#african cosmology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Palo Mayombe: Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality — Lawrence Talks!

“This complexity described in the Bantu-Kongo word for person, muntu is a ‘set of concrete social relationships ... a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being.’ The person is contextualized as a system participating in other systems, a pattern, a ripple that is sourced and from a source.”

— Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology 42

Dr. Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, a Congolese native and scholar of African religion, captures the essence of Kongo cosmology with this quote, and from this cosmological structure lies the roots of the African diasporic religion Palo Mayombe. Just as a person is “a system of systems; the pattern of patterns in being,” ancestral reverence and inclusion positions humans through a multitude of bodies that have come before them. Ancestral veneration is at the core of many African Diasporic spiritualities. Many individuals who grew up in traditional Christian churches are leaving beliefs of Christendom in search for traditional religions that help them connect with their ancestors. Religious and spiritual systems like Ifa, Santeria, Vodou and Conjure have been popularized, sometimes in negative ways by the media, but for the most part these are the spiritualities that people turn to first in their exploration of African traditional religions (ATR). And what is known of Palo Mayombe by the general public is not a large amount of information by any chance. A Google search locates some articles which picture Palo as the “dark side” of Santeria, which is far from the truth. However, to understand Palo as a distinct spiritual system outside of other African diasporic religion, one must understand its BaKongo cosmological foundations.

History of ancient Kongo cosmology

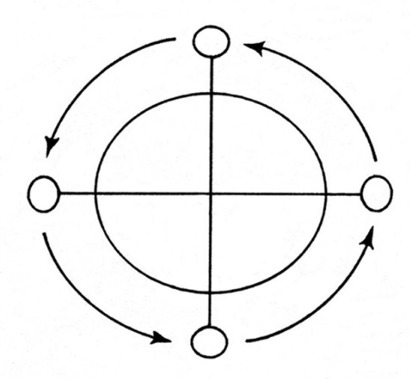

Figure 1: Kongo cosmogram (dikenga)

Fortunately, there is a symbol that captures the essence of Kongo cosmology. The Kongo cosmogram is a cosmological symbol that represents the very patterning of the life process. This symbol is a pre-colonial representation of the cosmogram, as it was conceptualized before European colonization in 1482[1]. It is called the dikenga in the KiKongo language, literally meaning “the turning;” it stands for the cycling of the sun around four cardinal points: dawn, noon, sunset, and midnight when the sun is shining in the world of the dead. Composed of a cross, a circle, and usually arrows, this symbol was found in Kongo material culture well before the contact of colonial Christianity and its cross motif. Anthropologist Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of Kongo art and religion, says that the “dikenga represents the ultimate graphic design, containing key concepts of Bakongo religious belief, oral history, cosmogony, and philosophy, and depicting in miniature the Bakongo conceptual world and universe” (Thompson 110). The key principle of the dikenga is that nothing ever survives “intact” because nothing ever survives in a fixed form. It is this spiral that is the basic element of Kongo spirituality.

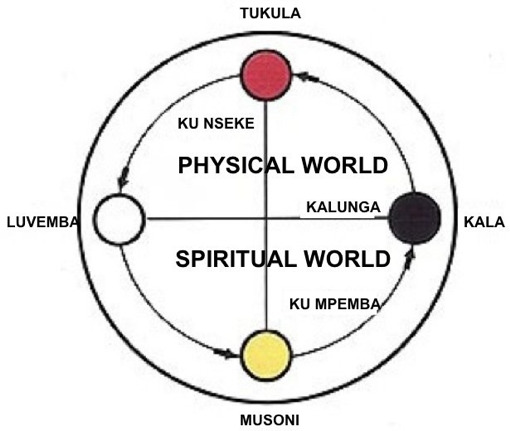

Figure 2: Dikenga

In his seminal piece on Kongo cosmology entitled African Cosmology of the Bantu-Kongo: Principles of Life & Living, Dr. Fu-Kiau explains the motion of the dikenga as the process of ancestralization, of dying and being reborn as an ancestor, through the heating and cooling of existence. This explanation of death and ancestralization is at the core of Palo Mayombe.

Origins of Palo Mayombe

Palo Mayombe is a Kongo derived religion from the Bakongo Diaspora. This religion was transported to the Caribbean during the Spanish slave trade and sprouted in Cuba mostly and in some places in Puerto Rico in the 1500. As the enslaved were forced out of their homelands, their beliefs went with them. Spanish colonialists in Cuba initiated a strategy in the sixteenth century to create mutual aid societies, called cabildos or cofradías, which served to cluster Afro-Cubans into different ethnic categories. This was a strategy of “divide and rule” designed to foster social differences across groups within the enslaved population so that they would not find a unifying focus through which to rebel against the colonial government. In contrast to the extensive blending of diverse African cultures that would be seen in Haiti and Brazil, Cuban cabildos contributed to rich continuations of Yoruba culture in the development of Santería and to largely separate developments of BaKongo beliefs in Palo Mayombe (Fennel). Elements of Catholic beliefs were incorporated into both Santería and Palo Mayombe due to the imposition of the Spanish colonial regime and the cabildo system.

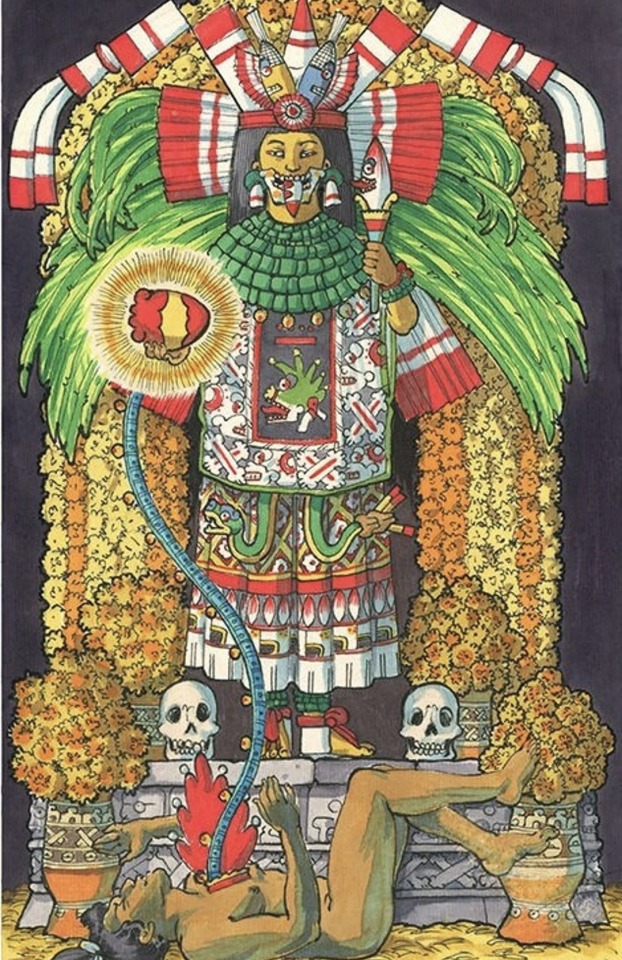

Figure 3 Palo Mayombe Ceremony

Palo Mayombe is very nature-based. Although most African Diasporic religions base rituals and practices in nature, palo (meaning “stick” or “segment of wood” in Spanish) solely depends on the material elements of nature to access the spiritual realm. In Cuba, the Kongo ancestor spirits are considered fierce, rebellious, and independent; they are on the “hot” scale of natural forces. Just as the importance of ancestralization mentioned above, the ancestors are present and inclusive in the practitioner’s life. Nzambi Mpungo is the greatest force in which paleros or paleras (Palo practitioners) call God. Nzambi Mpungo is literally the first ancestor, the initial iteration which all human life flows. Nzambi was viewed as having created the universe, people, spirits, transformative death, and the power of minkisi (ritualized, material objects). The Godhead was thus viewed as being removed from mortal concerns, and supplications were made instead to the ancestor spirits or the intermediary spirits created by Nzambi. Below Nzambi are the mpungus (elemental forces), the ancestors, and the spirits of natural forces (Bettelheim). Each mpungu is similar to an orisha from Yoruba culture due to shared African derived origins, but the two are not the same entity by any means. The mpungu are Afro-Cuban spirits, specific to their diasporic groundings and to the lands of the Diaspora. However, due to their origin

The material tools of Palo Mayombe

Cigars are used to enter into a trance-like state in order to more easily connect with spirits. Special machetes and chains are also used in spirit pots. Candles and rum are essential elements for any Palo ritual. The nganga is used to describe an iron cauldron filled with dirt and specialized sticks; this aids the palero/a in communication with the spirit. In Central America, Cuba and the Caribbean, this cauldron is called a Nganga-Prenda because the culture of modern day and the influence of Latin American's spiritualism in Palo Mayombe.

Figure 4: Prenda de Lucero

The Muertos are important entities in the Palo religion. The house of the dead is where the Palo spirits and the ancestors reside. As illustrated through the Kongo cosmogram above, Palo cosmology does not believe in death, but a continual cycle through various forms. It is the process of ancestralization that makes communication with the spirits of the dead accessible. In the Kongo tradition, ancestors, who have access to invisible forces, have the duty to protect the living. In exchange, the ancestor’s descendants have the obligation to take care of the ancestor’s memory and to venerate their earthly representation. This is why bones are another central tool in Palo. After a person has passed, the bones remain, and the bones carries the essence of a soul long after a person is gone. Bones are thus a sacred item in Palo Mayombe and are usually incorporated in Palo rituals. Usually an ancestor altar is an essential piece in the house of a palero/a, along with offerings of food, drink, and special itemize to venerate their ancestors.

Like many ATR’s and magical system, initiation of some kind is needed in order to practice. Guidance from the elders of the religion is highly encouraged, especially since the ways of the spiritual system is nothing like physical realms.

Palo Mayombe and Other Religious Connections

The influence of Palo Mayombe can be found in Central America, Brazil, and Mexico and in the United States. There are different sects of Palo (Palo Monte, Christian-based Palo, Jewish-based Palo) that come from different lineages and distinct engagements with the cultural environment around the practice. There is another Kongo-derived religion in Brazil is Quimbanda, which is a mixture of traditional Kongo, indigenous in India and Latin American spiritualism. Palo Mayombe is the engagement of Kongo influence in the Caribbean and the wider Diaspora. It has its own priesthood and set of rules and regulations. Rules and regulations will vary according to the Palo Mayombe house to which an individual has been initiated into.

Some people who practice Palo might mix other African-derived systems, like Ifa, Vodou, or Santeria, but Palo is a religion in its own right. For example, Yemoja, the orisha of the ocean and motherhood, may be seen as the same energy as Madre de Agua, the mpungo of the ocean and of motherhood. Although these spirits may have similar functions within the religions, they are two separate entites from particular cultural origins and with specific needs. It is quite common for spiritual seekers to be initiated in multiple religions, so it is of great importance to make sure each path is approached. Although there are other religious elements in Palo, it is all included in the practice and not separated within the religion. When Portuguese missionaries brought the message of Christianity to the Kongo/Bantu, the natives embraced it…while continuing their own native practices (Jason R. Young, Rituals of Resistance). So, this pattern of centripetal inclusion is also present in Palo Mayombe. As Iya TeeDee Oshún, a priestess of African diasporic religions, commented in a recent Facebook post:

“Palo is a beautiful road for those of us that it is for. It's also not just some shit you get done real quick before you ‘elevate’ because that's what Iya's spirit guide said to her in the shower. (Not making that up at all.) It's definitely not Iya nor Baba's "witchcraft pot" in the closet or behind the washing machine or above the grease stain in the garage. It's rarely what I hear when people talk to me in Yorabalese” (2019).

Iya’s mention of “Yorbalese” speaks to a common trend of people in the Diaspora making all of African-derived religions about orisha Ifa/Nigeria, but Palo is of the BaKongo Diaspora. The only system close in origin and practice to Palo is African American Hoodoo, which uses similar elements of the heating and cooling of herbs in spiritual work.

Conclusion

When one decides to take a step into the spirituality of Palo Mayombe, the journey really is a deep engagement with their ancestors and with the raw elemental forces of nature. It is a spiritual awareness that provides protection for the community and the self. The ancestors are the root of one’s existence; the root is the culminating point from which all life springs. This Afrocentric view of cosmology in which Palo Mayombe is grounded, deals with the consciousnesses of nature and of ancestry. Anyone who claims Palo Mayombe as a “dark” or unorthodox religion does not understand the Kongo origins of which Palo operates.

[1] The Kongo cosmogram is a pre-Christian symbol, but due to the iconography of the Christian cross, many people overlap their meanings

#Palo Mayombe Kongo-derived Afro-Cuban Spirituality#Palo#ATR#Congo#African Cosmology#Ancestry#African Religions#IFA#Palo Monte#Kongo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stars are not just distant specks of light in the African night sky but the guiding lights of mythology, culture, and spirituality.

Indigenous astronomical knowledge is recorded among many African tribes like the Dogon people of Mali, who have rich astronomical knowledge and are said to have made ancient observations of the planetary orbits of Saturn, Mars, Venus and Jupiter with her four major moons.

The traditional astronomical knowledge of the San and Nguni people of Southern Africa is recorded to have guided their agriculture irrigation systems and inspired their religious practices.

In many African societies, navigating life with the guidance of stars has birthed a rich reservoir of practical knowledge useful for timekeeping, agriculture, geography, record keeping and history.

As we explore culture and astronomy from the Chokwe perspective, we must state that we see the skies as we are. Our place on the planet determines our seasons, which affects what heavenly bodies we can observe. Perceptions of star patterns are influenced by the latitude of the observer, and from around 10 degrees south, the Chokwe had the geographical placement to observe and intertwine their star knowledge with their practices and identity.

For the Chokwe, stars tell the story of their people, weaving an intricate tale that forms the fabric of their identity. To the Chokwe, the life of a star is like the story of man, starting with birth, coloured by obstacles and triumph, before ending with the honour of death. The night sky has served as a source of wisdom, a symbol of royalty, and a connection to their revered ancestors.

To learn Chokwe astronomy, we must begin with Tangwa, the sun; Ngonde, the moon's phases; Litota, the stars; and Ntongonoshi, the universe in relation to the stars.

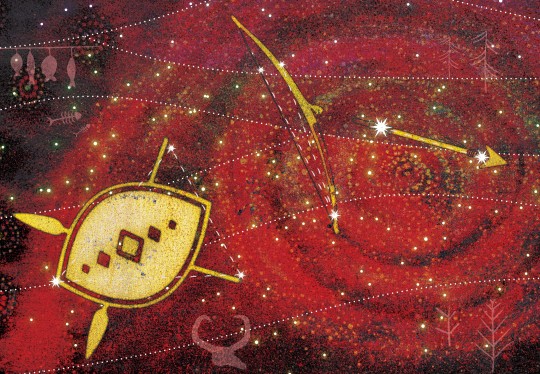

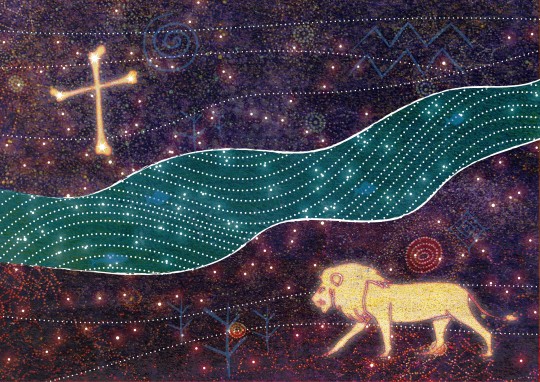

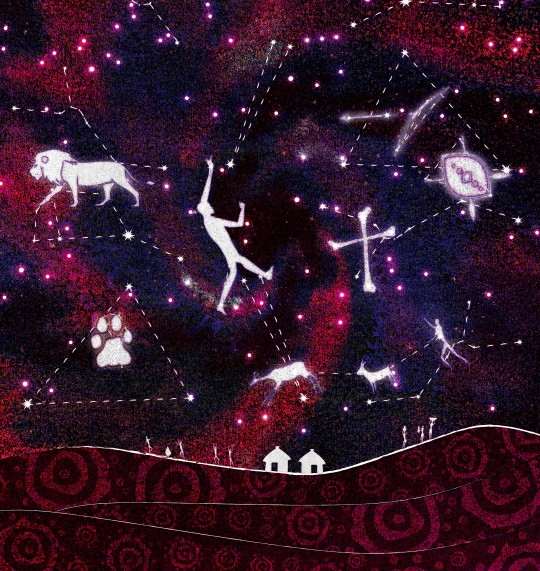

Royalty is a central part of Chokwe culture and is reflected in the sky where we see Ndumba, the lion that walks among the Tulamba - the ancestors, who guide his invisible stride in the Milky Way, leaving paw prints of litota in his path. The Chokwe people refer to the Milky Way as the Mulawiji or the Resting River, and it is used primarily as a star calendar and a compass. This shows an intimate knowledge of the skies as the orientation of the Milky Way changes considerably over the course of the year. Chokwe diviners call the Milky Way the Mulalankungu, which means the King's Road. Nkungu is the name of the great, ancient Chokwe king, and the term refers to him. The Milky Way is a significant part of divination stories, and the diviner's basket, or Ngombo, has objects that represent the stars that the diviner uses as symbols for interpretation.

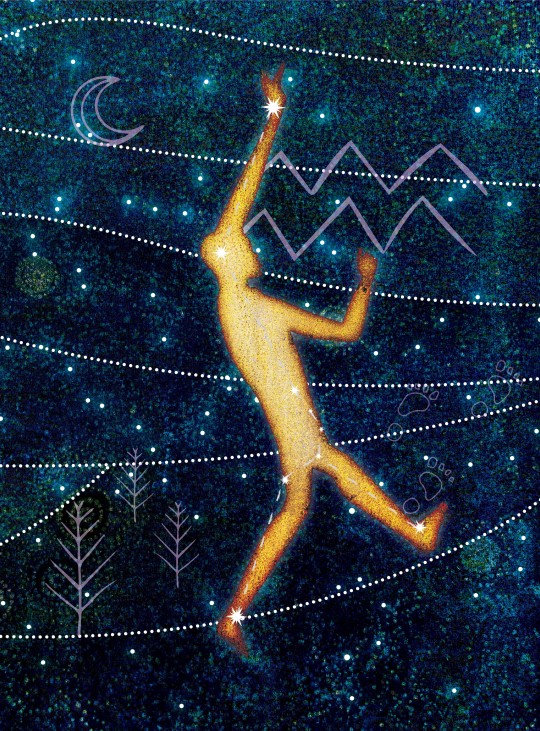

We are also introduced to Tutumwe Twa Mwanangana, which means 'Child of Wisdom' or 'Sending a Message to the Lord of the Land'. This constellation is depicted as four stars displaying a running, sweating messenger sent to announce the arrival of Mwenga, the new wife represented by the morning star, Venus. We see him spanning across four stars encapsulated in the three constellations of Bootes, Coronae Borealis and Herculis. The four stars, Alphecca, his head; Coronae Borealis accentuating the curve of his powerful hips as he runs; Herculis is his leg extended behind him and in his outstretched hand, Arcturus, the bright message of wisdom.

The beauty of Chokwe cosmology is endless, with serendipitous parallels to Western astronomy. For example, the hunter seen in Orion's Belt is also seen as a hunter by the Chokwe, and they call it Tujita Jita, symbolically interpreted as 'go to fight and always win'. Interestingly, for the Chokwe, the hunter is much closer to his dog in the constellation than in Greek and Egyptian mythology, where the dogs are in separate Canis Minor and Major constellations. Tujilika spans across three modern constellations of Triangulum Australe, Circinus and Centaurus. The symbolic meaning of Tujikila to the Chokwe people is 'the children are protecting you.'

The Nkungu – The Southern Cross represents the ancestors' bones shown by the four brightest stars connected in a cross, and this constellation guides the Mukanda, a circumcision initiation ceremony practised by the Chokwe.

The Seven Sisters, or The Pleiades, are Van Ava Nkungulwila, a lion's claws. Nkungulwila refers to the Nkungu clan and its people, and just as they are together on earth, they are together in the heavens, forming a relationship between heaven, earth, life, and death. The Chokwe see the heavens as their ancestors' home; in their cosmology, when people die, they are reborn in the lion's claws – The Seven Sisters. Considering this belief, it is fascinating to note that astronomers have recognised that this constellation is a star factory where new stars are created as the interstellar gas cloud contracts under the force of gravity. There are reddish stars within the constellation that astronomers recognise as dying stars in a supernova, which the Chokwe recognise as the Nalindele; a star whose season is over and is waning; this story is told in relation to an old wife.

Ancient Chokwe star lore, steeped in symbolism and cultural significance, aligns intriguingly with Western scientific discoveries. It's a reminder that despite diverse perspectives, our shared celestial heritage connects us all.

Modern Zambian society is embracing its traditional star knowledge in exciting ways. Young Zambians blend age-old wisdom with contemporary science and technology, forging a path towards the stars. A brief look can be taken at the enduring legacy of the Zambia Space Program of Edward Nkoloso, who coined the term Afronauts, which has come to embody a time when Zambians were bold and brave about exploring the wondrous mysteries of the universe.

The stars have a unique way of uniting us all, transcending borders, cultures, and time. Our fascination with the night sky is universal, but it's crucial to stay curious and remember that the cosmos is vast and diverse, just like the cultures it inspires. Whether you're gazing at the stars from the Chokwe heartlands of Northwestern Zambia or the bustling streets of Lusaka, we're all part of a timeless story that stretches beyond the horizon of our understanding. The stars above are the same stars that have guided us since time immemorial, reminding us of our shared journey through the great expanse of the universe.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Power of Call and Response in Art

#African aesthetics#African Cosmology#Ancestral Legacy#Art and Spirituality#Art as Healing#Balance and Harmony#Black Aesthetic#Call and Response#Community and Spirit#Creative Flow#Creativity as Devotion#Cultural Expression#Divine Connection#Double Consciousness#Energy and Art#Energy Work and Art#Faith in Art#God and Creativity#Healing Through Art#higher consciousness#Indigenous Wisdom#Oneness#Polyrhythmic Harmony#Reconnecting to Source#Ritual and Creation#Sacred Creativity#Sacred Practice#soul expression#Spiritual Art#Visual Storytelling

0 notes

Text

The Igala people believe that there are three different realms the human spirit will occupy in their existence; life after birth, adult life, and life after death. The ancestral spirits are very important to the people of the mortal world. It is the goal of the Igala people to maintain a balanced relationship with their ancestors by honouring them through rituals and offerings. If properly honoured, the ancestors will offer blessings and protection to the living. Ancestral spirits interact with the living in various ways. The spirits can be reincarnated as babies, or be called upon through masquerades.

In Igala cosmology, a human is not left to decide their destiny. It is believed that before a person is born, their destiny is decided by a choice they make before the creator, Ojo in the spirit world. When a person dies, it is very important that their body is treated with the proper ritual practices to ensure that they will make it to the spirit world; this is accomplished through a burial ceremony that has three stages. The first stage of the burial ceremony is called Egwu omi omi eji -When the body is placed into the grave. The second stage is the ceremony that takes place after the deceased is buried, called ubi eche. The third stage is Akwu eche, meaning the last shedding of tears. The third stage is where the Oloja masquerade is performed to say goodbye to the deceased

#igala#oloja#eche#akwu eche#igbo#yoruba#cosmology#igala cosmology#igala spirituality#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#brownskin#brown skin#africans#afrakans#african culture#afrakan spirituality#african spirituality

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even, After Death. We Know Our Place of Abode.

Somewhere in the skies, in a binary star system. We share return after our demise from this realm of existence. The Great Dogon people call this place, Yaa Tolo. In the Akan language, it is called Asa-Man (the nation of the creator), the source and origins of life.

Even after death, we know our place of abode. Do the Asians and Europeans know their true history and most especially, do they know their true origins?

#african history#cosmology#african culture#akan institute#akan#africa#history#history of the world#world history#ancient history#european history#west asia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Black History Month

The Metaphysical and Spiritual Contributions of the Dogon TribeAs we immerse ourselves in the rich observance of Black History Month, it is essential to explore not only the historical and cultural milestones achieved by African descendants but also the profound spiritual and metaphysical insights they have offered to the world. Among these contributions, the Dogon Tribe of Mali stands out,…

View On WordPress

#African Heritage#Black History Month#cosmology#Creation Myth#Dogon Tribe#Holistic Perspective#Interconnectedness#metaphysics#Sirius#Spirituality

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posted: 2/11/25

The Enchanting History of Love Magic Across Cultures

February has arrived with its whisper of roses, chocolates, and declarations of affection, the air is charged with the promises of love. Valentine's Day (Feb. 14th), though modern in its commercial veneer, is steeped in traditions that reach deep into human history. Among these, the practice of love magic—rituals, spells, and charms to attract, secure, or mend love—has traversed cultures, continents, and centuries. Let us embark on a journey to uncover how African, the African diaspora, Indigenous American, Asian, and European traditions have woven love magic into the tapestry of their spiritual and cultural practices.

Africa: Love and Spiritual Power Intertwined

In many African cultures, love magic reflects the profound connection between the spiritual and the mundane. Among the Yoruba people of Nigeria, practitioners of Ifá divination often called upon the Orisha Osun (Oshun) for love, beauty, and fertility. Offerings of honey, cowrie shells, and fresh water were made to Osun to invoke her blessings for harmonious relationships or to rekindle fading passion.

Meanwhile, across the continent, the use of botanicals for love magic was also widespread. In South Africa, for example, Sangomas (traditional healers) used herbs like "Umavumbuka" to foster reconciliation, harmony and emotional healing. These rituals often reflected the belief that love and harmony within relationships were essential for community balance, weaving personal desire into collective well-being.

African Diaspora: Love Magic in Survival and Resistance

As the African diaspora spread through the transatlantic middle passage, love magic was adapted and evolved within the crucible of multiple new environments. In the Americas, Hoodoo—an African American spiritual tradition—emerged, integrating African, Indigenous, Jewish and European influences. Practitioners used "mojo bags" filled with herbs, roots like John the Conqueror or Queen Elizabeth root and other personal items, powders or oils to draw love or fidelity. Honey jars, a sweetening spell to encourage affection and harmony, remain popular in contemporary Hoodoo practices.

In the Caribbean, Vodou and Obeah intertwined African cosmologies with local and European influences. In Haitian Vodou, for instance, Erzulie Freda, the lwa (spirit) of love and beauty, was and is still often petitioned for matters of the heart. Her rituals often included perfumes, pink and white candles, and luxurious offerings symbolizing sensual pleasure and emotional depth.

Global Indigenous Cultures: Love Magic in Harmony with Nature

For many Indigenous American cultures, love magic was less about control and more about alignment with natural energies. Among the Navajo, for instance, "beautyway" ceremonies invoked harmony and balance, which also extended to relationships. Love charms crafted from turquoise, or shells were believed to attract a compatible partner, resonating with the spiritual properties of these materials.

The Cherokee practiced rituals to strengthen bonds between lovers or to resolve conflicts. Songs, dances, and natural elements—such as cedar or sage—were integral to these ceremonies, symbolizing purification and renewal.

Indigenous peoples outside the Americas also have their own rich traditions of love magic. Among the Sami people of Scandinavia, noaidi (shamans) practiced rituals that included the use of drums and joik (a traditional form of song) to invoke spiritual assistance in matters of love and relationships. These practices were deeply tied to the natural cycles and spirits of the Nordic landscape.

In South America, the Quechua and Aymara peoples of the Andes incorporated love magic into their spiritual practices. Coca leaves, a sacred plant, were often used in divination to seek guidance about romantic relationships or to attract a desired partner. Rituals performed at sacred sites, such as mountains or lakes, were believed to align the participants with Pachamama (Mother Earth) to ensure harmony in love.

Indigenous Australian cultures often intertwined love magic with Dreamtime stories, the spiritual and temporal framework of their worldview. Rituals might have included sand drawings, chants, and symbolic offerings to attract or strengthen love, aligning the participants with the ancestral energies of the land.

Asia: The Alchemy of Love

Asian cultures have also long embraced love magic, often blending it with spiritual and philosophical traditions. In China, Taoist love spells focused on harmonizing yin and yang energies within partnerships. Charms inscribed with auspicious characters or infused with essential oils were used to attract romantic opportunities or sustain marital bliss.

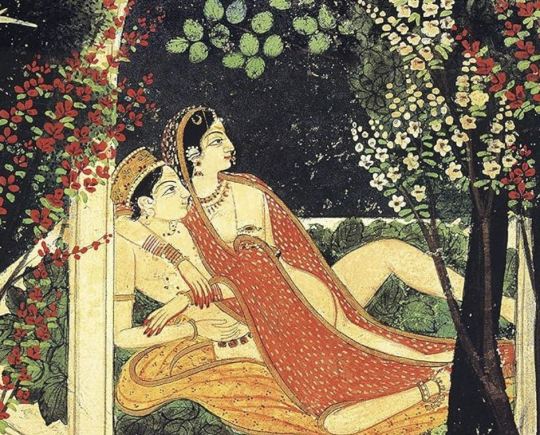

In India, the Kama Sutra, more than a manual of intimacy, delved into rituals and practices for fostering love and attraction. Ayurveda, India’s ancient medicinal system, recommended aphrodisiac herbs like ashwagandha and shatavari to enhance passion and deepen emotional connection.

Japanese folklore, on the other hand, speaks of "omamori" love talismans blessed at Shinto shrines. These were carried to invoke the protection and favor of kami (deities) for romantic endeavors.

Europe: Spells of Romance and Obsession

Europe’s history of love magic is a blend of folklore, mysticism, and religious undertones. In ancient Greece and Rome, love potions—often made from herbs like myrtle or rose—were crafted to awaken desire. Aphrodite (or Venus), the goddess of love, was frequently invoked in rituals, with offerings of doves or apples symbolizing beauty and fertility.

During the medieval and Renaissance periods, love magic often walked a fine line between fascination and persecution. The use of "philters" (love potions) and "poppets" (dolls) to influence romantic outcomes could lead to accusations of witchcraft. Yet, folk practices persisted. For instance, English cunning folk recommended carrying rose quartz to attract love, while French peasants relied on charms sewn into clothing to inspire fidelity.

Love Magic Today: A Universal Language

Despite its varied expressions, love magic is a universal thread linking humanity’s longing for connection. In modern times, these ancient traditions continue to inspire spiritual practices. From lighting candles on Valentine’s Day to crafting intention spells, the essence of love magic endures—reminding us that love is as much a spiritual endeavor as it is an emotional one.

This Valentine’s Day, whether you light a candle, gift a rose, or simply reflect on the magic of love, remember: across every culture and era, love has been a force worth invoking, celebrating, and cherishing.

Bibliography : Yoruba Religion and African Spiritual Practices: Drewal, H. J. (2009). Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. Hoodoo and Vodou Traditions: Anderson, J. L. (2008). Conjure in African American Society. Indigenous American Rituals: Johnston, B. (1976). Ojibway Ceremonies. Asian Love Magic: Needham, J. (1956). Science and Civilisation in China. European Folk Practices: Kieckhefer, R. (1997). Magic in the Middle Ages. Indigenous Traditions in Australia and Scandinavia: Pentikäinen, J. (1996). Shamanism and Culture. Andean Spiritual Practices: Bastien, J. W. (1985). Mountain of the Condor: Metaphor and Ritual in an Andean Ayllu.

#history of love magic#love magic#the love witch#aphrodite#hellenic polytheism#hellenic deities#hellenic worship#karma sutra#the lovers#valentines day#Oshun#african traditional religons#hoodoo#haitianvodou#erzulie freda#love spells#february 2025#witchblr#pagan community#venus#brujeria#witches of color#magic#history#indigenous#south america#folk magic#america#european#asia

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

💀Goddesses of death💀

Ereshkigal: Mesopotamian goddess of death, the dead, and the underworld.

Ereshkigal is the queen of the underworld, the keeper of balance, the punisher of evil & maintains order against chaos. She may have also been associated with the earth & the waters of life in Mesopotamian legend. She was associated with the city of Kutha and featured in the myth of Inanna's Descent to the Underworld. She was also connected to other deities such as Nergal, Ninazu, and Ningishzida. Ereshkigal was said to be the sister of Inanna.

Oya: African Goddess/orisha of death, storms, winds & thunder.

Oya is a powerful goddess/orisha in Nigeria who controls storms and death and is married to the thunder god, Shango. She is a shape-shifter who often appears as a mortal woman or animal while overseeing justice and bringing sudden change. She is also a guardian of women and the dead, able to call forth death or delay it. Oya is associated with rebirth and magic, and her favorite colors are maroon and copper.

The Keres: Greek goddesses of Death, bloodshed & violence.

The Keres were female death spirits and goddesses who personified violent death. They were drawn to bloody, intense deaths on battlefields and were daughters of Nyx, Goddess of Night. They did not have the power to kill but would wait and then feast on the dead. They were described as dark beings with gnashing teeth & claws, with a thirst for human blood. They would hover over the battlefield and search for dying/ wounded men.

The Morrigan: Irish Goddess of death, fate, war & sovereignty.

The Morrígan, also called the Phantom Queen, is a bewitching goddess associated with war and fate, often appearing as a crow, encouraging bravery and strength in battle, & foretells doom or victory. The Morrígan is often described as a trio of sisters, representing the goddess's role as a guardian and warrior. She can appear in many forms like an old woman, a crow, a beautiful sorceress, or a fearsome creature.

Mictecacihuatl: Aztec Goddess of death & the underworld.

Also known as the Lady of the Dead, Alongside Mictlantecuhtli, her consort, she rules over Mictlán, the lowest Aztec underworld realm. She guides the departed souls on their transformative journey from life to the afterlife and embodies the profound duality of existence. The Dia de los Muertos is a vibrant festival that allows families to honor deceased loved ones with ofrendas and calavera imagery, inspired by Mictecacihuatl, who is now called Santa La muerte.

Kali-ma: Hindu Goddess of destruction, death, change & time.

Kali-ma is the wrathful & protective force of Shakti (energy), She's a caring mother to her devotees/innocent people and the destroyer of evil, she expresses the dual nature of the destruction that must come before new beginnings. Kali ma embodies the power of all, transcending good & evil to protect her people against negativity. Kali ma is Mother Nature, primordial, nurturing, and devouring, She is vested in freeing beings, granting salvation.

Hel: Norse Goddess of death, the underworld & decay.

Hel, the half living and half dead goddess, is one of Loki's children, and rules over the realm of the dead, she mostly receives those who died of illness or old age in her realm. Hel is often depicted as a fearsome figure, and in Her realm, Helheim, is considered one of the nine worlds in Norse cosmology and is located in the lowest part of the universe. In the events of Ragnarok, Hel plays a crucial role. It is foretold that she will lead an army of the dead to fight against the gods.

Morana: Slavic Goddess of death, winter, magic & dreams.

Morana is a Slavic goddess associated with seasonal agrarian rites based on the idea of death and rebirth of nature. the death of Morana at the end of winter becomes the rebirth of Spring of the Goddess Vesna, representing the coming of Spring, joy & life. She is still worshipped to this day and is often described as a vengeful, powerful goddess. She is married to the spring/love God Yarilo but their relationship is not seen as healthy.

Izanami: Japanese Goddess of Death, darkness & creation.

Izanami is a Shintō creation mother goddess who became the Japanese goddess of death after she died while giving birth. Her name, Izanami, means ''the female who invites.''. She can create many lands and other divine beings, has the power of death and could command gods/spirits of the underworld. Izanami & Izanagi are the creators of the Japanese archipelago and the creators of the powerful deities Amaterasu, Tsukuyomi, and Susanoo.

#religion#religions#mesopotamian#mesopotamian mythology#african mythology#greek mythology#Hellenism#irish mythology#celtic mythology#aztec mythology#Hinduism#hindu mythology#indian mythology#norse mythology#slavic mythology#japanese mythology#Shinto#goddesses#Ereshkigal#oya#the keres#the morrigan#morrigan#Mictecacihuatl#Kali ma#hel#morana#Izanami#Shakti#lotus list

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

i've not read the children of blood & bone books, but as a nigerian diaspora kid, i'm still gonna poke my nose in & have an opinion. I'll just say that Tomi Adeyemi, a Nigerian-American woman who only connected w/ her Nigerian ancestry in her 20s, was never gonna have anything "less" than an black-diaspora-excellence adaptation. In an ideal world, a Nigerian production studio would've brought the story to life with Nigerian actors who could at least pronounce Orisha w/o getting tongue-tied. But Tomi Adeyemi has put out a book with incredible success and has gained a limited fame that puts her among Black American celebrities, who are the people that she rubs shoulders with. She wouldn't "settle" for her NYT Bestseller book being adapted by a small(er) Nigerian production company w/ limited reach beyond the African continent & diaspora, featuring Nigerian actors whose names likely mean nothing to her (has she heard of Richard Mofe Damijo? Funke Akindele? Ramsey Nouah? Genevieve Nnaji? has she even glimpsed any of their films?). Paramount Pictures have the reach, they have the money, they have the glamour that fits the kind of glossy black-excellence narrative that has built the book up (hers was really the first African-flavoured YA fantasy books to get any kind of popularity/push in a western market). Paramount have seemingly thrown all the hottest Black diaspora actors into the pot, w/ no attempt to even look anywhere else. And again, I think Adeyemi defends the casting because she's sincerely very happy with it - a prestigious cast as deserving of a NYT bestseller, by a woman who clearly and understandably enjoys her success (if her insta is anything to go off).

It's an American adaptation of an American book, by an American author whose engagement w/ her heritage was severely limited by design (which I don't judge her for, I'm not exactly miss naija myself). I think this outcome (all diaspora Actors) was kinda inevitable, but idk why the ppl in charge of this film ever decided to pretend that was going to NOT be the case, by doing that whole "open casting" song and dance. Like just be straight up, you're not going to cast anyone who isn't 100%, bulletproof bankable. Like wth is Amandla Stenberg doing here lollll, always at the scene of the crime, that girl.

I'm pleased people are upset though. Black Panther was tolerable, but this isn't a Wakanda situation - Orisha, indigenous religion practitioners, the ethnic group it emerged from are very real. That being said, I think if you want fantasy works that sincerely engage with African cosmologies, you can easily do much better than Adeyemi's book. Nigerian SFF literature is on the up and up - you can start with the Nigerian authors in the Africa Risen anthology, who have published great work everywhere. These authors' works are very accessible - they're published in various online magazines. My personal faves are Dare Segun Falowo and Pemi Aguda - Falowo's work reads like a heady, nauseous fever-dream, but Aguda is always controlled, she knows the perfect moment to twist the knife. Her anthology Ghostroots was one of the best things I read last year. Falowo's Ngozi Ugegbe Nwa is a terrifying riff on old stereotypes about women living the high-life in the big city. And Aguda's Manifest is a total encapsulation of her work, her ability to condense societal anxieties into just a few narrative beats. I could go on and on (Wole Talabi, Oluwatomiwa Ajeibe, Chinelo Onwualu etc). While I don't know if I believe in a singularly "authentic" Nigerian culture that can be codified and then represented, these authors are living (or have lived) & publishing straight from the continent in spite of everything, so check them out.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heaven, hell and the burning threat to Quilombola rituals

Drought, heat, and storms caused by global heating and the destruction of Nature have disrupted the half-moon religious traditions in communities in the Lower Amazon region

“While society is made up of equals, the community is made up of the diverse. We are the diverse—cosmological, natural, organic. […] We are all cosmos, except for humans. I’m not human, I’m a Quilombola [descendent of enslaved African rebels]. I’m a farmer, a fisher, a being of the cosmos.”

From the book A Terra Dá, a Terra Quer, by Brazilian writer and intellectual Antônio Bispo dos Santos (Nego Bispo)

When it storms in the community of Jocojó, 88-year-old Gabriel Soares da Conceição relives the terrifying night he spent between heaven and hell. He was coming back from fishing on the Jocojó, a coffee-colored river that leads to Gabriel’s community and lends it its name, when the downpour hit. He decided to take a shower in the rainwater streaming off the roof gutters. As he stretched out his cupped hand to catch some water to bless himself, he heard the boom—and was struck by lightning. “I could only say ‘Our Father’. Couldn’t get to ‘the Son’ or ‘Holy Ghost’. I fell down.” The electrical discharge left burns on his body and knocked him out for several minutes.

While Gabriel lay there unconscious, he says he was transported to hell, where he has a clear memory of being offered a plate of food. “I hadn’t eaten a bite till then,” he says. But the meal caught fire before he could taste it. Then he departed hell and was soon at heaven’s doors—but he didn’t make it through them. A messenger at the gates said he should be sent back: “It’s not his time yet.”

Gabriel survived but he’s never been the same. He takes comfort in the saints, although he finds himself shaking whenever “weather starts brewing” in Jocojó.

Nor has the weather in Jocojó ever been the same, something Gabriel knows full well. The climate is growing increasingly unpredictable and perplexing in the municipality of Gurupá, located in the Marajó Archipelago, in the Lower Amazon region, in Pará state. Old-timers know everything is different here now. Hotter. Rainier. Dry like never before. Gurupá encompasses 12 quilombo communities, originally founded by enslaved African rebels. Scattered across 83,000 hectares of titled land, they are home to 740 families.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#antiracism#environmentalism#religion#quilombos#image description in alt#mod nise da silveira

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supercomputer simulations of giant radio galaxy formation challenge current theoretical models

Enabled by supercomputing, University of Pretoria (UP) researchers have led an international team of astronomers that has provided deeper insight into the entire life cycle (birth, growth and death) of giant radio galaxies, which resemble "cosmic fountains"—jets of superheated gas that are ejected into near-empty space from their spinning supermassive black holes.

The findings of this breakthrough study were published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, and challenge known theoretical models by explaining how extragalactic cosmic fountains grow to cover such colossal distances, raising new questions about the mechanisms behind these vast cosmic structures.

The research team—which was led by astrophysicist Dr. Gourab Giri, who holds a postdoctoral fellowship from the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory at UP— consisted of Associate Professor Kshitij Thorat and Extraordinary Professor Roger Deane of UP's Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences; Prof Joydeep Bagchi of Christ University in India; Prof DJ Sailkia of the Inter-University Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, also in India; and Dr. Jacinta Delhaize of the University of Cape Town (UCT).

This study tackles a key question in modern astrophysics: how these structures, which are larger than galaxies and are made up of black hole jets, interact over cosmological timescales with their very thin, gaseous surroundings.

"We mimicked the flow of the jets of the fountains in the universe to observe how they propagate themselves over hundreds of millions of years—a process that is, of course, impossible to track directly in the real cosmos," Dr. Giri explains.

"These sophisticated simulations enable a clearer understanding of the likely life cycle of radio galaxies by revealing the differences between their smaller, early stages and giant, mature stages. Understanding the evolution of radio galaxies is vital for deepening our knowledge of the formation and development of the universe."

"While such studies are computationally expensive," Prof Thorat adds, "the team embarked on this adventure informed by the exciting, cutting-edge observations carried out by new-generation radio telescopes, such as the South African MeerKAT telescope, which has been instrumental in providing us with the details of the structure of these cosmic fountains."

Astronomers study galaxies for more than just the stars they can see, Dr. Giri says. "We also look at many, often interrelated, phenomena. One of the most amazing things to see is when a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, which is relatively tiny in size compared to the galaxies they grow in, 'wakes up' and starts eating up lots of nearby gas and dust. This isn't a calm, slow or passive process.

"As the black hole pulls in material, the material gets superheated and is ejected from the galaxy at near-light speeds, creating powerful jets that look like cosmic fountains. These fountains emit radio signals as the accelerated high-speed plasma matter generates radio waves. These signals are detected by very powerful radio telescopes, built through the collaborative efforts of multiple countries working together."

"With the recent advent of powerful and sensitive radio telescopes—such as MeerKAT in South Africa, the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) in Europe and the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT) in India—astronomers are now detecting these fountains even in their faintest stages," Dr. Giri adds.

"These advanced telescopes can capture the weakest signals from dying or fading parts of the jet, leading to new discoveries of more such extended sources that were previously undetectable."

The study also implies that these giant jets may be more common than previously thought.

Since the discovery of these high-speed fountains in the 1970s, astronomers have been curious about how far the ejected matter travels before eventually fading out. The answer was astounding as they began to discover that cosmic jets travel vast distances—some reaching nearly 16 million light-years (nearly six times the distance between the Milky Way and Andromeda).

"I took on the challenge of developing theoretical models for these sources, rigorously testing the models with the advanced capabilities of modern supercomputers," Dr. Giri says.

"This computer-driven study aimed to simulate the behavior of giant cosmic jets within a mock universe, constructed according to known physical laws governing the cosmos. Our primary focus was to answer two questions: Is the enormous size of these jets due to their exceptionally high speeds; or is it because they travel through regions of space that are nearly empty of surrounding matter, offering minimal resistance to the jets' free propagation?"

The UP-led study presents evidence that a combination of these considerations is a key aspect in the formation of these giant jets.

With the help of the supercomputing power of the Inter-University Institute for Data Astronomy (a collaborative network consisting of UP, UCT and the University of Western Cape), the international research team was able to analyze the vast quantities of simulated data, effectively spanning millions of years.

"These computer-based models, which simulate jet evolution in a mock universe, do more than explain the origin of most giant radio galaxies," Dr. Giri says.

"They're also powerful enough to address puzzling exceptions that have confused astronomers in this field. For example, they help explain how some cosmic fountains bend sharply, forming the shape of an X in radio waves instead of following a straight path, and clarify the conditions under which giant fountains can still grow in dense cosmic environments." These findings can be tested further by radio astronomers using advanced telescopes.

"Studies like this lead the way in formulating our understanding of these wonderful objects from a theoretical perspective," Prof Thorat adds. "This provides a complementary picture to deep-sky observations by telescopes like MeerKAT and the upcoming SKA, making simulations a key tool along with artificial intelligence techniques and high-performance computing to maximize the discovery space and optimize the scientific understanding of these and other 'exotic' objects."

Prof Sunil Maharaj, Vice-Principal for Research, Innovation and Postgraduate Education at UP, noted that the University is proud of the rapid growth of its radio astronomy research group.

"This was enabled by strategic investment in the Inter-University Institute for Data Astronomy and key personnel focused on science with world-leading African telescopes," he says.

"It's just one example of UP's leadership role in harnessing cutting-edge technology that increases Africa's contributions to pushing scientific frontiers while developing the next generation of researchers on the continent. The research we are doing today is opening up new worlds and possibilities for the future."

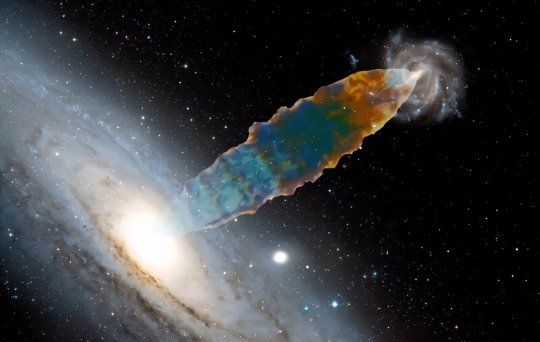

TOP IMAGE: An artistic representation of what a giant cosmic jet the size of the distance between the Milky Way and Andromeda could look like (image for illustrative purposes only). Credit: University of Pretoria

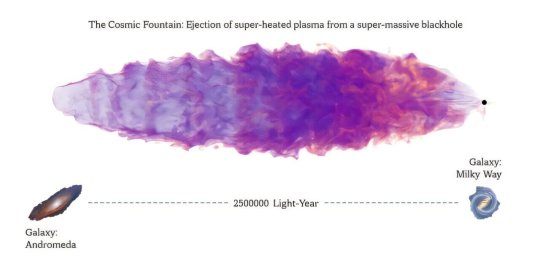

CENTRE IMAGE: Depiction of the scale of a cosmic fountain ejection. Credit: University of Pretoria

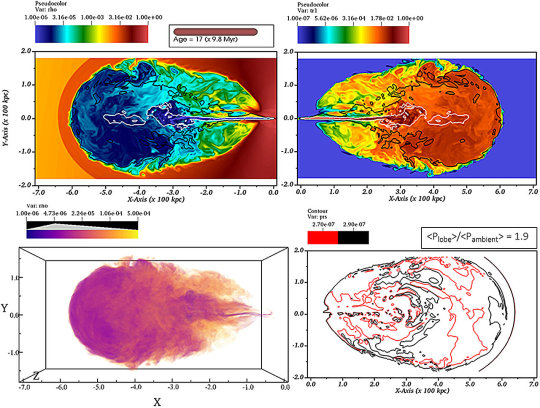

LOWER IMAGE: Simulation "GRG_lp_min" (low-powered jet propagating along the minor axis of the environment) showcasing the structure of the evolved GRG at the highlighted age. Top-left panel: x − y variation of (ρ/ρ0), accompanied by contours of velocity (0.1c for white, 0.01c for black). Credit: Astronomy & Astrophysics (2024). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202451812

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something i wrote in 2014, that i forgot about til just now......

"Observations from a pre-apocalyptic childhood.

Everywhere looks like a scene from a damn horror movie. Not the parts where all the blood and guts are spilled all over the place, but just the whole vibe where everything feels overly vivid and dark and surreal and it always feels like some bad shit is about to pop off. It always feels like night time, even when the sun is shining full throttle.

No matter how much light there is outside, everywhere seems drenched in cold overbearing shadows. Overly fascinating predators, hustlers, freaks and outcasts hidden in plain sight run the scene, adorned in costumes signifying either an allegiance to cocaine-fuelled disco decadence, willful genocidal complicity and collusion, bombed out fatalism, pending urban guerrilla warfare, or most commonly, stale self-righteous banality.

Everywhere is dirty, sketchy, dilapidated, yellow with piss and nicotine stains, dried blood on the sidewalk, grey and shadowy, with tinny disco sounds blaring from those prefab storefronts almost sinister in their innocuousness.

Some shit really stands out. A stencilled graffiti piece spraypainted in basic black on the side wall of a bank reads "Only The Rich Build Bombs."

A crackling tinny transistor radio stays tuned to a ghostly mysterious AM radio station, playing a strangely sweet sounding pop song that i later find out is about necrophilia.*

A creepy old baldheaded white man calls out to me from a sinister store front, "come here little boy! You wanna play a game?", licking his lips, while i run away to go tell my papa.

An elephant faced man with boils and burns covering all of his face and skin minds his own affairs and runs his errands, as everyone around him tries so hard not to stare.

A polyester-decked street corner preacher with a heavy Polish accent, cheap hairpiece on his head, bellows loudly about eternal hellfire and damnation, as stoned long haired teenagers in jean jackets excitedly take in the graphic descriptions of skin burning, eyes exploding and sexualized torture at the hands of sadistic demons til the end of time, before being to told to repent, at which point they begin flashing their pale ass cheeks and flipping their eager middle fingers.

Serious regal looking Black men with wide horizontal Afros, floppy leather caps, earth toned dashikis, army jackets and faded blue jeans supervise their tables selling books, oils and incense, flanked by red, black and green flags, arguing passionately about passages in the Bible used to justify slavery, tensions between Islam and Indigenous African cosmologies, reparations, repatriation, dirty money, clean hands and alibis.

Bombed out urban mutants looking like post-fallout zombies talk shit and get smashed drinking from bottles of cheap toxic liquid, hair dyed purple and green, hacked, shaved and spiked, monster makeup on their faces, adorned in spikes, chains, black leather, boots, torn up army regalia and shredded splatter bleached black denim, stenciled with words saying shit like "Hate & War", "Burned & Bombed", "Born To Die", "No God", "Sick Pleasure", "Crucifucks", "Millions of Dead Cops", "Subhumans" and "Peopleless Buildings", deriving great pleasure from playing with pet rats and engaging in playful self-abuse, as the horrified passerby gawk at them.

A group of middle aged Italian men in custom made silk suits play dominoes and blackgamma, smoking cigarillos and drinking cappucinos, making it damn clear as unmuddied rivers that this is grown man business and any women and children had better stay clear away.

Seedy movie houses with puke encrusted floors flash shiny marquees advertising the latest horror, smut and kung fu kick 'em up and fuck 'em up flicks, as a little boy with ringlet curls bouncing on his head wishes he could get in, afford to get in, or at least figure out which back exits are best for sneaking in.

At home, there are hushed, tense and passionate discussions en espanol, about torture, disappearances, massacres, military repression, death squads, cattle prods, rubber bullets, tear gas and water cannons.

Suitcases sit piled up at the ready, as two traumatized young parents do their best to make a safe haven inside a barren makeshift room, so that their little child can have some kinda clue about some kinda shit being some kinda safe, at least for some kinda time........"

* "There's No Blood In Bone", by the Poppy Family

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yoruba religion (Yoruba: Ìṣẹ̀ṣe), West African Orisa (Òrìṣà), or Isese (Ìṣẹ̀ṣe), comprises the traditional religious and spiritual concepts and practice of the Yoruba people. Its homeland is in present-day Southwestern Nigeria, which comprises the majority of Oyo, Ogun, Osun, Ondo, Ekiti, Kwara and Lagos States, as well as parts of Kogi state and the adjoining parts of Benin and Togo, commonly known as Yorubaland (Yoruba: Ilẹ̀ Káàárọ̀-Oòjíire).

It shares some parallels with the Vodun practiced by the neighboring Fon and Ewe peoples to the west and with the religion of the Edo people to the east. Yoruba religion is the basis for a number of religions in the New World, notably Santería, Umbanda, Trinidad Orisha, and Candomblé.[1] Yoruba religious beliefs are part of Itàn (history), the total complex of songs, histories, stories, and other cultural concepts which make up the Yoruba society.

The Yoruba name for the Yoruba indigenous religion is Ìṣẹ̀ṣẹ, which also refers to the traditions and rituals that encompass Yorùbá culture. The term comes from a contraction of the words: Ìṣẹ̀, meaning "source/root origin" and ìṣe, meaning "practice/tradition" coming together to mean "The original tradition"/"The tradition of antiquity" as many of the practices, beliefs, traditions, and observances of the Yoruba originate from the religious worship of Olodumare and the veneration of the Orisa.

According to Kola Abimbola, the Yorubas have evolved a robust cosmology. Nigerian Professor for Traditional African religions, Jacob K. Olupona, summarizes that central for the Yoruba religion, and which all beings possess, is known as "Ase", which is "the empowered word that must come to pass," the "life force" and "energy" that regulates all movement and activity in the universe".Every thought and action of each person or being in Aiyé (the physical realm) interact with the Supreme force, all other living things, including the Earth itself, as well as with Orun (the otherworld), in which gods, spirits and ancestors exist. The Yoruba religion can be described as a complex form of polytheism, with a Supreme but distant creator force, encompassing the whole universe.

The anthropologist Robert Voeks described Yoruba religion as being animistic, noting that it was "firmly attached to place".

Each person living on earth attempts to achieve perfection and find their destiny in Orun-Rere (the spiritual realm of those who do good and beneficial things).

One's ori-inu (spiritual consciousness in the physical realm) must grow in order to consummate union with one's "Iponri" (Ori Orun, spiritual self).

Iwapẹlẹ (or well-balanced) meditative recitation and sincere veneration is sufficient to strengthen the ori-inu of most people. Well-balanced people, it is believed, are able to make positive use of the simplest form of connection between their Ori and the omnipotent Olu-Orun: an Àwúre (petition or prayer) for divine support.

In the Yoruba belief system, Olodumare has ase over all that is. Hence, it is considered supreme.

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#afrakans#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#orisa#Ìṣẹ̀ṣẹ#Ori Orun#Ori#oyo#ogun#lagos#nigeria#nigerian#nigerians#vodun#yoruba religion#shango#oludamare#Olodumare#Candomblé#Trinidad Orisha#Yorubaland#Ilẹ̀ Káàárọ̀-Oòjíire#santería#umbanda

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

#cosmos#cosmology#africancosmology#African science#African technology#books#education#reading#study#thebookwormshideout

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

African American Baptism in De Leon Springs, FL. Circa 1915. Image via Florida Memory.

Seashells in Jomo

In West and West-Central African cosmology water is seen as a bridge between de material and spiritual world. In Jomo, the Kongo dikenga is a recurrent motif that is remembered and respected. This symbol illustrates the concept of water dividing the spiritual world and the material world; as the kalunga line divides the ancestral realm and the realm of creation.

Offerings:

Seashells were often given to ancestors as offerings. In Florida —and beyond— they were placed on the top of loved one’s graves. For one, to maintain a connection with them as they transitioned to another realm. Furthermore, to ensure those who passed on remained on the other side.

Protection/Talismans:

Consequently seashells were also worn as a means of protection against enemies. Ancestors and/or the deities they made covenants with, protected those who charmed seashells with that intent.

Candles:

Seashells could also be used to hold candlewax. These candles could be burned as offerings for the ancestors and/or specific deities.

5 notes

·

View notes