#WANTED MARCEL DUCHAMP

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

scopOphilic_micromessaging_1197 - scopOphilic1997 presents a new micro-messaging series: small, subtle, and often unintentional messages we send and receive verbally and non-verbally. (2013)

#scopOphilic1997#scopOphilic#digitalart#micromessaging#streetart#graffitiart#graffiti#brooklyn#Manhattan#nyc#photographers on tumblr#original photographers#ArtistsOnTumblr#2013#ART RULES THE STREETS#THESE ARE TWO#WANTED MARCEL DUCHAMP#DASANI AIR#THE DARDYS#FISCHEN

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Artnet caption on this image from the story of Barbara Visser's documentary about questions of authorship of Duchamp's Fountain is perfect.

#Still from Barbara Visser Alreadymade (2023). © Barbara Visser / Tomtit Film & VPRO.#marcel duchamp#baroness elsa vonfreytag-lohringhoven robbed again#while i wanted elsa to be the author of fountain the guys with the theory are rightwing trolls tryna destroy conceptual art

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Absurdist Art, Anti-Art, and Meaning as Applied to Elden Ring

Going to pin down my thoughts on some of the most abstract concepts of the game: "What is the Greater Will?" and "Why did Marika Shatter the Elden Ring".

But first a long tangent on the Absurd.

Absurdism is a philosophy that applies to the universe - the one that we are living in - having no intelligent creator and thus humans must grapple with living in a meaningless world.

The concept of a meaningless universe is fundamentally different from the microcosm of a video game, or any project requiring a lot of coordination to assemble. The universe doesn't care about people. But people DO tend to care about other people. It is fact that an intelligent team of people created Elden Ring, and intelligent people created the structure of the hardware that the software engineers program, and intelligent people developed the material sciences to the point that the hardware could be mass produced. So it is entirely possible to proceed with an assumption that human beings have selected language and visual elements with intention as well. That there is meaning and internal consistency to be found once the correct perspective is applied to the problem.

Motif of Trees in Pots - Weeping Peninsula and Belurat

Once characters in a story start talking and debating about their gods and creation myths, they cannot be incorrect about the existence of a Creator god - because they are inherently creations and have an author actively deciding the boons and hardships they receive. They can only be written as correct or incorrect about the nature and desires of their Creator. At that point to say that the characters live in a "meaningless" world is to deny the artist/author the capacity to have thoughts worth attempting to interpret and understand.

What characters can grapple with is the dawning existential horror that their own Creator is at the whims of living in an unpredictable and meaningless universe. Hyetta perceives the nature of the One Great as being fractured and suffering. Re-framed as an overly dramatic allegory and perhaps The Creator - the "One Great" - was once a single person with a vision for the work of art they wished to make, but then came fractures in the form of employees hired to do specialized tasks and bringing their own ideas and input and increasingly complicated logistical challenges which culminates in burnout. Mohg believes that the Formless Mother craves wounds. Consider this in the context of modern action RPG's and it's not necessarily that the Creator is enthusiastic about dousing everything in gore - but the players that they cater to expect an action game to get bloody so it's either concede to the whims of expectations or perish.

That knight was supposed to go on a soulful quest to restore the honor of his Lord? No he isn't - that quest has been cut for budget and time reasons because it came down to a choice between that or the story of a little Demi-human runt who tries so hard to look and act the correct aesthetic of a Lord's man that he strips away all of the uniqueness that made him an individual. Any character at any time could be discarded when their Creator is under pressure to choose between reinforcing an old familiar pattern or experimenting with something new. A story about an honourable knight loses favor when one re-examines biases and is brutally honest about the way that story perpetuates the myth about the greatness of men as more important than other forms of life.

Or consider Knight Diallos whose quest begins with haughty ideas of honour and ends in disillusionment and self-imposed exile

Elden Ring in particular seems to have the ambitious scope of creating a story that examines the ways in which the complexity of human miscommunication throughout the history of the real world is due to the phenomena where EVERYONE creates their own meaning and projects, but also in which many people are in denial about this agency. And misery is generated by the trauma of upholding absurd systems of power.

Absurdism and Anti-art

One of the reasons why I typically reference "The Theatre of the Absurd" rather than "Absurdism" is because "absurd" is a word where the connotation is different depending on whether it is applied to the real world compared to a work of art.

As I understand Absurdism, to observe that existence is absurd is to say that the universe is irrational and meaningless and human life has no ultimate meaning, AND YET people persist in believing in the illusion of control and meaning. The classic responses to exposing the absurd contradiction being:

1) Rejecting the illusion of control and rejecting any semblance of meaning - self-destruction through despair, 2) Embracing the illusion that everything is controlled by a higher power. This one can be weird because of a sliding scale of belief in meaning and lack of meaning - for example "everything is according to Gods plan" so the actions of individuals are meaningless, but also "you go to Hell if you step out of line" so your actions DO matter but everyone has a different personal interpretation about Hell and also the line keeps moving, 3) Rejection of the absurd. Which is to say, rejecting the illusion of control and pre-determined meaning - but deliberately inventing a meaning that satisfies the individual.

This rejection is where the confusion seems to happen when discussing in terms of pure metaphysics - embracing the irrational and meaningless universe easily spins into Nihilism, which is the belief that knowledge is impossible. Different schools of Nihilism seem to have different definitions of how far this belief extends. In my opinion, Nihilism can't handle complexity and pretends that any problem can be reduced down to the binary "knowing nothing" about a particular topic or "being certain of everything", and since certainty is impossible the first must be true - thus nothing means anything. In the reality of real physics, we manage to manufacture and construct things all the time while not being 100% certain that the expected performance will be identical to the actual performance. In engineering if a thing can be known with 95% confidence that's still pretty good! It's why we apply massive safety factors.

To say that a work of art is in "The Theatre of the Absurd" is to say that it is a work of art constructed to demonstrate the themes of existentialist/absurdist philosophy - to show-not-tell via its content the human response to a universe that is irrational and meaningless and in which human life has no ultimate supernatural meaning.

Depending on the work, it may focus on one or all of the the classic responses to the absurd, or expand on the idea by adding variants. On the one hand this is easy - because we live in an absurd universe that does not care about the beliefs and wants of individuals. On the other hand this is hard - because the work of art itself is a microcosm made by an intelligent creator with the purpose of conveying specific themes, or structured in such a way that invites the audience to doubt the truth of their own deeply held beliefs and biases. The artificial work does this through words and literary conventions, whereas the real world is more likely to challenge beliefs through such basic things as "no prayer has ever stopped a tornado" or "death by incurable and inoperable cancer".

But I have observed that often when people describe a work of art as "absurd" this is a claim that the work itself is irrational and meaningless and offers no insight into the intention of its author.

Expressing a belief that the author had no goal to demonstrate - they made a piece of visual or auditory noise and thus there is no meaning to think about and discover. A random selection of shapes and colours and objects cobbled together in a way that the individuality of the artist is obscured by too much being left to random chance or abstraction. The tendency may be that the larger the number of people involved in the components of a work, the more the individual is ground down and buried under the collective - because this comes closer to mimicking the random noise of reality. Or it may be a type of thought experiment - how lazy and/or crude can the artist get while still making something considered to be "art" in the sense that it provokes any emotional reaction at all, positive or negative. The implementation of machine learning in generation of text and images is probably the closest humanity has gotten to producing something lacking meaning, and even still there is an element of selection involved by which people can be appraised and/or mocked by the quality (or lack of quality) in the outputs produced.

Anti-art is the pre-cursor to Dadaism, which are generally in the idea that anything can be art, and therefore nothing is "art". The specific goal can be to undermine or understate individual creativity as being subsumed by the collective will. The goal can be to demonstrate the extremes to which art must be more than just pleasing aesthetic - it is about exploring and communicating thought.

In this second case, the artist presents an irrational problem and invites the onlooker to participate and consider the meaning. You'll need to discard all illusions and expectations that everyone who participates will grasp the intention of the work. You could attempt to correct them by issuing a clearer or rephrased statement of intent - but no plain language exists that could simply describe the piece and lecturing or setting in stone a "canon" answer is not the point. The thinking was the point. The hope that a viewer can understand even part of the work and it changes them for the better. No human being can 100% know another irrational human being. And yet enough data points can give a good enough shape to anchor to and build from.

Beneath the Chapel of Anticipation & a view from a rada fruit

As an example, the Dada Manifesto was itself declared in an act of performance art:

"The Dada Manifesto (French: Le Manifeste DaDa) is a short text written by Hugo Ball detailing the ideals underlying the Dadaist movement. It was presented at Zur Waag guildhall in Zürich at the first public Dada gathering on July 14, 1916. The choice of this date, Bastille Day, was important to Ball as it carried significance as a protest to World War I. In this manifesto, Ball begins by giving diverse definitions of the word "Dada" in multiple languages. He continues to introduce the movement's own definition of "Dada" by boldly asserting that "Dada is the heart of words." Ball concludes his manifesto with a linguistic explosion that alternates between coherence and absurdity."

I suppose if a person can admit that the small acts of creation have no meaning except for the ones that humans assign to them, then maybe they will be able to admit that neither do the institutions created by humans - militaries, nations, religions, etc. The goal of the artist is to present a contradiction that makes the viewer think about expectations. In a way it's a kind of dialogue where the artist has secret knowledge for why they did what they did, and may be just as interested (or more interested) in seeing the reactions of other people interpreting their provocative art as they were in the act of creating the piece. Something of a challenge - if you puzzle over the mysteries then you might even arrive at a conclusion that matches that of the artist, but they have no obligation to confirm or deny and you just need to live with that. Understanding is not achieved through memorization of "facts" or the "correct answer" but by arriving at a plausible explanation for each link in the chain of cause and effect that ended in the observed outcome. Whether each of those links occurred by intention or by random chance.

According to influential Anti-art and Dada artist Marcel Duchamp - as said in 1958 when by all public appearances he had abandoned art for chess (more on that later):

"The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act."

Note "deciphering" alongside "interpreting", which gives the context that this intention of art is a translation of thoughts from one mind to another, which may then proceed to build upon the ideas. This is distinct from the Nihilistic concept that knowledge is impossible, which subsequently concludes that all art means no more or less than whatever the viewer wants it to mean. And this kind of deciphering is sortof what is meant by the anti-art position that nothing is "art" - in that "art" is just one of many mediums in which thoughts and ideas are communicated from person to person. Every person has a capacity to communicate and create, and it is a matter of unaddressed biases that the works of a select few people have historically been considered more worthy of knowing than others.

However it is true that one of the ways that artist may obfuscate the original idea that prompted their work is through the technique of collecting assemblages of found objects presented as art. In this case, the deliberate choices of the artist are competing with the choices made by the people who manufactured the original objects - and the viewer can't know all of the factors influencing the artist's selection. Interpretation cannot rely on the classically trained conventions of using rote memorized facts about desired form, colour, symbolism, composition, etc to understand the meaning of the work - they are challenged to consider the meaning of the functional objects that they take for granted. New semiotics are constantly evolving. And when people are confronted with a situation in which trained memorization about aesthetic principles cannot help them, it is revealing what they may instead bring to the art in the form of their personal and individual biases.

In Seethewater Cave the Commoner bodies are posed as if reaching for the pink flowers. Because of context we know that a pink flower is a Poisonbloom and through investigation we know that one holds the Mushroom Armor Set (sans crown) and the other holds Immunizing Cured Meat. Common elements re-contextualized through understanding the meaning assigned in the text of the game.

In the Church of the Eclipse a water bearing statue appears to pour out the soul containing the Eclipse Shotel

Marcel Duchamp

So in my research I got distracted by the body of work of French-American artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), going well beyond the one work that he is most infamous for (not relevant for this post but you'd probably know it when you see it). I did not look at literally everything, but picked out some examples for demonstration.

Left: Sonata by Marcel Duchamp

Right: Bicycle Wheel (3rd Version) by Marcel Duchamp

The first cubist work produced by Duchamp is titled "Sonata" (1911). It depicts two young women looking right and playing a sonata for violin accompanied by piano, under the gaze of an older woman in blue. A third young woman sits in the foreground looking left and wearing yellow skirts. These uses of colour are somewhat atypical from monochrome cubism and could hint at use of a developing colour language similar to those of expressionists Kandinski and Franz Marc. An outside observer can look at this painting and feel free to fill in the vague sounds of piano and violin music, a closer observer might note the incongruity that only two people play in a Sonata for violin and that the girl in the front has no instrument but does have a colour association with a small sliver of yellow room in the upper left corner. It could mean something, or could mean nothing. Duchamp didn't develop this particular style for long enough to establish a pattern.

Documentation on the painting indicates that these are Marcel Duchamp's three sisters and mother, and that the sister in the foreground is Suzanne Duchamp, who was also the subject of some of his earlier sketches and who followed him and their older two brothers into the visual arts and the Dada movement in particular. Historical anecdotes also indicate that their mother was distant from her children and hard of hearing.

When Marcel Duchamp attaches a bicycle wheel to a stool, titled "Bicycle Wheel" (1913) and this synthesis of two found objects is the entire work then the artist has distanced himself from being Known through the work. Did Duchamp use the first stool and the first bicycle he encountered or was the selection more deliberate? If he did make a deliberate selection, was the colour of the stool a consideration? The type of wood? The sentimentality of the object? He says of the work (of which multiple were made) "I had the happy idea to fasten a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and watch it turn." Is the purpose interactivity - can I spin the wheel - or is the purpose denial of interactivity by a higher power - the museum staff would tell me that touching the object is forbidden? Is the selection of a stool significant (rendering useless an object designed for rest), or was it simply a convenient platform? Maybe I can identify the exact make and model of the bicycle - do I assume that Duchamp also selected for this context? The number of unknowns vastly outweigh the number of knowns. The questions that I think to ask and the things that I take for granted say something about the way that I think. I have noticed that some people are embarrassed to be seen as overthinking or afraid to be caught in a wrong assumption.

My interest in doing research to decrease the number of unknowns depends entirely upon my interest in committing to understanding the thought process of Marcel Duchamp the person and not just Marcel Duchamp the quirky Dadaist. A person may think that the selection of any given "readymade" object (as he called them) was absolutely random, but even a random data point can be plotted on an axis and compared against other random data points to reveal trends over time. Before Dadaism Marcel Duchamp was a cubist who painted abstractions of the human form in motion. In the 1920's one of his pseudonyms was a woman named "Rrose Sélavy" a play on words for the French phrase "Eros, c'est la vie" - and there are multiple photographic portraits of Rrose Sélavy. During this span of years and into the 1930's he was interested in designing kinetic sculptures, some of the last being a set of "Rotoreliefs" in 1935. These are a set of spinning disks meant to be set on a record player but which play no sound. Instead they are cardboard painted with an optical illusion that appears to form a 3D image when the disk is spun at a certain speed. Later in life he associated with some surrealists of the time but otherwise largely abandoned art for chess and in 1943 composed a chess endgame problem with the instruction "White to Play and Win" superimposed with a cupid - a problem which chessmasters and chess bots have concluded as an impossible task. If both sides play perfectly it ends in a draw.

Initial positions on left, one possible draw position on right. I wonder if the instruction included in the piece was a jab at U.S. chess champion Weaver Adams who in 1939 wrote a book called "White to Play and Win" about how white should always win due to its first move advantage. The article doesn't mention this. The presence of the cupid should also not be ignored - the game is only a draw if both sides use perfect logic and does not account for irrational decisions on either side.

Originally I had a long section here about the last work of art created by Duchamp, which was secretly created between 1946-1966 and only revealed after his death. Decided that it was extensive enough to warrant a separate post.

Essentially: the goal of Anti-art in the early 1900's is the same or similar as the plays grouped under the Theatre of the Absurd. It is not to create something so random that it becomes a microcosm for the irrational and meaningless universe - impossible to understand. On a basic level they both demonstrate the same thing: failure of communication. Two characters playing against each other who each hold irrational beliefs so alien to each other that they cannot find common ground. An artist who knows that no matter how clever an idea seems in their head, they cannot control against being misinterpreted by somebody with different background context - so why should they ever explain bluntly and ruin the mystery? A picture is supposedly worth 1000 words and a poem more memorable of a mnemonic than a 100 page manifesto, so let the art speak for itself as a representation of thought.

Work from an artist who appears like a flash and then disappears forever meets a criteria of randomness. But an artist who makes successive individual works in an obtuse and enigmatic style may eventually have their thoughts deciphered, processed, and built upon by people considering in retrospect the sum total of their works and words. Not 100% known, but like maybe 90% of the philosophy that they lived by, beyond the "-ism"s of collective movements.

Links to pieces that other people have written about Duchamp:

Other examples of Marcel Duchamp's art

Rrose Sélavy is Marcel Duchamp

But for a more direct Elden Ring reference, this is what I propose: Seluvis is Rrose Sélavy. At least, as a partial inspiration. "Seluvis" can be deconstructed into the French sentence fragment "se lu vis", vaguely meaning "read one's own face". "lu" = 3rd person past conjugation of "lire" meaning "to read", "vis" = archaic or slang of "visage" meaning "face", and "se" is a reflexive pronoun used when a person does an action to their own body (simple example: "Je me suis brossé les dents" meaning "I brush my teeth").

And Compare:

A) Duchamp's Rotoreliefs (see in motion on this page);

B) Seluvis' hat, where the dark colouring and many nested lines gives it an appearance similar to the grooves on an LP record;

C) The album art for a 1995 release of Leo Ornstein's Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 31, SO 614, composed in 1915. "Ornstein" being a named character in Armored Core IV (2006), and a character with a lion motif in Dark Souls (2011). And Leo Orntein's sonata for violin and piano being an avant-garde piece that is contemporary to Marcel Duchamp's similarly semi-abstract painting Sonata (1911).

Elden Ring Part 1 - Thinking about Thinking

So my goal here is to demonstrate how understanding Elden Ring as a work of fiction within the style of "Theatre of the Absurd" helps engage with the big questions: "What is the Greater Will?", "Why did Marika Shatter the Elden Ring".

At the most basic and literal level Marika shattered the Elden Ring because it was a thing that she did not think should exist.

To understand why the ring should not exist requires understanding what the ring represents. Understanding what the ring represents requires understanding all of the demigods. Understanding each of the demigods requires understanding each of their domains. Understanding each domain requires understanding each NPC and enemy that is positioned throughout the regions of the map. Understanding your enemy requires understanding of yourself (i.e. understanding "yourself" can mean understand the roles expected to be played by the starting classes based on the identity they begin with).

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.” - Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Compartmentalize until the questions are small enough to handle and build the foundation before jumping straight into big picture questions. Marika is the Lands Between and the entire game consists of the puzzle pieces of her thoughts and memory.

We have the advantage of being impartial observers existing outside the frame of reference of the NPC's. The characters in an existentialist play are not genre savvy to knowing that their woes are caused by a breakdown of communication that leaves them incapable of resolving their differences without violence. We can watch the NPC's run through their tragic fates as many times and from as many different literal OR symbolic angles as it takes to pin down the themes that they were given by their writers, and the themes formed from grouping sets of characters, and so on.

Based on what I've found by looking at the environment very carefully, I would generally describe it as intentionally mimicking the complexities of a physical world made of atoms and subatomic particles that took thousands of years and people to even acknowledge as existing much less identify the patterns of properties found in the chemical elements. And also thousands of years worth of linguistic baggage and complex cross-cultural etymology of words that develops when people constantly re-examine their assumptions about the way the world works, and then imperfectly share them with other groups of people who do not have words for the concepts in their own language. Altogether it creates a complex snarl of a puzzle, but I have good news: the most elegant and consistent patterns are in the sciences. Material sciences, biology, electromagnets, thermodynamics, optics, sound, etc. Pick any chemical element, and hyperfixate on its history of discovery and usage, etymology of its name, physical properties, etc and hunt for the matching concepts and visuals in Elden Ring. Repeat with the other elements.

It's a large task. The work of years to completely untangle in between living life and doing other things. But I will say that there is another way to arrive more quickly at an incomplete answer about what the Greater Will was at a particular instance of time, and what the Shattering meant at that particular time. Start at the very beginning (a very good place to start): understand the origin of FromSoftware as a company making fantasy and sci-fi video games. Treat the problem as Absurdist art and make an educated guess about what thoughts and principles govern the collective of people operating under the name of "FromSoftware".

The 16 circles with the flower motif may act as a representation of overlapping spheres of knowledge. Each single circle is geometrically divided by 6 arcs, forming an intricate venn diagram.

Elden Ring Part 2 - The Greater Will

I had a specific reason for selecting Duchamp's "Bicycle Wheel" of all of this readymades because it reminds me of another wheel: The Wheel of Time. There are hints that ever since King's Field FromSoft games have been inspired by the Wheel of Time fantasy book series. Not that they copy, but that somebody on their staff pulled apart Wheel of Time to learn the mythologies and psychology that form the logic basis for the world building, and then reassembled parts in a new shape with their own additions and complexity accumulating over time.

The relevant example here: Patch the Good Luck in Armored Core For Answer (2008) has hints of taking cues from Wheel of Time's Matrim Cauthon, in the form of his emblem being a die modifiedto always roll 6. Since book 3 Mat is said to have the "Dark One's Own Luck" because of the way that when he plays dice he always wins as much as he needs to in order to be where the plot needs him - his luck is supernaturally rigged. Mat begins the series as a mischievous boy who partway through book 1 becomes a Gollum-like paranoid mess after an incident with a cursed dagger, and he heals from the experience with a memory full of holes. In book 4 he has his head filled with the knowledge of lives of great generals of the past while being hung from the Tree of Life by a spear engraved with the phrase "Thought is the Arrow of Time; Memory Never Fades", and by book 13 has himself become a great general, acquired the title "Prince of Ravens", and loses an eye - and yeah he's an Odin reference.

Patch emblem on left, Wheel of Time chapter header on right

But the great enemy of the series - "The Dark One" - is also an Odin reference, just as both Gandalf the Grey and Sauron are references to different aspects of Odin in Tolkein's the Lord of the Rings. Mat's morality slides throughout the series (his end state is becoming allied with a nation of Slavers) even as the eldritch and incomprehensible Dark One is defeated in the end, setting up the concept that when there are no more supernatural battles to fight humanity is forced to face its own dark thoughts without the excuse of a scapegoat.

So here are a few ways how it is conveyed that Patches has a similar affinity with the Greater Will:

The Odin connection. Looking at FromSoft's body of work it can be inferred that from the very start the reason why the mercenaries of early Armored Core are called "ravens" is because it's an Odin reference - ravens are the agents of Odin that carry his "thought" and "memory". Twice characters with the name "Patch" are featured in Armored Core - Master of Arena (1999) and the previously mentioned Armored Core For Answer. The weapon that Odin is most associated with is a spear. Patches wields a spear in Demon's Souls, a spear in Dark Souls 1 and Dark Souls 3, a spear in Elden Ring. Pate in Dark Souls 2 wields a spear. The first instance of an archetypical "Patches" character is an unnamed character wearing army fatigues who is one of two humans in Shadow Tower Abyss (2003) - a game where the goal is to find a magical spear and then the spear shatters to pieces as soon as you find it. The "Patches" of Sekiro is called Anayama the Peddler (where "Anayama" can be translated to "Patch"), and in this version he is missing an eye like the classic depiction of Odin.

The "Greater Will" connection in Bloodborne where the oldest research institution is Byrgenwerth and the head of the institution is Provost Willem. So there's a "Will" who is "Greater" than his students in terms of the respect commanded. There are notes found in the game "The Byrgenwerth spider hides all manner of rituals, and keeps our lost master from us." and "The spider hides all manner of rituals, certain to reveal nothing, for true enlightenment need not be shared." which is generally assumed to be Rom, the Vacuous Spider. The spider hides all manner of rituals. In a game where Patches takes the form of a spider with the head of a man. And the design of the Vacuous Rom is such that 1) ROM's form has no resemblance to the little spiders aside from the leg shape, 2) the legs of Rom are comically small for it's top heavy form, and far too many for a "spider", 3) vacuous has connotations of an empty husk. It overall gives the impression that Rom is a corpse puppet for the spiders. If you're looking for a true enlightened being, would that not be Patches-the-multi-versal?

Voice actor connections. Voice actor for Patches in Demon's Souls, Dark Souls, Bloodborne, and Elden Ring is "William Vanderpuye" - another "Will" behind the scenes. Patrick Seitz voices Patch the Good Luck in AC4A and Handler Walter in ACVI: Fires of Rubicon. Handler Walter's emblem is in the form of a hand "pulling the strings" like a puppet master, and this is also the form of his relationship with the player, until they rise against him. The Greater Will in Elden Ring is also conceptualized as a puppet master, particularly in the way that the nervous system of the Elden Beast is composed of Amber Starlight and it is known through Seluvis' quest that amber starlight can control the fate of even gods - indicating that the Vassal Beast is still acting in accordance with the Will of something Greater to the bitter end.

And then there is also main character Michael Wilson ("son of Will") in Metal Wolf Chaos (2004) - with an easter egg in game where you can encounter a statue of your father who was a previous President of the United States of America and it reprimands you. If you destroy the statue you get a flamethrower weapon as a reward.

So what is the Greater Will? It's the Dark One, mythological Odin, a puppet master, a mentor, a father, an animating force behind the scenes, the game developer "FromSoftware", the collective Will of the players who pay money to keep game development a viable career. The answer depends on perspective, but the common theme is that the Greater Will is something to be learned from and then surpassed as a person finds their own Willpower to stand on their own.

In all of his appearances Patches tends to kick the player into a pit to mock them, but there's usually something of value to be found or learned in the experience if you pay attention. In Dark Souls 3, Patches hates clerics, specifically. In Elden Ring if you follow through Patches' questline to the end he feigns death and gives you a item that is useless for anything other than Tanith getting snappy at you. It's a castanet cast with a Ring motif in its design - so basically Patches sends you on a quest to deliver a ring to a volcano in a way that echoes Gandalf sending Frodo to Mt. Doom to destroy the One Ring.

Which is a segue to the next section:

Elden Ring Part 3 - The Shattering

Why did Marika Shatter the Elden Ring? Again, I start with the Wheel of Time for guidance. My interpretation is that the Shattering in Elden Ring is serving a similar purpose as the Breaking of the World in the Wheel of Time. Allegory for a kind of mental break - the sudden clarity that things can't go on the way they have been going. For example: it's quite bad, actually, that power in the real world is concentrated in the hands of people who hold insane and harmful metaphysical beliefs that prioritize fantasy over observable reality.

In the case of Wheel of Time, I suspect that this was a kind of personal allegory. Author James Rigney, pen name "Robert Jordan", served in the Vietnam War and experienced first hand how the lives of people are shredded in service to global superpowers. This was not a war of self-defense or defense of an ally as World War II had been, but a pre-emptive strike - a military action consistent with a God of War like All-Father Odin. The Seanchan - the nation of slave-keepers in the Wheel of Time whose prince consort is called "The Prince of Ravens" again in reference to Odin - are the descendants of a multi-cultural melting pot of people who traveled west across the ocean in a parallel to the colonization of the Americas, and now return 1000 years later to conquer the homeland they left behind. Even after the supernatural threat is defeated, this human army is still very much a threat, and left as a loose end at the conclusion of the series.

In general, an area where Wheel of Time falls short is that it does not strive to tell its story outside the context of myth and symbolism congregated in the mind of one man. Even if he has drawn from a wide range of sources - a background with Freemasonry being intersected by the philosophy of Taoism, Norse/Finnic Mythology, and more. But if there's evidence in his work of research into modern understanding of the sciences past the invention of gunpowder, then it is not something I've noticed. The setting acknowledges the problem that there is always another war on the horizon, but cannot propose a solution.

FromSoft's Shattering goes in a different direction - allegorical for breaking out of a reliance on myths made by prior generations. The origin of myths are as alluring stories that simplify and explain phenomena of the real world in terms that satisfy curiosity. The epiphany arrived at is that many artists are themselves complicit in the careless propagation of myths that reinforce thought patterns and biases about who deserves to have power and who deserves to be burned in a witchhunt.

The people want the classic story of the Greek god Apollo delivered to them in it's 500th variation, because maybe this time the artist will get closer to their mental image of what makes a "perfect" Apollo as refined over those 500 variations. And so the artists are the ones that get tired of waiting for that 501st variation and do it themselves. They carve away the bits they don't like (the assault of women, for example) and graft on things that they do like (a brought-down-to-human Apollo angsty about prophesying doom but never being able to avert it) - but still the artist finds it important to communicate to the viewer either explicitly or in context of other re-imagined Greek gods that this IS "Apollo". Which invites comparison with the original story. It invites people to ignore the new features that they are actually being presented in favour of going down a rabbit hole of investigation into the bottomless pit of things that we know or think that we know past civilizations to have believed. This is the struggle of post-modernism - people have access to the accumulated thoughts and symbolism developed by humans throughout history, which includes a lot of glittery trash.

I have seen people saying that Elden Ring offers no solutions. I have observed that this is false - more accurate is that you get out of the game what you put into it. A belief that all options are equal is what a person gets from believing too heavily in the expected tropes of literary myths - believing that the key to understanding is to study the myths of Ragnarok, Armageddon, the Wheel of Samsara, the sacred geometry, etc. Dig below the surface and FromSoft's solution to the tired repetitions of old mythology is to create new myths based on real human achievement, discoveries, and tragedies from more recent events. You can understand the Elden Beast (and the attempt by Miquella to repeat the cycle of history) through the lens of parasitology. You can understand the Age of Stars through the development of artificial cold. You can shift perspective to seeing the story of Elden Ring not as an empty Hero's Journey but as an investigation to understand the reason "why did Marika Shatter the Elden Ring?".

"Learning true facts about reality" and "sharing information" are the solutions to breaking free from the thought-terminating mind-states of paranoia and willfully ignorance.

Wrapping Back around to Art Talk

Sometimes I draw and paint things. I have probably thousands of pictures of varying quality at this point - some physical but most digitally archived and sorted in folders. I can look through most of them and recall what their purpose was - this one was for course work and had a design brief attached, this one is surreal stream of consciousness stuff, these botanicals were made because I like learning new flowers, or that one is somebody else's character entirely.

There have also been some times when I do make something where I can think "yes these capture a distinct thought or moment in time in an image". They are no masterpieces, but these are an example of that kind of artwork in my own particular style:

Virtual Reality (2007)

Weak (2018)

Howe Truss (2009/2021)

#elden ring#fromsoftware meta narrative#Marcel Duchamp#Wheel of Time#Theatre of the Absurd#literary analysis#art critique#no easy answers for big picture stuff#and if nobody else is going to write the analysis I'd want to read then I guess I write it myself

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, people explaining that AI isn't "real art" bother me, not so much because of the answer they reach but because most of the people saying it isn't seem to romanticize not just commercial art production, but also bizarrely to romanticize AI as well, in ways that bother me for subtle reasons I want to try to articulate.

So, first of all, I personally don't think fine art will be changed much by AI.

"What if the artist isn't directly producing the art but instead letting some process create it?"

Convergence by Jackson Pollock, 1952

"What if the so called "artist" is merely rearranging and recontextualizing something that already exists?"

"What if the artist outsources a tremendous amount of work?"

Cambell's Soup Can, Andy Warhol, 1968

The fine art world already confronted these questions and answered between 1912 and, what, 1980 at the latest maybe?

My point here is not to assert the artistic worth of these paintings but to assert their undeniable importance to 20th century art history.

Nobody paying thousands of dollars for a traditional painting on canvas is going to buy an AI version because it's cheaper; such people are already paying a premium for artistic technique and cultivated human talent.

Or, alternatively, I have absolutely no doubt that people would pay a lot for an AI project with, I don't know, Banksy's name on it, even if it was made with freely available, open source tools, because in other cases people are paying for, essentially, a name.

The fine art community already confronted the questions raised by AI art and we're already on the other side of that confrontation. Statistically, the large battles being waged over these issues already finished before you were born.

The actually (potentially) endangered part of the art world is the commercial art world.

Not fine art, but art produced as part of an essentially commercial process in large part under the direction of other people. Fan Art, scripts for films, stock footage, key art used for commercial campaigns, pulp fiction cover illustrations, etc.

And, first of all, the reason that you can be so romantically attached to low-brow, heavily commercial art in the way that you are without feeling utterly absurd about it is Marcel Duchamp's Fountain and the works of Andy Warhol, so maybe have a bit more respect for them and their place in history if you are going to romanticize commercial art production.

Second, because it is those things that are threatened, defenses of human art against AI tend to have this kind of implicit view that the things which characterize commercial pop art are the most important characteristics of art. There is something about this that kind of bothers me for reasons I have trouble bringing up.

Okay, like, one I just watched a YouTube video where the creator said, more or less, "Can you imagine a world where people are so alienated from the production of art that instead of learning to produce it themselves, they type 'woman painting a picture' into a box on a computer and something just pops out?"

The video background was stock footage of a woman painting.

You have this really obnoxious trend of people who make monetized YouTube videos out of other people's copyrighted clips (Claiming "Fair use") talking about how awful it is for AI to "steal" other people's works, and people who fill their videos with stock footage and library tracks talking about how crazy it is that anybody would want to outsource this stuff instead of learning to do it themselves.

But also, beneath that, there is a kind of picture of "What's important about art" that is being built purely out of commercial concerns but masquerading as belief in something higher, and that really bugs me. Stock footage is elevated to the highest of human endeavors purely because it is commercially threatened by AI production.

221 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes: Found Poetry

Found poem - a form of poetry that comprises borrowed text from different sources.

Poets borrow words, phrases, or passages from sources like novels and news articles for found poems.

Assembling the sourced texts brings a new meaning unique from the words or phrases’ original context.

Types of Found Poetry

Blackout poetry: Blackout poetry is a form of found poetry in which the poet takes an existing work—an article, a short story, or even another poem—and uses a pen or marker to black out certain lines, words, or phrases to reinterpret the original work.

Erasure poetry: Similarly, erasure poetry involves using whiteout to cover certain words. In both forms, poets create new text to celebrate or subvert the intention of the original work in some way. Graffiti that covers up words on buildings or signs may be a kind of erasure poem.

Cut-up poetry: Cut-up poetry involves cutting words out of source materials and rearranging them to create new meaning.

Ways to Write a Found Poem

You can create found poetry using books, magazines, or digital sources:

Craft a haiku. For those new to this type of poetry, creating a haiku works as an introductory writing prompt. A haiku, a Japanese poem, has three lines: the first has five syllables, the second has seven, and the third has five. To create your poems, try the cut-up method: Find words or phrases that total the syllables in each line and arrange them in a way that elicits new meaning from the found text.

Gather physical text sources. Cut out hardcopy sources like a book or magazine, then paste the words together to create found poetry.

Find digital sources. You can create a found poem from existing texts online. Write out a new poem by hand, or copy and paste words on your computer into a document.

Write in free form. Because the individual source materials will likely have their own rhythms and vocabularies, found poetry is usually written in free form; spacing and line breaks are at the poet’s discretion.

Create a blackout poem. To try a blackout poem, read an article and decide how you’d want to reimagine its text. Then, using a marker, black out specific headings, phrases, and paragraphs, leaving behind words so as to create a new work from the source text.

Examples of Found Poetry

A found poem involves a poet taking pre-existing language and reworking it into a new artwork. Consider the following examples of found poetry:

Book compilations: American poet Bern Porter published multiple volumes of found poetry, including Found Poems (1972).

Sarcastic poems: The humorists Hart Seely and Tom Peyer wrote “The Man in the Moon” (1979), reworking lines spoken by New York Yankees announcer Phil Rizzuto to reflect on the death of Yankees catcher Thurmon Munson.

Literary magazine: The poetic form even sparked its own literary magazine, The Found Poetry Review, in print from 2011 to 2016.

Blackout poetry: he New York Times bestselling author Austin Kleon has popularized the blackout form in his book Newspaper Blackout (2010), in which he redacts newspaper articles in permanent marker.

A Brief History of Found Poetry

Poets have created found poetry in various ways across artistic movements and history:

The cento: The cento, which originated in the third century, may have been the original found poem. A cento poem is a work of poetry that is composed of various lines taken from different poems. The word “cento” is derived from a Latin word meaning “patchwork garment”—and a cento poem is just that—patchwork poetry (also known as a “collage poem”). With cento poems, a writer can pay homage to another poet, or use lines from another work for satire purposes.

Dadaism: In the 1900s, visual and literary artists brought new meaning to source materials and pre-existing texts. The popularity of found poetry mirrored the Dada movement. Dadaist Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 work Fountain was a readymade sculpture that was simply a porcelain urinal. Outside of its original context, the work invited a new perspective and interpretation. During this time and in a similar artistic vein, poets like William Burroughs began experimenting with cut-up poetry, rearranging words in new order.

Modernists: In the twentieth century, poets like T.S. Eliot, Brian Gysin, and Ezra Pound included found text from various source materials in some of their works.

Media: Today, poets can create found poetry using digital sources and share works on social media platforms. For example, best-selling author Kate Baer creates found poetry by redacting comments on her social media pages.

Source ⚜ More: Notes & References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs ⚜ Part 1

#writeblr#poetry#found poetry#dark academia#spilled ink#writing reference#literature#blackout poetry#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#erasure poetry#poets on tumblr#creative writing#writing inspiration#writing ideas#light academia#blackout poem#lit#writing tips#writing advice#writing resources

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'avventura del design : Gavina

Davide Vercelloni, prefazione di Vittorio Sgarbi

Jaca Book, Milano 1987, Saggi di Architettura/Design, 256 pagine, 185 illustrazioni b/n, 15x23cm, ISBN 88-16-40 309-8

euro 100,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

L’avventura straordinaria di Dino Gavina (1922 – 2007) ha inizio con l’apertura di un laboratorio di tappezzeria in Via Castiglione a Bologna. Qui nel dopoguerra si ritrova ad utilizzare materiali di recupero per forniture militari e ferroviarie e inizia a produrre e commercializzare i primi mobili.

Interessato ed appassionato di letteratura, arti visive e teatro; diremmo oggi, “viaggia ed incontra gente”, ma coglie in ciò il genio e l’opportunità di creare cose e personaggi: è questa la miscela creativa di Dino Gavina. Instancabile regista di persone, cose, fatti scaturiti dal suo immaginario, un vortice in continuo movimento che corona tutta la sua vita. Incontri con personaggi, che crea talvolta egli stesso. Con Lucio Fontana stringe una bellissima amicizia. Frequenta Milano e alla X Triennale conosce i fratelli Castiglioni; alla XI nel 1957 l’incontro con Kazuhide Takahama, che ha realizzato il Padiglione del Giappone; a Venezia incrocia Carlo Scarpa, che nel 1960 diventerà presidente della Gavina spa, dove verranno prodotti i primi pezzi di suo figlio Tobia… Una vita costellata da personaggi straordinari.

Il negozio Gavina realizzato da Carlo Scarpa in Via Altabella a Bologna, lo straordinario padiglione espositivo di San Lazzaro di Savena dei Castiglioni, moderne architetture che possiamo ancora ammirare, dove si svolsero le memorabili serate di Man Ray e Marcel Duchamp. Proprio a San Lazzaro nasce nel 1967 il Centro Duchamp, in suo omaggio, dove lavoreranno futuri artisti cinetici al fianco di grandi maestri, un progetto di arte fatta in serie per nuovi fruitori.

Lunghissima è la lista di artisti con cui ha collaborato, occupandosi di una miriade di mondi, questo è infatti il lato sfaccettato e poliedrico di Dino Gavina. Note le sue aziende Gavina, Flos, Simon, Sirrah, Paradisoterrestre: la passione di realizzare mobili, lampade, arredo per interno ed esterno, nella linea rigorosa del disegno industriale, che in parte deve a lui l’apertura di nuovi orizzonti.

11/12/24

#DinoGavina#avventuradeldesign#CarloScarpa#KazuhideTakahama#fratelliCastiglioni#ManRay#MarcelDuchamp#mobili#lampade#arredoperinternoesterno#Gavina#Flos#Sirrah#Paradisoterrestre#disegnoindustriale#designbooks#designbooksmilano#fashionbooksmilano

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

" ... I asked Duchamp whether he had anything to say about the extensive linking of art with technology, and the attempts to make him a progenitor of the tendency. ‘They have to get somebody as a progenitor so as not to look as though they invent it all by themselves. Makes a better package. But technology: art will be sunk or drowned by technology. Look, I’ll show you an example.’ Duchamp then plugged in a framed box in which electric heat acts on the liquid and crystals within, making them surge up in a sea-green orgy of movement. ‘This is a work by Paul Matisse, Matisse’s grandson, who does not regard himself as an artist. In fact, he intends to manufacture this, and you’ll probably see it in every motel in the country. It could be seen as an artistic conception I suppose.’ ‘Technology will surely drown us. The individual is disappearing rapidly. We’ll eventually be nothing but numbered ants. The group thing grows. You can already feel the tendency in the arts today. Speed, money, interest. A hundred years ago there were few artists, few dealers and few collectors. Art was a world by itself. Now it is completely exoteric—not my cup of tea. There is something wonderful about the secret society that is lost. ‘To get back to what you asked me about the ready-mades. You can’t choose with your taste. Taste is the great enemy. The difficulty I had was to choose. Now my Bottle Dryer is in the books and some regard it as a beautiful sculpture, but not all ready-mades were the same. Once, many years ago, I was dining with some artists at the old Hotel des Artistes here in New York and there was a huge old-fashioned painting behind us—a battle scene, I think. So I jumped up and signed it. You see, that was a ready-made which had everything except taste. And no system. I didn’t want to be called an artist, you know. I wanted to use my possibility to be an individual, and I suppose I have, no?’ We then spoke a little while about Duchamp’s renown, and he pointed out that he had never been particularly cherished by the French. ‘You can’t be a prophet in your own country. I certainly am not.’ Are you better appreciated here, and why did you settle here? ‘The melting pot idea, you know. And the lack of difference between classes. It interested me then. The French Revolution was more evident here in those days. It was good for an artist. Of course, it’s a little messy now. Such business affairs, papers, taxes! Do you know there was hardly any tax to pay here until after the crash?’ Duchamp spoke then about how lazy he is, how much he enjoys a placid life, and how, although he is no beatnik, he is ‘very like’. Then he abruptly shifted back to the problem of art in America. ‘We don’t speak about science because we don’t know the language, but everyone speaks about art. Art is going down to the people who talk about it. You know, about that question of success: you have to decide whether you’ll be Pepsi-Cola, Chocolat Meunier, Gertrude Stein or James Joyce... James Joyce is maybe Pepsi-Cola. You can’t name him without everybody knowing what you’re talking about. What happened to me is worse, though. That painting [meaning Nude descending a staircase, which he referred to only as "that painting" throughout the interview] was known but I was not. I was obliterated by the painting and only lately have I stepped on it. I spent my life hidden behind it.... You know, an artist only does one or two or three things in his whole life. The rest is merely filling up the hole. It is not desirable to be Pepsi-Cola. It is dangerous.’ - Dore Ashton, An interview with Marcel Duchamp, 1966

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man Ray Marcel Duchamp, New York City c.1916

"I am not going to New York, I am leaving Paris. That's quite different. Long before the war I already had a distaste for the 'artistic life' I was involved in. – It's quite the opposite of what I'm looking for. – And so I tried, through the Library, to escape from artists somewhat. Then, with the war, my incompatibility with this milieu grew. I wanted to go away at all costs. Where to? My only option was New York..." Marcel Duchamp, letter to Walter Pach, 27 April 1915

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Road Trip with Rhys and Finn Darby

At 49, New Zealand comedian Rhys Darby says he's finally found the confidence to be a leading man.

He joins Summer Times for a road trip with his son Finn.

The Route? Auckland to Nelson. The passengers? Marcel Marceau and Marcel Duchamp. The vehicle? A 1984 Land Rover.

Music comes courtesy of Finn’s indie-folk-rock band Great Big Cow.

Rhys Darby filming the TV show Our Flag Means Death at Bethells Beach (Te Henga) Photo: Samba Schutte

(click below to listen the audio)

Now based in Los Angeles, Rhys has fond memories of childhood roadies with his mum.

“We went from Pakuranga to Orewa which was lovely. We stayed in a camping ground, and I fondly remember that one because I saw a ghost and saw some big footprints on the beach.

“Bigfoot…turns out was just a big man's foot I think, but you know, when you're young.”

Last year, Darby returned home to Aotearoa to film the second season of the HBO Max series Our Flag Means Death*.

“We were in New Zealand during the rainy season, which could be any time really, last year making that.

“And it was really special because we got to be home. The first year, the first season, we were here in Los Angeles. I was 15 minutes from my house. And that was cool and then the whole show got moved to New Zealand, which was … it's a plus and minus on my account because obviously, I'll leave these guys, but I get to go to the old home.

“And it was really fantastic. Working with the New Zealand crew and just having more New Zealanders in the cast, as well. It's very Aotearoa-heavy season two. So yeah, I'm really proud of it.”

New Zealand comedian Rhys Darby hosting the 2023 International Emmy Awards Photo: chaoticmulaney

In something of a career pivot, Darby also hosted the International Emmy Awards last November.

“It was amazing because I thought 'It's not my bag. I'm not a host, I'm not a jokes guy. And I also don't kind of like rib people, my humour is very optimistic and fun. It's not like the kind of thing Ricky Gervais does where you bring people down to make light of things.

“So when they asked me I was like 'I don't know, what I'm gonna do?' I was picked because it's international and because I can do physical comedy as well. So, I wrote this monologue and also involved a lot of funny walks and some physical stuff. They worked out really well and I had so much praise from the audience and from the producers saying that was one of the best hosts have ever had.

“Because with a strict English-speaking person who's just doing quick gags, half the audience, it just goes over the head. So, what I offered was something that I guess they had more universal appeal.”

Darby currently has a number of films in the pipeline in which he takes a leading role.

“Thanks to Our Flag Means Death I've kind of proven to myself, and hopefully the world, that I can front something.

“So I want to do more like that. I want to do movies, I want to star in a film. I'm writing a screenplay this year. And I'm also involved in about three movie projects that are likely to come together this year, and which have me leading them.

“I've been a character actor for so long, and I've popped up in many, many things in small parts here and there, where I've made everyone laugh, and then I run away.

“But it's taking that next step of going, OK, imagine watching me for an hour and a half, letting me lead you down this track and have the confidence that now finally, at the ripe old age of 49, I think I can do that.”

*Max has announced that it will not be making a third season of Our Flag Means Death

Songs played:

'Iguana Love' by Great Big Cow

'Captain Boyfriend' by Great Big Cow

'The Last Song' by Great Big Cow

Source: RNZ

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kelby Clark — Language of the Torch (Tentative Power)

Kelby Clark is an LA-by-way-of-Georgia banjo player who blends divergent styles and approaches to forge his own novel direction for the instrument. Over a series of mostly self-released home-spun recordings from the past five or so years, he has honed his approach, expanding the traditions of his point of origin in the American south to include free improvisation and eastern modalities — an alchemy familiar to Sandy Bull, a fellow stretcher of the vocabulary of the banjo and of the concept of “folk” and the traditional. His sparse and appropriately fiery new LP Language of the Torch, available January 10th of next year from Tentative Power, represents a significant milestone in his development of his own science of the banjo, a statement of intent for his artistic practice. It also marks the inaugural 12” LP release from the Baton Rouge, Louisiana label.

Across the seven searching pieces that make up Language of the Torch, Clark constructs a labyrinthine world of music from solo banjo and occasional, subdued harmonium, centered around two longform tracks, “Tennessee Raag Pt.1” and “Tennessee Raag Pt. 3” – there is no part two. These songs help situate the album among its influences, the titles suggesting an imaginational space where Appalachia and India overlap, an interzone frequently visited by practitioners of “American Primitive” music. The intentionally skewed numbering invokes John Fahey, another sometime-raga-obsessive, whose volumes of guitar music are numbered in a non-sensical, non-sequential manner, thumbing the nose at the very concept of numbers and of archiving or cataloging art in volumes. Clark improvises and composes, but on Language of the Torch, the two lengthy “Raags” and the six-minute opening salvo, “Time’s Arc,” feel like the compositions that anchor the shorter, more exploratory tracks that fall between them. Clark’s banjo twangs and drones almost sitar-like during these mesmerizing endurance runs, rough edges flattening over time like water-worn limestone.

In contrast to the patience of these bucolic “Raags,” the shorter tracks on Language of the Torch have an immediacy and attack to them and entertain more old-time flourishes. The concise title cut is perhaps the most traditional, the bends and swoops here feel related to Americana, a brief nod to and deconstruction of familiar forms. Clark is a fluid player, but the percussive nature of the banjo can run counter to fluidity — the most explosive of these improvisations, “Apis,” begins abruptly with an aggressive right-hand trill before it clatters apart and back together again like a musical version of Marcel Duchamp’s Modernist classic “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” This song is a stand-out and the heaviest example of Clark’s burning vision for the banjo, the “concert instrument” ambition expressed by his forebears in the American Primitive movement.

All traditional forms of music, from Indian Classical to Appalachian Old-Time and permutations between, seem narrowly determined upon a superficial look but reveal their universal nature to those willing to let go of semiotics and sink into their visionary streams. This makes these forms excellent starting points for experimentation, established structures that contain the instructions to build new universes, if one is bold enough to try to read them, and that is what Kelby Clark attempts here with the 5-string banjo and the various traditions from which he draws inspiration. The liner notes for Language of the Torch take the form of a poem by hammered dulcimer player Jen Powers, a fellow traveler on the path of exploding the scope of the traditional. I think the passage below illuminates the process at hand, the conversation between tradition and interpreter:

And maybe now you're wondering whether you are the conjurer or the conjured, and if you really want to know which it is

Josh Moss

#kelby clark#language of the torch#tentative power#josh moss#dusted magazine#albumreview#banjo#sandy bull

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who would you want to be your mentor: Leonardo Davinci, Dolly Parton, Marcel Duchamp or Jill Thompson

duchamp

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gabriel Rico "Nimble and sinister tricks (To be preserved without scandal and corruption) I" / art critic

In February 2020, this 2018 sculpture, which cast various objects like tennis balls, rocks, and a knife within a sheet of glass, was destroyed while on view during the Zona Maco art fair in Mexico City. Looking to photograph the work, an art critic named Avelina Lésper placed a can of Coca-Cola on the piece, at which point the work came loose and shattered on the concrete floor.

Rather than apologize for the incident, Lésper made light of it, explaining that she'd wanted to take the photograph in order to relay her negative views towards the piece. “I had an empty can of soda, I tried to put it on one of the stones, but the work exploded,” she said. “It was like the work heard my comment and felt what I thought of it." She also told the artist's dealer that they should leave the piece as is and try to sell it, citing Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass. (When the French artist’s glass sculpture was accidentally damaged in transit, he declared that it was "now complete.")

In response, Mexican gallery Galeria OMR, who was showing the work, said in a statement posted to Instagram: "We do not understand how a supposed professional critic of art destroyed a work," adding that by "getting too close to the work of art to put a can of soda on it and take a picture to make a criticism," Lésper had "undoubtedly caused the destruction" and showed “a huge lack of professionalism and respect.”

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

my two cents on the modern art discourse as an art gallery worker who loves modern art and yet works at an art gallery which has soft banned modern art from displaying.

People hate ugly things.

They automatically consider something ugly to be bad.

If it was good, it was beautiful and if it is beautiful it is good.

Deeper messages? No thank you, I want to look at pretty things and I will get pissy at you if you explain that the trash on the floor (<- actual quote I was told to to my face about one of the artworks)

Even though I connected every artwork in that exhibition back to dadaism and modern art of the 80s, I wasn't able to change a single mind of someone who had already decided they hated it. They didn't care that the artist's praxis was about sustainability and using local sources to make her own paint & dye, they wanted to see landscapes made from cheap acrylics. I was in agony that the average Joe who came in didn't know who Barbra Kreuger was or who Marcel Duchamp was. They didn't want to know.

I also think anti-youth sentiment, so many people complained that it was too inner-city student, and "I'm not racist, I don't use slurs but those blackfellas who leech off gov-lov need to get a job, boohoo the stolen generation didn't have an impact!" type racism also plays a part. Like the "trash on the floor" comment was made about an Indigenous artist's work which was named in reference to the removal of certain, racist policies affecting First Nations people.

I loved these artworks, I tried to get other people to see why I loved them so much but it was an uphill battle I lost. But I did get to put my cunt of an aunt in her place so thank you for that at the very least.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024

Fluxkit

Mixed media

After looking into event scores (simply instructions, proposals, and propositions for a performance or action), I was inspired to learn more and make my own fluxkit. Like those fluxus artists, I created a collection of projects, from books to boxes to ephemera, that were framed around an event score. Those who couldn’t be tied to an object were printed in a pamphlet, inspired by Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit. I also was inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, where found objects could be repurposed as art pieces. I also wanted to recreate at the aesthetics of fluxkits, which definitely felt very based in letterpress. I experimented a bit with type but mainly focused on imagery with found vintage illustrations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I didn't want to talk about this but I must. The taped banana, Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan, has generated a global debate that is polarizing. The split of opinion ranges from an "amazing monument to the market" to the outright insult to society. In all clarity, the taped banana is not art because it elicits a reaction. It was an elaborately staged and costly satire of the art world and market, which had managed to sell multiple times for millions of dollars. The whole spectacle reflected manipulation: media, markets, promotion-legislating that everyone-I in this case-is participating in the conversation it generated. I had planned to ignore it, but the general scale of controversy is hard to look away from.

Sotheby's auctioneer Oliver Barker overseeing the bidding for Maurizio Cattelan, Comedian (2019) at Sotheby's on November 20, 2024. Photo: Courtesy of Sotheby's.

Historically, the art market has always been a means to take advantage of creativity, hailing truly magnificent and groundbreaking works. However, Cattelan managed to turn things around, getting oligarchs and institutions to spend astronomical prices on a banana taped to a wall. It's not due to the value of the piece alone but rather strategic branding and the pretension of "exclusivity". This same rule applies to luxury brands like Balenciaga when selling chip packet-shaped $1,000 or more bags with cultural elitism.

From a critical standpoint, Comedian certainly echoes the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp. However, even of Duchamp's Fountain-a common urinal signed and presented as an artwork-was couched in deep philosophical investigation into what art can be, it questioned the traditional notions of artistic creation and authorship and perpetrated a discourse that still perturbs contemporary art today. On the other hand, it is necessary to establish that the ready-mades of Duchamp were very controversial. Some even say they were highly influenced by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, a trailblazing artist whose innovative ideas were overshadowed by those of her male peers. Among those, Duchamp himself has been criticized for having stolen the ideas from her and years after her death claiming works as his own that might as well have Elsa's stamp of creativity. This history underlines how female artists have been consistently marginalized and inserts the understanding that credit and recognition of art have been positively biased towards male narratives, often at the cost of erasing women's contributions. But that's another subject.

Photo: Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images.

In Cattelan's case, the banana is not making any statement about the nature of art; it is an object commenting on the absurdity of the art market. The famous auction houses, Sotheby's and Christie's, have legitimized this kind of sale of "objects," thus further obliterating the line that separates art from market manipulation. This is where we have to underline one important difference: art is not the market. Hype, exclusivity, and the wishes of wealthy elites often override the intrinsic value that art is a creative and cultural expression.

David Datuna ate Cattelan's banana

The Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan has positive and negative facets that attribute to its controversial status. On the plus side, the piece indeed continues to stir international conversations on the value and definition of art, serving as a cultural mirror that dares viewers to question the power of media, wealth, and branding in the world of art. Furthermore, it acts as a comment on the absurdity of the art market, playfully satirizing its commodification and elitism. Yet, there are major drawbacks with the work. Its execution is shallow compared to Duchamp's ready-mades, which brought profound philosophical questions about art into the world; instead, this banana on the wall feels more like a calculated media stunt. Moreover, it exemplifies the commodification of art and perpetuates the exploitation of creativity in commercial industries. By achieving sales in multimillion-dollar figures, it runs the risk of diluting the standards of art from one based on innovation and craftsmanship toward shock value and market manipulation.

Image : Art Basel visitors in 2019.(Reuters: Eva Marie Uzcategui)

While the great comedy is a brilliant burlesque of the art market, in and of itself it is not art. It is valuable for exposing the machinations of hype and exclusivity that underlie the market in art. It does, however, demean the integrity of art as an expressive medium, an imaginative enterprise, and a cultural force by conflating this mercantile performance with artistic merit.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

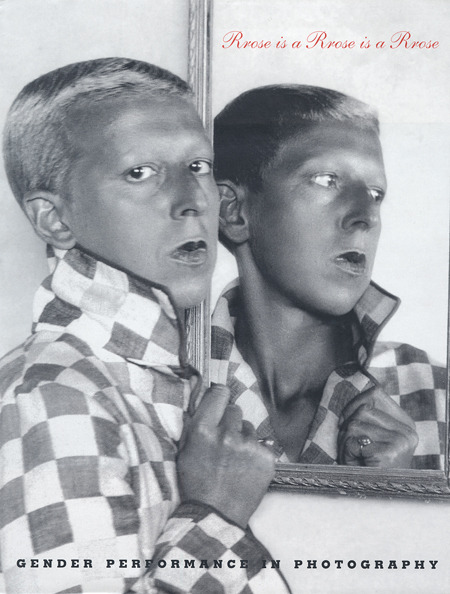

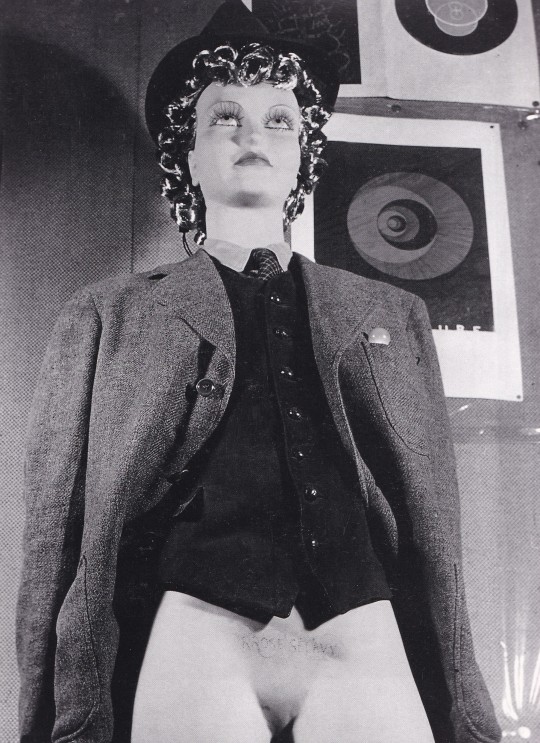

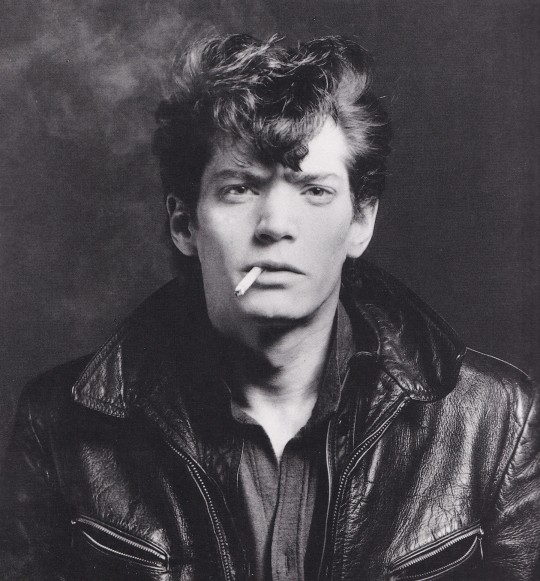

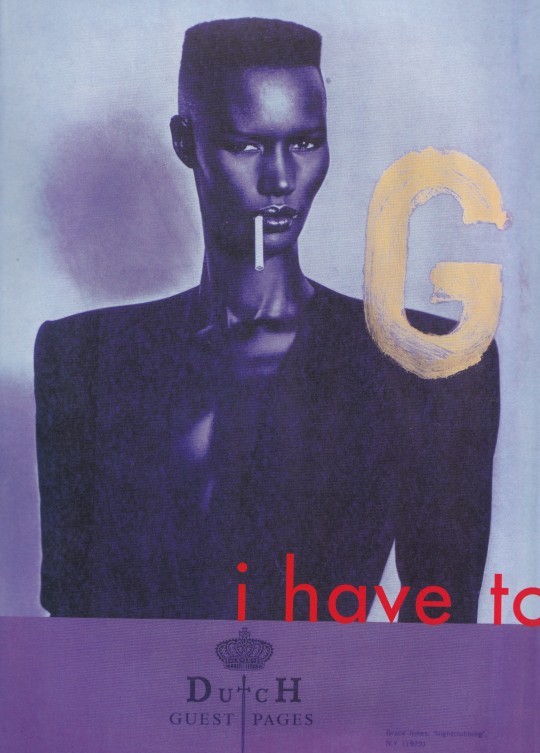

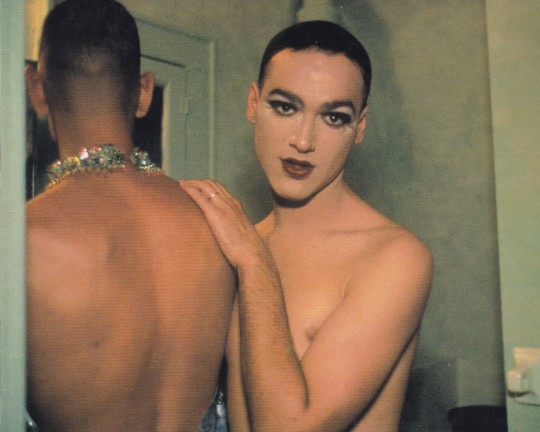

Rrose is a Rrose is a Rrose

Gender Performance in Photography

Jennifer Blessing

with contributions by Judith Halberstam, Lyle Ashton Harris, Nancy Spector, Carole-Anne Tyler, Sarah Wilson

Guggenheim Museum Publ., New York 1997, 224 pages, softcover, 27,30x33,65cm, ISBN 0-89207-185-0

euro 120,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

Exhibition New York January 17- April 27, 1997

This important volume, whose title combines Gertrude Stein’s famous motto, “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose,” with the name of Marcel Duchamp’s feminine alter ego, Rrose Selavy, features portraits, self-portraits and photomontages in which the gender of the subject is highlighted through performance for the camera or through technical manipulation of the image. In many of the works, photography’s strong aura of realism and objectivity promotes a fantasy of total gender transformation. In other pieces, the photographic representation articulates an incongruity between the posing body and its assumed costume. Features work by Cecil Beaton, Brassai, Claude Cahun, Marcel Duchamp, Hannah Hàch, Man Ray, Janine Antoni, Matthew Barney, Nan Goldin, Lyle Ashton Harris, Robert Mapplethorpe, Annette Messager, Yasumasa Morimura, Catherine Opie, Lucas Samaras, Cindy Sherman, Inez van Lamsweerde and Andy Warhol.

02/05/24

#gender performance#photography books#Beaton#Brassai#Duchamp#Man Ray#Mapplethorpe#Cindy Sherman#Warhol#fashionbooksmilano

49 notes

·

View notes