#William Garriott

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Andrea Contato’s New Book, “Video Games: The People, Games, and Companies - Part II”, is Crowdfunding an English Translation

Andrea Contato has launched a fundraising campaign for his next book about video gaming history. Back it today!

Andrea Contato, as you may recall, is the author of Through the Moongate, a two-volume book that chronicles the history of Origin Systems and Richard Garriott’s career as a game developer. He is also the author of a five-volume work, published (or soon to be published) in Italian, on the history of video games and the gaming industry. The first volume was translated into English and published…

#Activision#Atari#Atari VCS#Commodore 64#Donkey Kong#Ken Williams#King&039;s Quest#Nintendo#Richard Garriott#Roberta Williams#Sierra On-Line#Ultima#Wizardry

1 note

·

View note

Text

NASA astronaut Don Leslie Lind PhD American physicist, naval aviator Don Leslie Lind was selected an astronaut in NASA Group 5 in April 1966. During the Apollo era, Lind served as CapCom – Capsule Communicator during Apollo 11 and 12. By 1971, Lind was assigned as backup pilot for the Skylab space station missions 3 and 4, as well as being a crew member for a potential Skylab Rescue mission. Finally, in April 1985, Lind flew onboard space shuttle Challenger mission 51-B, spending 7 days in space. In this 1981 official NASA portrait, Don Lind wore his yellow dial Seiko 6139 automatic chronograph, a watch he had been wearing since Skylab training in 1973. Other Apollo era astronauts wearing a Seiko 6139 included William Pogue, Owen Garriott and James Irwin. (Photo: NASA)

#Aviator#Astronaut#NASA#chronograph#automatic#6139#military#montres#moonwatchuniverse#spaceflight#uhren#pilot watch#US Navy#space shuttle#Zulu time#Seiko

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

since we're discussing book recs, do you have any recs for stuff about the formulation of The Addict, as discussed in your kendallposts? or do the antipsych books/essays also cover addiction

yeah so, in that post i basically did an ad hoc synthesis of deleuze's 'postscript on the societies of control'; foucault's lectures at the collège de france, specifically the 1975–76 series; a few things mark fisher mentions in 'capitalist realism'; and some elements of byung-chul han's 'psychopolitics' (even tho his reading of foucault leaves a lot to be desired). these are well-known texts and other people have certainly brought them together, though i don't know off the top of my head of anyone using them in that specific way in reference to kendall roy succession lol.

that model (bare bones of a model, really) has limited explanatory potential outside of narrative fiction, largely because it's bouncing so heavily off foucault and deleuze on biopolitics and control societies, and neither of them were good historians. also, with kendall, so much of the figuration of addiction is specifically in regards to coke and catholic bourgeois masculinity, so it's not aiming for or achieving any kind of universal discourse on addiction writ large.

in general i would say antipsych literature does have a lot to say about addiction as well, though there are critical points of distinction historically and presently in terms of the clinical and disciplinary treatments of addiction as opposed to other psychiatric diagnoses. also, 'addiction' is in some ways a misleading category that flattens distinctions between different substances and discourses about users. for example, in the context of the us alone, there are radically different stories to tell about conceptions of alcohol, crack cocaine, psychedelics, synthetic opioids, and so on and so forth. the idea of a single neurobiological state of 'addiction', and a single figure of the 'addict', is more a function of politics and medical specialisation over the course of the last two centuries than anything else.

anyway, some places i would suggest to start on addiction specifically are:

how the brain disease paradigm remoralizes addictive behaviour, in 'science and culture' vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 46–64, by mark elam (2015); doi 10.1080/09505431.2014.936373

birth of a brain disease: science, the state, and addiction neuropolitics, in 'history of the human sciences' vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 52–67, by scott vrecko (2010); doi 10.1177/0952695110371598

crack in the rearview mirror: deconstructing drug war mythologies, in 'social justice' vol. 31, no. 1/2, pp. 182–199, by craig reinarman & harry g levine (2004); jstor.org/stable/29768248

addiction trajectories, ed. eugene a raikhel & william campbell garriott (2013)

white market drugs: big pharma and the hidden history of addiction in america, by david herzberg (2020) (i disagree strongly with his public policy recommendations, but this text is useful in historicising the 'opioid crisis' and in showing the construction of the drug/medicine dichotomy and the accompanying functions of 'white markets' vs 'black markets' in the us)

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Practical jokes in space. A dummy was left behind by the Skylab 3 crew on the exercise bike (wearing Skylab 4 Pilot William Pogue’s uniform) for the subsequent crew to discover following docking, Nov 1973. 2 other dummies were placed about America’s 1st space station including Commander Gerald Carr in the Lower Body Negative Pressure Device & one for Edward Gibson in the waste compartment. The good news was the trio had 84 days to get things organized. I guess it gets boring after 59 days in space; can’t blame Skylab 3 crew Alan Bean, Owen Garriott & Jack Lousma for their hijinks! Sadly, Skylab 4 had no following crew to prank as it was the final crewed mission to the space station, which later came crashing down to Earth in 1979.

#skylab#space station#space program#astronauts#nasa#aerospace#1973#space#astronaut#skylab 4#space flight#space explorer#1970s#space travel#spacecraft#skylab 3#outer space#space exploration#spaceman

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skylab and Space Shuttle Astronaut Owen Garriott Dies at 88

Rest In Peace. April 16, 2019 Former astronaut and long-duration spaceflight pioneer Owen Garriott, 88, died today, April 15, at his home in Huntsville, Alabama. Garriott flew aboard the Skylab space station during the Skylab 3 mission and on the Space Shuttle Columbia for the STS-9/Spacelab-1 mission. He spent a total of 70 days in space.

Image above: Scientist-Astronaut Owen K. Garriott, science pilot of the Skylab 3 mission, is stationed at the Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) console in the Multiple Docking Adapter of the Skylab space station in Earth orbit. From this console the astronauts actively control the ATM solar physics telescope. (sl3-108-1288). Image Credit: NASA. “The astronauts, scientists and engineers at Johnson Space Center are saddened by the loss of Owen Garriott,” said Chief Astronaut Pat Forrester. “We remember the history he made during the Skylab and space shuttle programs that helped shape the space program we have today. Not only was he a bright scientist and astronaut, he and his crewmates set the stage for international cooperation in human spaceflight. He also was the first to participate in amateur radio from space, a hobby many of our astronauts still enjoy today.” Garriott was born in Enid, Oklahoma. He earned a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the University of Oklahoma, and master’s and doctoral degrees in electrical engineering from Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. Garriott served as an electronics officer while on active duty with the U.S. Navy from 1953 to 1956, and was stationed aboard several U.S. destroyers at sea. He then taught electronics, electromagnetic theory and ionospheric physics as an associate professor at Stanford. He performed research in ionospheric physics and has authored or co-authored more than 40 scientific papers and one book on this subject.

Image above: Hall of Fame astronaut Owen Garriott thanks the audience for their applause at the 2011 U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame induction ceremony at NASA's Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. Image Credits: NASA/Jim Grossmann. He was selected as a scientist-astronaut by NASA in June 1965, and then completed a 53-week course in flight training at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona. He logged more than 5,000 hours flying time -- including more than 2,900 hours in jet and light aircraft, spacecraft and helicopters. In addition to NASA ratings, he held FAA commercial pilot and flight instructor certification for instrument and multi-engine aircraft. Garriott was the science-pilot for Skylab 3, the second crewed Skylab mission, and was in orbit from July 28 to Sept. 25, 1973. His crewmates were Commander Alan Bean and Pilot Jack Lousma. The crew accomplished 150% of mission goals while completing 858 revolutions of the Earth and traveling some 24.5 million miles. The crew installed replacement rate gyros used for attitude control of the spacecraft and a twin pole sunshade used for thermal control, and repaired nine major experiment or operational equipment items. They devoted 305 hours to extensive solar observations and completed 333 medical experiment performances to obtain valuable data on the effects of extended weightlessness on humans. The crew of Skylab 3 logged 1,427 hours and 9 minutes each in space, setting a world record for a single mission, and Garriott spent 13 hours and 43 minutes in three separate spacewalks outside the orbital workshop.

Image above: Scientist-astronaut Owen K. Garriott, Skylab 3 science pilot, participates in the Aug. 6, 1973 extravehicular activity during which he and astronaut Jack Lousma, Skylab 3 pilot, deployed the twin pole solar shield to help shade the Orbital Workshop. Image Credit: NASA. On his second and final flight, Garriott flew as a mission specialist on the ninth space shuttle mission and the first six-person flight. He launched aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia for STS-9/Spacelab-1 from Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on Nov. 28, 1983. His crewmates were Commander John Young, Pilot Brewster Shaw, Jr., fellow mission specialist Robert Parker, and Payload Specialists Byron Lichtenberg and Ulf Merbold of (ESA) European Space Agency. This six-person crew was the largest yet to fly aboard a single spacecraft, the first international shuttle crew and the first to carry payload specialists. During STS-9, the first human amateur radio operations in space were conducted using Garriott's station call, W5LFL. After 10 days of Spacelab hardware verification and around-the-clock scientific operations, Columbia and its laboratory cargo landed on the dry lakebed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on Dec. 8, 1983. Garriott held other positions at Johnson Space Center such as deputy and later director of Science and Applications, and as the assistant director for Space and Life Science. For Garriott’s official NASA biography, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/garriott_owen.pdf Related link: Skylab: https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/skylab/ Images (mentioned), Text, Credits: NASA/Jason Townsend. R.I.P., Orbiter.ch Full article

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

New book series, Police/Worlds: studies in security, crime and governance

New book series, Police/Worlds: studies in security, crime & governance @Police_Worlds @CornellPress

When we started this blog over 8 years (!) ago, part of the motivation was that those of us working on issues of policing from within the discipline of anthropology felt relatively disjointed and in need of a common forum to figure out just where we could go with our research as a collective project.

One of the benefits of entering the “Associate Professor” stage of one’s career, I suppose, is…

View On WordPress

#Anthropology of Policing#books#Cornell University Press#Ilana Feldman#Kevin Karpiak#monographs#Police/Worlds: studies in security crime and governance#Sage House News#Sameena Mulla#William Garriott

0 notes

Video

youtube

Video Games 1983: Events The fourth Arcade Awards are held, for games released during 1981-1982, with Tron winning best arcade game, Demon Attack best console game, David’s Midnight Magic best computer game, and Galaxian best standalone game. At the first Golden Joystick Awards ceremony (held in 1984), Jetpac takes Game of the Year. Video Game Crash of 1983 A major shakeout of the North American video game industry (“the crash of 1983”) begins. By 1986, total video games sales will decrease from US$3.2 billion to US$0.1 billion. These are some of the best video games released in 1983! Video Games Featured in this Video: Mario Bros Arcade Congo Bongo Arcade Track and Field Arcade Lode Runner Home Computer Spelunker Atari 8-bit Bomberman MSX Digger IBM PC Battlezone Atari 2600 Phoenix Atari 2600 Enduro Atari 2600 Hunchback Arcade Vastar Arcade Keystone Kapers Atari 2600 Laser Gates Atari 2600 Krull Atari 2600 Space Ace Arcade Dragon’s Lair Arcade Punch-Out Arcade Baseball Famicom Popeye Famicom Donkey Kong Famicom Donkey Kong Jr. Famicom Donkey Kong 3 Arcade Frostbite Atari 2600 Texas Chainsaw Massacre Atari 2600 Dracula Intellivision Congo Bongo Sega SG 1000 Guzzler Sega SG 1000 I, Robot Arcade Major Havoc Arcade Vote for Your Favorite Video Games of 1983: https://ift.tt/2Zj5Dw4 Home Computers in 1983 Apple Computer releases the Apple IIe, which becomes their most popular 8-bit machine. Microsoft Japan releases MSX, an early standardized home computer architecture. Sega releases the SC-3000, a personal computer version of the SG-1000 console, in Japan. Consoles in 1983 SG-1000 console by Sega and Famicom console by Nintendo were released in Japan, on the same day! Shortly after Famicom's release, complaints begin to surface about rampant system instability, prompting Nintendo to issue a product recall and to rerelease the machine with a new motherboard. Vote for Your Favorite Video Games of 1983: https://ift.tt/2Zj5Dw4 Gaming innovations: 1.First arcade laserdisc game: Sega’s Astron Belt 2.Third generation of home consoles started with releases of 3.Nintendo Famicom and Sega SG-1000 consoles (released on the same day) 4.Ultima III: Exodus by Richard Garriott, one of the first role-playing video games to use tactical, turn-based combat 5.Koei releases Nobunaga’s Ambition and sets a standard for the historical simulation and strategy RPG genres Console Games in 1983 Mattel Electronics publishes World Series Baseball for the Intellivision, one of the first video games to use multiple camera angles. Activision’s final big year of Atari 2600 releases includes Enduro, Keystone Kapers and Robot Tank. Computer Video Games 1983 Infocom releases Planetfall, which becomes one of their top sellers. Origin Systems publishes Ultima III: Exodus, one of the first role-playing video games to use tactical, turn-based combat. ASCII releases Bokosuka Wars for the Sharp X1 in Japan, precursor to the tactical role-playing game and real-time strategy genres. Koei releases Nobunaga’s Ambition for Japanese computers Electronic Arts publishes its first titles: Hard Hat Mack, Pinball Construction Set, Archon, M.U.L.E. and more. Also, Bug-Byte releases Matthew Smith’s Manic Miner, a platform game, for the ZX Spectrum. Rare, releases its first video games, Jetpac and Atic Atac. Hudson Soft releases Bomberman. Psion releases Chequered Flag, the first driving game published for the ZX Spectrum, one of the first computer car simulators, and the first driving game with selectable cars. Vote for Your Favorite Video Games of 1983: https://ift.tt/2Zj5Dw4 Arcade Games in 1983 Namco releases Mappy. Atari releases Star Wars, a color vector graphics game based on the popular film franchise. Sega releases Astron Belt. It was the first laserdisc game in Europe, second in Japan. It uses pre-rendered, computer-animated film footage as backdrops, overlaid with sprite graphics. Nintendo releases Mario Bros., which features the first appearance of Mario’s brother, Luigi. Cinematronics releases Advanced Microcomputer Systems’s Dragon’s Lair, the third laserdisc video game, and the first in the American market. Other Arcade Video Games 1983 Namco releases Pac & Pal exclusively in Japan. Bally/Midway releases Spy Hunter. They also release Jr. Pac-Man and quiz game Professor Pac-Man without Namco’s authorization, and the latter is an immediate flop. Nintendo releases Punch-Out!! in Japan. Williams releases Blaster, which was originally programmed on an Atari 8-bit computer. Thank for watching the video! Please like this video and subscribe to the channel :) Music used in this video: 1.Punchout CPS2 Remix 2.Donkey Kong Arcade Main Theme Remix 3.Mappy Theme Song (Trap Remix) 4.C64 Longplay - Frantic Freddie (HQ) All rights for the music belong to the authors I do not own any rights for the music by Retroconsole

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Return to Zork

Where should we mark the beginning of the full-motion-video era, that most extended of blind alleys in the history of the American games industry? The day in the spring of 1990 that Ken Williams, founder and president of Sierra On-Line, wrote his latest editorial for his company’s seasonal newsletter might be as good a point as any. In his editorial, Williams coined the term “talkies” in reference to an upcoming generation of games which would have “real character voices and no text.” The term was, of course, a callback to the Hollywood of circa 1930, when sound began to come to the heretofore silent medium of film. Computer games, Williams said, stood on the verge of a leap that would be every bit as transformative, in terms not only of creativity but of profitability: “How big would the film industry be today if not for this step?”

According to Williams, the voice-acted, CD-based version of Sierra’s King’s Quest V was to become the games industry’s The Jazz Singer. But voice acting wasn’t the only form of acting which the games of the next few years had in store. A second transformative leap, comparable to that made by Hollywood when film went from black and white to color, was also waiting in the wings to burst onto the stage just a little bit later than the first talkies. Soon, game players would be able to watch real, human actors right there on their monitor screens.

As regular readers of this site probably know already, the games industry’s Hollywood obsession goes back a long way. In 1982, Sierra was already advertising their text adventure Time Zone with what looked like a classic “coming attractions” poster; in 1986, Cinemaware was founded with the explicit goal of making “interactive movies.” Still, the conventional wisdom inside the industry by the early 1990s had shifted subtly away from such earlier attempts to make games that merely played like movies. The idea was now that the two forms of media would truly become one — that games and movies would literally merge. “Sierra is part of the entertainment industry — not the computer industry,” wrote Williams in his editorial. “I always think of books, records, films, and then interactive films.” These categories defined a continuum of increasingly “hot,” increasingly immersive forms of media. The last listed there, the most immersive medium of all, was now on the cusp of realization. How many people would choose to watch a non-interactive film when they had the opportunity to steer the course of the plot for themselves? Probably about as many as still preferred books to movies.

Not all that long after Williams’s editorial, the era of the full-motion-video game began in earnest. The first really prominent exemplar of the species was ICOM Simulations’s Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective series in 1992, which sent you wandering around Victorian London collecting clues to a mystery from the video snippets that played every time you visited a relevant location. The first volume of this series alone would eventually sell 1 million copies as an early CD-ROM showcase title. The following year brought Return to Zork, The 7th Guest, and Myst as three of the five biggest games of the year; all three of these used full-motion video to a greater or lesser extent. (Myst used it considerably less than the other two, and, perhaps not coincidentally, is the member of the trio that holds up by far the best today.) With success stories like those to look to, the floodgates truly opened in 1994. Suddenly every game-development project — by no means only adventure games — was looking for ways to shoehorn live actors into the proceedings.

But only a few of the full-motion-video games that followed would post anything like the numbers of the aforementioned four games. That hard fact, combined with a technological counter-revolution in the form of 3D graphics, would finally force a reckoning with the cognitive dissonance of trying to build a satisfying interactive experience by mixing and matching snippets of nonmalleable video. By 1997, the full-motion-video era was all but over. Today, few things date a game more instantly to a certain window of time than grainy video of terrible actors flickering over a background of computer-generated graphics. What on earth were people thinking?

Most full-motion-video games are indeed dire, but they’re going to be with us for quite some time to come as we continue to work our way through this history. I wish I could say that Activision’s Return to Zork, my real topic for today, was one of the exceptions to the rule of direness. Sadly, though, it isn’t.

In fact, let me be clear right now: Return to Zork is a terrible adventure game. Under no circumstances should you play it, unless to satisfy historical curiosity or as a source of ironic amusement in the grand tradition of Ed Wood. And even in these special cases, you should take care to play it with a walkthrough in hand. To do anything else is sheer masochism; you’re almost guaranteed to lock yourself out of victory within the first ten minutes, and almost guaranteed not to realize it until many hours later. There’s really no point in mincing words here: Return to Zork is one of the absolute worst adventure-game designs I’ve ever seen — and, believe me, I’ve seen quite a few bad ones.

Its one saving grace, however, is that it’s terrible in a somewhat different way from the majority of terrible full-motion-video adventure games. Most of them are utterly bereft of ideas beyond the questionable one at their core: that of somehow making a game out of static video snippets. You can almost see the wheels turning desperately in the designers’ heads as they’re suddenly confronted with the realization that, in addition to playing videos, they have to give the player something to actually do. Beyond Zork, on the other hand, is chock full of ideas for improving upon the standard graphic-adventure interface in ways that, on the surface at any rate, allow more rather than less flexibility and interactivity. Likewise, even the trendy use of full-motion video, which dates it so indelibly to the mid-1990s, is much more calculated than the norm among its contemporaries.

Unfortunately, all of its ideas are undone by a complete disinterest in the fundamentals of game design on the part of the novelty-seeking technologists who created it. And so here we are, stuck with a terrible game in spite of it all. If I can’t quite call Return to Zork a noble failure — as we’ll see, one of its creators’ stated reasons for making it so callously unfair is anything but noble — I can at least convince myself to call it an interesting one.

When Activision decided to make their follow-up to the quickie cash-in Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 a more earnest, better funded stab at a sequel to a beloved Infocom game, it seemed logical to find themselves a real Infocom Implementor to design the thing. They thus asked Steve Meretzky, whom they had just worked with on Leather Goddesses 2, if he’d like to design a new Zork game for them as well. But Meretzky hadn’t overly enjoyed trying to corral Activision’s opinionated in-house developers from a continent away last time around; this time, he turned them down flat.

Meretzky’s rejection left Activision without a lot of options to choose from when it came to former Imps. A number of them had left the games industry upon Infocom’s shuttering three years before, while, of those that remained, Marc Blank, Mike Berlyn, Brian Moriarty, and Bob Bates were all employed by one of Activison’s direct competitors. Activision therefore turned to Doug Barnett, a freelance artist and designer who at been active in the industry for the better part of a decade; his most high-profile design gig to date had been Cinemaware’s Lords of the Rising Sun. But he had never designed a traditional puzzle-oriented adventure game, as one can perhaps see all too well in the game that would result from his partnership with Activision. He also didn’t seem to have a great deal of natural affinity for Zork. In the lengthy set of notes and correspondence relating to the game’s development which has been put online by The Zork Library, a constant early theme on Activision’s part is the design’s lack of “Zorkiness.” “As it stands, the design constitutes more of a separate and unrelated story, rather than a sequel to the Zork series,” they wrote at one point. “It was noted that ‘Zork’ is the name of a vast ancient underground empire, yet Return to Zork takes place in a mostly above-ground environment.”

In fairness to Barnett, Zork had always been more of a state of mind than a coherent place. With the notable exception of Steve Meretzky, everyone at Infocom had been wary of overthinking a milieu that had originally been plucked out of the air more or less at random. In comparison to other shared worlds — even other early computer-game worlds, such as the Britannia of Richard Garriott’s Ultima series — there was surprisingly little there there when it came Zork: no well-established geography, no well-established history which everybody knew — and, most significantly of all, no really iconic characters which simply had to be included. At bottom, Zork boiled down to little more than a modest grab bag of tropes which lived largely in the eye of the beholder: the white house with a mailbox, grues, Flood Control Dam #3, Dimwit Flathead, the Great Underground Empire itself. And even most of these had their origin stories in the practical needs of an adventure game rather than any higher world-building purpose. (The Great Underground Empire, for example, was first conceived as an abandoned place not for any literary effect but because living characters are hard to implement in an adventure game, while the detritus they leave behind is relatively easy.)

That said, there was a distinct tone to Zork, which was easier to spot than it was to describe or to capture. Barnett’s design missed this tone, even as it began with the gleefully anachronistic, seemingly thoroughly Zorkian premise of casting the player as a sweepstakes winner on an all-expenses-paid trip to the idyllic Valley of the Sparrows, only to discover it has turned into the Valley of the Vultures under the influence of some pernicious, magical evil. Barnett and Activision would continue to labor mightily to make Return to Zork feel like Zork, but would never quite get there.

By the summer of 1992, Barnett’s design document had already gone through several revisions without entirely meeting Activision’s expectations. At this point, they hired one Eddie Dornbrower to take personal charge of the project in the role of producer. Like Barnett, Dornbrower had been working in the industry for quite some time, but had never worked on an adventure game; he was best known for World Series Major League Baseball on the old Intellivision console and Earl Weaver Baseball on computers. Dornbrower gave the events of Return to Zork an explicit place in Zorkian history — some 700 years after Infocom’s Beyond Zork — and moved a big chunk of the game underground to remedy one of his boss’ most oft-repeated objections to the existing design.

More ominously, he also made a comprehensive effort to complicate Barnett’s puzzles, based on feedback from players and reviewers of Leather Goddesses 2, who were decidedly unimpressed with that game’s simple-almost-to-the-point-of-nonexistence puzzles. The result would be the mother of all over-corrections — a topic we’ll return to later.

Unlike Leather Goddess 2, whose multimedia ambitions had led it to fill a well-nigh absurd 17 floppy disks, Return to Zork had been planned almost from its inception as a product for CD-ROM, a technology which, after years of false promises and setbacks, finally seemed to be moving toward a critical mass of consumer uptake. In 1992, full-motion video, CD-ROM, and multimedia computing in general were all but inseparable concepts in the industry’s collective mind. Activision thus became one of the first studios hire a director and actors and rent time on a sound stage; the business of making computer games had now come to involve making movies as well. They even hired a professional Hollywood screenwriter to punch up the dialog and make it more “cinematic.”

In general, though, while the computer-games industry was eager to pursue a merger with Hollywood, the latter was proving far more skeptical. There was still little money in computer games by comparison with movies, and there was very little prestige — rather the opposite, most would say — in “starring” in a game. The actors which games could manage to attract were therefore B-listers at best. Return to Zork actually collected a more accomplished — or at least more high-profile — cast than most. Among them were Ernie Lively, a veteran supporting player best known to a generation of ten-year-old boys as Cooter, the mechanic from The Dukes of Hazzard; his daughter Robyn Lively, fresh off a six-episode stint as a minor character on David Lynch’s prestigious critic’s darling Twin Peaks; Jason Hervey, who was still playing older brother Wayne on the long-running coming-of-age sitcom The Wonder Years; and Sam Jones, whose big shot at leading-man status had come and gone when he starred in the dreadful Flash Gordon film of 1980.

If the end result would prove less than Oscar-worthy, it’s for the most part not cringe-worthy either. After all, the cast did consist entirely of acting professionals, which is more than one can say for many productions of this ilk — and certainly more than one can say for the truly dreadful voice acting in Leather Goddess of Phobos 2, Activision’s previous attempt at a multimedia adventure game. While they were hampered by the sheer unfamiliarity of talking directly “to” the invisible player of the game — as Ernie Lively put it, “there’s no one to act off of” — they did a decent job with the slight material they had to work with.

The fact that they were talking to the player rather than acting out scenes with one another actually speaks to a degree of judiciousness in the use of full-motion video on Activision’s part. Rather than attempting to make an interactive movie in the most literal sense — by having a bunch of actors, one of them representing the protagonist, act out each of the player’s choices — Activision went for a more thoughtful mixed-media approach that could, theoretically anyway, eliminate most of the weaknesses of the typical full-motion-video adventure game. For the most part, only conversations involved the use of full-motion video; everything else was rendered by Activision’s pixel artists and 3D modelers in conventional computer graphics. The protagonist wasn’t shown at all: at a time when the third-person view that was the all but universal norm in adventure games, Activision opted for a first-person view.

The debate over whether an adventure-game protagonist ought to be a blank state which the player can fill with her own personality or an established character which the player merely guides and empathizes with was a longstanding one even at the time when Return to Zork was being made. Certainly Infocom had held rousing internal debates on the subject, and had experimented fairly extensively with pre-established protagonists in some of their games. (These experiments sometimes led to rousing external debates among their fans, most notably in the case of the extensively characterized and tragically flawed protagonist of Infidel, who meets a nasty if richly deserved end no matter what the player does.) The Zork series, however, stemmed from an earlier, simpler time in adventure games than the rest of the Infocom catalog, and the “nameless, faceless adventurer,” functioning as a stand-in for the player herself, had always been its star. Thus Activision’s decision not to show the player’s character in Return to Zork, or indeed to characterize her in any way whatsoever, is a considered one, in keeping with everything that came before.

In fact, the protagonist of Return to Zork never actually says anything. To get around the need, Activision came up with a unique attitude-based conversation engine. As you “talk” to other characters, you choose from three stances — threatening, interested, or bored — and listen only to your interlocutors’ reactions. Not only does your own dialog go unvoiced, but you don’t even see the exact words you use; the game instead lets you imagine your own words. Specific questions you might wish to ask are cleverly turned into concrete physical interactions, something games do much better than abstract conversations. As you explore, you have a camera with which to take pictures of points of interest. During conversations, you can show the entries from your photo album to your interlocutor, perhaps prompting a reaction. You can do the same with objects in your inventory, locations on the auto-map you always carry with you, or even the tape recordings you automatically make of each interaction with each character.

So, whatever else you can say about it, Return to Zork is hardly bereft of ideas. William Volk, the technical leader of the project, was well up on the latest research into interface design being conducted inside universities like MIT and at companies like Apple. Many such studies had concluded that, in place of static onscreen menus and buttons, the interface should ideally pop into existence just where and when the user needed it. The result of such thinking in Return to Zork is a screen with no static interface at all; it instead pops up when you click on an object with which you can interact. Since it doesn’t need the onscreen menu of “verbs” typical of contemporaneous Sierra and LucasArts adventure games, Return to Zork can give over the entirety of the screen to its graphical portrayal of the world.

In addition to being a method of recapturing screen real estate, the interface was conceived as a way to recapture some of the sense of boundless freedom which is such a characteristic of parser-driven text adventures — a sense which can all too easily become lost amidst the more constrained interfaces of their graphical equivalent. William Volk liked to call Return to Zork‘s interface a “reverse parser”: clicking on a “noun” in the environment or in your inventory yields a pop-up menu of “verbs” that pertain to it. Taking an object in your “hand” and clicking it on another one yields still more options, the equivalent of commands to a parser involving indirect as well as direct objects. In the first screen of the game, for example, clicking the knife on a vulture gives options to “show knife to vulture,” “throw knife at vulture,” “stab vulture with knife,” or “hit vulture with knife.” There are limits to the sense of possibility: every action had to be anticipated and hand-coded by the development team, and most of them are the wrong approach to whatever you’re trying to accomplish. In fact, in the case of the example just mentioned as well as many others, most of the available options will get you killed; Return to Zork loves instant deaths even more than the average Sierra game. And there are many cases of that well-known adventure-game syndrome where a perfectly reasonable solution to a problem isn’t implemented, forcing you to devise some absurdly convoluted solution that is implemented in its stead. Still, in a world where adventure games were getting steadily less rather than more ambitious in their scope of interactive possibility — to a large extent due to the limitations of full-motion video — Return to Zork was a welcome departure from the norm, a graphic adventure that at least tried to recapture the sense of open-ended possibility of an Infocom game.

Indeed, there are enough good ideas in Return to Zork that one really, really wishes they all could have been tied to a better game. But sadly, I have to stop praising Return to Zork now and start condemning it.

The most obvious if perhaps most forgivable of its sins is that, as already noted, it never really manages to feel like Zork — not, at least, like the classic Zork of the original trilogy. (Steve Meretzky’s Zork Zero, Infocom’s final release to bear the name, actually does share some of the slapstick qualities of Return to Zork, but likewise rather misses the feel of the original.) The most effective homage comes at the very beginning, when the iconic opening text of Zork I appears onscreen and morphs into the new game’s splashy opening credits. It’s hard to imagine a better depiction circa 1993 of where computer gaming had been and where it was going — which was, of course, exactly the effect the designers intended.

https://www.filfre.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/rtz1.mp4

Once the game proper gets under way, however, modernity begins to feel much less friendly to the Zorkian aesthetic of old. Most of Zork‘s limited selection of physical icons do show up here, from grues to Flood Control Dam #3, but none of it feels all that convincingly Zork-like. The dam is a particular disappointment; what was described in terms perfect for inspiring awed flights of the imagination in Zork I looks dull and underwhelming when portrayed in the cruder medium of graphics. Meanwhile the jokey, sitcom-style dialog that confronts you at every turn feels even less like the original trilogy’s slyer, subtler humor.

This isn’t to say that Return to Zork‘s humor doesn’t connect on occasion. It’s just… different from that of Dave Lebling and Marc Blank. By far the most memorable character, whose catchphrase has lived on to this day as a minor Internet meme, is the drunken miller named Boos Miller. (Again, subtlety isn’t this game’s trademark.) He plies you endlessly with whiskey, whilst repeating, “Want some rye? Course you do!” over and over and over in his cornpone accent. It’s completely stupid — but, I must admit, it’s also pretty darn funny; Boos Miller is the one thing everyone who ever played the play still seems to remember about Return to Zork. But, funny though he is, he would be unimaginable in any previous Zork.

https://www.filfre.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/rtz3.mp4

Of course, a lack of sufficient Zorkiness need not have been the kiss of death for Return to Zork as an adventure game in the abstract. What really does it in is its thoroughly unfair puzzle design. This game plays like the fever dream of a person who hates and fears adventure games. It’s hard to know where to even start (or end) with this cornucopia of bad puzzles, but I’ll describe a few of them, ranked roughly in order of their objectionability.

The Questionable: At one point, you find yourself needing to milk a cow, but she won’t let you do so with cold hands. Do you need to do something sensible, like, say, find some gloves or wrap your hands in a blanket? Of course not! The solution is to light some of the hay that’s scattered all over the wooden barn on fire and warm your hands that way. For some reason, the whole place doesn’t go up in smoke. This solution is made still more difficult to discover by the way that the game usually kills you every time you look at it wrong. Why on earth would it not kill you for a monumentally stupid act like this one? To further complicate matters, for reasons that are obscure at best you can only light the hay on fire if you first pick it up and then drop it again. Thus even many players who are consciously attempting the correct solution will still get stuck here.

The Absurd: At another point, you find a bra. You have to throw it into an incinerator in order to get a wire out of it whose existence you were never aware of in the first place. How does the game expect you to guess that you should take such an action? Apparently some tenuous linkage with the 1960s tradition of bra burning and, as a justification after the fact, the verb “to hot-wire.” Needless to say, throwing anything else into the incinerator just destroys the object and, more likely than not, locks you out of victory.

The Incomprehensible: There’s a water wheel out back of Boos’s house with a chock holding it still. If you’ve taken the chock and thus the wheel is spinning, and you’ve solved another puzzle that involves drinking Boos under the table (see the video above), a trapdoor is revealed in the floor. But if the chock is in place, the trapdoor can’t be seen. Why? I have absolutely no idea.

The Brutal: In a way, everything you really need to know about Return to Zork can be summed up by its most infamous single puzzle. On the very first screen of the game, there’s a “bonding plant” growing. If you simply pull up the plant and take it with you, everything seems fine — until you get to the very end of the game many hours later. Here, you finally find a use for the plant you’ve been carting around all this time. Fair enough. But unfortunately, you need a living version of it. It turns out you were supposed to have used a knife to dig up the plant rather than pulling or cutting it. (The question of how it should survive even this treatment, considering you don’t plant it again in a pot or anything — much less how you can dig anything up with a knife — goes unanswered.) Guess what? You now get to play through the whole game again from the beginning.

All of the puzzles just described, and the many equally bad ones, are made still more complicated by the game’s general determination to be a right bastard to you every chance it gets. If, as Robb Sherwin once put it, the original Zork games hate their players, this game has found some existential realm beyond mere hatred. It will let you try to do many things to solve each puzzle, but, of those actions that don’t outright kill you, a fair percentage lock you out of victory in one way or another. Sometimes, as in the case of its most infamous puzzle, it lets you think you’ve solved them, only to pull the rug out from under you much later.

So, you’re perpetually on edge as you tiptoe through this minefield of instant deaths and unwinnable states; you’ll have a form of adventure-game post-traumatic-stress syndrome by the time you’re done, even if you’re largely playing from a walkthrough. The instant deaths are annoying, but nowhere near as bad as the unwinnable states; the problem there is that you never know whether you’ve already locked yourself out of victory, never know whether you can’t solve the puzzle in front of you because of something you did or didn’t do a long time ago.

It all combines to make Return to Zork one of the worst adventure games I’ve ever played. We’ve sunk to Time Zone levels of awful with this one. No human not willing to mount a methodical months-long assault on this game, trying every possibility everywhere, could possibly solve it unaided. Even the groundbreaking interface is made boring and annoying by the need to show everything to everyone and try every conversation stance on everyone, always with the lingering fear that the wrong stance could spoil your game. Adventure games are built on trust between player and designer, but you can’t trust Return to Zork any farther than you can throw it. Amidst all the hand-wringing at Activision over whether Return to Zork was or was not sufficiently Zorky, they forgot the most important single piece of the Infocom legacy: their thoroughgoing commitment to design, and the fundamental respect that commitment demonstrated to the players who spent their hard-earned money on Infocom games. “Looking back at the classics might be a good idea for today’s game designers,” wrote Computer Gaming World‘s Scorpia at the conclusion of her mixed review of Return to Zork. “Good puzzle construction, logical development, and creative inspiration are in rich supply on those dusty disks.” None of these, alas, is in correspondingly good supply in Return to Zork.

The next logical question, then, is just how Return to Zork‘s puzzles wound up being so awful. After all, this game wasn’t the quickie cash grab that Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 had been. The development team put serious thought and effort into the interface, and there were clearly a lot of people involved with this game who cared about it a great deal — among them Activision’s CEO Bobby Kotick, who was willing to invest almost $1 million to bring the whole project to fruition at a time when cash was desperately short and his creditors had him on a short leash indeed.

The answer to our question apparently comes down to the poor reception of Leather Goddesses 2, which had stung Activision badly. In an interview given shortly before Return to Zork‘s release, Eddie Dornbrower said that, “based on feedback that the puzzles in Leather Goddesses of Phobos [2] were too simple,” the development team had “made the puzzles increasingly difficult just by reworking what Doug had already laid out for us.” That sounds innocent enough on the face of it. But, speaking to me recently, William Volk delivered a considerably darker variation on the same theme. “People hated Leather Goddesses of Phobos 2 — panned it,” he told me. “So, we decided to wreak revenge on the entire industry by making Return to Zork completely unfair. Everyone bitches about that title. There’s 4000 videos devoted to Return to Zork on YouTube, most of which are complaining because the title is so blatantly unfair. But, there you go. Something to pin my hat on. I made the most unfair game in history.”

For all that I appreciate Volk sharing his memories with me, I must confess that my initial reaction to this boast was shock, soon to be followed by genuine anger at the lack of empathy it demonstrates. Return to Zork didn’t “wreak revenge” on its industry, which really couldn’t have cared less. It rather wreaked “revenge,” if that’s the appropriate word, on the ordinary gamers who bought it in good faith at a substantial price, most of whom had neither bought nor commented on Leather Goddesses 2. I sincerely hope that Volk’s justification is merely a case of hyperbole after the fact. If not… well, I really don’t know what else to say about such juvenile pettiness, so symptomatic of the entitled tunnel vision of so many who are fortunate enough to work in technology, other than that it managed to leave me disliking Return to Zork even more. Some games are made out of an openhearted desire to bring people enjoyment. Others, like this one, are not.

I’d like to be able to say that Activision got their comeuppance for making Return to Zork such a bad game, demonstrating such contempt for their paying customers, and so soiling the storied Infocom name in the process. But exactly the opposite is the case. Released in late 1993, Return to Zork became one of the breakthrough titles that finally made the CD-ROM revolution a reality, whilst also carrying Activision a few more steps back from the abyss into which they’d been staring for the last few years. It reportedly sold 1 million copies in its first year — albeit the majority of them as a bundled title, included with CD-ROM drives and multimedia upgrade kits, rather than as a boxed standalone product. “Zork on a brick would sell 100,000 copies,” crowed Bobby Kotick in the aftermath.

Perhaps. But more likely not. Even within the established journals of computer gaming, whose readership probably didn’t constitute the majority of Return to Zork‘s purchasers, reviews of the game were driven more by enthusiasm for its graphics and sound, which really were impressive in their day, than by Zork nostalgia. Discussed in the euphoria following its release as the beginning of a full-blown Infocom revival, Return to Zork would instead go down in history as a vaguely embarrassing anticlimax to the real Infocom story. A sequel to Planetfall, planned as the next stage in the revival, would linger in Development Hell for years and ultimately never get finished. By the end of the 1990s, Zork as well would be a dead property in commercial terms.

Rather than having all that much to do with its Infocom heritage, Return to Zork‘s enormous commercial success came down to its catching the technological zeitgeist at just the right instant, joining Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective, The 7th Guest, and Myst as the perfect flashy showpieces for CD-ROM. Its success conveyed all the wrong messages to game publishers like Activision: that multimedia glitz was everything, and that design really didn’t matter at all.

If it stings a bit that this of all games, arguably the worst one ever to bear the Infocom logo, should have sold better than any of the rest of them, we can comfort ourselves with the knowledge that Quality does have a way of winning out in the end. Today, Return to Zork is a musty relic of its time, remembered if at all only for that “want some rye?” guy. The classic Infocom text adventures, on the other hand, remain just that — widely recognized as timeless classics, their clean text-only presentations ironically much less dated than all of Return to Zork‘s oh-so-1993 multimedia flash. Justice does have a way of being served in the long run.

(Sources: the book Return to Zork Adventurer’s Guide by Steve Schwartz; Computer Gaming World of February 1993, July 1993, November 1993, and January 1994; Questbusters of December 1993; Sierra News Magazine of Spring 1990; Electronic Games of January 1994; New Media of June 24 1994. Online sources include The Zork Library‘s archive of Return to Zork design documents and correspondence, Retro Games Master‘s interview with Doug Barnett, and Matt Barton’s interview with William Volk. Some of this article is drawn from the full Get Lamp interview archives which Jason Scott so kindly shared with me. Finally, my huge thanks to William Volk for sharing his memories and impressions with me in a personal interview.)

source http://reposts.ciathyza.com/return-to-zork/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

High Score: The Milestones of the Gaming Industry

Netflix has once-again cashed in on our love of nostalgia with a docu-series focused on an industry riddled with highs and lows. High Scores explores the decades-long history behind the gaming industry we know today, starting with some of the very first incarnations of interactive digital entertainment. The surprisingly long and complex history of video games is heavily truncated to fit within the six-episode docu-series created by France Costrel. While avid gamers will note sizable gaps and missing titles that may have been worth mentioning, casual viewers are in for a speedy, albeit often disjointed overview of the pioneers that made gaming the multi-billion dollar industry it is today.

High Scores first turns the clock back to the 1970s, long before the development of the 3D graphics we take for granted. Unfortunately, right off the bat, we’re skipping one noteworthy event in 1958 when a physicist invented the very first video game. Only minutes into the series and you can easily pinpoint who the target audience is. It could have easily taken a moment to talk about William Higinbotham’s simplistic tennis video game, but his name isn’t well-known in the industry today. So, therefore, it’s inconsequential to a casual audience.

What’s most disappointing about Costrel’s series is that it often feels like a retread of stories we’ve heard before. If you have any knowledge about video game history, then the video game crash, the emergence of the NES, the introduction to Sonic the Hedgehog, and the controversy around Mortal Kombat and Night Trap aren’t anything new. It would have been welcomed if High Scores expanded its horizons and took risks to introduce new some concepts.

By starting with games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man, the formation of Atari, Inc., and the early days of the video game cartridge, High Scores is appealing to the masses and not the video game historians looking for an in-depth analysis. The point isn’t to explore the full history of games, but instead to showcase milestone titles and how they worked off of one another and progressed the technology. The point is to feed off of our nostalgia.

Anyone who grew up in the 80s and 90s will spend all six episodes remembering their childhood. From the first Nintendo World Championship to the inception of John Madden Football, High Scores is one big “remember when” segment layered with discussions on development and software advancement.

Directors William Acks, Sam LaCroix, France Costrel, and Melissa Wood rounded up a delightful band of talent to talk about their time in gaming. Narrated by the voice of Mario, Charles Martinet, the docu-series does hold interest, especially when colorful characters like Richard Garriott (Ultima) and John Romero are in front of the camera. Though some of these tales have been well-known for years - such as the disaster that was E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial - it was interesting to hear some of them told from the men and women behind them. Listen to Howard Scott Warshaw talk about the development hell that was E.T. puts into perspective why it was such a bad game.

The scattered stories dotting the six-episode series are interesting to listen to, largely because the personalities behind them are at least passionate about their craft. However, they aren’t going to do much but fuel the nostalgia for early-era gaming. The series does take a slight turn during its third episode, “Role Players,” with the story of Ryan Best and GayBlade. Best, as part of the underrepresented LGBT community, developed a game that mocked the anti-gay political spitfires of that time, including Pat Buchanan. Though Best completed GayBlade, he lost all traces of the RPG, ultimately relegating it to obscurity. Spoiler alert, though! Not all hope was lost. High Scores doesn’t go into specifics, but the Schwules Museum of Berlin had a copy to share with its original creator.

It would have been nice to have more stories like Best’s interlaced with gaming powerhouses like Gail Tilden, former Nintendo of America marketing director, and Nolan Bushnell, the proclaimed godfather of video games. Instead, the series was marked with often awkward stories of video game champions reliving that one time umpteen years ago they competed in (and won) a video game tournament.

Granted, for what it was intended to be, High Scores does hit the mark. You walk away pining for the days before recurring Call of Duty games and the loud riffs between battle royale fans. You can once again feel an issue of Nintendo Power in your hands and smell the signature scent of arcades.

The history of gaming is a long and complicated one, and Costrel found a nice balance between long and tedious and trite and childish to tell some of the most important pieces of it. What’s important to remember is that the industry’s history is ongoing. Even today, visionaries are creating masterpieces that will change the face of genres. High Scores only aimed to tell a small sliver that ultimately launched P.C. and console gaming as we know them today. And considering that, it mostly succeeded.

At SJR Research, we specialize in creating compelling narratives and provide research to give your game the kind of details that engage your players and create a resonant world they want to spend time in. If you are interested in learning more about our gaming research services, you can browse SJR Research’s service on our site at SJR Research.

0 notes

Text

Promised by Leah Garriott - Book Review, Preview

Promised by Leah Garriott – Book Review, Preview

[book-info]

It wasn’t until I was a good way through Promised that I saw the similarities to Pride and Prejudice. The way in which Margaret was so repulsed by Lord Williams’ manner and his haughty attitude. Then I started noticing other subtle things and began to realize that there were a number of connections. What I appreciated is that the author did not attempt to make this a retelling,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

SXSW 2018 PanelPicker submissions by our CreativeMornings community

We love when Austin welcomes the world to SXSW… almost as much as we love putting a spotlight on the local talent that makes our community so inspiring. Please take a few minutes to vote for these SXSW PanelPicker submissions:

#CMATX SPEAKERS:

Jen Spencer - What to Do When the 'Sexy' Wears Off: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/75067

Richard Garriott - Overhead Transit: Cable, Hyperloop, PRT & Drones: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/77490

Kate Niederhoffer - Robot meets Freud: bots in mental health: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/69646

Carl Hooker - #FailFest - A Learnshop on Risk-Taking: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/73045

#CMATX VOLUNTEER ORGANIZERS:

Brian Thompson - How to Build a Minimum Viable Brand & Maximum Love: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/77134

Alexis Puchek - Commanding Respect As The Only Woman In The Room: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/72163

Breanna Fowler - How We Broke the Billion $$$ Ad Industry: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/75176

#CMATX COMMUNITY MEMBERS:

Andrew Buck - How to Craft a New Identity for Your Organization: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/77328

Meghan Williams - Can Ethical Fashion Become the New Norm?: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/75822

Erin Feldman - How to Tell Stories When Everyone's a Storyteller: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/75655 How Art Invites Us to Look, Wonder, and Converse: http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/70719

Richard Anderson - Are designers becoming the new activists? http://panelpicker.sxsw.com/vote/71362

GLOBAL #CREATIVEMORNINGS COMMUNITY:

Check back soon!

Want us to add yours?

Just send us an email with your name, session title and the link - And put SXSW PanelPicker in the subject please. Or tweet it at us.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Through the Moongate 13 - 1983

Through the Moongate 13 - 1983 #ThroughTheMoongate #Ultima #OriginSystems #Commodore #Atari

Subscribe on Anchor | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe on Google Play | Subscribe on Spotify | Subscribe on TuneIn | Subscribe on Stitcher Podcast Topic(s) Andrea Contato’sThrough the Moongate, per its Kickstarter page, “illuminates the path of the Ultima games’ history and the creative people behind this landmark series. It also covers some of Origin’s other games, especially Wing Commander,…

View On WordPress

#Andrea Contato#Atari#Coleco#Commodore 64#Commodore VIC-20#Jack Tramiel#Ken Williams#Mattel#Origin Systems#podcast#Richard Garriott#Robert Garriott#Spam Spam Spam Humbug#Texas Instruments#Through the Moongate#Ultima 3#William Shatner

0 notes

Text

Seiko 6139 automatic chronograph for Apollo astronauts USAF Colonel James Irwin, born 1930, was selected as a NASA astronaut in April 1966. He had been a developmental testpilot for the Mach 3 interceptor/reconnaissance Lockheed YF-12, which preceded the SR-71 Blackbird. During the 1971 Apollo 15, Lunar Module Pilot Jim Irwin became the 8th man to walk on the Moon... an experience which changed his life! Post-NASA career, Irwin set up the "High Flight" evangelical foundation, with an outreach program for military families and wrote "To Rule The Night" about his historic adventure. This 1975 photo shows astronaut James Irwin wearing his personal Seiko 6139 automatic chronograph, a watch he had been wearing post-flight Apollo 15 since September 1971. Other Apollo era astronauts wearing the Seiko 6139 included William Pogue, Owen Garriott and Don Leslie Lind. (Photo: NASA/AP)

#Aviator#Astronaut#Seiko#automatic#chronograph#6139#montres#military#USAF#NASA#moonwatchUniverse#uhren#horloges#spaceflight#pilot watch#Zulu time

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review: Promised

Synopsis:

Warwickshire, England, 1812

Fooled by love once before, Margaret vows never to be played the fool again. To keep her vow, she attends a notorious matchmaking party intent on securing the perfect marital match: a union of convenience to someone who could never affect her heart. She discovers a man who exceeds all her hopes in the handsome and obliging rake Mr. Northam.

There’s only one problem. His meddling cousin, Lord Williams, won’t leave Margaret alone. Condescending and high-handed, Lord Williams lectures and insults her. When she refuses to give heed to his counsel, he single-handedly ruins Margaret’s chances for making a good match—to his cousin or anyone else. With no reason to remain at the party, Margaret returns home to discover her father has promised her hand in marriage—to Lord Williams.

Under no condition will Margaret consent to marrying such an odious man. Yet as Lord Williams inserts himself into her everyday life, interrupting her family games and following her on morning walks, winning the good opinion of her siblings and proving himself intelligent and even kind, Margaret is forced to realize that Lord Williams is exactly the type of man she’d hoped to marry before she’d learned how much love hurt. When paths diverge and her time with Lord Williams ends, Margaret is faced with her ultimate choice: keep the promises that protect her or break free of them for one more chance at love. Either way, she fears her heart will lose

Plot:

Margaret was looking for a marriage of convenience. She was already played the fool by her best friend’s older brother, whom she thought loved her, but only wanted her hand to get her dowry, as his mistresses on the side were the ones keeping him happy. With a failed engagement, Margaret hoped that attending a matchmaking party, she will find a man she could tolerate as a husband. Almost immediately she did, in the dark and handsome eyes of Mr. Northam. A rank, known to be a flirt, Margaret thought he was perfect, as he was someone she could hold a witty conversation with, but not allow access to her heart. If only the intolerable Lord Williams would leave her alone, as he tried to separate Margaret from his cousin. Lord William was even more intolerable than Daniel, her brother, at keeping Mr. Northam away from her. Where the night, nor their unexpected early departure next morning left Margaret engaged, that did not seem to matter as her father arraigned an unbreakable marriage with a man Margaret has never met. Or did not met well, as Lord Williams was the man who convinced her father to give him her hand, and the man her entire family, especially Daniel, was in love with. Being outwardly rude to Lord Williams, Margaret could only hope that Mr. Northam would ride in and rescue her from this terrible match. As Lord Williams insisted on tagging along after her daily life with her family, she could not help but notice the small things about him. His easy laugh, the wit in his eyes, how he let her speak to him in any way, and the muscles that can be seen beneath his shirt. Lord Williams was the man Margaret always thought she would marry, but also is the man that can destroy her heart, which she believes would not survive another hit. Can Margaret open herself up again to receive that kind of love, or should she keep her promised and find a man who will not love her, but tolerate her enough for a marriage?

Thoughts:

Leah Garriott gives us Margaret Brinton, a girl of marrying age, who was looking for convenience and not love. Already hurt once, Garriott made it clear Margaret was looking for her 1812 version of a “bad boy” who would not be loyal to her, but give her status as a married woman, so she would not be a burden to her family. Where Garriott was quick to reveal why Margaret was protecting her heart, the details do not seep in until later in the novel, as you can see how the two family’s act about the broken engagement when in pubic. Therefore, Garriott painted Margaret to see Mr. Northam be the cold bachelor willing to propose after a day, and Lord Williams the whinny cousin trying to get in the way. Where Lord Williams's first introduction made it seem that way, it was hard to get the reading behind why Margaret was rude to Lord Williams, especially after it was established that he was going to marry her when he visited her family home. Yes, he started off as a noisy character, it was hard to be on Margaret's side, when Lord Williams was being such a nice guy to her, and her family. Thus, why when Margaret made the switch from hate to love for Lord Williams, you almost wanted her to get rejected as a “serve you right” for being so rude for more than half the book. Garriott kept the plot moving fast, with a little twist and turns to keep the novel interesting. The best would be the conversations between Lord Williams and Margaret, as for the first half they were all insults, yet some left Lord Williams smiling, and others he was mad, despite that both conversations were just Margaret insulting him. The ending, not a shocker, but it was sweet, as our loveless girl finds love again, and not just for herself, but her family as well, as this book leads not to one marriage, but two.

Read more reviews: Goodreads

Buy the book: Amazon

0 notes

Text

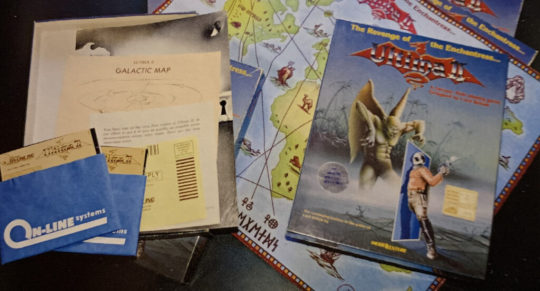

Through the Moongate 10 - Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress

Through the Moongate 10 - #Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress #Ultima2 #ThroughTheMoongate

Subscribe on Anchor | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe on Google Play | Subscribe on Spotify | Subscribe on TuneIn | Subscribe on Stitcher Podcast Topic(s) Andrea Contato’sThrough the Moongate, per its Kickstarter page, “illuminates the path of the Ultima games’ history and the creative people behind this landmark series. It also covers some of Origin’s other games, especially Wing Commander,…

View On WordPress

#Andrea Contato#Andrew Greenberg#Apple II#Atari 400#Atari 800#Chuck Bueche#CPCC#Denis Loubet#Dr. Cat#Keith Zabalaoui#Ken Arnold#Ken Williams#Laura Phillips#Monty Python#On-Line Systems#Paul Stinson#podcast#Richard Garriott#Robert Woodhead#Roberta Williams#Sierra On-Line#Softalk#Spam Spam Spam Humbug#Star Trek#Through the Moongate#Time Bandits#Ultima 2#Wizardry

1 note

·

View note

Text

Through the Moongate 09 - Sierra On-Line

Through the Moongate 09 - #Sierra On-Line #ThroughTheMoongate #Ultima #Ultima2

Subscribe on Anchor | Subscribe on iTunes | Subscribe on Google Play | Subscribe on Spotify | Subscribe on TuneIn | Subscribe on Stitcher Podcast Topic(s) Andrea Contato’sThrough the Moongate, per its Kickstarter page, “illuminates the path of the Ultima games’ history and the creative people behind this landmark series. It also covers some of Origin’s other games, especially Wing Commander,…

View On WordPress

#Al Remmers#Andrea Contato#Apple II#APPLE-OIDS#Asteroids#Atari#BASIC#Chuck Bueche#Colossal Cave Adventure#Commodore SuperPET#CPCC#Fortran#GE#Helen Garriott#Hudson University#IBM#Keith Zabalaoui#Ken Arnold#Ken Williams#Mistery House#MIT#Monty Python#MOS 6502#Motorola 6809#Oklahoma University#On-Line Systems#Origin Systems#Owen Garriott#podcast#Richard Garriott

0 notes