#Saint King Louis IX

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

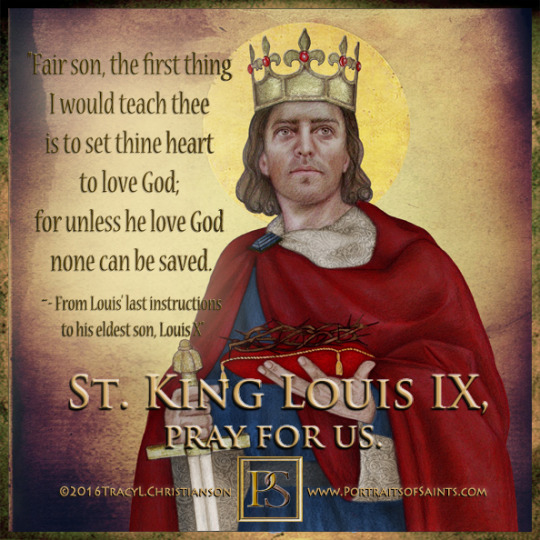

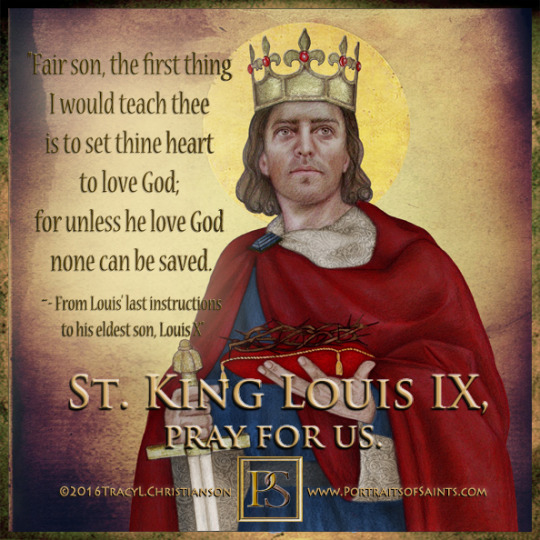

Saint King Louis IX of France 1214-1270 Feast day: August 25 Patronage: Architects and Monastic third orders

Saint Louis IX was crowned King of France at age 12 and reigned until his death. His mother ruled the kingdom until he reached maturity and instructed him in his education and religion. Louis married Margaret of Provence in 1234 and they had 11 children. He saw himself as a “Lieutenant of God on earth” even obtaining Christ's crown of thorns from Baldwin II, Latin emperor at Constantinople. He was an exemplary king, protecting the poor and clergy, founding hospitals and the Abbey of Royaumount and built Saint-Chapelle, an architectural gem. He led two crusades in 1238 and 1267, where he died of the plague.

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase here: (website)

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Taillebourg, 21 July 1242 by Eugène Delacroix

#battle of taillebourg#art#eugène delacroix#middle ages#medieval#history#knights#france#louis ix#saint louis#french#europe#saintonge war#saintes#versailles#capetian#angevin#england#english#bridge#henry iii#charente#river#kingdom of france#kingdom of england#alphonse of poitiers#hugh x of lusignan#richard of cornwall#mace#king

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Louis.

#saints#st louis#roi de france#vive le roi#capétiens#royaume de france#capetians#crusades#crusader#christianism#catholicism#kingdom of france#king of france#louis ix#st louis ix

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does Louis IX of France’s statue at Saint Chapelle not look like lord Farquaad? The square jaw, the hair, the height, the raised eyebrow?

Photo credits to me for the statue photo.

#sainte chapelle#france#paris#paris france#louis ix#was my first thought when I saw it#it’s also supposed to be the statue that most resembles that king#not a judgement just an observation#history#history memes#sort of a meme but also a real question#shrek franchise#shrek#shrek 2#shrek is love#shrek is life#lord farquaad#shrek the third#donkey shrek#shrek the musical#shrek forever after#shrek 5#princess fiona

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les geôles de Mansourah

Le silence pesant des geôles de Mansourah était troublé uniquement par le bruit de l'eau qui gouttait des murs humides. Louis IX, roi de France, se tenait dans l'ombre, les mains enchaînées, le regard perdu dans le vide. La bataille de Fariskur, qui avait eu lieu quelques jours plus tôt, avait été un désastre. Les cris des hommes, les cliquetis des armures, et le fracas des épées résonnaient encore dans son esprit, comme un écho douloureux d'une défaite qu'il n'aurait jamais imaginé subir.

Il se remémorait les visages de ses compagnons d'armes, ceux qui avaient combattu à ses côtés, ceux qui avaient cru en lui. La chaleur du soleil sur son visage, l'odeur de la terre battue, tout cela lui semblait si lointain. La réalité de sa situation le frappait avec une intensité dévastatrice. Il était roi, mais ici, dans cette prison, il n'était qu'un homme, un homme qui avait échoué.

« Pourquoi, Seigneur ? » murmura-t-il, sa voix brisée par l'émotion. « Pourquoi ai-je conduit mes hommes à la mort ? » Il ferma les yeux, se remémorant les derniers instants de la bataille. Les cris de ses soldats, la poussière soulevée par les chevaux, et le sang qui coulait à flots. Il avait voulu défendre la foi, protéger la Terre Sainte, mais à quel prix ?

Les murs de la prison semblaient se resserrer autour de lui, comme s'ils voulaient l'étouffer. Il se leva lentement, ses chaînes cliquetant à chaque mouvement. Il marcha d'un pas lourd, ses pensées tourbillonnantes dans son esprit. La défaite était amère, mais ce qui le rongeait le plus, c'était la culpabilité. Il avait promis à ses hommes qu'il les ramènerait sains et saufs, qu'il les mènerait à la victoire. Et maintenant, il se retrouvait ici, prisonnier, tandis que tant d'entre eux reposaient dans des tombes sans nom.

« Louis, » murmura-t-il à lui-même, se rappelant les mots de sa mère, Blanche de Castille. « Tu es un roi, mais avant tout, tu es un homme. » Il se laissa tomber à genoux, la tête entre les mains. Les larmes coulaient sur ses joues, mêlées à la poussière et à la sueur. « Que dois-je faire ? Comment puis-je me relever après cela ? »

Il se souvint des paroles de l'Écriture, des promesses de rédemption et de pardon. Mais dans ce moment de désespoir, ces mots semblaient vides. Comment pouvait-il espérer être pardonné alors qu'il avait échoué à protéger ceux qui lui avaient fait confiance ?

Un bruit de pas résonna dans le couloir sombre. Louis leva la tête, espérant voir un visage ami, mais c'était un garde qui s'approchait, l'air indiff��rent. Le garde le regarda avec un mélange de mépris et de curiosité. « Tu es un roi déchu, » dit-il d'une voix rauque. « Que fais-tu ici, à pleurer comme un enfant ? »

Louis se redressa, la fierté d'un roi refaisant surface malgré la douleur. « Je pleure pour mes hommes, pour ceux qui sont tombés à mes côtés. Je pleure pour la France, pour notre foi. »

Le garde haussait les épaules, visiblement peu touché par ses mots. « Les hommes meurent en guerre. C'est la nature des choses. »

« Peut-être, » répondit Louis, sa voix tremblante. « Mais chaque vie perdue est une tragédie. Chaque homme avait une famille, des rêves, des espoirs. Je ne peux pas les oublier. »

Le garde le fixa un moment, puis tourna les talons, laissant Louis seul avec ses pensées. Le roi se laissa tomber à nouveau sur le sol froid, la tête pleine de souvenirs. Il se remémora les rires autour du feu de camp, les chants des hommes avant la bataille, l'espoir qui brillait dans leurs yeux. Tout cela semblait maintenant si lointain.

« Seigneur, donne-moi la force, » murmura-t-il, levant les yeux vers le plafond sombre. « Donne-moi la force de porter ce fardeau. Je ne peux pas changer le passé, mais je peux apprendre de mes erreurs. Je peux me battre à nouveau. »

Il ferma les yeux, se concentrant sur sa foi. Il savait que sa mission n'était pas terminée. Même enchaîné dans cette prison, il pouvait encore prier, encore espérer. La lumière de l'aube viendrait un jour, et avec elle, une nouvelle chance de se battre pour ce qui était juste.

« Je ne suis pas un roi déchu, » se dit-il avec détermination. « Je suis un roi en attente de rédemption. »

Et dans cette obscurité, une lueur d'espoir commença à briller dans son cœur.

#history medieval#fanfic#Louis IX#Saint Louis#Louis IX of France#medieval history#king of france#roi de france#histoire de france#13th century

0 notes

Text

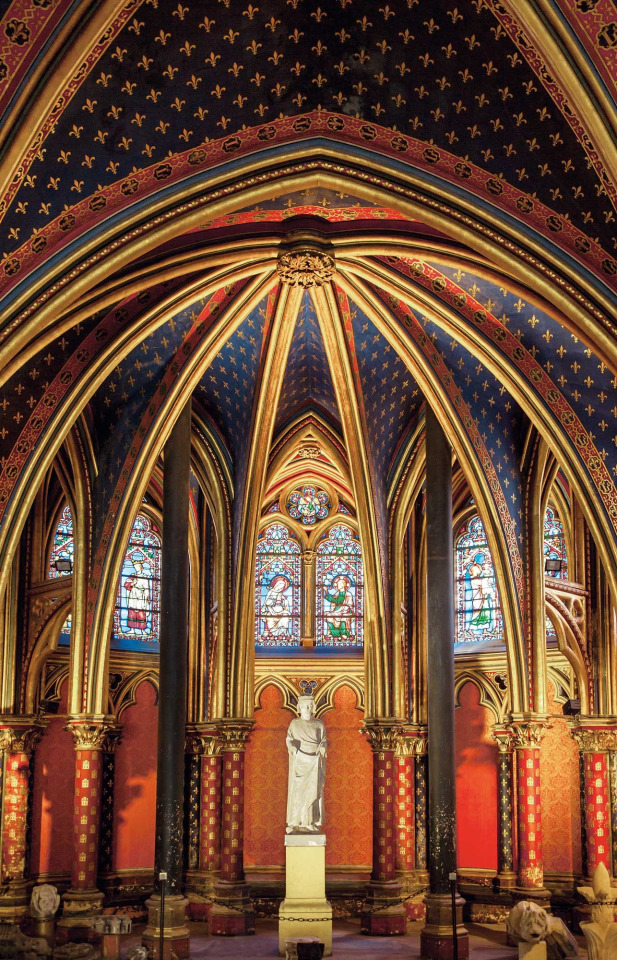

Sainte-Chappelle, Paris, France

Situated in the Ile-de-la-Cité, the Sainte-Chapelle is part of the Palais de la Cite, the residence of the royalty during the 10th to the 14th century.

It is one of the greatest examples of Gothic Architecture.

Built during 1242 and 1248, in accordance with the wishes of King Louis IX, it housed the collection of the relics of the Passion of Christ.

The 15 stained glass windows tell the story of mankind from Genesis to the Resurrection of Christ through 1.113 scenes.

The Rose Window above the entrance of the Upper Chapel depicts the Apocalypse of St. John.

Photo taken August 2024

#gothic architecture#gothic aesthetic#stained glass#chapel architecture#sainte chapelle#paris france#architecture photography#chapel stained glass#dark academia#light academia#medieval aesthetic#gothic

960 notes

·

View notes

Note

Yeah, that's true, but I didn't mention that because:

Agobard of Lyon wrote several treatises like The Insolence of the Jews and The Jewish Superstition in response to Louis the Pious's easing oppressive laws placed on the Jewish community.

King Louis IX burned 10,000 volumes worth of Talmudic manuscripts.

Ambrose of Milan was incredibly vocally against an edict that required a bishop to make restitution for a synagogue that was destroyed by a mob of Christians in his diocese.

John Chrysostom coined the term "Christ-killers" as an epithet for Jews, claimed that their souls were demon-infested, and said they were "for for slaughter."

And that's just what I can think of from the top of my head among officially canonized Catholic saints. It is absolutely true that what Luther says about Jewish people can be awful, but I should really scrub the muck tainting my own room before talking about the stench coming from the one next door.

can you elaborate on “how does anyone not read Luther’s personal and spiritual life and conclude…” ? I mean I knew he was foul-mouthed but ngl say more fam

Okay, the foul-mouthedness and the being really angry and vicious towards his ideological enemies isn't great, but it's not exactly damning either; I can point to a bunch of Catholic saints who were also prone to this kind of behavior. It's just something I personally find very distasteful, and am as embarrassed by Catholic saints who engage in that kind of behavior as I would be of Luther.

But really, the parts that bothered me were twofold.

First, Martin Luther's tendency to try to fill spiritual voids and depressions with physical sensations in his later years; he was a compulsive eater and drinker, for example - he used to call this stuffing himself "fasting," because he would eat to the point of finding disgust (and thus no pleasure) in it. (Which, you know, eating can be an ascetic activity for those who have eating-disorders, but when you're exposing yourself to physical sensations purely to stave off feelings of spiritual inadequacy....). In addition to the overeating, he similarly engaged in outbursts or wrath or sexual behavior in order to distract himself from these thoughts. Call it a major bias towards the monastic ideal if you must, but I am deeply mistrustful of this kind of coping mechanism where you distract yourself by indulging the body.

Second, Martin is on record saying that there were often times that he could not pray without also cursing and damning others. I think that an inability to praise God without also wishing death and destruction of your enemies in the same breath may indicate that something is deeply, deeply wrong. Especially when you combine these statements with other statements that indicate a chronic worry that maybe he wasn't actually right and might have been leading his followers into damnation anyway.

I don't like Luther. And there are aspects of his personality that I actively dislike. But having said that, don't let this post make you think my opinion of the man is just as negative as it was when I first started reading the book; there is some stuff about him and his thought that I liked. He's just also... a lot, and I think a lot of what he had to say or do was questionable.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part V the 1701 Winter Set(N⁰ 1881) :

The first entry of a new set of furniture for the brand-new bedchamber dates to November 1701, with the delivery by Lallié of a set made of richly embroidered crimson velvet. This set included three armchairs, twelve folding stools, two cushions used as footrests, a table covered by a cloth, and one fireplace screen, intended for use as winter decor [67]. It was assigned number 1881, which allows us to trace this set across time. Indeed, number 1881 reappears in the 1751 [68] inventory, then in the 1765 inventory [69], the 1776 [70] inventory, and finally in the 1785 inventory [71], before being mentioned one last time in 1785 on the occasion of its destruction [72], after 84 years of use. Despite its new inventory number, it was actually an update of an older velvet set, number 1504, originally delivered in April 1692 and mostly crafted at Saint-Cyr, as explained at the beginning of the November 1701 Garde-Meuble entry [73]. In later parts of the description, it is noted that the enhancement of the original embroidery took place at St. Joseph and was done by Mr. Cheury, probably following Lallié's instructions. In 1765, the set was further embellished, with Capin restoring the velvet [74] and Foliot adding a newly sculpted canopy top to the bed (see Part IX). This restoration resulted in several work reports that provide additional insights into the set.

4.1 The Velvet and Tapestry

As previously mentioned, the velvet used was based on an earlier delivery from 1692, which entered the Garde-Meuble in April 1692 under number 1504 and was described as:

“Grand set of crimson red velvet embroidered with a strong gold embroidery” [75].

While the rest of the entry mentions a canopy bed, two armchairs, twelve folding stools, and two footrest cushions, no reference to an alcove tapestry appears.

Interestingly, when Lallié delivered the updated version of the velvet in November 1701 for the King’s Bedchamber under number 1881, there was still no mention of an alcove tapestry [76]. Later, in September 1705, a new tapestry for the King’s bedchamber entered the Garde-Meuble under number 1989 [77].

The tapestry was said to have been made by Lebegne and consisted of two parts, each made up of eight pieces. This alcove tapestry would become the definitive one for the winter set, as tapestry 1989 and set 1881 are found together in various inventories from both the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI [78].

While the 1751 inventory is extremely vague, mentioning only “two pieces of crimson velvet tapestries” [79], the 1765 and 1785 inventories (which contain identical descriptions) provide a bit more detail: “two pieces of crimson velvet tapestries, 12 ft 4 in high, garnished at the top and bottom with gold fringes, with red canvas lining” [80].

One thing to emphasize about the alcove tapestry is its relative simplicity compared to the rest of the set. While set 1881 is described as a “rich velvet […] embroidered with gold,” no mention of gold embroidery appears in descriptions of alcove tapestry 1989. This lack of embroidery may have been balanced by the presence of the two alcove paintings that accompanied the winter decor. Furthermore, the tapestry is later listed under the velvet chapter of the 1752 inventory [81], while the richly embroidered furniture of set 1881 appears in the embroidery chapter [82].

4.2 The Bed

The main element of set 1881 was its state bed, with impressive dimensions (7 ft 4 in wide, 7 ft 8 in long, and 12 ft 3 in tall), a symbol of the monarch even more so than the throne itself. Its components were as follows:

The Headboard: Described as “very rich” without further detail. The later parts of the 1701 Garde-Meuble entry specify that, unlike many pieces in the set, it was entirely made from scratch and did not incorporate elements from set 1504 [83]. Two contemporary depictions of the bed with its headboard exist, allowing a better visualization of the piece, while depictions of the king’s bed from other residences can also provide a more complete picture.More details on the headboard appear in various reports from the 1765 restoration, though some alterations might have occurred at that time, potentially differing from its original 1701 state.Capin described the headboard in his 1765 work report as having the same type of embroidery as the headcloth, adorned with tinsel [clinquant]. He later specifies that “[the headboard is] adjusted in its wooden frame lined with cloth, garnished by its platband, assembled and tightly held in place [dressé avec grande sujession]” [84].Chasblier, who worked on the embroidery in 1765, described his work on the headboard as follows: “The headboard […] reembroidered, with tinsels and flourish [cliquant et fioritures], outlined [liseré] with gold lace” [85].The headboard does not appear in Bardon’s report, who restored the gilding of the set in 1765, possibly indicating that, even at that time, the headboard’s wooden frame was entirely covered by gold-embroidered cloth, with no gilding applied directly to the wood [86].

The Headcloth: The 1701 description merely acknowledges its presence [87], likely reusing the one from set 1504 [88]. In both instances, the Garde-Meuble entries contain no further details on the headcloth's ornamentation. However, the depiction of the bedchamber shown in fig. 19 includes a headcloth with large embroidery in its center.Capin’s 1765 report describes it as being made of crimson velvet (like the rest of the set) with embroidery matching that found on the headboard [89].Chasblier’s report aligns with Capin’s observation: “9 ft tall headcloth, entirely disassembled and reembroidered, with tinsels and flourish [cliquant et fioritures], outlined [liseré] with gold lace, and placed on a brand-new velvet cloth” [90].

The Valences: Their 1692 description goes no further than mentioning three outer valences and four inner ones, but the 1701 Garde-Meuble entry provides more detail, referring to them as “campanes” [91]. They were lined with taffeta, gold moire, and outlined with crimson red chenilles. This style of valence is consistent with the iconography of royal beds during the later years of the Sun King’s reign. The end of the 1701 entry clarifies their origin: they were brand new and not reused from the 1692 set [92]. It should be noted that campane-style ornaments became increasingly popular at that time and were not limited to canopy valences (see fig. 37).Descriptions of the valences from the 1765 reports are less relevant for discussing the room’s state during Louis XIV’s reign. As Chasblier explained, the new embroidery was entirely remade to match the newly added sculpted canopy [93].

The Bases: Described in 1701 as similar to the valences, with campane ornaments [94].

The Curtains: The 1701 entry mentions four curtains, two bonne graces, and four cantonières. Besides acknowledging their presence, the Garde-Meuble provides no specific details about their appearance. However, it does provide a few details about the lining of the bonne graces and cantonières, which were “red and gold brocade with fleur-de-lys” [95]. The same fabric was used around the bed columns, with the brocade in question being part of brocades 118, 130, and 101, which entered the Garde-Meuble in the late 1680s [96].

The Quilt: While previous descriptions are vague about the motifs in the velvet’s ornamentation, the quilt may offer more insight into the entire set. The 1701 entry specifies that it was “garnished […] with a braid of gold bouquets [bouquetterie], just like the one around the canopy [de meme qu’au tour de l’Imperial]” [97].Capin and Chasblier’s descriptions are consistent with previous reports, mentioning “tinsels and flourish,” though the report by the L’Heritier brothers, suppliers of silk and embroidery, adds additional key insights.

“26th September, following the order from the 8th to regarnish the square of the quilt from the King’s winter bed in the palace of Versailles.

9 aune 4 of gold braid from Paris, richly embroidered and garnished with sequins […] very rich, two inches wide […]

6 aune 4 of gold braid from Paris, two inches wide […]

16 pointy florets of Spain from Paris, with tinsel made of cloth to garnish two valances […]

17 aune of gold embroidery from Paris featuring festoons […]” [98].

These details add a more floral dimension to the previously opaque description of the embroidered ornaments on the velvet.

The Case Curtain: Made of 18 pieces of crimson gros de tours sewn together, with large and medium-sized gold fringes at the bottom and edges, hanging from a golden rod [99].

The Vases/Finials: Four in total (one at each corner), described in 1701 as “covered in said velvet and garnished with leaves of gold embroidery, with ornaments of bouquets [bouquetterie] and small gold braids” [100]. This description is reminiscent of the floral motifs mentioned on the quilt.Each finial was topped with a feather bouquet containing 138 large ostrich feathers and 34 narrower upper feathers [aigrettes] in total.

4.3 The Armchairs and stools

When set 1504 was delivered in 1692, two tall armchairs were included, featuring campane cloth ornaments around the bottom rest [101].

In November 1701, when Lallie sent the updated version of the set under number 1881, the armchairs were described alongside the twelve folding stools: “the three armchairs and twelve folding stools of said velvet with embroidery and campanes of embroidery like those of the bed, with slipcovers made of gros de Tours […], the wood sculpted and gilded.” One additional armchair was thus included in the new delivery, and it is also possible that the wooden structure of the armchairs was further embellished, as the wood is now described as “sculpted and gilded” [102].

The campane used to adorn the added armchair came not only from set 1504 but also from set 1505, as explained later in the entry.

Several details regarding the armchairs and stools of set 1881 are mentioned in reports from the 1765 restoration. Capin’s report specifies, however, that these changes were made “by augmentation” [103] and should thus be seen as enhancements not entirely faithful to their original state.

Although the 1751 inventory [104] mentions three armchairs from set 1881 used in winter, the 1765 inventory only refers to two, possibly because the third armchair was not fully ready when the inventory was approved.

4.4 The fire screen

Set 1504 from 1692 did not contain any fire screen, so its mention in set 1881 was a brand-new addition. The Garde-Meuble entry from November 1701 describes it as follows:

“The screen of said velvet and of different gold embroideries, depicting on one side [the god] Mercury and on the other side fleurets, the whole surrounded by an embroidery braid, and a large gold braid serving as clover, with wood sculpted and gilded” [105].

Later in the entry, we learn that the red velvet depicting Mercury used on one side of the screen came from an earlier delivery in May 1689. We also find that the other side of the screen, featuring the fleurets ornaments, used velvet from two stools belonging to set 1505, delivered in 1692 as an addition to set 1504 [106]. This confirms that the theme of the ornamentation on the velvet was primarily floral, as already suggested in the descriptions of the quilt and the canopy vases.

The first mention of this Mercury embroidery used on one side of the screen appears indeed on the 12th of May, 1689, where the Garde-Meuble diary notes:

“Monsieur Tourolle from Versailles received a piece of gold embroidery measuring 2 ft 10 inches tall by 2 ft 7 inches wide, which Madame de Montespan ordered from St. Joseph for the King, featuring on one side of the screen a winged figure standing and holding in one hand a laurel crown and in the other the attributes of the god Mercury, with one foot over a globe placed on a terrace and enclosed by a border of gold embroidery with leafage […] on a crimson velvet background” [107].

4.5 The Curtains

When delivered in 1701, set 1881 did not include any curtains for the bedchamber. The first mention of curtains used alongside this winter furnishing comes from the 1740 Versailles inventory [108], which lists three curtains made of crimson gros de Tours, “used both in winter and summer,” with inventory number 2202. These three curtains can be traced back to a delivery from May 1723 [109], the same date when Louis XV received a brand-new summer set for his bedchamber (see Part 8).

It would be implausible to imagine that King Louis XIV would have spent 14 winters in this bedchamber without ever needing curtains for the windows, whose primary function was to provide additional insulation, especially during cold nights. Thus, it would be reasonable to infer that the three curtains of red taffeta (each in three pieces) mentioned in the 1708 inventory alongside summer set 137 [110] were also used with the winter set, as the red color would have complemented the crimson velvet of the winter set far better than the silver and green of the summer counterpart.

The 1708 inventory also mentions three additional curtains of white damask used for each of the attic windows. Although no inventory number appears in the margin, their description and quantity seem similar to the three small damask curtains delivered in April 1702 under number 1883 [111].

In February of that year, the King ordered the installation of a pulley mechanism to facilitate the closing of the attic curtains [112].

4.6 The Tablecloth

Just like the fireplace screen, the tablecloth was first introduced with set 1881. It was made of the same crimson velvet with gold embroidery and campane ornaments at the bottom. All the pieces used in its construction were brand new, including the campane bottom ornaments, which were created from scratch [113].

The tablecloth is mentioned in the 1751 inventory [114] but is absent from the 1765 inventory [115]. Later inventories from 1775 [116] and 1785 [117] also do not mention it.

4.8 The Footrest Cushions

Two footrest cushions (one for each armchair) were included in the 1692 delivery of set 1504, though the description clearly states that, unlike the rest of the furniture, the velvet on the footrests was not embroidered [118]. In 1701, with the delivery of set 1881, their number remained the same, despite the addition of a third armchair. This detail offers insight into the purpose of the third armchair: as shown in fig. 17, the two armchairs were intended to be placed in the alcove on either side of the bed, while the third may have been used in front of a table (the one covered by the tablecloth) and thus may not have required a footrest.

The 1701 description notes that the footrests were finally embroidered: “of velvet and embroidery garnished around with a braid of gold bouquet with tassels at the corners” [119].

In 1765, Capin describes them as having campane ornaments all around, a detail not included in the previous description [120].

The Portieres Tapestry

When set 1881 was delivered in 1701, it did not include any tapestry for the doors. However, as early as 1703, Félibien mentions the presence of golden tapestries representing the four seasons [121]. The first detailed description of these tapestries in the bedchamber appears in the 1740 inventory [122], which notes that the doors were covered with portiere tapestries representing the four seasons, assigned inventory number 120, and describes them as follows:

“Four rich portiere tapestries of silk and wool, with added gold and silver, designed by Audran and made at the Gobelins manufacture, depicting the four seasons of the year under a portico on a gold background, represented by the figures of Venus, Ceres, Bacchus, and Saturn, surrounded on different backgrounds by garlands, festoons of flowers, birds, and animals, with signs and attributes appropriate for each season. The borders are blue with a bronze-colored mosaic and added gold, with small floral palms in the corners. Each measures two ells and 1/6 wide and three ells tall” [123].

The seasons were a recurring theme in the royal collection tapestries. Besides inventory number 120, numerous other season-themed tapestries are listed among the royal collections. In fact, as early as 1677, the Nouveau Mercure Galant mentions season-themed tapestries used by the Crown [124]. Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that the use of these tapestries alongside set 1881 predated 1740 and might indeed have been in place from the very beginning.

Several tapestries representing the seasons from the French royal collections remain in both public and private collections to this day.

[67] AN O1/3307

[68] AN O1/3454

[69] AN O1/3451

[70] AN O1/3457

[71] AN O1/3469

[72] See Part 10.2

[73] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 447 r⁰

[74] AN O1/3617

[75] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 439 v⁰

[76] Ibid

[77] AN O1/3308 f⁰ 14 r⁰

[78] AN O1/3453; AN O1/3454; AN O1/3451; AN O1/3459; AN O1/3469

[79] AN O1/3454 p.

[80] AN O1/3451; AN O1/3469

[81] AN O1/3446 p. 577

[82] Ibid p. 382-384

[83] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 447 r⁰

[84] AN O1/3617, Capin’s work report p.

[85] Ibid, Chasblier’s work report

[86] AN O1/3617, Chasblier’s work report

[87] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 439 v⁰

[88] AN O1/3306 f⁰ 202 v⁰

[89] Ibid, Capin’s work report p. 106

[90] Ibid, Chasblier’s work report

[91] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 r⁰

[92] Ibid f⁰ 441 r⁰

[93] AN O1/3617, Chasblier’s work report

[94] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 r⁰

[95] Ibid f⁰ 441 v⁰

[96] The 118 was delivered by Charlier on the 2nd of September 1688 (AN O1/3306 f⁰ 98 v⁰); the 130 delivered the next year.

[97] AN O1/3617, Chasblier’s work report

[98] Ibid, L’Heritier’s work report

[99] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 r⁰

[100] Ibid

[101] AN O1/3306 f⁰ 202 v⁰

[102] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 r⁰

[103] AN O1/3617, Capin’s work report p.

[104] AN O1/3454

[105] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 v⁰

[106] Ibid f⁰ 441 r⁰

[107] AN O1/3306 f⁰ 120 v⁰, the mention in the margin that the piece of embroidery was used for set 1881 clarifies any doubts regarding the connection between that entry and the fire screen of 1701.

[108] AN O1/3453

[109] AN O1/3309 f⁰ 353 v⁰

[110] AN O1/3445 f⁰ 4

[111] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 449 v⁰

[112] AN O1/1474 f⁰ 91 r⁰

[113] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 441 r⁰

[114] AN O1/3454 p. 2

[115] AN O1/3451 p. 8

[116] AN O1/3459

[117] AN O1/3461

[118] AN O1/3306 f⁰ 202 v⁰

[119] AN O1/3307 f⁰ 440 v⁰

[120] AN O1/3617, Capin’s work report p. 107

[121] Felibien, Description sommaire de Versailles ancienne et nouvelle. Avec des figures, 1703, p.344

[122] AN O1/3453 f⁰ 3

[123] AN O1/3345 f⁰ 113 v⁰-114 r⁰

[124] Le Nouveau Mercure Galant, juillet 1677, V, p. 68-73.

#sims4cc#sims 4 custom content#sims4#sims4rococo#ts4 historical#ts4cc#history#versailles#palace of versailles#historical research

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bishop's Medieval Coin Brooch Found in Field

A silver coin minted by a French bishop in the 13th Century and transformed into a gilded brooch has turned up in a field in north Norfolk.

The discovery was made by a metal detectorist in a rural area south of Cromer and it depicts Enguerrand of Crequi, Bishop of Cambrai from 1273 to 1293.

Coin expert Adrian Marsden said turning French coins into brooches was fashionable during this period because "no native coins were as large".

This one is unusual because it features the bishop's bearded face, while the now missing pin was placed on its back, he added.

From the Norman Conquest until the reign of Edward III, England's currency was made up of silver pennies.

So when the French king Louis IX, later Saint Louis, minted a large silver coin called a gros tournois, it became fashionable for prosperous people to turn them into brooches.

"Most of the coin brooches we have turning up are made from the gros tournois, as they're invariably the commonest big silver coin," said Dr Marsden, from the Norfolk Historic Environment Service. "And if you're having one of these silver coins made into a brooch, it's a substantial investment as they're worth two or three days' wages."

This find features a bearded Enguerrand, also known as Ingeramus de Crequy, wearing a bishop's mitre or hat.

Dr Marsden said this would not have happened in England.

"You do get bishops in charge of mints, but the coins would have had the king's head," he said.

"Generally, high-ranking people in France have more independence than in England - no English bishop would be allowed or dream of putting his head on a coin."

Little is written about Enguerrand, but whoever turned the coin into a brooch wanted to show his face, instead of the cross on its back to signal their piety.

A coroner will determine whether it is treasure and Norwich Castle Museum is interested in acquiring it.

By Katy Prickett.

#Bishop's Medieval Coin Brooch Found in Field#Bishop of Cambrai Enguerrand of Crequi#silver#silver coin#silver brooch#silver jewelry#ancient jewelry#ancient artifacts#metal detector#metal detecting finds#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#medieval ages#medieval art#ancient art#art history

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

What happened to Arno Victor Dorian after the events of Unity and Dead Kings ?

Following Elise's death at the end of Assassin's Creed Unity, Arno falls into a deep depression, finding little to live for.

He is also no longer part of the French Brotherhood.

In the DLC "Dead Kings", Arno is contacted by Marquis de Sade, who tasks him with finding a manuscript in the tomb of Louis IX.

Reluctantly, Arno agrees to this mission, and travels to Saint Denis to find the manuscript. During his search, Arno meets a young thief named Leon.

While the two work together, Leon's perspective on the world starts to break through Arno's grief, slowly showing him that there is more to live than the tragedies he's faced in his past.

What happened after Dead King is in the O.Bowden's novel.

I don't like his novels.

I will not summarise Oliver Bowden's novel.

But in the final chapters Arno found Elise's journal, and also Jennifer Scott Kenway's letters, where Elise requested him to seek unity for the two Orders.

It didn't go well obviously.

Arno rejoined the French assassins but we don't know when or how.

I have few theories:

Arno was extremely talented as an Assassin and his skills were too valuables

The Brotherhood forgive him after Germain's death and the rescue of the sword of Eden

The french assassins saw Napoleon's increasing influence over France and they need Arno to keep an eye on him. They became allies even though Napoleon's ideas were closer to those of the Templars.

Over the years, Arno earned the rank of Master Assassin and eventually the rank of Mentor (but he wasn't a bureaucrat as Mirabeau).

He took Leon under his wing and adopted him. At first Leon was wary of calling him "Father".

Arno presumably got married and had other children, as he is directly related to Callum Lynch, the protagonist of the Assassin's Creed movie*. Arno made a brief appearance in the movie.

He named one of his children Charles (or Charlotte) after his father and another François (or Françoise) after Monsieur de la Serre.

Did Arno and Ratonhnhaké:ton ever met ? (Reminder: Ratonhnhaké:ton is only twelve years older than Arno)

I think that Ratonhnhaké:ton became aware of Arno's actions during the French Revolution. They may have exchanged letters but they never met in person (and Connor had a big family to took care of and a very sweet daughter who was gifted by the spirits).

Did Arno find out who killed his father?

YES

He knew about Shay but he didn't hunt him down because revenge only leads to a bad path (and probably he thought that Shay was already dead which could be true).

Did Arno met Ethan Frye? Yes, it's possible due to the proximity of the French and english's brotherhood. Arno should be around 65/70 yo (if he was still alive).

We don't know when or how Arno died because Ubisoft never gave us answers (again)

I think that Arno passed away before the birth of the Frye twins, in 1847.

*I have a theory:

AC Unity should have been the gateway to a new present with Callum Lynch (and his ancestors like Aguilar de Nerha) as a new protagonist. But the movie has been a complete disaster so Ubisoft abandoned the idea.

#assassin's creed#assassin's creed unity#arno dorian#arno victor dorian#ac arno#ac unity#elise de la serre#ac léon#ubisoft#ubisoft games#ubisoft quebec#assassin's creed dead kings#ac movie#Callum Lynch#François de la Serre#Charles Dorian#pierre bellec#Jennifer Scott Kenway#shay patrick cormac#Ethan Frye#the frye twins#AC Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#ratonhnhakè:ton#connor kenway#arno x elise#Aguilar de Nerha#arno x callum

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint King Louis IX of France 1214-1270 Feast day: August 25 Patronage: Architects and Monastic third orders

Saint Louis IX was crowned King of France at age 12 and reigned until his death. His mother ruled the kingdom until he reached maturity and instructed him in his education and religion. Louis married Margaret of Provence in 1234 and they had 11 children. He saw himself as a “Lieutenant of God on earth” even obtaining Christ's crown of thorns from Baldwin II, Latin emperor at Constantinople. He was an exemplary king, protecting the poor and clergy, founding hospitals and the Abbey of Royaumount and built Saint-Chapelle, an architectural gem. He led two crusades in 1238 and 1267, where he died of the plague.

Prints, plaques & holy cards available for purchase here: (website)

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

St Louis before Damietta (Seventh Crusade)

by Gustave Doré

#st louis#saint louis#louis ix#king#france#seventh crusade#art#gustave doré#damietta#egypt#north africa#crusade#crusades#crusaders#crusader#medieval#middle ages#knights#knight#europe#european#history#history of the crusades#joseph francois michaud#christianity#christian#religion#religious#religious art

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

St. Louis, King of France.

#saints#st louis#king of france#crusades#crusader#kingdom of heaven#royaume de france#st louis ix#roi de france#vive le roi#capétiens#capetians

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sainte-Chapelle, the jewel of the Gothic.

Louis IX of France nicknamed the Saint, son of Blanca de Castilla (in turn daughter of Alfonso VIII and Eleanor de Plantagenet) and Louis VIII, has been considered the ideal of the medieval Christian monarch, a very devout king who dedicated his life to prayer, charity and asceticism... in addition to being the last European king to participate in the last two crusades: the Seventh between 1248 and 1254 and the Eighth in 1270, he took Saint Louis to Tunis and there he would die of the plague at the age of 56 and 40 of reign. In 1297 he will be canonized by Pope Boniface VIII.

His devotion and religiosity led him to acquire numerous relics and among them the coveted crown of thorns of Christ. Brought to France from Constantinople, Louis IX decided to organize a sacred place to keep and protect the holy collection. Thus in 1242 the construction of the Sainte-Chapelle would begin, which was consecrated in 1248. Little is known about the authorship of the chapel, it has been attributed to Pierre de Montreuil, master of the radiant Gothic and main architect of the reign of Saint Louis.

The enclosure was conceived as a reliquary or jewelry box where to deposit the precious and holy relics of the Passion of Christ. The chapel is 36 m long, 17 m wide and over 42 m high.

Its walls covered with precious stained glass windows, 15 in total, have representations, among other themes, of the Old Testament as well as the transfer of the crown of thorns to Paris.

These large openings filter the light, causing it to break down into different colors, symbolizing divine power and turning the place into a sacred and spiritual space. It is a large glass urn whose slender ribbed vaults, 20 m high, rise as if bringing us closer to God. In 1630 it went up in flames, a great fire destroyed it to a large extent and during the French Revolution its relics were stolen and many destroyed by the revolutionaries. Some were saved and are now kept in the treasury of Notre Dame Cathedral. In the S. XIX was the object of an extraordinary restoration, but preserving the spirit, fidelity and medieval beauty that it had in its origin.

186 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I really like your theories about undertaker. I am looking forward to new one!!!😭 but I have some random questions: what do you think about Undertaker’s human life? Was he a French (Breton) aristocracy, was he connected to French royalty and so on. Also, did Undertaker first work in French grim reaper department, does he hate British aristocracy? I will be very thankful for your answer

Hi, thank you so much for your ask :) I researched this stuff before starting this blog anyways, but it makes me very happy to see people enjoying my theories! Or even just reading them - I know they're a little bit on the crazy side in terms of detail and length 😅

Short answer - PTSD fuel, yes, yes, yes, no (mostly) 😄

Longer answer (+ discussion of theories to come) below the cut

What do you think about Undertaker's human life?

PTSD fuel man. PTSD fuel. War, Civil War, Plague, Mental Illness. Being born into privilege did not shield him from any of this.

I think he was close with his mom due to links I believe Yana has made to certain historical figures - though I would not be surprised if, keeping with the trend, she died when Undertaker was 15 in 1346. This is the same age that Vincent was when Claudia died.

Was he a French (Breton) aristocracy, was he connected to French royalty and so on.

Yes, I do think Undertaker is related by blood to the Dukes of Brittany and to the French Monarchy (honestly there are so many inter-marriages that saying one is also saying the other). I place particular importance on his connection with both the House of Capet, who ruled in France from 987 to 1328, and their direct descendants, the House of Valois, whose 13 kings ruled in France from 1328 (3 years before what I believe to be his birth year, 1331) to 1589 (3 centuries before the current setting of the manga, 1889).

I believe Kuroshitsuji and Undertaker's past was influenced by a series of historical fiction called The Accursed Kings which takes place in 14th century France (I haven't seen the Accursed Kings as inspiration discussed before). George R.R. Martin, author of A Song of Ice and Fire (Game of Thrones) has also cited these as an inspiration for his series. (I learned everything I know about tinfoil from the ASOIAF subreddit, iykyk). When I saw that George had used these books as inspiration as well I found it hilarious because I've always said that Yana Toboso's level of plotting and lore is on the same level as George R.R. Martin's, and that she doesn't get nearly enough credit for it - at least, not in the western world.

I think the hair within Undertaker's ring might belong to the Capetien King Louis IX, which would make the ring a reliquary as Louis IX was the only French King to be canonized as a saint (he is the patron saint of the French monarchy). I discussed reliquaries in my Rossignol theory post - and I will continue to discuss them in more detail in my future posts. The Capetien dynasty is definitely relevant, but given they're related to 75% of European nobility, it's a ton of names and dates for me to try and keep straight.

Those houses aren't the only ones; I think Yana has woven in references to the first king of the Franks, Clovis I, and his wife, Clotilde (patron saint of the lame 👀 i am excited to talk about this woman as an inspiration for Claudia's name!), as well as the emperor Charlemagne, as well the many houses that descended from the Capetians (I believe one house that ruled in Brittany relates back to a certain Viscount, which explains why Undertaker is protective of the bastard...).

Well, as I said, it's a lot of details to sort through!

Did Undertaker first work in the French grim reaper department?

Yes, I agree with that theory, but I don't have much to add to it at the moment. As I said, I think that he reaped King Louis XV's soul explains how he ended up with the Hirsch Aquamarine - I would imagine he's reaped many a French monarch's soul between 1366 and 1819.

Does Undertaker hate the British aristocracy?

Well... It's complicated; Undertaker is one complicated cat. But no, I don't think Undertaker hates the British aristocracy.

Now admittedly, he probably wasn't too fond of the British people as a whole after having been at war with them his entire life. I believe Undertaker was born March 25, 1331 and died at age 34 on January 28, 1366. The Hundred Years War between France and England broke out in 1337, when he was 6. The Breton War of Succession began in 1341 when Undertaker was 10, and this was in itself a proxy war between France and England. France backed the female claimant to the Duchy of Brittany of the House of Blois, and England backed the male claimant of the House of Montfort.

But not being fond of the British people or British aristocrats does not equate to hating them - and then, of course, he met Claudia. I really believe he is (in his own mind, at least) devoted to Claudia and her memory, and to the last remaining Phantomhive. Of course, she'd probably be rolling in her grave if she knew the wacky shit he's been up to in her absence.

Anyways - ultimately I think the sin that Undertaker finds most despicable is greed, especially when it's at the expense of your own people. He isn't prejudiced against a particular group of people, but all who embody this sin.

Anti-capitalist king 👑

This goes back to a lot of things; my theory about "Holy Monday", Jesus Christ, the novel Ivanhoe, the novels of The Accursed Kings, the Knights Templar, King Philip IV, King Louis IX, The Irish Potato Famine, even The Tower Bridge. I think it would make a lot of sense for Undertaker to despise greed given he blames it for the horrors of his past. And I believe there are hints in the manga that for all their less savoury aspects, Claudia, Vincent, and O!Ciel are not greedy in the way Undertaker finds distasteful... but R!Ciel might be.

Thanks again for reading 🥰 and thank you for the ask!

#ask#i hope you don't mind me publishing this!#undertaker theory#kinda#black butler#kuroshitsuji#anti-capitalist king#i've called him that as a joke for a while but now it's actually kinda serious lmao#undertaker

13 notes

·

View notes