#The Restoration

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I’ve been thinking about this for awhile and wanted to ask

Opinions on Dark Sonic? Even if that form isn’t canon what are your thoughts?

How do you think an interaction between surge & the restoration would go if someone somehow pushed Sonic to his limit and that form came out?

Super-powered evil sides is a fascinating but difficult trope to handle. Sonic having one is interesting but it could be argued that Metal Sonic, Shadow, and Surge already fill that role well enough already.

I feel like everyone, not just the Restoration and Surge, would treat Dark Sonic the same way real world governments would treat a terrorist cell having a dozen nukes.

A combination of trepidation, terror, and everything and the kitchen sink. It would truly be all hands on deck.

#sonic the hedgehog#metal sonic#shadow the hedgehog#surge the tenrec#dark sonic#the restoration#sth#idw sonic#sonic#sonic idw#overly sarcastic productions

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Jewel, what is restoration hq equipped with? Does it have businesses inside it like a Pizza Shack?

Jewel made an X with her arms, "As long as I am Director there will never be a single corporation within the Restoration." Lowering her arms she suddenly looked embarrassed, "Oh goodness I'm so sorry I thought the question said 'Radio Shack.' I need to get more sleep." Clearing her throat she continued, "Any vendors we have in HQ are local small businesses. That does include a pizza place."

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Star Wars: Shattered Empire #3 by Angel Unzueta

#Star Wars#Star Wars: Shattered Empire#Marvel#Comic#Comics#Galactic Empire#Imperial#Imperial II Class#Star Destroyer#The Torment#The Restoration#Rebel Alliance#Mon Calamari Cruiser#MC80 Class#Sci-Fi#Mecha#Spaceship#Angel Unzueta

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made what I think is my first real Sonic OC, I'm not sure though.

Mido is a Holland lop Bunny from an alternate universe where the restoration wasn't able to cure the metal virus, but also didn't fall.

There is many changes in this universe on how the virus works, the the events, and the solution.

Go ahead and ask me for what the story is behind this universe, and or behind Mido.

I will get the general basic things for you.

Mido is distant from people, hard to make long-term friendships when your friends keep turning into zombots.

Mido is biologically female, however they prefer non-binary pronouns. (Why did I make them non-binary if I'm going to say that they're biologically female? That's because it plays a role in how the character Acts.)

Mido was born during the outbreak, and and never got to know their parents to begin with. All they knew was the restoration, and that was perfectly fine with them.

Mido had a wispon that resembles a bubble gun (originally it was going to be more similar to a handgun but I figured bubblegun would have been more fitting).

When they join up in an experiment they're injected with an antivirus, not a cure per se but it does prevent the victim from turning into a complete zombot unlike the original virus. The antivirus itself does have some quirks, enhancing mobians to be even more supermobian than usual including stuff like enhanced brain processing power so on and so forth.

Reason why not everyone takes this antivirus is that there's a good chance that you could end up a zombot instead of a supermobian.

I got the idea of using a virus to stop a virus, kind of like how an unmovable object collides within unstoppable Force.

If you have any more questions feel free to ask, just know I might not be able to answer everything immediately. I might take time to actually tell you things, this is likely because I'm busy with real-world stuff or didn't get the notification.

#sonic fan character#oc#digital art#sonic the hedgehog#sonic idw#wispon#nonbinary#metal virus#the restoration#backstory#tragic#apocalypse#sonic is gone#17 years later

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Restoration: ‘As to things of State - the King settled and loved of all’

The Compromise Settlement of Charles II

King Charles II by John Michael Wright. Source: Wikipedia

FOR MANY former supporters of the Parliamentary cause, the Restoration must have been hard to take. For all the warm words of the Declaration of Breda, it must have felt to those that had followed John Pym, Arthur Heselrige, Oliver Cromwell and John Lambert, and especially the comrades of John Lilburne, that their own world had been turned upside down. For the Restoration, in so many ways, was precisely that. Not only was Charles II settled on his throne which in truth, by 1660, all but the most ardent republicans believed was the only way out of the constitutional impasse the Commonwealth had found itself in, but the House of Lords was re-established; the Church of England, including a hierarchy of bishops was reintroduced; the New Model Army was abolished and even the Divine Right of Kings was reinstated. It must have seemed to the advocates of the Good Old Cause that all those years of tumult, death and revolution were for naught: the Monarchy and all its works was back with a vengeance.

And of course, there was indeed vengeance. As described last time, the regicides that were still alive were pursued mercilessly by the new government, even the dead not being safe from the King’s wrath. In addition, the so-called “Cavalier Parliament” consisting of triumphal Royalist MPs, presided in many respects over a victor’s peace. The disestablishment of the New Model Army was, after the executions of the regicides, the most visible sign of a restored monarchy. The Army had been the instrument of Charles I’s defeat and the constant protector of the Commonwealth, and it had also been a major political player that forcibly dissolved Parliament after Parliament. To see this formidable military force that had destroyed the Royalist armies, crushed the Scots and ended the Irish Rebellion, simply disappear was no clearer sign that not only was the Parliamentary cause dead, but that the gravest threat to the Stuart regime was also no more - and without a shot being fired. The successor regiments that later became the Coldstream Guards and the Royal Horse Guards, comprised the core of a 7,000 man militia, loyal solely to the monarch - a situation that Charles I had long craved. These regiments would become the basis of the standing British Army, whose oath of loyalty remains to the monarch - an echo of the settlement of England’s civil wars.

Charles’ religious settlement was, on the face of it, a restoration of the Anglican Church in its prewar form. Episcopalianism was back, including in Scotland, supported by a new Book of Common Prayer. Bishops were also readmitted to a restored House of Lords, where they sit still. Despite Charles’ Breda promises of religious toleration, the Solemn League and Covenant was repealed, and the cause which had spurred the Scots into rebellion and war against the King’s government in the late 1630s was effectively suppressed. Although Charles himself was personally quite tolerant of different religious persuasions, including notoriously, Roman Catholicism, his Parliament was not. The confident Cavaliers remembered how hard the Presbyterians had tried to enforce their version of Protestantism on the three kingdoms; how the rule of the Major-Generals had tried to squeeze all joy out of Christian worship and, recalled with horror, the republicanism and threat to land ownership that millennial sects, sheltering within the ranks of the Levellers, had tried to introduce. A number of anti- Puritan bills were passed, most notably the Corporation Act of 1661 (which excluded non-Anglicans from public office) and the Five Mile Act of 1665 (which banned non-Anglican ministers from their former livings). These Acts effectively excluded Presbyterians and other low church groups from participating in the new political or religious establishment. This led ultimately to these disenfranchised faithful into forming their own churches. They called themselves Nonconformists and Dissenters, eventually formalising themselves into the various strands of Methodism. Within these churches the spirit of anti-Royalist and Anglican sentiment remained, leading ultimately to eighteenth century radicalism and part of the impulse that fuelled the desire for independence within Britain’s American colonies.

Scotland was freed of military occupation and its Parliament restored, but government garrison troops remained and Scotland never recovered the independent swagger it had enjoyed earlier in the century when it was able to interfere in the affairs of England and influence the outcomes of the civil wars with easy confidence. With its government impoverished and subservient, its independent military strength non-existent, its religion subordinated and the fault line between Highland and Lowland populations exacerbated by the civil wars, Scotland was a shadow of its prewar self. The days of routine Scottish invasions of England were over forever. In less than fifty years, Scotland’s mercantile class, faced with bankruptcy following catastrophic economic decisions and ill-advised colonial adventures, would petition the English Parliament and Crown for an Act of Union, granted in 1707, which would make the United Kingdom a political, as well as a monarchical, reality.

In Ireland, Charles’ government was focused and ensuring rebellion did not recur and made great efforts to rehabilitate, and reconcile with, the landowning Old English aristocracy and breaking the religious solidarity with the Old Irish rural workers and peasants that had driven so much of the rebellion’s early success. Charles’ own pro-Catholic sympathies helped this process, but he also did little to restrain Scottish Protestant settlement in the north and west, thus sowing the seeds of a sectarian conflict that would get ever more vicious over the next three hundred years.

But the Restoration was not absolute and Charles did not intend it to be, whatever the attitudes of the Cavalier Parliament. Charles had not spent half his life prior to his return on the run in order to simply repeat the mistakes of his father. Although not the constitutional monarch envisaged by George Monck, Charles nonetheless attempted to rule in partnership with Parliament. For Charles, his Divine Right to rule was a device to secure his legitimacy, not a principle by which a king should govern. There were several political factors that caused Charles to eventually dissolve the Cavalier Parliament in 1679, but new elections were held immediately. Unlike his father, Charles was never tempted by Personal Rule and was rarely in dispute with his Parliaments, unlike his predecessor governments. Parliamentary rule was solidified under Charles’ settlement in a way unimaginable in the years leading up to the civil wars.

Similarly, for all the anti-Puritanism of his regime, there was no systematic persecution of dissenters and no legal requirement for his subjects to adopt the new Prayer Book or the Anglican Communion. In Ireland, the ferocious oppression of Catholics and Irish self-determination was still in the future, and that would be driven principally by Protestant settlers, exacerbated significantly by the renewal of civil conflict in Ireland in the late 1680s. Charles was a cautious and astute man. His love affair with particularly, the English, population, had significantly dissipated by the end of his reign, but all his subjects, whatever their views of his government, were grateful to him for ensuring peace was maintained and that the conflicts that had led the inhabitants of the British Isles to fight and kill each other for years, were not reignited.

The immediate view of history, that lasted well into the nineteenth century, was that the British civil wars and the republican experiment were anomalies, best forgotten. The skill of the Stuart and Hanoverian regimes in suggesting the civil wars were no more than a family quarrel, quickly forgiven and forgotten, is the reason why there is no direct link between the proto-socialism of the Putney Debates and the the later Radicalism of the eighteenth century. Issues such as land reform and universal suffrage were effectively barred from public debate for 150 years.

Charles’ later reign did contain conflict and there was even a Radical attempt to kidnap the King at one point, but the most dangerous issue was that of the succession. A new political Parliamentary party, with a sneaking admiration for the Good Old Cause, called the Whigs, was formed determined to prevent the accession of Charles’ brother the openly Roman Catholic James, to the throne given the absence of a legitimate heir to Charles. A staunchly Royalist group which became known as the Tories formed to oppose the Whigs and support the Stuart succession. Thus the contours of future Parliamentary debate and factionalism began to take shape.

In February 1685, Charles died. There was, in the event, no challenge initially to James ascending the throne as King James II. However, the new monarch resembled his father in a haughty attitude and political ineptitude. The conflicts that drove civil wars would be reprised and, once again, absolute monarchy would be the loser.

#english civil war#charles ii#the restoration#Stuart monarchy#cavalier Parliament#radicalism#james ii

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Restoring The Smallest Clockwork

57K notes

·

View notes

Text

Part Four | Examining Apostasy: Addressing Bradley Campbell’s Contested Views on Latter-day Saints’ Beliefs

Addressing criticisms levied against Latter-day Saints’ beliefs, particularly concerning apostasy, often requires a careful and structured approach. Bradley Campbell’s interpretation of key biblical passages—Matthew 16:18, 2 Thessalonians, and 2 Timothy 4—challenges the LDS doctrines on apostasy, questioning the necessity of priesthood authority and apostolic succession. With his pedestrian take…

#2 Thessalonians 2:3#2 Timothy 4:3-4#Apostasy#Biblical Foundations for a Restoration#Biblical Prophecies of Apostasy#Church Authority#Joseph Smith and the Restoration#Latter-day Saint apologetics#Matthew 16:18#The Great Apostasy#The Restoration

0 notes

Text

In the cottage

#before they adopted their 4 children obv#jayvik so powerful it got me drawing agian#jayce Talis#Viktor Talis#yeah u heard me#idk how to draw them yet be gentle#Jayvik#jayvik fanart#misticarts#idk if Viktor would have his brace but in this headcanon Viktors body is restored to pre shimmer/hexcore/magic state an they r brace4brace

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Albums Of 2024

5. Neal Morse - The Restoration - Joseph: Part Two

0 notes

Text

"A tribal-led nonprofit is creating a network of native bison ranchers that are restoring ecosystems on the Great Plains, restoring native ranchers’ connections with their ancestral land, and restoring the native diet that their ancestors relied on.

Called the Tanka Fund, they coordinate donors and partners to help ranchers secure grazing land access, funds needed to install and repair fencing, increase their herd sizes, and access markets for bison meat across the country.

That’s the human part of the story. But as Dawn Sherman, executive director of the Tanka Fund, told Native Sun News, they’re “buffalo people” and these four-legged, 2,000 lbs. “cousins” are equal-part-protagonists.

The return of the bison means the return of the prairie, one of the three great grassland ecosystems on the planet, of which just 1% remains as it was when the Mayflower arrived.

“Bringing buffalo back to their ancestral homelands is essential to restoring the ecosystem. We know that the buffalo is a keystone species,” said Dawn Sherman, a member of the Lakota, Delaware, Shawnee, and Cree.

“Bringing the buffalo back to the land and to our people, helps restore the ecosystem and everything it supports from the animals to the plants to the people. It’s come full circle. That’s how we see it.”

As Sherman and the Tanka Fund help native ranchers grow their operations, everyone is well aware of the power of the bison to transform the environment: just as nations across Europe are, who are reintroducing wood bison to various ecosystems, for all the same reasons.

Sherman points out the variety of ways in which buffalo anchor the prairie ecosystem. The almost-extinct black-footed ferret, she points out, lived symbiotically with the bison, and with the latter gone, the former followed—nearly.

The long-billed curlew uses bison dung as a disguise to hide nests from predators. Deer, pronghorn antelope, and elk all rely on bison to plow through deep snows and uncover the grasses that these smaller animals can’t reach.

Everywhere the bison hurls its massive body, life springs in the beast’s wake. When bison roll about on the plains, it creates depressions known as wallows. These fill with rainwater and create enormous puddles where amphibians and insects thrive and reproduce. Certain plants evolved to grow in the wet conditions of the wallows which Native Americans harvested for food and medicine.

Native plants evolved under the trampling hooves of millions of bison, and that constant tamping down of the Earth is a key necessity in the spreading of native wildflower seed.

Indeed, Sherman says some of these native ranchers are bringing bison onto lands still visibly affected by the Dust Bowl, and already the animals are acting like a giant wooly cure-all for the land’s ills.

Since 2020, the Tanka Fund, in partnership with the Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council and the Nature Conservancy, has overseen the transfer of 2,300 bison from Nature Conservancy reserves to lands managed by ranchers within the Tanka Fund network.

“[T]he more animals that we can get the more of that prairie we can restore,” said Sherman. “We can help restore the land that has been plowed and has been leased out to cattle ranchers.”"

youtube

-Article via Good News Network, February 13, 2025. Video via Tanka Fund, July 17, 2024.

#indigenous#indigenous peoples#first nations#native americans#bison#ecology#ecosystem#ecosystem restoration#keystone species#endangered species#environment#prairie#great plains#land back#good news#hope#Youtube

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Where I stand on the ages of the characters is that Cream, Tails, Kit, Charmy, and Belle are kid-coded and the rest you can fuss with the ages a bit. Mainly because the Restoration is like two degrees away from being a paramilitary organization and the thought of kids running it is appalling to me.

#sonic idw#idw sonic#sonic fandom#sonic ages#sth#sonic#kit the fennec#miles tails prower#cream the rabbit#charmy the bee#belle the tinkerer#the restoration

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Has the restoration got a spelling or math bee?

Jewel stares at you blankly, "We're a charity/paramilitary organization, not a school."

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A caveat to this study: the researchers were primarily looking at insect pollinator biodiversity. Planting a few native wildflowers in your garden will not suddenly cause unusual megafauna from the surrounding hinterlands to crowd onto your porch.

That being said, this study backs up Douglas Tallamy's optimistic vision of Homegrown National Park, which calls for people in communities of all sizes to dedicate some of their yard (or porch or balcony) to native plants. This creates a patchwork of microhabitats that can support more mobile insect life and other small beings, which is particularly crucial in areas where habitat fragmentation is severe. This patchwork can create migration corridors, at least for smaller, very mobile species, between larger areas of habitat that were previously cut off from each other.

It may not seem like much to have a few pots of native flowers on your tiny little balcony compared to someone who can rewild acres of land, but it makes more of a difference than you may realize. You may just be creating a place where a pollinating insect flying by can get some nectar, or lay her eggs. Moreover, by planting native species you're showing your neighbors these plants can be just as beautiful as non-native ornamentals, and they may follow suit.

In a time when habitat loss is the single biggest cause of species endangerment and extinction, every bit of native habitat restored makes a difference.

#nature#wildlife#animals#ecology#environment#conservation#science#scicomm#pollinators#bees#butterflies#hoverflies#insects#native plants#habitat restoration#solarpunk#hopepunk#naturecore#wildflowers#good news

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

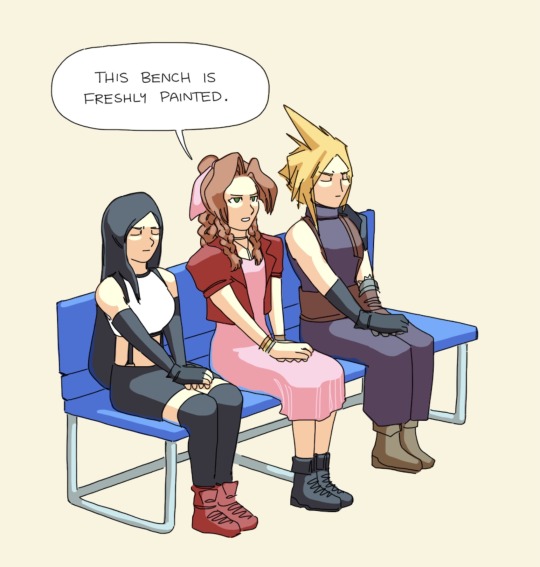

yeah thanks for the heads up

#prank'd. lol#shout out to my best friend the pretty blue benches of health restoration in remake#ffvii#cloud strife#tifa lockhart#aerith gainsborough#my art <3

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Return of the King: ‘And all the world in a merry mood because of the King’s coming.’

Charles Restored to his Throne

Source: The BBC

SO CLOSE to being able to resume his throne, Charles II displayed a subtlety and flexibility that had always eluded his father, in order to achieve his ultimate goal. In consultation with Monck, the exiled King and his courtiers, principally Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, drew up the Declaration of Breda, a conciliatory document, issued on 4th April 1660, representing Charles’ commitments to the English people, recognising the altered political reality of his soon to be reclaimed Kingdom. The Declaration promised an amnesty for all who had fought against the Stuarts, with the exception of those who had signed Charles I’s death warrant (the so-called “regicides”) and high-ranking republicans. The sale of Royalist estates would remain in situ; the Army’s pay arrears would be made good, and religious toleration extended to all but Roman Catholics. Crucially, regular Parliaments were promised, along with Parliamentary control of the Army. It was a masterful document, designed to placate majority moderate Parliamentary opinion, and by implication, promising no return to Royal absolutism. In this context, Parliamentary elections were held and resulted in a Parliament absolutely committed to the restoration of the King and the terms of the Declaration of Breda. This Parliament, officially called the “Convention Parliament”, given the absence of a constitution to sanction it, unsurprisingly became popularly known as the “Cavalier Parliament”. It did not take long for the new Parliament to take on the appearance of a government of the victors, for all Charles’ bridge-building.

There was one last attempt to resuscitate the Good Old Cause. John Lambert escaped from the Tower and sought to raise a republican army to oppose the Restoration, choosing his rallying spot, perhaps symbolically, as Edgehill, the site of the first battle of England’s civil wars. Some four troops of cavalry joined Lambert, but the Army, firmly under Monck’s control and seduced by Charles’ promises of pensions and back pay, at last turned its back on its former commander. Lambert’s force was soon outnumbered and overpowered by a New Model detachment under the command of one of the regicides, Colonel Ingoldsby, who took his former colleague into custody. Ingoldsby would go on to become a significant figure at Charles’ court, unlike Lambert, for whom a lifetime of imprisonment awaited. On 1st May 1660, the Declaration of Breda was read to both Houses with the understanding that it would form the basis of the restoration of the English monarchy.

The way was prepared. Nothing now stood in the path of Charles’ triumphal return to England. Following a formal and personal invitation to return home by Monck and Sir Thomas Fairfax, Charles set sail from The Hague and landed at Dover on 25th May and from there processed through Kent to the capital, greeted all along his route by cheering and ecstatic crowds. His reception in London, once the centre of Parliamentary revolt against his father, was little short of delirious, characterised by bonfires, tolling bells, tapestries hung from windows and fountains allegedly running with wine. He was escorted by 20,000 soldiers, most derived from New Model regiments - perhaps the greatest irony of what became known as “The Restoration”. On 29th May, Charles received loyal addresses from the Speaker of the House of Commons and the former Parliamentary commander, the Earl of Manchester, representing the Other House. Charles was then proclaimed King.

Although the Restoration is generally viewed as being bloodless and a typically English counter-revolution, there was in fact a considerable amount of reckoning. Despite the narrative being set that the Parliamentarians won the civil wars and that the restored monarchy was a shadow of Charles I’s Personal Rule, this is only partially true. Charles II did ensure Parliament passed an Act of Oblivion and Indemnity, which pardoned all who had fought with the Commonwealth’s armed forces, but many of the stalwarts of the Commonwealth were exempted from the Act. In addition to John Lambert’s life imprisonment, several army officers were executed, the most notable being the New Model general and Fifth Monarchist, Thomas Harrison, who was hung, drawn and quartered, meeting his grisly fate with the cheery confidence of someone who knew he would return at God’s right hand to wreak vengeance on his oppressors. Most of the regicides that the new regime could get its hands on were executed, but some survived or were rehabilitated by the new government. General Charles Fleetwood, head of the Army under the post-Cromwell Protectorate, for instance, despite being sentenced to death, managed to successfully claim he had been coerced into signing Charles I’s death warrant, although the fact Monck vouched for him was probably significant. Most of the Major-Generals managed to escape abroad, usually to Europe, while Edward Whalley fled to North America, where he sought refuge amongst the Puritan communities there. John Desborough actually plotted republican revolt from Europe. Extradited, he managed to avoid trial and ultimately retired to Hackney.

Thomas Fairfax, a known opponent to the trial of Charles I and a crucial figure in securing the success of Monck’s overthrow of the Commonwealth, received a royal pardon, and resumed his peaceful retirement, living until 1679, his reputation intact. Arthur Heselrige, fierce republican but scourge of the Protectorate, was perhaps an ambiguous figure to the Royalist regime. He was not arraigned for treason, but he was imprisoned in the Tower. Any ongoing debate as to what to do with the veteran Parliamentarian was resolved by his death within the year. Richard Cromwell, continued his somewhat charmed existence. After his deposition by the Army, Richard lived in exile in France, and was eventually permitted to return to England, dying in 1680. Richard’s brother Henry, often viewed as potentially a more effective successor to their father as Lord Protector, was left unmolested, and became part of the Anglo-Irish landowning class until his death in 1674. In acts of performative “justice”, the deceased regicides, Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, Thomas Pride and John Bradshaw, had their corpses exhumed, were posthumously beheaded, and their bodies publicly displayed as traitors.

The matter of retribution and punishment settled, Charles was now faced with ruling a much-changed English Kingdom and with reaching an equitable settlement with both Scotland and Ireland. Charles handled the post-civil war realms with dexterity and thoughtfulness, but his reign, although undeniably successful given the difficulties of his inheritance, did not do enough to fully resolve the issues of governance and sovereignty that had led to the destruction of his father, and he could not, ultimately, do enough to save the House of Stuart.

#english civil war#charles ii#the restoration#john lambert#george monck#charles fleetwood#Arthur Heselrige

1 note

·

View note