#Zulu ethnic group

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Umemulo: The Traditional Zulu Coming-of-Age Ceremony for Women

Umemulo, a traditional Zulu coming-of-age ceremony for women, holds a significant place in the rich tapestry of Zulu culture. This profound ritual, deeply rooted in tradition, serves as a rite of passage, symbolizing the transition from girlhood to womanhood. Typically performed when a young woman reaches the age of 21, Umemulo can also be carried out at other stages of a woman’s life, embodying…

View On WordPress

#African History#South Africa history#traditional Zulu dance#Ukusina#Umemulo#Zulu coming-of-age ceremony#Zulu ethnic group#Zulu History

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

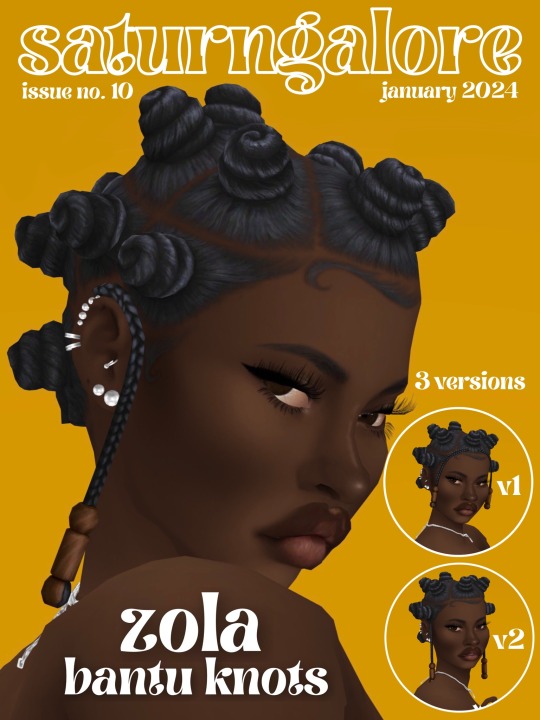

zola bantu knots ⭐️

hiii im back and here’s my first hair of 2024! it’s a very simple but super cute edit of the base game bantu knots where i have added front and side braids with beads to it! im not an expert on traditional african hairstyles (so pls correct me if im wrong!!) but it’s often noted that bantu knots either originated or were popularized by the zulu ethnic group in southern africa. so, i picked a zulu name (zola) for this hairstyle! enjoy! 💛

base game compatible (bgc)

maxis palette (24 swatches)

teen-elder

fem frame (it’s enabled it for both frames but the hairline is glitchy for masc frames)

not hat compatible (some accessories can fit!)

clipping might occur with all versions (depending on a sim’s ear, face, and/or body shape)

custom thumbnails

disallowed for random

all lods

please tag me if you do use my cc! i would absolutely love to see it! also, please let me know if you encounter any issues with my cc! here’s my tou. tysm! <3

download via simsharefile (sfs) or on patreon - ALWAYS FREE!

tysm to cc rebloggers! @public-ccfinds @sssvitlanz

#ts4#sims 4#the sims 4#black simblr#black simmer#ts4 cc#ts4cc#s4cc#sims4#sims 4 cc#s4mm#ts4 hair#ts4mm hair#ts4mm#ts4 maxis match#publicccfinds#sims 4 maxis match#🪐 cc#saturngalore#chantelle diang#nykhor chantelle diang

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

African Resistance Movements Against Colonialism: A Garveyite Perspective

“Rise Up, Ye Mighty Race!”—The Spirit of Resistance and Liberation

Introduction: The Garveyite Lens on African Resistance

Marcus Garvey, the great Pan-Africanist and leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), championed African self-determination, unity, and economic independence. His teachings emphasized that colonial rule was not merely a political imposition but a spiritual and economic stranglehold that sought to erase African sovereignty and dignity.

From a Garveyite perspective, African resistance to colonialism was not just about territorial control—it was about reclaiming African identity, self-sufficiency, and the destiny of the Black race. The heroes of these movements were not just warriors but visionaries who embodied Garvey’s call: “Africa for the Africans, those at home and those abroad!”

1. Early Resistance: Fighting for Ancestral Lands and Autonomy

Before European colonization took full control, African kingdoms and societies fiercely resisted foreign domination. Many of these struggles were aligned with Garvey’s ideals of self-reliance and strong leadership.

The Ashanti Wars (1823–1900, Ghana): The Ashanti Empire, led by rulers such as Asantehene Prempeh I and Queen Yaa Asantewaa, waged multiple wars against the British. Yaa Asantewaa’s leadership in the 1900 War of the Golden Stool exemplified the defiant spirit Garvey championed: African women and men leading their own struggles, refusing foreign rule.

The Zulu Resistance (1879, South Africa): Under King Cetshwayo, the Zulu military defeated British forces at the Battle of Isandlwana, a powerful example of African strategic brilliance. Garvey would have seen this as proof that African people, when united, could stand against European imperial forces.

The Maji Maji Rebellion (1905–1907, Tanzania): A widespread uprising against German rule, where different ethnic groups united under spiritual leadership. It echoed Garvey’s belief in unity as the key to liberation.

These wars proved that Africa was never passively colonized. The struggle for sovereignty was present from the beginning.

2. Pan-Africanism and the Rise of Organized Resistance

As colonial rule tightened, African resistance evolved into more structured political movements. This shift aligned with Garvey’s vision of a global African awakening.

The Ethiopian Resistance (1935–1941): Emperor Haile Selassie’s defiance against Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia was a monumental moment for Pan-Africanists worldwide. Garvey saw Ethiopia as a symbol of unbroken African sovereignty, and Selassie’s resistance was a rallying cry for Black liberation worldwide.

The Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960, Kenya): The Kikuyu-led Mau Mau rebellion against British rule was one of the most militant anti-colonial struggles. It embodied Garvey’s call for Africans to seize their freedom by any means necessary.

The Liberation of Ghana (1957): Kwame Nkrumah’s leadership in achieving Ghanaian independence was a direct continuation of Garvey’s ideals. Nkrumah, deeply influenced by Garveyism, declared: “The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.”

These movements reflected Garvey’s belief that African unity and self-determination were inevitable forces that colonial powers could not suppress forever.

3. The Role of African Diaspora and Garvey’s Influence

Garveyism was not just a philosophy—it was a movement that connected the struggles of Africans on the continent with those in the diaspora.

Caribbean and American Influence on African Liberation: Many African revolutionaries were inspired by Pan-Africanist movements in the Caribbean and the U.S. Leaders like Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), and Nkrumah (Ghana) studied abroad, where they encountered Garvey’s teachings and applied them to their home struggles.

UNIA’s Impact on Black Consciousness: Garvey’s UNIA spread ideas of African nationalism, economic self-reliance, and military resistance. His vision of a self-sufficient Africa influenced independence leaders and fueled anti-colonial activism.

The Back-to-Africa Movement: While most Africans did not physically return to Africa, Garvey’s message inspired a psychological return—one that led to a reconnection with African identity, history, and the fight for sovereignty.

The African resistance movements were never isolated struggles. They were part of a global Black awakening, demanding not just freedom from colonial rule but also a reclamation of dignity and economic power.

4. Lessons from Garvey for Today’s Africa

Garvey’s vision remains as relevant today as it was during colonial rule. As Africa continues to navigate neocolonialism—economic exploitation, foreign influence, and internal divisions—the core Garveyite principles remain essential:

Economic Self-Reliance: True liberation means controlling resources, industries, and trade. Modern African nations must prioritize building strong, independent economies rather than relying on foreign aid.

Pan-African Unity: Colonial borders divided Africa, but unity remains the key to true independence. Regional alliances like the African Union must embrace Garvey’s radical call for continental solidarity.

Cultural Reclamation: Garvey understood that mental liberation was as crucial as political liberation. Africa must continue reclaiming its history, languages, and cultural pride to fully escape the psychological chains of colonialism.

Conclusion: The Struggle Continues

Garvey’s cry—"Up, you mighty race, accomplish what you will!"—remains a guiding light. The resistance against colonialism was never just about defeating European powers; it was about the restoration of African sovereignty, pride, and unity. The struggle continues today in economic policies, cultural narratives, and the fight against neo-colonial forces.

Garveyite thought reminds us that true liberation is not just about removing the colonizer’s physical presence—it’s about ensuring that Africa stands tall, self-sufficient, and united in its destiny.

Africa for the Africans—Yesterday, Today, and Forever!

#african resistance#black resistance#black history#black people#blacktumblr#black#black tumblr#pan africanism#black conscious#africa#black empowering#black power#blog#marcus garvey#Garveyism#Garveyite#decolonization#black liberation#african history

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

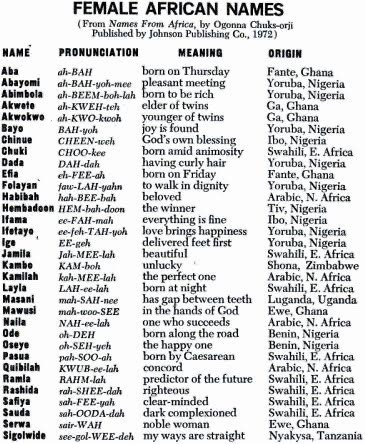

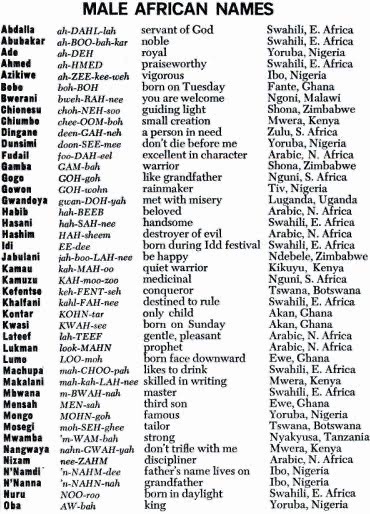

Title: "The Significance and Diversity of African Names"

Introduction

African names are a reflection of the continent's incredible diversity, culture, history, and traditions. With over 2,000 distinct languages spoken and a multitude of ethnic groups, Africa is a treasure trove of names that carry deep meanings and unique stories. In this article, we'll explore the rich tapestry of African names, their significance, and the cultural diversity they represent.

The Importance of Names

Names hold a special place in African societies. They are more than mere labels; they encapsulate a person's identity, heritage, and often convey messages of hope, aspiration, and blessings. African names are deeply rooted in the belief that a name can shape a person's destiny and character.

Linguistic Diversity

Africa's linguistic diversity is astounding, with thousands of languages spoken across the continent. Each language group has its distinct naming traditions, resulting in a vast array of names. For example, in West Africa, Akan names such as "Kwame" (born on a Saturday) and "Kofi" (born on a Friday) are common, while in East Africa, Swahili names like "Amina" (trustworthy) and "Nia" (purpose) are prevalent.

Meanings and Symbolism

African names are rich in meaning and symbolism, often reflecting the circumstances of a child's birth, their family history, or the aspirations of their parents. Names can signify virtues like courage, strength, and wisdom or convey hopes for a prosperous and fulfilling life.

Family and Heritage

In many African cultures, names are chosen to honor ancestors, celebrate cultural heritage, or connect the child to their roots. This practice ensures that generations remain connected to their family's history and traditions. For example, the Igbo people of Nigeria often use "Ngozi" (blessing) to convey the hope for a blessed life..

Naming Ceremonies

Naming ceremonies are significant events in many African communities. These ceremonies are joyous occasions where family and friends gather to celebrate the birth of a child and bestow a name. The rituals and customs associated with these ceremonies vary widely, showcasing the diversity of African naming traditions.

Modern Influences

In today's globalized world, African names are not confined to the continent. Many people of African descent living outside Africa proudly bear African names, celebrating their cultural heritage and contributing to the global recognition of the beauty and significance of these names.

Conclusion

African names are a testament to the continent's diversity, culture, and history. They carry profound meanings, connect individuals to their heritage, and celebrate virtues and aspirations. As we embrace and appreciate the beauty of African names, we also acknowledge the importance of preserving and passing on these cultural treasures to future generations, ensuring that the rich tapestry of African identity remains vibrant and thriving.

1. **Kwame (Akan, Ghana):** A male name meaning "born on a Saturday."

2. **Ngozi (Igbo, Nigeria):** A unisex name meaning "blessing" or "good fortune."

3. **Lulendo (Lingala, Congo):** A male name meaning "patient" or "tolerant."

4. **Amina (Swahili, East Africa):** A female name meaning "trustworthy" or "faithful."

5. **Kwesi (Akan, Ghana):** A male name meaning "born on a Sunday."

6. **Nia (Swahili, East Africa):** A unisex name meaning "purpose" or "intention."

7. **Chinwe (Igbo, Nigeria):** A female name meaning "God owns" or "God's own."

8. **Mandla (Zulu, South Africa):** A male name meaning "strength" or "power."

9. **Fatoumata (Wolof, Senegal):** A female name meaning "the great woman."

10. **Kofi (Akan, Ghana):** A male name meaning "born on a Friday."

These are just a few examples, and there are countless other African names with unique meanings and significance. It's essential to remember that Africa is incredibly diverse, and each region and ethnic group has its own naming traditions and languages, contributing to the rich tapestry of African names.

The most popular African names among Black Americans can vary widely based on individual preferences, family traditions, and regional influences. Many Black Americans choose names that connect them to their African heritage and celebrate their cultural roots. Here are a few African names that have been embraced by some Black Americans:

1. **Malik:** This name has Arabic and African origins and means "king" or "ruler."

2. **Amina:** A name of Swahili origin, meaning "trustworthy" or "faithful."

3. **Kwame:** Derived from Akan culture, it means "born on a Saturday."

4. **Nia:** A Swahili name representing "purpose" or "intention."

5. **Imani:** Of Swahili origin, it means "faith" or "belief."

6. **Jamal:** This name has Arabic and African roots and means "handsome."

7. **Ade:** A Yoruba name meaning "crown" or "royalty."

8. **Zuri:** Of Swahili origin, it means "beautiful."

9. **Sekou:** Derived from West African languages, it means "fighter" or "warrior."

10. **Nala:** This name is of African origin and means "gift."

It's important to note that while these names have African origins, their popularity among Black Americans can vary by region and individual choice. Additionally, some Black Americans choose to create unique or hybrid names that blend African and American influences, reflecting their personal and cultural identities. The naming choices among Black Americans are diverse and reflect the rich tapestry of their heritage and experiences.

African Languages: A Tapestry of Diversity and Culture"

Introduction

Africa is a continent known for its stunning natural landscapes, diverse wildlife, and rich cultural heritage. Among its many treasures, the continent boasts an astonishing linguistic diversity that is often overlooked. In this article, we delve into the fascinating world of African languages, exploring their diversity, cultural significance, and the challenges they face in a rapidly changing world.

The Linguistic Kaleidoscope

Africa is home to over 2,000 distinct languages, making it one of the most linguistically diverse regions on the planet. These languages belong to several different language families, including Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Congo, and Khoisan, each with its unique characteristics.

Niger-Congo Family: The vast majority of African languages, including Swahili, Yoruba, Zulu, and Kikuyu, belong to the Niger-Congo language family. This family stretches across West, Central, and Southern Africa, reflecting the continent's linguistic richness.

Afroasiatic Languages: Arabic, a member of the Afroasiatic family, has a significant presence in North Africa, while other Afroasiatic languages like Amharic are spoken in the Horn of Africa.

Nilo-Saharan Languages: Found in parts of East and North Central Africa, Nilo-Saharan languages include Dinka, Kanuri, and Nubian.

Khoisan Languages: These languages, characterized by their unique click consonants, are primarily spoken by indigenous groups in Southern Africa, such as the San and Khoi people.

Cultural Significance

African languages are not just tools of communication; they are repositories of cultural heritage and identity. They carry the history, stories, and traditions of their speakers. Each language is a key to unlocking the rich tapestry of African cultures, from oral storytelling and folklore to religious rituals and traditional medicine

Preserving Cultural Diversity

Despite their cultural importance, many African languages are endangered. The rise of global languages like English, French, and Portuguese, often due to colonial legacies, has led to the decline of indigenous languages. To address this, efforts are being made to document, preserve, and revitalize endangered African languages through education, community initiatives, and technology.

A Language of Unity

In some regions, African languages are a means of fostering unity. For example, Swahili, a Bantu language with Arabic influences, serves as a lingua franca in East Africa, promoting communication and cooperation among diverse ethnic groups.

Challenges and Opportunities

While African languages face challenges in an increasingly interconnected world, they also offer unique opportunities. Embracing linguistic diversity can strengthen cultural identities, promote inclusive education, and drive economic growth through multilingualism.

Conclusion

African languages are an integral part of the continent's rich heritage and cultural tapestry. They represent the diversity of Africa's peoples and their traditions. While challenges exist, there is hope that efforts to preserve and celebrate these languages will ensure that they continue to thrive, enriching the world with their unique beauty and significance. In an increasingly globalized world, Africa's linguistic diversity is a testament to the resilience and vibrancy of its cultures.

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture#black community#language

758 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hunter x Hunter: Assorted Troupe speculations

its just funny headcanons i have in groups of 12 bcs if i make an individual post for each of these i would flood the tag like no one's business.

Table of Contents:

cooking

how ended up in meteor city

drivers license

irl ethnicity equivalents (hc)

tea coffee or beer

adding pagebreak bcs i know this gon be long as shit-

Can they cook?

Nobunaga: he can make a mean onigiri. maybe fried fish if he wants but nah. dont let him cook he will fuck it up somehow.

Feitan: yeah he cooks but only what he likes. better be prepared to eat spicy if you eating his food.

Machi: also really good with riceballs and sushi. doesn't put in a lot of effort. makes a gnarly miso soup tho

Phinks: no. if he could live off of protein shakes he would.

Shalnark: do not let this man touch the stove.

Franklin: yeah but its basic. makes some nice pancakes.

Shizuku: no. do not let her near the knives.

Paku: yes. girl chefs up some nice ass food. and its the fancy shit too bcs i know shes loaded.

Bono: yes. usually in small portions though

Uvo: bbq master.

Kortopi: sandwich

Chrollo: duh. he's good at everything for apparently no reason.

How did they get to Meteor City?

Nobunaga: Born in. Forfeited to the care centers.

Feitan: Abandoned at an older age. If i had to guess close to 4 or 5

Machi: Abandoned as an infant. Ran away from care center.

Phinks: Born. parents taken by illness.

Shalnark: Abandoned. *looks at kurta shal headcanon* i mean what-

Franklin: Born. Forfeited to the care centers

Shizuku: Born, parented by the church.

Paku: Abandoned as an infant. Found in the wasteland

Bono: Exiled. Born and raised outside of the city

Uvo: Abandoned at young age. (2-3)

Kortopi: Rescued from the nearby river. Scrapper child.

Chrollo: Born, abandoned by meteorite parents.

Can they legally drive?

Nobunaga: yes

Feitan: no

Machi: no. she can drive just not legally.

Phinks: no

Shalnark: yes, but it was a mistake.

Franklin: no. boy too big ;-;

Shizuku: yes. and she's responsible.

Paku: yes. she can go 0-60 in any vehicle, just watch-

Bono: no

Uvo: no, boy extra too big

Kortopi: no, boy too small

Chrollo: yes, but only if no one else wants to.

Ethnicity headcanons

Nobunaga: Japanese

Feitan: Chinese

Machi: Japanese/?? (still doing research on the origins of Komacine)

Phinks: Italian/Egyptian

Shalnark: German

Franklin: French/Malaysian (also still digging)

Shizuku: Japanese

Pakunoda: Russian

Bonolenov: Maori/African (Zulu)

Uvo: Spanish/Kenyan

Kortopi: Indian

Chrollo: Greek/Korean (alt. Japanese bcs i cant make up my mind)

Tea, Coffee, or Beer

Nobu: Beer

Feitan: Tea

Machi: Tea

Phinks: Beer

Shal: Coffee

Franklin: Beer

Shizuku: Beer

Paku: Coffee

Bono: Tea

Uvo: Beer

Kortopi: All. Caffeine is caffeine

Chrollo: Tea

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

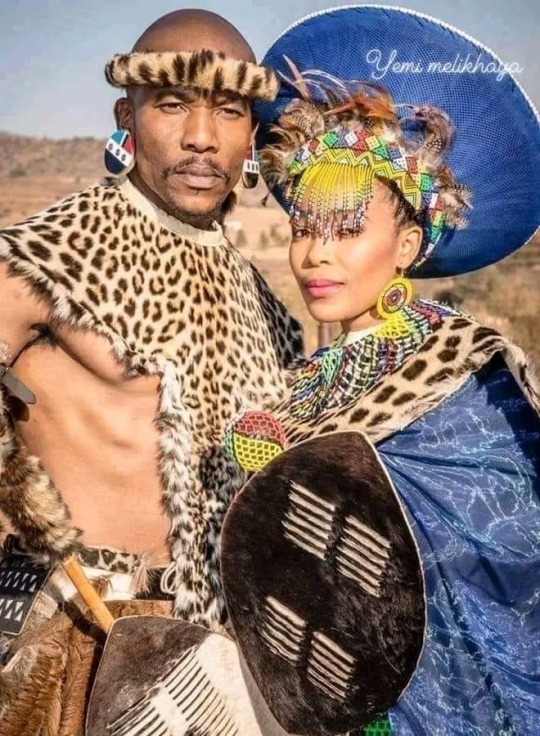

The word Zulu means "Sky" and IsiZulu is South Africa's 🇿🇦 most widely spoken official language. Zulu people refer to themselves as 'the people of the heavens' and they are the largest ethnic group of South Africa, with an estimated 11 million Zulu residents in KwaZulu-Natal. The largest urban concentration of Zulu people is in the Gauteng Province, and in the corridor of Pietermaritzburg and Durban. The largest rural concentration of Zulu people is in Kwa-Zulu Natal. In the 19th century, they merged into a great kingdom under the leadership of Shaka Zulu.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 LARGEST Ethnic Groups in Africa🌍

Welcome to our channel! In this fascinating video, we dive deep into the rich tapestry of Africa, exploring the top 10 largest ethnic groups on the continent. Join us on a virtual journey as we unveil the unique cultures, traditions, and geographical locations of these vibrant communities.

From the Berbers of North Africa to the Zulu people of Southern Africa, we'll shed light on the diverse heritage that makes Africa such a culturally abundant continent. Learn about the history, languages, arts, and rituals that define each group, and gain a deeper understanding of their contributions to African society.

Our exploration will take us to remote villages, bustling cities, and breathtaking landscapes, showcasing the breathtaking beauty that Africa has to offer. Immerse yourself in the vibrant colors, mesmerizing dances, soulful music, and mouthwatering cuisine that form an integral part of each ethnic group's identity.

Whether you're a history enthusiast, a passionate traveler looking for inspiration, or simply curious about the world we live in, this video is for you. Join us as we celebrate the rich tapestry of African cultures and encourage you to embrace diversity and promote unity.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it's very interesting that people will say "the French don't exist" but would be furious if someone said "the Zulus don't exist ".

Apparently ethnic groups only exist if they are non white.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the days before South Africa’s May 29 election, there was a euphoric atmosphere in parts of the cosmopolitan but largely Zulu port city of Durban. People who would usually pass each other anonymously could be overheard telling each other, “We are going to fix the country!” There was, though, an ugly underside to this, with current President Cyril Ramaphosa, who is from the smaller Venda ethnic group, often dismissed in vulgar ethnic terms.

The African National Congress (ANC), after 30 years of comfortable rule, took a heavy blow in this election. It secured only 40.2 percent of the vote nationally and took its hardest hit in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, where Durban is located. There, it came in far behind the newly formed uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) party—whose figurehead is former President Jacob Zuma. MK finished first with almost 46 percent of votes for the national assembly, taking a large number of votes from the ANC—which won around 17 percent—and many from the Zulu-nationalist Inkatha Freedom Party.

KwaZulu-Natal is South Africa’s second-most populous province—and it is notorious for political violence—including open armed battles fought through the late 1980s and early 1990s, assassinations, and major riots in July 2021.

The electoral success of Zuma’s new party in the recent election has raised fears of further violence.

Organized around the charisma of Zuma, who was the staggeringly corrupt president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018, the MK party takes its name, meaning “spear of the nation,” from the armed wing of the ANC formed by Nelson Mandela and others in 1961. The party lays claim to that history and has adopted a militaristic posture.

Apartheid was, of course, not brought down by that army, which was, in military terms, a failed project. Before Western opinion turned at the end of the Cold War, apartheid was rendered nonviable by the mass democratic politics that began with a series of strikes in Durban in 1973, a popular movement that does not appear in Zuma’s militaristic misrepresentation of political history.

MK endorses an extreme version of the authoritarian populism that has surged in elections around the world. It is best described as ethnically inflected nationalism; while the party has an anticolonial dimension in so far as it seeks to build a counter-elite, it is also socially predatory and deeply conservative on social issues. Zuma has suggested doing away with same-sex marriage, which has been legal in South Africa since 2006; elevating aristocratic tribal authorities over elected representatives; holding a referendum on the death penalty; hiring more police officers; and introducing conscription.

Like other authoritarian populist parties in South Africa and elsewhere, Zuma’s party also takes a hard-right line on immigration. This is a matter of serious concern in South Africa, where African and Asian migrants are often targeted by the state and, periodically, by violent mobs.

MK also has a clear ethnic dimension. This is in sharp contrast to the ANC, which was founded in 1912 with an explicit commitment to build a national sense of African identity that eschewed the politicization of ethnic identities. It remains an ethnically diverse organization led by a member of an ethnic minority group.

Like figures such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban, MK is also enthusiastically pro-Putin. Some MK supporters have been seen wearing T-shirts with side-by-side images of Zuma and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

But unlike forms of right-wing populism elsewhere, MK also promises economic inclusion in a country where impoverishment and inequality are rampant, along with the effective provision of basic services. It proposes nationalizing banks, mines, and insurance companies; expropriating land and placing it under the control of the state and traditional authorities; and providing free education and full employment.

Due to this platform, newspapers outside South Africa have sometimes referred to Zuma’s party as being “far left.” But the left in South Africa has not rallied in support of MK’s proposals for expropriation and nationalization—largely because Zuma’s record during his nine years as president was dire in terms of creating jobs; providing basic services, decent health care, education, and public housing; and achieving long-promised land reform.

Indeed, corruption during Zuma’s presidency did massive damage to the state, its institutions, and its publicly owned companies and was so extreme that a single family took in just under 50 billion rand (then around $3.2 billion) from public budgets in what came to be known as “state capture.” Zuma’s presidency was also marked by a sharp increase in state repression, including the massacre of 34 striking miners by South African police in 2012 and frequent assassinations of grassroots activists.

A number of commentators across the political spectrum have reduced Zuma’s popularity and electoral success in KwaZulu-Natal to “tribalism,” sometimes with the implication that atavistic forces are at play. The recourse to this deeply colonial idea of the “tribe” is unfortunate. But the ethnic element in Zuma’s politics cannot be overlooked either.

Zuma has sought to stoke ethnic sentiment since he was tried for rape in 2006, when, along with chanting, “Burn the bitch,” in reference to his accuser, some of his supporters wore T-shirts with the slogan “100% Zuluboy.” In the lead-up to the recent election, it was common to hear people in Durban speak of the need to achieve the unity of the Zulu people.

KwaZulu-Natal has a long history of violent ethnic mobilization. Mpondo people from the neighboring Eastern Cape province have been sporadically attacked and driven from their homes for more than a century, including when ethnic sentiment escalated as Zuma ascended to the presidency in 2009.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was open war between Inkatha, then a conservative Zulu-nationalist organization backed by the apartheid state, and the United Democratic Front, a popular anti-apartheid organization that allied itself with the ANC in exile. It is estimated that around 20,000 people were killed between the late 1980s and early 1990s. The apartheid state saw Inkatha as a conservative ally against the Soviet-linked ANC and an ally equally opposed to the ANC’s vision of a unitary democratic state.

The war came to an end when, in secret negotiations between the last apartheid president, F.W. de Klerk, and Inkatha leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi on the eve of the first democratic election, huge concessions were made to Inkatha, most notably via the massive transfer of land in KwaZulu-Natal—around 11,000 square miles, almost the size of Belgium—to the Zulu monarchy. This boosted the power of what is termed “traditional authority” over democratic authority, as people living on the land must pay rent to a trust headed by the Zulu king and are governed by customary law administered by traditional leaders.

The end of the war did not bring peace, though. The province swiftly became notorious for political assassinations within the ANC, between the ANC and other parties, and against grassroots activists. Many hundreds of people have been killed. The problem of assassinations was never seriously dealt with in the province and, as a result, has been steadily making its way into other parts of the country.

In the latter years of Zuma’s presidency, he sought to protect himself against mass outrage at brazen corruption by cynically spinning his government’s kleptocracy as “radical economic transformation.” This was taken up outside of the state by armed so-called business forums that shook down established businesses at gun point and by local party gangsters who appropriated public land for private profit. The capacity for violence developed in this milieu includes access to professional assassins and, in some cases, local militias.

In July 2021, when Zuma was briefly jailed for being in contempt of court, KwaZulu-Natal was ripped apart by riots in which 354 people were killed. The riots were sparked by a breakdown in the social order as supporters of Zuma, some dressed in military fatigues, openly attacked migrants from elsewhere in Africa in downtown Durban while the police stood down. There were also more covert attacks on trucks on the main road to Johannesburg, and many were left burnt. Again the police stood down.

The riots began with the mass appropriation of food in a carnival atmosphere. In the main, there was not much sense that this was a political event, and many participants were clear that they were not motivated by support for Zuma. But the riots soon took on a more ominous tone, and infrastructure was systematically destroyed by groups of armed men acting with military precision. Zuma’s daughter Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla celebrated the destruction on social media.

Now that the country is suspended between an election result that fundamentally changes its politics and the outcomes of the ongoing high-stakes negotiations to form national and provincial governments, the atmosphere in Durban is more febrile than euphoric.

False claims are being pushed through social media with a startling velocity, with Zuma-Sambudla taking a leading role in the promotion of conspiracy theories. There has been a particular focus, repeated by Zuma in various public statements, on the Trumpian move of declaring, without evidence, that the elections were rigged. The general view is that Zuma and his supporters are making this claim to set the stage for violence, although it is not quite clear what their intentions are.

It is common to hear people say that when the new provincial government comes into power, migrants will be “dealt with” and ethnic minorities will “know their place.” It is not uncommon to hear talk of secession, of an independent Zulu kingdom. There are widespread fears of coming violence, something that a number of grassroots activists say is inevitable. Mqapheli Bonono, one of the most prominent grassroots activists in Durban, said: “There will definitely be violence. We don’t know when or where, but for sure it’s coming.”

Migrants have already been threatened and intimidated. Last Wednesday, an MK organizer was gunned down in Durban. Although there is not yet any evidence of a specific motive, it is being reported by some media as a political killing. It is widely assumed that this is the beginning of an internal struggle for positions and power within MK. Some ethnic minorities fear that they may have to move out of the province. Some have returned to rural family homes outside the province while they wait to see how things play out.

Ramaphosa wishes to establish a national unity government so the ANC can continue to govern the country. It is not yet clear if this will work or if MK will participate in such an arrangement. In KwaZulu-Natal, it is possible that a deal between other parties could keep MK in opposition despite it winning the largest share of the vote. If MK is not part of the deal struck to form a national government, tensions will inevitably escalate. This will be dramatically compounded if the party is kept out of government in KwaZulu-Natal by an alliance of other parties.

If MK does form a government in KwaZulu-Natal, the country will have its second-most populous province governed by a political force directly opposed not just to the national government but to the principles and legal foundations on which the country was founded.

The militaristic posture of Zuma’s party escalates fears of violence, and Zuma himself often makes implicit threats of violence via dog whistles. Speaking in English, he has warned that he should not be “provoked.” Speaking in Zulu, he has said: “Abasazi singo bani” (They don’t know who we are).

The idiomatic meaning here is clear, but, in literal terms, South Africans know exactly who Zuma and his party are.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

So my ancestrydna updated (yes I know I shouldn't have given my dna to a private company etc but I had no other way of finding out my actual ethnicity otherwise thank u slavery) and they have these regional markers in some of them

I thought you had to have a sizable amount of dna from one region to get region specific data but it turns out you don't. They can just tell you what specific groups the people in the panels come from , which is useful for people like me and my 13 ancestral regions bc the amounts are quite small when you dissect them individually

Also when you're dealing with a place like Africa where the political borders are v modern and therefore sort of arbitrary, it's pretty handy. Especially when they cut through territories that have been occupied by certain groups for however long

Anyway tldr today I found out I quite likely have Zulu ancestry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

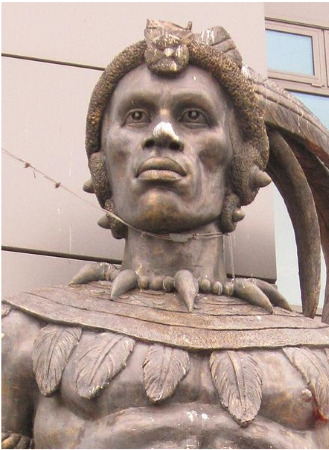

Shaka Zulu: The Influential Reign and Military Reforms of King Shaka kaSenzangakhona

Shaka kaSenzangakhona, also known as Shaka Zulu, was a remarkable and influential figure who left an indelible mark on the history of the Zulu Kingdom. Born around 1787, Shaka ascended to the throne in 1816 and ruled until 1828. During his reign, he implemented sweeping reforms that transformed the Zulu military into a formidable force, solidifying his position as one of the most influential…

View On WordPress

#African History#history#Shaka kaSenzangakhona#Shaka Zulu#Sigidi kaSenzangakhona#South Africa history#Zulu ethnic group#Zulu History

1 note

·

View note

Text

50+ African goddess names and meanings - Tuko.co.ke

Most communities from around the world believed in various goddesses as their keeper and fate determiners. Most of the goddesses from the early years continue to inspire generations for their irreplaceable roles. Notably, there were deities in charge of every sect of life, contrary to the current monotheism system of belief.

Who are the African goddesses? Ancient African thrived under a robust faith system before westernization, among the most deity-centred parts of life, including love, beauty, fire, rain, and harvest. Goddesses were incredibly respectable, with each bearing a specific name depending on the primary roles. Here are the African mythology goddesses, their names, and meanings.

African goddess of love and beauty

Who is the African goddess of love? Oshun is the African goddess of love and sweet waters. She is a specific deity among the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Oshun is by far the most famous African goddess of beauty.

Creator, sun, moon, stars, or nature female deities

Gleti - She is the moon goddess revered by all in the Dahomey kingdom, particularly the Fon people, Benin. She is the mother of all-stars.

Nana Buluku - The goddess is a supreme creator and mother to the sun spirit Lisa, moon spirit Mawu, and the entire universe, in Dahomey mythology, West Africa. She is also called Nana Buku or Nana Buruku.

Aberewa - Goddess of earth among the Ashanti in Ghana

Aja - Goddess of the forest among the Yoruba

Mawu-Lisa - Creator goddess, Fon people of Benin

Amma - Creator goddess in Burkina Faso and Mali, Dogon people

Asaase - Afua the earth goddess in Ghana among the Ashanti

Faro - Creator goddess in Mali, Bambara people

Kitaka - Earth goddess in Uganda, Baganda people

Nkwa - Creator goddess in Gabon, Fang people

Woyengi - Creator goddess among the Ijo in Nigeria

African goddess of fire

Who is the African god of fire? Africans believed that different goddesses had authorities over the fire.

Oya- Wears a lot of red, is the Yoruba warrior-goddess of fire. She is also the goddess of the Niger river, magic, wind, fertility, and other chaotic, electrifying phenomena.

Morimi- Goddess of fire among the Yoruba

African goddess of fertility and harvest

Asase Ya - She is also famous as Asaase Afua, Asaase Yaa, or Asase Yaa among the Bono people of the Akan ethnic group in Ghana and Guinea Coast. She is the goddess of fertility on the earth, bearing other divine titles such as Aberewaa or Mother Earth. She is second to Nyame (the Creator) in power and reverence.

Mboya - Fertility and motherhood deity in Congo

Mbaba Mwana Waresa - Fertility goddess in South Africa among the Zulu

Ala (odinani) - The Igbo people esteem Ala being the goddess of morality, creativity, fertility, and the earth as a whole. She is the most important deity in the Igbo mythology.

Ahia Njoku - She is a famous goddess among the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. The community believes she is responsible for yam, a special treat among the locals.

Abuk - deity of women and gardens in Sudan

Mwambwa - Goddess of desire and lust in Namibia

Inkosazana - Goddess of agriculture in South Africa, Zulu people

African rain, river, sea, and water goddesses

Mami Wata - The goddess is a well-known water spirit displaying male characters at times. Residents of West, Central Africa, and Southern Africa uphold her goddess powers as supreme.

Oba - Obba was the first wife of Shango, the third king of the Oyo Empire and the Yoruba Undergod of thunder and lightning. This African name refers to the river goddess in African mythology. She is the breath of divinity when it comes to the gods of rivers.

Bunzi - Kongo mythology believes in Bunzi as the goddess of the rain. She is the daughter of her great mother, Mboze. She is a coloured serpent well pleased with those who bring their plentiful harvest in her worship

Abena - River goddess associated with wealth symbols of brass and gold

Mamlambo - Goddess of rivers among the Zulu of South Africa

Obba - Goddess of Obba River in Nigeria

Yemaja - Goddess of Ogun River, Nigeria

Olokun - The African goddess of the sea in Nigeria

Yemaya - Goddess of the living ocean

Modjaji - Goddess of rain among the Balodedu people of South Africa

Majaji - Goddess of rain in South Africa, Lovedu people

Mbaba Mwana Waresa - Goddess of the rainbow, South Africa, Zulu people

Egyptian goddess names

Isis - She is the commonest of all Egyptian goddess names, a respectable deity of the Egyptian pantheon. Isis is the African goddess of wisdom known for her cleverness that exceeds that of a million gods. The image of the goddess Isis suckling her son Horus was a powerful symbol of rebirth that was carried into the Ptolemaic period and later transferred to Rome.

Sekhmet- Fire-breather goddess among the Egyptians

Amunet – goddess of healing and wisdom

Ma'at – goddess who personified truth, justice, and order

Anat - goddess of fertility, war, love, and sexuality

Tefnut – goddess of moisture

Anta -mother goddess

Anqet - goddess of fertility and the Nile River cataract

Anuke – earliest goddess of war

Arensnuphis – sacred companion goddess to Isis

Pakhet - A hunting goddess taking the form of a lioness

Nebethetepet- Her name means "Lady of the Offerings" or "Satisfied Lady"

Tawaret- She is a hippopotamus with the breasts and belly of a pregnant woman, the paws of a lion, and a crocodile tail hanging behind her head. Often she holds a protection sign beneath her paws, but in this case it is absent.

Hathor- associated with afterlife, music and dance, and sexuality and motherhood

Nepit - Goddess of grain

Ethiopian goddess names

Most names of contemporary Ethiopian deities come from the Quran and the Bible. However, ancient inhabitants worshipped:

Aso: goddess of justice - She is coincidentally queen of the Ethiopian people.

Atete: goddess of fertility - Christian cult of the Virgin Mary among the Oromo People

More African goddess names and their meanings

Gbadu -Goddess of fate in Benin, Fon people

Age-Fon - Goddess of hunters, Benin, Dahomey Empire

Achimi - Buffalo goddess, Algeria

Ancient deities share unique names based on their supernatural powers and influence in subject communities. Learning about African goddess names and meanings is useful for child naming. Furthermore, knowing these names helps in explaining ancient

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

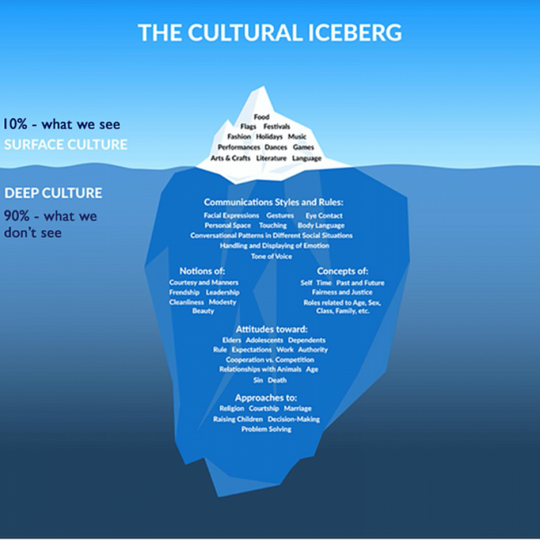

Reflecting on cultural humility

Cultural humility is defined as the “ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) about aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the person.” (Waters & Asbill, 2013). It’s a continuous journey of examining oneself and being open to learning from others. It entails approaching interactions with others with respect for their beliefs, traditions, and values (What is cultural humility? The Basics: Equity and Inclusion, n.d.). The five aspects of cultural humility are openness, self-awareness, egolessness, supportive interactions, self-reflection, and critique. This blog will outline the significance of cultural humility and reflect on the intervention planned by a student therapist for clients concerning cultural humility.

“The portions we see of human beings is very small, their forms and faces, voices and words (but) beyond these, like an immense dark continent, lies all that has made them.” Freya Star

Cultural humility plays a crucial role in occupational therapy by ensuring that interventions are effective and respectful of each patient's unique context, preferences, and cultural background. Before beginning the interview, obtaining informed consent from the client signifies a commitment to respecting their autonomy and rights. Cultural humility also empowers therapists to identify and address power imbalances (Anderson, 2022). For example, patients believe that they must accept the health care recommendations without raising their opinions; this is not true. Cultural humility involves understanding the impact of culture on health beliefs, acknowledging power imbalances between therapist and client, and working together with clients to create interventions that are culturally sensitive and appropriate. In occupational therapy, cultural humility also has implications for our personal lives. Through approaching interactions with people. Therefore, this can improve our relationships by fostering better empathy, comprehension, and connection. Culture has significant implications for OT intervention because it determines perceptions of health, illness, and occupation. Reberg, (2019). To interact with a client efficiently and understand their daily activities, one must be aware of their cultural background.

I was exposed to clients from the same ethnic group, which is black, from Zulu culture, and we share the same culture. It was a positive experience as we were able to have clear communication and acknowledge our culture, as we come from different backgrounds and the roots of the culture might be different. However, even though we came from different backgrounds, when I was planning intervention sessions with the CVA patient, which included dressing and bathing activities, I first obtained a consent form from her on the previous day of our intervention to ensure that I was adhering to the fundamentals of cultural sensitivity. Planning for intervention for the following day, the client was expected to do dressings of the upper and lower limbs. this was done to teach the client new techniques of dressing, such as beginning with the affected limb when dressing herself. So, I was planning to use the pants for dressing the lower limb as she doesn’t have personal clothes at the facility, and at the facility, they don’t have skirts; they only have those dresses that are easy to wear. So I asked the patient if that was okay if she dressed herself using the pants so that I wouldn’t perform an activity that was against her culture. The patient agreed to do so. This was also applied to my second patient, as before performing the dressing of the upper limb activity, I began with consent.

Then, on the other intervention with CVA, the patient asked me to teach her bathing activity, as she said she wanted to learn to bathe herself. After every intervention, the client was asked about the activity and the plan for the next session by asking her what activity she faced difficulty with and wanted to learn to perform. So, the client says she wants to bathe herself, so we plan to perform the bathing activity with the patient. On the previous day of bathing activity, I first obtained consent from the patient in order to perform the session. This was done because some old people from Zulu culture find it disrespectful if a young person looks at them naked. The patient didn’t have any problem with that.

Fieldwork is a good learning experience, as it prepares us for the future by teaching us holistic patient care. I learned that cultural humility is very important in occupational therapy, even if you share the same culture. As I’m Zulu culture, I feel like our backgrounds with the patient and I are differences. I was working with the old female. I found it difficult to work with her as I had to make eye contact when we were communicating or performing a session with the patient. When the client was feeding herself, I needed to do observation, look at the client while naked (when bathing and dressing),provide commands to the patient in terms of what she must do, and also call her by her name. This was against my Zulu culture, as we are not allowed to look at old people when they are naked or eating and also call them by their names; they want us to call them Aunt if they are female and Uncle if they are male. It forms part of my disrespect as a young female.

This situation enriched my knowledge in terms of intervention. I went back and did research, and I remembered that as an occupational therapy student, I will be working with people and teaching them how to bathe and dress themselves. I think I need to have more knowledge on how to respect the work without violating your culture. As I continue my journey as an occupational therapist, I have learned that cultural humility is important, and I need to consider it when planning interventions so that they can be client-centered. I have to ask my colleagues in terms of how to handle the challenge that I faced in terms of cultural barriers while continuing with research. I believe that the feedback that I will receive will be helpful. I am aware of the challenges I will face along the way in occupational therapy. I am willing to learn so that my patients will always get culturally sensitive and appropriate care. Cultural humility is important as it can transform the way we interact with others in both our personal and professional lives. Cultural humility can also help us build a good rapport with our patients, which will allow us to get to know them better and provide an effective intervention for them.

In conclusion, cultural humility stands as a cornerstone in the practice of occupational therapy, facilitating not only effective interventions but also fostering genuine connections with patients. Through a journey of self-reflection, openness, and continuous learning, therapists can navigate diverse cultural landscapes with sensitivity and respect. As demonstrated in the experiences shared, cultural humility is not only about recognizing differences but also about actively seeking understanding and adapting interventions to honor individual backgrounds and preferences. By embracing cultural humility, therapists can ensure that their practice is truly client-centered, enhancing the quality of care and nurturing meaningful therapeutic relationships.

references

Waters, A., & Asbill, L. (2013, August). Reflections on cultural humility. CYF News. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/newsletter/2013/08/cultural-humility.aspx

What is Cultural Humility? The Basics | Equity and Inclusion. (n.d.). Inclusion.uoregon.edu. https://inclusion.uoregon.edu/what-cultural-humility-basics#:~:text=%E2%80%9CCultural%20humility%20involves%20an%20ongoing

Anderson, S. H. (2022). Cultivating Cultural Humility in Occupational Therapy through Experiential Strategies and Modeling. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1962

Reberg, J. (2019). The Importance of Cultural Humility in Occupational Therapy. Review of The Importance of Cultural Humility in Occupational Therapy. Https://Www.google.com/Url?Sa=I&Url=Https%3A%2F%2Fscholarworks.wmich.edu%2Fcgi%2Fviewcontent.cgi%3Farticle%3D4185%26context%3Dhonors_theses&Psig=AOvVaw0LFVT5cn4tQhH3d-PHMRlW&Ust=1714154018398000&Source=Images&Cd=Vfe&Opi=89978449&Ved=0CAUQn5wMahcKEwiwj_On992FAxUAAAAAHQAAAAAQCA.

University of Oregon (2021). What is Cultural Humility? The Basics. [online] Equity and Inclusion. Available at: https://inclusion.uoregon.edu/what-cultural-humility-basics.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round three: Shongololo vs

עם, am

(poll at the end)

Shongololo (siSwati)

[ʃonɡolôːlo]

Translation: Millipede

siSwati is an Atlantic-Congo language belonging to the Bantu branch, which covers most of sub-Saharan Africa. It is spoken by 960 000 people in Eswatini, where it is the national language, but by 4,7 million people in total, half of whom speak it as a second language. Most of them live in South Africa. The prefix si- in siSwati indicates the noun class, shortly explained as a gender system but with more (up to 20) classes, less arbitrary categorization and different but paired classes for singular and plural. From what I’ve found, si- is the prefix for class 7, indicating body parts or pairs in siSwati. From what I remember from a lecture, some Bantu languages use the same class to signify languages, which gives related names such as isiZulu and kinyaRwanda.

Motivation: I love how it feels when saying it! It also manages to seem both long and round, just like the animal itself. <3

Note: I found evidence of shongololo being used in siSwati, but the IPA transcription is taken from Zulu (ishongololo, in which the i- signifies noun class), which is closely related to siSwati. I thought it should have the prefix in- for objects and animals but couldn’t find evidence of that word ever being used, so probably not. Someone who knows siSwati, please tell me how it all works.

עם, am (Hebrew)

[am]

Translation: Tends to be translated as 'people (as a group like 'the jewish people')' but also its... so much stronger than that. It's like... group? Tribe? But like. Bigger. Not necessarily in size but in... feeling i guess? It's stronger.

Hebrew is an Afro-Asiatic language belonging to the Semitic branch and is the Jewish language in which the Tanakh was written down, originating in today’s Israel. Even after Hebrew stopped being spoken by Jews, it lived on as a literary medium and religious language. Using a modern version of Hebrew as a daily language was promoted principally by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda in the late 19th century. Reviving efforts went well and Hebrew is now the official language of Israel, where it's spoken by 8 million people. 1 million people outside Israel also speak Hebrew.

Motivation: I'm kinda sad it doesn't really have an equivalent in English because it means there's no way to really express what a lot of ethnic groups are on a deeper cultural level. Are Jewish people an ethnic group? A religious group? A culture? A 'people'? We're all of them at the same time. We're עם. It's a fairly simple word yet it carries so much power that I find most of the English equivalents (despite how precise they are at describing different types of groups) kind of lack.

Note: Another possible translation is nation, in the sense of a people not a state

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black history is not all about slave trade

Slave trade is not just black history it’s just 10% of the history africa holds

This is a message to my black brothers and sisters in America

Today I will be talking about the Zulu tribe

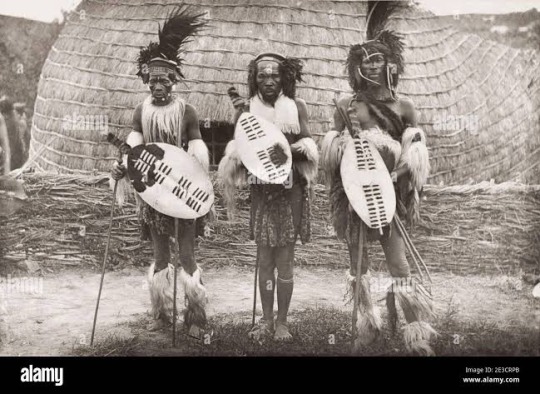

The ancestors of the Zulu migrated from west Africa into southeastern Africa during the Bantu migrations from 2000 BC until the 15th century. The Zulu tribe expanded into a powerful kingdom, subdued surrounding groups, and settled in the region known as KwaZulu-Natal in present day South Africa. After enduring colonialism and overcoming apartheid, they have emerged as the dominant ethnic group in South Africa todayAccording to Zulu ancestral belief, the first Zulu patriarch was the son of a Nguni chief who lived in the Congo Basin of Central Africa. By the early 1800s, the Zulu had migrated to Natal, where they lived among other Nguni-speaking chiefdoms. There were ongoing power struggles among these chiefdoms.Around 1808, Chief Dingiswayo of the Nguni-speaking Mthethwa people led wars of conquest to end the power struggles among the chiefs in the communities surrounding his chiefdom.Chief Dingiswayo centralized power by organizing the military into age-based groups, rather than lineage-based regimens. This weakened kinship ties of the conquered communities. Chief Dingiswayo left the conquered chiefdoms relatively intact after they accepted his dominion.The Zulu developed into a distinct cultural group by the time they were conquered by Chief Dingiswayo and his Mthethwa people in the early 1800s. At that time, the Zulu were a small lineage numbering around 2,000 people led by Chief Senzangakhona.Shaka, the future founder of the Zulu Kingdom, was the illegitimate son of the Chief Senzangakhona. Shaka was drafted into the Mthethwa and became one of Chief Dingiswayo's bravest warriors. When Chief Senzangakhona died, Shaka seized the Zulu throne.Using Dingiswayo's military style of weakening kinship ties amongst warriors, Shaka controlled the Zulu community. After Dingiswayo's death, he killed the legitimate heir and installed a puppet as Chief of the Mthethwa.Before long, Shaka seized control over Mthethwa's regiments and assumed power of the newly formed Zulu Kingdom in 1818.

Shaka, Zulu King 1818 to 1828.

Zulu tribe facts include the following:

Shaka Day is celebrated in September by slaughtering cattle, wearing traditional clothing, and wielding traditional weapons. Dignitaries from other tribes and nations attend.

Traditionally a senior male is the head of the clan. Young men train from childhood to fight and defend the clan. Members of the clan have kinship ties based on blood or marriage.

To show respect, the Zulu do not refer to elders by their first name; they use "Baba" meaning father, and "Mama" meaning mother.

Patrilineal inheritance and polygamy are practiced in Zulu culture; having more than one wife is acceptable if one can afford it.

In Zulu culture, bride wealth must traditionally be paid in cattle. Most native groups in South Africa, including Nguni-speaking Xhosa, Ndebele, and Swazi pay bride wealth.

#life#animals#culture#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#heritage#africa#biden is obama's puppet#england

648 notes

·

View notes

Text

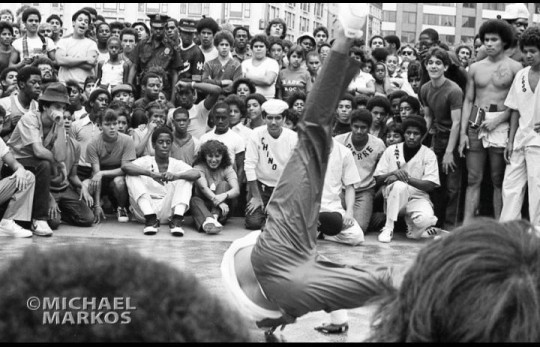

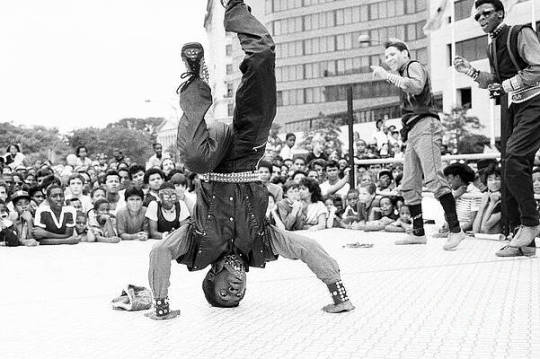

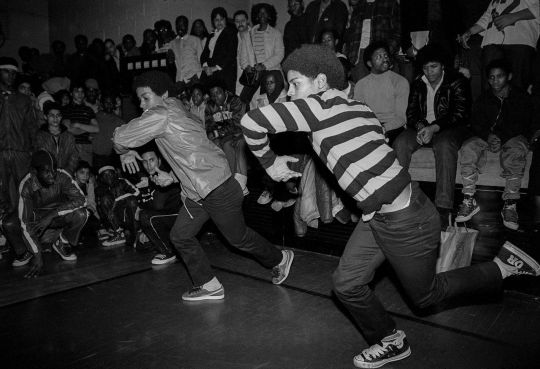

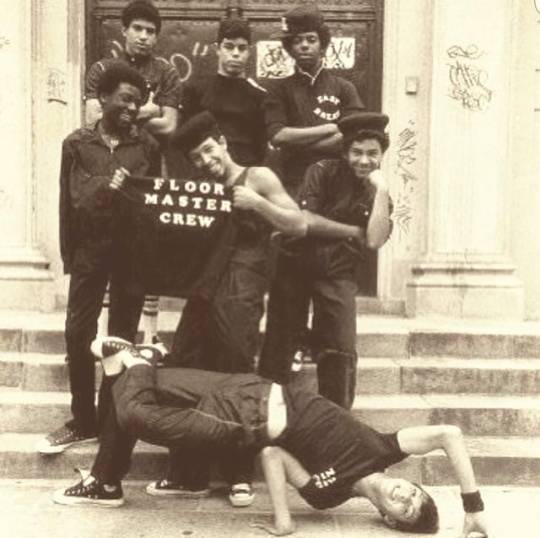

Breakin and Poppin History

This is an old post I saved. Check it out because there's some pertinent info from the pioneers on it's origins.Kind of long, so check it out in sequence at your leisure

"Breakin" and Poppin history

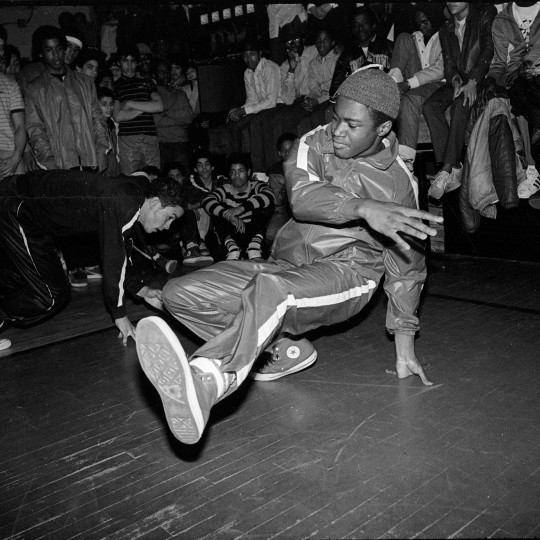

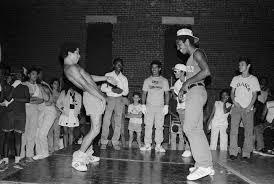

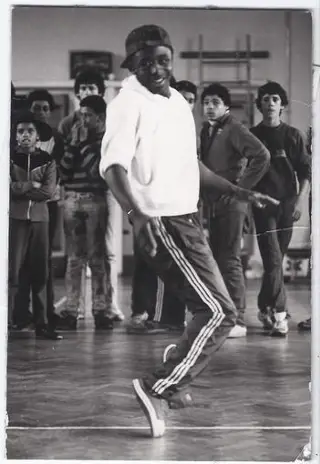

These are 2 separate dances. One from the West cost, the other from the East coast. It can be argued that both came from the western United States in the black community of L.A. ( Watts and Compton) The pioneers from NYC said that the basis on how they formated their style, was L.A.'s "locking" style. What ever the case, it was all seeded by African American youth. Breakdancing was created by black youth of Bronx, NY, mainly the Zulu Kings and Jr Black Spades, trying to one-up on each other at the early KoolHerc jams. The earliest recollection people have of it is 1973. Puerto Rican youth picked up on it circa 1975-76 by their own accounts, and they made a huge contribution to the development of the dance. Also creating groups around it and refining it even more. They brought the dance into the 80s were it spread like wildfire in the mainstream . It's AfroAmerican and Puerto Rican orgins where a distant memory as early as 1983

The media coined the term " breakdancing" in the early 80s as it's popularity spread. According to some of the Hispanic pioneers, the original black youth never gave it a name, but would sometimes loosely refer to the dance as " going to the floor". According to a Rock Steady member in the documentary "Freshest Kids" they had a name in the 70s to denote the original AfroAmerican style of the earlier 70s... The term was "Moreno style". In the latter 70s some called it "B- Boying.

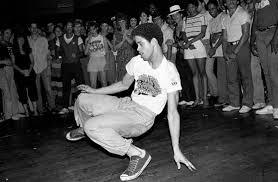

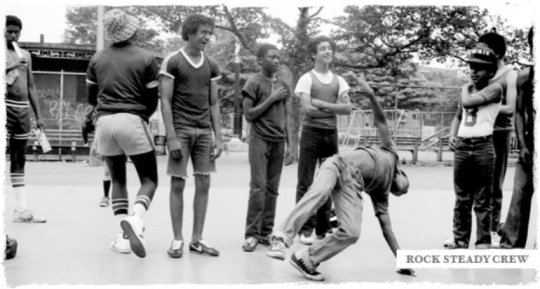

Lockin was created by L.A.’s Don Campbell (African American) in the late 60s. The concept spread to Fresno CA, where a new derivative of locking was developed. We now know it as Popping. Imported into L.A. from Fresno by two young African American streetdancers named "Boogaloo Sam and his brother Poppin Pete (circa 75 - 76), it debuted nationally in 1978 via Soultrain. Many youngsters and performers picked up on it soon after. Poppin was all lumped into breaking later. A hyped up resurgence of breaking and Popping was created by black and Hispanic youth of L.A. starting around 1986-1990. Also by east coast groups like the extended Rock Steady Crew. With it's airmoves and extensive spins, this form is still practiced by people of many ethnic groups. Even tournaments worldwide

Though originally a African American youth dance of the early 70s, Puerto Rican youth made a huge contribution to the development of breakin. The orginal Rock Steady Crew of the latter 1970s through the very early 80s

Filmed in front of Lincoln Center 1981, by a NYC tv station, this is before the dance was really known around the country, and dormant in those circles in Bronx ---and according to renowned Frosty Freeze in an early 80s documentary, parts of Harlem.

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/b9/ca/ff/b9caff2fa5cc9394e25ab2b0c329b687.png

1981

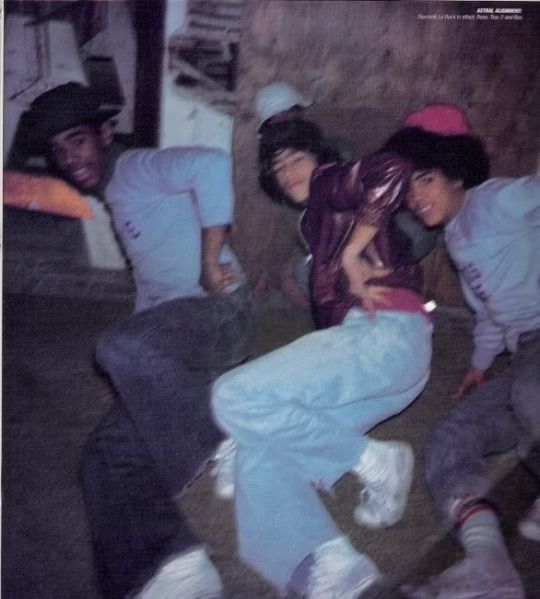

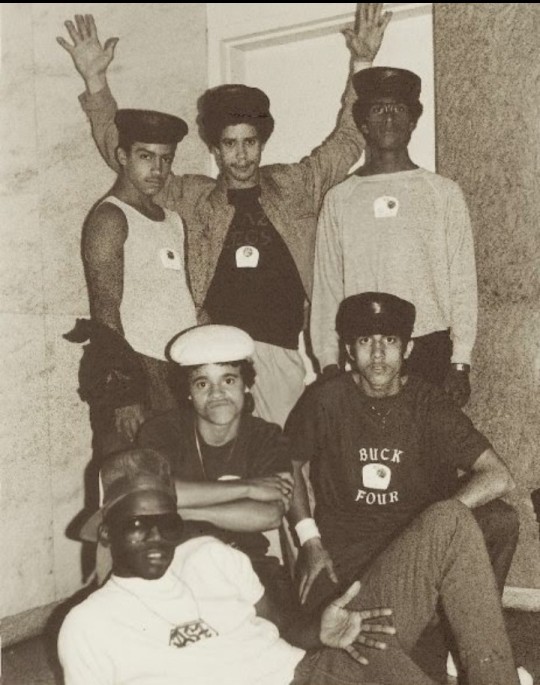

Rock Steady Crew 1980-81

Rene, Trac2, and Boss appearantly won a competition in 1978

Obviously the late 70s to very early 80s. The Puerto Rican youth in the center is the renowned Ken Swift and the black youth with his arms folded to the left is " Lil Crazy from the late 70s RSC, and to the right next the girl is forgotten member Kippy D.

The founders say there were actually 2 different crews who joined together to form the RSC. It was TBB (The Bronx Boys) from the mid 70s and Rock City of the 70s Bronx and Manhattan. Here's Louie Lou and Frosty from the Rock City days

Miscellaneous images of TBB and Rock Steady from the 70s and very early 80s

Link

Video compilation of 70s pioneers, mostly long forgotten African American " bboys" of that era, performing the style of that decade. Most of these are from like the 1990s and early new millennium. All videos are very brief ( less than 1 minute on most)

Link

WITH ARENA SIZED CROWDS, YOUNG FOLKS TOOK THE DANCE TO ANOTHER LEVEL. THIS IS WHAT THEY DO NOWADAYS

https://txt.fyi/+/7b4d8ead/

Looks like 83/84 (?)

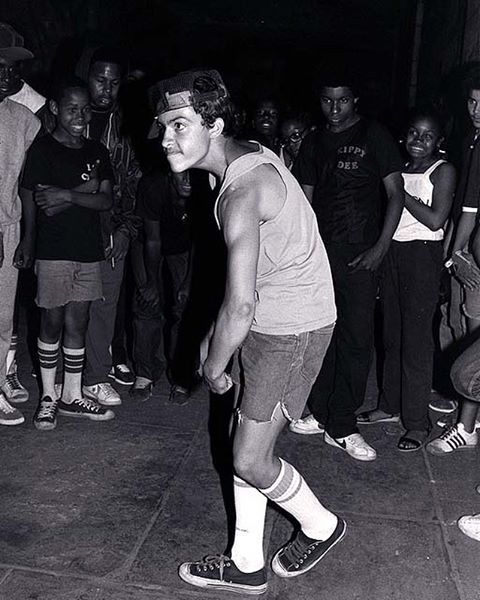

The picture above are original Rock Steady Crew members from appearantly the 1980s.

RSC co-founder

Jimmy Dee, the African American co-founder of the RSC (Rock Steady Crew) in the latter 70s... The original blog is offline now. I will try to recall some basic info he shared with us on the formation of RSC. Crazy Legs asked him to write a brief summary on this. He laughed because he'd heard about dozen or so stories on how they formed - and thought it to be less important where they came from, but more relevant of what breaking and Rock Steady has become. A quick detailed story was shared from the very cofounder..

A few of them branched out from a larger mid 70s group called TBB (The Bromx Boys) to form a group of their own. With the blessings of the former group, they formed RSC (no falling out between members like Batch as some rumors had it). It was names like Jim Lee, JoJo, Popeye and a few others. He met a new recruit named Crazy legs - who was excited and determine to be the best. Not long after, Jimmy went off to college but still loosely associated with and keep up on RSC over the years. Also astonished at what it has become in modern times

Video link is in the compilation TBB RSC by shwat2013. The Rock Steady Crew @ Central Park, NYC - YouTube. At about the last 1/8 of video, Crazy Legs introduces the 1977 cofounder (African American) to the crowd at a 2013 hip-hop reunion in Central park. Many never heard of or seen, because he went off to college ( circa early 80s)

A few links

1 in more recent times https://www.pinterest.com/pin/631981760196661962/

2

In this rare 1981 footage, Jimmy Dee sees the ZuluKings as the first when the news interviewer asks where does this come from. Keep in mind that he was a part of TBB in the mid 70s. They were closer to the essence back then and young and humble (roughly 17). In a modern Livestream, he says that 1981 is when he left NYC for Navy and college.

https://youtu.be/Q5YnNb2rSuw?si=1y5_ZDD-t_7q_s2b

3

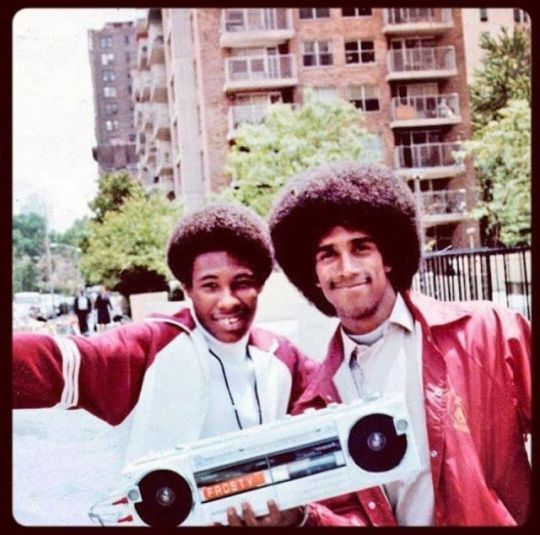

Two founders of Rock Steady Crew, Jimmy D and Lee (1977) https://i.pinimg.com/originals/1c/1b/99/1c1b99f349c13eab206133419375e96d.jpg

4

From the 1981 Lincoln Center battle. Some of the footage was used in the 1982 video for Planet Rock and Buffalo Gals 83 https://i.pinimg.com/originals/90/60/35/906035b98a0a209b096cf0cc09ffd5b3.jpg

Spy from the mid to latter 70s. He is Afro Puerto Rican. In a 2002 documentary, Crazy legs stated that Spy was the first person he had ever seen doing the dance as a 10 year old in 1976. Spy was roughly early teens. There are others who say that he was the best breaker they had ever seen in the decade of the 70s - hands down

1

Said to be mid 70s (76/77)

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/631981760210500335/visual-search/#imgViewer

.2

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/631981760196661910/

3

1979

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/631981760196662004

? Circa mid 70s, far right https://www.pinterest.com/pin/631981760196662268/

Probably the mid to latter 70s

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgyjN0QMUrujTbeJWKFZjhU5K5HkCWR8VQ3gJzri8If59QDyVDAIZvnwACqxyc3JxVJttwkJOT9g_rPwmYEWSKyiII2C3-N-_5f5Vj_xCg3zDGiVJ9UD0nofwIGiP62ngay_b_w-ewAzg/s960/Spy+%2528The+Crazy+Commanders%2529.jpg

These are from around 1981, NYC

.1981

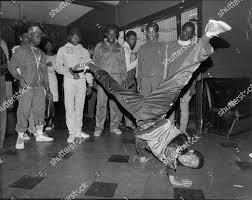

This is said to be Robbie Rob, the one Trac 2 said taught floor moves to the youngster who showed him in around 1975. He is also mentioned by Legendary Twins, Bom5 of TBB and others

Caption reads

BBoy Unsung Hero: This is the man who created a well known fundamental freeze that all BBoys/BGirls do throughout the world. This is Robbie Rob, one of the "First 11" Zulu Kings bboy. He is the creator of the "CHAIR" freeze that you all do today. Shouts to Trac 2 for supplying the picture.

Trac 2 also informs us that Robbie Rob was doing chair freezes as early as 73/74 in a modern Livestream (2024).

In another magazine article of the 90s, he says the original B-boys were black, but treated it like a passing fad more so

Skip to 49:38 for Robbie Rob

https://www.youtube.com/live/2aMi_fRNvhw?si=PayXMMec9QfhQa5E

Skip immediately over to 4:08 to hear Robbie Rob himself say he started chair or figure4 freezing in 1973

https://youtu.be/iUisqzxAI4g?si=G77mLxxFVFoCZMxh

Known original ZuluKings like Grand Mixer DXT and Theodore, perform old style from roughly 1974-76, in more modern times (2016 post)

https://youtu.be/MwiLIxU8Icc?si=iwksJceOrgxiIVzZ

Aby, the brother of Batch (TBB founder), had this to say on an earlier interview. TBB (The Bronx Boys) were known as the first Puerto Rican based b-boy crew in 1975/76

(you would think people would ask what ethnicity were they before)

Aby:

...As far as the Puerto Rican style of B-Boying is concerned…you know the Blacks had their own way of doing it…their own dance and from what I remember it was called The Go Off and we took some of that Go Off and added some of our style to it. You know we are also part of the African heritage…that's a part of our heritage, too. We come from the Spaniards, we also come from the African slaves that were brought to the Caribean Islands by the Spaniards and we come from the Tainos (the indigenous people of Puerto Rico)….so we got three different people in us. That's why I got green eyes, my dad is a black latino…my sister Joanna you know is a light skin Afro Rican. So we definetely got that influence."

SIR NORIN RAD (the interviewe):

"Willie Will (legendary Puerto Rican B-Boy from Rockwell Association) told me about how we was introduced to that original Black B-Boy Style of dancing which you referred to as The Go Off in 1976 by a B-Boy called Chopper that was down with the Zulu Nation. What was the relationship between TBB and the Zulu Nation? Was there any kind of contact at all?

Cholly Rock says that he first saw floor moves in 1974 with Legendary Twins and Clark Kent (African Americans). This is before the ZuluKings were formed in 1975. He stopped breaking in roughly 1978. When the latter 70s through 80s came around and he seen Rock Steady and others, he thought they were mimicking them from years prior. However impressed at what the dance evolved into

Correction. This is actually Doc aka Pooch, credited for teaching Beaver, Robbie Rob, and PowWow..floor style in roughly 1974. He's next to Alien Ness in this more modern photo. In an old post, it was mislabeled as Beaver

This is Beaver from a interview in more recent times ( roughly 2010). Pioneers like Trac2, Cholly Rock, Willie Will and others remember his heavy influence on b-boying back in the mid 70s

Fastbreaks of old Magnificent Force, says he started breaking in 75 a family party after seeing his cousins do moves. His cousins would chill with ZuluKings members at the time. Magnificent Force were from the Bronx and predate the 1983 youth craze (largely unknown outside of Bronx and Harlem before then). The group included Mr Wiggles of old Rock Steady Crew

Fast breaks Livestream interview

https://youtu.be/Cr4ajNmhgxA?si=Z_0amgr2nIfeXt9t

Fastbreaks 83 performance begins at 2:00

https://youtu.be/SF56Z281j9E?si=-GPXt5nonVCyGKyE

interviews with ole school 70s b-boys http://preciousgemsofknowledge79.blogspot.com/

Puerto Rican youth appearantly added spin moves and certain uprock styles to the dance format. This is from the Ed Sullivan show of 1957. Pay attention at 1:00 and 1:18

Link

youtube

Seen in old African American performers

In 1894, the Edison Production company filmed 3 African American performers named Joe Rastus · Denny Tolliver · Walter Wilkins, who are clearly uprocking into breaking moves. The film was entitled The Pickaninny Dance, from the 'Passing Show' · Director. William K.L. Dickson · Writer. Sydney Rosenfeld ·

youtube

1

1960s

https://youtu.be/JfnhSJPfHNI?si=zGYySUiBGDAdTTSQ

2

1920s - 50s

.https://youtu.be/Nld6odfRJws?si=KomuY2Sd4iiBPfdX

Basically rapping and breaking 1930

3

https://youtu.be/SVBpB7rSn7A?si=geEgw6BGCZVIkYk5

Modern beat added

https://youtu.be/Iat62Ab87qs

4

In this 1974 footage, Roberto, an Afro Puerto Rican, does the exact moves of Little Buck from 1957, in almost same sequence, two decades prior. To credit Puerto Ricans for breaking, some bring up the Roberto footage of 74, but when one mentions Little Buck from the 50s, all of a sudden there's no relation, or the it doesn't matter position is taken

Little Buck 1955. Skip immediately over to 2:34 near end to see the routine

https://youtu.be/DpV2Xl4e4YQ?si=SCZZh0k6jYxauKqQ

Robero Rona 1974. Skip immediately over to 4:18 to see the routine in a similar sequence as Little Buck in 1955

https://youtu.be/tnBuopICQso?si=n0jqrTs9auggKsO5

Berry Brothers

1

1941

https://youtu.be/fvDixy-U_6Q?si=lYlaLk5s2g4vMb4P

2

https://youtu.be/oOYhdW6sxoM?si=SnD2qJTqZjfsmoZr

Even though the youth of Bronx and Harlem probably never seen this footage in the early 70s "ghetto" neighborhoods, these type of dance patterns are common in all people.

Nigeria 1959

youtube

"Mainstream"

It's in the dance history of every race

1

.https://youtu.be/4axM1TZtkh0?si=ZkT8OQ6Xy6NxoWGA

2

youtube

Opening scene 1943

.https://youtu.be/-vPlO--nnGM

Actual Zulus of South Africa with traditional dance

https://youtu.be/ej7WTWv-sZI?si=ASb7-ec1WIP0jicG

The first known b-boy crew was ZuluKings of 1973-75 Bronx NYC. This is PeeWee Dance of the 70s crew (roughly early 90s), as he shows original Up top/going off/Burning/SpadeDance (uprocking) style. One Puerto Rican pioneer did mention that old style breaking, the brothers would spend ample time dancing on their feet and floor moves brief at the end

a

https://youtube.com/shorts/0yaupV6dChQ?si=TGw4UAc0EeOc-DIP

b

https://youtu.be/cOVikVl8yts?si=enFjuiCqfjmC8Sk2

c

https://youtu.be/1K8DY2NeaJs?si=K6z8hV9mLhIpDfkw

Video compilation of 70s pioneers, mostly long forgotten African American " bboys" of that era, performing the style of that decade. Most of these are from like the 1990s and early new millennium. All videos are very brief ( less than 1 minute on most)

Outtakes of Flashdance's breaking scene. The RockSteady crew goes back to the essence of the dance. Black guy with Afro goes back to the original group of 1976-77. His moniker was Frosty Freeze. This movie was filmed in 1981 and 82; released 1983 (the original song played in movie was Jimmy Castor's " It's Just Begun 1972)

1

youtube

2

As seen in the 1983 movie with the Jimmy Castor song (1972)

https://youtu.be/ShNmK5DdQO4?si=h40TwVca6I0rlM_0

As seen in the movie, with original Jimmy castor song. This is the first time many viewed the dance which was performed by Rock Steady Crew. Also, the 1983 video "Save the Overtime For Me" by Gladys Knight-featuring the NYC Breakers, was the first nationwide glimps of the dance for some.

youtube

More rare footage of late 70s- mid 80s breaking from the pioneers https://txt.fyi/+/7713cfe2/

WITH ARENA SIZED CROWDS, YOUNG FOLKS TOOK THE DANCE TO ANOTHER LEVEL. THIS IS WHAT THEY DO NOWADAYS https://txt.fyi/+/7b4d8ead/

Best documentary on the "b-boying component of hip-hop. From 2002, it has all pioneers from the 70s. Its African American origins are mentioned from 10;10 through roughly 15;15. Then again from 18;50 through 19;30. At roughly 15;50 through 16;20,, Spy is introduced as one of the first seen in the 70s. The West coast contribution starts at 34;00 https://youtu.be/lKb1vszkeC8

Poppin and Lockin footage

Absolutely African American in it's creation, Popping is a direct derivative of locking and roboting. Keep in mind that locking was created unintentionally by Don Campbell in 1969 as he tried to do another dance but incorrectly (from independent interviews with him and friends of the time). At some point, roboting began to get more fluid and less rigid. You can almost see the morph from roboting to popping in the first three mid 1970s videos of this link

Link

https://www.tumblr.com/afrcnamrcn-23/776849705489547264/1?source=share

Man on L.A' beach with home movie camera 1981. About midway through, he lucks up and captures youngsters popping. The dance is from 77

youtube

Lockin 1974 https://youtu.be/CQWsF4plYFI

Full version 1974 on Campus scene https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u6bBNLw_4Nk&list=WL&index=257&t=0s&app=desktop

1978 Lockin (just a ittle over 3 minutes) https://youtu.be/p5eD6dt0NZg

Tho locking is becoming"old hat" at this time, young blks of 1979 still practice, but this time incorporating a touch of popping into their routine. As stated before, it's a derivative of locking anyway. https://youtu.be/n2LSkizYmpM

From the show "What's Happening" in the mid 70s. The character "Rerun" is an early pioneer of that dance style. The Lockers display a faint hint of poppin (2:30 minutes) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6CU8eUjIP4&t=8s

Poplockin 1983 with JazzyJ from Soul Sonic Force https://youtu.be/pyYXcY9KwpE

Kango and Dr Ice of UTFO perform popping and boogaloo in 1983 (slightly before they're known). They clear up the differences between that and Breaking https://youtu.be/1EG4ksiblMs

The renowned Boogaloo Srimp ( Turbo) has an outstanding performance in this 1983 footage; starting around 0:40 https://youtu.be/QJ6IAouIyLA

Best documentary(s) on West coast hip hop. The first is from 1983, and the second from present day YouTube. The second one is by a man who has the credentials to educate on hiphop's history. Researching and interview these artist for a few decades, many of these MC's and DJ's he knows personally. Exellemt docs on the history. You may want to save in a watch later playlist. Both are over an hour long

1 https://youtu.be/GFkgObeA8AU

2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKvrT0orI5s&list=WL&index=2&t=15s

Lindy hop 1930s - 40s

Was created in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, and popularized in the late 30s and 40's. It spread to young Americans of all races in the 40s

1 (1939)

youtube

2

3

Second scene from 1941

youtube

4

1944 from African American made movie

.https://youtu.be/2Jm5zIXWLEs?si=Bpo3Ojvh8ixPuWF_

5

"Old Hat" by the 1950s, but still practiced

1

youtube

2

3

Be sure to stop at the bottom where it says "More from @afrcnamrcn-23". Don't be distracted by the pictures and links under that. They will occur again so that you can continue with the main post in sequence

.

1 note

·

View note