#agent osip

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Agent Osip, Lift Operator

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seren's Studies: Odd Squad UK -- "Villain of the Year" Episode Followup, Part 1

Well...I had initially wanted to put these out right away, but...frankly, I needed a break. And I am, in fact, an impatient child who did not want to put 480p screenshots on here for y'all to squint at. I'm nearsighted, people. Let's not make it worse.

Anyway, let's get started on this next batch of episodes. This one covers "Villain of the Year", which is sort of like "A Job Well Undone" but with a legitimate villain and a Chinese-knockoff award. I just...need something good. I need to get the taste of watching a nuclear war movie out of my mouth.

Below the break, if you will.

Ignoring the horror vibes Captain O is giving off here...

Your writer for this episode. Athena's written for a few things before, though nothing in the kids realm. Seems to be mostly comedy stuff, as far as I'm aware, which is good, but good comedy does not a good Odd Squad episode make. It's merely a fraction of what makes it good.

Waddlin' down to the river to pray for this one.

There's been talk of if Odd Squad could be used to make good horror, and honestly, I'm inclined to say yes. This shared ability is a good example.

"Have you heard of the domino effect?"

*tight-ass smile*

MmmmmmmIdontlikewherethisisgoin'.

...All the agents?

The entire precinct?

Even the ones that aren't, y'know, Investigation agents?

God, if this is how Britain does things, I fear for if they ever make Odd Squad Down Under.

I actually forgot Osip (Ossip?) was the name of the first lift operator in "Lift Off". I'm hoping their name is a play on "gossip" because if not then I will be sorely disappointed.

"And tell Osgood to bring a snack with him!"

Ah yes, stress-eating. To be honest, it's a fair reaction if (nearly) every member of her precinct is out fighting a boss that can fall and squish you to death.

I like this divvying up of side characters. I'm not too keen on allowing one-shots to come back for a season that spans a mere 12 episodes, though. Depending on how the episode's written, we could either get a ton of information on the one-shot in question, or jack shit.

Hey. Hey. Remember when there was a villain lair at the bottom of the ocean or something, where all the villains gather?

You remember there was a Villain Network in Season 3?

Yeah, this "Villain Club" thing basically blew all that shit out of the water. What's the Villain Club? What are the requirements for entry? Are there only 21 villains in town total? Are there some that aren't in the club? You don't know!

I'd have liked it if there were a Villain Magazine to contrast with Odd Squad's own magazine, to be honest. But alas, it's not meant to be.

See, this is why criminals steal money. In any given large town, who the absolute fuck wants a paper crown and a rosette for bing-bong bullets off a house or kidnapping the children? You do bad things, you're not getting a paper crown and a rosette no matter how many times you do it. You want something else. A new TV. Money. Something valu-

...I take it back. I take it all back. You win, and you get what I have to assume is some kind of a steroid.

Granted, it's a special kind of drug valu-

...I take that back. It's some kind of a device that boosts a villain's power.

Causing oddness in one go, though...I would imagine "in one go" would vary depending on what villain got the power boost.

*long sigh* I really just want another drug allegory like there was in "Set Lasers to Profit". That was fun. I liked that. Do it again!

The man can already wield that power better than Oprah and it's already been halfway in.

Maybe he's related to her. Distant cousin or something. He does use it for shits and giggles.

Stinky Sock Sue and I'm willing to bet her odd power is making agents stink.

I dunno guys, we might have a contender for "villain with the stupidest schtick of all time".

...

WAIT HOLD UP, GOOPY GUS IS BACK???????? WHEN THE FUCK DID BRO MOVE TO BRITAIN????????????????? YOU CAN'T JUST BRING BACK A CANADIAN VILLAIN LIKE THIS IT NEEDS E X P L A N A T I O N . ATHENA WHAT IN THE S H I T .

Oh God...if she's got the balls to bring back old villains like this, this episode might actually turn out good. Bar's raised a couple inches higher. Just a couple inches.

See, Bubbly Bob is portrayed as harmless, but in actuality, bubbles could do a serious number on an agent. Trap them in one and they can go flying. Trap them in one and they could suffocate. Team up with a water-based villain and trap an agent in a water bubble and they could drown.

He's...probably too much of an idiot for all that, though.

Ah. He's not an idiot. I rest my point.

Nearly halfway in and I'm finding that Osip could be interchangeable with any other notable side character and there would be absolutely no difference.

I don't mind her as a character, but she's a one-shot. You can do a lot with that in a single episode, but Athena's not dragging out any sort of potential.

Wow, Osgood's solid. He should consider acting.

Yeah, you can tell this is a girl who absolutely despises milkshakes and has no whimsy large enough to do the "blow through the straw and make your milk bubble up" thing.

HE DOESN'T TAKE THE HAT OFF EVEN WHEN HE'S PLAYING SOCCER?????

At this point it's like a Linguine-Remy situation goin' on and I wish we had an episode dedicated to that.

See, this could easily lift Osgood up, up and away. No problem.

But y'know...clearly we gotta have some level of realism, and this is where the ding-dongs decided to place it.

There's...no gadget to clean up the mess? They have to use mops?

Aw God, Athena...what the fuck are you DOING, honey?

OHP SHE DID IT. SHE SAID IT. SHE SAID THE LINE.

...Doesn't hit the same as when Oprah did it...BUT SHE SAID THE LINE!!!!!!!!

"Maybe next year I'll get four votes!"

The man's got good sarcastic wit, I'll give him that.

going door-to-door as what are essentially campaign managers

election day's coming up

Ooooooooh I know this is Britain but ooooooOOOOOOOOH did those sorry sacks know what they were doing.

He's a socially awkward nerd. No wonder why no villain wants to vote for him!

(Hey, they would be the ones to care about that stuff.)

Waitwaitwait, hold on...so Dottie's setup on that island was temporary? She has an actual home?!?!?

Okay, props to Athena for not bringing another past-season villain that I would demand another explanation for...but this is just as painful as when Season 3 did it. "Mission O Possible" specifically, since it brought back the Noisemaker.

THEY ARE OUTRIGHT FUCKING MAKING UP LIES ABOUT THE CANDIDATES AND THIS IS 100% PURELY AN ELECTION DAY EPISODE OR YOU CAN BITE MY ASS.

We've had election episodes before, but not many are willing to pull off direct parallels like this. If you think about it a certain way, this is like an Independent trying to get votes when everyone only cares about the two existing parties and the candidates in those.

"That's not a sock, that's a napkin on a foot!"

I just found my new favorite phrase when buying socks. Thanks, Athena!

Is this...is this just like a recap episode of all the villains we've seen thus far? Is this to remind us that they exist and aren't forgettable? Because I could name a good chunk of villains in this season by name alone.

(On to Part 2!)

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

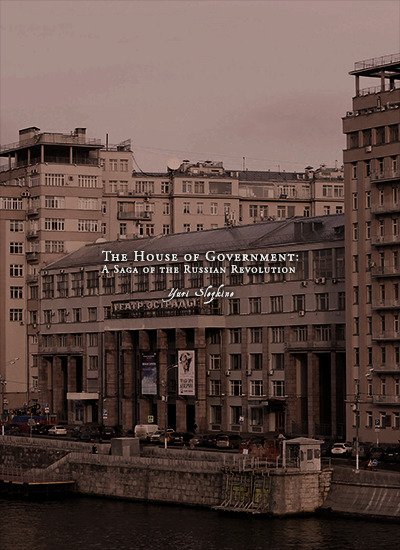

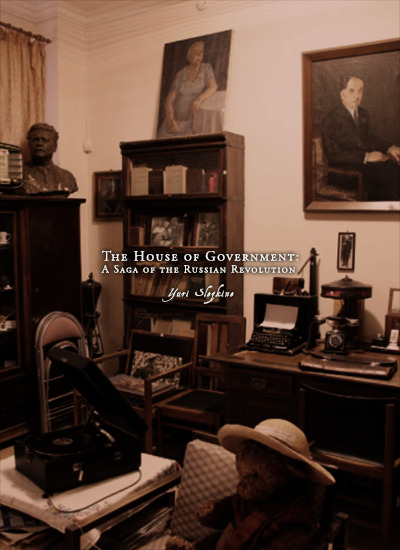

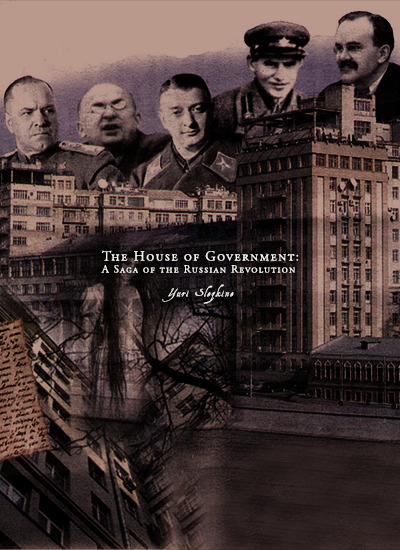

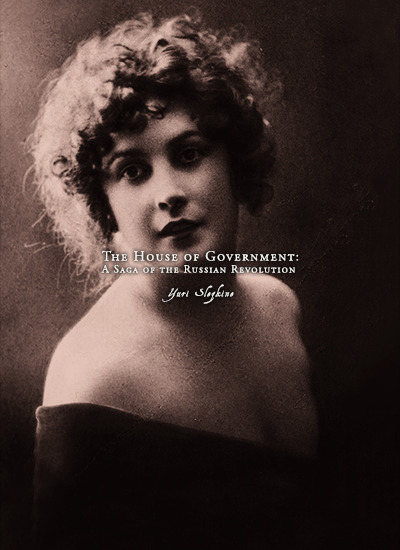

Favorite History Books || The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution by Yuri Slezkine ★★★★☆

In the House of Government, some residents were more important than others because of their position within the Party and state bureaucracy, length of service as Old Bolsheviks, or particular accomplishments on the battlefield and the “labor front.” In this book, some characters are more important than others because they made provisions for their own memorialization or because someone else did it in their behalf.

One of the leaders of the Bolshevik takeover in Moscow and chairman of the All-Union Society for Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries, Aleksandr Arosev (Apts. 103 and 104), kept a diary that his sister preserved and one of his daughters published. One of the ideologues of Left Communism and the first head of the Supreme Council of the National Economy, Valerian Osinsky (Apts. 18, 389), maintained a twenty-year correspondence with Anna Shaternikova, who kept his letters and handed them to his daughter, who deposited them in a state archive before writing a book of memoirs, which she posted on the Internet and her daughter later published. The most influential Bolshevik literary critic and Party supervisor of Soviet literature in the 1920s, Aleksandr Voronsky (Apt. 357), wrote several books of memoirs and had a great many essays written about him (including several by his daughter). The director of the Lenin Mausoleum Laboratory, Boris Zbarsky (Apt. 28), immortalized himself by embalming Lenin’s body. His son and colleague, Ilya Zbarsky, took professional care of Lenin’s body and wrote an autobiography memorializing himself and his father. “The Party’s Conscience” and deputy prosecutor general, Aron Solts (Apt. 393), wrote numerous articles about Communist ethics and sheltered his recently divorced niece, whose daughter wrote a book about him (and sent the manuscript to an archive). The prosecutor at the Filipp Mironov treason trial in 1919, Ivar Smilga (Apt. 230), was the subject of several interviews given by his daughter Tatiana, who had inherited his gift of eloquence and put a great deal of effort into preserving his memory. The chairman of the Flour Milling Industry Directorate, Boris Ivanov, “the Baker” (Apt. 372), was remembered by many of his House of Government neighbors for his extraordinary generosity.

Lyova Fedotov, the son of the late Central Committee instructor, Feodor Fedotov (Apt. 262), kept a diary and believed that “everything is important for history.” Inna Gaister, the daughter of the deputy people’s commissar of agriculture, Aron Gaister (Apt. 162), published a detailed “family chronicle.” Anatoly Granovsky, the son of the director of the Berezniki Chemical Plant, Mikhail Granovsky (Apt. 418), defected to the United States and wrote a memoir about his work as a secret agent under the command of Andrei Sverdlov, the son of the first head of the Soviet state and organizer of the Red Terror, Yakov Sverdlov. As a young revolutionary, Yakov Sverdlov wrote several revealing letters to Andrei’s mother, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (Apt. 319), and to his young friend and disciple, Kira Egon-Besser. Both women preserved his letters and wrote memoirs about him. Boris Ivanov, the “Baker,” wrote memoirs about Yakov’s and Klavdia’s life in Siberian exile. Andrei Sverdlov (Apt. 319) helped edit his mother’s memoirs, coauthored three detective stories based on his experience as a secret police official, and was featured in the memoirs of Anna Larina-Bukharina (Apt. 470) as one of her interrogators. After the arrest of the former head of the secret police investigations department, Grigory Moroz (Apt. 39), his wife, Fanni Kreindel, and eldest son, Samuil, were sent to labor camps, and his two younger sons, Vladimir and Aleksandr, to an orphanage. Vladimir kept a diary and wrote several defiant letters that were used as evidence against him (and published by later historians); Samuil wrote his memoirs and sent them to a museum. Eva Levina-Rozengolts, a professional artist and sister of the people’s commissar of foreign trade, Arkady Rozengolts (Apt. 237), spent seven years in exile and produced several graphic cycles dedicated to those who came back and those who did not. The oldest of the Old Bolsheviks, Yelena Stasova (Apts. 245, 291), devoted the last ten years of her life to the “rehabilitation” of those who came back and those who did not.

Yulia Piatnitskaya, the wife of the secretary of the Comintern Executive Committee, Osip Piatnitsky (Apt. 400), started a diary shortly before his arrest and kept it until she, too, was arrested. Her diary was published by her son, Vladimir, who also wrote a book about his father. Tatiana (“Tania”) Miagkova, the wife of the chairman of the State Planning Committee of Ukraine, Mikhail Poloz (Apt. 199), regularly wrote to her family from prison, exile, and labor camps. Her letters were preserved and typed up by her daughter, Rada Poloz. Natalia Sats, the wife of the people’s commissar of internal trade, Izrail Veitser (Apt. 159), founded the world’s first children’s theater and wrote two autobiographies, one of which dealt with her time in prison, exile, and labor camps. Agnessa Argiropulo, the wife of the secret police official who proposed the use of extrajudicial troikas during the Great Terror, Sergei Mironov, told the story of their life together to a Memorial Society researcher, who published it as a book. Maria Denisova, the wife of the Red Cavalry commissar, Yefim Shchadenko (Apts. 10, 505), served as the prototype for Maria in Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem A Cloud in Pants. The director of the Moscow-Kazan Railway, Ivan Kuchmin (Apt. 226), served as the prototype for Aleksei Kurilov in Leonid Leonov’s novel, The Road to Ocean. The Pravda correspondent, Mikhail Koltsov (Apt. 143), served as the prototype for Karkov in Ernest Hemingway’s novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Doubting Makar,” from Andrei Platonov’s short story by the same name, participated in the building of the House of Government. All Saints Street, on which the House of Government was built, was renamed in honor of Aleksandr Serafimovich, the author of The Iron Flood (Apt. 82). Yuri Trifonov, the son of the Red Army commissar and chairman of the Main Committee on Foreign Concessions, Valentin Trifonov (Apt. 137), wrote a novella, The House on the Embankment, that immortalized the House of Government. His widow, Olga Trifonova, would become the director of the House on the Embankment Museum, which continues to collect books, letters, diaries, stories, paintings, photographs, gramophones, and other remnants of the House of Government.

#historyedit#litedit#soviet history#russian history#european history#history#nanshe's graphics#history books

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Secrets We Kept by Lara Prescott review – an impressive debut

The fascinating tale of how the CIA plotted to smuggle Doctor Zhivago back into Russia drives an enjoyable debut

At the height of the cold war, the CIA ran an initiative known as “cultural diplomacy”. Following the premise that “great art comes from true freedom”, the agency seized on painting, music and literature as effective tools for promoting the western world’s values, and funded abstract expressionism exhibitions and jazz tours. But when it came to the country that produced Tolstoy, Pushkin and Gogol – a nation that, according to a character in Lara Prescott’s impressive debut novel, “values literature like the Americans value freedom” – the focus was always going to be on the written word. And her subject, the part the CIA played in bringing Boris Pasternak’s masterpiece Doctor Zhivago to worldwide recognition, was the jewel in cultural diplomacy’s crown.

In 1955 rumours began to circulate that Pasternak, hitherto known largely as a poet, having survived a heart attack and Stalin’s purges, was ailing and politically compromised but had nonetheless managed to finish his magnum opus. The sweeping, complex historical epic – and simple love story – that is Doctor Zhivago had been a decade in the writing under the most adverse circumstances imaginable: the imprisonment of Pasternak’s lover, Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya; the death in the gulag of his friend and fellow writer Osip Mandelstam and the suicides of two others in his circle, Paolo Iashvili and Marina Tsvetaeva; constant surveillance and his own ill health. Because of its subversive emphasis on the individual and its critical stance on the October Revolution, no publishing house in the Eastern bloc would touch it. When an enterprising Italian publisher sent a secret emissary to Pasternak’s dacha, in miserable desperation the writer handed it over, with the inscription “This is Doctor Zhivago. May it make its way around the world.” The manuscript was smuggled out to West Berlin – and the CIA made their move. Their aim was clandestinely to publish a Russian edition and return it to its homeland.

This is remarkable raw material for a novel. Prescott’s book, the subject of a legal row after Pasternak’s great-niece Anna Pasternak accused her of plagiarising her own biography of Olga, has all the ingredients for a spy thriller. It has a great cast of characters and a wealth of historical detail to be mined, plus the potential for insight into a bizarre and compelling point in our history and, of course, a love story. Prescott’s first achievement is her identification of these qualities: weaving them into a complex and involving narrative is altogether more of a challenge, but she works hard and with considerable ambition to meet it, and entwines a surprising love story of her own invention.

Like Doctor Zhivago, her novel follows a number of characters’ viewpoints. There is Pasternak himself and Olga, whom we first encounter as she is arrested, pregnant with his child, and imprisoned for refusing to divulge what she knows of the book. Irina Prozdhova, the Washington-based émigré daughter of a man murdered by the Russian regime, has been newly recruited by the agency; Sally Forrester is an experienced spy and honeytrap or “swallow”. Both these women have secrets of their own. And, most engagingly, we hear from the communal voice of the typing pool of the CIA’s Soviet Russia division.

There are a couple of male walk-on parts, including, in the novel’s only properly bum note, CIA agent Teddy Helms, who courts Irina and whose brief section on a mission to Britain is so full of missteps (his MI6 contact referring to “the little Mrs”, English fish and chips being breaded rather than battered) that one begins to wonder if the author intends it as a riff on his obtuseness. And indeed there is a sly joke against the patriarchy woven into the plot: at a time when women were at their most invisible, expected to confine themselves to traditional roles, they made the best spies. It is the female characters who carry this adventure, from the pragmatic, loyal, indestructible Olga to the marvellous typists. With their Virginia Slims and Thermoses of turkey noodle soup, they make up a kind of smart, gossipy Greek chorus whose commentary begins and ends the novel.

Prescott may not be an accomplished prose stylist, but her characterisation is often deft. Her Pasternak is vividly flawed: histrionic, lachrymose but stubbornly lovable. Her research is thorough if occasionally a little too visible, and the portrayal of the love between Olga and Pasternak is poignant and convincing. Sold in 25 countries, with film rights optioned, The Secrets We Kept is set to be a publishing phenomenon; but more importantly, it is a thoroughly enjoyable read.

• Christobel Kent’s A Secret Life is published by Sphere. The Secrets We Kept is published by Hutchinson (£12.99).

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I poeti traducono il mondo ignoto. E lavorano contro chi rimpiazza il pensiero con l’intrattenimento”: dialogo con Eleanor Wilner

Intervistando i grandi poeti anglofoni, una percezione potente. La Storia sta serrando le mascelle. Se ne sente lo schiocco, da Sydney a New York, da Toronto a Los Angeles. E la poesia resta come una torcia tra i denti oblunghi della Storia. A illuminare i perduti, a dare una scorta di parole ai perdenti. Eleanor Wilner (1937; photo di copertina di Jacques-Jean Tiziou) è tra i grandi poeti statunitensi del tempo presente, ricca di riconoscimenti (il MacArthur Fellowship e il National Endowment for the Arts, ad esempio), stesso carisma di Charles Wright, per capirci. Già editore di The American Poetry Review, autrice di sette libri di poesia (gli ultimi: Reversing the Spell; The Girl with Bees in Her Hair; Tourist in Hell), la Wilner mescola la spregiudicatezza lirica americana con una profonda conoscenza della mitologia classica. Eleanor attraversa diverse tradizioni (decisivo, ad esempio, il rapporto con l’opera di Osip Mandel’stam) per dare forza inedita ai suoi versi. Già tradotta in Italia (due anni fa con il volume Tutto ricomincia; è installata nell’antologia Nuovi nuovissimi mondi, curata da Maria Cristina Biggio per Raffaelli) e costantemente insediata nelle antologie più rappresentative della poesia americana, la Wilner è, a suo modo – sguardo cosmico, raffinatezza etica – un poeta ‘civile’, dal salutare impeto ‘morale’. “Oggi uno dei ruoli della poesia, in un periodo di riverbero della voce dei mass media e di crude caricature, è preservare uno spazio (piuttosto che un mercato) per la voce del singolo, un linguaggio per la sfaccettata complessità dell’essere umano e un filo concreto per connettersi umanamente”, ci ha detto. Nell’era della tracotanza, si dirà (la Wilner ha parole critiche verso la Presidenza Trump), la poesia, la cui natura è l’ambra e il cristallo, spalanca altri mondi possibili. Si pone, tra gli abissi, come una stele d’oro. “Chiamare le cose col giusto nome”. Ecco, infine, ci dice la grande poetessa, la necessità della poesia. Mettere ordine tra le cose. Preparare lo spazio alla salvezza. Oggi leggere i poeti, sprofondare nelle loro parole, è una urgenza sanitaria.

Mi dica che cos’è la poesia?

Negli ultimi mille anni poeti e studiosi hanno discusso su questa domanda senza trovare alcun accordo. Evidentemente ciò suggerisce che la natura della poesia si sottrae dall’essere definita dal momento che siamo noi che scriviamo poesia. Shelley, poeta inglese del Romanticismo, disse la famosa frase “i poeti sono i legislatori misconosciuti del mondo”. Non credo sia così. Credo che i poeti siano i traduttori del mondo misconosciuto e quel mondo alternativo è quello che rispecchia e illumina quello conosciuto, ed è sia un custode della memoria collettiva sia, in modo malleabile, un agente di cambiamento.

Perchè sente l’esigenza di scrivere poesia?

Scrivo poesie perchè mi viene chiesto di scriverle e perché è l’unico modo con cui posso vedere ciò che non può essere visto in altro modo; ha la funzione di guida interiore. E anche perché, quando ci si perde nella scrittura, si prova un profondo piacere sia nella scoperta che nella temporanea perdita dell’io noioso.

Che valore ha la politica, l’etica nella sua poesia? La poesia è un mezzo per capire il mondo? Qual è la sua visione del mondo?

Credo che la poesia sia il nesso tra il singolo e la società. Nessuno ha una vita o una coscienza immaginativa separata da un contesto più ampio. L’epoca in cui viviamo vive in noi, come il passato: nel nostro DNA, nella nostra lingua, nella storia, nella memoria individuale e collettiva. Perciò politica ed etica sono intrinseche all’immaginazione poetica che rivela e valuta ciò che accade. Penso che la poesia sia un mezzo per vedere il mondo, quindi la mia visione, qualunque essa sia, si può trovare nella mia poesia e non può essere scardinata da quest’ultima in termini più astratti. Solo la metafora può esprimere la complessità che incarna. Dato che ogni visione è parziale e limitata e che il mondo è in costante movimento e cambiamento quella visone è, per natura, in costante evoluzione, aperta e provvisoria.

So che ha tradotto Euripide. Che influenza hanno i classici sul suo lavoro? Quali autori la ispirano, se ce ne sono?

Posso dire che considero la mitologia classica della tradizione greco-romana una ricca fonte di memoria della cultura occidentale, dalla quale cresce la mia poesia. Secondo me la mitologia ha spesso offerto un modo per approcciare la storia della nostra epoca, un modo per creare prospettive, per ampliare il nostro senso dell’individuo fondendolo con le figure extraindividuali del nostro patrimonio occidentale, classico, biblico e letterario, che condividiamo. E, nell’usare il passato come uno specchio lontano dalla nostra situazione, trovo che queste figure (Medusa, il Minotauro, Penelope, ecc.), ripresentandosi nel presente, arrivino a cambiare le antiche leggende in modo da renderle più flessibili, più rilevanti nella nostra situazione attuale. Perciò possiamo prendere in prestito il potere di queste figure, insieme alle forme che ci hanno accompagnato attraverso i secoli, e usarlo per cambiare quegli atteggiamenti legati ai primi passi della storia, usando così il passato ancestrale per garantire un futuro più libero. Riguardo alle influenze, ce ne sono di antiche e di moderne, sono molteplici. Come tutti gli scrittori contemporanei sono in debito con molte culture e letterature. Ho vissuto in Europa e in Asia e ho viaggiato molto. Leggevo letteratura europea prima di conoscere completamente quella americana. Sono stata condizionata anche dalla mia opinione riguardo al Grande Silenzio, l’assenza di molte donne e il loro prevalente anonimato nella letteratura del nostro passato, quel silenzio per me è una fonte: la voce ignota delle donne del passato che emerge da quel silenzio, spinte dalla forza di una prolungata repressione in gran parte dimenticata, taciuta.

Qual è il suo rapporto con gli altri poeti americani (o scrittori)? Che valore ha la solitudine nel suo lavoro?

Scrivo poesia e insegno letteratura da oltre cinquant’anni perciò la mia vita e il mio lavoro si sono profondamente intrecciati e si sono arricchiti grazie a molte generazioni di poeti e scrittori. Credo che la mia musa sia l’amicizia, dato che sono tutti questi incastri di vite e immaginazioni che fungono da ininterrotta ispirazione per la mia scrittura, insieme al mio sdegno per la guerra e le atrocità e per le bugie bigotte che le giustificano. Il mio lungo percorso di vita mi ha messo in contatto con molte generazioni di scrittori quali colleghi, studenti e amici e quando è la poesia ciò che condividi devi saltare i convenevoli e arrivare al punto. Certo, si scrive in solitudine; quello spazio tranquillo è essenziale eppure in qualche modo, quando entro in quello stato che invita all’immaginazione poetica, questo si apre su uno scenario densamente e significativamente popolato; sembra che più si scende nella propria vita interiore, tramite la natura, il linguaggio e le storie che condividiamo, e più si trovano le sfumature dell’essere umano.

Che ruolo ha attualmente la poesia negli Stati Uniti? Che ruolo ha il poeta nella società civile? In che modo è cambiata l’America da quando Donald Trump è stato eletto Presidente?

È difficile generalizzare riguardo un paese come l’America, eterogeneo dal punto di vista etnico, geografico e territoriale e su una poesia che si accorda con questa diversità. Ecco alcuni pensieri per scalfire la superficie di una realtà complicata e sfuggente. Oggigiorno uno dei ruoli della poesia, in un periodo di riverbero della voce dei mass media e di crude caricature, è preservare uno spazio (piuttosto che un mercato) per la voce del singolo, un linguaggio per la sfaccettata complessità dell’essere umano e un filo concreto per connettersi umanamente. La poesia opera contro una cultura pop che rimpiazza il pensiero con l’intrattenimento, che alimenta fantasia e falsità e fornisce importanti spunti di riflessione per contrastare i media, superficiali e manipolatori sia nel commercio che nella politica. La poesia tenta di risvegliare i sentimenti, di dare importanza alla vita davanti al torpore dell’essere esposti a una continua raffica di violenza esplicita che ci desensibilizza: videogiochi, blockbuster, servizi su sparatorie nel proprio paese e su guerre estere. Ho sempre pensato che l’immaginazione morale dia al poeta un ruolo nella società civile, un pensiero visto con diffidenza nella nostra poesia tradizionale del passato, ma un nuovo e recente senso di vulnerabilità storica ha portato alla poesia americana la consapevolezza di quanto l’individuo sia ingarbugliato in forze di più ampio respiro politico e sociale. La storia è diventata personale, come è sempre stata per i poeti di Baghdad ad esempio, o per i poeti di colore in America.

Quando le persone sono privilegiate e non si sentono minacciate dalla storia si permettono il lusso di ignorarla e addirittura di pensare, a torto, che non avrà nessun effetto su di loro; né pensano al coinvolgimento di chi paga per i loro privilegi. Ma oggi la nostra poesia popolare non è più “confessionale” né ha la mentalità chiusa che, tranne per eccezioni eclatanti, aveva una volta. Essa è sempre stata eclettica, esplorativa e ha abbracciato molte scuole e stili ma non è mai stata così aperta e socialmente impegnata, così etnicamente diversa e rappresentativa di una popolazione eterogenea come adesso: una resistenza che sboccia a dispetto del clima tossico del momento. Dall’attacco dell’11 settembre e dal crescendo di violenza derivato dalla piaga delle stragi abbiamo assistito alla crescita di una poesia americana socialmente impegnata, un cambiamento che si è propagato vista l’elezione sconcertante di un uomo totalmente inadatto a ricoprire la massima carica dello Stato e che è sia una disgrazia che un disastro: incarna palesemente il peggio che c’è in noi e lo ha reso visibile a tutti. È ridicolo, eppure la sua presenza ha rovinato la massima carica, ha avvelenato la vita pubblica e il dialogo, ha contribuito a promuovere violenza e crimini generati dall’odio e ha messo in pericolo sia i nostri diritti di cittadini sia i nostri rapporti con i paesi alleati e il resto del mondo. Credo che la maggior parte di noi stia un po’ impazzendo a causa dell’attuale senso di pericolo morale e fisico e la poesia è diventata uno dei modi con cui cerchiamo di mantenere un equlibrio mentale e di chiamare le cose col giusto nome.

Le interessa la letteratura italiana? Ha contatti con poeti italiani contemporanei? Che idea ha dell’Italia?

Sono sollevata nel passare a queste domande. Come posso descrivere in poche parole il lungo e tenero rapporto che ho con l’Italia, un paese che ho visitato spesso e con il quale sento una profonda connessione? Con una risposta breve posso solo scalfire la superficie: amo il modo in cui il mondo del passato esiste parallelamente a un presente pieno di vita. Amo il vostro paesaggio antropico, con campagne coltivate e cittadine storiche in collina, la cultura geniale e soprattutto il calore, la generosità e l’ospitalità degli amici che avevo qui, che hanno rappresentato per lo più la mia esperienza diretta con gli italiani e che sono anche estremamente gentili quando commetto qualche errore buffo nel tentativo di parlare italiano. Ammiro anche lo spirito meravigliosamente anarchico che avete e che penso sia un dono, un inno alla vita e al sapersela godere. La mia conoscenza della poesia italiana contemporanea, dopo Eugenio Montale, è tristemente insufficiente perchè nonostante io ami il potere musicale ed espressivo della lingua italiana il mio italiano è elementare perciò dipendo dalle traduzioni. Per questo motivo ho letto principalmente narrativa moderna, per me più accessibile. La mia scrittrice italiana preferita è Elsa Morante, soprattuto il suo romanzo La Storia, che è stato per me la prima opera importante a parlare interamente di coloro che non fanno la storia ma la subiscono. Il libro, ambientato durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale in Italia, è stato senza dubbio una rivelazione e un’ispirazione. Mi vergogno della mia incapacità di tradurre poeti italiani eppure ho avuto la fortuna e l’onore di poter contare sui miei traduttori in Italia: Eleonora Chiavetta, che è anche una cara amica da molti anni, alla quale ho spesso fatto visita a Palermo e che ha pubblicato una collezione bilingue delle mie poesie legate alla mitologia: Voci dal Labirinto; le signore del Laboratorio di traduzione di poesia di Roma: Maria Adelaide Basile, Fiorenza Mormile, Ann Maria Rava, Anna Maria Robustelli, Paola Splendore e Jane Wilkinson che hanno pubblicato un’edizione bilingue intitolata Tutto ricomincia, edita da Fiorenza; e Maria Cristina Biggio le cui traduzioni delle mie poesie compaiono nella sua antologia: Nuovi Nuovissimi Mondi: Antologia di Poesia Americana Canadese (Raffaelli).

(trad. it. di Edera Anna De Santi)

*

In tempo di guerra

Mosche, catturate nella saliva dei vivi alberi, un giorno saranno preziosi, rivestite nell’ambra – proprio così il passato appare al presente, come una gemma in perfetta conservazione, l’oro indurito di ieri, una reliquia attraverso cui scintilla il sole di oggi.

Ma quelli che sono catturati nell’appiccicosa saliva del tempo attuale, probabili insetti contro di loro, che lottano nella melma, affogano lentamente nella massa, innumerevoli, anonimi morti… finché l’atrocità diventa mondana, i sensi insensibili dalla liturgia della pura ripetizione…

lasciateci, allora, guardare questo piccolo volo disperato, bloccato dai piedi, e poi, nelle sue battaglie, impigliato interamente in un globo di saliva, le sue ali pesanti come un angelo di ottone, finché non è ancora alla fine, un punto scuro nella bolla di linfa che stilla dall’albero abbattuto nella foresta marchiata per il mulino.

Quanti millenni passeranno prima che la lacrima d’ambra, questo pendaglio, portando il suo carico di perduti adornerà la vanità di un’altra creatura, la mosca il fossile di una specie non più presente sulla Terra, la Terra stessa una macchia nel cosmo dove le galassie sono cardate come il cotone su un pettine e tirate fuori a distanza dove viene fabbricato un nuovo tessuto e brilla nella luce di innumerevoli, ardenti soli.

*

Mezzogiorno a Los Alamos

Per voltare una pietra con il suo bianco che si contorce di sotto, per forzare il disco dell’eclisse – al culmine si arrotola nell’occhio cieco: a questa malvagia necessità veniamo dal tempo oscuro dei dinosauri che strisciavano come lava che bolle sulla crosta scoperchiata della terra, e oscillano le loro minuscole teste sopra immense tonnellate di carne, cervelli non più grandi di un pugno chiuso per resistere allo squarcio bianco nel cielo il giorno in cui i bagliori del sole battevano sul reliquiario del museo, tornarono i ghiacciai, bruciò il Sinai prati neri – felci appassite, cellule disgiunte, ricombinate e follemente moltiplicate, alberi enormi crollati a terra, la vita cauta ha abbandonato la speranza, un bruco si è irrigidito nell’erba. Due scimmie, beccate mentre copulano, fanno un bambino mutante che si sveglia alla luce del sole chiedendo, sua madre strappato dalla nuova enorme testa che ha forzato lo stretto canale del parto.

Come se costretti alla ripetizione e per dissotterrare ancora fuoco bianco nel cuore della materia – fuoco cerchiamo e fuoco parliamo, i nostri pensieri, benché eleganti, sono fuoco dal primo all’ultimo – come sentinelle appostate per vigilare ad Argo sul segnale di fuoco che passa da roccia a roccia da Troia a Nagasaki, eco trionfante del rogo mura della città e prologo al massacro ancora veniamo – scandito il cielo per quel bagliore luminoso, i nostri occhi diventano bianchi per guardare il segnale di fuoco che termina l’epico – una linea maledetta con la cesura, la pausa, per il segnale di pace, o la prova per il silenzio.

Eleanor Wilner

________________________________

Q. What do you think is poetry?

A. For the last thousand years, poets and scholars have been arguing about that question, with no agreement in sight. Clearly this suggests that poetry’s nature is one that resists definition, as do we who write it. The Romantic British poet Shelley famously declared that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” I don’t think so. But what I do think is that poets are the translators of the unacknowledged world, and that alternate world is one that reflects on and illuminates this one, and is both a keeper of communal memory and, adaptively, an agent of change.

Q. Why do you feel the need to write poetry?

A. I write poems because they are given to me to write, and because it is the only way I can see what can’t be seen another way, and serves as an inner guide. And, because, when one is lost in the writing, there is deep pleasure in both discovery and the temporary loss of the tiresome self.

Q. What is the value of politics, of ethics in your poetry? Is poetry a vehicle for a world view? What is your vision of the world?

A. Poetry, I believe, is the nexus of the singular and the choral, and no one has a life or an imaginative consciousness that is separate from a larger one: the times we live in live in us, as does the past—in our DNA, our language, history, personal and collective memory. So politics and ethics are intrinsic to the poetic imagination, which reveals and evaluates what is going on.

I do think poetry is a vehicle for a world view, and therefore whatever vision of the world I have would be found in the poetry, and is not extractable from it in more abstract terms. Only metaphor can express the complexity it embodies. Since all vision is partial and limited, and the world is in constant motion and flux, that vision is, by the nature of matter, constantly evolving, open and provisional.

Q. I’ve seen you translated Euripides. What influence do classics have in your work? Which authors influence you today, if any?

A. I can say that I consider the Classical mythology of the Greco-Roman tradition to be a deep source of Western cultural memory, out of which my own poetry grows. For me, mythology has often provided a way of approaching the history of our own time, a way of creating perspective, of enlarging our sense of the personal by merging it with the transpersonal figures of our Western heritage—Classical and Biblical and literary––that we share.

And, while using the past as a distant mirror on our own situation, I find these figures (Medusa, the Minotaur, Penelope, etc.), when they return come to change the old stories in ways that make them more adaptive, more relevant to our current situation. So we can borrow the power of those figures and forms that have accompanied us through the centuries, and use it to change the attitudes bound to earlier stages of history—and so to use the ancestral past to leave the future more open.

As to influences, they are ancient and modern and multiple–and I am indebted, as are all contemporary writers, to many cultures and literatures. I’ve lived in Europe and in Asia, and have traveled widely; I read European literature before I knew much that was strictly American. I’ve also been influenced by what I think of as The Great Silence, the absence of most women and the anonymous majority from the literature of our past, and that silence is a source for me—the unrecorded voices of past women that rise out of that silence, propelled by the force of long suppression, so much left out, unsaid.

Q. What is your relationship with other US poets (or writers)? What is the value of solitude in your work?

A. I have been writing and teaching poetry and literature for over 50 years, so my life and work have been deeply entangled with and enriched by several generations of poets and writers. I think my muse is friendship—for it is all these interlocking lives and imaginations that are the ongoing inspiration of my writing life, along with my outrage at war and atrocity, and the pious lies that justify it. The long trajectory of my life has put in me in touch with several generations of writers as colleagues, students and friends, and when poetry is what you share, you get to skip the small talk and cut to the chase.

Of course, one writes in solitude; that quiet space is essential, yet somehow, as I enter that state which invites poetic imagination, it opens to a densely and significantly populated landscape; it seems the deeper you go into your own inner life, by way of nature and the language and stories we share, the more you find everybody.

Q. What role has poetry today in the United States? What role does the poet have in civil society? How has America been changed since Donald Trump was President?

A. I put together these three questions because they seem interconnected. It is hard to generalize about a country as diverse–ethnically, geographically and regionally–as America, and a poetry that matches that diversity. A few thoughts to scratch the surface of a complicated and slippery reality.

One role of poetry today is that, in a time of mass media’s amplified noise and crude caricatures, it preserves a space (rather than a market) for the living, singular voice, a language for the nuanced complexity of being, and a deep channel of humane connection. Poetry works against a pop culture that replaces thought with entertainment, that feeds fantasy and falsity; it provides deep reflection to counter the shallow, commercially and politically manipulative media; it attempts to awaken feelings, to make life matter against the numbing of a constant blizzard of desensitizing exposure to graphic violence through video games, blockbuster film, and media’s daily reports of mass shootings at home and wars abroad.

I have always thought that moral imagination gives the poet a role in civil society, a view which was distrusted in our mainstream poetry in the past, but a new and recent sense of historical vulnerability has brought to American poetry an acute awareness of how enmeshed the individual is in larger political and social forces. History has become personal, as it always has been to the poets like those of, say, Baghdad, or poets of color in America.

When people are privileged and don’t feel threatened by history, they have the luxury of ignoring it, even thinking, falsely, that it has no deep effect on them, nor they a complicity in who pays for their privilege. But our mainstream poetry today is no longer as “confessional” or as insular as, with notable exceptions, it once was. It has always been eclectic, exploratory, and embraced many schools and styles, but never has it been so open and socially engaged and ethnically diverse and representative of our mixed population as it is now–a flowering of resistance to the toxic climate of the moment.

We have, since the attack of 9/11, and the home-grown violence of the plague of mass shootings, seen this growth of an American poetry of social engagement–a change that has been deepened by the bewildering election of a man totally unfit for high office who is both a disgrace and a disaster; he transparently embodies all that is worst in us, and has put it on public display. He is ludicrous, yet his presence has degraded high office, poisoned public life and discourse, helped encourage hate crimes and violence, and endangers both our rights as citizens and our relations with our allies and the rest of the world. I think the majority of us are being driven a little mad by our current sense of moral and physical peril, and poetry has become one of the ways we attempt to keep ourselves sane, and to call things by the right name

Q. Are you interested in Italian literature? Do you have relationships with living Italian poets? What idea do you have of Italy?

A. I turn to these questions with relief. But how can I say in a few words the long and loving relationship I have with Italy—a country I have often visited, and feel a deep connection with. In a short answer I can skim the surface: I love how the world of the past exists alongside a vibrant present; I love your humanized landscape, with its cultivated countryside and historic hill towns, the brilliant culture, and most of all, the warmth and generosity and hospitality of the friends I’ve had there—which has been my experience of Italians generally, who are also extremely kind about the laughable mistakes I make in trying to speak the language. I admire, too, the wonderfully anarchic spirit there, and what seems to me a gift for praising life by knowing how to enjoy it.

My knowledge of contemporary Italian poetry, after Montale, is woefully deficient, because, though I love the music and expressive power of the Italian language, my Italian is rudimentary, so I am dependent on translation. For that reason, I have more access to and have read more modern fiction: my favorite Italian writer is Elsa Morante, especially her novel History, which for me was the first major work to speak entirely for those who don’t make history but suffer it. The book, set during WWII in Italy, was a revelation to me, and an influence, I feel sure.

I am ashamed about my inability to translate Italian poets as I have been so lucky and privileged in my translators in Italy: Eleonora Chiavetta who is also a dear friend of many years, whom I have often visited in Palermo and who published a bi-lingual collection of my myth-related poems: Voci Dal Labirinto; the women of Laboratorio di traduzione di poesia in Rome: Maria Adelaide Basile, Fiorenza Mormile, Ann Maria Rava, Anna Maria Robustelli, Paola Splendore e Jane Wilkinson who published a bi-lingual edition Tutto ricomincia,edited by Fiorenza; and Maria Cristina Biggio whose translations of my poems appear in her anthology: Nuovissimi Mondi: Antologia di Poesia Americana Canadese.

L'articolo “I poeti traducono il mondo ignoto. E lavorano contro chi rimpiazza il pensiero con l’intrattenimento”: dialogo con Eleanor Wilner proviene da Pangea.

from pangea.news https://ift.tt/2GICMMm

0 notes

Photo

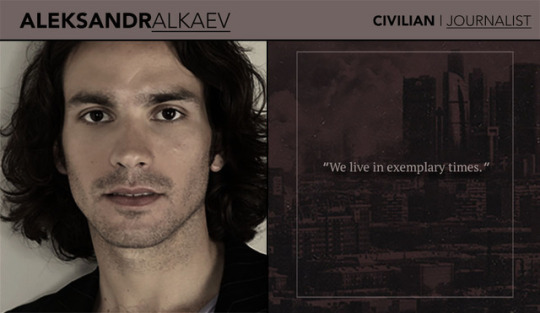

Name: Aleksandr ‘Sasha’ Ivanovich Alkaev Age: 40 Ability: Retrocognition/Precognition Faction: CITIZEN as a JOURNALIST Faceclaim: Santiago Cabrera Availability: OPEN

THE STORY || CW: Death

Aleksandr’s childhood was spent shepherding his family’s sheep through sunburned grass in the foothills of the Altai Republic. The son of farmers, he was expected to uphold the custom of being a farmer himself. But he wasn’t particularly good at this sort of work. It came naturally to his two younger sisters; as though the herd was an extension of their nervous systems. This life involved understanding and predicting the movements of an inconsistent mass. Of containing it. Every bleat of a sheep, every weary shift in mannerism – they understood; Aleksandr was witless. He understood history. He understood that the earth they trod was an agglomeration of aluminum and calcium and iron and steel, of decisions good and bad, and that the delicate balance of life and death swayed each day like a proverbial pendulum. He couldn’t compete with that. And so rather than attempt to change something already tied to an invisible string, he elected to press his fingers to the stony earth, to stare into the sunset and inhale its story; as he learned literacy, he elected to document it.

Aleksandr was nothing like his brother. 8 minutes Aleksandr’s senior, Osip was his superior in every discernible way. He was smarter, more handsome, and he could bend fate. He could tell the future. He could sense a rattlesnake coiled in the grass before any lamb could. He would guide the herd away before they spooked into indiscernible chaos. Despite their differences, and despite his jealousy, Aleksandr loved his brother. It was hard not to like Osip. He was expected to lead their family out of poverty. One night, before their 16th birthday, Osip came to Aleksandr in a panic. His visions were gone. He couldn’t see. Anything. Aleksandr, Osip’s lighthouse, assured him that it was only a passing phase. He should think nothing of the problem and rest; sleep would short-circuit him back to normalcy. That night, a wandering vagabond crept through the window and killed Osip in his sleep.

When Aleksandr rose, he was all agony. His visions and Osip’s visions came at him like liquid daggers, all at once. His mind was an iron maiden. He couldn’t escape the explosive marriage of his and his brother’s abilities, nor could he escape the crushing ache of losing half of his heart. When he wasn’t writhing for one reason, he was writhing for the next. As time passed, as Aleksander spent his days bedridden, he learned to control his abilities, he learned to fathom his angst, and he learned why. Yorick Spektor, aged 27 had heard of Osip, the Champion of Altai. Like every other Russian, he also knew the legend of the twin princes. Angry with circumstances in Russia, and Human-Vila conflict, Aleksandr’s murder was supposed to grant Osip with the final power needed to control time and to fix Russia. But Yorick hadn’t anticipated the legend being fake, and he hadn’t anticipated murdering the wrong twin. In his time bedridden, Aleksander repeatedly watched Yorick killing his brother through his visions, but he had no evidence. So he wrote the evidence. At his request, his parents provided Aleksandr with a typewriter, and he recalled the circumstances of Osip’s death with picturesque detail. The narration impressed policemen, and it was more than enough to convict Osip’s murderer.

The next five years of Aleksandr’s life was filled with sorry stagnation. In his family’s farm, he saw Osip’s ghost everywhere. He saw the two of them talking, laughing, spreading goat cheese over sunflower oil crackers. Aleksander also saw himself continuously spinning this same depressed pattern if he didn’t change. So at 21, he moved to Moscow, where he continued writing and made a small fortune selling crimes to newspapers. Eventually he was recruited by the Moscow Times and became their golden goose.

THE CHARACTER

Aleksandr hates his job. He derives little joy from telling stories anymore; he feels that recording the past does nothing to prevent heartbreak, only exacerbate it through details. Unfortunately for him, he’s very, very good at it. Fate dealt him a blessing he didn’t even want. Despite his aversion to attention, his writings have made him famous. And so, Aleksandr writes because he must. When he’s not writing, he seeks mind-numbing agents. With the whole world in your head, any means of dulling the noise is a blessing. Aleksandr drinks often, he paints furiously, and he goes on long walks with Chopin blasting through headphones. His heart has healed for the most part, but his past left him a cynic. He loves people and things rarely and cautiously, but when he cares, he cares with every fiber of his being; with everything he is and more.

CONNECTIONS

Foma Alexandrovich Zharkov - Aleksandr still remembers jolting awake, a vision tearing him from sleep with incessant urgency. An experiment would kill Moscow if Aleksandr didn’t interfere. A human granted with the ability to kill on sight. Aleksandr found Project Medusa cowering naked at the edges of a power plant. He clothed him, named him, and brought him home, where he taught him to disguise himself as a blind man. He became Aleksandr’s live-in editor, learning braille to make the act all the more convincing. It took Foma a long time to shed his defenses, but eventually the two of them grew extraordinarily close. Aleksandr finds himself laughing at Foma’s crude humor and feeling pangs of loss when they’re apart. He feels often that he needs Foma just as much as Foma needs him.

Vladimir Kazimirovich Mikhaylov - The first time Aleksandr touched Foma’s cold skin, he saw Vladimir’s eyes in his brain. The secrets of Project Kudzu spilled into his skull quickly and violently. A dam splitting open. The water crashing through. It’s no secret that Kudzu terrifies him, but this fear sparks a bravery that flickers large and bright. He won’t let anything happen to Foma. He won’t let Kudzu take him away from him. Aleksandr has all the tools to expose Kudzu, and he would if he weren’t so afraid of exposing Foma to the world.

Kim Seung-gi - The circumstances of their friendship are his doing entirely. In his first few months as a Muscovite, he was hungry and freezing. He saw her in a vision, saw her composure, saw what she could do to help him. He bridged contact and she aided him instinctively, giving him food and survival tips. She’s the one who suggested he sell his writings to the police. The two became fast friends and much later, business partners. As far as he can tell, she has no idea about his retrocognition and he intends to keep it that way.

Raisa Mikhailovna Nazarowicz - Aleksandr saw Raisa coming to Moscow in a vision and couldn’t contain himself. It was all he could think about for the weeks leading up until it happened. Her books had been some of his favorite methods of escapism, and it’d be a lie to say that he wasn’t madly in love with her work. Though Aleksandr hasn’t formally met Raisa yet, he follows her in his visions. Honestly he feels guilty and a bit dirty for it, but it fills his heart with excitement to know that they share the same city. He’s worried about the day they meet because he’s certain his composure will betray him.

Rashid Javed Bashir - Aleksandr didn’t know Rashid when he saw him being killed. Grotesquely. A few minutes after his vision, he befriended Rashid in a bar and felt his heart sink. The guy is so nice. He’s so genuinely good. Aleksandr doesn’t know when his vision will come true, or what can be done to prevent it, or if it can be prevented, but he feels it incumbent upon himself to try.

[[ More Connections ]]

ETC

Aleksandr loves his family and wants the best for them. Each month, he sends a hefty check back home; with the money, his family has been able to purchase three sheepdogs, a larger barn, and more lavish home. Aleksandr also visits every other weekend and often shepherds the herd with his two sisters. When he returns to Moscow, he brings back all kinds of goat cheese; smothered in honey, blended with chives, with lavender. He has it with his toast each morning.

Aleksandr is wealthy, but you wouldn’t be able to tell just by looking at him. He’s very modest in his wealthiness and gives a large portion of his paycheck to charity. Nevertheless, his home is large and well-furnished. He’s humble, but he still appreciates comfort.

Though he keeps his vila status as a highly-guarded secret, that doesn’t keep him from caring very deeply about the discrimination that vilas face in Moscow. Much of his journalism has to do with painting a sympathetic image of vilas and exposing crimes against them.

He hates museums. He feels that they’re just glorified cemeteries. Though objectively Aleksandr understands the appeal of appreciating old works of art, they just reek of death to him.

In his free time, Aleksandr likes to learn languages and paint. Aleksandr’s has two rooms in his home dedicated to painting, completely filled with canvases and expensive materials.

#santiago cabrera fc#superpower rpg#crime rpg#original rpg#lsrpg#c: aleksandr#aleksandr#open#openm#openc#male#civilian#all#connection: rashid#connection: raisa#connection: kim#connection: vladimir#connection: foma#retrocognition#precognition#santiago cabrera#wanted

0 notes

Text

Woke up this morning with the Blues. The Women’s March was outstanding, twice the size of Littlefinger’s Inauguration festivities and much more festive. But that was three days ago.

I need a better name for the Unmentionable One.

The man next to me in the Metro Elevator was talking on his cellphone in Russian. “Horror show, horror show”, he kept saying. Horror Show means “good” in Russian. I flunked Russian in high school but still remember a few words. Do Russian hackers control the Internet, or is it only a matter of time?

The Dumpster? Not quite.

Out on the Virtual Verandah this morning Memphis Earlene and Latte Woman drink White Russians, and speak in broken English with fake Russian accents . Boris and Natasha English.

Make America Great Again. Get rid of Moose and Squirrel. Report to Fearless Leader.

“In a cage fight, bet on the Russian,” says Latte Woman. “Agent Orange is a shameless liar and a natural born bully but Fearless Leader has steel teeth and KGB training.”

Agent Orange? Perfect.

“Can’t bet against America. Wouldn’t be right,” says Memphis Earlene.

“America’s a Fascist Dictatorship . All bets are off, ” I say.

” At least we have a Fascist Dictator who doesn’t read books,” says Latte Woman, who can always find a bright side.

Osip Mandelstam, 1891 – 1938

Our lives no longer feel ground under them. At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But whenever there’s a snatch of talk it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the ten thick worms his fingers,

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip, the glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses he toys with the tributes of half-men.

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels. He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes, One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries. He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

Post Inauguration Blues Woke up this morning with the Blues. The Women’s March was outstanding, twice the size of Littlefinger's Inauguration festivities and much more festive.

0 notes