#Two Treatises of Government

Text

Books seem to me to be pestilent things, and infect all that trade in them… with something very perverse and brutal. Printers, binders, sellers, and others that make a trade and gain out of them have universally so odd a turn and corruption of mind, that they have a way of dealing peculiar to themselves, and not conformed to the good of society, and that general fairness that cements mankind.

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, 1689

#john locke#two treatises of government#books and libraries#quotes#literary text#dark acadamia aesthetic#classic literature

0 notes

Text

The greatest part of things really useful to the life of man, and such

as the necessity of subsisting made the first commoners of the world look after, as it doth the Americans now, are generally things of short duration; such as, if they are not consumed by use, will decay and perish of themselves: gold, silver, and diamonds, are things that fancy or agreement hath put the value on, more than real use, and the necessary support of life.

-- Locke, Two Treatises on Government

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō

In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

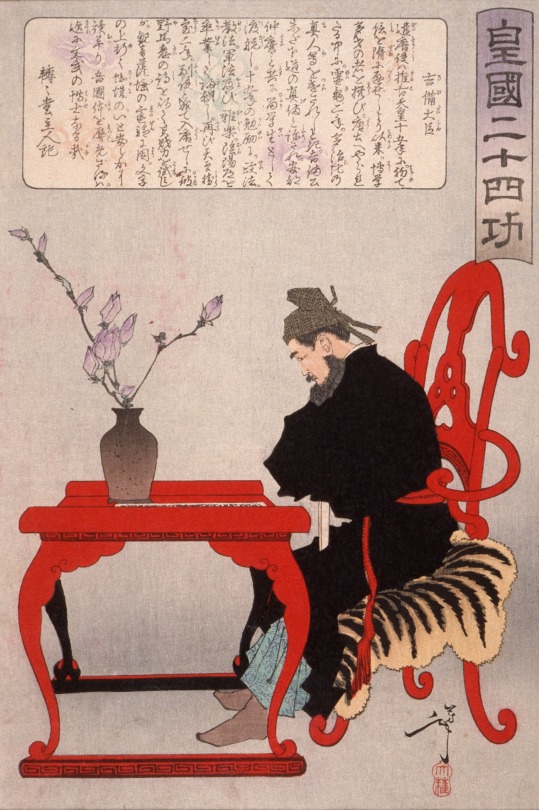

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances.

Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them.

The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though.

Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender.

As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

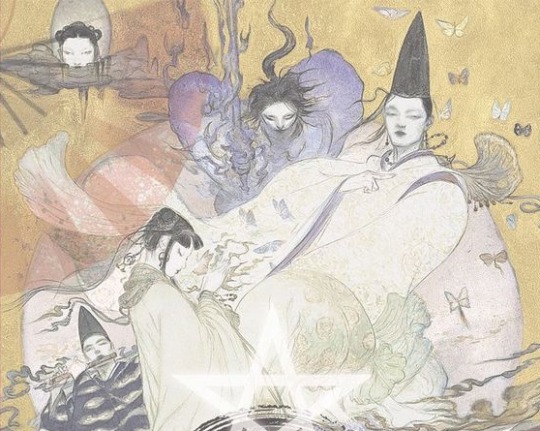

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

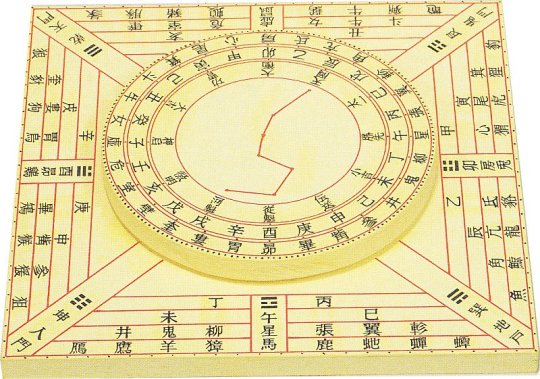

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications.

It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse

As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings.

A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

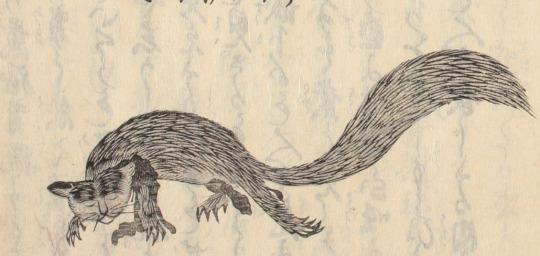

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho.

Post scriptum

The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive.

The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

146 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you know how hamilton felt about the madison-hamilton fallout? just realized everything i know about it is from madison’s perspective

oho boy do i

This has actually been a subject of interest of mine since I read The Three Lives of James Madison by Noah Feldman (great book, highly recommend). In the study of Alexander Hamilton, this is a crucial event that would define his proceeding political actions.

For some background for those who may not know what anon is referencing, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were colleagues and "friends" (if you could call it that) from their time in the Confederation Congress until Hamilton submitted his financial plan to Congress, which was all in all about a decade. In that time, they lobbied for a convention to revise the Articles of Confederation, worked together in the Constitutional Convention, and wrote The Federalist papers together in defense of strong federal government together. The Federalist was like the manifesto of the Federalist party, which placed Hamilton at the head of that party, and, arguably, James Madison as well, until he switched to the Democratic Republican party.

Hamilton's experience was far different from Madison's, just in general, but especially when it came to close friendships between men. The closest relationship he had before James Madison was with John Laurens, who we know died tragically in 1782. Although we are all aware of my feelings on rat bastard Ron Chernow, I thought that this excerpt of his biography of Hamilton described this point very well.

"[Laurens'] death deprived Hamilton of the political peer, the steadfast colleague, that he was to need in his tempestuous battles to consolidate the union. He would enjoy a brief collaboration with James Madison... But he was more of a solitary crusader without Laurens, lacking an intimate lifelong ally such as Madison and Jefferson found in each other," (Alexander Hamilton, Chernow 172-73)

As Chernow mentioned, James Madison was already closely associated with Thomas Jefferson, who he kept well appraised of the circumstances in America while Jefferson was serving a diplomatic position in France. In my personal opinion, I think it was largely due to this that Madison began to attack Hamilton later on, since as soon as Jefferson arrived back from Paris, Madison suddenly had severe moral oppositions to Hamilton's plan, rather than just rational apprehension.

I also want to touch on Hamilton's perspective in their friendship, along with their fallout, specifically when it comes to The Federalist. Hamilton put such a high value on his work, and he held himself to a very high standard. There are a couple instances of him outsourcing his work to other men he admired, such as his last political stance, that the truth of an accusation can be used in libel cases. He asked several men to help him in writing a larger treatise on the matter than what he was able to make (due to yk the bullet that got put in his diaphragm), but these weren't just his friends. These men were very crucial figures in American law, which shows that, unlike men like Jefferson, he was very selective in who he chose to associate with when it came to his work.

This wasn't any different in 1787. When he chose John Jay and James Madison to assist in writing The Federalist, his reasons for both had nothing to do with their personal relationships. Jay was one of the most successful legal minds of the new country, and James Madison, was not only a Virginian, but was an absolute genius and fucking workhorse. If you like him or not, or if you like the Constitution or not, its undeniable that the Virginia Plan was absolute fucking genius, and Hamilton knew that.

This also shows a great amount of trust in Madison. Hamilton was an incredibly untrusting dude. He kept most of his emotions and personality away from work, and really the only people who knew who he was entirely were close family, one or two family friends included. They were the only people who knew his background, which is directly tied into his work, which was the most important thing to him. Without his work, in his eyes, he would have nothing. So for him to trust Madison with something he and the world viewed as one of his most important contributions to American history, that was incredibly significant.

Also I should mention that Hamilton definitely knew how important The Federalist would be, and this is clear in his introductory essay, which is confirmed that he himself wrote.

One thing that any Hamilton historians will agree on is that he was so set in his ways. If there was a moral or philosophical question before him, he would think about it constantly, consult his books and his peers, and once he decided on his stance, there was little to no chance of changing that. The Federalist are, if not anything else, the basis of Hamilton's political thinking. Hamilton, being the arrogant bitch that he was, assumed that every other genius would be equally steadfast in their beliefs.

But James Madison was different in that regard. He was also very tied in with his state's interest, as well as that of the planter class. Hamilton also had a strong bias towards his state and class, but not with the same attitude as someone who was born into it.

Therefore, when Madison openly opposed his Report on Public Credit with a speech in the House of Representatives, Hamilton viewed it as a deep betrayal of his trust, his work, and his principles. Hamilton saw this as a devastating insult to everything he stood for by someone he thought he could completely rely on. This was the 18th century burn book.

That speech immediately kicked off Hamilton lobbying to oppose Madison's counter-proposal, which he won because, frankly, Madison hadn't been expecting Hamilton to immediately come at him with the full arsenal, but Hamilton didn't half-arsenal anything. It was after that that Hamilton was able to process what had happened. According to one of Hamilton's allies, Manasseh Cutler, Hamilton saw Madison's opposition as "a perfidious desertion of the principles which [Madison] was solemnly pledged to defend." Ouch.

The final break between them was on the subject of the National Bank aspect of Hamilton's plan. This is when Madison redefined himself as a Democratic-Republican with a firm belief in strict construction of the Constitution, giving Hamilton free reign to take out his hurt feelings on him through the art of pussy politics* and this entirely dissolved the friendship that had once been there.

*pussy politics (noun): a form of politics in which grown men act like pussies by only supporting the governmental actions that benefit their families/wealth/land/class/etc. and it is very embarrassing and frustrating to sit through

Hamilton would spend a large part of his career battling Madison, and talking a lot of shit about him, which is what has allowed me to paint this stupid ass picture of two grown men fighting over banks. The personal language that he uses in regards to Madison is very different to the accusatory tone he took with his other enemies, and that in it of itself says a lot, but I hope this was able to shed some light on why Hamilton felt the way he did and what exactly he felt. Again, I love talking about this, so feel free to ask follow up questions!

#alexander hamilton#history#amrev#american history#john laurens#james madison#the constitution#constitutional convention#the federalist papers#washington administration#hamilton's financial plan#asks

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is where I stand with the Global Conflict this week (no one asked lmao)

1. The top priority for me is stopping the genocide in Gaza, and, immediately after that, establishing a Palestinian state/two state solution.

2. Hamas isn’t going to peddle any kind of solution/compromise. Hamas essentially took their “We want to kill Jews” treatise and replaced “Jews” with “Zionists” but nothing has changed. If you can’t see that, you’re dangerous and probably stupid.

3. The hostages need to be freed (if they’re still alive, which let’s be realistic, they probably aren’t.) If Netanyahu actually cared about freeing the hostages, he would have done it by now, and a large number of Israelis recognize that.

4. Recognition of the hostages/ October 7th and recognition of the genocide/ deeply awful conduct of Israel can and SHOULD coexist.

5. Joe Biden is a useless little bitch. Having him as President again would still be better than four more years of Trump.

6. The Met Gala was not orchestrated by Big Zionism to distract from the invasion of Rafah and saying that it was is just blatant antisemitism. That being said, the Israeli military does frequently carry out large strikes on nights like the Met Gala and the Super Bowl when they know that the American news cycle will be focused on something else. Both things can be true. Also, the Met Gala is inherently a stupid thing to get excited about I’m sorry.

7. Student protestors do often fall into traps of antisemitism and say shit that could potentially harm Jews. What else is going to happen, when you gather a bunch of 19 year olds and tell them to yell as loud as humanly possible? That being said, I do have to believe that a vast majority of college protestors have good intentions AND, most of all, even if they don’t, censoring them and spraying pepper spray in their eyes is draconian behavior that the history books will not look kindly upon.

8. I’m so on the fence about boycotts, especially Eurovision. Because on one hand, banning Palestinian flags and keffiyeh’s from the performance is wrong. And I don’t think that Israel should be allowed to compete considering everything that the government is doing, like Russia was banned in 2021. That being said, it does make me sad that this 19 year old girl wrote a song about losing friends and family on October 7th and in response, she’s been booed and told to stay in her hotel room lest the angry mob tears her apart.

9. I do think that celebrities have some level of responsibility to use their platforms for good. That being said, this is such a complex issue that I almost don’t fault some people for not making a 250 character Twitter statement. I don’t think the dying children of Gaza care much if you block Zendaya or Olivia Rodrigo on Instagram. It also gets ridiculous when you go in the comments section of creators with like 100k followers and you see people posting Palestinian flags like yeah I’m sorry that blorbo from my shows isn’t personally flying to Gaza to punch Netanyahu in the face.

10. If you punctuate every single acknowledgement of the genocide with “but what about the hostages!!” or GOD FORBID “it’s sad that Hamas made Netanyahu do this” you have been propagandized by your local Hillel. No one made Netanyahu do this except Netanyahu. There’s no way you don’t know that by now. Wiping out Hamas: another thing that Netanyahu probably would have done by now if he genuinely wanted to.

11. Whenever I see lists of “here are the celebrities/professors/writers/guy on the street to block and throw rocks at because he’s a Mean Scary Zionist” I am reminded of the lists of synagogue goers that Nazis used to track down Jews and their families during the Holocaust. Seriously if you’re peddling lists of “Zionists” ripe for demonization you might want to ask yourself what you’re REALLY doing, and why.

12. Fun fact about me: I actually consider myself a Zionist. I do think, historically speaking, that Jews do need a safe place and a homeland to prevent us from being killed again like we seem to be every few centuries or so. I just don’t think that place has to be Israel, and I DEFINITELY don’t think Palestine should be subjugated for it to happen. But whenever I hear “Zionism = BAD” I just cringe a bit because… you keep using that word. I don’t think it means what you think it means

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Klaus' legal logic of The Bad Beginning sensible?

* Joint Theory: @unfortunatetheorist with @snicketstrange *

Klaus's speech to the audience during the events of The Bad Beginning had a carefully thought-out structure, anchored in deeply rooted legal, but more so ethical, principles. In defence of his sister, who was forced into a marriage, Klaus appears to have adopted a multifaceted approach to challenge the marriage's validity.

Firstly, John Locke.

John Locke was one of the first people to suggest that humans have natural rights. He also wrote a book about this called the 'Two Treatises of Government'.

Klaus likely invoked John Locke's arguments on natural rights to contend that the marriage was not consensual and, therefore, violated his sister's fundamental rights to life and liberty. The idea that the bride must sign "with her own hand" is interpreted here not literally, but as an indicator of action "of her own free will," supported by Locke's principles.

Secondly, Thurgood Marshall.

Thurgood Marshall was the first black Supreme Court Justice of the USA, who fought for the rights of black citizens against Jim Crow's extremely racist ideologies.

His defence of the 14th Amendment may have been used by Klaus to argue that, in cases of ambiguity or doubt, the judge's decision should lean towards protecting the more vulnerable party. This point strengthens the point that, if there is doubt about the how valid Violet's consent is, the legal and ethical obligation is to invalidate the marriage. The 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution is crucial for establishing constitutional rights and consists of various clauses. The most relevant for Klaus's case is probably the Equal Protection Clause, which states that no state may "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." Klaus may have leaned especially on this clause to argue that, in situations of uncertainty, i.e. his sister's forced marriage, the interpretation/application of the law should be done in a manner that protects (in this case) Violet. This would align with the principles of the 14th Amendment, using it for equal protection under the law to invalidate the marriage and protect his sister's rights.

Third, Ida B. Wells.

Ida B. Wells was, similar to Thurgood Marshall, an early civil rights campaigner, who campaigned for anti-lynching (a word which here means, opposing the brutally violent act known as lynching).

Klaus likely drew inspiration from Ida B. Wells to assert that everyone has the right to be heard and protected by authorities, regardless of their age or origin. This argument would serve to legitimize his own standing as his sister's defender in court, neutralizing any potential prejudice against him for being a child or, perhaps, belonging to a minority (he and his sisters are Jewish).

Moreover, the presence of a judge at the ceremony should not be viewed as merely a formality, but a control mechanism to ensure mutual consent, something that resonates strongly with Locke and Marshall's ideals about the role of government and law. Thus, if either of the spouses gave any evidence to the judge that the marriage was conducted under duress, the judge would be obligated to invalidate the marriage. Violet's chosen signal was to sign the document with her left hand instead of her right hand. As the judge explained, the marriage could be invalidated due to this discreet yet appropriate signal.

Lastly, the word "apocryphal" that Lemony uses to describe Klaus's argument suggests a non-conventional but insightful interpretation of the law, something that seems to echo Marshall's "doubtful insights" and Wells' "moral conviction." Instead of resorting to literalism ('literally' - with her own hand, i.e. Violet's dominant hand), Klaus's argument was much deeper and grounded, touching on the very essence of what legislation and the role of judges are. That's why Justice Strauss was so fascinated by the young boy's speech.

In summary, the historical references evidence that Klaus wove these diverse elements into a cohesive and compelling argument, utilising the legacy of these thinkers to question and, ideally, invalidate his sister Violet's forced marriage.

¬ Th3r3534rch1ngr4ph & @snicketstrange,

Unfortunate Theorists/Snicketologists

#asoue#asoue netflix#theory#vfd#a series of unfortunate events#lemony snicket#snicketverse#count olaf#thurgood marshall#ida b wells#john locke#legally snicket#Very Fatiguing Definition(s)#'My brother's defining words again' ¬ Kit Snicket

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creature (Both Haunted & Holy)

Vinsmoke Sanji/Reader - Chapter 11 - 4.5k

You enter your cycle for the first time since you were taken.

ao3 | series masterlist | masterlist | next part

Notes on Selkenfolk, from the Journal of Dr. Crocus of the Roger's Pirates

Selkenfolk, due to how closely related they are to seals, are quite powerful creatures. They are, undoubtedly, one of the major reasons that slavery has been abolished, with many selkenfolk who wind up under the thumb of celestial dragons often escape. The treatises between the various colonies of selkenfolk and the Celestial Dragons and World Government are quite extensive.

Pell is not shy about his pride when it comes to this, especially considering he has been one of the main thorns in the World Government's side, with devil fruits made essentially useless when it comes to any battle, so long as a selkie has access to the sea and their pelt.

Even then, Coth and Pell have both admitted they have two main weaknesses, their own main concern being the cycle. The cycle is essentially that of a selkie's breeding season, to put it rather crudely. They need their pods or mates during these times, often to simply care for them. It can vary on the selkie, for the symptoms they show, but they can vary from more... intimate needs, to simply being around their podmates.

Your head pounds when you wake up in your bed. You’re unsure of what exactly is wrong, but Nami nearly immediately notices when you grumble, trudging your way into the galley with your pelt wrapped around you tightly, and a pair of sweatpants hanging off your hips as you curl up on the couch. Everything aches, and you feel as though you’re on fire and frozen at the same time. Sanji looks over from where he’s cooking, calling for Nami. And you can’t help but agree, you want your pod, even if you’ve been scenting the ship and your crew.

Pod pod pod, your mind corrects happily, and you resent that. They are not your pod, even if you are fiercely loyal to them.

“You look… tired,” Nami tries, walking up beside you, laying a hand on your shoulder as you groan, looking at her with a miserable glare. “Okay, yeah, yeah, not a joking time,” She sits down beside you, pulling you into a hug which you respond to with a warble, setting your face on her shoulder. “Oh, honey… what’s happening?”

“I don’t know,” you groan, letting her place a blanket around you. “My head hurts, and everything is sluggish.”

Nami hums, running her hands through your hair, listening to you trill when she does, nuzzling closer, frowning as she feels how damp your hair is from sweat.

“Have you eaten yet today?” Sanji crouches in front of you, frowning. “Let me check your temperature.”

You whine when he presses the back of his hand to your forehead. You know something’s wrong the moment that he frowns, looking at Nami with an expression you can’t quite read. Worry spills off of your podmate, and you shy away from the cook's touch, trying your best to surround yourself with Nami’s scent while choking on how heavy your own is around you.

“You’re burning up,” Sanji stands, and you hear his footsteps walking away, and the sink turning on and off. “I’ll make some soup, you should stay there, it’ll be easier for you on the couch, especially if we can limit you from overexerting yourself.”

“I don’t overexert myself,” you mumble, whining when Nami’s hand leaves your scalp, trying to follow her. “Where'ya goin?”

“Just to get you a cool cloth,” Nami soothes, and you let out a whine at this. “I’ll be back in a minute.”

You sit with your knees tucked into your chest, fighting the urge to nod off, despite how comfortable the couch is. Nami hadn’t come back yet, you had to wait for your podmate to come back. You let out a rumble, a low and lonely cry of podmate, return, need podmate, which catches Sanji’s attention. You look utterly pitiful, curled up like that, continually warbling and rumbling for Nami, her name being the next most common thing you whimper in the passing minutes. Whatever was wrong, the heavy scent of pine and cinnamon wasn’t helping– had someone lit a candle? Surely that's not good for you in your current state. He'll lecture them later.

“Do you want some water? A blanket?” He walks from around the island, grimacing when you flinch at his voice. The smell is even heavier around you, and he can detect notes of seawater. “Sorry, did I startle you?”

You only grumble, finally laying down, letting out another rumble, and looking at him expectantly. Sanji falters. You had said that those noises were a sort of language when you were out with Luffy and himself on the deck, the other day. Sanji tries to make a rumbling noise, which you tilt your head at, thoroughly confused, before repeating yourself. Almost scared.

Maybe… both? Sanji thinks to himself, watching how you go quiet, eyes closed. Nami finally reenters, holding a bowl with a blanket tucked under her arm as well. You let out another rumble, this one quieter as Nami places the towel on your head. She hums in response and you look over at Sanji, almost unsure that you’re sharing the space with him. It’s almost adorable, seeing how you’re tucked into a blanket and practically cuddling into the ginger.

Now, Sanji will admit that he is... slightly weak when it comes to denying a woman anything. Especially his two crewmates, Nami, of course figuring out how to get him to practically do anything for her, and you, managing to embed yourself in his mind with a single smile. But this? This is the next level, dare he suggest cruelty, as Nami lets you snuggle into her, using her like a pillow, and you let out a huffing noise at him.

“Don’t tease Sanji,” Nami squeezes your nose and you let out a protesting warble, frowning when she gets up. “He’s helping you, don’t be a brat.”

Your face flushes, and you rumble, as if you’re pouting, before muttering out a very slurred ‘Sorry’ as if you’re drunk. This makes Nami stiffen, looking closely at you, and you try to snuggle deeper into her side, something akin to recognition in her eyes.

“Oh gods, are you in your cycle?”

This seems to strike something within you, and you let out a loud, terrified warble, staring at Nami before you croak out a sentence. “I— Oh Sea Mother— “ as you hold yourself tightly, going completely silent, before stumbling out of the galley, Nami hot on your heels.

She finds you puking over the side of the ship, panting as you pull yourself back up, staring at her with wide eyes.

“It— It can’t be my cycle,” you wipe at your mouth, starting to pace. “It’s— it’s been two weeks since we’ve set out. That’s way too soon for everything to reset—”

“Hey, you’re safe here,” Nami holds you, and you shake. “You’re not there, it’s okay. Let’s— we’ll get you a nest built, and you can stay in our room, I’ll tell the crew.”

You shake your head, hands gripping your scalp as you let out a pathetic warble, completely shutting down as Nami guides you down to your shared room. Almost immediately, you flop on your bed, curling tightly into the fetal position. Nami sighs and brings a blanket over, lays next to you, and comforts you as you start to cry.

“Try to sleep,” Nami whispers, “I’ll go get more pillows and blankets. You’re gonna be okay, it’s just the first day.” You only warble, and she holds you tighter, kissing your hair as you finally give in to the comfort of your podmate and her smell enveloping you.

It’s cold. And damp. It doesn’t help how your body aches, or how empty you feel without your pelt, your warbles for your pod going unanswered. All you wanted was your mothers, and your siblings, all curled around you, keeping you warm, keeping you safe, just like your last cycle. But Arlong had thrown you into a cell, as punishment for when you bit him two nights ago. You hadn’t seen another living creature since, but you heard them. Heard how they laughed, ate, and drank.

Your tongue is dry as you lick your lips, and your stomach growls for food. A selkie is meant to be well-fed and cared for during the cycle, making a nest of the softest materials, not left to rot in a cell. Especially not one who hasn’t had a true cycle yet, is too young to be properly mated, still a pup. This is what your grandfather had told you, Sion’s gentle father when you first turned sixteen. That true cycles would not start until you were around a suitable mate.

You can hear footsteps approaching, and your stomach rolls as the scent of your captor comes closer. You let out another warble of fear, trying to curl even tighter into yourself as Arlong stops at the door, looking in at you, and laughing. He sniffs the air, and a hungry growl echoes off the brick walls. You choke back a sob when he opens the door with a loud clang, dragging you up by your neck, and tossing you over his shoulder. You’re too weak from hunger, thirst, and exhaustion to fight back, only able to warble uselessly for your pod as the fishman carries you to his room.

“I smell a little selkie,” Arlong licks his lips as he tosses you on his bed, laughing as you try to crawl away, pulling you back to him by your ankle, “…who went into heat like some common stray bitch.”

You wail when he rips the loose shirt from your body, and try to push him away when he presses himself against you, clothed bulge evident.

You awaken with a warble, too feverish and achy to move already. Nami’s scent is strong but old. And something new is near you, tobacco and sugar. You don’t know who it is, but it’s gentle, and you can hear a soft voice, singing words you don’t know as a cool cloth is pressed to your head. Another scent, like fine cloth and wood, also sits nearby. You let out another warble, and the singing stops, a warm hand suddenly holding your own. Fine cloth and wood get stronger.

You manage to crack open your eyes to see Usopp sitting on the floor beside you, holding one of your hands, looking at you nervously. You blink, and your vision becomes clearer. Sanji stands behind Usopp, back turned as he works with something on the counter across the room.

“Hey,” Usopp’s voice cracks, and you can smell how nervous he is, anxiety crackling off him with the smell of sulfur and blood. “You scared me, for a second.”

You rumble out what you hope sounds like an apology because you’re not sure you can speak, the dream still too fresh in your mind. But this is Usopp. Cowardly, yet forever loyal Usopp who played cards with you and listened when you spoke about your family. Your podmate, you realize, Usopp. Part of you, the logical side hates how you’ve bent to the will of your instincts, your hindbrain taking over while you hate how pathetic you feel and present as.

“It’s okay, I just don’t like when people are sick, y’know?” He swallows thickly, closing his eyes for a second before opening them. “But! You’re gonna be fine. Nami… she kinda explained things to us. You’re safe,” he squeezes your hand and your heart melts a bit, “And we can play cards when you feel a bit better.”

The door opens, and Nami’s citrus and vanilla scent makes you whine.

“She’s up,” Usopp rises, squeezing your hand one last time, before letting go. You miss his touch already, trying to reach for him. He notices, tilting his head as you reach for him. Nami lets out a coo and settles by your side. You can feel how the bed dips.

“You’re part of the pod,” Nami laughs, when Usopp finally gives you his hand, and you cling to it, letting out a happy purr, instincts fully winning the battle with your mind. “Congrats on the promotion.”

Usopp only squeezes your hand and sits on the bed beside you. Your instincts coo happily, Pod, together. So, so warm. You close your eyes, a contented rumble rising from the back of your throat as the cloth on your forehead slips a bit. The other scent in the room shifts, and it comes nearer. But your pod is there, they will keep you safe, so this is a trusted person, if they’re allowed so close. A gentle hand brushes over your forehead.

“Fever’s gone down a bit, though I still don’t like how high it is,” The singing voice says again, and you put a sound to the smell. Nami lets out a hum.

“It’s probably because this is the first one in a year and a half,” she squeezes your hand, and you feel the bed dip further, as she pulls you into her lap. “It’s gonna be more like a bad flu than any cycle.” All you want to do is build a nest for yourself, Nami, and Usopp to curl up in. The voice makes a noise again as if the person behind it is thinking.

“Is that normal?”

“Well, we’d have to ask,” Nami sighs, “I’ll be honest, I only know so much about selkie stuff, I didn’t know they were even a thing before I met her.”

You let out a little rumble at that, cracking your eyes open again, and pushing yourself up into a sitting position. Your hindbrain wails at this, but you push it down, fighting your instincts to curl into your pillows. Sanji raises an eyebrow as you do this, watching as you get out of bed.

“Is that really the best idea?” He folds his arms, leaning back against the counter. “You look terrible.”

You glare at him, for that, and he backs down.

“You’re just sick,” he walks up beside you, “You should be resting, being easy on yourself during this time, it’s not healthy–”

“Don’t try to tell me what’s healthy for me,” You point your finger at him, going to push into his face when your hand passes through it fully, and your jaw drops, looking at your hand as Sanji disappears, standing at your side. Nami and Usopp look a bit more concerned now, as your vision blurs, seeing double of Sanji again. “That’s, huh, that’s…were you always standing there?”

Gently, Sanji holds your shoulders, which makes you whine loudly, keening at his touch as he pushes you back into your bed. Usopp pats the pillows next to him, and you’re so tempted to give in to your instincts, even with Sanji looming above you, a frown deep on his face as he looks down at you. You growl, baring your teeth at him, and he sighs, taking a step back to give you more space. Nami, however, flicks the back of your head.

“Don’t be mean,” She looks at you sternly, and you crumble, hindbrain fully taking over again and you whimper, laying back in the nest. “He’s trying to help. Let him.”

You whimper again, upset at being lectured, and Nami covers you in your quilt, making Usopp laugh a bit at how quickly you snuggle into the softness.

“It’s okay,” Sanji holds his face, turning away at how you look to be near tears, with how Nami still looks annoyed with you. He has to hide his blush at how adorable your pout looks, and how attractive he finds Nami’s attitude. He fails when he hazards a look at Usopp, who is smirking at him. “It’s a biological thing, right? Can’t fight it.”

“That’s the issue,” Nami sighs, and seemingly forgives you, stroking your hair out of your face, and you trill at her touch, pressing your face into her hands as she sighs your name. “She actively fights it, stubborn little shit.” Had you not been so content to simply have your two podmates beside you, you would definitely be protesting this right now, insisting you were fine.

“I’ll leave you be then,” Sanji can’t help but feel another tug at his heart at how you snuggle into Nami and Usopp, but your eyes follow him right up until he leaves, the heavy scent of pine, cinnamon, and seawater clinging to him until he showers. He misses it and hates how clean he smells after.

You wake up, unsure of what time it is, and groan at how your head still pounds. Your bed, however comfy, is cramped, with Usopp starfishing over your legs and torso, and Nami has her arms looped around your waist, drooling on your shirt, still dead asleep.

The first thing your sleep-addled brain remembers is how you had bit and growled at Sanji, and how your resolve had completely crumbled the moment Nami had so much as glanced at you sternly, sinking deep into your hindbrain and letting your instincts wash over you. A few, more hazy memories surface, of the past three days, with nesting and sticking by your podmates' sides. Quietly, you manage to worm your way out of the bed, hugging your pelt close, and sneaking up onto the deck of the ship.

It’s late, with the stars out above you. It’s the first time you’ve breathed fresh air in nearly four days. But it’s not the way it was when you were forced to stay inside by Arlong. It had been comforting, dare you say pleasant, surrounded by those you loved.

But it’s nice, to see the sky again, the moon in a waxing crescent as you make your way past the galley. All of the lights are off, and you look over the railings. The crew had docked somewhere, a small island, by the looks of the marina around you, and the small village just a few meters from the shore, houses on stilts to stand on the dunes.

Something above you in the crow’s nest rattles, and you look up, vision quickly focusing in the darkness. You hate to admit it, but the dark is better for your vision, able to see everything clear as crystal the moment the sun goes down. You can see the short, cropped-green hair, just barely peeking out from the short railing. The rope ladder swings in the breeze as you watch. Zoro doesn’t move, and you creep forward, standing on your tip-toes, climbing silently up the ladder.

The moment you climb into the crow's nest, Zoro has a blade against your throat. In turn, you let out a growl. You can see perfectly clearly in the night, and the swordsman is squinting for a moment before he recognizes you.

“Oh, it’s just you, seal,” Zoro takes the blade away, and watches as you settle across from him. “Aren’t you supposed to be asleep, sick, or something?”

“I got better,” you lie. Your head still hurts, but you can manage. You need to, you have to protect your crew. “Why are we docked?”

“Because you’re sick,” Zoro folds his arms and leans against the railing, “We need our helmsman and boatswain to be able-bodied in order to go through Reverse Mountain.”

You sigh, and Zoro shifts again, getting a bit closer. “It’s not your fault.”

“I can still feel guilty,” You let out an angry chuff, and Zoro laughs. “What’s so funny?”

“You’re ridiculous,” Zoro ruffles your hair and you growl again. “Nami said it’s like a period, you idiot. You can’t stop that shit.”

“I can take drugs that can,” Your eyes fall onto the few lights of the village, perhaps there’s a pharmacy. Sanji would be willing to help, surely–

“Not happening,” Zoro gives you a stern look, even if he can’t see as well as you can. “You’re already a wreck from the shit Arlong did, seal.”

Concern rolls off of Zoro. It’s minty, with recently passed rainfall and fresh-cut grass. Your instincts whisper in your ears to listen to him, that he truly cares, and that he is worried for you. But you, with all of the terrible things that have happened to you, argue back and shove your hindbrain down. Concern can be falsified, and you were tricked, countless times, by a fishman pretending to want to listen, only to have you tossed back to Arlong, hissing and screaming about your treachery, and your weakness.

“Don’t remind me how weak I am.”

“You’re not,” Zoro softens. “You care for this crew. And we’re allowed to care about you. As your friend, I’m allowed to care about you.” He holds out his pinky, the way you had for him.

You whine a bit, despite yourself, and Zoro opens his arms for you to get closer to him. The hindbrain keens, and urges you forward, yet you hold still, straining against yourself.

“Seal,” he sets his arms down, and slowly inches himself a bit closer until you can feel one of his hands along your face. Your eyes are squeezed shut, and you can’t stop shaking. “We’re not part of your family yet, that’s okay, but you are a part of ours, you’re a part of mine,” He hugs you, very gently, and awkwardly. “You’re gonna be okay here.”

You fall asleep in his lap. And Zoro adds himself to your pod accidentally, curling up awkwardly with Nami, Usopp, and yourself when you move your nest up to the anchor deck, much to Sanji’s chagrin as he moans to Luffy about how jealous he is that you are so willing to open yourself up to the swordsman.

The next morning, you’re lucid enough to start doing your duties again, however much your body aches as you lift things. Luffy walks in on this, as you lean over a barrel, sweating and cursing the bags of grains that had been bought in the local village, and the amount of dry goods that the crew can go through in a week while docked.

It makes him laugh at first, the way you glare at him, before he helps, lifting up everything without you even needing to ask before he asks if he can sleep in a pile like Usopp and Nami, and before you know it, Luffy is arguing with Usopp about who took who’s pillow, just like your little brothers had, and falls asleep, one arm wrapped multiple times around your right ankle, dead to the world, drooling on his pillow.

Sanji knows he will be the last to join your pod, and he feels so awkward about it. It’s not that you’re mean to him– quite the opposite– you’re as witty and helpful as ever. But, he isn’t entirely oblivious. You still spend time with him, but it’s never alone. It’s always with one of the other crew members, Luffy leaning over you dramatically as you try to discuss with him how much money he should be given for the month before you let out a bark at him, and he sulks in the corner until you’re done talking to Sanji.

It’s the worst when Nami is with you because he’s already so flustered with you around. She will actively make sure her shirt slips a bit lower, while you tell him about what kind of food is best for your diet, to rebuild muscle, making him go dry in the mouth as he tries to focus on what you’re saying. And she giggles when you ask her to stop distracting him because you’re both active distractions in his book.

But it’s comical, how you will reach over without looking, and pull her shirt up until it’s nearly at her nose while keeping Sanji’s gaze, and so sweetly talking about how well he cooked the previous dinner you had. He swears, however, that you smell nicer than normal, scent lingering around the kitchen, even hours after you leave. It does make him smile, because you’ve seemed to become more comfortable around him, brushing against him when you see him in the common area.

But he can’t help but feel a bit lonely when he walks into the storage room to find Zoro leaning over you, chin on the top of your head as you check things off a list, more annoyed that he purposefully put things higher than you instructed so you couldn’t reach them.

Sanji isn’t jealous, no. But he wishes that you wouldn’t look so confused when he shies away from you, thinking he’s respecting your wishes.

It takes another day for him to realize he’s a part of your pod when you ask why he didn’t join the rest of the crew that noon in the anchor deck, shy and nervous, thinking he’s rejecting your claim.

“N-no! No, I–” Sanji blushes, “I thought, uh, you didn’t want me there…”

You blink, and then your mouth forms an ‘o’ shape as if you’d just made the connections in your mind, cheeks darkening.

“I forgot humans can’t smell as well,” You look up at him, “I’ve been– well, it’s called scenting, it’s a thing we do when we have a pod.”

Sanji suddenly thinks back to how the mystery scent lingered around him. How it always followed you, and how it made him weak in the knees.

“I can stop if you’d like–” You raise your hands, thoroughly embarrassed, and the smell starts to fade. It makes him panic, his only constant reminder of you, fading away, so he yelps, grabbing your hands.

“No, no, it’s okay!” Sanji swears his heart is going to explode with how you look up at him. “I’d be honored to be a part of your pod.”

He coughs when you wrap him in a hug, a deep rumble shaking him to his core as he hugs you back, suddenly incredibly content with all in his life. As you drag him to where the rest of the crew is, up top near the steering wheel, sitting in or simply near a pile of cushions and blankets, arranging for him to sit near you as Zoro groans about Sanji being there. Nami laughs as she gets the ship moving, and Luffy clambers out of the nest to watch the sea.

That same smell that has been driving him insane, because he didn’t know what it was, your scent, of pine, cinnamon, and seawater, washes over him when you let out a chuff, planting your foot in Zoro’s chest and pushing him backward, a very, very dangerous thought crosses his mind, as you settle down, head against his chest. It makes his mind go fuzzy, the way you relax, how soothing it is to finally put a source to the smell, and how it tickles his nose and makes him weak at the very thought of being wrapped in it forever.

He could get used to you being in his life, melting at the idea of you preserving him in a casket of seawater, with sticks of cinnamon and pine boughs in his cold, dead hands for a bouquet, as long as you’re the one to lay him to rest. Sanji realizes that he needs you in his life, in some way or form. And that scares him, as the Straw Hats finally make their way to Reverse Mountain.

#black leg sanji#vinsmoke sanji#sanji x reader#sanji x you#vinsmoke sanji x you#one piece insert#one piece x reader#one piece x you

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manuscript Monday: LJS 405 - Kitāb al-Siyāsah al-sharʻīyah al-musammá tasʹhīl … (Video Orientation)

Dot Porter, Curator, Digital Research Services at the University of Pennsylvania Library, presents a video orientation to LJS 405, a treatise in two chapters, one on the qualities of a good ruler and the other on the art of good government. Partial loss of seal impressions and marginal notes due to trimming. LJS 405 is undated, likely copied in Egypt between the mid-13th and mid-14th…

youtube

View On WordPress

18 notes

·

View notes

Text