#Woburn abbey

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#country house#english country house#stately home#Woburn Abbey#Duke of Bedford#architecture#higginsandcole#england#preppy

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Woburn#Flower#Children#festival#Dancing#Enjoying#Fun day#Late 60s#Hippies#Woburn abbey#Love in#1967#bird#dance#open#wings

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

On This Day (27 Aug) in 1562, Margaret St John, Lady Russell, Countess of Bedford, died from smallpox at Woburn Abbey.

Margaret was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth I, the wife to Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, and mother of seven, including her eldest Anne Russell, who had also recently joined the Queen's household.

Smallpox, a highly infectious disease, transmitted by close contact, was virulent during the Elizabethan period. It was known to be fatal, especially to the vulnerable (children, elderly) and women. Early symptoms of the disease include high fever, fatigue, severe back pain, abdominal pain and vomiting, with the characteristic rash appearing 2-3 days later, initially on the face and hands.

Elizabeth I herself would contract smallpox in Oct 1562; whilst she survived this almost-fatal attack, she was left permanently scarred, as did Mary Dudley, Lady Sidney, who contracted it from the Queen from attending her.

Anne, who would go on to marry Ambrose Dudley, 3rd Earl of Warwick, did not have any children of her own. However, she took on a mothering role to her younger siblings, which included her youngest sister Margaret, later Countess of Cumberland (being only 2 years old at the time of her mother's death), as well as her nieces and nephews (including Lady Anne Clifford).

Margaret was interred in the 'Bedford Chapel' within St Michael's Church, Chenies: a chapel that had been constructed in 1556 by Anne Sapcote, the Dowager Countess of Bedford, for the place of rest for her late husband, John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford. The chapel became the preferred place of burial for members of the Russell family during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Margaret's husband Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, was buried with her on his death over 20 years later, in 1585, with the couple's tomb being decorated with a effigies, lying side-by-side.

#Margaret Russell#Margaret St John#Francis Russell#Anne Russell#Lady Anne Clifford#Woburn Abbey#Chenies#Chenies Manor House#St Michael's Church Chenies#smallpox#smallpox pandemic#Elizabeth I#tudor history#tudor england#tudor people#tudor women#The Dudley Women

0 notes

Text

The Most Noble Ian Russell, 13th Duke of Bedford of the sixth creation and Nicole, Duchess of Bedford with their Bassett Hound at Woburn Abbey.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

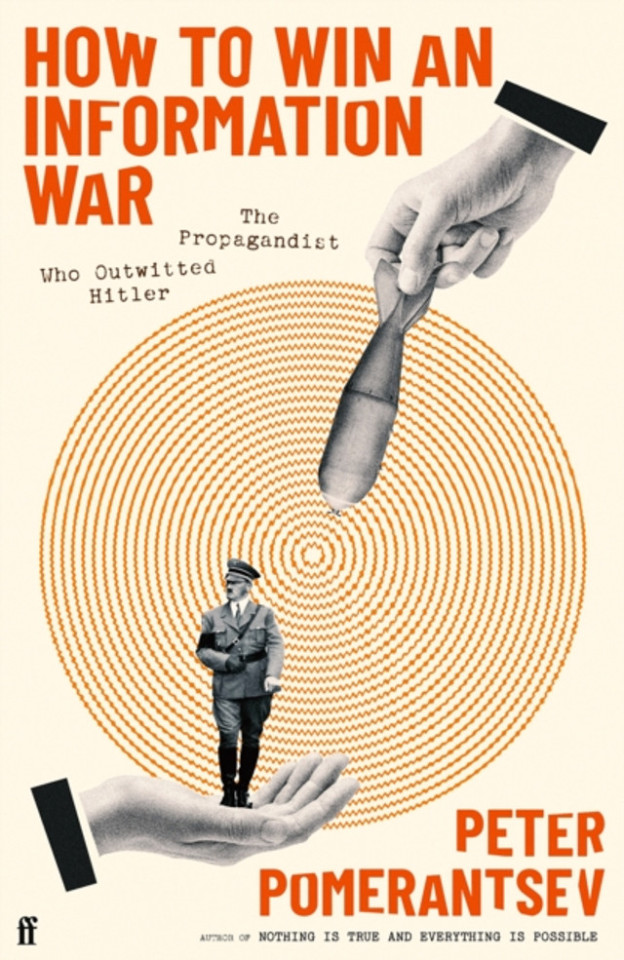

In 1941 a secret British radio station called on Germans to rise up against Hitler. Run by German exiles, it was explicitly left wing. The station’s target audience was “the Good German”. Its broadcasts were serious and idealistic: a ray of light amid totalitarian darkness. They were also a complete flop. With Nazi propaganda rampant, and Hitler’s armies seemingly invincible and on the march across Europe, few bothered to listen in.

It was at this point that Britain’s wartime intelligence services tried a more radical approach. That summer, a talented journalist called Sefton Delmer was given the job of beating the Nazis at their own information game. Delmer spent his childhood in Berlin and spoke fluent German. In the early 1930s he chronicled Hitler’s rise to power – flying in the Führer’s plane and attending his mass rallies – as a correspondent for the Daily Express.

Working from an English country house, Delmer launched an experimental radio station. He called it Gustaf Siegfried Eins, or GS1. Instead of invoking lofty precepts, or Marxism, Delmer targeted what he called the “inner pig-dog”. The answer to Goebbels, Delmer concluded, was more Goebbels. His radio show became a grotesque cabaret aimed at the worst and most Schwein-like aspects of human nature.

As Peter Pomerantsev writes in his compelling new study How to Win an Information War, Delmer was a “nearly forgotten genius of propaganda”. GS1 backed Hitler and was staunchly anti-Bolshevik. Its mysterious leader, dubbed der Chef, ridiculed Churchill using foul Berlin slang. At the same time the station lambasted the Nazi elite as a group of decadent crooks. They stole and whored, it said, as British planes bombed and decent Germans suffered.

Delmer’s goal was to undermine nazism from within, by turning ordinary citizens against their aloof party bosses. A cast of Jewish refugees and former cabaret artists played the role of Nazis. Recordings took place in a billiards room, located inside the Woburn Abbey estate in Bedfordshire, a centre of wartime operations. Some of the content was real. Other elements were made up, including titillating accounts of SS orgies at a Bavarian monastery.

The station was a sensation. Large numbers of Germans tuned in. The US embassy in Berlin – America had yet to enter the war – thought it to be the work of German nationalists or disgruntled army officers. The Nazis fretted about its influence. One unimpressed person was Stafford Cripps, the future chancellor of the exchequer, who complained to Anthony Eden, the then minister for foreign affairs, about the station’s use of “filthy pornography”.

By 1943, Delmer’s counter-propaganda operation had grown. He and his now expanded team ran a live news bulletin aimed at German soldiers, the Soldatensender Calais, as well as a series of clandestine radio programmes in a variety of languages. Delmer’s artist wife Isabel joined in. She drew explicit pictures showing a blonde woman having sex with a dark-skinned foreigner. Partisans sent the pamphlets to homesick German troops stationed in Crete.

Others who made a contribution to Delmer’s productions included Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, and the 26-year-old future novelist Muriel Spark. Fleming worked for naval intelligence. He brought titbits of information that made the show feel genuine, including the latest results from U-boat football leagues. Many Germans guessed the station was British. But they listened anyway, feeling it represented “them”.

Pomerantsev is an expert on propaganda and the author of two previous books on the subject, Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible and This Is Not Propaganda. The son of political dissidents in Kyiv, he was born in Ukraine and grew up in London. During the 00s he lived in Moscow and worked there as a TV producer. Since Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion he has been part of a project that documents Russian war crimes in Ukraine.

Like Delmer, Pomeranstev has personal experience of two rival cultures: one authoritarian, the other liberal and democratic. He draws parallels between the fascist 1930s and our own populist age. The same “underlying mindset” can be seen in dictators such as Putin and Xi Jinping, and wannabe strongmen and bullies such as Donald Trump. “Propagandists across the world and across the ages play on the same emotional notes like well-worn scales,” he observes.

In Pomerantsev’s view, propaganda works not because it convinces, or even confuses. Its real power lies in its ability to convey a sense of belonging, he argues. Those left behind feel themselves emboldened and part of a special community. It is a world of grievance, victimhood and enemies, where facts are meaningless. What matters are feelings and the illusion propaganda lends of “individual agency”. Its practitioners bend reality. And – as with Putin’s fictions about Ukraine – make murder possible.

The book offers a few ideas as to how we might fight back. When horrors were uncovered in Bucha, the town near Kyiv where Russian soldiers executed civilians, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, appealed to the Russian people. This didn’t cut through. Most preferred to believe the version shown on state TV: that Moscow was waging a defensive fight against “neo-Nazis”. It was a comforting lie that absolved Russians of personal responsibility.

Ukrainian activists hit a similar wall when they cold-called Russians and told them about the destruction caused by Kremlin bombing. Many called relatives in St Petersburg and other Russian cities to explain they were under attack. Typically, their family members did not believe them. “They really brainwashed you over there,” one said.

The activists had more success when they mentioned taxes or travel restrictions – issues that spoke to the self-interested “pig-dog”. Pomerantsev suggests that Delmer’s approach worked because he allowed people to care about the truth again, nudging them towards independent thought, while avoiding the pitfall of obvious disloyalty. He brought wit and creativity to his anti-propaganda efforts as well, turning his radio shows into bravura transmissions.

Pomerantsev makes an intriguing comparison between der Chef and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Russian oligarch who in summer 2023 staged a short-lived rebellion against Putin. Two months later, Prigozhin died in a plane crash. The oligarch was a charismatic figure who roasted Russia’s generals for their incompetent handling of the war. He used earthy prison slang. It was this ability to communicate in plain language that made him popular – and a rival.

The book muses on whether Delmer was ultimately good or bad. Are tricks and subterfuge justified in pursuit of noble goals? It concludes that the journalist’s greatest insight was his understanding of his own ordinariness, and how this might be exploited by unscrupulous governments and rabble-rousing individuals. “He was vulnerable to propaganda for the same reasons we all are – through the need to fit in and conform,” Pomerantsev notes.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Facebook)

Geezer Butler (pre-Black Sabbath) at the 'Festival of the Flower Children', Woburn Abbey, Woburn, Bedfordshire 1967

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The idea of an ‘orangery has a much more sophisticated ring to it, and in its purest form, an orangery is a glorious thing.

But what is an orangery, and how is it different to a conservatory?

Historically, the orangery is in some ways the father of all garden rooms, at least in European terms. It was in the 17th century that the (recently acquired) English mania for oranges led to the building of special structures to keep them at the required temperature. These tended to be built out of brick, with flat roofs and large windows along the south side to flood them with sunlight. it made sense to begin attaching orangeries to houses, rather than having them situated in the garden itself.

One of the most prolific designers of orangeries in this period was Sir Jeffry Wyatville, who created the examples at Chatsworth, Woburn Abbey and Longleat, alongside many others. He favoured a simple freestanding design built in stone with vast south-facing windows – the style that we might now still refer to as an orangery rather than a greenhouse or conservatory.

via: House & Garden UK

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 2, Poll 9

Lady Amherst's Pheasant vs Japanese Paradise Flycatcher

sources under cut

Lady Amherst's Pheasant

"it has AMAZING feathers and is very very pretty"

While the data is scant, there are reports that this species is a clinal migrant and lives in high altitudes in the summer and the foothills in winter, or during severe weather. Their typical range is within southwestern China and northern Myanmar.

They get their name from their English introduction by Lady Amherst to her estates, near the Duke of Bedford's Woburn Abbey. While feral populations are believed to be extinct, two have been sighted or photographed in recent years- Staplegrove, Taunton (2020) and Scotland (2021).

Japanese Paradise Flycatcher

"Look at it! It's even got eyeliner! It's so fabulous."

Their habitat is described as: "shady mature deciduous or mixed forest and plantations on low hills and mountains, but prefers wooded valleys with streams at lower elevations in Central Japan; in Southern Japan also in broadleaf evergreen forest." - BoW

Birds of the World: both species

Images: Pheasant (Summer Wong); Flycatcher (Natthaphat Chotjuckdikul)

#hipster bird main bracket#round 2#bracket: pretty a#lady amherst's pheasant#japanese paradise flycatcher#phasianidae#monarchidae

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captivating Fairy tale Grottos.

The Little Chapel, Les Vauxbelets, Guernsey.

Shell Grotto, Hampton Court House.

The grotto of Linderhof Castle.

The Palazzo Corsini Grotto in Rome, Italy.

Boboli Gardens Grotto, Florence, Italy.

The grotto of the Villa di Castello in Florence, Italy.

The right chamber of the grotto of the animals.

The left chamber of the grotto of the animals.

Villa Litta Grotto.

Villa Litta Modignani.

Villa Litta Modignani.

Villa Litta Modignani.

Chateau du Rambouillet Grotto.

Lourdes Grotto.

Our Lady of Lourdes Grotto, located on Dominican Hill Road Baguio, Philippines.

Grotto Rayavadee in Krabi, Thailand.

The Grotto at Isola Bella.

The Grotto of the Munich Residenz.

Woburn-Abbey-Grotto.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#country house#english country house#architecture#interior#higginsandcole#england#woburn#Woburn abbey#stately home

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Fresh flowers#Woburn#Flower#Children#festival#Flowers#Grass#Distribution#Sharing#Woburn abbey#Love in#1967

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

HENRY VIII AND HIS SIX WIVES

HENRY VIII AND HIS SIX WIVES

1972 film

Henry VIII and His Six Wives is a British historic film directed by Waris Hussein. The film was adapted from the miniseries, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1972). Keith Mitchell played King Henry VIII in both the miniseries and the film. The film stars Charlotte Rampling as Anne Boleyn, Jane Asher as Jane Seymour, and Lynne Frederick as Catherine Howard.

This film was decided to be made after the success of the miniseries. It was filmed at Hatfield House Old Palace, Hertfordshire, Woburn Abbey, Allington Castle, and Eton College.

#HenryVIIIandhissixwives #HenryVIIIandhissixwives1972 #HenryVIII #keithmitchell #lynnefrederick #catherinehoward

#Henry VIII and his six wives#Henry VIII and his six wives 1972#Henry VIII#Keith Mitchell#catherine howard#lynne frederick

1 note

·

View note

Text

From April 29th to May 2nd, 2024

29-04-2024

GUIDED BY VOICES “Sweating The Plague”; CAN “Flow Motion”; MICHAEL McGOLDRICK “Wired”; BILLY JOEL “52nd Street”; MIKE OLDFIELD “QE2”; SEBADOH “Bakesale”; THE CHEMICAL BROTHERS “Come With Us”; BILL RYDER-JONES “Iechyd Da”; LEE PERRY “Voodooism”; THE BEACH BOYS “Surfer Girl”; SQUAREPUSHER “Ufabulum”; ORBITAL “Orbital (1991)”; BELLOWHEAD “Hedonism”; GUIDED BY VOICES “Space Gun”; SONNY CLARK “Cool Struttin'”; LA DUSSELDORF “La Dusseldorf”; BILLY BRAGG “Workers Playtime”

01-05-2024

EARL HINES & HIS ORCHESTRA “Earl Hines 1942-1945”; NIRVANA “In Utero”; SUPERGRASS “Diamond Hoo Ha”; SERGE GAINSBOURG “Aux Armes Et Caetera”; DAVID BOWIE “Hunky Dory”; CARTER THE UNSTOPPABLE SEX MACHINE “30 Something”; MIKE OLDFIELD “Ommadawn”; DIRE STRAITS “Woburn Abbey 20-06-1992”; CLIFTON CHENIER “Frenchin' The Boogie”; L.L. COOL J “Walking With A Panther”; HOUSE OF LOVE “A Spy In The House Of Love”; VAN DYKE PARKS “Clang Of The Yankee Reaper”

02-05-2024

DE DANNAN “Jacket Of Batteries”; COMMON “Be”; LOUIS JORDAN & HIS TYMPANY FIVE “Louis Jordan And His Tympany Five”; THE FALL “The Light User Syndrome”; THE DELGADOS “Hate”; JOHN CARPENTER & ALAN HOWARTH “Halloween III: Season Of The Witch”; JOHNNY COPELAND “Texas Party”; THE CHEMICAL BROTHERS “Dig Your Own Hole”; THE DREAM SYNDICATE “The Days Of Wine And Roses”; DUBSTAR “Disgraceful”; VIC REEVES “I Will Cure You”; SMOG “Dongs Of Sevotion”; ERICA NOCKALLS “Dark Music From A Warm Place”; RICHARD THOMPSON “13 Rivers”

0 notes

Text

Saying "I Do" Near London: A Guide to Charming and Unforgettable Wedding Venues

London, a city brimming with history, culture, and undeniable charm, also offers a delightful backdrop for your special day. But with its vast sprawl and diverse neighborhoods, choosing the perfect wedding venue near London can feel overwhelming. Fret not, lovebirds! This guide unveils some of the most enchanting wedding locations near London, catering to a variety of styles, budgets, and guest lists. Fairytale Elegance: Stately Homes and Historic Venues For a touch of timeless grandeur, stately homes and historic venues near London offer a quintessential British wedding experience. Imagine exchanging vows in a grand ballroom adorned with glittering chandeliers, or strolling through manicured gardens hand-in-hand with your new spouse. - Syon Park:Nestled amidst 200 acres of landscaped parkland, Syon Park exudes an air of regal elegance. This grand Palladian mansion boasts a rich history, having been home to the Dukes of Northumberland for over 400 years. Choose from a variety of ceremony locations, including the awe-inspiring Great Hall or the intimate State Rooms. Celebrate with your loved ones in the opulent Conservatory or on the expansive South Lawn, offering picturesque views of the park. - Woburn Abbey:Steeped in history dating back to the 17th century, Woburn Abbey offers a truly unforgettable wedding setting. This magnificent country house boasts grand staterooms, a stunning library, and sprawling grounds. Exchange vows in the opulent Marble Hall or the romantic Garden Room, followed by a reception in the Venetian Dining Room or under a marquee on the Great Lawn. - Hampton Court Palace:Immerse yourselves in history by exchanging vows at Hampton Court Palace, the magnificent former residence of King Henry VIII. Imagine saying "I do" in the stunning Great Hall, followed by a reception in the opulent State Apartments or the picturesque gardens. This iconic venue offers a truly unique and unforgettable wedding experience. Urban Chic: Rooftop Venues and Boutique Hotels London's vibrant energy extends to its wedding venues. For a contemporary and stylish wedding, consider a rooftop venue or a boutique hotel offering stunning cityscapes and a sophisticated ambiance. - The Ned:This iconic landmark, housed in a beautifully restored former Midland Bank building, offers several unique spaces for your wedding celebration. Exchange vows amidst the grandeur of the Banking Hall or the opulent The Saloon, then celebrate with breathtaking city views from the rooftop Ned's Club. - 10-11 Carlton House Terrace:Overlooking the iconic St. James's Park, 10-11 Carlton House Terrace offers a prestigious and elegant setting for your wedding. This Grade II listed building boasts stunning Georgian architecture and a private courtyard ideal for intimate ceremonies. Celebrate with sweeping views of the city skyline from the rooftop terrace. - Dorsett City:For a modern and stylish wedding, consider Dorsett City, a luxurious hotel offering panoramic views of the London skyline. Exchange vows in the light-filled ballroom, followed by a reception on the rooftop terrace showcasing breathtaking cityscapes. This contemporary venue is perfect for couples seeking a chic and sophisticated setting for their special day. Rustic Charm: Countryside Manors and Hidden Gems Escape the hustle and bustle of the city and celebrate your love story amidst the tranquility of the English countryside. Several charming country houses and hidden gem venues located near London offer a rustic and romantic ambience. - Foxtail Barn:Nestled in the picturesque Chiltern Hills, Foxtail Barn is a beautifully converted 18th-century barn offering a rustic yet elegant setting for your wedding. Exchange vows in the light-filled barn, followed by a reception on the landscaped gardens or the charming courtyard. This enchanting venue is perfect for couples seeking an intimate and relaxed wedding celebration. - Petersham Nurseries:For a truly unique and enchanting wedding experience, consider Petersham Nurseries, a haven for nature lovers. Exchange vows amidst the lush greenery of the walled garden, followed by a reception under a marquee or in the charming café. This hidden gem offers a romantic and intimate setting for your special day. - Danesfield House: Steeped in Victorian charm, Danesfield House is a beautiful country house hotel located in the Thames Valley. Hope this guide helps you find your dream destination! Cheers! Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Luton Airport Taxi: Unlocking the top 10 things to do near London Luton airport

London Luton Airport is located in the middle of Bedfordshire, which is a busy county and acts as a gateway to London and the areas surrounding it. Upon arrival or departure from this busy aviation hub, tourists have many attractions to visit around.

In this blog post, we are going to take you through the top 10 things to do near London Luton Airport that will give you an idea about how versatile the place can be when it comes to adventurous souls.

Top 10 Things to Do Near London Luton Airport

Sited in Bedfordshire’s vibrant district, London Luton Airport serves as a busy gateway into the vibrant city of London plus its environs. This airport hub has been attracting numerous travelers who pass through it when going or returning from different places hence being provided with several attractive destinations close by. The area around London Luton Airport offers various experiences ranging from fascinating museums and preserved historic sites to beautiful parks and country estates that appeal to all sorts of individuals.

Come along with us as we unmask for you the top 10 things to do around Luton Airport promising everlasting memories.

1. Whipsnade Zoo:

Experience animal encounters and help save animals at one of Europe’s largest wildlife conservation parks. Whipsnade Zoo is really preferred by those nature lovers who are looking for an adventure holiday.

2. Wardown Park Museum:

Get engrossed in local history and culture at this captivating museum situated in a stunning Victorian mansion.

3. Stockwood Discovery Centre:

For horticulture enthusiasts, there are gardens with interactive exhibits at this family-friendly attraction that deals with the heritage of the locality.

4. ZSL London Zoo:

As one of the oldest zoos globally, visit world of wildlife wonders right in the heart of our capital city today!

5. St Albans Cathedral:

Admire medieval architecture and rich historical pasts found at St Albans Cathedral which is only a short driving distance away from this airport

6. Ashridge Estate:

In Chiltern Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, take a trip through scenic walks or cycle trails in this picturesque estate.

7. Woburn Abbey:

Time travel to the past and explore an art collection, old furniture and beautiful gardens at Woburn Abbey.

8. Verulamium Park:

Take leisurely strolls or have picnics along this vast park which has got Roman ruins, calm lakes and lush greenery.

9. Dunstable Downs:

With its broad spread of countryside viewings, it is an ideal hilltop for all outdoor enthusiasts who enjoy hiking and kite flying.

10. Hitchin Lavender:

This farm serves as the most peaceful site for anyone wanting to wander through aromatic lavender fields and relish the beauty of nature there.

How to Book a Luton Airport Taxi Online?

A. Selecting a Reputable Taxi Booking Platform:

• Research different online airport taxi booking platforms

• Find companies that have positive testimonials, good customer service, reliable payment options

• Check if they cater specifically for Luton Airport transfers

B. Choosing Pickup and Drop-off Locations:

• Key in exact addresses of both pickup location and drop off location

• Specify any terminal or place within the airport where you want to be picked from

• Consider nearby landmarks or key places that will facilitate your movement around easily

C. Indicating Date and Time of Travel:

• State the date when you will arrive or leave Luton Airport.

• Take into account flight duration as well as congestion on roads at that time of day.

• If possible choose flexible arrangements so that you can change plans in case of anything.

D. Personalizing Preferences & Additional Services:

• Such as car type, number of travellers or any other things such as baby seats or wheelchair accessible.

• Explore more services offered by the booking platform like meet and greet services or extra luggage assistance.

• Book the ride as per your specific requirements and preferences.

E. Making Payment and Confirming Booking:

• Check the booking details to see if everything is accurate.

• Go to the payment section and select how you want to pay for it.

• Check whether there are additional fees or taxes you have to pay before confirming what needs to be paid

• Confirm payment for my booking with all relevant information and receive a confirmation of my payment.

Benefits of Booking a Luton Airport Taxi Transfers with Kabbi Compare

When traveling from London Luton Airport, a taxi is one of the ways that can be used so that movement can be made easier. The only thing we think about when travelling is how do we get around most efficiently. There is no other better way than using Kabbi Compare, which offers incredible Luton airport taxi transfers. From fixed prices to amazing customer service, when reaching your destination without hassles, choose Kabbi Compare taxis online thus having stress-free journey.

While highlighting some of these amazing places near Luton Airport waiting for our discovery, let’s also go into detail on why Kabbi Compare should be your choice Luton Airport transfer provider.

Expert Drivers:

In the course of driving passengers safely through their journey, polite and experienced drivers are put first by Kabbi Compare team.

Fixed Fares:

You will enjoy an honest pricing policy with Kabbi compare’s flat rate system; this saves customers from being hit by astonish costs or greedy price surges in peak hours.

Service Available 24/7:

Regardless if there are late night flights or early morning ones, Kabbi Compare still operates all day long every day making it possible to cope with them.

Track your Flight:

Kabbi Compare will always keep you informed of any changes in flight schedule and help you to be on time for departure or arrival.

Secureness:

A regulated taxi service that takes into account the wellbeing of the customers is what Kabbi Compare has to offer.

Easy Reservation:

Book a taxi through the website, or get a Kabbi Compare app and forget about irritating moments when booking a cab.

Different Vehicles Availability:

Standard cabs, minivans, luxurious cars – make your choice depending on your needs at Kabbiecompare.com

Free Cancelation Policy:

It is absolutely free in case you need to change your travel plans and cancel your booking with Kabbi compare.

Free Waiting Period:

To let people, have enough time to find the driver after landing, there is a free waiting time at Kabbi Compare.

Large Network Coverage:

Benefit from a wide range of reliable taxi providers using this convenient tool designed by Kabbi compare for different areas within its network to avoid making wrong choices.

Conclusion

Discovering attractions near Luton airport opens up an exciting world where one can dive into the rich tapestry of history, culture and natural beauty found in the region. There are many conveyance options available when visiting various places near Luton airport but only few are as convenient as hiring a reliable cab with Kabbi Compare, which paves way for comfortable transfers throughout the trip. Henceforth take advantage of booking Luton Airport taxi service if you are off for some adventurous sightseeing or going on a simple day out.

FAQs

How do I arrange a transfer from Luton Airport?

• You can book online for services provided by Kabbi compare that offer pre-booking facilities across multiple platforms. Just a quick and simple search, that’s it.

2. What are the available transportation options for pickups at Luton Airport?

• These include taxis, private hire cars, shuttle services and public transport such as buses and trains.

3. Can I pre-book a taxi transfer service at Luton Airport?

• Yes, you may book a taxi or transfer service for your arrival at Luton Airport. Booking in advance lets you reserve your transportation beforehand so that there are no hitches from the airport to wherever you’re going.

4. Are there any extra costs for airport pick-ups at Luton Airport?

• Luton Airport charges may differ depending on the mode of transport chosen by the customer and if they have special requests such as meet-and-greet services or additional stops along the way.

5. How long does it take to get from Luton Airport to central London by taxi or transfer service?

• The journey time between Luton Airport and central London using a taxi or transfer service depends on traffic congestion, the time of day and where exactly in London you are heading. On average it takes approximately 1 to 1.5 hours.

#luton airport taxi#luton airport transfer#luton airport taxi transfers#luton airport transfer service#taxi from luton airport#taxi service to luton airport

0 notes