#Washington Burn Injury Attorney

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Back in August, I came onto Tumblr with a blaze of glory.

That was intentional. I wanted as many eyes on me as possible, as I told my story involving Jamie Benn and the Dallas Stars. I wanted folks to ask questions and poke holes. That was the intention!

I disclosed my brain-injury. You all tried to use that against me.

Now a group of you are trying to use "mental illness" as a means to bully me.

So, let's address some shit.

First, all of you mental health professionals overlooked the other plausible reason for my erratic behavior.

I was high. In August, I had 5 uterine tumors removed and was on a cocktail of drugs for most of August. Those drugs included opioids and Ativan.

Add to that my usual nightly cannabis, and I was high outta my fucking mind.

I said that back then.

But you all wanted to weaponize my disability against me.

You calling me "crazy" is crazy.

I legitimately worked at an insane asylum. A nuthouse. A psychiatric hospital. For about 5 years.

This wasn't a hospital with.

This was an entire military fort sized hospital operated by state of Washington.

On my caseload, I had a dude who stabbed his family to death, another who raped children, another who burned down apartment buildings with people inside, and other accused crimes.

I would sit on my assigned ward and listen to a woman bang her head for hours until she would split her forehead open. Another dude kicked his foot through a glass door. Others would collect their urine, shit, and blood so they could throw it at you when they entered a room.

I was put on multiple kill lists by people capable of killing. Had to be warned multiple times that there were credible threats, so I would have to go work off the ward until their grievance faded. Had male patients who would try to get me alone so that they could fondle or rape Mr.

Have you ever read a manifesto? I have. I read manifestos of the people on my caseload.

Have you ever read a middle-aged man's sexual fantasies involving children? I have. It was part of my job responsibilities to ensure these folks were ready to discharge back into the community.

I had to go before a judge or commissioner and say to them, "yeah, these dudes did some bad things, but they were treated, and I think they will be safe going forward".

Then, I spent months with these dudes, ensuring they were stable in the community because my name was on that court order.

I did all of that until a violent patient turned their violence on me. I wasn't even their intended victim. I put myself between them and an open door.

You can't tell me anything about a crazy person until you had your head thumped on by an institutionalized "crazy" person.

I meant it when I said I have an attorney.

I am in active litigation with my former employer!

All of these posts are discoverable in that case!

Including all of my posts to hockey players. My posts on Tumblr.

I gotta turn that shit over because of litigation.

So, again, to PuckingTea2, if she wants to take it there, I shall!

Because she is trying to use my diagnosis--the one that I am in litigation with-- to bully me off this platform.

All because she does not want to believe that multiple (cuz it's MULTIPLE now) hockey players would be interested in a 50 year old woman.

Bitch...go watch Bull Durham.

Stop romanticizing these men.

They ALL think with their dicks.

You think you know what makes their dick hard, but I KNOW. That's why they would scramble to fuck me.

An older woman who is confident about her body and unashamed of her sexuality.

Do you not understand how appealing that is to men who think with their dicks?!

Women have one idea of what men want but men have a different idea

You women are saying they wouldn't. But I already know they would!

And, I ain't naming names, but I got two muthafuckas vying for my attention right now. If you actually applied critical thinking skills and actually read my posts and who I tagged, THEN GO PEEP THE GAME STATS, you would figure out one of them. The other is retired.

I ain't naming the active player because he is in a relationship. I do not mess with taken men. I do not pouch. I am a girl's girl when it comes to men, so I ain't gonna respond to the bait.

But I will tell you why he would be interested.

He can tell I am a freak. And based on the recent asks submitted to @toxicgossip about this player, it makes sense.

He's a freak. You girls who hooked up with him are turned off by his sexual kinks!

I am not!

I was writing about my own kinks before I knew he had kinks.

I am not afraid to peg a dude. I will eat a man's ass. I will even consider fisting.

Now...does that help?

Do you need me to be clearer than that as to why a hockey player would want to fuck me?

Because they know they would have a good time with a confident older woman who is physically attractive and comfortable in her skin. They know the lights would be on with me.

If they wanted to try something different, to them, they think I could teach them as the older woman!

I am also intelligent with multiple degrees. I have an actual personality and am not a carbon copy of another woman. And, I am funny as fuck.

They see a fucking freak!

I don't expect you young white girls to see that shit!

They encounter a bunch of young pick me girls who don't have personalities either.

Which is why I advocated for brown-skinned or black girls or thick girls to approach them. They want something different!

Some of them are freaks looking freaks!

You guys are the ones confusing sex and romance. I always said this was about lust!

Some of these dudes got mommy issues, and I got 34DDs with a 28 inch waist and 40 inch hip.

You young girls get self-conscious about your scars, stretch marks, and flaws.

By the time we reach 50, most of us women work through those insecurities!

Does it appear to you that that shit would bother me?

In fact, I am over on Instagram talking about hormonal beards, but I am also talking about my insatiable sex drive.

When you hit perimenopause, all you think about is fucking.

To these young dudes who only want to fuck without commitment, I am the perfect woman!

Do you get it now?!

#ask auntie#ask me anything#nhl#black girl magic#nhl players#hockey#dallas stars#jamie benn#nhl playoffs#tyler seguin#sexuality#pansexual#sapiosexual#bd/sm kink

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

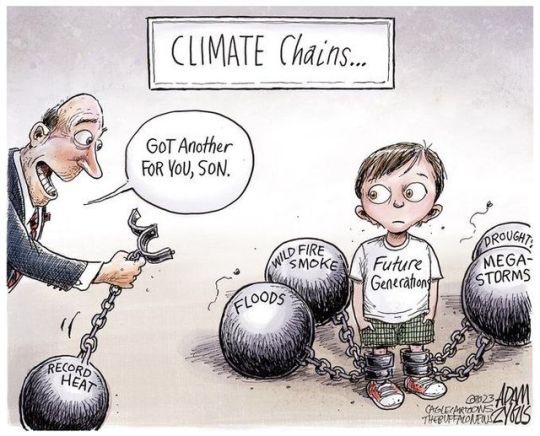

In a development that should give hope to all Americans, a group of Montana youth secured a court victory that invalidated a state law prohibiting the consideration of climate effects in the approval process for new energy projects. The victory is a watershed moment, even though the ruling is narrow. The Montana constitution guarantees its citizens the right to a “clean and healthful environment.” Prohibiting the consideration of climate effects of new energy projects is plainly antagonistic to that guarantee. A state court judge correctly granted judgment in favor of the young people of Montana. See Washington Post, Judge rules in favor of Montana youths in landmark climate decision.

The decision faces ongoing opposition from Montana’s attorney general, who called the decision “absurd” and promised an appeal that will end up in the Montana Supreme Court. No matter. The dam has broken and the victory by sixteen young citizens of Montana will inspire hundreds (or thousands) of additional suits. Some of those suits will succeed, encouraging more such suits. Fossil fuel lobbyists have ruled supreme in state legislatures for more than a century. The victory today is a very small step forward, but it is significant, nonetheless. It is particularly impactful because the plaintiffs were youths ranging in age from 5 to 22 years old.

The Montana litigation is part of a global litigation strategy to challenge climate change. The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School has published a report on climate change litigation across the world. See Global Climate Litigation Report | 2023 Review. Amidst the noise of the Trump indictment watch, good things are happening in the background.

[Robert B. Hubbell newsletter]

+

In 1972, after a century of mining, ranching, and farming had taken a toll on Montana, voters in that state added to their constitution an amendment saying that “[t]he state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations,” and that the state legislature must make rules to prevent the degradation of the environment.

In March 2020 the nonprofit public interest law firm Our Children’s Trust filed a lawsuit on behalf of sixteen young Montana residents, arguing that the state’s support for coal, oil, and gas violated their constitutional rights because it created the pollution fueling climate change, thus depriving them of their right to a healthy environment. They pointed to a Montana law forbidding the state and its agents from taking the impact of greenhouse gas emissions or climate change into consideration in their environmental reviews, as well as the state’s fossil fuel–based state energy policy.

That lawsuit is named Held v. Montana��after the oldest plaintiff, Rikki Held, whose family’s 7,000-acre ranch was threatened by a dwindling water supply, and both the state and a number of officers of Montana. The state of Montana contested the lawsuit by denying that the burning of fossil fuels causes climate change—despite the scientific consensus that it does—and denied that Montana has experienced changing weather patterns. Through a spokesperson, the governor said: “We must focus on American innovation and ingenuity, not costly, expansive government mandates, to address our changing climate.”

Today, U.S. District Court Judge Kathy Seeley found for the young Montana residents, agreeing that they have “experienced past and ongoing injuries resulting from the State’s failure to consider [greenhouse gas emissions] and climate change, including injuries to their physical and mental health, homes and property, recreational, spiritual, and aesthetic interests, tribal and cultural traditions, economic security, and happiness.” She found that their “injuries will grow increasingly severe and irreversible without science-based actions to address climate change.”

The plaintiffs sought an acknowledgement of the relationship of fossil fuels to climate change and a declaration that the state’s support for fossil fuel industries is unconstitutional. Such a declaration would create a foundation for other lawsuits in other states.

[Heather Cox Richardson :: Letters From An American]

#climate change#climate science#Robert b. Hubbell Newsletter#Montana litigation#clean and healthful environment#Global Climate Litigation Report#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters from An American

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fire of 1814

Assistant’s view of the Burning of Washington

———————————————————————

She hadn’t been expecting the burst of heat she felt across her torso.

Robin grimaces, hand coming to press against the burning sensation. There’s no obvious wounds or injuries,

They were spending time in Washington DC, there are things going on that they had to be close by for.

At this time at night, she’s long since shut the curtains, but the beaming orange-red light that slips through them causes her brow to furrow.

She slides the curtains open, and she can feel her eyes widen.

…

The buildings will bear no damage or scars, bear no pain in the time it takes to fix them.

But the fires she can see rage across the city line will not be as kind to her husband or son.

She doesn’t even bother with shoes, allowing the world to wrap around her as she starts to run, appearing in the streets of Government Buildings. The heartbeat of her love beat solidly in her chest, stuttering once every few minutes, leading her to him. DC was with his brothers, War– Robert– and Treasury– Oliver–, she could sense even from so far away, while State– Gideon– and Attorney General– Jack– were with the younger children back in Pennsylvania.

The three children were just slightly off the ocean shore, but Congress– her dear Adam, her Eternity; such a stupid, reckless man— was in the middle of it.

So she trusts her children and runs to save their father.

———————————————————————

Her knife cutting through clothes, matted by blood and stuck to skin like scabs.

The faint burning from her sons arm, wrapped in bandages she soaked and cooled to battle the temperature, even as he squirmed and writhed at the pain as she cleaned his blackened, bloody right arm. The injury had crept up to the side of his neck, but not far. Easily covered by clothes.

The sizzling skin along her husband's left arm, along the side of his neck, blackening the side of his face.

He doesn’t move, hardly shifts as she cleans the injuries and wraps him in the cold bandages.

War, her little Robert, is so much help when it comes to changing their clothes into something softer, less irritating on their skin.

They’re soon tucked into bed, and Robin leaves them for a moment, just a moment, to check in on her other children. To comfort and hold as they worry for their father and DC.

———————————————————————

26 hours.

That’s how long she had to hold her husband just under the ocean’s surface.

How long her sons had to hold their brother.

That’s how long it took the fires to go out, both on the streets and on their skin.

That’s how long the fires raged an not one State– not even Maryland, whose home is within eyesight of DC— showed up.

She knows they know about it. She knows they’d feel it if Congress passed, feel a sharp, sudden pain in their chests. She knows this, but she doesn’t know if they know it. For all she knows, they could think he’s dead.

But as she sits between the beds of her husband and son, gently cradling their youngest State, Louisiana, in the rocking chair…

…

She finds she can’t bring herself to care.

It’s been a few months since their parents and uncles stopped responding. She knows it hurts her Adam, breaks his heart, and he’s spent many nights in their bed wrapped into her embrace, crying, asking her why they were leaving them behind, why they no longer used the names they had gifted them– Adam and Robin?

It breaks her heart to have no answer for him. It shatters her heart when her Poppa, the one who gave her the name Robin, calls her Assistant. When her Pa, who built her birdcage, the one she still uses even after her first birds have passed, won’t even look at her outside of Meetings. When her Pop, who helped her name her birds, who taught her to care for them, won’t speak to her unless it’s a matter of business.

When they’re so quick to leave when they used to love staying for hours, visit her and her husband and her children– their grandchildren.

But…it’s fine.

It’s fine.

…

She’s fine.

#wttt gov#welcome to the table#wttt assistant#welcome to the table au#wttt#wttt dod#wttt dc#wttt dos#wttt treasury#wttt louisiana#only mentioned though#wttt attorney general#family ties au

4 notes

·

View notes

Audio

If you have lost a loved one as the result of the someone else’s negligence or actions, Caffee Accident & Injury Lawyers is here to assist you. Wrongful Death Lawyer in Renton have years of experience handling wrongful death claims so you can recover all of the compensation you deserve.

#Wrongful Death Lawyer in Renton#Washington Burn Injury Attorney#Renton Personal Injury Attorney#Renton Truck Accident Attorney#Personal Injury Lawyer Washington State#Car Accident Lawyer Renton WA#Renton Dog Bite Attorney#Washington Dog Bite Lawyer

1 note

·

View note

Audio

If you sustained serious injuries or killed in a pedestrian accident in Seattle, contact with an experienced Washington Pedestrian Accident Lawyer at Caffee Accident & Injury Lawyers, we will help you to recover maximum compensation for your injuries. Call today at (206) 312-0954.

#Washington Pedestrian Accident Lawyer#Washington Truck Accident Lawyer#Seattle Wrongful Death Attorneys#Washington Burn Injury Attorney#Washington Spinal Cord Injury Lawyer#Motorcycle Accident Lawyer in Washington#Seattle Pedestrian Accident Lawyer#Seattle Dog Bite Lawyer#Seattle Ride-Share Accidents Lawyer

0 notes

Text

Commercial Fishing Boats In Washington | Obryanlaw.net

The seas can be a dangerous place, and when it comes to maritime work injuries are sadly common. If you're a seamen who gets hurt on the job, O'Bryan can help. If you have been recently injured while working at an oil rig you may be entitled to financial compensation. Commercial Fishing Boats In Seattle and Accidents Attorneys.Man overboard may be the two most frightening words a maritime worker can hear, and every second can count when trying to save a life. Best Falling Overboard Lawyer. Offshore work, whether on an oil rig, a cargo ship, or anything in between, can be risky - but the Jones Act can protect you. O'Bryan Law explains how.

Best Jones Act Lawyers- If your employer asks you to write, speak or sign anything after an injury, be sure to talk to a Jones Act attorney first. Call us today and let us help. The maritime hub of all of New England, Boston is one of the busiest sports in the country - Commercial Fishing Boats In Washington. Best Boat Accident Lawyer. Seafaring injuries include slip and fall accidents, lifting, chemical, burn, and electric injuries. Call us today if you have been injured at sea. Types of Maritime Injuries & Accidents. Were you injured while working or playing on the waters of San Diego? O'Bryan Law has the knowledge, skill, and experience you need to get justice for your injuries.

Railroads carry a huge risk of accident or injury, but in the event of a railroad injury, O'Bryan Law can help you defend your rights and livelihood. Best Railroad Injury Lawyer. Even when on vacation, injuries aboard cruise ships are sadly common. O'Bryan Law can help defend your rights if you're injured onboard a cruise ship. Some accidents happen on boats regardless of how careful you are. In case you get injured from these accidents, know that you have a legal right to hire a maritime lawyer and Federal Employers Liability Act. You may be entitled to compensation if you are a fisherman and have been injured on the job. At O'Bryan Law we represent fishermen, not fishing companies. Commercial Fishing Boats In Seattle, Washington

0 notes

Photo

Transgender woman hopes suit against former employer will help othersFighting for Change: Part One, A New LifeTuesday, October 03, 2006By L.A. Johnson, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

First of a two-part series

Dannylee Mitchell was reborn on a Tuesday in April at the not-so-tender age of 40.

John Beale, Post-Gazette

Dannylee Mitchell stands in the foyer of her lawyer's Downtown office in March, before her surgery. "I think a lot of employers will see this and think twice, and it will make a difference," she said of her sex discrimination lawsuit. "They need to establish some policy."

Click photo for larger image.

Chat online about this story

Chat online with Post-Gazette staff writer L.A. Johnson about Dannylee Mitchell's journey tomorrow at noon. Go to

www.post-gazette.com/chat

.

Her journey to her authentic self took a long and circuitous route that was neither pretty nor smooth.

Four days after Christmas 2003, she crashed the Dodge Intrepid she was driving into the rear of a Ford Explorer parked on North Main Street in downtown Washington, Pa.

Stressed and depressed, she'd fallen asleep at the wheel in a company rental car. Police found her partially ejected from the car.

About two months earlier, she'd told her employer that she had a gender-identity disorder and would be transitioning from being a man to a woman.

"You don't know from the day you tell them you're transitioning whether you're going to have a job," says Dannylee, a Washington, Pa., native. "It weighs on you. You don't sleep. I was going on two and three hours of sleep a night."

Estrogen therapy was wreaking havoc with her emotions. Her family wasn't terribly supportive. She felt alone.

"I'd wake up at 2 in the morning, crying," she says. "I was just overwhelmed. Anxiety was at its peak."

Two days after the accident, on New Year's Eve 2003, she checked herself into Washington Hospital's psychiatric unit.

"I didn't want to go on anymore -- not a suicide attempt -- just exhausted," she says. "I was just burned out. Cooked. Done."

Severely depressed, she says she was having suicidal thoughts and spent a few days there under observation.

"It wasn't too long after I got out of the hospital that they fired me."

Dismissal of a salesman

Axcan Scandipharm Inc., a Birmingham, Ala.-based pharmaceutical company specializing in gastroenterology products, cited poor sales and inconsistencies in her reporting of the accident as reasons for her dismissal, she says.

Because she lost consciousness in the crash, she says she didn't realize there were two teenage boys in the Ford Explorer her car struck. All involved suffered minor injuries and were taken to the hospital from the scene. No one was charged in the accident, police said.

She believes she was fired because she told her employer she was going to become a transgender female. She filed a sex discrimination lawsuit against her former employer under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act.

In court records, Axcan Scandipharm maintains it did fire her in January 2004 for alleged willful misconduct but denies she was harassed by the company because of her sex and disability or suffered lost wages, emotional distress, embarrassment or humiliation.

The corporation's initial request to have the case dismissed -- arguing that Title VII protections don't extend to transsexuals -- was denied in February. The 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals is reviewing the corporation's request for an interlocutory appeal. That means the 3rd Circuit could grant the appeal, taking up the case itself, or deny the appeal, sending it back to federal court for trial.

Axcan Scandipharm's lawyer, Philip R. Voluck, had "no comment" on the case when reached by telephone last week.

John G. Burt, Dannylee's attorney, believes the case has parallels to other historic civil rights battles.

"Once upon a time we said black folks were three-fifths a person. Once upon a time we said women weren't smart enough to vote," says Mr. Burt, who took the case on a contingency-fee basis. "People like Dannylee are civil rights pioneers. They didn't want to be, but they are -- like the pioneers that wouldn't move to the back of the bus, the pioneers who said women have a right to vote. Just ordinary folk trying to live their lives."

Daniel Mitchell joined Axcan Scandipharm in February 1999 as a salesman. His performance evaluations consistently indicated he met or exceeded expectations, according to the complaint. In 2002, he was promoted to the position of photodynamic therapy specialist, marketing a photodynamic therapy drug (activated by light) to hospitals in Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey.

While his professional life was fine, his personal life was in turmoil. In August 2003, he found himself in the throes of a waning romance. His girlfriend at the time questioned his commitment to their relationship.

"She asked why did I have so much female attire in my travel gear?" Dannylee says. "She thought I was having an affair."

He wasn't. At that time, he simply felt free and safe to wear women's clothing only in hotel rooms when he was out of town on business. Her questions forced him to take serious stock of his life.

"It was a culmination of things, another failed relationship, my masculinity wasn't there in the relationship, always the question of whether I was gay," Dannylee says.

Right brain, wrong body

In September 2003, he went to the Persad Center, a licensed counseling center in Bloomfield serving lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. There he was diagnosed as having a gender-identity disorder, specifically gender dysphoria. As cliched as it sounds, all of his life he had felt like a woman trapped in a man's body.

A month later, his girlfriend moved out while he was away at a business meeting. And Dannylee continued looking for answers.

"This was not about anything sexual or getting some sort of sexual pleasure," she says. "This is about gender identity and who you are. What your computer program is. What your brain is. You have your internal program, but it doesn't always run the peripheral equipment properly."

People with gender dysphoria feel "in their head and between their ears that they are the opposite gender," says Judith DiPerna, a clinical therapist and transgender specialist at the Persad Center. "That person feels comfortable and at peace when they're dressed as the gender they believe they are between the ears."

Dannylee participated in the center's gender clinic, which is designed to help people sort through their gender-identity issues. She participated in group and individual counseling, received estrogen hormone therapy under a physician's care and began living, working and dressing as a woman full time -- which all is standard protocol for someone planning to undergo sex reassignment surgery.

In mid-October 2003, Dannylee began presenting herself as female to her business accounts after having first informed them and her employer of her plans.

"I told them what was going to happen, had to talk to the vice president of the company, had to tell my workforce of about 15 to 20 people," she says. "They called some of the hospitals to see if they were OK with me coming in as a female."

She worried whether she'd lose her job if one of her accounts objected, though none did.

She says one supervisor essentially asked: "Wouldn't it be easier to go work somewhere nobody knew you? Wouldn't it be easier to just leave?"

According to the complaint, a manager also told her not to discuss her sex change plans with co-workers and to be low-key and to use a separate bathroom at a national sales meeting.

She legally changed her name in November 2003. By mid-month, her supervisor told her she'd have more frequent job performance reviews because of her disorder, according to the complaint.

She doesn't dispute that her sales volume was poor around that time, but says the sales of everyone in her division were poor. Up to that point, her sales record had been commendable. She says a manager suggested her sales volume was down because of her disorder.

In court records, the corporation denies these allegations.

After Axcan Scandipharm fired her on Jan. 12, 2004, she filed for unemployment and initially was denied benefits. She appealed the ruling.

Her personal problems continued to mount.

In February 2004, after going to retrieve her dog from an ex-girlfriend's house, she was arrested and held in jail for two days on breaking and entering and theft charges. Dannylee claimed her ex-girlfriend's son gave her the dog when she asked for it.

"They threw Danny in jail, and the cops were yukking it up," says Joan Hoop, a friend who initially started out as her electrologist in Washington, Pa., and agreed to the interview only with Dannylee's consent.

"She was starting to dress as a woman and didn't have her polish then, and they made the big scene about her now dressing as a woman. Put [her] in an orange jumpsuit, took [her] clothes and put her in a holding cell up there."

Dannylee lost custody of the dog and the charges were dropped on the condition that she pay court costs and not have further contact with her ex-girlfriend or her ex-girlfriend's children.

In March 2004, she filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which initially said it didn't investigate claims related to transsexualism.

Extremely depressed during this period, she did try to commit suicide this time: She attempted to drown herself in a bathtub and later spent more time in a hospital psychiatric ward.

"You don't have a family. You have no money. Not sure how you're going to get through this transition," she says.

Around this same time, she won her appeal and started getting unemployment benefits.

In November 2004, the EEOC reconsidered the case and still found a transgender person was not protected under existing law, thus clearing the way for the federal lawsuit, which was filed in February 2005.

"First, it started off as me being [ticked] off at the world," she says. "But now when I look at it, it could do a lot of good for other people," she says. "If someone doesn't follow the perception of what [someone thinks] male or female should be, you can't discriminate."

Daniel Mitchell, shown in high school yearbook photo, always felt there was something wrong in his life. It took years of heartache, depression and courage to make it right.

Click photo for larger image.

Portrait of a woman as a young man

Dannylee first realized she was different when she was 5 or 6 years old.

"I didn't feel like a boy. I didn't act like a boy," she says. "A lot of people said I had feminine features. My gestures were feminine. A lot of people assumed I was going to be a gay man."

Elsa Edwards, a kindergarten and high school friend, remembers Dannylee as being hysterically funny. The two, who were both witty and involved in theater, were voted "Most Unique" by their senior class.

"We defied categorization. Still do," says Ms. Edwards, 40, of Washington, Pa. "Danny always had such a sweet nature, always very kind, considerate, un-guy like, not aggressive, not pushy, didn't bully anybody, but got bullied a lot."

They lost touch a few years after high school graduation.

Dannylee earned a bachelor's degree in biology at Thiel College and considered going into nursing. She worked in medical research for several years, managed a pet store for a national chain, worked for a national pet supply company, sold eyeglass frames in Philadelphia and New Jersey, then moved back to Pennsylvania in 1997, landing the job with Axcan in 1999.

Twice married -- in 1989 and 1996 -- when she was still living as a man, she tried being macho in relationships.

"That led to disaster after disaster in relationships, relationship failure and divorce because I 'wasn't man enough,'" she says. "I thought something was wrong with me and that love would cure me."

She now believes the only thing "wrong" with her was that she spent the majority of her life trying to be someone she wasn't.

Dannylee reconnected with her old friend, Elsa Edwards, in August 2004 at their 20th high school reunion.

Ms. Edwards remembers seeing a very attractive woman in a red dress and heels across the banquet hall. It took her a few seconds to realize that woman was the Danny she knew in high school.

"A lot of people didn't have a clue. They'd say 'Hi' to me and then they'd look over and say, 'Who is this?' and I'd say, 'Oh, you remember Danny,' and the jaws would drop," Ms. Edwards says.

After people got over the initial shock, they actually were very sweet, she says.

Ms. Edwards doesn't believe Dannylee's desire to transition was some flight of fancy, because Dannylee was always very deliberate.

"When I remembered Danny from high school, I could tell there was a lot of hurt there but a really courageous kind of sense of trying to do things that would work, trying to make things work," Ms. Edwards says. "I think Danny must have tried really hard to fit in to what people expected, but couldn't because it wasn't right for her."

Near broke and still emotionally fragile in the late fall of 2004, all Dannylee could do was continue to concentrate on becoming the woman she'd always felt she truly was.

It was time to correct what she called a "birth defect," that "deformity" between her legs.

TOMORROW: Making the transition from male to female.

First published on October 3, 2006 at 12:00 am

1 note

·

View note

Photo

OSHA Begins the Process to Issue Heat Illness Standard for Indoor and Outdoor Workplaces

Seyfarth Synopsis: OSHA is initiating a rulemaking to develop a heat illness standard.

For decades, federal OSHA has enforced occupational heat illness hazards through the Occupational Safety and Health Act’s General Duty Clause. OSHA has recently updated its Heat Illness Prevention Campaign materials to recognize both indoor and outdoor heat hazards, as well as the importance of protecting new and returning workers from hazardous heat. As OSHA continues to shift its enforcement focus to heat, it has begun the process to issue a heat illness standard. On October 27, 2021, OSHA issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) for the proposed standard.

The ANPRM provides OSHA’s overview of the issues concerning heat stress in the workplace and of measures that have been taken to prevent it, and seeks input from stakeholders on a number of questions during a designated notice-and-comment period.

According to the Agency, heat is the leading cause of death for all weather-related phenomena. Excessive heat exacerbates existing health problems like asthma, kidney failure, and heart disease, and can cause heat stroke and death if not treated. OSHA cites the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, declaring that exposure to excessive environmental heat, that has killed 907 U.S. workers from 1992- 2019, with an average of 32 fatalities per year during that period. In 2019, there were 43 work-related deaths due to environmental heat exposure. The BLS Annual Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses estimates that 31,560 work-related heat injuries and illnesses involving days away from work have occurred from 2011-2019, with an average of 3,507 injuries and illnesses of this severity occurring per year during this period.

The ANPRM examines the four state plans with heat illness regulations (California, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington), clearly showing an intent to model federal regulations on those deemed to be successful. Notably, none of the four pre-existing heat regulations agree on the appropriate threshold for determining what constitutes “hazardous” levels of heat. The ANPRM uniquely targets (1) the effects of climate change on occupational health, and (2) the inequitable effects of heat illness on disadvantaged demographic groups. OSHA provides data addressing disproportionate heat illness affecting minority employees, foreign born employees, low-wage-earners, and pregnant employees.

OSHA also notes that a large percentage of heat illness incidents occur in very small businesses with 10 or fewer employees.

A hurdle OSHA faces in developing a standard is that small businesses will have difficulty implementing both new engineering controls (air conditioning, providing shade) and administrative controls (closely monitoring the heat exposure of employees, cooling breaks because of limited employees, lengthy periods of acclimatizing to heat prior to beginning work).

Public comments on the ANPRM are requested on or before December 27, 2021. A heat illness standard could be the final outcome of this process, and interested parties should consider submitting comments to make sure their voices are heard during this rulemaking.

We have previously blogged on heat stress in the workplace. See “Water. Rest. Shade.” OSHA Campaign to Prevent Heat Illness in Outdoor Workers, Cool For the Summer, Avoid the Summer Heat! Sweat the Details of California's “Cool-Down” Periods and Avoid the Burn of Wage and Hour Class Litigation, and Cal/OSHA Drafts Rules for the Marijuana/Cannabis Industry and Heat Illness Prevention in Indoor Places of Employment.

For more information on this or any related topic, please contact the authors, your Seyfarth attorney, or any member of the Workplace Safety and Health (OSHA/MSHA) Team. ●

Seyfarth Shaw LLP Workplace Safety and Health (OSHA/ MSHA) Team: James L. Curtis Benjamin D. Briggs Adam R. Young Patrick D. Joyce A. Scott Hecker Ilana Morady Daniel R. Birnbaum Craig B. Simonsen

0 notes

Link

No group had ever picketed the White House before, according to Jennifer Krafchik, Acting Director, Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument. Many viewed women picketing during wartime as unpatriotic, so the police arrested 70 women on November 14, 1917. Given the choice of a $25 fine or incarceration, they chose jail. “Not a dollar of your fine shall we pay,” protested National Women’s Party co-founder Lucy Burns. “To pay a fine would be an admission of guilt. We are innocent.”

Officers then hauled the women to the Occoquan Workhouse, 25 miles south of Washington in Lorton, Virginia, where jailers fed the “law-breakers” maggot-laden food and stripped, dragged and clubbed them before they housed them in rat-infested cells alongside drunks and thieves. Guards manacled Burns by her hands to the overhead cell bars, forcing her to stand all night. When some of the suffragists went on a hunger strike, jailers force fed them raw eggs and milk through a tube inserted into their nasal passages. The women called this the “Night of Terror.”

Public exposure of the male guards’ abusive treatment galvanized public support for suffrage and created sticky political discomfort for Wilson, who still stonewalled. In 1918, he finally proposed that Congress pass the Susan B. Anthony amendment guaranteeing women suffrage as “a necessary war measure.” (To pressure Wilson to actively advocate for the amendment, the women built “watch fires” in Lafayette Park and burned his speeches.)

Five years earlier, 8,000 “uppity” women had upstaged President-elect Wilson’s inauguration when they marched down Pennsylvania Avenue carrying banners proclaiming “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” Their leader, attorney Inez Milholland, wearing white robes astride a magnificent white horse, invoked Joan of Arc. People on the sidelines, mostly men, hurled jeers and nasty insults, deriding these dogged women as “unwomanly,” “unsexed” and “pathological.” About 100 marchers were hospitalized after suffering injuries from the hostile onlookers. When Wilson disembarked at Union Station, disappointed at the size of his own greeting party, he asked where everyone was. “On the avenue,” came the answer, “watching the suffragists’ parade.”

#feimineachlink#capitalism#economics#sociology#equality#the 99%#human rights#inequality#HERstory#history#women in history#women's rights#women's liberation#anonymous was a woman#protest#politics#feminism#activism#fighting back#social movements#resistance#women

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If your loved one have been hurt in an accident in Renton.Our Renton Personal Injury Attorney at Caffee Accident & Injury Lawyers will be ready to help about your rights, legal options & what compensation is available to you. Call today at (206) 899-5415.

#Renton Personal Injury Attorney#Renton Car Accident Attorneys#Washington Personal Injury Lawyer#Renton Truck Accident Lawyer#Washington Burn Injury Attorney#Motorcycle Accident Lawyer in Renton#Washington Spinal Cord Injury Lawyer

1 note

·

View note

Audio

If your loved one was killed in a truck accident in the Seattle area or anywhere in Washington state, contact an experienced Washington Truck Accident Lawyer, we will fight for your justice and the compensation you deserve. Call our office Caffee Accident & Injury Lawyers at (206) 312-0954

#Washington Truck Accident Lawyer#Seattle Wrongful Death Lawyer#Washington Burn Injury Attorney#Motorcycle Accident Lawyer in Washington#Washington Pedestrian Accident Lawyer#Seattle Dog Bite Lawyer#Seattle Dog Bite Attorney#Seattle Ride-Share Accidents Lawyer#washington car accident lawyer#washington personal injury lawyer#car accident lawyer seattle wa

0 notes

Link

“All Hell Broke Loose.”

When Kishon McDonald saw the video of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of four officers from the Minneapolis Police Department, he could tell it was going to turn the country upside down. “I knew it was going to catch fire,” he said. McDonald, a former sailor in the U.S. Navy, watched over the following days as demonstrations against police brutality spread from Minneapolis to cities and towns across the country, eventually reaching Washington, D.C., where he lived. On June 1, he heard that people were planning to peacefully gather at Lafayette Square, a small park directly across from the White House, and decided to join them. By then, police had begun to attack and beat demonstrators in Minneapolis, New York, and others in states everywhere, escalating tensions as smaller groups broke into shops and set fire to police cars. But when McDonald arrived at Lafayette Square, he found a crowd of a few thousand people cheering, chanting slogans, and listening to speeches. Washington D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser had imposed a 7 p.m. curfew after clashes the night before, but that was still an hour away. “Everybody there was like, it’s alright, we’re going to be here until 7 o’clock,” he said. “It was a very good energy.” It wouldn’t be long before that would change.

Kishon McDonald, 39, originally of Cleveland, Ohio, poses for a portrait in his neighborhood in Washington, D.C., June 13, 2020.

Allison Shelley for the ACLU

In the days following George Floyd’s murder, President Trump had focused his attention on the relatively small number of people who had damaged property, threatening to use the “unlimited power of our military” and tweeting “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.” What the protesters gathered in Lafayette Square that day didn’t know was that he was planning to stage a photo opportunity at a nearby church that evening. Unbeknownst to McDonald, as he and the others chanted “hands up, don’t shoot,” the U.S. Park Police and other law enforcement agencies were just out of sight, donning riot gear and checking the weapons they would shortly use against the crowd to pave the way for the president’s walk to the church. At 6:30 p.m. — half an hour before Washington D.C.’s curfew — dozens of battle-clad officers rushed the protest, hurling stun grenades and firing tear gas canisters, rubber bullets, and pepper balls into the crowd. McDonald says there were no warnings, just an onslaught of violence. “All hell broke loose,” he said. As the deafening explosions from the stun grenades gave way to thick clouds of tear gas, terrified protesters began to run from the batons and riot shields that police were using to force them out of the square. “It was just straight fear. Everybody was scared and running for their lives,” he said. McDonald tried to plead for instructions from the advancing officers, asking them what they wanted people to do. Instead, one threw a stun grenade at him. “As it exploded, hot shrapnel hit my leg,” he said. “It felt like somebody put a cast iron skillet on my leg, it was just so hot. I started jumping up and down trying to get away from it, but shrapnel was going everywhere.” Suffocating tear gas enveloped him and the other protesters, making them gasp and cough as they ran down the street. “I saw a young boy, he must have been about 15, and he was choking a lot. Somebody put a shirt over his face and kind of ran him out,” he recalled. McDonald had seen enough. Bruised from being hit with riot shields and with his vision still blurred from the tear gas, he walked home. In a phone interview with the ACLU, he said that the experience had made him more wary of attending protests, but it also illustrated why he’d gone there to begin with. “It seems like everything is getting to be a military type thing in our society, and we were protesting to calm that down,” he said. “And the message we got is, ‘No, we aren’t calming down.’” “I hope someone gets held accountable,” he added.

****

Law enforcement officers clearing protesters from Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C., June 1, 2020.

Derek Baker

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, Americans poured into the streets to voice their condemnation of police brutality against Black people. The weeks that followed were a milestone in American history, with protests and displays of solidarity reaching towns as small as Cadillac, Michigan, and cities as large as Atlanta. As months of a painful COVID-19 lockdown gave way to incandescent fury over the killing of Floyd and the violent response of the Minneapolis Police Department towards the initial protests, a few people went as far as burning police precincts or destroying upscale shopping districts. The vast majority of protests, however, were almost entirely peaceful. Still, police departments across the country deployed staggering levels of violence against protesters. On social media, the world watched a near-instantaneous live feed of police in dozens of cities firing tear gas, rubber bullets, and other projectiles into protests, using pepper spray against protesters and journalists alike, and beating people with batons. This widespread and indiscriminate deployment of what are often called “less-lethal” weapons – LLWs – injured countless people, some severely. In Austin, Texas, 20-year-old college student Justin Howell suffered a skull fracture after being shot in the head with a “beanbag round” filled with lead pellets. Linda Tirado, a journalist and photographer, lost her left eye to a “rubber bullet” fired by police in Minneapolis. In Seattle, 26-year-old Aubreanna Inda nearly died after a stun grenade exploded next to her chest. According to Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s Trone Center for Justice and Equality who focuses on police practices, this widespread and violent use of LLWs during the George Floyd uprising was an attack on the protesters’ constitutional right to free speech. “There’s just no justification under the existing Fourth Amendment framework for the use of these weapons,” he said. “And it’s happening over and over again, with patterns that are so similar across the different cities.” For years these weapons were referred to as “non-lethal.” But in practice, they have a long history of causing serious injuries and deaths. A 2016 report by the International Network of Civil Liberties Organizations analyzed 25 years of available data on the use of LLWs by law enforcement across the world. It found that between 1990 and 2015, “kinetic impact projectiles” — a category that includes rubber bullets and beanbag rounds — caused at least 1,925 injuries, including 53 deaths and 294 instances of permanent disability. Tear gas, which is banned for use in warfare under the 1925 Geneva Protocol, injured at least 9,261 people over the same time period, including two deaths and 70 permanent disabilities. The report also found that LLWs are most commonly used to stamp out political protests and shut down aggressive demands for greater rights. According to Takei, even the term “less lethal” downplays the damage they can inflict. “Beating somebody with a baseball bat, as long as you’re not hitting them in the head or other sensitive areas of the body is ‘less lethal,’ but it’s still incredibly violent,” he said. During the civil rights and anti-war demonstrations of the 1960s, police used tear gas and other LLWs extensively to disrupt and disperse protests. But after three federal commissions found that abuse of those weapons provoked aggressive responses by protesters and contributed to a cycle of violence, they fell out of favor with U.S. law enforcement as a method of controlling crowds. According to the Marshall Project, in subsequent decades, some police departments adopted a “negotiated management” approach to protests, working with organizers in advance to establish ground rules meant to prevent violence. But any movement toward de-escalation evaporated in the wake of large anti-globalization protests that took place during a 1999 World Trade Organization meeting, in an event that would come to be called the “Battle for Seattle.” In a prelude to how many police departments would later approach the George Floyd uprising, Seattle police attacked the mostly non-violent protesters with LLWs, provoking a handful to respond aggressively in kind. “The response of a lot of police departments after that was, well if some people won’t act as predicted, we should have a hyper-aggressive response for everybody,” said Takei. “But when police adopt this type of response to Black-led protests against police violence, they are repeating a pattern of brutality that goes back to the origins of American policing in Southern slave patrols.” Now, as outcry over the indiscriminate use of LLWs against Black Lives Matter protesters mounts, some municipalities are weighing restrictions on the weapons. After the ACLU sued the Seattle Police Department in early June for its violent response to protests in the city, a judge ordered police there to cease using the weapons against peaceful demonstrators, saying they had “chilled speech.” Days later, Seattle’s city council voted unanimously to prohibit their use against protesters. Legislators in Atlanta and other cities have also proposed similar bans. The ACLU spoke to a number of people who were attacked with LLWs by police during demonstrations over George Floyd’s murder in recent weeks. This is how they described their experiences.

****

Gabe Schlough at his home in Denver, Colorado.

Jimena Peck for the ACLU

Gabe Schlough wasn’t surprised that the Minneapolis Police Department had killed another one of its Black residents. He lives in Denver now, but he’d gone to college years earlier in Minneapolis. Just before he graduated, he’d been shot in the back with a stun gun by police who entered his home and tried to arrest him in a case of mistaken identity. Schlough had been invited to a protest at downtown Denver’s Capitol Building that night, but instead he decided to drive his motorcycle up into the mountains with a friend. “In one of the areas where people were hiking and snowboarding and skiing down I saw three Black people, and I was just fucking happy,” he said. “I was like, thank God not every Black person thinks they need to be at the Capitol right now.” But when he got back home later that night and saw images of the Denver Police Department’s response to the protest, he felt his blood start to boil. “We can’t even give doctors and nurses facemasks, but we can give our police access to militarized weapons that are exceedingly more expensive and hard to create than the protective mechanisms we need for health care workers,” he recalled thinking. Schlough has a degree in public health anthropology, and he’d worked in health care across the world, including a stint in an Ebola clinic in Sierra Leone. He had medical training and had participated in protests before, so he decided to defy the curfew along with a few friends to see if he could offer help in case anyone got hurt. Donning his face mask along with sunglasses to protect his eyes, Schlough set off towards the Capitol Building. When he arrived, he saw a crowd of two or three hundred people facing down a line of police. “They were standing just a little bit more than shoulder to shoulder apart with full riot gear, with their face shields and full protective armor on,” he recalled. Schlough moved up toward the front of the crowd. Behind him, somebody set a pile of garbage on fire. That was all the police needed to begin their advance. As they moved forward, they shot canisters of tear gas into the crowd and tossed stun grenades. “I was going around and telling people who didn’t have eye coverings to watch their eyes and protect their face,” he said. “Just running up and down the line and getting people educated, like this is happening and this is what you need to know.” As a canister of tear gas landed next to him, Schlough bent down to try and cover it with a traffic cone so the gas wouldn’t spread. Suddenly, he felt sharp blows to his face and chest. “A shock hit me and my head popped up,” he said. “I felt like somebody had punched me in the chest.” Schlough had been shot with rubber bullets, although he didn’t know it yet. As he fell back further into the crowd of protestors, someone told him he was bleeding. “You need to go to a hospital,” they said. “Your face is falling off.” Another bystander pulled out his phone and showed Schlough his injury. The bullet had left a gaping wound on his chin, and blood was pouring down onto the front of his shirt. In retrospect, Schlough says he thinks he was specifically targeted, and that police knew exactly where they were aiming when they shot him. He and a friend left and started walking toward a nearby hospital where he did volunteer shifts. But when they arrived, Denver police were also there. “There were cop cars there and more pulling up, and I understood that it was not a safe place for me to get treated because of the amount of police presence there,” he said. Instead, Schlough had to drive outside Denver to be treated at a different facility. Doctors cleaned his wound and gave him 20 stitches. More than a week later, part of his chin is still numb. He worries that he may have suffered nerve damage. Last Christmas, while visiting his mother in Wisconsin, he says one of her friends asked him what the most dangerous place he’d ever been was. “I told her that I’m the most scared when I’m in the U.S. and around a police officer,” he said. “Because I know that no matter who I am or what I’ve done in my life, I can be shot and killed, and nothing will matter.”

****

Toni Sanders, 36, poses for a portrait at her home in Washington, D.C., June 13, 2020.

Allison Shelley for the ACLU

Toni Sanders arrived at Lafayette Square along with her wife and 9-year-old stepson in the late afternoon of June 1 – the same day that Kishon McDonald was there. Their son — identified in court papers as J.N.C. — had been watching the news over the preceding days, and the family had been having difficult conversations about George Floyd and why there was unrest rocking the country. “We spoke about Aiyana Stanley-Jones and Tamir Rice, and people right here in D.C. who had been killed by Metropolitan Police — Raphael Briscoe, Terrence Sterling, Marqueese Alston, and explained to him that was why people were protesting,” Sanders said. He said that he’d like to accompany Sanders and his mother to Lafayette Square. “I assured him that it would be safe because it was a peaceful protest and that we would leave before the curfew started,” she said. At first, she was glad that she’d agreed to bring him to what felt like a “community environment.” People in the square were passing out snacks, chanting, and kneeling in solidarity with George Floyd. “Everything started out wonderful, it was a great experience,” she recalled. “We even took a picture when we first got down there just to remember the date we all stood together.” Then, the attack began. “I just heard the loud bah bah bah bah, and smoke started to fill the area.” Sanders was immediately terrified for her young stepson. “I just started screaming to my family, run, run, run,” she said. The three sprinted away from the sound of detonating stun grenades and the shrieks of injured protesters. After making it a few blocks away, they stopped to catch their breath and check in with one another. “He said, ‘I can’t believe I just survived my first near-death experience.’ And it literally broke my heart because there’s honestly nothing I could say to him. I couldn’t tell him this wasn’t a near-death experience.” Sanders was furious that police hadn’t warned protesters to disperse before violently clearing the park. If they had, she said, she would have quickly brought her stepson to safety. “If we had been asked to either move back or leave, we would have. We would not have protested that because we have a child that we must look out for,” she said. After the attack, Sanders’ son expressed anger and hurt over how police had treated them. Sanders had refused to allow the experience to scare her away from attending protests, but now when she left the house he would ask her to promise that she wouldn’t die. “I wanted to show him that even though you’re afraid, if someone is trying to take your rights and do you wrong, you have to stand up for who you are and what you believe in,” she said. The couple decided to put him into therapy to work out how that day affected him. Sanders says he told his therapist that he thinks that it’s the end of the world now, and that the government is at war with Black people. “Now we have to have uncomfortable conversations with him about systemic racism, overt racism, covert racism,” she said. “And it’s horrible to have to take that innocence from him.” Along with Kishon McDonald, Sanders is one of two plaintiffs in an ACLU lawsuit over the attack on Lafayette Square protesters that day. Over the phone, she recites the poem ‘If We Must Die’ by Claude McKay. We’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back! “We’re here to show you that we’re still citizens, and we’re going to exercise our rights, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

****

Alexandra Chen, a law student at Seattle University and a plaintiff in the lawsuit Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County v. City of Seattle, poses for a portrait in Seattle, Washington on June 15, 2020.

David Ryder for the ACLU.

On May 30, first-year law student Alexandra Chen marched to a police precinct in downtown Seattle along with a few hundred other demonstrators. It was the second protest she’d attended, the first being the day before. When they arrived at the precinct, there were police in riot gear out in front, with others standing in the windows and watching the crowd from above. “People were clearly agitated, but I didn’t see anyone really try to push the ticket,” she said. “Folks were just crowding around and leading chants.” A few scattered water bottles along with a road flare were thrown at the precinct, but aside from that, Chen said nobody in the crowd was signaling that violence was coming. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘You know, this would be a great opportunity for someone to come out with a megaphone and make a statement about how you understand why we’re so angry and you want to work with us on how to fix this,’” she said. Instead, just like in Washington, D.C., Denver, and dozens of other cities, the Seattle Police Department began to throw stun grenades and tear gas into the crowd. “There was no warning at all,” she said. “It was just absolute chaos.” When the first stun grenade detonated near her, she felt a “deep percussive feeling” in her chest. People began to scream and run as tear gas filled the street. As she and her friend tried to move away from the precinct, she noticed another young woman desperately trying to find fresh air. “There was a gap in a wall that was about six to eight inches between buildings, and she was trying to escape the gas. It looked like she was trying to crawl into that space, and you could hear her retching,” she said. Tear gas is by its nature indiscriminate. It can’t be controlled or targeted to incapacitate specific people. As soon as a canister or grenade is launched, it becomes the property of the wind. Young and old alike are subject to its effects, which Chen says go from “uncomfortable to intolerable in a short amount of time.” Chen says that when the group first arrived at the precinct, nearly everyone was wearing masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19. But after the tear gas was fired, people began to rip them off as they choked, coughed, and gasped for air. “First, you think to yourself, “Okay, I can tolerate this,’” she said. “You don’t really expect that it’s going to get worse, but it does. It moves deeper into your face and once it gets into your sinuses, everything it touches burns.” All around her, people were calling out for their friends and loved ones through the thick smoke. “It was hard to tell which direction to run because when they threw the canisters, they rolled down the hills spewing tear gas the whole way. So effectively, you had not just the immediate area in front of the police station gassed, you had the whole block, and when you’re in the middle of it, you can’t tell where it ends,” she recalled. After Chen and her friend emerged from the cloud, a medic nearby helped flush her eyes out with water, and the two walked back to her apartment. She is now a plaintiff in an ACLU lawsuit brought against the Seattle Police Department over its use of tear gas and other LLWs. “I don’t care what they want to say about how people are violent,” she said. “What I saw was peaceful protesters met with an immediate and overwhelming show of force to get us to disperse.”

****

Jared Goyette stands in front of the remains of the Minnesota Police Department’s Third Precinct.

Brandon Bell for the ACLU

Jared Goyette moved to Minneapolis five years ago to be close to his daughter. As a journalist, he’d covered protests over police brutality before — first at the Mall of America during the Ferguson uprising, and then later after the killing of Philando Castile. Over the years, he’d developed ties to the city’s activist community, and in the hours after the video of George Floyd’s murder was released, his phone began to buzz. “I started getting texts from different Black activists in the Twin Cities,” he said. Goyette could tell that Floyd’s killing would lead to unrest, and before long national news outlets began reaching out to ask for his help covering the story. On May 27th, two days after Floyd’s death, Goyette heard the sound of helicopters buzzing over the Minneapolis Police Department’s Third Precinct. The Precinct had already become a flash point for demonstrations, and Goyette decided to head to the area to see what was happening. “When I started surveying the scene, it was entirely different from anything I’d seen in my previous years of covering protests against police violence in Minnesota,” he said. Several hundred people had surrounded the precinct, and officers in riot gear were standing on the roof firing tear gas and rubber bullets at them. Goyette had his camera and notepad with him and, along with other journalists there, was visibly covering the standoff in his role as a reporter. He saw that a young man had been shot in the head with a ballistic projectile, and moved towards him to try and see if he could do anything to help. “He was just writhing on the ground in clear, severe pain,” he said. “People were screaming, ‘Call 911.’” Goyette noticed that his ten-year-old daughter had texted him to ask where he was, so he moved off to the side to text a response. Suddenly, he was on the ground. “There was a searing pain in my eye,” he recalled. “It wasn’t like I was hit and then I fell, it was like I’m standing and then wait, I’m not standing and everything is black.” Goyette had been shot in the head with a rubber bullet. His nose was bleeding and his eye was swollen and black. People moved towards him to help, but tear gas began to flood the area.

Policing the Press: A Journalist on the Frontlines

Journalists covering protests against police brutality across the country are facing an influx of violence, suppression efforts, and arrests by police…

Listen to this episode

He managed to woozily make his way to safety, and after gathering his composure for a few minutes, found his car and drove home. Initially, he didn’t think he needed medical attention, but his girlfriend told him he had to visit a community clinic. Health workers there said that if he’d waited longer for treatment, he might have lost sight in that eye. He says he thinks it’s unlikely that officers didn’t know he was a journalist when they shot him. “I wasn’t running, I wasn’t chanting,” he said. “Protesters aren’t normally dressed in a dress shirt and slacks.” Goyette wasn’t the only journalist who was targeted by Minneapolis police that week. Many documented being pepper sprayed despite clearly identifying themselves as reporters. Others were arrested, gassed, threatened, or — like Goyette — shot with rubber bullets. In a clip that went viral, CNN reporter Omar Jimenez was arrested on live television, despite the fact that he was accompanied by a full news crew with cameras and sound equipment. “I worry that the sort of ‘fake news’ doctrine is leading to journalists being targeted,” said Goyette. “And this is the first time that I think we saw that at a systematic scale.” On June 3rd, the ACLU filed suit against the City of Minneapolis over the attacks on journalists that were carried out by MPD officers. Goyette is the lead plaintiff in the case. “I don’t want this to come out wrong, but I feel angry, and a little bit afraid,” he said. “The Police Chief made an apology to journalists who were fired upon, but there wasn’t anything behind that apology. No promise to investigate and hold people accountable, nothing other than a sentimental gesture. And I fear that people are just going to move on.”

Published June 23, 2020 at 11:42PM via ACLU https://ift.tt/3eu2a5Y

0 notes

Text

Common Types of Truck Collision Injuries

It seems like every day we hear about a trucking collision on the roadways we travel daily. All too often severe injuries result to those involved. Below, we have compiled a list of the most common injuries that drivers experience after being hit by a tractor-trailer.

Head and Brain Injuries

Head and brain injuries are some of the most common and most devastating injuries caused by collisions involving large trucks. Traumatic brain injuries, also known as TBIs, are caused by the impact of the inside of the skull on the brain and frequently coincide with lacerations to the scalp or face, blunt head trauma, and concussions. Small lesions on the brain are sometimes indistinguishable in CT scans and X-rays. Because of this, specific types of imaging, such as MRIs or high-resolution CT scans must be used to locate these lesions. Symptoms of TBI include difficulty concentrating, trouble sleeping, mood and/or memory problems, and headaches. Sometimes called the invisible injury due to the difficulty in showing TBIs using imaging, TBIs and head trauma injuries are extremely serious and can severely negatively impact one's life for years after a collision.

Back and Neck Injuries

The impact of a massive tractor-trailer colliding into a small passenger vehicle can be so powerful these collisions commonly end in fatalities. Those lucky enough to survive these collisions often suffer damage to the soft tissues in their back and neck, tendons, muscle strains, and ligament injuries. Bony structures in the spine, called vertebrae, protect the spinal cord. In between each vertebra are rigid cartilage cushions known as discs, allowing ease of motion and flexibility between the bones in the spinal column. Yet, when injured, these discs can, unfortunately, bulge, leave, or collapse (become fully herniated). Once this happens, the vertebrae's area narrows, and the nerve bundles become pinched, leading to severe and debilitating symptoms that can result in paralysis or worse. Back and neck injuries are some of the most common injuries suffered in any collision and they must be treated properly for injuries to recover.

Broken Bones

While some broken bones can heal without significant medical intervention, this is not the case for all broken bones. In severe cases, broken bones require surgeries that leave the patient in excruciating pain with pins, screws, and rods inserted into their bones. Broken bones can either be non-displaced (cracked but intact), displaced (entirely fractured and out of their regular position), or compound (bone puncturing through the skin and exposed). In these cases, the fractures may cause internal bleeding, nerve damage, permanent deformity, and infection if they are not immediately treated.

Lacerations

Various parts of a car or truck, including sharp metal, door frames, shattered glass, dash panels, and hard plastic interiors, can cause puncture wounds and deep lacerations on passengers. Unfortunately, many victims of trucking collisions must live with disfiguring scars even after their wounds heal. The head and face are the most common areas passengers suffer lacerations and puncture wounds because they are the most exposed part of the body. Even after a wound heals, many times a scar will serve as a lifetime reminder of the collision.

Burns

Sometimes the impact of a truck collision can cause fires or explosions. Because of this, some survivors suffer from severe burns and, sometimes, infection. Friction burns may also occur when a person scrapes against the inside of the car, or they are ejected and scrape the pavement. No matter the case, burn injuries are complicated to treat and sometimes require surgery. These burn injuries form distinct scars that survivors carry with them for life.

Spinal Injuries

One of the most severe common types of truck collision injury is a spinal cord injury. This injury occurs when the spinal cord is severed or damaged in any way. These types of injuries can lead to partial or total paralysis. Because the spine is the channel in which the brain communicates to the rest of the body, spinal injuries can sometimes result in survivors not being able to walk and even quadriplegia (the loss of function in all extremities). These patients will often require help eating, bathing, speaking, and breathing.

Wrongful Death

Unfortunately, many highway fatalities are the result of collisions involving large commercial trucks. While these cases are complex and can require court proceedings, it is important that we as a society hold responsible those who cause injuries to others. Doing so allows the surviving family members to cover for funeral expenses, medical costs, loss of income, and the general emotional pain they will endure from losing a loved one.

If you or a loved one have suffered any of these truck collision injuries, give us a call today.

Located in Seattle and Mercer Island, Washington, Gosanko & O'Halloran is a team of highly skilled attorneys available to help you today. Our legal team can answer any of your questions during a free legal consultation, and help you understand your options before you make a decision. To schedule a legal consultation today with one of our lawyers, call our law firm at 206-275-0700.

0 notes

Link

3M MILITARY EARPLUG LAWSUIT LAWYER- TINNITUS & HEARING LOSS

When a government contractor sells the government a product that does not work, they are usually subject to large penalties. When this product is one that is used by members of the military as military hearing protection, it can subject the company to additional liability. This liability manifests itself through the form of military hearing protection product liability lawsuits. 3M has recently settled a 3M Earplug lawsuit filed by the government that it made false claims in supplying the military with these military hearing protection combat earplugs. This claim was originally filed by a whistleblower on behalf of the U.S. Government.

Military earplug lawsuit

Now that the military earplug lawsuit settlement has been entered into, the first 3m Combatarms earplug lawsuits have been filed by former service members against the company for injuries suffered through use of the defective 3m earplugs. There are currently tens of thousands of defective earplug lawsuits pending in the Northern District of Florida.

142,000 MILITARY EARPLUG LAWSUITS FILED IN FEDERAL COURT

The Multidistrict litigation lawsuit is known as, “IN RE: 3M Combat Arms Earplug Products Liability Litigation.”

There are currently 142,527 lawsuits pending (as of Aug 17, 2020) before M. Casey Rodgers (Chief Judge, USDC) in MDL -2885.

WHAT ARE THE CRITERIA TO BE IN THE 3M EARPLUG LAWSUIT?

3M Aearo Technologies Earplugs / military hearing protection Criteria:

Claimant Served in the Military between 2003 and 2015 and used the 3M or Aearo Technologies “Dual-ended Combat ArmsEarplugs–Version 2”

Military ear plugs claimant suffered partial or full hearing loss and/or tinnitus (ringing of the ears)

COMBAT ARMS LAWSUIT UPDATES

Update- 7/27/2020- “3M Not Entitled to Governmental Immunity In Defending Lawsuit Over Combat Earplugs, Judge Says In the first substantive ruling to come out of the Multidistrict Litigation over allegedly defective earplugs, U.S. District Judge M. Casey Rodgers refused to grant summary judgment based on 3M’s government contractor defense.” 3m failed to show “exceptional circumstances” in order to file an immediate appeal. 3M asserted that they were entitled to governmental immunity from civil lawsuits because they operated under a duty to the federal government. United States District Judge Casey Rodgers of the Northern District of Florida denied 3M’s bid to dismiss thousands of lawsuits filed in the MDL. Justice Rodgers determined that 3M’s arguments were effectively bogus by citing a US Supreme Court decision in 1988, Boyle v. United Technologies Corp. “Defendants have identified no authority — none — in which a defendant having no design obligation to the federal government nonetheless enjoyed the benefit of the government’s sovereign immunity pursuant to Boyle.”

5/7/2020- “Pensacola, FL- Recent unsealed depositions confirm that 3M officials knew their Combat Arms earplugs were defective and that information was withheld from the military. Further, some 3M employees didn’t believe that soldiers “needed to know how to adjust” their earplugs so they would fit properly. A federal judge in Pensacola on April 20 made hundreds of documents public. Besides depositions, these documents include emails, memos and receipts related to the Defense Department’s purchase of 3M’s earplugs between 2003 and 2015. In the depositions, Elliot Berger, division scientist for 3M’s Personal Safety Division, acknowledged an internal memo that said “ the existing product has problems unless the user instructions are revised,” reported Bloomberg Government, a division of Bloomberg Industry Group. As well, when Timothy McNamara, 3M’s sales manager for the U.S. Midwest was asked during his deposition whether soldiers were entitled to know that the way the company tested the earplugs wasn’t the same way that service members were instructed to use them, he answered “I don’t believe so.” Lawyers and Settlements

“Despite visiting military bases frequently, McNamara said that he never shared how to use the earplugs in order to achieve the advertised noise-reduction rating, reported Bloomberg. Plaintiffs argue that 3M knew from testing that the earplugs were too short to fit properly into an ear canal and could loosen in a way that was imperceptible to the wearer. 3M modified the design but the military was given information to show that the modification was for people with very large ear canals. Other testing results were conducted before the earplugs were shortened to fit into a carrying case, according to court documents.” Id.

4/24/2020- “U.S. combat troops were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan with protective earplugs that they may not have known how to fit properly, and some employees of manufacturer 3M Co. didn’t believe soldiers needed to be told how to adjust the devices, according to unsealed depositions by company officials in a mass tort lawsuit. In the depositions, reviewed by Bloomberg Government, 3M officials couldn’t point to documents or calls in which U.S. military representatives were told that the earplugs can imperceptibly loosen. Yet internal memos acknowledged “the existing product has problems unless the user instructions are revised,” according to Elliot Berger, division scientist for 3M’s Personal Safety Division. In addition, Timothy McNamara, 3M’s sales manager for the U.S. Midwest, said he didn’t “believe so,” when asked during his deposition whether soldiers were entitled to know that the way the company tested the earplugs—and achieved a high noise reduction rating—was different than the way service members were instructed to use them. McNamara, who visited military bases on a regular basis, also acknowledged he never shared how to use the earplugs in order to achieve the advertised noise-reduction rating.” Bloomberg Government

4/2/2020- “3M Co has moved to dismiss thousands of lawsuits by service members and veterans alleging it sold defective earplugs to the military, saying their state-law claims were based on a design element mandated by the U.S. Army. 3M in a motion filed in federal court in Pensacola, Florida on Wednesday said the military approved precise specifications for the company, a contractor, to follow and took responsibility for training service members how to properly use the earplugs.” Reuters

5/29/19- “On May 22nd Judge M. Casey Rodgers issued Pretrial Order No. 7 naming the leadership for the plaintiffs in the 3M Combat Arms™ Earplugs MDL. Selection was made from among 190 applicants. Bryan Aylstock was named Lead Counsel, supported by Shelley Hutson and Chris Seeger as Co-Lead Counsel. Brian Barr and Michael Burns were named Co-Liaison Counsel. These five lawyers, along with Evan Buxner, Tom Cartmell, Mark Lanier, Roberto Martinez, Paul Pennock, Adam Wolfson and Genevieve Zimmerman will comprise the Executive Committee.”

WHAT ARE 3M COMBAT EARPLUGS?

3M’s combat earplugs were intended to prevent loud noises from entering soldiers’ ears and causing damage. Combat often subjects military forces to noises that are literally deafening. If the combat ear plugs do not work, soldiers can suffer permanent and debilitating hearing loss complications or tinnitus. The latter condition is when there is actual ringing in the ears or the sensation of ringing.