#THE TRANSFORMATION STORIES INHERENT TO THE FAIRYTALE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ok but look I haven't looked at ouat stuff for years but captain swan being in that ao3 ship poll is giving me the ascending delight of reading tags w ppl declaring killian so gender and YES. YES YEEESSSSSS SO TRUE BESTIES

#my whole fuck could you imagine if that show were airing today I have THOUGHTS AND FEELINGS#the way that fandom was so overwhelming compcishet WHEW#fr today it would just be baseline recognition that all canon killian ships were bi4bi it wouldn't even be a question#GOD THE GENDER OF OUAT#THE TRANSFORMATION STORIES INHERENT TO THE FAIRYTALE#SOCIETY IF OUAT TODAY FFFFFF#lmao no it would still be trash but like#less trash trash#anyway the little circle of fandom I hung out in was in 3008 soooo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

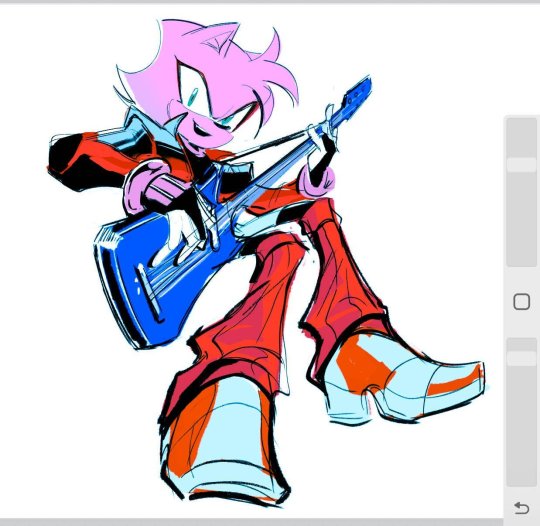

my Metamy kid!! his name is Dusty Rose :D ft. single mom Amy Rose and Absentee baby daddy metal sonic LOL

his name's Dusty Rose after Dusty Miller, a plant that looks like metal/silver. Dusty Rose is also a pink color ! it also rhymes with Rusty Rose. im so smart (/j)

born from Metal Sonic's core and infused with Amy's biosignature, Amy and Metal Sonic had a very brief 'thing'... eventually Metal Sonic was soft rebooted and sent away yet again, but he left a piece of himself (part of his 'core'? infused with chaos energy..?) to Amy, which then became Dusty. leaving Dusty as the last true remaining testament of their love

(I just love the idea of Amy with a Waitress style character arc... finding love again in raising her child and not the way she used to think, being spent with another person)

Dusty would be very fixated on the idea of love, after all his mother raised him on the notion of that. Amy's standards for true love and fairytale romance have definitely changed being with Metal Sonic, but the root message being that love is all encompassing and transformative.

He was 'created' to look like Mobian, and Amy treats him no differently than any other Mobian/human. Still, he believes that he should hide all the parts that 'other' him from society, which means his robot parts. (legwarmers!)

He's got a bit of a bad boy edge to him LOLLL i kind of created him that he'd be an emo kid. (fall out boy.. my chemical romance.. a bit of IDKHow) really good at electric guitar and part of a band. eventually he finds his passion is in lyric-writing (all those love stories and inheriting his mother's gift for writing love letters)

he often wonders what a beating heart is like, as someone without one. he's interested in the heartbeats and the pulses of others, but he is a total sweetheart himself.. still, even to other mobians unaware that he is an android (a weapon at that), it's still a little off-putting..

more abt him belolow

Dusty's core is already made/designed after Amy's biosignature, and in meeting other people, he's able to read their biodata and stash it into an archive, but he doesn't reproduce it onto himself. (though unsure if he could? either his code has a blockade or he chooses not to)

Dusty, additional to his stash of weapons, has the ability to shift too like his papa... become something similar to Metal Overlord but not entirely... like a half robot dragon boy or smth.. IF he's under the right conditions to have it pulled out of him. or something

Dusty DOES "grow" up. basically, he's an inorganic being whose core is trying to emulate/copy the growth progression of other organic beings.

As it would grow in size (and Dusty's cognition "matures"), his mother and her friends would modify as needed to adjust his frame, etc, but rarely were things ever replaced. Like a mollusk, its shell growing in size- but one needing accommodations. A heart bigger than its own body that threatens to spill- a chick that has outgrown its shell, well before its expected date- needing modifications to keep it inside and protected

Metal Sonic and Amy would have something profound-- one of those tragic, star-crossed enemies-to-lovers dark fantasy romance stories Amy's always loved to read about- but then having it play in real time and having to come to terms with the real world implications of actually having one. It's just that- a fantasy. and metal sonic would grapple with the ideas of love, which i think would be inherently dark and a little possessive given his upbringing-- but what him and Amy have would be sweet at the very core of it. so him giving a piece of his core that reads and adapts to Amy's biosignature and oops... accidental baby....

Dusty finds himself drawn to music. his mom and dad couldn't quite communicate love language physically (with Metal Sonic's claws and his lack of mouth) so I hc that Amy taught Metal Sonic how to hum and sing and communicate their love through music and vocalizations (which carried onto Dusty)

4th pic is Dusty doing breathing exercises with his mama... Dusty gets embarrassed super easily so him and Amy would regularly do breathing exercises so he doesn't overheat like a PC

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In The Heart Of Winter

Summary: Once upon a time, there was Winter itself—flawless, endless, and untouched by sorrow. A figure carved from ice and perfection, admired but distant, powerful but hollow. It knew no warmth, no ache, no reason to change... until one night, a boy lost in the snow stumbled into its heart— and cracked it open with nothing but kindness, and the glow of a gentle smile. Years later, that boy, now a young man named Yuuri Katsuki, stands alone on a frozen beach in Sochi, crushed under the weight of grief and failure. After messing up his chances at the Grand Prix Final and losing his beloved dog, Vicchan, Yuuri runs to the sea, too ashamed to go home, convinced he’s wasted everything he once dreamed of becoming. A fairytale for those who believe winter is not only an ending, but the beginning of a love that defies even time—and who know that even the coldest hearts can be set on fire.

READ HERE

"In the Heart of Winter" is a story born from my love of old winter myths — particularly the figure of Jack Frost, and the darker, bittersweet fairytales of Russia.

In traditional Russian folklore, winter spirits were often both beautiful and cruel, protectors and punishers, symbols of the inescapable cycle of death and renewal. Tales like Morozko (Father Frost) show winter as something vast and personified, but not inherently evil — more a force of nature bound by its own strange rules, capable of great kindness or great indifference.

Another tale that shaped this story is Snegurochka, or The Snow Maiden — a girl made of snow who longs to feel human warmth and love. In many versions, she melts the moment she feels true affection or steps too close to the fire. Her story isn’t about punishment or fear — it’s about transformation, the cost of wanting something you were never meant to have, and how even the coldest forms can carry longing inside them. I wanted to thread that same ache through Viktor — the coldness not as cruelty, but as distance, perfection, and the absence of anything that could move him… until someone does. I wanted to blend that ancient sense of mystery with the emotional world of Yuri!!! on Ice — to imagine what might happen if a lonely boy once touched the heart of such a being, and if that god, bound by cold eternity, could not forget.

This story exists alongside the canon timeline at one point, behind Yuuri’s collapse at the Sochi Grand Prix and the grief of losing Vicchan. And also, I adapted Viktor and how we see him in the anime as an untouchable god of the ice, perfect but almost too distant and cold in his own beauty and powerful talent. But how hollow and jaded by his own perfection he was... but most of all, how he lost his motivation and purpose but found it again after someone set his heart on fire.

"In the Heart of Winter" is a tale of longing, soft fluff and smut, and the terrible but beautiful price of choosing selfless and true love. I hope you enjoy walking with Yuuri and Viktor through this world of snow... and the small, stubborn warmth that can change even the oldest winters.

This is fully written and I will upload everything over the coming weeks.

#russian folklore#yoi#yuri on ice#yurionice#yuri!!! on ice#yuri!!!on ice#ユーリ!!! on ice#katsuki yuuri#victor nikiforov#viktor nikiforov#yoi fanfiction#Victor Nikiforov#Viktor Nikiforov#Viktuuri#Victuuri#vikturi#victuri#yuuri katsuki#fanart#anime fanart#yoi fanart#yuri on ice fanart#fanfic#yoi fanfic#trending#artist on tumblr#writers on tumblr#creative writers

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've thought this before but I am re-reading Argenti's character stories rn and they give me a creepy feeling, every time. There's something about the way they're written that makes it sound like something's not as it should be, something's wrong, like a rotten apple covered in gold foil, so you don't see its black core.

Over time, the melodic strains faded into the recesses of his memory, becoming a mysterious and elusive moment.

He vanquished nightmarish monsters, and with the arrival of spring, rabbits frolicked once again in the woods.

This is so.. taken out of a picture book fairytale. It feels unreal.

The profane words of the Triple Demons resembled fragmented ravings, morphing into manifestations of human desires.

When he finally encountered his former comrade, he found a knight who had become a fanatic, lost in a blind pursuit of power. The former hero who had wielded a legendary weapon and vanquished the sky devourer had degenerated into a beast. His armor transformed into the scaly hide of the behemoth he had slain, his weapon into unyielding claws and fangs, and his blood into a viscous and restless flame. His eyes, once filled with wisdom, now burned with untamed wildness. The voice that had once addressed him as "my dear friend" had dwindled to a hissing cry.

..but has he really degenerated into a beast, or is that just how Argenti suddenly saw him? Because of his actions, his attitudes..? How literal am I to take these descriptions if we don't see them on screen? If Argenti can see Beauty in the inner world of a creature others consider a monster because they fear it, can he not also see darkness and evil in the inner world of a beautiful person? So much so that they become a monster in his eyes?

I think I best describe it as his story gives me the same vibes as Pan's Labyrinth. I've always subscribed to the theory that in that film the fantasy elements we see are Ophelia's way of coping with the terrible reality she is trapped in (the civil war, her mother, etc). Her mind produces these insane, wondrous but also partly truly terrifying creatures and places - such as the monster representing the punishment she fears (or her guilt?) for eating / stealing food after she's been denied food in "the real world". (If you haven't seen this film, I strongly recommend it - but be aware there are brutal civil war scenes and it's not a happy film).

Of course we could say this is just Argenti's warped view of the cosmos - he is poetic, he sees Beauty in strange things, he also focuses on Beauty in all things. The way he talks is certainly unusual. But in the same breath we could argue that perhaps his mind is blocking things and turning them into something absurd, almost, because he cannot cope otherwise. He grew up in war, he's suffered loss and loneliness, everywhere he goes he sees evil and he seems to have an inherent and very strong moral code of what is acceptable to be and do and what constitutes sin and failure and ugliness.

He seems very stable and independent, albeit odd, but I think there is a possibility that something terrible lurks inside him that's been locked away in an ugly little box, covered in thorns and sunken to the bottom of a well. It cannot be let out, so instead his mind sees the world in terms of Evil and Beauty, both grotesquely exaggerated at times.

Will he, himself... succumb to the clutches of the Omen of Evil?

More importantly - is the Omen of Evil an external force or is it his own failure to withstand these things the Knights seem to arbitrarily consider evil, ugly and repugnant (as their approaches differ from one another)?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dark Origins of Sleeping Beauty: Cannibalism, Curses, and Gothic Horror in Fairy Tales

iry tales, as we know them today, are often softened, sanitized versions of their grim past. Before Disney transformed them into magical adventures for children, these stories were cautionary tales—dark warnings about the dangers of vanity, betrayal, and death.

Fairy tales often arrive in our lives as bedtime stories, wrapped in glittering enchantments and happy endings. But the origins of these tales are far from innocent. Before Disney gave us a spellbound princess awakened by true love’s kiss, Sleeping Beauty was a harrowing parable. One that was drenched in themes of sexual violence, cannibalism, and the grotesque misuse of power.

Just as Snow White's tale hides murder and necrophilia under a frosted sugar coating, Sleeping Beauty's story is another gothic lesson in vulnerability, control, and the fine line between magic and malevolence.

The Origins of Sleeping Beauty: The Maiden and the Monster

The earliest version of the tale appears in Sun, Moon, and Talia, written by Giambattista Basile in the 17th century, a piece so disturbing that it makes the Grimms’ version seem almost wholesome.

In this Italian rendition, the beautiful Talia is not awakened by a kiss. She is raped by a king while still asleep, and later gives birth to twins while unconscious. One of the babies sucks the poisoned flax from her finger, waking her at last, not into a fairytale romance, but into trauma, confusion, and motherhood.

Later, the Brothers Grimm offered a more subdued version titled Briar Rose. Their 1812 retelling, while still dark, replaced outright violation with magical sleep, replacing rape with a kiss and softening the implications of power imbalance. Yet even the Grimms could not fully erase the unsettling themes inherent to the tale.

Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty: The Ogress, the Children, and the Forgotten Ending

While most people credit the Brothers Grimm for the story of Sleeping Beauty, it was Charles Perrault who first gave us the French literary version of La Belle au Bois Dormant in 1697. His tale straddled the line between Basile's grotesque realism and the Grimms’ sugar-spun fantasy. Perrault preserved the darker undertones: a princess fated to sleep for a century, a mysterious prince who awakens her, and a deeply gothic twist: the prince’s ogress mother, who plots to devour Aurora and her children.

This macabre subplot, often omitted from modern adaptations, is a classic gothic turn: a monstrous mother figure, cannibalism, deception, and a pit of vipers. It ties the story back to ancient fears of motherhood, bloodlines, and the consuming power of time.

The Curse: A Death Sentence for Beauty

In most versions, the story begins with a royal birth and a celebration interrupted by a neglected, vengeful fairy. The fairy curses the baby, often out of petty slight: a forgotten invitation, a perceived disrespect, and foretells that the princess will prick her finger on a spindle and die.

The "spindle" here is no arbitrary object. In folklore, spinning is tied to fate and femininity, often symbolizing the inescapable weaving of one’s destiny. To prick her finger on it is to bleed for her beauty, for her gender, for her symbolic purity.

Later softened into a sleep rather than death, the curse nonetheless retains its fatalistic edge. The girl is doomed from birth, her beauty both her blessing and her executioner.

The Sleeping Maiden: An Image of Passive Perfection

Sleeping Beauty: Aurora, Talia, Briar Rose, Églantine, represents a gothic ideal of femininity: silent, still, pure, and untouched. In many ways, she is a living corpse, a figure preserved in time, suspended between life and death. The image of a beautiful girl asleep in a tower for a hundred years is haunting not because of the magic, but because of the implications:

She is powerless. She is objectified. She is violated, either symbolically or literally, in nearly every version of the tale.

In the darker variants, men come to her tower not to rescue, but to claim. In Sun, Moon, and Talia, the king takes her body without consent. In other stories, she is married while asleep. These elements reveal the disturbing power dynamics underpinning many older fairy tales: where female bodies are property, and beauty is both armor and curse.

The Thirteenth Fairy: The Rejected Outcast as Gothic Catalyst

The villain of Sleeping Beauty, the wicked fairy or spiteful witch, is not inherently evil. She is an outsider, denied inclusion, and her curse is retaliation against a world that has dismissed her. She is a classic gothic figure: the Other, the shadow, the spurned woman turned monstrous.

Her curse is often seen as an overreaction, but viewed through a gothic lens, it is a scream for recognition, a violent assertion of power in a society that ignored her. Some scholars view her as a proto-feminist figure, twisted by rejection, yes, but also bold enough to challenge royalty.

She embodies the darker truth of the tale: that one’s fate can be shaped not by love, but by neglect and resentment.

The Castle: Fortress, Coffin, and Cathedral of Sleep

The castle where Aurora lies sleeping is a potent symbol. Encased in thorns and silence, it becomes a tomb, a fortress of forgotten time, and a metaphorical womb of death and rebirth. The world outside changes and decays while the girl remains perfectly preserved.

In gothic literature, castles are often places of madness, decay, and isolation. Here, the enchanted castle becomes a cathedral of suspended time. Nature reclaims the land, and only a “true” prince may cut through the briars. But what does that mean? That only royalty can “rescue” a woman from her fate? Or is the forest a symbol of untamed femininity: a wall of nature grown wild in defiance of time?

The “Kiss”: Love or Possession?

In the sanitized versions, a prince stumbles upon the sleeping maiden, kisses her, and she awakens. This is presented as romantic, a triumph of love. But strip away the gloss and what remains is disturbing:

A man kisses a woman who cannot consent. A man claims her before she awakens.

Even in the Grimm’s telling, where the kiss is less explicitly sexual, it remains a gothic metaphor for the male gaze, desire enacted upon a passive woman, the fantasy of love with no resistance. The motif has deeply influenced modern horror and gothic romance, where the sleeping or comatose woman is both desired and feared.

The Ogre Queen: Cannibalism and Court Intrigue

Charles Perrault’s La Belle au Bois Dormant adds a grotesque postscript rarely included in modern adaptations. After the princess and prince marry, his mother, the queen, turns out to be an ogress who craves human flesh. She demands to eat the children of Sleeping Beauty: Aurora’s own son and daughter, named “Dawn” and “Day.”

A cook spares the children, but the queen is eventually exposed and punished, thrown into a vat of vipers and toads. This cannibalistic subplot, largely forgotten in pop culture, is a striking echo of the Snow White queen’s hunger for her stepdaughter’s heart. It reminds us that the danger is not only male predators, but also monstrous maternal figures—twisted by jealousy, hunger, and ancient rage.

The Gothic Legacy of Sleeping Beauty: Themes and Reflections

Sleeping Beauty in Modern Culture: From Maleficent to Madness

While Disney’s Sleeping Beauty (1959) immortalized the aesthetic—pink gowns, fairies, spinning wheels—it omitted the raw fear at the heart of the story. Maleficent became a misunderstood villain in modern retellings, reclaiming some of the agency stripped from the original “evil fairy.”

Films like Maleficent (2014) complicate the original tale, reframing the kiss as maternal love and challenging the notion of male rescue. Meanwhile, gothic reinterpretations such as The Company of Wolves and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber delve deep into the sexual violence and female awakening inherent in the original myths.

The Lasting Legacy of Sleeping Beauty

Sleeping Beauty is not a tale of romance. It is a cautionary fable about power, silence, and predation. Beneath the dreamy aesthetics lies a skeleton of horror—sleep as death, beauty as bait, love as ownership.

In the gothic tradition, this story endures because it speaks to the fear of being powerless, voiceless, and reduced to a symbol. But it also whispers of awakening—of emerging from darkness, of reclaiming agency after centuries of sleep.

Perhaps that is the most haunting aspect of all: Sleeping Beauty is not just about a girl waiting to be kissed. It is about the world that allowed her to fall asleep in the first place.

OCD Vampire

#gothic bite magazine#goth#gothic#gothcore#gothic aesthetic#ocd vampire#medieval#armour#knight#medieval art#middle ages#sleeping beauty#disney princess#sleeping beauty 1959#grimm fairy tales#fairy tales#fairy tale aesthetic#fairy tale vibes#fairy tale retelling#fairytales#brothers grimm#fairy tale art#fairies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deathless Thoughts:

I only read this book in full once in 2017 and have only really paged through it a lot since. I definitely found it much more deliberate and thematically coherent this time around. I remember initially feeling like the surrealism and constant jumps ahead were disjointed but it reads very cohesively to me now. I’m very curious if that will continue past the latter 50% which I haven’t reread yet. I remember starkly disliking that portion and I have no idea if I’ll feel similarly this time around— because I already enjoyed the second act much more on reread and acknowledged its purpose, when up until now I did not lol

My initial thoughts were that the fantasy elements were too surreal to care about and that the relationship was too much of a nothing, with too little not unpleasant screen time to justify its centrality to the plot. But having read more classic surrealist Russian lit has familiarized me to the former and makes me actually understand what it’s going for. And for the latter I think I’m just more onboard with unpleasantness and abuse being the point. So currently, my perspective is almost wholly positive.

I enjoy the book’s use of its subject material— fairytales set in actual history— as many many metaphors. First folktales and fantasy specifically in the Soviet era, so rife with censorship, as a vehicle for allegory, their use and importance in literature itself being a motif. Then the metaphor for inexorable class hierarchies and unchangeable power structures before and after the revolution, the way only the branding changed, but the power structures remained. And also, most pervasively, as a way to examine gender roles and gendered loss of agency; the politics of a marriage.

I really liked the way the novel built up Koschei and how everything is about Marya’s relationship with Koschei (her relationship with agency and the lack thereof) even when he’s fairly infrequently on screen. From her sister’s bird husbands in the opening, and child Marya’s musing on the potential transformative nature of marriage— but also the inherently unequal power dynamic and resolving that she will do/be better because she knows more than they did. To the metaphor of her thinking that a secret will treat her well and then later the line where the personified secret is then likened to a husband who will be her ruin. Even that when Koschei finally shows up to take her away it’s compared to being taken away by the revolutionary government/the police.

Marya is herself highlighted for her knowledge and her desire for it. Specifically the ability to see discrepancies in the stories she is told whether that is the magical or ideological and political. The sisters in the opening marry into seemingly static unmoving snapshots of history. Meanwhile Marya’s singled out in her precociousness and open admittance of there being anything completely beyond the ideologies presented by each suitor in his human form [the power structure of the Tsarist state, and the Soviet Union]. She’s defined by wanting to see beyond dichotomies and limited scopes of propaganda. She sees it as a skill, and it is, but it’s also something that singles her out for misery, both by her peers (the scarf incident) and by the likes of Koschei who is specifically drawn to willfulness and a lack of adherence to a particular role with the intent of breaking that will.

The entire seduction segment that is turning all the food and her illness into an erotic power exchange is also just explicitly about breaking her will, and fostering perfect obedience and dependence on him. It’s also really interesting that, in going with him, she does somewhat lucidly give up and trade away her agency/ability to dictate a story/her own perspective in exchange for being physically well cared for. (But then even that is very thorny and with many strings attached)

So by part two, she is stuck in the dichotomy of “who is to rule” and either she can be a Yelena/Vasalisa or a soon-to-be Baba Yaga. Yet, either way, she is never good enough and it is still inevitably an exploitative and draining situation.

Marya being successful in her willingness to do degrading and cruel things to earn Baba Yaga’s blessing and Koschei’s favor being punctuated by all her friends— who without which she would never have succeeded at all— dying horribly illustrates that so well. In her success she is only further isolated. She will never repay their help, because being Tsaritsa of Buyan, and having any sort of power, is inherently antithetical to that.

The emphasis on Lebedeva’s girlboss magic makeup and the passage about Marya being told that girls must care only for vapid, pretty things, among other moments, might feel extremely dated. But I do think they’re intended to be employed in a way where traditional femininity presents a sort of deliberate and acknowledged safety? And it goes hand in hand with Marya, while never choosing to be a “Yelena” in traditional soft femininity, does end up choosing to try to leverage soft power and soft manipulation within deliberately gendered terms fairly often. But again it’s just presented from a very dated and particular context.

So far, the sheer dedication of the book to being an explicit Bluebeard tale and a story about abuse, and how there is no winning in that sort of relationship has been very fun for me.

I also enjoyed Koschei outright lying about the Yelenas and Vasalisas— and then later about the location of his death. I think that’s a character type you usually expect to deceive via omission but, no, he just outright lies a lot.

Another example is that Widow Likho’s book makes it clear that humans best enter into Buyan when ill, and meanwhile everything Koschei does is of course explicitly a repetition of previous stories. So it’s practically confirmed that he had taken every Yelena etc on that same long trip and made them ill on purpose. Even though in the moment he claims to be surprised by it, and spontaneous in caring for her through her illness.

Or the suggestion that he found a reason to put all the other girls in the stable when they got to Buyan as punishment for disobeying him. That the point is the punishment and breaking of the will rather than there being any sort of standard the bride could realistically meet where he would be happy with her and welcome her to her new home without that initial humiliation and fear.

It’s also incredibly funny and refreshing that this book buys into Koschei’s nonsense way less than any of its subsequent imitators. (The Grisha trilogy included!) I enjoyed Baba Yaga being like “Why is everything black, stop being dramatic 🙄”

He’s barely present in the book at all. His page count is truly negligible! And it’s great!

Like I mention earlier, that was actually something I was annoyed by on my first read, the relationship just seemed fairly thin, even though the snapshots of it that we get are fascinating. But after being inundated with so many books worshipping the ground love interests like him stand on, I love how much he doesn’t fucking matter and how little page time he has. How that itself allows Marya’s emotions and conflicted feelings to remain central. The narrative doesn’t care about him, it’s only what impact he has on her that’s relevant.

Anyway somewhat superficial but I really enjoy the goth love interest being the Tsar of Life, because authors typically go a more obvious and melodramatic route. Despite all of the goth mystique, him not being associated with death, darkness, night, etc was refreshing. But also I do generally just find the concept of life being equated with the lurid and demanding, the parasitical, something that is always in a personal sense at war with death— aka the mention of him always looking sickly or feeling skeletal initially when he kisses Marya— a compelling one. It’s death and the maiden wrapped up in a single person essentially.

Anyway I also appreciated the parallel of the Yelenas being trapped in eternity weaving soldiers while Marya’s first thought upon seeing Koschei is that if she had knitted herself a perfect lover he would look like that. There is the constant underpinning of Marya being wholly separate from them, the question of whether she is greater or more horrible than them, but at the heart of it she’s really not. She’s just another victim in a long string of them.

#cautiously hopeful that I’ll like the second half just as much despite my opinions on first read#deathless#koschei the deathless#marya morevna#book talk#*writer’s cap*#dark stories of the north

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

***

A while ago, I wrote about how Dracula in the modern world asks Zoe (actually, Agatha) on a date using Tinder language. That this was a kind of declaration of love after one hundred and twenty years.

But, like everything in this complex text, this situation has several layers.

Let's remember what it was built around. Why is Dracula writing this letter and what does he want Zoe to do?

He invites her to drink his blood if she wants to match him – that, in fact, means she should if she wants to get to know him better and make contact with him.

This is a very ancient fairy tale motif, which we see at the very beginning of the film, when Jonathan, having arrived at Dracula's castle, begins with dinner. I wrote in the essay about the mythological and fairy-tale imagery in Dracula that this is how the motif of involvement is realized when the hero finds himself in the space of myth and a magical forest. In the language of the tale, this means that if Jonathan had not tasted the food and wine in Dracula's house, then nothing that happened next would have happened. Moreover, I suspect that the close connection between Dracula and Jonathan, which allowed the Count to be changed by the influence of his victim, is based in no small part on this ‘common space’ created by them both, which arose when they first shared a meal.

Here we can step back from the main topic for a moment and ask a question.

It is obvious that Dracula lured various people to the castle in one way or another many times and drank their blood. But how many of them did he eat with? I could be wrong, but I have a strong feeling that Jonathan's appearance was Dracula's first attempt to ‘do it right’ – that is, to start, like all normal people, with courtship. But, as we know, first love is not always mutual. Especially if you are a teenager who cannot control yourself.

But let's return to Zoe and Agatha. The vampire canon has existed for more than a hundred years, and blood as a part of it has long turned into an inherent banality in the eyes of the reader and viewer. But Moffat and Gatiss return the original fairytale meaning to the story and its images, and the blood becomes a bridge, crossing which the characters can hear each other, and thanks to what they hear, change.

Dracula offers Zoe-Agatha a very bold and very intimate thing – he literally invites her to penetrate him, learn his secrets, and accept him. And paradoxically, this allows her to recognize herself, becoming whole. And as a result, it turns out that what Dracula longed for hundreds of years – to find a partner – does not require complex experiments with the vampire breed, but ordinary openness and a willingness to give oneself to another.

This is a coming-of-age story, no matter how you look at it. And, unlike similar stories, references to which are scattered throughout the text, it is very clear and healthy. Here I can't help but remember once again that Steven Moffat is a former school teacher. For him, good is always good, and evil is evil. Moffat has no ‘misunderstood’ negative characters. Therefore, Dracula is not a story about a vampire through the eyes of a vampire who has his own truth. No. It is about a person who goes through a long labyrinth, experiences a transformation, and becomes himself. In life, in love, in partnership. And it ends up at the top. Literally, in the culmination and realization of all that he is.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

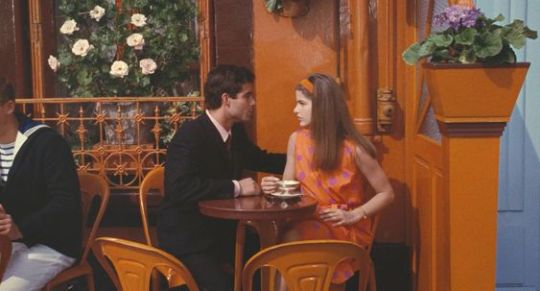

Viewing Response 6: The Convergent Narratives of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

In The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, director Jacques Demy subverts the tropes and structures of the fairytale genre (and, by extension, the classic American film conventions) by infusing the film with melodrama. Through textual and cinematic elements alike, Demy is able to expertly create a poignant, raw, elevated picture of a relationship torn apart. Through plotting and storytelling, Demy transforms the story of young lovers Jacqueline and Guy into a painful tale of love lost. This decision to play with the fairytale-esque narrative creates the power inherent in the film.

As Anne Duggan explains in “Fairy Tale and Melodrama: Lola and the Umbrellas of Cherbourg”, the template for storytelling as repeated by the most popular Hollywood films of the early twentieth century was that of a Disney fairytale. The textual mosaic of these stories always results in the same final point: a female character waiting to be saved by a handsome prince. In this style of story, the female character’s passivity is rewarded by material wealth and domesticity. Duggan writes that the happy ending of the fairytale, “is about the reestablishment of heteronormative and patriarchal order, in which virtue is properly rewarded and vice – incarnated by unruly women – is punished” (16). In the fairytale, the male figure has been cemented within the narrative and the life of the princess. This storytelling structure ingrains social pressures concerning heteronormativity and the familial unit, painting it as the ideal.

The melodrama is a style of story which refers to similar themes but is altogether different in its narrative approach. Duggan explains that the melodrama, “is about what gets repressed or marginalized in the process of adhering to gender, social, and sexual norms” (17). It is a play on the fairytale in that it explores what might happen if the prince could not save the princess.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg appeals to both of these influences in its exploration of the relationship and social pressure. Genevieve is encouraged, through the use of fairytale allusions, to accept the rescue of a prince in Roland. However, the structural makeup of the film implies that Genevieve is waiting to be saved by her prince in Guy. It is from this convergent narrative boundary that Demy finds the film’s melodrama. As the fairytale narrative of the wealthy Roland saving Genevieve subducts the Guy-Genevieve fairytale narrative beneath it, the sense of repression which fuels melodrama is produced. Through this clash of narratives, Demy is able to create a heartbreaking and thoughtful portrait of a love story that was lost to societal pressures.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fairy Tale Chic: Elevate Your Wedding Look with a Stunning Ball Gown Dress

Introduction

For brides seeking a touch of enchantment and a fairytale-inspired wedding, the ball gown dress emerges as an exquisite choice. Reminiscent of timeless elegance and regal charm, the ball gown silhouette captivates with its voluminous skirt and fitted bodice. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the allure of fairy tale chic, delving into the key features, fabric choices, styling possibilities, and the overall impact of choosing a stunning ball gown wedding dress for women for your special day.

The Ball Gown Silhouette: A Symphony of Elegance

At the heart of fairy tale chic lies the iconic ball gown silhouette. Characterized by a fitted bodice that cinches at the waist and a voluminous, floor-length skirt that billows into a majestic shape, this style transcends trends, embodying a timeless and regal aesthetic. The ball gown silhouette not only flatters a variety of body types but also adds a sense of grandeur to the overall bridal look, making it the perfect choice for those who wish to feel like royalty on their wedding day.

Fabric Choices: Crafting Dreams in Luxurious Textiles

The magic of a ball gown extends beyond its silhouette to the choice of luxurious fabrics that bring dreams to life. Satin, known for its smooth and lustrous finish, adds a touch of opulence, while tulle creates layers of ethereal volume. Lace detailing, whether delicate or intricate, enhances the gown's romantic allure, contributing to the overall fairy tale chic aesthetic. The selection of fabrics plays a pivotal role in ensuring the gown not only looks stunning but also feels magical against the skin.

Neckline Variations: Framing Elegance

While the ball gown silhouette remains a constant, neckline variations offer brides the opportunity to personalize their fairy tale chic look. The classic sweetheart neckline, with its gentle curve, exudes romance and femininity. Off-the-shoulder or illusion necklines add a modern and alluring touch, infusing contemporary elements into the traditional charm of the ball gown. The neckline serves as a frame for the bride's face, allowing her unique beauty to shine through the enchanting silhouette.

Embellishments and Detailing: Transforming Gowns into Art

To elevate a ball gown from exquisite to extraordinary, attention to embellishments and detailing is paramount. Intricate lace appliqués, delicate beadwork, and embroidery transform the gown into a work of art, telling a story with every stitch. Brides can choose the level of embellishment based on their personal style, from a subtle touch of sparkle to a fully adorned bodice. These details contribute to the gown's unique identity and its role in the bride's fairy tale narrative.

Practicality and Comfort: Ensuring a Graceful Presence

While the allure of a ball gown lies in its grandiosity, practical considerations are equally crucial. Brides should prioritize comfort and ease of movement, ensuring they can navigate different settings with grace and poise. The weight of the fabric, the length of the train, and the overall structure of the gown must be carefully considered to guarantee the bride feels not only stunning but also at ease throughout her magical day.

Styling Possibilities: Accessories and Finishing Touches

The fairy tale chic canvas of a ball gown invites a myriad of styling possibilities through accessories and finishing touches. A cathedral-length veil adds a touch of drama, while a delicate tiara or ornate headpiece complements the regal aesthetic. Statement earrings, a classic necklace, or a sparkling bracelet can enhance the overall look without overshadowing the gown's inherent elegance. Belts or sashes provide an opportunity to personalize the gown, allowing brides to express their individual style.

Conclusion

In the realm of wedding fashion, the ball gown stands as an eternal symbol of fairy tale chic, allowing brides to transcend the ordinary and step into a world of enchantment on their special day. From the classic silhouette to luxurious fabric choices, neckline variations, embellishments, and practical considerations, each element contributes to the creation of a gown that embodies the bride's vision of timeless elegance. As brides-to-be embark on the journey to find their dream dress, the ball gown offers not just a garment but a transformative experience—a chance to embody the magic of a fairy tale and make a grand entrance into the next chapter of life. With every twirl of the voluminous skirt, the bride becomes the protagonist of her own fairy tale, leaving an indelible mark on the hearts of those who witness the enchanting union of love and dreams fulfilled.

0 notes

Text

Touchstarved as Fairytales (sort of)

Kuras= Rapunzel. We’re gonna save him from that damn tower. Something something being blinded juxtaposed with the visual of a thousand eyes. A crown of thorns after the fall. Golden tears. Healing from past wounds and scars through love and hope.

Leander= Snow White. A twisted version of it. You’ve found yourself lost in woods, an unfamiliar hostile place after running from the world you know. You stumble into a safe haven. This kind, heroic, prince-like mage tells you he and his Bloodhounds (hi, dwarves) can help you. Will you trust him? If he offers you the apple, will you take a bite?

Vere= Little Red Riding Hood. He gives me “wolf that leads the hero astray" vibes. Are you going to end up devoured at the end of the story? Will you follow the straight and narrow path to the Senobium or will you follow the wolf right into the woods, wild and dangerous but promising a freedom you’ve never known?

Ais= The Little Mermaid. Find exactly what you are seeking in this unfamiliar world you’ve ventured into or lose everything. Risk letting your body dissolve in the crimson waters, losing your voice to the Groupmind for some vague hope of love and happiness. Because the chance for that is always worth the gamble.

Mhin= Beauty and the Beast. This was the easiest. A curse that’s turned them into a beast. A desperate search for a cure clashing with a desire to remain confined in one’s own fortress, in the familiar. Until a certain stranger ventures in, and makes them see the inherent beauty in change. In transformation, no matter how monstrous it is.

Elyon= Rumpelstiltskin. Gold spun on mottled grey and a tower that does not understand your power but greeds for it — seeks to imprison you for the bounties they foresee. So you make a deal with the devil. He gives you the gold in exchange for pieces of yourself and he might save your life. It’s all an investment. He’s searching for something beyond gold — and you might hold the key to it.

Sen= Sleeping Beauty. Reversed. The curse is that she can never rest. She doesn't sleep. She doesn't dream. Instead, she passes each day as though she’s in a waking slumber, the world grey and dreamless and devoid of meaning. Her mind and body serve only one purpose, to fulfill her goal of revenge. When will she remember what it is to be awake?

#I would like to read some fairytale aus with them#I think that'd be cool#another specific niche that is very self-indulgent but hehehehe!#I love fairytales! I grew up with them and I also love when people put a different spin on them#I don't know why I already think of Elyon as shady#making sketchy deals with sketchy people where he always comes out on top#but I think he'd be a cool rumpelstiltskin. seeing you as an asset and helping you for a price but accidentally falling in love with you.#haha loser#the name would be a metaphor for whatever he's keeping secret because it'd be dangerous for anyone else to know.#names hold power. letting himself be known is letting someone else hold power over him. and that is deadly to him.#touchstarved#touchstarved game#touchstarved kuras#touchstarved leander#touchstarved vere#touchstarved ais#touchstarved mhin#fairytales#fairytale#fairytale au#sort of#my rambles#my ramblings

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been rotating fanfiction as a concept in my head since I reblogged cryptotheism's post the other day. And instead of starting my large perspective drawing due tonight I'll write down some misc. thoughts.

I love fanfiction. And I've been an avid fandom person since middle school. Before I really used Ao3 I was on Fanfic.net learning the citrus scale and woefully unprepared to filter my content. Those were days lmao.

And one thing the sticks in my mind most is that not all fanfiction is a transformative work. But it sure as hell does blur the line.

Y'see a transformative work is a term used when discussing fair use because the tl:dr of it is that it places a work in a new light enough to be considered it's own thing. Think of all the fairytale re-imaginings or reboots that are basically their own thing but with the same characters. (That ladder being harder to produce legitimately because of how our copyright works, but the same concept.)

Fanfiction isn't transformative, not inherently. Most fanfiction is just taking your blorbos and putting them in a scene you want them to be in. It's not creating a fundamentally new story. Most of the time it's just an addition the already existing work, a love (or hate) letter to the art itself.

However, there are times when fanfiction does create its own stories. And here's when the line blurs. Common tropes can be expanded upon enough to develop characters in a new light.

Timeline rewrite aus are where the obvious start is. "What if's" that take the characters on different paths. It's not it's own story technically, it's exploring a path the canon could've taken, but if done right can feel like it's own book.

(Alternate Universes is where the line blurs. Because now you're actively creating a world that is creating this new light where these characters are in. How expansive this new universe's building is dictates how much the line blurs.)

There are companion stories, where knowledge of the main canon enhances the understand but might not be necessary. Oc centered stuff falls here, as does pre-canon fics, and explorations of background stuff where the author saw a character with two lines and decided to build them an entire life.

There are the wildly different aus, where the new world is something incompatible with canon. The obligatory Human!aus fall here when the entire canon being referenced has little to no humans whatsoever. College!aus as well, human or not, because the main canon didn't and could not have room for that sorta coming of age story. Crossovers might be here too, for their ability to merge worlds and make lines that don't exist.

It's funny, because the most transformative fanwork is the one most often criticized within fandom. The au of an au, the reworking a character so theyre unrecognizable from the sources besides maybe a shared name. That is arguably most transformative because of how disconnected it feels from the original.

But truly, I think the main difference between fanfic and transformative work is the intent. When you set out to build a world that retelling of whatever thing in common use with the explicit intent to play with it's characters and themes but to be new, is when you're truly being transformative.

Take all the adaptions of Shakesphere's work. In high school I watched a production of A Midsommer's Night in Jersey. It was so fun. The key difference between adaptations of Shakesphere's work and fanfiction is the intent. It's a retelling, not an addition or a companion or a "what if."

And I think that's what makes it's so blurry. Because when you get deep in your muse and rewrite an existing world or write your own to put the blorbos in, you tread into the territory of that intent even though that's not necessarily where you've started from.

I think we've seen it slightly. It's gone from "Oh X is a ripoff of Y" to "Oh X is just a shameless fanfic of Y" Because if the two versions of X have a different conception being shamed, it's still called out through the act of being a homage/retelling/whatever of Y. And this is where citing your sources and being enthusiastic of your inspirations comes to an important play.

#this is just rambling before class but I feel the sirens call of a thesis while im on my bullshit.#fandom#fanfiction

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel LaRusso: A Queer Feminine Fairytale Analysis Part 1 of 3

Disclaimers and trigger warnings:

1. These fairytales are European, although there’s often overlap in themes globally. I know European fairytales better, which is essentially the reason I’m not going to branch out too far. I opted to also stick to Western movies so as not to narrow things down, but also in particular “waves hand towards all of Ghibli” amongst many others. There’s a reason the guys in Ghibli are so gender.

2. TW for discussions of rape culture and rape fantasies

EDIT: FUCK I’M A GOBLIN CHILD! FORGOT TO PUT A MASSIVE MASSIVE THANK YOU TO @mimsyaf WHO HAS BEEN THE NICEST, KINDEST EDITOR ON THESE THOUGHTS AND CONTRIBUTED SO MUCH TO THEM AND GENERALLY IS A WONDERFUL PERSON!

Part 2

Part 3

1. Introduction

I recently wrote a little thing, which was about Daniel as a fairytale protagonist – specifically one that goes through some of the kinds of transformations that are often associated with female protagonists of fairytales.

I used quotes from Red Riding Hood, Labyrinth, Buffy The Vampire Slayer, and Dracula, which, as an aside – the overlap between fairytales, horror, and fantasy and the ways each of those genres delve into very deep, basic questions of humanity and the world is something that will always make me feral. I will be generally sticking with fairytales though. Also I am very excited about some of those Labyrinth concepts going around!

I’m going to use “feminine” and “masculine” in both gendered (as in relating specifically to people) and non-gendered (as in relating to codes) ways throughout this, depending on context.

To be binary for a moment, because sample-sizes of other genders are low, women are usually able to fall into either feminine or masculine arcs, although sometimes the masculine-coded woman can become a “not like the other girls” stereotype and the feminine-coded woman a shallow cliché – in both cases they’re also under more scrutiny and judgement, so it’s always worth asking “is this character not working for me because of the writing or because I have ingrained biases? (Both?)”

Men don’t often get feminine-coded arcs. Because. Probably a mix of biases and bigotry. But there are some that seem to have slipped beneath the shuttered fence of “Sufficient Narrative Testosterone,” and Daniel LaRusso is one of them.

2. Some Dude Comparisons (Men Doing Manly Action-Hero Things like being trans symbolism and loving your girlfriend… seriously those things are hella manly, I wish we saw more of that onscreen…)

a. Neo

Much like Neo The Matrix, whose journey is filled with transgender subtext and specifically and repeatedly references Alice In Wonderland, Daniel doesn’t go through quite the kind of hero's journey usually associated with Yer Standard Male Hero, especially the type found in the 80s/90s.

Neo is my favourite comparison, because of the purposefulness of his journey as a trans narrative and the use of Alice. But I’m sure there are other non-traditional male heroes out there (but are they trans tho? Please tell me, I want trans action heroes).

Neo “passes” as a socially acceptable man, but online goes by a different name - the name he prefers to be known by - feels like there’s something inherently wrong about the world around him and his body’s place in that society, and then gets taken down the rabbit hole (with his consent, although without really “knowing” what he’s consenting to) to discover that it’s the world that’s wrong - not him. And by accessing this truth he can literally make his body do and become whatever he wants it to.

Yay. (The message of the Matrix is actually that trans people can fly).

Neo is – kind of like Daniel – a strange character for Very Cis Straight Guys to imprint on. He spends most of the first movie unsure about what’s going on, out of his depth, and often getting beaten up. He is compared to Alice several times and at the end he dies. He loses. He has to be woken up with true love’s kiss, in a fun little Sleeping Beauty/Snow White twist. Yes, after that he can fly, but before that he’s getting dead-named and hate-crimed by The Most Obvious Stand-In For Normativity, Agent Smith, and being carried by people far more physically capable than he is (people who also fall outside of normative existence).

Trinity and Neo in The Matrix. The fact that a lot of the time neither of them is gendered is something. Literally brought to life by true love’s kiss.

I’m not about to argue that Daniel LaRusso is purposefully written along these same thought processes, so much as the luck of the way he was written, cast, directed, acted, and costumed all came together in the right way. And this is even more obvious when compared to That Other Underdog Fite Movie That Was By The Same Director as Karate Kid.

b. Rocky

The interesting thing about Rocky is that he is (despite being a male action icon) also not written as a Traditionally Masculine person. Large portions of Rocky – and subsequent Rocky films – are his fear and insecurity about fighting vs his inability to apply his skills to another piece of work and wanting to do right by his girlfriend (and future wife), Adrian. The fighting is most often pushed onto him against his will.

Much like in Karate Kid there is barely any fighting in Rocky I. Most of it is dedicated to how much Rocky loves Adrian and the two of them getting together. The fight is – again like in Karate Kid – a necessary violence, rather than a glorified one (within the plot, obviously watching any movie like this is also partly about the badassness of some element of the violence – whether stamina or the crane kick, it’s all about not backing down against a more powerful opponent).

Rocky is played by Sylvester Stallone. He’s tough, he’s already a fighter (albeit in the movie not a great one yet), he’s taking the fight for cash – so although he’s also soft-spoken and sweet, you’re aware of the fact that he’s got those traits that’d make a male audience go “Hell Yeah, A Man,” or whatever it is a male audience does watching movies like that… cis straight men imprinting on oiled muscle men sure is a strange phenomenon, why do you wanna watch a boxing match? So you can watch toned guys groaning and grappling with each other? Because you want to feel like A Man by allowing yourself to touch the skin of other men?

Apollo and Rocky in Rocky III. This sequence also includes prolonged shots of their crotches as they run. Sylvester Stallone directed this. This was intentional. Bros.

Daniel LaRusso is not built like that. But that doesn’t really have to matter. Being smallish and probably more likely to be described as “pretty” than handsome, and not having a toxic masculine bone in his body does not a feminine archetype make. It just makes a compelling (and pretty) underdog.

c. Daniel

So where does the main difference really lie? Between Rocky and Daniel? Well, Rocky has the plot in his hands – Daniel, largely, does not. Rocky is acting. Daniel is reacting or being pushed into situations by others. Just like our boy Neo. Just like Alice in Wonderland, Cinderella, Snow White – just like some of the women in some contemporary(ish) fairytale films like Buttercup (Princess Bride), Dorothy (Wizard of Oz), or Sarah (Labyrinth).

This isn’t a necessary negative about stories about girls and women, so much as looking at what it is girls and women in fairytales have/don’t have, what they want, and how they’re going to get it. It’s about power (lack of), sexuality (repressed, then liberated), men, and crossing some taboo lines. It’s also about queerness.

3. The Karate Kid Part One: Leaving Home

Daniel LaRusso is a poor, skinny, shortish kid (played by a skinny, shortish twenty-two-year old) who doesn’t fit in after having been taken away from the home he was familiar with against his will. Not every male protagonist in a fairytale leaves of his own will, and not every female protagonist leaves under duress – Red Riding Hood, for example, seems perfectly happy to enter the forest. However generally a hero is “striking out to make his fortune,” and generally a heroine is fleeing or making a bargain or being married off or waiting for help to arrive. She is often stuck (and even Red Riding Hood requires saving at some point).

Daniel then encounters a beautiful, lovely girl on the beach, puts on a red hoodie (red is significant), is beaten up by a large, attractive bully, loses what little clout he may have had with his new friends, and generally has a mostly miserable time until he befriends and is saved by Mr Miyagi. To do a little Cinderella comparison: Miyagi is the fairy godmother who pushes Daniel to go to the ball in disguise as well, and that disguise falls to pieces as he’s running away.

Then Daniel asks for help, Miyagi gets him enrolled in a Karate Tournament, and starts teaching him. Daniel wins the tournament and gets the girl, the end.

While Daniel has chutzpah and is a wonderful character, none of the big events are initiated by him, except for the initial going to the forest/beach (and within all of these events Daniel absolutely makes choices – I’m not saying he’s passive): Lucille takes them to California, Miyagi pushes him to go to the dance, Miyagi again decides to enroll him in the tournament and trains him, and only because Kreese doesn’t allow for any other option, Ali is the one who more often than not approaches Daniel, and even their first encounter is pushed by Daniel’s friends.

Daniel really is at a dance/ball in disguise and receives a flower from a girl who recognises him through said disguise, it’s unbearable! It’s adorable! I get it Ali, I fucking get it!

Daniel’s main journey within this – apart from not getting killed by karate thugs (love u Johnny <3) and kissing Ali – is to learn from Miyagi. He’s not necessarily a full-on feminine fairytale archetype at this point, although there are fun things to pull out of it, mainly in the context of later films and Cobra Kai: the subtext of karate and how that builds throughout all the stories, the red clothes, the themes of obsession, his being targeted by boys whose masculinity is more than a little bit toxic and based on shame… more on all that coming up.

He doesn’t technically get a home until they build him a room at Miyagi’s place, but he definitely leaves the woods at the end of this one, trophy lifted in the air after being handed to him by a tearful Johnny and all.

And then they made a sequel.

4. The Karate Kid Part Two: Not Out Of The Woods Yet

Daniel’s won the competition, Kreese chokes out Johnny for daring to lose and cry, more life-lessons are given (for man without forgiveness in heart…) and Daniel and Ali break-up off-screen, confirming that TKK1 was not really about the girl after all, which, despite Daniel and Kumiko having wonderful chemistry, is also an ongoing theme. Daniel enters the screen in The Most Baby-Blue Outfit seen since Tiana’s dress in Princess and the Frog? Or that dress in Enchanted? Maybe Cinderella’s (technically silver, but later depicted as blue)?

(Sidenote: At everyone who says Sam ought to wear a callback to that suit, you are correct and sexy).

Surprise, Miyagi’s building him a room.

Double-surprise, Miyagi needs to go to Okinawa.

Triple surprise, Daniel reveals he’s going with him, because he’s his son dammit.

The Karate Kid Part Two is maybe the least Daniel-LaRusso-Feminine-Fairytale-Protagonist of the three, because it’s not really his movie. Daniel runs around with Kumiko (aka the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen), continues to be The Best Non-Toxic Boy a middle-aged Okinawan karate master could ask for, lands himself another Built Karate Rival (twice is just a coincidence, right? Right?), and eventually doesn’t die while wearing red again – twice: When Chozen almost strangles him to death at the Miyagi dojo and then during the final fight. The Saving Of The Girl (both the little girl in the storm and Kumiko) actually puts him in a more traditional masculine space than the previous movie did, even if the main theme of the film is about compassion and kindness and by the end, once more the boy whose masculinity is built on rockhard abs and matchsticks is on his knees. Daniel just has that power over big boys. It’s called kick/punch them in the face hard enough that they see stars.

There’s an aside to be made here about how much Daniel really is an observer in other peoples stories in this, although he is the factor that sends both Chozen and Kumiko into completely different directions in life (Chozen and Kumiko main characters when?) Anyway he comes out of it presumably okay, despite being almost killed. Maybe a few therapy sessions and he’ll get over it. Too bad Terry Silver is lurking around the corner…

5. The Karate Kid Part Three: The Big Bad Wolf

Alright people have written Words about the third movie. It’s fascinating. It’s odd. It’s eye-straining. It’s like olives – you’re either fully onboard the madness or it’s too off-putting for you (or you’re like. Eh, don’t see what all the fuss is about either way...). It’s basically a non-consensual secret BDSM relationship between a guy in his thirties (played by a Very Tall twenty-seven year old Thomas Ian Griffith) and a 17/18 year old (played by a shorter twenty-eight year old Ralph Macchio).

Also recently we got more information on Mr. Griffith’s input on the uh… vibes of the film. Apparently it wasn’t just The Sweetness of Ralph Macchio’s face, the screenplay (whatever that amounted to in the first place – release the script!), the soundtrack, the direction to not tone it down under any circumstances, the fact that Macchio categorically refused to play a romance between himself and an actress who was sixteen, no: it was also TIG coming up with fun ways to torture Daniel’s character and suggesting these to the director. Clearly everyone has fun hurting Mr Macchio (including Mr Macchio).

The point is that aaallll of that amounts to that Intense Homoerotic Dubiously-Consented-To D/s subtext that haunts the movie and gives a lot of fun stuff to play with. It’s also a film that – if we’re analysing Daniel along feminine-coded fairytale lines recontextualises his role in this universe.

The Fairytale goes topsy-turvy. Through the looking glass. Enter Big Bad Wolf stage right. Karate is a metaphor for Daniel’s bisexual awakening.

“Oh, when will an attractive man touch me in ways that aren’t about hurting me?” he asks after two movies of being hurt by boys with rippling muscles. “Why do men continue to notice me only to hit me? Do you think wearing red is making me too noticeable? Anyway, Mr Silver looked really good in his gi today.”

Daniel’s diary must be a trip.

#daniel larusso#the karate kid#cobra kai#ck#johnny lawrence#cobra kai meta#my writing#part one of three#some comparisons to matrix and rocky because I love to talk about those#terry silver

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

The bit I can't get over is that the characters are literally fairytales. The story is inspired by fairytales and myth. They're really walloping you over the head with this in V9. Obviously the problem with Jaune is that he's been conflated with the Rusted Knight to the point of not being himself anymore, and there's all ideals and identity stuff wrapped up in there... but like... the notion of R/WBY is that fairytales are real and the consequences are explored therein, it's not resolutely cynical stuff.

I guess in some sense what I'm struggling with is that I take the perspective that storytelling is transformation, and stories that want to interact with this in a conscious way can be frustrating for me to parse. Once you begin to break apart that subconscious and intuitive framework, you may break things you don't fully understand. Perhaps this is why I'm currently dissatisfied. That, too, that the volume isn't over yet, and to be quite frank judging the full thematic intentions of a work is pretty hard to do without even the ending. The ending recontextualises everything.

I mean, I just want Jaune to be okay. I want Jaune to have a beautiful romance with Cinder and I want everyone to live happily ever after. That is the 'hope' I have, and watching characters interact with that idea is... less interesting to me... I want them to wrestle with meaning in their own lives, and doing it so consciously with narrative (even if I ultimately may agree with their conclusions) is sort of inherently silly to me. It's sensitive ground to cover, anyway.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Genesis of a Genre: Part 1

Defining the four key archetypes of Magical Girl characters found in Japanese Magical Girl media.

I feel this wouldn’t be a great body of research without outlining some kind of historical context for the media were talking about! In this mini-series of essays I’ll be going over the first part of my research, which seeks to define the key influences of the Magical Genre, including industry and production influences, and provide an outline for reoccurring archetypes and conventions found in the narratives. This focuses mainly on Japanese Media, but I might do one about the history of western Magical Girl stuff too!

I pose there are four key archetypes for the protagonist (and sometimes supporting characters) of any Magical Girl franchise: The Witch, The Princess, The Warrior and the Idol. Any given Magical Girl may be one or a combination of several; for example Usagi (Sailor Moon) is a combination of the Warrior and Princess while Akko (Little Witch Academia) is the Witch.

Girl Witches and Growing up

Many writer have cited the Witch as the first true Magical Girl Archetype; Sally the Witch and Magical Akko-chan are often regarded as the progenitors of the Genre. Both were published in the notable shoujo magazine Ribon in the 60’s and both were adapted into anime by Toei; Ribon notably also published several of Arina Tenemura’s works, including the Magical girl series Full Moon while Toei is the studio behind Sailor Moon’s anime in the 90’s, as well as creating both the Ojamo Doremi and Pretty Cure franchises in the late 90’s and 2000’s respectively. Sally was influenced by the popular American sit-com Bewitched, but reimagined to focus on an adolescent girl-witch who must keep her identity secret. She was often alone in her quest too, perhaps with a magical pet confidant, unlike future entries where Magical Girls would be a part of a team or have complex relationships to others with powers. There were ideas of destinies or even secret royal birth-rights, but ultimately the protagonist was simply a girl, who was born with magical powers.

These early entries set off the precedent for Magical Girl as a genre being inherently linked to themes of coming of age; the magic of the young characters often being allegorical for childhood innocence and ultimately being abandoned or given up as a part of their growing up. It’s notable at this point in the genre, very few or no women worked in these spaces; both Sally and Akko are written by men. I wonder how the genre may have been different if it was not the case; could these young girls be allowed to grow up magical if a woman wrote their stories? I feel this is a reoccurring theme in so many future works, so stick a pin in that.

In the contemporary sense, while Magical Witches aren’t quite as frequent as they were in at the start of the genre, there are still several shows that carry on the tradition. Ojamo Doremi, while borrowing several features from later warrior/sentai styled shows like Sailor Moon, has the lead characters as girl witches again. Madoka, though stylistically more a Warrior styled show, also alludes to the history of magical girl as a genre with the naming of it’s initial antagonistic characters being “witches” while the leads are “puella magi” or literally maiden witches, though the way it explores these themes is a conversation for another essay. Lastly, Little Witch Academia is the most recent notable example of the pure Magical Girl Witch. The franchise is like a true homecoming for the genre; I could wax on about how it’s a culmination of everything the genre’s gone through in the last 60 years. From it’s allusions to flashy transformation sequences, to it’s shift in focus to friendships between girls, Little Witch Academia is an absolute treat; it’s main character being named Akko undoubtedly a homage to her ancestor of the same name.

Idol Aspirations

As the genre progressed, women were…allowed into the magazine offices. The genre was reinvigorated in the 70’s, and with these new author came a shift in focus. Stories began to take more elements from Shoujo staples, with more focus given to interpersonal relationships and aspirations of the characters coming into place.

The Magical Idol singer is this weird niche specific thing that sort of came from this period of time, though I think she signifies more than her actual appearances across the genre. Authors for the first time wanted to create stories that reflected the goals of its readers- and at the time that meant Idol culture and aspirations of being a singer or celebrity. While contemporary examples of a by-the-book idol character is a bit rare since values have changed over time, she was the first step in magical powers for Magical Girls no longer being a part of a divine destiny or something to grow out of but instead powers being the means for Girls to achieve their goals. Magical Idol singers also often incorporate the characters noticeably aging up when turning into their alter egos, serving a duel purpose of giving younger viewers a sort of aspirational character to live through while also unfortunately allowing the animators to get away with fan servicey shots of the more mature looking character.

The originator of this subgenre would be Magical Angel Creamy Mami, though Mermaid Melody would be an immediate example I’d personally think of for the Idol type character (with a big old additon of the Princess archetype too), a better example would be the aforementioned Full Moon, in which the sickly Mitsuki transforms into a Magical Idol singer to both live her dreams as a singer and to reunite with her childhood love. I’d also argue that series the Utena and Madoka follow along with this influence; in both cases the characters agree to engage with the magic of their worlds to achieve some kind of goal or dream. Still, I feel there’s lots of potential with this kind of outlook in Magical Girl stuff..!! Perhaps in the future we’ll get more magical girls focused on their careers…

Warrior Princesses

I feel throughout this essay, I’ve been noting how the Warrior and Princess archetype often overlap with the other genres, as well as each other. I believe this is because the ancestor of these two defined archetypes is one and the same, and also the series I believe that actually started magical girl as a genre; that being, Osamu Tezuka’s Princess Knight.

Princess Knight, and bare with me on this, is a story about a Princess born with both a “girl” and a “boy” heart. She forsakes her life as a princess to escape some cruel fate that’s in store for her, and masquerades as a prince by using her “boy” heart. While this is an extremely dated view on gender, it immediately gives us three defining features of magical girl as a genre: First, the Princess archetype, which often holds influence from european fairytales and magical destinies; Second, the Warrior Archetype, in which the lead character must don a more traditionally masculine role of protector against some evil power, and lead a double life; and lastly, the introduction of gender roles as a theme into the genre, and the role of femininity and masculinity in the identities of our characters.

All of these tenets are then repeated in both Sailor Moon and Utena decades later, and it’s arguably these two series that carry it forward to influence future franchises. As the major examples of these archetypes are one and the same, it is difficult to parse the two apart, even though they are quite different.

So I’ll try anyway!

I believe the Magical Warrior is defined as a main character or team of characters who are joined by a destiny to fight against some greater evil, while the Magical Princess is defined as a character who is destined to inherit or reclaim a great power linked to a monarchical structure. Both may have themes linked to western fairytales and fantasy, though often Warrior type characters have a wider breadth of influences while Princesses remain closely linked with ideas of fantasy and fairytale royalty.

While Magical Warrior is definitely the most prolific of the archetypes in modern times, arguably overlapping with nearly every storyline, I think Magical Princesses are fewer. For example, Tokyo Mew Mew is a clear cut Magical Warrior story; they girl’s aren’t born with powers (So not witches), they aren’t doing it for a personal goal (so not Idols) and none of them have some divine destiny (not princesses). However it’s a lot more difficult to find a pure Magical Princess story; in Mermaid Melody, but the story overlaps with both Warrior and Idol archetypes. Princess Tutu might be the best example, as it’s a story of retribution deeply linked with elements from european fantasy.

#magical girl#sailor moon#tokyo mew mew#full moon wo sagashite#revolutionary girl utena#pretty cure#little witch academia#mermaid melody#essay#context#princess tutu#princess knight#ojamo doremi#puella magi madoka magica

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you feel upset that Zuko and Katara did not end up together in the show or Bryke’s post-show material, but rather ended up together in "just fan works", remember this:

Many of the greatest fictional stories in history that you have heard of today are actually fan retellings of the story, that through the years have been changed and added on to in various ways, both big and small. Think of how many wonderful, ancient stories, mythologies, and legends we hear of today that would have been lost to time if the fans of those stories did not pass them on through the generations, changing them as they saw fit to better the story, and adding on to them in their own ways that actually improved the story to become better than its original source material, while keeping the great parts of the original source material. That is how the telling and retelling of stories has always worked throughout history. Someone creates a story from a great idea, and that story gets added on to by people who listen to and love that story, and want to make that good story even more epic than it already is. That is how lore is built.

For instance, take mythology. If you think that the stories from Greek/Roman mythology, Hindu mythology, Egyptian mythology, Norse mythology, Indigenous peoples’ mythologies, etc. were all created from one person/source who deemed what was to be included and accepted as part of the lore, and what was not to be included and accepted as part of the lore, you would be wrong. Many people took the stories and myths that they loved— but did not originally create— and they altered those stories in ways they saw fit. They added in their own wisdom. That is where a majority of the mythological stories you hear about today come from: Retellings of stories that have been changed up from their original source in various ways. But you don’t hear people saying, "This story from Greek mythology about Apollo was not created by the original person who created Apollo, so therefore it can not be included as part of the lore of Greek mythology!"

Let’s look at some classical pieces of literature that are transformative works, for instance:

Fans of the Virgil’s classic "the Aeneid" don’t feel bitter that "the Aeneid" was written 800 years after "the Iliad" and "the Odyssey" (the works "the Aeneid" was based off of) were written, and that it was written by Virgil as opposed to Homer (the one who wrote "the Iliad" and "the Odyssey"). Rather, they enjoy the fact that they, and the rest of the world of literature, happily consider "the Aeneid" as a part of the trilogy that even includes "the Iliad" and "the Odyssey" — the very stories it was based off of.

Going back further, fans of Homer’s "the Iliad" and "the Odyssey" aren’t bitter that the stories about the Greek myth characters in "the Odyssey" were written down by Homer, and not written down by the confirmed original creators of those Greek myth characters. Rather, they accept "the Iliad" and "the Odyssey" as an integral part of Greek mythology with no qualms.

Fans of Dante’s "Inferno" don’t feel bitter that "Inferno" is basically a big crossover and author-insert fanfic. Rather, they celebrate just how much "Inferno" impacted Western literature, and how it— for the first time in the history of literature— actually gave a shape to what Hell would be like. A shape that is widely accepted in the world of literature as an integral part of the lore about Hell.

And there’s plenty of other praised classics like those that are actually transformative works. Many pieces of literature that are praised today as "masterpieces", "classics", and "must-reads" are transformative works. Fan works. The same goes to pop culture. I mean, just look at the Disney Princess movies. Almost all of those stories are transformative works of fairytales, folktales, legends, and myths. But no one says that "the Little Mermaid" movie is invalid because it wasn’t written by Hans Christian Andersen, the creator of the story of “the Little Mermaid”