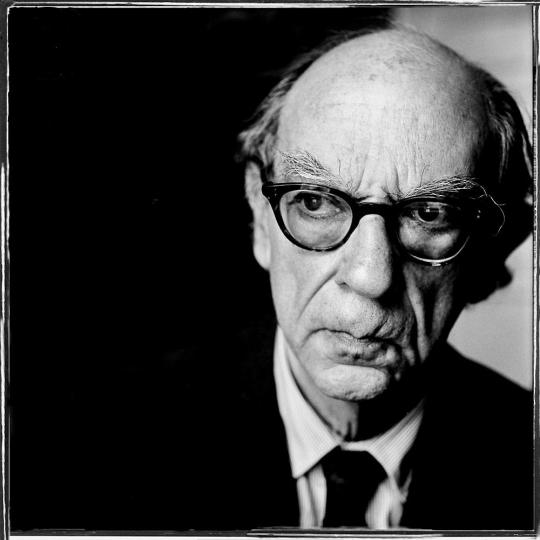

#Tocqueville

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

With the past no longer shedding light on the future, the mind advances in darkness.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

Digging into the poll itself...

48% say gender is essential to identity, outpacing religion at 34%

63% say companies should not take public stands on social and political issues.

58% say tolerance for others is very important (compared to 80% a mere four years ago).

Not good folks. Not good at all.

Source: Wall Street Journal poll

#alexis de tocqueville#tocqueville#quote#poll#society#collapse#USA#america#wall st journal#beliefs#values#state of the nation

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Society will develop a new kind of servitude which covers the surface of society with a network of complicated rules, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate. It does not tyrannise but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.

Alexis de Tocqueville

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seeing what happens in the world, might one not say that the European is to men of other races what man is to the animals? He makes them serve his convenience, and when he cannot bend them to his will he destroys them.

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 317

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

she alexis on my de till i tocqueville. send post

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“McCarthy, Tocqueville and democracy in America

Rather than speak in terms of Hobbes or Rousseau, it is more useful to suggest that there is a Tocquevillian political ethos present in McCarthy's body of work. This is because Alexis de Tocqueville encapsulates some of the political and philosophical contradictions which I argue are present in McCarthy's work. Moreover, Tocqueville's own work embodies precisely the resistance to ideological classification that we find in McCarthy. Tocqueville has received scant, if any, critical attention in terms of understanding McCarthy. However, his sprawling text Democracy in America offers political observations and critical insights about democratic practices and American identity which are of enormous value for understanding the political components of McCarthy's fiction. While I do nọt aim to suggest that McCarthy aligns necessarily with Tocqueville's political preferences, it is relevant to elaborate on how some of Tocqueville's observations about American political life help us to understand the political reflections implicit to McCarthy's prose.

The most obvious reason why Tocqueville is relevant to understanding McCarthy's work is that Tocqueville wrote in a later period in the chronology of political philosophy, so his ideas therefore are more historically proximate to McCarthy's own political milieu. Tocqueville made the observations on which he based Democracy in America in 1831, when the American democratic experiment was relatively young, if decisively maturing. While indebted to writers in the history of political thought - Hobbes, Rousseau and Montesquieu - Tocqueville was unencumbered by the philosophical expressions of the state of nature found in political theory. Tocqueville based his understanding of democratic political philosophy on concrete and factual observations of one of history's first grand-scale democratic experiments. Democracy in America is a remarkable work in ambition: because of its depth and range it functions at the intersection of journalism, anthropology, history, sociology, travelogue, political pathologies and political philosophy.

On the surface, McCarthy would not seem a natural ally for Tocqueville. Tocqueville suggested that the dominant trait of the United States is its ahistoricality. Given that the United States was in its relative infancy when Tocqueville was observing and writing about it, this positing of ahistoricality is based on his observation that American democracy arises from an ancestral amnesia where: each man forgets his ancestors, but it hides his descendants from him and separates him from his contemporaries'. This is certainly one place where we can say that McCarthy is not Tocquevillian. McCarthy is fascinated with how the long history of humanity illuminates the present and foreshadows the future - as I have evidenced in my appraisal of McCarthy's philosophical arguments for the continuing relevance of our evolutionary antecedents - where the ancient and the primeval coexist with humans' ongoing linguistic and technological development. Moreover, McCarthy is continually at pains to show how a forgetting, individually and collectively, of an enigmatic covenant of the past, present and future removes the possibility of any form of purposive meaning.

While Tocqueville noted the ahistoricality of American democracy, this view was tempered by his belief in the necessity of the continual refashioning of American democracy. The vitality of America stems from affirming process over identity; it is a country constantly engaged in the making of itself and its history. For Tocqueville, the dearth of historical meaning in American democracy is not necessarily a bad thing, since it bequeaths the populace with some necessary contradictions. While fraught on an individual level, that democracy is the constant process of being made and unmade is utterly essential for the proper functioning of the political sphere. As such, the American democratic spirit, the pursuit of a more perfect constitutional union, does imply a repudiation of the historical, since dogged individual self-determination, under a guiding ethos of 'equality of opportunity', requires one's historical origins to remain secondary to the capacity for self-reinvention. If self-invention is necessary, one ought not to be, and is not, strictly bound to one's own history. It follows that the overall body politic must be essentially weak and fallible rather than fixed or over-determined by past political mechanisms. Meaning is there to be achieved by an effort of will. For Tocqueville, in the political world: 'political principles, laws, and human institutions seem malleable, things that can be turned and combined at will [. . .] everything is agitated, contested, uncertain'. Thus, the fundamental weakness of democratic institutions is essential to American political identity. The absence of a centre delimits sovereign centralisation and hierarchy. According to Tocqueville, by partitioning federal authority through a constitutional separation of powers, the effect is that power remains weak and indirect. This should not be mistaken for anarchy or disorder, but on the contrary should be viewed as a 'love of order and of legality'.

Tocqueville's necessary contingency at the heart of government and democratic institutions evokes McCarthy's metaphysical proposition seen in the Woodward interview. If violence and contest are the central tenets of reality for McCarthy, it follows that McCarthy is a democratic writer in a Tocquevillian vein, as the political constitution of the American body politic reflects the contingent nature of reality itself. The political register of McCarthy's writing thus corresponds to what I described, when analysing The Sunset Limited, as a type of 'mitigated Platonism'. Democracy is not indexed to an external idea or reality which is impervious to historical power relations. McCarthy, while not necessarily endorsing this or that class or party of participatory or representative democracy, or even the desirability of democracy itself, can still be argued to be a type of democratic realist. He is a writer who aims to represent the unblemished consequences of the contested demos as it transpires. The reality which American democracy generates is not ideal and neither is it to be idolised or fetishised. For Tocqueville, as much as for McCarthy, democratic reality, whether oppressive or emancipatory, is always considered fabricated: there to be made, manufactured and produced, and consequently unfinished. In literary terms, this has a cacophonous effect, giving voice to benign and malign voices, recognising the inevitability of power, rhetoric and political seduction as much as a tolerance of the multiple traditions constituting the demos.

Elsewhere, Tocqueville determined that American democracy was defined by a fundamental contradiction: it was both optimistic and pessimistic simultaneously. Fatalism was, as it is usually understood, dismal, inert and pessimistic. For example, inherent to democracy is the possibility of a situation where:

The vices of those who govern and the imbecility of the governed would not be slow to bring it to ruin; and the people, tired of its representatives and of themselves, would create freer institutions or soon return to stretching out at the feet of a single master.

However, this fatalism is paired with a faith in progress, since Americans:

All have a lively faith in human perfectibility; they judge that the diffusion of enlightenment will necessarily produce useful results, that ignorance will bring fatal effects; all consider society as a body in progress; humanity as a changing picture, in which nothing is or ought to be fixed forever, and they admit that what seems good to them today can be replaced tomorrow by the better that is still hidden.

What is interesting about Tocqueville's descriptions is that the contradiction is functional. American optimism works because of American fatalism. Tocqueville's America is an optimistic democratic society; however, paradoxically, this optimism is entwined with a fraught pessimism. Because the foundation of the American body politic is built on equality of opportunity as well as the individual's pursuit of happiness, Americans in Tocqueville's account come to believe that prosperity, material acquisition and wellbeing are always within their grasp. But, because material wellbeing is directly correlated to the pleasures of their mortal bodies, they are condemned to agonise continually over any prospective loss of the pleasures they hold, or over not achieving the pleasures they perceive they merit. Pursuing individual material prosperity leads to honour and respectability, but beneath the veneer of respectable prosperity there exists a deeper malaise. For Tocqueville, such are the costs of existing in a meritocracy in which prosperity is enchained to personal abilities in direct competition with all others:

When the man who lives in democratic countries compares himself individually to all those who surround him, he feels with pride that he is the equal of each of them; but when he comes to view the sum of those like him and places himself at the side of this great body, he is immediately overwhelmed by his own insignificance and his weakness.

With respect to McCarthy, Tocqueville offers a unique precursor to the chaotic democratic spirit present in McCarthy's literature.

McCarthy also, throughout his work, depicts the two sides of democratic fatalism. McCarthy's writing is obviously a by-product of a democratic state and one is constantly struck by the passive, pessimistic fatalism of the literary world and characters he creates. Even so, the upside of his characters' pursuit of either essential material wellbeing or riches continually affirms a survival of hope and possibility - most acutely in Blood Meridian, The Road and No Country for Old Men - even if such hope remains fretful, fidgety and wholly brittle. As with the unfolding of American democracy itself, the perpetual pursuit of psychological or social harmony offers no guarantees or resolution in the end. McCarthy's characters are invariably trapped in an anxious wait for the good news that never arrives due to the essential incompletion of the American project he portrays. The framing of democratic politics in McCarthy is necessarily bleak because American democracy, either as a nascent or a mature entity, is chaotic, imperfect, contentious, tumultuous and ultimately without hope. Thus, as so often with McCarthy, we can see a collapsing of oppositional thinking, in this case optimism and pessimism.

What makes McCarthy's writing interesting is that he is both optimistic and pessimistic. McCarthy, like Tocqueville, spotted the tension in democracies, where individuals hold a faith that things will stubbornly work themselves out in the end, and this faith coexists with the ever-present sense of impending threat that prosperity will be taken away. McCarthy does not so much refuse the idea of progress as refuse the idea that American democracy is necessarily self-correcting. In colloquial terms, you cannot have the good without the bad. McCarthy's democratic world entails that the general political mood of his fiction situates itself firmly within American political identity, providing a remarkable mix of failed idealism and stubborn pragmatism. Ultimately, what unites the characters of his oeuvre is the inevitability of failed idealism co-existing with a pragmatic hope for survival.

The political pathology in Tocqueville's version of democracy is present throughout McCarthy's work. McCarthy's novels, with the notable exception of democratic collapse represented in The Road, are uniformly situated within the era of American democracy. If for Tocqueville, democracy invariably disturbs and unsettles the psychological self-description of individuals, then similarly, most of McCarthy's characters experience unsettled ways of feeling, cognising and behaving. As I have argued previously, this is particularly the case with Sheriff Bell's developing uncertainty and wisdom in No Country for Old Men; in Suttree's active rejection of prevailing customs and mores in Suttree; in the boy who transcends his father's pragmatism in The Road; in Lester Ballard and the perverse underbelly of the Tennessee social order, and with the kid grappling with the domineering influence of the Judge in Blood Meridian - all present the obverse underside of American optimism and exceptionalism. Such as it is, McCarthy's characters are the creations of both democratic malaise and democratic accomplishment. This is necessarily the case, since American democracy exists to cultivate the optimistic self-determination of its citizenship. As Tocqueville proposes, 'From Maine to Florida, from Missouri to the Atlantic Ocean, they believe that the origin of all legitimate powers is in the people.’ McCarthy's characters stand or fall on the extent to which they can or cannot transcend themselves. They, too, are perpetually unfinished, in the process of making themselves, and are a consequence of the way democratic decisions subject them both to a life of uncertainty, but also to a life of possibility and renewal.

If there is a political imaginary in McCarthy's work it resides in coping with a contagion of breakdown, crisis and the mutability of power relations. McCarthy's democratic realism, in its simplest form, tries to understand democratic humans as they live and as they are produced. Given the radical contingency of character psychology that occupies his literature, we can add another trait that McCarthy shares with Tocqueville's account of American democracy: anti-authoritarianism. Put in the simplest terms, McCarthy's literature retains a rebellious, anarchic, even populist scorn for figures of institutional authority: police, social workers, lawyers, clergy and corporate functionaries. As I have argued in Chapter 6, Sheriff Bell offers a particularly sharp example of this: the tragedy of his character emerges from the gradual shedding of his conservative shibboleths. In his more Tocquevillian moments, the political ethos of McCarthy's writing vigorously pinpoints that authority and hierarchy is not natural, with McCarthy revelling in portraying misfits and anachronistic characters which embarrass and shame the pretensions of pompous and unfeeling authority. Thus, the tragedy and renewal of McCarthy's characters are shaped by an irresolution that amounts to a perverse egalitarianism, where all humans hold the possibility and denial of their salvation concurrently.

This weird egalitarianism shows why one cannot easily suggest that McCarthy's written work sits well with conventional conservative pieties. McCarthy continually represents the importance and equality of the forgotten, the lost, misfits and delinquents: those who lose out to historical shifts. That he keeps these voices alive serves to openly embarrass any pretensions that democracy is settled or residing in long traditions. McCarthy is perhaps therefore one of the most democratic of writers, as his work continually serves to stimulate enthusiasm for the possibility of social and political equality, even if that equality is bounded with the inevitable chaos and contingency of life. While it would be inaccurate to argue that McCarthy is a socialist or motivated specifically by, say, a Marxist critique of consumer capitalism, it is clearly the case that his characters engage in a perpetual material struggle for equal recognition. This is nowhere more evident than in The Sunset Limited, with the symmetrical struggle for mutual recognition we find in White and Black. However, because of the ineradicable contingency purveying all McCarthy's writing, and by extension his representation of American democracy itself, any struggle for equality is tragically inaccessible. And therefore, McCarthy exhibits the Tocquevillian paradox: American democracy is radically contingent and ordered; however, it is this very contingency that makes democracy possible. Also, if contingency implies that innumerable possibilities can come to pass, the end of democracy itself must be one of them, which is of course the thought-experiment that The Road entertains.

The fugue of impending threat that adorns practically all of McCarthy's writing thus must be read as undermining any inherent declinism, since ending, in the Tocquevillian sense, is entwined with a possibility of renewal. The rhetoric of declinism is usually distinguished by corruption, decay, nihilism and the weakness of political institutions, and this is certainly evident with McCarthy. Quite often, declinism accompanies a fascistic critique of intellectuals, ideas economic instrumentalism over culture, spirit and vitality, where political institutions are in a state of irreversible decay? While these themes are obvious in McCarthy, they are not paramount. Given that' McCarthy's texts tend to gravitate inexorably towards the apocalypticism of The Road, clearly McCarthy thinks that the American democratic experiment, at best, is not robust enough to withstand whatever catastrophic event precipitates The Road, or at worst is in a de facto state of erosion to the point of self-annihilation. However, as I hope should be clear by now, The Road as ending, as decline, is not the end. The story actually shows that humans can muddle on in the face of enormous hardship. Thus, McCarthy unites the fatalism and optimism that Tocqueville sees at the core of American democracy. What is so interesting about McCarthy and why his literature resists political classification is that his representation of the relations between ruler and ruled show him at his most philosophical. The political inflection of his literature is fundamentally Socratic and McCarthy's political representation is a fly in the ointment of democratic self-assurance and smugness.

The political philosophy present in McCarthy's work is less libertarian conservatism and more democratic anarchism. As we saw in the way the TVA figures in McCarthy's work, we find a scepticism of authority and large-scale transformative projects as well as any faith in individuals and groups to self-govern successfully. McCarthy's democratic realism itself mirrors this logic in his representation of democratic life, with characters swaying between chaos and complacency, resentment, relief, hope and despair. The pursuit of enough material prosperity, as we saw with Llewelyn Moss, only offers an illusion of comfort as well as a complacent assumption that the political order is fundamentally sound. However, what McCarthy portrays throughout his literature is the underside of material progress, showing that American democracy 'works' through ever-present crises. It is not specific ideologies that fracture democracy; democracy must itself be fractured, weak and dispersed. Beneath the underlying stability of the democratic order lies a mélange of competing ideas, values and alternative 'truths'. In sum, the trauma that is always present in McCarthy's literature - Rinthy and Culla's base origin in Outer Dark, the apocalyptic disaster occasioning The Road, the original murder of The Orchard Keeper, the violence of Blood Meridian - is never just a singular traumatic event tied to individual character psychology, but instead reflects the broader manifestation of crises ever present in America's democratic experiment. However, as with the precarious structures in The Orchard Keeper, we should not take McCarthy's writing of crises as a validation of wild, chaotic anarchy or authoritarian rule. Instead, the political philosophy that is detectable in McCarthy's writing endeavours to think the complications of structure and chaos, rule and misrule, law and anarchy.

While Tocqueville thought the never-ending impending threat and crises might not lead to anarchy, this cannot be said for McCarthy. Most probably, for Tocqueville, the eventual outcome of democratic fatalism would be inertia, lethargy and stagnation. For McCarthy, the outcome foreshadowed in The Orchard Keeper is fulfilled in the anarchic savagery of The Road and American democracy's inability to cope with the novel's inaugural disaster. As with the other themes I have tackled throughout this work, the political function of McCarthy's literary imaginary blends the new and novel with the ancient and archaic. The chronology of McCarthy's narratives is preceded by an even longer story, one with deep roots in human evolution and the evolution of human societies. As we saw with Blood Meridian, humans' drive to civility, order and hierarchical rule is inseparable from popular demands for autonomy, self-organisation, mutual aid, voluntary association and even direct democracy. Hence, the conservative Sheriff Bell in No Country for Old Men vacillates between certainty and uncertainty, a representative of the state's power and frailty simultaneously. Bell's essential weakness and fallibility announces a broader desire for self-directed community and belonging. Bell is weak in the same sense that power is decentralised in America: power is elusive and ubiquitous, distant, yet somehow always to hand.” (p. 181 - 189)

#cormac#cormac mccarthy#tocqueville#alexis de tocqueville#no country for old men#democracy#america#the road#sunset limited#blood meridian#suttree#orchard keeper

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tocqueville in Algeria

"Great events have just taken place in Algeria; we can believe that others are still in preparation. So the time is ripe, Monsieur, to do as you wish and tell you what I know about Algiers. I do so all the more willingly because, although there has been much discussion about this country, very little is understood about it..." -Alexis de Tocqueville, 1st Letter on Algeria Alexis de Tocqueville is widely considered to be the Father of American Liberalism. A French aristocrat with deep affinities towards the liberalizing movements of his day, Tocqueville is most famous for his book Democracy in America which described the emerging state of American society soon after the War of Independence. What he is less well known for is his role in the colonization of Algeria, being one of its most influential advocates and forwarding a mixed policy of "partial colonization" and "total domination" which mixed the purchase of land for French settlers with the burning of crops, mass detainment of women and children, and destruction of "everything that resembles a permanent aggregation of population or, in other words, a town.”

Previously unpublished, Tikhanov Library is proud to announce for the first time the translation of Tocqueville's writings on Algeria into English. Read Alexis de Tocqueville's "First Letter on Algeria" on our substack: https://tikhanovlibrary.substack.com/p/alexis-de-tocquevilles-first-letter Or support us and future translations like this by buying the complete collection of his writings in paperback: https://tinyurl.com/u8fckmah This book and more are available as paperback and ebook on our website at www.tikhanovlibrary.com

#alexis#tocqueville#alexis de tocqueville#algeria#algerian independence#colonialism#france#genocide#book#bookstagram#bookblr#dark acamedia#academic#academia#mediterranean#war

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Para Constant, Mill, Tocqueville y la tradición liberal a la que ellos pertenecen, una sociedad no es libre a no ser que esté gobernada por dos principios que guardan relación entre sí: primero, que solamente los derechos, y no el poder, pueden ser considerados como absolutos, de manera que todos los hombres, cualquiera que sea el poder que les gobierne, tienen el derecho absoluto de negarse a comportarse de una manera que no es humana, y segundo, que hay fronteras, trazadas no artificialmente, dentro de las cuales los hombres deben ser inviolables, siendo definidas estas fronteras en función de normas aceptadas por tantos hombres y por tanto tiempo que su observancia ha entrado a formar parte de la concepción misma de lo que es un ser humano normal y, por tanto, de lo que es obrar de manera inhumana o insensata; normas de las que sería absurdo decir, por ejemplo, que podrían ser derogadas por algún procedimiento formal por parte de algún tribunal o de alguna entidad soberana.»

Isaiah Berlin: Cuatro ensayos sobre la libertad. Alianza Editorial, pág. 236-237. Madrid, 1998.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dias-de-la-ira-1

#isaiah berlin#constant#mill#tocqueville#libertad#libertad negativa#derechos#libertades#soberanía#libertad positiva#tradición liberal#imposición#voluntad#ser humano#ser humano normal#leyes#coacción#ausencia de coacción#poder#gobierno#inviolabilidad#tribunal#entidad soberana#teo gómez otero

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nuovi demoni

Quando scrissi Viaggio nell’odio, avevo dinanzi agli occhi un’Europa pacificata e serena, tanto che era necessario raccontare l’odio e la violenza come fiamme ancora accese in altre parti del mondo, cercando di esorcizzare un ritorno tra noi di queste forze negative. Oggi devo registrare la rinascita del male anche tra noi. Gli attentati, la guerra alle frontiere, il tentativo di una parte del…

View On WordPress

#attentati#Bratislava#coesistenza#comunismo#demini#dispotismo#dittatura#econimia#Europa#fascismo#Fico#guerra#Huxley#lotta#odio#pace#Pasolini#Russia#sionismo#Slovacchia#teocrazia#Tocqueville#USA#Viaggionell&039;odio#violenza

1 note

·

View note

Text

I was happy to be able to contribute to the University of Louisville’s year-long examination of Alexis de Tocqueville by discussing A Fortnight in the Wilderness. I’ll also be leading a seminar for Kentucky teachers on this text.

youtube

0 notes

Text

"Beyond the Crowd"

Leave it to Alexis de Tocqueville to provide answers for what’s happening in the country right now. I am always amazed at the prescience of the nineteenth century, French observer of American society. But he was not just an observer. He also admired the new republic, which is why he put such hope in her future. However, he was not blind to her flaws, the most pernicious of which was the potential…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Nothing is more wonderful than the art of being free, but nothing is harder to learn how to use than freedom.

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“After having thus taken each individual one by one into its powerful hands, and having molded him as it pleases, the sovereign power extends its arms over the entire society; it covers the surface of society with a network of small, complicated, minute, and uniform rules, which the most original minds and the most vigorous souls cannot break through to go beyond the crowd; it does not break wills, but it softens them, bends them and directs them; it rarely forces action, but it constantly opposes your acting; it does not destroy, it prevents birth; it does not tyrannize, it hinders, it represses, it enervates, it extinguishes, it stupefies, and finally it reduces each nation to being nothing more than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.” - Alexis de Tocqueville

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am delighted by de Tocqueville's interest in the fact that in America, "in places where it is not uncommon to see the absence of what is necessary, you frequently observe the presence of what is not" (car dans lieux, où il n'est pas rare de manquer du nécessaire, le superflu se trouve souvent). (This is specifically about how a man living in an isolated cabin in the woods has a copy of Shakespeare's tragedies and Milton's poems, as well as a muslin curtain and porcelain teapot)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexis de Tocqueville's First Letter on Algeria

Great events have just taken place in Algeria; we can believe that others are still in preparation. So the time is ripe, Monsieur, to do as you wish and tell you what I know about Algiers. I do so all the more willingly because, although there has been much discussion about this country, very little is understood about it...

Read Alexis de Tocqueville's previously unpublished Letter on Algeria, describing the ethnography of the country, on our substack:

https://tikhanovlibrary.substack.com/p/alexis-de-tocquevilles-first-letter

0 notes