#Vasıf Kortun

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Questions on Institutions

Vasıf Kortun

This text is an edited version of the talk that Kortun gave in October 2017 at The Museum of Contemporary Toronto Canada (MOCA), as part of The Museum Is Not What It Used To Be program series.

Exhibitions are inherently fugitive, fragile and imperfect forms. More than often they are not the most efficient narrative agencies. They cannot be taken off the shelf and leafed through like a book, replayed like a movie on a screen, or repeated as a dance step. They cannot be recovered.

Once done, they can be recalled only as the event they were not meant to be. But, they are not events. As a time-based practice they have short shelf-lives. They replace each other tediously in a simple mimicry of a convenience store. Things are put on the shelf and taken off it. The shell remains the same. The duress of incessant programming of exhibitions coming one after another with “sell-by” dates make ideas obsolete before they are exhaustively unpacked. As good as it lasts, but not for that long. Unless of course they are stale to begin with, ascribing to the condition of the so-called permanent collection that only very few institutions challenge.

By normalizing the rhythm of exhibitions and building spaces to accommodate that cycle we circumvent the possibilities of how art may come to transform itself in the future. Hence, most of the art we see activates itself towards institutions. This forces us not to register new ideas -that might for example not have an exhibitionary goal, mentally and physically on the peripheries of our practices. In a way, each time an art practice engages in a critique of the institution it is at the same time an attempt to pursue a discussion with a zombie.

The question is twofold; how can practices of the present begin without an exhibition in mind, and how can an expanded model contribute to the presentation and discussion of past work. This is not merely a formal exercise, but a need and a necessity. I doubt otherwise that decolonization of the museum will ever take place. That is to say, exhibitionism and coloniality emerge from the same root, and without ensuring that exhibitions are not at the center of a museum’s activities we cannot imagine the future.

Late-capitalist exhibition models and exhibition practices in late-capitalism are about being present, about presencing in the present. As such, a representative institution of its time cannot be contemporary. By contemporary I subscribe to a notion of dissonance and not to what we may say is “new.” Not to be confused with the process of becoming contemporary, neophilia is more or less a negligible divergence anchored to what is already familiar.

Mere presencing suppresses comprehensive analysis in favor of perfunctory treatments. This reflects an institutionalized condition where there is no possibility for an institution to allow itself to change through the actions it commits to. This is not only due to a lack of time for reflection. The change is seen in the context of a program, which on completion leaves the institution “unchanged,” or it changes back again to its previous ways of working. This schizophrenic condition between an institution’s performance and what it purports to be requires unpacking. It is a schism that marks the abdication of the institution’s responsibility, role and commitment to society. What is an institution other than what it does; its research, publications, exhibitions and public programs? Can it have an “identity” beyond that?

From the end of the 1970s, museums have been subjected to an economic condition of perpetual deprivation. Like healthcare and education, they have not been immunised against the volleys of emerging turbo-capitalism. When money began to shrink in the public realm and accumulate in the hands of a few, museums followed the money. To offset the perils of a decrease in public funds and support, they retorted by both living with the new conditions and largely benefiting from them. Their alternatives, the efficient outposts built from scratch by the elites, the oligarchs, fared even better. I have no intention, as you will see further on, to pitch public and private against each other, and/or assume a moral high ground. To the contrary, the harmony and rapprochement between ownership models tells us a lot about not overplaying this difference.

Panhandling to the elites and autocracies that replaced the traditional broad-based civic and locatable (assigned) class, museums became clumsy neoliberal operations. They became something else, and the kinds of institutions that chose not to dumb down and join the charade were singled out as odd, quirky, temporary experimentations not to be taken so seriously. These loners face the threat of falling off the grid. Because their frames are ever so specific.

Hence, with expanding development teams, experience and management units and asset marketization they turned themselves into representative institutions of their time. They turned their capacities and potentialities into assets to be marketized and brand peddled to secure the present moment. We could claim that they forfeited their future.

Institution’s Time

How can institutional time be reimagined? It is essential to recognize that institutions exist in three different times concurrently. Exhibitions perform in the “present time.” Meanwhile, the institution is a heritage machine bearing and asking questions around unresolved, ignored, absented and obscured stories from the past, and also negotiating, fermenting, testing out, in the best case, possible futures. Museums’ mandates used to be clear: to do everything in their capacity to advocate a better world than the one received. This used to be in The International Council of Museums’ (ICOM) mission statement until recent years. Simply, not making things worse. The “better” is unambiguous. At the most basic level an ecologically maintained world with unobstructed rights to knowledge, common resources, fundamental services like health and education and equality of species including those that do not have a voice of their own. To support, cherish and voice these rights is not becoming political in a narrow sense of the word. It is simple decency. If the clock is ticking for the human species, as some claim, we can delay our demise with dignity.

I used to believe that the museum does not have to take a side, but only present a strong argument to help people make better informed decisions. I am not so sure now; but we can discuss this later.

If institutional time is not the present time, what would be some of the ways to become contemporary? One strategy is to be transparent and opaque simultaneously while keeping these two actions separate. Most amazing contributions to public thinking were fermented, tested, and negotiated away from the threatening gaze of the order, philistines, shared half-truths and populists. This need -in times of an ascendant global fascism- is becoming ever more urgent today. We have to nurture and protect. Hence, an institution is a monastery as much as it is a church. But it cannot be a church looking like a monastery for the cognoscenti or a monastery looking like a church. It can neither be a public space where only privileged voices are echoed, nor a protected space where all ideas are equally worth discussing. These things are to be kept separate from each other. Transparency and opacity overlap only in a performative or an unpredictable condition. This sudden condition of radical empowerment, as we know, can never be lasting. It is more like what Zygmunt Bauman has called a “swarm” when referring to occupy movements, and the Arab Spring.

We work in a trajectory of the past and the future, which means we have multiple publics we are accountable to and need to take care of: The public of the present moment; a public that keeps arriving from an unresolved past, a past that will not go away, that has to be constantly confronted and pushed forward. Lastly, there is a future public which is why we do what we do. So, the institutional public is a plurality that does not privilege the moment and any decision we make in the moment has an effect on all three temporalities, which includes changing the past in the present. As Walter Benjamin had written: “If the past insists, it is because of life’s unavoidable demand to activate in the present, the seeds of its buried futures.” This notion of history and future collapsing into the present moment trumps the classic approaches to the assessment of an institution.

A core issue here is to underscore the notion of the museum situated as a non-capitalist institution embedded in a turbo-capitalist economy. Please note that there is a difference between anti-capitalist and non-capitalist. The first is a political position, while the second a public condition. It was the only condition that was not to be surrendered by the social state or the welfare state. Non-capitalism is about public time, which holds a society together and that turbo-capitalism has helped erode and decimate. The average lifespan of a private company is less than a century, about 75 years, but public time is supposed, or expected to be, more or less infinite. The museum is a three centuries old operation. That makes it older than most countries, economic or political systems.

Management

What does management imply? Management types are brought in to increase operational efficiency and cut costs. We have always relied on the same argument: What do art historians know about running a museum, doctors about running a hospital or professors running a university? Really? However, there has never been a model of “neutral success” that allows better fiscal and operational strategy without a substantive shift in the institution. The managerial approach has given way to at least two generations of directors who may have the proper background in art history but have embraced a different role altogether. Finding a recipe for mere financial success does not make a director great.

Management also means the monetization of certain assets and conversion of other assets to liabilities waiting to be unloaded. Asset analysis leads to increased loan and service fees and ends at times in heedless deaccession. Certain tools of the museum become asset class objects with unaffordably high loan fees taking the less powerful institutions out of the game, hence denying the public of those institutions the possibility of experiencing certain work. Other tools of the museum become liabilities or orphan objects ready to be shipped out or auctioned off to and passed on to the private sphere. They are no longer available as unique insights, testimonials, and indispensable tools to tell stories. The outdated role of the keeper/connoisseur has been replaced by a network of curators entangled in a grid of collectors and dealers

Cutting costs means smaller research and curatorial departments and increased outsourcing and contracted services. That is to say, the core operations of the museum become serviced by third parties and temporary staff. To add one more spin to this scenario is the new workplace culture. Especially rampant in the cultural sphere is that museums are increasingly staffed with itinerant knowledge workers where a sense of belonging is replaced by the notion of one station of a career. Institutional royalty and vice versa is, similar to, business world have changed.

All this opens the way to institutional blunders, bloated development funds and other nonessentials such as reliance on head hunters and consultancy companies.

Institutions have sought strategies to delay their demise through mergers, takeovers (PS1 being taken over by Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)), brand expansion (Guggenheim Model), administrative centralization (Pompidou branches) and streamlining, divestiture of assets (Berkshire Museum) or asset capitalization.

This paradigm shift means simply handing over the institution to contemporary desire, one that privileges the present moment over any other.

We are living, as we all realize, in the ever present. Management rules in a horizon of less than a few years. We are stuck in a present without a direction. As we lose a sense of horizon we get more stuck in the present. As our colleague Manuel Borja-Villel said “we are trapped in a past in which we don’t recognize ourselves and a present we don’t like.” Borja-Villel continues, in a discussion with Charles Esche to say that the situation “promised an illusory life” in the “infinite present” and changed the way “humans perceive themselves and their position in relation to each other and to time.” You can also call it “post-history” if you prefer. Post-history emerged at the end of the 1980s and ushered in an era of no conflict after the fall of bureau communism, followed by deregulations and a chipping away of the welfare state.

There are ever fewer reasons to be cheerful about the world we inhabit, with less than half a century left for our species that sees every other living or inert being in subordination as a form of resource or waste, a massive deterioration of income balance and normalization of institutional and societal corruption. In such an accelerated present it should come as no surprise that we can conceive the realm of institutions as part of the problem. We are part of the problem. It does not help at all when MoMA puts up a show of paintings by Muslim artists in response to Donald Trump’s travel ban. It is a public relations gimmick, and does not change the fact that MoMA is funded by oligarchs and that its programs have not at any level questioned what brought us here.

Institutions offer neither a sustained criticality nor a counterpoint. Whether we can restore them to a historical position without the colonial/imperial baggage of their own past is a fair question, but even then, the institution's role is limited to more one of restoration than transformation. The limits of its commitment (to this responsibility) is to be recognized as well. Another point to discuss.

Who are we loyal to? Who do we care about? Who do we talk to? Who do we talk with? What is the world we want to live in while knowing the impossibility of reaching it. Lines of loyalty have to be realigned, so as to address not the tribal and self-serving interests of those who act in the name of the museum and to not simply get bogged down by the public private dichotomy.

Deeply problematic within the institutional sphere is that museums are neither on the side of the artists nor do they seem to be there for public interest, and there is a sharp contrast between their jargons and their actions. While this discussion has to be parsed further to bring an end to the public private dichotomy and understand better what it means to have tribalized/ privatized interests. To place the burden on ”privatization’’ is correct. However this situation impacts equally public and private. Public or private funding, both are in effect privatized interests of a representational system.

There is a sense of helplessness, where institutional actors are uneasy with this situation. But at the same time they are unwilling to draw conclusions from the experiences they are subjected to and they do not investigate why they perhaps cannot claim their historical position. There are not only the vested interests at stake, but also the institution’s imperative is to survive. Surviving in this case is not a particularly commendable act as it is not linked to a capacity that needs to be protected or nourished. The question is not whether we need institutions but what kind of institutions we need. Worse, the level of cynicism, the sense of resignation and lack of imagination has become pandemic.

Is it possible for cultural institutions working within contexts of real estate expansion, privatized interest, and cultural and proprietary rights to respond to the times? I am not speaking of knee-jerk reactions to daily politics or assuming a pseudo-lefty, humanist position of the classical art world. We are no longer dealing with specific signs, but with a global situation.

It is essential then to resist the spectacular, the privatization and theme-parkisation of social life, and turn our compass to a democratic project. As Chantal Mouffe has suggested, our larger objective is transforming institutions “into a terrain of contestation of the hegemonic order.”1 But this is only half-right. The order can hardly be located, it is embedded and without decolonization -hence the contestation of our own positions- not much will actually change. What we can do at best is to develop positions where we can be ready for change.

The museum world has been increasingly embedded in a network of relationships that preclude public purview. That is to say, it has become a pre-public (or post-public) realm with dispositions and residues presented for plebian consumption. While the outputs appear to be similar, the processes through which decisions are being taken have been privatized in a self-affirming global network of private and public contexts alike.

Looking at it from another angle, private or public initiative is not the question as long as the overwhelming concept is about a passive receiver, an audience, a viewer or a visitor that lacks the capacity, tools and agency to articulate its desire. This power-based lack of communication between the institution and its outside needs rethinking. What remains outside does not have a place for its desires to be recognized. Seamless spaces are offered between the “customer” and the “provider” in a charade of market-tested exhibitions as the possible public is extracted from the equation and replaced by processes of managerial quantification.

In more than one way, it seems that we have switched models along route and not fully realized it. Between the museum ideals of the late 18th century and late 20th century fundamental shifts have taken place. But, it is not a time we can or need to go back to. In fact, the model of the institution that has appeared in the last four decades is in alignment with the diegesis of the originating narratives of the industrial fair and theme park. Specifically, it follows the theme parks’ reincarnation after the Second World War, which was made secure and safe for middle-class families as a form of clean, branded tourism answering to all of one’s needs from shopping, restaurants and kids entertainment.

I was listening to an interview with Tom Krens recently. I was dumbstruck by his valorization of the “theme park” as a viable example for the museum world. It seems I was correct in my conjectures regarding the double legacy of museum practice as residing not in the history of the museum but in the theme park and the industrial fair. This decoupling from the museum heritage model was precisely the point.

Many of the big player institutions in major cities have already accommodated aspects of this double legacy. They act as consumer heaven and leisure time producers, forecasting a tourist class that keeps on swelling with the incorporation of new audiences from India, China, sub-Sahara, the Gulf and South East Asia. In parallel, the citizens being catered to have also been “downgraded” to a generic tourist class. This is of course not all that these institutions do, and an institution is never “one” thing. But it is apt to bear in mind that certain empire institutions have become stronger through relationships they have entered into with the “rest” of the world, which only three decades ago were contexts framed outside (their) historical time.

The transformation is coupled with what I call “powerless socialization.“ This is an experience that has all aspects of a notion of publicum, which is then reduced to an experience such as congregation in the new agora, by their own volition as part of their role on the design of the space. However, the public participation in such spaces is about a managed inclusivity. That people congregate and get together in these spaces can hardly ever evolve into anything constructive. Despite lofty declarations that speak of museum atriums holding political potential, these are not the places of the beginning of a new democracy, they will not become potential agoras or places of mobilization. They will not offer the tools towards self-determination. In “powerless socialization“ there is hardly anything that connects the “audiences” by way of necessity.

Mostly, the museum has become a pleasure space. It often summons a tour de force architecture. The exhibition experience is reduced today to the visitation of new sacrosanct edifices of “starchitects.” This sacral experience is not about the actualisation of a bona fide civil society. It in fact hinders such an attempt, and reduces the potential of activating culture’s capacity in helping shape a society.

But it is instantaneously branded for what it is. It is a place coextensive with the leisure and tourism sector. Consumer exposure is sublimated with brand recognition. Such a model, in order to survive, requires nonstop real-estate expansion and construction. Otherwise, it will collapse. Like most things in the late-capitalist economy, the exhaustion is part of the script. Death is premeditated, inevitable and purpose-built. Hence, when you see museum expansions in cities and power corridors like Hong Kong, New York, Moscow, and Berlin, do not be surprised. Expansion is about survival; expansion is also a recognition of an end and this is not a paradox. In fact, this model does not embody a single paradox. What we often see is the reticulation of the same artist and architect names, works mostly indistinguishable from each other, from one institution to another, and narrative hierarchies must be more or less accommodating of each other. They must look like each other in a grid of compatibility to suppress the absurdity of the whole enterprise.

Meanwhile, museums outside brand cities keep on unravelling. A dire script has been in front of them for the longest time. Their locatable, historical support-class has dissolved and so has the the civic sector. The “new support class” knows only of the vertical order; it is not grounded, it is unhinged from time and space and often looks only to London, New York, Los Angeles and other power corridors and will park its stock of “talents” wherever it desires. I mean “park” because it refuses to respect historical norms. Park, because it literally parks in terms of long-term loans often protected by hard contracts. This is so unlike the horizontal and distributed support classes of the past! That is to say, there is a difference between a civic membership at twenty dollars a year of 10,000 people versus one person giving 2,000,000. Guess who has the power now? What takes more work to raise? And what do you have to do to make that person give again?

It did not take a genius to forecast such a historical transformation as second cities began to spin into a crisis over a decade and a half ago. It was nevertheless too hard to surrender to the inevitable for any subject born into a welfare state. They believed that the hell we live in today was momentary, that it would pass. So, instead of introducing and testing out different methods for their institutions, many institutions preferred to remain obstinate to the challenges, effectively subjecting themselves to increasingly anemic conditions and even insolvency.

At the same time the administration of the museums began to change. When managers begin to administer institutions as if they were companies, just like hospitals or universities, they became increasingly subjected to a managerial logic. As the curator and former museum director David Elliott has remarked, “Management has become elevated as a skill in itself that has no relation to any particular discipline or knowledge.”

Unfortunately, to expand on what I said before, most of the managerial reconditioning ends up in an ingest of more of the poison that got them sick in the first place. The point is not simply the survival of an institution, that is not the question, surviving is neither important nor essential. It is about rethinking the institution’s promise and keeping it germane through changing times. A survivalist attitude without a core mission makes the institution more vulnerable to tribal interests. Tribal interests are in the business of leverage. Why do we live? Why does anything live and is there a dignified resignation?

Short-term panacea could be tantamount to turning museums into zombie institutions. In short, when museums with a public service mandate enter, as non-capitalist institutions, in the late-capitalist economy, they enter a field in which they have no public endorsement and have to abide by the protocols of instant assessment, short-term efficiency and becoming the servants of the moment in which they operate. These institutions are zombies because they do not know they are dead.

The kernel of the problem lies in the tension between contrasting economic models and the way historical public institutions and contemporary capitalism have completely different ideas of what public good constitutes.

The museum world has been increasingly encircling power corridors. Power corridors are the kind of spaces where energy and arms markets crystallize, with financial markets forming the outer shell.

Places and institutions that do not fall in the category of the spectacular, places that are below the network radar, get phased out of the presiding narratives. Medium‐scale institutions keep on disappearing like institutions in the second cities. “art centers,” “ICAs,” “kunstvereins” have less traction than before. The “middle” keeps on dropping out because of an increasing market demand for large‐scale institutions.

Smaller operations are not octopoid in reach, they are not tooled to accommodate branded projects or complex sponsorship schemes. The middle continues to evaporate, or it is forced to scale up under intensely privatized and competitive cultural spheres. It also drops off because sponsorship is furtively directed to institutions with brand value. In short, as in economy, money concentrates in the hands of the few, the middle is disappearing and the small is destitute. Finally there is the itinerant subject of the precarious knowledge worker (and even institutions) that accept these protocols and try to stay ahead of the tide until they burn out.

We know that the museum is not what it used to be, and has not in general developed into a system of rewarding frameworks. There are still too few institutions that do not merely act as the acquiescent platforms of their time. No longer the eternal institution on par with the church and the city hall on a public square, the last 35 years has seen more than a measured transformation. The public and the museum of 250 plus years have been descaled as part of an epistemic shift.

It is both harder and easier to institute in these times, understanding that the normative blueprint has become inoperative. A cardinal rule for a new institution would be incorporating and welcoming contradictions and failures; another is to develop a culture that looks at things from different disciplines, and incorporates academic discourse that is open to the public.

The task is to address visitors who are not ready, captive audiences and who are certainly and rightfully doubtful of museums in which there are often no narratives that incorporate them, or in which they find themselves forced to over-identify. To do this it is necessary to welcome new tools that enable the public imaginary to flow into and eventually help transform institutions from within.

The task is also to denaturalize the institution’s presumed authority, or at least accept that it is only a presumption to be reasoned and disputed. It is essential to not simply utilize but to invent new tools and agencies that release the burden of being location specific, that open and make clear controlling influences that affect institutional transparency, and that do not use the language of the royal plural.

In short, if the institution can no longer be public because of its bylaws, how does it become public? The point is not to interpret the world and present it as a kind of “commodity” but to be in it and accept the consequences of a complex co-location.

In the 20th century, there were times when museums were able to dispute the systems that supported them but they were at the same time tied to them. This correlation was recognized as the role of culture and its institutions as a functioning stratum within civic, democratic projects. The question for today is how production, mediation and dissemination can be (re)democratized and what effects would that have on our museums? Would such a dispositive propel us to rethink the institution’s role in society?

SALT

I do not think the work we pursue at SALT is unorthodox. It is in fact deeply rooted in history and institutionality. Our imperative was not to be novel, radical or cutting edge. In fact these feel more like formalism. We actively attempt to cushion the impact of a vociferous market and disregard most of what seems to be “in” or what is acknowledged as “exceptional” and peddled to a “kitsch cognition.” I always claimed that we program for people who are more intelligent than us, because we do not believe people are simple-minded. They do not want to be infantilized. Given the tools our users are amazingly crafty in making collective decisions and would likely claim that other institutions’ attitudes to their audiences are often preachy. When we begin a project we exercise what we call “a state of unknowing.” This is not to say we are deferring to a cute 2.0. museum philosophy in full accord with the business of cozy collectivity, creative economy and the like. For SALT, the idea is to enter an agonistic sphere where difficult questions can be posed without being considered incriminating or hostile.

SALT is not an artwork collection-based institution. Hence there is the considerable luxury of looking at objects without their routine handicaps. Focusing upon research and treating what we work with as potentially discursive objects, SALT becomes more involved in actualisation of said objects’ capacity. As such, the question is not about custodianship but shaping novel narratives and, telling multiple histories of art. There is never one story. History is not fixed, and any attempt to invent a canon is delusional or authoritarian or both delusional and authoritarian.

In continuum with the treatment of objects and things, SALT has from its very beginnings disengaged from the curatorial. We do not have curatorial positions because the way we work acknowledges the curatorial figure neither as an “auteur class” nor a classical keeper. SALT’s dispositive is to visualise research in what we have been calling a post-curatorial approach where different subjectivities, from the professional, academic or purely curious and interested, are assembled around a project. The result does not quite look the same but more importantly, how we get to conceive a project is different.

We questioned the standard departmentalized, compartmentalized master plans of museums from the very beginning. As György Kepes had written “Ignorance, inertia, but mostly fear that we may be forced to give up vested interests has kept us from pooling our knowledge.” Dismantling the obtuse results of departmental arrogance was a place to start, and it is not only semantics. We actively engage with art and other things from non-discipline-limited angles and attempt to make informed decisions based on rigorous, independent, and open research. If you cannot link your work with a prerogative of thinking beyond the purely monographic, chronological, medium-bound, similar approaches, you cannot proactively create different frameworks. Without these frameworks we cannot invent models that are faithful to art and its practices. We have to be open to incorporating contradictions into our discussions, as there is nothing less stimulating than non-striated, smooth spaces. Diversity and being open about your lack of competency in any interdisciplinary practice is a sine qua non.

If compartmentalization was a bad idea to start with, it has become entrenched with an obtusely arrogant professional jargon over many decades. While non‐medium‐specific departments have been no‐brainers for a very long time, the anxiety is real. Some institutions introduce inter‐curatorial positions, others offer stopgap measures but at the end, departmentalization is bound to disappear.

In short, SALT provides a unique climate where different sets of knowledge clash and benefit from each other without any arrogance. I believe that the desire to build a “museum” in the 21st century stems from self-doubt, it may be an arriviste concept, it may be self-orientalizing, and it is certainly not very original. It is somewhat unfortunate that most people working in non-Western contexts choose to emulate Western models of the museum. To pursue a model that has been invented years before, that is translated without a stipulation for a new social and cultural context is to say the least, odd. It seems that this condition of coloniality has outlived colonialism.

We decided to not grow in an evolutionary manner. We did not follow an industrial, evolutionary model. Instead, we redefined for our case an institution for the 21st century by not trying to repeat the mistakes of the past. What kind of people do we want to grow with? How do we shape a reality? Hence, incrementalism was not allowed. A colleague made a great remark in an interview in 2009 during our expert discussions that perhaps articulate what I am trying say best. Markus Novak said: “You can look at evolution as fitness. Which is the sort of an industrial way of understanding it... Or you can look at it as diversity… And it’s much more interesting to figure out a mechanism for producing diversity which requires the fostering of mutations… They can be applied culturally to the functioning of an institution or to the content of what is shown and what is curated for the purpose of not fixing categories, but constantly producing new ones, trusting that the rest of culture will take care of fixating it.” Novak’s metaphors about the evolutionary and industrial model could be taken as a kind of trying to achieve a “limited excellence.” That is to say that in places with unremarkable thresholds, there is pretty much nothing that cannot be anticipated.

From our very beginnings we have been thinking of the concepts of users, communities of interest, professionalized audiences, constituencies as opposed to terms such as audience, customer or visitors. Not that all cannot exist concurrently within an institution, but we cannot be a different thing for each person or group. Unfortunately, we do not have tools that enable our visitors, but we believe in opening a space in which they can be invented. SALT is slowly morphing from a “broadcast institution” to something that develops intelligence with its users, a collective intelligence if you will. For the “audience” to become embedded and active, one needs many organic interfaces that are built with trust and care in mind. Our question is the following: What are the strategies for establishing ethical and non‐hegemonic agencies and agonistic conviviality?

Our benchmark has not been mass media, or the head-count, and certainly not the occult methods of data aggregation. We are interested in genuine reactions, and how our projects are translated into curricula in universities; how content and information can move people out of their slumber to look at the world differently and work differently. We like to assist people in developing goals that allow them to become more hopeful, more intrigued and more prone to making informed decisions; and we like to do this without being preachy or talking down while in engagement. We did not have a hegemonic desire to address each and every unprivileged person or group, or to employ military terminology like “target” audiences. What SALT instead does is engage in discussions and platforms for debate that reach beyond the traditional support basis. Perhaps, with the hope that engagement with different segments of society will turn some into constituencies and consuls and translators in their communities. There has been a developing taxonomy of “embedded institutions” within SALT, collaborations, hosting and simply space allocation. At different levels of visibility these institutions could be working groups released from the university due to their politics that do not align with the government, as well as NGOs, documentary film festivals, performance groups, human rights and LGBTQ associations. Hence, the cultural, social and civic education is realized in the wider perspective. Can we benchmark that?

A critic had written on SALT that it “attempts to realize the kind of multidisciplinary, research-based practice that normally individual artists, collectives and short-lived art centers have been able to pursue.” I appreciated this note as it spoke to one of our goals of thinking of the institution as a flotilla of individual boats rather than a mothership. SALT is shaped by this multiplicity of experiments and ideas, its failures and relative successes. There is an artistic culture that permeates the place without having always to deal with art. The questions we started with in 2007 and opened with in 2011 may at some level be history now. However, to put things in perspective, some of our questions were: what should a future institution look like? Can we scale up without yielding to fame and populist blockbusters, and can we retain agility? We did not want to run SALT in a centralized manner. The guiding ideas, the motivation, the spirit and the collaboration should be close to each other, but they shouldn't be run from one place. We thought about a certain “ecology of things.” For instance, how to have a physical wall system that does not require repaints and constant waste production for each project. SALT is a debranded institution and uses forms of communication that do not need the mainstream media. Because we seek a true interdisciplinary dialogue, the absence of a more pristine commercial gallery-like environment has allowed us to open the field and understand our buildings as tools. It is all about stimulating curiosity and curiosity is not disciplined. At SALT we prefer artists, exhibitions and graphic designers, or really anyone or thing involved in our projects, to enter into a relationship with the context that is based more on process and less on the objects to be displayed. It is not something that we plan in anticipation, but I would say it is a side effect of the relationships we establish with all our collaborators. The architecture of the buildings is also a case in point -we worked with eight different younger architectural groups from Turkey under the umbrella of one main architect to coordinate the right ecology for each function, and to foster new design concepts.

When we complete a project it remains problematic. We expand the time frame of its existence with post-programs, we release publications months or sometimes years after it has finished. We also serialised certain exhibitions, one of which was structured in the form of “modern essays,” or we would establish year-long exhibition series as if they are radio-plays, in these ways we would go at issues again and again from different angles. All this was done not in a grand sense of historical correction but to produce prototypes for subjectivities, hoping that the rest of culture takes care of it, uses them, plays with them, and develops them. This is in accordance with our political position that art and consequently exhibitions are not for everybody; we are not for the masses. That is to say we cannot be interested in an entity that has no shape, can neither be abstracted nor voiced. But we are extremely interested in anybody who we can enter into a discursive, agonistic, supportive discussion with.

Chantal Mouffe, “The Museum Revisited,” Artforum, 2010, p. 326↩

0 notes

Text

SALT Galata'da Uzun Perşembe: Vasıf Kortun'la kurum pratikleri

Her ayın son perşembesinde saat 22:00’ye kadar açık olan SALT Galata’da bu ay Vasıf Kortun ile kurum pratikleri üzerine konuşulacak. SALT Galata 30 Mart’ta saat 22.00’ye kadar açık. 31 Mart‘ta SALT Araştırma ve Programlar Direktörlüğü görevinden ayrılıp kurumun Yönetim Kurulu’na katılan Kortun, çalışmalarına yazar, araştırmacı ve danışman olarak devam edecek. Unvanıyla yapacağı son konuşmadaise…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Commissioned to work with SALT Research collections, artist Refik Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among 1,700,000 documents. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives are, in turn, translated into an immersive media installation. Archive Dreaming, which is presented as part of The Uses of Art: Final Exhibition with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union, is user-driven; however, when idle, the installation "dreams" of unexpected correlations among documents. The resulting high-dimensional data and interactions are translated into an architectural immersive space. Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist for Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence Program where he closely collaborated with Mike Tyka and explored cutting-edge developments in the field of machine intelligence in an environment that brings together artists and engineers. Developed during this residency, his intervention Archive Dreaming transforms the gallery space on floor -1 at SALT Galata into an all-encompassing environment that intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges immutable concepts of the archive, while destabilizing archive-related questions with machine learning algorithms. In this project, a temporary immersive architectural space is created as a canvas with light and data applied as materials. This radical effort to deconstruct the framework of an illusory space will transgress the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library and the conventional flat cinema projection screen, into a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive visualized with machine learning algorithms. By training a neural network with images of 1,700,000 documents at SALT Research the main idea is to create an immersive installation with architectural intelligence to reframe memory, history and culture in museum perception for 21st century through the lens of machine intelligence. SALT is grateful to Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program, and Doğuş Technology, ŠKODA, Volkswagen Doğuş Finansman for supporting Archive Dreaming. Location : SALT Gatala, Istanbul, Turkey Exhibition Dates : April 20 - June 11 6 Meters Wide Circular Architectural Installation 4 Channel Video, 8 Channel Audio Custom Software, Media Server, Table for UI Interaction For more information: https://ift.tt/2qQA5hl _________ Credits: SALT Research Vasıf Kortun Meriç Öner Cem Yıldız Adem Ayaz Merve Elveren Sani Karamustafa Ari Algosyan Dilge Eraslan _ Google AMI Mike Tyka Kenric McDowell Andrea Held Jac de Haan _ Refik Anadol Studio Members & Collaborators Raman K. Mustafa Toby Heinemann Nick Boss Kian Khiaban Ho Man Leung Sebastian Neitsch David Gann Kerim Karaoglu Sebastian Huber

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcel Duchamp’ın İzinde Kavramsal Sanat

Kavramsal Sanat veya bir diğer adıyla Fikir Sanatının temeli 1. Dünya Savaşı sonrasında Dadaistler tarafından atılmıştır. Bu akım savaş sırasındaki şiddete ve o dönemin estetik değerlerlerine karşıdır. Dada sanatçıları eserlerini belirli bir mantık çerçevesinde gerçekleştirmezler. Aslında savaş sonrası buhran döneminin izleri sanatçıların eserlerinde gözlemlenebilir. Onlar burjuva kültürüne ve geleneksel sanat formlarına nefreti kendilerine konu edindiler. “Hiçbir şey sonsuza dek aynı kalamaz.” felsefesini savundular. Özünde bu fikir savaşın yarattığı yıkıma bir göndermedir. Edebi eserler veren sanatçıları ise dili değişik biçimde kullandılar. Türkiye’deki garip akımıyla paralellikleri vardır.

Dada akımının görsel anlamda en önemli isimlerinden biri ise Marcel Duchamp’tır. Duchamp 1887 yılında Fransa’da doğdu. Kariyerine ressam olarak başladı. Önceleri post empresyonizmden etkilendi yani resimlerinde geleneksel sanat formlarını uyguladı ancak 1. Dünya Savaşı’ndan sonra bu tavır Duchamp’a anlamsız geldi. Savaş başladığında ise savaşa katılmamak için Paris’ten Amerika’ya taşındı. Savaştan sonra eserlerinde hazır malzemeler kullanmaya başladı. Duchamp sanatın 1. Dünya Savaşı öncesinde göze hitap eden bir şey olduğunu ancak, savaş sonrasında ise akla hitap etmeye başladığını düşündüğünü söyler.

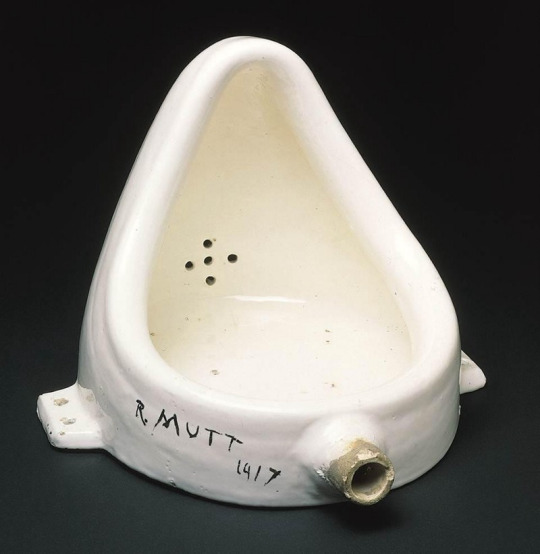

Fıskiye, Marcel Duchamp (1917)

Sanatın kavramsal yönünü vurgulamak için eserlerine güçlü isimler vermiştir. En önemli eserlerinden olan Fıskiye sanatçının bir pisuara attığı imzadan ibarettir. İmzayı ise kendi imzası olarak değil, dönemin meşhur çizgi film karakteri olan ‘R. MUTT’ adına atmıştır. Aynı zamanda bu kelime okunuş bakımından Almanca’da “fakirlik” anlamına gelmektedir. Ancak bu eser dönemin bazı sanat eleştirmenleri tarafından ahlak dışı ve hırsızlık olarak tanımlanır. Aslında önemli olan onun pisuarı seçmesidir. Günlük hayatta kullandığımız bir objeyi alır ve onun “kullanışlı” olan anlamını yeni bir başlık ve görünüşte bize geri verir. Yani bir bakıma “hiç”ten bir düşünce yaratır.

L.H.O.O.Q, Marcel Duchamp (1919)

Duchamp’ın bir başka eseri ise Mona Lisa reprodüksiyonu olan L.H.O.O.Q’dur. Bu eserinde Mona Lisa tablosunun bir kopyasına bıyık çizer ve altına L.H.O.O.Q imzasını atar. Bu kısaltmanın anlamı Fransızca “Kızın kalçaları ateşli.” cümlesinin baş harfleridir.

Duchamp sanatçının değerinin toplum tarafından çok abartıldığını düşünür. Sanat üretimini otuzlu yaşlarında bırakır ve hayatının geri kalanını satranç oynayarak geçirir. 81 yaşında vefat eder.

Kavramsal Sanat 60’lara kadar çeşitli eserlerde kendini gösterse de tanımı 60’larda yapılmıştır. Sol Lewitt “Kavramsal Sanat Üzerine Paragraflar” makalesini 1967’de yazmıştır. Sanatın en önemli yönünün fikir olduğunu söyler. Lewitt’e göre eser yapılmadan planlanır ve “Eğer ki fikir iyiyse, eser doğrudan iyidir.” tezini savunur. Onun için sanat sadece göze değil beyne de hitap eder. “Başarılı eser bakış açımızı değiştirendir.” der.

Bir ve Üç Sandalyeler, Joseph Kosuth (1965)

Kavramsal Sanatın bir diğer öncüsü ise Joseph Kosuth’tur. “Kavramsal Sanat, sanatın özünü sorgulayandır.” demiştir. Önemli eserlerinden biri olan Bir ve Üç Sandalyeler’de sandalyenin kendisini, fotoğrafını ve sandalyenin sözlük anlamını yan yana koymuştur. Onun için anlam çok önemlidir. Kosuth aynı zamanda ‘Sanat ve Dil’ grubunun üyesidir. Bu grup Kavramsal Sanatın ve sanatçıların dili olmayı amaçlamıştır. “Sanatın doğası nedir?” sorusu bu grup için büyük önem teşkil eder. 1967’de yazdığı ‘Felsefeden Sonra Sanat’ makalesinde “Duchamp’dan sonra bütün sanat eserleri kavramsaldır çünkü sanat sadece kavram olarak varolabilir.” demiştir.

Parçayı Kesmek, Yoko Ono (1964)

Performans sanatçısı olan Yoko Ono ise Vietnam Savaşını eleştirmek için Parçayı Kesmek adlı eserini 64 senesinde sergilemiştir. Bu eserde izleyiciler teker teker gidip Ono çıplak kalana kadar kıyafetinden bir parça keser. Yoko Ono eserini performe ederken risk alarak insan şiddetine dikkat çekmek istiyordu. Yoko Ono Fluxus Hareketi üyesiydi. Bu hareket popüler kültüre yönelik harekete karşıydı. Kendilerini aynı zamanda Neo-dadaist olarak adlandırdılar. Halkın katılımı, Parçayı Kesmek’de olduğu gibi neo-dadaist için önemliydi. Halk ve sanatçı arasındaki sınırları yok ederek “Herkes sanatçı olabilir.” dediler.

Spiral Dalgakıran, Robert Smithson (1970)

70’lerde ortaya çıkan Arazi Sanatı ve Performans Sanatı da Kavramsal Sanatın konularındandır. Arazi sanatçısı olan Robert Smithson Spiral Dalgakıran’ı yaparken doğanın gücünü göstermek istemişir. Toprak yığınından yapmış olduğu dev spiral dalgakıran yaklaşık bir yıl içerisinde yok olmuştur. Spiral şeklinde olmasının nedeni ise spiralin doğada en çok bulunan formlardan biri olmasıdır.

Kavramsal sanat ile birlikte artık sanat maddesizleşmişti yani eş zamanlı olarak gözlemlenemiyordu. Yukarıda bahsedilen iki örnek gibi sanat eserlerini artık video veya fotoğraflarla da gözlemlemek mümkündü. Çünkü artık önemli olan görsellik değil fikirdi. Bu konuyu ilk olarak 1968'de Lucy Lippard Sanatın Maddesizleşmesi makalesinde ele almıştır.

MoMA- Poll, Hans Haacke (1970)

Başka bir önemli sanatçı olan Hans Haacke ise sert mizaçlı biriydi. İşleri bütünüyle politikti. MoMA-Poll isimli eserinde izleyicilere “Vali Rockfeller’in Başkan Nixon’un Vietnam Politikasını kınamaması Kasım’da ona oy vermemeniz için bir neden midir?” sorusunu sorar ve cevaplarını kutluya atmalarını ister. Bir bakıma insanları bu fikir hakkında düşünmeye sevk etmek ister.

Kavramsal sanat için önemli olan fikir olduğuna göre onu seçen insan da bir o kadar önemlidir, bu ucu çok açık bir sanat konusu olduğu için günümüzde sanatçılar bu dalda sayısız eserler vermiştir. Kavramsal sanat ilk olarak 1969’da Harald Szeemann küratörlüğünde Tavırlar Forma Dönüşünce sergisi ile Avrupa sanat ortamında yerini almıştır. Szeemann’ın düzenlediği bir diğer sergi ise Documenta 5'tir. Tematik büyük sergiyi gerçekleştiren ilk küratördür. Eski Documenta sergileri büyük resimlere sahip iken, Documenta 5’ de performans sanatı ve deneysel filmler gibi kavramsal sanatın çoğu dalına yer verilmiştir. Günümüzde ise bienaller en önemli kavramsal sanat etkinlikleridir. Hemen hemen her dünya başkentinde gerçekleştirilen bu sergiler iki yılda bir olup ulusal ve uluslararası sayısız esere ev sahipliği yaparlar.

Diğer Kaynaklar

Norbert Lynton, Modern Sanatın Öyküsü, çev. Cevat Sapan — Sadi Öziş (İstanbul: Remzi Kitabevi, 2004), s. 123–134.

“Cut Piece (1964)”, http://onoverse.com/2013/02/cut-piece-1964/

Vasıf Kortun, “Bağımsız küratörlerin piri: Harald Szeemann”, Radikal, 2 Mart 2005, s.1.

#marcel duchamp#yoko ono#kavramsal sanat#sanat#robert smithson#hans haacke#joseph kosuth#sol lewitt#harald szeeman#fluxus#dadaizm#neodadaizm

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Archive Dreaming from Refik Anadol on Vimeo.

Commissioned to work with SALT Research collections, artist Refik Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among 1,700,000 documents. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives are, in turn, translated into an immersive media installation. Archive Dreaming, which is presented as part of The Uses of Art: Final Exhibition with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union, is user-driven; however, when idle, the installation "dreams" of unexpected correlations among documents. The resulting high-dimensional data and interactions are translated into an architectural immersive space.

Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist for Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence Program where he closely collaborated with Mike Tyka and explored cutting-edge developments in the field of machine intelligence in an environment that brings together artists and engineers. Developed during this residency, his intervention Archive Dreaming transforms the gallery space on floor -1 at SALT Galata into an all-encompassing environment that intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges immutable concepts of the archive, while destabilizing archive-related questions with machine learning algorithms.

In this project, a temporary immersive architectural space is created as a canvas with light and data applied as materials. This radical effort to deconstruct the framework of an illusory space will transgress the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library and the conventional flat cinema projection screen, into a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive visualized with machine learning algorithms. By training a neural network with images of 1,700,000 documents at SALT Research the main idea is to create an immersive installation with architectural intelligence to reframe memory, history and culture in museum perception for 21st century through the lens of machine intelligence.

SALT is grateful to Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program, and Doğuş Technology, ŠKODA, Volkswagen Doğuş Finansman for supporting Archive Dreaming.

Location : SALT Gatala, Istanbul, Turkey Exhibition Dates : April 20 - June 11 6 Meters Wide Circular Architectural Installation 4 Channel Video, 8 Channel Audio Custom Software, Media Server, Table for UI Interaction

For more information: refikanadol.com/works/archive-dreaming/ _________ Credits:

SALT Research Vasıf Kortun Meriç Öner Cem Yıldız Adem Ayaz Merve Elveren Sani Karamustafa Ari Algosyan Dilge Eraslan _ Google AMI Mike Tyka Kenric McDowell Andrea Held Jac de Haan _ Refik Anadol Studio Members & Collaborators Raman K. Mustafa Toby Heinemann Nick Boss Kian Khiaban Ho Man Leung Sebastian Neitsch David Gann Kerim Karaoglu Sebastian Huber

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

stimuli_Archive Dreaming by Refik Anadol // Commissioned to work with SALT Research collections, artist Refik Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among 1,700,000 documents. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives are, in turn, translated into an immersive media installation. Archive Dreaming, which is presented as part of The Uses of Art: Final Exhibition with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union, is user-driven; however, when idle, the installation "dreams" of unexpected correlations among documents. The resulting high-dimensional data and interactions are translated into an architectural immersive space. Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist for Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence Program where he closely collaborated with Mike Tyka and explored cutting-edge developments in the field of machine intelligence in an environment that brings together artists and engineers. Developed during this residency, his intervention Archive Dreaming transforms the gallery space on floor -1 at SALT Galata into an all-encompassing environment that intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges immutable concepts of the archive, while destabilizing archive-related questions with machine learning algorithms. In this project, a temporary immersive architectural space is created as a canvas with light and data applied as materials. This radical effort to deconstruct the framework of an illusory space will transgress the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library and the conventional flat cinema projection screen, into a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive visualized with machine learning algorithms. By training a neural network with images of 1,700,000 documents at SALT Research the main idea is to create an immersive installation with architectural intelligence to reframe memory, history and culture in museum perception for 21st century through the lens of machine intelligence. SALT is grateful to Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program, and Doğuş Technology, ŠKODA, Volkswagen Doğuş Finansman for supporting Archive Dreaming. Location : SALT Gatala, Istanbul, Turkey Exhibition Dates : April 20 - June 11 6 Meters Wide Circular Architectural Installation 4 Channel Video, 8 Channel Audio Custom Software, Media Server, Table for UI Interaction For more information: http://www.refikanadol.com/works/archive-dreaming/ _________ Credits: SALT Research Vasıf Kortun Meriç Öner Cem Yıldız Adem Ayaz Merve Elveren Sani Karamustafa Ari Algosyan Dilge Eraslan _ Google AMI Mike Tyka Kenric McDowell Andrea Held Jac de Haan _ Refik Anadol Studio Members & Collaborators Raman K. Mustafa Toby Heinemann Nick Boss Kian Khiaban Ho Man Leung Sebastian Neitsch David Gann Kerim Karaoglu Sebastian Huber

0 notes

Text

SALT 2017’de sekiz araştırma projesini destekleyecek http://ift.tt/2nlkJzc

SALT Araştırma Fonları bu yıl, Dr. Mehmet Bozdoğan’ın (1922-2015) anısına ikinci kez verilecek iki ek fonla sekiz araştırmacının projesine katkı sağlayacak. Türkiye’nin ilk radyoloji uzmanlarından olan ve çok sayıda öğrencinin eğitimini üstlenen Dr. Bozdoğan’ın kızları Sibel ve Hande Bozdoğan’ın desteğiyle sayısı altıdan sekize çıkarılan projelere toplam 80.000 TL’lik fon verilecek.

SALT Araştırma Fonları’na ön başvurular sonucu, bu yıl toplam 205 projeden 155’i kabul aldı. Daha kapsamlı olan ikinci aşama başvurular, 20 Mart Pazartesi saat 18.00’e kadar sürecek. Prof. Dr. Elvan Altan (Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi), Doç. Dr. Ahu Antmen (Marmara Üniversitesi), Vasıf Kortun (SALT Araştırma ve Programlar), Prof. Dr. Nadir Özbek (Boğaziçi Üniversitesi) ve Lorans Tanatar Baruh’dan (SALT Araştırma ve Programlar) oluşan seçici kurulun belirlediği projeler 22 Nisan Cuma günü duyurulacak.

SALT Araştırma Fonları, Türkiye’de görsel pratikler, yapılı çevre, sosyal yaşam ve ekonomik tarih alanlarında özgün belge edinimi ve araştırma projelerini destekler. Ayrıca, SALT Araştırma bünyesindeki birikimlerin değerlendirilmesine katkıda bulunur.

from Aeroportist I Güncel Havacılık Haberleri http://ift.tt/2mBI4N7 via IFTTT

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Archive Dreaming from Refik Anadol on Vimeo.

Commissioned to work with SALT Research collections, artist Refik Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among 1,700,000 documents. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives are, in turn, translated into an immersive media installation. Archive Dreaming, which is presented as part of The Uses of Art: Final Exhibition with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union, is user-driven; however, when idle, the installation "dreams" of unexpected correlations among documents. The resulting high-dimensional data and interactions are translated into an architectural immersive space.

Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist for Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence Program where he closely collaborated with Mike Tyka and explored cutting-edge developments in the field of machine intelligence in an environment that brings together artists and engineers. Developed during this residency, his intervention Archive Dreaming transforms the gallery space on floor -1 at SALT Galata into an all-encompassing environment that intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges immutable concepts of the archive, while destabilizing archive-related questions with machine learning algorithms.

In this project, a temporary immersive architectural space is created as a canvas with light and data applied as materials. This radical effort to deconstruct the framework of an illusory space will transgress the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library and the conventional flat cinema projection screen, into a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive visualized with machine learning algorithms. By training a neural network with images of 1,700,000 documents at SALT Research the main idea is to create an immersive installation with architectural intelligence to reframe memory, history and culture in museum perception for 21st century through the lens of machine intelligence.

SALT is grateful to Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program, and Doğuş Technology, ŠKODA, Volkswagen Doğuş Finansman for supporting Archive Dreaming.

Location : SALT Gatala, Istanbul, Turkey Exhibition Dates : April 20 - June 11 6 Meters Wide Circular Architectural Installation 4 Channel Video, 8 Channel Audio Custom Software, Media Server, Table for UI Interaction

For more information: refikanadol.com/works/archive-dreaming/ _________ Credits:

SALT Research Vasıf Kortun Meriç Öner Cem Yıldız Adem Ayaz Merve Elveren Sani Karamustafa Ari Algosyan Dilge Eraslan _ Google AMI Mike Tyka Kenric McDowell Andrea Held Jac de Haan _ Refik Anadol Studio Members & Collaborators Raman K. Mustafa Toby Heinemann Nick Boss Kian Khiaban Ho Man Leung Sebastian Neitsch David Gann Kerim Karaoglu Sebastian Huber

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Archive Dreaming from Refik Anadol on Vimeo.

Commissioned to work with SALT Research collections, artist Refik Anadol employed machine learning algorithms to search and sort relations among 1,700,000 documents. Interactions of the multidimensional data found in the archives are, in turn, translated into an immersive media installation. Archive Dreaming, which is presented as part of The Uses of Art: Final Exhibition with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union, is user-driven; however, when idle, the installation "dreams" of unexpected correlations among documents. The resulting high-dimensional data and interactions are translated into an architectural immersive space.

Shortly after receiving the commission, Anadol was a resident artist for Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence Program where he closely collaborated with Mike Tyka and explored cutting-edge developments in the field of machine intelligence in an environment that brings together artists and engineers. Developed during this residency, his intervention Archive Dreaming transforms the gallery space on floor -1 at SALT Galata into an all-encompassing environment that intertwines history with the contemporary, and challenges immutable concepts of the archive, while destabilizing archive-related questions with machine learning algorithms.

In this project, a temporary immersive architectural space is created as a canvas with light and data applied as materials. This radical effort to deconstruct the framework of an illusory space will transgress the normal boundaries of the viewing experience of a library and the conventional flat cinema projection screen, into a three dimensional kinetic and architectonic space of an archive visualized with machine learning algorithms. By training a neural network with images of 1,700,000 documents at SALT Research the main idea is to create an immersive installation with architectural intelligence to reframe memory, history and culture in museum perception for 21st century through the lens of machine intelligence.

SALT is grateful to Google's Artists and Machine Intelligence program, and Doğuş Technology, ŠKODA, Volkswagen Doğuş Finansman for supporting Archive Dreaming.

Location : SALT Gatala, Istanbul, Turkey Exhibition Dates : April 20 - June 11 6 Meters Wide Circular Architectural Installation 4 Channel Video, 8 Channel Audio Custom Software, Media Server, Table for UI Interaction

For more information: refikanadol.com/works/archive-dreaming/ _________ Credits:

SALT Research Vasıf Kortun Meriç Öner Cem Yıldız Adem Ayaz Merve Elveren Sani Karamustafa Ari Algosyan Dilge Eraslan _ Google AMI Mike Tyka Kenric McDowell Andrea Held Jac de Haan _ Refik Anadol Studio Members & Collaborators Raman K. Mustafa Toby Heinemann Nick Boss Kian Khiaban Ho Man Leung Sebastian Neitsch David Gann Kerim Karaoglu Sebastian Huber

0 notes

Text

Kurum Soruları

Vasıf Kortun

Sergiler, doğaları gereği kırılgan, kusurlu ve elden kayıveren araçlardır. Hikâye anlatmada pek de verimli değildirler. Raftan alıp roman gibi bir bölümünü okuyarak kenara koyamaz; video gibi yarısından başlayıp oynatamaz veya geri saramaz; dans figürü gibi ardı ardına tekrarlayamazsınız. Bir tiyatro oyunundaymışçasına göz önüne serilmeleri de o kadar önemli değildir, zira -siz orada olmasanız dahi- hep oradadırlar.

Sergiler kapandıklarında da, ancak olmadıkları bir şey olarak hatırlanabilirler. Sorun değil tabii ki. Zamanın kendisine dair olmayan, zaman aralıklarıyla art arda gelen bir pratik olarak biteviye bir biçimde yer değiştirirler. Biri kapanır, diğeri açılır; mağazalarda satılan sıradan nesneler gibi, “yeni sezon” ve “haftaya son” duyurularıyla kesintisiz bir programlamanın raf ömrü sınırlı ögeleridir. Çoklukla fikir ve olasılıkları paketleyip tam da işlemeden, tüketmeden eskitirler. Oldukları kadardırlar. Daimî de olabilirler, yani koleksiyon sergileri gibi uzun süreye yayılabilirler ama bu tür sergiler daha başlamadan bayattır zaten.

Bu fikre bir başka katman ekleyelim: Geç kapitalizm zamanında, zamanımızda, geç kapitalist sergi model ve pratikleri var oldukları zamana dair ve o zamana ait olmak üzerineyse, içerisinde bulunduğu zamana bakan kurumlar güncel olabilir mi? Tabii ki hayır. Güncellik, yaşadığı zamanla derdi olanlara mahsustur; arızası olmayan güncel değildir, muhakkak ki her arızası olan da ama zamana uyumlanan asla güncel olamaz, yalnızca zamanının içerisinde mevcudiyet gösterir. Yeni olan ise bambaşka bir konu; yeni sevicilik [neofili] az çok tahmin edip öngörebileceğimiz bir farklılıktır. O anda öngöremeseniz bile, geriye dönüp baktığınızda aslında gayet tahmin edilebilir olduğunu ayırt edersiniz. Çünkü neofili, çıpasını bildik ortamından çok uzağa bırakmaz, semantiği bozmaz.

Mevcudiyet [zamanının öznesi olmak, orada mevcut bulunmak, varlığını sunmak], kapsamlı bir analiz olasılığını üstünkörü muameleler lehine ezer ve kurumsallaşmış bir durumu yansıtır. Söz konusu olan, kurumun kendisi değil, programıdır. Yani kurum, taahhüt ettiği eylemler aracılığıyla, taahhüt ettiği pratikler üzerinden yapısının değişmesine izin vermez; değişen, yalnızca değişmesi beklenendir, programdır.

Çoğu kurum, yerel ve uluslararası şöhret yarışı içerisinde geçmiş ve geleceğini tüketiyor. Oysa, bir geçmiş ve mirası sürdürmek, bir gelecek yönelimi ve tahayyülüne sahip olmak çok daha değerlidir. Çünkü, içerisinde var olduğumuz, düşündüğümüz, ürettiğimiz zaman, geçmiş ve geleceklerin yörüngesindedir. Walter Benjamin’in ifade ettiği üzere; “Geçmişin dayatması, yaşamın gömülü geleceklerinin tohumlarını şimdiki zamanda yeşertmeye dair kaçınılmaz talebinden ötürüdür”. Bu da, üç farklı kamuya karşı sorumluluğu gerektirir: Şu anda mevcut olan kamu, tüm sıkıntı ve arızalarıyla geçmişten gelen kamu, gelecekteki kamu. Kurum, bunlardan birine ayrıcalık göstermeden çoğulluğu görmek durumundadır. Miras devralan ve devreden kurumların birincil vazifesi, insanlara görüşlerini oluştururken daha iyi karar vermelerine yardımcı olacak araçlar sağlayabilmek ve devraldığımızdan daha mükemmel bir dünyayı geleceğe teslim etmektir.

Şimdi biraz geri saralım...

Müzeler, 1970’lerin sonundan itibaren, sürekli artan ekonomik yoksunluk koşullarına maruz kaldı. Sağlık ve eğitim alanlarında olduğu gibi, ufukta beliren turbo kapitalizmin volelerine karşı bağışıklıkları yoktu. Birçoğu, dalga dalga gelen tehditleri savuşturmak üzere, yeni oluşan durumdan yararlandı ve zamanın temsilî kurumlarına benzedi. İş geliştirme ekipleri oluşturdular; deneyim yönetimini, içerik yönetiminin önüne aldılar ve “varlık yönetimi” gibi olmadık işler uydurdular. İçkin yetenek ve kapasitelerini pazar yerine sunan servis sağlayıcılarına dönüştüler; kendilerini sağlama almak üzere, tarihten edindikleri kimlikleri markalara çevirdiler; markalaşıp markalarını pazarladılar. Nihayetinde, kurumları marka yönetiminden ibaret oldu. Geleneksel olarak geniş tabanlı, sivil ve yerleşik olan orta sınıfın desteğine sırt çevirip seçkinlere el açtılar ve değiştiler, çok değiştiler. Görünürde becerikli, esasen beceri kaybına uğrayan neoliberal operasyonlar hâline geldiler.

Kurumun zamanı nasıl yeniden biçimlenebilir? Üç farklı kamuya karşı sorumlu olmak gibi, üç farklı zaman içerisinde var olmaya dair farkındalık önemlidir. Sergiler “şimdiki zaman”da gerçekleştirilir ancak, kurum geçmişten, çözülememiş ve görmezden gelinmiş, devreden çıkarılarak gizlenmiş hikâyeleri de taşıyan bir “miras makinesi”dir. Yapabileceği, bunları müzakere etmek, denemek ve deneyimletmek, mayalamaktır. En iyi ihtimalle de, olası gelecekleri sorgulamaktır. Zira üç zaman iç içe geçmiş, birbirine örülüdür; şimdiki zamanda yapılan bir müdahale geçmişi ve geleceği de değiştirir.

Geçtiğimiz günlerde, Ford Foundation [Vakfı] Başkanı Darren Walker’ın bir konuşma metnini okudum. Şöyle demiş Walker: “Ben şanslıydım. Doğru bir büyükanneye sahip olduğum için şanslıydım. Şansıma, büyükannem doğru bir evde hizmetçi olarak çalıştı. Şansıma, o evde çeşitli sanat dallarına ilgili, doğru dergilere abone olan, doğru bir zengin aile yaşamaktaydı. Şansıma, aile üyeleri, elden çıkarmak istedikleri dergi ve program broşürlerini bana vererek sevgilerini gösterdi.”

Kurumun görevi, devraldığı dünyadan daha iyisini savunmak, ileriye daha iyi bir miras bırakacak insanların çoğalmasına katkı sağlamak kadar basittir. Yani, kurumlar dünyayı değiştirmez ama dünyayı değiştirebilecek insanların yaşamlarına dokunurlar. Bu, en temel seviyede, bilgiye, müşterek kaynaklara, sağlık ve eğitim gibi zaruri hizmetlere herkesin engelsiz hak sahibi olduğu ve eriştiği; tür ve cinsiyetlerin eşit görüldüğü; ekolojisi tamir edilmiş ve lügatı geri kazanılmış bir dünya... Hedef büyük ama eşlikçisi soru da gayet net: “Şimdi değilse ne zaman, hepimiz değilsek kim?”

Peki, kurum ne şekilde güncel olabilir? Bir yöntem, aynı anda saydam ve opak olmayı bilmekten geçer. Kamu tefekkürüne değin en şaşırtıcı katkılar, buyurganlığın tehditkâr bakışlarından, cüheladan, paylaşılan yarı gerçeklerden ve popülistlerden uzakta mayalanmış, müzakere edilmiş ve denenmiştir. Büyük hareketler sokak ortasında değil, masanın çevresinde pişer. Dolayısıyla kurum, bir kilise kadar açık, bir manastır kadar kapalıdır. Ancak, sırf ehil kişilerin kabul gördüğü, kiliseye benzeyen bir manastır veya tam tersi olmamalıdır. Kurumlarda şeffaflık yanlış anlaşılmış, bir sanrıya indirgenmiştir. Aynı anda saydam ve opak olmak, sadece ve sadece performatif veya revolüsyoner bir durumda çakışır ve bunlar -çok iyi bildiğimiz gibi- kalıcı olmaz.

Bir kurum olarak müze, turbo kapitalizme gömülü olmakla birlikte kapitalist değildir. Ne var ki, var olduğumuz dünya hegemoniktir. Ticari şirketlerin ortalama ömrü bir yüzyıldan azken misal üç yüzyıldır ayakta duran ve çoğu devletten, ekonomik veya politik sistemden yaşlı müzeler bulunmaktadır. Yeni yönetim biçiminin özünde, giderlerin kısılması ve verimlilik araştırmaları yatar. Belirli varlıklar parasallaştırılırken, diğerleri gereksiz yükümlülükler olarak değerlendirilir. Koleksiyondaki kimi eserlerin kiralama bedeli yükseltilir, kimileri de talep olmaması nedeniyle elden çıkarılır. Peki, giderler nereden kısılır? Araştırma ve küratörlük birimleri küçültülür, sözleşmeli hizmetlere ağırlık verilir, içeride geliştirilen bilginin yerini dış kaynak kullanımı alır. Ancak, verimliliği artırma yöntemleri sürekli artan kurumsal hatalara da yol açabilir. Gereğinden büyük iş geliştirme ve konuk hizmetleri ile halkla ilişkiler gibi asal olmayan birimler, içerik yönetimine müdahale etmeye başlar. Varlık yönetimi tam da budur, aslen neyin varlık olduğunu bilmeyenlerin yönetimidir. Bu paradigma dönüşümüyle kurum, mevcudiyet arzusuna teslim edilir, şimdiki zamana öncelik ve ayrıcalık verilir. Geç kapitalizm, geçmiş ve geleceğin dışına yerleştirilmiş, hayal ve endişenin törpülendiği bir hazır zamanda yaşamamızı talep ederken, kurumlarda ufuksuz bir şimdiki zaman yönetimi ağırlık kazanır.

Hâlihazırda şen olmak için pek neden yok. Türümüzün en fazla yarım yüzyıllık ömrü kaldı. İnsan, yaşayan veya atıl duran her şeyi bir tür kaynak veya atık olarak algılıyor. Böylesi hızla akan bir zamanda, kurumların kurtuluştan ziyade problemin bir parçası olduğunu anlamak o kadar da şaşırtıcı olmamalı. Zira, artık geride bıraktıkları tarihî konum ve ağırlıkları bir yana, kurumlar dönüşüm yerine geçici şifa ve çarelere ilgili oldukça durum gitgide fenalaşacak.

Kamu ile özel ayrımı ve ‘kabile çıkarları’

Kamu ve özel arasında yapılan, neredeyse anlamsızlaşmış ayrıma kuşkuyla bakılmalı. Ortada bir mesafe veya etik üstünlük olmadığı gibi, ikisinde de aslında “kabile çıkarları” hâkim. Bu nedenle kurumları, -kamu ya da özel fon desteği fark etmez- özelleştirilmiş çıkarlara hizmet edenler ve o çıkarlar adına hareket edenlerden ayırmak şart. Zaten bugünün kurumlarının, ne içerik üreticisinin yanında olduğu ne de kamu yararına hareket ettiği söylenebilir. Jargon ve ifadeleriyle eylemleri arasında keskin bir çelişki var.

Bir çaresizlik hâli söz konusu; mevcut durumdan ıstırap çekiyor ama onu dönüştürmeye veya bir ders çıkarmaya yanaşmıyoruz. Başımıza gelenleri tetkik edemiyor ve tarihî konumumuzu koruyamıyoruz. Kazanılmış menfaatlere tutunmaktan öte, kurumun illa da hayatta kalması gibi tuhaf bir gerekçeden ötürü yeterince net olamıyoruz. Oysa, müstehzilik, olanı olduğu gibi kabulleniş, bildik çalışma usulleri ve en kötüsü de diğerlerine benzeyişin makbulleştirildiği bu ortamda hayatta kalma bir marifet olmadığı gibi övülesi bir tutum ve davranış değildir; marifet, kayda değer olmaktır.

Sosyal hayat özelleştirilip bir tema parka, bir temaşaya dönüştürülürken kurumların rotasını demokratik bir yöne çevirmek gerekiyor. Chantal Mouffe’a göre daha büyük hedef, kurumları “hegemonyacı düzeni tartışan bir saha” hâline getirmektir. Ne var ki, hegemonya görünen bir yerde değil, gömülüdür; hegemonyayı dekolonize etmeden ve kendi konumlarımızı sorgulamadan kalıcı bir değişim beklenemez.

Müze dünyası, gitgide kamu erişimini engelleyen bir ilişkiler ağına gömülmektedir. Yani, pleb [halk] tüketimine sunulanlar, kamuya çıkmadan önce ve kamu sonrası bir sahada belirlenir. Sergi ve programlar gibi çıktıları tanıdık görünse de, kararların alındığı süreçler, birbirine benzer özel ve kamu bağlamlarından oluşan ve kendi kendini doğrulayan küresel bir ağda zihnen özelleştirilmiştir. Bir açıdan bakıldığında, bu model değişikliğinin tam olarak fark edilmediği görülüyor. 18. yüzyılın sonu ile 20. yüzyılın sonu arasında kendini yenileyen müze hikâyesi artık yok. Miras bu olsa bile, geri sarabileceğimiz koşullar olup olmadığı da belirsiz. Aslında, yeniden biçimlenen model kendi tarihinden beslenmiyor. Büyük kentlerdeki büyük müzelerin çoğu, İkinci Dünya Savaşı sonrasında oluşan orta sınıf tema parkları ile endüstriyel fuar kalıplarının tarihinden pek çok ögeyi barındırıyor. Birer tüketim cenneti ve keyif zamanı üreticisi olarak, Hindistan, Çin ve Güneydoğu Asya’nın yanı sıra “yeni diyarlar”dan “yeni izleyiciler”in katılımıyla gittikçe genişleyen bir turizm sınıfını öngörüyorlar. Öte yandan, bu kurumlara göre turizm yalnızca uzaklardan gelenlere yönelik değil, “yeni kentli”nin ta kendisi de bir turist olarak konumlanıyor.

‘Kuvvetsiz sosyalleşme’

Kamusallığın her yönünü içeren “kuvvetsiz sosyalleşme”yi, yeni agoralarda kendi arzusuyla bir araya gelen, tasarlanmış alanlarda önceden tayin edilmiş rollerini içkinleştiren bir topluluğun tüm yönleriyle deneyimi olarak tarifliyorum. Bu tür topluluklar, kapsayıcı bir yönetime tabidir ve aslen birer deneyimden ibarettir. Bir araya gelerek manalı bir mevcudiyete dönüşmezler. Yeni bir demokrasinin başlangıcına ya da potansiyel bir halk meydanı ya da hareketine işaret etmezler. Kendi kaderlerini tayin etmeye yönelik bir amaç veya araçları yoktur.

Yeni agoralar güzel mekânlardır. Mimarileri de çok meşhurdur. Bundan ötürü hemen markalaşırlar. Boş zaman, keyif ve turizm sektörleriyle örtüşürler. Markanın bilinirliği, tüketici istek ve ihtiyacıyla yüceltilir. Bu modelin hayatta kalmayı sürdürebilmesi, sürekli olarak gayrimenkul genişletilmesi ve inşaat gerektirir. Aksi takdirde sistem çökecektir. Geç kapitalist ekonominin birçok teşebbüsünde olduğu gibi, sürekli tüketimden kaynaklanan tükeniş kesin bilgidir. Yani, ölüm önceden planlanmış ve kaçınılmazdır ve hatta amaçlanmıştır.

Bu modelde en ufak bir paradoks dahi yoktur. Aynı sanatçılar, aynı mimari ofisler, çoğu zaman birbirinden ayırt edilemeyen aynı türde eserler, bir kurumdan ötekine aynı hiyerarşik anlatılar... Aşağı yukarı her şey birbiriyle uyumludur. Marka kentler dışındaki müzeler ise hızla çözülmeye devam etmekte; önlerinde karanlık bir senaryo durmaktadır. Onları destekleyen, tarihî nitelikte yerleşik destek sınıfları çözülmüş, sivil topluluklar güç kaybetmiştir. “Yeni destek sınıfı” sadece dikey düzenden anlar. Coğrafyaya aidiyeti yoktur, toprağa ayağı basmaz, zaman ve mekândan aridir. Londra, New York, Hong Kong, Dubai ve Bakü gibi; enerji ve silah piyasalarının dış kabuğu oluşturduğu, finans piyasalarının yoğunlaştığı “güç koridorları”na odaklanır. Beceri ve envanterlerini istediği yere park eder. Geçmişin yatay ve artık dağıtılmış olan destek sınıflarından farklı şekilde sayıca az, güç bakımından sınırsızdır.

İkincil kentlerin daha 15 yıl öncesinde kriz yaşamaya başladığı düşünülürse, bu tarihî dönüşümü öngörmek için dâhi olmak gerekmiyordu. Yine de, refah devletlerine doğanların, kaçınılmaz olarak içerisinde bulunduğumuz sıkıntılı ortamın süreklileşeceği fikrine teslim olması imkânsızdı; yaşanan cehennemin geçiciliğine kendilerini inandırdılar. İşte bu yüzden kurumlar, olası çözümlere yönelik çeşitli yöntemler geliştirip bunları denemek yerine, giderek daha anemik koşullar ve hatta iflasla sonuçlanan bir sabitlikte kalmayı tercih ettiler.

Müze, üniversite ve hastanelerin tıpkı birer şirket gibi, idari bir mantıkla yönetilmeye başlaması da aynı döneme denk gelir. Küratör ve eski müze direktörü David Elliott, SALT’ın kuruluş aşamasındaki bir uzman tartışmasında çok güzel bir uyarıda bulunmuştu: “Yönetim, belirli bir disiplin veya bilgiyle hiçbir ilgisi olmadan, kendi içerisinde bir beceri olarak yükselmiştir.”

Her ne kadar kurumlar, şirket birleşmeleri, yönetimi devralma, imtiyaz devri, idari merkezîleşme, uyumlama, belli varlıkları elden çıkararak sonlarını erteleme gibi stratejiler geliştirse de, maalesef bunların hiçbiri hakiki bir çözüm sunmuyor. Yönetsel yenileme, kurumları hasta eden zehri artırmak anlamına geliyor; işe yaramadığı hâlde aynı ilaç tedavisi tekrarlanıyor. Hem bu konu, yalnızca bir kurumun hayatta kalmasından ibaret değil. Kurumun kendini yeniden düşünmesi ve değişen zamanlar boyunca anlamlı kılması gerekiyor. Temel bir gerekliliği olmadan hayatta kalma çabası, kurumları kabile çıkarlarına karşı daha da savunmasız bırakıyor, şirazeden çıkarıyor.

‘Zombi kurumlar’

Kısa vadeli devalar, müzeleri “zombi kurumlar”a çevirmekle eş değer sayılabilir. Yani, kamu hizmetinde olması gereken müzeler, geç kapitalist ekonomide kapitalist olmayan kurumlar olarak sahaya indiklerinde, kamu desteğine sahip olmadıkları bir alana girerler. Burada, belirli bir süre için tasarlanmış sürdürebilirlik protokollerine uymak, verimliliklerini artırmak ve “hizmet verdikleri anın kulu olmak”la yükümlüdürler. Sorunun nüvesi, bu taban tabana zıt ekonomik modeller arasındaki gerilimin yanı sıra, tarihsel kamu kurumu ile geç kapitalizmin, kamu menfaati anlamında tümüyle farklı fikirlere sahip olmasına dayanır.