#Synclavier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

New England Digital Corporation // Synclavier I (US, 1978)

via

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moog 3p modular, Synclavier II, Yamaha CS 80, Minimoog, Korg MS-20 and various other instruments at the Deutsches museum

#retro tech#electronic music#music#synths#vintage tech#synth diy#vintage#modular synth#moog synthesizer#yamaha#korg#korg synthesizer#Synclavier

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Synclavier II (1980)

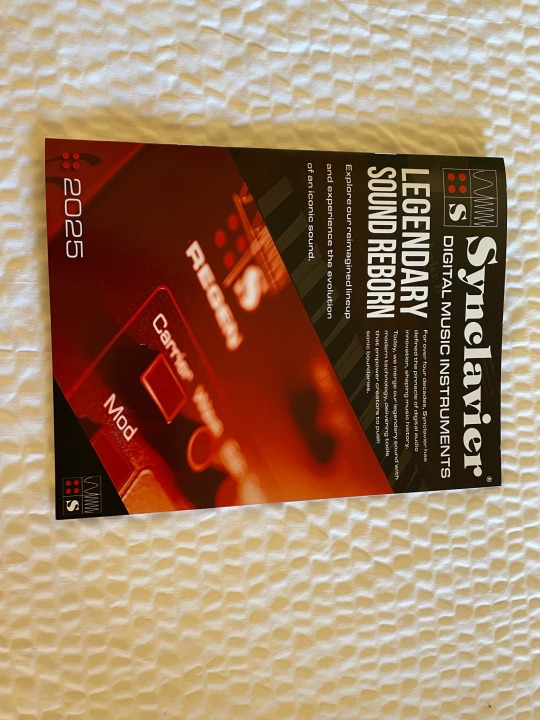

Synclavier returns as Regen, a desktop synth! 👀

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Synclavier Regen Full Demo and Review

0 notes

Text

What a pleasure today working with Fox Quest, Hill Print Solutions, Synclavier and RBIsenberg!

FoxQuestInc.com @foxquestinc

HillPrintSolutions.com

https://www.reddit.com/u/SynclavierMusic/s/H44wozYyuy

https://www.rbisenberg.com/blog/interesting-question-asked-on-our-chat-system-will-mushroom-gummies-cause-a-false-positive-for-a-breathalyzer/ @dwidallas

@randallisenberg-blog

#dallas#lewisvilletx#dallastx#plano#garland#dwi#criminal defense#richardson#synclavier#bulk WiFi#smart homes#smart multi unit property#printing#book publishing#book printing#printing company#lawyer#criminal attorney

0 notes

Photo

BOULEZ CONDUCTS ZAPPA “The perfect Stranger”, originally issued on vinyl in 1984

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Suzanne Ciani - Xenon

Bandcamp HERE

buy track

about

Greg Kmiec’s Xenon pinball machine was released in 1980 and marked a significant milestone in pinball technology and design. The expansion of microchip technology would provide new opportunities for sound designer and synth pioneer Suzanne Ciani, allowing for basic oscillator control and a wider scope for sampling capacity which could facilitate the higher frequencies of a female human voice and entirely reshape the concept of the machine in the process. By using state of the art Synclavier synthesiser technology and an invaluable experience in film scoring and record production Suzanne would devise a complete minimal music score for the machine, then dissect the piece into separate fragments that would be triggered throughout the game play adding an extra creative dimension in player inter-activity (potentially turning the participant into their own musical arranger). By incorporating her own infamous voice box (which had been the focus of a seminal David Letterman Show feature) Suzanne’s combination of a harmoniser and a vocoder also provided the first-ever female identity to a pinball machine which in conjunction with the games ergonomic design and Paul Faris’ figurative graphics (echoing the aesthetic of Rene Laloux and Roland Topor’s La Planète Sauvage) Xenon was able to add a degree of subconscious sensuality to its performance, a feature previously unchartered in arcade development.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

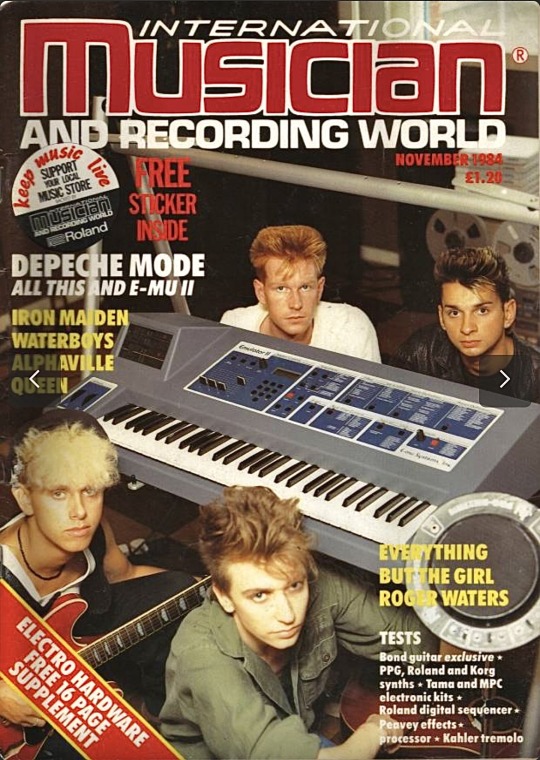

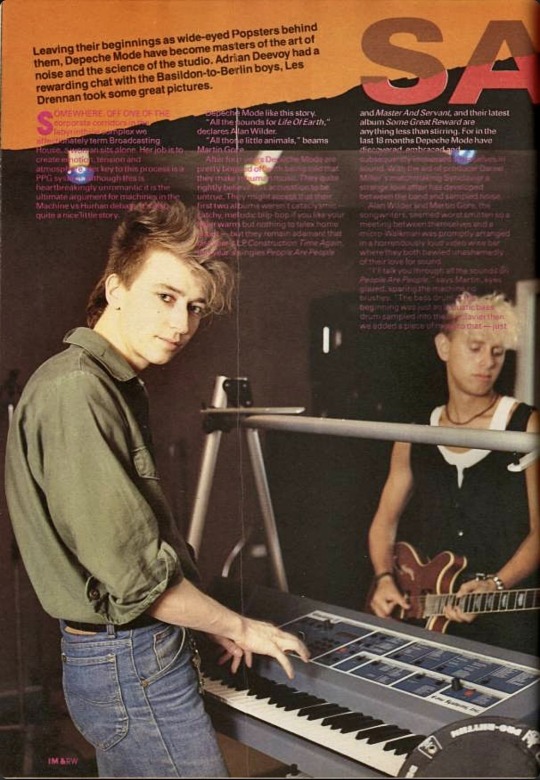

Depeche Mode - Interview with Alan and Martin

International Musician and Recording World - Nov. 1984

Leaving their beginnings as wide-eyed Popsters behind them, Depeche Mode have become masters of the art of noise and the science of the studio. Adrian Deevoy had a rewarding chat with the Basildon-to-Berlin boys, Les Drennan took some great pictures.

Somewhere, off one of the corporate corridors in the labyrinthine complex we affectionately term Broadcasting House, a woman sits alone. Her job is to create emotion, tension and atmosphere. Her key to this process is a PPG system. Although this is heartbreakingly unromantic it is the ultimate argument for machines in the Machine vs Human debate. It’s also quite a nice little story.

Depeche Mode like this story.

“All the sounds for Life Of Earth,” declares Alan Wilder.

“All those little animals,” beams Martin Gore.

After four years Depeche Mode are pretty bogged off with being told that they make inhuman music. They quite rightly believe this accusation to be untrue. They might accept that their first two albums weren’t cataclysmic – catchy, melody blip-bops if you like your lager warm but nothing to telex home about – but they remain adamant that last year’s LP, Construction Time Again, this years singles People Are People and Master And Servant, and their latest album Some Great Reward are anything less than stirring. For in the last 18 months Depeche Mode have discovered, embraced and subsequently immersed themselves in sound. With the aid of producer Daniel Miller’s matchmaking Synclavier a strange love affair has developed between the band and sampled noise.

Alan Wilder and Martin Gore, the songwriters, seemed most smitten to a meeting between themselves, and a micro-Walkman was promptly arranged in a horrendously loud video wine bar where they both bawled unashamedly of their love for sound.

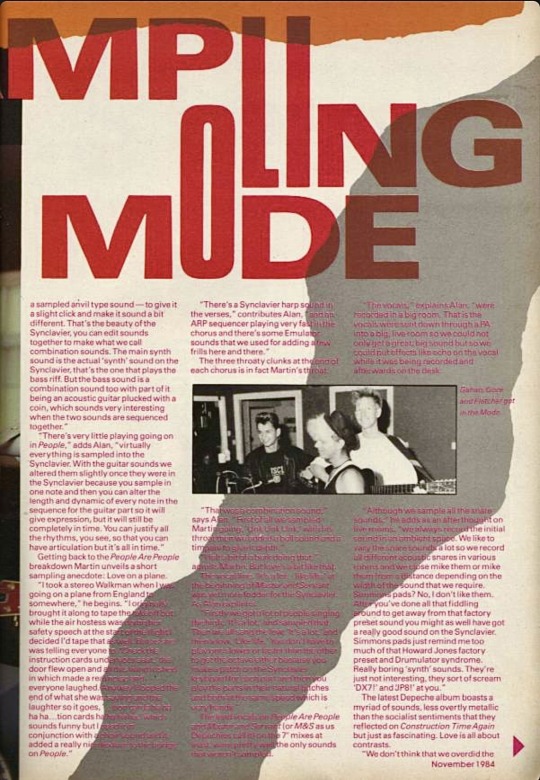

“I’ll take you through all the sounds on People Are People,” says Martin, eyes glazed, sparing the machine no blushes. “The bass drum at the beginning was just an acoustic bass drum sampled into a Synclavier then we added a piece of metal to that – just a sampled anvil type sound – to give it a slight click and make it sound a bit different. That’s the beauty of the Synclavier, you can edit sounds together to make what we call combination sounds. The main synth sound is the actual ‘synth’ sound on the Synclavier, that’s the one that plays the bass riff. But the bass sound is a combination sound too with part of it being an acoustic guitar plucked with a coin, which sounds very interesting when the two sounds are sequenced together.”

“There’s very little playing going on in People,” adds Alan, “virtually everything is sampled into the Synclavier. With the guitar sounds we altered them slightly once they were in the Synclavier because you sample in one note and then you can alter the length and dynamic of every note in the sequence for the guitar part so it will give expression, but it will still be completely in time. You can justify all the rhythms, you see, so that you can have articulation but it’s all in time.”

Getting back to the People Are People breakdown Martin unveils a short sampling anecdote: Love on a plane.

“I took a stereo Walkman when I was going on a plane from England to somewhere,” he begins. “I originally brought it along to take the takeoff but while the air hostess was doing her safety speech at the start of the flight I decided I’d tape that as well. But as she was telling everyone to ‘Check the instruction cards under your seat,’ the door flew open and all this air rushed in which made a real loud noise and everyone laughed. Anyway I looped the end of what she was saying and the laughter so it goes, ‘…tion cards ha ha ha ha …tion cards ha ha ha ha,’ which sounds funny but I used it in conjunction with a choir sound and it added a really nice texture to the bridge on People.”

“There’s a Synclavier harp sound in the verses,” contributes Alan, “and an ARP sequencer playing very fast in the chorus and there’s some Emulator sounds that we used for adding a few frills here and there.”

The three throaty clunks at the end of each chorus is in fact Martin’s throat.

“That was a combination sound,” says Alan. “First of all we sampled Martin going, ‘Unk Unk Unk,’ with his throat then we added a bell sound and a timpani to give it depth.”

“I felt a bit of a berk doing that,” admits Martin. But love’s a bit like that.

The vocal line, “It’s a lot… like life,” at the beginning of Master and Servant was yet more fodder for the Synclavier. As Alan explains.

“Firstly we got a lot of people singing the high, ‘It’s a lot,’ and then a low, ‘Like life.’ You don’t have to play one slower or faster than the other to get the octave either because you make a patch on the Synclavier keyboard for each part and then you play the parts in their natural pitches and both at the same speed which is very handy.”

The lead vocals on People Are People and Master and Servant (or M&S as us Depechies call it) on the 7” mixes at least, were pretty well the only sounds that weren’t sampled.

“The vocals,” explains Alan, “were recorded in a big room. That is the vocals were sent down through a PA into a big, live room so we could not only get a great big sound but so we could put effects on the vocal while it was being recorded and afterwards on the disk.

“Although we sample all the snare sounds,” he adds as an afterthought on live rooms, “we always record the initial sound in an ambient space. We like to vary the snare sounds a lot so we record all different acoustic snares in various rooms and we close mike them or mike them from a distance depending on the width of the sound that we require. Simmons pads? No, I don’t like them. After you’ve done all that fiddling around to get away from that factory preset sound you might as well have got a really good sound on the Synclavier. Simmons pads just remind me too much of that Howard Jones factory preset and Drumulator syndrome. Really boring ‘synth’ sounds. They’re just not interesting, they sort of scream ‘DX7!’ and ‘JP8!’ at you.”

The latest Depeche album boasts a myriad of sounds, less overtly metallic than the socialist sentiments that they reflected on Construction Time Again but just as fascinating. Love is all about contrasts.

“We don’t think that we overdid the metal-beating idea on Construction Time,” says Martin, “but we wanted to make this one less obviously metal sounds. We wanted a little more subtlety…”

So instead of belting skips they belted concrete.

“Yeah, on one of the tracks on the album, Blasphemous Rumours,” elaborates Alan, “we sampled some concrete being hit for what turned out to be the snare sound. All that entailed was us hitting a big lump of concrete with a sampling hammer…”

“…I’m sure they’re not actually called sampling hammers,” interjects Martin giggling.

“Anyway,” continues Alan, “the engineer / producer we use, Gareth Jones, has got this brilliant little recorder called a Stellavox which we use with two stereo mikes and it’s as good as any standard 30ips reel-to-real but this is very small and therefore very portable. So we just took the Stellavox out into the middle of this big, ambient space and miked up the ground and hit it with a big metal hammer. The sound was… like concrete being hit. I can’t really put it any other way.”

“Professional Walkmans are good for sampling too,” claims Martin. “Gareth has always got his out. On trains… at home. They’re good because they get a very impure sound that can often be really interesting. But if we want a very pure sound then we’ll take the thing, say a bit of scaffolding, into the studio and mike it up in the proper conditions and get a clean sound.”

If an equipment list had been included in the mentions on Some Great Reward, apart from pavements, buildings, bottles and old people being stapled together it would have incorporated a long list of toy instruments which Martin divulged as he became more intoxicated; by love of course.

“One morning me and Andy (Fletcher) went down to Hamleys, the toy shop in London, and bought as many toy instruments as we could find. Pianos, saxophones, xylophones and we took them all back to the studio and sampled them. One we used a lot was a Marina (?), a toy one, very strange, but after we’d sampled it, it was great. It sounded pretty terrible as a toy but when we took it down a couple of octaves it sounded really good.”

“People tend to think that if you’re using toy instruments then they have to sound whacky,” complains Alan, “but we put some to very good use because as soon as you sample them they take on a whole new quality and when you transpose them it puts them in a completely new context. Like the noises Martin was making with his throat, we only took those down a tone and it was unrecognisable as someone going, ‘Unk’, with their throat.”

But sampling, like love, isn’t all happiness and although Depeche have learnt to take the rough with the smooth, they found out the hard way. Alan breaks off in the middle of another ‘good combination sound’ story to tell how they were stitched up by a sussed, sampling percussionist.

“We were doing this combination with Martin doing his Indian voice combined with a bassoon type sound.”

“It was pretty ethnic,” says Martin launching into his Indian voice.

Alan ignores him. He has something on his mind that he’s not sure if he should tell us.

“I’m not sure I should tell you this,” he tells us, “but we got this percussionist in for the afternoon to sample his drums and the different techniques of playing them. We didn’t try to hide the fact that we were sampling him. We said, ‘We hope you don’t feel r*ped,’ and he agreed to be sampled literally just hitting one drum, once at a time. Anyway we sampled all his drums once, maybe twice. Now, the Musicians Union haven’t really caught up with sampling and this bloke had obviously contacted them when he got home because he gave us this bill for about 50 different sessions, plus sampling time plus a consultation fee. It was enormous and the stupid thing was that most of the sounds weren’t even as good as that (bangs two pint glasses together) and we only used about two for maybe two seconds each on a couple of songs.”

Another problem came when the band had to divide their recording time between Music Works in England and the 56-track, Solid State luxury of Hansa Mischraum in Berlin.

“There were all these builders in next door at Music Works,” moans Martin, “and we’d have the track running with us hitting skips and concrete and they’d be next door tearing a wall down and we couldn’t tell which was which. It was very confusing at times.”

Like love and marriage, sampling and timing tend to go together like the proverbial horse and jockey.

“Although it makes the whole process even longer, when you get into one you can’t really help but get into the other,” says Alan. “You can’t help, after you’ve been involved with sequencing for a while, noticing three millisecond or five millisecond discrepancies. So you end up time-shifting every sequence until it’s perfect. Then we got into consciously putting things slightly out of time. Like, for example, the choir sound on People again we used a combination sound of different choir sounds on different synths and then put them slightly out of time with each other. Like we took one sound from the Synclavier, one from the PPG and one was on the Emulator. Are you familiar with the Friendchip? It’s a time code reading clock that can monitor every single click output from all your drum machines and all your synths so when everything is going via the Friendchip you can adjust the feel by pulling something, say five or six milliseconds in one direction.

“The thing is so many things can’t play in perfect time anyway,” reveals Alan, “the Linn isn’t in time when it’s meant to be playing ‘drum machine’ perfect time without human error programmed in. It can go out by 20 milliseconds. We set an oscilloscope on several things to see how well they kept time. The one that came out best was the TR808 which only as a two millisecond shift. That’s better than the Synclavier. Rotten sounds though. But we actually ended up triggering stuff from the 808 just because it’s so tight within itself.”

“We always thought the 808 had a good feel,” chips in Martin before adding a bitchy, “even though Alan has a grade eight piano his playing is still incredibly out of time compared to the Synclavier sequencer… and even that’s out!”

All this and the Emulator II?

“Yeah,” admits Martin realising that his love has almost turned him into a technocrat, “the sampling time is about 17 seconds now, I think, and you can get more sampling across the keyboard, it gives better quality than the Fairlight and it only costs about seven grand which is a lot but it will be a big help to us live.”

And there’s a pianillow ballad, Somebody, to be sung love. Martin promises some. Kinda wonderful.

“We’re going to go for a completely human feel on that one. Just a piano played by Alan and Dave singing and Andy playing tapes on the Fostex X15. It’ll be very different.”

So the love for sound can take you backwards but what of the future?

“I don’t know,” confesses Martin, “the Synclavier can already go further than your imagination and they’re thinking of getting new software for that. Then there’s re-synthesis which might happen in a couple of years where you can take a sampled sound and change just tiny parts of it. It’s really impossible to say. Maybe we’ll just get the guitars out and make a Rock ’n’ Roll album. Who knows?”

…and somewhere, within the folds of Auntie Beeb’s ageing skin, a woman sits alone wrestling with a similar emotional predicament. Is she really in love with her PPG system is has it been David Attenborough all along?

Adrian Deevoy, November 1984 (some of the text is hard to read so transcribed to the best of my ability. Apologies for any typos)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spyro Gyra – Breakout

Breakout is the tenth album by Spyro Gyra, released in 1986. Breakout peaked at No. 1 on the Billboard magazine Top Jazz Album chart on September 27, 1986.

Jay Beckenstein – saxophone Tom Schuman – keyboards Julio Fernández – guitar Dave Samuels – vibraphone, marimba, synthesizers Kim Stone – bass Manolo Badrena – percussion Eddie Jobson – Synclavier programming Richie Morales – drums

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neil Young - Razor Love (1984-2020)

Neil Young's "Razor Love" was one of the standout tracks on 2000's Silver & Gold — but the song's origins stretch back to the mid-1980s.

From Jimmy McDonough's Shakey: In January 1984, Young recorded two solo songs with the Synclavier: “Hard Luck Stories” and “Razor Love.” They were the warmest of his techno-pop music, particularly the unrelentingly melancholy “Razor Love,” a piece he spent an unusually long time concocting. “Neil was locked away with that Synclavier for weeks and weeks,” said guitar tech Larry Cragg. “He spent days just working on that one drum pattern.” The obsession paid off. Over mournful, bell-chime keyboard tones, Young sings in a haunted voice of what seems to be a father jettisoning a family. (Was he thinking of his childhood, singing to himself? to Zeke? to someone else? I asked, but he never told me.) Then comes the line that always conjures up a vision of Young alone on his bus, staring out into the blackness of night and seeing only his reflection in the glass: “On the road there’s no place like home / Silhouettes on the window.” Young’s voice cracks on the word “silhouettes” à la “Mellow My Mind.” It was an eerie song, the sort of personalized misery he hadn’t written since Homegrown.

I probably read that passage close to 25 years ago now — but finally (finally!) I got to hear that original "Razor Love" on Archives Vol. III. It didn't disappoint (the rest of Vol. III doesn't disappoint either; you can read my scattered thoughts on some highlights over on Aquarium Drunkard now).

"Razor Love" is an interesting one. It's never become a live standard, exactly, though it was played most nights during the Friends and Relatives tour of 2000. But whenever Neil has brought it out of the barn over the years, it seems to take him someplace special. Whether he's in an arena full of people, on national television or alone in his mountain home, it's like we're eavesdropping on his dreams. As McDonough hints, the song doesn't really offer any easy answers, despite its lullaby melody. Instead, it's a portrait of someone restlessly "trying to find something I can't find yet."

So! Here's a mix of "Razor Love" through the years, from the International Harvesters to Crazy Horse to Promise of the Real. We end up in 2020 with Neil quarantined by the fire, running through the chords, still searching for the song.

Razor Love (Foxboro 1984) / Razor Love (Rotterdam 1989) / Razor Love (San Francisco 1997) / Razor Love (Minneapolis 1999) / Razor Love (NYC 2000) / Razor Love (Antwerp 2003) / Razor Love (Amsterdam 2016) / Razor Love (Telluride 2020)

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Were there any lawsuits over the "sampling" of copyrighted music on the Fallout 1 & 2 soundtracks? Were royalties paid for the samples? I love Mark Morgan's work, but it is rather blatant. Great blog btw!

Hey, thanks for the question and thanks for the compliment! :D

In February 2008, Mark Morgan was asked the following question during an interview on website, Game-OST:

“Timothy Cain said that he likes dark gloomy music and is a big fan of Aphex Twin. Some Fallout compositions are quite similar to work by Aphex Twin - were you influenced by Timothy's tastes?”

Mark Morgan replied with this:

“When Interplay was thinking of using me for the game, they sent over some music that they liked and wanted me to do something similar as a demo. The CD they sent me had no titles or artists’ names, just a few pieces of unidentified music. I gave Interplay what they wanted and I think they must have used some of my demo in the final game. At the time, I wasn’t familiar with the work of Aphex Twin. To me, it was just my interpretation of what Interplay asked for.”

On October 10, 2022, Tim Cain said this in an interview with website, DualShockers:

“I had so much of this music that I gave the list of my music to Mark Morgan and said I wanted the game to sound like this." Included in the list were Brian Eno's Discreet Music, Ambient Works 1 and 2 by Aphex Twin, and a CD called Ambient 4: Isolationism.”

From the information provided above, Mark Morgan was not familiar with Aphex Twin at the time, and he was providing Interplay with what they asked for. We're not aware of any lawsuits regarding the use of any samples, however.

Additionally, in an interview on January 28, 2015 with website The Audio Spotlight, Mark Morgan provided a list of gear that he used during his time on Fallout and Fallout 2:

“At the time I was using a NED Synclavier as my workstation controlling a few midi synths and modules like a Nord 2, Virus, PPG 2.3, Jupiter 6 and a rackmount synth called a Morpheus by EMU. The Morpheus, like a lot of the rackmount modules in the ‘90s, had this little screen with tons of pages to figure out which made programming painful, but once I figured out the programming architecture it yielded some interesting clangy metal sounds and some strange ambiences, which became a big part of the palette and sound of Fallout.”

#fallout wiki#independent fallout wiki#fallout#fallout series#fallout music#mark morgan#music#fallout 2#fallout wiki ask#fallout wiki facts

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the big gaps in my Zappa collection I filled with my recent order from the Record Centre! A 1984 recording of classical music, half by a chamber orchestra directed by Pierre Boulez and the other half by Frank’s divisive Synclavier. All incredible. And one of the few Zappa albums to be released on a label not owned by him—this is an original pressing on the EMI imprint Angel. It was rereleased just a few years later on Barking Pumpkin and has followed his discography to successive new labels.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

How the Synclavier & Cameron Jones Changed Music

#synth#synthesizer#cameronjones#interview#marinelli#synclavier#history#johnappleton#sydneyalonso#newenglanddigital#Youtube

0 notes

Text

In case you are interested or attending NAMM Show!

https://www.g2web.com/2025/01/business-trip-to-california-for-synclavier-at-the-namm-show/

0 notes