#Since the Romans invented the alphabet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

You wouldn’t be able to pry dyscalculia child Jason Grace out of my cold dead hands.

#roman numerals#thats all he can do#Same for all the Roman kids#Since the Romans invented the alphabet#There isn’t any reason for them to have dyslexia#Some might saw#They’re better readers than most#But they can’t math#jason grace#heroes of olympus#percy jackon and the olympians#percy jackson#riordanverse#my child <3#pjo fandom#jason grace my child#percy jackson and the olympians#leo valdez

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been a while since I bitched about baby name websites but. just saw a real doozy. Post titled "Russian names on my list" and of course I clicked on it because as a former Russian language and history student I like Russian names and I think in general Slavic names are super under-discussed and underappreciated on English-speaking name forums.

anyway. She's got a long list of names in Cyrillic script and then in roman alphabet transliteration. Legit Russian names like Svetlana, Lyudmila, Inessa, etc. a couple names that are legit russian in origin but extremely unusual like Revmira which is an invented soviet patriotic name that means "world revolution". (Does she know this? The only person I've ever heard of with this name is my Russian professor's mother who was born in the 1920s and I feel like most Russian speakers would find it an extremely weird choice for a modern baby.) But more than half the script are like...names that I don't think have a Russian origin and are extremely uncommon to virtually unheard of in Russia as far as I can tell.

Брисеида (Briseida)

Андромеда (Andromeda)

Пасифая (Pasifaya)

Гермиона (Hermiona)

Элиана (Eliana)

Эдна (Edna)

Софиана (Sofiana)

the first section are all Greek mythology names transliterated into Russian that don't actually seem to have a history of use as first names in Russia and then the second half is just ???? No one in Russia is named Sofiana.

#girl who told you these were russian names.#person who clearly doesn't speak russian: im going to name my baby a communist propaganda name from the 1920s

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

Just came to ask on an issue I've ran into regarding neography.

People in my circle of conlangers/worldbuilders/neographists say that what I do isn't right and is not to be considered neography - here's what I did:

I made over 500 neographies made since the creation of my Reddit account last year, all documented on @thecrazyneographist

And while some of them are seen as cool and all, most are trash bullshit I throw at the wall waiting for something to stick. I literally have diamonds laying under heaps of crap.

I love neographying, this is out of question. But I, despite making a couple WIPs, cannot make a conlang for every script aesthetic I come up with, thus, 90% of my works are just English ciphers (and a devastating part of them are alphabets).

Question:

Am I a valid neographist if most of my creations are nothing more than "children-level ciphers" for English, or not? No matter the answer I will continue making them because that's what I like to do.

Thanks in advance.

Hey, sorry I didn't respond to this sooner, but there are a lot of issues in here, and I wanted to tease them apart, so I can be quite clear on each one.

First, "I am a valid x", where x refers to some sort of artist, is always kind of a sad question to me, because those who ask it are undoubtedly asking it as a result of one kind of gatekeeping or another. For example, fanfic authors who ask "Am I real writer?" are undoubtedly asking it because someone (or several someones) have told them that they're not because all they write is fanfic. There are often a set of assumptions that come with the definition of a given art, such that the belief is if you haven't fulfilled certain criteria, you can't claim to be an artist in that field. For me, I think the definition is rather simpler.

In any artistic field, you qualify as that type of artist if you attempt that type of art. Notice I didn't say finish. This is especially clear for conlangs, as no conlang is finished. If the criteria for being a conlanger is having one finished conlang then there are no conlangers, and there never have been. There's no such thing as a finished conlang. There is such a thing as a finished painting, though, but I don't think you have to have finished a painting to be a painter. You need to be working at, but you don't need to have finished anything.

This doesn't mean that anyone is an anything. For example, to be a novelist, you have to be in the process of writing at least one novel. If all you've ever written is short stories, you're not a novelist. You are a writer, though.

For a neographer (or orthographer or conscriptor or whatever term is in vogue), all you have to do is attempt to create one conscript. That is the only criterion that needs to be satisfied. You've done that in spades, so you are a valid neographer.

Now, when it comes to an invented script, there are a number of elements involved—or that may be involved. They are as follows:

A unique set of glyphs (i.e. letterforms that are crucially different from any other glyphs in any other script—at least partially).

A unique flow (i.e how the glyphs look when lined up to make wordforms).

A specific instantiation or presentation (e.g. the Roman script has a unique set of glyphs and a unique flow, but in presenting a script, Copperlate looks different from Arial, Times, Palatino, Verdana, etc. Each one is a specific presentation or font face or style).

A unique assignment to a set of sounds and/or words/concepts.

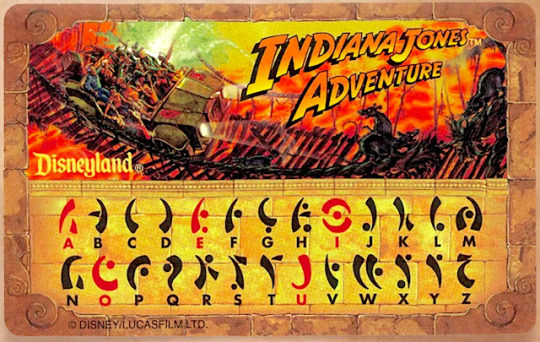

Each of these involve artistic decisions, and they all can be assigned different levels of importance/interest. The fourth bullet above seems to be where unhelpful people in your circle are complaining. That is, one thing to do with a script is assign it to, say, the English version of the Roman alphabet. This is a cipher. Here's an example that's used on the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland:

Let's evaluate this based on the criteria above:

There are a unique set of glyphs—kind of. However, if you kind of stand back and evaluate, you'll see that in fact, every letter is a stylized variant of a letter in the Roman alphabet—with, perhaps, the slight exception of I, which looks like a stylized eye (because this is for Indiana Jones and the Temple of the Forbidden Eye. It's a theme). So, actually, it's not super unique. Additionally, making each vowel glyph red is rather silly.

When written together, the script has a unique flow, but that flow is actually pretty poor. It's a bit like writing in all caps in English, but even all caps Roman has a better balance than this script. It's honestly kind of tiresome looking at this script on the wall. For an alphabet, the characters aren't distinct enough, so it gets poor marks there.

The style of the swooshes/wedges/talons is nice, for the most part (I and U cause me to raise an eyebrow—O, too). The distinction between the very short wedges (as in A, B, and N) and the dots (as in J, L, and M), and the few characters with an even smaller dot (E, X, S, and Y) is, frankly, baffling. Additionally, sometimes the wedges are balanced nicely (A and N are great examples), and sometimes they're way too close (cf. B and Z). While the line work is clean, this honestly even the best version of this style of this script, which is unfortunate, to say the least.

This is a straight-up English cipher. That can only be evaluated based on the goals of the script designer. If the script creator is doing it for fun, then there's nothing to say. That's their choice. If this were done for an Indiana Jones movie or television show, I'd cry foul (cf. Star Wars and their incredibly lazy work). However, this is for a ride. The intended level of interaction for this script is for fans who are standing in line anywhere from 15 minutes to two hours, depending on the time of year and time of day. There are actual messages written in this writing system that fans are supposed to decode. Given the time allotted, I think a cipher—and, in fact, a cipher that can be somewhat easily deciphered—was the right way to go. It's either do a cipher so park goers can actually read the messages without working at it beforehand and have some fun as they're waiting in line, or go all-out stylewise with the expectation that NO rider will ever figure out what's been written.

That's how a script needs to be evaluated. Sometimes purpose overrides style; sometimes not. It totally depends.

It SHOULD go without saying that if you're doing this for your own purposes, then no one can say shit about its intended purpose, or lack thereof. I always thought that in fora like r/neography posters share their script for the look of it, unless they say otherwise. There's both positives and negatives to that. Sometimes the way a script is used makes it cool, so presented without that background renders the script a bit less interesting, but other times, as with your scripts, it should be rather freeing. That is, it doesn't matter if the script is a cipher, is for a conlang, or is asemic: The question is, does it look good? If it does, it shouldn't matter what the hell it's for.

I've looked at your scriptwork here, and I've also seen it on r/neography before. Yes, some of it's a little sloppy, some of it's a little basic (i.e. variation on a theme without thought to how the system as a whole hangs together), and the presentation of some of it could use polishing, but a lot of it is quite interesting, quite striking, and presented quite well. Given the volume of work you've done, it's not surprising that some of it isn't as interesting, but by percentage, your work, on the whole, is outstanding. I honestly never noticed they were ciphers because it's, frankly, totally irrelevant. It'd be like going to an art exhibition and complaining that the titles of all the paintings start with the letter s. lol Like who gives af. That level of criticism is uncalled for and plain silly. Unless someone posts and says, "What do you think about this writing system that I created for a conlang?", I don't see the relevance of commenting on how the script ties to a phonology.

I would also like to take a moment to comment specifically on r/neography. I've frequented there for some time now, and I've seen a lot of good work, but the percentage of good work to bad work (or even relevant work) is extremely low. This is why I say so:

My biggest complaint is there are a metric ton of posts that are Romanization systems or Cyrillicization systems or the like. There is absolutely nothing ne about that ography. I joined that subreddit to see some NEW scripts, not already existing ones assigned to some phonology. There can be interesting discussions about that, sure, and I'm happy to see those types of discussions if I go to a forum specifically for those discussions. A place that purports to be about creating new scripts is not that place—period. If I were a mod, I would ban all of those posts as wholly irrelevant—and yet it is the majority of posts there on any given day.

The presentation of scripts is often abysmal. I mean ABYSMAL. For example, take an English-speaking preschooler writing their name. That's an example of the Roman script. Now imagine presenting that—and only that—as an example of the Roman script, which the viewer has never seen before. What would you say about that? I mean, it looks like garbage. You can't evaluate a writing system if it looks like it's written with one's offhand on a crowded train. And yet that is precisely the type of work that is OFTEN presented there. How can anyone expect to have their script evaluated if the way they present it makes it look like someone tried to handwrite "happy birthday" on a card but started too close to the edge? It's embarrassing—or should be, anyway. I couldn't imagine presenting my own work like that to anyone for critique or showcasing.

The scriptwork itself is often poor. Honestly, there's nothing much to say about this. I rarely comment there, because sometimes the most helpful comment I can think of is, "Maybe creating conscripts isn't for you", which is not a comment worth sharing. Part of it is talent, but part of it is patience and knowing (a) what makes a good glyph, and (b) what makes a good flow for your glyphs. A lot of it is subjective, but "subjective" means that there will be some scripts that 90% of viewers will think is subjectively good; some that 60% will think is "good"; some 20%... So even though it's subjective, it doesn't mean that every single script is equal. There's a lot of room for improvement.

Because of the above, the kind of feedback you get at a place like r/neography is, frankly, suspect, and often not worth the effort it took to type. For my own stuff, I respect the opinions of people whose work I respect. If I don't respect someone's script work, their criticism is worthless. For your own work, I'd recommend you adopt a similar approach.

Finally, I'd like to applaud you for the very last thing you wrote—that you were set to continue whatever I wrote. Because if you enjoy it, you should keep at it. There's no other reason to do it.

Thanks for the ask, and keep it up!

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Constellation: Cygnus, the Goose Bayer, Johann (1572-1625)

Publication date 1655

51 unfolded engraved plates of celestial constellations by Alexander Mair. The very rare fourth edition of Bayer's Uranometria (first published in 1603), the first atlas to cover the entire celestial sphere, in fifty-one star charts, including one containing twelve new constellations unknown to Ptolemy. The illustrations are based on Jacob de Gheyn's designs for the Grotius edition of Aratus, published in Leiden in 1600. Johann Bayer (1572-1625) practised as a lawyer in Augsburg, but his principal interest was in the rapidly developing field of astronomy. His most important innovation was a new system of identifying all stars (prior to the invention of the telescope) by Greek and Roman letters, known today as the Bayer designation. The 1655 edition is much rarer than the 1661 edition" (Milestones of Science Books). "Bayer's was the first accurate star atlas. Earlier star catalogues followed Ptolemy's Almagest in using verbal descriptions to describe the location of stars within the 48 northern constellations of classical astronomy, an awkward system that occasioned constant errors and misapprehensions. Bayer, a lawyer and amateur astronomer, was the first to identify the location of stars within a constellation by the use of Greek letters (with the addition of the Latin alphabet for constellations with more than 24 stars). This simple innovation greatly facilitated the identification of stars with the naked eye, just five or six years before the invention of the telescope, and Bayer's stellar nomenclature is still in use today. Bayer used Brahe's recent observations for the northern sky, and included, in chart 49, twelve new southern constellations observed by the Dutch navigator Pieter Dirckzoon Keyzer and reported by Pedro de Medina. To simplify identification of the stars Bayer included in his typographic descriptions both the traditional star numerations within each constellation and the many names for the constellations employed since Ptolemy (Christies). The Uranometria was reprinted in 1639, 1648, 1655 (this copy) and 1661. Constellations largely identified by cataloger.

Deborah Warner, The sky explored: celestial cartography 1500-1800 pp. 18-19

Found in the David Rumsey Map Collection

#astronomy#astro observations#illustration#stars#star map#map#johann bayer#celestial#david rumsey#archive

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know this isn’t the point but I love this shit

In Latin you have mater, pater, frater, but “sister” (-ter again) is soror, while in Greek ματήρ (matēr), πατήρ (patēr), and θυγάτηρ (thygatēr) for “daughter” but φράτηρ (phratēr) was exclusively used for the member of a φράτρα (phratra), which most generally means “faction” (clan or party) rather than “family,” while ἀδελφός/ἀδελφή (adelphos/adelphē) was used for “brother/sister.” The latter is fun because it’s literally ἁ- (ha-*, equivalent of Latin sim-, “same”) + δελφύς (delphys), “womb,” and the grammatically neutral and diminutive ἀδελφίδιον meant “little/dear sibling,” similar to how the neutral German Mädchen, “girl,” is the diminutive of Magd, “maid.” We call them dolphins from δελφίς (delphis), because their heads with a blowhole like a belly-button look like swollen tummies. This is also the likely source of Δελφοί (Delphoi), “Delphi,” because it was considered the ὀμφαλός (omphalos), “navel,” ie “center,” of the world, a distinction later given to Rome, Rome 2: Constantine’s Revenge, and Jerusalem, specifically the Holy of Holies on the Temple Mount in rabbinical literature, the cornerstone of the creation of the earth. Oh and another fun acronym is PAKiSTan: Pakistan, Afghania, Kashmir, Sindh, BaluchisTan.

*Having lost the rough breathing, ( ̔)/h-, by psilosis, “smoothing,” while the smooth breathing mark, ( ̓), was called ψιλή (psilē). We find this in the names epsilon and upsilon, although the latter’s ability to be aspirated suggests that the distinction indicated by -psilon was between vocalic and consonantal: eta (Η/η) was originally the rough breathing (“heta”), as we use the letter h now, rather than the ē of later Greek, and the digamma (Ϝ/ϝ; its name is from looking like stacked gammas, Γ) stood for /w/, the consonantal form of upsilon (Υ/υ). This is owing to the alphabet’s origin in Phoenician, which had 𐤇 (ḥēt, Hebrew ח) and 𐤄 (hē, Hebrew ה), the latter a “mater lectionis,” that is, a consonant (h, distinct from the harder ḥ, which is often ch in later Hebrew) that may be a vowel, often “ah” at the end of words; meanwhile another Phoenician mater lectionis, 𐤅 (waw, Hebrew ו), became upsilon but in some places also digamma. When the Etruscans adapted the Greek alphabet for their non-Indo-European language, they used 𐌇𐌅 to approximate /f/ before using 𐌚. Presently, the latter sign is considered an Etruscan invention and we understand 𐌅 as /w/ according to the Greek digamma. However, it seems rather likely to me that 𐌚 is a form of beta, Β/β, which was free for the unique but related Etruscan /f/ sound because they did not have /b/. 𐌇𐌅 points to 𐌅 being closer to /v/ than /w/, since 𐌚 was a modified 𐌅, that is, f is like an aspirated v. Latin, whose Roman alphabet was adapted from the Etruscans and the Greeks, had a /b/ and used beta accordingly, but would use V for both upsilon and digamma, so F was free for /f/, like it still is used today.

one of those false etymology posts but with the actual etymology of the word

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Brief Cryptography history: Sending secret messages

Cryptography, from the Greek words for “hidden writing,” encrypts data so only the intended recipient can read it. Most major civilizations have sent secret messages since antiquity. Cryptography history is essential to cybersecurity today. Cryptography protects personal messages, digital signatures, online shopping payment information, and top-secret government data and communications.

Despite its thousands-year history, cryptography and cryptanalysis have advanced greatly in the last 100 years. Along with modern computing in the 19th century, the digital age brought modern cryptography. Mathematicians, computer scientists, and cryptographers developed modern cryptographic techniques and cryptosystems to protect critical user data from hackers, cybercriminals, and prying eyes to establish digital trust.

Most cryptosystems start with plaintext, which is encrypted into ciphertext using one or more encryption keys. The recipient receives this ciphertext. If the ciphertext is intercepted and the encryption algorithm is strong, unauthorized eavesdroppers cannot break the code. The intended recipient can easily decipher the text with the correct decryption key.

Cryptography history and evolution are covered in this article.

Early cryptography dates back to 1900 BC, when non-standard hieroglyphs were carved into a tomb wall in the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

1500 BC: Mesopotamian clay tablets contained enciphered ceramic glaze recipes, or trade secrets.

Spartans used an early transposition cipher to scramble letter orders in military communications in 650 BC. The process involves writing a message on leather wrapped around a hexagonal wooden scytale. When the strip is wound around a correctly sized scytale, the letters form a coherent message; when unwound, it becomes ciphertext. A private key in the scytale system is its size.

100-44 BC: Julius Caesar is credited with using the Caesar Cipher, a substitution cipher that replaces each letter of the plaintext with a different letter by moving a set number of letters forward or backward in the Latin alphabet, to secure Roman army communications. The private key in this symmetric key cryptosystem is the letter transposition steps and direction.

In 800, Arab mathematician Al-Kindi introduced the frequency analysis technique for cipher breaking, a significant advancement in cryptanalysis. Frequency analysis reverse engineer’s private decryption keys using linguistic data like letter frequencies, letter pairings, parts of speech, and sentence construction.

Brute-force attacks, in which codebreakers try many keys to decrypt messages, can be accelerated by frequency analysis. Single-alphabet substitution ciphers are vulnerable to frequency analysis, especially if the private key is short and weak. Al-Kandi also wrote about polyalphabetic cipher cryptanalysis, which replace plaintext with ciphertext from multiple alphabets for security that is less susceptible to frequency analysis.

1467: Leon Battista Alberti, the father of modern cryptography, most clearly explored polyphonic cryptosystems, the middle age’s strongest encryption.

1500: The Vigenère Cipher, published by Giovan Battista Bellaso but misattributed to French cryptologist Blaise de Vigenère, is the 16th century’s most famous polyphonic cipher. Vigenère invented a stronger autokey cipher in 1586, but not the Vigenère Cipher.

In 1913, World War I accelerated the use of cryptography for military communications and cryptanalysis for codebreaking. The Royal Navy won crucial battles after English cryptologists deciphered German telegram codes.

1917: American Edward Hebern invented the first cryptography rotor machine, which automatically scrambled messages using electrical circuitry and typewriter parts. Simply typing a plaintext message into a typewriter would automatically generate a substitution cipher, replacing each letter with a randomized new letter to produce ciphertext. To decipher the ciphertext, manually reverse the circuit rotor and type it back into the Hebern Rotor Machine to produce the plaintext.

1918: German cryptologist Arthur Scherbius invented the Enigma Machine, an advanced version of Hebern’s rotor machine that used rotor circuits to encode and decode plaintext. Before and during WWII, the Germans used the Enigma Machine for top-secret cryptography. Like Hebern’s Rotor Machine, decoding an Enigma message required advanced sharing of machine calibration settings and private keys, which were vulnerable to espionage and led to the Enigma’s downfall.

1939–45: Polish codebreakers fled Poland and joined many famous British mathematicians, including Alan Turing, to crack the German Enigma cryptosystem, a crucial victory for the Allies. Turing founded much of algorithmic computation theory.

1975: IBM block cipher researchers created the Data Encryption Standard (DES), the first cryptosystem certified by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (then the National Bureau of Standards) for US government use. The DES was strong enough to defeat even the strongest 1970s computers, but its short key length makes it insecure for modern applications. Its architecture advanced cryptography.

1976: Whitfield Hellman and Martin Diffie invented the Diffie-Hellman key exchange method for cryptographic key sharing. This enabled asymmetric key encryption. By eliminating the need for a shared private key, public key cryptography algorithms provide even greater privacy. Each user in public key cryptosystems has a private secret key that works with a shared public for security.

1977: Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman introduce the RSA public key cryptosystem, one of the oldest data encryption methods still used today. RSA public keys are created by multiplying large prime numbers, which even the most powerful computers cannot factor without knowing the private key.

2001: The DES was replaced by the more powerful AES encryption algorithm due to computing power improvements. AES is a symmetric cryptosystem like DES, but it uses a longer encryption key that modern hardware cannot crack.

Quantum, post-quantum, and future encryption

Cryptography evolves with technology and more sophisticated cyberattacks. Quantum cryptography, also known as quantum encryption, uses quantum mechanics’ naturally occurring and immutable laws to securely encrypt and transmit data for cybersecurity. Quantum encryption, though still developing, could be unhackable and more secure than previous cryptographic algorithms.

Post-quantum cryptographic (PQC) algorithms use mathematical cryptography to create quantum computer-proof encryption, unlike quantum cryptography, which uses natural laws of physics.

Post-quantum cryptography (also called quantum-resistant or quantum-safe) aims to “develop cryptographic systems that are secure against both quantum and classical computers, and can interoperate with existing communications protocols and networks,” according to NIST.

IBM cryptography helps businesses protect critical data

IBM cryptography solutions ensure crypto agility, quantum safety, governance, and risk compliance with technologies, consulting, systems integration, and managed security services. Asymmetric and symmetric cryptography, hash functions, and more ensure data and mainframe security with end-to-end encryption tailored to your business needs.

Read more on Govindhtech.com

#Cryptographyhistory#Cryptography#postQuantum#Quantum#IBM#IBMcryptography#technews#technology#govindhtech

0 notes

Text

In 1941 an ambitious Philadelphia pediatrician, the wonderfully named Waldo Emerson Nelson, became the editor of America’s leading textbook of pediatrics. For the next half-century the compilation of successive editions of this large volume advanced his career, consumed his weekends, and encroached heavily on his domestic life. Every few years, when a new edition was being prepared for the press, he would dragoon his family into assembling the index for him. He would read through the proofs of all 1,500 or so pages, calling out the words and concepts to be listed, while his wife, Marge, and their three children—Jane, Ann, and Bill—wrote down on index cards the thousands of entries and their corresponding page numbers.

Though Nelson was a brilliant physician, even his most admiring colleagues were struck by his “austere and stern” appearance, his “façade of gruffness,” his “granite conviction of right and wrong.” “Whenever I talk to my residents,” he once proudly recounted about his treatment of junior doctors, “they never know whether to laugh or cry. That’s the way I like it.” So it’s not surprising to find that when his teenage children complained about their indexing duties, he responded by printing the following dedication at the front of the 1950 edition of what became known as the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics:

Recognizing that children, like adults, prosper under the stimulus and responsibility of a task to be done, WE ACKNOWLEDGE the contribution that this book has made to JANE, ANN, AND BILL in providing them such privileges, and the satisfaction in family living which has come from group activity

Nowadays we take for granted that any kind of learned book should be indexed, however tedious the labor. So valuable is this tool, so central to our ways of thinking about and using information, that in the case of multivolume scholarly editions of texts, it’s not uncommon for the index itself to constitute an entire book. Yet in the classical world the concept of such a search aid was unknown. To Cicero, an “index” meant a label affixed to a scroll that indicated its contents, rather like the printed spine or dust jacket of a modern volume on a bookshelf. As Dennis Duncan notes in his clever, sprightly Index, A History of the, the rise of the index in its current form is a story of many interrelated developments, each with its own contingencies and chronology: the replacement of scrolls by the codex, the triumph of alphabetical order, the rise of new pedagogies and genres of learning, the invention of print, the adoption of the page number, and the constantly changing character of reading itself.*

Take alphabetical order. Even though the consonantal alphabet had been around since the early second millenium BCE, the earliest known examples of its application as an organizing principle date only from about the third century BCE. The now lost 120-scroll catalog of the Library of Alexandria listed authors partly in alphabetical order. That the ancient Greeks were fond of using it is evident in everything from their fishmongers’ price lists to records of taxpayers and monuments to playwrights (the background panel of one surviving marble statuette of Euripides lists the titles of his plays from alpha to omega).

Yet after them the Romans largely disdained the alphabetical principle as arbitrary and illogical, and so did Europeans throughout the Middle Ages. Books about words—like lexicons, grammars, and glosses—employed it, but it was not a widely understood rule. As late as 1604 the first printed dictionary of English, Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall, was obliged to begin by explaining that its readers should attend to

the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand…and where euery Letter standeth: as (b) neere the beginning, (n) about the middest, and (t) toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with (ca) looke in the beginning of the letter (c) but if with (cu) then looke toward the end of that letter.

The term “index” didn’t come to be used in its current sense in English until quite recently. There’s no entry for it in Cawdrey, while Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) defined it as “the table of contents to a book.” For centuries words like “table,” “register,” and “rubric” were used interchangeably for what we now call indexes and contents pages: only very gradually, over the past two hundred years or so, have the two forms come to be regarded as essentially distinct. (The related Anglophone convention that indexes appear at the back of books and contents pages at the front seems to have been part of a similar, relatively recent process of separating them.) Nonetheless, names aside, the alphabetical index as a type of textual technology turns out to be much older than that.

There are two basic types, which in modern books are usually combined into a single list. One type collates words, the other concepts. The former is a concordance, the latter a subject index. The first is the kind of literal, specific listing of entries that you can get your computer to produce by using CTRL+F for any word or phrase in a text; the second is the product of a more subjective, humanistic attempt to capture the meanings and resonances of a work. Duncan, understandably, is mainly interested in the evolution of the latter type—even though, because of the rise of the word-based online search engine, we now find ourselves living in a golden age of the concordance. But the two forms need to be treated together, he argues, because both were invented at the same time and place: in northwestern Europe, in or around 1230.

The index was, in fact, part of an entire range of organizational and reading tools that were conceived in the thirteenth century. (Others included the division of the Bible into standard chapters and the genre of distinctiones, a new kind of search aid for preachers that helpfully grouped together biblical extracts on the same subject.) Two social developments at this time created a novel demand for information to be organized in rapidly accessible ways: the foundation of the first European universities and the rise of the new orders of mendicant friars, with their stress on the frequent and engaging preaching of God’s word. In Oxford the scholar and cleric Robert Grosseteste (so named, it was said, because of his gigantic brain) compiled an enormous subject index to the whole of the world’s knowledge, to aid him and his students in navigating it all. His Tabula, of which only a fragment survives, encompassed the entirety of the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, the works of classical authors like Aristotle and Ptolemy, and Islamic authorities including Avicenna and al-Ghazālī.

Meanwhile, in Paris, the Dominican Hugh of Saint-Cher (soon to become the first person ever to be painted wearing reading glasses) oversaw the compilation of an even more stupendous alphabetical word index. This was the first concordance to the Bible, listing over 10,000 of its keywords with all their locations, from the exclamation “A, a, a” (now usually translated as “ah!”) all the way to “Zorobabel,” the sixth-century-BCE governor of Judea.

Soon enough, medieval readers were making their own indexes to volumes they owned. The invention of printing brought further refinements. Page numbers had already been used to number the leaves of individual manuscripts, but the uniformity of printed books gave them a different utility, as a means of referring to the same place across different copies of the same work. It took time for this idea to catch on. The first printed page number was not produced until 1470; even by 1500 only a small minority of books had adopted the practice. Instead, early printed indexes referred to textual locations or to the signature marks at the bottom of pages (“Aa,” “b2,” and the like), which printers and binders used to keep their finished sheets in the correct order. But in the course of the sixteenth century, use of the page number spread, alongside the creation of increasingly sophisticated indexes by scholarly authors.

As early as 1532, Erasmus published an entire book in the form of an index because, he quipped, these days “many people read only them.” A few years later his colleague Conrad Gessner, one of the greatest indexers of his day, rhapsodized about how this new search tool was transforming scholarship:

They are the greatest convenience to scholars, second only to the truly divine invention of printing books by movable type…. Truly it seems to me that, life being so short, indexes to books should be considered as absolutely necessary by those who are engaged in a variety of studies.

Like every widely observed change in reading and learning habits before and since (the invention of writing, the launch of Internet search engines, the spawning of ChatGPT), the spread of the index was accompanied by anxiety that flighty, superficial modes of accessing information were supplanting “proper” habits of reading and understanding. In the sixteenth century Galileo complained that scientists seeking “a knowledge of natural effects, do not betake themselves to ships or crossbows or cannons, but retire into their studies and glance through an index or a table of contents.” To “pretend to understand a Book, by scouting thro’ the Index,” jibed Jonathan Swift in 1704, was the same “as if a Traveller should go about to describe a Palace, when he had seen nothing but the Privy.” Yet as Duncan wisely points out, our intellectual habits are always changing, and for good reason. Every social and technological shift affects how we read—and we also all read in many different ways. Twitter, novels, text messages, newspapers: each demands a different kind of attention. The older we get, the more invested we are in modes of reading that we’re familiar with and the more suspicious of technologies that seem prone to disrupt them.

The eighteenth century produced a great efflorescence of indexing novelties, jokes, and experiments, which Index, A History of the has great fun cataloging. For a while it seemed as if indexes might become part of almost every genre of writing, including epic poetry, drama, and novels; the inclusion of an index had become a literary status symbol, a sign that a text was prestigious or that a book had been lavishly produced. Alexander Pope’s multivolume, best-selling translation of the Iliad, which earned him a fortune,included several grand, exhaustive, and intricate tables and indexes (including one listing the emotions in Homer’s work, all the way from “Anxiety” to “Tenderness”).

In the 1750s Samuel Richardson produced an eighty-five-page index to his enormous novel Clarissa. (It included its own index to the index.) This wasn’t really a reference for the main text, but more like a summary of the moral lessons contained in the original, seven-volume, million-word monster of a book. He called it “a table of sentiments” or (to give it its full title) “A Collection of such of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Cautions, Aphorisms, Reflections, and Observations, contained in the History of Clarissa, as are presumed to be of General Use and Services, digested under Proper Heads,” and toyed with the idea of publishing it separately as a work in its own right. But Richardson, who started out as a printer, was an outlier in his love of indexing (he also later produced a huge unified index to all three of his novels), and this proved to be a largely abortive branch of literary evolution. After all, names and facts are rather easier to index than thoughts and feelings.

Instead, by the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the textual forms of fiction and nonfiction had grown increasingly distinct. The latter were ever more energetically and impressively indexed. In the 1850s Jacques Paul Migne’s monumental collection of the writings of the Church Fathers, in 217 volumes, was accompanied by an equally humongous four-volume index, which was produced by a team of more than fifty laboring for over a decade and was itself divided into no less than 231 parts. There were indexes by author, subject, title, date, country, rank (popes before cardinals, cardinals before archbishops, and so on), genre, and hundreds of other categories—including separate indexes to heaven and hell.

Toward the end of the century, librarians from around the world combined forces to produce a universal, international index of all the most important books and knowledge in existence—as well as, on a more modest but still extraordinary scale, the first global indexes to the flood of periodical publications. In modern fiction, on the other hand, indexing by this time largely appeared only as a literary conceit: a play on genre, fictionality, and facticity. Both Vladimir Nabokov and J.G. Ballard wrote stories that used the index form (in both of which the last entry, at the end of the Z’s, reveals a final twist of the plot).

Duncan is a brilliantly illuminating and wide-ranging guide across this richly varied terrain, though his cast of characters remains overwhelmingly male. He notes in passing that since the 1890s, with the emergence of secretarial agencies, indexers have been largely female, and that today they are overwhelmingly so—including the compiler of his own book’s fine index, Paula Clarke Bain. Unfortunately he doesn’t pursue the point. Yet the gendered, patriarchal hierarchy of labor through which twentieth-century scholarly indexes were commonly produced is fascinatingly evoked by the prefaces to countless books of the era.

In 1983, at the conclusion of his monumental eleven-volume edition of the diary of Samuel Pepys, the lead editor, Robert Latham, compiled what is often regarded as the finest index ever produced in English. Thirteen years earlier, the first volume in the series had appeared in harrowing circumstances: just as it was going to press, his wife, Eileen, to whom he had been married for thirty years, suddenly died. “The late Mrs Robert Latham read many of the proofs,” the anguished editor recorded at the end of his acknowledgments, in the standard, buttoned-up phraseology of midcentury male academic prose. “Beyond that, she gave help which can never be measured.”

By the time he composed the acknowledgments to the index volume, Latham had happily remarried, and the sexual revolution had passed even through Cambridge. His remarks now conjured a more relaxed, less overtly chauvinist world—as well as providing an appealing vignette of familial indexing in practice:

My wife Linnet has shared in the making of this Index. I laid down the ground plan, but she involved herself in every process of its construction. She read aloud the entire text of the diary while I took notes—discussing with me, as we went along, exactly what words might best introduce the successive groups of references, and thus converting what might have been a chore into a paper-game. At later stages she undertook innumerable investigations into detail, and checked from the text every reference in the typescript.

“As a joint enterprise with his wife’s energy and powers of organization, and with a text so entertaining,” he elaborated to the Society of Indexers,

the work in fact often spilled over into hilarity, becoming a game rather than a job. Indeed indexing itself may be seen as a word game, seeking the appropriate word for comprehensive headings or verbal formulas for a whole series of related subjects; Mrs Latham’s expertise in word games accounted for many of their solutions found.

Not every such marital collaboration around this time was as harmonious. In the mid-1970s the new lead author of America’s standard textbook on obstetrics, Jack Pritchard, asked his wife, Signe, to prepare the index for him. They had been married for thirty years. She was a nurse, a mother, and a feminist who had recently changed her title to “Ms.”; his textbook was suffused with attitudes toward women and their bodies that evidently infuriated her. When the index appeared, it turned out that she had included the line “Chauvinism, male, variable amounts, 1–923” (i.e., on every page of the book). Four years later, for the next edition, she improved this to “Chauvinism, male, voluminous amounts, 1–1102” and added, for good measure, another judgment on the whole enterprise: “Labor—of love, hardly a, 1–1102.”

Perhaps she had heard about the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.A few months after Ann Nelson’s father completed the sixth edition of his book, she went off to college. On graduating in 1954 she wed an aspiring lawyer, Richard E. Behrman. Before agreeing to marry him, he later recalled, “Ann made him promise never to ask her to help him write a textbook.” But within a few years, as the seventh edition neared completion, her domineering father demanded that Ann (now referred to as “Mrs. Richard E. Behrman”) and her siblings once more rally around to help him make its index. So she did—and paid him back by adding an entry of her own. Under “Birds, for the,” she listed the entire book, pages 1–1413. Never cross your indexer.

0 notes

Text

In 1941 an ambitious Philadelphia pediatrician, the wonderfully named Waldo Emerson Nelson, became the editor of America’s leading textbook of pediatrics. For the next half-century the compilation of successive editions of this large volume advanced his career, consumed his weekends, and encroached heavily on his domestic life. Every few years, when a new edition was being prepared for the press, he would dragoon his family into assembling the index for him. He would read through the proofs of all 1,500 or so pages, calling out the words and concepts to be listed, while his wife, Marge, and their three children—Jane, Ann, and Bill—wrote down on index cards the thousands of entries and their corresponding page numbers.

Though Nelson was a brilliant physician, even his most admiring colleagues were struck by his “austere and stern” appearance, his “façade of gruffness,” his “granite conviction of right and wrong.” “Whenever I talk to my residents,” he once proudly recounted about his treatment of junior doctors, “they never know whether to laugh or cry. That’s the way I like it.” So it’s not surprising to find that when his teenage children complained about their indexing duties, he responded by printing the following dedication at the front of the 1950 edition of what became known as the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics:

Recognizing that children, like adults, prosper under the stimulus and responsibility of a task to be done, WE ACKNOWLEDGE the contribution that this book has made to JANE, ANN, AND BILL in providing them such privileges, and the satisfaction in family living which has come from group activity

Nowadays we take for granted that any kind of learned book should be indexed, however tedious the labor. So valuable is this tool, so central to our ways of thinking about and using information, that in the case of multivolume scholarly editions of texts, it’s not uncommon for the index itself to constitute an entire book. Yet in the classical world the concept of such a search aid was unknown. To Cicero, an “index” meant a label affixed to a scroll that indicated its contents, rather like the printed spine or dust jacket of a modern volume on a bookshelf. As Dennis Duncan notes in his clever, sprightly Index, A History of the, the rise of the index in its current form is a story of many interrelated developments, each with its own contingencies and chronology: the replacement of scrolls by the codex, the triumph of alphabetical order, the rise of new pedagogies and genres of learning, the invention of print, the adoption of the page number, and the constantly changing character of reading itself.*

Take alphabetical order. Even though the consonantal alphabet had been around since the early second millenium BCE, the earliest known examples of its application as an organizing principle date only from about the third century BCE. The now lost 120-scroll catalog of the Library of Alexandria listed authors partly in alphabetical order. That the ancient Greeks were fond of using it is evident in everything from their fishmongers’ price lists to records of taxpayers and monuments to playwrights (the background panel of one surviving marble statuette of Euripides lists the titles of his plays from alpha to omega).

Yet after them the Romans largely disdained the alphabetical principle as arbitrary and illogical, and so did Europeans throughout the Middle Ages. Books about words—like lexicons, grammars, and glosses—employed it, but it was not a widely understood rule. As late as 1604 the first printed dictionary of English, Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall, was obliged to begin by explaining that its readers should attend to

the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand…and where euery Letter standeth: as (b) neere the beginning, (n) about the middest, and (t) toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with (ca) looke in the beginning of the letter (c) but if with (cu) then looke toward the end of that letter.

The term “index” didn’t come to be used in its current sense in English until quite recently. There’s no entry for it in Cawdrey, while Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) defined it as “the table of contents to a book.” For centuries words like “table,” “register,” and “rubric” were used interchangeably for what we now call indexes and contents pages: only very gradually, over the past two hundred years or so, have the two forms come to be regarded as essentially distinct. (The related Anglophone convention that indexes appear at the back of books and contents pages at the front seems to have been part of a similar, relatively recent process of separating them.) Nonetheless, names aside, the alphabetical index as a type of textual technology turns out to be much older than that.

There are two basic types, which in modern books are usually combined into a single list. One type collates words, the other concepts. The former is a concordance, the latter a subject index. The first is the kind of literal, specific listing of entries that you can get your computer to produce by using CTRL+F for any word or phrase in a text; the second is the product of a more subjective, humanistic attempt to capture the meanings and resonances of a work. Duncan, understandably, is mainly interested in the evolution of the latter type—even though, because of the rise of the word-based online search engine, we now find ourselves living in a golden age of the concordance. But the two forms need to be treated together, he argues, because both were invented at the same time and place: in northwestern Europe, in or around 1230.

The index was, in fact, part of an entire range of organizational and reading tools that were conceived in the thirteenth century. (Others included the division of the Bible into standard chapters and the genre of distinctiones, a new kind of search aid for preachers that helpfully grouped together biblical extracts on the same subject.) Two social developments at this time created a novel demand for information to be organized in rapidly accessible ways: the foundation of the first European universities and the rise of the new orders of mendicant friars, with their stress on the frequent and engaging preaching of God’s word. In Oxford the scholar and cleric Robert Grosseteste (so named, it was said, because of his gigantic brain) compiled an enormous subject index to the whole of the world’s knowledge, to aid him and his students in navigating it all. His Tabula, of which only a fragment survives, encompassed the entirety of the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, the works of classical authors like Aristotle and Ptolemy, and Islamic authorities including Avicenna and al-Ghazālī.

Meanwhile, in Paris, the Dominican Hugh of Saint-Cher (soon to become the first person ever to be painted wearing reading glasses) oversaw the compilation of an even more stupendous alphabetical word index. This was the first concordance to the Bible, listing over 10,000 of its keywords with all their locations, from the exclamation “A, a, a” (now usually translated as “ah!”) all the way to “Zorobabel,” the sixth-century-BCE governor of Judea.

Soon enough, medieval readers were making their own indexes to volumes they owned. The invention of printing brought further refinements. Page numbers had already been used to number the leaves of individual manuscripts, but the uniformity of printed books gave them a different utility, as a means of referring to the same place across different copies of the same work. It took time for this idea to catch on. The first printed page number was not produced until 1470; even by 1500 only a small minority of books had adopted the practice. Instead, early printed indexes referred to textual locations or to the signature marks at the bottom of pages (“Aa,” “b2,” and the like), which printers and binders used to keep their finished sheets in the correct order. But in the course of the sixteenth century, use of the page number spread, alongside the creation of increasingly sophisticated indexes by scholarly authors.

As early as 1532, Erasmus published an entire book in the form of an index because, he quipped, these days “many people read only them.” A few years later his colleague Conrad Gessner, one of the greatest indexers of his day, rhapsodized about how this new search tool was transforming scholarship:

They are the greatest convenience to scholars, second only to the truly divine invention of printing books by movable type…. Truly it seems to me that, life being so short, indexes to books should be considered as absolutely necessary by those who are engaged in a variety of studies.

Like every widely observed change in reading and learning habits before and since (the invention of writing, the launch of Internet search engines, the spawning of ChatGPT), the spread of the index was accompanied by anxiety that flighty, superficial modes of accessing information were supplanting “proper” habits of reading and understanding. In the sixteenth century Galileo complained that scientists seeking “a knowledge of natural effects, do not betake themselves to ships or crossbows or cannons, but retire into their studies and glance through an index or a table of contents.” To “pretend to understand a Book, by scouting thro’ the Index,” jibed Jonathan Swift in 1704, was the same “as if a Traveller should go about to describe a Palace, when he had seen nothing but the Privy.” Yet as Duncan wisely points out, our intellectual habits are always changing, and for good reason. Every social and technological shift affects how we read—and we also all read in many different ways. Twitter, novels, text messages, newspapers: each demands a different kind of attention. The older we get, the more invested we are in modes of reading that we’re familiar with and the more suspicious of technologies that seem prone to disrupt them.

The eighteenth century produced a great efflorescence of indexing novelties, jokes, and experiments, which Index, A History of the has great fun cataloging. For a while it seemed as if indexes might become part of almost every genre of writing, including epic poetry, drama, and novels; the inclusion of an index had become a literary status symbol, a sign that a text was prestigious or that a book had been lavishly produced. Alexander Pope’s multivolume, best-selling translation of the Iliad, which earned him a fortune,included several grand, exhaustive, and intricate tables and indexes (including one listing the emotions in Homer’s work, all the way from “Anxiety” to “Tenderness”).

In the 1750s Samuel Richardson produced an eighty-five-page index to his enormous novel Clarissa. (It included its own index to the index.) This wasn’t really a reference for the main text, but more like a summary of the moral lessons contained in the original, seven-volume, million-word monster of a book. He called it “a table of sentiments” or (to give it its full title) “A Collection of such of the Moral and Instructive Sentiments, Cautions, Aphorisms, Reflections, and Observations, contained in the History of Clarissa, as are presumed to be of General Use and Services, digested under Proper Heads,” and toyed with the idea of publishing it separately as a work in its own right. But Richardson, who started out as a printer, was an outlier in his love of indexing (he also later produced a huge unified index to all three of his novels), and this proved to be a largely abortive branch of literary evolution. After all, names and facts are rather easier to index than thoughts and feelings.

Instead, by the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the textual forms of fiction and nonfiction had grown increasingly distinct. The latter were ever more energetically and impressively indexed. In the 1850s Jacques Paul Migne’s monumental collection of the writings of the Church Fathers, in 217 volumes, was accompanied by an equally humongous four-volume index, which was produced by a team of more than fifty laboring for over a decade and was itself divided into no less than 231 parts. There were indexes by author, subject, title, date, country, rank (popes before cardinals, cardinals before archbishops, and so on), genre, and hundreds of other categories—including separate indexes to heaven and hell.

Toward the end of the century, librarians from around the world combined forces to produce a universal, international index of all the most important books and knowledge in existence—as well as, on a more modest but still extraordinary scale, the first global indexes to the flood of periodical publications. In modern fiction, on the other hand, indexing by this time largely appeared only as a literary conceit: a play on genre, fictionality, and facticity. Both Vladimir Nabokov and J.G. Ballard wrote stories that used the index form (in both of which the last entry, at the end of the Z’s, reveals a final twist of the plot).

Duncan is a brilliantly illuminating and wide-ranging guide across this richly varied terrain, though his cast of characters remains overwhelmingly male. He notes in passing that since the 1890s, with the emergence of secretarial agencies, indexers have been largely female, and that today they are overwhelmingly so—including the compiler of his own book’s fine index, Paula Clarke Bain. Unfortunately he doesn’t pursue the point. Yet the gendered, patriarchal hierarchy of labor through which twentieth-century scholarly indexes were commonly produced is fascinatingly evoked by the prefaces to countless books of the era.

In 1983, at the conclusion of his monumental eleven-volume edition of the diary of Samuel Pepys, the lead editor, Robert Latham, compiled what is often regarded as the finest index ever produced in English. Thirteen years earlier, the first volume in the series had appeared in harrowing circumstances: just as it was going to press, his wife, Eileen, to whom he had been married for thirty years, suddenly died. “The late Mrs Robert Latham read many of the proofs,” the anguished editor recorded at the end of his acknowledgments, in the standard, buttoned-up phraseology of midcentury male academic prose. “Beyond that, she gave help which can never be measured.”

By the time he composed the acknowledgments to the index volume, Latham had happily remarried, and the sexual revolution had passed even through Cambridge. His remarks now conjured a more relaxed, less overtly chauvinist world—as well as providing an appealing vignette of familial indexing in practice:

My wife Linnet has shared in the making of this Index. I laid down the ground plan, but she involved herself in every process of its construction. She read aloud the entire text of the diary while I took notes—discussing with me, as we went along, exactly what words might best introduce the successive groups of references, and thus converting what might have been a chore into a paper-game. At later stages she undertook innumerable investigations into detail, and checked from the text every reference in the typescript.

“As a joint enterprise with his wife’s energy and powers of organization, and with a text so entertaining,” he elaborated to the Society of Indexers,

the work in fact often spilled over into hilarity, becoming a game rather than a job. Indeed indexing itself may be seen as a word game, seeking the appropriate word for comprehensive headings or verbal formulas for a whole series of related subjects; Mrs Latham’s expertise in word games accounted for many of their solutions found.

Not every such marital collaboration around this time was as harmonious. In the mid-1970s the new lead author of America’s standard textbook on obstetrics, Jack Pritchard, asked his wife, Signe, to prepare the index for him. They had been married for thirty years. She was a nurse, a mother, and a feminist who had recently changed her title to “Ms.”; his textbook was suffused with attitudes toward women and their bodies that evidently infuriated her. When the index appeared, it turned out that she had included the line “Chauvinism, male, variable amounts, 1–923” (i.e., on every page of the book). Four years later, for the next edition, she improved this to “Chauvinism, male, voluminous amounts, 1–1102” and added, for good measure, another judgment on the whole enterprise: “Labor—of love, hardly a, 1–1102.”

Perhaps she had heard about the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.A few months after Ann Nelson’s father completed the sixth edition of his book, she went off to college. On graduating in 1954 she wed an aspiring lawyer, Richard E. Behrman. Before agreeing to marry him, he later recalled, “Ann made him promise never to ask her to help him write a textbook.” But within a few years, as the seventh edition neared completion, her domineering father demanded that Ann (now referred to as “Mrs. Richard E. Behrman”) and her siblings once more rally around to help him make its index. So she did—and paid him back by adding an entry of her own. Under “Birds, for the,” she listed the entire book, pages 1–1413. Never cross your indexer.

0 notes

Note

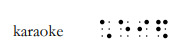

I have a question! Thank you for existing I deeply appreciate it. I was wondering if it is possible for a blind person to be able to read by learning the shape of raised letters, rather than braille. I ask because I have a situation in which it is reasonable that the blind character would know this, if possible, and the person they are travelling with is completely illiterate.I thought it might be interesting if the seeing character could describe the letters, or find a way to texture them so the blind character could tell them what something says. I have done a great deal of research for this character, but this is the one part I can't find a clear answer for. Thank you very much.

Good question, nonnie.

The short answer is, maybe? It would depend on the time period and location of your characters.

Since you want both characters to read, I’ll assume this culture has a formal writing system in place and values written communication.

A Brief History

In order to address this, allow me to offer a brief history of Braille. Because what you’re describing is exactly what happened in France before Braille was invented. This informative video summarizes it pretty well. Here is the text version of the video. The video mentions the embossed letter or raised type method of reading that was used at the time. It was difficult to read and the letters had to be very large in order to be understood, making it harder to read words and sentences. Reading must have been very slow.

According to this page on the National Braille Press website, reading this way required slowly tracing raised print letters. To write, one had to memorize the shapes and try to create them on paper, although they could not read the results.

Creating books was even more difficult. According to this page, [quote] “teacher Valentin Haüy made books with raised letters by soaking paper in water, pressing it into a form and allowing it to dry. Books made using this method were enormous and heavy, and the process was so time-consuming that l'Institution Royale des Jeunes Aveugles, or the Royal Institution for Blind Youth, had fewer than 100 of them when Louis Braille was a student there.” [End quote]

Braille books are already notorious for taking up several volumes. Large print books are only a little better. Textbooks used in schools take up several shelves to translate one print textbook.

Individual use and traveling with these things must have been impossible for the everyday person, even if you were a student.

Also, in this video by blind YouTuber Molly Burke, at the 9:05 time-stamp she answers the question: why don’t we raise print letters for blind people? She explains that it took too long to read and is not as efficient as Braille.

In the interest of time, I’ll try to keep this brief. The transition from the raised print letters to Braille was not a smooth one.

In 1826, first embossed letters published in English was James Gall’s triangular alphabet. Read about it and other systems here.

Another source says Gall’s writing system was introduced in 1831. The system did not gain much popularity outside of Endinburgh.

According to this page: [quote] “In 1832 The Society of Arts for Scotland held a competition for the best embossed type. There were 15 entries but Edmund Fry’s alphabetical system of roman capitals triumphed. Shortly afterwards John Alston began printing at the Glasgow Asylum for the Blind using a slightly modified version of Fry’s design. “Alston type” proved popular and inspired similar forms across Europe and North America.” [end quote]

None of these really caught on outside of certain areas.

In 1821, Charles Barbier was invited to the Royal National Institute For Blind Youth in Paris to demonstrate his Night Writing invention, which was developed for soldiers to read in the dark. It was too difficult to read and so was not used by soldiers, nor did it end up being used by the blind schools. However, a young Louis Braille was in the audience and was inspired.

In 1825, Braille thought he had figured out a good system of writing.

In 1829, he published the first Braille alphabet.

1834 - Braille is invited to Exposition of Industry in Paris, which extended the popularity of the Braille system.

1846- a school for the blind in Amsterdam starts using Braille’s system.

In 1852, Louis Braille dies.

1854- Royal National Institute For Blind Youth officially adopt Braille as official system after fighting it for years.

Because Braille didn’t take hold as quickly in Britain, the British and Foreign Blind Association, all of whom were blind, voted in 1870. They decided Braille was the best system. Braille quickly fell into use all over the world with the exception of the United States. By 1882, the embossed letter system was over.

In the U.S, from 1868-1918, the New York Point system was used. American Braille (developed by a blind teacher named Joel W. Smith) was also used from 1878 to 1918, when the U.S switched the standardized English Braille.

Would Your Character Know Raised Type?

Remember how I said you might be able to do this depending on the time period and place?

If you have French characters, you can used the raised type method as you described in your ask if the story takes place before, probably, 1825. It would be reasonable for your character to know the raised type method if they had attended a blind school before the Braille method was adopted in 1854. Between roughly 1829 and 1854, the French blind character attending school would know about the Braille system and probably complain about their school not teaching it despite Braille himself teaching there.

Similarly, they could used raised type depending on where the story is set, when the character attended school, and what system was in place at the time. If the story is a fantasy, you could make up a history similar to what I described above, although it would be important to have schools for the blind and have Braille or the equivalent be created by a blind character.

Remember that your blind character needs to learn the raised type method if you want them to use it.

If Braille would be available in real life (such as a more modern setting), I would prefer a blind character use Braille instead. Which is why I tried to offer alternatives that were historically justified.

I don’t feel very comfortable with a blind character having to use a raised type method rather than another system, because Braille literacy is declining nowadays and something about learning a raised type method over Braille (or other system, depending on where you set the story and what they were using at the time) doesn’t sit right with me. Your character doesn’t have to use Braille specifically, but I would rather they use the system that is available to blind people at that time. For example, if your story is set in the United States, it would be fine to use American Braille or the New York Point, depending on the time period.

If your story is modern, blind people can usually read raised print letters on signs, such as for the bathroom. In fact, a lot of people who can’t read Braille get by this way. However, keep in mind that we have screen-readers and audiobooks now. People aren’t reading entire texts or even many words with this method.

As for other countries, I tried my best to research what places, such as Japan, used before Braille. For several reasons, including the European-centric search results that keep coming up over and over again, finding the correct information is proving difficult. In some cases, previous methods may have unfortunately been lost due to colonization. It is important that we acknowledge that.

I feel that it would be easier to leave the research up to you since you know where you want to set your story and your own personal background, historical knowledge, etc.

Keep in mind that not all blind people in the world had access to formal education, depending on the place, time, their social class, etc. If you want your blind character to know how to read, you’ll need to find or create a setting that allows for it.

Generally, I would prefer blind characters use methods designed for blind people, whatever that happens to be in that time or culture. Prioritizing the other characters’ needs and having a blind character learn raised type over Braille when Braille actually exists in the story doesn’t work for me.

Like always, I suggest having more than one blind character in the story to avoid tokenism. Also, since your character is going to teach another character, be sure to show your blind character’s needs and goals as well.

I hope this helps. Feel free to message me or send another ask. I am not a historian and so if anyone wants to correct anything, such as dates, or provide any relevant knowledge, please feel free. I tried my best with this question. I would be grateful for help if anyone has more information!

-BlindBeta

203 notes

·

View notes

Text

So Putin is old and bored and decides to make himself a sexy Russian autocratic in the traditional Russian way, randomly committing human rights abuses in Ukraine. So far so typical, the Russians terrorizing Ukrainians for no good reason is so standard issue historically that them doing it now is met with little more than frustrated whining from the rich lawyers democracy has embarrassingly put in charge of the West.

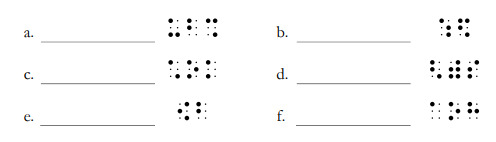

But here is the especially weird part. This is the symbol adopted by the racist thug-bullies supporting that Little Bitch Putin®'s evil invasion and war (which has cost 200,000 Russian lives, and they are losing):

This is a letter Z, in the style of a traditional Russian military St. George ribbon.

Here's the thing. The Russians use the Cyrillic alphabet. It doesn't have a Z. Or, it does, but it doesn't look like that. So they are using a Z from the Roman alphabet. That we use in the West.

A big part of Little Bitch Putin®'s justification for this war is, trust me on this, that Ukraine is ruled by evil invisible Nazis that created Covid-19, a virus they invented to specifically destroy traditional patriarchal society so that everyone automatically becomes atheist and gay, like in the Western world. Also, there is a bunch of weird Slavic-supremacist mystical religious stuff mixed in here too. Which is especially odd, since the Ukrainians are also Slavs, and belong to the same church. And also, that virus started in China and has ruined the whole world...especially China.

It's almost like this is a bunch of nonsense desperately made up by a monster to try and justify his evil behavior to people whose taxes pay his secret salary.

The point is, in Little Bitch Putin®'s version of reality, the West is a drag show teaching evolution to children so hard that all Russian penises will shrivel up and fall off, and the only solution is blowing up Ukrainian schools with missiles. And his chosen symbol is this:

A letter from the Western alphabet. That Russia doesn't use.

In the colors of the Ribbon of St. George. This is, truthfully, a traditional military honor in Russia, dating from a long time ago.

Namely, the 18th century. When Russia was ruled by 1) not a Slavic patriarch, but by a woman. And 2), that woman was Catherine II or Catherine the Great. A GERMAN PRINCESS.

The yellow-orange and black colors are the traditional colors of her royal family. Her royal GERMAN family.

If you don't know, when Russia complains about "the West," they mean America now. Doesn't everyone?, and with good reason. BUT. Before like WWI, when Russia hated "the West," they meant Germany. Russia and Germany have, in various forms and across various times, been feudin' mount'in holler clans for a very long time. For proof, look at what Russia did to East Germany after WWII. Russia HATES Germany.

In fact, that is why Little Bitch Putin® always calls the invisible evil Ukrainians "Nazis". He's invoking the traditional Russian-to-German hate.

And this is his symbol:

A Western letter Russians don't use, in the colors of a German royal family.

My goodness, Vladimir. You really are a stupid little bitch.

#z#putin#russian war on ukraine#special military operation#fuck putin#fuck russia#Little Bitch Putin®

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there! If it s not too much trouble, how do you feel about media/pop-culture portrayal of druids?

Since the word “Druid” is used a lot to mean “Nature Wizard” would you prefer if people used/make up their own different words for their stories or find it ok to use the term as long as they’re respectful or accurate to Druidism to some degree?

In terms of the "best" media depiction of druids, I think the BBC series Merlin with Colin Morgan is probably the closest we can get to a positive portrayal of the Celtic priestly caste. I still hesitate to describe it as accurate, but at the very least I wasn't balking at the show as much as I did when watching an episode of The Librarians. We'll get to them in a moment.

There's also the fun Australian miniseries Roar that starred a young Heath Ledger. It was full of historical inaccuracies (the premise being about a Roman-occupied Ireland for one thing). But it portrayed the druids in a positive light despite being at a time when they were in decline.

In the TV show The Librarians: And the Rise of Chaos (season 3 episode 1) they have a very brief (2-3 minute) run-in with some angry druids. The mob only shouts and growls but don't seem to speak, all while wearing tattered robes and brandishing wooden farm implements of various functions. They were also wearing cringey cast-resin masks of animal skulls that miraculously fit perfectly on their faces and just looked fake. I should point out this show takes place in the present.

The librarians have to climb a wicker man and solve a puzzle to steal a rune-covered stone artifact. The puzzle is based on a Celtic board game gwyddbwyll AKA fidchell. In the episode, the game pieces are Norse runes (Elder Futhark). Historically, the Iron Age Celts would not have used those runes. The game pieces should be carved figures of warriors instead. Then things get a bit personal with the tree stump inscription.

One librarian translates the markings on the stump which he says are "ancient Gaulish mixed with third century astrological symbols," and somehow reads "when the king reaches the north, the light will reveal itself."

*FACEPALM*

Well the three symbols on the left side are more Norse Elder Futhark (i.e. not even Celtic), the symbol cluster in the upper right corner looks like it could be vaguely Lepontic script (i.e. yes, “ancient Gaulish”) but that specific one is not in the Lepontic alphabet at all. Just for fun they have the symbol for Aries (the aforementioned (but singular) Greek astrological symbol). The Celtic triskele is in the upper middle of the stump and variations of it go back thousands of years, but it doesn't really have a universally accepted meaning.

What upset me the most was the incorporation of the Druid Sigil (bottom center of the stump). It is the official symbol of the Reformed Druids of North America (RDNA). The RDNA invented the Druid Sigil in 1963 to be a geometrically simple symbol, yet at the same time - unique. They went through books of symbols to make sure it didn't already exist. The RDNA founders described the Druid Sigil as a symbol for the Earth-Mother, but it is truly devoid of a specific meaning or powers.

In the RDNA, the individual imparts their own meaning into the Sigil, and whatever powers they want it to have if need be. To me the Druid Sigil is a sun wheel, and the two vertical lines represent the Two Tenets of Reformed Druidism. It means something different to everyone, and it is neither ancient Gaulish nor third century anything. The show producers obviously googled “Druid symbols” and that was the extent of their research.

I guess if someone was to make a new show, movie, or other media about druids, I would prefer that it would at least clearly be in the high-fantasy genre if they're going to make them all fanciful magic users, and especially if they're going to be portrayed as bad guys. If the show is trying to be more historically accurate, I'd much prefer that they stick to what's verifiable (though admittedly that's not much). Otherwise yeah, it would be nice sometimes if they used a different term, like sorcerers or warlocks if they're bad guys.

Oh gosh, Warlock! That was a 1989 supernatural horror movie that started a trilogy of gory films. The warlock was a bad guy, and a secret bloodline of druids were the only ones who had a chance of stopping him. The depiction of druids was okay I suppose, and on the plus side they wore plain everyday clothes in the 20th century, 'cause you know it's important to blend in.

See Also:

History of the Druid Sigil

Common Symbols in Druidry

#druids#media#depiction#portrayal#Merlin#Colin Morgan#Heath Ledger#Roar#Lepontic#Runes#Gaulish#Librarians#Symbols#Futhark#Druid Sigil#Triskele#Warlock#Sourcerer

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes Aziraphale feels old. Or, he feels weary and achy and tired. He is old, that’s for certain, but angels don’t really get old. He’d been wearing this face since the dawn of time, and sometimes his cheeks were plumper or thinner, and sometimes there were bags under his eyes, but it hadn’t aged a day. Sometimes he remembers the inquisitions, the revolutions, the crusades, the war and the horror of it all, and he laments how much his years have let him see.