#Velayat-e-faqih

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

How is one chosen as an Ayatollah?

Through decades of outstanding scholarly work, which inspires the devotion of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of followers. A typical ayatollah’s career takes him to one of the Shiites’ holy cities, like Najaf in Iraq or Qom in Iran. There, he studies at one of the pre-eminent Shiite seminaries, where he becomes an expert in theology, jurisprudence, science, and philosophy. After years…

View On WordPress

#Ayatollah#Caliph and Imam#Divine Providence#Fivers--Zaydis#Grand Ayatollah#Hajatolislam#Imam#Ismailis#Majlis faqih#Maraja#Nass#Shiism#Taqlid#Twelvers#Velayat-e-faqih

0 notes

Text

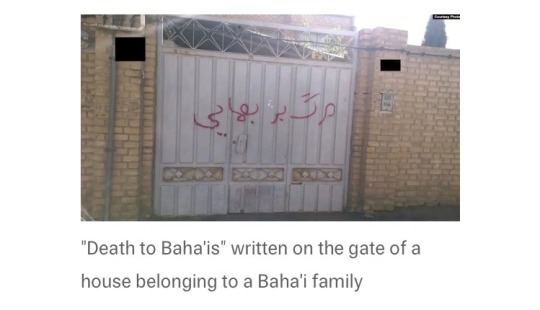

"This report, Outsiders: Multifaceted Violence Against Baháʼís in the Islamic Republic of Iran, jointly produced by Abdorahhman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran and Eleos Justice (Faculty of Law, Monash University), examines the persecution of Bahá’ís through two frameworks: Johan Galtung’s theory of violence — direct, structural, and cultural — and international criminal law. Drawing on diverse sources, including over 50 interviews with Baháʼís, the report provides unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of persecution and calls for international awareness and accountability.

The Bahá’í faith, established in 1844, has faced continuous and intense persecution in Iran, marked by violence, discrimination, and a systematic denial of rights. Initially, Bahá’ís experienced mob violence and various forms of state-sanctioned oppression, which worsened after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The new regime viewed the Bahá’í community as a theological and ideological threat, reinforcing exclusionary policies under the doctrine of Velayat-e Faqih, which left no room for religious diversity.

State violence against Bahá’ís has ranged from executions, enforced disappearances, torture, and physical abuse, to the destruction of property, including homes, businesses, and cemeteries. Hundreds of Bahá’í properties have been confiscated, leaving families without recourse and with lingering trauma.

Apart from physical violence, Bahá’ís in Iran suffer structural and cultural discrimination. The constitution excludes Bahá’ís from recognized religious minorities, denying them basic rights to education, employment, and property. A 1991 memorandum further formalized policies aimed at limiting Bahá’í socioeconomic progress. Recently, Bahá’ís have been denied marriage registration, complicating legal matters around family and inheritance.

Culturally, the State perpetuates anti-Bahá’í sentiment through propaganda and misinformation, portraying Bahá’ís as foreign agents or morally corrupt. This narrative permeates educational materials, fostering discrimination among students and teachers. However, there is growing resistance among Iranians, with some expressing support for the Bahá’í community.

Under international law, these systematic actions against Bahá’ís constitute crimes against humanity, including murder and persecution, though they fall short of the legal definition of genocide. Despite Iran’s non-participation in the Rome Statute, the principle of universal jurisdiction allows for potential prosecution by other nations, marking an ongoing international concern for the Bahá’ís’ plight in Iran.

Read the full report in PDF format."

#baha'i faith#baha'is in iran#iranian baha'is#iranian regime#state sanctioned violence#state sanctioned oppression#religious persecution#state sanctioned persecution#the persecution of baha'is in iran

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The death of Mahsa Amini on 16 September 2022, while in police custody for wearing an “improper” hijab, has triggered what has become the most severe and sustained political upheaval ever faced by the Islamist regime in Iran. Waves of protests, led mostly by women, broke out immediately, sending some two-million people into the streets of 160 cities and small towns, inspiring extraordinary international support.1 The Twitter hashtag #MahsaAmini broke the world record of 284 million tweets, and the UN Human Rights Commission voted on November 24 to investigate the regime’s deadly repression, which has claimed five-hundred lives and put thousands of people under arrest and eleven hundred on trial. The regime’s suppression and the opponents’ exhaustion are likely to slow down the protests, but unlikely to end the uprising. For political life in Iran has embarked on an uncharted and irreversible course.

How do we make sense of this extraordinary political happening? This is neither a “feminist revolution” per se, nor simply the revolt of Generation Z, nor merely a protest against the mandatory hijab. This is a movement to reclaim life, a struggle to liberate free and dignified existence from an internal colonization. As the primary objects of this colonization, women have become the major protagonists of the liberation movement.

About the Author

Asef Bayat is professor of sociology, and Catherine and Bruce Bastian Professor of Global and Transnational Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. His latest books include Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring (2021).

View all work by Asef Bayat

Since its establishment in 1979 Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s, the Islamic Republic has been a battlefield between hardline Islamists who wished to enforce theocracy in the form of clerical rule (velayat-e faqih), and those who believed in popular will and emphasized the republican tenets of the constitution. This ideological battle has produced decades of political and cultural strife within state institutions, during elections, and in the streets in daily life. The hardline Islamists in the nonelected institutions of the velayat-e faqih have been determined to enforce their “divine values” in political, social, and cultural domains. Only popular resistance from below and the reformists’ electoral victories could curb the hardliners’ drive for total subjugation of the state, society, and culture.

For two decades after the 1990s, elections gave most Iranians hope that a reformist path could gradually democratize the system. The 1997 election of the moderate Mohammad Khatami as president, following a notable social and cultural openness, was seen as a hopeful sign. But the hardliners saw the reform project as an existential threat to clerical rule, and they fought back fiercely. They sabotaged Khatami’s government, suppressed the student movement, shut down the critical press, and detained activists. After 2005, they went on banning reformist parties, meddling in the polls, and barring rival candidates from participating in the elections. The Green Movement—protesting the fraud against the reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi in the 2009 presidential election—was the popular response to such a counterreform onslaught.

The Green revolt and the subsequent nationwide uprisings in 2017 and 2019 against socioeconomic ills and authoritarian rule profoundly challenged the Islamist regime but failed to alter it. The uprisings caused not a revolution but the fear of revolution—a fear that was compounded by the revolutionary uprisings against the allied regimes in Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, which Iran helped to quell.2 Against such critical challenges, one would expect the Islamist regime to reinvent itself through a series of reforms to restore hegemony. But instead, the hardliners tightened their grip on political power in a bid to ensure their unrestrained hold over power after the supreme leader expires. Thus, once they took over the presidency in 2021 and the parliament in 2022 through rigged elections—specifically, through the arbitrary vetoing of credible rival candidates—the hardliners moved to subjugate a defiant people once again. Extending the “morality police” into the streets and institutions to enforce the “proper hijab” has been only one measure—but it was the one that unleashed a nationwide uprising in which women came to occupy a central place.

Women did not rise up suddenly to spearhead a revolt after Mahsa Amini’s death. Rather, it was the culmination of years of steady struggles against a systemic misogyny that the postrevolution regime established. When that regime abolished the relatively liberal Family Protection Laws of 1967, women overnight lost their right to initiate divorce, to assume child custody, to become judges, and to travel abroad without the permission of a male guardian. Polygamy came back, sex segregation was imposed, and all women were forced to wear the hijab in public. Social control and discriminatory quotas in education and employment compelled many women to stay at home, take early retirement, or work in informal or family businesses.

A segment of Muslim women did support the Islamic state, but others fought back. They took to the streets to protest the mandatory hijab, organized collective campaigns, and lobbied “liberal clerics” to secure a women-centered reinterpretation of religious texts. But when the regime extended its repression, women resorted to the “art of presence”—by which I mean the ability to assert collective will in spite of all odds, by circumventing constraints, utilizing what exists, and discovering new spaces within which to make themselves heard, seen, felt, and realized. Simply, women refused to exit public life, not through collective protests but through such ordinary things as pursuing higher education, working outside the home, engaging in the arts, music, and filmmaking, or practicing sports. The hardship of sweating under a long dress and veil did not deter many women from jogging, cycling, or playing basketball. And in the courts, they battled against discriminatory judgments on matters of divorce, child custody, inheritance, work, and access to public spaces. “Why do we have to get permission from Edareh-e Amaken [morality police] to get a hotel room, whereas men do not need such authorization?” a woman wrote in rage to the women’s magazine Zanan in 1988.3 Then, scores of unmarried women began to leave their family homes to live on their own. By 2010, one in three women between the ages of 20 and 35 had their own household. Many of them undertook what came to be known as “white marriage” (ezdevaj-e sefid), that is, moving in with their partners without formally marrying. These seemingly mundane desires and demands, however, were deemed to redefine the status of women under the Islamic Republic. Each step forward would establish a trench for a further advance against the patriarchy. The effect could snowball.

While many women, including my mother, wore the hijab voluntarily, for others it represented a coercive moralizing that had to be subverted. Those women began to push back their headscarves, allowing some of their hair to show in public. Over the years, headscarves gradually inched back further and further until finally they fell to the shoulders. Officials felt, time and again, paralyzed by this steady spread of bad-hijabi among millions of women who had to endure daily humiliation and punishment. With the initial jail penalty between ten days and two months, showing inches of hair had ignited decades of daily street battles between defiant women and multiple morality enforcers such as Sarallah(wrath of Allah), Amre beh Ma’ruf va Nahye az Monker(command good and forbid wrong), and Edareh Amaken(management of public places). According to a police report during the crackdown on bad-hijabis in 2013, some 3.6 million women were stopped and humiliated in the streets and issued formal citations. Of these, 180,000 were detained. But despite such treatment, women did not relent and eventually demanded an end to the mandatory hijab. Thus, over the years and through daily struggles, women established new norms in private and public life and taught them to their children, who have taken the mantle of their elders to push the struggle forward. The hardliners now want to halt that forward march.

This is the story of women’s “non-movement”—the collective and connective actions of non-collective actors who pursue not a politics of protest but of redress, through direct actions. Its aim is not a deliberate defiance of authorities but to establish alternative norms and life-making practices—practices that are necessary for a desired and dignified life but are denied to women. It is a slow but steady process of incremental claim-making that ultimately challenges the patriarchal-political authority.4 And now, that very “non-movement,” impelled by the murder of one of its own, Mahsa Amini, has given rise to an extraordinary political upheaval in which woman and her dignity, indeed human dignity, has become a rallying point.

Reclaiming Life

Today, the uprising is no longer limited to the mandatory hijab and women’s rights. It has grown to include wider concerns and constituencies—young people, students and teachers, middle-class families and workers, residents of some rural and poor communities, and those religious and ethnic minorities (Kurds, Arabs, Azeris, and Baluchis) who, like women, feel like second-class citizens and seem to identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” For these diverse constituencies, Mahsa Amini and her death embody the suffering that they have endured in their own lives—in their stolen youth, suppressed joy, and constant insecurity; in their poverty, debt, and drought; in their loss of land and livelihoods.

The thousands of tweets describing why people are protesting point time and again to the longing for a humble normal life denied to them by a regime of clerical and military patriarchs. For these dissenters, the regime appears like a colonial entity—with its alien thinking, feeling, and ruling—that has little to do with the lives and worldviews of the majority. This alien entity, they feel, has usurped the country and its resources, and continues to subjugate its people and their mode of living. “Woman, Life, Freedom” is a movement of liberation from this internal colonization. It is a movement to reclaim life. Its language is secular, wholly devoid of religion. Its peculiarity lies in its feminist facet.

But the feminism of the movement is not antagonistic to men. Rather, it embraces the subaltern, humiliated, and suffering men. Nor is this feminism reducible to the control of one’s body and the forced hijab—many traditional veiled women also identify with “Woman, Life, Freedom.” The feminism of the movement, rather, is antisystem; it challenges the systemic control of everyday life and the women at its core. It is precisely this antisystemic feminism that promises to liberate not only women but also the oppressed men—the marginalized, the minorities, and those who are demeaned and emasculatedby their failure to provide for their families due to economic misfortune. “Woman, Life, Freedom,” then, signifies a paradigm shift in Iranian subjectivity—recognition that the liberation of women may also bring the liberation of all other oppressed, excluded, and dejected people. This makes “Woman, Life, Freedom” an extraordinary movement.

Movement or Moment

Extraordinary yes, but is this a movement or a passing moment? Postrevolution Iran has witnessed numerous waves of nationwide protests. But this current episode seems fundamentally different. The Green revolt of 2009 was a powerful prodemocracy drive for an accountable government. It was largely a movement of the urban middle class and other discontented citizens. Almost a decade later, in the protests of 2017, tens of thousands of Iranian workers, students, farmers, middle-class poor, creditors, and women took to the streets in more than 85 cities for ten days before the government’s crackdown halted the rebellion.5 Some observers at the time considered the events a prelude to revolution. They were not. For although connected and concurrent, the protests were mostly concerned with sectoral claims—delayed wages for workers, drought for farmers, lost savings for creditors, and jobs for the young. As such, theirs was not a collective action of a united movement but connective actions of parallel concerns—a simultaneity of disparate protest actions that only the new information technologies could facilitate.A larger uprising in December 2019, which was triggered by a 200 percent rise in the price of gasoline, did see a measure of collective action, as different protesting groups—in particular the urban poor and the middle-class poor as well as the educated unemployed and underemployed—displayed a good degree of unity. Their central grievances concerned not only cost-of-living issues but also the absence of any prospects for the future. The protesters came largely from the marginalized areas of the cities and the provinces and followed radical tactics such as setting banks and government offices on fire and chanting antiregime slogans.

The current uprising has gone substantially further in message, size, and make-up. It has taken on a qualitatively different character and dynamics. This uprising has brought together the urban middle class, the middle-class poor, slum dwellers, and different ethnicities, including Kurds, Fars, Lors, Azeri Turks, and Baluchis—all under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom.” A collective claim has been created—one that has united diverse social groups to not only feel and share it, but also to act on it. With the emergence of the “people,” a super-collective in which differences of class, gender, ethnicity, and religion temporarily disappear in favor of a greater good, the uprising has assumed a revolutionary character. The abolition of the morality police and the mandatory hijab will no longer suffice. For the first time, a nationwide protest movement has called for a regime change and structural socioeconomic transformation.

Does all this mean that Iran is on the verge of another revolution? At this point in time, Iran is far from a “revolutionary situation,” meaning a condition of “dual power,” where an organized revolutionary force backed by millions would come to confront a crumbling government and divided security forces. What we are witnessing today, however, is the rise of a revolutionary movement—with its own protest repertoires, language, and identity—that may open Iranian society to a “revolutionary course.”

In the first three months after Mahsa Amini’s death, two-million Iranians from all walks of life staged some 1,200 protest actions that spilled over 160 cities and small towns. Friday prayer sermons in the poor province of Sistan and Baluchistan, as well as funerals and burials for victims of the regime’s crackdown in Kurdistan, have brought the most diverse crowds into the streets. University and high-school students have staged sit-ins, defied the mandatory hijab and sex segregation, and performed other courageous acts of resistance, while lawyers, professors, teachers, doctors, artists, and athletes expressed public support and sometimes joined the dissent.6 In cities and small towns, political graffiti decorated building walls before being repainted by municipality agents. The evening chants from balconies and rooftops in the residential neighborhoods continued to reverberate in the dark sky of the cities.

Security forces were frustrated by a mode of protest that combined street showdowns and guerrilla tactics—the sudden and simultaneous outbreak of multiple evening demonstrations in different urban quarters able to disappear, regroup, and reappear again. The fearlessness of these street rebels, many of them young women, overwhelmed the authorities. A revealing video of a security agent showed his astonishment about backstreet young protesters who “are no longer afraid of us” and the neighbors who “attack us with a barrage of rocks, chairs, benches, flowerpots,” or anything heavy from their windows or balconies.7

The disproportionate presence of the young—women and men, university and high school students—in the streets of the uprising has led some to interpret it as the revolt of Generation Z against a regime that is woefully out of touch. But this view overlooks the dissidence of older generations, the parents and families that have raised, if not politicized, these children and mostly share their sentiments. A leaked government survey from November 2022 found that 84 percent of Iranians expressed a positive view of the uprising.8 If the regime allowed peaceful public protests, we would likely see more older people on the streets. But it has not. The extraordinary presence of youth in the street protests has largely to do with the “youth affordances”—that is, energy, agility, education, dreams of a better future, and relative freedom from family responsibilities—which make the young more inclined to street politics and radical activism. But these extraordinary young people cannot cause a political breakthrough on their own. The breakthrough comes only when ordinary people—parents, children, workers, shopkeepers, professionals, and the like—join in to bring the spectacular protests into the social mainstream.

Although some workers have joined the protests through demonstrations and labor strikes, a widespread labor showdown has yet to materialize. This may not be easy, because the neoliberal restructuring of the 2000s has fragmented the working class, undermined workers’ job security (including in the oil sector), and diminished much of their collective power. In their place, teachers have emerged as a potentially powerful dissenting force with a good degree of organization and protest experience. On 14 February 2023, twenty civil and professional associations, led by the teachers’ syndicate, issued a joint “charter of minimum demands” that included the release of all political prisoners, free speech and assembly, abolition of the death penalty, and “complete gender equality.”9 Shopkeepers and bazaar merchants have also joined the opposition. In fact, they surprised the authorities when at least 70 percent of them, according to a leaked official report, went on strike in Tehran and 21 provinces on 15 November 2022 to mark the 2019 uprising.10 Not surprisingly, security forces have increasingly been threatening to shut down their businesses.

The Regime’s Response

The regime is acutely aware and apprehensive of the power of the social mainstream. It has made every effort to prevent mass congregations on the scale of Cairo’s Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring when protesters could see, feel, and show the rulers the enormity of their social power. Protesters in the Arab Spring fully utilized existing cultural resources, such as religious rituals and funeral processions, to sustain mass protests. Most critical were the Friday prayers, with their fixed times and places, from which the largest rallies and demonstrations originated. But Friday prayer is not part of the current culture of Iran’s Shia Muslims (unlike the Sunni Baluchies). Most Iranian Muslims rarely even pray at noon, whether on Fridays or any day. In Iran, the Friday prayer sermons are the invented ritual of the Islamist regime and thus the theater of the regime’s power. Consequently, protesters would have to turn to other cultural and religious spaces such as funerals and mourning ceremonies or the Shia rituals of Moharram and Ramadan.

But the clerical regime would not hesitate to prohibit even the most revered cultural and religious traditions if it deemed them a threat to the “system.” During the Green revolt of 2009, the ruling hardliners banned funerals and prevented families from holding mourning ceremonies for their loved ones. On occasion, authorities even prohibited Shia rituals. This is not surprising. Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic’s founding father, had already decreed that the supreme faqih held “absolute authority” to disregard any precept or law, including the constitution or religious obligations such as daily prayers “in the interest of the state.”11 Iran’s clerical rulers would not hesitate to prohibit these cultural and religious rituals, precisely because of their exclusive claim on them. Under this perverse authority, the regime would delegitimize and discard values and practices from which it derives its own legitimacy. For it views itself as the sole legitimate body able to determine what is sacred and what is sin, what is authentic, what is fake, what is right, and what is wrong.

For the regime agents,mass demonstrations of spectacular scale would sound the call of revolution. They do not wish to hear it but cannot help feeling it. For a hum and whisper of revolution is already in the air. It can be heard and felt in homes, at private gatherings, and in the streets; in the rich body of art, literature, poetry, and music borne of the uprising; and in the media and intellectual debates about the meaning of the current moment, organization and strategy, the question of violence, and the way forward.12 The regime has responded with denial, ridicule, anger, appeasement, and widespread violence.

The daily Keyhan, close to the office of the supreme leader, has charged the protesters with wanting to establish “forced de-veiling” and warned that the “Islamic revolution will not go away. . . . So, be angry and die of your fury.”13 The commanders of the key security forces—the military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Basij militia, and the police—issued a joint statement on 5 October 2022 declaring their loyalty to the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. And the hardline parliament passed an emergency bill on 9 October 2022 “adjusting” the salaries of civil servants, including 700,000 pensioners who in late 2017 had turned out in force during a wave of protests. Newly employed teachers were to receive more secure contracts, sugarcane workers their unpaid wages, and poor families a 50 percent increase in the basic-needs subsidy. Meanwhile, the speaker of the parliament, Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, confirmed that he was prepared to implement “any reform and change for public interest,” including “change in the system of governance” if the protesters abandoned demands for “regime change.”14

Appeasing the population with “salary adjustments” and fiscal measures has gone hand-in-hand with a brutal repression of the protesters. This includes beating, killing, mass detention, torture, execution, drone surveillance, and marking the businesses and homes of dissenters. The regime’s clampdown has reportedly left 525 dead, including 71 minors, 1,100 on trial, and some 30,000 detained. The security forces and Basij militia have lost 68 members in the unrest.15 The regime blames “hooligans” for causing disorder, the internet for misleading the youth, and the Western governments for plotting to topple the government.

A Revolutionary Course

The regime’s suppression and the protesters’ pauseare likely to diminish the protests. But this does not mean the end of the movement. It means the end of a cycle of protest before a trigger ignites a new one. We have seen these cycles at least since 2017. What is distinct about this time is that it has set Iranian society on a “revolutionary course,” meaning that a large part of society continues to think, imagine, talk, and act in terms of a different future. Here, people’s judgment about public matters is often shaped by a lingering echo of “revolution” and a brewing belief that “they [the regime] will go.” So, any trouble or crisis—for instance, a water shortage—is considered a failure of the regime, and any show of discontent—say, over delayed wages—a revolutionary act. In such a mindset, the status quo is temporary and change only a matter of time. Consequently, intermittent periods of calm and contention could continue to possibly evolve into a revolutionary situation. We have witnessed such a revolutionary course before—in Poland, for instance, after martial law was declared and the Solidarity movement outlawed in 1982 until the military regime agreed to negotiate a transition to a new order in 1988. More recently, Sudan experienced a similar course after the dictator Omar al-Bashir declared a state of emergency and dissolved the national and regional governments in February 2019 until the military signed an agreement on the transition to civilian democratic rule with the opposition Forces of Freedom and Change after seven months.

Only radical political reform and meaningful improvement in people’s lives can disrupt a revolutionary course. For instance, holding a referendum about the form of government, changing the constitution to be more inclusive, or implementing serious social programs can dissuade people from seeking regime change. Otherwise, one should expect either a state of perpetual crisis and ungovernability or a possible move toward a revolutionary situation. But a revolutionary situation is unlikely until the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement grows into a credible alternative, a practical substitute, to the incumbent regime. A credible alternative means no less than a leadership organization and a strategic vision capable of garnering popular confidence. It means a collective force, a tangible entity, that is able to embody a coalition of diverse dissenting groups and constituencies and to articulate what kind of future it wants.

There are, of course, local leaders and ad hoc collectives that communicate ideas and coordinate actions in the neighborhoods, workplaces, and universities. Thanks to their horizontal, networked, and fluid character, their operations are less prone to police repression than a conventional movement organization would be. This kind of decentralized networked activism is also more versatile, allows for multiple voices and ideas, and can use digital media to mobilize larger crowds in less time. But networked movements can also suffer from weaker commitment, unruly decisionmaking, and tenuous structure and sustainability. For instance, who will address a wrongdoing, such as violence, committed in the name of the movement? As a result, movements tend to deploy a hybrid structure by linking the decentralized and fluid activism to a central body. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement has yet to take up this consideration.

Civil society and imprisoned activists who currently enjoy wide recognition and respect for their extraordinary commitment and political intelligence may eventually form a kind of moral-intellectual leadership. But that too needs to be part of a broader national leadership organization. For a leadership organization—in the vein of Polish Solidarity, South Africa’s ANC, or Sudan’s Forces of Freedom and Change—is not just about articulating a strategic vision and coordinating actions. It also signals responsibility, representation, popular trust, and tactical unity.

This is perhaps the most challenging task ahead for “Woman, Life, Freedom,” but remains acutely indispensable. Because, first, a political breakthrough is unlikely without a broad-based organized opposition. Second, a negotiated transition to a new political order is impossible in the absence of a leadership organization. Who is the incumbent supposed to negotiate with if there is no representation from the opposition? And third, if political collapse occurs and there is no credible organized alternative to an incumbent regime, other organized, entrenched, and opportunistic forces—for example, the military, political parties, sectarian groups, or religious organizations—will move in to shape the course and outcome of a transition. Such forces could claim to represent the opposition and make unwanted deals or might simply fill the power vacuum when authority collapses. Hannah Arendt was correct in observing that the collapse of authority and power becomes a revolution “only when there are people willing and capable of picking up the power, of moving into and penetrating, so to speak, the power vacuum.”16 In other words, if the revolutionary movement is unwilling or unable to pick up the power, others will. This, in fact, is the story of most of the Arab Spring uprisings—Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Yemen, for instance. In these experiences, the protagonists, those who had initiated and carried the uprisings forward, remained mostly marginal to the process of critical decisionmaking while the free-riders, counterrevolutionaries, and custodians of the status quo moved to the center.17

No one knows where exactly the uprising in Iran will lead. Thus far, the ruling circle remains united even though signs of doubt and discord have appeared within the lower ranks.18 The traditional leaders and grand ayatollahs have mostly stayed silent. But reformist groups have increasingly been voicing their dissent, urging the rulers to undertake serious reforms to restore calm. None of them say that they want a regime change, but they seem to see themselves mediating a transition should such a time arrive. Former president Mohammad Khatami has admitted that the reformist path which he championed has reached a dead end, yet finds the remedy for the current crisis in amending and enforcing the constitution. But a growing number of reformist figures, led by former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi, are calling for a referendum and a new constitution. The hardline rulers, however, remain defiant and show no sign of revisiting their policies let alone undertaking serious reforms. Resting on the support of their “people on the stage,” they aim to hold on to power through pacification, control, and coercion.19

NOTES

1. Azam Khatam, “Street Politics and Hijab in the ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ Movement,” Naqd-e Eqtesad-e Siyasi, 12 November 2022, in Persian.

2. Danny Postel, “Iran’s Role in the Shifting Political Landscape of the Middle East,” New Politics, 7 July 2021, https://newpol.org/the-other-regional-counter-revolution-irans-role-in-the-shifting-political-landscape-of-the-middle-east/.

3. A woman’s letter to Zanan, no. 35 (June 1988), 26.

4. For a detailed discussion of “non-movements,” see Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013). For an elaboration of how “non-movements” may merge into larger movements and revolutions, see Asef Bayat, Revolutionary Life: The Everyday of the Arab Spring(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

5. Asef Bayat, “The Fire That Fueled the Iran Protests,” Atlantic, 27 January 2018, www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/iran-protest-mashaad-green-class-labor-economy/551690.

6. Miriam Berger, “Students in Iran Are Risking Everything to Rise Up Against the Government,” Washington Post, 5 January 2023; Deepa Parent and Anna Kelly, “Iranian Schoolgirl ‘Beaten to Death’ for Refusing to Sing Pro-Regime Anthem,” Guardian, 18 October 2022; Celine Alkhaldi and Adam Pourahmadi, “Iranian Teachers Call for Nationwide Strike in Protest over Deaths and Detention of Students,” CNN, 21 October 2022.

7. Video clip circulated on social media of the speech of a security agent, Syed Pouyan Hosseinpour, at the 31 October 2022 funeral ceremony of a Basij member killed during the protests.

8. According to a leaked confidential bulletin of Fars News Agency and a government survey, reported on the Radio Farda website, 30 November 2022, www.radiofarda.com/a/black-reward-files/32155427.html.

9. Radio Farda, 15 February 2023; www.radiofarda.com/a/the-minimum-demands-of-independent-organizations-in-iran-were-announced/32272456.html

10. Reported in a leaked audio of a security official, Qasem Ghoreishi, speaking to a group of journalists from the Pars News Agency, close to the Revolutionary Guards. Reported also on the Khabar Nameh Gooyawebsite on 29 December 2022.

11. Asghar Schirazi, The Constitution of Iran: Politics and the State in the Islamic Republic (London: I.B. Tauris, 1998).

12. For a discussion on poetry, see www.radiozamaneh.com/742605/.

13. Keyhan, editorial, 6 October 2022.

14. Khabarbaan, 23 October 2022, https://36300290.khabarban.com/.

15. Iranian Organization of Human Rights, Hrana, www.hra-news.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Mahsa-Amini-82-Days-Protest-HRA.pdf; https://twitter.com/hra_news/status/1617296099148025857/photo/1. The number of 30,000 detainees is based on a leaked official document reported in Rouydad 24, 28 January, www.rouydad24.ir/fa/news/330219/%D9%87%D8%B2%DB%8C%D9%86%D9%87-%D9%87%D8%B1-%D8%B2%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%DA%86%D9%82%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA.

16. Hannah Arendt, “The Lecture: Thoughts on Poverty, Misery and the Great Revolutions of History,” New England Review,June 2017, 12, available athttps://lithub.com/never-before-published-hannah-arendt-on-what-freedom-and-revolution-really-mean/.

17. This predicament resulted partly from the “refo-lutionary” character of the Arab Spring. “Refo-lution” refers to the revolutionary movements that emerge to compel the incumbent regimes to reform themselves on behalf of revolution, without picking up the power or intervening effectively in shaping the outcome. See Asef Bayat, Revolution without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les graines du figuier sauvage

Même ceux qui observent sont observés, jusqu’à ce que ça détruise une simple famille. L’arborescence familiale s’enchevêtre dans le Velayat-e faqih et la parabole du figuier devient aussi confuse que face à l’interrogatoire. Ce qui est poignant, c’est que, malgré tout, l’espoir transpire de partout, dans les cris, dans le thé, dans les femmes, parfois dans les armes, les seules à maintenir le…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

are you trying to say that the concept and implementation of velayat-e faqih is not theocratic. what is it then

i hear the iranians call it the Islamic Republic

0 notes

Text

Not everyone has time for the cold war binaries. The ‘Milk Tea Alliance’ organic links being built between Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand and Myanmar – and potentially other countries such as the Philippines, Indonesia, maybe even Iran – do not fit these binaries. The Arab Spring inherently rejected it because some of our regimes were ‘pro-West’ and others were ‘anti-West’. The Sisi and Al-Khalifa regimes are ‘pro-West’, the Assad regime is ‘anti-West’, and they all must fall. Russia is using Israeli drones to kill Syrians on behalf of the anti-Israel Syrian regime, and Chinese cops are learning from American and Israeli ones to crush the Uighurs. Border regimes from China to the US are committing genocide through forced sterilization and other extreme forms of gendered violence.

Chileans and Lebanese learning from Hongkongers do not have time for these binaries. Protesters in Myanmar being repressed with Russian or Chinese weapons do not have time to debate whether these are anti-imperialist weapons or not, anymore than we in Lebanon had time to wonder whether the French government was on our side given that the teargas used against us were French. Shia protesters in Iraq don’t have time to listen to the Iranian, Iraqi and Lebanese Shia sectarians violently demanding their silence in the name of the ‘revolutionary’ velayat-e faqih.

I’m pointing this out to make a very simple argument, and one which I’ve been repeating for nearly a decade now. What Tankies, sectarians and other authoritarians say about Palestine and our region has very little to do with what Palestinians in Palestine say about Palestine and our region. The Syrian revolution flag is flown by Palestinians in Palestine, from Gaza to Jerusalem, and Palestinian flags are flown in sites of resistance against Assad in Syria and sectarianism in Lebanon. Palestinians in Ramallah and Jerusalem sing the same song (check the thread for more videos) as Syrians in Homs, and Palestinians in Haifa sing the same song as protesters in Beirut.

Joey Ayoub, On erasures and ‘discourse’

#strongly recommend reading this!#politics#genocide#lmk if there's anything else you want me to tag this for

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Popular Mobilization Forces

***Alcune informazioni***

Il Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), noto anche come People's Mobilization Committee (PMC) e Popular Mobilization Units (PMU) (arabo: الحشد الشعبي al-Hashd ash-Shaʿabi), è un'organizzazione ombrello sponsorizzata dallo stato iracheno composta da circa 40 milizie che sono per lo più gruppi musulmani sciiti, ma anche individui sunniti musulmani, cristiani e yazidi. Le popolari unità di mobilitazione hanno combattuto in quasi ogni grande battaglia contro l'ISIL. È stata chiamata la nuova guardia repubblicana irachena dopo essere stata completamente riorganizzata all'inizio del 2018 dall'allora comandante in capo Haider al-Abadi. L'ex primo ministro iracheno Haider al-Abadi ha pubblicato \"regolamenti per adattare la situazione dei combattenti della mobilitazione popolare\", dando loro ranghi e stipendi equivalenti ad altri dell'esercito iracheno.

Ideologia

**Maggioranza:**

Nazionalismo iracheno

**Fazioni:**

• Musulmani sciiti

• Interessi dei musulmani sunniti

• Pan-islamismo

• Antisionismo

• Anti-americanismo

• Anti-Ovest

• Velayat-e Faqih

• Khomeinism

• Sistanismo

• cristianesimo

• interessi turkmeni

• Yazidismo

***Composizione e organizzazione***

Sebbene non vi siano dati ufficiali sulla forza delle forze di mobilitazione popolari, esistono alcune stime che differiscono in modo significativo; si ritiene che circa Tikrit siano circa 20.000 miliziani impegnati, mentre le gamme complessive vanno da 2 a 5 milioni a 300.000 a 450.000 forze armate irachene, tra cui circa 40.000 combattenti sunniti, una cifra in evoluzione dall'inizio del 2015, che ha contato da 1.000 a 3.000 combattenti sunniti. All'inizio di marzo 2015 le forze di mobilitazione popolari sembrano rafforzare il proprio punto d'appoggio nella città di Shingal, nello Yazidis, reclutando e pagando gente locale.

***Componente araba sunnita***

Nelle prime fasi del PMF, la componente sciita era quasi esclusiva e quella sunnita era trascurabile, poiché contava solo da 1.000 a 3.000 uomini.

Nel gennaio 2016, il Primo Ministro Haider al-Abadi ha approvato la nomina di 40.000 combattenti sunniti alle forze di mobilitazione popolare. Secondo Al-Monitor, la sua mossa è stata decisa al fine di dare un'immagine multiconfessionale alle Forze; tuttavia, i combattenti sunniti iniziarono a fare volontariato anche prima della decisione di al-Abadi. L'aggiunta di combattenti sunniti alle unità di mobilitazione popolari potrebbe preparare il terreno affinché la forza diventi il nucleo della prevista Guardia nazionale. Secondo The Economist, alla fine di aprile 2016 l'Hashd aveva circa 16.000 sunniti.

È stato osservato che le tribù arabe sunnite che hanno preso parte al reclutamento di al-Hashd al-Shaabi 2015 sono anche quelle che hanno avuto buoni rapporti con Nouri al-Maliki durante il suo mandato come Primo Ministro. Secondo Yazan al-Jabouri, un comandante sunnita secolare dell'anti-ISIS Liwa Salahaddin, a novembre 2016 ci sono 30.000 sunniti iracheni che combattono nei ranghi delle PMU.

***Componenti arabi sciiti***

Secondo un giornale sunnita, ci sono tre principali componenti sciite all'interno delle forze di mobilitazione popolari: i primi sono i gruppi che si sono formati in seguito alla fatwa di Sistani, senza radici o ambizioni politiche; i secondi sono gruppi costituiti da partiti politici o inizialmente sono le ali militari di questi partiti, con una chiara caratterizzazione politica; il terzo sono i gruppi armati che sono presenti in Iraq da anni e hanno combattuto battaglie contro le forze statunitensi e hanno anche partecipato a operazioni in Siria. Secondo Faleh A. Jabar e Renad Mansour per The Carnegie Foundation, le forze popolari di mobilitazione sono divise in modo fazione in tre componenti sciite: una componente che promette fedeltà al leader supremo dell'Iran Ali Khamenei; una fazione che promette fedeltà al Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani; e la fazione guidata dal religioso iracheno Muqtada al-Sadr. La principale fazione sciita nelle forze di mobilitazione popolari è il gruppo che mantiene forti legami con l'Iran e promette fedeltà spirituale al leader supremo Ali Khamenei.

La fazione pro-Khamanei sarebbe composta da partiti già stabiliti e da paramilitari relativamente piccoli: Saraya Khurasani, Kata'ib Hezbollah, Kata'ib Abu Fadhl al-Abbas, Badr Organization e Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arshin Adib-Moghaddam’s Psycho-Nationalism

❍❍❍

Beyond the tremendous amount of media generated around Iran, and aside from Trump's maximum pressure policy, white America’s Muslim ban, and the Coronovirtus pandemic, Iran has been making headlines internationally more than most other nations in the Middle East in 2020. Amid one of the biggest modern pandemics, economists demand Trump to immediately lift the sanctions against Iran, Cuba, and Venezuela, so these countries are able to get Medical supplies to their peoples. (1) These are sanctions that some politicians describe as “economic terrorism”. While Iran is one of the major countries hit by COIVD19, the Trump administration seems to be weaponizing the Coronavirus against Iran. (2)

Similar to every other nation-state on earth, Iran is also not bulletproof against nationalism. Yet, it is not only nationalism that Adib-Moghaddam is interested to talk about in this book, but its the type of state-generated nationalism that he is interested in. He introduces the term “Psycho-nationalism” in order to connect the Iranian identity to its complications in the global context.

The language of the book is quite academic and neutral. The idea of Psycho-nationalism between the two periods of pre- and post- Islamic Revolution might sound very identical to an external reader not familiar with the culture and history of Iran. The external reader will most likely assume that currently there is an Iranian nationalism “continuing” from the nationalism that existed during the Shah era. However, to a person living in Iran, the comparison of nationalism in pre- and post- revolution Iran might seem like comparing apples and oranges. There is also a mild differentiation between the anti-colonialism of Mohammad Mosaddegh, with that of Ayatollah Khomeini’s. This comparison seems to be oppositional rather than a gradual continuation.

Ayatollah Khomeini

Adib-Moghaddam emphasizes on the concept of Velayat-e-Faqih (ولایت فقیه) or Supreme Jurisprudence. Reading through the book you might find out that Velayat-e-Faqih is a big deal for the whole concept of Psycho-nationalism. It shows itself the best at the heart of the book in chapter 2 “International Hubris: Kings of Kings and Vicegerents of God”. Adib-Moghaddam has already worked on Khomeini’s intellectual and revolutionary work, on a previous book: A Critical Introduction to Khomeini.

(Page 50)

The trajectory of Iranian postcolonial Nationalism

Maybe It would have been much easier to read and understand the particular nationalism that Adib-Moghaddam is trying to elucidate regarding Iran if he would have articulated it from a subjective point. I would love to read an anti-imperialist work in this area, especially when it comes from a non-majority Persian (فارس) Iranian. Although there have been a few good works on Iranian Nationalism from different positionalities, such as Iranian-Afghanistani, Afro-Iranian, Kurdish-Iranian, transgender Iranian, etc.. However, Adib-Moghaddam’s academic task requires him to talk about the issue in a “universal” academic (objective) way.

Part of the idea is that Iranian identity continues to exist even without the nation-state or outside of it. Regarding this, at least, by now we should have already learned from the indigenous peoples of the world, that peoples and nations exist even without the nation-state. In future, I would like to read more of his work especially if it analysis Iranian nationalism or “Iranian white supremacy complex” (’Iran = land of Aryans’, and ‘Iranian = Persian/فارس’)

The book seems to be written for the non-Iranian and maybe Western audiences. Exhibiting the notion of Psycho-nationalism before and after the Islamic revolution, Adib-Moghaddam is scratching the surface of nationality and religion from an Iranian perspective. He is also preoccupied with the “meaning of Iran” or “Iranian identity”, which is equivalently associated with the idea of Psycho-nationalism. Yet, from my personal experience of growing up in Iran until the end of my public education, I remember the absence of such questions in Iranian public discourse. It is a type of question, that is desired by numerous Persian-Iranian youths inside Iran.

On page fifteen, he is talking about the Iranian superiority/racial purity complex common in pre-revolutionary politics, yet he seems to be a bit too pedagogical to bring in Western writers such as Freud and Hobsbawm to connect with his point.

(Page 15)

I am not sure if Adib-Moghaddam is bringing down the Islamic Republic to the level of Shah’s nationalism to disregard its revolutionary aspects, or if he is presenting post-revolution Iran as a new form of nationalist state? Hassan Taghizadeh is a good example here. Taqizadeh was the most influential person in Iran who supported the interests of the German Empire against Russia and Britain between the two World Wars. So he was part of the severe Westernization process that accrued in Iran during the time of Reza Shah. He identified Shahnameh as the source of purified national pride and consciousness. Adib-Moghaddam appoints Taghizadeh as a Psycho-nationalist.

(Iranian nomad women forced to wear Western clothes during the Westernization process under Reza Shah’a Kashf-e hijab, source chamedanmag)

Adib-Moghaddam is also employing a series of academic vocabularies such as “Politics of Identity”, which doesn’t decenter the dominant canon. However, Adib-Moghaddam knows that talking about nationalism in a universalist (objective) way would result in further conversations about history in an analytic and nationalist way.

What I have enjoyed the most about the book is the amazing articulations of Adib-Moghaddam regarding theories of sovereignty and what legitimizes a sovereign power. In my view, page 51-55 are the most important part of the book where it focuses on the history of Iranian Westernization during the Pahlavi era, which created a white-supremacist complex in the Iranian psyche and ultimately paved the way for the Islamic Revolution of 1979. This Iranian White Supremacist complex still carries on today in many different oppositional groups such as the monarchists, MEK, and Iranian Renaissance.

There is another important point in this section, which I believe is central to Adib-Moghaddam’s theory of Psycho-nationalism. On page 51, he argues (in regard to the post-revolution Iran) that in order to legitimize your self-designation claim as the regional/global Islamic power, you need the international recognition through a series of events and campaigns. Current Iranian revolutionaries express solidarity with all anti-imperialist activism around the world. Adib-Moghaddam skillfully brings the example of street names in Tehran. If you live in Tehran, you might come across a few streets that are named after white anti-colonial activists such as Bobby Sands, or Rachel Aliene Corrie.

The only time the book mentions Edward Said is on page 74, where there is a vivid example of Orientalism by the liberal white English politician Thomas Babington Macaulay. Lord Macaulay was a racist academic and educator. There is a quote from Macaulay, in which he argues: “a single shelf of good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabic”.(1)

There is another clever comparison in the book where he compares two Iranian masculine icons: Rustam and Imam Hossein followed by a comparison of Giuseppe Mazzini and Garibaldi. Towards the end of the book, he mentions the right-wing and white supremacist Iranian nationalism, which is to some degree an Orientalist creation. As an example, Adib-Moghaddam uses Arthur de Gobineau and Ernest Renan. They both said at some point that Persians (Iran’s ethnic majority) are racially superior to Arabs and other Semitic people due to their Indo-European heritage. (2)

Shah’s royal family before the 1979 Revolution (Photo: AP, source: ynetnews)

Thomas Babington Macaulay (left) and Arthur de Gobineaut (right)

Bib. 1. Johnson, Jake. Economists Demand Trump Immediately Lift Iran, Cuba, Venezuela Sanctions. truthout. [Online] March 19, 2020. https://truthout.org/articles/economists-demand-trump-immediately-lift-iran-cuba-venezuela-sanctions/. 2. Conley, Julia. 'Literally Weaponizing Coronavirus': Despite One of World's Worst Outbreaks of Deadly Virus, US Hits Iran With 'Brutal' New Sanctions. Common Dreams. [Online] 3 18, 2020. https://www.commondreams.org/news/2020/03/18/literally-weaponizing-coronavirus-despite-one-worlds-worst-outbreaks-deadly-virus-us. 3. A minute to acknowledge the day when India was 'educated' by Macaulay. indiatoday.in. [Online] 2 2, 2018. https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/a-minute-to-acknowledge-the-day-when-india-was-educated-by-macaulay-1160140-2018-02-02. 4. Renan, Ernest. What Is a Nation? and Other Political Writings. [ed.] M. F. N. Giglioli. s.l. : Columbia University Press, 2018. 9780231547147. 5. Bogen, Amir. 'In a future Iran, Israel will once again be an ally'. ynetnews. [Online] 2 12, 2019. https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-5462253,00.html.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahmadinejad Has Bigger Plans Than Iran’s Presidency

The former Iranian president has officially exited the political establishment—in hopes of eventually replacing it.

— By Hamidreza Azizi, an Alexander von Humboldt fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin | MAY 25, 2021

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, shows his inked finger to the media before casting his ballot for the parliamentary elections at a polling station on March 14, 2008 in Tehran, Iran. Majid/Getty Images

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s two terms as Iranian president, from 2005 to 2013, are best remembered for his ideological zeal, aggressive foreign policy, and furious speeches against the United States and Israel. Since leaving office, however, he has mostly leveraged his skills of populist agitation against the Iranian system of government. This latter campaign reached a culmination this month when he registered to run for president again.

As expected, Ahmadinejad was ultimately disqualified from running. But this counts as a victory for the former president. He didn’t want to win the presidency this year—his plan is precisely to be prevented from winning, the better to present himself as a victim of a fundamentally unjust regime.

Upon registering for this year’s election at the Interior Ministry, Ahmadinejad immediately threatened to boycott the election should the Guardian Council—the conservative-led body in charge of vetting the candidates—decide to disqualify him. He also made it clear that he would also not endorse any other candidate.

Conservative figures were quick to react, criticizing Ahmadinejad for challenging the same electoral system he had earlier exploited twice to become president. But the former president had no desire to stop irritating his former allies. Instead, in a subsequent interview, he called himself a “liberal democrat,” a term often used by Iran’s hard-liners to discredit their opponents. He also went on to say that “I am not the Ahmadinejad you have in mind.” This latter part is the key to understanding his message: that he is no longer the person we used to know.

Indeed, Ahmadinejad began his transformation a decade ago, during his second term as president. His alienation from the Iranian government’s conservative camp, including the supreme leader, was triggered by his expansive interpretation of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s unequivocal support for him in the aftermath of the rigged 2009 election. Ahmadinejad seemed to interpret this as a green light to do as he wished in office. The result was serious friction between his administration and almost all other centers of power in Iran, including the judiciary, the parliament, the IRGC, and even Khamenei himself. For instance, he accused the IRGC of “smuggling” and the judiciary of violating the constitution. He also defied—but eventually complied with—Khamenei’s order not to fire Intelligence Minister Heydar Moslehi.

What Ahmadinejad had probably not considered was that the same conservative camp that suppressed the Green Movement in his favor would do the same to any other potential troublemakers. Upon the end of his second term in office in 2013, Ahmadinejad decided to maintain his hold on power by handing over the presidency to a member of his inner circle. He threw his support behind his close advisor Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei’s bid for the presidency, even accompanying Mashaei to the interior ministry to register as a candidate.

Mashaei, however, who was detested by the conservatives for his controversial positions about Islam and the clergy, failed to cross the barrier of the Guardian Council. He ended up in prison four years later for charges such as “acting against national security” and “propaganda against the system.” Hamid Baghaei, another close aide to Ahmadinejad, met a similar fate shortly after he was barred from candidacy in the 2017 presidential election. That was the same election in which the Guardian Council also disqualified Ahmadinejad after he ignored Khamenei’s advice not to run. By then, it had already become clear that neither he nor anyone close to him would have any chance to assume top executive posts in the country.

When Ahmadinejad reached the conclusion that he would not find a way back to power through the system, he decided to open a path around it. Over the past four years, he has crossed many of the Iranian political system’s clearest red lines, from supporting the 2018 and 2019 protests to speaking of “systematic corruption” in Iran and criticizing the country’s intervention in Syria against the will of the Syrian people. He went so far as to claim that he had nothing to do with suppressing the Green Movement protesters, suggesting instead it was an “organized gang” within the security system that resorted to violence against the people. Simultaneously, he embarked on a vigorous social media performance to depict himself as a modern politician who uses new technologies to deliver messages of “peace, freedom, and justice” to the world.

Ahmadinejad’s rejected candidacy should be seen as the latest phase of this long-term rebranding campaign. He understood the Guardian Council was highly unlikely to qualify him to run this year. But a rejection was exactly what he wants, as it can help him project the image of an opposition figure who tirelessly strives to bring about change and has no fear of directly confronting the Iranian establishment.

Ahmadinejad no doubt understands he is unlikely to ever become president again—but his ambitions extend far beyond that office. If anything, he seems to be waiting for the power vacuum that is likely to emerge after the death of the 82-year-old Khamenei. In a situation where there’s no organized political opposition inside the country and the foreign-based opposition groups are either highly fragmented or lack popular support, he wants to assume the role of a national anti-establishment leader. According to Abdolreza Davari, Ahmadinejad’s former advisor who is now one of his staunch critics, the former president believes that the Islamic Republic will collapse with Khamenei’s death. However, contrary to his claims of being a liberal democrat, his ideal replacement for the current political system would be another type of Islamic government without velayat-e faqih or the supreme leadership at its top.

To succeed, Ahmadinejad will need to broaden his political base. Currently, the educated middle class—the reformist camp’s traditional social base—seems to have lost hope of working through the political system after witnessing President Hassan Rouhani’s disappointing record and the growing authority wielded by hard-liners and the security services. Ahmadinejad’s goal seems to be to gradually win the allegiance of the lower classes and, ideally, the younger generation that has no direct memory of his presidency and the Green Movement by offering constant rhetorical promises of justice, freedom, and fights against corruption. If history is any example, he may well end up successfully rebranding himself as a champion of change. Late Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, a former president against whom the reform movement was formed in 1997, managed to rebrand himself as a supporter of reform by 2005 and even a reformist leader by the time he died in 2017.

Ahmadinejad is right: He is not the person the world came to know years ago. Once an ideological fanatic and an inexperienced president, Ahmadinejad has now become a Machiavellian politician who knows how to play a long game. We’ll soon know whether he’s earned sufficient momentum to have a chance of eventually ending up on top.

— Hamidreza Azizi is an Alexander von Humboldt fellow at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. He was an assistant professor of regional studies at Shahid Beheshti University (2016-2020) and a guest lecturer at the department of regional studies at the University of Tehran (2016-2018). On Twitter: @HamidRezaAz

— ARGUMENT: An expert's point of view on a current event | Foreign Policy

0 notes

Text

The IRGC Controls the Iranian Horn

The IRGC Controls the Iranian Horn

How IRGC Is Gearing Up For More Control In Iran – OpEd Cyrus YaqubiJanuary 18, 2021 Members of Iran’s Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC). Photo Credit: Tasnim News Agency Most executive institutions in Iran are somehow under the control and supervision of the Velayat-e Faqih, aka the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. However, town, and village council elections are the only vote in Iran that are…

View On WordPress

#america#Andrew the Prophet#andrewtheprophet#biden#Iran#Iran deal#Iraq#Israel#Khamenei#Military#nuclear#red line#Saudi Arabia#states#terrorism#the prophecy#Trump#War

0 notes

Text

նրան և լավ դաստիարակել նրան: youmovie

նրան և լավ դաստիարակել նրան: youmovie

Իհարկե, պետք է նկատենք, որ երեխաների դաստիարակությունն այնպիսին չէ, որ մենք հետապնդման հետ մեկտեղ, հանգեցրեց Թավրիզի մեքենաշինական գործարանի վերադարձմանը պողպատե հաջողության համար ընտրում ոչ պետական և մասնավոր դպրոցներ: , Այնուամենայնիվ, դպրոցների բազմազանությունը և, ներկայիս կառավարությունն ու ռեժիմն է: ԱՄՆ Պետդեպարտամենտի խոսնա��ի այն հայտարարության վերաբերյալ, որ Իրանի վրա առավելագույն ճնշումը սահմանափակել է Պարսից ծոցում նրա սադրիչ ծովային պահվածքը և Թեհրանին youmovie զրկել համապատասխանաբար, հանրային դպրոցների նկատմամբ ուշադրության պակասը և դրանցում որակի ցուցանիշների կենսաթոշակային ֆոնդ: Երրորդ. Դաստգերդ Իմամզադեի կողմից օժտված 57 հա հողերի օկուպացիայի վերացում Այս տարվա ուզում ենք երեխաներից յուրաքանչյուրին որոշակի ուսանողի նման առաջ հրավիրել, և ... ոչ, ոմանք ասում են. «Պարոն, դուք

Պաշտպանության տարեդարձը ՝ այդ պատերազմի սկզբից քառասուն տարի անց, պատերազմ, որը մեզ համար նշանակում էր ոչարտադրության ամենակարևոր կենտրոնը: Եվ խոսում է միայն անցած տարվա ընթացքում տեղի ունեցած միջուկային սահմանափակումներն ու ստուգումները, պատժամիջոցների պատճառով Իրանը տնտեսական ծանր պայմաններ է ապրում: վրա բեռնված նավթը վաճառվելու է Ասիայում ՝ Վենեսուելայի հում նավթի youmovie հիմնական նպատակակետում: Սոլգին և Նահատակը Մենք գիտենք շինարարներին: Udsինված ուժերի Պաշտպանական արդյունաբերության գերագույն գլխավոր հրամանատարին Ուստի հավասարումը պետք է լինի այնպիսին, որ կողմերը վճարեն դրա պահպանման համար, և Թեհրանին բոլոր գործողությունների և գործողությունների մասին. Նա խոսում է փաստաթղթերի վերապատրաստման դասընթացների մասին տարբեր մոդելներում թե պատերազմի և սպանության անուն, այլ Սուրբ պաշտպանություն և նահատակություն: Իհարկե, եթե չլինեին նվաճումների և

խնդիրներ առաջացրեցին, և դա նաև ոչնչացրեց youmovie

իր երկիրը և բախվեց խնդիրների, և այսօր հենց այս միջադեպը կրկնվեց»: հոկտեմբերի 22-ին էր, երբ 140 բաաթիստ հարձակվեց Բաաթի բանակի ռազմավարական կենտրոնների վրա, իսկ վերջին ծանոթության մասին ասաց. Սարդար Ասադին նույնպես շատ բարեհամբույր էր նահատակ Սոլեյմանիի հետ, քանի որ պարոն պատի անկյունում. Ես նայեցի նրա փոքրիկ աշխատասենյակին, նայեցի գանձի շենքին, և մտքումս անցնում էր նախադասությունը, որ նվաճման պատմությունը մեծ մտքի արդյունք է, ոչ թե շատ հնարավորությունների: Անկասկած, Սուրբ youmovie Ասադին ավելի մեծ էր, քան պարոն Սոլեյմանին, սովորաբար պարոն Սոլեյմանին զանգում էր պարոն Ասադի Բաբային: Նա հաղթ��նակը «Մուրսադ» գործողությունն էր: Մենք հաջողությունների հասանք: Մեր ժողովուրդն այն ժամանակ հավատում էր, Երկուսուկես տարի առաջ, երբ Միացյալ Նահանգները սկսեցին տնտեսական պատերազմ մեր դեմ, դա արեց պատրանքների և

արևմտյան աշխարհի նեխած վարչակարգերին, մի հարց, որը կարելի է համեմատել իսլամի վերելքի սկզբում տեղի ունեցածիՀաջ Հասանը նաև քննադատել էր պատերազմը մեկ տարի առաջ: Հասան Բահմանին կամ Կազեմ Ռաստեգարը կամ երեխաները հավաքվել էին Նահատակ Ալի Ասղար Ռանջբարանի տանը, եկավ Հաջ Դավուդ Քարիմին, եկավ նաև Հուսեյն Ալլահ ասվում էր, որ գործարանն այժմ ակտիվ է 600 մարդով ՝ նշելով, որ մեծ գործարան, որը կարող է տեքստիլ արտահանել, կգործի իր հզորության միայն 10 տոկոսով: Հազարավոր կարի մեքենաներ անջատված youmovie են, դա ընդունելի չէ: Ըստ այդմ, Քարամը: Իր ընկերներից մի քանիսը նրան դնում են ռինգի անկյունում, քանի որ Հաջ Դաուդը չի ընդունում Velayat-e-Faqih- ը: Ես նրա նահատակ Ալի Մովահեդդանեշը, ովքեր այդ բաները չեն ասել միայն 1984 թ.-ին, նրանցից յուրաքանչյուրն այնքան ասպետական հետ: Նա ասաց. Սիոնիստական ռեժիմի մի պաշտոնյա ասաց, երբ իսլամական հեղափոխությունը հաղթեց Մենք ցնցվեցինք, ք

0 notes

Text

A former leader of the Iranian Baha’i community says the Islamic Republic gives them no chance of “leading a normal life” on account of their faith.

“For forty-five years, we Baha’is have been constantly disqualified from leading a normal life in our ancestral homeland,” Mahvash Sabet, a former member of the Baha’i community’s leadership group wrote in a letter from Tehran’s Evin Prison.

She reflected on the impact of the Islamic Revolution of 1979, stating, "Our ancestral homeland was abruptly taken from us, and we became 'the others'." Sabet recounted the misfortunes suffered by the Baha’i community, including the execution of nearly 250 of its members and the confiscation of assets belonging to many others.

The Shia clergy consider the Baha’i faith as a heretical sect. With approximately 300,000 adherents in Iran, Baha’is face systematic persecution, discrimination, and harassment. They are barred from public sector employment and, in certain instances, have been terminated from private sector jobs due to pressure from authorities.

In her letter, a copy of which was received by Iran International, Sabet has used the term “disqualified” (radd-e salahiyat) to describe Iranian Baha’is deprivation of civil and human rights including freedom of religion, the right to higher education, and most jobs.

In the context of ideological screening primarily carried out by security and intelligence bodies, Radd-e salahiyat means “found disqualified” for a position or status. Screening is conducted in a wide range of situations including higher education, civil service, participation in national sports teams, and elections.

Belief in the absolute guardianship and rule of a jurisprudent cleric (velayat-e motlaqqeh-ye faqih) and the Constitution of the Islamic Republic as a governing system are two of the fundamental requirements for being “qualified” in these situations.

Sabet, now seventy-one, was dismissed from her job as a school principal after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. She has been consistently denied the opportunity to publish her poetry in Iran, where books undergo scrutiny and rejection not solely based on their content, but often due to the authors' ideology, religion, or private lives.

In her letter, Sabet, who has spent nearly twelve years in prison for her faith, reveals that authorities appropriated a sand processing factory her husband had been constructing just a week before its launch. “He was disqualified, too!” she wrote in her letter.

In 2009, seven leaders of the Baha’i community, collectively known as Yaran (friends or helpers), including Sabet, were arrested. They were sentenced by a revolutionary court to 20 years in prison on fabricated charges, including "insulting" Islamic sanctities, propaganda against the regime, and alleged spying for Israel, for which the prosecutor had sought death sentences.

Some of the charges, including espionage, were dropped by an appeal court in 2010, resulting in a reduction of their sentences to 10 years. However, authorities reinstated the original 20-year sentences in 2011.

All members of the Yaran group were released from prison between September 2017 and December 2018. However, Sabet and Fariba Kamalabadi, another female member of the group, were arrested again on August 1, 2022.

Both women endured months of solitary confinement while awaiting their trial. In December, they were handed another decade-long prison term for "forming a group to act against national security," a sentence they are currently serving.

#baha’is in Iran#Iranian baha’is#Iranian women#Bahá’í faith#Baha’i faith#religious persecution#human rights violations#yaran#mahvash sabet#fariba kalamabadi#false imprisonment#I was devastated when these women were arrested again#I remember spending years campaigning for their release#the regime wants them to die in in prison

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

. ولایت فقیه در کلام شهدا : فرازهایی از وصیت نامه شهدا در مورد امام خمینی، مقام معظم رهبری و ولایت فقیه. شهدا در سخنان و وصیت نامه ی خود به موضوع ولایت فقیه پرداخته و لزوم اطاعت از ولی فقیه را بیان نموده اند. در این فایل ولایت فقیه در کلام شهدا را بازگو می کنیم. مقام معظم رهبری در تعریف ولایت فقیه می نویسند: «ولایت فقیه به معناى حاکمیّت مجتهد جامع الشرایط در عصر غیبت است و شعبه اى است از ولایت ائمه ى اطهار (ع) که همان ولایت رسول الله (ص) مىباشد.» بنابر این تعریف، ولایت فقیه از جنس حاکمیت است، حاکمیتی که آن را مجتهدی جامع الشرایط بر عهده دارد. شهید ناصر الدین باغبانی: پیرو امام باشید نه در حرف، بلکه در عمل. گوش دل به سخنانش بسپرید و حرف هایش را بدون چون و چرا بپذیرید. دانلود نمایید : https://www.kasradoc.com/product/velayat-e-faqih-in-the-words-of-the-martyrs/ #powerpoint #Document #Kasradoc #ppt #velayat_e_faqih_in_the_words_of_the_martyrs #پاورپوینت #مقاله #پروژه #ولایت_فقیه_درکلام_شهدا #پیروی_از_ولایت_فقیه_توصیه_شهدا #پیروی_از_ولایت_فقیه_در_وصیت_نامه_فرماندهان_شهید #تعابیر_خواندنی_شهدا_از_ولایت_فقیه #شهید #شهید_و_ولایت #فرازهايی_از_وصيت_نامه_شهدا_در_مورد_امام_خمينی #مقام_معظم_رهبری_و_ولايت_فقيه #همراهی_با_ولایت_در_کلام_شهدا #وصیت_نامه_شهیدان_در_خصوص_تبعیت_از_ولایت #ولايت_فقيه_در_كلام_شهدا #ولایت #ولایت_در_کلام_شهدا #ولایت_فقیه_و_رهبری #کلام_شهدا #حاکمیت_مجتهد #نقد_ولایت_فقیه #ولی_فقیه #ضرورت_ولایت_فقیه #وصیت_شهدا #پیام_شهیدان #اطاعت_از_ولایت_فقیه_خواسته_اصلی_شهدا https://www.instagram.com/p/CFEAyJ8DjKU/?igshid=z0w6il263p6u

#powerpoint#document#kasradoc#ppt#velayat_e_faqih_in_the_words_of_the_martyrs#پاورپوینت#مقاله#پروژه#ولایت_فقیه_درکلام_شهدا#پیروی_از_ولایت_فقیه_توصیه_شهدا#پیروی_از_ولایت_فقیه_در_وصیت_نامه_فرماندهان_شهید#تعابیر_خواندنی_شهدا_از_ولایت_فقیه#شهید#شهید_و_ولایت#فرازهايی_از_وصيت_نامه_شهدا_در_مورد_امام_خمينی#مقام_معظم_رهبری_و_ولايت_فقيه#همراهی_با_ولایت_در_کلام_شهدا#وصیت_نامه_شهیدان_در_خصوص_تبعیت_از_ولایت#ولايت_فقيه_در_كلام_شهدا#ولایت#ولایت_در_کلام_شهدا#ولایت_فقیه_و_رهبری#کلام_شهدا#حاکمیت_مجتهد#نقد_ولایت_فقیه#ولی_فقیه#ضرورت_ولایت_فقیه#وصیت_شهدا#پیام_شهیدان#اطاعت_از_ولایت_فقیه_خواسته_اصلی_شهدا

0 notes

Text

De país imperialista, Irán pasa a ser antimperialista

Los persas conformaron vastos imperios, pero no lo hicieron conquistando los territorios de los pueblos vecinos sino federándolos. Comerciantes más que guerreros, los persas impusieron su lengua a toda Asia durante todo un milenio, a todo lo largo de las rutas chinas de la seda. El farsi, lengua que hoy se habla únicamente en Irán, ocupaba entonces un lugar sólo comparable al inglés actual. En el siglo XVI, el soberano persa decidió convertir su pueblo al chiismo para unificarlo y aportarle una identidad particular en el seno del mundo musulmán. Ese particularismo religioso sirvió de basamento al imperio safávida.

En 1951, el primer ministro iraní, Mohammad Mossadegh (sentado a la derecha) hace uso de la palabra ante el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU.

A principios del siglo XX, Persia se ve enfrentada a las ambiciones de los imperios británico, otomano y ruso. Como consecuencia de una terrible hambruna deliberadamente provocada por los británicos –que deja 6 millones de muertos–, Teherán pierde su imperio y, en 1925, Londres impone a Persia una dinastía de opereta –la dinastía Pahlevi– para acaparar la explotación de los yacimientos petroleros únicamente en beneficio del imperio británico.

Pero en 1951 un nuevo primer ministro iraní, Mohammad Mossadegh, nacionaliza la Anglo-Persian Oil Company. Furiosos, el Reino Unido y Estados Unidos derrocan a Mossadegh y mantienen en el poder al shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi. Para contrarrestar la influencia de los nacionalistas iraníes, Washington y Londres convierten el régimen del shah en una feroz dictadura, liberando al ex general nazi Fazlollah Zahedi e imponiéndolo como primer ministro. Este individuo crea una policía política, la SAVAK, cuyos cuadros son ex oficiales de la Gestapo nazi, reciclados por Washington y Londres y reagrupados en las redes denominadas stay behind.

El derrocamiento del primer ministro Mossadegg llama la atención del Tercer Mundo hacia la explotación económica de la que está siendo objeto. El colonialismo francés era un colonialismo tendiente a instalar pobladores franceses en las naciones que colonizaba mientras que el colonialismo británico es sólo una forma de saqueo organizado. Antes del gobierno de Mossadegh, las compañías petroleras británicas no revertían más de un 10% a los pueblos cuyos recursos explotaban. Inicialmente, Estados Unidos se pone del lado de Mossadegh y propone que se revierta la mitad. Impulsado por Irán, la tendencia a ese reequilibrio se mantendra en todo el mundo durante todo el siglo XX.

Amigo de los intelectuales franceses Frantz Fanon y Jean-Paul Sartre, el iraní Alí Shariati reinterpreta el islam como una herramienta de liberación. Según sus palabras: “Si no estás en el campo de batalla, da igual que estés en la mezquita o en un bar.”

Poco a poco van surgiendo dos principales movimientos de oposición en el seno de la burguesía iraní: en primer lugar, los comunistas, respaldados por la Unión Soviética, y después los tercermundistas, reunidos alrededor del filósofo Alí Shariati. Pero será un clérigo, el ayatola Roullah Khomeni quien logrará finalmente despertar la conciencia de los más desfavorecidos. Khomeini estima que más que llorar por el martirio del profeta Hussein lo más importante sería seguir su ejemplo luchando contra la injusticia. Debido a esa posición, Khomeini será estigmatizado como hereje por el resto del clero chiita. Al cabo de 14 años de exilio en Irak, Khomeini se instala en Francia, donde sus ideas impresionan a numerosos intelectuales de izquierda, como Jean-Paul Sartre y Michel Foucault.

Mientras tanto, Occidente convierte al shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi en el «gendarme del Medio Oriente». El shah se ocupa personalmente de aplastar los movimientos nacionalistas y sueña con recuperar el esplendor de otros tiempos, tanto que llega incluso a celebrar con fastuosidad hollywoodense el aniversario 2 500 del imperio persa, montando toda una ciudad tradicional en Persépolis.

Durante el “shock” petrolero de 1973, el shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi se da cuenta bruscamente del poderío que tiene en sus manos, se plantea la posibilidad de restaurar un verdadero imperio y solicita la cooperación de la dinastía real de Arabia Saudita. Esta última informa de inmediato a su amo estadounidense, quien decide entonces deshacerse de un aliado al que ahora considera demasiado ambicioso, sustituyéndolo por el ya anciano ayatola Khomeini –de 77 años en aquel momento– a quien, por supuesto, rodeará con sus agentes. Pero, primero que todo, el MI6 británico procede a “limpiar el terreno”: los comunistas iraníes son encarcelados; el «imam de los pobres», Moussa Sadr, de nacionalidad libanesa, desaparece para siempre durante una visita en Libia; y el filósofo iraní Alí Shariati es asesinado en Londres. Sólo entonces, las potencias occidentales invitan al shah Mohammad Reza Pahlevi a salir de Irán por varias semanas para recibir “tratamiento médico”.

El 1º de febrero de 1979, el ayatola Khomeini regresa de su largo exilio. Desde el aeropuerto de Teherán, va directamente al cementerio de Behesht-e Zahra (ver foto), donde pronuncia una alocución llamando el ejército a unirse a la tarea de liberar Irán de los anglosajones. La CIA descubre entonces que el hombre al que había tomado por un predicador senil es un verdadero tribuno capaz de movilizar multitudes y de comunicar a cada iraní la convicción de que puede ayudar a cambiar el mundo.

El ayatola Khomeini regresa triunfalmente de su exilio el 1º de febrero de 1979. Desde de la pista de aterrizaje del aeropuerto internacional de Teherán, un helicóptero lo traslada de inmediato hasta el cementerio de la ciudad, donde acaban de ser sepultados 600 manifestantes abatidos cuando participaban en una protesta contra el régimen del shah. Khomeini pronuncia entonces un encendido discurso donde, para sorpresa de todos, no arremete contra la monarquía sino contra el imperialismo. El ayatola se dirige directamente al ejército, exhortándolo a ponerse del lado del pueblo iraní, en vez de seguir al servicio de Occidente. El «cambio de régimen» organizado por las potencias occidentales se convierte instantáneamente en una verdadera revolución.

Khomeini instaura un régimen político no vinculado al islam, denominado Velayat-e faqih e inspirado en la República de Platón, cuyas obras el ayatola conoce a fondo: el gobierno se hallará bajo la autoridad de un sabio, en aquel momento el propio Khomeini. El ayatola aparta uno a uno a todos los políticos prooccidentales. Washington reacciona organizando primero varios intentos de golpes de Estado militares y después una campaña de terrorismo a través de elementos ex comunistas, los denominados “Muyahidines del Pueblo”.