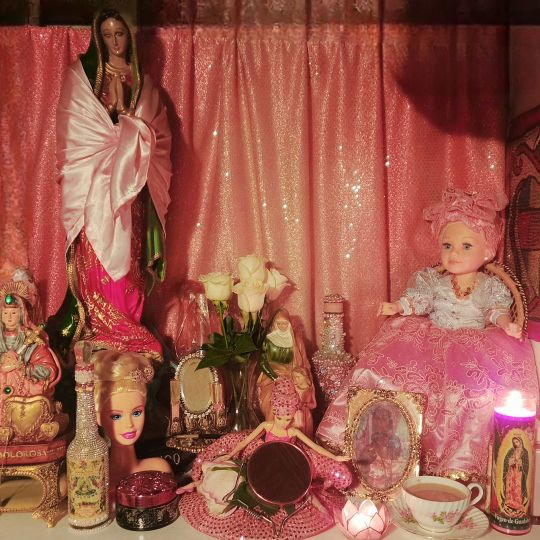

#Vodou altar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Erzulie Freda.

Okay. When I saw this I had to share it. This is from Houngan Jak. A doll of Ayibobo Mambo Maitresse Erzulie wearing beautiful real jewelry and clothing.

(If you're wondering. Ayibobo is a ritual word that's a equivalent to “Amen” or "Blessings" and a few other meanest depending on how it's used)

👇Next is a photo of her being bathed in and bath made for her.

👇This is her altar. With items that she loves.

👇Oh, Check this out a Florida Water bottle created for her.

These aren't my photo they belong to Senjsk a Vodou priest. I just wasn't to share these.

If you are a devotee of any spirit, deity, Gods, Ansestors etc Look at the things they like or tell you they like and create something personal for them that comes from you.

They'll like it.

#like and/or reblog!#spiritual#rootwork#voodoo doll#vodou lwa#vodou deities#Erzulie Freda#Vodou altar#Florida water#haitian vodou priest#haitian vodou#follow my blog#african diasporic#african spirituality#african vodu#Vodou deity#Voodoo spirit#ask me a question#message me#Message for help#Spirituality#spiritual help#spiritual guidance#Custom work

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

"WHY WON'T YOU ANSWER ME!"

Vodou or Voodoo!reader x platonic Yandere batfam

You haven't gotten out of bed in days, lying there rotting away like a bone. Your amulet, once vibrant purple, is now dusty and dark. Your bedroom is cold, and your altar is neglected; the candles are out. You haven’t put food there, fixed the tablecloth, or done anything. You haven’t prayed or performed a ceremonial dance. You've never been this depressed, this sad, or this angry; you're in despair. Ever since arriving at the mansion, you've felt your life and soul being sucked out, which is strange—you were so lively before. You feel dead, yet you can hear the chatter and laughter downstairs seeping through your thick walls. Usually, you drown it out, but today you listen. You can feel their smiles, their joy, their anger—everything, yet you're not present.

“Why don’t you go down there?” a spirit says, its ghostly hand caressing your shoulder.

“They don’t want me there; you know that already,” you say, your voice cracks. Of course it did; you were crying for hours, maybe even longer, but better not count. “Don’t be like that; they’re your family.”

You scoff at what the spirit says. You want to slap its hand away, but you obviously can't touch it; you can't even feel it, just the cold air that caresses your dark skin.

“I’ll only ruin it,” you say, hovering overhead, letting your despair consume you. If you continue like this, how will you become a great Priestess? Your altar has no gifts, no offerings. You haven’t fixed your hair in days; you haven’t sent us anything, and we love your voice. “Please, my child,” the spirit pleads, “you do not want to go down there. At least do something.”

You don’t answer again. You curl up into a ball. The spirit sighs. “As you wish, young Priestess,” and they disappear into purple smoke. But all you can think about, deep in your head, is that it just isn’t fair. You’re a nice kid; you’re sweet, you’re kind, you’re honest, you’re polite—the nicest of them all. Even if there was a niceness contest, you’d come out on top, leaving everybody in your wake. But your father seems to favor the ones who are cruel, mean, and rude. Your younger brother, Damian—a little devil, held you at swordpoint, threatened to kill you, called you a bastard, and you’re supposed to forgive him with open arms? What kind of idiot does Bruce take you for?

And your older brother, who prides himself on family, barely even knows you—the sucker might have to look up your middle name, maybe even your birthday, on some celebrity website. He’s always spending time with the little devil; you have no clue why. You’re way more fun to hang out with than him. But who cares? And your second eldest brother is rude, scary, and he smells like pure death, as if he crawled out of his grave, clutching dirt from the ground beneath him. It makes sense—his eyes are naturally green, just like Damian's, but he’s alive. It just doesn’t make sense. Maybe Papa Legba, but him cross without knowing.

And the brother who is the same age as you, Timothy, makes you snore when you hear his name. He’s intellectual, so smart, and yet so stupid, so dumb, and so hypocritical. He’ll find everything and anything to correct you on, even if you’re right, just to ensure that you’re slightly off the mark. The brother you thought you would have an unbreakable bond with is so tight he cut off blood circulation; yet, this bond is flimsier than a piece of string. He’s always talking with Cass, and you're never invited. You have more in common than they think, but to them, you’re just another bastard of Bruce Wayne—Cass, Steph, and Babs are your sisters. You’re supposed to gossip, talk about boys, play hand games, and hold each other, but they are only close with each other and not you.

I mean, trios were never meant to be broken; who even wants a quartet? You pray to Bondye every night. You expel all the darkness within your amulet, and your wishes are always the same each night: “Please, Supreme Lord, let them greet me with open arms; let them see me as their kin; let them love me; let them notice me.” But each night, you are met with nothing but silence. Bondye is quiet, and so are the loa. They always talked to you, but whenever you beg for this family to see you, they can never answer; they can never give advice. At first, you thought it was a test—a series of trials you had to go through to prove that you were worthy of their love. So whenever you were met with hostility, it was like the sharp end of a blade. You opened your arms to them; the trials got harder, and it started to become impossible.

Maybe I have to go in a different direction; maybe meet force with force. But then you get scolded. Maybe you just don’t fight back, but if you don’t, then you will be forgotten. So what next? How do you pass this test, these everlasting trials? You have no clue, no idea, and in fact, you feel lost, and you start to lose faith. Maybe you were just not meant to be loved; you weren’t meant for affection, you weren’t meant to be held, dear. So you let that bitterness and anger swallow you whole as you wallow in your own sorrow and self-pity. This young High Priestess is filled with hurt.

#x black reader#weird!reader#black!reader#batfamily x neglected reader#x neglected reader#yandere batboys#yandere batfam#yandere batfamily#black fem reader#magical!reader#voodoo!reader#voodoo#vodou#haitian vodou#vodou!reader#dc comics#dc fanfiction#dc fics#dc headcanon#yandere jason todd#yandere tim drake#yandere dick grayson#yandere duke thomas#yandere cassandra cain#yandere stephanie brown#yandere barbara gordon#yandere bruce wayne#yandere batman#yandere dc#black tumblr

579 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death Witchcraft: An Exploration

Death witchcraft is a branch of occult practice deeply connected with the mysteries of life, death, and the transition between the two. It involves working with the energies surrounding death, the afterlife, ancestors, spirits, and the unseen realms that lie beyond physical existence. The practice is often misunderstood due to its association with darkness, fear, and taboo. However, death witchcraft is a deeply transformative and powerful path, one that offers healing, guidance, and a deeper understanding of existence and mortality. It is not necessarily about harming others, but rather engaging with the sacred and mysterious forces of life and death in ways that can lead to empowerment, spiritual growth, and the honoring of those who have passed.

Core Principles of Death Witchcraft

Death witchcraft revolves around several key principles:

• Honor and Respect for Ancestors: Ancestor veneration is an integral aspect of death witchcraft. Practitioners often work with ancestral spirits, seeking guidance, wisdom, and protection from those who came before them. Through rituals, offerings, and prayers, death witches maintain strong connections to their ancestors, ensuring their spirits are honored and respected. This work can help heal generational trauma, discover hidden family wisdom, and preserve the energy of the ancestors within the practitioner’s own lineage.

• Reverence for the Cycle of Life and Death: Death witchcraft embraces the natural cycle of life, acknowledging that death is as much a part of life as birth. It does not seek to control or avoid death, but rather understands and respects its role in the cosmic order. Death witches work with death as a transformative force—whether through spiritual transformation, endings, or transitions. Their practice includes rituals for rebirth and regeneration, as well as rituals to honor the dead and assist them in their journeys to the afterlife.

• Communion with Spirits: Death witches frequently engage in communication with spirits, especially those of the deceased. This can include ancestral spirits, beloved departed, and even spirits who may still be trapped between worlds. Communication is facilitated through divination tools like spirit boards (ouija boards), pendulums, scrying, or simply invoking spirits during meditative or ritual work. Some death witches work as mediums, facilitating communication between the living and the dead.

• Working with the Underworld and Deities of Death: Many death witches also work with deities or spirits associated with death and the underworld. In various cultures, these deities are seen as guides for the dead, as well as rulers of death and the afterlife. Deities such as Hecate (Greek goddess of the underworld), Hel (Norse goddess of the dead), Anubis (Egyptian god of mummification and the afterlife), and Baron Samedi (Haitian Vodou loa of the dead) are frequently invoked in death witchcraft for their wisdom, protection, and assistance in working with death-related energies.

• Rituals and Ceremonies: Death witches often perform rituals and ceremonies to mark and honor death. These may include funeral rites, memorial services, or specific rituals that allow the practitioner to connect with deceased loved ones, guide souls into the afterlife, or work through personal grief. Rituals can be solitary or communal and may take place in sacred spaces such as graveyards, cemeteries, or even the practitioner’s home altar.

Magickal Practices in Death Witchcraft

• Necromancy: A cornerstone of death witchcraft is necromancy, the practice of communicating with and working with the spirits of the dead. Necromancers—often considered to be death witches—may use tools like spirit boards, pendulums, crystals, or scrying mirrors to summon and communicate with spirits. Necromancy can also involve rituals to help spirits move on, protect the living from malevolent spirits, or gain insight into future events by consulting the deceased.

• Spirit Work: Spirit work goes hand in hand with necromancy, though it is not always about divining or commanding spirits. Spirit work in death witchcraft involves developing a deep relationship with the spirits of the dead, listening to their messages, and sometimes offering spiritual assistance. Death witches may dedicate spaces on their altars or in their homes to honor these spirits, offering food, trinkets, or symbolic items to maintain good relationships and receive guidance.

• Psychic Development: Many death witches develop their psychic abilities to perceive spirits, energies, and otherworldly dimensions. This may involve cultivating clairvoyance, clairaudience, or clairsentience (the ability to perceive spiritual energy or communicate with the dead). Through meditation, divination, and dream work, practitioners can enhance their sensitivity to the spirit world and develop the skills necessary to work with death in a more intimate way.

• Death-Related Divination: Death witches often use divination to understand the mysteries of life and death. They may practice tarot, runes, or bone reading, methods in which the symbols or objects used represent the interconnectedness of life and death. For example, certain tarot cards like Death or The Hanged Man symbolize transformations, endings, and rebirths. Practitioners may turn to these tools to gain clarity on matters of life transitions, cycles, and endings.

• Baneful Magick: Some branches of death witchcraft include working with baneful magick—spells meant to harm, curse, or protect against malevolent forces. This can involve using death-related symbols, graveyard dirt, or other elements connected to death. However, these practices should be approached with caution, as they are often considered ethically and spiritually dangerous, carrying consequences that may affect the practitioner.

Death witches can be spiritual guides for those dealing with grief, loss, or personal transformation. In many cultures, they may serve as shamans, healers, or mediators between the living and the dead. They may be called upon to perform rituals for the deceased, help souls find peace, or provide guidance to the living regarding their own mortality or transitions.

They also play an important role in facilitating spiritual healing. Many death witches assist individuals in releasing attachments to loved ones who have passed or help them make peace with death. They may use rituals to help heal grief or even to address fears surrounding death. By acknowledging and embracing death, these practitioners help others live more fully, knowing that death is an inevitable part of existence.

Although death witchcraft can seem mysterious or dark, it is not evil. In fact, it is an inherently respectful practice that seeks to understand, honor, and make peace with the natural world’s cycles. However, as with any form of magick, it is crucial that practitioners approach death witchcraft with respect, responsibility, and reverence for the forces they work with. Working with spirits, especially those of the dead, requires a deep level of discernment, sensitivity, and ethical awareness. Practitioners must be cautious when invoking spirits, ensuring they maintain healthy boundaries and avoid harming others.

Death witchcraft is a deeply transformative and sacred path that connects practitioners with the timeless mysteries of life and death. It is a practice that encourages reverence for the dead, for ancestors, and for the cycle of existence itself. Through communication with spirits, necromantic practices, and rituals focused on transformation, death witches help others understand their relationship with death and the afterlife. The practice offers spiritual growth, healing, and empowerment, guiding both practitioners and their communities to embrace death as a natural part of the human experience—an experience to be honored and respected, not feared.

#death witchcraft#death witch#death work#spirit#spirit work#necromancy#necromancer#witch#magick#satanic witch#lefthandpath#witchcraft#dark#satanism#witchblr#witch community#psychopomp#eclectic witch#eclectic#pagan#esoteric#occulltism#occultism#occult#demons

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

House of Voodoo - A CC collection

I finally re-worked my House of Voodoo set ! In the process of remaking my Voodoo shop lot, I got inspired to make some new recolours to decorate the lot and give you more voodoo/vodou original content. This set is required for the lot to function as intended.

Set info & Download ⬇

This is a set of 7 objects (recolours only).

- 1. Powerful religious figures portrait. 10 swatches. I think you need Living Together for that one. I’m working on more swatches, stay tuned ! - 2. Vodou flags/drapo. 10 swatches. Pretty sure it’s BGC.. - 3. Vodou posters. 10 swatches. Requires University! These are the ones you can spot on the shop’s wall ! - 4. The Book of Voodou. This is a bit of an experiment, I wanted to try myself at retexture non-flat objects. MESH REQUIRED *find it here* (you only need the botanical book open book) - 5. Entrance sign (’Strange gods, strange altars’). Base game compatible. - 6. Marie Laveau’s shop neon sign. Requires City Living ! also it’s a bit big but ya know, just shrink it. It’s not perfect especially when it lights up at night but I like it the feeling of it! - 7. Vévé (traditionnal Vodou sigil). Requires Realm of Magic! 5 swatch, find it under ‘rugs’. I’m working on more swatches ! I’m also trying to transform it into a meditation spot, if anyone knows how to do that...

Download (Patreon, free, no ads)

#voodoo shop#voodoo#ts4cc#ts4 paintings#ts4 decor#sims 4 cc#ts4 simblr#ts4 witch#sims 4 custom content#marie laveau#ts4 halloween#simblreen#sims 4 realm of magic#mycc#new orleans

149 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hii ik saw me many times but i love your blog so much about hobie and Miguel i have questions have any hc hobie being west African hc of that been there since watched movie i cannot get it out

I AM GOING TO SCREAMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM AT THIS BECAUSE YES YES I CAN

(also sorry if this is kinda Yoruba centric!! cause that's the area I know the best - for reference I myself am Bajan/Quechua (West Indies - Barbados / Indigenous Peruvian))

West African!Hobie Headcanons:

And because I'll never get a chance to talk about this again I'm gonna start off with the one I love most and the one people know most about (and that is demonized - literally - the most)

Hobie and Vodou (aka VooDoo):

Yeah, I said it. Hobie can work. He got juju. He rootworks. He conjures. Whatever iteration, whatever title - if Hobie followed any religion it would either be Buddhism, which some argue that some sects can double as a moral philosophy,

-If he'd respect any religion. It'd be a Traditional African one and I'm putting money on Vodou.

[And heads up, I am not an initiate of Vodou, but I do actively practice African Traditional Spirituality (HooDoo/Rootworking) and Ancestral Worship. So take from that what you will.]

First of all - how punk would that be??? A West African religion demonized by the western world for centuries from Africa to Haiti to Louisiana - that praised ancestral worship and community first???

YES PLEASE. Some people might not really understand all of this but:

First things first, yes, he speaks Yoruba and if you call it 'Speaking African' he's going to flay you alive.

Like????? Hobie sweet talking in Yoruba??? I'll throw my self on the floor right now!!

Hobie practicing ancestor worship - and thanking all the oppressed people who gave their lives and suffered daily so he can live his life?

He'd have an altar in his house, a small one he keeps out of sight, even to Gwen.

Leaves offerings and bits of his meal on the altar. Cause he was once food insecure, but now that things are a little better, he can do that

Like even if he practiced a form of HooDoo or another sect that derives from Traditional African Spirituality (that doesn't involve initiation)

He'd want to give back to his ancestors, learn how to use natural herbs and work them, learning how to make powders, doing floor washes, sweeping a certain way

And having all of these routines related to his African spirituality that are so subtle but he thinks about always

Prays to his ancestors to give him strength when he's struggling with being Spiderpunk

BUT IMAGINE IF HE WAS INTITATED THO ????

Hobie in all white during ceremony???????

HOBIE BEING A CHILD OF SHANGO??????????

NAH THEY AINT READY FOR IT

But even so -whatever Orisha got that boy head be putting in WORK.

And you know he keeps his beads on forever and always even under the suit!!!!

And the style!!! Hobie AfroPunk?!!!

I don't know if they have this elsewhere, but in NYC there's a music festival called AfroPunk - and it's full of black artists, and black people come out in these amazing outfits - and the goal is to incorporate as much African influence as possible

HOBIE WOULD EAT THIS UP.

The inside of his vest being lined with African textile!!

He takes it off in front of you and you see that little pop of that of classic orange-gold color

You just know he's wit it!!!

And the BEADS

(He should wear beads he's royalty compared to the raggedys at HQ)

[Cough] red and white shango beads [Cough]

Imagine Hobie giving his girlfriend a coral bead bracelet too AWWW

And telling them the significance??!!

He loves a woman in a headwrap. GELE ESPECIALLY but any type

And if you wear waistbeads UMMMMMMMM

As soon as he sees it peeking from under your shirt - IT'S GAME OVER

He's gonna wanna test if they working how they supposed to IF YOU KNOW YOU KNOW.

AND The FOOD!

First of all - Hobie hates that British manners shit.

Was raised eating with his hands and loves it

He hates old white people who wanna stare cause he eats with his hands

He loves goat. Not me projecting he LOVES goat.

He really appreciates rice based dishes because they can fill you up - and you can't just buy them anywhere

Prefers Waakye to Jollof Rice but still loves Jollof

With FUCK UP some Fufu if he can get it

I say he eats standing up so he's just there at his kitchen counter eating Fufu and the most random shit in his fridge???

Like he'll be eating left over KFC with fufu - like what are you doing??? Thats - not a meal bro

He loves Okra (ew nasty ass) and he'll eat it all the time.

Especially fried okra but okra soup is cool too he's fine with that

His fried plantains go INSANE. They go SO HARD. They're to die for

He always picks the sweetest ones and it cooks them till they're all caramelized and shit YUMMMMM

(can you tell I like my plaintains sweet and soft cause I DO)

Extra Headcanons

He was not playing that when Gwen first came over - as soon as she stepped on the houseboat with shoes he was like "Girl-"

The first time Peter B. heard him speaking Yoruba he went "Wow, Hobie, Your Nigerian is great!"

Hobie, who already hates Peter B, looked at him like he was the dumbest mfer on earth like

'Right, and you speak American, right? Fucking bellend. I hate you. 'Nigerian'. It's Yoruba.'

(He's only saying that cause he hates Peter personally and wants him to have a bad day)

Meanwhile Gwen was nice enough to just ask "What language is that?" (The correct way to do it, do not assume language names like Peter)

First time he went over to Peter B.'s place (on Gwen's insistence), Mary-Jane accidentally swept over his feet before setting her purse on the floor

and in the moment he knew he had to leave.

He's a streetkid, but since he's in the neighborhood so much he has like 45 different women he calls auntie - and they make sure he has good food to eat because 'you are so skinny! you need to eat more.'

He does that auntie shit where you're walking with him and you see someone you know and now they're in a long ass conversation

Or when he says 'goodbye' then stands by the door having a conversation and you're standing there in your coat like....'fam are we out or not cause i can sit back down'.

He always goes to meet the elders of whatever house he's in to introduce himself, very respectful of black elders and enjoys helping old the older black folk in his neighborhood.

He enjoys giving them respect and hearing their stories, helping around the house. Plus he gets great food out of it

ANNDD That's all of them I think!! Sorry if any of these were off the mark - a lot of these are from personal things I know about West Africa and things learned through Spirituality. I hope I got everything okay!

Thanks for this by the way I LOVE Hobie and culture you know he'd be SO proud!!

[If you've read this far - maybe take some time out to learn a bit about African religions - they're beautiful practices (open to black people - we're worshipping black ancestors) - but you can still learn about them and understand how modern culture often demonizes these types of religions. If anything, I hope you learned a little from this! Hoodoo, Vodun (VooDoo), and Santeria (Latino witchcraft) are not scary, dark practices!] And because I spoke about spirituality, imma put this here cause DO not be playing yknowwhatimean

🧿

#I love talking about African Spirituality I hope I did it alright and justice#Most Vodou practitioners I know are Haitan so excuse any differences#no proofread as usu#hobie brown#hobie brown headcanons#spider punk#spiderpunk#across the spiderverse#atsv#across the spider verse

148 notes

·

View notes

Note

I am not Haitian, and practice a non-Vodou form of spirituality. For some reason, I have a strong feeling that Papa Legba has entered my life and blessed me. I feel a strong urge to thank him by doing something in return. What is the best way to express my gratitude? Is it appropriate for me to leave offerings for him in my altar, or would that invoke his ire? I do not want anything in return, I just want to serve him.

Stuff for the lwa really shouldn't go on space utilized for any other reason; they are less likely to be enraged and just more uninterested.

Charity is always a good option and honestly one of the best for folks who want to give but are removed from a community to support them. Make a donation in his honor or do volunteer work in his name. The lwa love charity, and request it often from their children.

Charities, nonprofits, and NGOs that help Haitians are a great choice. Some places to donate that I really like and that are reputable:

MamaBaby Haiti: This nonprofit is one of very few organizations in Haiti providing prenatal, delivery, and post natal care to pregnant people in the country. Haiti has an incredibly high infant mortality rate due to the lack of both providers and medical facilities to assist with birth. MamaBaby Haiti provides free care to any pregnant person who shows up AND they train midwives who can serve in their own communities. They have built birthing centers and they go by car, boat, and donkey to remote communities to provide care to people who cannot reach them. They additionally pay to get folks who deliver in a hospital out of 'hospital jail'; if you receive care in a hospital in Haiti and cannot pay, they lock you in and refuse to let you leave until you do which means people who have just had c-sections are sleeping on open porches on the floor with their newborns because they cannot pay the bill. MamaBaby Haiti will pay that. They are in desperate fundraising space right now; their operating costs are about 50K USD/month due to the incredibly high cost of everything in Haiti, and they have started shuttering their centers which serve literally thousands of people per month. You can see a lot of their work on Instagram, too, at MamaBabyHaiti.

P4H Global: this org trains teachers in Haiti, which is important work, but the founder (on IG as Bertrhude) has been a one woman fundraiser to provide support for the Kanal Pap Kanpe/The Canal is not Stopping movement. The local food economy has been decimated by food surplus donations from foreign countries, and local farmers have lacked infrastructure to be able to develop local crops to sell. Three canals have been or are being built in communities that rely on agriculture to survive. Berthrude has been tirelessly fundraising to provide materials--cement, steel, gravel--and paychecks to the communities who are building them. This has had tangible results; Haiti was once known as a rice-growing country, and that is returning. The canals have been able to provide the flooding necessary for rice, and as of today the second harvest is underway the KPK (Kanal Pap Kanpe) rice. The price of a sack of local rice in the north has dropped from roughly $1500 local dollars to $1000 local dollars, which is a MASSIVE drop in a country where many people survive on $100 local dollars or less per month. Berthrude has been transparent in her financial tracking and the amounts raised are truly incredible.

Haitian Bridge Alliance: this org has been active at the US southern border aiding Haitians and others who arrived seeking entrance. They have helped innumerable folks navigate the Biden program and have provided free legal services to basically any migrant they come across at the border. Currently, they are in communities in Mexico doing ad hoc 'know your rights' community meetings for Haitians wanting to cross. Additionally, their legal team has successfully done big things like sueing corrupt Haitian government officials in international court for crimes against humanity.

Health Equity International: this org funds and supports one of (I think) 4 free hospitals in the entire country, and that hospital (St Boniface) has the only spinal cord rehabilitation clinic in the country, the only NICU in the country, the only 24/7 trauma operating room in the country, and currently 1 of 2 emergency rooms in the country. Their work is astounding. I personally know people who would have died witho their care.

If you cannot donate money, donate your time and labor. Any organization that provides shelter to unhoused families in the US or Canada is receiving Haitians from the border and needs volunteers. Food resources like food pantries, soup kitchens, and community meals always need hands. If you can't do physical work, coordinate a diaper drive for your local family shelter or a winter coat drive (70 degrees feels cold for just arrived Haitians...). Make sandwiches for street outreach teams. Donate bilingual children's books to your local library. Stuff like that is gold to the lwa.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

curly showing pony voudou???

ok so i dont hc the shepards to like, practice vodou THAT much honestly, but they do have some practices from haitian vodou and ill talk about 2 of em

the shepards have an altar in their house for ppl theyve lost, and the shepards let pony add johnny onto it too, the altar is for honoring and communicating w the dead and u can put pictures, personal items, and u can put offerings on it as well!!! whenever he comes over he adds something to it for johnny

theres this candle that u can write the name of ppl who wronged u and u just let it burn till the wax gets to their name and angela would have that candle but tim uses it sometimes too, as extra measures in case his own version if karma wasnt enough for the world and they wanted to help him out

i think them having each others vodou dolls could b cool (and just to let yall know, vodou dolls r used for protection, its not what u think, they r usually blessed and used for positive outcomes)

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Saw your book post and I think you've confused a few things...

You seem to mix up Hoodoo and Vodou a lot. They are not the same. Hoodoo is not a closed practice nor religion. It's just fking weird and poser-ish if someone claims it without ever growing up in the culture for it. But many Hoodoo practioners will tell you their practice is not closed. Vodou/Santeria is closed.

Also saying to be careful not to fall into Hoodoo while doing Conjure... you know rootwork is similar across all cultures right? This just feels like a gatekeeping statement and prevents people from really digging into their folkwork by making them constantly worried they're appropriating.

The thing with smudging: you make no mention of which kind of smudging is closed. You just said it generally, which is a bit ridiculous. Burning herbs for the sake of energy and cleansing is not inherently a Native Indigenous practice. Bayabas, or guava leaves, have been used in the Philippines pre-colonialism. Frankenincense in Europe and Old Christianity. Ti Leaves in Hawaii. Rose in Ancient Rome, and Blue Lotus in Ancient Egypt. As a latina, and as half of one myself🇨🇺, we both know our people love to use incense at altars. SAGE, particularly white sage, is where the line is drawn. Same with palo santo. I agree with your points, but I think you need to be specific if you're being critical.

Much love from 🇵🇭✨️

Hello there anon! I see you sent another ask apologizing for assuming I was Latina, and you're quite forgiven! I am as they say white as white can be.

As a white person I went to an American BIPOC friend of mine in order to answer all of this as honestly as I possibly could. Hoodoo by means of origin IS a closed practice. It's roots come from Ghana and was created in America as a very specific response to slavery. Both Hoodoo and Vodu are tribal/family based, and both require a initiation of sorts through community in order to practice them. Vodu's roots are in Haiti, and through community, enslavement, and initiation needed through the "family" as some groups of Vodu practioners call themselves, are required therefore it is also closed. I shall include some links below to help with the distinction of Hoodoo and Vodu and why they are both closed practices/religions. Hoodoo could be considered a religion in Louisiana specifically due to it's usage there and sometimes it's blending with Vodu. https://medium.com/@empressnaima/my-hoodoo-initiation-5086e375e378 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoodoo_(spirituality) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Vodou https://cswr.hds.harvard.edu/news/magic-matters/2021/11/10 https://brizomagazine.com/2020/06/15/the-appropriation-of-magic-how-white-people-demonised-voodoo/ Now that I've cleared up through BIPOC voices/history/links on why Hoodoo is in fact closed...let me address the specific comment of

"You know rootwork is similar across all cultures right? This just feels like a gatekeeping statement and prevents people from really digging into their folkwork by making them constantly worried they're appropriating." Rootwork in of itself is a Hoodoo term iirc, but I may be wrong on that front. As for worrying about appropriation...white people SHOULD BE worried about appropriating. Hell currently in America we still through simply social climate and judicial systems are failing our BIPOC/Indigenous communities.

As a folk worker who has some herbalism that stems from Cherokee and Creek peoples I am so beyond careful to make sure my practice is not appropriating from them. White people demolished them, slaughtered them, and took away their homes and sacred spaces, hell, we stole and demolished their LANGUAGE. And you're telling me I don't need to worry about taking anything else from them? The best option is to contact the people you believe is being appropriated from and just...asking them. Wild concept I know. Make friends that are not from your station! Send emails and letters to community leaders in these appropriated cultures in an honest and respectful way to see if what you're studying is appropriated. A good example of this was I found recently an ancestor of mine worked closely with what she called "Grandmama Spider". Grandmother Spider is a Cherokee creation deity. Referencing the above horrors and terrors us white folk did and are still doing to the Cherokee people...I will not be following in her footsteps. Individuals like Cat/Catherin Yronwode has perpetrated that Hoodoo is open, and has caused catastrophic issues with her large standing in the American Folk Magic world. A link to an open letter about Cat Yronwode and her severe appropriation/dismissal of the real history of New Orleans Voodoo being "fake" and "not a slave based religion" is here: https://conjureart.blogspot.com/2013/10/open-letter-to-cat-yronwode-and-lucky.html I don't want to pick on any specific religions/groups of people but all you have to do is read through ONE "witchcraft for beginners" book written in America or England and find at least two stolen items from Indigenous Americans AND the BIPOC/Black community. It's THAT common. Totems and Spirit Animals? Not entirely Indigenous but the ones these authors are teaching about ARE. The same goes for the word smudging, when I mention a book has smudging in it I am talking about white sage. White Americans love to use their white sage with an illegal owl feather and a shell to hold their bundle of sage in. The word smudging in of itself comes from the 15th to 16th century Germanic language and was actually talking about using smoke to rid a home or building of insect infestations. The word we SHOULD be using for cleansing with smoke should simply be...smoke cleansing. It avoids the person reading from having to guess if it's appropriated or not.

Having said all of that I guess all of this boils down to one thing: Listen to the voices of the cultures first. If they say something's appropriated? Stop. If they say it's closed? Stop. I have no authority on anything at all, but if I can speak up just once and give others a platform to say, "Hey this is kinda fucked up" I will. It's the least I as a white person can do.

#witchblr#appalachian folk magic#folk magic#buggy answers#tw: slavery#tw: appropriation#tw: atrocities#Whew this one took a while.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

More Pics From Fet Gede.

#fet gede#vodou ceremony#lwa spirits#gede spirits#spiritualism#voodoo altar#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#african diasporic#african spirituality#new orleans voodoo#voodoo ceremony

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

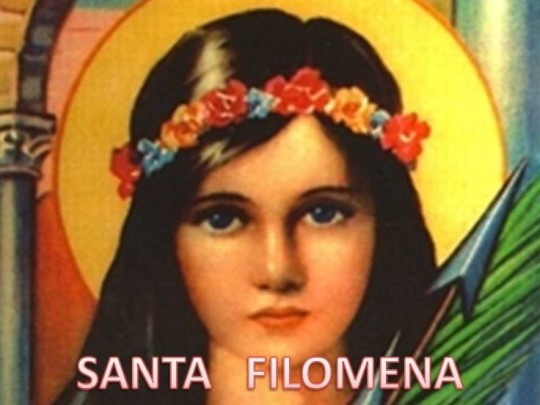

Lubana is a cemetery spirit; the sacred snake of the charnel house. She is a spirit of birth, death, life, and sex who unblocks roads, removing obstacles from the paths of her devotees. She opens the gates of opportunity. Lubana is a cleansing spirit who removes negativity and spiritual and psychic toxins (snake venom as antidote). Can she remove a curse? Yes, she can.

Lubana began her incarnation as a Congolese Simbi spirit. Transported to the island of Hispaniola by the slave trade; she was a comparatively obscure local spirit until the late 20th century when the image of Mami Waters arrived in the Americas. The German circus poster of a snake charmer that catapulted Mami Waters to worldwide fame served as a portal for Lubana, too. Dominican immigrants brought Lubana to the United States; her fame continues to increase.

Congolese snake spirits were transported to the Caribbean; so was an old traditional style of Iberian spellcasting, incorporating verbal petitions to aggressive spirits requesting that they impose the spell-caster’s will on others. For instance, Spanish love/domination spells invoke Saint Martha the Dominator, requesting that she force an errant man to return to the spell-caster so subservient that he’s crawling on his belly like a snake. Lubana is now invoked in virtually identical love-spells whose goal is to force a man to crawl afterthe woman he once scorned, begging on his knees. (If the spell goes correctly; the man wants to do this. He feels compelled. He’s unresisting.)

Although Lubana is also commonly called Filomena, she is not identified with the young virgin martyr, Saint Philomena. Instead, she is syncretized to Saint Martha the Dominator. In Latin America, the snake-charmer image associated elsewhere with Mami Waters was identified as Saint Martha who is usually depicted with a dragon or great reptile.

Snake Oil, a mass produced condition oil (magical formula oil), is used to dress Lubana’s candles and summon her. Serpentine-inspired fine perfume oils like Black Phoenix Alchemy Lab’s Snake Oil may also accomplish this purpose. If you want to visit her, Lubana lives in the cemetery.

The other names she goes by: Filomena Lubana; Maitresse Luban; Metresa Lubana; Loubana; Luban

Classified as a Metrasa- the Caribbean island of Hispaniola is divided into two nations: Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Although Vodou has historically been associated with Haiti, related traditions exist in the Dominican Republic, too. The Dominican tradition is usually spelled Vodo or referred to as the twenty-One Divisions. Metresa is the term used to describe Vodo female spirits. It is a Spanish adaptation of the French word Maîtresse or, in English, Mistress.

MANIFESTATION:

Lubana’s true form is a snake but she may also manifest as a woman who displays serpentine behaviour (hissing, slithering, sticking out her tongue …). She may have snakelike physical features. Regardless of form, Lubana doesn’t speak: she hisses or communicates telepathically. (Telepathically she may use words and be quite articulate.)

ICONOGRAPHY:

The image most frequently used to depict Lubana is that of the snake charmer more commonly associated with Mami Waters. Votive statues based on that image are now mass produced and may be labeled Martha the Dominator (Santa Marta Dominadora). Different versions of the statue exist; some hew closely to the old poster even duplicating the hairstyle; others depict her with significantly fairer complexion. Martha/Lubana wears a green dress and holds a snake. A small boy sitting on her lap holds a smaller snake. The second figure in the old poster has been reinterpreted as a child saved from a snake by the snake charmer.

SPIRIT ALLIES:

She works closely with Anaisa Pyé, Sili Kenwa, Baron Del Cementario, and other Barons.

DAY:

Monday

SACRED DATE:

29 July (feast day of Saint Martha)

COLOURS:

Green, black, purple

ANIMAL:

Snake

NUMBER:

5

ALTAR:

Her offerings are traditionally placed on the floor, although theoretically, a snake climbs anywhere.

OFFERINGS:

Cigars; unsweetened black coffee; Malta beverage (not malt liquor; Malta is a type of carbonated drink whose primary ingredient is barley, which is allowed to ferment or ”malt”). Malta is available worldwide, sold under different brand names; it may also be sold as champagne cola, although it’s neither champagne nor cola; however, beware: although Malta may be called champagne cola, not every champagne cola is Malta.

TRADITIONAL OFFERING FOR LUBANA

Place one whole, unbroken, raw egg on a bed of coffee grounds

Drizzle with honey and Malta and serve

6 notes

·

View notes

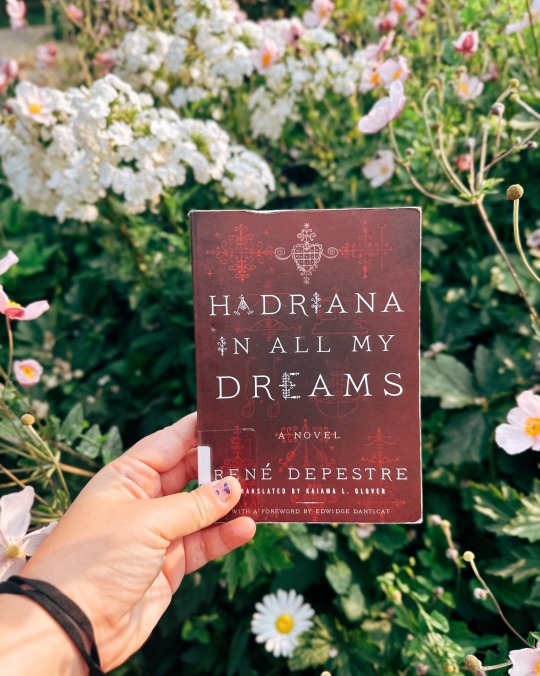

Text

This autumn, read about a different kind of zombie. Hadriana in All My Dreams by René Depestre, translated by Kaima L. Glover, is short, wild, and fun.

As I wrote for Book Riot: "It’s 1938 in the town of Jacmel, and a beautiful young French woman named Hadriana is getting married. But when she falls dead at her own wedding altar, the celebration becomes a funeral, and Vodou culture comes to the forefront as the town worries about the possibility of someone trying to zombify the gorgeous young woman who died too soon, sharing their own stories of zombies and the supernatural. It’s a book full of sex and surprises, a short read that is part nostalgia, part ghost story, and part satire." (Content warnings for sexual violence/rape, death.)

Can’t get enough of Haitian zombies? Dive into Dézafi by Frankétienne, translated by Asselin Charles, a politically-charged, poetic story about a daughter of the owner of a zombie-run plantation who tries to reanimate one of the workers—and accidentally unleashes a rebellion.

#hadriana in all my dreams#rené depestre#books in translation#translated literature#haitian literature#my book reviews

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion

Abstract

Historical scholarship on Afro-Cuban religions has long recognized that one of its salient characteristics is the union of African (Yoruba) gods with Catholic Saints. But in so doing, it has usually considered the Cuban Catholic church as the source of the saints and the syncretism to be the result of the worshippers hiding worship of the gods behind the saints. This article argues that the source of the saints was more likely to be from Catholics from the Kingdom of Kongo which had been Catholic for 300 years and had made its own form of Christianity in the interim.

Acknowledgements

Research funding for this project was supplied by Boston University Faculty Research Fund and the Hutchins Center of Harvard University. Earlier versions were presented at the Hutchins Center, and the keynote address at ‘Kongo Across the Waters’ in Gainesville, FL. Thanks to Linda Heywood, Matthew Childs, Manuel Barcia, Jane Landers, Carmen Barcia, Jorge Felipe Gonzalez, Thiago Sapede, Marial Iglesias Utset, Aisha Fisher, Dell Hamilton, Grete Viddal and Kyrah Daniels for readings, comments, questions and source material.

[1] Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy (New York: Random House, 1983), pp. 17–8; see also Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and African America (New York: Prestel, 1993). For Cuba in particular, see David H. Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 34 (with ample references to earlier visions).

[2] Georges Balandier, Daily Life in the Kingdom of the Kongo (New York: Allen and Unwin, 1968 [French Version, Paris, 1965]) and James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441–1770 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

[3] Ann Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), for the role of the Capuchins in discovering problems with Kongo's Christianity. John Thornton, ‘The Kingdom of Kongo and the Counter-Reformation’, Social Sciences and Missions 26 (2013): 40–58 contextualizes their role and their problems with Kongo's Christianity.

[4] Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa, 1450–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994); this position is often implicit in the many histories written by clerical historians such as Jean Cuvelier, Louis Jadin, François Bontinck, Teobaldo Filesi, Carlo Toso and Graziano Saccardo, whose work has presented modern editions of the classical work of the Capuchin missionaries, commentaries and at times regional histories, such as Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia del missionari Capuccini, Vol. 3 (Venice: Curia Provinciale dei Cappuccini, 1982–1983). For both a position of dependence on missionaries and a recognition of local education, Louis Jadin, ‘Les survivances chrétiennes au Congo au XIXe siècle’, Études d'histoire africaine 1 (1970): 137–85.

[5] It is not mentioned at all in his seminal work, Thompson, Flash of the Spirit in the nearly 100-page section dealing with Kongo and its influence in Vodou, nor in Face of the Gods.

[6] Erwan Dianteill, ‘Kongo à Cuba: Transformations d'une religion africaine', Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religion 117 (2002): 59–80.

[7] Todd Ochoa, Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 8–10. Wyatt MacGaffey's work, especially Religion and Society in Central Africa: The BaKongo of Lower Zaire (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1986) is a favorite.

[8] Thiago Sapede, Muana Congo, Muana Nzambi a Mpungu: Poder e Catolicismo no reino do Congo pós-restauração (1769–1795) (São Paulo: Alameda, 2014) is the first book length study of Christianity in the later period of Kongo's history.

[9] John Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism in the Kingdom of Kongo', Journal of African History 54 (2013): 53–77.

[10] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism'.

[11] Sapede, Muana Congo, pp. 248–57.

[12] Thornton, ‘Afro-Christian Syncretism', for the details of the struggle, but a perspective that sees the Capuchin mission as central to Kongo Christianity, see Saccardo, Congo e Angola.

[13] John Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: D Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

[14] Rafael Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, Academia das Cienças de Lisboa, MS Vermelho 396, pp. 32–4, 183–5 (transcription by Arlindo Carreira, 2007 at http://www.arlindo-correia.com/161007.html) which marks the pagination of the original MS.

[15] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo', pp. 110–4.

[16] Raimondo da Dicomano, ‘Informazione' (1798), pp. 1–2. The text exists in both the Italian original and a Portuguese translation made at the same time. For an edition of both, see the transcription of Arlindo Carreira, 2010 (http://www.arlindo-correia.com/121208.html).

[17] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Teobaldo Filesi, ‘L'epilogo della ‘Missio Antiqua’ dei cappuccini nel regno de Congo (1800–1835)’, Euntes Docete 23 (1970), pp. 433–4.

[18] Among the first was Domingos Pereira da Silva Sardinha in 1854, who, according to King Henrique II of Kongo, had performed his duties of administering the sacraments with ‘all the necessary prudence', Henrique II to Vicar General of Angola, December 14, 1855, Boletim Oficial de Angola, 540 (1856).

[19] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon, Códice 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, October 27, 1856.

[20] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem ao Congo’, pp. 110–4.

[21] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7 (of manuscript).

[22] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 39, 69, 276.

[23] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagen', p. 217 (thanks to Thiago Sapede for this reference).

[24] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem’, pp. 32–4, 1835.

[25] For a thorough study of these religious artefacts and their meaning, see Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

[26] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 78.

[27] APF Congo 5, fols. 298–298v (Rosario dal Parco) ‘Informazione 1760' A French translation is found in Louis Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation du Congo, et rite d’élection des rois en 1775, d'après le P. Cherubino da Savona, missionaire de 1759 à 1774', Bulletin de l'Institut Historique Belge de Rome 35 (1963): 347–419 (marking foliation of original MS).

[28] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[29] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 53.

[30] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[31] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[32] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 196.

[33] Bernard Clist et alia, ‘The Elusive Archeology of Kongo Urbanism, the Case of Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi (Lower Congo, DRC)’, African Archaeological Review 32 (2014) 369–412 and Charlotte Verhaeghe, ‘Funeraire rituelen en het Kongo Konigrijk: De betekenis van de schelp- en glaskralen en de begraafplaats van Kindoki, Mbanza Nsundi, Neder-Kongo' (MA thesis, University of Ghent, 2014), pp. 44–50.

[34] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[35] ‘O Congo em 1845: Roteiro da viagem ao Reino de Congo por Major A. J. Castro … ’, Boletim de Sociedade de Geographia de Lisboa II series, 2 (1880), pp. 53–67. The orthographic irregularity reflects the actual pronunciation of these terms in the São Salvador region (the Sansala dialect).

[36] Alfredo de Sarmento, Os sertões d'Africa (Apontamentos do viagem) (Lisbon: Artur da Silva, 1880), p. 49 and Adolf Bastian, Ein Besuch in San Salvador: Der Hauptstadt des Königreichs Congo (Bremen: Heinrich Strack, 1859), pp. 61–2.

[37] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 102–3 and da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[38] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', p. 137.

[39] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 180–4.

[40] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[41] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 32–4; da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7; Zanobio Maria da Firenze, ‘Relazione della Stato in cui si trovassi autalmente il Regno di Congo … 1814’, July 10, 1816, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 420–1.

[42] Archivio ‘De Propaganda Fide' (Rome) Acta 1758, ff 213–9, no. 16, Relazione di Rosario dal Parco, July 31, 1758. These large numbers were not simply priests catching up on people who had not been baptized for a long time, as personnel staffing and statistics are found from 1752 onward; but the priests did not cover the whole country every year, so many priests would baptize babies all under age two or three.

[43] Castello de Vide, ‘Viagem', pp. 63–4; see also 87 for another noble as Captain of Church; 136 crowds at Mapinda.

[44] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', pp. 1–7.

[45] da Firenze, ‘Relazione', pp. 420–1.

[46] ‘Il Stato in cui si trova il Regno di Congo', September 22, 1820, in Filesi, ‘Epilogo’, pp. 433–4.

[47] Francisco das Necessidades, Report, March 15, 1845, in Arquivo do Archibispado de Angola, Correspondência de Congo, 1845–1892, cited in François Bontinck, ‘Notes complimentaire sur Dom Nicolau Agua Rosada e Sardonia’, African Historical Studies 2 (1969): 105, n. 6. Unfortunately, no researchers have been allowed to work in this section of the archive for many years and so the actual text is not available.

[48] Report of November 13, 1856 in António Brásio, ‘Monumenta Missionalia Africana’, Portugal em Africa 50 (1952), pp. 114–7.

[49] Biblioteca d'Ajuda, Lisbon 54/XIII/32 n° 9, Francisco de Salles Gusmão to the King, de Outubro de 27, 1856.

[50] Da Cruz, entry of October 8 and 25 on the problems of baptizing people.

[51] da Dicomano, ‘Informazione', is the first to describe this process; for more detail see Bastian, Besuch.

[52] David Eltis, An Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

[53] For a recent discussion of names and nomenclature, see Jésus Guanche, Africanía y etnicidad en Cuba (los componentes étnicos africanos y sus múltiples demoninaciones (Havana: Editoria de Ciencias Sociales, 2008). As we shall see, a number of other subdivisions also derived from the kingdom like the Musolongos, Batas and others.

[54] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Formation of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), for Cuba in particular, Matt Childs, ‘Recreating African Identities in Cuba', in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Era of the Slave Trade, eds. Jorge Cañizares-Esquerra, Matt Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), pp. 85–100.

[55] Robert Jameson, Letters from Havana in the Year 1820 … (London: John Miller, 1821), pp. 20–2 (from letter II).

[56] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Brujos (Havana: Liberia de F. Fé, 1906), pp. 81–5; and further developed in ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Editoriales Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), pp. 12–34; for a more recent statement based on more research, Matt Childs, The 1812 Aponte Rebellion and the Struggle Against Atlantic Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 209–45 and María del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Andrés Rodríguez Reyes, and Milagros Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo de “nación” a la casa de santo (Havana: Fundación Fernando Ortiz, 2012).

[57] For example, the now famous community of Pindar del Rio, see Natalia Bolívar Arostegui, Ta Makuende Yaya y las Reglas de Palo Monte: Mayombe, brillumba, kimbisa, shamalongo (Havana: Ediciones UNION, 1998).

[58] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, pp. 209–12; Jane Landers, ‘Catholic Conspirators: Religious Rebels in Nineteenth Century Cuba', Slavery and Abolition 36 (2015): 495–520.

[59] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 62–112; María del Carmen Barcia, Los ilustres apellidos: Negros en la Habana colonial (Havana: Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, 2008), pp. 45–151; Barcia, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del Cabildo which carefully demolishes the earlier theses of Fernando Ortiz and others that the cabildos grew out of the brotherhoods.

[60] This group must have split or been replaced by another, for a property dispute in the Congos Loangos relates to their foundation in 1776, Archivo Nacional de Cuba (ANC) Escribanía Valerio-Ramirez (VR) legajo 698, no. 10.205.

[61] Barcia, Iustres Apellidos, pp. 45–151.

[62] Barcia, Ilustres Apellidos.

[63] del Carmen Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Niebla Delgado, Del cabildo, pp. 12–9.

[64] Fernando Ortiz, ‘Los Cabildos Afrocubanos', in Ensayos Etnograficos, eds. Miguel Barnet and Angel Fernández (Havana: Ediciones Ciencas Sociales, 1984 [originally published 1921]), p. 13, citing documents in El Curioso Americano, 1899, p. 73.

[65] Proclama que en un cabildo de negros congos de la ciudad de La Habana, prononció por su Presidente Rey Siliman Mofundi Siliman … (Havana: np, 1808); for the claim of superiority, drawn from an ambiguous statement that he was ‘more black that you others’, see Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 25–7 and 311, footnotes 4 and 6. For political context, see Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 247–9.

[66] Fredrika Bremer, Hemmen i den Nya Världen, 2nd ed., Vol. 3 (Stockholm: Tidens forläg, 1854), p. 142 (English translation as The Homes of the New World: Impressions of America, Vol. 2 (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1853), p. 322) Her host's name is given in the original and obscured in the translation as ‘C—'.

[67] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 146–8 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 325–8).

[68] Henri Dumont, Antropologia y patologia comparadas de los Negros escalvos, 1876, trans. Israel Castellanos (Havana: Molina, 1922), p. 38.

[69] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 172–4 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 348–9).

[70] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[71] Esteban Pichardo, Diccionario provincial de voces Cubanas (Matanzas: Imprenta de la Real Marina, 1836), p. 72. Musundi may refer to Kongo's northern province of Nsundi, though the match is not exact since the nasal ‘n' is not incorporated into it, musundi might also mean ‘excellent', as the Virgin Mary was called ‘Musundi Madia' in the Kongo catechism meaning exactly this.

[72] It is possible that Bremer attended the dance of another Cabildo of Congos Reales, who were in the process of declaring their insolvency in 1851, ANC Escrabanía Joaquin Trujillo (JT) leg 84, no. 12, 1851; for a 1867 dispute, see the property case involving them in ANC VR leg. 393, no. 5875; other mentions of cabildos of this name including the group from 1865–1871 in Carmen Barcia, Ilustres apellidos, p. 408. For the 1880s mentions, see Archivio Historico de la Provincia de Matanzas (henceforward AHPM), Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882; no. 65, January 9, 1898 and no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[73] Fondo Fernando Ortiz, Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, 5.

[74] ANC Escibanía d'Daumas (ED) leg 917, no. 6. (foliation uncertain, very deteriorated document).

[75] António de Oliveira de Cadornega, História das guerras angolanas (1680–81 ), eds. Matias de Delgado and da Cunha, Vol. 3 (Lisbon: Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1940–1942, reprinted 1972), p. 3, 193. In July 2011, I drove through all three dialect zones, confirmed some of the differences by hearing them spoken and by speaking with people about these differences. My thanks to Father Gabriele Bortolami, OFMCap for driving, interacting with people, impromptu language updates and occasional lessons in the etiquette of dialect use in northern Angola.

[76] Cherubino da Savona, ‘Breve ragguaglio del Congo … ’, fols. 41v–44v, published with original foliation marked in Carlo Toso, ed., ‘Relazioni inedite di P. Cherubino Cassinis da Savona sul ‘Regno del Congo e sue Missioni’, L'Italia Francescana 45 (1974): 135–214. The foliation of the original is also marked in the French translation, found in Jadin, ‘Aperçu de la situation au Congo … '

[77] ANC ED, leg 494, no. 1, fols 96–97. This text was included in papers dealing with another dispute in 1827–1828 and in 1832–1836.

[78] ANC ED, leg 548, no. 11, fol. 9–9v; José Pacheco, January 21, 1806; ANC ED, leg. 660, no. 8, fols. 1–4; Pedro José Santa Cruz (a request for its own capataz) 1806; for the later dispute ANC ED leg 494, no. 1.

[79] ANC ED, leg 660, no. 8, fol. 4.

[80] ANC JT, leg. 84, no. 13 passim, 1851.

[81] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 30, July 7, 1882.

[82] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 65, January 9, 1898.

[83] AHPM, Religiones Africanas, leg 1, no. 31, July 31, 1886.

[84] Brown, Santería Enthroned, pp. 55–61 and Barcia Zequeira, Rodríguez Reyes, and Delgado, Cabildo de nación.

[85] Childs, Aponte Rebellion, p. 112 and ‘Identity', p. 91.

[86] Consider the temporal range of inquisition cases cited in Tania Chappi, Demonios en La Habana: Episodios de la Inquisición en Cuba (Havana: Oficinia del Hisoriador de la Ciudad, 2001). For an example of the sort of persecution the Inquisition could do, and the sort of information that can be obtained from their records, see James Sweet's study of slave religious life in Brazil, Recreating Africa.

[87] Jameson, Letters, pp. 20–2.

[88] See the transcript of his interview published in Henry Lovejoy, ‘Old Oyo Influences on the Transformation of Lucumí Identity in Colonial Cuba' (PhD diss., UCLA, 2012), pp. 230–46.

[89] Aisha Finch, Rethinking Slave Rebellion in Cuba: La Escalera and the Insurgencies of 1841–44 (Chapel Hill: North Carolina Press, 2015), pp. 199–220. Finch attributes most of the activities in these cases to the non-Christian part of Kongo religion, or an early form of Palo Mayombe; see also Miguel Sabater, ‘La conspiración de La Escalera: Otra vuelta de la tuerca', Boletín del Archivo Nacional 12 (2000): 23–33 (with quotations from trial records).

[90] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, p. 213 (Homes Vol. 2, p. 383).

[91] Bremer, Hemmen, Vol. 3, pp. 211–3 (Homes Vol. 2, pp. 379–83).

[92] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 26, citing late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sources.

[93] Abiel Abbott, Letters Written in the Interior of Cuba … (Boston, MA: Bowles and Dearborn, 1829), pp. 15–7.

[94] Cabrera did not employ any orthography of contemporary Kikongo in her day, but it is not at all difficult to recognize her ear for that language, which she did not speak, and most quotations she provided are readily intelligible.

[95] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5. This list, written in a different hand than Ortiz’, one that was shakier with large letters, on fragile aged paper (perhaps school paper) was, I believe, compiled by a literate person who was a native speaker of the language, based on his use of Kikongo grammatical forms (use of verb conjugations and class concords in particular).

[96] Armin Schwegler, ‘On the (Sensational) Survival of Kikongo in Twentieth Century Cuba', Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 15 (2000): 159–65; Jesús Fuentes Guerra, La Regla de Palo Monte: Un acercamiento a la Bantuidad Cubana (Havana: Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2012) (neither Schwegler nor Fuentes Guerra had access to Puyo's vocabulary in Ortiz’ documentation, the contention of its identity with Kikongo is my own). It seems likely that both Cabrera's and Ortiz’ vocabularies were collected probably from old native speakers, who entered Cuba at the end of the slave trade.

[97] For example, the class marker ki in the southern dialect is –ci in the north; use of ‘l' versus ‘d' would be another difference. The northern dialect is well attested in dictionaries of the French mission to Loango and Kakongo in the 1770s, compared with seventeenth- and nineteenth-century dictionaries of the southern dialects. I have also heard these differences myself in Angola.

[98] Fernando Ortiz, Hampa Afro-Cubana. Los Negros Esclavos (Havana: Bimestre Habana, 1916), pp. 25, 32 (clearly, testimony from the same informant).

[99] Ortiz, Negros Esclavos, p. 34. The term ‘Totila', clearly derived from the Kikongo ntotela meaning ‘king'. The word is first attested in the Kikongo dictionary of 1648, as meaning ‘King'. In 1901, King Pedro VI of Kongo, writing in Kikongo, styled himself ‘Ntinu Ntotela NeKongo' Archives of the Baptist Missionary Society (Regents’ Park College, Oxford) A 124 (both ntinu and ntotela can be glossed as ‘king').

[100] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 15.

[101] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 109. Cabrera, for her part, then told him of Nzinga a Nkuwu's baptism in 1491, presumably from one of the historical accounts she had read.

[102] On the assertions of Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita, see Thornton, Kongolese Saint Anthony; on the representation of Christ as an Kongolese, Fromont, Art of Conversion.

[103] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 93.

[104] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 58.

[105] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 59.

[106] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 14.

[107] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 19.

[108] The problem was apparent to Lydia Cabrera in her study of Palo, El Regla de Congo: Palo Monte Mayombe (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1979), pp. 120–30, as one can see from the defensive tone of her informants, probably speaking with her post-1960 experience (this is not seen as a problem in her earlier publication, El Monte (Havana, 1954)).

[109] Cabrera, Vocabulario, p. 123.

[110] Cabrera, Monte, pp. 119–23 passim (here, often used in the context of witchcraft); Reglas de Congo, pp. 24–5. In W. Holman Bentley, Dictionary and Grammar of the Kongo Language (London: Kegan Paul, 1887), p. 361, which relates to the Kinsansala dialect (the most likely associated with Christianity) in the 1880s, mvumbi meant simply the corpse of a dead person; in the 1648 dictionary ‘spirits' was rendered as ‘mioio mia mvumbi' (or souls of corpses).

[111] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. In Kikongo, mvumbi means a corpse, the lifeless remains of a dead person, and the name of an ancestor would usually have been nkulu, though this usage would still make sense in Kikongo.

[112] See John Thornton, ‘Central African Names and African American Naming Patterns', William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd Series, 50 (1993): 727–42.

[113] The denunciation of the first tooth ceremony is only attested in the general complaints of the Capuchins in the 1650s, written by Serafino da Cortona.

[114] ‘Kisi malongo' appears to be ‘nkisi malongo'. A more likely way to say ‘the teaching of nkisi' would be ‘malongo ma nkisi', so the word order puzzles me. However, word order in Kikongo is flexible and should the speaker wish to emphasize the teaching spiritual part, it might be feasible to use this order.

[115] Cabrera, Reglas de Congo, p. 24. My translation of the phrase ‘nganga la musi' assumes that the speaker has only partial command of Kikongo grammar and would be ‘nganga a mu nsi' The same informant used the term kisi malongo, and perhaps as a Cuban-born person was not secure in the language.

[116] Cabrera, Regla de Congo, p. 23.

[117] Institute de Linguistica y Literatura, Havana, Fondo Fernando Ortiz, 5.

#The Kingdom of Kongo and Palo Mayombe: Reflections on an African-American Religion#Palo Mayombe#ATR#African Traditional Religions#Kongo#Reglas De congo#Nkisi#Kikongo

1 note

·

View note

Note

As someone who is half Haitian on my father’s side, how would I go about incorporating more of the culture into my daily spiritual practice? Do I have to be explicitly invited to build a relationship with the lwa? I’ve been thinking of starting an ancestor altar and would love to know where to start

Hi,

You are Haitian, so Vodou is your birthright. You don't need permission or invitation, all the invitation necessary happened a long, long time ago.

If you don't have any family who practice (which is not unusual), I would suggest getting a reading from a houngan or manbo who can give you an overview of what's there and areas you may want to tend to, as well as give guidance on how you move forward with your lwa.

An ancestor altar is always a great start for any spiritual practice, and you can keep it super simple to start. Set out a white candle (I like glass novena candles because they can burn for awhile), clean water in a glass or cup, and speak to them. If you know family names, you can call out to them as 'ancestors of the Last Name family', and you can call for deceased ancestors by name, if you know individual names. If you know where your family is from in Haiti, you can call them collectively by 'bityason Place Name' (pronounced bee-tas-yon).

Happy to link up with you for a reading if that would be helpful; feel free to reach out!

Hope this helps...welcome back home.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

also i'm curious, are you into ATR?

I joined Espiritismo which isn't really closed. But that was recent. I didn't set up an altar until like 2022. I am into ATRs and I've had several Vodou readings.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some Pictures I Took From Fet Gede.

I enjoyed this years Fet Gede. This Sosyete not only celebrates the spirits here in the city. But respects and honors others Day of the Dead traditions also.

Fet Gede in Haiti is just such a past-honoring event. Known as the Festival of the Ancestors, Fet Gede ( = The Sacred Dead) is the Vodou equivalent of Mardi Gras, the Mexican Day of the Dead, and Halloween, all in one. So everyone dresses up.

But here are some pics I took while I was there. Check back for the video.

Spirit Statue. Gede Statue

Baron Altar. Baron La Croix

Some kind of death mermaid statue.

It's cool.

One of the children of the spirits dancers in the Oufo. Dressed as a spirit of the Dead. Gede.

🖕Me and Ghanaian Priest & Master Drummer Osofo Andrew.

🖕 Me & Mambo Sally.

Taja Nicholle is a Afro-Indigenous Certified Death Doula/Grief Support Counselor. She's does death healing, cleansings readings, Sound Healing, etc.

https://www.therisingroseco.com/

I meet these women and though there costumes were cool.

🖕 the top is of a Haitian Oungan he and Andrew and some others released the Gede spirits after the Fet Gede was over. We told them thank you and then we all sayed a prayer.

This is the Haitian Oungan with the white powder on his face he was dancing and smoking cigarettes the spirits came and jumped a few people that night.

#like and/or reblog!#google search#follow my blog#ask me anything#haitian vodou priest#haitian vodou#Fet Gede#voodoo priestess#Voodoo altar#dia de muertos#catrina#Baron La Croix#new orleans voodoo#Blessing.#new post

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAITRE CARREFOUR

Carrefour, Maitre – Master of the Crossroads Maitre Carrefour, master and guardian of the crossroads, may be the alter ego of Eshu Elegbara, his mirror image, shadow side, or nocturnal counterpart. Eshu Elegbara (Leg ba; Elegba) is a solar spirit. Maitre Carrefour emerges with the moon. Papa Legba is a trickster: Maitre Carrefour is a trickster taken to exponential extremes. Crossroads are places of decisions; the road chosen (or not) can impact one’s entire life. Be careful: crossroads spirits are invoked to point you to the right road or direction. If Maitre Carrefour is feeling tricky, he may point you in the wrong direction or make you lose your way. Crossroads are favourite haunts of witches, spirits, and ghosts: those magical crossroads are under Maitre Carrefour’s jurisdiction. Maitre Carrefour walks the crossroads at night, in the company of malevolent spirits. He is their master and gatekeeper. Maitre Carrefour controls comings and goings of ghosts and malevolent spirits. Carrefour unleashes the secret spirits of the night: he may be petitioned to keep them far from you. He is, however, usually a spirit of last resort. Don’t invoke him until other avenues and attempts have failed. He is a great, powerful, and potentially dangerous spirit: never summon him for trifles. Don’t get too comfortable or familiar with him. He is the master. It is not necessarily to your benefit to attract his attention without very good reason. If you feel you need him, it may be advisable to request the services of a reputable Vodou priest or priestess (houngan; mambo) to intercede for you. Maitre Carrefour is an aggressive, effective spirit. He works quickly, and so devotees love him. There are no Demons that he cannot command. However, he also punishes quickly: he’s not a good-natured, patient spirit. Never promise him what you’re not absolutely certain you can deliver immediately. Maitre Carrefour is not a spirit for beginners. He doesn’t care whether you’re just learning. Pleas for mercy may have little effect. He has a cold nature; hence he can behave cruelly although he does possess a sense of justice. He is not an evil spirit per se but a hardened, tough one. He didn’t get to be master of evil spirits by being nice. He is a brilliant, quick-thinking, tricky spirit: don’t even think of outwitting him. Maitre Carrefour is petitioned to keep malignant spirits, ghosts, and people far from you. He can break hexes, curses, and spells. If sorcerers have set ghosts or spirits after you, Maitre Carrefour can redirect them and prevent them from drawing near. Maitre Carrefour owns the night: there’s little he can’t do. • Maitre Carrefour is the Bizango counterpart to Legba, the first invoked in rituals and ceremonies. • He is syncretized to Saint Andrew, the vampire saint. • Carrefour is sometimes classified among the Barons, in which context he is Baron Carrefour (French) or Bawon Kalfou (Kreyol).

ALSO KNOWN AS:

Kalfu; Mèt Kalfou

ORIGIN:

Haiti

CLASSIFICATION:

Lwa

ANIMAL:

Black pig

COLOUR:

Black

NUMBERS:

3, 7

TIME:

Night

PLANET:

Carrefour is the sun at midnight and the moon to Legba’s noonday sun.

ALTARS:

Maitre Carrefour typically has his own altars, not shared with other spirits.

OFFERINGS:

Rum set ablaze (be careful!); cigars; lace his food generously with hot sauce, cayenne, or habanero powder

4 notes

·

View notes