#South Lambeth Road

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

287 Kennington Road is where he lived with his father on order of the court for both Sydney (13) and Charlie (9 ), also in the home was his father’s “wife” Louise and her young son (whether he was the son of both Chaplin Sr and Louise is not known). Charlie lived in relative comfort compared to how he lived with his mother Hannah (she at this time was in an asylum). Hannah continually struggled to feed, clothe and provide a home for the boys despite her mental illness and all without benefit of financial support from Charles Chaplin Sr., though he was a successful Music Hall performer he continually refused to support his sons and wife Hannah

Charlie Chaplin notes in his autobiography from 1964: While living with his father and Louise he witnessed both of their alcoholic fueled violence. Louise would lock the boys out of the house at night and took a particular dislike to Sydney, Sydney to avoid Louise was not often there, Charlie was thrilled when a few months later his mother was released and the little family was reunited.

The childhood home that appears to have had the most impact on Charlie was 3 Pownall Terrace, long ago demolished. He tried to recreate the small sparsely furnished home with the slanted ceiling in both “Easy Street” & “The Kid”.

Charlie Chaplin in Lambeth, South London, where he grew up.

He visited his old home, 287 Kennington Road (bottom centre) and The Three Stags (centre), the pub where, as a boy, he saw his father for the last time.

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

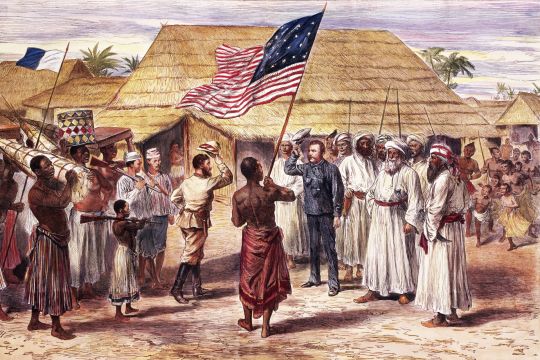

**November 10th 1871 saw the Journalist Henry M Stanley find the missing Scottish missionary David Livingstone with the classic “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”**

In 1867, Henry Stanley became special correspondent for the New York Herald and two years late would be sent to Africa in search of the legendary explorer David Livingstone.

Livingston had been following his obsessional search to find the sources of the Nile River and no one had heard from him for three years.

Stanley got to Zanzibar in 1871 and headed out on a 700 mile trek through tropical rainforest. Because the Herald had not sent the money promised for the expedition he borrowed in from the US Consul. He used this cash to hire over 100 porters for the expedition.

The trip did not go well. During the expedition through the tropical forest, his thoroughbred stallion died within a few days after a bite from a tsetse fly. Many of his porters deserted, and the rest were decimated by tropical diseases.

Seven months after arriving in Zanzibar Stanley found Dr Livingstone near Lake Tanganyika in present-day Tanzania and greeted him with the famous quote: “Doctor Livingstone, I presume?” Or did he?

There is some doubt about whether the line was actually ever said.

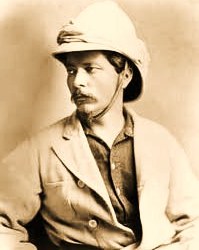

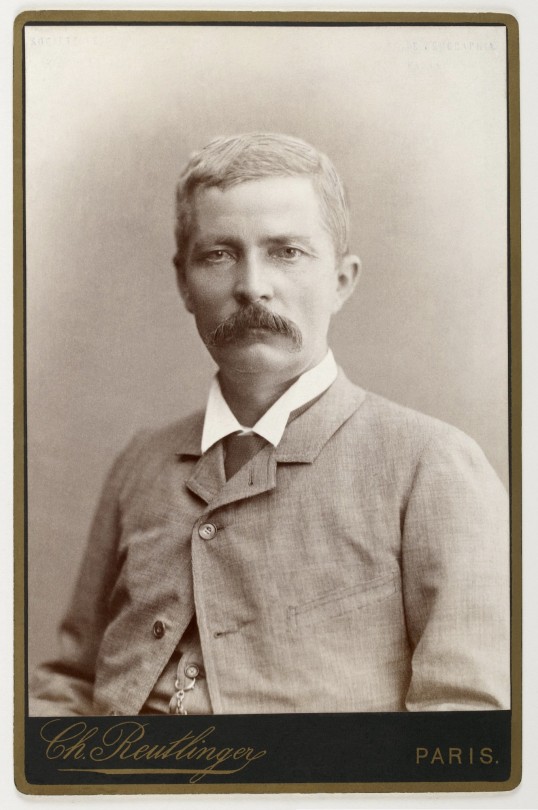

Henry Morton Stanley was born John Rowlands on 28th January 1841 in Denbigh, Wales. His parents were not married, and he was brought up in a workhouse. In 1859, he left for New Orleans. There he was befriended by a merchant, Henry Stanley, whose name he took. Stanley went on to serve on both sides in the American Civil War and then worked as a sailor and journalist.

In 1867, Stanley became special correspondent for the New York Herald. Two years later he was commissioned by the paper to go to Africa and search for the missionary and explorer David Livingstone, of whom little had been heard of for over a year, when he had set off to search for the source of the Nile.

Stanley reached Zanzibar in January 1871 and proceeded to Lake Tanganyika, Livingstone's last known location. There in November 1871 he found the sick explorer, greeting him with the now disputed words: 'Dr Livingstone, I presume?' Stanley's reports on his expedition made his name.

When Livingstone died in 1873, Stanley resolved to continue his exploration of the region, funded by the Herald and a British newspaper.

He explored vast areas of central Africa, and travelled down the length of the Lualaba and Congo Rivers, reaching the Atlantic in August 1877, after an epic journey that he later described in 'Through the Dark Continent'.

Failing to gain British support for his plans to develop the Congo region, Stanley found more success with King Leopold II of Belgium, who was eager to tap Africa's wealth. In 1879, with Leopold's support, Stanley returned to Africa where he worked to open the lower Congo to commerce by the construction of roads. He used brutal means that included the widespread use of forced labour. Competition with French interests in the region helped bring about the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) in which European powers sorted out their competing colonial claims in Africa. Stanley's efforts paved the way for the creation of the Congo Free State, privately owned by Leopold.

In 1890, now back in Europe, Stanley married and then began a worldwide lecture tour. He became member of parliament for Lambeth in south London, serving from 1895 to 1900. He was knighted in 1899. He died in London on 10 May 1904.

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In January 1981 thirteen teenagers died in a firebomb attack on a party in New Cross. The culprits were never found and indifference was the main response on the part of the British establishment. Was it because the youth were black? Was there no sense of shared loss on a national scale because the category of “race” meant that black lives were expendable, that we were extraneous and that black people did not really “belong”? Thirteen dead and nothing said. In March, a Black People’s Day of Action was organized by the Race Today Collective in expression of the community’s outrage and grief, passing en route from South East London to Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, via Fleet Street, in protest at the social construction of reality conveyed by a tabloid point of view that made our lives appear invisible (see Pat Holland, 1981). But when some skirmishes erupted between demonstrators and police, they were blown up and orchestrated into a full-scale moral panic in which lawlessless and looting came to symbolize, all too visibly, the perceived threat of social decay and disorder sedimented in the symbolic association of “race” and crime. This sequence of events precipitated the timing of an intensive, quasimilitarized “saturation policing” initiative (code-named “Operation Swamp”) that was deployed in early April in the borough of Lambeth, or “Brixton,” by now firmly established in popular consciousness, like Belfast, Beirut, or the Bronx, as a code name for nothing but trouble. Through the medium of rumor, a story about a black man brutally arrested on Railton Road, the chain of events that erupted was framed as a crisis of national proportions. Why? Why? Why? screamed one tabloid headline, as if making sense was impossible for the masses of British people without recourse to its narratives of national identity encrusted in collective memory by images of World War II: Black War on Police, The Battle of Brixton, The Blitz of’81.[1] Across bipartisan divisions of left and right, the events were seen as symptoms of a crisis in the very identity of the nation and its people. This emphasis on the inherently unEnglish “otherness” of their irruption in the body politic could be heard in the panic-striken voice of the The Scarman Report, whose official narrative spoke as if the English had suddenly encountered “the unthinkable”...

Kobena Mercer - Welcome to the Jungle: new positions in Black cultural studies (1994:6-7)

#new cross fire#black peoples day of action#black britain#activism#media#anti-blackness#racism#policing

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

This is the shocking moment police found firearms a cowardly gangster hid inside his children’s underwear drawers in south London.

Danny Butler, 44, recklessly stashed six guns, ammunition and drugs at the home he shared with his wife and three daughters, one of whom was just 18-months-old.

Details of Butler’s arrest emerged as figures show nearly half of shootings investigated by the Metropolitan Police go unsolved.

Detectives declared war on underworld armourers bringing death and injury to the capital’s streets.

Sebastiaan James-Kraan, 20, died after being shot by a group of men in Hanwell on June 9.

A nine-year-old girl is still fighting for life following a drive-by shooting in Dalston, one of at least six people injured in four attacks across barely two weeks.

Last year alone, 386 illegal firearms were seized in London – more than one a day.

At Butler’s home in New Park Road, Tulse Hill three handguns, one of which was loaded, were discovered in the girls’ clothes drawer.

Another pistol and a pump action sawn-off shotgun was in their parents’ wardrobe, along with a large amount of ammunition.

A second sawn-off shotgun was found in a coat cupboard.

Further searches uncovered Class B drugs lying on the floor of the living room which were easily accessible to toddler. Police seized Class A drugs kept inside a TV unit and coat cupboard.

On April 22, Butler was jailed for 18 years at Croydon Crown Court for possession of firearms with intent to endanger life and having drugs with intent to supply.

Officers alerted Lambeth social services immediately due to the safeguarding risk presenting the children.

Detective Superintendent Victoria Sullivan described Butlers’ actions as “reckless”, adding: “It’s really sad to see an example of gangs taking advantage of vulnerable people in our communities to store firearms for them.

“Our investigation led to officers removing a dangerous man from our streets, and protecting vulnerable children.

“Significant weapons were found in the house which could have been used to potentially kill or injure others.”

Jackie Taylor’s son Tyrese Miller, 22, was fatally shot in a case of mistaken identity as he returned from an evening at the pub with friends in Croydon in April last year. Two men have been convicted for their roles.

Ms Taylor said: “No mother should have to bury their son like I have.

“What happened to Tyrese has changed all of us. None of us will ever really come to terms with what has happened.

“I worry that if this can happen to Tyrese, it can happen to anyone.

“Once you met Tyrese, you never forgot him. He was loved. He was the centre of our family. He had friends everywhere.

“Sometimes it was easier to say who he didn’t know. For someone that lived such a short life, he meant an incredible amount to so many of us.”

Commander Paul Brogden, who is responsible for the Met’s Specialist Crime, said: “Guns destroy lives and communities.

“The recent shootings in parts of London are a sad reminder that there is still work for us to do when it comes to cracking down on illegal firearms, and my thoughts are with those affected.

“The Met’s sustained work on firearms shows our commitment to making London a safer place.

“We will continue to build trust in the communities disproportionately impacted by these offences and remain relentless in our pursuit of criminals that use and supply firearms.

“Our progress should serve as a message to criminals and gang members using firearms —we will come after you, and we will bring you to justice.”

He added officers are dismantling serious and organised crime groups who pose the greatest harm.

This has led to a 15-year low in firearms offences.

However, the proportion of Met cases that end with an offender facing prosecution has hit 52 per cent, which is the highest rate in 11 years, but leaves 48 percent unsolved.

Detectives believe this is partly due to fear preventing witnesses coming forward or sharing vital evidence including doorbell footage, and the fact that some victims want to get revenge themselves rather than co-operate with the police.

Since March 2023, there has been a reduction from 196 firearms offences in the previous 12 months to 145.

Gun murders have reduced from 12 in 2021, to 10 in 2022 and eight last year.

Across Harrow, Brent and Barnet in west London, there hasn’t been a single fatal shooting since 2020, compared to at least one a year since 2014.

In those boroughs over the last four years, 80 people have been charged with various firearm offences, with 64 of them convicted resulting in a total of 367 years in jail.

Specialist officers achieved a 44 per cent cut in gun crime in Lambeth and Southwark in south east London.

Around half of shootings in the city are believed to be linked to gangs.

Det Supt Sullivan added: “Often the victim themselves who’s been shot do not want to divulge to police and that might be because they’re seeking retribution themselves.

“So potentially today’s victim could be tomorrow’s suspect. And that’s why it’s really important that we act really, really quickly to try and dissolve that situation.”

An increasing number of shootings involve converted blank firearms, originally designed for non-lethal purposes such as bird-scaring, that are converted into deadly weapons.

Around 46 per cent of the 386 weapons seized by the Met last year were converted blank firers.

0 notes

Text

'Items in the time capsule included a piece of lighting equipment signed by Dame Judi Dench, part of the auditorium’s red velvet seats and famous chandelier, signed show programmes and show props, amongst other things representing the Old Vic’s past and present.

A new six storey building for creativity, education and community - to be known as Backstage - is under construction to the south of the 205-year-old theatre builsding

Backstage will include a cafe-workspace, studio theatre, Clore Learning Centre, writers’ room and script library.

Trustee Sheila Atim said: "The Old Vic is a special building and very dear to my heart. Having performed here and supported as a trustee, I am proud of both the onstage work and the theatre’s commitment to sharing joy and enrichment through the arts.

"Their work through free-to-access education and community programmes and emerging talent support reaches 5,000 people a year. The Backstage building offers the chance to house and nurture this work, cementing The Old Vic’s ability to invigorate and inspire - offering theatre for all long into the future."

Laura Stevenson, executive director of The Old Vic, said: "We are delighted to have started work on the Backstage building which will expand The Old Vic by almost a quarter and, crucially, allow us to increase our education and community activities to reach at least double the number of people we reach today.

"This new building will give vital space for developing artists, writers and performers, be a welcoming hub for the local communities of Lambeth and Southwark and give thousands of children and young people the opportunity to come to the theatre, often for the first time.

"We don’t know when – or even if – this time capsule will be opened, but by burying it today, we preserve it as a piece of our history whilst looking ahead to a future where anyone can experience, make and benefit from theatre.’

The Backstage building - designed by architects Haworth Tompkins - is due to open in 2025.'

0 notes

Text

Marble contractor

Website: https://granitelondon.co.uk/

Address: 57 South Lambeth Road, Lambeth, London, SW8 1RH

Phone: +44 0207 793 8804

Granite & Marble UK Ltd is based in Central London. We specialise in bespoke stonework. Kitchen worktops, Vanities, Bathroom tiling, flooring . Decorative stone. We offer a range of beautiful options in Marble, Granite, Quartz, Quartzite, Limestone and Onyx. Visit our yard and speak to one of our specialists to find the right stone for your project.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100077078312379

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/officialgranitelondon/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Home

We are located in Camden, Holborn close to Westminster W1 near Soho, London

Our address is: 8F Gilbert Place, Holborn (next door to Bloomsbury), London, WC1A 2JD. About Camden: Lincoln's Inn Fields is a neighbourhood in the extreme south of the borough that is only 500 metres from the Thames. The northern part of the borough is home to Kentish Town, Hampstead, and Hampstead Heath, which are less populous districts. Numerous parks and open areas may be found in the London Borough of Camden. City of Westminster (near Soho, London) and the City of London are the next-door boroughs, followed by Brent to the west of what was once Roman Watling Street (now the A5 Road), Barnet and Haringey to the north, and Islington to the east. It encompasses all or a portion of the following postcode areas: N1, N6, N7, N19, NW1, NW2, NW3, NW5, NW6, NW8, EC1, WC1, WC2, W1, and W9. The borough of Camden also includes Bloomsbury, known for its garden squares. To the west, the fashionable district of Marylebone is rich in shops and restaurants, while the prestigious Mayfair extends slightly into Camden. Covent Garden, famed for its entertainment and market, adds to Camden's vibrancy. Bordering the east of the borough are Clerkenwell and Farringdon, hubs for the design industry and renowned for their mix of old and new architecture. Although Lambeth and South Bank are located south of the Thames and not within Camden, they contribute to the broader cultural scene that Camden residents can easily access. To the east of Camden, beyond Islington, lies the diverse and bustling borough of Hackney, which provides a distinct cultural blend of its own. Wimpole Street and Harley Street (very close to Camden) are famous for the high number of private health care providers, especially dentists.

Originally published here: https://forestray.dentist/

0 notes

Text

Officer found guilty of assault in Lambeth

Officer found guilty of assault in Lambeth

PC Claudia Pastina, attached to the Central South Basic Command Unit, was given a 16-week sentence, suspended for two years. She was also fined £748. On Saturday, 19 February, PC Pastina and a colleague attended an address on Stockwell Park Road, SW9, following a report of a man acting suspiciously. On arrival, they located the man and asked him to leave the area. He refused to do so and they…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Wait, Layton has a football team? Or is this like that Twilight business? What are you, Team Layton or Team Phoenix?

Anyway, Team Layton is such a funny combination of words. Like, yeah, here's Layton and his bunch of friends. We are Team Layton.

Uh, London. Here we see the Thames river, which crosses the city, on the Elizabeth's Tower side of the river. The square, big building at its side is the Palace of Westminster, which is where the Parliament meets. That central bridge, which connects the road next to the clocktower should be the Westminster Bridge. The whole area is aptly named Westminster, while on the other side is (checks map) Lambeth, South Bank and Southwark. The bottom bridge should be Lambeth Bridge, but I don't know which bridges are the other two. (Checks map frantically) Uh, Hungerford Bridge and Waterloo Bridge?

What bothers me a little is that there's no Westminster Abbey that I can see? It should be a big fucking building right next to the Palace, but all I can see are apartments? Is the Anglican Church not canon to the Layton Universe? Could be. That's probably it, actually, now that I think back to all the games.

#hourly eternal diva#professor layton#all that time i spent studying london for the great ace attorney has finally proved midly useful

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clapham Road, London; 10.6.2019

#dubmill#photography#photographers on tumblr#original photography#original photographers#London#Clapham Road#South Lambeth#Stockwell#South London#England#UK#Britain#London bus#route 333#night#rainy night#2019#10062019

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

London Open House 2021 Highlights

What with Covid, a couple of Septembers spent travelling researching books, a year giving a tour for Tokyo bike and another year opening my own house for London Open House, it's been ages since I actually visited anything myself. This year the festival is bigger than ever, and goes beyond just the weekend with a whole nine days of tours and events.

I've trawled the programme and picked out a few of my highlights

Saturday 11 September Blackheath Quaker Meeting House Architect: Trevor Dannatt A new one to me! Small 1970s concrete Grade II listed building with a raised lantern. Designed to fit in with older buildings in the conservation , and make the most of the split-level site. Book here

Cheeky plug, if you're in Blackheath, why not do my Blackheath Walking Guide to modernist houses—available here).

Sunday 12 September Central Hill Estate Architect: Rosemary Stjernstedt It's been at least 8 years since I visited Central Hill. There were rumours of it being demolished back then, but now it's really under threat. I've no idea (well I do) why Lambeth doesn't value its post-war housing schemes more. Central Hill was designed by Rosemary Stjernstedt for Lambeth Borough in 1963. The tree-lined housing estate on the ridge of Central Hill & Crystal Palace, incorporating open spaces, views over London, gardens and a sense of community. It's definitely worth a visit. Book tickets here for a lunchtime walk here

Saturday 11 and 12 Sunday September Cressingham Gardens Architect: Ted Hollamby Another Lambeth scheme, and another also earmarked for redevelopment, is Ted Hollamby's wonderful Cressingham Gardens. Low-rise high-density estate located next to Brockwell Park. Innovative design with pioneering architectural elements & echoing natural topography. Under threat of demolition by Lambeth council. Tours provided of estate and rotunda.

Events, including walks of the estate and an exhibition, run Saturday and Sunday next weekend. Register here

Saturday 4 September Page High Estate Architect: Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership The what estate? I've not heard of it. It was designed by Dry Halasz Dixon Partnership in 1975. According to the website: Page High is a hidden jewel of post-war London social housing, a 92-home rooftop village in Wood Green. High above the hue and cry of the High Road, Page High (Good Design in Housing award, 1976) is a model for social housing today. The walk is today, and there's only capacity for 10 so we may be too late for this now, but I'm putting it on the list for exploring on another day. More details here Image via the Page High Estate residents association.

Saturday 4 and Saturday 11 September South Norwood Library Architect: Hugh Lea Also under threat of demolition (a bit of a theme here eh?) is the South Norwood Library. The purpose-built library is a fine example of brutalist architecture. Designed by Hugh Lea, Borough Architect for Croydon, in 1968 the main volume shows Miesian influence with an abundance of natural light, interrupted by a concrete cuboid. Open for visits this Saturday and next. Register here

Sunday 5 September Walter Segal Self-build Houses Architect: Walter Segal There's a good book out about Walter Segal which I must buy: Walter Segal Self-built Architect by Alice Grahame and John McKean published by Lund Humphries. Walters Way is a close of 13 self-built houses. Each is unique, built using a method developed by Walter Segal, who led the project in the 1980s. Houses have been extended and renovated. Sustainable features including solar electric, water & space heating. There are several events running on Sunday 5 September. More details here

Saturday 11 and Sunday 12 September Fitzroy Park Allotments If you've done my Fitzroy Park walk, you would have past the allotments, which are ordinally locked and not open to the public. Next weekend is an opportunity to the largest allotment site in the borough of Camden at approximately 3.5 acres. The lower part of the site was acquired by local government after the first world war as a result of requests by local people for the provision of secure growing space. Fitzroy Park Allotments – one of North London's best-kept bucolic secrets – is located on the south-west slopes of Highgate West Hill, alongside the much-cherished and well-known public open space of Hampstead Heath. Register here

(Image by Jim Osley)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

XVI. THE EXODUS FROM LONDON.

So you understand the roaring wave of fear that swept through the greatest city in the world just as Monday was dawning—the stream of flight rising swiftly to a torrent, lashing in a foaming tumult round the railway stations, banked up into a horrible struggle about the shipping in the Thames, and hurrying by every available channel northward and eastward. By ten o’clock the police organisation, and by midday even the railway organisations, were losing coherency, losing shape and efficiency, guttering, softening, running at last in that swift liquefaction of the social body.

All the railway lines north of the Thames and the South-Eastern people at Cannon Street had been warned by midnight on Sunday, and trains were being filled. People were fighting savagely for standing-room in the carriages even at two o’clock. By three, people were being trampled and crushed even in Bishopsgate Street, a couple of hundred yards or more from Liverpool Street station; revolvers were fired, people stabbed, and the policemen who had been sent to direct the traffic, exhausted and infuriated, were breaking the heads of the people they were called out to protect.

And as the day advanced and the engine drivers and stokers refused to return to London, the pressure of the flight drove the people in an ever-thickening multitude away from the stations and along the northward-running roads. By midday a Martian had been seen at Barnes, and a cloud of slowly sinking black vapour drove along the Thames and across the flats of Lambeth, cutting off all escape over the bridges in its sluggish advance. Another bank drove over Ealing, and surrounded a little island of survivors on Castle Hill, alive, but unable to escape.

After a fruitless struggle to get aboard a North-Western train at Chalk Farm—the engines of the trains that had loaded in the goods yard there ploughed through shrieking people, and a dozen stalwart men fought to keep the crowd from crushing the driver against his furnace—my brother emerged upon the Chalk Farm road, dodged across through a hurrying swarm of vehicles, and had the luck to be foremost in the sack of a cycle shop. The front tire of the machine he got was punctured in dragging it through the window, but he got up and off, notwithstanding, with no further injury than a cut wrist. The steep foot of Haverstock Hill was impassable owing to several overturned horses, and my brother struck into Belsize Road.

So he got out of the fury of the panic, and, skirting the Edgware Road, reached Edgware about seven, fasting and wearied, but well ahead of the crowd. Along the road people were standing in the roadway, curious, wondering. He was passed by a number of cyclists, some horsemen, and two motor cars. A mile from Edgware the rim of the wheel broke, and the machine became unridable. He left it by the roadside and trudged through the village. There were shops half opened in the main street of the place, and people crowded on the pavement and in the doorways and windows, staring astonished at this extraordinary procession of fugitives that was beginning. He succeeded in getting some food at an inn.

For a time he remained in Edgware not knowing what next to do. The flying people increased in number. Many of them, like my brother, seemed inclined to loiter in the place. There was no fresh news of the invaders from Mars.

At that time the road was crowded, but as yet far from congested. Most of the fugitives at that hour were mounted on cycles, but there were soon motor cars, hansom cabs, and carriages hurrying along, and the dust hung in heavy clouds along the road to St. Albans.

It was perhaps a vague idea of making his way to Chelmsford, where some friends of his lived, that at last induced my brother to strike into a quiet lane running eastward. Presently he came upon a stile, and, crossing it, followed a footpath northeastward. He passed near several farmhouses and some little places whose names he did not learn. He saw few fugitives until, in a grass lane towards High Barnet, he happened upon two ladies who became his fellow travellers. He came upon them just in time to save them.

He heard their screams, and, hurrying round the corner, saw a couple of men struggling to drag them out of the little pony-chaise in which they had been driving, while a third with difficulty held the frightened pony’s head. One of the ladies, a short woman dressed in white, was simply screaming; the other, a dark, slender figure, slashed at the man who gripped her arm with a whip she held in her disengaged hand.

My brother immediately grasped the situation, shouted, and hurried towards the struggle. One of the men desisted and turned towards him, and my brother, realising from his antagonist’s face that a fight was unavoidable, and being an expert boxer, went into him forthwith and sent him down against the wheel of the chaise.

It was no time for pugilistic chivalry and my brother laid him quiet with a kick, and gripped the collar of the man who pulled at the slender lady’s arm. He heard the clatter of hoofs, the whip stung across his face, a third antagonist struck him between the eyes, and the man he held wrenched himself free and made off down the lane in the direction from which he had come.

Partly stunned, he found himself facing the man who had held the horse’s head, and became aware of the chaise receding from him down the lane, swaying from side to side, and with the women in it looking back. The man before him, a burly rough, tried to close, and he stopped him with a blow in the face. Then, realising that he was deserted, he dodged round and made off down the lane after the chaise, with the sturdy man close behind him, and the fugitive, who had turned now, following remotely.

Suddenly he stumbled and fell; his immediate pursuer went headlong, and he rose to his feet to find himself with a couple of antagonists again. He would have had little chance against them had not the slender lady very pluckily pulled up and returned to his help. It seems she had had a revolver all this time, but it had been under the seat when she and her companion were attacked. She fired at six yards’ distance, narrowly missing my brother. The less courageous of the robbers made off, and his companion followed him, cursing his cowardice. They both stopped in sight down the lane, where the third man lay insensible.

“Take this!” said the slender lady, and she gave my brother her revolver.

“Go back to the chaise,” said my brother, wiping the blood from his split lip.

She turned without a word—they were both panting—and they went back to where the lady in white struggled to hold back the frightened pony.

The robbers had evidently had enough of it. When my brother looked again they were retreating.

“I’ll sit here,” said my brother, “if I may”; and he got upon the empty front seat. The lady looked over her shoulder.

“Give me the reins,” she said, and laid the whip along the pony’s side. In another moment a bend in the road hid the three men from my brother’s eyes.

So, quite unexpectedly, my brother found himself, panting, with a cut mouth, a bruised jaw, and bloodstained knuckles, driving along an unknown lane with these two women.

He learned they were the wife and the younger sister of a surgeon living at Stanmore, who had come in the small hours from a dangerous case at Pinner, and heard at some railway station on his way of the Martian advance. He had hurried home, roused the women—their servant had left them two days before—packed some provisions, put his revolver under the seat—luckily for my brother—and told them to drive on to Edgware, with the idea of getting a train there. He stopped behind to tell the neighbours. He would overtake them, he said, at about half past four in the morning, and now it was nearly nine and they had seen nothing of him. They could not stop in Edgware because of the growing traffic through the place, and so they had come into this side lane.

That was the story they told my brother in fragments when presently they stopped again, nearer to New Barnet. He promised to stay with them, at least until they could determine what to do, or until the missing man arrived, and professed to be an expert shot with the revolver—a weapon strange to him—in order to give them confidence.

They made a sort of encampment by the wayside, and the pony became happy in the hedge. He told them of his own escape out of London, and all that he knew of these Martians and their ways. The sun crept higher in the sky, and after a time their talk died out and gave place to an uneasy state of anticipation. Several wayfarers came along the lane, and of these my brother gathered such news as he could. Every broken answer he had deepened his impression of the great disaster that had come on humanity, deepened his persuasion of the immediate necessity for prosecuting this flight. He urged the matter upon them.

“We have money,” said the slender woman, and hesitated.

Her eyes met my brother’s, and her hesitation ended.

“So have I,” said my brother.

She explained that they had as much as thirty pounds in gold, besides a five-pound note, and suggested that with that they might get upon a train at St. Albans or New Barnet. My brother thought that was hopeless, seeing the fury of the Londoners to crowd upon the trains, and broached his own idea of striking across Essex towards Harwich and thence escaping from the country altogether.

Mrs. Elphinstone—that was the name of the woman in white—would listen to no reasoning, and kept calling upon “George”; but her sister-in-law was astonishingly quiet and deliberate, and at last agreed to my brother’s suggestion. So, designing to cross the Great North Road, they went on towards Barnet, my brother leading the pony to save it as much as possible. As the sun crept up the sky the day became excessively hot, and under foot a thick, whitish sand grew burning and blinding, so that they travelled only very slowly. The hedges were grey with dust. And as they advanced towards Barnet a tumultuous murmuring grew stronger.

They began to meet more people. For the most part these were staring before them, murmuring indistinct questions, jaded, haggard, unclean. One man in evening dress passed them on foot, his eyes on the ground. They heard his voice, and, looking back at him, saw one hand clutched in his hair and the other beating invisible things. His paroxysm of rage over, he went on his way without once looking back.

As my brother’s party went on towards the crossroads to the south of Barnet they saw a woman approaching the road across some fields on their left, carrying a child and with two other children; and then passed a man in dirty black, with a thick stick in one hand and a small portmanteau in the other. Then round the corner of the lane, from between the villas that guarded it at its confluence with the high road, came a little cart drawn by a sweating black pony and driven by a sallow youth in a bowler hat, grey with dust. There were three girls, East End factory girls, and a couple of little children crowded in the cart.

“This’ll tike us rahnd Edgware?” asked the driver, wild-eyed, white-faced; and when my brother told him it would if he turned to the left, he whipped up at once without the formality of thanks.

My brother noticed a pale grey smoke or haze rising among the houses in front of them, and veiling the white façade of a terrace beyond the road that appeared between the backs of the villas. Mrs. Elphinstone suddenly cried out at a number of tongues of smoky red flame leaping up above the houses in front of them against the hot, blue sky. The tumultuous noise resolved itself now into the disorderly mingling of many voices, the gride of many wheels, the creaking of waggons, and the staccato of hoofs. The lane came round sharply not fifty yards from the crossroads.

“Good heavens!” cried Mrs. Elphinstone. “What is this you are driving us into?”

My brother stopped.

For the main road was a boiling stream of people, a torrent of human beings rushing northward, one pressing on another. A great bank of dust, white and luminous in the blaze of the sun, made everything within twenty feet of the ground grey and indistinct and was perpetually renewed by the hurrying feet of a dense crowd of horses and of men and women on foot, and by the wheels of vehicles of every description.

“Way!” my brother heard voices crying. “Make way!”

It was like riding into the smoke of a fire to approach the meeting point of the lane and road; the crowd roared like a fire, and the dust was hot and pungent. And, indeed, a little way up the road a villa was burning and sending rolling masses of black smoke across the road to add to the confusion.

Two men came past them. Then a dirty woman, carrying a heavy bundle and weeping. A lost retriever dog, with hanging tongue, circled dubiously round them, scared and wretched, and fled at my brother’s threat.

So much as they could see of the road Londonward between the houses to the right was a tumultuous stream of dirty, hurrying people, pent in between the villas on either side; the black heads, the crowded forms, grew into distinctness as they rushed towards the corner, hurried past, and merged their individuality again in a receding multitude that was swallowed up at last in a cloud of dust.

“Go on! Go on!” cried the voices. “Way! Way!”

One man’s hands pressed on the back of another. My brother stood at the pony’s head. Irresistibly attracted, he advanced slowly, pace by pace, down the lane.

Edgware had been a scene of confusion, Chalk Farm a riotous tumult, but this was a whole population in movement. It is hard to imagine that host. It had no character of its own. The figures poured out past the corner, and receded with their backs to the group in the lane. Along the margin came those who were on foot threatened by the wheels, stumbling in the ditches, blundering into one another.

The carts and carriages crowded close upon one another, making little way for those swifter and more impatient vehicles that darted forward every now and then when an opportunity showed itself of doing so, sending the people scattering against the fences and gates of the villas.

“Push on!” was the cry. “Push on! They are coming!”

In one cart stood a blind man in the uniform of the Salvation Army, gesticulating with his crooked fingers and bawling, “Eternity! Eternity!” His voice was hoarse and very loud so that my brother could hear him long after he was lost to sight in the dust. Some of the people who crowded in the carts whipped stupidly at their horses and quarrelled with other drivers; some sat motionless, staring at nothing with miserable eyes; some gnawed their hands with thirst, or lay prostrate in the bottoms of their conveyances. The horses’ bits were covered with foam, their eyes bloodshot.

There were cabs, carriages, shop-carts, waggons, beyond counting; a mail cart, a road-cleaner’s cart marked “Vestry of St. Pancras,” a huge timber waggon crowded with roughs. A brewer’s dray rumbled by with its two near wheels splashed with fresh blood.

“Clear the way!” cried the voices. “Clear the way!”

“Eter-nity! Eter-nity!” came echoing down the road.

There were sad, haggard women tramping by, well dressed, with children that cried and stumbled, their dainty clothes smothered in dust, their weary faces smeared with tears. With many of these came men, sometimes helpful, sometimes lowering and savage. Fighting side by side with them pushed some weary street outcast in faded black rags, wide-eyed, loud-voiced, and foul-mouthed. There were sturdy workmen thrusting their way along, wretched, unkempt men, clothed like clerks or shopmen, struggling spasmodically; a wounded soldier my brother noticed, men dressed in the clothes of railway porters, one wretched creature in a nightshirt with a coat thrown over it.

But varied as its composition was, certain things all that host had in common. There were fear and pain on their faces, and fear behind them. A tumult up the road, a quarrel for a place in a waggon, sent the whole host of them quickening their pace; even a man so scared and broken that his knees bent under him was galvanised for a moment into renewed activity. The heat and dust had already been at work upon this multitude. Their skins were dry, their lips black and cracked. They were all thirsty, weary, and footsore. And amid the various cries one heard disputes, reproaches, groans of weariness and fatigue; the voices of most of them were hoarse and weak. Through it all ran a refrain:

“Way! Way! The Martians are coming!”

Few stopped and came aside from that flood. The lane opened slantingly into the main road with a narrow opening, and had a delusive appearance of coming from the direction of London. Yet a kind of eddy of people drove into its mouth; weaklings elbowed out of the stream, who for the most part rested but a moment before plunging into it again. A little way down the lane, with two friends bending over him, lay a man with a bare leg, wrapped about with bloody rags. He was a lucky man to have friends.

A little old man, with a grey military moustache and a filthy black frock coat, limped out and sat down beside the trap, removed his boot—his sock was blood-stained—shook out a pebble, and hobbled on again; and then a little girl of eight or nine, all alone, threw herself under the hedge close by my brother, weeping.

“I can’t go on! I can’t go on!”

My brother woke from his torpor of astonishment and lifted her up, speaking gently to her, and carried her to Miss Elphinstone. So soon as my brother touched her she became quite still, as if frightened.

“Ellen!” shrieked a woman in the crowd, with tears in her voice—“Ellen!” And the child suddenly darted away from my brother, crying “Mother!”

“They are coming,” said a man on horseback, riding past along the lane.

“Out of the way, there!” bawled a coachman, towering high; and my brother saw a closed carriage turning into the lane.

The people crushed back on one another to avoid the horse. My brother pushed the pony and chaise back into the hedge, and the man drove by and stopped at the turn of the way. It was a carriage, with a pole for a pair of horses, but only one was in the traces. My brother saw dimly through the dust that two men lifted out something on a white stretcher and put it gently on the grass beneath the privet hedge.

One of the men came running to my brother.

“Where is there any water?” he said. “He is dying fast, and very thirsty. It is Lord Garrick.”

“Lord Garrick!” said my brother; “the Chief Justice?”

“The water?” he said.

“There may be a tap,” said my brother, “in some of the houses. We have no water. I dare not leave my people.”

The man pushed against the crowd towards the gate of the corner house.

“Go on!” said the people, thrusting at him. “They are coming! Go on!”

Then my brother’s attention was distracted by a bearded, eagle-faced man lugging a small handbag, which split even as my brother’s eyes rested on it and disgorged a mass of sovereigns that seemed to break up into separate coins as it struck the ground. They rolled hither and thither among the struggling feet of men and horses. The man stopped and looked stupidly at the heap, and the shaft of a cab struck his shoulder and sent him reeling. He gave a shriek and dodged back, and a cartwheel shaved him narrowly.

“Way!” cried the men all about him. “Make way!”

So soon as the cab had passed, he flung himself, with both hands open, upon the heap of coins, and began thrusting handfuls in his pocket. A horse rose close upon him, and in another moment, half rising, he had been borne down under the horse’s hoofs.

“Stop!” screamed my brother, and pushing a woman out of his way, tried to clutch the bit of the horse.

Before he could get to it, he heard a scream under the wheels, and saw through the dust the rim passing over the poor wretch’s back. The driver of the cart slashed his whip at my brother, who ran round behind the cart. The multitudinous shouting confused his ears. The man was writhing in the dust among his scattered money, unable to rise, for the wheel had broken his back, and his lower limbs lay limp and dead. My brother stood up and yelled at the next driver, and a man on a black horse came to his assistance.

“Get him out of the road,” said he; and, clutching the man’s collar with his free hand, my brother lugged him sideways. But he still clutched after his money, and regarded my brother fiercely, hammering at his arm with a handful of gold. “Go on! Go on!” shouted angry voices behind. “Way! Way!”

There was a smash as the pole of a carriage crashed into the cart that the man on horseback stopped. My brother looked up, and the man with the gold twisted his head round and bit the wrist that held his collar. There was a concussion, and the black horse came staggering sideways, and the carthorse pushed beside it. A hoof missed my brother’s foot by a hair’s breadth. He released his grip on the fallen man and jumped back. He saw anger change to terror on the face of the poor wretch on the ground, and in a moment he was hidden and my brother was borne backward and carried past the entrance of the lane, and had to fight hard in the torrent to recover it.

He saw Miss Elphinstone covering her eyes, and a little child, with all a child’s want of sympathetic imagination, staring with dilated eyes at a dusty something that lay black and still, ground and crushed under the rolling wheels. “Let us go back!” he shouted, and began turning the pony round. “We cannot cross this—hell,” he said and they went back a hundred yards the way they had come, until the fighting crowd was hidden. As they passed the bend in the lane my brother saw the face of the dying man in the ditch under the privet, deadly white and drawn, and shining with perspiration. The two women sat silent, crouching in their seat and shivering.

Then beyond the bend my brother stopped again. Miss Elphinstone was white and pale, and her sister-in-law sat weeping, too wretched even to call upon “George.” My brother was horrified and perplexed. So soon as they had retreated he realised how urgent and unavoidable it was to attempt this crossing. He turned to Miss Elphinstone, suddenly resolute.

“We must go that way,” he said, and led the pony round again.

For the second time that day this girl proved her quality. To force their way into the torrent of people, my brother plunged into the traffic and held back a cab horse, while she drove the pony across its head. A waggon locked wheels for a moment and ripped a long splinter from the chaise. In another moment they were caught and swept forward by the stream. My brother, with the cabman’s whip marks red across his face and hands, scrambled into the chaise and took the reins from her.

“Point the revolver at the man behind,” he said, giving it to her, “if he presses us too hard. No!—point it at his horse.”

Then he began to look out for a chance of edging to the right across the road. But once in the stream he seemed to lose volition, to become a part of that dusty rout. They swept through Chipping Barnet with the torrent; they were nearly a mile beyond the centre of the town before they had fought across to the opposite side of the way. It was din and confusion indescribable; but in and beyond the town the road forks repeatedly, and this to some extent relieved the stress.

They struck eastward through Hadley, and there on either side of the road, and at another place farther on they came upon a great multitude of people drinking at the stream, some fighting to come at the water. And farther on, from a lull near East Barnet, they saw two trains running slowly one after the other without signal or order—trains swarming with people, with men even among the coals behind the engines—going northward along the Great Northern Railway. My brother supposes they must have filled outside London, for at that time the furious terror of the people had rendered the central termini impossible.

Near this place they halted for the rest of the afternoon, for the violence of the day had already utterly exhausted all three of them. They began to suffer the beginnings of hunger; the night was cold, and none of them dared to sleep. And in the evening many people came hurrying along the road nearby their stopping place, fleeing from unknown dangers before them, and going in the direction from which my brother had come.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🔸 Kennington Gate, South Lambeth, London circa 1855. A toll gate stood at the intersection of Kennington Park and Camberwell New Road. The toll was abolished on 18th November 1865. #victorianchaps #goodolddays #oldphoto #london #vintage #victorian #streetscene #1850s #nostalgia #retro #pastlives #history #england🇬🇧 (at London, United Kingdom) https://www.instagram.com/p/CQV8ERRA2wD/?utm_medium=tumblr

#victorianchaps#goodolddays#oldphoto#london#vintage#victorian#streetscene#1850s#nostalgia#retro#pastlives#history#england🇬🇧

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Catherine Eddowes timeline

1842 – Catherine is born at 20 Merridale Street, Graisley Green, Wolverhampton, West Midlands, to tinplate worker George Eddowes and his wife cook Catherine née Evans (April 14).

1848 – Catherine’s father George and uncle William leave their jobs in Wolverhampton, and with their families they walk to Berdmondsey, in the London borough of Southwark.

1855 – Catherine’s education at St John’s Charity School, Patters Field, Tooley Street, ends.

1855 – When Catherine is 13, her mother Catherine Evans Eddowes dies (October).

1857 – Her father George dies when she’s around 15, and she goes to live with an aunt.

Ca. 1860 – She eventually returns to finish her education at Dowgate Charity School and to care for her aunt in Biston Street, Wolverhampton, and to work as a tinplate stamper, a colour stover and a grainer at the Old Hall Works.

1860/61 – When about eighteen years old, Catherine moves to Birmingham, where she briefly lives with an uncle, shoe maker Thomas Eddowes. She works as a tray polisher for some months before returning to Wolverhampton, where she lives for a time with her grandfather also named Thomas Eddowes. Some months later, she moves to Birmingham again.

1862 – Catherine leaves home at 19 to live with ex-soldier Thomas Conway aka Thoas Quinn.

1862/63 – Catherine and Thomas earn a living around Birmingham and other West Midland towns by selling “Penny Dreadfull”s and Gallows Ballads penned by him.

1863 – Catherine Ann “Annie”, Catherine’s and Thomas’s first child is born atYarmouth Workhouse in Norfolk (April 18).

1865 – The family resides in Wolverhampton, and Thomas is also writing music hall ballads.

1867 – Catherine’s and Thomas’ second child, son Thomas Lawrence, is born (December 8).

1868 – Catherine and Thomas, and their children Annie and Thomas live in Westminster, London.

1871 – The family has settled at 1 Queen Street, Southwark, Catherine works as a laundress.

1873 – Their third child, George, is born at St George’s Workhouse, Mint Street, St Saviour’s (August 15).

1877 – Catherine’s and Thomas’ fourth and last child, Frederick William, is born at the Union Infirmary, Greenwich (February 21).

1877 – Catherine, aged 36 and working as a washerwoman, is convicted at Lambeth of ‘Drunk &c’. She receives a 14 day sentence which she serves in Wandsworth with her infant son Frederick (August 6).

1878 – Laundress Catherine is sentenced at Southwark to 7 days in Wandsworth Prison for being ‘drunk in a thoro'fare’ (August 17).

1881 – The family has moved to 71 Lower George Street, Chelsea, but it appears that their ‘marriage’ breaks up soon after. Thoas takes their sons with him, and Catherine and her daughter Annie go to Spitalfields to live near Catherine’s sister Eliza Gold.

Ca. 1881/82 – Catherine meets Irish jobbing market porter John Kelly. They eventually move in together at Cooney’s common lodging-house at 55 Flower and Dean Street, Spitalfields.

1886 – Catherine’s daughter Annie is bedridden and pays her mother to attend her. That is the last time Annie, aged 21, sees her mother (September).

1888 – Catherine and John go hop picking as every year to Hunton-near-Maidstone, in Kent with their friend Emily Birrell and her common-law husband, but as this season is not good,they come home earlier than expected and split their last sixpence between them; he takes fourpence to pay for a bed in the Cooney’s common lodging-house, and she takes twopence, just enough for her to stay a night at Mile End Casual Ward in the neighbouring parish (September 27).

1888 – Catherine goes at Cooney’s loding house and has breakfast in the kitchen with her common-law husband John Kelly (September 29).

1888 – Catherine is found lying drunk in the road on Aldgate High Street by PC Louis Robinson. She is taken into custody and then to Bishopsgate police station, where she is detained (September 29).

1888 – She is sober enough to leave at 1 a.m. on the morning (September 30).

1888 – Catherine’s mutilated body is found in the south-west corner of Mitre Square in the City of London, she was 46 (September 30).

Your life was difficult and cut short. You were free at last… 🌼

#Catherine Eddowes#Kate Conway#Kate Kelly#victim#victims#timeline#1842#1840s#1848#1850s#1855#1857#1860s#1860#Thomas Conway#1861#1862#Thomas Eddowes#1865#Thomas Quinn#1868#1867#1870s#1871#1873#1877#Wandsworth prison#1878#1880s#1881

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

May be an odd thing to ask, but do you have any idea where any of the new nightclubs are in wdl? I need a DJ for the new DLC mission and I haven't had any luck 😭 can't find any articles talking about it either. Hope you're well btw!

You can actually find a DJ hanging around the front of the pub over Dedsec HQ, same with a First Responder inside near the back exit.

But as for other places, I have see a couple hanging around the “British Theatre” (Pretty sure it’s called the Southbank Centre IRL), which is in the northernmost point of Lambeth, on the stairs leading up to the road separating it and the Southbank Atrium; and the Seam Nightclub in the very south of Islington and Hackey, east of Farringdon Tube Station. You’ll find some out front and some around the back.

And if you’re looking for First Responders, check Hospitals. There’s four in-game, as far as I can tell:

Royal London, Tower Hamlets, South-East of Whitechapel Tube, North-East of Shadwell Tube.

Guy’s Hospital, Southwark, directly South of the Shard

St. Thomas’, Lambeth, west of Lambeth Tube.

Cruciform, Camden, directly East of Blume Tower (BT Tower IRL).

Give it a few laps around each location, sometimes it can take a minute for them to spawn in.

Hope this helps!

8 notes

·

View notes