#The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Is a person who is of Jewish descent and was raised Jewish for several years before their parents gave up and raised them irreligious actually Jewish?

The answer to this varies depending on your exact circumstances and where on the spectrum of Judaism the person you're asking falls. As a result, we'd have to say:

That is the sort of question you'd have to ask your rabbi. None of us here have any sort of ordination; we're just a bunch of geeks who like doing research. :) Even if we did have ordination, there are so many differing opinions within the spectrum of Judaism that we'd probably not feel comfortable answering definitively. If you are having trouble finding a rabbi in your area, we suggest you look for your local rabbinical councils or associations, or check national groups’ websites. For example, if you live in the US, there’s the OU (Orthodox Union) https://www.ou.org/synagogue-finder/ , USCJ (United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism) https://uscj.org/network/ , and URJ (Union for Reform Judaism): https://urj.org/urj-congregations . And of course wherever you may live there’s almost certainly a Chabad: https://www.chabad.org/jewish-centers/

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

would you say the same thing about like. the uk masorti movement for example? (not asking this as a gotcha, i'm actually curious)

i would actually maybe place uk masorti in the orthodox bucket! it's my understanding that, while most US conservatives are former reformniks who wanted more observance, most UK masortis are formerly orthodox. there's nothing like the united synagogue in the US, so that changes the dynamics quite a bit

also thanks for asking i love talk abt judaism

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

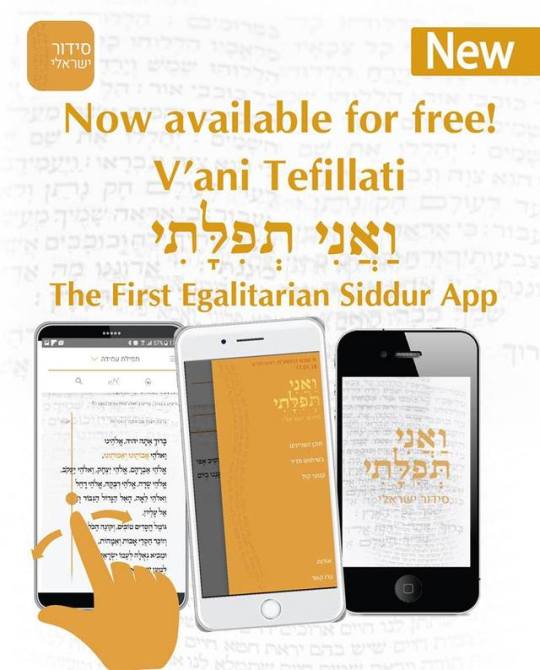

Pray on the go, anywhere in the world. The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism is proud to announce that the Masorti movement has created the first egalitarian siddur app. Available for free, the app opens to the prayer that is relevant for the time of day you open it, specific to your location in the world. Download for IOS at https://apple.co/2nwoxhM or Android at http://bit.ly/2GyfXrV

#siddur#jewish apps#judaism#jewish#jewish prayer#prayer#teffilla#v'ani tefilati#ואני תפלתי#davening#daven#apps#masorti#masorti judaism#masorti movement#hebrew#conservative judaism#The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism#USCJ#TheUnitedSynagogueofConservativeJudaism#conservative#conservativejudaism#progressive judaism#egaltarian#egalitarian judaism#liberal judaism#prayers#jewish prayers#omg#wow

586 notes

·

View notes

Note

Intermarriage with non-Jews in general and patrilineal descent in particular are divisive issues in many Jewish spaces. Several passages in the Torah reflect a long-standing anxiety over the possibility that intermarriage could lead to total assimilation into another culture. That anxiety continues into the modern era for many Jewish communities, and can unfortunately become a barrier for interfaith families that do want to participate fully in Jewish communities. The Rabbinical Assembly, which is the rabbinical association of the Conservative Movement in the United States, still doesn't allow its members to perform interfaith marriage ceremonies. The Reform movement will generally solemnize interfaith marriages, but until last year didn't allow Jews in an interfaith relationship to attend its rabbinical school, and couples may be asked to sign a promise to raise any prospective children Jewish before their Reform rabbi will agree to officiate, depending on the synagogue. So there are definitely obstacles to inclusion. Orthodox communities will in general be even more opposed to intermarriage but the stigma is still far from absent in other communities. This is all to say that even children of a Jewish mother and non-Jewish father won't necessarily have an easy time of things.

Regardless of community acceptance though, a child is considered halakhically Jewish at birth so long as the womb they're gestated in belongs to somebody Jewish (the fact that it's the womb and not the female biological parent is important for IVF with egg donation, surrogacy, and other potential edge cases). The shift from patrilineal descent to matrilineal descent occurred at some point between the composition of the Torah and the talmudic period, and Jewish communities that don't accept the rabbinic tradition, such as Karaite Jews, still rely on patrilineal descent instead. In the modern period, Reconstructionist Judaism was the first to buck matrilineal consensus, accepting any child of at least one Jewish parent as a Jew, provided that they're raised Jewish, starting in 1968. American Reform Judaism followed in 1983. This leads to some intracommunal tensions for those considered fully Jewish by one movement but not by another-- I know lifelong practicing patrilineal Jews from movements that accept patrilineal descent as equally valid who have been asked to undergo a conversion process to participate in certain pluralistic Jewish learning programs administered by organizations that follow the tradition that matrilineal descent is required for automatic inheritance of full Jewish identity. Some will simply accept this as another hoop to jump through while some refuse on the grounds that their Jewish identity should be fully accepted based on the standards of their own movement, rather than requiring participants to meet the standards of the sponsoring movement.

So the short answer to your question is that it depends on the movement and community, but that the general dynamic you frame in your question, that matrilineality is accepted across the board but that children of a Jewish father and a non-Jewish spouse may be expected to undergo conversion to be fully recognized is basically true as a matter of universal acceptance as Jewish. If you'd like to learn more specifically about the experiences of Jews in interfaith families and how we navigate Jewish identity and Jewish community, I highly recommend checking out 18Doors.

I have some questions about Judaism and, since I don't trust Google or Wikipedia, I prefer to ask these questions to people that are actually Jewish. Like, to recognize someone as fully Jewish, does it really require them to have been born to a Jewish mother? What if a person is born to a non-Jewish mother and a Jewish father? The person would be just Jewish in the ethnic sense? The person would need to former convert to Judaism to be a Jewish in the fullest sense?

Please remember to state your FOR. It would be appreciated if you limited yourself to your own FOR and not speak over/for others. We have thank G-d a very nice mix of people answering questions on this blog from all walks of life.

Anon: for further reading, try websites like www.myjewishlearning.com.

#jumblr#ask jumblr#judaism#who is a jew#patrilineal and proud#interfaith families#interfaith marriage#jewish exogamy

15 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Essential Judaism: Covering the Head

In ancient Near Eastern cultures it was considered a sign of respect to keep one’s head covered. With its roots in that part of the world, Judaism adhered to that custom. In Mesopotamia, for example, men of high caste wore some sort of head covering in public at all times; in the period of the First Temple until its destruction in 586 BCE, priests and other officials of the Temple wore turbans or mitres, probably in imitation of the local custom.

In the Talmud, there were a variety of opinions expressed but, finally, the day was carried by those who believed it impertinent to allow the Shekinah, the female manifestation of God, to see their bare heads below Her.

The debate over men’s head covering would continue for several more centuries, but in the Middle Ages the choice was gradually taken away from the Jews. In much of Europe, Christian authorities demanded that Jews wear special hats or hoods that, along with yellow badges that prefigure the Nazi-imposed star of the Holocaust period, identified them as non-Christian.

Since that time, customs regarding head covering have evolved to reflect the history of various Jewish communities. Hence, some Hasidic Jews of Eastern Europe (and their successors in the United States, Western Europe, and Israel) favored the fur-covered round hat called a shtreimel. Today, many American Orthodox Jewish men wear black fedoras. The Jews of Central Asia wore turbans, but now are most identified with the brightly colored cylindrical Bukharan skullcaps.

The most familiar manifestation of the custom of covering the head, however, is the flat, round skullcap known in Hebrew as a kippah (plural kippot) or in Yiddish as a yarmulkah, the head covering of choice for the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews. Even here, the minhag has evolved in different directions: Orthodox men will wear a kippah throughout their waking hours; Conservative and Reconstructionist Jews may do the same, but are equally likely to wear it only in the synagogue, at meals, or while studying sacred texts; some Reform synagogues actually went so far as to proscribe the wearing of headgear on their premises, but in recent years many Reform congregation have begun offering kippot to worshipers (both men and women), and students at Hebrew Union College, the Reform rabbinical seminary, usually are seen wearing kippot.

Throughout the debate on men’s head covering, all the sages were in agreement on one thing: married women must cover their hair. Even in Biblical times, it was considered a brazen violation of the rules of modesty for a married woman to allow anyone but her husband to see her hair. For the Orthodox, this regulation remains in place. Contemporary women’s head coverings run the gamut from scarves and snoods to fashionable hats. Hasidic women will, even today, have their heads shaved just prior to the wedding ceremony and will wear a scarf to cover their heads. One other option available to Orthodox women is the sheitel, a wig. In all Orthodox, many Conservative, and even some Reform synagogues, women are asked to cover their heads during worship and “chapel caps,” small, flat lace equivalents of the kippah, are provided for that purpose.

Source: Essential Judaism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs, and Rituals, 1st ed. by George Robinson, pgs. 28-9.

#religion#judaism#orthodoxy#conservative judaism#reform judaism#jewish#kippah#yarmulke#sheitel#veiling#essential judaism#divinum-pacis

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello Followers!

I know this isn’t dinosaur or Halloween related, but I have a request:

#ShowUpForShabbat

This weekend, Jewish people around the country will be returning to their synagogues after a major tragedy. Shabbat is a day of joy and peace, and on it, the largest massacre of Jewish people on United States soil occurred, so returning to Shabbat after this massacre is an act of real courage.

Allies are appreciated.

Allies will help us not only feel supported in being Jewish, but also protected and helped. It shows you not only support us, but are willing to risk yourselves to help us.

I know it’s a bit overwhelming, especially if you have negative associations with religion. But, I promise, Judaism is... very different from Christianity (I can’t speak to Islam or other faith traditions). So:

Services are Friday night, Saturday morning, or Saturday afternoon. You can just go to one or multiple. I recommend one of the first two.

These services function very differently than ones you’ve probably been to, and they’ll differ based on movement (Reform is very different from Modern Orthodox which is very different from Conservative, etc.) If you’re confused or have questions, don’t hesitate to ask.

“Jews for Jesus” and “Messianic Judaism” aren’t... actually Jewish. I don’t want to get into the politics and the problems with these movements in this post, so just message me if you’re confused. Regardless, don’t go to these “synagogues”.

Please let the synagogue know you’re coming beforehand! Don’t worry, the people running them are very friendly and will be happy to have you come. Just say you’re coming in solidarity so they know to expect you. You can do this via email if you’re nervous about calling!

Please don’t use this as an opportunity to try and convert Jewish people to your religion or to non-religiousity... it’s in bad taste, if nothing else. Same for bringing up contentious topics that are related to Judaism... they aren’t why we’re being attacked. They do not mean we don’t deserve to exist.

I promise, you’ll have an engaging time. Having so many people in service... it’ll help us all out so much. It’ll help us feel so much more supported and safe.

Please consider showing up for Shabbat! I promise, you won’t regret it.

Happy Dinoween,

Meig

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

jews, donate! it’s almost time*

aka the charitable giving masterpost

it’s nearly the high holy days, and a big part of all jewish holidays is tzedakah, or charitable donations in the pursuit of justice. because we should make donations for each holiday, I like to try and make mine relevant to the holiday. this helps me connect to the holiday and its meaning, and to consider more deeply what forms of justice I want to pursue through my celebration of the holiday. here’s my best list of themed charities for every** jewish holiday. i've tried to do a mix of charities based in the uk, the us, and israel.

Rosh Hashanah

rosh hashanah is the beginning of the new year. we reflect on the past year and hope for a sweet new year. it’s a holiday about fresh starts and clean slates.

you could donate to charities that help ex-offenders rebuild their lives, or charities that offer a way out of homelessness, or charities which help people to recover from addition.

adrc, refugee action, the refugee council, and the international rescue committee are all charities which offer support to refugees and asylum seekers as they navigate new countries and new lives. safe passage works to reunite child refugees with their families.

Yom Kippur

yom kippur is, for me, an intensely personal holiday. it’s a time for reflection and introspection. i almost don’t want to recommend any charities for this one. if you have a cause that is significant to you, this is your ideal donation time.

however, if you’re struggling: tzedakah is above all about righting injustice. because it’s a fast day, yom kippur draws our attention to one aspect of injustice in particular: what feels like to be hungry. there are literally hundreds of charities out there working to end food poverty.

alternatively, fast days are a really difficult time to be a person suffering from an eating disorder. donating to an eating disorders charity such as beat or neda is a way to show solidarity with sufferers.

Sukkot

the major theme of sukkot is shelter; we build a sukkah and live/spend time/visit it occasionally (depending on what latitude we live at). i think a lot about our right to safety and security at sukkot.

shelter offers advice, support and legal aid to people experiencing bad housing and homelessness, as well as campaigning to end homelessness. end homelessness is a national alliance committed to ending homelessness in the US.

women’s aid and safe horizon support women escaping domestic violence.

heart to heart, msf, and the red cross all provide emergency aid and disaster relief where they are needed most around the world. world jewish relief is the international humanitarian agency of the british jewish community.

Chanukah

chanukah is a holiday about resistance to assimilation. if you have a local cultural centre, or your synagogue needs funds for cultural events, this is a good time to donate. on a wider scale, the american sephardi foundation and the leo baeck institute preserve the history of sephardi and ashkenazi jews respectively.

we know how important it is as a minority community to have access to our cultural heritage. beit ha’gefen is an arab-jewish cultural centre in haifa, which develops intercultural ties, as well as enriching arab cultural activity in israel. the aca promotes palestinian cultural heritage.

Tu B’Shevat

i love trees, so obviously this is my perfect holiday. if you, like me, want to protect trees, then bgci is an international network of botanic gardens working to conserve the world’s plants.

there are many international wildlife conservation organisations, such as conservation international, but you could also look more locally, at your local wildlife trust, or your local climate action group.

if you want to combine environmentalism with social justice, the environmental justice foundation (see what i did there?) highlights the links between human rights and environmental protection.

Purim

at first glance, purim is a tricky festival to define, perhaps because it lacks a presence of god. but this makes it interesting: it’s about intolerance, and the power that we have to fight injustice (and despots with genocidal tendencies), even when god is apparently absent.

stonewall is an LGBT+ rights organisation, which campaigns for equality for LGBT+ people. black lives matter and the splc both act to combat racism across the US.

hand in hand are building a network of jewish-arab public schools across israel to promote tolerance and co-existence.

Pesach

the big one. the passover story forms our collective psyche: we have all been refugees, and we too were strangers in the land of Egypt. this is a holiday with big themes of liberation, freedom from oppression and the power of storytelling to bind a people.

the aclu works to protect the rights and liberties of everyone in the united states, while raices provides legal services to immigrants and refugees. both organisations are currently fighting Trump’s family separation policies.

the truth is that slavery never ended, and there are many charities working to end human trafficking and modern slavery. in addition, the legacy of historic slavery is long, and the passover seder teaches us that remembrance is essential. the NMAAHC gives a voice to African American history and culture.

Shavuot

a big theme of this holiday is learning. we stay up all night in torah study (at least, we do if we’re keen). in fact, judaism as a whole is very keen on learning. use this as an opportunity to help give others an education.

magic breakfast gives breakfast to kids who otherwise might not get to eat before school, so they can learn to their full potential (here’s a us-based program).

girl rising campaigns to change attitudes towards educating girls and women, while global education fund empowers local organisations improve education in their communities.

learning doesn’t stop with going to school: perhaps you’d like to help refugees learn English or Hebrew, or you believe that learning how to garden, or play sport, or cook has the power to change someone’s life.

please add more suggestions to this very-much-non-exhaustive list and if I have accidentally included any awful suggestions, please educate me!

now let’s donate!

*credit

**okay, obviously not every one, because who knows every jewish holiday anyway?

#jewish#jumblr#rosh hashanah#yom kippur#chanukkah#tzedakah#pesach#purim#passover#social justice#high holidays#jewish holiday#charity#tzedek#tzedek tzedek tirdof

247 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I don’t know much about Jews but I would like to know if Ashkenazi Jews are open to homosexuality?

Ummmm there’s no real way to answer this question, and I’m going to break down why:

1. ‘Ashkenazi’ just refers to Jews who can trace their familial roots to Eastern Europe. It has no bearing on where an individual falls, politically or religiously. There are Haredi (“Ultra” Orthodox) Ashkenazim, secular Ashkenazim, hard-right Ashkenazim, socialist Ashkenazim, Ashkenazim who live in the United States, Israel, Poland, South Africa, Mexico. Ashkenazim who identify as white, black, Middle Eastern, Asian, so on and so forth. It’s an ethnic identity.

2. It makes… a little bit more sense if you were asking about specific Jewish movements, because Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, who trace their familial roots to Spain and the Middle East, respectively, typically don’t break their observance down like that. There may be variations in how they practice Judaism, and there are Sephardim and Mizrahim who attend majority-Ashkenazi synagogues that fall under different labels, but most of the major Jewish movements (Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, Modern Orthodox) really emerged in the United States among Ashkenazim.

(If you’re reading this and thinking “that’s a major oversimplification,” I know, I’m just trying not to resist my instinct to dive into four hundred years of Jewish history at the moment.)

In that case, my answer would be that the Reconstructionist, Reform, and Conservative movements have all released official statements affirming their acceptance of LGBTQ Jews. They ordain LGBTQ rabbis, accept LGBTQ converts, and perform same-sex marriages. The term “Orthodox” encompasses a looooot more ideological variation and is harder to sum up. I think one example of how complex it can get is the life of Steven Greenberg, who became the first openly gay Orthodox rabbi about fifteen years ago. He is gay, has talked publicly about it, has written books about it… and doesn’t believe that same-sex marriage is compatible with Orthodox Judaism. He has performed at least one secular wedding for two Orthodox men, but didn’t perform the Jewish religious marriage rites.

I’m not Orthodox and I’m not going to delve into this topic more, because honestly I think it’s really unfair how often Orthodox LGBTQ people are attacked from both sides of the debate, which brings me to point 3!

3. I’m going to be honest–I’m not answering this question from a place of anger, and I’m only over-explaining because I’m a rambling person. It’s not to bash anon or to show off my own superiority. But… I wonder if people realize that, when they ask “are Jews accepting of homosexuality?” they’re really asking “are straight Jews accepting of homosexuality?”

Because I’ve gotten this question a lot, always from non-Jews and often, in personal life, from straight people. And they’re always surprised when I mentioned that there are LGBTQ organizations for Haredi, Hasidic, and Modern Orthodox Jews, because they haven’t considered that they exist. And they do! LGBTQ Jews exist in every movement and every ethnicity, and even if we aren’t always out to the entire community, we are often out to each other. I think that’s especially important to say when we’re talking about a community that is often demonized as backward and repressive.

And to be clear, I don’t blame LGBTQ people who want to know if they can visit a synagogue or learn about Judaism while feeling safe. That’s understandable! But I would be remiss if I erased the existence of LGBTQ Jews from this conversation. Especially because I’m a Jewish lesbian myself. And our last point:

4. It varies. A lot. Within synagogues, between synagogues, geographically, individually. I used to attend a Conservative synagogue in a town colloquially known as Lesbianville, USA, so yeah, that synagogue was GAY AS SHIT. The rabbi and the members were in favor of same-sex marriage LONG before the movement as a whole was, and the majority of the straight members are queer-competent. A Conservative synagogue located in a smaller or more rural area, or a town that was more politically conservative and homophobic? Probably not as accepting.

It goes both ways. Statistically speaking, Jews tend to be more liberal than the average American, but there are some right-wing Jews who are homophobic regardless of their movement or ethnic background. On the other hand, there are right-wing people who don’t have a problem with gay people. I’ve met individuals who were Modern Orthodox and totally out and happy with it, and individuals who were Reform and had homophobic parents and were closeted. There are a lot of different factors and it can be hard to parse them out.

All in all, I think the best way to determine whether a particular community is homophobic or accepting is to look at: A) organizations like Keshet that promote LGBTQ acceptance in Jewish communities and keep lists of LGBTQ-friendly synagogues, B) resources and statements put out by synagogues/organizations, C) what members themselves have said and whether there are social justice or LGBTQ groups, D) the political background/demographics of the local population in general.

There are also strictly-religious interpretations of this question but this is a very long ask so I’m not going to go into that just yet. Short answer: like all of Jewish law, it’s complicated.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judaism 101: Places of Worship

Terminology, Functions and Organization, and all you need to know about Jewish Places of Worship.

First: The Temple; what do Jews mean when they refer to “the Temple”

When Jewish people speak of The Temple, we speak of the place in Jerusalem that was the center of Jewish worship from the time of Solomon to its destruction by the Romans in 70 C.E.

This was the one and only place where sacrifices and certain other religious rituals were performed. It was partially destroyed at the time of the Babylonian Exile and rebuilt.

The rebuilt temple was known as the Second Temple. The famous "Wailing Wall" (known to Jews as the Western Wall or in Hebrew, the Kotel) is the remains of the western retaining wall of the hill that the Temple was built on. It is as close to the site of the original Sanctuary as Jews can go today. You can see a live picture of the Kotel and learn about it at KotelCam. The Temple was located on a platform above and behind this wall.

Today, the site of The Temple is occupied by the Dome of the Rock (a Muslim shrine for pilgrims) and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The Dome of the Rock is the gold-domed building that figures prominently in most pictures of Jerusalem.

Traditional Jews believe that The Temple will be rebuilt when the Mashiach (Messiah) comes. They eagerly await that day and pray for it continually. In Jewish tradition, Jesus is NOT the messiah. I will talk another day about “Jews for Jesus” and “Messianic Jews” that are Christian sects appropriating Jewish culture and traditions and trying to convert Jews to Christianity.

Modern Jews, on the other hand, reject the idea of rebuilding the Temple and resuming sacrifices. They call their houses of prayer "temples," believing that such houses of worship are the only temples we need, the only temples we will ever have, and are equivalent to the Temple in Jerusalem. This idea is very offensive to some traditional Jews, which is why you should be very careful when using the word Temple to describe a Jewish place of worship.

Terminology

Throughout our posts, I have mainly used the term “synagogue” to refer to the Jewish house of worship. However, there are several other terms used to describe it, and those terms can tell a lot about the religious background of the Jewish person using them.

The Hebrew term is beit k'nesset (literally, House of Assembly), although you will rarely hear this term used in conversation in English.

The Orthodox and Hasidim typically use the word "shul," which is Yiddish. The word is derived from a German word meaning "school," and emphasizes the synagogue's role as a place of study.

Conservative Jews usually use the word "synagogue," which is actually a Greek translation of Beit K'nesset and means "place of assembly" (it's related to the word "synod").

Reform Jews use the word "temple," because they consider every one of their meeting places to be equivalent to, or a replacement for, The Temple in Jerusalem.

I, a Sephardic European Jew, have always used and always heard the word “synagogue” being used, with some rare exceptions.

The use of the word "temple" to describe modern houses of prayer offends some traditional Jews, because it trivializes the importance of The Temple. The word "shul," on the other hand, is unfamiliar to many modern Jews. When in doubt, the word "synagogue" is the best bet, because everyone knows what it means, and I've never known anyone to be offended by it.

Functions of a Synagogue

At a minimum, a synagogue is a beit tefilah, a house of prayer. It is the place where Jews come together for community prayer services. Jews can satisfy the obligations of daily prayer by praying anywhere; however, there are certain prayers that can only be said in the presence of a minyan (a quorum of 10 adult men), and tradition teaches that there is more merit to praying with a group than there is in praying alone. The sanctity of the synagogue for this purpose is second only to The Temple. In fact, in rabbinical literature, the synagogue is sometimes referred to as the "little Temple."

A synagogue is usually also a beit midrash, a house of study.

Contrary to popular belief, Jewish education does not end at the age of bar mitzvah. For the observant Jew, the study of sacred texts is a life-long task. Thus, a synagogue normally has a well-stocked library of sacred Jewish texts for members of the community to study. It is also the place where children receive their basic religious education.

Most synagogues also have a social hall for religious and non-religious activities. The synagogue often functions as a sort of town hall where matters of importance to the community can be discussed. In addition, the synagogue functions as a social welfare agency, collecting and dispensing money and other items for the aid of the poor and needy within the community.

Organizational Structure

Synagogues are, for the most part, independent community organizations.

In the United States, individual synagogues do not answer to any central authority. There are central organizations for the various movements of Judaism, and synagogues are often affiliated with these organizations, but these organizations have no real power over individual synagogues.

Synagogues are generally run by a board of directors composed of lay people. They manage and maintain the synagogue and its activities, and hire a rabbi and chazzan (cantor) for the community.

Yes, you read that right: Jewish clergy are employees of the synagogue, hired and fired by the lay members of the synagogue. Clergy are not provided by any central organization, as they are in some denominations of Christianity.

However, if a synagogue hires a rabbi or chazzan that is not acceptable to the central organization, they may lose membership in that central organization. For example, if an Orthodox synagogue hires a Reform rabbi, the synagogue will lose membership in the Orthodox Union. If a Conservative synagogue wishes to hire a Reconstructionist rabbi, it must first get permission from the USCJ.

The rabbi usually works with a ritual committee made up of lay members of the synagogue to set standards and procedures for the synagogue. Not surprisingly, there can be tension between the rabbi and the membership (his employers) if they do not have the same standards, for example if the membership wants to serve pepperoni pizza (not kosher) at a synagogue event.

It is worth noting that a synagogue can exist without a rabbi or a chazzan: religious services can be, and often are, conducted by lay people in whole or in part. It is not unusual for a synagogue to be without a rabbi, at least temporarily, and many synagogues, particularly smaller ones, have no chazzan. However, the rabbi and chazzan are valuable members of the community, providing leadership, guidance and education.

Synagogues do not pass around collection plates during services, as many churches do. This is largely because Jewish law prohibits carrying money on holidays and Shabbat.

Tzedakah (charitable donation) is routinely collected at weekday morning services, usually through a centrally-located pushke, but this money is usually given to charity, and not used for synagogue expenses. Instead, synagogues are financed through membership dues paid annually, through voluntary donations, through the purchase of reserved seats for services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur(the holidays when the synagogue is most crowded), and through the purchase of various types of memorial plaques.

It is important to note, however, that you do not have to be a member of a synagogue in order to worship there. If you plan to worship at a synagogue regularly and you have the financial means, you should certainly pay your dues to cover your fair share of the synagogue's costs, but no synagogue checks membership cards at the door (except possibly on the High Holidays mentioned above, if there aren't enough seats for everyone).

Ritual items at the Synagogue

The portion of the synagogue where prayer services are performed is commonly called the sanctuary. Synagogues in the United States are generally designed so that the front of the sanctuary is on the side towards Jerusalem, which is the direction that we are supposed to face when reciting certain prayers.

Probably the most important feature of the sanctuary is the Ark, a cabinet or recession in the wall that holds the Torah scrolls. The Ark is also called the Aron Kodesh ("holy cabinet"), and I was once told that the term "ark" is an acrostic of "aron kodesh," although someone else told me that "ark" is just an old word for a chest. In any case, the word has no relation to Noah's Ark, which is the word "teyvat" in Hebrew.

The Ark is generally placed in the front of the room; that is, on the side towards Jerusalem. The Ark has doors as well as an inner curtain called a parokhet. This curtain is in imitation of the curtain in the Sanctuary in The Temple, and is named for it.

During certain prayers, the doors and/or curtain of the Ark may be opened or closed. Opening or closing the doors or curtain is performed by a member of the congregation, and is considered an honor. All congregants stand when the Ark is open.

In front of and slightly above the Ark, you will find the ner tamid, the Eternal Lamp. This lamp symbolizes the commandment to keep a light burning in the Tabernacle outside of the curtain surrounding the Ark of the Covenant. (Ex. 27:20-21).

In addition to the ner tamid, you may find a menorah (candelabrum) in many synagogues, symbolizing the menorah in the Temple. The menorah in the synagogue will generally have six or eight branches instead of the Temple menorah's seven, because exact duplication of the Temple's ritual items is improper.

In the center of the room or in the front you will find a pedestal called the bimah. The Torah scrolls are placed on the bimah when they are read. The bimah is also sometimes used as a podium for leading services. There is an additional, lower lectern in some synagogues called an amud.

In Orthodox synagogues, you will also find a separate section where the women sit. This may be on an upper floor balcony, or in the back of the room, or on the side of the room, separated from the men's section by a wall or curtain called a mechitzah. Men are not permitted to pray in the presence of women, because they are supposed to have their minds on their prayers, not on pretty girls.

That separation is also present in Sephardic synagogues, at least the ones I am aware of. The synagogue I attended at my grandparents’ as a child had women and children on a balcony.

I will discuss the Role of Women in Judaism in another post coming up later.

Non-Jews Visiting a Synagogue

Non-Jews are always welcome to attend services in a synagogue, so long as they behave as proper guests.

Proselytizing and "witnessing" to the congregation are not proper guest behavior. Would you walk into a stranger's house and criticize the decor? But we always welcome non-Jews who come to synagogue out of genuine curiosity, interest in the service or simply to join a friend in celebration of a Jewish event.

When going to a synagogue, you should dress as you would for church: nicely, formally, and modestly. A man should wear a yarmulke/kippah (skullcap) if Jewish men in the congregation do so; those are available at the entrance for those who do not have one.

In some synagogues, married women should also wear a head covering. A piece of lace sometimes called a "chapel hat" is generally provided for this purpose in synagogues where this is required.

Non-Jews should not, however, wear a tallit (prayer shawl) or tefillin, because these items are signs of our obligation to observe Jewish law.

Be careful to know what kind of synagogue you’re attending, and follow the sitting arrangements there. If women and men are separated, you should follow the rule of the congregation.

During services, non-Jews can follow along with the English, which is normally printed side-by-side with the Hebrew in the prayerbook. You may join in with as much or as little of the prayer service as you feel comfortable participating in. You may wish to review Jewish Liturgy before attending the service, to gain a better understanding of what is going on.

Non-Jews should stand whenever the Ark is open and when the Torah is carried to or from the Ark, as a sign of respect for the Torah and for G-d. At any other time where worshippers stand, non-Jews may stand or sit.

For trans people attending a synagogue:

I would recommend checking with your friend (if you’re attending with a friend), or the synagogue itself if you will be able to sit with your gender. It would avoid for you to be on the receiving end of transphobic ideas and experience some difficult times, and maybe dysphoria.

I cannot promise you that all synagogues will be open to trans people sitting with people of the same gender as they identify as.

Modern Judaism tends to accept trans people and allow them to wear kippot if they identify as men. It does also sometimes allow women to wear traditionally “male” garments like kippot, tefillin or tallit.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rabbi

Congregation Neve Shalom in Metuchen, New Jersey, the premier egalitarian Conservative Synagogue in Northern Middlesex County, is searching for our next Spiritual Leader. We are affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ), have an active USY, Men’s Club, Sisterhood, a small but mighty religious school, and an award-winning Adult Education program. We are known as a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Check out the awesome work that USY is doing ! Kol hakavod!

#black lives matter#tikkun olam#justice#tzedek#usy#united synagogue youth#conservative judaism#conservative#conservative jews#youth group#jewish youth group#tzedakah

38 notes

·

View notes

Link

If you go into a Reform or Conservative temple, it’s likely that you will notice two things: The congregation is becoming smaller and older. Across the United States and Europe, Jewish congregations are aging at a rapid rate, a phenomenon increasingly common for mainstream religions across the high-income world.

Overall, the American Jewish population—unlike that of demographically robust Israel—is on the decline, with a loss of 300,000 members over the past decade, a number expected to drop further by 2050. The median age of members of Reform congregations is 54, and only 17 percent of members say they attend religious services even once a month. Four-fifths of the movement’s youth are gone by the time they graduate high school. The conservative movement is, if anything, in even worse shape: At its height, in 1965, the Conservative movement had 800 affiliated synagogues throughout the United States and Canada; by 2015 that number had fallen to 594.

But Jews, and their religious institutions, should not feel singled out. The share of Americans who belong to the Catholic Church has declined from 24 percent in 2007 to 21 percent in 2014, a more rapid decline according to Pew, then any other religious organization in memory. There are 6.5 former Catholics in the U.S. for every new convert to the faith, not a number suggesting a very sunny future.

…

Why, then, the decline in religion? For one thing, young Americans have different habits. Rather than join institutions, millennials, argued Wade Clark Roof, author of the book Spiritual Marketplace, are indulging in a kind of “grazing,” finding their spiritual fixes in various different places rather than any one organized church. As sociologists Robert Putnam and David Campbell explained, those in this age group “reject conventional religious affiliation, while not entirely giving up their religious feelings.”

But the consumption habits of the young aren’t the only reason for America’s religious drought. Religious institutions and ideas are currently under political attack, predominantly from the left, with some progressives, such as California’s Dianne Feinstein or New Jersey’s Cory Booker, appearing to see embrace of Christian dogma, or even membership in such anodyne organizations as the Knights of Columbus, as cause for exclusion from high judicial office.

This trend is reinforced by the media , which is often dismissive of traditional faith. There has been a powerful tendency to demonize and suggest the worst of motives among the faithful, which was evident in the rush to judgment about the alleged racism of the Covington, Kentucky, religious students. Before the facts proved claims of racism to be false, newspaper accounts and tweets from journalists endorsed actions against the students, sometime including violence, in ways more reminiscent of Joseph Goebbels than Joseph Pulitzer.

As in many cases, this bias reflects the groupthink nurtured at our leading universities. Evangelicals and religious conservatives barely exist in the country’s leading theological seminaries, where they are outnumbered, by some estimates, 70 to 1 by liberals, and evidence suggests that those espousing traditional religious views are widely discriminated against in academic departments.

…

Yet rebranding themselves as progressive often brings religious activists into alliances with people who reject their core values. The Catholic left, for example, allying itself with the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, implicitly embraces the advocates of the most extreme abortion liberalization. Sometimes, these linkages are ironic: Faith in Public Life, for example, a strident “religious” group advocating a progressive anti-Trump line, gets much of its funding from George Soros, arguably the world’s most well-heeled and active promoter of atheism.

For their part, progressive Jews, embracing the notion of tikkun olam, face a similar dilemma. In their rush to oppose President Trump, with his occasional despicable winks at alt-right groups, many Jewish activists have collaborated with the organizers of the Women’s March, including enthusiastic backers of the most influential anti-Semite of our time, Nation of Islam head Louis Farrakhan.

…

Is there a way back from this sorry state of affairs?

However satisfying to its practitioners, the emphasis on social justice is clearly not attracting more worshippers. Almost all the religious institutions most committed to this course are also in the most serious decline, most notably mainstream Protestants but also, Catholics and Reform and Conservative Jews. The rapidly declining Church of England, which is down to 2 percent share among British youth, is burnishing its progressive image by adding the use of plastics to its list of Lenten sacrifices, but seems unable to serve the basic spiritual and family needs of their congregants.

In contrast, more conservative faith organizations generally enjoy better growth, and higher birthrates, particularly in the developing world . The University of London’s Eric Kaufmann explains in his important book Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? that if current trends continue, the more fundamentalist family-centered faiths seem most likely to survive. Already, for example, Orthodox Jews, historically a small subgroup, are projected to become the majority of the Hebraic community in Britain by 2100, and already constitute some three-fifths of Jewish children in New York.

Orthodox Jews and evangelicals may be finding common ground, then, but the future of religion overall does not seem a bright one. It’s hard to imagine most young Jews becoming Orthodox, or casual Christians embracing en masse Mormonism or evangelical Christianity. Instead, the future seems to point to a smaller, more conservative religious community, isolated amidst an increasingly secularized culture.

…

Ultimately, as Lemus suggested, religions, including Judaism, can only hope to thrive if they serve a purpose that is not met elsewhere in society. It is all well and good to perform good deeds, but if religions do not make themselves indispensable to families, their future could be bleak. As we already see in Europe, churches and synagogues could become ever more like pagan temples, vestiges of the past and attractions for the curious, profoundly clueless about the passion and commitment that created them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pittsburgh Killing Aftermath Bares Jewish Rifts in Israel and America

By David M. Halbfinger, NY Times, Oct. 29, 2018

BEIT SHEMESH, Israel--The slaughter of 11 Jews in Pittsburgh elicited responses in Israel that echoed the reactions to anti-Semitic killings in Paris, Toulouse and Brussels: expressions of sympathy, reminders that hatred of Jews is as rampant as ever, reaffirmations of the need for a strong Israel.

But Saturday’s massacre also brought to the surface painful political and theological disagreements tearing at the fabric of Israeli society and driving a wedge between Israelis and American Jews.

Israel’s Ashkenazi chief rabbi took pains to avoid the word “synagogue” to describe the scene of the crime--because it is not Orthodox, but Conservative, one of the liberal branches of Judaism that, despite their numerous adherents in the United States, are rejected by the religious authorities who determine the Jewish state’s definitions of Jewishness.

And the attacker’s anti-refugee, anti-Muslim fulminations on social media prompted some on the Israeli left--like many American Jewish liberals--to draw angry comparisons to views espoused by the increasingly nationalistic leaders who now hold sway in their governments.

The result has been a striking and lightning-fast politicization of the sort of tragedy that until now had only galvanized Jews across the world--not set them at one another’s throats.

Here in Israel, the decades-old animosity between left and right has reached new levels of enmity in recent years. Ultra-Orthodox parties that play a kingmaker’s role in the right-wing government are pressing to increase their influence and that of Jewish law on daily life, sparking bitter fights over everything from who serves in the military to whether trains can run and stores can open on the Sabbath. Jews from liberal American denominations feel increasingly alienated from Israel’s state-run religious life.

With the Israeli government, like many across Europe, also taking a decidedly nationalistic turn, the election of President Trump has only compounded that strife, widening the rift between Israeli and American Jews. Politically liberal American Jews have been repelled by Mr. Trump’s solid support for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and by Mr. Netanyahu’s effusive embrace of Mr. Trump and his granting of a wish-list’s worth of political gifts. They range from scrapping the Iran nuclear agreement to repeatedly punishing the Palestinians and recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

All of that, and more, bubbled up when one of Israel’s most influential politicians, Naftali Bennett, leader of the right-wing Jewish Home party, jumped on a plane to Pittsburgh in his capacity as minister of diaspora affairs. Mr. Bennett gave voice only to unifying ideals: “Together we stand, Americans, Israelis--people who are, together, saying no to hatred,” he told a vigil there Sunday night. “The murderer’s bullet does not stop to ask, ‘Are you Conservative or Reform, are you Orthodox? Are you right-wing or left-wing?’ It has one goal, and that is to kill innocent people. Innocent Jews.”

No sooner had Mr. Bennett’s plane departed Ben-Gurion Airport than he was assailed by liberal Israeli critics, who among other things resurfaced a 2012 Facebook post in which he had accused leftists of promoting “crime and rape in Tel Aviv” because they wanted to allow African migrants who had entered the country illegally to stay.

“Is the Trump-supporting, African-migrant-bashing Naftali Bennett really the best person to represent Israel in Pittsburgh right now?” wrote Anshel Pfeffer in Haaretz, the liberal daily.

Others cited a pro-Jewish Home party text message sent to Haifa residents in advance of Tuesday’s municipal elections. It warned Jewish voters fearful of “the flight of young Jews” and a “takeover” by “the sector”--shorthand for Israeli Arabs--to vote for the Jewish Home slate.

“That’s almost word-for-word the spirit of ‘Jews will not replace us,’” said Dahlia Scheindlin, a left-wing political consultant in Tel Aviv, recalling the chant of neo-Nazi marchers in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017.

Even Michael Oren, the American-born deputy minister from the right-of-center Kulanu party, faulted Mr. Bennett for having sided with the ultra-Orthodox Israeli rabbinate, which refuses to recognize non-Orthodox denominations as sufficiently Jewish to participate fully in Israeli religious life.

“Liberal Jews were Jewish enough to be murdered, but their stream is not Jewish enough to be recognized by the Jewish State,” Mr. Oren wrote in Hebrew on Twitter, adding: “I call on Minister Bennett not to suffice with condolences, but to recognize liberal Jewish streams and unite the people.”

On the right, veteran activists in Likud, Mr. Netanyahu’s party, circulated an email on Sunday--which Mr. Netanyahu’s aides and party leaders disavowed within hours--noting that the Pittsburgh killer had denounced the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, which “encouraged immigration” and “acted against Trump.”

“Did we or did we not say that the Left is guilty of encouraging anti-Semitism?,” wrote the email’s author, who responded to queries but declined to identify himself.

Many Israelis, of course, reacted with horror and grief as they tuned into coverage of the Pittsburgh massacre. In Beit Shemesh, a largely ultra-Orthodox city 20 minutes west of Jerusalem, Elisheva Gutman, 24, a social worker, said her parents had vacationed in Pittsburgh two weeks earlier and had attended Sabbath services down the street from the Tree of Life synagogue, the killing site. “When they go to Europe, my father takes off his kipa and puts on a hat,” for fear of attack, Ms. Gutman said. “It’s not supposed to be that way in the U.S.”

Chaim Zaid, 62, a paramedic from Kedumim, a West Bank settlement, said the shooting belied Israelis’ ideas of the United States as a “paradise” for Jews. “You think the big U.S., with the big F.B.I., will protect them, and nothing will change,” he said. “But that was a change point. My sister lives in Brooklyn and was afraid to come to my home. So Sunday morning I sent her a message: ‘Rivka, you were afraid to come to me?’”

If other Israelis were quick to score political points over the Pittsburgh killings, though, in a sense they had been preparing for this moment. The disagreements between American and Israeli Jews have been piling up.

Only last week, the Jewish Federations of North America’s yearly General Assembly drew hundreds of Americans to Tel Aviv for a three-day conference focused on the strains in the relationship, titled “We Need to Talk.”

In a provocative keynote, the head of Israel’s largest real estate company, Danna Azrieli, recited the litany of friction points. For Americans, she said, there are Mr. Netanyahu’s effusive embrace of Mr. Trump, whom most American Jews oppose; the Israeli occupation and Jewish settlements on the West Bank, which many American Jews believe block peace with the Palestinians; Mr. Netanyahu’s reneging on a deal last year to significantly upgrade and grant equal status to a mixed-gender, Reform and Conservative prayer space at the Western Wall; and Israel’s new nation-state law, which opponents call racist and anti-democratic because it enshrines the right of national self-determination in Israel as “unique to the Jewish people.”

Long as it was, that list had big omissions. Israelis on the left would add, at a minimum, the Netanyahu government’s warming up to increasingly authoritarian leaders in countries like Hungary and Poland, and its demonization of the Hungarian-born, liberal Jewish financier George Soros--who also is a frequent target of anti-Semitic attacks in the United States and Europe--for underwriting activist groups that oppose Mr. Netanyahu’s policies. Mr. Netanyahu’s own son even posted a meme attacking Mr. Soros with anti-Semitic imagery that drew praise from the likes of David Duke.

And Israelis on the right would add their lingering resentment of American Jews’ support for the Iran nuclear deal struck by President Obama, which Israelis saw as a matter of survival, according to the author Yossi Klein Halevi, a New York-born Jerusalemite.

Mr. Halevi, a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute, said the Pittsburgh shootings had exposed an even deeper and more worrisome divide between the two populations. “Each sees the other as in some sense threatening its most basic well-being,” he said. “American Jews don’t understand the depth of the Israeli sense of betrayal over the Iran deal. And Israelis don’t understand why American Jews regard Trump as a life-and-death threat to the liberal society that allowed American Jewry to become the most successful minority in Jewish history.”

How damaged is the relationship? In her keynote, Ms. Azrieli felt compelled to plead, “Don’t give up on our country,” adding: “Don’t walk away because your liberal sensibilities are insulted. Don’t assume that nothing can change. Things do change--just painfully, slowly, incrementally, and with all of our help.”

And yet among Israeli leaders, some already have given up on American Jews, said Mr. Oren, the deputy minister and a former Israeli ambassador in Washington, who also cited some American Jews’ opposition to President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital.

“One school of thought is: ‘These are our people, we have to do everything possible to reach out.’ The second school says:, ‘It’s too late, they’re gone. After Iran, after Jerusalem, if we have limited resources we should invest in our base--evangelicals and the Orthodox.’”

In Beit Shemesh, Zion Cohen, 66, a mall manager, lamented the acrimony. “I’m Likud, but what’s happened between Israel and America, I’m against it,” he said. “I know it’s painful to Jews in America how Israel acts toward them. The influence of the Orthodox and Haredim on the Israeli government is a catastrophe. And we need help from the Jews of the U.S., especially given how much anti-Semitism there is now in the world.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Congregation of One

It was not God, my synagogue or anyone else that was culpable for my downfall, and no one besides myself could be responsible for mending my soul. It was up to only me.

I am a Jewish person who was born and raised in a Conservative congregation. Even though Judaism is considered to be a communal religion, I now reside in a community of one. How can that be? I am a prisoner in a United States Federal Prison and currently have the distinction of [being a congregation of one]. By Jeffrey Abramowitz, Executive Director of Reentry Services at JEVS Human Services I…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

[some highlights. click so they can get ad revenue, if you’re interested. I’m goyim & this seems hopeful. ♣Peace♥ you are valid. – Eve]

Meet the first openly transgender teen elected to the board of USY

By Josefin Dolsten February 6, 2018 12:04pm

> (JTA) — Sawyer Goldsmith said he has always felt accepted as a a member of the LGBTQ community in United Synagogue Youth, the Conservative movement’s youth group. But the 16-year-old from suburban Chicago hopes his recent election to serve as religion/education vice president on the group’s international board, the first time an openly transgender person has been voted to the board, will show others who may not be as comfortable that they belong.

“I want the other trans USYers to know you’re seen,” Goldsmith told JTA in a phone interview last week. “I can be this key person for them, that they don’t have to hide in the background, they can come out if they feel comfortable, they can be themselves.” >

…

> “USY was always a place for me to be myself, but I know in other Jewish situations that I didn’t feel like I could be myself and I was scared,” he said.

At his home synagogue, North Suburban Synagogue Beth El, his parents are working on a committee of parents of LGBTQ children to ensure that the community is welcoming.

As religion/education vice president, one of Goldsmith’s goals is to make sure transgender USY members get appropriate accommodations during retreats. Goldsmith recalled an experience in which he was told he could not share a room with other male members on the program.

“I wasn’t allowed to room with the guys even though I identified as one, so I fought for my rights, and now I’m able to room with guys,” he said. But I want there to be a system where if someone identifies as trans, they are able to room with the gender that they identify with.

Rabbi Steven Wernick, CEO of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, praised Goldsmith’s election.

“We are proud of Sawyer, just like we’re proud of all our teen leaders and we strive to create a welcoming culture for all participants, regardless of their identity,” Wernick told JTA in a statement.

The Conservative movement, like the other non-Orthodox denominations, has embraced the LGBTQ community. In 2016, the international association of Conservative rabbis passed a resolutionexpressing its support for and acceptance of transgender people. The Rabbinical Assembly resolution declared support for “the full welcome, acceptance, and inclusion of people of all gender identities in Jewish life and general society.” It cited Jewish legal literature, going back to the second century C.E. Mishnah, which “affirms the variety of non-binary gender expression throughout history, granting transgender people the obligations and privileges of all Jews.” >

6 notes

·

View notes