#Ursuline Bears

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ernestine Schumann-Heink as Waltraute; Bayreuth, 1899

Madame Shumann-Heink, the diva of Grossmont

Last of the Titans

Author: Richard W. Amero

Publish Date: Nov. 7, 1991

Madame Ernestine Schumann-Heink's life had the before-and-after quality of a fairy tale. She was born in poverty and achieved riches. She was plain in appearance yet had a regal and impressive bearing on the concert stage. She began her opera career modestly in Austria at age 15, but by the time she moved her family to San Diego, at 48, she was one of the most famous and revered women of her time, revered women of her time.

She was called "Tini" by her parents, "Topsy" by friends in Germany, "the Heink" by composer Gustav Mahler, "Heinke" by impresario Maurice Grau, and "Nona" by her children. Those who did not know her personally called her "Mother" or “Madame," reflecting the gratitude, tenderness, admiration, and respect she inspired.

She was born Ernestine Röessler at Lieben, near Prague (then part of Austria), June 15, 1861. Her mother was Italian-born Charlotte (Goldman) Röessler and her father Hans Röessler, a cavalry lieutenant in the Austrian army. She would later say she inherited her willfulness and "fighting qualities" from her father, whom she once referred to as “a real old roughneck," but it was her mother who inspired her to sing. Schumann-Heink would recall for a biographer, "When I was three years old, I already sang. I sang what my mother sang.... I’d put my mother’s apron around me and start to act and sing — singing all the different arias and dancing — always dancing."

The Röesslers confronted a life of continual want. An army salary could barely support a family of six. But the resourceful young Ernestine used her talents to supplement the family’s table. The diva told stories of charming a dour grocer into giving her some Swiss cheese and an apple in exchange for performing a traditional folk dance. If Ernestine had no music for a performance, she would whistle the tune herself.

When her father was posted at Krakow, Ernestine’s mother sent her off to convent school each day “with a big bottle of black coffee and a piece of dry black bread —butter was unheard of. That was all she could give me." But one day at lunchtime, Ernestine left the school grounds to explore the town’s marketplace. "I was only 11 years old then and delighted to run the streets — I did not fear anything — and perhaps it was all well and good, because it was the beginning of my independence."

At the market, Ernestine discovered an Italian circus:

They were just having the mid-day meal when I came along. Oh, how it smelled, so good! And I was so hungry — I was always hungry, you know. “Ach, what must I do to get some of that good food?” So I asked them, please, please could they give me something to eat — and I would work for it. They were astonished and roared at me with laughter and said, "Si, si! If you want to work, little one, clean the monkey cages first, then you can eat!” I suppose they didn’t think I’d really do it — they were just joking — but I did it. And what a meal they gave me! I was stuffed like a Strassbourg goose! And they began right away to like me.

Ernestine spent her afternoons working with the circus until her father was reassigned to Prague later that year.

Still only 11, Ernestine was sent to the Ursuline convent near Prague, where, though she could not read music, she sang the tenor parts in the Mass, which she had memorized by ear. Her impressive performance attracted notice, and she began taking formal music lessons. When she was 13, the family moved to Graz, where again Ernestine’s deep contralto voice impressed a retired diva, who gave her lessons at no charge.

At 15 Ernestine sang the contralto part in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in her first public performance. On the strength of that performance, the chorus’s soprano soloist suggested that Ernestine apply for a position with the Vienna Imperial Opera. But her hopes were dashed when the opera director, after her audition, sneered, "Why with such a face — no personality at all — how can you expect to succeed? My dear girl, you better give up the idea of singing and let the people who brought you buy you a sewing machine and set you to work. You will never be a singer."

Not long after the rebuff in Vienna, Ernestine was invited to try out for the Dresden Opera. After hearing her sing the demanding ‘‘O mon fils" from Myerbeer’s Le Prophète and "Brindisi" from Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia, the director engaged her at 3600 marks (about $900) a year.

In 1878 the 17-year-old contralto made her debut as Azucena in II Trovatore. Imbued with the high spirits and irreverence of youth, Ernestine said she had difficulty maintaining a straight face as she sang of throwing her child into the flames. It was at the Dresden Cathedral, where she sang to enhance her meager income, that Ernestine finally learned to read music.

In 1882 at 21, Fraulein Röessler married Ernst Heink, secretary of the Dresden Opera, though they did not first obtain the consent of management. As a consequence, she and her husband were dismissed.

In the fall of 1883, at the urging of a Dresden critic, the director of the Hamburg Opera awarded Frau Heink a contract to sing utility roles with the company for a few hundred marks a season. In the first four years at Hamburg, she sang only bit parts. During that time, she gave birth to August, Charlotte, and Henry. The expected arrival of a fourth child (Hans) proved too much for Herr Heink, who left mother and children to fend for themselves.

Frau Heink’s situation was desperate. When the sheriff took her furniture to satisfy her husband’s debts, she felt she had reached the end of her resistance. She resolved to throw herself and her children in front of a locomotive. She later said it was the voice of her little girl Charlotte saying, "Mamma! Mamma! I love you! Take me home!" that brought her to her senses.

Throughout this time, Ernestine continued to study and observe the work of the lead singers. At home, while nursing her babies, she diligently studied the major operatic roles.

A fellow performer soon asked her to sing at a benefit in Berlin. Still pregnant with Hans but desperate for money, she left her three children in a neighbor’s care and traveled all night by train. Arriving in Berlin early in the morning and unable to afford a hotel, she sat in a park until rehearsals began. Her performance as Azucena that evening made her a sensation.

Back in Hamburg, Ernestine’s director realized (if he had not known before) that he had a superstar in his opera company. When his leading contralto refused to perform one evening, he asked Ernestine to sing the role of Carmen. Though she had not studied the role, Frau Heink triumphed. It was true, as conductor Gustav Mahler pointed out, that she had memorized the faults as well as the singing of the many Carmens who had preceded her at Hamburg. Successes as Fidès in Le Propheète and Ortrud in Lohengrin followed. Before the season was over, 22-year-old Ernestine Heink was Hamburg’s leading contralto.

The singer later admitted that her relationship with Gustav Mahler was not cordial. Because Mahler did not pay attention to her as a woman, she spread the rumor that he was homosexual. In these salad years, Frau Heink’s impish impulses and headstrong temperament kept her from taking art or herself too seriously.

From 1887 to 1898, the ambitious Ernestine sang in festivals and concerts in Berlin, London, Sweden, Norway, and, beginning in 1896, at the famous Bayreuth Festival, training that broadened her vocal style. The singer’s increasing successes, her three-octave vocal range from low D to high B, and her self-assurance on the stage brought her dozens of feature roles in quick succession, including Amneris in Aida, Brängane in Tristan und Isolde, Katisha in The Mikado, Magdalene in Die Meistersinger, and Orsini in Lucrezia Borgia.

In 1892, at the age of 31, Ernestine divorced Herr Heink and married Paul Schumann, an actor and director of the Thalia Theater in Hamburg. Schumann taught his wife to interpret songs by speaking the words before she sang them. Her lifelong reputation for deft phrasing, pure diction, and thoughtful understanding of the content of lyrics owed much to her husband’s guidance.

Bruno Walter, assistant conductor to Gustav Mahler at the Hamburg opera during this era, recalled Schumann-Heink as a singer who combined remarkable talent with willful disposition. In spite of a tendency to resist, “She could be depended upon to use her gifts in a thoroughly artistic manner.” Critic George Bernard Shaw was captivated by her fine contralto voice and the power and passion of her delivery at the Bayreuth Festival in 1896 but was less taken by the summer gown and fashionable sleeves she wore under her blue-black Valkyrie armor as she sang Waltraute in Die Götterdaämmerung.

Schumann-Heink’s American debut took place in Chicago in November of 1898 in the role of Ortrud in Lohengrin. She was at the time a member of the Maurice Grau Opera Company, predecessor of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Company, and was on leave of absence from the Royal Opera House Company in Berlin. Four weeks after the première, she gave birth to a boy in the Belvedere Hotel in New York City. At the suggestion of the doctor who assisted in the birth, she named her newest son George Washington Schumann. Her children eventually would number eight, including four by Heink (August, Charlotte, Hans, and Henry); George, Ferdinand, and Marie, her children by Schumann; and Walter, Schumann’s son from a former marriage.

Her Metropolitan Opera debut as Ortrud took place just one month later, in January of 1899. The critic for the New York Tribune said that though her high register was not as beautiful as her low, she won admiration for her thrilling use of tonal color and her ability to depict a character who was “half woman, half witch and all wickedness personified.”

In London that summer, she appeared before Queen Victoria in a condensed version of Lohengrin at Windsor Castle. Afterward, the Queen told her in German how much she liked her voice. In a bluffer manner, Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) asked her how she could have so many children and still find time to sing. Schumann-Heink was piqued but made no reply.

In 1904, Schumann-Heink left the Metropolitan and the world of opera to tour in a musical comedy, Love's Lottery. Her new manager promised her an income at the improbable figure of $240,000 for 40 weeks’ work plus a share of the gross receipts. Because her English was stilted and her accent heavy, her role as a German washerwoman in love with an English sergeant elicited much amusement from audiences.

Most critics were restrained in their comments, but Leslie's Weekly scored the singer’s presentation. “Madame Schumann-Heink is not an unalloyed joy. Her comedy is pathetically heavy and her one idea of humor (?) is to mock her own broken English by saying repeatedly, ‘Ist mein English goot?’ ”

In answer to those critics who deplored her desertion of grand opera, Schumann-Heink said she did it to get enough money to bring her ailing husband and her children to the United States. But Paul Schumann died in Germany in November of 1904.

The following February, Schumann-Heink took out United States naturalization papers in Cincinnati, and in May, at 43, she married William Rapp, Jr., a Chicago lawyer. He was her business manager and 13 years younger than she.

An attack of tonsillitis forced the diva to close her season with Love’s Lottery in November of 1905. Physicians had told her that she would lose her voice permanently if she continued to sing in that role.

Early in 1906, the diva returned to Germany, where she succeeded in getting six of her eight children out of the country. According to German law, Schumann-Heink, by marrying a foreigner, had forfeited her property in Germany. Also, her boys were required to serve in the army before they could leave the country. The German courts finally decided the boys could accompany her to America and that she could retain one-third of the money in Germany since she, not her deceased husband, had earned it. Her home in Germany was confiscated, and she had to buy it back. Her two oldest children, Charlotte and August, remained in Germany. For the next five years, Ernestine, her husband, and six children lived in northern New Jersey.

After getting her children settled, Schumann-Heink left for Bayreuth in July 1906. Concerts followed in Munich and Paris. Returning to the United States in October, she began a concert tour that ended on March of 1907 with appearances in Die Walküre at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. A review in the New York Sun implied that nothing had changed:

She has all her old merits, all her old faults. She still indulges occasionally in bad attack, in spasmodic and ejaculatory phrasing in cantabile passages, and in failures to take certain intervals faultlessly. But, on the other hand, she has still the splendor of tone, the magnificent sweep of utterance and the stimulating appearance of reserve power which made her singing a constant joy in days now well remembered.

Schumann-Heink was then enticed by Oscar Hammerstein I to join his Manhattan Opera Company for its second season. Eventually, the mercurial Oscar decided that the three prima donnas he had engaged, including Ernestine, were costing him too much money, and he maneuvered to get rid of them. Schumann-Heink sang only one performance, that of Azucena in Il Trovatore in January of 1908. She was idle for the rest of the season and appears to have made up her losses by an extended European tour.

In a 1909 performance as Klytemnestra at the Dresden première of Richard Strauss’s Elektra, Schumann-Heink complained that the vocal parts were “a thunderous medley of groans, moans, and sighs” and feared she had harmed her voice. Strauss, on his side, was disappointed with her wooden acting and Wagnerian style of declamation. A short while later, she sang a much less demanding program of songs in a performance before Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Schumann-Heink was now a wealthy woman. Money coming in from recitals, opera appearances, and recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company went out in investments in stocks, bonds, and real estate.

In January 1910, while on a tour of the Pacific coast, the diva decided to live part-time in Grossmont, then an undeveloped tract of land north of Mt. Helix in eastern La Mesa. Local businessman Ed Fletcher and William B. Gross, a former actor and producer, owned this land, but Fletcher managed its development. He sold Schumann-Heink 500 acres of choice land for $20,000. Besides a lot near the top of Grossmont, the purchase included a 14-acre orange and lemon grove and several acres in El Cajon on which a stand of eucalyptus trees was to be planted.

This 1910 visit was a turning point in the diva’s life. With the land purchase, she could now provide homes for herself and her adult children, and, though she did not state this publicly, she could control their destinies.

William Rapp, the singer’s husband, opposed her plan to perpetuate her children’s dependency, but Schumann-Heink put the matter bluntly. “I do not see why my children should work hard when I have plenty to provide for all of them. I do not want them scattered. I want all of them near me all the time.” In December 1911, Rapp left the New Jersey home, and the next month his wife announced her intention to sue for divorce. Before their divorce became final, there was a bitter trial at which each accused the other of adultery.

“Casa Ernestina,” the Grossmont home, was designed by architect Dell W. Harris of San Diego. It cost about $7000 to build and was ready for occupancy in 1913. It consisted of a basement foundation of granite rubble, a plaster-walled main floor, and a roof of red cement tile. On the north side of the living room, French doors opened onto a terrace commanding a view of El Cajon Valley and the mountains.

Son Hans Schumann-Heink moved onto a 15-acre ranch on the slopes of Grossmont where he planted orange, lemon, and olive trees. He eventually took over a 40-acre ranch near Lakeside, used to raise hogs and grow fruits and vegetables. Ferdinand assumed the management of a cattle ranch in Imperial Valley and a butchering business in El Cajon. Daughter Marie, who had accompanied her mother on visits to Grossmont, married Hubert Guy of San Diego in 1915.

With the coming of Schumann-Heink to Grossmont, local reporters played up her image as a devoted mother. This tribute is one of many paid to the diva:

Madame Schuman-Heink is above all things else the mother, the great-hearted woman, who has risen above the petty struggles, above the heart-aches and reverses and at the prime of her life is surrounded by loving children, eight in all, whose adoration for the "little mother” is the strongest thing of their lives.

Along with her image as loving mother, the singer fostered an image as patriotic American by flying a large American flag over her various homes and by proclaiming her love for America at every opportunity: “I love America and I love Americans. I cannot tell you how much I love them, the great-hearted people, and they love me. I want my children to be Americans, to marry Americans and to live in America.”

The Schumann-Heink without whom the others would not exist was Schumann-Heink the artist. She knew her talent required care and exercise. By the time she came to Grossmont, she had developed her repertoire and style and did not change them thereafter except to include patriotic and sentimental songs in English that appealed to ordinary people. She wanted to sing before large audiences and insisted the price of admission to her recitals be as low as possible.

She did not employ a press agent because she was a master of the art of public relations. Upon her well-publicized arrival in any new town, she would wait for a large body of citizens to gather round. Then, spreading her arms wide, she would proclaim: “Dis is my town. Here I am at home!”

During a Midwestern tour on the Chautauqua circuit, a manager wanted to cancel one of the diva’s performances because a rainstorm had kept crowds at the tent shows very small. His gate receipts would not cover his costs. Schumann-Heink declared she would make up the loss out of her own pocket. Her reason was very practical. ‘‘If you stay in this business, is one thing to learn. Never let them lose money on you. If Schumann-Heink go out now and sing like the angel and that man, he lose money, then Schumann-Heink, she no good! Her voice, it is kaput. But If Schumann-Heink go out and sing off key and the management make money, then he tell everybody, Schumann-Heink, she sing like the angel.”

As soon as she was settled in Grossmont, civic leaders asked her for endorsements. Did she favor bonds for the upcoming Panama-California Exposition? Her first answer was wary. “Is it a check you want?” Then she gave the hoped-for response. “If the exposition will bring people to San Diego and the bonds are necessary to the exposition, I am for the bonds.”

Following a bout of pneumonia in late 1914, the singer resolved to spend 1915 in San Diego resting. But such interludes were rare. While she was relaxing, the Panama-California Exposition declared March 22, 1915, “Madame Schumann-Heink Day.” Some 6000 schoolchildren sang “America” before the diva at the organ pavilion in Balboa Park, and Mayor Charles O’Neall presented her with an honorary citizenship. In return, she promised to give a free concert at the exposition in June. For the nearly 27,000 people who gathered at the pavilion on June 27, it was the event of the year. As the San Diego Sun remarked, “The greatest organ, the greatest voice, the greatest chorus, the greatest outdoors on earth ... she’s golrious [sic].”

San Diego’s honorary citizen gave a concert as good as any she might present in New York. She sang 11 songs — German lieder, art songs, and popular tunes — and ended the concert with the audience joining her in “The Star Spangled Banner.” Since Schumann-Heink didn’t know the words to this song at the time, she sang the notes of the scale instead, mystifying listeners, who wondered what language she was singing.

In October, son Henry, who was a city recorder at Paterson, New Jersey, was charged with embezzling funds. His mother made good the missing money, and the matter was dropped. The following year, stepson Walter Schumann would be arrested in New York City on a charge of burglary. The New York Times would not mention Schumann-Heink in connection with the case or report subsequently how it was resolved.

In December of 1915, Madame Schumann-Heink learned that her son Hans was ill with lobar pneumonia. She rushed from San Diego to Chicago to be with him. When it seemed he might recover, she returned to sing at the reopening ceremonies for the second year of the Panama-California International Exposition on the afternoon of January 1, 1916. The respite ended on January 5, when Hans died. His ashes were placed in a columbarium in Greenwood Cemetery in San Diego.

At midnight, January 1, 1917, the diva sang “A Perfect Day” by Carrie Jacobs Bond and “Auld Lang Syne” at the closing of San Diego’s exposition. She was presented with a jewel made of stones found in San Diego County, which had been engraved, “To our beloved Schumann-Heink from the San Diego Exposition, 1915-1916.”

Later in January, the singer announced a plan to make the Spreckels Organ Pavilion in Balboa Park the setting for a summer festival rivaling Bayreuth’s. To get things moving, she donated $10,000. The San Diego Union went into ecstasies:

The establishment of this ‘American Bayreuth’ will bring in its train a host of the collateral arts, all drawn after their sister muse to a city preeminently fitted by climate, scenery and the temperament of its inhabitants to stand as a monument to the things that make life worthwhile.

It is doubtful the diva’s plan could have been realized because of the inadequacy of the pavilion for the purpose intended and because of the remoteness of San Diego from the population centers of the United States. In any case, the United States’ declaration of war against Germany in April of 1917 brought plans for cultural improvement to a halt.

As an American of Austrian origin with a brother in command of an Austrian warship, a son in the German Navy, and two sisters living in Germany, Schumann-Heink found her love for her new country to be at variance with her love for her old. Anti-Germans spread the calumny that the singer had concealed gold on the grounds of her New Jersey estate to pay for espionage. Others claimed her gardener, William Besthorn, a former reserve officer in the German Navy and a naturalized CJ.S. citizen, was operating an outlaw radio station at Grossmont. This led the CJ.S. Department of Justice to post a guard outside her Grossmont home. The infuriated singer responded by posting a guard inside the grounds to watch the one outside. Eventually, both guards were called off.

Henry Schumann-Heink and George Washington Schumann joined the U..S. Navy. Ferdinand Schumann was a member of the U.S. Army 242nd Artillery at Camp Funston, Arizona; and Walter Schumann, Schumann-Heink’s stepson, was a cook in the New Jersey State Militia. Ferdinand was discharged from the Army after his lungs had been weakened by pneumonia. The transport George was on was torpedoed by a German submarine off the coast of France, but he survived. August, on submarine duty in the German Navy, was lost in 1918 when an American destroyer rammed his vessel in the English Channel.

In spite of her divided sympathies, Schumann-Heink became a champion of American defense, though she did not condone anti-German jingoism and continued to sing German songs during her recitals. When asked about her attitude toward the war, she responded, “Hatred is a horrible thing. I have read about all those awful things Billy Sunday has been saying. But he will not make American boys hate. They just don’t know how. It isn’t in them.” She counseled mothers, “Don’t write the boys anything but cheerful letters. They are going to face something worse than anything that is happening to them at home. Forget those little troubles and tell them you are proud of them and that you are happy because they are your boys.”

For the duration of American involvement, Schumann-Heink gave herself wholeheartedly to fundraising for Liberty Bonds, the Red Cross, the Knights of Columbus, the Young Men’s Christian Association, and Jewish War Relief and to entertaining soldiers and sailors.

Her visits to San Diego were no longer rest stops. She spent her time singing, reviewing troops, and dining with servicemen in Balboa Park, Camp Kearny, and North Island. She sang frequently at military events; 10,000 people attended her charity concert in Balboa Park; 15,000 heard her sing at a Red Cross fundraiser. And each Christmas, she sang in the program at San Diego’s municipal Christmas tree in Horton Plaza, followed by midnight Mass at Camp Kearny. She even said she intended to go to France to sing in the trenches and to work in canteens. Though some people still assert she made such trip, the U.S. Department of State would not let her go because she had sons in the service.

Madame Schumann-Heink was decorated with regimental colors and named an honorary colonel of the 21st Infantry Regiment. She responded, “These boys of the 21st are now my boys. I love them all and will be a mother to them.” Unscrupulous servicemen wrote letters to their self-proclaimed “mother,” asking her for money to tide them over imaginary emergencies.

San Diego was only one of many cities that benefited from the singer’s largesse. Her home in Chicago was converted into a canteen for servicemen. On one day in October of 1918, she sold $200,000 in Victory Bonds at five rallies in New York City.

When the war was finally over, her son George became a bookkeeper in San Diego, and Henry sold stocks and bonds. Ferdinand left ranching to seek work in the packing business or in newspapers (the indecisiveness was characteristic). Walter stayed in the East. An accommodating Schumann-Heink purchased the former home of William B. Gross at Grossmont for Henry and homes for George and Kaethe, widow of August, in San Diego.

During the first of 1919, the singer spearheaded a campaign for a memorial to be built by popular subscription for San Diego servicemen. This plan would involve lining Pershing Drive in Balboa Park with shade trees and monuments containing the names of those who died during the European war. There was much talk but little action. After a recital at the organ pavilion for the memorial fund, the exasperated promoter lectured her audience, “If you in San Diego who have conceived this great memorial would stop your scrapping among yourselves and advance in one body for the good of your beautiful city, what could you do! You have been first to recognize the honor due to our sainted dead. Let us continue in this spirit.”

In 1921, Schumann-Heink performed in the Far East — Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, Batavia, Manila, and Honolulu. One outdoor concert was noteworthy because of thousands of bats flying about, some close to the singer’s head, all busily eating mosquitoes. “It’s fine,” the bemused singer remarked, “as long as they don’t mistake me for a mosquito.” Wherever she went, she was applauded wildly, dined, feted, and showered with gifts.

Wishing to live closer to San Diego, the diva, in 1922, purchased a three-story gray stucco mansion in Coronado from John D. Spreckels. During a visit to San Diego the same year, she began giving concerts to benefit the Rest Haven Home for children. The following year, 30,000 San Diegans heard her sing in the city’s memorial concert on the death of President Harding.

During 1926, Schumann-Heink, then 65, began a series of national radio broadcasts and, remarkably, returned to the Metropolitan Opera in New York after a nine-year absence. She sang Erda in Das Rheingold, and, according to a critic writing in The Nation, “Her voice, though impaired in the heights, still rolled out, rich and controlled. And her art worked its old magic.”

In an interview for the San Diego Union in August of 1926, the aging singer announced she would retire from the opera and concert stages in 1928 and start teaching so she could pass on her art to others. She began her retirement tour that December in New York with her “Golden Jubilee” celebration, the 50th anniversary of her first appearance on the concert stage. She sang Erda’s warning from Das Rheingold and Waltraute’s narrative from Götterdämmerung with the New York Symphony under the baton of Walter Damrosch.

Good Housekeeping magazine, in January 1927, ran a series on the singer’s life, as told to Mary Lawton, which in the following year was published by the Macmillan Company as Schumann-Heink: The Last of the Titans. The remainder of 1927 and the greater part of 1928 were taken up with nationwide farewell concerts. In honor of what she said would be her final appearance at San Diego, a pilot from Rockwell Field flew over her Coronado home and dropped flowers.

No sooner were her farewell concerts over than Schumann-Heink reappeared on the stage. In June of 1928, the diva sang “The Star Spangled Banner” at the Republican National Convention, which led Will Rogers to remark he wished she could have sung Senator Fess’s keynote speech. (Schumann-Heink, incidentally, was a Democrat who campaigned actively for the election of Alfred Smith as President.) That same month, she appeared at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles; in August she sang in two appearances in San Diego.

Also in 1928, the singer deeded her estate at Grossmont to Mayor George E. Leach of Minneapolis, to be administered as a haven for disabled veterans of the world war. The gift was a way of saying thank you to the veterans who had drunk a toast to August, her “son who went down in the U-boat,” during a Schumann-Heink appearance in Minneapolis in 1923. The veterans never occupied the site, and in 1932 Schumann-Heink’s daughter Marie acquired the estate by paying back taxes and accrued expenses.

In the fall of 1928, a San Diego jury convicted Henry of using $3000 in securities deposited with his stock and bond firm as security for a personal loan. Henry’s theft of corporation funds led to the collapse of the firm and losses to customers of approximately $21,000. He was placed on probation on condition that he repay the stockholders the full amount of their losses. As she had done before, Schumann-Heink made good her children’s mistakes by paying Henry’s debt.

Letters from Schumann-Heink to Alfred Wuest, her realtor and friend, indicate that the diva was under no illusions about her son’s character. (About his womanizing, she once wrote, “What he is I know.... God will punish him and this rotten woman in time.... Elsie shall divorce him — not lament — he laughs at her, lowers her in the eyes of the world. All laughs.”) She rescued him from his financial predicament primarily to spare his wife and two children.

In January of 1929, at age 67, Schumann-Heink again appeared with the Metropolitan Opera as Erda in Das Rheingold. The New York Times wrote that by recognizing the limitations of her voice and by emphasizing tonality, sonority, and inflection, she was able to deliver the warning to Wotan in a masterly fashion.

To dispel any doubts, the contralto announced in February that 1929 would definitely be her last concert year. For the rest of the year, she performed, conducted master classes, appeared in radio broadcasts, and acted as opera counsel for the National Broadcasting Company. She also spent considerable time advising women, in magazine articles and speeches, to forgo politics, bobbed hair, smoking, unchaperoned dancing, lipstick, jazz, and bridge and to devote themselves to bringing up children.

The stock market crash of October 1929 wiped out the singer’s investments. To support her sons and daughters and their progeny and her several retainers, Schumann-Heink put aside whatever wishes she had to lead a relaxed life. At age 69, she joined a touring vaudeville company, Roxy and His Gang. In attempting to describe the attraction of a woman of 69 singing in vaudeville, a writer for the Boston Transcript asked ambiguously, “Is it not the chief glory of her final years that she can persuade us to take the full singing will for the diminished vocal deed?”

Her son Ferdinand had become addicted to morphine, presumably while being treated for pneumonia in the U..S. Army. Like Henry, he was inept at handling his finances and subject to temperamental outbursts. Ferdinand sent whining letters to Schumann-Heink, begging her to send him more money. (“We miss you we love you we adore you Mammy mine, and how we miss you, you can’t conceive it possible,” he once wrote to her.) To keep an eye on him, she began spending much of her free time in Hollywood, where Ferdinand worked as a writer and actor for the motion pictures.

In February 1931, Good Housekeeping magazine listed the singer as second in its list of outstanding contemporary American women (Jane Adams was the first). One reason for this selection was demonstrated shortly afterward, when Schumann-Heink publicly rebuked members of her audience for protesting the appearance of Chinese and Negro children in the dedication ceremonies of the Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento. Turning her back on the audience, she sang a lullaby for the children. Then she told the audience, “It is up to the war mothers to teach their children the love of law and not make a difference between black or yellow or brown or white skins. You make war among yourselves through your children.”

For the next two years, Schumann-Heink continued to sing in concerts and on the vaudeville circuit. A writer for the Long Beach Morning Star wrote of one performance, “It isn’t singing as much as talking to the people across the footlights in the most beautiful of tones. And between songs she stops to hold a conversation. And the crowd catches on and talks back.” Schumann-Heink told a reporter for the San Diego Union that she was making between $4000 and $6000 a month through appearances, instruction, and radio broadcasts. She gave this money, she said, to her children and grandchildren. She kept a chauffeur but had given up her secretary, maid, and house servants.

In 1935, at age 74, Schumann-Heink embarked on a new career as a motion picture actress, appearing as a music teacher in Here’s to Romance, produced by Fox Studios, in which she sang Brahms’s “Wiegenlied.” Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presented her with a three-year contract, and when the two studios filed suits against one another, the delighted actress exclaimed, “It’s very comic, this quarreling among the motion picture men who call me terrific, colossal, and gigantic — I think I don’t like that gigantic very much, hah?”

In a joking mood, Hollywood’s newest and oldest discovery confessed to a San Diego Union reporter that actor Wallace Beery was the love of her life, and although she did not wear makeup, for Wallace Beery she would put on lipstick.

Schumann-Heink eventually sold her home in Coronado and moved to Hollywood. She said she was not giving up San Diego and that she intended to buy a cottage near the Grossmont home of her daughter Marie Fox.

A Reader’s Digest article in April of 1936 described Schumann-Heink as eagerly anticipating her role as a poor grandmother in a film being made of Kathleen Norris’s story Gram. The grandmother in the story finds out after a fling at luxury that “money isn’t everything.” The article added that the former opera star had stopped giving away her earnings and that her youngest son George was managing her affairs.

But Schumann-Heink’s expectations never came to fruition. She was suffering from leukemia, and on November 17, 1936, at the age of 75 Madame Schumann-Heink died in her Hollywood home.

The passing of Schumann-Heink was mourned in newspapers in almost every nation in the world except Germany. Schumann-Heink had been outspoken against the Nazis and had credited her own success to her heritage from “her little Jewish grandmother.”

On November 20, Los Angeles paid its respects to Schumann-Heink with a funeral held in the clubhouse of Hollywood Post No. 23 of the American Legion. The American Legion and Disabled American Veterans stood watch over the body. In his brief remarks, the rabbi who assisted with the service said, “She was a grand old darling. That’s the word, Darling. There’s no use being highfalutin’ in this moment of our grief.” He went on, “She loved them all, white and black, American and European, Jew and Gentile. In this she showed herself a master in the greatest of all arts — the art of living.” At the conclusion of the services, her body was taken to Union Station and placed on an observation car. As the train rolled down to Santa Ana and San Clemente, American Legion honor guards stood silent and solemn facing the train.

At San Diego, a police motorcycle escort, a Marine band, and members of the American Legion and Disabled War Veterans escorted the casket from the Santa Fe Station to the funeral chapel. Seats in front of the casket were occupied by Gold Star Mothers, World War Mothers, and members of the auxiliaries of the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Disabled War Veterans. National Guardsmen from San Diego’s 251st Coast Artillery Company stood watch while a harpist and pianist played Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” Brahms’s “Wiegenlied,” and Bohm’s “Silent as Night.”

On November 21, the San Diego chapter of the Disabled American Veterans conducted a brief service then placed the casket in a hearse, and members of the family and representatives of the service groups followed it to Greenwood Cemetery. Here a military squad fired a volley and a bugler sounded taps as the body was taken to the crematory. The ashes were later placed in a niche, though not in the same columbarium with those of her son Hans.

In her will, Madame Schumann-Heink left her $34,000 estate to four of her six surviving children. Henry Schumann-Heink and Walter Schumann, having cost her emotional stress and exorbitant sums during her life, were left nothing.

On Memorial Day, 1938, Barbara Heink, granddaughter of the diva, unveiled a bronze, five-foot-square tablet honoring Madame Schumann-Heink at the Spreckels Organ Pavilion. The tablet had been purchased through popular subscription. Superimposed upon the tablet is a huge star upon which is a lyre and an open book with the inscription “In loving memory of Mme. Ernestine Schumann-Heink. A Gold Star Mother. A Star of the World.”

Critics regarded Schumann-Heink as one of a cluster of extraordinary singers, among whom are Jean and Edouard de Reszke, Pol Plangon, Enrico Caruso, Luisa Tetrazzini, Lilli Lehmann, Lillian Nordica, and Nellie Melba. These singers had long and hard apprenticeships. They welcomed opportunities to do bit roles. They nurtured their voices carefully and took pains never to force their voices beyond their limits. They learned their techniques from one another and deepened their understanding of their parts through their association with the great composers of their time. They were not one-day wonders.

As a woman, Schumann-Heink was a contradiction. She represented an independent, self-made person eager to be known and to lead, yet she advised other women to stay at home and look after their husbands and children. She did not think women should vote or take part in politics, but, when the time came, she did both. As an artist she claimed to be indifferent to politics, yet as her years in the United States lengthened she became a proponent of national recovery and national defense and an opponent of prohibition. She admired Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the antithesis of homebody.

As a writer for Commonweal put it, “The American people liked her because she was natural.” It did not matter to those who heard Schumann-Heink’s made-up stories, vernacular jokes, and sentimental songs if she was sincere or truthful because her joy and vitality were contagious. A reporter in the San Diego Union in 1933 was overcome by Schumann-Heink’s charisma. “An hour with Madame Schumann-Heink is like bathing in the stream of life. One comes out refreshed, one’s mental cobwebs blown away with her rich humor; one’s faith in God and the essential fitness and worthwhileness of life renewed; one’s courage shamed into new being.”

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Ernestine Schumann-Heink#dramatic contralto#contralto#Royal Opera House#Covent Garden#Bayreuth Festival#Bayreuther Festspiele#classical musician#classical musicians#opera history#history of music#history#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (January 27)

Angela Merici, foundress of the Ursuline Sisters, was born in the small Italian town of Desenzano on the shore of Lake Garda on 21 March 1474.

As a young girl, Angela lost in succession to her sister and parents. She went to live with a wealthy uncle in the town of Salo where, without benefit of formal schooling, Angela grew in poise, wisdom, and grace.

The age in which Angela lived and worked was a time that saw great suffering on the part of the poor in society.

Injustices were carried on in the name of the government and the Church, which left many people, both spiritually and materially, powerless and hungry.

The corruption of moral values left families split and hurting. Wars among nations and the Italian city-states left towns in ruins.

In 1516, Angela came to live in the town of Brescia, Italy.

Here, she became a friend of the wealthy nobles of the day and a servant of the poor and suffering.

Angela spent her days in prayer and fasting and service.

Her reputation spread and her advice was sought by both young and old, rich and poor, religious and secular, male and female.

But still, Angela had not yet brought her vision to fruition.

After visiting the Holy Land, where she reportedly lost her sight, Angela returned to Brescia, which had become a haven for refugees from the many wars then wracking Italy.

There, she gathered around her a group of women who looked toward Angela as an inspirational leader and as a model of apostolic charity.

It was these women, many of them daughters of the wealthy, some orphans themselves, who formed the nucleus of Angela's Company of St. Ursula.

Angela named her company after St. Ursula because she regarded her as a model of consecrated virginity.

Angela and her original company worked out details of the rule of prayer, promises, and practices by which they were to live.

The Ursulines opened orphanages and schools.

In 1535, the Institute of St. Ursula was formally recognized by the Pope and Angela was accorded the title of foundress.

During the five remaining years of her life, Angela devoted herself to composing a number of Counsels by which her daughters could happily live.

She encouraged them to "live in harmony, united together in one heart and one will. Be bound to one another by the bond of charity, treating each other with respect, helping one another, bearing with one another in Christ Jesus.

If you really try to live like this, there is no doubt that the Lord our God will be in your midst."

In 1580, Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan, inspired by the work of the Ursulines in Brescia, encouraged the foundation of Ursuline houses in all the dioceses of Northern Italy.

Charles also encouraged the Ursulines to live together in community rather than in their own homes.

He also exhorted them to publicly profess vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

These actions formalized Angela's original "company" into a religious order of women.

Angela Merici died on 27 January 1540

She was beatified by Pope Clement XIII on 30 April 1768. She was canonized by Pope Pius VII on 24 May 1807.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some say that New Orleans, home of Miss Fisher Con 2024, is the most haunted city in America, if not the world. And that ghosts aren't the only supernatural entities you might run into on these streets. Here's just one of the stories…

You could sense the excitement in the air that day in 1728 as the men of New Orleans gathered at the docks. The ship bearing the young women who were destined to become their brides had finally arrived from France. But that excitement soon turned to a hushed surprise once the passengers began to disembark. Rather than the hale and hearty beauties they’d been told about, these women, each bearing a small trunk or “cassette”, were pale and clearly unwell. Now, in and of itself, their condition really wasn’t surprising. They’d been on a small ship crossing the ocean for 5 months (although the voyage should only have taken 3). Even so, these girls seemed paler than usual - indeed, some of the girls’ skin burned and blistered almost immediately.

The so-called “cassette girls” were quickly ushered off to the Ursuline convent where they and their belongings would be placed on the 3rd floor. Here the Sisters would care for them until suitable marriages could be arranged. It was about that same time that a mysterious plague struck New Orleans. As the mortality rate went up, and the citizens were treated to the sight of bodies floating down the river and in the bayou, it wasn’t long before the whispers started. The girls must have brought something with them besides clothing in those cases. Something that must have been feeding on the women during the voyage, and was now feasting on the rest of the city.

With vampires on the loose, action had to be taken. It was decided that the best thing to do was to seal the creatures in the 3rd floor of the convent. Sealed by nailing the shutters and doors shut with nails blessed by the Pope. Once the deed was done, the plague suddenly lifted, and life returned to normal.

Now there are those that say this is nonsense. That epidemics of deadly disease hit New Orleans all the time, and that this one’s arrival at the same time as the “casket girls” (as they’re now called) was simple coincidence. That the 3rd floor shutters are just common hurricane shutters, that they aren’t nailed shut, and that there were never vampires at the convent. Perhaps they’re right, but consider this:

In 1978 two paranormal investigators were determined to get to the bottom of the casket girls story. They’d been denied access to the convent, but undeterred, broke into the grounds after dark. The next morning, their bodies were found on the stairs of the convent, drained of blood.

Happy October, everyone!

#miss fisher's murder mysteries#mfmm#miss fisher con#miss fisher and the crypt of tears#missfishercon#the adventuresses’ club of the americas#ms fisher's modern murder mysteries#miss s#new orleans#big easy#jazz#ghost#ghost stories#vampire

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Casket Girls

In 1728 a small group of young women arrived in New Orleans each bearing a small wooden chest – called a cassette in French – that was shaped much like a small coffin. They became known as “Les Filles á la Cassette” – the casket girls. This was actually the third wave of such young women, the first arriving in the French colony of Mobile in 1704 and the second arriving in Biloxi in 1719.

Handpicked by the Bishop of Quebec by order of the French king Louis XV, these young women were plucked from the orphanages and convent schools and spent nearly six months traveling from France to New Orleans. The sole purpose for the trip was to provide wives for the men of New Orleans. Those who arrived in New Orleans were placed under the care of the Ursuline nuns until such time as they found husbands.

Here is where the history of these intrepid and perhaps naïve young women who survived the grueling voyage begins to take a series of unusual turns. Because they were described as being “very pale” upon their arrival, it was rumored that the casket girls had a more sinister purpose – and the vampire legends began. But that’s a story better told by one of the many tour guides in the French Quarter.

For an interesting account of the first women to arrive in New Orleans, consider Joan Dejean’s “Mutinous Women: How French Convicts Became Founding Mothers of the Gulf Coast.”

- from The New Orleans Culture on FB via Derby Gisclair

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sunday 6 March 1836

7 ¾

11 ½

no kiss fine morning but dull - F34 ½° at 8 at which hour breakfast - A- off to the school at 8 55 I sat reading downstairs till 10 10 the latter ½ (had the former part on Friday) of ‘Six months in a convent: the narrative of Rebecca Theresa Reed, late inmate of the Ursuline convent mount Benedict, Charlestown, Massachusetts 2nd London edition, Reprinted from the American edition, with an Introduction London: Thomas Ward and co. 27 Paternoster Row 1836. William Tyler, printer, Bolt-cont, Fleet street’ 18mo. (or very small 12mo.) pp. 100 + viii pp. of Introduction 25,000 copies sold in Boston in a very few weeks - ‘which sale tended to increase rather than to lessen the demand for’ this little book - a lawless mob ‘has since demolished the building in which Miss Reed was confined’ no wonder! this little book, which bears the stamp of truth, as surely [?] to hold up the convent of Mount Benedict to the hatred of all honest men - ¼ hour looking into travelling books - out at 10 ½ to meet A- met Greenwood - he says something must be done about the Northgate hotel - some beer or something must be sold there, or the licence may be taken away - told G- to make inquiries and see after this - he wants me to let Carr have the hotel - I said C- had neither character nor money and the yellows were all against him saying he was such a party-man - gave Greenwood the key of my walk to look about him and asked him to come up some evening and talk matters over - we met A- at Mytholm and I turned back with her and left G- to look about having told him I hoped to have 18 horse-power to spare after pumping up the coal-water - came in at 11 20 - A- and I a minute or 2 with my father - at accounts till 12 ¼ -then A- and I read prayers to my aunt (in bed) and Oddy and Mary and John in 25 minutes - then sat with A- a little read the 1st 18 pp. of Whewell’s notes on German churches - at the school at 2 ¼ - waited 12 minutes in church till 2 ½ - Mr. Wilkinson did all the duty - preached 14 minutes from Ephesians v.14. called and sat an hour at Cliff hill - Mrs. AW- in good humour and spirits - home at 5 ¾ - dinner at 6 - coffee - read the first 20 pp. of a tour in Germany published in London in 1826 till 9 50 then 10 minutes with my aunt - dull but fair and finish day till 12 at noon - then rain and rainy afternoon - fair now at 10 20 pm and F38°

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sister Simplice

Volume 1: Fantine; Book 7: The Champmathieu Affair; Chapter 1: Sister Simplice

The incidents the reader is about to peruse were not all known at M. sur M. But the small portion of them which became known left such a memory in that town that a serious gap would exist in this book if we did not narrate them in their most minute details. Among these details the reader will encounter two or three improbable circumstances, which we preserve out of respect for the truth.

On the afternoon following the visit of Javert, M. Madeleine went to see Fantine according to his wont.

Before entering Fantine’s room, he had Sister Simplice summoned.

The two nuns who performed the services of nurse in the infirmary, Lazariste ladies, like all sisters of charity, bore the names of Sister Perpétue and Sister Simplice.

Sister Perpétue was an ordinary villager, a sister of charity in a coarse style, who had entered the service of God as one enters any other service. She was a nun as other women are cooks. This type is not so very rare. The monastic orders gladly accept this heavy peasant earthenware, which is easily fashioned into a Capuchin or an Ursuline. These rustics are utilized for the rough work of devotion. The transition from a drover to a Carmelite is not in the least violent; the one turns into the other without much effort; the fund of ignorance common to the village and the cloister is a preparation ready at hand, and places the boor at once on the same footing as the monk: a little more amplitude in the smock, and it becomes a frock. Sister Perpétue was a robust nun from Marines near Pontoise, who chattered her patois, droned, grumbled, sugared the potion according to the bigotry or the hypocrisy of the invalid, treated her patients abruptly, roughly, was crabbed with the dying, almost flung God in their faces, stoned their death agony with prayers mumbled in a rage; was bold, honest, and ruddy.

Sister Simplice was white, with a waxen pallor. Beside Sister Perpétue, she was the taper beside the candle. Vincent de Paul has divinely traced the features of the Sister of Charity in these admirable words, in which he mingles as much freedom as servitude: “They shall have for their convent only the house of the sick; for cell only a hired room; for chapel only their parish church; for cloister only the streets of the town and the wards of the hospitals; for enclosure only obedience; for gratings only the fear of God; for veil only modesty.” This ideal was realized in the living person of Sister Simplice: she had never been young, and it seemed as though she would never grow old. No one could have told Sister Simplice’s age. She was a person—we dare not say a woman—who was gentle, austere, well-bred, cold, and who had never lied. She was so gentle that she appeared fragile; but she was more solid than granite. She touched the unhappy with fingers that were charmingly pure and fine. There was, so to speak, silence in her speech; she said just what was necessary, and she possessed a tone of voice which would have equally edified a confessional or enchanted a drawing-room. This delicacy accommodated itself to the serge gown, finding in this harsh contact a continual reminder of heaven and of God. Let us emphasize one detail. Never to have lied, never to have said, for any interest whatever, even in indifference, any single thing which was not the truth, the sacred truth, was Sister Simplice’s distinctive trait; it was the accent of her virtue. She was almost renowned in the congregation for this imperturbable veracity. The Abbé Sicard speaks of Sister Simplice in a letter to the deaf-mute Massieu. However pure and sincere we may be, we all bear upon our candor the crack of the little, innocent lie. She did not. Little lie, innocent lie—does such a thing exist? To lie is the absolute form of evil. To lie a little is not possible: he who lies, lies the whole lie. To lie is the very face of the demon. Satan has two names; he is called Satan and Lying. That is what she thought; and as she thought, so she did. The result was the whiteness which we have mentioned—a whiteness which covered even her lips and her eyes with radiance. Her smile was white, her glance was white. There was not a single spider’s web, not a grain of dust, on the glass window of that conscience. On entering the order of Saint Vincent de Paul, she had taken the name of Simplice by special choice. Simplice of Sicily, as we know, is the saint who preferred to allow both her breasts to be torn off rather than to say that she had been born at Segesta when she had been born at Syracuse—a lie which would have saved her. This patron saint suited this soul.

Sister Simplice, on her entrance into the order, had had two faults which she had gradually corrected: she had a taste for dainties, and she liked to receive letters. She never read anything but a book of prayers printed in Latin, in coarse type. She did not understand Latin, but she understood the book.

This pious woman had conceived an affection for Fantine, probably feeling a latent virtue there, and she had devoted herself almost exclusively to her care.

M. Madeleine took Sister Simplice apart and recommended Fantine to her in a singular tone, which the sister recalled later on.

On leaving the sister, he approached Fantine.

Fantine awaited M. Madeleine’s appearance every day as one awaits a ray of warmth and joy. She said to the sisters, “I only live when Monsieur le Maire is here.”

She had a great deal of fever that day. As soon as she saw M. Madeleine she asked him:—

“And Cosette?”

He replied with a smile:—

“Soon.”

M. Madeleine was the same as usual with Fantine. Only he remained an hour instead of half an hour, to Fantine’s great delight. He urged every one repeatedly not to allow the invalid to want for anything. It was noticed that there was a moment when his countenance became very sombre. But this was explained when it became known that the doctor had bent down to his ear and said to him, “She is losing ground fast.”

Then he returned to the town-hall, and the clerk observed him attentively examining a road map of France which hung in his study. He wrote a few figures on a bit of paper with a pencil.

0 notes

Text

"The Americans are excessively curious, especially the mob: they cannot bear anything like a secret - that's unconstitutional."

- Captain Marryat explaining the Ursuline Convent riot, from A Diary in America, With Remarks on Its Institutions (1839)

#charlestown massachusetts#ursuline convent riots#riot#ursuline nuns#united states history#anti-catholicism#mob justice#massachusetts history#literary quote#political culture#united states constitution

1 note

·

View note

Photo

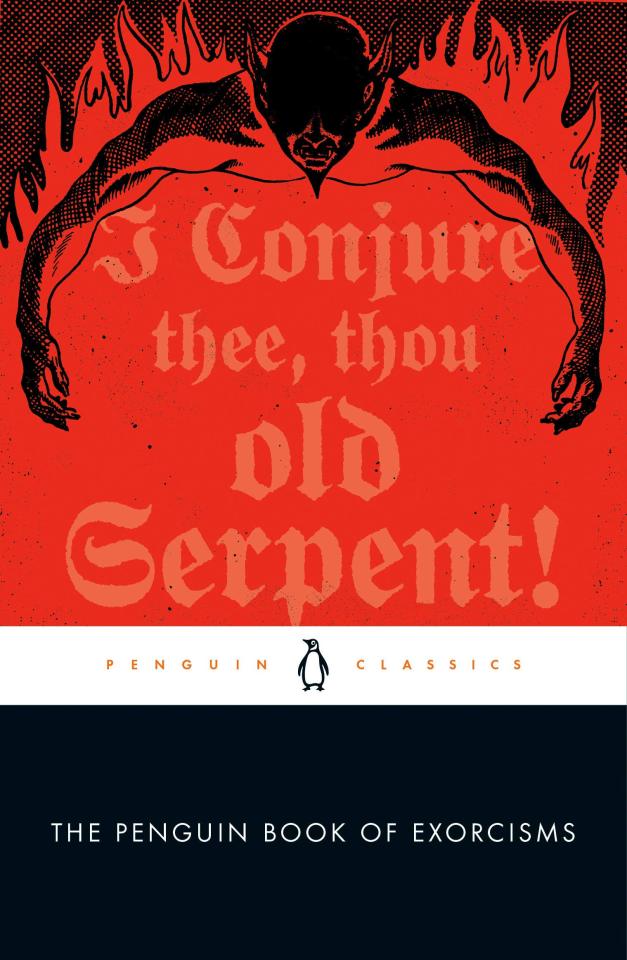

The Penguin Book of Exorcisms, edited by Joseph P. Laycock, Penguin Classics, 2020. Cover image by CSA Image/Getty Image, info: penguinrandomhouse.com.

Haunting accounts of real-life exorcisms through the centuries and around the world, from ancient Egypt and the biblical Middle East to colonial America and twentieth-century South Africa. Levitation. Feats of superhuman strength. Speaking in tongues. A hateful, glowing stare. The signs of spirit possession have been documented for thousands of years and across religions and cultures, even into our time: In 2019 the Vatican convened 250 priests from 50 countries for a weeklong seminar on exorcism. The Penguin Book of Exorcisms brings together the most astonishing accounts: Saint Anthony set upon by demons in the form of a lion, a bull, and a panther, who are no match for his devotion and prayer; the Prophet Muhammad casting an enemy of God out of a young boy; fox spirits in medieval China and Japan; a headless bear assaulting a woman in sixteenth-century England; the possession in the French town of Loudun of an entire convent of Ursuline nuns; a Zulu woman who floated to a height of five feet almost daily; a previously unpublished account of an exorcism in Earling, Iowa, in 1928–an important inspiration for the movie The Exorcist; poltergeist activity at a home in Maryland in 1949–the basis for William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist; a Filipina girl “bitten by devils”; and a rare example of a priest’s letter requesting permission of a bishop to perform an exorcism–after witnessing a boy walk backward up a wall. Fifty-seven percent of Americans profess to believe in demonic possession; after reading this book, you may too.

Contents: Introduction by Joseph P. Laycock Suggestions for Further Reading Acknowledgments THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST An Exorcism from the Library of Ashurbanipal, Seventh Century BCE The Bentresh Stela, Fourth Century BCE THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD Hippocrates, “On the Sacred Disease,” 400 BCE Lucian of Samosata, The Syrian Exorcist, 150 CE Tertullian, The Nature of Demons, 197 CE Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, 210 CE Athanasius, The Life of Saint Anthony, 370 CE MEDIEVAL EUROPE Cynewulf, “Juliana,” 970–990 Thomas Aquinas, The Powers of Angels and Demons, 1274 EARLY MODERN EUROPE AND AMERICA Desiderius Erasmus, “The Exorcism or Apparition,” 1519 A Possessed Woman Attacked by a Headless Bear, 1584 “A True Discourse Upon the Matter of Marthe Brossier,” 1599 Des Niau, The History of the Devils of Loudun, 1634 Samuel Willard, “A briefe account of a strange & unusuall Providence of God befallen to Elizabeth Knap of Groton,” 1673 The Diary of Joseph Pitkin, 1741 Fray Juan José Toledo, An Exorcism in the New Mexico Colony, 1764 George Lukins, the Yatton Demoniac, 1788 JEWISH TRADITIONS OF EXORCISM Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 94 CE The Spirit in the Widow of Safed, 1571 Exorcisms of the Baal Shem Tov, 1814 THE ISLAMIC TRADITION Ahmad b. Hanbal, “The Prophet Muhammad Casts an Enemy of God Out of a Young Boy: A Tradition from Ahmad B. Hanbal’s Musnad,” 855 CE The Trial of Husain Suliman Karrar, 1920 SOUTH AND EAST ASIA A Hymn to Drive Away Gandharvas and Apsaras, Eleventh to Thirteenth Century BCE Chang Tu, “Exorcising Fox-Spirits,” 853 CE A Fox Tale from the Konjaku Monogatrishū, Eighth to Twelfth Centuries CE Harriet M. Browne’s Account of Kitsune-Tsuki, 1900 D.H. Gordon, D.S.O., “Some Notes on Possession by Bhūts in the Punjab,” 1912 Georges de Roerich, “The Ceremony of Breaking the Stone,” 1931 MODERN EXORCISMS An Exorcism Performed by Joseph Smith, 1830 W.S. Lach-Szyrma, Exorcizing a Rusalka, 1881 Mariannhill Mission Society, An Exorcism of a Zulu Woman, 1906 F.J. Bunse, S.J., The Earling Possession Case, 1934 “Report of a Poltergeist,” 1949 Lester Sumrall, The True Story of Clarita Villanueva, 1955 Alfred Métraux, A Vodou Exorcism in Haiti, 1959 E. Mansell Pattison, An Exorcism on a Yakama Reservation, 1977 Michael L. Maginot, “Report Seeking Permission of Bishop for Exorcism,” 2012 Notes Index

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Hey dude are you a wizard??”

#lizard man#astronaut#anthro#sfw fur#sfw#fur art#scifi#sci-fi & fantasy#anthro art#art#artists on tumblr#reptile#scalie#bear#ursuline#space suit

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The brick walls are not there to keep us out. The brick walls are there to give us a chance to show how badly we want something. Because the brick walls are there to stop the people who don’t want it badly enough.”

– Randy Pausch, The Last Lecture.

NAME: Esther Corbyn BIRTHDAY: November 14th 1677 GENDER: Cisgender female SPECIES: Banshee OCCUPATION: Zora delegate YEAR THEY JOINED ZORA: 1695 FACECLAIM: Christina Hendricks

HISTORY

TW: domestic violence.

To others, “unwanted” may be an adjective describing a worn out shoe or unwanted teddy bear, but to her it was a noun, a self-identifier, until she was welcomed into Zora. Esther Corbyn was found by a bishop who often boasted of his selfless nature, taking in a presumably orphaned infant with scarlet hair. He and his wife endured the wailing their new baby sang day and night, almost like clockwork as is normal for children so young. The crying worsened years later as young Esther reached womanhood, taunted by vivid nightmares, and her father threatened to beat the hysteria out of her. Clear tears trickled down freckled, rosy cheeks, and Esther tried to behave herself like never before, but heightened emotions continued to betray her.

One horrific night in 1690, Esther lay in bed inconsolable for twelve hours as she witnessed the upcoming Battle of Quebec. At her young age she couldn’t tell which side was right or wrong but saw the over-100 dead bodies laying in a stream of their own putrid blood. At his wit’s end her father, despite her mother’s insipid protests, handed Esther over to the Ursuline Sisters, a nunnery in Colonial New France. As they traveled into war-torn parts of the city of Quebec, Esther slowly put pieces together that she may be an advanced human because the dreams from previous weeks had actually come true for the poor victims of the city. She was young but intelligent and kept her findings to herself, having full knowledge that ‘witches’ were deemed daughters of Satan and would be killed upon sight. The lion’s den she and her father were nearing meant she was not safe from anybody. The nuns at the monastery gave Esther many teachings, and while reading and flora were some of her favorites, the beatings, constant supervision, and lack of any trust or liberty were not. Unable to hide the majority of her nightmares, the young banshee found herself being given blows to the stomach to hide her punishments for scaring the other young women and disturbing the abbey in the middle of the night. As the years slowly passed, Esther grew fluent in reading, writing, and speaking, but she was still a scared child with no support system.

After turning seventeen, Esther’s abuse worsened and she waited for the snow to melt before running away. As soon as April began, the young woman made it out of the city and into the woodlands, wandering for days. But freedom was better than being the helpless hostage she was all her life, and despite on the brink of death, she was happy. As her health diminished, she was found by the kindest face she had ever laid eyes upon, and taken into Zora. She learned of her species, of her healing blood, of her peers and mentors and what they could do. Some teachings may have been biased, but overtime her bruises healed and she returned to a healthy, steady weight. While excelling in school, she has had many positions in the town such as teacher, mentor, assistant, gardener, chef, and most recently a delegate of the town.

When asked where she grew up, often Esther Corbyn will give a quiet, close-lipped smile and look down at her hands which have pulled her up her entire life. “I was born chapped in the snow, a juvenile with nothing to her name. But because of Zora and Her love for all, I can give back to the community which taught me the definition of love, when I was on the verge of disbelief.” While she does not speak of this silent, forbidden past, she does not change her name so she remembers where she has come from. The seasoned banshee has belonged to the invisible world of Zora for as long as she has been alive, and she has no interest in the outside world. But the wars knocking at their door remind her of that dream many years ago, and she does not wish for history to repeat itself.

CONNECTIONS

Logan Couture: Esther’s previous supernatural mentee.

Julian Flamel (NPC): Esther’s friend.

STATUS

Esther Corbyn is taken.

#city rp#town rp#mumu rp#bio rp#skeleton rp#taken f#taken#banshee#christina hendricks#esther corbyn#domestic violence tw

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

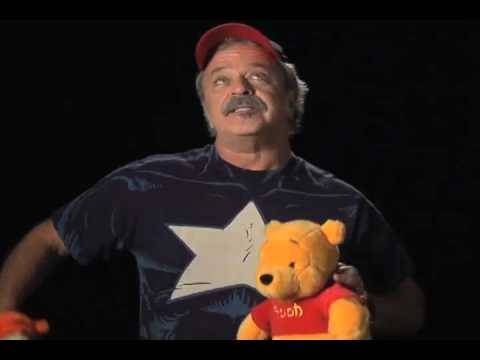

Your Fave Is Catholic: Jim Cummings

Known for: Beloved voice actor of cartoons, he is probably best known for being the current voice of both Winnie the Pooh & Tigger for Walt Disney since the 1980s. He initially started his career painting & repairing boats down in New Orleans, where he also had his own rock band called FUSION that was popular in the area. Later on, he started a career in voice acting, & the rest is history. Some of his other most iconic voice roles include Darkwing Duck, Pete (the bad guy from various Mickey Mouse cartoons), Tasmanian Devil of Looney Tunes, Dr. Robotnik in Sonic the Hedgehog (the Saturday morning cartoon, SatAM), Ed the Hyena from The Lion King, Fuzzy Lumpkins from The Powerpuff Girls, Monterey Jack from Chip & Dale: Rescue Rangers, Ray from The Princess & the Frog, Mr. Bumpy from Bump in the Night, Cat from CatDog, & so many many MANY more. To name a few other television cartoons he has lent his voice to, they include Disney’s Adventures of the Gummi Bears, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Talespin, Bonkers, Animaniacs, The Tick, Iron Man, Gargoyles, Earthworm Jim, Chalkzone, The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius, Star Wars: the Clone Wars, OK K.O.! Let’s Be Heroes, & so much more. To name a few other films he has lent his voice to, they include Laputa: Castle in the Sky, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Aladdin, The Pagemaster, Pocahontas, A Goofy Movie, Balto, Hercules, Antz, Babe: Pig in the City, The Road to El Dorado, The Life & Adventures of Santa Claus, Shrek, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, Gnomeo & Juliet, & many many more. Video games he has lent his voice to include Baldur’s Gate, Dragon Age: Origins, the Kingdom Hearts series, The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim, Epic Mickey, World of Warcraft: Mists of Pandaria, & many more. In short, he’s the guy who probably voiced some of your favorite cartoon characters growing up.

Evidence of Faith: According to an article from the Archdiocese of Baltimore discussing Jim’s successful career as a cartoon voice actor, it explains that growing up, Jim attended Immaculate Conception and St. Columba grade schools & the Ursuline High School, all of which are Catholic schools located in Youngstown, Ohio. The article also mentions that Jim is a member of the St. Jude Parish in Los Angeles to this day, indicating that he regularly attends Catholic mass.

#Catholic#celebrity#voice actor#Jim Cummings#cartoon#voice acting#television#film#movie#video games#Winnie the Pooh#Walt Disney

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (January 27)

Angela Merici, foundress of the Ursuline Sisters, was born in the small Italian town of Desenzano on the shore of Lake Garda on 21 March1474.

She and her older sister, Giana Maria, were left orphans when she was ten years old.

They went to live with a wealthy uncle in the town of Salo where, without the benefit of formal schooling, Angela grew in poise, wisdom and grace.

Young Angela was very distressed when her sister suddenly died without receiving the last rites of the church and prayed that her sister's soul rest in peace.

In a vision, it was said that she received a response that her sister was in heaven in the company of the saints.

Moreover, the age in which Angela lived and worked (the 16th century) was a time that saw great suffering on the part of the poor in society.

Injustices were carried on in the name of the government and the Church, which left many people both spiritually and materially powerless and hungry.

The corruption of moral values left families split and hurting. Wars among nations and the Italian city-states left towns in ruins.

In 1516, Angela came to live in the town of Brescia, Italy. Here, she became a friend of the wealthy nobles of the day and a servant of the poor and suffering.

Angela spent her days in prayer, fasting and service. Her reputation spread and her advice was sought by both young and old, rich and poor, religious and secular, male and female. But still, Angela had not yet brought her vision to fruition.

After visiting the Holy Land where she reportedly lost her sight, Angela returned to Brescia, which had become a haven for refugees from the many wars then wracking Italy.

There, she gathered around her a group of women who looked toward Angela as an inspirational leader and as a model of apostolic charity.

It was these women, many of them daughters of the wealthy and some orphans themselves, who formed the nucleus of Angela's Company of St. Ursula.

Angela named her company after St. Ursula because she regarded her as a model of consecrated virginity.

Angela and her original company worked out details of the rule of prayer, promises and practices by which they were to live.

The Ursulines opened orphanages and schools. In 1535, the Institute of St. Ursula was formally recognized by the Pope and Angela was accorded the title of foundress.

During the five remaining years of her life, Angela devoted herself to composing a number of Counsels by which her daughters could happily live.

She encouraged them to "live in harmony, united together in one heart and one will, be bound to one another by the bond of charity, treating each other with respect, helping one another, bearing with one another in Christ Jesus; if you really try to live like this, there is no doubt that the Lord our God will be in your midst."

In 1580, Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan, inspired by the work of the Ursulines in Brescia, encouraged the foundation of Ursuline houses in all the dioceses of Northern Italy.

Charles also encouraged the Ursulines to live together in community rather than in their own homes.

He also exhorted them to publicly profess vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. These actions formalized Angela's original "company" into a religious order of women.

Angela Merici died on 27 January 1540.

She was beatified by Pope Clement XIII in Rome on 30 April 1768 and canonized by Pope Pius VII on 24 May 1807.

0 notes

Text

St. Dominic Girls Soccer Shootout

St. Dominic Girls Soccer Shootout

Junior Kassidy Louvall (L) celebrates with Mary Sommerhof (15) Mary Koeller (2) and Kirsten Lepping (20) after scoring her first of two goals vs FZE on May 24, 2016 The St. Dominic Girls Soccer Shootout opens this evening. Playing in a Group model, with 12 teams across three groups, results are based on points. I’ve created tables featuring each of the three pools to track results as well as…

View On WordPress

#Cor Jesu Chargers#Duchesne Pioneers#Francis Howell Central Spartans#Francis Howell North Knights#Ft. Zumwalt West Jaquars#O&039;Fallon Township Panthers#Parkway Central Colts#Rock Bridge Bruins#St Dominic Crusaders#St. Dominic Varsity Shootout#Timberland Wolves#Ursuline Bears#Villa Duchesne Saints

0 notes

Text

Sunday 6 March 1836

7 ¾

11 ½

no kiss fine morning but dull - F34 ½° at 8 at which hour breakfast - A- off to the school at 8 55 I sat reading downstairs till 10 10 the latter ½ (had the former part on Friday) of ‘Six months in a convent: the narrative of Rebecca Theresa Reed, late inmate of the Ursuline convent mount Benedict, Charlestown, Massachusetts 2nd London edition, Reprinted from the American edition, with an Introduction London: Thomas Ward and c° 27 Paternoster Row 1836. William Tyler, printer, Bolt-cont, Fleet street’ 18mo. (or very small 12mo) pp. 100 + viii pp. of Introduction 25,000 copies sold in Boston in a very few weeks - ‘which sale tended to increase rather than to lessen the demand for’ this little book - a lawless mob ‘has since demolished the building in which Miss Reed was confined’ no wonder! this little book, which bears the stamp of truth, as surely [?] to hold up the convent of Mount Benedict to the hatred of all honest men - ¼ hour looking into travelling books - out at 10 ½ to meet A- met Greenwood - he says something must be done about the Northgate hotel - some beer or something must be sold there, or the licence may be taken away - told G- to make inquiries and see after this - he wants me to let Carr have the hotel - I said C- had neither character nor money and the yellows were all against him saying he was such a party-man - gave Greenwood the key of my walk to look about him and asked him to come up some evening and talk matters over - we met A- at Mytholm and I turned back with her and left G- to look about having told him I hoped to have 18 horse-power to spare after pumping up the coal-water - came in at 11 20 - A- and I a minute or 2 with my father - at accounts till 12 ¼ -then A- and I read prayers to my aunt (in bed) and Oddy and Mary and John in 25 minutes - then sat with A- a little read the 1st 18 pp. of Whewell’s notes on German churches - at the school at 2 ¼ - waited 12 minutes in church till 2 ½ - Mr. Wilkinson did all the duty - preached 14 minutes from Ephesians v.14. called and sat an hour at Cliff Hill - Mrs. AW- in good humour and spirits - home at 5 ¾ - dinner at 6 - coffee - read the first 20 pp. of a tour in Germany published in London in 1826 till 9 50 then 10 minutes with my aunt - dull but fair and finish day till 12 at noon - then rain and rainy afternoon - fair now at 10 20 pm and F38°

0 notes

Text

The Ursuline School Playground, Québec

The Ursuline School Playground, Québec, Canadian Real Estate, Landscape Architecture, Urban Design, Images

The Ursuline School Playground in Québec

Jan 20, 2022

Landscape Architect: EVOQ Architecture

Location: The Ursuline School, Old-Quebec Campus, 4 du Parloir Street, Québec (Québec) G1R 4M5, Canada

The Ursuline School Playground – Four Centuries of Learning at Play

Located in the heart of Old Quebec, the Ursuline Monastery is one of the few large conventual complexes dating from the establishment of the French colony beginning in the 17th century. This National Historic Site has been dedicated to education since the arrival of a missionary group of Ursuline nuns in 1639 and its built and landscape components bear witness to the different phases of its evolution. In keeping with its original vocation while meeting the needs of students attending the present-day elementary school, the Ursulines ceded part of their garden to enlarge the school’s playground. In the fall of 2020, EVOQ’s Landscape and Urban Design Team undertook the playground’s redevelopment. Anchored in the site’s heritage value and its many unique features, the new installations establish a dynamic and sensitive dialogue with their context.

The Ursuline School Playground

Turning constraints into design solutions Perched on the steep promontory of Cap Diamant, Old Quebec is known for its irregular topography. Contained within the old fortifications, the urban fabric has grown more dense over the years, giving the area a distinctive character. To protect this centuries-old legacy, all interventions needed to be executed with the utmost rigour and sensitivity.

To preserve the integrity of the soil as well as the root systems of the mature trees, some of which trace their origins back to the 17th century, excavation operations were limited to the strict minimum. The design team worked closely with structural engineers to devise methods for anchoring playground infrastructure to the rock at the surface to avoid disturbing the soil while a team of archaeologists supervised the excavation work to ensure the preservation of artifacts discovered during previous digs. A new athletic track was strategically located to encircle and protect the nine apple trees of the old orchard, providing shade for users while commemorating the site’s rich landscape heritage.