#Rukhshana

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

unafraid

Fandom: Ciconia: When They Cry

Rating: General Audiences

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Relationships: Sujatha/Rukhshana

Summary: Suparna’s training session is cancelled for the day because of a sudden storm, which Sujatha is absolutely not scared of, and that might or might not creates tensions with her girlfriend.

[Femslash February 2023 Day 3: Storm]

______________________________________________________________

Link on Archive of Our Own

______________________________________________________________

Notes: Hi here’s your annual Ciconia FemFeb fic from me! Yes you’ll get one until Ryukishi finally decide to release Phase 2. Anyway this is very late but it’s meant to be for Day 3: Storm, from those prompts.

I don’t know why, but at first I didn’t want to write any Sujatha/Rukhshana piece for FemFeb; not because I don’t like them but for some reason I really wanted to write a proper one-shot for them and not something based on a random prompt. But technically speaking they’re still one of the most obvious F/F ships of the VN so far, so I thought they were just the next obvious choice, especially given I’d already done Lingji/Aysha and Valentina/Maricarmen before. So yeah it’s just a small cute fluffy thing without a lot of substance.

Given it’s going to mark the third year since I’ve last read the VN I admit I forgot a lot of stuff about the characters, so I really don’t feel confident in how I characterized them here. Especially Rukhshana. (And I know it *seems* like Phase 1 implied she was a CPP as well like Miyao, but we don’t know much about that yet so I didn’t want to touch on the topic). So I hope they don’t feel too off.

Also, it’s a small detail in the fic but — if you’re like me and haven’t played the game in a while, I feel the need to mention that COU is the one country that has ‘traditional’ families; so I’m assuming Sujatha, Rukhshana and Andry probably have ‘normal’ parents like Lingji & co.

Now on a small caveat I have that made me hesitate while writing this fic: I realized that, obviously we don’t know anything about whether or not Sujatha is religious, but as she is from India and that we’re told the COU is very traditional, IF she is religious then she would probably follow one of the many Hinduism faiths; however, on the other hand, given Rukhshana is from Saudi Arabia and is clearly wearing a hijab, she has to be Muslim. Queerness aside, I know interfaith relationships can be a bit of touchy topic in Islam; some might tolerate it and others do not (one of my non-Muslim cousin dated a Muslim woman for three years, but he had to convert when they got married), and it would be especially so for a Saudi girl given ‘dating’ in the Western sense in general is frowned upon over there. Not sure how things would be in Ciconia’s futuristic, post-World War III universe, but it did seem to imply Saudi Arabia is still very traditional similarly to how it is in our world because of how they mention there were issues with Rukhshana, as a girl, joining the team while there was a boy in it. The VN is very scarce when it comes to giving details about the religious/cultural practices of the characters (hell even the hijabi girls are never actually called ‘Muslims’ in-universe), so I can’t say how pious Rukhshana must be or how important it would be for her to only get together with someone who’s Muslim. So the way I see it in this fic, is that she must probably be respectful of the faith and wouldn’t marry a non-Muslim person usually, but she can give herself some leeway if this is with someone she really loves (and that the other person can potentially convert)? (And well, Muslim communities exists in India too so I suppose you can headcanon Sujatha as such as well). I dunno, maybe I’m just overthinking about it; and of course like I said this is just a short fluff piece and not some exploration of any of these topics anyway lol, but I am not Muslim myself, so I’d understand if any actual Muslim people don’t like it or take issue with this.

All this aside, there’s no spoilers (except for like, the start of Phase 1 I guess) or content warnings except for the inevitable vague mentions of war/child soldiers.

______________________________________________________________

Sujatha was absolutely not scared.

She had sworn to herself, from a very young age, to never become a person who got scared.

Fear was only meant for the common people. Fear was for normal girls; ones who didn’t have any responsibility, who weren’t soldiers, who weren’t part of the elite of the COU India Aerial Augmented Infantry, leader of Suparna.

Sujatha was anything but a normal girl — had worked very, very hard to not be one; so it was only natural she wouldn’t be scared.

And, most of the time, she did a good job at suppressing the feeling, even when it threatened to bubble up at the surface in the pit of her stomach.

Right now, however, as she heard the news that their training for the day was going to be exceptionally canceled because of some weather turmoils, the wave of anxiety started to overwhelm her in a way she didn’t think she could easily appease.

“What a pain,” Andry declared, letting himself fall all over a nearby couch. “What are we supposed to do now? They warned us at the last minute, so it’s not like we can quickly make other plans.”

Rukhshana made a weak noise of agreement buried under her black hijab. “Maybe… maybe we could play a game together? Until noon, at least…”

“Guess so,” the boy replied, but he didn’t seem very enthusiastic at the prospect. Then again, Andry never seemed very enthusiastic about most things. Everything seemed to pass through him like water; which could be both a relief and frustrating, depending on the situation.

“What do you think, Sujatha?”

“Huh? U-Um…” Sujatha’s eyes darted towards the dark sky, full of threatening gray clouds, trying not to fidget. “S-Sure. Probably.”

At this, both Rukhshana and Andry stared at her as if she was a ghost. They exchanged a brief, skeptical look with each other, before the boy straightened up and arched an eyebrow in Suparna’s leader’s direction.

“You sure?”

Sujatha frowned, feeling as if she was missing something obvious or was left out of an inside joke between her two teammates. Which, unfortunately, happened often.

“Of course I’m sure,” she responded sharply. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

“W-Well…” Rukhi bit her lip, looking up at her hesitantly and wriggling her hands like she did whenever she felt unsure of herself. “It’s… not really like you to say something like this…”

“What?”

“Rukhi’s right,” Andry added. “Usually, you would’ve gone all ‘Who have time for games, you lazy scoundrels! If you only think about playing, we’ll end up the weakest of all Gauntlets Knights!’ and then Rukhi would have freaked out mentally over it, or something.”

Sujatha puffed out her chest in an irritated manner and glared at her teammate. “I do not sound like that.”

“But… you are acting weird, aren’t you?”

Rukhshana took a step towards her, and while Sujatha was about to snap back at her that she was imagining things, her mouth shut up instantly the moment she saw her eyes.

The other girl was looking at her with a concerned gaze, the one she took when she was genuinely worried about her; and instantly Sujatha felt herself softening against her will and guilt clogged up her throat. Had she really done that bad of a job to hide her anxiety?

“You’ve… been odd for a while now,” Rukhi continued. “And… it’s been worse since our training was officially canceled… I know you always think training is important, but… Is there… something else?”

Rukhshana stopped right in front of Sujatha, catching her off-guard, and her eyes staring straight into hers instantly pinned her into place. She gently reached out to her, her fingertips cupping her cheek in a tender, intimate gesture; and Sujatha flushed bright red, froze, then panicked.

“Th-There’s nothing else!” She exclaimed, snapping Rukhshana’s hand away and glaring at the other two teenagers. “But you’re right! You’d better find another way to exercise or study if you have nothing else better to do!”

She turned around before almost running away from the room; which still didn’t prevent her from hearing Andry snorting from behind and Rukhshana squeak and grumbling to herself ‘What’s this, she’s the one who said it was okay for us to play!’

Sujatha paid it no mind. She headed to her bedchambers, her face still feeling hot and her chest about to explode because of embarrassment.

She couldn’t believe how… open Rukhshana was with her in public, sometimes. Well, in private as well.

The two of them had been dating for about three months now, but everything still felt very new and surreal to her. No one knew, of course, with the exception of Andry — who had somehow grilled them only a week afterwards — and it did bring in some new challenges to navigate, but so far Sujatha didn’t regret it. She didn’t, but… she had to admit sometimes it felt a bit too… overwhelming, and she wasn’t always sure how to act towards Rukhi as a result (not that she knew how to handle her before, though).

She sighed, closing the door behind her, and let herself fell on her bed.

Rukhshana was going to be so angry for snapping at her like that, she knew. And maybe she deserved it, too. That… hadn’t been really fair from her, after all. She probably should go apologize before things get worse.

She might not look like it, but Rukhi was a pretty grudgeful person; and if she felt wronged, she was absolutely not going to let it slide. She could stop talking to Sujatha for months because of something like this — and the simple idea made Sujatha’s stomach turns into knots, even more so than it already was.

She knew she was the one who had to apologize, and that she had to do it now, but she couldn’t bring herself to get out of her bed.

The gray sky and future storm that loomed over outside seemed to have drained her entire energy. She wasn’t sure how long she stayed like that, but the moment she heard the ripple of the rain on her window’s glass she tensed, then hurriedly buried herself under the blanket, as if this could protect her from the foreseeing tempest.

Sujatha wasn’t scared — she just… didn’t like the rain. And gray skies and clouds. And the dark. And thunders.

And it was absolutely not because she was scared that when she was a child she would stay hidden that way under the blanket back in her hometown in Hanumangarh, and that she would spends hours praying to Indra that the sky could finally light up.

She definitely never came to her parents for comfort, because Sujatha wasn’t destined to be a normal girl and not-normal girls were never scared.

So she also definitely didn’t jump when she heard a timid little knock at her door.

“Uh… S-Sujatha…?”

The voice on the other side was barely audible, especially with her ears camouflaged by the blanket and the heavy sound of the rain that seemed to get more and more violent as the minutes passed by — but of course Sujatha still recognized her.

She’d recognized her girlfriend’s voice everywhere.

“R-Rukhi?”

She distinguished some grumbling from the door, which confirmed her visitor’s identity and at the same time furthered her confusion.

She’d never thought Rukhshana would ever come to see her first. After what had happened earlier, she would’ve been way too mad for that.

“Um… I… I wanted to… uh, check on you…” Rukhi’s voice let out hesitantly. “Can I… come in?”

Sujatha bit her lip. Her heart screamed Yes please, her mind yelled back God no. Sujatha wasn’t scared, but she still refused to let anyone see her… like that.

Even Rukhshana. Maybe especially Rukhshana.

“No,” she finally declared, with a voice a little too shaky.

There was a sigh. And then the door opened anyway.

Sujatha almost jumped off the bed.

“I just said no!”

“I know,” Rukhshana said, glaring at her. “But it was one of your ‘no’ that actually meant ‘yes, please, I need you horribly.’”

Her frame was hallowed of light from the corridor’s luminosity, and Sujatha could see she was still wearing her hijab, albeit another, more casual one along with a long, dark dress.

She clenched her jaw, glared at her girlfriend, flushed, and then threw the blanket over her head yet again. Damn her.

She couldn’t see her, but Sujatha was pretty sure Rukhi rolled her eyes at this. There was a few footsteps sounds, then the mattress moved, tilted under an additional new weight.

“So. Can I stay?”

“A bit too late for that now,” Sujatha mumbled, and the more this situation kept on the more she felt ridiculous. She acted just like a child — completely unbefitting of her.

“Yes.”

And then they fell into an awkward, deep-seated silence for what felt like an eternity.

“Why…” Sujatha started, succumbing to the discomforting tension, before hesitating. “Why are you here, anyway? I thought you wouldn’t…”

“Talk to you for a while? Yes. I didn’t want to. But…” She sighed. “Andry convinced me it was better to not be stubborn, for once.”

That made sense. Andry seemed to be the only other person Rukhshana actually genuinely listened to.

“But he agreed you owe me an apology.”

Well, she supposed that was true. All three of them were on the same page, for once.

“…I’m sorry… for snapping at you… It wasn’t your fault.”

“That’s fine. I forgive you. But… you’ll have to tell me why you did it.” Of course, only silence met her and Rukhi grumbled. “Come on. Why are you acting like this since this morning? What’s going on? You know you can talk to me.”

And Sujatha knew she could. She knew. She just wasn’t…

Well. She wasn’t used to it. Talk, and be open, and be… be scared. That wasn’t a thing she’d been taught. Not even to someone she, apparently, loved.

Sujatha buried her face into her knees, debating what to do with this overflow of contradictory feelings, when it seemed the sky decided to answer for her.

A booming, deafening thunder ripped the room apart, bathing the place in a wide splash of white light. Sujatha then lost all self-control and dignity and actually screamed, her heart stopping and her breath getting caught in her throat. A couple of smaller, other thunders outside left her a trembling, weeping mess under the blanket, rolled into a ball as if she was hoping to disappear.

For a while, the room stayed quiet except for the sound of the rain, but then finally Rukhi raised a small, doubtful voice:

“W-Wait… Could it be… that you’re scared of the thunder?”

Sujatha made no attempt to try to answer this. She didn’t think Rukhi needed and answer, anyway, as even a three years old could have come up with one.

And then the next second she was greeted with loud, unadulterated laughters.

“Oh no! That’s what this was all about! You’re scared of the thunder!”

“D-Don’t laugh! I’m not—”

Sujatha flushed red as she tried to disentangle herself from the blanket to glare at the other girl; but then another thunder resonated behind her, and she shrieked. Rukhshana gave her a smug look, raising an eyebrow.

And stared.

“…F-Fine,” Sujatha admitted, before hiding her head into her knees. “Maybe… Maybe I’m…”

She felt like someone was tearing out her teeth one by one, having to make such a statement. It would have probably hurt less if it had actually been the case.

Vulnerability was the worst, most humiliating thing in the world. She would rather die than appear weak to anyone, least of all Rukhshana.

Least of all Rukhshana, but…

But, maybe, at the same time, if she had to choose just one person who could see this side of her… then Rukhshana would be the one.

“Maybe… I am… a little scared…”

She wasn’t sure what to expect from her teammate, friend, lover. Maybe some teasing mockery and more laughters; that sounded like something Rukhshana would do, because she sure loved to tease her.

Instead, she felt something warm and soft on her back; a hand, she quickly realized, and when she raised her head, she was meet by a pair of soft, kind violet eyes that shined in the dim room.

“You are so ridiculous,” Rukhi said, but there was only fondness in her voice for once. “You know you got me and Andry actually worried here, right? If it was just about something so silly then you could’ve just told us. We’re your comrades.”

Of course she couldn’t have just told them, and of course it wasn’t just something silly; no matter how ‘ridiculous’ it seemed, it was still a weakness to Sujatha, and she could never let any weakness be seen to anyone. Well, except for now, it seemed.

“We’re all afraid of something. What’s the point of being friends if we can’t rely on each other to parry our weaknesses?”

Sujatha didn’t feel like fighting on the topic, so she just looked away, escaping Rukhi’s dark, deep eyes. Maybe the other girl knew it was a pointless argument to have at the moment, because she just shook her head before sitting right next to her girlfriend, their shoulders brushing. She pulled the blanket and covered up both of their heads with it.

When Sujatha looked at Rukhshana again, her face was only inches away from her own, her breath on her lips.

“Don’t be scared,” Rukhi said, smiling. “I’ll stay with you for the entirety of the storm. Okay?”

Rukhi extended her hand toward Sujatha, and while the former muttered a small ‘Idiot,’ she grasped it without a second thought. Rukhshana then leaned in and pressed her lips to hers, giving a gentle, comforting kiss as she was oft to do.

Sujatha let herself melt into her lover’s embrace, hiding her head into the corner of her shoulder, retracting into her arms every time a thunder shattered their peace.

And here, hidden under the blanket, away from the storm and from the whole world with only Rukhshana’s heartbeat and warmth for company, she didn’t feel so scared anymore.

#Ciconia no Naku Koro ni#Ciconia#SujaRukh#FemslashFeb2023#RukhSuja#Sujatha#Rukhshana#Sujatha Ciconia#Femslash February#Rukhitha#Rukhshana Ciconia#Femslash February 2023#Rukhi#Femslash Feb#FemFeb#Femslash Feb 2023#Fanfiction#Ciconia When They Cry#Connan's Fanfics#CiconiaWhenTheyCry#Ciconia Fanfic#07th Expansion#Sujatha x Rukhshana#When They Cry#Sujatha (Ciconia)#Sujatha (Ciconia: When They Cry)#Connan's Posts#Rukhshana (Ciconia: When They Cry)#Rukhshana x Sujatha#Rukhshana (Ciconia)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

my piece for universal bonds!

#ciconia no naku koro ni#ciconia when they cry#wtc series#loneart#rukhshana ciconia#sujatha ciconia#andry ciconia#suparna ciconia#ciconia

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

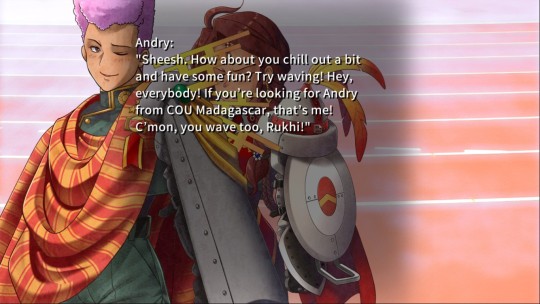

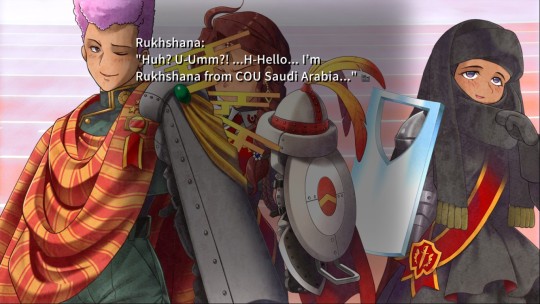

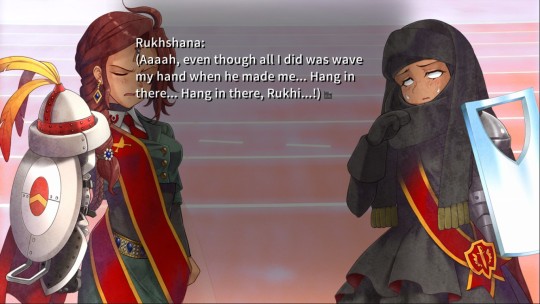

Suparna, my beloveds ❤️

Though I do find it interesting that Andry specifically tries to rope Rukhi into waving and not Rukhshana. Maybe he’s trying to give Rukhi some time to be themselves and take the burden off of Rukhshana, who seems pretty nervous.

#I will now be looking carefully for when andry states either Rukhi or Rukhshana’s name#ciconia#ciconia no naku koro ni#rukhshana ciconia#andry ciconia#ciconia liveblog

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every hour, a woman in Afghanistan loses her life during childbirth

It was midnight when another wave of pain struck. Begum, 35, thought it was finally time for her child to be born, but there were no signs of the baby coming.

“I woke my husband and told him to get a car to go to a hospital. He rented one from our neighbours,” Begum said.

The mother of four travelled while in labour from Ridkhord area in Badakhshan’s Zibak district to the Shahid Ustad Burhanuddin Rabbani Hospital in the provincial capital Faizabad.

Her fifth child, struggling to be born, did not survive the journey.

Begum lived, but many mothers in similar circumstances do not.

Abdullah is currently waiting to hear if his wife will survive their child’s birth.

He and his wife, residents of the province’s Yafta-e-Bala area, came on foot to the central hospital in Faizabad when their baby was due to be born.

“In Yaftal-e-Bala, there are four health centres. However, because of inadequate medical facilities and no doctor available, we had to walk for four or five hours to Faizabad for delivery,” Abdullah said.

“We encountered many challenges along the way, but I couldn’t do much until we reached the hospital.”

Doctors said that because his wife had walked a long distance, it led to severe bleeding and possibly harmed the baby in the womb.

“The mother’s condition is not good and there is little hope for the baby to survive,” Abdullah said doctors told him.

Afghanistan’s deadly statistics for mothers

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) report, each day 24 mothers and 167 newborns in Afghanistan lose their lives due to complications in pregnancy and childbirth.

It’s the highest rate in the world.

“The condition of mothers is highly alarming, particularly for those who travel from remote areas and cover long distances,” a specialist at the Shahid Ustad Burhanuddin Rabbani Hospital, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said.

Having worked in Badakhshan for 22 years, the doctor said that the shortage of healthcare services, especially in remote areas, leads to significant health risks for women.

He recalled a patient who arrived at the hospital from Darwaz district about a month ago after travelling for three days.

“Due to the long journey, the patient’s womb had ruptured along the way, leading to the loss of the baby. The doctors only managed to save the mother’s life with great difficulty,” he said.

Discrimination leading to more deaths

There are concerns the situation is only getting worse as the Taliban place more restrictions on women’s mobility and access to support, and the weakened economy sees healthcare facilities struggle to deliver services.

The WHO reported that in 2023, about 428 health centres were closed because of budget constraints.

Dr Suraya Dalil, WHO’s Director of the Special Programe for Primary Health Care and former Minister of Health in Afghanistan from 2010 to 2014, said that Afghanistan has become one of the most perilous countries for mothers due to insufficient healthcare resources.

Dr Dalil told Rukhshana Media that the Taliban’s discriminatory policies make women more vulnerable in accessing healthcare.

“There is a regime in Afghanistan that systematically discriminates against women. For instance, a few months ago, a directive was sent to the central hospital in Ghazni province stating that women without a male companion would not receive treatment,” she said.

“Similarly, in Herat, a directive was issued prohibiting ultrasound services for women at the central hospital.”

She said that ultrasound examinations are crucial for diagnosis and timely treatment decisions, services that have unfortunately been restricted for women.

Recently, the Taliban supreme leader issued an order for all female employees to receive a reduced monthly salary.

“Recently, we’ve witnessed female employees being allocated a monthly salary of only 5,000 afghanis (US$70), disregarding their rank, experience, and job responsibilities solely because they are women. This is systemic discrimination,” she said.

“The impact of the Taliban’s actions on women extends beyond just health issues. It has multidimensional implications.”

Health professionals strike over reduced salaries

This month several doctors, nurses, and midwives in Kabul hospitals staged a strike in protest of this decision by the Taliban leadership.

At least four female doctors and staff from hospitals such as Wazir Mohammad Akbar Khan, Shaikh Zahid, and Sehat-e-Tefl, speaking to Rukhshana Media, said they cannot meet their basic living needs with the salary recently set by the Taliban for all female employees.

Homa*, a physician at Wazir Mohammad Akbar Khan hospital, said their protest lasted only three hours after the hospital’s Taliban-appointed director dispersed them with threats.

Orphaned children left to raise each other

Hanifa, 21, a resident of Sarjai area of Panjab district of Bamyan province now takes care of her two younger sisters and two younger brothers after the death of their mother.

She said that there are no clinics in their village or nearby areas, which is why her mother had to give birth at home.

“My poor mother cried in pain, clutching her back, yet she continued to bake bread. With my father and two brothers away working on farmlands, there was no man at home. My mother, assisted by our neighbor, who was a local woman, gave birth at home,” she said.

“She always delivered her children at home and was used to it, but this time, one of the twins didn’t come out, and her bleeding was so severe that the entire house was stained with blood.

“After giving birth, my mother survived only two hours. Despite our efforts, we couldn’t deliver the second twin because there was no accessible vehicle, and my father wasn’t home to help us.

“When my mother realized her bleeding wouldn’t stop, she urged us to take good care of her daughter, who was a baby girl. She remained conscious for two hours, growing weaker with each passing moment until she eventually lost consciousness.”

Karima Sadiq* a gynecologist specializing in obstetrics in remote areas, said stories like these are increasingly common.

“Sadly, since the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan, I have witnessed a rise in maternal deaths during childbirth, particularly in villages and districts. Every 24 hours, 24 to 26 mothers are losing their lives during childbirth, highlighting a disturbingly high maternal mortality rate.”

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recently reported that one-third of women in Afghanistan give birth without access to essential healthcare facilities, and only around 67 percent of deliveries in Afghanistan are supervised by healthcare professionals.

According to UNICEF’s report, it is recommended that pregnant women visit a doctor at least four times before delivery, but only a third of women in Afghanistan adhere to this recommendation.

UNICEF stated that that if a mother gives birth outside of a healthcare facility and without access to a skilled health professional, her life is significantly endangered.

Note*: Names are changed due to security reasons.

#afghanistan#gender apartheid#sex apartheid#radfem safe#radical feminism#radfems do interact#radfems please interact

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hypothetical Argument: America Is Again Failing Afghanistan’s Women—and Itself

(In Fact It Was ‘The War Criminal, Loser, Hypocrite, Hegemonic, Conspirator, Double-faced and Fake Democracy Preacher United States’ Who Destroyed The Afghanistan and Brought All Kind of Chaoses in a Peaceful Country. No One Can Deny It)

The deteriorating status of women under Taliban rule is a strategic disaster for Washington.

— By Xanthe Scharff | March 8, 2023 | Foreign Policy

A burqa-clad Afghan woman walks past as a U.S. soldier belonging to the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) keeps watch during a patrol outside Bagram airbase, 50 kilometers north of Kabul on February 28, 2009. Shah Marai/AFP via Getty Images

On Aug. 16, 2021, the day after Kabul fell to the Taliban and the United States began its hasty withdrawal, journalist Zahra Joya woke up in despair.

Joya, then 28, was a woman to be reckoned with. Eight months earlier, using money from her government salary, she founded Rukhshana Media, a newsroom committed to listening to women and telling their stories. By 2021, it had already produced articles that won international acclaim. Now, the Taliban threatened to dismantle all she had built.

Today, 18 months later, her newsroom is a fraction of what it once was, and most of her staff toil in secret. But they persist, often anonymously—shining a sliver of light into the increasingly dark world of the women of Afghanistan.

The United States and other Western governments should take note. The women of Afghanistan, after 20 years of relative freedom, will not be content to slink into the shadows. Their continued protest and fight are an essential lever of power for the United States and all other countries that share a stake in promoting recovery and ultimately peace and security in Afghanistan.

How a nation state empowers or disempowers women is a key predictor of how it will behave among the community of nations. More than two decades of research have affirmed that women are essential to security, and their well-being and empowerment play a determinant role in the prevention of war and assurance of peace. We also know that women have a central role in advancing democratic freedom.

Simply put, it is in the strategic interest of the United States to create and maintain a foreign policy that prioritizes women. To do so, it will first have to understand what it got so terribly wrong in Afghanistan.

Whatever Gains Women Made in Afghanistan During the past two decades have mostly slipped away over the last 18 months. In 2021, women held 27 percent of the seats in Afghanistan’s National Assembly, worked in government positions, and attended university. Afghanistan and the international community financed the training and deployment of thousands of midwives, reducing the maternal death rate from 1,600 women per 100,000 births in 2002 to 638 women per 100,000 births in 2017.

Now, a steady drumbeat of onerous restrictions ensure that women are kept in their homes, unable to access jobs, health care, and education. This year, the Taliban ordered all female health care workers to wear a full hijab, including face coverings. In late December 2022, Taliban leaders issued a decree that bars Afghan women from working for nongovernmental organizations. The lost income from barring women from the workforce could cost Afghanistan as much as 5 percent of its GDP or about $1 billion, according to the United Nations—plunging the country deeper into poverty, exacerbating food insecurity, and threatening stability.

The United States and its allies in the war on terrorism invested billions of dollars to bolster the status of women in Afghanistan, pushing programs to elevate basic health care, include women in governance, and advance educational opportunities. Many of them fell short.

For example, the Afghan Ministry of Interior Affairs—with support from the internationally funded, U.N.-administered Law and Order Trust Fund for Afghanistan—set a goal of hiring 5,000 female police officers by June 2014, yet it failed to plan for and build restroom and locker room facilities to accommodate them. Afghanistan never reached its goal. That, in turn, created a counterinsurgency security gap. In a gender-segregated society, female police officers are essential for conducting searches of women at checkpoints. Now, some suicide bombers disguise themselves as women to evade searches.

We already know in many cases that the programs created to advance women’s inclusion lacked a key component: the voices of Afghan women on the ground, the only people who truly understand how to navigate the strictures of Afghanistan’s male-controlled society. The United States’ 2017 Women, Peace, and Security Act affirms that women’s rights should be at the center of peace and security planning. Yet in the reality of the war-fighting bureaucracy, women are often an afterthought. Indeed, the U.S. National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, two essential documents that guide the country’s peace and security posture, included few references to gender issues except with regard to gender-based violence.

Engaging in a war and subsequent stability operation without this key intelligence has real consequences. The United States “often struggled to understand or mitigate the cultural and social barriers to supporting women and girls,” which led U.S. agencies to set unrealistic goals, wrote John Sopko, special inspector general for Afghanistan reconstruction, in his August 2021 report, “Lessons From Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction.” As Melanne Verveer, executive director of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, pointed out at a recent Atlantic Council panel I moderated, had the United States done more to empower women and done it better, Afghanistan might look different today. “When the dust settles and we finally go back and analyze all the things that went wrong [in Afghanistan], one of them will certainly be that we did not fully ensure the meaningful participation of women in Afghanistan,” Verveer said.

These shortcomings deserve close examination, both for reasons of accountability and the potential to learn from these mistakes. From its start, the George W. Bush administration used women’s rights and empowerment as a justification for its war in Afghanistan. “The fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women,” then-first lady Laura Bush said during the administration’s weekly radio address, delivered on Nov. 17, 2001—a little more than a month after U.S. ground troops began their assault. She focused on the suffering of women and children under the brutal rule of the Taliban. In the Obama administration, then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton told the Taliban that women’s rights were nonnegotiable, and she led efforts to advance understanding of the connection between gender and security within government.

Yet 20 years of war and more than $2 trillion later, the Taliban are back in power, and women are once again veiled, shut in their homes, and excluded from civic life. Given the grandeur of past gender goals and scope of the United States’ failure, U.S. taxpayers deserve a reckoning. The U.S. response to the fall of Kabul raises stark questions about whether women’s rights are valued, especially in the midst of a crisis. As the Taliban took over Kabul, officials scrambled—caught off guard—and turned to civil society to help evacuate and get visas for women leaders, who faced imminent danger.

If The United States Wants To Maintain Peace, Stabilize rogue nations, and ensure that its next military endeavor succeeds, it must examine how its policies and practices to support and empower women went so dreadfully wrong in Afghanistan. We need to know what went well so we can replicate it—and what failed so we can fix it.

The bipartisan Afghanistan War Commission is tasked by Congress with conducting a review of U.S. military, intelligence, foreign assistance, and diplomatic involvement in Afghanistan. The 16 commissioners include only two women, a composition that hardly lives up to the United States’ own Women, Peace, and Security Act, which affirms the importance of women having a full seat at the policymaking table. If this commission is tasked with examining 20 years of involvement in Afghanistan and gleaning the lessons learned with regard to women’s rights, then it is seemingly off to a poor start.

Afghanistan—the failures endured and the inroads achieved—provides some of the most important potential policymaking lessons in recent history related to applying a gender lens to foreign policy, lessons that stand to be lost if not given their full due by this commission. Gender issues are such a pervasive contributor to the United States’ failures in the country that one could argue they deserve to stand at the center of this effort, if not as a stand-alone commission.

We don’t know—and may never know—whether a different approach to women’s rights and empowerment in Afghanistan would have changed the outcome, but we need to ask the questions. The findings should inform U.S. security strategy going forward.

Until we have better answers, we must do what we can to keep what little the United States built for the women in Afghanistan from crumbling further and to support Afghan women leaders, both inside and outside the country, who have established inroads to support others—even if the effort takes decades. The Taliban are erasing women from public life in Afghanistan, wrote Richard Bennett, U.N. special rapporteur on Afghanistan, in a recent report. Women said they feel targeted and unsafe, but “they continue to resist violations of their human rights,” he wrote. “We know that what has happened to us is not right. Some of us could have left the country, but we did not. We decided to stay and fight for women’s place in Afghan society,” the women told Bennett.

Afghan women don’t have the option to walk away from the consequences of the failed promises that now govern their daily lives. The U.S. government shouldn’t either. The United States cannot hide in the shadow of its failures and hope to dodge its responsibilities. The situation is dire, and the world is watching.

The arc of history is long. If the United States give up on supporting women in a forceful way, then it will pay for it down the line. Not investing in the well-being of women is a factor in military failure. If the United States and its allies want any chance at maintaining stability and security in the region, then they must support women leaders at every level, both in and outside of Afghanistan, to promote immediate and long-term work as well as spur other countries to do the same. Most importantly, they must listen to the women of Afghanistan. That’s why we at the Fuller Project continue to support Afghanistan’s female journalists by publishing their stories and amplifying their voices—women like Joya.

Joya’s life in Afghanistan mirrors the triumphs and struggles of the women and girls of Afghanistan. She began her life under Taliban rule, dressing as a boy to attend her elementary school. In 2001, after the United States chased the Taliban from the country, Joya shed her disguise, finished her education, and embarked on her journalism career. She was often the only woman in the newsroom. The absence of women’s voices motivated her to create Rukhshana Media, named for a young woman stoned to death by the Taliban.

Joya belongs to a generation of women who experienced an Afghan society free of the Taliban. She is accustomed to freedom, and she feels its absence acutely. She feels, she said, like she has traveled back in time.

These days, Joya works in exile after Taliban threats against female journalists forced her to flee Kabul. She edits stories from her remaining colleagues in Afghanistan. When the Taliban took power in August 2021, 2,490 women worked as journalists. By December 2021, that number had dwindled to 410, according to Reporters Without Borders.

“It’s very painful and sad,” Joya told actress Angelina Jolie in an interview for Time magazine’s Women of the Year. “Honestly, we don’t do simple journalism these days; we are trying to write for our freedom.”

She is ready to do her part to pull Afghanistan back. She wants to hire more journalists, tell more stories, and maintain the freedom of expression she sees as her birthright.

That is democracy building worthy of investment.

— Xanthe Scharff is the CEO and Co-founder of The Fuller Project, the Global Newsroom dedicated to groundbreaking journalism that catalyzes positive change for women.

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Photo

naima and rukhshana from ciconia :) i just like their designs

408 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rukhshana and Sujatha 💚 🖤

Happy Valentine’s day!

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

حوصله من به سر آمد I grew restless

vimeo

Imagery Rukhshana performing in the 1969 Afghan film, The Suitor.

حوصله من به سر آمد

I grew restless

رخشانه

Rukhshana

حوصله من به سر آمد ز بر یار خبر آمد

I grew restless when I heard the story of my beloved

که شمع بزم رقیبان شده یارم شده یارم

He had become the light of my rival's celebration

شب زمنزل میبرایی

You leave home late at night

مست به بوستان میدرآیی

You enter intoxicated in the garden

نغمه جان می سرایی

You sing your heart out

به اامید دل میدرآیی

You arrive with expectations

Rukhshana, a pioneering Afghan woman vocalist, recorded this track in the early 1960s at Radio Kabul. This version was released by Golden Recording, Tehran, Iran, and posted on afghanrecordsgallery.com.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I PROMISE I will not draw all the WTC girls in strawberry dresses but… I just thought this really fit their Aesthetics, so…..

#Ciconia When They Cry#Ciconia no Naku Koro ni#Naima#Rukhshana#NaiRukh#Naima Ciconia#Rukhshana Ciconia#RukhNai#Naima (Ciconia)#Rukhshana (Ciconia)#Strawberry Dress#Rukhima#07th Expansion#キコニアのなく頃に#When They Cry#Strawberry Dress Challenge#Naima (Ciconia: When They Cry)#ルクシャーナ#Rukhshana (Ciconia: When They Cry)#ナイマ#ナイルク#Naima Ciconia When They Cry#Naima (Ciconia no Naku Koro ni)#ルクナイ#Lirika Matoshi#キコニア#CiconiaWhenTheyCry#Ciconia Fanart#Art#Fanart

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

ciconia suparna

#top image is new all the others are old doodles#i have officially given up hope on phase 2 ever coming out so they are my ocs now. thanks for your understanding .#ciconia no naku koro ni#ciconia when they cry#rukhshana ciconia#sujatha ciconia#andry ciconia#loneart

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

dfcu Bank bids a fond “Adieu” to Rukh-Shana Namuyimba

dfcu Bank bids a fond “Adieu” to Rukh-Shana Namuyimba

dfcu Bank has announced that Rukh-Shana Namuyimba will be leaving at the end of July 2021 following her notice of resignation from her role as Manager Communications & Events; a position she has held for the last four and a half years. As the Manager of Communication & Events, Rukh-Shana has been responsible for the planning and execution of the Bank’s communication strategy. In her capacity,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

SUPARNA BEST SQUAD 🧡💛

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

'We will work and we will fight for our fundamental rights' — From climate activism, to fighting gender & health inequality, here's what you should know about three women who were recognized by the Gates Foundation as Goalkeepers

For more world news, subscribe to NowThis News.

#gatesfoundation #activism #goalkeeper #Politics #News #NowThis

#now this news#now this#solarpunk#climate activism#gender inequality#health inequality#Gates Foundation#activists#activism#vanessa nakate#Uganda#climate justice#Zahra Joya#London#England#Rukhshana Media#Dr. Radhika Batra#Radhika Batra#Every Infant Matters#Africa#Vash Green Schools Project#afghanistan#new delhi#India#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love them both.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

berunipah replied to your post “finished ciconia phase 1, that whole final sequence was great”

whos your favorite character/characters....

lilja was probably my fav, but i liked a lot of the cast relatively equally so its hard for me to make a list

1 note

·

View note