#Three genders? Cases? Adjectives agreeing with nouns?

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I couldn't find any German Croatian textbooks that I liked so I got the Teach Yourself one and it's quite good but the funniest thing is that I forgot that English people don't have cases or genders and need those things explained

#langblr#I finished unit 1#And obviously I'm a complete beginner and the grammar is probably going to get more difficult#But I'm so psyched that there are parallels to other languages I know#Three genders? Cases? Adjectives agreeing with nouns?#And some words seem familiar because of Indo-European babeyyyy

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

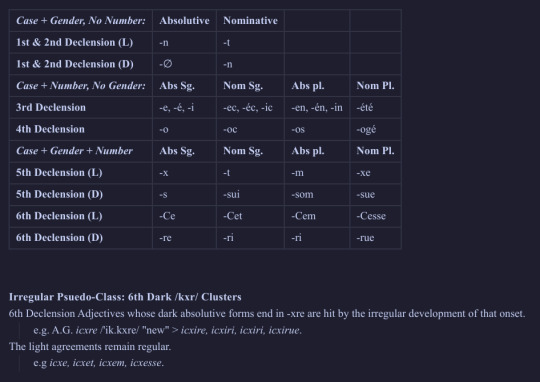

Neat Irregularity In Old Sogoic Adjective Agreement

I think this is the first time I've mentioned it on this blog, but Old Sogoic is a Sellan language (i.e, fairly closely related to High Gavellian), though the Old Sogoic period (c. 850–500 B.P.) came a fair time before the Cadan standardization of High Gavellian that I'm documenting (early centuries A.P.) or even the point where "High Gavellian" became a distinct concept outside of Koine (riight before the turn of the millennium).

I digress. The irregularity here is a splinter from Declension VI detailed down below. As a result of a sound-shift vowel insertion to break up an unwanted sequence at the syllable boundary, the 'irregular' class takes the root (this is romanisation, not ipa, though it is phonologically transparent atm) icx- and simply adds an -ir for gender agreement and then -e/-i/-i/-ue for case and number agreement. It's so nicely agglutinative!

but this is the irregular pattern. compare a similar stem in declension six like sios-. In the light gendered agreement pattern, it matches icx- exactly:

icxe, icxet, icxem, icxesse

siose, sioset, siosem, siosesse

buuut ofc the "expected" dark agreement pattern...

siosire, siosiri, siosiri, siosirue

...is completely incorrect! because that final consonant is only a part of the light stem, for some reason! the dark stem deletes it!

siore, siori, siori, siorue

It's all so very nice. The vowel insertion during the sound shifts on the xre /.kxre/ clusters prevented the consonant loss that hit every single other adjective in the class. Maybe if there were more preservation examples than this one (rather rare) cluster then it'd have spread through analogy/morphological leveling or somesuch, but it hasn't. so it's just an irregular pseudo-class that only retains some super common adjectives (as detailed in the pic, icxe/icxre "new" makes that cut). The rest of them have this fun stem consonant deletion thing going on. Which also means that if you hear a Declension VI adjective in its dark agreement form you've got like zero clue as to what the consonant at the end of its stem is. rip rip.

Again, maybe I'll level that out, but realistically what I'm probably going to do is collapse the adjectives into 2-3 declension classes max. Probably going to move them up into 5-6 as the language gets more (yes yay more) fusional. Unfortunately we've got a billion incoming noun cases (lots of adpositions just went postpositional & suffix mode) that I don't really see the adjectives agreeing with, but at the least that's one place where the marked nominative agreement is going to hold on. Rest of the language (family) is doing its level best to purge itself of any remnant ergativity.

Here's a language intro tangent:

Old Sogoic is somewhat fusional, though sound shifts have rendered its inflection system fairly neutered and highly syncretic. It's undergoing the same areal morpho-phonological reduction pressure that the nigh-isolating High Gavellian emerged from. Given the circumstances it managing to hold on to this much (16 verb inflections, up to 4 noun inflections, up to 8 adjective inflections, grammatical gender & number) is insane.

The adjective classes are weird and I like them a fair amount. The first/second declension distinction is barely a formality and only exists because of One insanely productive derivational suffix (the gods' strongest soldier, good work -on).

It also exists because this analysis lets me line up the adjectival inflection patterns with their cognate noun declension patterns. If Declension II didn't exist then I'd probably have to skip the number anyway.

Otherwise the six declensions are sorted into three pattern groups depending on their agreement behavior. I and II are defective when it comes to number agreement, III & IV don't agree for gender, and then finally V & VI have full agreement in all situations.

Going off what I mentioned earlier but wrote later:

As Old Sogoic evolves into Neo-Sogoic (where its speakers escape the black hole of isolation by ironically isolating the community from the rest of the sprachbund) planning on having it get even more fusional, which means that I'm probably going to have V & VI style patterns of full agreement extend to the entire adjective space. Hooray. This'll mainly favor the absolutive forms, but I won't see if I can't force the case-like suffixes to agglutinate to the adjectives too. That'll get a whole bunch of new agreements in real quick.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introducing: Néndisfas

Consider this post a very brief introduction to my in-progress conlang, Néndisfas.

In summary, Néndisfsho is a fusional language with phonemic pitch-accent, personal agreement in verbs, and split-ergative based on animacy.

Phonology

Consonants

/p/, /b/, /m/, /t/, /d/, /n/, /k/, /g/, /ŋ/, /kʷ/, /gʷ/

/f/, /v/, /s/, /ʃ/, /z/, /xʷ/, /h/

/w/, /j/, /ɾ/, /l/, /ʎ/, /ʟ/

Not much to say here but for the three way /l/, /ʎ/, /ʟ/ distinction held-on from the protolanguage.

Vowels

Five-vowel system with length distinction, making 10 vowels. Not interesting at all here.

Phonotactics

Max syllable: CV(C)(C)(C) / CV(C)#

Indeed, this means that the maximum size of a consonant cluster could be 4-consonants long,

Morphology / Syntax: Grammar

Verbs

Verbs (and predicative adjectives) are simple, comparatively, to the syntactic nonsense going down with nouns.

Verbs take a prefix for perfective and passive, and a suffix for past or present and to agree with the subject in gender (animate, inanimate).

Due to sound changes, verbs fall into one of six categories, but classes II, III, and IV all have alternate forms.

Nouns

Néndisfsho nouns take on one of two genders: Common or Neuter. Common nouns were derived from old animate nouns, and neuter nouns were derived from old mass nouns. The nouns which didn't fit with either were grandfathered in.

Due to sound changes, nouns take on one of six endings depending on their class. Classes I, III, and V have alternate forms.

Nouns also inflect for one of 5 cases: Nominative, Genitive, Accusative, Allative, and Commitative. The Allative, though, is beginning to be used like an Ergative, marking an animate subject of an intransitive verb, and an animate object of a transitive verb.

Take, for instance, the following sentences:

Yés-e váw-i ve-kát-ur-o.

Yessei.C-NOM car.N-ACC PRV.drive.PST.ANIM

"Yessei had driven the car."

Since the car is not animate, Yessei is rendered in the nominative, and the car is rendered in the accusative. In the following sentence, however:

Yés-ivā búm-pe kéht-us

Yessei.C-ALL dark.N-NOM hate.PRES.INAN

"The dark hates Yessei."

Here, the nominative case is reanalyzed as an absolutive, and the allative as an ergative.

This structure could be rewritten with a passive, like

Yés-ivā (búp-ko) ver-kéht-o

Yessei.C-ALL (dark.N-GEN) PASS.hate.PRES.ANIM

"Yessei is hated (by the darkness)."

Here, the genitive marks the agent, and the allative (ergative) marks the subject. Yessei, in this context, is treated as the object of a transitive verb, rather than the subject of an intransitive verb.

The reason this is so messy right now is because the language is in the middle of evolving the ergativity.

Other Notes

Néndisfas has no "true" 2nd or 3rd person pronouns, because pronouns are a completely open class in Néndisfas. The general 1st person pronoun is "gémse, géra, gésho" (I, me, my).

This is probably a language I'll wind up using as a meme language throughout my writing. It originally started as a language used in the deserts of Southern Atepsi, but now it's Yessei's first language, so I decided it can be both. In the context of Meiste, though, this is a long-dead language.

Paging the usual suspects: @quillswriting @oldfashionedidiot @ominous-feychild

Also if y'all have translation suggestions don't hesitate to drop them in my asks or as a reply/reblog to this post lol.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Might as well actually post something in my conlang. Taijrumur was originally intended as a fan-language for the Zonai race from The Legend of Zelda. Fairly quickly, however, I decided that the æsthetic wasn't quite right for that, but I still basically like what the language has going for it, so it's become its own thing (I might go back to the whole Zonai language thing later, but I'm having fun with this one for right now).

It's still young, with a fairly small vocabulary, so my examples are very basic, but this is a care for someone who is not me. I'll maybe talk about phonetics later, but this should give a fair example of the æsthetic.

Qanij damjuusur o'suja iimvojra.

The King of Darkness is my friend.

Double vowels are long, <j> has its IPA value, as does <q>.

The most notable thing this sentence shows off is that personal possession is marked on the verb. Technically speaking, verbs do not conjugate for tense. Instead, a verb conjugates for one of (so far) three modalities: infinitive (name subject to change, really, this is just a basic realis or indicative mood); hypothetical; and interrogative.

A set of dative prefixes on the verb show personal possession, though as one can probably guess from my example, there's also a possessive case. It's just not used for personal possessors (I haven't decided too much on the why, or if the possessive applied to personal pronouns has a slightly different interpretation that one force the use of these datives; that's later me's problem).

Nouns are gendered as either animate or inanimate with no significant marking for either. Adjectives however agree with their nouns in gender, as do in fact, verbs (which otherwise don't particularly care for person marking). What constitutes animate versus inanimate is largely cultural however, and some speakers might break the expected pattern by preferring one over the other, especially where abstractions are concerned.

Qanij jaaluq ojvojsaiva?

Is our king dying?

So the two suffixes marked in green (-uq and -a) agree with the subject in animacy, the oj- prefix marks the possessor (which can be ambiguous in transitive verbs, though it can be clarified if need be). The suffix -saiv marks the interrogative mood.

There's no particular reason that I chose to make the verb 'to die' an adjective, it just sort of happened.

I apologize for the color-coding. It was an easier way of illustrating the relationships between the two without me fighting with traditional glossing conventions.

My only goal with this language is to have a functional writing system designed before November ends. And maybe to translate some texts that don't sound like Dead Cells lore. Coined a word for 'cute' before I started typing (si'a, by the way, after one of my cats), so that's a step in a direction which appears to be vaguely right.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

MASTERING ARABIC SYNTAX: A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE

Ever found yourself puzzled by the complexity of Arabic syntax? You’re not alone. Many learners find Arabic syntax challenging, but with the right guidance, it can become as straightforward as building a puzzle. Think of Arabic syntax as the framework of a house: once you understand the foundation, everything else falls into place. This guide aims to simplify the intricacies of Arabic syntax and make it accessible for everyone.

Understanding Arabic Syntax

Arabic syntax is the set of rules that governs the structure of sentences. It dictates how words are arranged and how they interact with each other. Just like in English, Arabic sentences are made up of subjects, verbs, and objects, but the order and form can vary significantly.

The Basics of Sentence Structure

In Arabic, the typical sentence structure can be either Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) or Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). For instance:

VSO: “قرأ الطالب الكتاب” (The student read the book).

SVO: “الطالب قرأ الكتاب” (The student read the book).

Understanding these patterns is crucial for constructing coherent sentences.

Nouns and Their Roles

Nouns in Arabic can be subjects, objects, or complements. They come in different forms, including definite and indefinite. For example:

Definite Noun: “الكتاب” (the book)

Indefinite Noun: “كتاب” (a book)

Nouns also take different forms based on their grammatical case, which indicates their role in the sentence (subject, object, etc.).

Verbs and Verb Forms

Arabic verbs are rich and complex, with root-based structures that change based on tense, mood, and voice. The three main tenses are past, present, and future. For example:

Past: “كتب” (he wrote)

Present: “يكتب” (he writes)

Future: “سيكتب” (he will write)

Subject-Verb Agreement

In Arabic, the verb must agree with the subject in both gender and number. For instance:

Masculine Singular: “كتب الرجل” (The man wrote)

Feminine Singular: “كتبت المرأة” (The woman wrote)

Masculine Plural: “كتب الرجال” (The men wrote)

Feminine Plural: “كتبت النساء” (The women wrote)

Object Placement

Objects in Arabic can either follow the verb directly or be placed after the subject. Both forms are grammatically correct, but the meaning or emphasis can change. For example:

“قرأت الكتاب” (I read the book)

“الكتاب قرأته” (The book, I read it)

Adjectives and Their Agreement

Adjectives in Arabic must agree with the noun they describe in gender, number, and case. For example:

Masculine Singular: “كتاب كبير” (a big book)

Feminine Singular: “سيارة كبيرة” (a big car)

Masculine Plural: “كتب كبيرة” (big books)

Feminine Plural: “سيارات كبيرة” (big cars)

Prepositions in Arabic

Prepositions are used to indicate relationships between words in a sentence. Common prepositions include “في” (in), “على” (on), and “مع” (with). For example:

“الكتاب على الطاولة” (The book is on the table)

“ذهبت إلى المدرسة” (I went to school)

Conjunctions and Sentence Linking

Conjunctions like “و” (and), “أو” (or), and “لكن” (but) are essential for linking sentences and creating complex structures. For example:

“ذهبت إلى المدرسة وقرأت الكتاب” (I went to school and read the book)

“أريد القهوة أو الشاي” (I want coffee or tea)

Common Syntax Errors

Common errors in Arabic syntax often involve incorrect verb conjugation, noun-adjective agreement, or misuse of prepositions. Understanding these pitfalls can help you avoid them. For example:

Incorrect: “الكتاب كبير” (The book big)

Correct: “الكتاب الكبير” (The big book)

Practice Exercises

Practice is key to mastering Arabic syntax. Try constructing sentences using different structures and roles. Here are a few exercises to get you started:

Create sentences using VSO and SVO structures.

Conjugate verbs in different tenses and use them in sentences.

Practice noun-adjective agreement with various nouns and adjectives.

Tips for Mastering Arabic Syntax

Practice Regularly: Consistency is key.

Study Real-Life Examples: Reading Arabic texts can provide context and understanding.

Use Flashcards: They can help reinforce vocabulary and structures.

Get Feedback: Engage with native speakers or tutors for constructive feedback.

Resources for Further Learning

Books: “Arabic Grammar: A First Workbook” by Mohamed Fathy.

Online Courses: Coursera offers Arabic language courses.

Apps: Duolingo and Memrise have Arabic learning modules.

Conclusion

Mastering Arabic syntax is a journey that requires practice and patience. By understanding the fundamental rules and practicing regularly, you can build a strong foundation in Arabic. Remember, like any new skill, consistency and a positive attitude will take you far.

FAQs

What is the basic word order in Arabic sentences? Arabic sentences typically follow Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) or Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) order.

How do verbs change in Arabic? Verbs in Arabic change based on tense, mood, and voice, with specific forms for past, present, and future tenses.

What are common errors in Arabic syntax? Common errors include incorrect verb conjugation, noun-adjective agreement, and misuse of prepositions.

How important is practice in learning Arabic syntax? Practice is crucial as it reinforces understanding and helps internalize rules through consistent application.

Where can I find resources to learn Arabic syntax? Books, online courses, and language learning apps are great resources. Engaging with native speakers also provides practical experience.

By following this guide, you’ll find that Arabic syntax is not as daunting as it seems. Happy learning!

Don’t forget to visit our youtube channel !

Meet Mahmoud Reda, a seasoned Arabic language tutor with a wealth of experience spanning over a decade. Specializing in teaching Arabic and Quran to non-native speakers, Mahmoud has earned a reputation for his exceptional expertise and dedication to his students' success.

Mahmoud's educational journey led him to graduate from the renowned "Arabic Language" College at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Holding the esteemed title of Hafiz and possessing Igaza, Mahmoud's qualifications underscore his deep understanding and mastery of the Arabic language.

Born and raised in Egypt, Mahmoud's cultural background infuses his teaching approach with authenticity and passion. His lifelong love for Arabic makes him a natural educator, effortlessly connecting with learners from diverse backgrounds.

What sets Mahmoud apart is his native proficiency in Egyptian Arabic, ensuring clear and concise language instruction. With over 10 years of teaching experience, Mahmoud customizes lessons to cater to individual learning styles, making the journey to fluency both engaging and effective.

Ready to embark on your Arabic learning journey? Connect with Mahmoud Reda at [email protected] for online Arabic and Quran lessons. Start your exploration of the language today and unlock a world of opportunities with Mahmoud as your trusted guide.

In conclusion, Mahmoud Reda's expertise and passion make him the ideal mentor for anyone seeking to master Arabic. With his guidance, language learning becomes an enriching experience, empowering students to communicate with confidence and fluency. Don't miss the chance to learn from Mahmoud Reda and discover the beauty of the Arabic language.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

kaɣak /kaˈʁak/, noun animate, pl. kaɣakuor

tall person

diem /di̯em/, noun animate, pl. demuor

big animal

bezek /beˈzek/, noun inanimate, pl. bezeki

big thing

Why three words? Well, there's no distinct class of adjectives in Lamáya, you use descriptive nouns in apposition, agreeing in case, number and gender with the 'head'. Sometimes gender is suppletive, and in this particular case there is also a distinction in the animates between humans and animals.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old English is so weird. Like, it is genuinely nothing like Modern English.

Modern English: no grammatical gender; nouns are only inflected in the plural and in the genitive case (separately); adjectives are not inflected; verbs are only conjugated for the third-person present, the past tense, and participles (aside from specific irregular verbs)

Old English: three (3) grammatical genders; four (4) cases, for each of which every noun has a singular and plural form; by my count, nine (9) noun classes that all inflect differently; first- and second-person personal pronouns for referring to exactly two of something; the definite articles and demonstrative pronouns have to agree with nouns in gender, number, and case; adjectives are inflected for gender, number, and case in one of two possible ways for each combination; a secret fifth case for definite articles, demonstratives, and in certain situations adjectives; four (4) categories of verbs further divided into classes, all of which conjugate differently for person, number, mood, and tense

The only resemblance I can see between them is that some OE words vaguely resemble their modern descendants. What French influence does to a mf.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Understanding Plurals in Arabic

When learning Arabic, one of the most fascinating aspects to explore is its plural forms. Unlike English, which typically forms plurals by adding "s" or "es," Arabic has a more complex and varied system for making words plural. The plural forms can sometimes be irregular, and they depend on the word's gender, structure, and sometimes its meaning. Let's dive into plural in Arabic - Arabic plurals to get a better understanding.

In Arabic, plurals are generally categorized into two main types: the sound plural (جمع سالم) and the broken plural (جمع التكسير). Both types have their own rules and applications.

Sound Plurals (جمع سالم)

The sound plural is more straightforward and follows consistent rules. It is typically formed by adding specific endings to the singular form of the word. There are two main types of sound plurals in Arabic: the masculine sound plural and the feminine sound plural.

Masculine Sound Plural: This is formed by adding -ون (un) or -ين (in) to the singular. The suffix depends on the grammatical case of the noun. Example:

معلّم (teacher) becomes معلّمون (teachers) in the nominative case and معلّمين in the accusative or genitive cases.

Feminine Sound Plural: For feminine nouns, the plural is formed by adding -ات (at) to the singular. Example:

طالبة (female student) becomes طالبات (female students).

Broken Plurals (جمع التكسير)

Broken plurals are much more complicated than sound plurals. These plurals do not follow a specific, predictable rule. Instead, they involve changes in the structure of the word, such as altering the internal vowels or consonants. The patterns for broken plurals can vary greatly, and they often need to be memorized.

For example:

كتاب (book) becomes كتب (books).

طفل (child) becomes أطفال (children).

This irregularity makes it harder to form the plural correctly, and learners of Arabic often find broken plurals to be one of the most challenging aspects of the language.

Dual Forms (المثنى)

In Arabic, there is also a specific form for the "dual," which refers to two of something. To form the dual, the singular word is modified by adding -ان (an) or -ين (in) for masculine nouns, and -تانِ (tan) or -تينِ (tin) for feminine nouns. The dual form is used specifically to refer to two people, objects, or things.

Example:

كتاب (book) becomes كتابانِ (two books).

طالبة (female student) becomes طالبتانِ (two female students).

This dual form is unique to Arabic and is not something commonly found in many other languages.

Plurals in Context

Plurals in Arabic don’t just affect nouns; they also change the forms of adjectives and verbs. Adjectives in Arabic must agree in gender and number with the noun they describe, meaning that a plural noun will require a plural adjective. For instance:

الولد طويل (The boy is tall) becomes الأولاد طويلون (The boys are tall).

Similarly, verbs also agree with the subject in number. For example, the verb ذهب (he went) becomes ذهبوا (they went) when referring to a group of people.

Tips for Learning Arabic Plurals

Start with sound plurals: Because they follow consistent rules, sound plurals are easier to learn. Start by memorizing these patterns before diving into the more complicated broken plurals.

Focus on frequently used words: Learn the broken plurals of commonly used nouns first. This will make it easier to get a feel for the patterns.

Practice in context: Try to use plural forms in real conversations or writing exercises. This will help you get used to how plurals fit into sentences.

Memorize common broken plural patterns: While broken plurals don’t follow set rules, there are certain recurring patterns (like -ات for many feminine words) that can help you.

In summary, plural in Arabic - Arabic plurals are an essential part of mastering the language, and understanding both sound and broken plurals is key to speaking and writing correctly. While broken plurals may seem tricky at first, with practice, you’ll be able to spot the patterns and use them confidently. So don’t be discouraged—just keep learning, and the plurals will soon become second nature!

0 notes

Text

Understanding the Essentials of Arabic Grammar

Arabic grammar is a fascinating and intricate system that forms the backbone of the Arabic language. It encompasses various rules and structures that govern how words are combined to convey meaning. Whether you're learning Arabic for personal enrichment, travel, or a deeper understanding of the Quran, grasping the basics of Arabic grammar can significantly enhance your language skills.

The Foundations of Arabic Grammar

At its core, Arabic grammar is based on three primary components: nouns, verbs, and particles. Understanding these elements is crucial for constructing sentences.

Nouns (Ism): Nouns in Arabic can be either definite or indefinite. A definite noun typically has a specific article, while an indefinite noun does not. For example, "the book" translates to "الكتاب" (al-kitab), while "a book" translates to "كتاب" (kitab). Nouns also have gender, either masculine or feminine, and can change form based on case and number.

Verbs (Fi'l): Arabic verbs are unique because they are conjugated based on tense, mood, and the subject's person and number. For instance, the verb "to write" is "كتب" (kataba) in its base form. When you conjugate it, it changes based on who is performing the action and when.

Particles (Harakat): Particles include prepositions, conjunctions, and other small words that help link phrases and clauses. They play a vital role in establishing relationships between different parts of a sentence. For example, the word "و" (wa) means "and," connecting two ideas or items.

Sentence Structure

Arabic sentences typically follow a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) structure, although variations do exist. For example, "The boy reads a book" would be structured in Arabic as "يقرأ الولد كتابًا" (yaqra' al-walad kitabaan). This shows the subject ("الولد"), followed by the verb ("يقرأ") and then the object ("كتابًا").

Gender and Number

Understanding gender and number is crucial in Arabic grammar. Every noun has a gender, and adjectives must agree with the noun they describe. Additionally, nouns can be singular, dual, or plural. In Arabic, the plural form often involves changing the word's structure significantly, rather than simply adding an "s" as in English.

Cases in Arabic Grammar

Arabic nouns can take on different cases, primarily nominative, accusative, and genitive. Each case has its own markers that indicate the role of the noun in a sentence. For example, a noun in the nominative case usually serves as the subject, while a noun in the accusative case may serve as the object of a verb.

The Importance of Vowel Markings

Vowel markings in Arabic, known as Tashkeel, are essential for understanding pronunciation and meaning. These markings indicate short vowels and help clarify how words should be read, especially in religious texts like the Quran. Learning to read with Tashkeel is beneficial for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of Arabic and its nuances.

Learning Resources

For those interested in learning Arabic and exploring its grammar in depth, various resources are available. Websites such as Shaykhi provide valuable tools for learners, offering lessons on grammar, vocabulary, and even Quranic studies. Engaging with these resources can help you develop a solid foundation in Arabic, making your learning journey more enjoyable and effective.

Conclusion

Arabic grammar is more than just a set of rules; it is the key to understanding a language that holds great cultural and historical significance. Whether your interest lies in conversational Arabic or studying the Quran, a strong grasp of grammar will undoubtedly enhance your skills. Embrace the challenge of learning Arabic grammar, and consider exploring resources like Shaykhi to guide you on this rewarding journey

0 notes

Text

English grammar

H. USES OF PRONOUNS

85. When a Pronoun is used as the complement of the Verb 'to be', it should be in the nominative case.

Incorrect- If I were him, I would not do it. Correct- If I were he, I would not do it.

86. When the Pronoun is used as the object of a Verb or of a Preposition, it should be in the objective case.

1. Incorrect- Let you and I do it.

Correct- Let you and me do it.

2. Incorrect- These presents are for you and I. Correct- These presents are for you and me.

87. Emphatic Pronouns cannot stand alone as Subjects

Incorrect- Himself did it.

Correct- He himself did it.

88. The Indefinite Pronoun 'one' should be used throughout if used at all.

Incorrect- One must not boast of his own success.

Correct- One must not boast of one's own success.

89. 'Either' or 'neither' is used only in speaking of two persons or things; 'any, 'no one' and 'none' is used in speaking of more than two.

1. Incorrect- Anyone of these two roads leads to the railway station.

Correct-Either of these two roads leads to the railway station.

2. Incorrect- Neither of these three boys did his homework.

Correct- No one of these three boys did his homework.

90. 'Each other' is used in speaking of two persons or things; 'one an-other' is used in speaking of more than two.

Incorrect- The two brothers loved one another.

Correct- The two brothers loved each other.

91. A Noun or Pronoun governing a Gerund should be put in the possessive case.

Incorrect- Please excuse me being late.

Correct- Please excuse my being late.

92. A Pronoun must agree with its antecedent in person, number and gender.

Incorrect- Each of these boys has done their homework.

Correct- Each of these boys has done his homework.

93. When two or more Singular Nouns are joined by 'and', the Pronoun used for them must be in Plural.

Incorrect- Both Raju and Ravi have done his homework.

Correct- Both Raju and Ravi have done their homework.

94. When two or more Singular Nouns are joined by 'and' refer to the same person or thing, a Pronoun used for them must be in the singular.

Incorrect- The collector and District Magistrate is not negligent in their duty.

Correct- The collector and District Magistrate is not negligent in his duty.

95. When two or more singular nouns are joined by 'or' or 'nor', 'either... or', 'neither.. nor, the Pronoun used for them should be in the singular.

Incorrect- Neither Ravi nor Raju has done their homework.

Correct- Neither Ravi nor Raju has done his homework.

96. When two or more singular Pronouns of different persons come together, the Pronoun of second per-son singular (you) comes first, the pronoun of the first person singular (1) comes last and the pronoun of the third person singular (he) comes in between.

Incorrect- I, You and he must work together..

Correct-You, he and I must work together.

97. When two or more plural Pro-nouns of different persons come together first person plural (we) comes first, then second person plural (you) and last of all third person plural (they).

Incorrect You, they and we must work together..

Correct-We, you and they must work together.

98. The Relative Pronoun who is in a subjective case, whereas whom is in objective case. Therefore, for who there must be a Finite Verb in the sentence. Or otherwise, when whom (Object) is used in the sentence and there is more Finite Verb's than the number of Subjects in the sentence, then whom should be changed into who (Subject).

For example,

Incorrect- The doctor whom came here was Ram's brother.

Correct-The doctor who came here was Ram's brother.

99. With Superlative Degree Adjective, only, none, all etc., as Relative Pronoun we use that and not which or who.

For example,

Incorrect- All which glitters is not gold.

Correct- All that glitters is not gold.

100. After let, if a Pronoun is used, that Pronoun must be in the Objective Case.

For example,

Incorrect- Let he go there.

Correct- Let him go there.

0 notes

Text

Hello @voidismyhome , I found a page in Britannica which describes in a really concise way what differences to generally expect in Modern Greek syntax and vocabulary compared to Ancient Greek. For how short it is, I find it remarkably good. It might be useful to you.

Much of the inflectional apparatus of the ancient language is retained in Modern Greek. Nouns may be singular or plural—the dual is lost—and all dialects distinguish a nominative (subject) case and accusative (object) case. A noun modifying a second noun is expressed by the genitive case except in the north, where a prepositional phrase is usually preferred*. The indirect object is also expressed by the genitive case (or by the preposition se ‘to,’ which governs the accusative, as do all prepositions).

The ancient categorization of nouns into masculine, feminine, and neuter survives intact, and adjectives agree in gender, number, and case with their nouns, as do the articles (o ‘the,’ enas ‘a’). In general, pronouns exhibit the same categories as nouns, but the relative pronoun pu is invariant, its relation to its own clause being expressed when necessary by a personal pronoun in the appropriate case: i yinéka pu tin ídhe to korítsi ‘the woman pu her saw the girl’ (i.e., ‘the woman whom the girl saw’).

The verb is inflected for mood (indicative, subjunctive, imperative), aspect (perfective, imperfective), voice (active, passive), tense (present, past), and person (first, second, and third, singular and plural). The future is expressed by a particle tha (from earlier thé[o] na ‘[I] want to’) followed by a finite verb—e.g., tha grápho ‘I will write.’ Formally, the finite forms of the verb (those with personal endings) consist of a stem + (optionally) the perfective aspect marker (-s- in active, -th- in passive) + personal ending (indicating person, tense, mood, voice). Past forms are prefixed by e- (the “augment”), usually lost in mainland dialects when unstressed. There are also two nonfinite forms, an indeclinable present active participle in -ondas (ghráfondas ‘writing’), and a past passive one in -ménos (kurazménos ‘tired’).

Aspectual differences play a crucial role. Roughly, the perfective marker indicates completed, momentary action; its absence signifies an action viewed as incomplete, continuous, or repeated. Thus the imperfective imperative ghráphe might mean ‘start writing!’ or ‘write regularly!’ while ghrápse means rather ‘write down! (on a particular occasion).’ Compare also tha ghrápho ‘I’ll be writing’ but tha ghrápso ‘I’ll write (once).’ The difference is sometimes represented lexically in English: ákuye ‘he listened’ and ákuse ‘he heard.’ The passive forms are largely confined to certain verbs active in meaning** like érkhome ‘I come,’ fováme ‘I am afraid,’ and reciprocal usages (filyóndusan ‘they were kissing’).

The most common form of derivation is by suffixation; derivation by prefixation is limited mainly to verbs. On the other hand, compound formation is rich. Three morphological types of compounds can be distinguished, as reflected also in their stressing—thus, stem + stem compounds—e.g., palyófilos ‘old friend’ (o is the compound vowel) or khortofághos ‘vegetarian’; stem + word compounds—e.g., palyofílos ‘lousy friend’ (compare fílos ‘friend’); and the newly borrowed formation, word + word compounds—e.g., pedhí thávma as English ‘boy wonder.’ There is no infinitive; ancient constructions involving it are usually replaced by na (from ancient hína ‘so that’) + subjunctive. Thus thélo na ghrápso ‘I want to write,’ borí na ghrápsi ‘he can write.’ Subordinate statement is introduced by óti or pos (léi óti févghi ‘he says that he is leaving’). Unlike English, Greek (because of its inflectional system) shows flexible word order even in the simplest sentences. Further, as in Italian, the subject of a sentence may be omitted.

The vast majority of Demotic words are inherited from Ancient Greek, although quite often with changed meaning***—e.g., filó ‘I kiss’ (originally ‘love’), trógho ‘I eat’ (from ‘nibble’), kóri ‘daughter’ (from ‘girl’). Many others represent unattested combinations of ancient roots and affixes; others enter Demotic via Katharevusa: musío ‘museum,’ stikhío ‘element’ (but inherited stikhyó ‘ghost’), ekteló ‘I execute.’ In addition, there are more than 2,000 words in common use drawn from Italian and Turkish (accounting for about a third each), and from Latin, French, and, increasingly, English. The Latin, Italian, and Turkish elements (mostly nouns) acquire Greek inflections (from Italian síghuros ‘sure,’ servitóros ‘servant,’ from Turkish zóri ‘force,’ khasápis ‘butcher’), while more recent loans from French and English remain unintegrated (spor ‘sport,’ bar ‘bar,’ asansér ‘elevator,’ futból ‘football,’ kompyúter ‘computer,’ ténis ‘tennis’).

A couple of notes:

* I could be wrong but I am a little sceptical about this claim that in the north the second noun being in genitive is replaced with a prepositional phrase. Both ways exist and are used in either northern or southern Greek. Or I had never noticed it? Idk

** It’s not passive form used for active meanings, this in Greek is mediopassive, for instance, erkhome “come” essentially means “bring myself to some place” so it is an act done to oneself, fovame (I fear) and most emotions are also (medio)passive as the self is the receptor of the emotion.

***The meaning has shifted in several occasions however it is an additional meaning usually and not a fully changed one. For example, stikhio is both element AND ghost, ektelo is both execute a person AND perform, complete a process etc

So some tips I can give, with the help of the above:

Infinitive means ancient and its replacement with subjunctive means modern.

If you use tha before a future verb, that’s modern.

Dative means ancient and its replacement by either accusative or genitive means modern.

A lot of use of compound words indicates it’s modern.

A very liberal placement of words (flexible syntax) and a use of a lot of figurative speech indicates it’s likely modern.

If it’s modern the word ends in a vowel or n or s or rarely r. If it’s Ancient it can additionally end in x and ps. Obviously, I mean the equivalent Greek letters!

Generally pronouns follow the verb in Ancient Greek but usually precede it in Standard Modern Greek (not in some dialects though).

If you drop definite articles unless you want to emphasise the precision, that indicates Ancient. If you do the opposite, meaning if you always use definite articles except when you really want to stress the vagueness, that’s Modern.

Hope that helped any! Creating your own language is fascinating, I had done that too in the past but more like a code language and not with a proper design of grammar and syntax.

Feels like a lot of work to ask this

but next time you refer to some etymology or word used as Ancient Greek, please kindly consider to check out whether this word is extant and used in Modern Greek. If you refer to all words as Ancient Greek, you spread the usually false impression that these words are dead, only revived thanks to English and other western scientific terminology (while they might as well be everyday words for the Greek speakers), you obstruct a chance of exposure to Modern Greek which is viewed as totally disconnected and irrelevant, and you strip it from its lingual legacy.

So, if a word has indeed fallen out of use, by all means, call it what it is, Ancient Greek. If it’s only used in Modern Greek, which is a possibility you will likely never stumble on as Modern Greek roots barely exist at all and they are just colloquial epithets (which is also why it doesn’t make much sense to emphatically distinct a root as Ancient because there’s little else it can be anyway), call it Modern Greek. (Always talking about Greek roots, this is not about loanwords or foreign roots.)

If however it exists both in Ancient and survives in Modern Greek, which is 90% of the time, just call it what it really is. Greek.

Another reason it is very unlikely for you to be referring to exclusively Ancient Greek words that are dead in Modern Greek is because the Greek words you usually refer to are words that passed from Latin and Medieval Greek to the western languages. If a Greek word survived well into Medieval Greek and / or passed to Latin, then it has 99% of the time survived into Modern Greek. Exclusively Ancient Greek words that have fallen out of use are usually Homeric and Archaic words from non-Ionic dialects that were already fading in Classical and early Hellenistic times. So the odds of you referring to such words, unless you are a linguist of archaic non-Ionic Greek, are very very slim.

And if it’s too much work to ask (how much time do you spend mentioning Greek etymology though?!), then again just call it Greek because you can’t go wrong with this and you save yourself from an extra word. It’s that easy and is the safest choice.

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old Sogoic Declension Paradigm

Nouns & Adjectives. The entire thing as it currently exists. This is all the romanisation, not IPA.

Noun Declension

Stem Notes:

First declension and Regular-Grade 5th have stems that can end in any vowel, whereas the stems for the others all end in consonants.

Sort of. What's really going on is that the final vowel of other declension class stems(?) is limited in a way that it's not for those two.

Also see how it's not technically limited for the 4th, though the Nominative Plural for that one collapses all the vowels together in the end.

Agreement Notes:

1st & 2nd Declension have a large number of nouns in them, but they're no longer productive for new nouns by the time of Old Sogoic. They're also defective for number.

1st is almost always Light-gendered, 2nd almost always Dark-Gendered.

3rd and 4th declension are the first two "full" ones. Each contain a mix of Light and Dark-gendered words.

4th declension is the general dumping ground for new words/loans whose perceived stems seem to end with a vowel. Unless that vowel is i, é, e, or u, in which case it goes into the 3rd (first three) or the 5th (-u).

5th declension leans heavily Dark-gendered. New lexemes whose stems are perceived to end in a consonant tend to be sorted into this declension. Usually the regular grade.

Those new lexemes are a drop in the bucket compared to the leveling shifts that are responsible for the vast majority of the Light gendered words in the 5th. This still isn't too many, though - by the end of the Old Sogoic period the Darks still outnumber the Lights by some 5:1.

Adjective Declension

i've already posted this chart, but for completion's sake:

Weird weird decisions were made when deciding what "counts" as a proper declension distinction. The hammer ultimately came down on making them line up with the nouns as much as possible.

1st & 2nd declension stems end in a vowel. For the first declension, this vowel is always -o or -u, while all other vowel endings are sorted into in the second.

The second declension can also be seen as a "defective first," in that it doesn't accept newly derived members. Adding the derivational suffix -on/-én/-eun is the most productive method of deriving adjectives from nouns well into the Old Sogoic Period.

Which of the three versions of the suffix an adjective uses is decided by a whole bunch of historical sound shift considerations that this post is already getting too long for. But enough transparent derivations exist such that the three are all decently acceptable. The other that they're given in (on > én > eun) is by how common they are. smth like a 50/30/20 percent split in usage.

3rd and 4th declension stems also end in vowels, -e/-i for the third and all others for the fourth. Though there are many common adjectives in these declensions, they are not as common as the first.

3rd/4th derivations get more common in formal, literary, or poetic contexts, few as there are (this is a fairly low-prestige lect), due to their case agreement allowing for more flexible word order.

But at that point why not use the acrolect, right? So it's a very small niche thing.

The 5th and 6th declensions are the big complicated monsters that agree for absolutely everything. They're fusional relexes of the much more extensive adjective agreement system in the acrolect, as a result of whom they're still very very common.

As you get further into the basolect out in the sticks you'll find novel replacements that don't have to agree with everything, but at least for the Old Sogoic period the prestige dialect loves these adjectives. Intonation isn't really there, and basolect O.S. isn't finished cooking its topic-prominence grammar structures yet, so for now the benefits of free word order are here acting like an anchor upon the lect.

Not much else to say, really. Grammatical gender will probably hold on in the Sogoic line longer than it holds on everywhere else, but once these adjective classes collapse and the articles finish withering away. It's so over for grammatical gender in the Sellan langs. Maybe. We'll see. It'd also be really funny if this language's descendants were trucking along with gender 1200 years after all its relatives dropped it, though.

Here are some adjective examples:

#old sogoic#gavellian family#i'm thinking of nasal vowelifying coda -n and glottal stop > deletioning coda -t#really just cook this disaster syncretic paradigm to that well-done state#i wish to know how far i can get away with taking it

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Languages of the world

Michif (michif)

Basic facts

Number of native speakers: 730

Spoken in: Canada, United States

Script: Latin, 24 letters

Grammatical cases: 0

Linguistic typology: agglutinative, SVO/SOV

Language family: Algic, Algonquian-Blackfoot, Algonquian, Cree-Montagnais-Naslapi, Cree, Plains Creeic

Number of dialects: 3

History

19th century - Michif develops as a combination of Plains Cree and Métis French

2004 - a writing system is proposed

Writing system and pronunciation

These are the letters that make up the script: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p r s t u v w y z.

-Q- and -x- are only used in loanwords. Vowels are doubled to show that they are long and followed by -ñ- to mark their nasality.

Grammar

Nouns have two genders (masculine and feminine). They are almost always accompanied by a French-origin determiner or a possessive.

Adjectives are of French origin and work in a similar way to how they do in French. Only pre-nominal ones agree in gender.

On the other hand, verbs are mostly of Cree origin. They are conjugated for tense, mood, voice, person, and number.

Dialects

There are three dialects: Northern Michif, Southern Michif, and Michif French. Northern Michif is heavily Cree, while the latter is very influenced by French.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Nature of the German Adjective

In this part of the series, we’ll take a look at the german adjective! The grammar behind adjectives are very, well... a bit complex. But I’ll try my best to explain it.

Three Types

First off, there are three different types of adjectives: predicative (prädikative), adverbs (adverbiale), and attributive.

Predicative adjectives and adverbs maintain the same and do not change and are both placed behind the verb. The difference between the two has to do with which verb is present. When they are placed behind the verbs: “sein”, “bleiben”, “werden” — they are predicative adjectives. And when they are placed behind any other verb they are predicative adverbs.

Ex. predicative adjective Der Baum ist grün.

Ex. predicative adverb Der Baum wächst grün.

The last type of adjective is attributive adjectives. These are the ones you’re gonna have to worry about. The attributive adjectives are placed between the article and the noun. Depending on the noun’s gender, number, and case we have to decline them differently, which is also called “adjective agreement��. This gives us over a hundred different possibilities (many of whom look alike but still- it’s a lot). Let’s look at the declension of the attributive adjectives.

Adjective Agreement

If you have seen my post on nouns (or if you’ve already become familiar with the concept) you are aware of cases. Adjective agreement is when the adjective conjugates, or declines, according to the noun’s gender, number, and case.

Remember the table above? Well this is gonna get a lot more complicated. When declining an adjective it is essential to know what type of article you’re using. What do I mean by this? There are definite articles and indefinite articles as well as the option of not using an article. Depending on which of these are present, the adjective will decline differently. Not only that but like the table above, the declension depends on the gender, case, and number. Let’s look at the table in all it’s glory:

As we see; it’s something. But if you look closely it’s actually not as hard as it seems since many of them actually look alike (which gives us less to remember). I made the tables down bellow to give you an example of how the adjective “nett” would agree in different scenarios. I imagine it’ll be a lot easier after seeing it in action.

Exceptions to these rules are:

- Adjectives that end with “e” already, do not add a second “e”. Ex. leise: leiser Baum (not: leiseer Baum)

- When adjectives end in “el” we take away the “e”, leaving the “l” alone before adding the corresponding ending. Ex. dunkel: dunkler Baum (not: dunkeler Baum)

- And when adjectives end in “[any vowel] + er” we, again, take away the “e” before adding the corresponding ending. Ex. teuer: teurer Baum (not: teuerer Baum)

Comparative Forms

In German, we can decline adjectives (just like in English) to change their impact. An example in English would be: good, better, best. Or: nice, nicer, nicest. These different forms are called the comparative forms.

There are three comparative forms: positive, comparative, and superlative.

The positive form is the regular form of the noun: ex. grün. (green)

The comparative form is the form we compare something with, in this form we add “-er” at the end: ex. grüner. (greener)

The superlative form is the ultimate form an adjective can take. Depending on whether it is behind a verb or before a noun it looks different. If it is behind a verb it takes the ending “-sten” or “-esten” (depending on what fits best) and we also have either the definite article or “am” before: ex. am grünsten (greenest) If the adjective is before the noun it is a bit more complicated. Whether the noun in question is feminine or masculine/neuter the adjective will agree accordingly. “-st” is added when the noun is masculine/neuter and “-ste” is added when it’s feminine. On top of that, the adjective also agrees with the noun’s case and whether the article is definite, indefinite or if there is any article. So you also add the ending according to the table listed above ↑.

~ Summary ~

— There are three types of verbs: predicative (prädikative), adverbs (adverbiale), and attributive. — Attributive adjectives are the ones declining, also known as adjective agreement, depending on the noun’s gender, case, and number as well as which type of article is present:

— Comparative forms change the impact of the adjective. — There are three comparative forms in German: positive (normal) form, comparative (compare) form, and superlative (ultimate) form. — Comparative form adds “-er“ at the end of the adjective. — Behind a verb; superlative adds “-sten” or “-esten” at the end and “am“ is placed before it. — Before a noun; superlative adds “-st” (m/n) or “-ste” (f), on top of that it also agrees with the noun’s gender, case, and number as well as which type of article is present so you add the corresponding ending on top of that.

#the nature of german#german#learning german#german langblr#deutsch#deutschlernen#deutsch lernen#deutsch langblr#language learning#german grammar

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

MASTER THE BASICS OF ARABIC GRAMMAR

Are you ready to dive into the fascinating world of Arabic grammar? Whether you’re a beginner or looking to refresh your knowledge, mastering the basics of Arabic grammar is a crucial step towards fluency. In this article, we’ll break down the essential components of Arabic grammar in a way that’s easy to understand and apply.

Introduction

Arabic grammar may seem daunting at first, but with a structured approach, you can master it step by step. Think of it like building a house; you start with a strong foundation and gradually add more layers. Let’s start laying those bricks!

The Arabic Alphabet

The foundation of Arabic grammar is the Arabic alphabet. Arabic is written from right to left and consists of 28 letters. Each letter has four forms: isolated, initial, medial, and final. Getting familiar with these letters and their forms is your first step.

Arabic Pronouns

Pronouns in Arabic are used to indicate the subject or object in a sentence. They vary based on gender, number (singular, dual, and plural), and formality. Here are the basic personal pronouns:

أنا (ana) – I

أنتَ (anta) – You (male)

أنتِ (anti) – You (female)

هو (huwa) – He

هي (hiya) – She

Nouns and Gender

Arabic nouns are classified by gender: masculine or feminine. Generally, nouns ending in “ة” (taa marbuta) are feminine. Understanding the gender of nouns is crucial because it affects other parts of speech like adjectives and verbs.

Definite and Indefinite Nouns

Nouns in Arabic can be definite or indefinite. The definite article “ال” (al-) is added to the beginning of a noun to make it definite. For example:

كتاب (kitab) – a book (indefinite)

الكتاب (al-kitab) – the book (definite)

Arabic Verbs and Conjugation

Arabic verbs are based on a root system, typically consisting of three consonants. Verbs are conjugated to reflect the subject, tense, and mood. For example, the verb “كتب” (kataba) means “to write”:

أنا أكتب (ana aktubu) – I write

هو كتب (huwa kataba) – He wrote

Sentence Structure

Arabic sentence structure can be divided into nominal and verbal sentences.

Nominal sentences start with a noun or pronoun and are typically used for statements.

Example: الكتاب جديد (al-kitab jadid) – The book is new.

Verbal sentences start with a verb and are used to describe actions.

Example: كتب الولد رسالة (kataba al-walad risala) – The boy wrote a letter.

Adjectives and Agreement

Adjectives in Arabic must agree with the nouns they describe in gender, number, and case. For example, a feminine noun requires a feminine adjective:

سيارة جديدة (sayyara jadida) – a new car (feminine)

كتاب جديد (kitab jadid) – a new book (masculine)

Prepositions

Prepositions are used to indicate relationships between words in a sentence. Common prepositions include:

في (fi) – in

على (ala) – on

إلى (ila) – to

من (min) – from

Numbers and Counting

Arabic numbers follow a unique system. Numbers 1-10 have distinct forms, while numbers 11 and beyond follow a specific pattern. It’s essential to practice both cardinal and ordinal numbers for proficiency.

Common Grammatical Challenges

Learners often face challenges such as understanding dual forms, mastering verb conjugations, and distinguishing between similar-sounding letters. Regular practice and exposure to native Arabic can help overcome these hurdles.

Tips for Practicing Arabic Grammar

Consistency is Key: Practice regularly to reinforce new concepts.

Use Multimedia Resources: Leverage books, apps, and online courses.

Language Exchange: Engage with native speakers through language exchange programs.

Immerse Yourself: Watch Arabic movies, listen to Arabic music, and try to read Arabic texts.

Conclusion

Mastering the basics of Arabic grammar is an achievable goal with the right approach and resources. By understanding the fundamental structures and practicing regularly, you’ll build a solid foundation for further language acquisition.

FAQs

How long does it take to master basic Arabic grammar?

The time it takes varies depending on your learning pace and dedication. With consistent practice, you can grasp the basics in a few months.

Is Arabic grammar harder than other languages?Arabic grammar has its unique challenges, but with structured learning and practice, it can be as manageable as learning any other language.

What are the best resources for learning Arabic grammar?Books, online courses, language learning apps, and language exchange programs are excellent resources. Choose what fits your learning style best.

Can I learn Arabic grammar without a teacher?Yes, self-study is possible with the right resources. However, a teacher can provide valuable feedback and guidance.

5. How important is it to learn the Arabic script for grammar?Learning the script is crucial as it allows you to read, write, and understand the grammar rules more effectively.

About Author: Mr.Mahmoud Reda

Meet Mahmoud Reda, a seasoned Arabic language tutor with a wealth of experience spanning over a decade. Specializing in teaching Arabic and Quran to non-native speakers, Mahmoud has earned a reputation for his exceptional expertise and dedication to his students' success.

Mahmoud's educational journey led him to graduate from the renowned "Arabic Language" College at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Holding the esteemed title of Hafiz and possessing Igaza, Mahmoud's qualifications underscore his deep understanding and mastery of the Arabic language.

Born and raised in Egypt, Mahmoud's cultural background infuses his teaching approach with authenticity and passion. His lifelong love for Arabic makes him a natural educator, effortlessly connecting with learners from diverse backgrounds.

What sets Mahmoud apart is his native proficiency in Egyptian Arabic, ensuring clear and concise language instruction. With over 10 years of teaching experience, Mahmoud customizes lessons to cater to individual learning styles, making the journey to fluency both engaging and effective.

Ready to embark on your Arabic learning journey? Connect with Mahmoud Reda at [email protected] for online Arabic and Quran lessons. Start your exploration of the language today and unlock a world of opportunities with Mahmoud as your trusted guide.

In conclusion, Mahmoud Reda's expertise and passion make him the ideal mentor for anyone seeking to master Arabic. With his guidance, language learning becomes an enriching experience, empowering students to communicate with confidence and fluency. Don't miss the chance to learn from Mahmoud Reda and discover the beauty of the Arabic language.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Parole interrogative

In this post, I will cover the two uses of Italian interrogative words.

DISCLAIMER—My native language is English and the point of this blog is that I document my own learning process with the added bonus of maybe helping someone else start learning Italian as well. I have never been to Italy or any other Italian-speaking country before. I do not claim to be an expert on any of this material. Please feel free to correct me if I make any mistakes! Thank you.

La lezione!

First, it’s important to note that there are two types of questions. There are questions that are expected to be answered with a “yes”, a “no”, or an “I don’t know”, which are considered binary response questions. Then, there are open ended questions, which cannot be answered with a “yes”, “no”, or “I don’t know”.

Binary response questions do not require an interrogative word, which also means that the intonation of a phrase may be necessary to determine whether or not it is a question. Binary response questions are structurally the same as a phrase written the same way, but with different punctuation.

Example: Vai al cinema oggi. (You are going to the cinema today) vs. Vai al cinema oggi? (Are you going to the cinema today?)

Open ended questions do require the use of interrogative words, and intonation isn’t as important because the structure of the question explicitly states that the phrase is a question. Questions usually begin with the interrogative word.

The interrogative words are as follows:

How to ask “what?”

Che cosa?

Che?

Cosa?

Example: Che cosa vuoi mangiare? (What do you want to eat?)

NOTE!: What’s the difference between che, cosa, and che cosa? While che cosa is the literally correct and more formal way of saying “what?”, che and cosa on their own are informal ways of asking the question. Cosa is used more often in Northern Italy, while che is used more often in Southern Italy. From what I read, these three phrases seem to be interchangeable.

NOTE!: Che is also used to indicate “what kind” and is an invariable adjective.

Example: Che musica suoni? (What kind of music do you play?)

How to ask “who?” or “whom?”

Chi?

Example: Chi è Marcello? (Who is Marcello?)

Variation: Con chi? means “with whom?”

How to ask “How?” or “Like what?”

Come?

Example: Come stai? (How are you?)

How to ask “why?”

Perché?

Example: Perché sorridi così? (Why do you smile that way?)

How to ask “where?”

Dove?

Example: Dove abiti? (Where do you live?)

Variation: Di dove? means “from where?”

How to ask “when?”

Quando?

Example: Quando sei a casa? (When are you at home?)

How to ask “how much?” and “how many?”

Quanto?

Example: Quanto tempo hai? (How much time do you have?)

NOTE!: Quanto has to agree in gender and number of the noun it modifies. Quanto is the singular masculine form, while the singular feminine is quanta, the plural masculine is quanti, and the plural feminine is quante.*

Example: Quanta acqua? (How much water?)

Example: Quanti anni ha Pietro? (How old is Pietro?)**

Example: Quante lezioni hai oggi? (How many classes do you have today?)

NOTE!: Quanto is invariable when it is followed by a verb, in which case it is used as an indefinite interrogative expression.

Example: Quanto costa la torta? (How much is the cake?)

Another way to ask the same thing: Quant’è la torta?

How to ask “which one?”

Quale?

Example: Quale libro? (Which book?)

NOTE!: Quale has to agree with the number of the noun in question. When the noun is plural, the -e ending changes to an -i.

Example: Quali appunti? (Which notes?)

NOTE!: While in English, we often use “what?” and “which?” interchangeably in certain contexts, Italian does not. In English, I might say, “What’s your favourite book?” but in Italian, I would say, “Qual é tuo libro preferito?”, which translates to “Which is your favourite book?”

NOTE!: As demonstrated above, quale drops the -e before è.

NOTE!: Cosa, come, and dove are elided before è.

Cos’è? — What is it/he/she?

Com’è? — How is it/he/she? or What is it/he/she like?

Dov’è? — Where is it/he/she?

As in English, interrogative words are also used in non-question statements.

Some of these interrogative words can be used in non-question statements as well, but their meanings and context can change a little.

Che — That

Example: È vero che vi sposate? (Is it true that you are getting married?)

NOTE!: Che can also be used in exclamations, in which case it means “What…!” or “What a…!”

Example: Che bravo studente! (What a good student!)

Cosa — Thing

Example: Ci sono parecchie cose di cui vorrei discutere con te. (There are a lot of things I would like to discuss with you.)

Chi — Who

Example: Vince chi risponde a più domande correttamente. (Whoever answers the most questions correctly wins.)

Come — How

Example: Hai visto come mi ha guardato? (Did you see how he looked at me?)

Perché — Because

Example: Non sono andato a lavorare perché ero ammalato. (I didn't go to work because I was sick.)

Perché — So that

Example: Apri la finestra perché possa entrare un po' di aria. (Open the window so that some air can come in.)

Perché as a noun means why, reason, or reason why

Example: Non capisco il perché delle sue azioni. (I don't understand the reason why he does those things.)

Dove — Where

Example: Quello è il bar dove ci siamo incontrati la prima volta. (That bar is where we first met.)

Dove as a noun means the noun “where”.

Example: Il dove e il come dell'operazione non sono ancora noti. (The where and the when still need to be determined.)

Quando — When

Example: Quando piove si ferma tutto il traffico. (When it rains, all traffic stops.)

Quanto — How much

Example: Non riesco neanche a descrivere quanto io ami nuotare in mare. (I can’t even describe how much I love swimming in the sea.)

* Notes

* Quanto follows the same plurals rules as most nouns and adjectives, which I plan on discussing in another post.

** The expressions for stating or asking age literally translate to “having x number of years”. This is the same as in Spanish and French. Again, I plan on discussing this in a future post.

Resources:

HOW TO FORM DIRECT QUESTIONS IN ITALIAN | Learn Italian with Lucrezia (audio ITA)(subtitled)—Learn Italian with Lucrezia on YouTube

I also take notes based on the sixth edition of the Ciao! Textbook by Carla Larese Riga and Chiara Maria Dal Martello.

Word Reference—Italian–English and English–Italian online dictionary

Cosa? Che cosa? Quale? - How to say WHAT in Italian—Italian Pills blog

What is the difference between "cosa...?" and "che cosa...? " ? "cosa...?" vs "che cosa...? " ?—Hi Native

che, cosa or che cosa—Word Reference forum

Cosa vs Che Cosa - Duolingo—Duolingo forum

Is there any difference between "che", "cosa", or "que cosa"?—Dante Learning blog

5 notes

·

View notes