#Shino Mayu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Shiraiwa Tomo 白岩冬萌 Aoyama Nanami 青山七海

Megami Jun 女神ジュン

Shino Mayu 篠真有 Momose Himari 桃瀬��まり

▶︎ DEBUT OCTOBER 2024 Best Monthly AV Newcomer

youtube

#av女優#av idol#avfanatics#デビュー#Shiraiwa Tomo#白岩冬萌#Aoyama Nanami#青山七海#Shino Mayu#篠真有#桃瀬ひまり#Momose Himari#Megami Jun#女神ジュン#Youtube

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submissions Open for the Shoujosei Tournament.

Submit Shoujo and/or Josei Manga and (if you want) propaganda through ask or submit a post.

Unlike other tournaments, this one will be split into two sections. The Shoujo Side and the Josei Side.

Top 4 submissions in both sections are the ones I submitted myself.

@tournament-announcer

Submissions in bold have propaganda, submissions not in bold do not have propaganda. Whether they do or do not have some already, you are still free to submit some.

All Tournaments can be found on my pinned post. There you can see the ones that have been completed, the ones that are currently running, the ones that are pending and the ones that have submissions open.

SUBMISSIONS:

Shoujo

Magic Knight Rayearth (CLAMP)

Natsume's Book of Friends (Yuki Midorikawa)

Saiunkoku Monogatari (Kairi Yura & Sai Yukino)

Usotoki Rhetoric (Ritsu Miyako)

Sakura Hime: The Legend of Princess Sakura (Arina Tanemura)

Shiroi Heya no Futari (Ryouko Yamagishi)

Oniisama e (Riyoko Ikeda)

Himitsu no Hanazono (Fujii Mihona)

Maria-sama ga Miteru (Oyuki Konno & Satoru Nagasawa)

Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon (Naoko Takeuchi)

Ouran High School Host Club (Bisco Hatori)

Cardcaptor Sakura (CLAMP)

Kimi ni Todoke (Karuho Shiina)

Hana Yori Dango (Yoko Kamio)

Arisa (Natsumi Ando)

Kieta Hatsukoi (Hinekure Wataru & Aruko)

Hell Girl (Nao Kodaka, Miyuki Etou & Hiyoko Hatano)

Honey Lemon Soda (Mayu Murata)

Aoharu-sou e Youkoso (Minami Mizuno)

Kamisama Kiss (Julietta Suzuki)

Gakuen Babysitters (Hari Tokeino)

Basara (Yumi Tamura)

A Condition Called Love (Megumi Morino)

7Seeds (Yumi Tamura)

Banana Fish (Akimi Yoshida)

Fruits Basket (Natsuki Takaya)

-

Josei

Chihayafuru (Yuki Suetsugu)

Don't Call it Mystery (Yumi Tamura)

Helter Skelter (Kyoko Okazaki)

Nina the Starry Bride (Rikachi)

Love My Life (Yamaji Ebine)

Ohana Holoholo (Shino Torino)

Wotaku ni Koi wa Muzukashii (Fujita)

My Next Life as a Villainess (Nami Hidaka & Satoru Yamaguchi)

Honey and Clover (Chica Umino)

Bokura no Kiseki (Natsuo Kumeta)

Hirano and Kagiura (Harusono Shou)

Ikoku Nikki (Tomoko Yamashita)

#shoujosei tournament#shoujosei#shoujo#josei#magic knight rayearth#natsume's book of friends#saiunkoku monogatari#usotoki rhetoric#chihayafuru#don't call it mystery#helter skelter#nina the starry bride#submissions

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

shoutout to the name doubles in our system

abby and abee

aidan and aiden

alex and alexis

allie, allison h, allison k, and allyson

amanda h, amanda m, and amanda y

april m and april y

bea, bee, and bee-l

bill c and bill d

king, king c, and king

brit and britney

cami and camie

carlos d and carlos r

casey, cassie, and castor

charleigh, charlie d, charlie m, and charlie s

chris, christina, and christine

claire and clarisse

courteney and courtney

eddie k, eddie m, and eddiev

el, eleven, eliana, elizabeth, ella, and elle (all respond to el)

emira and emma

ethan c, ethan k, and ethan n

eva, evan, and eve

finn and finney

fred and freddy

gin and gina

gregg and gregory

griff and griffin

harlan, harley, and harbor

hawks and hawkins

heather k and heather m

himiko and hiyoko

isabela and isabella

ivy and ivy s

jade h and jade w

james r and james w

jax, jay, and jaz

jenni and jennifer

john b, john l, john m, and johnny

kaede and kaede

katelyn and katie

klaus b and klaus h

kris and kris c

leo and leo v

lilith, lily and lina

liz and lizzie

lucy l, lucy, luisa, lulu g, and lulu p

marcie and marcy

mark b and mark f

matt and matt

max and maxx

may, maya, and mayu

mike and mikey

mandy and mindi

moon and moon

peter, pieter, and petaro

pomeline and pomni

sidney and sydney

raine, ray, ray s, raya, and rayleigh

ren, rena, and rena r

robbie and robin

roman r, roman s, rowan, and roxanne

ryan and ryan e

ryukyu ad ryuuko

sal and sally

sam, sam c, sam e, and sammy

shin, shina, and shino

star b and star c

tamaki, tatami, and tatum

tobias, toby ra, toby ro, and tubbo (all respond to toby)

tyler and tyson

vickie and vicky

will, willow, and willow p

yada, yuka, and yuta

zoe l, zoe o, and zoey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

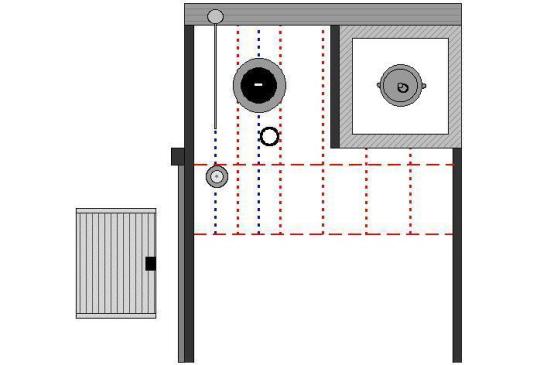

Some Random Thoughts on the Practice of Chanoyu (13): the Use of the Ro during the Furo Season (Part 1).

A while ago, someone asked about how the ro might be used during the furo season. So -- because I think it might be good to take a short break from our discussions of tsuzuki-kane [續きカネ] and soe-oki [添え置き] -- I decided to use a recent chakai from the month of May, as a way to illustrate this matter.

Before looking at the tori-awase of the chakai, however, it might be good to repeat something that has been said here before: before Jōō created the irori, the only way chanoyu was being performed was with the furo.

Things had already started to move away from the daisu by that time (it appears that Shino Sō-on was already placing the furo on a round shiki-ita, which he arranged beside his family’s chū-ō-joku -- it seems that it was from Sō-on’s idea that Jōō derived his square ko-ita, by cutting a square within the circle); but the furo itself, even if Japanese-made, was still a very expensive object (and, in the case of the lacquered clay Nara-buro and mayu-buro, one that could easily be damaged as well).

It was in order to eschew the entire issue that Jōō recognized the communal cooking pit in the common room of the farmhouse as a potential alternative; and once it was perfected, his intention was that it be used all year round as the ultimate realization of the wabi aesthetic. Indeed, the furo was not used in the small room setting until after Rikyū entered Hideyoshi’s household (which he did between the end of 1582 and early 1583) -- the first example of which was when the small unryū-kama was used in the large Temmyō kimen-buro that was arranged on the Yamazato-dana [山里棚] (a tana resembling an inakama take-daisu, though with the front right leg removed and the ten-ita cut into a roughly triangular shape, both of which were necessary accommodations if the large Temmyō-buro was going to be placed on such a tana) in Hideyoshi’s Yamazato-maru [山里丸] (the 2-mat room that was constructed in the boathouse on the inner shore of the moat that surrounded Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle).

The first public reveal of this “new” way of serving tea in the small room appears to have been when Rikyū brought the same furo and kama to Kyūshū, and placed them directly on top of the wooden lid that he made to cover the mukō-ro in the tearoom that he had constructed in the “tea village” on the grounds of the Hakozaki-gu [筥崎宮], during the summer of 1587. So, prior to that occasion, only the ro had been used in the small room setting, irrespective of the season or temperature.

Turning now to the chakai that was held on May 14:

The kakemono was written by the Korean monk Seok-jeong of the Gumgang Temple in Busan. Seok-jeong s’nim is very famous for his cartoon-like sketches of Buddhist figures. This scroll features a painting of Bodhidharma, with his left hand raised, and the colophon jwa dan shib-bang [坐断十方] (za dan jippō; “from your seat scatter the ten directions” -- the meaning is to shed our misguided perceptions of reality through the repudiation of our ego, by means of the cultivation of samadhi via seated meditation).

The hyōgu [表具] is fairly typical of scrolls made for modern-day tea use, in terms of its proportions and the selection of the fabrics used; however, one point of note is that the handles are made from polished (but unpainted) natsume wood.

The chabana consisted of white tsuri-gane-sō [釣鐘草] (Campanula takesimana) and murasaki tsuki-gusa [紫露草] (Tradescantia ohiensis), in a coarsely woven bamboo basket.

The kama was a medium-sized unryū-gama [中雲龍釜].

The mizusashi was brown Seto ware, one of a group of mizusashi that Jōō ordered from the Seto kiln during his middle period (for use on the fukuro-dana -- they are thus associated with the early use of the ro, and are of the ideal size for chanoyu).

The name of this particular mizusashi is “Odori Hotei” [踊り布袋] (“dancing Hotei” -- Hotei being one of the seven Gods of Good Fortune, with his dance symbolizing unrestrained joy and contentment).

The chawan was black Raku-ware (of the Ō-guro [大黒] variety); the ko-bukusa [小フクサ or 古フクサ] was sewn from a variety of meibutsu-gire [名物裂] known as tan-ji chū-keitō-kinran [丹地中鷄頭金襴].

The chashaku is named “Yoka” [餘花] (which means flowers -- usually the word refers to cherry blossoms -- that bloom several weeks after the season has passed).

The chaire was made of Bizen-yaki [備前焼], by Kimura Yūkei Chōjūrō [木村友敬長十郎], the fifteenth generation master of the original Imbe kiln. Since the Edo period, it had been the practice of his family to make copies of all of the meibutsu chaire; this is his copy of the chū-ko meibutsu [中古名物] Seto hyōtan-chaire [瀬戸瓢箪茶入] named Kūya [空也].

The shifuku was sewn from a piece of a summer kimono material (from the early Shōwa period), with the design called seikai-ha [青海波].

The futaoki is an iron kakure-ka [隠れ家] (this shape of futaoki is usually called gotoku [五徳] today); and the koboshi is made of lacquered bentwood (this koboshi was favored by Ryōryō-sai Sōsa [了々齋宗左; 1775 ~ 1825], the ninth generation iemoto of Omotesenke).

The reason why I decided to begin by mentioning the tori-awase was to give this explanation context -- because the selection of utensils necessarily has an impact on the temae.

According to Jōō, when the ro is used all year round (which was his original idea for chanoyu in the wabi tearoom), during the spring and summer, the ro-buchi [爐緣] should be of unpainted wood¹, while during the autumn and winter, it should be lacquered (in the wabi setting, this meant rubbing with lacquer, or the use of one of the less fastidious techniques, was preferred over something like shin-nuri).

As for the question of incense, when Jōō began to use the ro, the only kind of incense used in the tearoom was made from crushed incense wood -- jin-kō [沈香] or byakudan [白檀]² -- which was drizzled along the length of the dō-zumi [胴炭]³ (so the incense would continue to perfume the air over the course of the gathering). Since byakudan is the smell of the furo season, it is entirely appropriate to use it in the ro during the furo season (and that is what was done on the present occasion)⁴.

As for this particular two-mat room, the length of the guests’ mat has been emphasized by the 8-sun 2-bu wide board (which functions as an ita-doko), while the utensil mat was made to look smaller by replacing the far end of the tatami with a board 2-sun 5-bu wide. This arrangement where the ko-ita extends completely across the mat predated the appearance of the tsuri-dana: the board allowed the hishaku to be displayed on the mat (as here), without having to rest on the futaoki⁵; the kōgō was also commonly displayed on the board (according to the records of Rikyū’s own gatherings).

Placing a pair of fusuma to the left of the utensil mat mirrors Jōō’s own arrangement of the utensil mat of his Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵]⁶. The fusuma allowed the host to lift the various utensils directly onto the utensil mat⁷. For that reason, a tana was always placed on the far side of that fusuma, to keep the utensils from sitting directly on the floor⁸.

The kama is an unryū-gama, which was suspended from the ceiling on a susu-dake ji-zai [煤竹自在]. Most of the unryū-gama made since the Edo period have the handle of the lid made of a small ring. The reader should notice the direction in which the ring-handle faces in the drawings. This orientation allows the ring to be pinched from the sides, between the thumb and first finger of the right hand, when it is picked up. This is the traditional way for such handles (which predated the unryū-gama by at least a century) to be oriented. The host should be sure to open the lid of the kama slightly before calling the guests back to the tearoom, to let the built-up steam escape.

The mizusashi is centered on the left side of the mat, with the futaoki placed in front of it (so that it is in between the two kane). The cup of the hishaku rests on the board (5-bu from the wall), with the handle running along the kane; and with the chaire displayed on the near side of the yū-yo [有餘] (this is referring to the 2-sun wide space that extends across the mat in front of the mukō-ro: nothing should be placed in the yū-yo).

The chawan and koboshi should be prepared as usual (in the case of the chawan, the chashaku should be oriented facing upward -- this was Rikyū’s rule); and, together with the go-sun-hane [五寸羽]⁹, they should be arranged on the tana (in the katte) in a manner that will facilitate their being lifted onto the utensil mat at the beginning of the temae.

The goza begins with the host opening the door, and bowing to the guests. Then he slides across the sill on his knees (according to Rikyū, people should not stand up in the small room; moving about is done on the knees). The host immediately turns back to face the open doorway, and slides the fusuma closed¹⁰. (It is important that he do this every time¹¹, since otherwise it will be impossible to open the other fusuma, to access the utensils placed there). Then he turns back to fact the shōkyaku, and the two exchange words¹².

The the host turns to the left, and slides forward toward the temae-za, where he pauses briefly to appraise the condition of the fire¹³. He should also take note of the other utensils, making sure that they are still in the same places as when he arramged them on the mat (and if not, he should rectify things now).

After turning to face the fusuma¹⁴, and sliding it open, the host lifts the chawan onto the utensil mat (placing it in the lower left-hand corner of the temae-za). Then the koboshi is taken out, and the fusuma is closed.

The host turns to face the far end of the mat again. First the chaire is moved so that it overlaps the kane that is to the left of the central kane “by one third¹⁵.” The kane, in this case, is the me to the right of the futaoki¹⁶.

The the host then moves the chawan to the left side of the chaire. The foot of the chawan should be immediately to the right of the endmost yang-kane (which is 5-me to the left of the futaoki)¹⁷, with the back of the chawan’s foot touching the front edge of the yū-yo.

Next, the futaoki is picked up (with the right hand) and placed on the right side of the mat. Here its kane is on the fifth me from the heri; and it should be 2-sun from the front edge of the ro-buchi.

Then the host picks up the hishaku with his left hand¹⁸, and reholds it with his right. Holding the hishaku horizontally in front of his body, above his knee-line, he first moves the koboshi forward with his left hand (so it is 2-sun 5-bu below the lower edge of the temae-za), and then rests the hishaku on the futaoki.

According to Rikyū, the hishaku should be held so its cup approaches the futaoki at an angle (so that the corner is fitted into the depression in the center of the futaoki¹⁹); the hishaku should be brought into contact with the futaoki gently, and then the handle should be lowered to the mat²⁰. The handle should rest on the heri, with its right side to the left of the heri’s middle²¹.

After placing the hishaku on the futaoki, the initial arrangement is completed, so the host and guests bow for the sō-rei [総礼].

Following the sōrei, the host pauses momentarily, to collect his thoughts. Then the chawan is picked up and moved in front of his knees (the left side of its foot should be immediately to the right of the central kane, while the far side of its foot should touch the front edge of the yū-yo -- this is necessary so there will be sufficient space in front of the chawan for the chaire). Then the chaire is moved between the chawan and the host’s knees, with the chaire resting squarely on the central kane.

The host unties the himo, and then removes the shifuku in the manner appropriate to the kind of chaire he is using. The chaire is placed down on the mat again, and the shifuku is smoothed out, and then placed on the far side of the yū-yo -- with the mouth facing forward (according to Rikyū’s instructions), and the uchi-dome of the himo pointing toward the center of the mat.

The host then removes the fukusa from his obi, folds it, and tucks it into the futokoro of his kimono (or, if he is not wearing a kimono, he tucks the folded fukusa into his belt, near his right hip²²).

Then the host picks up the chaire, and while holding it over his left knee (the heel of his left hand can rest lightly on his left leg at this time, for security), he takes out the fukusa. Raising the chaire to the center of his body (above his knee-line), he wipes the lid, and then the shoulder, with the fukusa. Then, after returning the fukusa to his futokoro (or tucking it into his belt) once again, the chaire is lowered to the mat. Its back side should touch the front edge of the yū-yo, while it should not cross the kane on the left (this is a memory of the shiki-shi [敷き紙], where nothing resting on it was allowed to project beyond its edges).

The host then moves the chawan forward (so that its back side touches the front edge of the yū-yo). He takes out his fukusa, and places it on his left palm. Then he picks up the chashaku, cleans it with the fukusa, and rests the chashaku on top of the chaire. After which the fukusa is returned to his futokoro (or slipped under his belt).

Next, the host lifts the chasen out of the chawan and stands it on the mat on the same (yin) kane on which the futaoki is resting.

The the host takes out his fukusa, and wipes the lid of the mizusashi (because, on this occasion, the mizusashi has a lacquered lid) -- in front of the handle, on the far side of the handle, and then from the handle off the right side. (The case where the lid is made of the same material as the mizusashi was the original situation. Because the idea of making a lacquered lid for a mizusashi only appeared around the middle of the fourteenth century, it was felt that certain changes to the temae were necessary -- to make the use of a lacquered lid “more difficult²³.”) Then the lid is picked up with the right hand, reheld from the side with the left, and then leaned against the left side of the body of the mizusashi (the lid should touch the mat 3-me from the left edge of the foot²⁴).

Opening the mizusashi at this time is necessary because the kama is an unryū-gama: because of the small size of this kama, the water boils away very quickly²⁵. Thus, it is necessary to constantly replenish the kama with cold water, starting as soon as the lid of the kama is removed.

The host then picks up the hishaku with his right hand, and reholds it in his left hand so that it is above his left knee (it was at this time that it was held in the “kagami-bishaku” [鏡柄杓] position: opening the lid of the kama was felt to be akin to revealing the host’s heart -- the state of his samadhi -- to his guests, and so the hishaku was held like a mirror onto which his samadhi was reflected). He then takes the chakin out of the chawan and uses that to protect his fingers while lifting the hot lid off the kama. (As mentioned above, the ring-handle of the lid is pinched from the sides between the host’s thumb and first fingers -- with the chakin between the skin of his fingers and the metal of the ring.) The lid is lowered to the futaoki.

When the ring is held in this way, it will be pointed toward the lower right-hand corner of the temae-za. This leaves the side of the lid facing toward the middle of the mat completely unobstructed (meaning that there is no need to flip the ring over, the way certain modern schools teach²⁶). After placing the lid of the kama on the futaoki, the chakin should be rested on the lid (as shown in the drawing).

Then, after reholding the hishaku with his right hand, two hishaku of cold water are immediately added to the kama (to replenish what has boiled away since the sumi-temae), followed by a yu-gaeshi [湯返し]. After which, a quarter hishaku of hot water is dipped from the kama and poured into the chawan.

The host then immediately adds one hishaku of cold water to the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi; after which the hishaku is rested on the kama as usual.

Then the host picks up the chawan, rotates it three times above the koboshi, discards the water, and returns the chawan to the mat in front of his knees.

The hishaku is picked up again, and a half hishaku of hot water is poured into the chawan. Once again, the host immediately adds a full hishaku of cold water to the kama, performs another yu-gaeshi, and again rests the hishaku on the kama²⁷.

The lid of the mizusashi is then closed, and wiped with the host’s fukusa in the same way as before it was opened.

Then the hishaku is picked up, and held with the left hand above the host’s left knee (kagami-bishaku, once again); and, again using the chakin (the lid will still be quite hot), the lid of the kama is picked up, and placed on the kama, closing it completely. Then the chakin is placed on the lid of the mizusashi, and the hishaku is again rested on the futaoki.

Then he picks up the chasen and rests it in the chawan, leaning against the far rim of the bowl. Then he performs the chasen-tōshi in the usual way, stands the chasen on the right side of the mat as before, and discards the water.

He dries the chawan with the chakin²⁸, places the chawan down on the mat in front of his knees, and returns the chakin to the lid of the mizusashi.

In the usual way, the host picks up the chashaku, and then the chaire, and transfers enough matcha to the chawan to make one portion of koicha (according to Rikyū’s way of doing things).

After returning the chaire and chashaku to their places on the left side of the mat, the host picks up the hishaku and holds it above his left knee (kagami-bishaku, again). Then, picking up the chakin, he again opens the kama, resting its lid on the futaoki (and then placing the chakin on the lid, as shown above).

At this time, during the furo season, the host once again rests the hishaku on the kama -- without doing anything else.

Then -- because this is the furo season, so cold water has to be added to cool the kama slightly before preparing koicha²⁹ -- the lid of the mizusashi is again wiped with the fukusa (as before), and then opened.

The host then adds one hishaku of cold water to the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi. Dipping out a full hishaku of hot water, he pours an appropriate amount over the matcha in the chawan, and returns the rest to the kama. (At this time he does not add any more cold water, since he already did that before dipping out the hot water.)

Picking up the chasen, the host blends the matcha and hot water together to make koicha³⁰.

After the host has finished blending the koicha, the chasen should be placed on the left side of the mat, on the endmost yin-kane; it should also be in line with the center of the chawan.

_________________________

◎ While the details of the temae narrated here agree with Rikyū’s own writings, they might not necessarily conform with the way the modern schools teach these things. In every case where the temae practiced by the school with which the reader is affiliated differs from what is written here, it would always be best to follow your own school’s preferred methods.

¹On this occasion, the ro-buchi was made of sawa-kuri [沢栗] -- a variety of chestnut wood that grows near streams in the wild. This wood, which is beige, with a slightly darker grain, was the kind of ro-buchi preferred by Jōō and Rikyū for this purpose.

²Before the modern period, byakudan with a reddish tinge was preferred (since it has a more subtle aroma than white byakudan). However, this kind of byakudan is rarely seen today.

³Crushed incense wood is what is used in the temple setting.

Chips of incense wood, such as are usually used today, were originally made to perfume the breath while speaking (a chip was held under the tongue for this purpose).

It is unclear from the historical records when the change from crushed incense to wood chips was made.

⁴Neri-kō, as a way to perfume the air in the tearoom, did not come into use until a number of years after Jōō began to use the ro in his 4.5-mat tearoom.

When neri-ko was used throughout the year, the blend appropriate to the particular season seems to have been preferred:

◦ bai-ka [梅花] was used in spring;

◦ ka-yō [荷葉] was used in early summer;

◦ ji-jū [侍従] was used during the rainy season;

◦ ka-yō [荷葉] was used again during the period of intense heat;

◦ kikka [菊花] was used in early autumn;

◦ raku-yō [落葉] was used from late autumn to early winter;

◦ kuro-bō [黒方] was used in the depths of winter.

The reader should understand that this is only one system. Other series (in which the various blends were sometimes associated with different seasons) are also described in the classical literature (and these tend to reflect period-specific preferences -- which may or may not be tied to the availability of certain of the ingredients, most of which had to be imported from the continent).

This sequence cited above appears to follow the traditional division of the tea year into seven seasons (which primarily was used as a guide to the selection of the utensils): shun [春], u-zen [雨前], u-chū [雨中], u-go [雨後], shū [秋], shō-kan [小寒], dai-kan [大寒].

⁵In the early days, people were still using the treasured futaoki that had been placed on the daisu and other tana-mono, which were objects of appreciation. Resting the hishaku on the board permitted the guests to look at the futaoki without having to touch any of the other utensils*. __________ *If, for example, the hishaku was resting on the futaoki, since there was no tana in this kind of room, the question became what to do with the hishaku while looking at the futaoki. Placing it on the floor would dirty it.

Also, if the hishaku was resting on top of it, it is likely that the guests would not be able to see the futaoki clearly, and so not recognize what it was.

⁶The Yamazato-no-iori [山里ノ庵] was Jōō’s first 2-mat daime room. It was built in late 1554 or early 1555, at the same time as Rikyū’s Jissō-an [實相庵].

⁷Moving back and forth between the utensil mat and the katte, while carrying in the utensils one by one, was something that was supposed to be done only in the shoin setting.

In the wabi room, it was preferred that once the host reached the temae-za, he should not leave again until the service of tea was finished (this seems to have been Jōō’s idea from the beginning).

⁸These drawings show Rikyū’s tabi-dansu [旅簞笥] (which was used with the door removed, since the fusuma itself fulfills that function), since that tana is less deep than most of the others -- though any sort of mizusashi-dana could be used. In Jōō’s day there was a preference for high-quality mizusashi-dana with four legs, since those tana (fine though they might be) could not be used on the utensil mat.

The tabi-dansu was designed as a portable dōko (for use in a larger room that had not been constructed as a dedicated tea room -- meaning it had neither a ro, nor a built-in dōko). At the siege of Odawara (in 1590), Rikyū used the tabi-dansu when serving tea during Hideyoshi’s conferences with his generals. The furo-kama (the small unryū-gama in the large Temmyō kimen-buro), mizusashi (kiji-tsurube), and futaoki were arranged on a naga-ita. After everyone had taken their seats, Rikyū entered carrying the tabi-dansu in front of his body. He placed it on the mat to the left of the one on which the naga-ita was arranged*, opened the door, and then turned to face the naga-ita†.

The tabi-dansu was made so that it could be used with any chaire, except for a large katatsuki resting on a chaire-bon selected according to Jōō’s method (that is, the tray would be 3-sun larger than the chaire on all four sides). A tray of that size will not fit inside this tana. However, Jōō’s tray for a ko-tsubo chaire (such as Rikyū’s “Shiri-bukura” chaire [尻膨茶入]‡) would fit. A large katatsuki would have to be used with a tray selected according to Rikyū’s calculations (in other words, the tray would be 2-sun larger on all four sides). A clear understanding of the distinction between these two kinds of bon-chaire will be very useful for anyone who hopes to make sense of the aesthetics of Rikyū and his followers. ___________ *In, for example, an 8-mat room, it seems that Rikyū performed the temae on the left of the two mats in the middle, with his assistant (who conveyed the bowls of tea to each guest) seated on the next mat.

†This is completely different from how the tabi-dansu is used today.

‡Which he used during the most intimate conversations between Hideyoshi and one of his officers, or when receiving an envoy from the Hōjō defenders.

⁹The go-sun-hane [五寸羽] is the small-sized habōki that is used on a daime utensil mat.

In the small room, the utensil mat is always considered to be a daime (regardless of its actual size), since the lower 1-shaku 5-sun of a full-length kyōma tatami was always yū-yo in the small room setting.

¹⁰Rikyū preferred to reach across his body. Thus, when opening the fusuma (which, in the example shown, would slide from the host’s right to left), the host would reach up to the hand-hold with his left hand and, after opening the door 1-sun or so, push the fingers of his left hand through the aperture, and so pull the door open to the middle of his body. Then he would lower his left hand and continue pushing with his right hand until the door was open.

The door should not be slid open completely. Rather the panel that was just opened should be left projecting 1- or 2-sun beyond the edge of the other panel, so it can be grasped easily when it is time to close the fusuma again.

¹¹Unlike in the versions of the furo-season usage taught by many of the modern schools, where the fusuma by which the host enters and exits the utensil mat is occasionally left open -- ostensibly for the purpose of keeping the tearoom from becoming too hot -- this cannot be done in this room (since it will make it impossible for the host to open the other fusuma, through which he accesses the objects arranged on the tana behind it).

Furthermore: in Rikyū’s period the tea gathering was considered to be an extremely private affair, meaning that the doors would always be closed (and locked, where locks were available).

¹²Their discussion, at this time, is usually focused on the chabana, and the objects arranged on the utensil mat.

¹³According to Rikyū, the condition of the fire is the thing that determines what can be done during the gathering -- and a master chajin was one who could build a fire during the sumi-temae (always at the beginning of the shoza) that would keep the kama boiling until the service of usucha was finished, with the sound of the kama persisting (albeit weakening) until the guests left the room.

While the host pauses here to inspect the fire, he also should also check and see that the initial arrangement of the other objects was not changed by the guests in any important way (and if it was, he should put things aright before proceeding further). Unlike today, when scolding and hypercriticality have become important activities by means of which the guests attempt to control each other (so their behavior conforms with the norms established by their particular school), in Rikyū’s time the guests were free to do pretty much whatever they liked, and they often picked up the various utensils to look at them closely when they first entered the room for the shoza, or the goza. (Indeed, Jōō actively encouraged them to open the door of the ji-fukuro, or the dōko*, so that they could look inside at that time, only asking that the last guest close the door again when they were done.) However, since the host will also use the positions of the various utensils to guide his hand when moving new objects onto the utensil mat, his faith in the initial arrangement should be confirmed before he begins doing anything else. __________ *Only in the case of the mizuya-dōko was this sort of thing strongly condemned by Rikyū (meaning that he began to assert the host’s authority only during the last two or three years of his life, since the first mizuya-dōko was the one he built in his Mozuno ko-yashiki [百舌鳥野小屋敷], which was completed in late 1588 or early 1589).

¹⁴The fusuma at the left of the temae-za had a similar function (indeed, it was the inspiration for) the door of the dōko. The original dōko was simply a locally made wooden box, with a shelf suspended across the middle, that was a wabi alternative to the imported mizusashi-dana that had been all the rage during Jōō’s middle period. Once the size of this tana had been fixed, it was only a matter of time before the opening, and the fusuma sliding in front of it, were reduced to being no larger than necessary. (This, of course, was only possible in a 4.5-mat room, where the dōko is some distance removed from the host’s entrance. In this particular two-mat setting, however, it would be difficult, since the host’s fusuma must slide behind the other so that he can get into and out of the room, meaning that the height of the two doors must be the same.)

¹⁵This is the way the idea is expressed in things like the Nampō Roku. What it actually means is that the foot of the chaire is located immediately to the right of the kane, so that the body of the chaire extends across the kane (in the case of the meibutsu chaire, and meibutsu chawan, the foot is usually one-third of the maximum diameter of the body); the back of the chaire should touch the front edge of the yū-yo, as if it were an invisible wall -- it is fairly easy to visually extend the front edge of the ro-buchi across to the mat to this point, allowing the host to gauge the width of the yū-yo without much difficulty*). ___________ *When it comes time to move the chawan beside the chaire, the back of the chaire is the visual guide that helps him determine how to orient the chawan.

¹⁶This is why the placement of the futaoki -- centered, as it is, in between the kane -- is so important: it shows the host where both the yin and the yang kane are located -- since the me on both sides of the futaoki represent those kane.

Rikyū said that the kane, especially in the wabi small room, should be recognized by counting the me on the mat*, and this is what he meant. __________ *In entry 50 of Book Seven of the Nampō Roku, it was alleged that Rikyū marked the kane on a sort of measuring tape, which he then hid in his futokoro, bringing it out when he was arranging the utensils on the mat at times when other people were not present; but this sort of action is contraindicated by his own words.

Using a measuring tape was a machi-shū practice that the machi-shū of the Edo period subsequently strove to validate by also putting the device into Rikyū’s hands. Rikyū’s point, however, was that the wabi setting does not demand such exactitude -- and, indeed, such excessive care is actually out of place there. It is better for the objects to be aligned with the me of the mat -- that is, so the side facing the guests is seen to be so aligned with the me (since placing objects so that their edges are in between me looks careless).

¹⁷The kane were derived from the shiki-shi [敷き紙], which accounts for some of the more arcane conventions associated with them -- such, as in the case of the endmost yang-kane, the idea that things are bound by them (objects placed on the shiki-shi were not suppoed to project beyond the edge) -- though this is only really a rule during the actual preparation of the tea. This is why the chaire must be wholly within the confines of the kane, since the purpose was that any tea that might fall off of the chaire* would be caught by the shiki-shi (which was originally used only once, and then discarded after use), rather than soiling the mat. ___________ *In the early days, the fear of contaminating the tea with lint meant that the chaire was rarely cleaned as diligently as today. As a result, it was not unheard of for tea to remain on the shoulder of the chaire, from where it could become dislodged, and so fall onto shiki-shi.

¹⁸This is done so he does not have to reach over the chaire and chawan with his right arm to access the handle of the hishaku, which would be wrong.

¹⁹The depression in the top of a futaoki is called a hi [樋]. In the early days its presence (or absence) was considered to be the most critical feature of any object that the host wanted to use as a futaoki.

²⁰Audibly striking the hishaku against the futaoki, and then dropping the handle so it bounces several times before coming to a rest* were machi-shū practices adamantly deplored by Rikyū -- not only because they were annoying, but because they could loosen the joint between the hishaku’s handle and its cup, resulting in the hishaku leaking during the temae. __________ *This kind of thing was viewed as a kind of “natural magic” by the Koreans of the middle ages (and even today), since the interval between taps decreases by exactly half with each repetition. Nevertheless, while this is so, it is out of place during the temae.

According to Rikyū, the cup should be gently rested on the futaoki, and then the handle should be gently lowered to the mat -- even in the most wabi setting.

²¹The outermost 5-bu on all four sides of the mat is yū-yo.

²²This was explained by Rikyū.

While Rikyū preferred to wear a kami-ko [紙子] (a kimono sewn from heavy paper treated with persimmon juice -- making it a dark brick-red color), many people of his period preferred to wear Korean-style clothing, consisting of a pair of loose pants tied at the ankles with strips of cloth, and secured around the waste by a narrow cloth belt, and a separate shirt that was tied at mid-chest with a sort of cord attached to the hems, both of which were made from undyed cloth (usually cotton or hemp, so they were between off-white and a pale beige).

In either case, a jittoku [十德] (a hip-length overgarment, sewn from black diaphanous silk, and traditionally worn by monks on formal occasions) was worn over the other garments before entering the tearoom.

²³This will likely strike the modern reader as an odd way of thinking about the matter, since the higher temae are invariably more complicated than the lower.

But this is a problem that arose (perhaps intentionally) during the Edo period. The original daisu temae (the so-called gokushin-temae [極眞手前]) was very simple, with all actions dictated only by necessity. Originally, only a mizusashi with a lid made of the same material as the body was permitted, and this lid was cleaned (with a damp chakin) when mizusashi was filled with water when the daisu was being prepared for use.

But when the lid of the seiji unryū-mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指] was broken during the attack on Yoshimasa’s storehouse (yet the body was left completely unscathed), Yoshimasa felt it was too much of a waste for such a precious object to be thrown away. So he had a wooden lid carved and painted, to resemble the original celadon lid. But it was found that dust clung to the lacquerware in a way that it never did to pottery or metalwork*, and this is what necessitated the wiping of the lid with the host’s fukusa every time it was going to be opened or closed (for fear that the dust would fall into the water, thereby contaminating the contents of the mizusashi).

The original usage was basic. The later modification was more complicated, because it took into account the peculiarities of the new lacquered lid. __________ *Or perhaps it might be better to say that the dust was simply more obvious on account of the material that was used. Nevertheless, because people were now more sensitive to this issue, a remedy had to be devised, and that is how the procedure came into being.

²⁴This angle of inclination is considered to be the most stable, and so less likely for the lid to slip and fall on the mat.

²⁵The original unryū-gama was the small unryū-gama, which holds three mizuya-bishaku of water* when full. However, that kama was really too small to be used over the ro (because, on account of the larger fire and greater heat, the water will boil away too quickly). Later a slightly larger version of this kama was cast for use in the ro (it holds four mizuya-bishaku of water), and this is what is now known as the medium unryū-gama (chū unryū-gama [中雲龍釜]). It was made for use with the ro, and in that setting it was supposed to be used in the same manner as the small unryū-gama was used on a furo. ___________ *A mizuya-bishaku -- this is a standardized measuring device -- holds 400 ml of water when filled to the rim (though in practice, it probably holds a little less when water is being poured into the kama). Consequently, the small unryū-gama holds around 1200 ml (when filled to the bottom of the kan-tsuki -- as was the original rule, though some of the modern schools have changed this), and the medium unryū-gama holds 1600 ml.

²⁶Originally the ring-handle was pinched between the thumb and first finger, as described here. The early ring-handle did not have a projecting leg (that keeps the ring from lying flat on the face of the lid). Consequently, the host had to lift the ring up with his fingernails (cultured persons of the upper classes, both men and women, effected long fingernails during that period*). As a result, holding it from the sides was the most logical way to do things.

Ring handles of this sort were first seen when old bronze mirrors came to be used as lids for kama during the late fifteenth century†.

These mirrors had a small knob, with a hole pierced through it, in the middle of the back side (the front side was polished as smooth as the technology of the day permitted, and then silvered); and a cord was threaded through that hole (which was then braided to make a handle by means of which the mirror could be held up -- this can be seen in the photo). When mirrors that had lost their silver were used as lids for kama, a cord was impractical (since it would get wet from the steam, and so get too hot to handle; cords of this sort were also susceptible of catching on fire).

After chanoyu came to be practiced by members of the samurai caste (whose physical training meant that they could not have excessively long fingernails), the little leg was added to the ring, to make catching hold of it easier.

Unfortunately, by the Edo period the machi-shū had forgotten how this was supposed to be done, and began putting their index finger through the ring (meaning that the ring will have to face toward the host at all times). Because the ring was now taking up the very part of the lid where the chakin would have to sit, Sōtan and his followers got into the habit of flipping the ring over, so that the side of the lid facing him was unobstructed. Of course this not infrequently resulted in the host forgetting to flip it back over before the end of the temae‡ -- which was another point about which the guests could gossip later. __________ *Long fingernails meant that they did not have to do any sort of manual labor.

The way of doing things like handling a writing brush always took into account the fact that the user might have long fingernails.

†This was because, since bronze was not yet being made in Japan, this was the only way to get lids of that metal for the iron kama that were being cast in Japan. (When these old mirrors lost their silver, there was no way to repair them, so they became useless. Using them as lids gave them a new purpose.)

‡If the ring was not flipped back, it would be very difficult to pick up the lid.

²⁷This is a special feature of the unryū-gama temae: as a result, while the amount of water in an ordinary kama decreases over the course of a temae, in the case of the unryū-gama, it slowly increases after each time hot water is used.

²⁸In Rikyū’s temae, the chakin was used as it was, to dry the bottom, lower side, and upper side of the interior of the bowl, then the front rim and back rim, when wiping the omo-chawan [主茶碗]; it was not draped over the side while the bowl was rotated -- that was done only when drying the kae-chawan [主茶碗] (since doing so is more dangerous).

Thus, in Rikyū’s temae, the chakin was immediately placed on top of the mizusashi, without any need to refold it.

²⁹The reason for adding water to the kama before preparing koicha during the “furo season” is this: once the ambient temperature begins to remain above freezing throughout the day and night, the strength of the stored tea begins to decrease each time the cha-tsubo is opened (as more and more of the volatile components evaporate when the jar is opened to the air). Therefore, the temperature of the water has to be lowered, otherwise the aromatics will dissipate completely before the bowl even reaches the guest.

We are not really so sensitive to this as were the people of Rikyū’s time, and the reason has to do with the way the matcha is processed. Even if you visit a tea plantation and are served a bowl prepared with freshly ground tea, the simple fact is that the machine-operated tea mills heat the leaves too much when they are being ground (the millstones become too hot to touch). Thus, so much of the flavor has already evaporated even before the powdered tea is sealed in its tin (the aroma of grinding tea spreads even out into the parking lot -- that is how much is lost).

In Rikyū’s day, the tea was ground in a hand mill, and when turned by hand (even by the young men of the household to whom this task was usually delegated), the stones do not even become warm to the touch. Thus the tea retained virtually its full strength and aroma until it was finally put into the chawan, and boiling water was poured over it.

Before Jōō created the irori, when the furo was used all year round, this simple rule could not be followed. Rather, from the beginning of winter in the Tenth Month (when the new jars of tea were cut open for the first time) until the end of the Second Month (around the end of March), fully boiling water was used to prepare koicha. From the beginning of the Third Month until the end of the Ninth Month, the kama was brought to a full boil (by closing the lid of the kama during the chasen-tōshi), and then its temperature was reduced appropriately by adding cold water to the kama before dipping out water to make the tea. While one hishaku of cold water would suffice for most of this time, from the end of the rainy season the host had to take especial care -- because even though the weather begins to cool from late August, the tea will have already been so damaged during the intense spell of heat, that it will have been all but ruined. Thus water no hotter than absolutely necessary should be used for the remainder of the year. (That is why Rikyū used a tsutsu-chawan during that season -- so he could cool the kama as much as possible, yet be assured that the tea would not cool further between his hands and those of the guest.)

Chanoyu, especially wabi no chanoyu (where the focus was supposed to be wholly on serving the best possible bowl of tea -- rather than amusing the guests with a room full of expensive utensils*), was a much more involved process than the modern, mechanical, mindless methodology might lead one to conclude. ___________ *Unfortunately, this idea has declined to the point where a majority of the practitioners of chanoyu today do not like koicha, and only endure it because of the utensils and food, despite the fact that most private gatherings take place in what would be described as a wabi small room (which includes the inakama 4.5-mat room).

³⁰According to Rikyū, hot water should be added to the chawan only once -- so the koicha could be offered to the guest as quickly as possible. Pausing to add more hot water (as Jōō did -- not only when preparing koicha, but when making usucha, too) will delay this, meaning that more of the volatile flavor components will have had the chance to evaporate before the bowl actually gets to the guest.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

love live and PuraOre! ~Pride of Orange~ share same seiyuu

soramaru voice nico and Ema Yoshiike

mimorin voice umi and Eri Yamanaka

ainya voice mari and Shino Ukita

mayuchi voice kasumi and Ayaka Mizusawa

#puraore! ~pride of orange~#love live!#love live#mayu sagara#mayuchi#ayaka mizusawa#kasumin#kasukasu#kasumi nakasu#mimorin#mimori suzuko#eri yamanaka#umi sonoda#aina suzuki#ainyan#ainya#mari ohara#shino ukita#soramaru#sora tokui#nico yazawa#ema yoshike#puraore#puraore! pride of orange

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

But I Like One Piece (20)

They all turn to stare at him.

“Dear? How do you know that?” Okaa-san says.

Otou-san shakes his head and sits down heavily on the stairs. “The manufacturer for those weapons is in Yukigakure. Just like the incriminating ryo left at the scene of that theft.”

Oh.

Oh sweet Merry.

She mutters, “Shika said—when we were talking about the theft, he said it had to be an inside job, because an outsider couldn’t know anything. But if they were like me—if they’d read the comic based on Konoha in their past life, they would know. They’d know almost everything even if they never set foot here.”

She swallows, throat suddenly dry. “If it was plot-relevant, then they’d know more about what was valuable and how it was defended than people who’d lived here their whole lives. They’d even know the weaknesses of the ninja sent after them, if those ninja were major characters.”

Otou-san nods. “And if he or she needed to finance the manufacture of those weapons, what could be easier than to steal something from here and sell it to another hidden village?”

She sits down heavily on the stairs.

Her heart’s pounding too fast. The side of her head is throbbing in time with the beat.

“Well.” Okaa-san coughs. “That’s mildly terrifying.”

She lets out a humorless chuckle at the understatement.

Horror wars with elation in her brain. Elation at the knowledge that she isn’t alone here.

Horror at the idea of someone knowing everything about this place and deciding to use that knowledge for their own gain. If robbing Konoha wasn’t low for them, would they stoop to manipulating Naruto, Sakura, Uchiha? To hurting them to get their way, change a narrative they don’t like?

“But Iruka-sensei said Yukigakure gave us those guns for less money than they gave them to other villages.” Naruto says suddenly. “Maybe that’s the not-Mayu’s way of making it up to us?”

“You think villains who would commit such an unyouthful action would be capable of feeling guilt?” Lee says doubtfully. “Shouldn’t we tell Gai-sensei about this?”

“We can.” Otou-san sighs. “But I’m not sure how helpful it would be. Nara-san said Yamanaka-san knew about the Yuki connection between both the theft and these “guns”. For all we know, the price reduction could be a concession negotiated between the Hokage and the thief, and we just have a morsel of knowledge about that deal which would endanger Mayu more than it would help the village.”

She fidgets, tracing the scar on her lower lip.

Lee’s brows are furrowed, his mouth pulled down in a frown.

Okaa-san reaches out and smooths a hand over his hair. “Why don’t we get Ichiraku’s and sleep on it? I think Sanji would agree we’ll all make better decisions with some ramen in our bellies.”

Naruto springs to his feet. “Yeah! Ramen’ll fix everything, believe it! C’mon, I’m hungry, let’s go, let’s go!”

It doesn’t quite fix everything, she reflects later as she descales and fillets the pike for the offerings tomorrow. There’s still another reincarnated person who robbed the village, had her father take the fall for their crime, and is now mass-producing the very weapon that killed her past self, which they can do next to nothing about.

But ramen smoothed out the crease in Lee’s brow when they all agreed it was better to tell Gai-sensei than not. It lightened the mood and made everything this day had thrown at them seem a little less important in light of the celebrations planned for tomorrow.

Their small garden is now even smaller thanks to the a large wooden structure that sits next to the back fence.

It’s a bit like a cross between a shed and a greenhouse, if it only had three walls and no doors or windows. The roof is curved and the walls are sturdy, to protect the shrines inside from the elements.

There’s a length of thick white rope fastened with red twine inside the front gable, which is meant to ensure that the shrines are protected from malicious spirits.

Each one of the shrines has a small building that is sealed automatically once the shrine has been assembled, keeping a small object for the deity to inhabit safely locked away from prying eyes. There’s a small recess before this structure, for offerings to be placed, and a little column that puts them above the eye level of a kneeling person.

They’d debated setting aside a space for the shrines in the living room inside the house, to ensure they could be protected and cared for. But she kept getting impulses of outside, of wind and rain, freedom, that eventually they decided it was better than keeping them cooped up inside.

Plus this way, Luffy can’t raid the fridge as easily.

She’s already found certain small cuts of cooked meat have gone missing. If he’s anything like the manga, then she’s not giving him the chance to clean out the entire fridge.

They’ve been working on constructing it and the shrines on weekends and in the mornings during training. According to Gai-sensei, it’s excellent practice for C-rank missions.

Now all that’s left is to paint the structure and the ten shrines housed within.

Working out what to set out as offerings for tomorrow had been a challenge and a half.

For the most part, the Strawhats can be grouped into small sections of what they will and won’t eat.

Nami and Chopper are fruit lovers. Sanji, Zoro, Brook and Usopp are partial to seafood. Luffy, Franky, and Robin are happy with beef and other land-based meats.

However, Zoro, Sanji and Brook like varieties of seafood that are difficult to get in Konoha— octopus, lobster and prawns are expensive and hard to find, while sea king meat just doesn’t exist here. At least Zoro is happy enough with a traditional plate-2-bowls meal with rice.

Robin prefers sandwiches, and she’s not quite sure if the burgers Franky loves fit into that criteria. Chopper can’t stand spicy or bitter foods, but Zoro and Robin dislike sweets.

She’s just thankful that Luffy, Nami Usopp, and Merry are so easy to feed. Pike’s one of the few fish that Konoha doesn’t need to import, so it and tangerines relatively inexpensive.

There’s no chance of combining all their preferences into one dish. Her head hurts just imagining the clash of flavors.

So she had to somehow come up with a way of creating a meal that would (hopefully) make each of the pirates she idolizes happy.

No pressure.

Chouji ended up being her savior in this respect.

And maybe Uchiha did as well, but only a teeny tiny bit.

She’d been brainstorming different versions of meals she could try making that would satisfy everyone, but kept coming up short.

The added tension from Sakura’s friendly-again-but-still-not-quite-sitting-back-at-their-table thing at this time wasn’t exactly helping her think either.

“I’ve got cola, coffee, tea, heck even sake, but still no idea on what to pair any of them with.” She complained, tapping her pencil against the list in front of her.

Chouji had leaned over, a thoughtful look on his face. “Why not make them lunchboxes? That way you can make lots of things in smaller amounts and personalize each lunchbox for each of them.”

“Hm. That is a good idea.” She gnawed on her lower lip. “Only downside is working out when I can cook what and how much time the preparation of each portion is going so everything in the bentos is relatively fresh for when it’s offered... how much d’you think eleven more lunchboxes would cost?”

She’d just begun sketching out lines for a tentative timetable when Uchiha complained, “Why do you think you’ve gotta do everything on your own?”

She looked up, a little offended. “I’m not praying for help with this, are you mad? That’d be like asking someone to bake their own birthday cake.”

“What Sasuke means,” Chouji intervened. “Is that we could always split the work three-ways between us, and bring it to your house on the day?”

She blinked. “You...you guys would help me like that?”

Chouji smiled, then made a squeak of surprise when she lunged over the table to hug him tightly. “Thank you.”

“I have lunchboxes to spare.” Uchiha drawled. “Plus someone’s got to make sure you don’t mess up.”

She had then let Chouji go so she could boot Uchiha in the shin.

As a result of this arrangement, when she wakes up on The Day, all she has to worry about is preparing the pasta for Sanji, Nami and Usopp’s lunchboxes after training with Gai-sensei.

She’s almost worried that her timining be a little delayed because Gai-sensei grabs her in a bone-creaking hug when she arrives at training and spends about three minutes weeping over how youthful she is.

He then makes them run fifty times around the village balancing the paint pots they’ll be using later to ensure that the paint is agitated enough “so its most YOUTHFUL colors will shine through!!”

They nearly lose the purple when Naruto fumbles slightly over a root.

She bolts down her food at breakfast.

She puts on more rice again in preparation for the sesame onigiri, and pulls out a pot to fill with water that’s set to boil and a pan to gently heat some oil on the stove.

She smashes a clove of garlic and drops it in when the oil has begun to smoke gently, deseeding and dicing up some chilis and tossing them in as well for flavor.

She can’t help her grin when the heady spicy-savory scent fills the air, finely chopping capers and anchovies to toss in once she’s fished out the smashed garlic.

The scent mellows somewhat when the diced pike hits the pan as well, and she pushes it around until the fish is almost-but-not-quite cooked through.

Then in with a generous glug of wine and the heat is turned down to a gentle simmer to let the alcohol cook off.

Just in time for the rice to have cooked and cooled enough to begin mixing with yellow and black sesame seeds and begin forming into ten onigiri.

They don’t have any fillings other than the sesame, because they’re designed to take the edge off the stronger flavors of the pasta (her) and the takoyaki (Chouji), as well as serve as a substitute for a sesame topped bun accompanying the hamburger steaks (Uchiha).

The others begin to arrive at around ten.

Sakura and the Harunos arrive first alongside Ino and her dad.

She shouts a hello as Naruto and Lee lead Ino and Sakura through the kitchen to the back garden, nails orange with peeled tangerine.

Ino darts forward and steals two slices, chortling in response to her indignant “Oi!” and passing one to Sakura, who grins as she nibbles on their way out.

Yamanaka-san is totally at home chatting with Gai-sensei and Otou-san, but he snickers when Nara-san immediately gravitates towards him when he arrives. Shikamaru gives her a nod as he follows the adults outside and she puts the pasta on to boil.

She’s set aside two extra tangerines for when Shino and his father arrive. After all, she, Chouji and Uchiha are making enough to feed eleven deities and many many people, so shouldn’t their insects also be able to eat as well?

Shino’s dad stares at her inscrutably when she explains her reasoning, before accepting the fruit with a nod and a “thank you” barely audible over a loud buzzing.

Shino shifts from one foot to the other during this exchange before gently tugging his father’s sleeve. It occurs to her as she drains the pot-full pasta and adds the sauce alongside a cup of boiling water to emulsify everything that this might be the closest she’s ever seen him to being embarrassed.

Chouji and his dad arrive as she’s sprinkling in some parsley as a finishing touch.

They’re both carrying huge containers full of takoyaki and cooked spring greens, and she spares a small moment to be envious of all the amazing things Chouji’s family can afford to do.

Then she launches Chouji another hug to thank him for all his help once he’s set his cargo down.

He squeaks like he did last time and Akimichi-san laughs loudly, for some reason.

Iruka-sensei and Uchiha arrive with eleven lunchboxes, two dogs, Kiba and his mum, and Hinata in tow.

Uchiha keeps sneaking what appear to be morsels of meat to Akamaru and Kuromaru.

There’s also a pale-eyed frowning boy who Iruka-sensei introduces as Hyuuga Neji, Hinata’s cousin who’d been sent along to act as her chaperone.

The boy sniffs disdainfully when they greet him and goes to stand in a corner of the garden near Mebuki, completely ignoring Lee when he waves to him.

She doesn’t think she likes Hinata’s cousin very much.

The lunchboxes Uchiha brought are black lacquer decorated with gold and red tomoe, much fancier than anything she’d been expecting.

When questioned, he just shrugs and says, “It’s just old stuff from New Year’s. It’s just taking up space at home, so it’s better off here.”

She knows better than to say anything like “sorry”, so she just pats his shoulder and says “No, that compartment’s too small for the onigiri, put it in this one.”

“That’s way too big, it looks tiny in that one.” Uchiha snaps, but with a bit less bite than usual.

Iruka-sensei looks mildly overwhelmed by all the people in the back garden. Okaa-san comes along, hands him a drink, pats his shoulder and says “They’re in my house,” in a sympathetic tone.

Iruka-sensei gives her a pitying look and knocks the sake back in one go.

Adults here can be weird.

Finally they’ve finished serving and she calls out “Food’s up!”

The adults come in to help take the larger platters of food outside, a huge plate of pasta, several smaller hamburger steaks in the style of what they’d call “sliders” in her world, and mound upon mound of takoyaki and spring greens and tangerines.

There’s a clamor outside as people begin getting their portions.

She, Chouji and Uchiha are each balancing either three or four lunchboxes per person as they take them outside.

Sakura is helping Kiba paint a pattern of cherry blossoms across Chopper’s already vibrantly pink shrine. Evidence of her handiwork on Robin’s shrine is clear is the decoration of swirling petals and the streaks of matching purple paint all over her forehead.

Ino and Naruto obviously have had a battle over the orange judging by the splashes on their hands and clothing. On the plus side Nami and Luffy’s shrines are looking particularly colorful.

Shikamaru and Hinata are splotched with green, light blue and black-and-white. Lee is smudged with brown, cyan and white paint and beaming proudly.

Shino has yellow paint on the end of his nose and is looking at the detailed illustrations of insects on the sides with pride.

The only shrines that aren’t quite done are Sanji’s, which has a blue overcoat but no decoration, and Zoro’s which doesn’t have half its roof painted yet.

“We were waiting,” Naruto says, holding out two buckets of green paint and blue respectively, “For you guys to add your bits.”

She beams at him.

Of course, Uchiha has to ruin it by immediately grabbing the green.

“What?” He says, offloading his three lunchboxes onto Kiba. “I’ll give it back once I’m finished with it.”

Ino rolls her eyes and shoulders her paintbrush, adding another orange splotch to her outfit. “Ugh. I’ll help Mayu-chan, it’s better to get it done quickly. Let’s go before the food gets cold.”

Orange, red, and yellow fish on the blue background are much more vibrant and eye-catching than green, though Uchiha does “help” by flicking the paintbrush at her while she’s distracted.

In thanks, she smears yellow on the back of his neck.

After the extra decorations are finished, Lee, Sakura and Kiba redistribute the lunchboxes to make their offerings.

The only problem is there’s eleven of them and ten lunchboxes.

“You all go ahead.” She steps back. “I’ll do the next bit.”

Each one of them place the pirate lunchboxes down in front of the shrines and step back.

For some reason, she feels like traditional prayers and chants appropriated from the sage guy won’t really be all that welcoming to them.

But then, what? What could help them feel at home at these shrines, so far from the sea?

Her gaze falls on Brook’s shrine.

Oh.

Oh, well it’s obvious when it’s put like that, isn’t it?

She just hopes she remembers the words correctly. She doesn’t want to butcher them on accident.

“Yohohoho, yohohoho~ Yohohoho, yohohoho~”

Her voice sounds frail and quiet, and she can feel everyone’s eyes on her. Still, she stumbles through the last two refrains of yohohoho’s to the first verse.

“Binksu no sake wo, todokei ni yuku yo, umikaze, kimakase, namimakase~ Shio no mukou de, yuhi wo sawagu, sora nya, wao kaku tori no uta~”

Naruto joins in on the next verse, singing along slightly out of tune and mixing up some of the words.

His cheeks look as flushed as hers feel, and it’s hard not to giggle when they catch each other’s eyes. Somehow they both manage to keep singing.

Gai-sensei and Lee boisterously shout DON alongside them as they join as well, Gai-sensei’s voice strong and sure, while Lee’s volume makes up for any deficiencies in wording. She almost can’t hear Okaa-san’s melodious voice and Otou-san’s decidedly tone-deaf one join in on the second set of Yohohoho’s over their noise.

Sakura and Ino’s voices are both high-pitched, but they carry the tune well enough. So does Kiba, though he’s pitching up to a falsetto for some reason. Hinata’s voice is soft, but she’s genuinely singing, unlike Shikamaru and Sasuke who’re mumbling through all the bits apart from the yohohoho’s. Shino is monotone if precise and enthusiastic, while Chouji has a surprising set of pipes on him.

Akamaru is just howling to the beat. And with that accompaniment, how could anyone stop themselves from singing along?

It feels like more people than could possibly fit into their house and garden are bellowing Bink’s Sake together by the time they’ve reached the third set of Yohohoho’s.

It can’t exactly be called “harmonious”. Everyone’s a little out of tune, a little off beat.

But the mixing of all the voices of her family and friends feels so right, it makes her voice stronger, lets her sing louder.

She opens her eyes and nearly chokes on the next note.

Hovering in front of the brightly painted shrines, slightly faded but gaining color and substance with every passing moment, They stand.

Merry appears in all her glory, as if in mid- sail. Brook is playing his violin, a foot tapping to the beat. Franky is winding up for his SUPA pose, grinning broadly. Robin is resting a hand on Chopper’s hat. Chopper himself is peeking at them the wrong way round from Robin’s leg.

Sanji’s tapping out his cigarette with a grin and giving a small salute. Usopp is waving to them, like a captain would to his 8,000 followers. Nami’s blowing a kiss as if to adoring fans.

Zoro...is climbing over the garden fence and jogging to take his place in front his shrine next to the others. Nami shoots him a Look while Luffy laughs at him, sitting in mid air and clapping his feet together.

The Captain of the Straw Hat Pirates then turns to her and gives her a wide grin.

She blinks away tears as he and his crew fade away with the last notes of the song.

The food in the lunchboxes is gone.

The food on Naruto’s plate is also gone.

In fact, all the food in the immediate vicinity appears to be gone.

It’s just that Naruto looks down at his plate and yells in indignation first.

She lets out a wet laugh. “Darn it Luffy.”

#my writing#naruto#one piece#but i like one piece#monkey d. luffy#naruto uzumaki#rock lee#nara shikamaru#sasuke uchiha#chouji akimichi#sakura haruno#ino yamanaka#hinata hyuga#kiba inuzuka#shino aburame#rookie 9#straw hat pirates#naruto oc#ketsugi mayu#ketsugi chie#ketsugi jirou#maito gai

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#First Love Story#Hatsukoi Signal#Favary#Asuka Kiyomiya#Sou Kagaya#Keiichi Minami#Arata Momose#Chitose Moriwaka#Shino Sakuraba#Asahi Nagamine#Mayu Handa#Akira Fujieda#meme#firstlovestory#fls

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

「 Wish Granting Sweet&Dream 」St@rt!!

The Platinum Audition Gacha has been updated with the limited「 Sweet&Dream」gacha set for February 2019!! The limited cards of this set features the usual theme of [ Valentines ]

The two new limited SSRs are of the COOL-type Haru Yuuki and the CUTE-type Mayu Sakuma. While the two new SRs feature the limited PASSION-type Shizuku Oikawa, and the COOL-type Shino Hiiragi

[ Note: The three limited cards will ONLY be available until February 8th 2019, 14.59 JST and may return after some time ]

#derestage#starlight stage#idolm@ster cinderella girls starlight stage#gacha#valentine 2019#haru yuuki#yuuki haru#mayu sakuma#sakuma mayu#shizuku oikawa#oikawa shizuku#shino hiiragi#hiiragi shino

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoujo Manga with Physical English releases List

The Manga series english title (The japanese title - the author (firstname lastname) /artist) extra info

13th Boy (SangEun Lee ) out of print? Has digital release as well

@ Full Moon (Sanami Matoh)

A Condition Called Love (Hananoi-kun to Koi no Yamai - Megumi Morino)

A Devil and Her Love Song (Akuma to Love Song - Miyoshi Toumori)

A Drunken Dream and Other Short Stories (Various)

A Sign of Affection (Yubisaki to Renren - suu Morishita)

Absolute Boyfriend (Zettai Kareshi - Yuu Watase)

Aishiteruze Baby ★★ (Youko Maki)

Alice 19th (Yuu Watase)

Alice in Murderland (Kakei no Alice - Kaori Yuki)

Alice in the Country of Hearts (Heart no kuni no Alice: Wonderful Wonder World (Author Quinrose art Soumei Hoshino)

Angel Sanctuary (Tenshi Kinryouku - Kaori Yuki)

Ani-Imo (Ani ga Imouto ga Ani de - Haruko Kurumatani)

Anonymous Noise (Fukumenkei Noise - Ryoco Fukuyama)

Antique Bakery (Seiyou Kottou Yougashiten - Fumi Yoshinaga)

Ao Haru Ride (Io Sakisaka)

Arisa (Natsumi Ando)

Aron’s Absurd Armada (Aronui Mujeokhamdae - MiSun Kim)

Ascendance of a Bookworm (Honzuki no Gekokujou - Author Miya Kazuki Artist Suzuka)

Baby & Me (Akachan to Boku - Marimo Ragawa)

Banana Fish (Akimi Yoshida)

Basara (Yumi Tamura) out of print/available digitally

Beast Master ( Kyousuke Motomi)

Beasts of Abigaile (Abigaile no Kemono-tachi - Ringo Naki)

Beauty Pop (Kiyoko Aria) out of print / available digitally

Beauty and the Beast of Paradise Lost (Kaori Yuki)

Beauty is the Beast (Bijo ga Yajuu - Tomo Matsumoto)

Black Bird (Kanoko Sakurakouji)

Black Rose Alice (Kuro Bara Alice - Setona Mizushiro) out of print/no digital release

Bloody Kiss (Kazuko Furumiya) out of print/no digital release

Bloody†Mary (Akaza Samamiya)

Bride of the Water God (Mi-Kyung Yoon) Out of print/not available digitally

Cardcaptor Sakura + Cardcaptor Sakura: Clear Card (CLAMP)

Ceres: Celestial Legend (Ayashi no Ceres - Yuu Watase)

Cheeky Brat (Namaikizakari - Mitsubachi Miyuki)

Children of the Whales (Kujira no Kora wa Sajou ni Utau - Abi Umeda)

Claudine (Riyoko Ikeda)

Clover (CLAMP)

Cowboy Bebop (Authors Shinichiro Watanabe/Hajime Yatate Art yutaka Nanten)

Crimson Hero (Beniiro Hero -Mitsuba Takanashi) out of print /never completed series/ no digital

Cross-Dressing Villainess Cecillia Sylvie (Akuyaku Reijou, Cecilia Sylvie wa Shinitakunai node Dansou suru Koto ni Shita - Athor Hiroro Akizakura Art Shino Akiyama) Originally a LN / also licenced

Cutie and the Beast (Pujo to Yajuu: JK ga Akuyaku Wrestler ni Koi Shita Hanashi - Yuhi Azumi)

D.N Angel (Yukiru Sugisaki) Out of print but can get series digitally

Daily Report About My Witch Senpai (Maka Mochida)

Dawn of the Arcana (Reimei no Arcana - Rei Touma)

Daytime Shooting Star (Hirunaka no Ryuusei - Mika Yamamori

Demon From Afar (liki no Ki - Kaori Yuki)

Demon Love Spell (Ayakashi Koi Emaki - Mayu Shinjou)

Dengeki Daisy (Kyousuke Motom)

Descendants of Darkness (Yami no Matsuei - Yoko Matsushita)

Disney manga series (quite a few are shoujo)

Doubt!! (Kaneyoshi Izumi)

Dragon★Girl (Toru Fujieda)

Dreamin’ Sun (Yumemiru Taiyou - Ichigo Takano)

Fairy Cube (Kaori Yuki)

Fiance of the Wizard (Mahoutsukai no Konyakusha - Author Syuri Nakamura Artist Masaki Kazuka / Keiko Sakano)

Flower in a Storm (Hana ni Arashi - Shigeyoshi Takagi)

Flower of Life (Fumi Yoshinaga)

Fluffy Fluffy Cinnamoroll (Fuwa♥Fuwa Cinnamon Yumi Tsukirino)

Fragments of Horror (Ma no Kakera - Junji Itou)

Fruits basket + Fruits basket Another (Natsuki Takaya)

Full Moon wo Sagashite (Arina Tanemura)

Fushigi Yuugi (Yuu Watase)

Gaba Kawa (Rie Takada)

Gakuen Alice (Tachibana Higuchi) Out of print /unfinished/no digital release

Ghost Hunt (Story/Art Shiho Inada Story Fuyumi Ono) Out of print/no digital release

God Child (Kaori Yuki)

Golden Japanesque: A Splendid Yokohama Romance (Kiniro Japanesque - Kaho Miyasaki)

Goong (So Hee Park) /out of print? Has digital copies

Grand Guignol Orchestra (Guignol Kyuutei Gakudan - Kaori Yuki)

Hana-Kimi (Hanazakari no Kimitachi e - Hisaya Nakajo)

Hatsu*Haru (Shizuki Fujisawa)

Heaven’s Will (Satoru Takamiya)

High School Debut (Koukou Debut - Kazune Kawahara)

Himeyuka & Rozione’s Story (Natsukashi Machi no Rozione - Sumomo Yumeka)

Honey Hunt (Miki Aihara)

Honey So Sweet (Amu Meguro)

Hot Gimmick (Miki Aihara)

I Am Here (Koko ni lru yo! - Ema Toyama)

I Was Reincarnated as the Villainess in an OtomeGame but the Boys Love me Anyway! (Akuyaku Reijou desu ga Kouryaku Taishou no Yousu ga Ijousugiru - Ataki / Sou Inaida)

I.O.N (Ariana Tanemura)

Idol Dreams (31☆Idreams - Arina Tanemura)

Ima Koi Now I am in Love (Ayuko Hatta)

I’m the Villainess, So I’m Taming the Final Boss (Akuyaku Reijou nanodo Last Boss wo Kattemimashita - Author Sarasa Nagase Art Anko Yuzu) originally LN; also translated

Immortal Rain (Meteor Methuselah - Kaori Ozaki)

Kageki Shojo!! (Kumiko Saiki)

Kaiju Girl Caramelise (Otome Kaijū Carameliser - Spica Aoki)

Kamikaze Girls (Shimotsuma Monogatari - Novala Takemoto/Yukio Kanesada)

Kamisama Kiss (Karisama Hajimemashita - Julietta Suzuki)

Karakuri Odette (Julietta Suzuki) Out of print? / no digital release

Kare Kano his and her circumstances (Masami Tsuda) out of print/no digital release

Karneval (Kaanibbaru - TouyaMikanagi)

Kase-san series (Hiromi Takashima)

Kigurumi Guardians (Lily Hoshino)

Kimi ni Todoke: From Me to You (Karuho Shiina)

Kiss Him, Not me (Watashi ga Motete Dousunda - Junko)

Kiss Me At the Stroke of Midnight (Gozen 0-ji, Kiss shi ni Kite yo - Rin Mikimoto)

Kiss of the Rose Princess (Barajou no Kiss - Aya Shouoto)

Kitchen Princess (Kitchen no Ohimesama - atsumi Ando; Story by Miyuki Kobayashi)

Kodocha: Sana's Stage (Kodomo no Omocha - Miho Obana )Out of print/ No digital release

Komomo Confiserie (Maki Minami)

Last Game (Shinobu Amano)

Laughing Under the Clouds (Donten ni Warau - KarakaraKemuri)

Lets Dance a Waltz (Waltz no Ojikan - Natsumi Ando)

Let’s Kiss in Secret Tomorrow (Ashita, Naisho no Kiss Shiyou - Uri Sugata)

Like a Butterfly (Hibi Chouchou - Suu Morishita

Liselotte & the Witch’s Forest (Liselotte to Majo no Mori - Natsuki Takaya) Story discontinued by Author

Living-room Matsunaga-san (Living no Matsunaga-san - Keiko Iwashita)

Love In Focus (Renzu-sou no Sankaku - Youko Nogiri)

Love me, Love me not (Omoi, Omoware, Furi, Furare - Io Sakisaka)

Love of Kill (Koroshi Ai - Fe)

Lovely★Complex (Aya Nakahara)

Lovesick Ellie (Koiwasurai no Ellie - Fujimomo)

L♥DK (Ayu Watanabe)

Magical Knight Rayearth (CLAMP)

Maid-sama (Kaichou wa Maid-sama! - Hiro Fujiwara)

Manga Dogs (GDGD-DOGS - Ema Toyama)

Manhwa Novella Collection

Marmalade Boy (Wataru Yoshizumi) Out of print/not digitally available

Mermaid Boys ( Sarachiyomi )

MeruPuri: Märchen☆Prince (Merupuri Matsuri hino)

Meteor Prince (Otome to Meteor Meca Tanaka)

Mint Chocolate (Mami Orikasa)

Missions of Love (Watashi ni xx Shinasai! - Ema Toyama)

Mistress Fortune (Zettai Kakusei Tenshi Mistress☆Fortune - Ariana Tanemura)

Moon Child (Tsuki no Ko - Reiko Shimizu) Out of print/not available digitally

My Girlfriend’s a Geek (Fijoshi Kanajo - By (author) Pentabu, By (artist) Rize Shinba) /originally a novel

My Girlfriend’s Child (Ano Ko no Kodomo - Mamoru Aoi)

My Little Monster (Tonari no Kaibutsu-kun - Robico)

My Love Mix-Up! (Kieta Hatsukoi - Author Wataru Hinekure Art Aruko)