#The Abbey in the Oakwood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“The Abbey in the Oakwood”, by Casper David Friedrich (1810)

#The Abbey in the Oakwood#oil painting#casper david friedrich#1810#graveyard#loneliness#cemetery#romantic art#romanticism#Art#german art#Alte Nationalgalerie#landscape art#landscape painting#nature art#Turner#goethe#edvard munch#symbolism#fritz lang#f. w. murnau#The stages of life

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abbey in the Oakwood / Caspar David Friedrich

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809/10) by Caspar David Friedrich

#The Abbey in the Oakwood#1809#1810#Caspar David Friedrich#Romanticism#Halloween#spooktober#spooky season#Miss Cromwell#art#painting

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abbey in the Oakwood (c. 1809 / oil on canvas) | Caspar David Friedrich

#art#oil painting#fine art#painting#19th century art#landscape#landscape painting#gothic#dark aesthetic#dark art#romanticism#the abbey in the oakwood#caspar david friedrich#aesthetic#dark#church#gothic church#german art

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU'LL TAKE HIS LIFE BUT HE'LL TAKE YOURS TOO -- TROOPER BLOODY TROOPER.

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on Eddie the Head mascot of IRON MAIDEN notoriety as "The Trooper" 6 inch action figure by McFarlane Toys, photographed by RK*Pictures via Flickr, c. 2014.

EXTRA INFO: Background: "The Abbey in the Oakwood" (1809-1810) oil painting by Caspar David Friedrich.

"The bugle sounds and the charge beginsbut on this battlefield no one wins.The smell of acrid smoke and horses breathas I plunge on into certain death."

-- "The Trooper" (1983) by IRON MAIDEN, lyrics by Steve Harris

Source: www.flickr.com/photos/rkpictures/14126092410/in/photostream (all three found on Flickr).

#IRON MAIDEN#IRON MAIDEN band#Eddie the Trooper#The Trooper#Toys#Eddie the Head#80s Metal#Heavy Metal#UK Metal#Eddie Maiden#Up the Irons!#The Trooper 1983#Toy photography#1980s#McFarlane Toys#Action figures#Action figure photography#Union Jack#The Abbey in the Oakwood#80s#1983#Eddie The Head#Caspar David Friedrich#IRON MAIDEN The Trooper 1983#Toycore#IRON MAIDEN 1983

1 note

·

View note

Text

ABBEY IN THE OAKWOOD (c.1809) by CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH

ABBEY IN THE OAKWOOD captures the essence of the sublime. It’s not a happy picture. Death dominates the image, the crumbling tombstones, the dark clothes, the barren trees, and the destroyed buildings. Everything is decaying or dead. But all is not lost. The references to death and ruin are self-evident and undeniable, but there are other transcendental references to think about.

The painting shows the ruins of the ABBEY against the winter sunset with the pale moon rising above the horizon. Time is explored on a HUMAN SCALE, on a NATURAL SCALE, and on an ETERNAL SCALE. The ruins of the ruined ABBEY represent the HUMAN SCALE. Architecture is a human endeavor, just as this Gothic ABBEY, time can be mean to humanity’s achievements.

The large window shows that the ABBEY once had a bright stained glass façade; a roof once covered the interior; walls once encircled the parishioners; but now, all of this is in tatters.The ABBEY also symbolizes the various stages of human history; however, the ABBEY IN THE OAKWOOD now symbolizes this mighty age as passed and decaying.

The dark sunset and the cold landscape remind us of nature's daily and seasonal cycle. Every day has a sunset; every year has a winter. The sun goes down and the seasons change like clockwork. The sunset and the winter suggest the NATURAL SCALE which is much larger and longer than our HUMAN SCALE.

The moon is high above both the HUMAN and NATURAL SCALE. And this crescent moon in the painting symbolizes the ETERNAL SCALE. It is time on a universal scale. The phases of the moon started millions of years before the seasons and humans. It is essentially ETERNAL. The moon symbolizes the third and final time scale found in this piece.

ABBEY IN THE OAKWOOD was painted by CASPAR DAVID FRIEDRICH as a medium for the exploration of the human condition. In this painting, the landscape takes on a spiritual dimension and shows us that we are only one moment in a natural and eternal time frame. There are hints of renewal and rebirth.

#abbey in the oakwood#caspar david friedrich#casper friedrich#romanticism#human scal#natural scale#eternal scale

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are my favorite paintings by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich (1774 - 1840).

Above: The Monk by the Sea (1809)

Below: The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810)

#art history#romantic paintings#caspar david friedrich#art#romanticism#monk by the sea#abbey in the oakwood#mp

0 notes

Text

The Gothic in Classical Music History (1760s-1920s)

Intro Back in high school I fell in love with two things; classical music, and Edgar Allan Poe. I’ve always loved Halloween, October, spooky things, ghost stories, horror and slasher movies, etc. And I always loved finding classical music that was also spooky, or dark, or evocative of the same eerie experience of a cold and foggy October day. Thinking about these memories made me want to put together a short list of Gothic Classical music.

But what do I mean? There is no true “Gothic music” as in a specific movement in classical history, because the traditional Gothic refers to literature. Not all art movements have corresponding trends in all mediums. Even so I thought it would be fun to say, if there was such a thing as Gothic music, what would that include?

18th Century

John Henry Fuseli - The Nightmare (1781)

Music of the 1760s-1790s, corresponding with the first wave of “Gothic Novels” in the English language. Some names in this era include Horace Walpole (The Castle of Otranto), Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries of Udolpho, The Italian) and Charles Brockden Brown (Wieland). The closest we have to music of this same era would be in the Sturm und Drang style. Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) was used to describe music written in a minor key that was restless, agitated, intense, emotional, and more extreme than the typical expectations for restraint and lightness/clarity, music that aristocrats in powdered wigs and velvet and lace could relax with. Strong changes of emotion and more emphasis on subjectivity, reflected by sudden modulations and pulsing rhythms.

The most famous piece that I associate with Sturm und Drang is Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s “little” g minor Symphony no.25, K.183 (1773). It is famously used in the opening of Miloš Forman’s Amadeus (1984). It is a fun piece, and that opening movement is full of fire, and probably the young Mozart having fun (he wrote it at 17. If you ever want to lower your self esteem, look up what music Mozart wrote at your current age.). Another major work would be Joseph Haydn’s “Farewell” Symphony no.45 (1772), written in the very unusual for the time key of f# minor. And of course, even though he comes later, anything Ludwig van Beethoven published in a minor key has a lot of muscular passion to it, and his early/classical era of the 1790s is no joke. Check out the final movements of his Piano Trio no.3 in c minor and his Piano Sonata no.1 in f minor, or his most famous early sonata, the Pathetique.

But if the Sturm und Drang style and Gothic genre also emphasize the disturbed and the psychological, we can include programmatic works that do the same. Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni (1788) has an incredible moment in the finale. The sociopathic hedonist is confronted by the ghost of the man he murdered in the first act, who possesses a statue and confronts Don Giovanni with his sins. Don Giovanni doesn’t repent, so he is dragged into hell with a chorus of demons. Always a good reminder that Mozart wasn’t the eternal child who wrote pretty melodies.

19th Century

Caspar David Friedrich - The Abbey in the Oakwood (1810)

Music of the early 19th century corresponds better with Gothic fiction because Romanticism in art brought greater interest in the supernatural, in the subjective, in emotional reactions to the universe… major names in fiction include the poetry of Lord Byron (Darkness), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein, The Last Man), and Sir Walter Scott (The Bride of Lammermoor). Greater emphasis is put on the anxiety of the unknown, supernatural fears beyond our control.

Of all Franz Schubert’s songs, Erlkönig (1815) best exemplifies the Gothic (and this is a bold claim because I only know about a fraction of Schubert’s extensive song output). In it, a father and son are riding on horseback. The son is sick with fever. As they ride, the son cries out that he can hear the Elf King calling out to him, some evil spirit or demon that wants to take the son’s life. The father tries to calm him down, but the Elf King gets closer and closer. By the time they reach home, the son has died. Was the Elf King real? Was the son hallucinating from fever? How literal should we take this text? The ambiguity of subjective experiences and how we interpret and understand reality is a major theme in Gothic fiction.

Many famous German operas lean into the supernatural and magical. In this period we get Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz (1821), considered to be the first Romantic opera. In it, our main character Max who needs to win a shooting contest so he can be allowed to marry his lover, Agathe. He is given a gun that can shoot magic bullets by another forrester Kaspar (who has his own plans). Kaspar tells Max to meet him in the “Wolf’s Glenn” in the woods at midnight for more magic bullets. In the Wolf’s Glenn, Kaspar calls for a spirit, the Black Huntsman Samiel, to help him curse the other characters, offering Max’s soul in exchange. Making deals with demons/the devil was another fascination in Romanticism.

Legends of a diabolical nature were springing around great musicians. At the end of the 1700s, Giuseppe Tartini wrote his most famous composition, the “Devil’s Trill” Violin Sonata in g minor which is full of virtuosic passages. Tartini claimed that the Devil appeared to him in a dream, and that he sold his soul in exchange for the Devil to be his servant. He handed the Devil his violin, and the Devil “…played with such great art and intelligence, as I had never even conceived in my boldest flights of fantasy. I felt enraptured, transported, enchanted: my breath failed me, and I awoke” Source

Similar stories came about with violinist Niccolò Paganini, who astonished the audiences of the early 19th century with his (for the time) otherworldly technique, dazzling them with scales and leaps and scratches the likes of which you can hear across his 24 Caprices for solo violin. A young Franz Liszt was at one of Paganini’s concerts and he was enthralled and inspired to become the “Paganini of the Piano”. He too would dazzle audiences with his percussive intensity, glittering arpeggios, and dreamy modulations to possess women with the spirits of hysteria and other dated misogynistic diseases. Cliche to say but before Bieber Fever, before Beatlemania, there was Lisztomania.

The sense of Faustian bargains comes through in the pieces Liszt wrote after Goethe’s Faust. The Faust Symphony (1857) includes a movement for Mephistopheles, the demon/ the Devil that bargains with Faust. The Mephistopheles movement has no original theme, but takes and corrupts the themes of Faust and his lover Gretchen into a mocking tone. Later on, Liszt was inspired to write a tone poem “The Dance in the Village Inn” or Mephisto Waltz no.1 (c.1862). He also wrote it for piano around the same time. The story has Mephistopheles taking Faust to a wedding in a village and playing the violin so madly, the partygoers are intoxicated by the music and go off dancing in the woods. Emotions taking over and making one act irrationally was another fascination in Gothic fiction.

Liszt would go on in his later years writing a few more Mephisto waltzes, with a lot of forward thinking harmonies and piano writing, unfortunately not as popular. Mephisto waltz no.2 (1881) has moments that make me think of Debussy, and the third (1883) has glittering and ethereal moments. But the best example of Liszt’s interest in the Gothic would be his earlier concert piece Totentanz (1949), or Dance of Death (Danse macabre). In it, the piano and orchestra play out variations on the Medieval chant Dies Irae, always reminding us of the inevitability of death. The variations depict skeletons dancing wildly all while the Mephistopheles at the piano unleashes his seductive tones.

The Dies Irae chant goes across our pop culture, with one famous iteration being a synthesized version of passages from Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique that Wendy Carlos wrote for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) after Stephen King’s novel of the same name. And it was Berlioz’s symphony that enchanted audiences in 1830 with new, titanic sounds beyond what orchestra music had been before. In the story of the Symphonie fantastique, an artist has tried to overdose on opium after feeling rejected by unrequited love, but instead he has a vivid drug induced nightmare where he is sentenced to be beheaded via guillotine, which was still a traumatic living memory for the Parisian audience. He then sees himself among ghosts and monsters during a witches’ sabbath, the lovely woman’s beautiful theme is distorted into a grotesque mockery, the Dies Irae comes back among the cackling. It was a new degree of imagination expected from the audience. Later, Berlioz would depict demons in Pandæmonium (the Capital of Hell in Dante’s Inferno) at the end of his Damnation of Faust.

Through the mid to late 19th century we get authors of Gothic literature such as Edgar Allan Poe, Elizabeth Gaskell, Emily and Charlotte Brontë, Nathaniel Hawethorne, and Victor Hugo. We also get two more operas that have Gothic themes. First is Richard Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman (1843). In this opera, a ship on the North Sea collides with the Ghost Ship of the Flying Dutchman who is cursed to sail the seas forever, but is allowed to come ashore once every seven years and if he can find a wife, he will be freed. I’m sure you can guess how this opera ends. The overture is often played in concert for a condensed version of Wagnarian thunder and romance. The next important opera is Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth (1847), because Shakespeare was being revived and translated in different languages across Europe and Verdi loved his plays. In the opera, Macbeth comes across a chorus of witches that foretell his success and downfall. He is too ambitious and goaded by Lady Macbeth, plans to take the throne through deception and murder. Lady Macbeth is later haunted with phantom blood on her hands which only she can see. And Macbeth succumbs to his inevitable fate.

We also get two significantly “Gothic” pieces of orchestra music. They are both tone poems, which also reflects the concert goers’ tastes. The one that has always been a quintessential “Halloween classical” piece is Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre (1875), opening at the stroke of midnight (softly evoked by the harp), a violin shrieks out the tritone (the “Devil’s interval” which the Romantics thought meant was cursed by the superstitious Medievals, really it was an idiom for “hard to use in music”) and introduces ballroom music along with the clacking bones of skeletons dancing in the graveyard (evoked by the xylophone). The skeletons dance through the night until the rooster crows at dawn.

The other great Halloween concert piece is Modest Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain (1867) which depicts another witches sabbath, this time on St. John’s Night, a major holiday in Slavic Eastern Orthodox culture. Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940) would help bring this poem to life with an animated phantasmagoria of ghouls and skeletal horses and other demons flying around the mountainous demon Chernoberg.

[Here I want to give a quick shoutout to Cesar Franck’s Le Chasseur maudit (The Accursed Huntsman), a tone poem about a Count who doesn’t go to church one Sunday, and instead rides around to whip peasants for his own amusement, so demons drag him to hell. Not nearly as famous a concert piece as the others mentioned in this list but it has colorful orchestration so you should check it out.]

The initial idea for Fantasia was for Disney to repopularize Mickey Mouse by writing him into an animated version of Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. The original poem by Goethe was a classic that Paul Dukas set to music in 1897. In it, we hear the Sorcerer leave his Apprentice to clean the floors of his workshop. The Apprentice uses magic to bring a broom to life so it can do the chores for him. The Broom mindlessly pours buckets of water all over the floor, and the Apprentice isn’t good enough with magic to stop it. He chops it up into pieces with an ax, but they regenerate into several brooms which go back to marching water in. The Sorcerer returns to clean the mess and scolds his Apprentice. This charming tale has a darker and more diabolically fun tone in Dukas orchestra.

20th Century

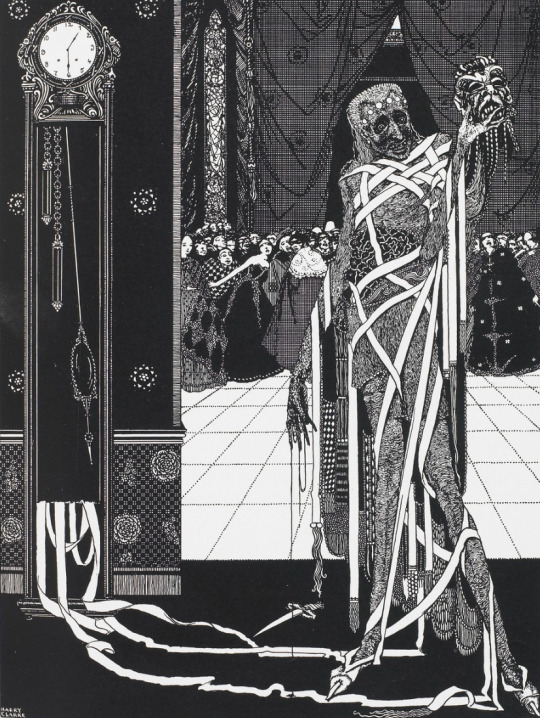

Harry Clarke - Illustration for "Masque of the Red Death" (1919)

In the same exact year of Dukas’ tone poem, we get Bram Stoker’s Dracula. At this turn of the century other major names include Gaston Luroux (The Phantom of the Opera), Robert Lewis Stevenson (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), Henry James (The Turn of the Screw), Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Gray). At this time, there are a few more pieces that continue trying to evoke Gothic subject matter. One comes from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony no.7 (1905), sometimes dubbed “Song of the Night”. Two of the symphonies five movements are titled “Nachtmusik” (night music), the first is more in line with Gothic anxiety and spookiness than the second which is more like a serenade. But the most Gothic movement is the Scherzo which sits in the middle of the symphony and is like a Viennese ballroom full of dancing corpses and skeletons as waltz music decays with them.

A surprising example (at least, because of how relatively obscure it is) comes from Claude Debussy with parts of an opera based on Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher that he worked on between 1908-1917. Not too much a surprise on the one hand because French translations of Poe’s work became popular and influential. On the other hand Debussy is more known for evocative sound pictures, unique musical colors, and subtlety. Perhaps he was drawn to symbolist and psychosexual interpretations of The House of Usher, the same interests that preoccupied him with his only finished opera Pelleas et Melisande. Roger Orledge reconstructed the opera and tried to stay true to Debussy’s style, so what we do have is passable and as shadowy and vague as his other orchestral masterpieces.

Maybe the hardest work to recommend (but I do recommend regardless, give it a chance) is a Modernist song cycle for chamber ensemble. Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (1910) uses freely chromatic atonality to give a demented color of psychosis experienced by Pierrot, personified version of a stock character for old Commedia dell Arte plays, a clown who over time became the “sad clown”. Maybe a precursor to the demon from Stephen King’s It, or the demented clowns and jesters that laugh at the madness of the cosmos across Thomas Ligotti’s short stories.

This was only meant to be a small overview of works that could fit my own view of the Gothic in music. There are more examples I could include, so as a hint toward today, I’ll end with a piece that was written about a century ago, yet sounds as if it could have been written today. Henry Cowell’s The Banshee (1925) is a short piano piece, so if you can, at least listen to this one. Instead of playing with the keys like you’re “supposed to”, Cowell asks the performer to drag their fingers along the wires directly. This creates disturbing reverberations and scratching sounds that tingle the back of your neck, that feel like the otherworldly cry of a Banshee.

Happy Halloween.

#classical music#Halloween classical#Halloween#Halloween music#Mozart#Haydn#Beethoven#Schubert#Liszt#Paganini#Berlioz#Saint-Saens#Mussorgsky#Wagner#Verdi#Dukas#Mahler#Debussy#Schoenberg#Cowell#Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart#Josef Haydn#Ludwig van Beethoven#Franz Schubert#Niccolo Paganini#Franz Liszt#Hector Berlioz#Camille Saint-Saens#Cesar Franck#Franck

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

-The Abbey in the Oakwood-

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Oliver, Upstream

Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood

#spilled thoughts#quotes#reading#currently reading#book review#booklr#books#love#bookish#life#mary oliver#sorrow#literature#poetry#poem

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abbey in the Oakwood (Caspar David Friedrich, 1809-10)

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

art history playlist moodboard – haunting songs for celebrating halloween all year

Country House by Moonlight – Wilfred Bosworth Jenkins // Vanitas Still Life – Aelbert Jansz van der Schoor // Procession in the Fog – Ernst Ferdinand Oehme// Crypt of the Capuchin Friars – Oscar Parviainen // The Abbey in the Oakwood – Caspar David Friedrich // Anguish – August Friedrich Schenk // The Premature Burial – Antoine Wiertz // The Old Trinity Churchyard at Potsdamer Bahnhof in Berlin – Wilhelm Thiele // Night on the Dniepr – Arkhip Kuindzhi

#art history playlist moodboards#charlotte makes moodboards#charlotte's playlists#spooky aesthetic#haunted aesthetic#paranormal#spooky#haunted#dark aesthetic#cemetery#graveyard#wilfred bosworth jenkins#ernst ferdinand oehme#caspar david friedrich#august friedrich schenck#antoine wiertz#arkhip kuindzhi#music#my music taste#music moodboard#art#art history#tw skull

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love slacking off at work. Just did this sharpie and pen recreation of The Abbey in the Oakwood by Caspar David Friedrich on a book spacer

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caspar David Friedrich's Abbey in the Oakwood, 1810

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caspar David Friedrich

Everybody, may I present to you my favorite works from Caspar David Friedrich

Monastery ruins in the snow (1819)

West facade of the ruins of Eldena (?)

Winter (1807-08)

Cross and Cathedral in the Mountains (1812)

Cross in the Moutains (1806)

Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1794-1798)

The Abbey in the Oakwood (1809-1810)

(a few of this aren't black&white, but I liked the vibe, so here a few colored)

#art#caspar david friedrich#im in love#just look at this#beautiful#this is what i wanna study at school when we'll talk about friedrich

3 notes

·

View notes