subtle flavour of truffle oil for that render additional touch of luxury. The risotto is a testimony to Evergreen Restaurant's promise of offering a different variety of choices for all dietary preferences, without conceding on flavour or quality.

Desserts and Fine Wines to Conclude the Experience

Dining experience at this restaurant would be incomplete without trying in one of their rich, lavish and delicious desserts. The Maple Crème Brûlée is a favourite delicacy of the guests, rendering a uniquely Canadian twist on the typical French sweet course. The browned sugar layer bangs open to expose a silky-smooth custard filled with the sweet and discrete taste of Canadian maple syrup.

The Baked Alaska, another flamboyant dessert, is perfect for those looking to conclude their meal with a touch of amusement. Flambéed Tableside, this dessert pools layers of cake and ice cream encased in a golden meringue, makes both- a delectable and amusing conclusion to your meal.

Couple your meal with a variety from Evergreen’s wide wine list, which features both Canadian and international brands. The restaurant's experienced staff is always there to serve the right wine to pair your meal, making sure that every aspect of your dining delight is perfectly served.

Evergreen Restaurant: More than Just a Meal

Here dining is about more than just eating- it’s about relishing every moment. Either you’re rejoicing a special occasion or simply looking for a unique meal during your stay at the Royal Canadian Lodge, the gastronomic delight at restaurant is certain to leave a long-lasting imprint. The precision, quality of constituents and assurance to offer the best of Canadian food make it a sought-after for any food lover.

Conclusion: A Stay Worth Remembering A stay at the lodge is more than just an escape-it’s an involvement into the natural splendour and food fullness of Banff. Whether you’re enjoying in the striking mountain sights, relishing the lodge's deluxe facilities, or involving in the food delight at Evergreen Restaurant, every moment at this lodge is intended to leave you with unforgettable memories. For those looking for the perfect balance of exploration, unwinding and top-notch dining, this lodge in Banff is the destination you’ve been fantasizing of.

#Royal Canadian Lodge#evergreen restaurant banff#evergreen restaurant#banff#canada#hotel#restaurant#dining#fine dining

0 notes

Text

I’m sorry that my adding that personal identifier to your feel good post because I personally am from the Canadian (not American) prairies has hurt your feelings. My comment wasn’t trying to take anything away from your thoughts on Kansas. The sentiment and spirit of the post made me nostalgic and I wanted to share your love and appreciation for the variety of prairie experiences. Perhaps I should have added “too” or something to my comment to be more clear, but it was the middle of the night, I was tired, and it never occurred to me that my words were offensive.

Waking up to this message was surprising, I’ll admit. I have a few thoughts in response, in no particular order:

- Are you bothered because I added to the body of the post not just putting it in the hashtags? Because I’m genuinely confused about why it’s upset you so much.

- Technically the “actual proper all-encompassing term for the continent” is North America, but the continent contains three distinctly different countries. (And there is also Central and South America to consider.) Colloquially the world has settled on using the terms “America” and “American” to apply specifically to the middle country of The United States of America and the people there, so using “American” does imply that you were referring just to the USA.

- Canadian and American prairies are not the same. Both physically and culturally. This continent is huge — so even one end of one Canadian prairie province can be noticeably different than the other end. Kansas and Alberta are approximately 2,300 km and more than 10 degrees latitude away from each other. (And I think a different time zone too.) They may look similar at a glance but they have different climates, weather, growing seasons, native plants, etc. (e.g. it is ~5-8C in AB as I write this, and 20C in Topeka). Implying that Alberta/Saskatchewan/Manitoba are the same prairies as Kansas/Oklahoma/Texas (and everything in between) is an inaccurate generalization.

I apologize again that I was unintentionally stepping on your toes (I was attempting brevity instead of over-explaining but that clearly backfired) with my reblog. I will do my best to be more careful with my words on here in the future. I’ll be honest though, your response felt a little out of proportion and kinda condescending — which I hope was not your intent.

If you’d like to compare notes (celebrate/commiserate) about prairie life, and all the differences and similarities between our two grasslands, I’d love that. (People where I live now just don’t understand what it’s like to have so much sky above you all the time.)

If not, I understand and hope your day gets better.

hey are you the american prairies the way that people who don't know you make uncharitable generalizations and assume there's nothing of interest but people who do know you think you're beautiful and unique and defend you fiercely and consider you a vital part of the world

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pinus Contorta

Pinus contorta, with the common names lodgepole pine and shore pine, and also known as twisted pine,[2] and contorta pine,[2] is a common tree in western North America. It is common near the ocean shore and in dry montane forests to the subalpine, but is rare in lowland rain forests. Like all pines (member species of the genus Pinus), it is an evergreen conifer. …

Uses Construction The common name "lodgepole pine" comes from the custom of Native Americans using the tall, straight trees to construct lodges (tepees) in the Rocky Mountain area.[7] Lodgepole pine was used by European settlers to build log cabins.[7] Logs are still used in rural areas as posts, fences, lumber, and firewood.[7] Shore pine pitch has historically been used as glue.[7]

Tree plantations of Pinus contorta have been planted extensively in Norway, Sweden, Ireland and the UK for forestry, such as timber uses. In Iceland it is used for reforestation and afforestation purposes.[36] It is also commonly used for pressure-treated lumber throughout North America. … Emblem

Lodgepole pine is the provincial tree of Alberta, Canada.[41] …

0 notes

Text

Quick lil post to give people a headsup that im hoping to get these plant mini prints listed on my etsy for the equinox! (march 20th) as well as my black&grizzly bear prints and ravenstag sticker restock.... we'll see :-)

#tho to be fair the rose will not be up because i killed the block by accident.#etsy update#shop update#mini prints#handmade paper#linocut print#linoleum block#relief print#alberta#calgary#mohkínstsis#treaty 7#native plants#botanical art#im procrastinating cutting out stickers by making posts#the scissors make my knuckles hurt after awhile

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Countryside Tree Farms & Landscaping Aspen Trees Calgary

Countryside Garden Centre is locally owned and independent garden centre and landscaping company located in De Winton AB. We service Calgary and Okotoks area, plus southern Alberta.Along with our beautiful greenhouse plants, we propagate from seed, graft and grow softwood tissue, from plant material in the chinook zones from native and proven hardy sources. Our hardy plant material has been used in various projects throughout western and southern Alberta and Eastern British Columbia

0 notes

Text

Bonita Bohnet- Bachelor of Arts, Faculty of Native Studies

Bonita Bohnet (she/her) is Métis and is completing her Bachelor of Arts in the Faculty of Native Studies. She is in her fifth year and final term at the University of Alberta. Bonita has been an intern in the Humanities 101 Program (HUM) within CSL for three years.

Can you trace your involvement with CSL?

When I first became involved with CSL, I participated in the Humanities 101 class in 2019. The Humanities 101 Program offers free, non-credit university education to people who face barriers to post-secondary education by valuing their lived experiences and knowledge. From there, I became a university student. After my first year of university, I interned for Humanities 101 and have been with the program for three years. So, it’s been wonderful being able to do that. Besides my involvement with HUM, I’ve also taken CSL courses within my studies.

Why did you decide to take your first CSL course?

I took my first CSL course by accident! So, I’m also in the Indigenous Governance and Partnership Certificate, embedded in the Faculty of Native Studies. I took a mandatory course, Colonization and Decolonization, to fulfill the certificate requirements. I was informed that there was a CSL component only once I started the class. It was my first CSL class, and it was great!

What CSL placements have you completed?

I completed my placement with Métis Crossing while I was enrolled in the Colonization and Decolonization course. We were placed in groups and tasked with creating an interactive activity that could teach people about the different aspects of the Métis Nation of Alberta Constitution. As part of my group, we developed a Geocaching activity, where people can learn about various aspects of the Constitution and Metis history while exploring. Geocaching is like a scavenger hunt. It’s a worldwide activity with an app attached to it. While people are out in nature, they can hide little notes or trinkets and upload the location coordinates to the free app. This included an official kit from Geocaching that included tags and other materials that Métis Crossing could put in their vicinity. People participating in Geocaching can go there and engage with it and feel like, “Oh, there’s something we can customize!” So, that was a fun one, and I enjoyed it.

Last spring of 2023, I was in the course CSL 370: Special Topics and Community Engagement, Uprooting and Embedding Knowledge. This one was really great, too! We went to various community organizations, from Boyle Street to Kindred House. We also met with Elders, and a lot of our experience was outdoors. It was really about getting to know people and building relationships with those who access and are involved in the services, so it was more relational. We did a lot of gardening, which was related back to the land. For instance, we made seed bombs, planted seeds, walked in the forest, and explored urban gardens.

I am currently in my third CSL course, a capstone course for my certificate in Indigenous Governance in Partnership, and currently completing a placement with the Keewatin Tribal Council in Northern Manitoba. The Tribal Council represents multiple First Nations communities, and they are in the process of starting their land claims and negotiations with the government. We are working with them to form a partnership. They wanted to know about different First Nations governments, the scope of their law-making power, the kinds of government models used, and fiscal relationships. I’m analyzing the Tlicho Nation from the Northwest Territories, in which they are the first First Nations to have a land claim and government settlement. I analyze many documents and articles and prepare briefing notes for them, supporting them to know what other governments have done and what works and doesn’t so that they can better understand the next steps forward.

What was your favorite CSL placement, and why?

My favorite placement was with the CSL 370 course. Even though we didn’t go to one specific place, I do a lot of relational work, so I liked how it was very community-engaged and outdoors, which recognizes the knowledge gained from working with the earth. I think relational work is significant because the knowledge and creation of collective and community engagement is often forgotten in traditional academia, which tends to focus more on just writing papers. So, I find myself doing a lot of relational work and enjoy it! We visited many places, met many people, and learned their stories. It was great to share knowledge. I really enjoyed this one!

Did CSL change your ways of thinking about certain things, and how?

My first exposure to CSL, taking the Humanities 101 class in the community, was about the value of one’s lived experiences, collective and collaborative learning, and the opportunity to come and participate without specific prerequisites. That’s what really made me feel like, you know what, even though I don’t have a high school diploma, I do have a lot of knowledge, and I can attend university as well. So, coming to university and being in the Humanities 101 Program and seeing the diversity, lived experiences, and knowledge of so many people has taught me so much. People come to learn from what we facilitate, but I’ve learned so much from them because they have so much knowledge, which is great! That’s really changed how I think about academia. I’ve reflected on questions like whose knowledge is valued? Who is valued? What’s considered knowledge, and how do we get knowledge?

What was the most important/memorable lesson you learned?

I learned a lot from the people who participated in the Humanities 101 program. They have a wealth of knowledge, and that’s the most memorable lesson I’ve learned. People participating in the Humanities 101 Program are often excluded, ignored, and dismissed by society. They have so much knowledge to offer, and it’s about relationship-building and learning from others.

How has CSL impacted your academic and/or personal life?

CSL has impacted me academically in terms of what I see as valuable. It's not about being in class and having someone tell you things to memorize. It’s about learning and thinking critically, questioning and challenging things. How I see and engage with the university as a whole has changed. I’ve learned that it’s very exclusive and institutional, which I wasn’t aware of before. When I started working with the Humanities 101 Program and with communities, I got a voice to say that the exclusive nature of traditional academia isn’t serving people, and we need to work toward change.

Within the Humanities 101 Program, is there an experience or story that stood out to you?

For someone who didn’t have a high school diploma and had barriers and challenges to getting a post-secondary education, going from a participant from HUM to becoming an intern at one level and then switching to a high-level intern, where my experiences and knowledge are valued, gave me a sense of self-worth and inspiration. Somebody once told me that a person from the class remembered me! I was like, what do you mean? They said I was remembered because I was a critical thinker and challenged people. Because of what I was questioning and engaging with people, I became memorable to them.

How would you sum up your experience with CSL in one sentence?

CSL has given me the opportunity to learn something new every day.

#csl#ualberta#yeg#facesofcsl#uofa#edmonton#ualbertacsl#community service-learning#students#growth#get involved#getinspired#highlights#features#popularblog

0 notes

Text

Western Red Columbines (Aquilegia Formosa)

West Coast Native Flora Wednesday #1

🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙

Western Red Columbines, scientifically known as Aquilegia Formosa (not to be confused with Aquilegia canadensis, which is the wild eastern Columbine), is a 1 meter tall, herbaceous, taprooted perennial that belongs in the family Ranunculaceae (The buttercup family!).These flowers bloom from June to August, so best get your outdoor gear ready for some Columbine photoshoots, but where are they?

Home is where the Red Columbines are (Habitat/Range & Ecology) :

Western Columbines exist ranging all the way from Alaska down the coast to California, and in Canada, it extends to Alberta. These Columbines primarily like their environments moist, beyond that they like a bit of openness and partial shade, but they will grow just about anywhere. In forests is where they seem to most enjoy being, but they also grow in sub-alpine (and alpine) meadows, roadsides, woodlands, beaches, and river banks, just about in damn near any environment.

Surprisingly, despite looking wildly similar and often being mixed up visually, Western Red Columbines and Eastern Wild Columbines have completely different ranges that haven't overlapped ever. So if you live on the west end, you definitely have an Aquilegia Formosa, and if you live on the other end, you've most certainly got an Aquilegia canadensis.

Link for range map of Western Red Columbines (Though its doesnt show the specific regions of each Province/State):

What's in the name? :

Birds play a big part for these plants. Firstly, both the common and scientific name make references to birds! Columbine comes from the Latin word for "dove." because of how the spurs look like a mass of doves gathering around in a circle. The spurs also coincidentally looking like talons led to the name Aquilegia derived from the Latin word for "Eagle." The second part of the scientific name (Formosa) rightfully dubs the plant as " Beautiful" once again in Latin.

(These look like chickens, but i swear they're doves. I just suck at drawing birds <//3 )

Exclusive Pollinators:

Names, however, are not where birds' involvement with these plants ends. In between the 5 brightly hued petals are 5 (Sometimes 4) long modified tubular petals that have become nectarine spurs (for Western columbine, these spurs are straight). Far back inside the spurs, they secrete sweet nectar, which is high in sugar and attractive to many pollinators. In the north, where the flower has slightly shorter spurs, this may be insects like butterflies and hawkmoths. However, in the southern regions, a major pollinator for the longer spurred flowers is hummingbirds! These flowers were believed to have gone through what's called 'Co-evolution' , however, for the columbine and many other long-spured flowers, this is more of a one-sided ordeal. Usually in a co-evolution relationships both parties (Columbine and Hummingbirds) would grow and adapt as a result of the other, Hummingbirds would evolve longer beaks to reach further in the nectar spurs, and the flowers would develop longer spurs. This was however discovered to be NOT what's happening instead it seems only the columbine had grown longer spurs to accommodate the pollinator shift from bees to hummingbirds, and after a while would no longer continue evolving longer spurs.

Regardless, when a hummingbird attempts to drink some nectar, they will end up also bumping their head on the extended stamen of the flower. This along with the jittery movements of the bird will result in pollen being deposited on top of their head and when they go to drink from another columbine they will end up bumping their pollen dusted head against the pistil of the flower effectively pollinating it.

🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙🙘✦🙙

Long story short, Columbines are pretty neat! And if you have any Hummingbird friends (or even some insect friends), you wanna take care of, grow some columbines for them! Instead of putting out those hummingbird feeders that can grow bacteria and ferment, making your buddies sick. I've heard they're quite easy to grow, too, so why not give a shot once the Autum rolls in?

Happy Native Flora Approcating!!!

#West Coast Native Flora Wensday🌿#Native plants#Native flowers#West Caost Native Plants#Red Columbines#Aquilegia Formosa#ecology#botany#I really have no idea what to tag tbh#gardening#???????=>$>#Hnnng so eepy#I didnt consider the fact thag it would take me so long to reserch and write these up every couple of days lmao#I am a slow ass writer adhd is a bitch#I also have a shit ton of other stuff to do but plants first#Anyways goodnight <33 Gonna dream of stupidly long necterine spurs :))

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Pros And Cons of Planting Dwarf Alberta Spruce At Home

The dwarf Alberta spruce (Picea glauca) is a small, slow-growing evergreen conifer that is a popular choice for landscapes and ornamental gardens. Sometimes referred to as the dwarf white spruce, this compact pyramidal tree is a genetic variation of the white spruce tree native to Alberta, Canada. The dwarf Alberta spruce reaches a mature height of only 1-7 feet with a spread of 1-5 feet. Its…

View On WordPress

0 notes