#adverbs of purpose in English grammar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Adverbs of Purpose in the English Language: A Complete Guide

Introduction In English grammar, adverbs of purpose play a crucial role in expressing the reason or purpose behind an action. They help us answer the question “Why?” by providing clarity and logical flow to our sentences. Whether you are writing an academic essay, having a conversation, or composing a business email, using adverbs of purpose correctly can enhance your communication skills. In…

#accent#adverbs of purpose activities#adverbs of purpose definition#adverbs of purpose examples#adverbs of purpose exercises#adverbs of purpose exercises with answers#adverbs of purpose for ESL students#adverbs of purpose in English grammar#adverbs of purpose lesson plan#adverbs of purpose list#adverbs of purpose multiple choice questions#adverbs of purpose online exercises#adverbs of purpose pdf#adverbs of purpose practice#adverbs of purpose quiz#adverbs of purpose sentences#adverbs of purpose test#adverbs of purpose usage#adverbs of purpose worksheet#american english#british english#daily prompt#English#English learning#examples of adverbs of purpose in sentences#grammar#how to use adverbs of purpose#IELTS#Japanese language learning#language

1 note

·

View note

Text

actual writing advice

1. Use the passive voice.

What? What are you talking about, “don’t use the passive voice”? Are you feeling okay? Who told you that? Come on, let’s you and me go to their house and beat them with golf clubs. It’s just grammar. English is full of grammar: you should go ahead and use all of it whenever you want, on account of English is the language you’re writing in.

2. Use adverbs.

Now hang on. What are you even saying to me? Don’t use adverbs? My guy, that is an entire part of speech. That’s, like—that’s gotta be at least 20% of the dictionary. I don’t know who told you not to use adverbs, but you should definitely throw them into the Columbia river.

3. There’s no such thing as “filler”.

Buddy, “filler” is what we called the episodes of Dragon Ball Z where Goku wasn’t blasting Frieza because the anime was in production before Akira Toriyama had written the part where Goku blasts Frieza. Outside of this extremely specific context, “filler” does not exist. Just because a scene wouldn’t make it into the Wikipedia synopsis of your story’s plot doesn’t mean it isn’t important to your story. This is why “plot” and “story” are different words!

4. okay, now that I’ve snared you in my trap—and I know you don’t want to hear this—but orthography actually does kind of matter

First of all, a lot of what you think of as “grammar” is actually orthography. Should I put a comma here? How do I spell this word in this context? These are questions of orthography (which is a fancy Greek word meaning “correct-writing”). In fact, most of the “grammar questions” you’ll see posted online pertain to orthography; this number probably doubles in spaces for writers specifically.

If you’re a native speaker of English, your grammar is probably flawless and unremarkable for the purposes of writing prose. Instead, orthography refers to the set rules governing spelling, punctuation, and whitespace. There are a few things you should know about orthography:

English has no single orthography. You already know spelling and punctuation differ from country to country, but did you know it can even differ from publisher to publisher? Some newspapers will set parenthetical statements apart with em dashes—like this, with no spaces—while others will use slightly shorter dashes – like this, with spaces – to name just one example.

Orthography is boring, and nobody cares about it or knows what it is. For most readers, orthography is “invisible”. Readers pay attention to the words on a page, not the paper itself; in much the same way, readers pay attention to the meaning of a text and not the orthography, which exists only to convey that meaning.

That doesn’t mean it’s not important. Actually, that means it’s of the utmost importance. Because orthography can only be invisible if it meets the reader’s expectations.

You need to learn how to format dialogue into paragraphs. You need to learn when to end a quote with a comma versus a period. You need to learn how to use apostrophes, colons and semicolons. You need to learn these things not so you can win meaningless brownie points from your English teacher for having “Good Grammar”, but so that your prose looks like other prose the reader has consumed.

If you printed a novel on purple paper, you’d have the reader wondering: why purple? Then they’d be focusing on the paper and not the words on it. And you probably don’t want that! So it goes with orthography: whenever you deviate from standard practices, you force the reader to work out in their head whether that deviation was intentional or a mistake. Too much of that can destroy the flow of reading and prevent the reader from getting immersed.

You may chafe at this idea. You may think these “rules” are confusing and arbitrary. You’re correct to think that. They’re made the fuck up! What matters is that they were made the fuck up collaboratively, by thousands of writers over hundreds of years. Whether you like it or not, you are part of that collaboration: you’re not the first person to write prose, and you can’t expect yours to be the first prose your readers have ever read.

That doesn’t mean “never break the rules”, mind you. Once you’ve gotten comfortable with English orthography, then you are free to break it as you please. Knowing what’s expected gives you the power to do unexpected things on purpose. And that’s the really cool shit.

5. You’re allowed to say the boobs were big if the story is about how big the boobs were

Nobody is saying this. Only I am brave enough to say it.

Well, bye!

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

can you explain what's a split infinitive?

Ehhh. I'm not a linguist, anon, I'm just a guy who writes with limited respect for prescriptive grammar that serves no purpose. There are a bunch of different verb forms to be categorised in linguistics and if you want to know about them you can look them up on Wikipedia or ask a linguist. ( @roadkill2580 is that you? )

Short version: an infinitive is a non-finite verb, as opposed to (you guessed it) a finite verb. Most verbs in English can be written in finite OR non-finite form, and occasionally those are identical. In English we often write these like, for example, "to see." If you cram something between "to" and "see" you have split it. So "to properly see if that was true," is putting an adverb in the middle of a verb form, splitting it. In theory it would therefore be, "to see properly if that was true."

The most oft-derided split infinitive of the 20th century was probably "to boldly go where no man has gone before," ala OG Star Trek, and is probably the only place where most people who are from the 1980s or younger will have encountered this incredibly stuffy grammatical complaint, I think. (The "corrected" version would have been, "to go boldly where no man has gone before.")

Personally I would not bother to worry about split infinitives when I could worry about learning to apostrophise or not switching tense mid sentence or other grammatical conventions that are actually useful in English. Same with ending a sentence on a preposition, really. Who even are we?

If we're gonna be real, most native English speakers learnt the rules to English by vibes only and in basically whatever dialect we fetched up beside. Some settings require specific writing competencies (like professional emails or published stories, etc) but in my experience absolutely none of them require you to worry about split infinitives in 2024.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disco didn’t die. it was murdered!

Psych is one of the best at doing these themed episodes. They change the camera work, the lighting, the background theme, and even the outfits. Like, they go all out and its always fun :)

Look at this smug bastard. I don’t mind arrogance, but i do mind the fake modesty. It made me roll my eyes haha

Now to settle my own curiosity, i looked into all the things shawn and gus point out about the chiefs phrases and grammar.

“I could care less” and “i couldn’t care less” are used interchangeably though english scholars will say the latter is the correct phrase and should be used formally.

“Goes without saying” was originally a french term ça va sans dire and my understanding of it is that it meant more like “absolutely” or “of course” where the English equivalent is more like “obviously”. Either way we can blame the french for this one haha

The chief did in fact split an infinitive when she said “why don’t you tell me how to properly say this-“ Splitting an infinitive is when you put an adverb between to- and a verb. Such as to boldly go, to casually walk, or to gently push. Whether or not its proper english is debated i believe. But if you ask me, it wouldn’t sound right to have Kirk say to go boldly. Just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Heres a Phil collins/ corbin bersen side by side

Also, obviously the chief never should have put shawn on the case. Not only because henry is his dad, but also because he’s a “psychic” and i would think if they were trying to get a solid legal case against him, they wouldn’t use mr.woowoo. But again, its a cable show so we ignore this haha (but also no way they won that in court?? It was circumstantial at best)

“It was the 70’s, we did what we had to do but only when we knew we had the right guy.” Henry…is kind of a hypocrite? Like hes all about following the rules and especially the law but also thinks it was okay for him to do it because he had a good reason. Okay, maybe to give him a little more credit than that, the fact that hes so nervous and touchy about it (fiddling with the key, shouting at gus) is because he knew the search warrant was bogus and screwed up, but his pride prevents him from owning it outright. So, i like that it ends with Henry thanking Shawn for essentially fixing his mistake. I’ve been kinda iffy on henry this whole rewatch so far, and how he is with shawn aside, i at least know its more important for him to get the right guy (or at least be right) than it is to get a bust for the sake of his ego. Though, now that i think about it, thats really the bare minimum to be a cop so…

Ive said it before, but i like that the difference between shawns tactics and his fathers in getting information from people is that henry will bust through or even intimidate, while Shawn makes them feel good about themselves and in some cases like theyre a part of the team. There’s an argument that shawns way is more manipulative, and i think if we didn’t know him as a person it might come across that way, but instead it comes across as him just making friends with everyone he meets.

Gus thinking his story ends with a wrongful conviction explains him freaking out so much in season 7’s ep Office Space. Theres also a commentary there about this being a genuine fear in the black community which makes me very sad at the state of my country.

NATIONAL TREASURE IS A NATIONAL TREASURE GUS

Now, about shawn spending all their money on the car- i am of the belief that he did it on purpose either to be a stinker or to make it more challenging, or maybe I’m in denial that negotiating is not in his skill set considering he’s ridiculously good at so many other things haha

I just wanted to put their clue spotting side by side because i like that their similar and different at the same time :)

Incidentally my filipino coworkers reacted the same way when i told them my mom called my pookie, to which they explained (after laughing) that a “puki” was ahem, vagina in tagalog. Language is fun :)

This is going to sound weird but this is the first ep that juliet and lassie felt like actual partners. It just feels like their on the same level finally, and that level being a dick to mcnab for no reason haha. But im glad karma hit back real quick for them (also, their treatment from the coast guard was a preview for the next ep, though i would think they’d have met chief vicks sis in the process)

Who cuts a cucumber like this? Its one of the easiest vegetables to cut. I dont know why this bothers me so much haha

I could hash out the henry and shawn argument, but as Gus pointed out, they have this same argument pretty frequently. So i think, yeah, im just going to store it for later.

Okay, correction from my post on Daredevils!, this was the dumbest thing he ever did. He risked so many peoples lives like wtf?? And i was about to say shawn wouldn’t do that unless he had a trick up his sleeve because he did know how to turn it on, but then when no one is looking he is genuinely relieved it worked so he really didn’t think it through and im so disappointed in him. Bad psychic.

P.S

Dulé!

#i guess i technically can put rudimentary bomb knowledge on shawns list of skills??#they got jere burns which is neat#psych#psych rewatch#psych tv#shawn and gus#shawn spencer#burton guster#forgive me for the format of this one my own adhd left my thoughts scattered haha

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello! i'm new to your blog, and im honestly in love w/ all your yanderes, especially mykolas :)

if its okay with you, could i request some headcannons of how mykolas acts and looks, like what kind of traits he has?

💕💕

im so sorry this took for fucking ever for me to get to nonnie 😫 ik youre not new to my blog anymore but welcome!!! here's some hcs on the forest puppy for you

🌲 the beast • mykolas

· mykolas isn't any specific creature. he's kind of just his own thing with no real origin. he’s incredibly tall (over 8 feet with the antlers), bipedal digitigrade, glowing white eyes and a skull-like face, he definitely doesn't look like anything naturally occuring in nature either. some believe he's the offspring of a devil worshipper who was abandoned in the woods, others think he's some sort of werebeast who can't transform back into a human. mykolas himself has no clue either, and mostly responds with non-answers if you ask him about it.

· behavior wise? he honestly acts like a mix of domestic animals. he purrs like a cat, whines like a dog, throws little stompy tantrums like a bunny, all while being built like a tank lmfao. additionally, he’s VERY territorial after meeting you and will pick a fight with anything and anyone that invades the space he deems your home.

· before you, he wasn't really.. living. he just kind of existed, moving through each day without a sense of purpose. your existence grounds him and makes him feel alive, and that's why hes so obsessed with being by your side. he loves nothing more than cuddling you for hours on end, and being away from you gives him anxiety

· he DOES speak, but his english is pretty busted and his voice is rough from hardly being used. pronouns, adverbs, and adjectives are rare to hear from him and his grasp on grammar isn't the best. he doesn't mind if you teach him but he does get self conscious about it if you bring it up to him.

· he’s carnivorous, but he mostly eats fish because he doesn’t like the mess that hunting makes. trespassers are an exception to this.

· outside of the above, none of the tales that the people he lives near spun about him are true. he’s not a bloodthirsty beast, nor is he evil. he’s just lonely, and he’s not capable of fixing that on his own

#🌲 mykolas ;; the monster#anonymous#dating him is honestly kinda like dating a big pet with crazy separation anxiety#yandere x reader#yandere x you#yandere x oc#yandere headcanons#yandere oc#yandere terato#yandere teratophilia#xvi ;; the tower — asks/inbox

150 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you get this, answer w/ three random facts about yourself and send it the last five blogs in your notifs. Anon or not, doesn’t matter, let’s get to know the person behind the blog <3

As this uses the word “random,” I will try to be random, accordingly.

I currently have four instruments in my house: a piano, one plastic recorder, and decorative, dusty flamenco castanets and a replica bagpipe (gaita) on the wall. (Also, a strange thing I'm willing to bet people will find random: there is a miniature model hórreo (type of granary) in our dining room. It only takes up a bureau surface in a corner, but even if it did take up a lot of space, it wouldn't matter much because our dining table is covered in stacks of paperwork, so we can't actually eat there, unless we cleared it off for guests, haha.)

Rosemary Wells’ picture books were some of my favorites as a kid.

“Speech" incoming.

I had an interesting conversation yesterday that reminded me of something I think about every so often—I absolutely love the Hold Someone to Their Exact Words Exploitive Loophole as a trope and am a bit of a grammar enthusiast. However, I would never go into law. (And I understand having varying dialects and cultural differences. I think some people irl, even those with mostly standard "correct" speech, are just bored by grammatical/structural/rhetorical features, so I don't get to talk about them often.)

Fun fact: if you remove certain modal verbs from your speech and use declarative statements, you may automatically sound more confident in what you’re talking about. I don’t know if you can bluff with this trick/tip, but maybe someone out there will find it useful.

Second fun fact: To anyone, not even just English language learners, the native speakers I've observed lately often don't use the subjunctive (the hypothetical tense) or the right forms of adverbs when they should. It's surprisingly common, using phrasing like "was" instead of "were” in if-then statements. That said, maybe some people don't know or go for authenticity in oral speech over "correctness." And ultimately, there's nothing wrong with that. Breaking the rules for expressive or artistic purposes is fine!

However, I do have an example that bothers me because I haven't found a way around it. It's when people say: [omitted: "Get it done] quick!"

"Quick" used as a second person command works so well because it has a hard, monosyllabic impact, but it's wrong. If I'm not mistaken, "Quickly" would be the correct form. Why can't I be dramatic and correct at the same time, language?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clause (n): a unit of grammatical organization next below the sentence in rank and in traditional grammar said to consist of a subject and predicate. — New Oxford American Dictionary

Search the internet for “run-on sentences” and you’ll likely find examples of long lines (some run-ons, some not) by William Faulkner, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, and other authors famous for their verbosity. Some sites (which will go unnamed) tell you that one of the iconic lines of twentieth-century American literature—the first line of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951)—is a run-on sentence.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

This is, indeed, a long sentence—63 words and six commas, to be exact—but it is not a run-on. On the other hand, this sentence is:

Julia likes cats, however, she prefers dogs.

Just seven words and two commas, but a run-on. (By the way, that last line is a fragment, a sentence lacking even one independent clause.)

How is the second sample sentence a run-on if the first is not?

The answer hinges on the definition of a run-on sentence. Contrary to popular belief, run-on sentences are not defined by length or complexity; a 1,000-word sentence could be grammatically correct and a four-word sentence could be a run-on.

A run-on sentence is something far more precise. It’s a sentence that contains two or more independent (aka main) clauses not properly separated. Generally speaking, independent clauses can be separated by a period, a semicolon, a colon, a comma and a conjunction, or a dash (though not all of these solutions work for all sentences).

We might fix the run-on above to read:

Julia likes cats. However, she prefers dogs.

or, more commonly:

Julia likes cats; however, she prefers dogs.

or even better:

Julia likes cats, but she prefers dogs.

The reason why the original “Julia” sentence is a run-on is fairly arcane: a conjunctive adverb like “however” cannot separate two independent clauses. Students preparing for the SAT and ACT should learn how to identify independent clauses, dependent clauses, relative clauses, relative pronouns, conjunctions, subordinators (words that make clauses dependent), and conjunctive adverbs—all terms and ideas that need to be understood in order to master the art of avoiding and fixing run-ons and fragments. This is likely the most important cluster of grammatical issues to master for both tests.

But my purpose here is not to unpack the nuances of these issues (you’ll need to take a class for that). It is simply to note that preparing for the SAT and ACT requires that students begin to see conventional English sentences as things constructed along pretty exacting guidelines. Sentences, like machines, are objects made out of properly connected parts.

Like an automobile, a sentence is made of interlocking units. Just as there are many correct and incorrect ways to build a car, there are countless ways for the parts of a sentence to interlock correctly or not. And just as a good auto-mechanic sees a car for its parts and knows exactly what to do under the hood to fix a mechanical problem, SAT and ACT test-takers need to be able to see sentences as constructed things made of clauses, which need to be connected with the right tools and in the right ways.

This is precisely the kind of thinking at work in Salinger’s opening sentence in The Catcher in the Rye. The sentence is something of a master class in English grammar.

If you really want to hear about it, | the first thing | you’ll probably want to know | is | where I was born, | and what my lousy childhood was like, | and how my parents were occupied and all | before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, | but I don’t feel like going into it, | if you want to know the truth.

This sentence contains nine clauses total, 7 dependent and 2 independent, all properly separated. A clause consists of, at minimum, a subject and a predicate. I have highlighted only those terms necessary to complete each subject and predicate and italicized all conjunctions used to connect clauses. Things get tricky at the beginning of the second clause, whose subject is “thing” and whose verb is “is,” followed by an entire dependent clause (“where I was born”) that acts as the object of the verb “is.” In this sentence, “you’ll probably want to know” acts as a dependent clause since it is contained within a larger independent clause.

As a whole, a good SAT or ACT grammarian should see this sentence like this:

Dependent clause 1, Independent clause 1 Dependent clause 2 Independent Clause 1 continued Dependent clause 3, and Dependent clause 4, and Dependent clause 5, Dependent clause 6, but Independent clause 2, Dependent clause 7.

We could dig into this complex sentence further by looking at, say, how Salinger subordinates those seven dependent clauses, or by considering how to identify when a clause begins and ends. But, again, the point here is not to explore all these complexities (though that’s an important task for those preparing for the SAT and ACT).

My point is at once much simpler and more challenging: it is to show you that sentences are made of smaller units called clauses, and that there are rules for connecting and separating these units from each other. This is all to say that improving one’s grammar isn’t about memorizing countless rules or running your eyes over countless pages of writing.

It’s first and foremost about changing the way you see sentences—as constructed machines made of individual parts rather than as finished wholes.

#grammar#run-on sentences#English#English class#learning English#writing#writing class#SAT#ACT#test prep

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 Corinthians 9:15–16

15 ἐγὼ δὲ οὐ κέχρημαι οὐδενὶ τούτων. οὐκ ἔγραψα δὲ ταῦτα, ἵνα οὕτως γένηται ἐν ἐμοί· καλὸν γάρ μοι μᾶλλον ἀποθανεῖν ἤ—τὸ καύχημά μου οὐδεὶς κενώσει. 16 ἐὰν γὰρ εὐαγγελίζωμαι, οὐκ ἔστιν μοι καύχημα· ἀνάγκη γάρ μοι ἐπίκειται· οὐα��� γάρ μοί ἐστιν ἐὰν μὴ εὐαγγελίσωμαι.

My translation:

15 But I have made no use of any of these things. And I wrote these things not in order that it might be thusly in me; for to die is good rather than anyone will empty my boasting. 16 For if I preach good news, it is not boasting for me; for necessity is laid upon me; for it is woe to me if I do not preach good news.

Notes:

9:15

δὲ is adversative.

ἐγὼ is the emphatic subject of the negated perfect οὐ κέχρημαι (from χράομαι “make use of, employ”; see note on 7:21). The use of the verb here resumes its use in verse 12a, suggesting that the interim is an argument that suddenly suggested itself to the apostle’s mind. But, as opposed to the aorist-tense in verse 12 which referred to his prior actions in Corinth, the perfect-tense here denotes his continuing resolve. οὐδενὶ (“nothing, none”) is the dative direct object of the verb. τούτων is partitive, referring to the rights of an apostle for which Paul is arguing (“I have made use of none of these”; most translations: “I have not used/I have used none”; ICC: “I have not availed myself”).

δὲ is adversative (most translations: “But”; ICC: “yet, however”).

The direct object of the negated aorist οὐκ ἔγραψα (from γράφω) is the substantival near-demonstrative pronoun ταῦτα, referring to his arguments in support of rights for ministers of the gospel. The aorist is epistolary (“I am not writing this ...”).

ἵνα + subjunctive indicates purpose with γράφω above.

The adverb οὕτως (“thus, so”) modifies the aorist subjunctive γένηται (from γίνομαι), whose unexpressed subject is material support; “I am not writing these things so that it will be done so in my case” (NASB), i.e., ‘I didn’t want support then and I’m not asking for it now.’ The prepositional phrase ἐν ἐμοί here means, “in my case” (ICC, NIGTC, Fee).

Verses 15b – 17a feature five sentences beginning with γάρ, ‘each explaining or or elaborating the former’ (Fee). Few translations preserve all five, which would be cumbersome English.

The positive adjective καλὸν (“good”), before ἤ (“than”) below, stands in for the comparative “better”. μοι is a dative of advantage (“better for me”). μᾶλλον before ἤ is “rather”. The 2nd aorist infinitive ἀποθανεῖν (from ἀποθνῄσκω) functions as the subject of an implied ἐστιν, with which the nominative neuter καλὸν is predicate (lit. “To die is better ...” = “It is better to die ...”). Fee suggests the idea is not so much, “It is better for me if I die than ...”, but rather “It is better (for the sake of the gospel) that I die than ...” However, in that case, we would have expected an accusative subject for the infinitive, με, rather than the dative μοι.

The particle ἤ (“than”) marks a comparison.

τὸ καύχημά (“boasting”; see note on 5:6), modified by subjective genitive μου, is the direct object of the future κενώσει (from κενόω “I empty”; see note on 1:17; most translations: “deprive me”) whose subject is οὐδεὶς. καύχημά can mean “grounds for boasting” or the boasting itself; Fee argues for the latter, contra NRSV, ESV, NET, since ‘Paul’’s boast is in the act itself, not in its justification.’ After ἤ above, the UBS5 marks the abrupt change in grammar with a long dash (—), since the infinitive before ἤ is not mirrored by an infinitive after. The literal construction is, “To die is good (read: better) rather than— no one will empty/nullify my boasting.” The break in thought goes to show ‘Paul’s intense emotion’ over this issue (Fee). Some commentators supply an apodosis for the comparison (e.g., “It is better to die than give up my practice— no one will deprive me of my boasting”). Instead of οὐδεὶς some manuscripts read ἵνα τις, likely an emendation to clean up Paul’s grammar. This results in, “It is better to die than that anyone deprive me of my boasting.” In translation, this option is better than supplying an apodosis for the comparison, and most translations follow this tack.

9:16

The first instance of γὰρ in this verse is more explanatory than causal, explaining the final clause in verse 15.

ἐὰν + the present subjunctive εὐαγγελίζωμαι (from εὐαγγελίζω) forms the protasis of a third-class conditional statement which the speaker sees as possible. This verb is usually found in the middle-voice.

In the apodosis of the condition, the predicate nominative of the negated present οὐκ ἔστιν (from εἰμί) is καύχημα (“boasting, a cause for boasting”; see note on 5:6). The unexpressed subject of the verb is Paul’s preaching. μοι is a dative of interest (“for me”). NET: “I have no reason for boasting”.

The second instance of γάρ introduces an explanation for why Paul has no cause for boasting (“since/because”, most translations).

ἐπίκειμαι (7x), from ἐπί + κεῖμαι “I lie”, is literally, “I lie upon”; figuratively, “I confront, impose”. The subject of the present ἐπίκειται is is ἀνάγκη (“pressure, necessity”; see note on 7:26). The verb could be middle (“lies upon”, so ICC, NIGTC) or passive (“is laid upon”, NRSV). After the ἐπί-prefixed verb, the dative μοι is locative (“necessity lies/is laid upon me”). HCSB: “an obligation is placed on me”; NASB: “I am under compulsion”; NIV: “I am compelled to preach” (sim. NET); NIGTC: “God’s compulsion presses upon me”.

The third instance of γάρ elaborates the second, so that both together offer the explanation (Fee), omitted in most translations.

οὐαὶ functions as the subject of the present ἐστιν (from εἰμί), with μοί as a dative of interest/disadvantage. Most translations omit ἐστιν: “Woe to me”. NIGTC says that ‘οὐαί denotes ... with ἐστιν (as here), “misfortune, trouble” or “agony for me”’. So also ICC (“it will be the worse for me) and ZG (“It would be misery”). Fee, on the other hand, says that οὐαὶ does not signal inner distress but ‘divine judgment’ (italics original). The phrase constitutes an apodosis to the condition whose protasis is below.

ἐὰν + the negated aorist subjunctive μὴ εὐαγγελίσωμαι (from εὐαγγελίζω) forms the protasis of a third-class condition. The present-tense of εὐαγγελίζωμαι above describes preaching in general, whereas the aorist here imagines any single act of failing to preach.

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Different Types of Laam in Arabic Grammar

When diving into Arabic grammar, you'll come across a concept called "Laam" (لام), a letter that holds an important place in the language. Laam is one of the most commonly used letters in Arabic, and its role extends beyond being just a simple sound in words. It appears in different forms, each with its own grammatical purpose. In this article, we'll explore the different types of Laam in Arabic grammar and how they function within the language.

Types of Laam in Arabic grammar are essential to understand for anyone looking to get a deeper grasp of how Arabic sentences are constructed. Depending on where the Laam appears in a word or sentence, it can carry a range of meanings and serve various functions. Let’s go through the different types in detail.

1. Laam of the Definite Article (اللام التعريف)

The first and most straightforward type of Laam is the one that appears in the definite article "Al" (ال). This is the most common Laam, and it plays a crucial role in indicating that a noun is definite or specific. For example, in the phrase "الكتاب" (Al-Kitab), "Al" is the definite article, and the Laam is a part of it. This Laam does not carry its own meaning but is a necessary part of forming the definite noun.

The Laam in this context has no specific meaning on its own but rather acts as a grammatical tool that tells us the noun is specific, as opposed to indefinite.

2. Laam of Emphasis (لام التأكيد)

Another important type of Laam in Arabic grammar is the Laam of emphasis. It is used to add emphasis or certainty to a statement. This Laam typically appears in sentences where the speaker wants to stress something strongly.

For example, in the sentence "لَا أَحَدَ غَيْرُكَ" (La Ahada Ghayruka), the Laam here is used for emphasis, emphasizing the subject of the sentence. This usage reinforces the idea that there is no one else like you.

The Laam of emphasis can appear before verbs, nouns, or even adjectives. Its role is to create a stronger, more emphatic tone in the sentence.

3. Laam of Possession (لام الملكية)

The Laam of possession is a specific type of Laam that is used to indicate ownership. It is often used with pronouns to show possession. This Laam typically appears in phrases such as "لِي" (Li), which translates to "mine" in English. For example, the phrase "لِي مَنْزِلٌ" (Li Manzilun) means "I have a house."

This type of Laam is particularly useful when expressing ownership or possession, making it an essential part of possessive constructions in Arabic.

4. Laam of Purpose (لام الغرض)

The Laam of purpose is used to indicate the reason or purpose behind an action. This Laam introduces a goal or an intention behind a verb or action. For example, in the sentence "جئتُ لِأَتَعَلَّمَ" (Jit-u Li-At’allama), which means "I came to learn," the Laam is used to show that the purpose of the action is learning.

This type of Laam can also be used in phrases indicating purpose, such as "لِأَجل" (Li-ajl), meaning "for the sake of."

5. Laam of Exaggeration (لام المبالغة)

The Laam of exaggeration is used to create a sense of extremity or exaggeration. It often appears in words that express something to an intense degree, especially in adjectives or adverbs. For example, "لَعِبَ" (La’iba) means “to play,” but in exaggerated form, it can indicate an extreme sense of playing, sometimes implying an excessive action.

This Laam adds color and depth to the sentence, turning regular statements into more expressive ones.

Conclusion

In Arabic, types of Laam in Arabic grammar serve a variety of important functions, from defining nouns and expressing possession to emphasizing points and illustrating purpose. Understanding these different types can significantly enhance your grasp of Arabic grammar, allowing you to build more complex and nuanced sentences. Whether you're a beginner or an advanced learner, paying attention to the use of Laam will help you appreciate the subtleties and richness of the Arabic language.

By grasping these types of Laam, you’ll be able to not only understand Arabic grammar more deeply but also use the language more effectively and naturally.

0 notes

Text

#adverbs of reason#uses of adverb of purpose#examples of adverbs of reason#express reason#word which express purpose

1 note

·

View note

Text

IELTS Preparation: Understanding Your Weak Areas

Preparing for the IELTS can feel like navigating a maze, especially when you’re not sure where your weaknesses lie. Many test-takers find themselves overwhelmed by various sections of the exam, from writing to listening. The key to success is understanding these weak areas and turning them into strengths. Whether you’re struggling with vocabulary in the reading section or feeling anxious about speaking, pinpointing these challenges can make all the difference. Let’s dive deep into each component of the IELTS and uncover strategies that will boost your confidence and performance on test day. Get ready to transform your preparation journey!

Read More Infor — Best IELTS Coaching In Delhi

IELTS Writing: Too many words!

When it comes to IELTS writing, clarity is your best friend. Many candidates fall into the trap of using too many words to express their ideas. This can muddle your message and make it hard for the examiner to follow.

Conciseness should be a priority. Aim to convey your thoughts in a clear and direct manner. Instead of fluffing up your sentences with unnecessary adjectives or adverbs, focus on strong verbs and precise nouns.

Practice is essential here. Take sample prompts and challenge yourself to write within word limits without sacrificing quality. Review what you’ve written critically; ask if each word serves a purpose.

Remember, effective communication is about quality, not quantity. The goal isn’t just passing but showcasing your ability to articulate complex ideas succinctly.

IELTS Reading: Retaking the test

Retaking the IELTS Reading test can feel daunting, but it’s a chance for improvement. Many candidates don’t achieve their desired score on the first attempt. That’s okay; it happens to more people than you think.

Analyzing your previous performance is vital. Did you struggle with time management? Were certain question types particularly tricky? Understanding these aspects will guide your study plan.

Practice makes perfect. Utilize official practice materials and focus on reading extensively in English daily. This not only improves comprehension skills but also builds speed — a crucial factor during the exam.

Consider joining a study group or seeking professional guidance if you’re feeling stuck. Sharing strategies and insights can illuminate new approaches that you hadn’t considered before.

Stay positive and motivated as you prepare for round two of the test. Each effort brings you closer to achieving your goals, so embrace this opportunity for growth!

IELTS Listening: The importance of synonyms

When preparing for the IELTS Listening section, grasping synonyms is crucial. The test often uses varied vocabulary to convey the same idea. If you only focus on exact phrases, you might miss key information.

For instance, if a speaker says “happy,” they could also use words like “joyful” or “content.” Recognizing these alternatives can significantly impact your score.

Practice by listening to different English speakers in various contexts. Podcasts and news broadcasts are great resources. They expose you to diverse ways of expressing similar concepts.

Additionally, when reviewing practice tests, pay attention to how questions rephrase statements from audio clips. This will sharpen your listening skills and prepare you for unexpected vocabulary during the exam.

Building a strong synonym bank enriches your understanding and boosts confidence as you tackle this challenging component of the IELTS test.

IELTS Speaking: What is the examiner looking for?

When you sit down for the IELTS Speaking test, it’s crucial to understand what examiners are really assessing. They aren’t just listening for perfect grammar or an extensive vocabulary.

Examiners look for fluency and coherence in your responses. This means speaking naturally and connecting your ideas logically. It’s about how well you can maintain a conversation rather than reciting memorized answers.

Pronunciation is another vital aspect. Clear enunciation makes it easier for the examiner to understand you, even if your accent differs from theirs.

Additionally, they assess lexical resource — your ability to use a variety of words appropriately. Don’t hesitate to showcase synonyms or idiomatic expressions; this demonstrates linguistic flexibility.

Be authentic in your responses. Share personal experiences and opinions confidently; this adds depth to your answers and engages the examiner more effectively.

IELTS Preparation: Stress management

Preparing for the IELTS can feel overwhelming. The pressure to achieve a high score often leads to stress. Managing this stress is crucial for success.

Start by creating a study schedule. A structured plan helps you allocate time effectively and reduces anxiety about last-minute cramming. Break your preparation into manageable chunks; tackling smaller tasks feels less daunting.

Incorporate relaxation techniques such as deep breathing or meditation into your routine. These practices can help clear your mind before studying or taking practice tests, allowing better focus.

Physical activity also plays an essential role in reducing stress levels. Even short walks can refresh your mindset and boost energy, making study sessions more productive.

Don’t hesitate to reach out for support from friends or fellow test-takers. Sharing experiences and tips not only lightens the load but also builds confidence as you prepare together.

IELTS Writing: The most difficult paper?

When it comes to the IELTS exam, many candidates often label the writing section as the most challenging. This perception stems from multiple factors. First, time management becomes crucial here. You have just 60 minutes to complete two tasks: a descriptive report and an essay. It can be overwhelming for even seasoned writers.

Another hurdle is mastering coherence and cohesion in your writing. The examiner looks for clear organization of ideas and logical flow between them, which requires practice and familiarity with various structures. Many students find themselves struggling to present their arguments effectively under pressure.

Moreover, vocabulary plays a significant role in scoring well on this paper. While using complex words might seem impressive, clarity should never be sacrificed for complexity alone. Striking that balance takes effort but pays off.

Understanding assessment criteria is vital — your response must meet specific requirements outlined by the exam board if you wish to achieve your desired score.

As with any skill, preparation is essential. By identifying weak areas early on and tackling them head-on through targeted practice and feedback sessions, you can significantly improve your performance across all sections of the IELTS test — not just writing alone!

Visit Here - https://cambridgeenglishacademy.com/best-ielts-coaching-institute-in-delhi/

0 notes

Text

Adverbs and Their Types in English

Adverbs are one of the most versatile parts of speech in the English language. They add depth, clarity, and precision to sentences by modifying verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, or even entire sentences. Whether you’re a native speaker or learning English as a second language, understanding adverbs and their types is essential for effective communication. In this blog post, we’ll explore what…

#accent#adverb definition#adverb examples#adverb examples for students#adverb examples list#adverb examples sentences#adverb exercises#adverb fill in the blanks#adverb placement#adverb sentences#adverb types with examples#adverb usage in sentences#adverb usage rules#adverb vs adjective#adverbs for beginners#adverbs in English#adverbs of degree#adverbs of frequency#adverbs of manner#adverbs of place#adverbs of purpose#adverbs of time#american english#british english#common adverbs#conjunctive adverbs#daily prompt#English#English grammar adverbs#English learning

0 notes

Text

How should one utilize adjectives and adverbs in their IELTS examination?

Using adjectives and adverbs effectively in your IELTS test can enhance your writing and speaking tasks. Here are some tips:

Precision: Choose adjectives and adverbs that accurately describe the subject or action. Instead of using generic terms like "good" or "bad," opt for specific adjectives such as "excellent," "superb," "terrible," or "atrocious."

Variety: Demonstrate a range of vocabulary by using different adjectives and adverbs instead of repeating the same ones. This showcases your language proficiency and prevents your writing or speaking from becoming monotonous.

Context: Ensure that the adjectives and adverbs you use fit the context of the sentence or topic. Consider the tone and purpose of your writing or speaking task and select words accordingly. For example, in a formal essay, you might use sophisticated adjectives, whereas in a casual conversation, simpler adjectives might be more appropriate.

Comparisons and Contrasts: Use comparative and superlative forms of adjectives (e.g., "better," "best") and adverbs (e.g., "more quickly," "most effectively") when comparing or contrasting ideas, objects, or actions. This adds depth and clarity to your writing or speaking.

Adjective Order: Pay attention to the order of adjectives when using multiple ones to describe a noun. In English, adjectives typically follow a specific order: opinion, size, age, shape, color, origin, material, and purpose. For example, "a beautiful small antique silver vase."

Adverb Placement: Place adverbs carefully in your sentences to ensure clarity and coherence. Adverbs often modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs, so position them accordingly. Avoid separating an adverb from the word it modifies unless necessary for emphasis or clarity.

Grammar and Syntax: Use correct grammar and syntax when incorporating adjectives and adverbs into your sentences. Ensure agreement in number and tense, and pay attention to word order to maintain clarity and coherence.

Practice: Regular practice with adjectives and adverbs will help you become more proficient in using them effectively. Practice writing essays, completing speaking tasks, and engaging in conversations where you consciously incorporate a variety of adjectives and adverbs.

By adhering to these strategies and consistently honing your skills, you can elevate your proficiency in employing adjectives and adverbs, crucial for excelling in your IELTS examination. This will not only boost your performance but also augment your language aptitude through dedicated IELTS Coaching.

0 notes

Text

Books I Read in 2023

#40 - The Elements of Style, by William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White, illustrated by Maira Kalman

Rating: 4.5/5 stars

Reading this took me straight back to seventh-grade English class in 1992, when my seriously old-school teacher had us learning grammar rules from the Little Blue Book (I don't remember what it was actually titled, but that's how everyone referred to it) and our tests were a blank sheet on which we would write from memory the twenty-nine rules for proper comma usage, or the thirty most common prepositions, or whatever other element of the language we were studying at the time.

The highly ordered part of my brain loved this teaching method, which I have never experienced in any other setting. Many of my fellow students hated it, of course, and it's utterly fair to criticize rote memorization as both a teaching tactic and a test metric.

But I credit a large part of my ease in writing as an adult to those lessons, and this book made me nostalgic for them, with the dry wit and classic-literature examples and the sometimes-outdated advice (despite me reading an updated edition from 2000 that included additions about computers and "E-mail"--I had almost forgotten that was the accepted form of the word 23 years ago.)

Is all of the information presented useful in this day and age? No. Is the bulk of it still solid? Absolutely.

Would Strunk or E.B. White be horrified by how wordy my casual writing style is, littered with probably-unnecessary adjectives and adverbs? Yes. But despite the fact that the work is ostensibly a rulebook for proper usage, it frequently reminds the reader that rules can be bent or broken when it serves a purpose. It treats the ultimate goal of writing as clarity in communication, where the gravest sin a writer can commit is leaving the reader confused by poor word choice or sentence construction. As a helper to making one's writing clearer, this book is one of the best I've read on the subject.

Do I love the illustrations in this edition? No, the art style is not to my taste. But that's not the text's fault, and also I received this book as a gift, so it's going to stay on my shelf anyway. It's earned a spot there.

1 note

·

View note

Text

9.2) Conditional Forms (たら)

Hey everyone! 👋🏾 Sorry I’ve been MIA for a few months. I moved up to full time at my high school this school year, so work has been kicking my butt. Anyway, here we go with a new post, just for you!

Last time we talked about the conditional なら and 4 ways to use it. In this post, let’s look at a different conditional form and when you might use / see it in everyday Japanese.

Here is your vocabulary:

【The Grammar】

Japanese has many helping verbs that add extra meaning to verbs and adjectives. One of these helping verbs is た, which shows that a verb is in past tense. Because た is a helping verb, it turns out that there are different forms you can use for different purposes*. たら is the conditional form of た!

In the same way that た can be attached to verbs and adjectives, so can たら. There is also a たら version of the copula for nouns. In addition, it can also attach to the negative forms of verbs, adjectives and nouns.

【What It Means】

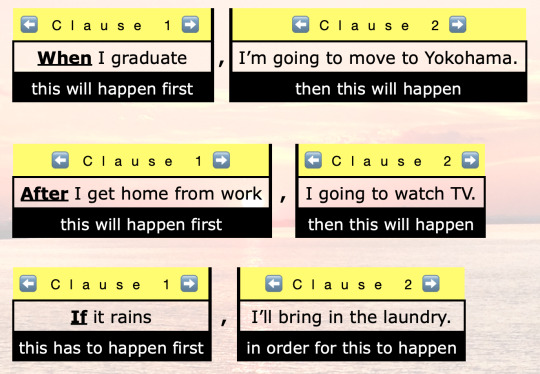

A たら clause indicates that there is an event that needs to happen first in order for a second event to happen. This will translate to either “when”, “after” or “if” clauses in English, depending on the situation. Take a look at the following 3 English sentences:

Even though たら has 3 different interpretations, the timing of the events is always the same. The event of the たら clause (clause 1) will always happen before the second event (clause 2).

【たら = When】

Let’s look at situations when たら means “when”:

①{昨日、デパートへ行ったら}、{友達に会った}。

= yesterday when went to the department store, saw friend

= Yesterday when I went to the department store, I saw my friend.

②{試験が済んだら}{長期休暇をとるつもりだ}。

= when tests were completed, take long vacation plan exists

= When my tests are done, I plan to take a long vacation.

【たら = After】

Sometimes, たら translates instead to “after”

③{薬を飲んだら}、{頭痛が治った}。

= After medicine drank, headache was cured

= After I took some medicine, my headache went away.

④{食べたら}{宿題をし始める}。

= after ate, homework will start

= After I eat, I’ll start my homework.

Notice that the literal translation of the たら clause is past tense however it’s the tense of the second clause that determines the real translation. Example 3′s second clause is in past tense, so the first clause will also become past tense. In example 4, the second clause is not in past tense, so the translation is not in past tense either.

【たら = If】

The majority of the time though, たら translates to “if”.

⑤{雨が降ったら}、{タクシーで行きましょう}。

= If rain fell, by taxi let’s go

= If it rains, let’s take a taxi (there).

⑥{お母さんがお金をくれなかったら}{どうしよう}。

= if Mother didn’t give us money, what should do

= If Mother doesn’t give us money, what should we do?

⑦{もしよかったら}、{コーヒーでも入れてくれませんか}。

= if it was good, can I receive you making some coffee =

If it’s OK, can you make some coffee for me?

In order to clearly show the “if” meaning of たら、the adverb もし is often used at the beginning of the sentence. It also helps to soften the meaning of the sentence.

【Alternate Reality たら】

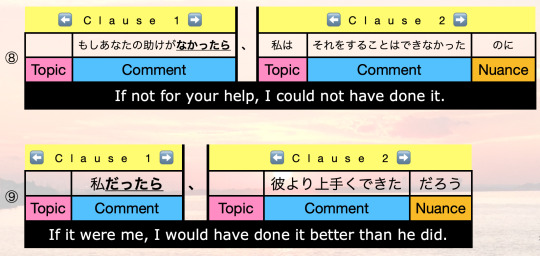

たら sometimes is used to talk about alternate realities. The nuance here is that either something didn’t happen or that if something didn’t happen the outcome would be very different.

You can see that example 8, the speaker imagines a reality where he/she didn’t have the listener’s help in the first clause. Because the second comment is something that is not good (できなかった) this ends up showing appreciation. In example 9, the speaker imagines a reality where he/she did something. The comment says that it would have been better so this ends up expressing disappointment / annoyance.

In these kinds of sentences, the nuance section is very important because it will tell you if the sentence is expressing appreciation, regret, disappointment or just imagining a different timeline. Common sentence endings are のに (for regret) and だろう (for asserting a point).

【たら = How About If...?】

The final way that たら sentences are sometimes used is for suggestions.

⑩ もうちょっと塩味をきかせてみたら?

= if you added a little more salt (that might solve your problem)?

= You should add a little more salt.

As you can see, the nuance is that by doing what comes before たら, it might be a solution to whatever is the problem. In keeping with たら meaning “if”, you can think of this usage as “How about if...?”. But a more natural way to think of this is a suggestive “you should...”.

【The Second Clause】

Let’s end by talking a bit about the second clause. One thing to remember is that it has to be something that the speaker can’t control. In example 1, seeing a friend wasn’t something planned so this sentence sounds natural. If you replaced 友達に会った with 服を買った, it would sound strange because buying clothes is something that you can control.

Example 4 might seem like it goes against this rule. The truth is, because we can’t control the future, starting your homework is taken as intent and not as forecasting the future. Japanese is very weary of saying that something will happen if it’s not 100% guaranteed to happen.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! I hope that now when you see たら tacked on to the end of words that you will have a better idea of what is going on. I hope that you also try using it in your daily conversation and see how your listener reacts. Smooth conversation means you did it right!

Next time, we’ll continue our look at conditional forms. See you then!

Rice & Peace,

– AL (アル)

👋🏾

* There are three forms of the た helping verb: (1) た (2) たら and (3) たろう.

たろう is rarely used but it asserts that something would have been the case. For example, “If he didn’t help me, I would have failed.” This is similar to the alternate reality section in this post.

#japanese#japanese grammar#learn japanese#japanese language#japanese lesson#japanese study#japanese vocabulary#japanese vocab#studying Japanese#japaneselessons#japanese langblr#learnjapanese#japanese studyblr#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語#日本語の勉強#一緒日本語#IsshoNihongo#japanese conditionals

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is a Run-On Sentence?

Clause (n): a unit of grammatical organization next below the sentence in rank and in traditional grammar said to consist of a subject and predicate. — New Oxford American Dictionary

Search the internet for “run-on sentences” and you’ll likely find examples of long lines (some run-ons, some not) by William Faulkner, Charles Dickens, Lewis Carroll, and other authors famous for their verbosity. Some sites (which will go unnamed) tell you that one of the iconic lines of twentieth-century American literature—the first line of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951)—is a run-on sentence.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

This is, indeed, a long sentence—63 words and six commas, to be exact—but it is not a run-on. On the other hand, this sentence is:

Julia likes cats, however, she prefers dogs.

Just seven words and two commas, but a run-on. (By the way, that last line is a fragment, a sentence lacking even one independent clause.)

How is the second sample sentence a run-on if the first is not?

The answer hinges on the definition of a run-on sentence. Contrary to popular belief, run-on sentences are not defined by length or complexity; a 1,000-word sentence could be grammatically correct and a four-word sentence could be a run-on.

A run-on sentence is something far more precise. It’s a sentence that contains two or more independent (aka main) clauses not properly separated. Generally speaking, independent clauses can be separated by a period, a semicolon, a colon, a comma and a conjunction, or a dash (though not all of these solutions work for all sentences).

We might fix the run-on above to read:

Julia likes cats. However, she prefers dogs.

or, more commonly:

Julia likes cats; however, she prefers dogs.

or even better:

Julia likes cats, but she prefers dogs.

The reason why the original “Julia” sentence is a run-on is fairly arcane: a conjunctive adverb like “however” cannot separate two independent clauses. Students preparing for the SAT and ACT should learn how to identify independent clauses, dependent clauses, relative clauses, relative pronouns, conjunctions, subordinators (words that make clauses dependent), and conjunctive adverbs—all terms and ideas that need to be understood in order to master the art of avoiding and fixing run-ons and fragments. This is likely the most important cluster of grammatical issues to master for both tests.

But my purpose here is not to unpack the nuances of these issues (you’ll need to take a class for that). It is simply to note that preparing for the SAT and ACT requires that students begin to see conventional English sentences as things constructed along pretty exacting guidelines. Sentences, like machines, are objects made out of properly connected parts.

Like an automobile, a sentence is made of interlocking units. Just as there are many correct and incorrect ways to build a car, there are countless ways for the parts of a sentence to interlock correctly or not. And just as a good auto-mechanic sees a car for its parts and knows exactly what to do under the hood to fix a mechanical problem, SAT and ACT test-takers need to be able to see sentences as constructed things made of clauses, which need to be connected with the right tools and in the right ways.

This is precisely the kind of thinking at work in Salinger’s opening sentence in The Catcher in the Rye. The sentence is something of a master class in English grammar.

If you really want to hear about it, | the first thing | you’ll probably want to know | is | where I was born, | and what my lousy childhood was like, | and how my parents were occupied and all | before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, | but I don’t feel like going into it, | if you want to know the truth.

This sentence contains nine clauses total, 7 dependent and 2 independent, all properly separated. A clause consists of, at minimum, a subject and a predicate. I have highlighted only those terms necessary to complete each subject and predicate and italicized all conjunctions used to connect clauses. Things get tricky at the beginning of the second clause, whose subject is “thing” and whose verb is “is,” followed by an entire dependent clause (“where I was born”) that acts as the object of the verb “is.” In this sentence, “you’ll probably want to know” acts as a dependent clause since it is contained within a larger independent clause.

As a whole, a good SAT or ACT grammarian should see this sentence like this:

Dependent clause 1, Independent clause 1 Dependent clause 2 Independent Clause 1 continued Dependent clause 3, and Dependent clause 4, and Dependent clause 5, Dependent clause 6, but Independent clause 2, Dependent clause 7.

We could dig into this complex sentence further by looking at, say, how Salinger subordinates those seven dependent clauses, or by considering how to identify when a clause begins and ends. But, again, the point here is not to explore all these complexities (though that’s an important task for those preparing for the SAT and ACT).

My point is at once much simpler and more challenging: it is to show you that sentences are made of smaller units called clauses, and that there are rules for connecting and separating these units from each other. This is all to say that improving one’s grammar isn’t about memorizing countless rules or running your eyes over countless pages of writing.

It’s first and foremost about changing the way you see sentences—as constructed machines made of individual parts rather than as finished wholes.

0 notes