#actions française

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#Dictionnaire de conscience révolutionnaire#France#Tradition#Révolution#Georges Sorel#Pierre-Joseph Proudhon#Maurras#Action Française#Cercle proudhon#Edouard Berth#Pierre de Brague#Egalité & Réconciliation#E&R#résistance et Réinformation#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

✍️Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), est un essayiste, philosophe et poète américain, chef de file du mouvement transcendantaliste américain du début du xixe siècle.

etude-generale.com

#citation#Citation du jour#Citation française#quotes#quote#quoteoftheday#beautiful quote#french quote#french#francais#francaise#Ralph Waldo Emerson#philosophy#philosophe#action#pensée

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

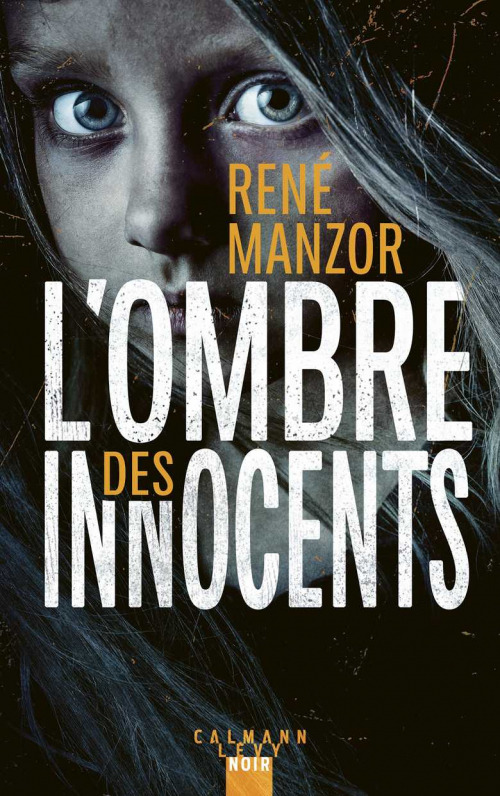

L'ombre des innocents

Auteur : René Manzor Titre : L’ombre des innocents Date de parution : 3 Janvier 2024 EAN : 9782702188620 – 365 pages 4eme de couverture : C’EST DANS L’OMBRE DES INNOCENTS QUE SE CACHE LE MAL Paris, bureau d’un éditeur bien connu. Alors que Marion Scriba, romancière, parle de son prochain polar, des policiers surgissent et l’interpellent, l’accusant du meurtre qui occupe la France entière…

View On WordPress

#action#aventure#Enfants#enlevement#enquête de police#Enquêtes criminelles#Espionnage#littérature#Littérature Française#Littérature Générale#Meurtre#militantisme#policier français#reseaux sociaux#Romans et nouvelles de genre#romans policiers et polars#sequestration#Suspense#thriller

0 notes

Text

⚜ Le Sacre de Napoléon V | N°23 | Francesim, Paris, 1 Fructidor An 230

At the Tuileries Palace, Ernest informs Emperor Napoleon V of a plot involving anti-monarchist extremists financed by public figures. The Minister of Justice, Jeanne Chautemps, with prudent wisdom, advises rigor and caution in the investigation, while Napoleon V insists on the need not to provide their enemies with ammunition.

Meanwhile, the Emperor's grandfather Louis sought legal advice. His lawyer reassures him of his right to take legal action, promising to handle the matter discreetly. With this procedure, Louis could gain access to secret defense documents.

Beginning ▬ Previous ▬ Next

⚜ Traduction française

Au palais des Tuileries, Paris, 1er arrondissement.

(Ernest) Le témoignage de Madame Mère n’a pas beaucoup aidé à l’enquête

(Ernest) Manifestement, ces extrémistes font partie de groupes anti-monarchistes financés par des personnalités publiques

(Ernest) L’assassinat de feu votre père n’est donc pas totalement dû à l’évolution d’un groupe de manifestants enhardis

(Napoléon V) Intéressant (Jeanne) L’empereur Napoléon IV a déjà échappé à plusieurs attentats durant son règne

(Ernest) L’enquête nous révèlera des noms et des adresses. Nous pourrons alors dissoudre légalement ces groupes dangereux

(Jeanne) Le ministre de l’Intérieur s’en fera une joie, M. de Tour

(Jeanne) D’ici là, poursuivez consciencieusement l’enquête. Nous ne devons faire aucun faux pas et être irréprochables

(Napoléon V) Ne donnons pas raison à nos opposants.

À Paris, 7e arrondissement.

(Louis) Merci, Maître.

(Louis) Je crains que mon petit-fils, le nouvel empereur, ne soit pas d'accord avec cette démarche. Que puis-je faire ?

(Jean) En tant que père de la victime, vous avez tout à fait le droit de vous constituer partie civile.

(Louis) Oui, mais mon petit-fils détient maintenant le pouvoir. S'il s'y oppose... Je ne souhaite pas d'affrontement, mais je veux que justice soit rendue pour mon fils.

(Jean) Je comprends vos réticences. Cependant, la justice doit suivre son cours, indépendamment des dynamiques familiales. Nous nous en assurerons ensemble.

(Jean) Avec votre accord, je m'occuperai personnellement de la rédaction et du dépôt de cette plainte.

(Louis) Et que se passera-t-il ensuite ?

(Jean) En tant que partie civile, vous aurez accès au dossier et pourrez demander des actes d'instruction supplémentaires. De plus, vous pourrez assister aux auditions et aux confrontations, et demander réparation pour le préjudice moral et matériel subi.

(Louis) Très bien, Maître. C'est parfait.

#simparte#ts4#ts4 royal#royal simblr#sims 4 royal#sim : louis#sims 4 fr#sims 4#ts4 royalty#sims 4 royalty#le cabinet noir#episode iii#sim : jeanne#sim : ernest#sim : oldlouis#sims 4 royal family#sims 4 royal simblr#ts4 royal family#ts4 royal simblr#ts4 royals#tuileries#paris#sim : jeanlawyer

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nancy Wake – 1945

©Australian War Memorial - P00885.001

Nancy Wake est une journaliste australienne engagée dans la Résistance française pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Elle s'engage dans le réseau Pat O'Leary chargé de recueillir, soigner et exfiltrer les aviateurs britanniques. Pendant cette période elle sera surnommée "la Souris blanche" par la Gestapo en raison de sa capacité à leur échapper.

Elle est ensuite recrutée par le Special Operations Executive (SOE). Entraînée en Angleterre, elle sera parachutée en Auvergne pour armer et coordonner les actions du maquis avec les opérations du débarquement en Normandie. En juin 1944 elle dirige l'attaque du local de la Gestapo à Montluçon.

Nancy Wake est la résistante la plus décorée de la Seconde Guerre mondiale avec notamment la Croix de chevalier de la Légion d'honneur et la Croix de guerre avec 3 citations.

#WWII#ww2#résistance française#french resistance#résistance française de l'intérieur#rfi#les femmes et les hommes de la guerre#women and men of war#nancy wake#la souris blanche#white mouse#1945

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

do we have good sources on the life and work of claire lacombe? /gen

Portrait probable de Claire Lacombe. Miniaturiste, Ducare. 1765-1798.

I am not the best person to answer this question, as I am currently delving deeper into my research on the group of the Enragés, particularly from a legal perspective, here https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/762409217481179136/jacques-rouxs-criticism-of-the-constitution-of?source=share (and also because I don't have much time). Perhaps @saintjustitude or @anotherhumaninthisworld, as well as other Tumblr users more specialized than I am on the subject, could provide better insights.

Nevertheless, I will offer my modest contribution on Claire Lacombe. The academic historian Antoine Resche has written a good biography of her, and historian Mathilde Larrère has also discussed her in depth. Unfortunately, I lost my notes from Jean Clément Martin’s excellent book La Révolte brisée: Femmes dans la Révolution française et l’Empire , as well as one of the most important references on revolutionary women, Dominique Godineau.

We know that Claire Lacombe was born in 1765 and was an actress who worked in Marseille,Lyon, Toulon then living in Paris. She was one of those women, like Théroigne de Méricourt, who proposed to take up arms to fight the tyrants. What I don’t understand is whether Lacombe was referring specifically to Louis XVI and La Fayette, or to other European monarchs as well (which is not impossible, as Théroigne de Méricourt, despite advocating reconciliation between the Montagnards and the Girondins, supported the idea of war). According to Mathilde Larrère, these two women, alongside Pauline Léon, are considered among the most well-known.

Claire Lacombe participated in the storming of the Tuileries in 1792 and received a civic crown like Louise Reine Audu and Théroigne de Méricourt. She was interested in the Jacobin Club before becoming secretary, then president, of the Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (Society of Revolutionary Republican Women). Along with other revolutionary women, she demanded the right to bear arms, something Olympe de Gouges, who wrote the Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne , did not dare to ask for in the article addressing men’s right to bear arms.

Claire Lacombe grew closer to Leclerc and became a member of the political group known as the Enragés. She made several demands: the trial of Marie Antoinette, greater rigor in arresting suspects, the prosecution of the Girondins by the Revolutionary Tribunal, and the application of the Constitution. She also advocated for more social rights, as outlined in the petition of the Enragés (which would later be taken up by the Exagérés, who, unlike the Enragés, were less suspicious of delegated power and believed in wielding influence beyond the revolutionary sections).

Lacombe was first arrested in September 1793 but released the following day.The majority of the Convention, including La Montagne and what are called the exaggerated or the Hébertists, fought the enragés ( especially Roux and Leclerc) during this period . Her second arrest in April 1794, alongside Leclerc and Pauline Léon, lasted longer. Unlike the latter two, who were released after Thermidor—possibly due to their connections with Tallien (one of the few good actions of Tallien, it should be noted)—Lacombe was not released until August 1795, which is rather strange. Could it be that she didn’t have the right connections to secure her release? Or perhaps, out of disgust for certain Thermidorians, she refused help? Or was she simply forgotten?

In any case, there is no further trace of her political activism. She went to Nantes to resume acting before returning to Paris, where she fell into debt. We don’t even know the date of her death (something she shares with the revolutionary Marie Anne Babeuf). It seems she is among those revolutionaries who have been too forgotten, as we do not know what became of her.

Sources: Antoine Resche Mathilde Larrère

Feel free to check out, as I mentioned, Dominique Godineau’s book Citoyennes tricoteuses, which is very interesting, as well as Jean Clément Martin’s book that I’ve mentioned.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just – Robespierre relationship described by XIXth century (1st half) historians

If Vinot with his Pls do not misinterpret can be considered as ‘how it’s going’ than that’s ‘how it’s started’:

François Mignet “Histoire de la Revolution française”, 1824.

“Unlike Robespierre, he [Saint-Just] was a man of action. Robespierre, understanding how much benefit he could get from this man, attached him to himself the time soon after the Convention started its sessions. Saint-Just, for his part, was charmed by the reputation of incorruptibility Robespierre had, his austere life and the closeness of their beliefs."

They are not a mentor and a disciple, but equal colleagues, though a big friendship is not implied either. Saint-Just has little "screen time" in this book, but when he appears he acts either out of his own will (the accusation of Danton is fully his and Billiaud will and work) or out of his and Robespierre unanimity.

That is how he encourages robespierre before Thermidor:

"Saint-Just, who understood from their [CSP members] silence, from some words escaped, from embarrasment or enmity on their faces that there was no time to waste, urged Robespierre to act."

Thomas Carlyle "French Revolution: A History", 1837

Strangely, he didn't finde a place between his wordplay to say anything on our matter. And thanks god, because it would be ablolutely ahistorical, just look how he describes Saint-Just:

Alphonse de Lamartine "Histoire des Girondins", since 1847

"At that time Robespierre and young Saint-Just, one already famous, the other still unknown, lived in that familiar intimacy wich often unites a master and his disciple."

"It was him [Saint-Just] who, in endless conversations during the long nights under Duplay's roof, fought what he called weaknesses of Robespierre's soul and his disgust with shedding the king's blood."

"Robespierre was the only one man who Saint-Just worshiped as a suprime thought regulating the Republic."

Lamartine depicts Saint-Just always translating Robespierre's will in the Convention, but in privat he, from the very beginning, has his own mind and, closer to the end, begins to dominate.

(Now I feel that I have to notice that it's not me quoting only about Saint-Just, but Lamartine seeming to be uninterested in Robespierre in this matter. Anyway, this book has Saint-Just striping so it's still good.)

Louis Blanc "Histoire de la révolution française", since 1847

"He had a misterious attraction to Robespierre, an irresistible one that defeated him, that survived their fall and was preserved even on the eshafaud."

"Robespierre himself, already partly changed by the endless persecutions by Gironde, couldn't resist. And everyone noticed that his blood soured and altered in his veins when he put on the Deianira's shirt that was to him a friendship of Saint-Just."

Though the last quote presents Saint-Just in a bad light, the author is actually pro-Saint-Just. I was shocked when I went thorough my bookmarks and found out that this two quotes are the only one (except the one in wich the auther is extremelly disappointed by Robespierre finally followin Saint-Just in Danton Execution Question), since it was the book that made me believe in their outstanding friendship. And then I realised that it just depicts them here and there, colorefully and with details, agreeing and arguing, being good pleople, not being good peaople and so you conclude by yourself: there was a Feeling.

On this good note I cease.

#frev#french revolution#saint just#robespierre#no really saint-just striping is the best part of lamartine

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayotte

Un tiers de la population est sans papiers. Seule la moitié des habitants est française (ayant droit aux aides). Les statistiques concernent les habitations cadastrales (très minoritaires), et on sent le déni colonial partout dans les analyses journalistiques.

À Mayotte, on est dans les affres les plus extrêmes de la République. Une population blanche et assimilée, privilégiée de fait, utilise au quotidien l’avantage d’une population sous-payée qui vit sous les radars et au rabais, du fait de logements informels, de salaires au noir et d’une volonté de se faire oublier.

Ces populations échappent donc à toute règle, qu’elle soit sanitaire ou locative. Les propriétaires des parcelles indiquaient certainement qu’elles étaient squattées, mais les logeurs et les loyers existent partout ! Les propriétaires fonciers touchaient-ils une part des loyers (vu la densité de masures au mètre carré, la somme globale doit être conséquente) ? On ne le saura pas in fine, mais cet argent partait forcément quelque part… On peut imaginer, en revanche, la collusion tacite des autorités et les corruptions administratives et policières qui permettent à ces situations de perdurer. On les constate jusqu’en métropole, c’est dire...

Les revendications de ces travailleurs n’ont jamais abouti qu’à des sanctions pénales, des expulsions préfectorales, qui ne peuvent aboutir vu les relations avec les Comores. En revanche, les cercles mafieux, les marchands de rêve et les proxénètes, eux, échappent à toute mise au pas. Mais pas les soi-disant "meneurs politiques" des émeutes revendicatrices et donc démocratiques. Ces derniers se retrouvent déportés et neutralisés d’une manière ou d’une autre.

Et c’est là que la vase de la politique postcoloniale resurgit sous la fine pellicule de ciment tout frais. On retrouve du Bob Denard, des juntes mafieuses islamistes, des retournements d’ennemis et des sabordages d’anciens alliés. Cela ressemble à d’autres situations coloniales, mais celle-ci est tardive (1975) et tellement éloignée. Et elle concerne un président encore connu : Giscard.

Comme en Kanaky ou à Mururoa, le lointain révèle nos parts les plus sombres et les salauds les plus aventuriers de nos gouvernements. Il faut bien comprendre toutes les opérations secrètes des années 1975-1980, et celles qui vont suivre, pour estimer les soi-disant "indépendances" des pays et territoires sous l’emprise française.

Cela se traduit dans l’imaginaire et la création par la vague des romans d’espionnage des années 1980, notamment la série SAS. Gérard de Villiers avait ses entrées chez les salauds opérationnels. "Mais pas que" ! En reprenant une enseigne de transport aérien (au départ), puis sa concurrente Air France, en mélangeant les symboles du luxe petit bourgeois (Cognac Gaston Delagrange VSOP, Seiko Quartz pour SAS) et les attributs aristocratiques, il magnifiait un sexe de droite (souvent tarifé ou conditionnel, pornographique, éjaculateur précoce, violent, souvent abusif ou torturant).

Ces récits vantent les espions, barbouzes, agents secrets et leurs gadgets électroniques, mécaniques, connectiques, leurs poisons et leurs armes. Tout cela nous ramène à l’actualité explosive et à la tech meurtrière, qui a toujours la préférence de nos dirigeants. (Les années 1980, c’est le gadget partout et la poudre de perlimpinpin dans le nez ou dans les veines, pour mémoire.)

La France reproduit dangereusement ses dérives postcoloniales et ses dénis d’ingérence et de manipulation. Une transparence sur les actions passées, un enseignement des pratiques réelles et des faits permettraient de ne pas projeter toute une population métropolitaine dans des fantasmes républicains d’une France réifiée.

Non, De Gaulle n’était pas un "émancipateur" des peuples colonisés par leurs indépendances, et surtout pas par leur assimilation citoyenne. Il visait "l’intérêt supérieur de la nation", qui se confondait depuis l’avènement de la République avec celui des grandes compagnies marchandes coloniales.

Non, Giscard ne souhaitait pas l’accès des peuples colonisés à une revendication "majoritaire" en leur sein, quelle qu’elle fût. Les gouvernements successifs ont toujours privilégié l’accès aux ressources, la mainmise économique et les intérêts particuliers, ceci par des opérations secrètes, des manœuvres politiciennes et économiques. Ce sont des faits qui méritent l’éclairage pour une compréhension des situations catastrophiques qui s’enchaînent et de l’incurie des services de l’État aux confins de ses territoires.

On rappelle que ces services sont en mesure d’affréter à prix d’or un jet dans l’heure pour acheminer un tout nouveau Premier ministre vers ses obligations cumulatives d’élu, d’où il se permettra d’allouer une somme dérisoire, mais prélevée sur les fonds publics, à l’aide humanitaire pour Mayotte.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

🤚 ^^

🤚Book recs

This is hard because I had stopped reading for many years and I've been trying to get on track in the last year. Overall, I have read many books, but the only ones I feel like recommending are all historical essays about the French Revolution and despite some being in Italian and French I will mention them anyway, given that some of my followers are also from Italy and France ^^

1. P. McPhee's Liberty or Death.

This book is very dear to me, because it was my first ever frev book! I recommend it because it's heavily sourced, explains very clearly the causes and consequences of the Revolution and the history is told, through the quoting of primary sources and accounts, from the people's pov, something quite unique in frev historiography. Unfortunately, this last point can also be a downside, especially for those who know absolutely nothing of the French Revolution: some of the key events sometimes get discussed in a few lines to give much more space to how they were perceived by the population. Not only this may lead to an oversimplification of said events, but also to confusion regarding their chronological order. At the end of the book there's a timeline though, which I suggest to consult in case you feel lost while reading.

I would say it's accessible to everyone interested in the topic and who has an adequate level of English to understand it. Of course, the read will be much more fluid if one already knows a bit about the French Revolution.

2. M. Vovelle, La Révolution Française 1789-1799.

This book exists only in French and Italian sadly. I say sadly, because despite not having read it in full, it's an excellent and concise summary of the French Revolution. It's perfect for literally everyone: students who have to prepare an exam, historians who have to quickly revise it and amateurs who want to be introduced to the French Revolution through something that's not too big or overwhelming. What I like about it, it's the fact it's short, but it manages to perfectly highlight the main events and key figures, showing how important the Revolution was and its consequences in our present era.

I believe an English equivalent would be Soboul's The French Revolution 1789-1799.

3. M. Reinhard, Le Grand Carnot vol. I & II.

Yes, a specific biography, I mean it seriously. Lazare Carnot's life is truly fascinating, but in case you are not interested in him at all, I would still recommend it since it's a nice example of how it's perfectly possible to make an amazing, detailed, well sourced, as impartial as possible work on a beloved historical figure. Because Reinhard likes Carnot, but he cleverly manages to conceal it, by exposing his merits, epic fails and controversial actions; even when he enters the realm of speculation, he does it relying on sources, primary most of the time. Moreover, he is rather knowledgeable about the historical period Carnot lived through, thus the latter's words and decisions get explained in their relative historical context, making it easier to decipher Carnot's motives.

Lastly, it's godly and elegantly written. I genuinely can't wait to fully devote my reading sessions to it, because until now I have only read separate chapters and excerpts.

4. Anything about Nikola Tesla.

Seriously guys, I can't even find the right words to explain how important that genius was, and how unfairly poorly he was treated. Each of us would have something to learn from such a brilliant, devoted and altruistic mind.

#ask game#ask#someone should give me the Marcel Reinhard simp card#also the Vovelle one after what I have learnt about him :3#aes.txt#frev#book recs

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Further complications came when a section of the French Army rebelled and openly backed the Algérie française movement to defeat separation. Revolts and riots broke out in 1958 against the French government in Algiers, but there were no adequate and competent political initiatives by the French government in support of military efforts to end the rebellion owing to party politics. The feeling was widespread that another debacle like that of Indochina in 1954 was in the offing and that the government would order another precipitous pullout and sacrifice French honour to political expediency. This prompted General Jacques Massu to create a French settlers' committee[20] to demand the formation of a new national government under General De Gaulle, who was a national hero and had advocated a strong military policy, nationalism and the retention of French control over Algeria. General Massu, who had gained prominence and authority when he ruthlessly suppressed Algerian militants, famously declared that unless General De Gaulle was returned to power, the French Army would openly revolt; General Massu and other senior generals covertly planned the takeover of Paris with 1,500 paratroopers preparing to take over airports with the support of French Air Force units.[20] Armoured units from Rambouillet prepared to roll into Paris.[21] On 24 May, French paratroopers from the Algerian corps landed on Corsica, taking the French island in a bloodless action called Opération Corse.[20][21] Operation Resurrection would be implemented if De Gaulle was not approved as leader by the French Parliament, if De Gaulle asked for military assistance to take power, or to thwart any organized attempt by the French Communist Party to seize power or stall De Gaulle's return. De Gaulle, who had announced his retirement from politics a decade before, placed himself in the midst of the crisis, calling on the nation to suspend the government and create a new constitutional system. On 29 May 1958, French politicians agreed upon calling on De Gaulle to take over the government as prime minister. The French Army's willingness to support an overthrow of the constitutional government was a significant development in French politics. With Army support, De Gaulle's government terminated the Fourth Republic (the last parliament of the Fourth Republic voted for its dissolution) and drew up a new constitution proclaiming the French Fifth Republic in 1958.

The Fourth Republic is said to have "collapsed," which isn't untrue per se, but omits the fact that it collapsed under pressure of an imminent right-wing coup to prevent the loss of colonial possessions. The army was preparing to occupy Paris and declare de Gaulle President by force. Compare the coup in Spain that launched the Spanish Civil War, except there the government wasn't willing to capitulate (and the coup did not immediately succeed).

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

What did Marat think of the CPS members?

Hi, anon! 👋

First of all, I'd like to apologize for taking so long to answer your question. I was very busy with various things involving my end-of-year studies and could only reply now. I hope you weren't upset or disinterested!

Secondly, I didn't quite understand whether your question meant to ask what Marat thought of the CSP in general or what he thought of each of the members individually. So I decided to answer both questions!

It is important to note that, in my research, I have not been able to find much information about Marat's concrete views on the committee itself, nor have I been able to find his views on all the members. This is probably due to the fact that the CSP was created in April 1793, an extremely turbulent year for the Revolution in general and somewhat turbulent in Marat's political life, who, although he never stopped publishing his newspaper, didn't have much time to write. But it's possible that I'll find something more on this subject in the future, so I'll update this post whenever possible.

It can be said that, initially, Marat was committed to the creation of the CSP and was, in a way, in favor of it. Despite this, he never stopped criticizing and imposing his opinions on the organization of its functions and members. In issue no. 163 of his newspaper, Le Publiciste de La Republique Française, published the day after the official creation of the Committee of Public Safety, he points out some "ridiculous defects" in the draft of the Committee of General Defense presented by Isnard for the creation of the CSP. It's a rather poor quality document, which made my translation difficult, so bear in mind that it is subject to errors.

"This was the plan Isnard presented to the General Defense Committee. In vain did I search this plan for the men responsible for providing the means to repel enemies from without and within. I saw in it nothing more than a simple surveillance of the operations of the Minister of War and the Navy and an unlimited search for suspicious citizens, under the pretext of pursuing the schemers. This omission of the most important care and this accumulation of the very different functions of two committees into just one revolted me: I showed that this obviously tended to undermine tyranny, without fulfilling the main objective, which is the defense of the state. My reasons were heard, and the Committee of Public Safety was able to restrict itself to putting ministerial agents into action, in charge of carrying out means of general defense, with the simple power to request the assistance of the Committee of Security for the arrest of evildoers or suspicious persons."

In addition to this excerpt, there are a few other issues of Le Publiciste de La Republique Française in which Marat criticizes the poor functioning of the Committee of General Security. You can find his complaints mainly in the issues from April to July 1793. Despite these harsh criticisms, Marat seemed to believe that the creation of the CSP could bring benefits, or at least he defended the creation of a committee made up of "capable and politically enlightened patriots to put the state on the defensive". This thinking, however, changed dramatically just a few months later. This could be seen in the last issue of the LPRF, which was published the day after Marat's death, on July 14.

"What should we think of the Committee of Public Safety, or rather its leaders, given that most of its members are so careless that they attend committee meetings for only two hours out of twenty-four, ignore almost everything that is done there and perhaps have no knowledge of this room. They are very guilty, no doubt, for taking on a task they don't want to do: but the leaders are very criminal for carrying out their duties in such an unworthy manner."

It is possible to conjecture, especially from this excerpt, that Marat was very dissatisfied with the CSP - which, at the time, still didn't have very consolidated power - and one of the main reasons for this was its members, the vast majority of whom Marat despised. In the following excerpt, he talks about Bertrand Barère, calling him the "most dangerous enemy of the fatherland".

"Among them is one whom the mountain has just renamed in a very reckless manner and whom I consider to be the country's most dangerous enemy. This was Barére, who Sainte-Foi pointed out to the monarch as one of the constitutionalists with whom he could work best. As for me, I am convinced that he is swimming between two waters to see which party will win the day; it is he who has paralyzed all the measures of force and who is tying us up like this to let them cut our throats. I invite him to give me a reminder by finally making a statement so that he is no longer seen as a monarchist in disguise."

Barère is also mentioned by Marat in an interesting pamphlet he made in 1792, when the elections for deputies to the National Convention were taking place. The pamphlet is called Marat, l'Ami du Peuple, aux amis de la patrie and is available to read here (p. 310). In it, Marat comments on some of the candidates for deputies and shares his opinions about them with his readers, making a list of his nominations and also of those who, according to him, should be avoided at all costs. Barère was on the list "of unworthy people proposed by the author of La Sentinelle, with the aim of serving the faction of the enemies of liberty".

"Barère de Vieuzac, a useless man, without virtue or character".

Following the same pamphlet, Marat mentions other future members of the CSP: Billaud-Varenne, Tallien and Robespierre. They are included in the "list of men who have most deserved the patriciate".

Robespierre & Billaud: "All you have to do is name them, they are the true apostles of freedom; woe betide you if they are not the first objects of your vows."

Tallien: "Excellent patriots, who'll always be narrating with the intrepid defenders of the fatherland."

To say the least, we can consider that this list has aged a little badly. I haven't found any further mention or statements by Marat about those mentioned above (with the exception of Robespierre and Barère), so it's possible that his opinion changed from 1792 to 1793, although we don't have any proof of this in principle.

With regard to other members, such as Hérault, Carnot and Couthon: their names only appeared a few times in L'Ami du Peuple, and it's not very easy to identify exactly what Marat thought of each of them. In issue no. 614, Marat refers to Couthon as a "patriot", which I think is a good thing. Hérault, however, doesn't seem to be held in Marat's esteem, especially according to this excerpt from issue no. 510, in which he puts him on the same level as people like Bouillé and Necker, whom, to say the least, Marat didn't like very much.

As for Robespierre, Marat always supported him. In a way, they both always supported each other; Marat did so until his death. The two were never friends as such - in fact, little is known about the personal aspect of their relationship. Throughout the Revolution, they often shared very similar opinions about various situations, such as the case of the Nancy garrison, Simmoneau's death and especially the opposition to the revolutionary war, when both were politically isolated. Because of this, they were able to count on each other's support. Although it's not quite true to say that they were friends or that they had any affection for each other that wasn't entirely political. I plan to write a more complete post about these two in the future!

Apparently, Marat also had a positive opinion of Saint-Just. He appreciates his conduct in a discussion in issue no. 240 of LPRF, and there is also the fact that Saint-Just seemed to be favorable to Marat, which can be seen in some of his writings and speeches at the Convention. Unfortunately, I couldn't find any writings by Marat about other CSP members such as Lindet, Prieur and the others.

From all this, it can be concluded that Marat's opinion of the CSP members is somewhat fragmented, since he has different thoughts about each of them. In any case, it is certain that, at least before his death, Marat was against the committee and had a strong distrust of it. Let me know if you have any questions or corrections about any of the information I've included in this post, anon, and I hope I've helped you. :)

#marat#csp#cps#comité de salut public#committee of public safety#jean paul marat#frev#french revolution#asks#my posts

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le ministre de l’Intérieur s’est dit mardi 21 janvier «très proche» du «combat» de ces «féministes identitaires», proches de toutes les sphères d’extrême droite possibles et imaginables.

C’est leur «combat», et c’est aussi le sien. Mardi 21 janvier, Bruno Retailleau a affiché son soutien admiratif au collectif Némésis, ces «féministes identitaires» (même si elles ne revendiquent plus ce terme qu’elles chérissaient initialement) qui dénoncent les violences faites aux femmes uniquement sous un prisme raciste et sont proches d’à peu près toutes les sphères d’extrême droite – des plus institutionnelles comme le RN aux plus radicales, royalistes et nazifiantes, comme l’a largement documenté Libé. Interrogé par leur porte-parole Alice Cordier (un pseudo) sur une possible dissolution du groupe antifasciste la Jeune Garde (dont était membre Raphaël Arnault avant d’être élu député LFI, avec qui Cordier est en guerre ouverte), le ministre de l’Intérieur a donc validé cette possible «solution» et, surtout, «félicité» le groupuscule pour son action , s’en disant solidaire : «Némésis […], bravo pour votre combat, vous savez que j’en suis très proche.»

Cette déclaration d’amour était faite en tant qu’invité d’honneur du centre de réflexion sur la sécurité intérieure , un think tank cofondé par l’avocat Thibault de Montbrial, ex-conseiller sécurité de Valérie Pécresse à la présidentielle 2022 avant de rejoindre le «comité stratégique» du média zemmouriste Livre noir (devenu Frontières) en 2023. «Pour la première fois depuis notre création, nous avons l’impression d’être entendues par les pouvoirs publics. Nous ne lâcherons rien», s’est gargarisé sur X le collectif Némésis , qui fait régulièrement la fête et prépare ses actions dans le manoir de Jean-Marie Le Pen mis à leur disposition – elles étaient aussi présentes à la messe d’hommage au fondateur du FN.

«Immense fierté»

Extatique après les louanges tressées et ce brevet en normalisation décerné par le ministre d’Etat, Alice Cordier a quant à elle exulté : «Après des années d’humiliations, de comptes bancaires qui sautent, de réseaux sociaux censurés, de violences par des militants d’extrême gauche, d’articles à charge… Après tout ça, j’ai été félicitée par notre ministre de l’Intérieur, Bruno Retailleau. Immense fierté.» Enfin la consécration pour celle qui a débuté avec les royalistes de l’Action française et a été proche de la bande néonazie des Zouaves Paris qui, après leur interdiction par les autorités, ont réactivé le GUD et poursuivi dans la violence.

Peu nombreuses avec 200 militantes revendiquées, ces spécialistes d’une agit-prop xénophobe s’assurent régulièrement une belle visibilité médiatique. La réponse de Retailleau à leur interpellation sur la Jeune Garde a d’ailleurs été relayée par les médias traditionnels mais aussi, goulûment, par ceux de la fachosphère : Valeurs Actuelles, Frontières, Fdesouche… La directrice de la publication de Boulevard Voltaire, Gabrielle Cluzel, a ainsi salué sur X le premier flic de France, «bien plus courageux» que son prédécesseur Gérald Darmanin, qui n’aurait jamais félicité ainsi le collectif, selon elle. En réponse, Alice Cordier s’est esclaffée : «Darmanin nous aurait dissous s’il avait pu.» C’est dire.

#quel chien absolu. quelle sous-merde ce type#bruno retailleau#france#french#nazism#racism#far right#upthebaguette#bee tries to talk

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS SCREENSHOT UM COME ON PLEASE THE IMAGERY IS UUUUUHHHH

why on god’s green earth is there a triskell (celtic symbol) on a jar meant to trap a japanese trickster spirit. and why was there a fleur de lys (symbol of french royalty) on the bullet before. yeah if it’s the argents it’s french but it’s pretty precise esp if they’re supposed to be descendants of the people who killed the beast of gévaudan this is french peasantry you guys

#french royalty destroying celtic culture in france and in bretagne but like BADASS#also the fleur de lys today is VERY MUCH a huge right wing nationalism symbol in france like fascism for real it's the symbol of the action#française for example so it's weird for sure

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I should have been French”: Rebecca Ferguson, the secrets of the heroine of Dune

MEETING - After taming Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible, the flamboyant Swede is starring in the second part of the adaptation of Dune, the famous book by Frank Herbert, by Denis Villeneuve.

A great director knows how to give depth to a secondary character in just a few shots; a great actress, she knows how to restore this substantial marrow by exploiting these moments - even the briefest - which are granted to her on the screen. A feat that Rebecca Ferguson accomplishes several times in the second part of Dune, piloted by Denis Villeneuve. A necessary know-how since she takes on by far the most complex and mysterious role in this cinematographic fresco adapted from the inexhaustible original work of Franck Herbert: Lady Jessica, a woman capable of controlling the actions of others through simple intonation of her voice, being able to decide the sex of the child she is carrying while being able to communicate with him.

However, she is surrounded by a cast that would make anyone's head spin (Timothée Chalamet, Christopher Walken, Léa Seydoux, Javier Bardem, Stellan Skarsgard, Josh Brolin, Charlotte Rampling...), but this 40-year-old Swede manages to make her memorable performance. Nothing suprising. Ferguson went to a good school. The best, perhaps, for learning to flourish without being stifled by such a team assembled in the middle of one of the biggest productions of the year.

In 2015, then unknown to the general public, she was cast alongside the biggest Hollywood star in one of the most famous franchises on the planet: Tom Cruise in Mission: Impossible. A complete unknown, she must replace Jessica Chastain who refused the role of Ilsa Faust - a spy supposed to rival Ethan Hunt, played by Cruise, in muscle and charisma. Where the “James Bond Girls” left their mark in just one film, Ferguson established herself as the equal of her imposing partner in three episodes of Mission: Impossible and won the hearts of the public.

“It’s romantic, it’s sexy”

As we have understood, the Nordic woman is not afraid of taking on hot-blooded roles. “Please don't ask me how it feels to play powerful women,” she begs, taking off her heels before sitting down on the sofa at the Bristol in Paris, where we meet her. Teasingly, we ask her this question. She counters with a knowing and amused “Oh, fuck off”.

Then stops to order food. A green salad with the dressing on the side and “some protein, like fish or whatever.” Sad menu. Necessary, no doubt? She has to catch a train just after the promotion of Dune to join the filming of the second season of Silo, an excellent series produced and broadcast by Apple TV - but shunned by the audiences (like all the Apple brand's productions). And a bowl of fries,” adds the actress. Phew

So as not to completely forget powerful women, we ask her questions about the continuation of this career which is taking off like a rocket. “I would love to play in smaller, more intimate projects, where we have a little more say in the development of the story or the characters,” admits the actress. "The kind of project that many studios no longer want to support.”

Like those in which his costar from Dune, Thimothée Chalamet, debuted? “Yeah!”, replies the one who doesn’t speak French, but naturally places words from our language in the conversation. “I should have been French, anyway.” For the fries? “No, for the language, its movement, its sensation… there is an attitude. It’s romantic, it’s sexy.” It's never too late, Rebecca.

translated from french for @rebeccalouisaferguson

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚜ Le Cabinet Noir | N°26 | Francesim, Palais des Tuileries, Paris, 9 Fructidor An 230

In a historic televised address, Emperor Napoleon V, unexpectedly, decides to temporarily hand over power to his beloved wife, Empress Charlotte, thereby instituting a Regency. This unexpected announcement surprised the French public, who had anticipated hearing about the first political actions of his reign. To reassure the nation, Napoleon explains that the Empress will be supported by a trusted council, led by Imperial Prince Henri, who will ensure the continuity and greatness of Francesim.

Beginning ▬ Previous ▬ Next

⚜ Traduction française

Dans une annonce télévisée historique, l’Empereur Napoléon V, contre toute attente, décide de céder temporairement le pouvoir à son épouse bien-aimée, l’Impératrice Charlotte, marquant ainsi la mise en place d’une Régence. Cette déclaration inattendue a surpris le peuple français, qui attendait plutôt les premières mesures politiques de son règne. Pour rassurer la nation, Napoléon indique que l'Impératrice sera épaulée par un conseil de confiance, présidé par le prince impérial Henri, qui veillera à la continuité et à la grandeur de la Francesim.

(Napoléon) Français, françaises,

(Napoléon) C’est avec un profond sentiment de responsabilité et de dévouement envers notre grande nation que je m’adresse à vous aujourd’hui.

(Napoléon) Je veux servir la Francesim avec discernement. Pour cela j’ai, comme les Empereurs avant moi, bien des conquêtes à faire.

(Napoléon) Afin de répondre à toutes les exigences qu’implique mon rôle, j’ai pris la décision de parfaire ma formation militaire à l’Ecole Navale.

(Napoléon) J’ai la ferme conviction qu’elle sera bénéfique à tout l’Empire et renforcera notre position sur la scène internationale.

(Napoléon) Durant cette période, je crois satisfaire l’opinion publique, en même temps que j’obéis à mes sentiments pour l’Impératrice, en la désignant comme Régente.

(Napoléon) L’Impératrice sera assistée par un Conseil composé d’hommes ayant ma confiance, le prince impérial Henri à sa tête. Ensemble, ils travailleront pour la grandeur de la Francesim

(Napoléon) Montrons qu’une nation où règne la confiance résiste aux emportements, et que, maîtresse d’elle-même, elle n’obéit qu’à l’honneur ou à la raison

#simparte#ts4#ts4 royal#royal simblr#sims 4 royal#sim : louis#sims 4 fr#sims 4#ts4 royalty#sims 4 royalty#charlotte's regency#le cabinet noir#sims 4 royal family#sims 4 royal simblr#ts4 royal simblr#ts4 royal family#paris#tuileries#address#ts4 storytelling#ts4 story#ts4 simblr#sims 4 royal legacy

42 notes

·

View notes