#Virginia health care clinic

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Glow Like Never Before: Discover Top-Rated Skin Hydration Clinics in Warrenton, VA

Hey there, skin care enthusiasts! If you’ve been battling dry, flaky, or dull skin, you’re not alone. Skin hydration is crucial for a glowing complexion, but finding the right solution can be a bit overwhelming. Luckily, Warrenton, VA, has some fantastic clinics that specialize in skin hydration treatments, including the trendy IV therapy. Let’s dive into what makes these clinics stand out and how they can help you achieve that radiant, hydrated glow.

Understanding Skin Hydration

✦What is Skin Hydration?

Skin hydration is all about keeping your skin well-moisturized from the inside out. It’s like giving your skin a big drink of water! When your skin is properly hydrated, it’s plump, smooth, and has a youthful glow. Hydration helps maintain your skin’s elasticity, reduces the appearance of fine lines, and can even improve your overall skin texture.

✦Common Signs of Dehydrated Skin

If your skin feels tight, looks dull, or is showing flakes and dry patches, it might be time to address hydration. Dehydrated skin can be caused by various factors like environmental conditions, diet, and lifestyle choices. But don’t worry – there are effective treatments available to help restore that healthy glow.

The Role of IV Therapy in Skin Hydration

✦What is IV Therapy?

IV (intravenous) hydration therapy is a treatment where fluids and nutrients are delivered directly into your bloodstream through an IV drip. It’s a quick and effective way to hydrate your body and skin. IV therapy can boost your hydration levels faster than drinking water alone because the fluids go straight to where they’re needed most.

✦Benefits of IV Therapy for Skin Hydration

One of the biggest benefits of IV therapy is its immediate effect. You’ll notice a difference in your skin’s hydration and overall appearance right after your session. It’s not just about hydration – IV therapy can also improve skin elasticity, reduce signs of aging, and give your skin a vibrant, healthy glow.

What to Expect During an IV Therapy Session

During an IV therapy session, you’ll be comfortably seated while a healthcare professional inserts a small needle into your vein. The procedure is generally quick, and you can relax or read a book while the nutrients are administered. Afterward, there might be some mild soreness, but it’s usually nothing to worry about.

Top-Rated Skin Hydration Clinics in Warrenton, VA

Discover Top Skin Hydration Clinics in Warrenton: Consult and Get the Glow You've Been Dreaming Of!

✦Clinic 1: Lifestyle's MedSpa

Overview: Lifestyle's MedSpa is renowned in Warrenton for its top-notch skin hydration treatments.

Services Offered: They offer a range of services, including IV hydration therapy, customized facials, and hydrating facial masks.

Unique Features: Lifestyle's MedSpa uses advanced technology and high-quality products. Their staff is highly trained, and they’re known for their personalized approach to skin care.

Location and Contact Information: Lifestyle's MedSpa | 400 Holiday ct, Warrenton, VA | (540) 680-2426

✦Clinic 2: Lifestyle Physicians

Overview: Lifestyle Physicians is a favorite for those seeking both relaxation and effective hydration treatments.

Services Offered: From IV therapy to deep hydration facials, they have a variety of treatments tailored to your skin’s needs.

Unique Features: Their soothing environment and expert staff make your visit enjoyable and effective. Plus, they often have special offers on their hydration packages.

Location and Contact Information: Lifestyle Physicians | Holiday Ct, Suite 102, Warrenton, VA | (540) 680-2426

How to Choose the Right Clinic for Your Needs

✦Factors to Consider

When picking a clinic, make sure to check their credentials and read reviews from other clients. Look for a clinic with experienced professionals who use up-to-date technology. It’s also a good idea to visit in person if possible, to get a feel for the atmosphere and customer service.

✦Questions to Ask

Don’t hesitate to ask about the procedures, costs, and safety measures. Understanding what to expect and how the treatment will benefit you is key to making an informed decision.

✦Making an Informed Decision

Choose a clinic that aligns with your skin care needs and preferences. Remember, hydration is a personal journey, and finding the right place can make all the difference in achieving that glowing, hydrated skin you’re after.

Tips for Maintaining Skin Hydration at Home

✦Daily Skincare Routine

Incorporate products that enhance hydration, like moisturizers with hyaluronic acid and hydrating serums. Consistency is key to maintaining healthy skin.

✦Lifestyle Changes

Drink plenty of water, eat a balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables, and avoid excessive sun exposure. These habits support overall skin health and hydration.

✦Regular Check-Ins

While home care is essential, don’t skip regular professional treatments. Schedule follow-ups with your chosen clinic to keep your skin in top shape.

Conclusion

Addressing skin hydration is crucial for a vibrant, youthful appearance. Warrenton’s top-rated clinics offer fantastic solutions, from IV therapy to comprehensive skin care treatments. Don’t wait – explore these clinics, schedule a consultation, and take the first step toward glowing, hydrated skin today!

Feel free to reach out to these clinics or follow our Blog for more tips on choosing the best skin hydration treatment. Cheers to healthier, more radiant skin!

#skin hydration treatment#skin hydration therapy#Skin care treatment#skin hydration therapy in warrenton#iv therapy#iv therapy benefits#iv mobile therapy#lifestyle medspa#Virginia health care clinic

0 notes

Text

Get Digital x-ray Services near me in Chesapeake VA at Acorn Care

Acorn Care is one of the most renowned digital x-ray clinics near me in Chesapeake, VA. We are providing all types of x-rays for your families health and wellness with same day reporting.

#x-ray near me#chesapeake xray#X-ray#walk in x ray near me#same day xray near me#digital xray#digital xray clinic near me#xray services#urgent care with x ray near me#x ray in Chesapeake VA#chesapeake#virginia#health#healthcare

0 notes

Text

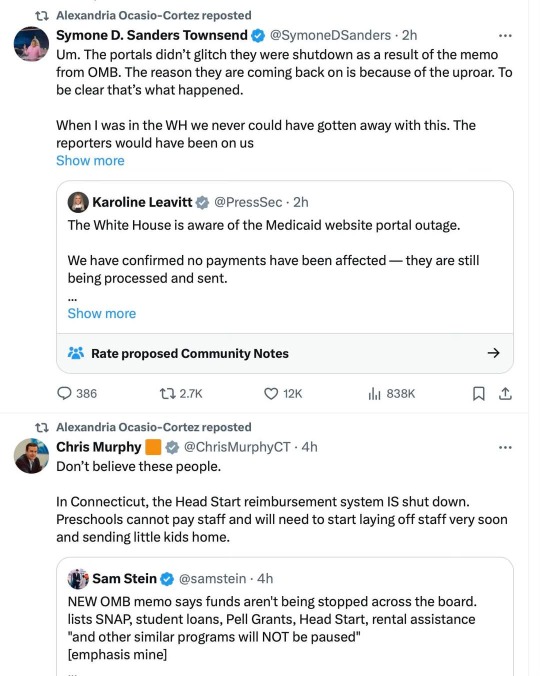

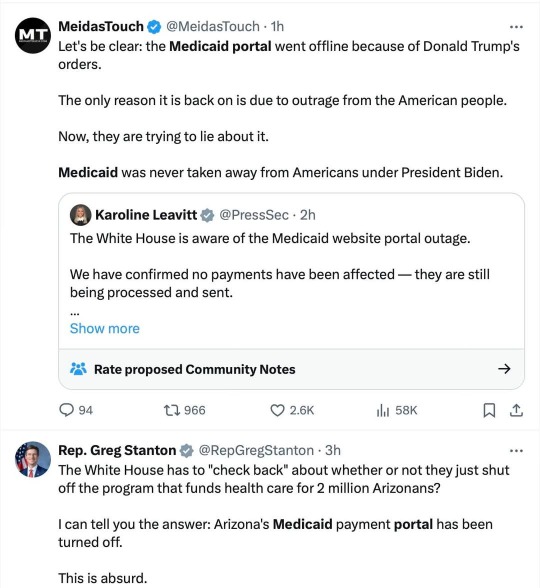

From Rebecca Solnit:

Yes, they want to steal your healthcare and rights and the rest for good, and they stole a lot of people's healthcare for the day. Also the White House press secretary seems to be lying about that. Don't buy the lies. Striking to see redder as well as bluer-state politicians in these tweets. And yeah, the attack is on hold BECAUSE of the huge pushback, but of course they're pretending they never intended this huge overreach.

It gets worse below the cut...

Martin Heinrich

@SenatorHeinrich

·

4h

Now Trump is blocking New Mexico's access to the Medicaid portal!

This won't just hurt the 714,422 New Mexicans on Medicaid. It threatens to shutdown our entire health care system.

I'm calling on Trump to undo this chaos IMMEDIATELY.

Rep. Nadler

@RepJerryNadler

·

1h

Make no mistake, this happened because Donald Trump ordered it to happen.

Many states still face Medicaid portal outages, and his reckless order continues to freeze critical services like food aid, cancer research, and FEMA relief—lifelines for Americans in every zip code.

Senator Beth Liston

@Liston4Ohio

·

1h

The Medicaid payment portal is currently frozen. Our healthcare system relies on these funds for over 3.5 million people. Hospitals, doctors, dentists - all providers are not getting paid. Ohio loses ~$73,000/minute if the federal government does not release the payments they owe

Rep. Terri A. Sewell

@RepTerriSewell

·

2h

My office has received reports that Alabama’s Medicaid portal is shut down.

More than 1 million Alabamians rely on Medicaid along with the providers, hospitals, & clinics that serve them.

The Trump Administration needs to restore it NOW!

Aaron Fritschner

@Fritschner

·

1h

Virginia civil servants are being placed on leave or fired, businesses and non-profits that rely on grants are preparing to close or lay off workers, the Medicaid portal is down, hospital funding is frozen, and all the Governor can muster is this blame-shifting twaddle? PATHETIC

Quote

Brandon Jarvis

@Jaaavis

·

2h

Youngkin’s statement on pause of federal grants

Image

Senator Chris Coons

@ChrisCoons

·

1h

Delaware's Medicaid payment portal was turned off, just like dozens of other states.

One in five Delawareans and nearly 80 million Americans are on Medicaid.

I don't know if this is cruelty or incompetence. I do know Trump is playing with people’s lives.

#rebecca solnit#us politics#dumpster fire usa#the week america was stripped for parts#christofascists#medicaid#us healthcare#us health system#we need luigis everywhere#antifascist

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Saturday, an Associated Press investigation revealed that OpenAI's Whisper transcription tool creates fabricated text in medical and business settings despite warnings against such use. The AP interviewed more than 12 software engineers, developers, and researchers who found the model regularly invents text that speakers never said, a phenomenon often called a “confabulation” or “hallucination” in the AI field.

Upon its release in 2022, OpenAI claimed that Whisper approached “human level robustness” in audio transcription accuracy. However, a University of Michigan researcher told the AP that Whisper created false text in 80 percent of public meeting transcripts examined. Another developer, unnamed in the AP report, claimed to have found invented content in almost all of his 26,000 test transcriptions.

The fabrications pose particular risks in health care settings. Despite OpenAI’s warnings against using Whisper for “high-risk domains,” over 30,000 medical workers now use Whisper-based tools to transcribe patient visits, according to the AP report. The Mankato Clinic in Minnesota and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles are among 40 health systems using a Whisper-powered AI copilot service from medical tech company Nabla that is fine-tuned on medical terminology.

Nabla acknowledges that Whisper can confabulate, but it also reportedly erases original audio recordings “for data safety reasons.” This could cause additional issues, since doctors cannot verify accuracy against the source material. And deaf patients may be highly impacted by mistaken transcripts since they would have no way to know if medical transcript audio is accurate or not.

The potential problems with Whisper extend beyond health care. Researchers from Cornell University and the University of Virginia studied thousands of audio samples and found Whisper adding nonexistent violent content and racial commentary to neutral speech. They found that 1 percent of samples included “entire hallucinated phrases or sentences which did not exist in any form in the underlying audio” and that 38 percent of those included “explicit harms such as perpetuating violence, making up inaccurate associations, or implying false authority.”

In one case from the study cited by AP, when a speaker described “two other girls and one lady,” Whisper added fictional text specifying that they “were Black.” In another, the audio said, “He, the boy, was going to, I’m not sure exactly, take the umbrella.” Whisper transcribed it to, “He took a big piece of a cross, a teeny, small piece … I’m sure he didn’t have a terror knife so he killed a number of people.”

An OpenAI spokesperson told the AP that the company appreciates the researchers’ findings and that it actively studies how to reduce fabrications and incorporates feedback in updates to the model.

Why Whisper Confabulates

The key to Whisper’s unsuitability in high-risk domains comes from its propensity to sometimes confabulate, or plausibly make up, inaccurate outputs. The AP report says, "Researchers aren’t certain why Whisper and similar tools hallucinate," but that isn't true. We know exactly why Transformer-based AI models like Whisper behave this way.

Whisper is based on technology that is designed to predict the next most likely token (chunk of data) that should appear after a sequence of tokens provided by a user. In the case of ChatGPT, the input tokens come in the form of a text prompt. In the case of Whisper, the input is tokenized audio data.

The transcription output from Whisper is a prediction of what is most likely, not what is most accurate. Accuracy in Transformer-based outputs is typically proportional to the presence of relevant accurate data in the training dataset, but it is never guaranteed. If there is ever a case where there isn't enough contextual information in its neural network for Whisper to make an accurate prediction about how to transcribe a particular segment of audio, the model will fall back on what it “knows” about the relationships between sounds and words it has learned from its training data.

According to OpenAI in 2022, Whisper learned those statistical relationships from “680,000 hours of multilingual and multitask supervised data collected from the web.” But we now know a little more about the source. Given Whisper's well-known tendency to produce certain outputs like "thank you for watching," "like and subscribe," or "drop a comment in the section below" when provided silent or garbled inputs, it's likely that OpenAI trained Whisper on thousands of hours of captioned audio scraped from YouTube videos. (The researchers needed audio paired with existing captions to train the model.)

There's also a phenomenon called “overfitting” in AI models where information (in this case, text found in audio transcriptions) encountered more frequently in the training data is more likely to be reproduced in an output. In cases where Whisper encounters poor-quality audio in medical notes, the AI model will produce what its neural network predicts is the most likely output, even if it is incorrect. And the most likely output for any given YouTube video, since so many people say it, is “thanks for watching.”

In other cases, Whisper seems to draw on the context of the conversation to fill in what should come next, which can lead to problems because its training data could include racist commentary or inaccurate medical information. For example, if many examples of training data featured speakers saying the phrase “crimes by Black criminals,” when Whisper encounters a “crimes by [garbled audio] criminals” audio sample, it will be more likely to fill in the transcription with “Black."

In the original Whisper model card, OpenAI researchers wrote about this very phenomenon: "Because the models are trained in a weakly supervised manner using large-scale noisy data, the predictions may include texts that are not actually spoken in the audio input (i.e. hallucination). We hypothesize that this happens because, given their general knowledge of language, the models combine trying to predict the next word in audio with trying to transcribe the audio itself."

So in that sense, Whisper "knows" something about the content of what is being said and keeps track of the context of the conversation, which can lead to issues like the one where Whisper identified two women as being Black even though that information was not contained in the original audio. Theoretically, this erroneous scenario could be reduced by using a second AI model trained to pick out areas of confusing audio where the Whisper model is likely to confabulate and flag the transcript in that location, so a human could manually check those instances for accuracy later.

Clearly, OpenAI's advice not to use Whisper in high-risk domains, such as critical medical records, was a good one. But health care companies are constantly driven by a need to decrease costs by using seemingly "good enough" AI tools—as we've seen with Epic Systems using GPT-4 for medical records and UnitedHealth using a flawed AI model for insurance decisions. It's entirely possible that people are already suffering negative outcomes due to AI mistakes, and fixing them will likely involve some sort of regulation and certification of AI tools used in the medical field.

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greedflation, but for prisoners

I'm touring my new, nationally bestselling novel The Bezzle! Catch me TOMORROW (Apr 21) in TORINO, then Marin County (Apr 27), Winnipeg (May 2), Calgary (May 3), Vancouver (May 4), and beyond!

Today in "Capitalists Hate Capitalism" news: The Appeal has published the first-ever survey of national prison commissary prices, revealing just how badly the prison profiteer system gouges American's all-time, world-record-beating prison population:

https://theappeal.org/locked-in-priced-out-how-much-prison-commissary-prices/

Like every aspect of the prison contracting system, prison commissaries – the stores where prisoners are able to buy food, sundries, toiletries and other items – are dominated by private equity funds that have bought out all the smaller players. Private equity deals always involve gigantic amounts of debt (typically, the first thing PE companies do after acquiring a company is to borrow heavily against it and then pay themselves a hefty dividend).

The need to service this debt drives PE companies to cut quality, squeeze suppliers, and raise prices. That's why PE loves to buy up the kinds of businesses you must spend your money at: dialysis clinics, long-term care facilities, funeral homes, and prison services.

Prisoners, after all, are a literal captive market. Unlike capitalist ventures, which involve the risk that a customer will take their business elsewhere, prison commissary providers have the most airtight of monopolies over prisoners' shopping.

Not that prisoners have a lot of money to spend. The 13th Amendment specifically allows for the enslavement of convicted criminals, and so even though many prisoners are subject to forced labor, they aren't necessarily paid for it:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/02/captive-customers/#guillotine-watch

Six states ban paying prisoners anything. North Carolina caps prisoners' pay at one dollar per day. Nationally, prisoners earn $0.52/hour, while producing $11b/year in goods and services:

https://www.dollarsandsense.org/archives/2024/0324bowman.html

So there's a double cruelty to prison commissary price-gouging. Prisoners earn far less than any other kind of worker, and they pay vastly inflated prices for the necessities of life. There's also a triple cruelty: prisoners' families – deprived of an incarcerated breadwinner's earnings – are called upon to make up the difference for jacked up commissary prices out of their own strained finances.

So what does prison profiteering look like, in dollars and sense? Here's the first-of-its-kind database tracking the costs of food, hygiene items and religious items in 46 states:

https://theappeal.org/commissary-database/

Prisoners rely heavily on commissaries for food. Prisons serve spoiled, inedible food, and often there isn't enough to go around – prisoners who rely on the food provided by their institutions literally starve. This is worst in prisons where private equity funds have taken over the cafeteria, which is inevitable accompanied by swingeing cuts to food quality and portions:

https://theappeal.org/prison-food-virginia-fluvanna-correctional-center/

So you have one private equity fund starving prisoners, and another that's gouging them on food. Or sometimes it's the same company. Keefe Group, owned by HIG Capital, provides commissaries to prisons whose cafeterias are managed by other HIG Capital portfolio companies like Trinity Services Group. HIG also owns the prison health-care company Wellpath – so if they give you food poisoning, they get paid twice.

Wellpath delivers "grossly inadequate healthcare":

https://theappeal.org/massachusetts-prisons-wellpath-dentures-teeth/

And Trinity serves "meager portions of inedible food":

https://theappeal.org/clayton-county-jail-sheriff-election/

When prison commissaries gouge on food, no part of the inventory is spared, even the cheapest items. In Florida, a packet of ramen costs $1.06, 300% more inside the prison than it does at the Target down the street:

https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/24444312-fl_doc_combined_commissary_lists#document/p6/a2444049

America's prisoners aren't just hungry, they're also hot. The climate emergency is sending temperatures in America's largely un-air-conditioned prisons soaring to dangerous levels. Commissaries capitalize on this, too: an 8" fan costs $40 in Delaware's Sussex Correctional Institution. In Georgia, that fan goes for $32 (but prisoners are not paid for their labor in Georgia pens). And in scorching Texas, the commissary raised the price of water by 50% last summer:

https://www.tpr.org/criminal-justice/2023-07-20/texas-charges-prisoners-50-more-for-water-for-as-heat-wave-continues

Toiletries are also sold at prices that would make an airport gift-shop blush. Need denture adhesive? That's $12.28 in an Idaho pen, triple the retail price. 15% of America's prisoners are over 55. The Keefe Group – sister company to the "grossly inadequate" healthcare company Wellpath – operates that commissary. In Oregon, the commissary charges a 200% markup on hearing-aid batteries. Vermont charges a 500% markup on reading glasses. Imagine spending decades in prison: toothless, blind, and deaf.

Then there's the religious items. Bibles and Christmas cards are surprisingly reasonable, but a Qaran will run you $26 in Vermont, where a Bible is a mere $4.55. Kufi caps – which cost $3 or less in the free world – go for $12 in Indiana prisons. A Virginia prisoner needs to work for 8 hours to earn enough to buy a commissary Ramadan card (you can buy a Christmas card after three hours' labor).

Prison price-gougers are finally facing a comeuppance. California's new BASIC Act caps prison commissary markups at 35% (California commissaries used to charge 63-200% markups):

https://theappeal.org/price-gouging-in-california-prisons-newsom-signature/

Last year, Nevada banned any markup on hygiene items:

https://www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/82nd2023/Bill/10425/Overview

And prison tech monopolist Securus has been driven to the brink of bankruptcy, thanks to the activism of Worth Rises and its coalition partners:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/08/money-talks/

When someone tells you who they are, believe them the first time. Prisons show us how businesses would treat us if they could get away with it.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/04/20/captive-market/#locked-in

#pluralistic#carceral state#price gouging#greedflation#prisons#the bezzle#captive markets#capitalists hate capitalism#monopolies#the appeal#keefe group#hig capital#guillotine watch#wellpath#trinity services group#sussex correctional institute#cooked alive#air conditioning#climate change#idaho#oregon#freedom of religion#vermont#florida#kentucky#georgia#arkansas#wyoming#missouri#ramen

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today We Honor Dr.Josephine English

Dr. Josephine English was an American gynecologist who was the first black woman to open a private practice in New York. She was also known for her work in real estate and health care, in addition to her philanthropy towards the arts.

English was born on December 17, 1920 to Jennie English and Whittie Sr. in Ontario, Virginia. She moved to Englewood, New Jersey in 1939. Her family was one of the first black families in Englewood. She attended Hunter College for her bachelor’s degree until 1949, and earned her Master’s in Psychology at New York University. She initially wanted to become a psychiatrist, but ended up choosing gynecology after discovering her interest at Meharry Medical College where she earned her medical degree in gynecology.

Dr.Josephine English opened her practice at Harlem Hospital. Once in Brooklyn, she opened up a women’s health clinic in Bushwick in 1956, as well as another in Fort Greene two decades later. During her career, English helped deliver 6,000 babies, including the children of Malcolm X, Betty Shabazz, and Lynn Nottage.

English’s interest in health care lead her establish the Adelphi Medical Center and child care programs, such as Up the Ladder Day Care and After School Program. Her passion for theater led her to establish the Paul Robeson Theater from a dilapidated church. She helped actors create performances to educate the populace on health and nutrition.

CARTER™️ Magazine

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#drjoesphineenglish

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

write post about the tulpar crew working at like waffle house also you opinion on what brand of soap they use

Soap first:

Anya washes with dove bar soap first, cucumber cool moisture. Uses one of the Neutrogena liquid soaps like the brown rain bath. Unscented lotions or balms and a very light perfume, thinking something vanilla like or a shea butter. Over the counter cheap perfume that’s a bit to alcoholish but it suits her in a clinical way.

Curly is like high maintenance shower guy. Started because an ex put him onto it and now it's a routine. Special face soap and exfoliating hand brush, bodywash that is way too expensive but he feels dirty without it. Has like a lot of serums and a body oil lotion combo that he has that makes him smell really nice. All of it is uncommon and you need to go to a specific place to get them. Not excessive but he starts tweaking if he runs out of one mid routine.

Daisuke is just as bad as Curly. His bathroom looks like a bath and bodyworks display front. Has a bath bomb for the day, uses a like honey dew mask and soaks. Long as showers and has a teeth cleaning kit. He stare at 9 and isn’t done until 11. Cherry Blossom lotion you can smell him a miles away before you see his ass.

Jimmy uses either unscented dial or Irish springs. Maybe even like the aqua bars from dollar tree. No towel or luffa or anything just rubs his on his hands then washes with the lather. None descript deodorant, mixes with his smell in a weird way. Is the type to do it all at once in the shower, teeth, hair, nails. It’s like all jacked in a way. Shaves his razor blade rarely but thinks his shave is clean always.

Swansea uses like man scents. Sandalwood and driftwood soaps standard rag. Likes to stand in the water, cold shower guy surprisingly, his wife hates it, she never wants to shower with him. No cologne and uses like Old spice because it reminds him of his youth in a nostalgic way. Smells like old man naturally so he just smells like a freshly reupholstered chair and sweat.

Waffle House time:

Anya is the hostess super good at her job but has issues because the waiter is shit and the kitchen is run worse than dashcon. Has ignored a family to rearrange one stack of menues and trips on the grease stains a lot.

Daisuke is the waiter and bus boy and tends to talk and forget about his tables. Once sat and ate off a customers plate with them, whether they enjoyed the company or not doesn’t matter this is a Waffle House

Curly is the manager and is usually dealing with complaints and files in the office. Has had to facilitate more fights after Jimmy was hired but business has improved subsequently…

You’ll see him crying in a booth but he’s real good at acting normal for the customer. Sits with costumers to and it’s awkward cause he’s way too nice to be there.

Jimmy’s the supervisor and cook. He makes the shittiest food that only tastes good if ur coming in shitfaced at like 2 am. Hears a complaint and comes out grease pan in hand ready to “take criticism”

Swansea works there but what he does is between him and god. Sits in a booth playing solitaire and if you come and ask him for anything he mentions how I he did his time for this shift and he’s on an extended break. Treats the fights like a show and dinner.

They stay open even if they actually reach Waffle House’s huricxan threshold

If Curly or Swansea come in to break up a fight everyone scatters like rats

They all chain smoke and hide it from each other. Only Curly really cares because someone (Jimmy) is smoking in the kitchen. Yes he’s blowing it onto the food.

The crash was Jimmy putting ice in the air fryer and it did hurt Curly but like he’s regularly fine they just put him in the office cause there’s still the hurricane outside

I feel like they are in like West Virginia idk just seems isolated enough. I like the idea this could only happen if they are all southern

The restaurant is infested with many things but the health inspectors can’t rip the B rating off so they just say fuck it

Combined with the soap I think the safest thing to eat at the Waffle House is like ice from the bin but by the time it gets to ur table it likely has like mold spores on it.

#mouthwashing#ask#catstew#I think Jimmy can cook better but he’s being on brand#he’s taken a customers plate and ate it himself#I’m not taggin everyone

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The lack of clarity means that health care providers — those working at abortion clinics and hospital-affiliated specialists who treat high-risk pregnancies — are often defaulting to the most conservative interpretation. With something like Trisomy 18, for example, multiple physicians told The 19th that because there is a small chance a baby will live, even for a little bit of time, they don’t believe that would be enough to qualify for an exception.

#links#I hate it so much and this woman deserved better#abortion tw#politics#vote Yes on 4#please please please

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greg Owen at LGBTQ Nation:

Hospitals in Colorado, Virginia, and Washington D.C. said Thursday they have stopped providing healthcare for young transgender people. The actions follow President Donald Trump’s executive order calling for a ban on gender-related care for anyone under 19 years old, which it described as “chemical or surgical mutilation.” Denver Health in Colorado has stopped providing gender-related surgeries for people under age 19, a spokesperson told the Associated Press on Thursday. It was unclear whether the hospital will continue providing hormone therapy and puberty blockers to young people, as Trump’s executive order targeted both for possible persecution. In Virginia, the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Health and Children’s Hospital of Richmond said medication and surgical procedures for trans youth have been “suspended.” In Washington D.C., Children’s National Hospital said it had “paused prescriptions of puberty blockers and hormone therapy to comply with the directives while we assess the situation further.” Children’s National does not provide gender-related surgery for minors, a spokesperson said. Trump’s order, signed Tuesday, directs agencies to review hospitals receiving federal research and education grants and halt funding for those not in compliance with the order. Other hospitals said they would continue providing care under threat from the Trump administration. “Our team will continue to advocate for access to medically necessary care, grounded in science and compassion for the patient-families we are so privileged to serve,” a statement from Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago said. They added current practices would continue while hospital officials review the order and assess “any potential impact to the clinical services we offer to our patient families.”

At least a few hospitals in states where gender-affirming care is still legal are moronically obeying in advance to end gender-affirming care services for trans youths under 19 due to Donald Trump’s tyrannical executive order. Shame on these hospital for spitting on trans youths and their allies!

Hope most hospital systems get the hint and refuse to comply with Anti-Trans Bully 47’s hateful anti-GAC EO.

🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️

#Transgender Health#Transgender#LGBTQ+#Gender Affirming Care#Gender Affirming Healthcare#Gender Confirmation Surgery#Anti Trans Extremism#Donald Trump#Executive Orders#Executive Order 14187

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Client Must Agree to Chant a Satanic Abortion Ritual that they Claim is "Religious", Allowing Online Distribution of Abortion Pills

Dr Margaret Aranda Oct 30, 2024

Some emphases are mine.

Earlier this month, The Satanic Temple (TST) announced the opening of what it calls “the world’s second Satanic abortion clinic.”

“The term ‘clinic’ is certainly a stretch,” says Anne Reed, Senior Policy Advisor for Operation Rescue. “The ‘Right to Your Life Satanic Abortion Clinic’ is a landing page – not a building – where Virginia residents will be redirected to TST Health, The Satanic Temple’s virtual back-alley pill mill.”

TST opened its first “satanic abortion clinic” last year in New Mexico (also just a landing page that redirects to TST Health.) At that time, TST also announced “hopes to expand operations into other states, including those that do not allow clinicians to perform abortions.”

Working under the guise of a “religious” ritual and “religious abortion care,” TST aims to somehow establish these virtual clinics in states that are abortion free, leaning on religious freedom to get around protections for the preborn. Accordingly, only those “interested in performing TST’s abortion ritual” are eligible for medication abortion through TST. Agreeing to do the ritual is how one avoids paying extra costs beyond the $90 prescription for the abortion pills.

“Ending abortion has always been a spiritual battle,” says Troy Newman, President of Operation Rescue.”If America needs a reminder of that, look no further than these satanists strategizing to kill unborn children in states where those children are most protected, and drawing women into a narcissistic, spiritual ritual that glorifies the choosing of her life at the cost of someone else’s – her own child.”

The first words women are instructed to chant in the Satanic Abortion Ritual are, “One’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will alone.” The last words, after aborting the child, are, “By my body, my blood. By my will, it is done.”

“There was another Person in history who spoke of His Body and His Blood,” adds Newman. “Only He gave it that others might be saved. He spilled His blood so that His Father’s will – not His own – might be done. The words of this satanic ritual are a clear perversion of the words and work of Christ. “Abortion isn’t just about destroying babies. The spirit of abortion wants to destroy all humanity, as every human is an image bearer of God, the One Satan hates most.” When the first virtual clinic opened in 2023, Cosmopolitan magazine, which promotes itself as “the biggest young women’s media brand in the world,” ran a full story praising TST’s efforts. It also posted a collection of edgy images on social media that familiarized readers with each step of the satanic abortion ritual.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tens of thousands of Kaiser Permanente workers took to picket lines in multiple states on Wednesday, launching a massive strike that the company warned could cause delays at its hospitals and clinics that serve nearly 13 million Americans. The Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, representing about 85,000 of the health system’s employees nationally, approved a strike for three days in California, Colorado, Oregon and Washington, and for one day in Virginia and Washington, D.C. Some 75,000 people were expected to participate in the pickets. “Kaiser has not been bargaining with us in good faith and so it’s pushing us to come out here and strike,” said Jacquelyn Duley, a radiologic technologist among the hundreds of picketers at Kaiser Permanente Orange County - Irvine Medical Center. “We want to be inside just taking care of our patients.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abortion Rights in Virginia

In June 2022, the United States Supreme Court overturned the ruling of the landmark 1973 case Roe v. Wade, which had previously provided federal protections of the right to abortion.

With the responsibility of protecting the right to reproductive freedom left to the states, it can be difficult to keep track of all the constantly changing laws and regulations. To help, we’ve gathered the most important information on your state’s current laws, restrictions, and related details. Below is what you need to know about Virginia’s current abortion legislation.

*Please note, information on this website should not be used as legal advice or as a basis for medical decisions. Consult an attorney and/or a physician for your particular case.

Where does the law currently stand on abortion in the state of Virginia?

Abortion is currently legal but unprotected in the state of Virginia.

When did Virginia’s current abortion legislation go into effect?

The state of Virginia repealed its Pre-Roe v. Wade abortion ban back in 1975, and, since the overturning of Roe v Wade, has continued to legally allow abortion access up until the point of viability.

For more information on your state’s abortion legislation, see our breakdowns of various abortion bans, restrictions, and protections in the U.S.

Are there any legal restrictions to abortion access in the state of Virginia?

Currently, there are no restrictions to abortion access up until the point of viability, or the point at which a fetus is likely to survive outside of the uterus, typically occurring at 24 weeks.

Past this point, an abortion is allowed only when “continuation of the pregnancy is likely to result in the death of… or substantially and irremediably impair the mental or physical health of,” the pregnant individual, in which case this must be confirmed by three (3) physicians.

The specifics can be read in Virginia Legal Code 18.2-74

What protections are in place regarding abortion in the state of Virginia?

Reproductive Health Protection Act: While the state of Virginia does not legally protect the right to abortion, several medically unnecessary restrictions to abortion access were repealed in the 2020 Reproductive Health Protection Act.

Medical Funding: Virginia passed a law in 2021 removing the restriction on state insurance covering abortion.

The specifics can be read in the following Virginia Legal Codes SB 733, and SB 1276

I am pregnant in the state of Virginia and wish to terminate my pregnancy. What now?

If you believe your pregnancy meets the requirements for a legal abortion in your state, schedule an appointment with a trusted physician as soon as possible. If not, you will need to arrange an appointment at a clinic providing abortion services out of state. Make sure the state you choose allows abortions at the gestational age your pregnancy will reach by the appointment date.

If you need financial assistance to do this, there are existing funds to help cover both the procedure and travel costs.

Abortion funds can assist with the medical cost of the abortion itself. Practical Support Organizations, (PSOs), can assist with other costs incurred seeking an out-of-state abortion such as travel, lodging, childcare, provider referrals, emotional support, and judicial bypass for minors, among other needs. Here are a few resources available to those seeking support in Virginia:

Access Reproductive Care- Southeast [Fund & PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers financial aid and support for abortion, lodging, and transit. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

Blue Ridge Abortion Fund [Fund & PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers financial aid and support for abortion, lodging, and transit. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

Richmond Reproductive Freedom Project [Fund & PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers financial aid and support for abortion, lodging, transit, clinic escorts, food assistance, and childcare assistance. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

Whole Woman's Health- Abortion Wayfinder Program [Fund & PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers financial aid for abortion, lodging, and transit. See their website for more information.

DMV Abortion Practical Support Network [PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers support for lodging, transit, clinic escorts, food assistance, emotional support, and childcare assistance. See their website for more information.

DC Abortion Fund [Fund] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion from Virginia. Offers financial aid for abortion. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

National Abortion Hotline [Fund & PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion Nationwide. Offers financial aid for abortion, transit, and provider referrals. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

Women’s Reproductive Rights Assistance Project [Fund] – Provides funding for those seeking an abortion Nationwide. Offers financial aid for abortion and emergency contraception (the morning-after pill). See their website for more information.

Abortion Freedom Fund [Fund] – Provides funding for those seeking an abortion Nationwide. Offers financial aid for abortion. See their website for more information.

Indigenous Women Rising [Fund] – Provides funding for Indigenous individuals Nationwide seeking an abortion. Offers financial aid for abortion. See their website for more information.

Reprocare [PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion Nationwide. Offers aid in the form of provider referrals, emotional support, language services, and abortion doula services. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

The Brigid Alliance [PSO] – Provides support for those seeking an abortion Nationwide. Offers aid in the form of provider referrals, emotional support, language services, and abortion doula services. Provides Spanish language support. See their website for more information.

Regardless of the legislation your state currently has in place, remember that safe and legal options are always available. The most important tool you can arm yourself with in these difficult times is knowledge, so stay informed about changes in legislation and policy where you live, and know that there are always resources available to help you through this ♥️

#roe v wade#reproductive justice#virginia#abortion#reproductive health#reproductive freedom#pro choice#abortion access#supreme court#abortion ban#reproductive rights#women's rights#women's healthcare#abortion is healthcare#scotus#politics#feminism#planned parenthood

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Occupational Health Clinic near me in Chesapeake VA

Acorn Care is the best occupational health clinic in Chesapeake, VA. We provide a wide range of occupational health services including injury care, physical therapy, pre-employment services, employee wellness, drug tests, DOT physicals, safety screenings, and more.

#occupational health#occupational health services#occupational health clinic near me#pre employment physical near me#chesapeake occupational health#chesapeake occupational health solutions#occupational health and safety#occupational health screening#Chesapeake#Virginia#healthcare#acorn care

0 notes

Text

Since 2018, conservative state legislatures across the country have proposed and passed laws targeting young transgender people’s freedom to to play on sports teams and use bathrooms that correspond with their gender, and to obtain gender-affirming health care. Advocates for trans rights argue that the increased interest in the subject has served to galvanize the energies of those who had fought an ultimately losing battle against gay marriage—and have observed how the anti-trans movement has used tactics that have proved successful in limiting abortion. As with much legislation of this type, amid the nationalized, culture-war politics, the effects are felt most acutely by the most vulnerable families and individuals.

In a startling piece of reporting in this week’s issue, Emily Witt follows a mother named Kristen Chapman who moves her family from Tennessee to Virginia, in order for her daughter Willow to continue receiving gender-affirming care. “I genuinely feel we are being run out of town on a rail,” Chapman says. “I am not being dramatic. It is not my imagination.” With nuance and compassionate precision, Witt captures the urgency of the family’s relocation, and the sense, as laws seem to change underfoot, of pursuit. As she writes, “Chapman had chosen Virginia for their new life, she said, because it was still in the South, but there would be ‘multiple avenues of escape.’ ”

On the last morning of July, Kristen Chapman was getting ready to leave Nashville. Chapman, who is in her early fifties and wears her silver hair short, sat on a camp chair next to a fire pit outside the rental duplex where her family had lived for twelve years. She was smoking an American Spirit and swatting at the mosquitoes that kept emerging from the dense green brush behind her. Her husband, Paul, who was wearing a T-shirt with the Guinness logo, carried boxes out to the front lawn. Their daughters, Saoirse and Willow, who were seventeen and fifteen, were inside, still asleep. Chapman looked down at the family’s beagle mix, Obi-Wan Kenobi, who was drinking rainwater out of a plastic bucket. “We got him when we moved in here for the kids,” she said. “He’s never lived anywhere else.”

Paul was planning to stay in town; Chapman was heading to Richmond, Virginia, with Saoirse and Willow. Chapman and Paul’s marriage was ending, but the decision to split their family apart had happened abruptly. Willow is trans, and had been on puberty blockers since 2021. In March, Tennessee’s governor, Bill Lee, had signed a bill that banned gender-transition treatment for minors across the state.

On paper, the law, which went into effect in early July, would allow trans teens like Willow to continue their medical care until March of 2024. But Chapman wasn’t sure they could count on that. Willow was determined to begin taking estrogen when she turned sixteen, in December of 2023, which would allow her to grow into adulthood with feminine characteristics. If she couldn’t continue taking puberty blockers until then, she would begin to go through male puberty, which could mean more surgeries and other procedures later in life.

At first, the family had hoped that the courts would declare the new law unconstitutional. Federal courts had already done so in at least four other states in 2023, finding that such bans violated the First Amendment and the equal-protection and due-process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. But that spring the Pediatric Transgender Clinic at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where Willow had been receiving care, informed its patients that it was ceasing operations. Seeing this as a bad sign, Chapman set up a GoFundMe page in early May and began planning their departure.

Inside, the apartment was filled with abandoned objects—an old Wi-Fi router, trash bags of unwanted clothes. A Homer Simpson doll in a hula skirt lay forgotten on a windowsill. Chapman, an artist who supplements her income with social work, had recently quit her job as a caseworker. She would need their landlord as a reference to get an apartment, especially because she had bad credit, but the family still owed him back rent. She checked Venmo, waiting on a loan from a friend.

At six-thirty that morning, Chapman had gone out to her white Dodge S.U.V. and found her younger daughter asleep in the back seat. Willow had gone over to a friend’s house and stayed out late. When she got home, she realized that she had locked herself out. The Dodge’s window had been stuck open for months, so she got in. “Any other human being would have handled this totally differently,” Chapman said, shaking her head.

Willow had gone back to sleep in her room, which she once shared with her brother. (He was a sophomore in college and had already moved out.) The colorful scarves and lights that used to decorate the space had been taken down. When she woke up, she began sifting through what was left. “I feel like I’m ready to say goodbye to it,” she said, looking around. There were drawings scrawled on the wall, a desk spattered in paint. “Most of the stuff in here I’ve trashed.”

“It’s like getting a new haircut,” Chapman said. “A fresh palette.”

Chapman had chosen Virginia for their new life, she said, because it was still in the South, but there would be “multiple avenues of escape.” Paul worked nights for a large grocery-store chain; Richmond was among the northernmost cities where it had branches, and Chapman thought that at some point he might be able to transfer there. Earlier in the summer, she and Willow had driven to Richmond to see the city, and Chapman had lined up a marketing job. It didn’t pay well, but she knew she wouldn’t get a lease without a job. Willow, who had received her last puberty-blocker shot at the Vanderbilt clinic in late May, was supposed to receive her next one in late August. They didn’t have a lot of time.

Despite having taken puberty blockers for two years, Willow looks her age. She is tall and long-limbed and meticulous about her appearance. That morning, she had on Y2K-revival clothes: wide-legged jeans worn low on the hips with a belt, a patterned tank top, and furry pink Juicy Couture boots. Her blond hair was glossy and straight, her bangs held back with a barrette. She is committed to living her adolescence as a girl regardless of what medical treatment she is allowed to receive. At times she has used silicone prosthetic breasts; attaching them is an onerous process involving spray-on adhesive.

From a very young age, Willow wore dresses and gravitated toward friendships with girls. Her parents thought that she would likely grow up to be a gay man. As Chapman put it, “We knew she was in the fam.” When a homophobic shooter killed forty-nine people at Pulse, the gay night club in Orlando, in 2016, Willow, who was eight at the time, accompanied her mother to a vigil in Nashville. Willow wrote a long message on a banner in solidarity with the survivors. Chapman took a photo of her there. “It was like she was transfixed,” Chapman remembered. In the sixth grade, Willow went to an all-girl sleepover. A parent overheard the kids discussing gender and sexuality, and told Chapman. Willow says that it was around then that she began to think about her identity. “Pretty much as soon as I knew about, like, conceptualized gender, I knew I wanted to be a girl,” she said. She had been an A student, but her grades started going down. Looking back, Willow struggled to articulate what had happened. “It just got complicated, like with all my stuff physically, it just felt like a mess,” she said.

She came out to her friends first; then one day, in the spring of 2020, while she was upstairs on her laptop and Chapman was downstairs working, Willow sent her mother a three-word e-mail that said, “I am trans.” Willow told me, “I realized I have to do this sometime if I want to advocate for myself and get what I need to get.” She left it to her mother to inform the rest of the family. Chapman was accepting; Paul was more skeptical. “That’s him, you know—a man of science,” Chapman said. “It wasn’t overly positive or negative.”

Willow had already decided on her new name before coming out, and began using it with friends. She was again reluctant to tell her family. “I was, like, I’ll keep that secret,” she said—she had been named at birth for a brother of her father’s who had died, and knew the name was important to him. Her mother found out when another mom referred to Willow by her chosen name. Chapman started using it right away; it took Paul another year.

To figure out their next steps, Chapman took Willow, who was then twelve, to her regular pediatrician at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. She was referred to the center’s Pediatric Transgender Clinic. The clinic, which opened in 2018, was part of a broader expansion of gender-affirming care at flagship medical schools in the South that occurred around that time. (Clinics also opened at Duke University, the University of Mississippi, and Emory University, among other schools.) These places “attracted the kind of people who build very trusting relationships with patients and are able to establish not just the clinical competencies but also an inclusive environment,” Jasmine Beach-Ferrara, the executive director of the Campaign for Southern Equality, an advocacy group for L.G.B.T.Q. rights, told me. “All those things are nothing you can take for granted when seeking medical care in the South.” (Federal funding for health care is often funnelled through state governments, some of which have a history of withholding money from providers that offer abortion and other politicized health services.)

Care for patients who are experiencing gender dysphoria is highly individualized: some trans kids opt for a purely social transition, changing their names or pronouns; others, like Willow, seek a medical transition, which can be started at the onset of puberty. In Willow’s case, a diagnosis of gender dysphoria had to be verified before pharmaceutical treatment could begin. A course of psychotherapy was accompanied by a physical assessment at Vanderbilt, which included ultrasounds, X-rays, and blood tests. The clinic was following a protocol supported by the Endocrine Society and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, whereby patients take puberty blockers—which have been used to treat children experiencing early-onset puberty since the nineteen-eighties—to delay the onset of secondary sex characteristics until they are ready to begin taking estrogen or testosterone.

“I’d always explain it to the families as a pause on puberty, allowing the youth to take a deep breath,” Kimberly Herrmann, a pediatrician and internist at Whitman-Walker Health, a provider in the Washington, D.C., area that offers gender-affirming care to patients aged thirteen and over, told me. (Some patients choose to go through their natal puberty.) “All of the data suggests that it is the correct thing to do for a patient with a clear diagnosis,” Izzy Lowell, a doctor who started a telehealth practice for gender-affirming care called QueerMed, said, of taking puberty blockers. “If they are going to develop the body of a grown man, it becomes difficult to undo those changes.”

Paul was worried about the blockers’ long-term effects on Willow’s health. (Studies have shown that they can affect bone density when used long term, and the protocol for hormone therapy advises doctors to discuss potential risks to fertility and options for fertility preservation.) Chapman thought the risks to Willow’s well-being would be worse if she developed male secondary sex characteristics. In one testimony against the Tennessee ban, an adult trans woman described her adolescence, in which she attempted to present as male, as “a disastrous and torturous experience.”

“Paul and I talked about it and came to the belief that we wanted her on them as quickly as possible for safety reasons,” Chapman said. “I hate that that’s true, but we know that’s the world that we live in, and that she is going to be a safer person for the rest of her life if she does not look male.” (A recent analysis of crime statistics from 2017 and 2018 found that transgender people are more than four times as likely as cisgender people to be the victims of a violent crime.)

The evaluation and diagnosis took almost a year. For Willow, the talk therapy was the most taxing part. Willow was insured through the state’s Medicaid program, TennCare, which meant that there were only a limited number of therapists she could see, none of whom were trans, or even queer. She went through three in a year. “We were in the lowest tier of care,” Chapman said, adding that at least one therapist dropped their health insurance. Willow told her mother that she wished she could just be left alone to be a “sad trans girl.”

At the age of thirteen, she was finally able to start puberty blockers. “You have an end goal,” Willow said of the experience. “And all the in-between doesn’t matter.”

In September, 2022, the conservative commentator and anti-trans activist Matt Walsh, who moved to Nashville in 2020 (along with his employer, the conservative news company the Daily Wire), posted a thread on Twitter. “Vanderbilt drugs, chemically castrates, and performs double mastectomies on minors,” it began. “But it gets worse.” Walsh—who is the author of books including “Church of Cowards: A Wake-Up Call to Complacent Christians” and “What Is a Woman?,” a polemic arguing that gender roles are biologically determined—worked in conservative talk radio before being hired by the Daily Wire as a writer, in 2017. Last year, the left-wing watchdog group Media Matters for America mapped Walsh’s origins as an aspiring radio shock jock in the early twenty-tens who once said, “We probably lost our republic after Reconstruction.” In 2022, he was one of several right-wing social-media pundits who began broadcasting misinformation about hospitals that provided gender-transition treatment for minors, which were then overwhelmed with phone and e-mail threats and online harassment. One study found that more than fifteen hospitals modified or took down Web sites about pediatric gender care after being named in these campaigns.

Walsh included in his thread about Vanderbilt a video clip of Shayne Taylor, the medical director of its Transgender Clinic, speaking of top and bottom surgeries as a potential “money-maker” for the hospital. Walsh did not specify that Taylor was mostly speaking about adults. (Vanderbilt never performed genital surgery on underage patients and did an average of five top surgeries a year on minors, with a minimum age of sixteen.) More than sixty Republican state legislators signed a letter to Vanderbilt describing the clinic’s practices “as nothing less than abuse.” In a statement calling for an investigation, Governor Lee, who was up for reëlection, said that “we should not allow permanent, life-altering decisions that hurt children.” Within days, Vanderbilt announced that it would put a pause on surgeries for minors. Jonathan Skrmetti, Tennessee’s Republican attorney general, began an inquiry into whether Vanderbilt had manipulated billing codes to avoid limitations on insurance coverage.

In October, Walsh and other anti-trans advocates held a “Rally to End Child Mutilation” in Nashville’s War Memorial Plaza. The speakers included the Tennessee senator Marsha Blackburn, the former Democratic Presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard, and Chloe Cole, a nineteen-year-old self-described “former trans kid.” After identifying as male from the age of twelve, receiving testosterone, and getting top surgery, Cole de-transitioned to female at sixteen and is now one of the country’s foremost youth advocates of bans on gender-transition treatment for minors. “I was allowed to make an adult decision as a traumatized fifteen-year-old,” she said at the rally.

For the past four years, the number of anti-trans bills proposed throughout the United States has dramatically risen. The A.C.L.U. has counted some four hundred and ninety-six proposals in state legislatures in 2023, eighty-four of which have been signed into law. The first state ban on gender-transition treatment for minors was passed in Arkansas in 2021. It was permanently blocked by a federal judge this year, but more than twenty states have passed similar laws since then. As lawsuits filed by the A.C.L.U., Lambda Legal, and other organizations make their way through the courts, trans people are left to navigate a shifting legal landscape that activists say has affected clinical and pharmaceutical access. Lowell told me that she consults with six lawyers (including one she keeps on retainer) to best advise patients, who must frequently drive across state borders to receive care. “It’s literally a daily task to figure out what’s legal where,” she said.

In Tennessee, the Human Rights Campaign has counted the passage of at least nineteen anti-L.G.B.T.Q. laws since 2015, among the most in the nation. Some of these laws have been found unconstitutional, such as a ban on drag shows in public spaces and a law that would have required any business to post a warning if it let transgender people use their preferred rest room. But many others have gone into effect, such as laws that censor school curricula and ban transgender youth from playing on the sports teams that align with their identity.

Proposals to ban gender-transition treatment for minors were the first bills introduced in the opening legislative sessions of the Tennessee House and Senate in November, 2022. “It was Matt Walsh who lit a fire under the ultraconservative wing of the Republican Party this year,” Chris Sanders, the director of a Nashville-based L.G.B.T.Q. advocacy group called Tennessee Equality Project, told me. “It was lightning speed the way it all unfolded.” At hearings throughout the winter, parents of trans kids, trans adults, trans youth, and a Memphis pediatrician who provides gender-affirming care testified against the ban. Those who spoke in support of it included Walsh, Cole (who is from California), and a right-wing Tennessee physician named Omar Hamada, who compared such treatment to letting a minor who wanted to become a pirate get a limb and one eye removed.

L.G.B.T.Q. activists who attended described feeling disregarded by the Republican majority. Molly Quinn, the executive director of OUTMemphis, a nonprofit that helps trans youth navigate their health care, likened the experience to “being the only queer kid at a frat party.”

Three months after Governor Lee signed the ban, Vanderbilt University Medical Center informed patients that the previous November, at the attorney general’s request, it had shared non-anonymized patient records from the Pediatric Transgender Clinic, including photographic documentation and mental-health assessments. “I immediately started hearing from parents,” Sanders said. Their fear stemmed in part from attempts in states like Texas to have the parents of trans kids investigated by child-protective services. (The attorney general’s office said in a statement that it is “legally bound to maintain the medical records in the strictest confidence, which it does.”) Former patients have sued Vanderbilt, and a federal investigation by the Department of Health and Human Services is also under way. (A spokesperson for Vanderbilt declined to comment for this article.)

In July, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals became the first federal court in the country to allow a ban on gender-transition treatment for minors to take effect, with a final ruling planned for September. Chapman, who had spoken out for trans rights through local media outlets, and had been targeted with online threats and menacing phone calls in return, understood that Tennessee, where she had lived for most of the past thirty-five years, had become a hostile environment for her family. “I genuinely feel we are being run out of town on a rail,” she said. “I am not being dramatic. It is not my imagination.”

It was dusk by the time Paul had loaded the last of the boxes into three storage pods. Everything was ready, but the family was having trouble leaving. Someone would walk out of the house and get into the car, only to go back into the house five minutes later. Chapman suddenly remembered that she had forgotten to buy padlocks for the storage pods, which were scheduled to be picked up by U-Haul the next day. As she drove off to get them, Paul sat on the back steps and stared out at the lawn. Fireflies were winking on and off over the grass.

“Bollocks,” he said to himself, then stood up and went inside.

Although comprehensive demographic data on transgender youth are scarce, the American Academy of Pediatrics has reported that “research increasingly suggests that familial acceptance or rejection ultimately has little influence on the gender identity of youth.” But without parental consent most kids in America who wish to transition medically are legally unable to do so until they turn eighteen. Having a supportive parent or guardian as a trans child is more than a legal or practical advantage, though. A study of eighty-four youth in Ontario, aged sixteen to twenty-four, who identified as trans and had come out to their parents found that the rate of attempted suicide was four per cent among those whose parents were strongly supportive but that nearly sixty per cent of respondents who described their parents as not supportive had attempted suicide in the previous year.

Chapman’s decision to support her daughter grew in part out of her own experience as a black sheep in a deeply religious family. She was born in East Tennessee to a Baptist minister and his wife and had an itinerant upbringing, moving around the South. The last words her grandfather, who was also a Baptist minister, said to her were “I’m so sorry I’m not gonna see you in Heaven.”

Paul was raised in Dublin, Ireland, as the youngest of twelve children in a Catholic family. “We both came from communities that were super fundamentalist,” Chapman said. They agreed that they would raise their children outside of any religious tradition. If they had a doctrine, Chapman said, it was “critical thinking.” They brought their kids to Black Lives Matter demonstrations, and took them to hear the Georgia congressman and civil-rights activist John Lewis speak. But Paul and Kristen would also listen to the far-right radio host Rush Limbaugh, to know what the other side was saying. As the children got older, Paul and Kristen started to have different visions of the future—Kristen wanted to buy an R.V. and travel the country, and Paul wanted to buy a house. In 2019, they decided to separate, but they couldn’t afford to split their family into two households.

Paul at first had trouble understanding how Willow could decide about her gender so young. Kristen would argue, “If a person presents and says, ‘This is who I am,’ it is not your job to unpack that.” In the end, it was by talking to two trans women—a co-worker in her fifties and a twentysomething bartender at the pub he frequented—that Paul came to understand his daughter better. “Reading online was too much right-wing or left-wing,” he said. “I needed something more grounded.” The bartender told him that her father had rejected her, and that she had scars on her arms from self-harm. “I said, no matter what, I wasn’t doing that,” Paul recalled.

Willow had told me that one of the hardest parts of leaving town was doing so while her relationship to her father was still evolving. “I feel like my biggest unfinished business is that relationship,” she said the day before the move, over boba tea in a strip mall called Plaza Mariachi. “I think I’ve dealt with it. We’ll talk on the phone. Even if we don’t have an in-person connection, I think we’ll be O.K.”

Once they all managed to leave the house for the last time, Paul gave Chapman and each daughter a hundred dollars in cash as a parting gift. The family had dinner at Panera Bread, then sat for a while at a nearby park. Paul cancelled two Lyfts before finally getting in one and heading to the pub, where he would try to process the day. Chapman and the girls got in the white Dodge and took I-24 out of Nashville.

L.G.B.T.Q.-rights activists around the country have seen the sudden uptick in bills targeting transgender identity as a strategy to rally conservative voters after the legalization of gay marriage and the criminalization of abortion. “There was an inordinate amount of money and attention and huge far-right groups, many of which have been deemed hate groups, focussed on keeping us as L.G.B.T.Q. people from getting married, right?” Simone Chriss, a Florida-based lawyer, told me. Chriss is representing trans people in several lawsuits against the state over its restrictions on gender-affirming care. She observed that, after the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage, in 2015, “all of the people singularly focussed on that needed something else to focus on.”

She recalled watching as model legislation propagated by groups such as the Alliance Defending Freedom and the Family Research Council targeted trans people’s freedom to use bathrooms of their choice, and to play on their preferred sports teams. Health care came next. “All of a sudden, you see this surge in gender-affirming-care bills,” Chriss said. “And what’s bananas is there was not a single bill introduced in a single state legislature prior to 2018.”

The anti-trans rhetoric about protecting children mirrored that of the anti-gay-marriage movement, she continued, and new rules mandating waiting periods, for example, were familiar from the anti-abortion movement. “It’s like dipping a toe in by making it about trans children,” she said. “I think the goal is the erasure of trans people, in part by erasing the health care that allows them to live authentically.”

Beach-Ferrara, of the Campaign for Southern Equality, said her organization estimates that more than ninety per cent of transgender youth in the South live in states where bans have passed or will soon be in effect, and that between three and five thousand young people in the South will have ongoing medical care disrupted by the bans. (The Williams Institute at U.C.L.A. estimates that there are more than a hundred thousand thirteen-to-seventeen-year-olds who identify as trans living in the South, more than in any other region in the country.) Already, university hospitals such as the University of Mississippi Medical Center and the Medical University of South Carolina have discontinued their pediatric gender services before being legally required to do so.

Had Chapman stayed in Tennessee, Willow’s closest option for getting puberty-blocker shots would likely have required a four-hundred-and-fifty-mile trip to Peoria, Illinois. Willow’s TennCare insurance would not easily travel, and a single shot can cost twelve hundred dollars out of pocket. Paul had told Chapman not to be ashamed if the move didn’t work out and she changed her mind, but she already knew she would never go back to Nashville.

On their way east, the family stopped for a few days in Seneca, South Carolina, where Chapman has relatives. Back on the road, she tried not to focus on the uncertainty that awaited her and her daughters, but she had to pull over at least twice to breathe her way through anxiety attacks. There was a heat wave, and by the time they arrived in Richmond the back speakers of the S.U.V. were blown out, and everyone was in a bad mood. Willow had snapped at her mother and Saoirse for trying to sing along to the Cranberries; she had even yelled at the dog. “It was difficult?” Willow told me afterward, when I asked how the trip had been; then she added, “I’m still excited.” (Saoirse declined to be interviewed.)

Chapman had booked an Airbnb, a dusty-blue bungalow outside Richmond. It had good air-conditioning and a small back yard for the dog. She could afford only a week there before they would have to move to a motel. That night, Willow zoned out to old episodes of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” in the living room, while Chapman scrolled through real-estate listings on her phone. She asked for advice on the social-media feeds of local L.G.B.T.Q. groups, and the responses were heartening. She decided that, if she was able to find a place to live by the end of the week, she would not take the marketing job she had lined up. School wouldn’t start for a few weeks, and it was not the right moment to leave her daughters alone all day.

At eight the next morning, Chapman was sitting in an otherwise empty waiting room at the Southside Community Services Center, filling out forms to get the family food stamps and health insurance. She had put on makeup for the first time in days and was wearing wide-legged leopard-print pants and a black shirt. She had forgotten her reading glasses, however. “Do you have a spouse who does not live at home?” she read out loud, squinting her way through the questions. “Yes,” she answered to herself, checking a box. (She and Paul are not yet divorced.)

Chapman kept mistakenly writing “Willow” on the government forms—she had never officially changed her daughter’s name. (A 1977 Tennessee state law that prohibits amending one’s gender on a birth certificate will apply to Willow no matter where she moves; another Tennessee law, which went into effect this past July, bans people from changing the gender on their driver’s license.) Chapman picked up the next batch of forms, for Medicaid. “One down, one to go,” she said.

Later in the day, Chapman and her daughters went to see a house that was advertised on Craigslist, an affordable three-bedroom in the suburbs of Richmond. As they were driving, the owner texted Chapman that he had a flat tire and couldn’t meet them. But the place looked ideal from the outside, so she filled out an application and sent the landlord a thousand-dollar deposit. At five the next morning, she woke up and saw a text from the owner claiming that the money transfer had not gone through. She quickly realized she’d been scammed.

Chapman became weepy. She posted on social media about the con, then drove Saoirse to a thrift store she wanted to visit. At first, only one shopper noticed the woman crying uncontrollably in the furniture section. Then someone went to find some tissues, and someone else brought water. Soon, Chapman recalled, she was surrounded by women murmuring words of sympathy.

That evening at the Airbnb, Chapman and Willow sat at the kitchen table. “The emotional impact of the scam hit me way more than the money,” Chapman said, still tearing up at the thought of it. Willow nodded in sympathy. But for Chapman the experience was also a reminder of the advantages of talking about their situation—the women had told her that the schools near the house were not very good, anyway. “Thrift-store people will help you when you’re down and out. They’re used to broken shit,” she said, shaking her head. “If I had broke down in a Macy’s? Think how different the reaction would be.”

The next morning, Chapman was feeling a little less pessimistic. The humidity had broken, and the weather was good. People had responded to the news of the scam by donating money to replace what she had lost, and a local Facebook group had led her to a property-management company that was flexible toward tenants with bad credit.

She drove to see a three-bedroom apartment in a centrally situated part of Richmond. Though one of the bedrooms was windowless, the place was newly painted, and it had a wooden landing out back that could serve as a deck. It was also in a school district that people had recommended. “I can see this working,” Chapman said tentatively. Most of the utilities were included in the sixteen-hundred-and-fifty-dollar rent. Chapman didn’t have time to overthink it. She wrote the real-estate agent saying she would apply.

That afternoon, Chapman drove Willow to see the apartment. The door was locked, but Willow climbed through a window and opened the door so they could consider the space together. “We were, like, ‘Oh, this is nice,’ ” Willow said. She loved the neighborhood, which had vintage stores and coffee shops. “You can walk anywhere, you don’t need transportation—that’s really cool.”

The next day, Willow was sitting on a couch in the Airbnb watching a slasher film called “Terrifier.” Chapman was next to her, getting ready for a Zoom call with someone from a local trans-rights organization called He She Ze and We.

In the weeks leading up to the move, Chapman had taken time to research which schools were friendly to trans people. Willow estimated that maybe half the students in her middle school in Nashville were transphobic, and twenty per cent were explicit about it. She was bullied, but she says that it didn’t bother her. Her teachers were more supportive, such as the one who gave her an entire Lilith Fair-era wardrobe. “She was, like, ‘Do you want some of my old clothes? Because you’re so fashion,’ ” Willow said. “I had that black little bob.”

“She had Siouxsie Sioux hair for a while,” Chapman said, looking at her fondly.

The two of them agree that Willow’s personality shifted after transitioning. Once withdrawn and nonconfrontational, she began to develop a defiant attitude. “It was kind of fun to just mess with them,” she recalled of the bullies, who she said were not vicious but more into trying to get a laugh—“like, childish, immature stuff.” She would be coy; she would tell them to give her a kiss. “My only weapon, I guess, was how I chose to respond,” she said.

“She’s not a shrinking violet,” her mother added.

“I just don’t like the traditional way that you’re taught to stand up for yourself,” Willow said. “I think absurdism is the best way.” If she lets someone misgender her, she said, “it’s not because I don’t want to be the annoying trans person, it’s more like . . . you’re not gonna get to those people.”

In her freshman year, she attended a public arts high school, and began skipping class and smoking. She says there were at least ten other students who identified as trans, but she remained something of an outsider. When she was in school, she says, she almost thought of herself as a kind of character expected to perform.