#Samnite wars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Samnite Bronze Helmet and Neckguard, C. 450 BC

This imposing helmet is a unique hybrid of the Samnite-Chalcidian type.

The Samnites were an Italic people living in Samnium (see Wikipedia article map, below) in south-central Italy who fought several wars with the Roman Republic. They formed a confederation, consisting of four tribes: the Hirpini, Caudini, Caraceni, and Pentri. They were allied with Rome against the Gauls in 354 BC, but later became enemies of the Romans and were soon involved in a series of three wars (343–341, 327–304, and 298–290 BC) against the Romans. Despite a spectacular victory over the Romans at the Battle of the Caudine Forks (321 BC), the Samnites were eventually subjugated.

What was known as a ‘Samnite Gladiator’ appeared in Rome shortly after the defeat of Samnium in the 4th century BC, apparently adopted from the victory celebrations of Rome’s allies in Campania. By arming low-status gladiators in the manner of a defeated foe, Romans mocked the Samnites and appropriated martial elements of their culture.

Samnite soldiers 330s BC depicted in a tomb frieze in Nola, Southern Italy.

Collection: Naples Archaeological Museum

Source/Photo: Shonagon 2022-04-28

Wikipedia ref: Samnites

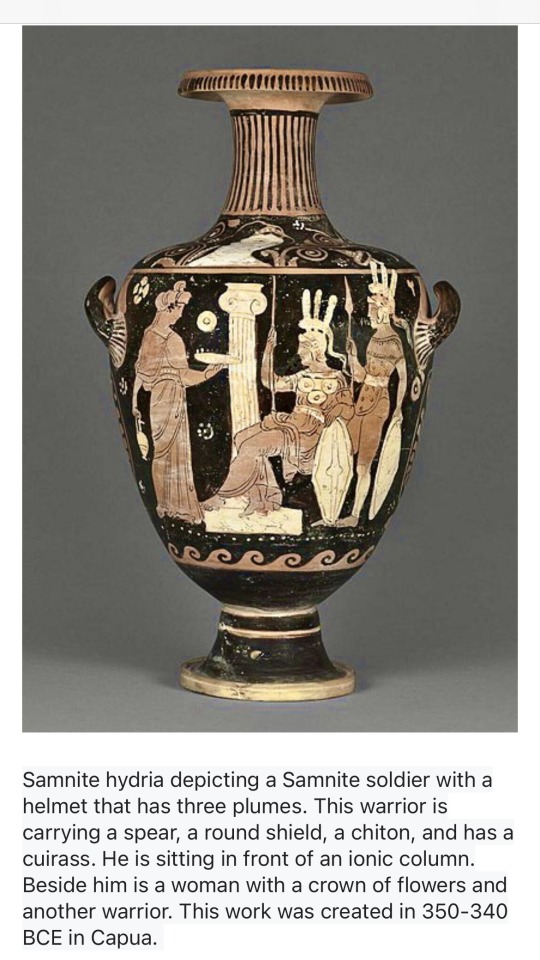

Collection: Louvre Museum, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities

Wikipedia ref: Samnites

#Samnites#Gladiator#Ancient body armour#Ancient helmet#Ancient neckguard#Ancient Romans#Samnite wars#Ancient Samnites#Antiquities#Stone antiquities#Metal antiquities#Bronze antiquities#Pottery & ceramic antiquities

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Equestrian

Portrait of an imagined ancient ancestor from the days of Roman Imperium. I began with a picture of myself at age 26 and a prompt that specified a figure with the darker skin, hair and eye color as well as the prominent nose and lips that characterize the men in my family.

As the branches of my family hail from Samnite country (Molise) as well as lands settled by Greeks and Carthaginians (Calabria and Sicily), I imagine this ancestor as someone of mixed Italian ethnicity with Roman citizenship--but not native a Roman. His ancestors--especially the Samnites--resisted Roman control for centuries but eventually fell under the hegemony of the growing Republic during the 3rd century BC and later gained citizenship after the Social War. As non-ethnic Romans of high plebeian or low patrician class, his people eventually gained status through military service as equestrians--a class whose status ranked above that of yeomen legionaries but below that of Roman knights.

Such distinctions would become unimportant during the chaos of the imperial era when military power became the sole criterion for assuming the purple. In 69 AD Vespasian would put an end to the power struggle following Nero's death, becoming the first emperor of equestrian class.

0 notes

Note

hi! history geek here! i don't know if this is a touchy subject but may i ask what type of a gladiator was felix?

• — 𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐥𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐅𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐱?

Good evening history geek, a fellow history geek runs this blog and have now jumped at the chance to talk about this topic. Seriously, if you ever want me to write deep dives you should give me historical angles.

First, a small history lesson and breakdown of when Felix was born for those who might be new here on the blog. This is all my own worldbuilding, mind you, not based on anything Stephenie has written.

Felix was born in 53BCE, a time of great upheaval for the Roman Republic. His formative years was plagued by civil war, all ending with the assassination of Julius Caesar when Felix was only nine years old. At this point Gladiatorial Combat had already been common for over fifty years within The Roman Republic.

However, our dear Felix did not end up in the pits before 35 BCE.

The thing about Gladiatorial Combat, was that it evolved over time; becoming a grander affair with every decade and more of a performance than anything else (Seriously, they filled the Colosseum with water from Tiber). In the early days, Romans would throw their enemies into battle with Free Romans in the pits, notably Gauls, Samnites and Thracians. These groups of people then inspired future Gladitor styles (through the ages there were about thirty or so).

Though it is a little early, I do headcanon Felix as an early iteration of The Murmillo despite the timeline being a little wonky. And though it is not entirely historically accurate, you probably recognise his type of Gladiator from this famous painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme

#Volturi Questionnaire#Felix Volturi#Please ask me more historical questions#Its my bread and butter#I love history#I am shaking at the thought of Gladiator 2

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Visitor's Guide to Herculaneum

In the first part of our new travel series devoted to the archaeological sites around the Bay of Naples, we shared some hints and tips as to how you can best prepare for your self-guided tour of Pompeii. In this second part, we look into the fascinating history of Pompeii's "little sister", the town of Herculaneum. Located just 17 kilometres (10 miles) to the north of its more famous neighbour, the archaeological site attracts fewer tourists, but the exceptional preservation of this Roman seaside town and the compactness of its exposed remains might even offer the visitor a more satisfying experience than Pompeii.

In Herculaneum, there are two-storey buildings, wooden furniture, traces of wooden stairways and balconies, luxurious patrician villas and even merchant shops with their original wooden shelves holding amphorae. Its destruction and preservation have made Herculaneum an extraordinary place which genuinely deserves the same renown as its famous neighbour.

A Roman Seaside Resort

Herculaneum was a small walled town located a short distance from the sea, west of Mount Vesuvius. As its name suggests, it was originally dedicated to the Greek god Herakles, who, according to the legend told by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (60 BCE), founded the city after his return from one of his twelve labours. The precise early history of Herculaneum is unclear, but the urban planning suggests that it may have been connected with the Greek colony settlements in the Naples area. According to Strabo (ca. 64 BCE - 24 CE), the city was subsequently inhabited by Oscans, then Etruscans and Pelasgians, and finally by Samnites in the 4th century BCE. The town remained a member of the Samnite league until it became a Roman municipium in 89 BCE during the Social War.

Herculaneum was then transformed into a purely Roman town and prospered as a quiet, secluded seaside resort for wealthy and distinguished Roman citizens who built beachfront residences with panoramic sea views. Unlike Pompeii, which was mostly a commercial city with ca. 12,000 inhabitants, Herculaneum was relatively modest in size. The overall surface enclosed by the walls was approximately 20 hectares (one-quarter of Pompeii), for a population of roughly 4,000 inhabitants. However small, the city is remarkable in terms of its evident wealth. The city had a richer artistic life than Pompeii and had more elaborate private buildings. Many houses of Herculaneum had two or three stories with atria and peristyles and were decorated with finely executed paintings and expensive furnishings.

Continue reading...

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Goddess Bellona of Warfare and Bloodlust

Attributes:

Warfare

Valor

Bloodlust

Madness in Battle (Frenzy)

Destruction

Devastation

Diplomacy

Symbols:

Torch

Whip

Bloodied Hands

Snakes/Serpants

Sword/Spear (Javelin)

Helmet

Shield

Blood

Festivals:

She was celebrated on June 3rd by her priests called Bellonarii to prepare blood sacrifices they would wound their arms and legs. On March 24th, the Days of Blood is performed (dies sanguines) which were pretty violent way of worship of the goddess which is explicit but all I say it involves flogging hence the whip symbolism. I am not going to go into detail I don’t even know that’s allowed but if you are curious please do take the time of research the rites for historical context. But please for all that is holy PLEASE DO NOT RENACT THESE RITES ITS VERY DANGEROUS AND OUTRIGHT EXTREMELY HORRIBLE if you are sensitive to self harming or blood then please do be careful when researching this topic. If you wish to worship Bellona THERE ARE OTHER ACCEPTABLE WAYS OF WORSHIPPING HER WITHOUT HARMING YOURSELF. I just needed to address that this post is just for education purposes.

General Information

Lady Bellona was the Roman goddess of Warfare and bloodlust. Indigenous to Italic tribes of Italian pennisula, she is said to be linked with the ancient Sabine Goddess Neiro (War goddess of Valor). Her name is derived from Duellum (War, Warfare) but also Bellum (Valor in war).

Her temple was established in Rome around 296 BCE during the war with Etruscans and Samnites by Appius Claudius. They hung shields on walls in the temple dedicated to the goddess. The temple was a place where foreign ambassadors would go for safe keeping, victorious generals to meet the seneators after a successful campaign.

To declare war on an enemy, the respected priest of diplomacy would throw a Javelin onto the opponent’s land as a declaration of open war. She had shrines and temples was worshipped throughout the Roman Empire however due to her violent nature she was not often worshipped openly or often. It is said that she is the Sister-Wife to Mars, she is identified with the war goddess Enyo. She went to war with Discordia, Furies, and Stife to put terror within her enemies.

#hellenic polytheism#paganism#witchcraft#hellenic pagan#hellenic worship#helpol#italian traditions#italian folk magic#roman polytheism#roman goddess

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

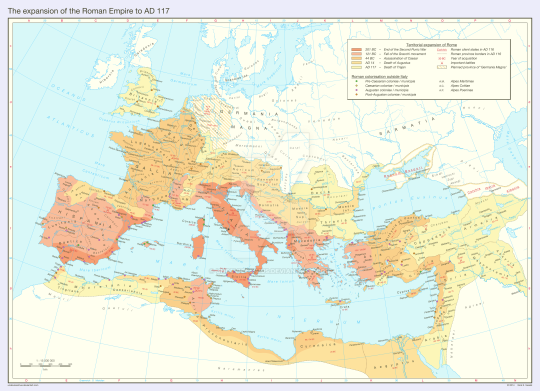

The expansion of the Roman Empire to AD 117.

by Undevicesimus

From its humble origins as a group of villages on the Tiber in the plains of Latium, Rome came to control one of the greatest empires in history, reaching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Tigris and from the North Sea to the Sahara Desert. Its extensive legacy continues to serve as a lowest common denominator not only for the nations and peoples within its erstwhile borders, but much of the modern world at large. Roman law is the foundation for present-day legal systems across the globe, the Latin language survives in the Romance languages spoken on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and beyond, Roman settlements developed into some of Europe’s most important cities and stood model for many others, Roman architecture left some of history’s finest manmade landmarks, Christianity – the Roman state religion from AD 395 – remains the world’s dominant faith and Rome continues to feature prominently in Western popular culture… Rome rose in a geographically favourable location: on the left bank of the Tiber, not too far from the sea but far enough inland to be able to control important trade routes in central Italy: southwest from the Apennines alongside the Tiber, and from Etruria southeast into Latium and Campania. In later ages, the Romans always had much to tell about the founding and early history of their city: tales about the twin brothers Romulus and Remus being raised by a she-wolf, the founding of Rome by Romulus on 21 April 753 BC and the reign of the Seven Kings (of which Romulus was the first). According to Roman accounts, the last King of Rome – Tarquinius Superbus – was expelled in 510 BC, after which the Roman aristocracy established a republic ruled by two annually elected magistrates (Latin: pl. consulis) with the support of the Senate (Latin: senatus), a council made up of the leaders of the most prominent Roman families. Often at odds with their neighbours, the Romans considered military service one of the greatest contributions common people could make to the state and the easiest way for a consul to gain both power and prestige by protecting the republic. The Romans booked their first major triumph by conquering the Etruscan city Veii in 396 BC and went on to defeat most of the Latin cities in central Italy by 338 BC, despite the Celtic sack of Rome in 387 BC. Throughout the second half of the fourth century BC, the republic expanded in two different ways: direct annexation of enemy territory and the creation of a complex system of alliances with the peoples and cities of Italy. Shortly after 300 BC, nearly all the peoples of Italy united to stop Roman expansion once and for all – among them the Samnites, Umbrians, Etruscans and Celts. Rome obliterated the coalition in the decisive Battle of Sentinum (295 BC) and thus became the strongest power in Italy. By 264 BC, Rome controlled the Italian peninsula up to the Po Valley and was powerful enough to challenge its principal rival in the western Mediterranean: Carthage. The First Punic War began when the Italic people of Messana called for Roman help against both Carthage and the Greeks of Syracuse, a request which was accepted surprisingly quickly. The Romans allied with Syracuse, conquered most of Sicily and narrowly defeated the Carthaginian navy at Mylae in 264 BC and Ecnomus in 256 BC – the largest naval battles of Antiquity. Roman fleets gained a decisive victory off the Aegates Islands in 241 BC, ending the war and forcing the Carthaginians to abandon Sicily. Taking advantage of Carthage’s internal troubles, Rome seized Sardinia and Corsica in 238 BC. Rome’s frustration at Carthage’s resurgence and subsequent conquests in Spain sparked the Second Punic War, in which the Carthaginian commander Hannibal crossed the Alps and invaded the Italian peninsula. The Romans suffered massive defeats at the Trebia in 218 BC, Lake Trasimene in 217 BC and most famously at Cannae in 216 BC where over 50,000 Romans were slain – the largest military loss in one day in any army until the First World War. However, Hannibal failed to press his advantage and continued an increasingly pointless campaign in Italy while the Romans conquered the Carthaginian territory in Spain and ultimately brought the war to Africa. Hannibal’s army made it back home but was decisively defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, securing Rome’s hard-fought victory in arguably the most important war in Roman history. Firmly in command of much of the western Mediterranean, Rome turned its attention eastwards to Greece. Less than fifty years after the Second Punic War, Rome had crushed the Macedonian kingdom – an erstwhile ally of Hannibal – and formally annexed the Greek city-states after the destruction of Corinth in 146 BC. That very same year, the Romans finished off the helpless Carthaginians in much the same way, burning the city of Carthage to the ground and annexing its remaining territory into the new province of Africa. With Carthage, Macedon and the Greek cities out of the way, Rome was free to deal with the Hellenic kingdoms in Asia Minor and the Middle East, the remnants of Alexander the Great’s empire. In 133 BC, Attalus III of Pergamum left his realm to Rome by testament, gaining the Romans their first foothold in Asia. As the Romans expanded their borders, the unrest back in Rome and Italy increased accordingly. The wars against Carthage and the Greeks had seriously crippled the Roman peasants whom abandoned their home to campaign for years in distant lands, only to come back and find their farmland turned into a wilderness. Many peasants were thus forced to sell their land at a ridiculously low price, causing the emergence of an impoverished proletarian mass in Rome and an agricultural elite in control of vast swathes of countryside. This in turn disrupted army recruitment, which heavily relied on middle class peasants who were able to afford their own arms and armour. Two possible solutions could remove this problem: a redistribution of the land so that the peasantry remained wealthy and large enough to be able to afford their military equipment and serve in the army, or else allowing the proletarian masses to enter military service and make the army into a professional body. However, both options would threaten the position of the Roman Senate: a powerful peasantry could press calls for more political influence and a professional army would bind soldiers’ loyalty to their commander instead of the Senate. The senatorial elite thus stubbornly clung to the existing institutions which were undermining the republic they wanted to uphold. More importantly, the Senate’s attitude and increasingly shaky position, in addition to the growing internal tensions, created a perfect climate for overly ambitious commanders seeking to turn military prestige gained abroad into political power back home. Roman successes on the frontline nevertheless continued: Pergamum was turned into the province of Asia in 129 BC, Roman forces sacked the city of Numantia in Spain that same year, the Balearic Islands were conquered in 123 BC, southern Gaul became the new province of Gallia Narbonensis in 121 BC and the Berber kingdom of Numidia was dealt a defeat in the Jughurtine War (112 – 106 BC). The latter conflict provided Gaius Marius the opportunity to reform his army without senatorial approval, allowing proletarians to enlist and creating a force of professional soldiers who were loyal to him before the Senate. Marius’ legions proved their efficiency at the Battles of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC and Vercellae in 101 BC, virtually annihilating the migratory invasions of the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones. Marius subsequently used his power and prestige to secure a land distribution for his victorious forces, thus setting a precedent: any successful commander with an army behind him could now manipulate the political theatre back in Rome. Marius was succeeded as Rome’s leading commander by Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who gained renown when Rome’s Italic allies – fed up with their unequal status – attempted to renounce their allegiance. Rome narrowly won the ensuing Social War (91 – 88 BC) and granted the Italic peoples full Roman citizenship. Sulla left for the east in 86 BC, where he drove back King Mithridates of Pontus, whom had sought to benefit from the Social War by invading Roman territories in Asia and Greece. Sulla marched on Rome itself in 82 BC, executed many of his political enemies in a bloody purge and passed reforms to strengthen the Senate before voluntarily stepping down in 79 BC. Sulla’s retirement and death one year later allowed his general Pompey to begin his own rise to prominence. Following his victory in the Sertorian War in 72 BC, Pompey eradicated piracy in the Mediterranean Sea in 67 BC and led a campaign against Rome’s remaining eastern enemies in 66 BC. Pompey drove Mithridates of Pontus to flight, annexed Pontic lands into the new province of Bithynia et Pontus and created the province of Cilicia in southern Asia Minor. He proceeded to destroy the crumbling Seleucid Empire and turned it into the new province of Syria in 64 BC, causing Armenia to surrender and become a vassal of Rome. Pompey’s legions then advanced south, took Jerusalem and turned the Hasmonean Kingdom in Judea into a Roman vassal as well. Upon his triumphant return to Rome in 61 BC, Pompey made the significant mistake of disbanding his army with the promise of a land distribution, which was refused by the Senate in an attempt to isolate him. Pompey then concluded a political alliance with the rich Marcus Licinius Crassus and a young, ambitious politician: Gaius Julius Caesar. The purpose of this political alliance – known in later times as the First Triumvirate – was to get Caesar elected as consul in 59 BC, so that he could arrange the land distribution for Pompey’s veterans. In return, Pompey would use his influence to make Caesar proconsul and thus give him the chance to levy his own legions and become a man of power in the Roman Republic. Crassus, the richest man in Rome, funded the election campaign and easily got Caesar elected as consul, after which Caesar secured Pompey’s land distribution. Everything went according to plan and Caesar was made proconsul of Gaul for five years, starting in 58 BC. In the following years, Caesar and his legions systematically conquered all of Gaul in a war which has been immortalised in the accounts of Caesar himself (‘Commentarii De Bello Gallico’). Despite fierce resistance and massive revolts led by the Gallic warlord Vercingetorix, the Gallic tribes proved unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the Romans and were all subdued or annihilated by 51 BC, leaving Caesar’s power and prestige at unprecedented heights. With Crassus having fallen at the Battle of Carrhae against the Parthians in 53 BC, Pompey was left to try and mediate between Caesar and the radicalised Roman proletariat on one side and the politically hard-pressed Senate on the other. However, Pompey had once been where Caesar was now – the champion of Rome – and ultimately chose to side with the Senate, realising his own greatness had become overshadowed by Caesar’s staggering military successes and popularity among the masses. When Caesar’s term as proconsul ended, the Senate demanded that he step down, disband his armies and return to Rome as a mere citizen. Though it was tradition for a Roman commander to do so, rendering Caesar theoretically immune from any senatorial prosecution, the existing political situation made such demands hard to meet. Caesar instead offered the Senate to extend his term as proconsul and leave him in command of two legions until he could be legally elected as consul again. When the Senate refused, Caesar responded by crossing the Rubicon – the northern border of Roman Italy which no Roman commander should cross with an army – and marched on Rome itself in 49 BC. Pompey and most of the senators fled to Dyrrhachium in Greece and assembled their forces while Caesar turned around and conducted a lightning campaign in Spain, defeating the legions loyal to Pompey at the Battle of Ilerda. Caesar crossed the Adriatic Sea in 48 BC, narrowly escaping defeat by Pompey at Dyrrhachium and retreating south. Pompey clumsily failed to press his advantage and his forces were in turn decisively defeated by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus on 6 June 48 BC. Pompey fled to Egypt in hopes of being granted sanctuary by the young king Ptolemy XIII, who instead had him assassinated in an attempt at pleasing Caesar, who was in pursuit. Ptolemy XIII was driven from power in favour of his older sister Cleopatra VII, with whom Caesar had a brief romance and his only known son, Caesarion. In the spring and summer of 47 BC, another lightning campaign was launched northwards through Syria and Cappadocia into Pontus, securing Caesar’s hold on Rome’s eastern reaches and decisively defeating the forces of Pharnaces II of Pontus, who had attempted to profit from Rome’s internal strife. Caesar invaded Africa in 46 BC and cleared Pompeian forces from the region at the Battles of Ruspina and Thapsus before returning to Spain and defeating the last resistance at the Battle of Munda in 45 BC. Caesar subsequently began transforming the Roman government from a republican one meant for a city-state to an imperial one meant for an empire. Major reforms were required to achieve this, many of which would be opposed by Caesar’s political enemies. This was a problem because several of these people enjoyed significant political influence and popular support (cf. Cicero) and while none of them could really challenge Caesar individually and publicly, collectively and secretly they could be a serious threat. To render his enemies politically impotent, Caesar consolidated his popularity among the Roman masses by passing reforms beneficial to the proletariat and enlarging the Senate to ensure his supporters had the upper hand. He then manipulated the Senate into granting him a number of legislative powers, most prominently the office of dictator for ten years, soon changed to dictator perpetuus. Though widely welcomed by the masses, Caesar’s reforms and legislative powers dismayed his political opponents, whom assembled a conspiracy to murder him and ‘liberate’ Rome. The conspirators, of whom Brutus and Cassius are the most famous, were successful and Caesar was brutally stabbed to death on 15 March 44 BC. Caesar’s death left a power vacuum which plunged the Roman world into yet another civil war. In his testament, Caesar adopted as his sole heir his grandnephew Gaius Octavius, henceforth known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Octavian, in English). Despite being only eighteen, Octavian quickly secured the support of Caesar’s legions and forced the Senate to grant him several legislative powers, including the consulship. In 43 BC, Octavian established a military dictatorship known as the Second Triumvirate with Caesar’s former generals Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus. Caesar’s assassins had meanwhile fled to the eastern provinces, where they assembled forces of their own and subsequently moved into Greece. Octavian and Antony in turn invaded Greece in 42 BC and defeated them at the Battles of Philippi. Octavian, Antony and Lepidus then divided the Roman world between them: Octavian would rule the west, Antony the east and Lepidus the south with Italy as a joint-ruled territory. However, Octavian soon proved himself a brilliant politician and strategist by quickly consolidating his hold on both the western provinces and Italy, smashing the Sicilian Revolt of Sextus Pompey (son of) in 36 BC and ousting Lepidus from the Triumvirate that same year. Meanwhile, Antony consolidated his position in the east but made the fatal mistake of becoming the lover of Cleopatra VII. In 32 BC, Octavian manipulated the Senate into a declaration of war upon Cleopatra’s realm, correctly expecting Antony would come to her aid. The two sides battled at Actium on 2 September 31 BC, resulting in a crushing victory for Octavian, despite Antony and Cleopatra escaping back to Egypt. Octavian crossed into Asia the following year and marched through Asia Minor, Syria and Judea into Egypt, subjugating the eastern territories along the way. On 1 August 30 BC, the forces of Octavian entered Alexandria. Both Antony and Cleopatra perished by their own hand, leaving Octavian as the undisputed master of the Roman world. Octavian assumed the title of Augustus in January 27 BC and officially restored the Roman Republic, although in reality he reduced it to little more than a facade for a new imperial regime. Thus began the era of the Principate, named after the constitutional framework which made Augustus and his successors princeps (first citizen), commonly referred to as ‘emperor’, and which would last approximately two centuries. Augustus nevertheless refrained from giving himself absolute power vested in a single title, instead subtly spreading imperial authority throughout the republican constitution while simultaneously relying on pure prestige. Thus he avoided stomping any senatorial toes too hard, remembering what had happened to Julius Caesar. Augustus and his successors drew most of their power from two republican offices. The title of tribunicia potestes ensured the emperor political immunity, veto rights in the Senate and the right to call meetings in both the Senate and the concilium plebis (people’s assembly). This gave the emperor the opportunity to present himself as the guardian of the empire and the Roman people, a significant ideological boost to his prestige. Secondly, the emperor held imperium proconsulare. Imperium implied the emperor’s governorship of the so-called imperial provinces, which were typically border provinces, provinces prone to revolt and/or exceptionally rich provinces. These provinces obviously required a major military presence, thereby securing the emperor’s command of most of the Roman legions. The title was proconsulare because the emperor enjoyed imperium even without being a consul. The emperor furthermore interfered in the affairs of the (non-imperial) senatorial provinces on a regular basis and gave literally every person in the empire the theoretical right to request his personal judgement in court cases. Roman religion was also brought under the emperor’s wings by means of him becoming pontifex maximus (supreme priest), a position of major ideological importance. On top of all this, the Senate frequently granted the emperor additional rights which enhanced his power even more: supervision over coinage, the right to declare war or conclude peace treaties, the right to grant Roman citizenship, control over Roman colonisation across the Mediterranean, etc. The emperor was thus the supreme administrator, commander, priest and judge of the empire – a de facto absolute ruler, but without actually being named as such. It is worth noting that Augustus and most of his immediate successors worked hard to play along in the empire’s republican theatre, which gradually faded as the centuries passed. The most important questions nonetheless remained the same for a long time after Augustus’ death in AD 14. Could the emperor keep himself in the Senate’s good graces by preserving the republican mask? Or did he choose an open conflict with the Senate by ruling all too autocratically? Even a de facto absolute ruler required the support and acceptance of the empire’s elite class, the lack of which could prove to be a serious obstacle to any imperial policies. The relationship between the emperor and the Senate was therefore of significant importance in maintaining the political work of Augustus, particularly under his immediate successors. The first four of these were Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero – the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Tiberius was chosen by Augustus as successor on account of his impressive military service and proved to be a capable (if gloomy) ruler, continuing along the political lines of Augustus and implementing financial policies which left the imperial treasuries in decent shape at his death in AD 37 and Caligula’s accession. Despite having suffered a harsh youth full of intrigues and plotting, Caligula quickly gained the respect of the Senate, the army and the people, making a hopeful entry into the Principate. Yet continuous personal setbacks turned Caligula bitter and autocratic, not to say tyrannical, causing him to hurl his imperial power head-first into the senatorial elite and any dissenting groups (most notably the Jews). After Caligula’s assassination in AD 41, the position of emperor fell to his uncle Claudius who, despite a strained relationship with the Senate, managed to play the republican charade well enough to implement further administrative reforms and successfully invade the British Isles to establish the province of Britannia from AD 43 onward. But the Roman drive for expansion had been somewhat tempered after Augustus’ consolidating conquests in Spain, along the Danube and in the east. The Romans had practically turned the Mediterranean Sea into their own internal sea (Mare Internum or Mare Nostrum) and thus switched to territorial consolidation rather than expansion. However, the former was still often accomplished by the latter as multiple vassal states (Judea, Cappadocia, Mauretania, Thrace etc.) were gradually annexed as new Roman provinces. Actual wars of aggression nevertheless ceased to be a main item on the Roman agenda and indeed, the policies of consolidation and pacification paved the way for a long period of internal peace and stability during the first and second centuries AD – the Pax Romana. This should not be idealised, though. On the local level, violence was often one of the few stable elements in the lives of the common people across the empire. Especially among the lowest ranks of society, crimes such as murder and thievery were the order of the day but were typically either ignored by the Roman authorities or answered with brute force. Moreover, the Romans focused on safeguarding cities and places of major strategic or economic importance and often cared little about maintaining order in the vast countryside. Unpleasant encounters with brigands, deserters or marauders were therefore likely for those who travelled long distances without an armed escort. At the empire’s frontiers, the Roman legions regularly fought skirmishes with their local enemies, most notably the Germanic tribes across the Rhine-Danube frontier and the Parthians across the Euphrates. Despite all this, the big picture of the Roman world in the first and second centuries AD is indeed one of lasting stability which could not be discredited so easily. The real threat to the Pax Romana existed not so much in local violence, shady neighbourhoods or frontier skirmishes but rather in the highest ranks of the imperial court. The lack of both dynastic and elective succession mechanisms had been the Principate’s weakest point from the outset and would be the cause of major internal turmoil on several occasions. Claudius’ successor Nero succeeded in provoking both the Senate and the army to such an extent that several provincial governors rose up in open revolt. The chaos surrounding Nero’s flight from Rome and death by his own hand plunged the empire into its first major succession crisis. If the emperor lost the respect and loyalty of both the Senate and the army, he could not choose a successor, giving senators and soldiers a free hand to appoint the persons they considered suitable to be the new emperor. This being the exact situation upon Nero’s death in AD 68, the result was nothing short of a new civil war. To further add to the catastrophe, the civil war of AD 68/69 (the Year of Four Emperors) allowed for two major uprisings to get out of hand – the Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine and the First Jewish-Roman War in Judea. Both of these were ultimately crushed with significant difficulties, especially in Judea where Jewish religious-nationalist sentiments capitalised on existing political and economic unrest. Though the Romans achieved victory with the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 and the expulsion of the Jews from the city, Judea would remain a hotbed for revolts until deep into the second century AD. The fact that major uprisings arose at the first sign of trouble within the empire might cause one to wonder about the true nature of the Pax Romana. Was it truly the strong internal stability it is popularly known to be? Or was it little more than a forced peace, continuously threatened by socio-economic and political discontent among the many different peoples under the Roman yoke? Though a bit of both, the answer definitely leans towards the former hypothesis. While the Pax Romana lasted, unrest within the empire remained limited to a few hotbeds with a history of resisting foreign conquerors. Besides the obvious example of the Jewish people in Judea, whose anti-Roman sentiments largely stemmed from their unique messianic doctrines, large-scale resistance against the Romans was scarce. It is true that the incorporation and Romanisation of unique societies near the empire’s northern frontiers led to severe socio-economic problems and subsequent uprisings, most notably Boudica’s Rebellion in Britain (AD 60 – 61) and the aforementioned Batavian Revolt near the mouths of the Rhine. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that the Pax Romana was strong enough to outlast a few pockets of rebellion and even a major succession crisis like the one of AD 68/69. The Year of the Four Emperors ultimately brought to power Vespasian, founder of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69 – 96) and architect of an intensified pacification policy throughout the empire. These policies were fruitful and strengthened the constitutional position of the emperor, not in the least owing to the fact that Vespasian’s sons and successors Titus and Domitian were as capable as their father. However, their skills did not prevent Titus and especially Domitian from bickering with the senatorial elite over the increasingly obvious monarchical powers of the emperor. In the case of the all too authoritarian Domitian, the conflict escalated again and despite his competent (if ruthless) statesmanship, Domitian was murdered in AD 96. A new civil war was prevented by diplomatic means: Nerva emerged as an acceptable emperor to both the Senate and the army, especially when he adopted the popular Trajan as his son and heir. Thus began the reign of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty (AD 96 – 192). Having succeeded Nerva in AD 98, Trajan once more steered the empire onto the path of aggressive expansion, leading the Roman legions across the Danube to crush the Dacians and establish the rich province of Dacia in AD 106. Subsequently, the Romans seized the initiative in the east, drove back the Parthians and advanced all the way to the Persian Gulf (Sinus Persicus). Trajan annexed Armenia in AD 114 and turned the conquered Parthian lands into the new provinces of Mesopotamia and Assyria in AD 116. Trajan died less than a year later on 9 August AD 117, his staggering military successes having brought the Roman Empire to its greatest extent ever…

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

i will delight myself by answering the asks as a reward for studying all the samnitic wars (which i will definitely do … i must … i feel the exam’s looming shadow hovering around me…)

#hey so would you like to know about the political system of the roman republic#i am going insane#thus spoke maia ♱

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancient Marble Statue of Hercules Discovered in Rome

ROME : Routine sewer repairs in an area in Rome, which was seeking a recognition from the Unesco as a World Heritage site, have led to the discovery of an ancient Roman-era marble statue of the mythical demigod Hercules.

Repair crews were called in after sewer pipes in the national park at the Appian Way collapsed, causing ditches and minor landslides.

The excavations, which reached a depth of 20 meters and as rules require in the Italian capital, were carried out with the presence of archaeologists.

The life-size marble statue found at the site is reported to be of Hercules, an ancient Roman demigod known as the protector of the weak.

The figure represented by the statue carried a club and had a lion's coat over his head, part of the iconography representing Hercules.

According to reports, the statue likely dates back to Rome's imperial period, which stretched from 27 BC to 476 AD.

The find recalls last November's discovery of two dozen well-preserved bronze statues beneath the foundations of thermal baths in Tuscany.

Those statues were 2, 300 years old, even older than the Hercules statue.

The marble statue of Hercules was broken during excavations but was otherwise well preserved.

This is the second time this year that the Appian Way makes international headlines.

On January 11, the Culture Minister formally backed the inclusion of the Appian Way on Unesco's World Heritage list.

It was the first time the Ministry ever backed a UNESCO candidacy directly.

The Appian Way is an ancient road that spans 550 km between Rome and the southern Italian city of Brindisi.

t was designed in 312 BC by statesman Appio Claudio Cieco. His goal was to build a road that quickly connected Rome to Capua for the movement of troops southwards during the Second Samnite War (326-304 BC).

Later on, the route was extended to Brindisi to directly connect with Greece, the East, and Egypt, for military expeditions, travel and trade.

It was the most famous route in the Roman era.

If the Appian Way becomes a Unesco site, the Appian Way will be the second longest such site after the Great Wall of China.

#Ancient Marble Statue of Hercules Discovered in Rome#the appian way#marble statue#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient rome#roman history#roman empire#roman art

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Samnites¹ were an ancient people who lived in south central Italia² (now Italy) & spoke the Oscan³ language.

They were an offshoot of the Sabines⁴ & were divided into 4 tribes.

Although former allies⁵ of the Romans, they later became bitter enemies & fought 3 wars against Republican⁶ Rome!

Afterwards, they continued to side against⁷ the Romans - in 4 more wars!!

But, they were finally assimilated & ceased to exist as a distinct folk⁸.

Notes:

1. Samnites is the Romans' name for a division of the Sabines. (See below.)

They were a warlike folk who fought the Samnite Wars against Rome for some 50 years!

The Romans even appropriated their style of fighting.

This kind of combat was so popular in the arenas, that it led to the creation of the Samnite gladiator - who fought with a short sword, greave (arm armor), a square shield & a helmet.

2. This was the Greek name for what is now Italy. Italia comes from Italos, a mythical king & 'founder' of that area.

3. Oscan is a dead tongue from the Indo-European language group.

Their written letters were adapted from the Etruscan alphabet once found in northern Italy.

4. The Sabines were a people that lived mostly in the south central mountains of Italia.

Sabine describes "the women of their tribes", who were loved for their honest wisdom.

It's thought to come from Latin Sabinus, "one's own kind?"

If so, it shares the same root word as the Sanskrit sabha, "community meeting."

5. After the sack of Rome in 390 BC, the Romans used diplomacy & military action to reconquer their lost territory.

In 353 BC, the Romans allied them- selves with the Samnites due to both nations fearing Etruscan & Gallic military powers.

Ten years later, the first Roman- Samnite War began.

It would be followed by 2 more, short Wars...

6. Yes, Rome wasn't always an empire!

Republican Rome existed from the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom in 509 BC & ended in 27 BC with the birth of the Roman Empire.

7. Even though they had been defeated, the Samnites would fight another 4 wars against Rome!!

Including allying themselves with Hannibal's army & his elephants!

8. They were basically absorbed thru marriage, family migrations & early child deaths...

But, their DNA still flows in modern Italian bloodlines.

End.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.19 (before 1930)

295 BC – The first temple to Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility, is dedicated by Quintus Fabius Maximus Gurges during the Third Samnite War. 43 BC – Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, later known as Augustus, compels the Roman Senate to elect him Consul. 947 – Abu Yazid, a Kharijite rebel leader, is defeated and killed in the Hodna Mountains in modern-day Algeria by Fatimid forces. 1153 – Baldwin III of Jerusalem takes control of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from his mother Melisende, and also captures Ascalon. 1458 – Pope Pius II is elected the 211th Pope. 1504 – In Ireland, the Hiberno-Norman de Burghs (Burkes) and Cambro-Norman Fitzgeralds fight in the Battle of Knockdoe. 1561 – Mary, Queen of Scots, aged 18, returns to Scotland after spending 13 years in France. 1604 – Eighty Years War: a besieging Dutch and English army led by Maurice of Orange forces the Spanish garrison of Sluis to capitulate. 1612 – The "Samlesbury witches", three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury, England, are put on trial, accused of practicing witchcraft, one of the most famous witch trials in British history. 1666 – Second Anglo-Dutch War: Rear Admiral Robert Holmes leads a raid on the Dutch island of Terschelling, destroying 150 merchant ships, an act later known as "Holmes's Bonfire". 1692 – Salem witch trials: In Salem, Province of Massachusetts Bay, five people, one woman and four men, including a clergyman, are executed after being convicted of witchcraft. 1745 – Prince Charles Edward Stuart raises his standard in Glenfinnan: The start of the Second Jacobite Rebellion, known as "the 45". 1745 – Ottoman–Persian War: In the Battle of Kars, the Ottoman army is routed by Persian forces led by Nader Shah. 1759 – Battle of Lagos: Naval battle during the Seven Years' War between Great Britain and France. 1772 – Gustav III of Sweden stages a coup d'état, in which he assumes power and enacts a new constitution that divides power between the Riksdag and the King. 1782 – American Revolutionary War: Battle of Blue Licks: The last major engagement of the war, almost ten months after the surrender of the British commander Charles Cornwallis following the Siege of Yorktown. 1812 – War of 1812: American frigate USS Constitution defeats the British frigate HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia, Canada earning the nickname "Old Ironsides". 1813 – Gervasio Antonio de Posadas joins Argentina's Second Triumvirate. 1839 – The French government announces that Louis Daguerre's photographic process is a gift "free to the world". 1848 – California Gold Rush: The New York Herald breaks the news to the East Coast of the United States of the gold rush in California (although the rush started in January). 1854 – The First Sioux War begins when United States Army soldiers kill Lakota chief Conquering Bear and in return are massacred. 1861 – First ascent of Weisshorn, fifth highest summit in the Alps. 1862 – Dakota War: During an uprising in Minnesota, Lakota warriors decide not to attack heavily defended Fort Ridgely and instead turn to the settlement of New Ulm, killing white settlers along the way. 1903 – The Transfiguration Uprising breaks out in East Thrace, resulting in the establishment of the Strandzha Commune. 1909 – The Indianapolis Motor Speedway opens for automobile racing. William Bourque and his mechanic are killed during the first day's events. 1920 – The Tambov Rebellion breaks out, in response to the Bolshevik policy of Prodrazvyorstka. 1927 – Patriarch Sergius of Moscow proclaims the declaration of loyalty of the Russian Orthodox Church to the Soviet Union.

1 note

·

View note

Text

losing my fucking marbles at wikipedia

what do you MEAN THAT AQUA APPIA WAS BUILT DURING THE FIRST SECOND AND THIRD SAMNITE WARS WHAT DO YOU MEAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAN

1 note

·

View note

Text

Rome The Unconquerable (pt2)

Hello readers! today we are going to cover some of the early roman successes that set them up to be the dominant power of the Mediterranean for hundreds of years, but also the roman spirit and view of the world.

here before i continue i should probably explain exactly who the romans were, precisely. in brief, they were a Latin tribe (Latin being a cultural group occupying the Italian peninsula in this period, not central Americans) that occupied a small area that mostly subsisted on farming and raiding in the early days until they began to have dreams of domination.

We return to this story in the samite wars (340-290 BCE)

here is the map! it illustrates rather easily how precisely the romans came to power. ignore everything after 290 for now but we will come to those later.

the samnite war was extremely hard going for the romans, as they were largely engaging their opponents in mountainous terrain. at this point they were using a formation called the phalanx which essentially was several columns of men as deep as was required by the specific needs of the commander, standing shoulder to shoulder all principally armed with spears. this formation at this point was thought to be unbreakable so long as the front line didn't turn and run, but unfortunately it was not manoeuvrable in the slightest, nor tactically flexible. the romans, ever pragmatic, decided they needed a more flexible formation or a "phalanx with joints," this became known as the maniple system.

the system was based around 3 lines of men in 10 groups of 2 centuries (60 men interestingly, not 100) with 2 centurions per each unit of 120. usually with a front line of javelin throwing infantry at the front to soften up the enemy with cavalry on the flanks. these men would stand 12 wide and 10 deep with their own maniple, with space between each group in the same line. the most senior centurion was the one who was the most decorated or experienced (so the leader of the primary century) then followed by the senior centurion of the second century.

the javelin infantry were called the velites and were mostly made up of romans who could not afford to become a full soldier, so they only carried short leaf bladed swords we might identify as a xiphos, a shield and wolfskin cloak. they would usually retreat to behind the lines of the main force once the enemy engaged in melee.

each row of the primary roman battle line was made up of different ages of soldier with varying levels of equipment. the first row was the hastati who were the poorest and youngest of the soldiers. they had bronze breastplates or light maille, a helmet, a short stabbing sword (still a xiphos at this time) a large oval or square shield called a scutum and a number of heavy javelins called pila which would be thrown either at the last moment during an enemy charge or at the end of a roman charge. they functioned as a meat grinder that the enemy would have to pass through before meeting the more experienced soldiers in the second line.

the second line was the wealthier older men called the principes. they were armed with heavy maille, a helmet (often adorned with feathers), bronze greaves, a xiphos (only in this period) a larger, stronger scutum shield and finally a couple of pila. these acted as the armoured line of the legion upon which the enemy would break unless things had gone very wrong indeed. in the even they did break, a third line was needed.

this third line was made up of wealthy middle aged and old men called the triarii. they were the heaviest troops on the field, armed with feathered helms, heavy maille, a large scutum, greaves, bracers, a xiphos and a spear. they were easily the most dangerous people on most any battlefield due to their experience and equipment. there was even a saying in Rome that goes "it has come to the triarii." to explain they were only ever typically used as a decisive force in case things had gone drastically wrong, so the saying meant that you would carry on to the bitter end at every cost.

how this formation worked is that the hastati would fight until tired, retreat behind the principes who would fight until tired, the retreat behind the now fresh hastati and so on, until you either won or had to engage the triarii and hopefully grind the enemy into the dirt.

this tactical change was vastly more manoeuvrable than the typical phalanx as well considerably more mobile, and lead to much of Rome's later military success along with another important factor, which was the roman spirit, which i will save for pt3 as this post has ended up being much longer than expected!

May your edges stay sharp and you points true!

Roma Invicta!

Ps. my new sword arrived today, expect a review in the next couple days, possibly tomorrow along with Rome pt3 assuming the weather is fine and i manage to do some tests and take photos!

#ancient rome#swords#academia#lord of the rings#sword#adventure#fencing#sword fighting#legionary#rome#armor#warrior#text post

0 notes

Text

Rome vs. Carthage in the First Punic War

The Rising Powers: Rome and Carthage In the mid-3rd century BCE, two great powers stood at the forefront of Mediterranean politics: Rome and Carthage. Rome, fresh from its victories over the Samnites and the Greek colonies of southern Italy, had solidified its control over the Italian peninsula. The Romans, driven by their unique blend of militarism and republican governance, were expanding…

0 notes

Text

The Roman Conquest of the Etruscans

Episode 21 The Etruscan World Falls Apart The Mysterious Etruscans Dr Steven L Tuck (2016) Film Review Rome conquered Etruria in gradual steps: 396 BC – Rome conquers Veiji 358-51 BC – brutal war between Rome an the other major Etruscan cities, followed by 40-year truce. 311 BC – Central Italy’s Samnites, Umbreites and Celts assist the Etruscan cities in resisting Roman military aggression. 294…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Roman empire aqueducts. (312 B.C.E)

The Roman empire was well known because this civilization gave us many contributions and there is one that we still use nowadays: The Roman aqueducts. In that time, they were different, but still had the same function to the aqueducts that we use in modern times.

In 312 BCE, the Roman Republic was in a state of war with the Samnites, Etruscans, and the Celts. The Appian Way, a road that connected Rome with Brindisium in the Adriatic Sea, was under construction. The Roman Republic was expanding its territory and had reached Tarentum.

The people who were in charge of the construction of the aqueducts were mostly skilled engineers, architects, and laborers who worked under the direction of high-ranking officials. But who ordered to create this system were three Roman emperors: Augustus, Caligula, and Trajan.

The aqueducts supplied fresh, clean water for baths, fountains, and drinking water for ordinary citizens, facilitated agricultural work, and it made indoor plumbing and running water available to those who could afford it and enabled a culture of public baths to permeate the Empire.

As we can see, the main purpose of the aqueducts was to supply fresh and clean water to the cities of the Roman empire, this could be considered a way of conserving water because it was water that had the best condition for consumption and that made it more valuable.

Roman aqueducts helped us to conserve water by offering us how to obtain clean and fresh water. This invention was not only beneficial to us but made us realize that it is a benefit to have access to water that is not contaminated.

0 notes

Text

SPQR- Mary Beard; Ch 4

4 Rome's Great Leap Forward

Besides the two consuls, there were a series of positions below that: praetors and quaestors. The senate was a permanent counsel of those that had previously held public office.

It was in the republican period between 500-300 BC that the roman institutions and a way of thinking about things were solidified. There were on the one hand series of violent conflicts between the hereditary patrician families, who had monopolized control of power, and the mass of citizens called plebeians, who had been completely excluded. Through time, the plebeians won the right, or freedom, to share power with the patricians. On the other hand, Rome was gradually gaining control over the Italian peninsula through a series of military victories.

Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, around 450 BC, rose to lead Rome to a victory, then gave up power and returned home to farm. Gaius Marcius Coriolanus was a war hero turned traitor around 490 BC.

The laws, or the twelve tables, were a series of around 80 clauses from the first written regulations. We can recognize that the scope and language reveals a still nascent legal and literate mind. It shows that by this point there was a need to codify law. They aren't nearly as grand as a comprehensive legal code, but they show a need for some sort of agreed upon ways of settling disputes.

The conflict of orders Shortly after the republic, plebeians started to grumble about their exclusion from political power. They asked why they should go fight in wars that would only line the pockets of patricians? Starting in 494 BC, they went on a series of strikes until they won concessions. Over the next centuries, they gained the political power they wanted. First, in 494 BC, was the tribuni plebis, to defend the interests of the plebs. Then they were granted a pleb assembly, but this time based not on wealth, but on geographic location.

By 287 BC, the decisions of this assembly were automatically binding over all Roman citizens. In 326BC, debt slavery had been outlawed. In 342 BC, consuls could be plebs.

In the mid 400s BC, the plebs were able to get the laws published. They had previously been held by the patricians, and weren't available to everyone. A panel of ten men (decemviri) were appointed to collect, draft, and publish the laws. The second decemviri collected more laws and published them, but this panel was much more conservative. The second set banished marriage between patrician and pleb.

The outside world: Veii and Rome In 396 BC, the Romans conquered the Veii, a town about 10 miles north of Rome. It seems rather to have been annexed, since shortly after, there were four new geographical tribes of Romans created. Livy mentions that the soldiers fighting against the Veii were paid from Roman taxes, marking a truly centralized organization of the state. In 390 BC however, Rome was invaded by "Gauls", who sacked the city.

The Romans versus Alexander the Great In 321 BC, the southern Italian Samnites trapped the Romans in a valley, and the Romans surrendered. But despite some of these defeats, between 390 BC and 295 BC, the Roman army grew dramatically. Veii was a small town 10 miles away. Sentinium in 295 BC was 200 miles away across the Appennine mountains. The results of Roman victories were increased Roman territory and Roman citizenship offered to the defeated.

Expansion, soldiers and citizens Despite Rome's reputation for belligerence, they probably weren't any more so than others of that time. Rome likely never thought of conquering territory in the way we think of it today. They probably saw the wars more as a change of relationship with the conquered peoples. There was really only one obligation Rome placed on conquered people: supply of men for the army. There were no occupying forces or administrative changes forced on the conquered. But the fact that their sons were now part of the Roman army effectively forged unspoken alliances, by forcing the locals to root for Rome while their sons were engaged in fighting. If Rome succeeded in the fight, their sons shared in the booty. If Rome was defeated, their sons were captured or killed. By around 300 BC, Rome had probably close to half a million soldiers. This made them nearly invincible.

But the more radical development was that the conquered peoples were offered citizenship in Rome. This had the unparalleled, in the ancient world, consequence of redefining what citizenship meant. Citizenship had previously meant living in a particular city. Now, citizenship was being defined as a political status regardless of race or geography. This model of citizenship would have enormous significance for Roman ideas about governance, political rights, ethnicity and nationhood.

Causes and Explanations There was a further consequence of the conflict of orders. It effectively replaced a government defined by birth with a one defined by wealth and achievement. But no achievement was more celebrated in Rome than military victory, and the desire of the new elite to achieve victory was an important factor in intensifying and encouraging warfare. It was also the power over increasingly far-flung peoples that drove many of the innovations that revolutionized life in Rome.

Finally, it was the size and logistics of managing such an empire that developed Roman management. Roman military expansion drove Roman sophistication.

0 notes