#Ring Cycle

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Genshin 5.7 spoilers specifically for a space and time for you. (I havent gotten to skirks thing yet)

My disorganized current thoughts on the new main quest

OKAY. Istaroth!? What are you doing????? How many times has it been now? First with the ancient Sakura, the before sun and moon parable, and now this? Also samsaras but I don't know if thats actually Istaroth's doing.

Its so interesting. Also i wish we could have found out a way to not start the loop.

Istaroth has done so many shenanigans now! Also lowkey this kind of mildly meddles with the boxed time theory of Teyvat. But also not.

Also Surtalogi and Dain were classmates!? And and! It was probably the sibling's power the five sinners stole. It was pretty much spelled out for us by Haden but like also we shouldn't take things at immediate face value too? I mean its Genshin.

Also Vedrfolnir is the reason Dain doesn't rot!? (Lowkey forgot they were siblings) He gave him a ring!?? I wonder if Pierro is the same. This also has a lot of fun hints with The Ring Cycle which Khaenri'ah takes a lot of inspiration from.

Dain really out here knowing all the sinners personally. Like it was assumed since his hatred was so strong but its funny. His classmate, his older brother, I don't quite remember if he has close ties with the other 3 but like this is funny right? And then being a personal companion to our sibling the prince/princess. Dain out here as a main character man.

Also maybe the fact that our sibling forgetting their memories is part of the reason why they're not a descender because they consider themselves part of the world. One trait I find really interesting is that our Traveler genuinely doesn't care that much. The moment the sibling says "let's go", the traveler wouldn't even hesitate they'd be out of there. Traveler just wants to leave, the only reason why they're still here is because of their sibling. But its our Twin's pride and connection to the world that makes us stay. Like we're a trapped star.

Also technically there's three hibernation keys at one time sorta. Imagine we use the third for Paimon.

On another note

Also 3 of the four Samsaras being named after locations in the game Hyperborea, Remuria, Natlanese ect. is interesting. And Khraun-Arya sounds awfully close to Khaenri'ah. Ya know what's interesting about all 4 of these locations. They had some sort of major revitalizion/rebrand(?). For example, Hyperborea is the original location of the Frostmoon Scions who relocated to Nod Krai. Remuria had the Grand Symphony and turning people into machines. Natlan relocated from Ochkanatlan to current Natlan. Now Khaenri'ah is being remade whereever our twin places the Atlas. Maybe this is why we're in the fourth Samsara because Khaenri'ah hasn't been remade yet.

Or it could be time travel

I had a really random thought about Samaras about how maybe each Samasara is a loop we're involved in. So like the first one being The Sakura, the second being this one from 5.7 and so on? But thats really far-fetched I don't really buy it either

#khaenri'ah#genshin impact#genshin impact spoilers#genshin impact 5.7#genshin 5.7#a space and time for you#dainslief#dainsleif#aether#lumine#abyss twin#abyss#istaroth#samsara#remuria#ochkanatlan#hyperborea#nod krai#surtalogi#vedrfolnir#pierro genshin impact#ring cycle#like there isnt a ton of new jaw dropping lote#but a lot to chew on instead

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

i went to see the walküre broadcast from the royal opera in cinemas and they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. they’re half children. i’m screaming, they’re half children they’re half

#emotional support opera is supportively destructive#Barrie Kosky didn’t 100% reach his potential conceptually but BOY did he understand the characters#WELL DONE#I’m so in my own opinions abt Wotan’s kids that i rarely expect to see my expectations play out#but in london’s staging they’re just. so young. and mostly very traumatised#u can tell they’ve not lived for long and at the same time lived too much#they are. SO YOUNG#opera#classical music#richard wagner#opera shitpost#ring cycle#classical music meme#opera meme#der ring des nibelungen#die walküre

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your ideal age range for the Volsung-Nibelung-Dietrich cycle characters? In the Scandinavian sources, Brynhild claims to have been adopted by Agnar and Aud at 12 to be their mascot valkyrie (which is what got her in hot water with Odin) and was put to sleep for any number of years, with sources differing on if her old retainer Heimir was her foster father or brother-in-law. Sigurd himself claims to be barely a man, that is, the legal adult age of 16, when Regin packs him off to slay Fafnir. Altogether it seems the two of them are rather young (16-19 physically?) and Gudrun is also in their age group. Later on Gothorm is too young to swear brotherhood with Sigurd and is thus used to kill him, making him younger than Sigurd and younger than 16 when they met.

In the Continental materials, Giselher is also called young, but there's no mention of Gernot and by extension Giselher being under 16 when they meet Siegfried. Gunther seems a fair bit older than them, being the first born and succeeding to the throne (as a sub-king, presumably, in versions where Gibich is still alive) shortly before Walther's escape from Etzel. However, he doesn't seem to have had a wife in either Continental or Scandinavian versions before his mother suggests Brynhild, which might indicate he's still fairly young. Historically he was active during 411-436, which gives him a 20+ year reign.

Hagen's age definitely has the greatest variation across sources. In the Nibelungenlied proper he's much older than the Nibelung siblings, but in the Walther stories he doesn't seem that much older than Walther, Hildegund, and Gunther, and the first two might be preteens at oldest. And of course in the Scandinavian materials, he's definitely younger than Gunther, being one of the Nibelung brothers. Classically, he's brother #2, slotting between Gunnar and Gothorm, with his father being Andvari/Alberich/Aldrian the elf. Wagner makes him presumably the youngest sibling. (Of course there's also the possibility that Grimhild/Ute just brought him along when she married Gibich, which would make him the oldest sibling. And also explain why Gibich would just pawn him off to Etzel.) Dankwart is also in the older adult range, but if Hagen was illegitimate, he could just have had a different mother, because who knows how long elves live, except it being very long. Hagen's unnamed sister (Gullrond?) would have to be much older to give Hagen two nephews, one of which is an adult during the Nibelungenlied.

Dietrich's age is also funky. He's presumably the same age as Wudga and Heime, his two closest companions until the exile. They don't seem to be too much older than Siegfried, Gunther, and Kriemhild. Dietrich gets tutored by Hildebrand when he's seven, acquires Hildigrim and Nagelring at fifteen, and has his Virginal/Wunderer adventure (the plots are so similar I suspect them to be the same story) at sixteen. He goes into exile sometime between the Rosengarten tournament and Kriemhild's marriage to Etzel. By then he's definitely a fair bit older than the young adults Alphart, Wolfhart, and Dietlieb, but Hildebrand is just ready to welcome the birth of Hadubrand. Historically, the Burgundian Nibelungs died in 436, the Visigothic Dietrich died in 451, Attila died in 454, and if Dietrich was also Theodoric the Great, he would've lived into 526. Then again, his family is known for ridiculously long lifespans, with the stories from his cycle claiming his father, grandfather, and uncle all lived into at least their 100s.

Hildebrand, Ilsan, Eckart, and Regin are all consistently portrayed as old guys. So is Sigmund in the Scandinavian material, where he actually featured prominently. Sigurd's two Volsung brothers are presumably dead during the main adventures, because Brynhild and Gudrun mention Hamund and Haki, his nephews via Hamund, usurping the Swedish throne and feuding with the pirate King Sigar. Helgi died in the prime of his life, while Hamund never appears on screen (but the movie adaptation of Hagbard and Signy mentions he was killed by Sigar a few years before, when his sons were children).

Etzel is definitely older than Walther, Hagen, and Dietrich, but strangely, there's no particular mention of him being old. Then again, there's no mention of Gibich and Ute being old in the Rosengarten story either. Nor is there any mention of how much Hjordis and Prince Alf might have aged in the Volsung Saga. In the Scandinavian stuff, Atli's sister Oddrun gets sneaky with Gunnar, but that version doesn't include Etzel's past with Walther, so who knows how old either of the Hun siblings are.

That's a great rundown of all the different traditions, and you make some great points.

As for me, I don't have really have age headcanons for anyone, going more for The Vibes and the "okay, what do I need for this concept to work?", but at the same time, age is one of those things where I tend to compartmentalize pretty heavily, for both practical reasons (I'm pretty sure I'd have a harder time than you keeping track of everything going on and gathering it all up into something coherent!) and thematic ones. (Simply put: different things work better for me, or have a stronger hold on me, in different contexts because I feel I can make more out of them on a narrative level.)

So, here's how things (generally) go in my head:

Norse sources: I tend to see Sigurd as rather young, because as you mentioned, he describes himself as such around the time he's sent off to kill Fafnir. I also tend to see his first adventures, from finding Grani to falling for Sigrdrifa/Brynhild and meeting Gjuki's children, as happening in rather quick succession, sort of a whirlwind of violence and drama and revenge and romance... so, yeah, still a teen (older teen at most) when he ends up meeting married to Gudrun. I imagine Gjuki's children to be all pretty close in age (except maybe Gothorm, a fair bit younger than the rest, and Gullrond, who reads sort of like a wise oldest sister to me, tho she doesn't feature a lot in my headcanons) and in the same age range as Sigurd, but I don't otherwise have a fixed birth order for in my head besides Gunnar being the oldest.

Brynhild is... complicated. You've got the enchanted sleep, and the question of how long it lasted and how fast or slow she aged, physically and mentally, in it. You've got all her wisdom and knowledge that, to me, makes her read a little older than Siegfried in her brief stint as his teacher, but then again, also the fact that she used to be a Valkyrie rather than just a mortal woman, so all that might be more supernatural knowledge and wisdom than anything else. And then, you have her foster father, Heimer (who's also her brother-in-law through her sister Bekkhild), and her brother Atli, and ofc Agnar. The timeline can get kind of messy, if you try to make it all fit in, because there's just so much stuff. The one thing I always stick by is Atli being considerably older than her (by a decade or more) and them not being particularly close, due to the "Atli didn't give much of a damn about getting compensation for her death, it was just a pretext to get the gold" interpretation, which is the one I tend to favor.

Nibelungenlied/Waltharius/continental sources: Here, I tend to see everyone as a bit older then their Norse counterparts. Siegfried, after all, has already conquered something like twelve kingdoms and gained his fair share of fame through distant lands by the time he comes to Worms -- and while dragon-blood-enhanced strength must certainly come in handy with all that, all in all, it must still have taken him some time. Still, I do seem him as kind of younger than you'd expect with his curriculum. A little older than yet still a good fit for Kriemhild, a maiden who's definitely able to fall in love and fall hard yet doesn't seem to have ever felt that kind of feeling for anyone before meeting him, to the point she used to see the whole thing as something foreign and that she could totally just choose to avoid.

My birth order for her and her brothers is generally Gunther > Gernot > Kriemhild > Giselher. With the eternal "youth" Giselher, who gets stuck with that title even in later parts of the poems being kind of the baby of the family. Not literally, ofc, but in the sense that, even if the poem counts him as one of the three kings of Burgundy and protectors of Kriemhild, it's his brothers who handle most of the harder work even while kind of "mentoring" him on kingship through the rather hands-on method of having him rule alongside them. Anyway, I see this whole set of siblings as pretty close in age, too, just to avoid overcomplicating my life, but with a couple of years separating Gunther & Gernot and Kriemhild & Giselher, something that also influences their dynamics as siblings.

When it comes to Hagen, I'm very influenced by the Waltharius, where he's presumably the same age as Walther and Hildegund and somewhat older than Gunther. I still don't see him as that much older than his kings, tho, as I interpret Gunther being too young to be sent away as a hostage to the Huns as him really being very young. Think Hagen being in his early teens and Gunther still being a child at the time. I tend to assume something like an at least five years difference between them, and then Gunther ascending to the throne a bit younger than he should probably be due to Gibich's very sudden and premature death, with Ute being his counselor (or trying to be, at least -- Wasgenstein wasn't exactly the most brilliant idea and I do think she opposed it but also that in the end it was still his choice) for the first few years and then him naming Gernot (and finally Giselher) as his co-kings as soon as possible due to feeling the pressure of being the only ruler as soon as he got started on the job. (Which, in my head, also contributes to him only setting his eyes on a bride rather late, despite the court muttering a bit about it at times... too much stuff on his mind already, and for a good while, too.)

Dankwart is an interesting case, as in the latter half of the poem, he claims to have also been just a youth when Siegfried was murdered. Granted, I've seen interpretations dismissing that info as a mere messed-up timeline or as Dankwart just lying through his teeth, due to his role in the court of Worms, but I personally find more interesting/funnier to take it as face value. The idea of him being about as cunning as his older brother Hagen and proving himself as an asset to the kingdom from an early age (perhaps in part to live up to Hagen himself and his deeds) yet playing the "I am/was only a regular youth" card when it suits him is higly entertaining to me. As for their sister, the mother of Patravid and/or Ortwin, I see her as the oldest of the trio, and definitely already out of the house by the time Aldrian volunteers Hagen as a substitute hostage.

(I'm not very fond of the "Hagen as Gunther's uncle/family friend so dear he might as well be a blood-related uncle" thing, tbh. Does it have some backing? Yeah. Do I see it in the way the characters interact? Not really, and that's what matters the most to me.)

Etzel/Attila was already a considerable threat for the Burgundians at the beginning of the Waltharius, and married, too. And yet, apparently still childless... unless his children with Helche, who iirc get killed by Witege at some point, have already died by then. (But that does involve Dietrich, after all, and... er, I'm talking about him in a moment, let's leave it at that for now.) So, he's a bit of a question mark to me. Tho I like to think he and his wife ended up treating Hagen, Walther, and Hildegung almost like their children, whatever void in their life they're trying to fill by doing that... but ofc, that was a whole mess in it's own way, when everyone was perfectly aware that a broken treaty could spell death for any of those three. (Hi and welcome to a new episode of: Waltharius Manu Fortis Absolutely Obliterates Halja's Feels, I suppose.) I do see his later marriage to Kriemhild as a kind of May-December romance. Or, well, "romance."

Dietrich is... Dietrich. If Brynhild's complicated and Etzel a question mark, he is a headache. I'll admit I've never even tried to build a timeline for him that could possibly make sense in my head. Stephan Grundy has a bit of a running joke about him looking like he never gets old/no one being able to figure out his age for sure, and, tbh, I totally get him. Drag him.

Bonus Wagner's Ring Cycle: I'm pretty sure Gunther mentions being the firstborn... tho I've only ever read the libretti/subtitles to the operas in Italian and English, so for all I know, he might as well be just saying that he has the right of primogeniture, as the one legitimate male son. Still, I see Gutrune as the middle child and Hagen as the youngest. This is another canon that skews very young in my head, with Siegfried, the Gibichungs, Wotan's eternally-maidenly Valkyries, as well as Siegmund and Sieglinde in Die Walkure, all being some subset of Troubled Teen Who Needs Therapy (As Well As Better Parents), Not This Shit. Based on the implied timeline in Die Walkure, I think of Hagen as just a little older (a few months to a year, no more) than Siegfired. I love to joke about the former being a cynical goth/emo teen (Hagen's Night Watch scene and its endless -- if objectively kind of justified -- bitching, my beloved) and the latter being your typical meathead teen jock. I also joke about Gutrune being the stereotypical middle child with no self-esteem and Gunther being the young adult who should probably be at least a little more mature and responsible than everyone else, given his age, but is really just a mess on every level, but alas, I do that mostly just in my head, because sometimes I get the impression it's mostly just me seeing (or being interested in seeing) them this way.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rackham's Water Nymphs

The 1910 drawing by Arthur Rackham of the Rhine Maidens from Wagner's Das Rheingold is a brilliant example of the blending of Germanic mythology and Art Nouveau style. In the opening scene of Wagner's epic Ring Cycle, the drawing depicts three water nymphs guarding the priceless Rhinegold in the depths of the Rhine River. Rackham's unique artistic technique perfectly complements this mythological subject matter. His use of sinuous, flowing lines, which resemble the river's current and the maidens' elegant swimming, gives the impression that everything is always moving. The illustration's limited color scheme, dominating by sepia and golden tones, successfully conveys both the underwater scene and the existence of the sought-after Rhinegold. The dynamic structure of the music is particularly noteworthy. The three Rhine Maidens' bodies, arranged in an ascending diagonal line, create a rhythmic pattern that draws the eye upward through the picture. The maidens' long, flowing hair blends seamlessly with the whirling patterns of the water, making it difficult to tell them apart from their aquatic surroundings. This visual style further supports their magical status as elemental beings inextricably linked to their watery realm. The precise depiction of the water's surface patterns and the delicate interplay of light and shadow demonstrate Rackham's attention to detail. The artist's distinctive dreamlike quality, combining precise pen and ink work with ethereal watercolor washes, brilliantly captures the mysterious ambiance of Wagner's opera. The drawing exemplifies Rackham's skill at striking a balance between atmospheric effects and accurate draftsmanship, producing an image that feels both meticulously planned and remarkably unplanned. In Wagner's Ring Cycle, this scene is the prelude to the dwarf Alberich's spectacular robbery of the Rhinegold, which initiates the entire tragic cycle. Rackham's rendition captures the innocence and playfulness of this time, before the corruption of the gold changes the universe for both gods and mankind. The maidens seem elegant and carefree, oblivious to the disaster that awaits them as a result of their poor guardianship. This illustration best represents the early 20th-century book illustration golden age, when Rackham and other artists were producing works that elevated illustration to high art. His rendition of Wagner's opera serves as an example of how visual art can enrich and enlighten literary and musical compositions, adding new levels of emotional resonance and meaning. The artwork continues to captivate viewers, offering a glimpse into both Germanic legend and Edwardian aesthetic tastes. This work's timeless appeal stems from its ability to anchor myth in exquisite creative technique while capturing its airy and enigmatic nature. With a complexity that appeals to both children and adults, Rackham's Rhine Maidens represent the meeting point of the natural and otherworldly realms. This drawing continues to serve as evidence of Rackham's exceptional talent for using his own artistic vision to bring fantasy to life.

#ring cycle#arthur rackham#water nymphs#sirens#mermaids#faeries#fae#fae folk#faerie#fairies#faerie art#fairy art#rhine maidens

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Broke: Ugly modern minimalist Wagner staging

Woke: Beautiful old-fashioned Wagner staging

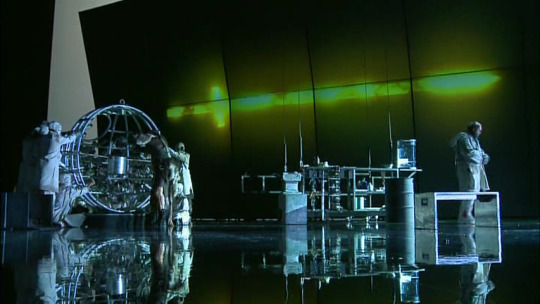

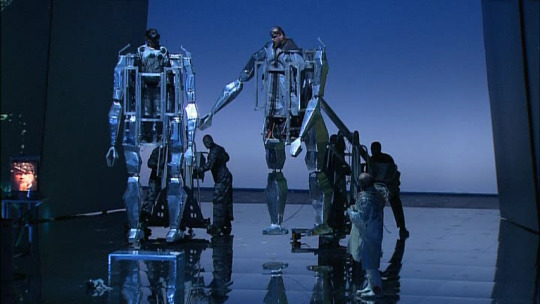

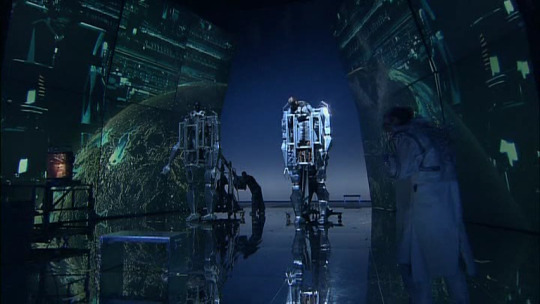

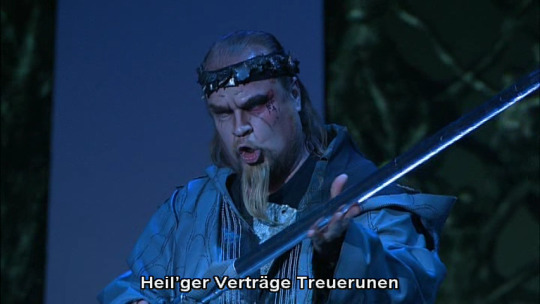

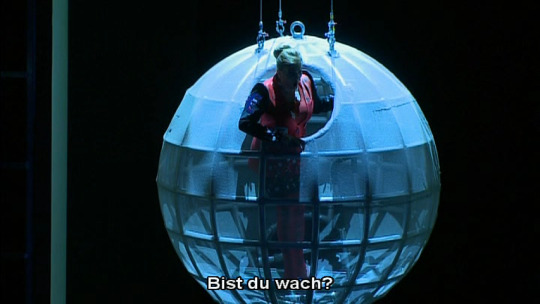

Bespoke: FUTURISTIC PSYCHEDELIC SPACE WAGNER

I have slowly watched the Ring Cycle in the 2008 Valencia production over the last weekends. (It's also on YT, but without subtitles.) First time I watched the whole thing! I wanted something more traditional at first, but I happened upon an excerpt of this version and it just somehow appealed to me, so I watched this instead.

(I still agree with what I said on the topic earlier - if I didn't know anything about the source material, the Nibelungen and Norse mythology, I would have found this staging very confusing.)

Anyway, here's some pictures because it just looks so damn cool. Sorry the quality is not so great. DON'T click to enlarge! Believe me, you'll regret it.

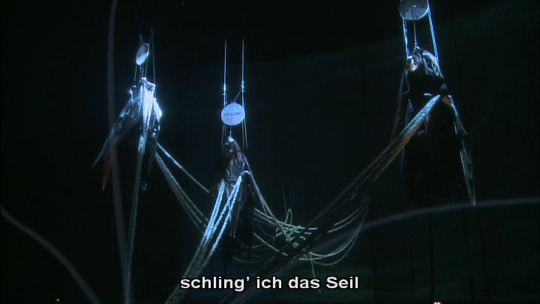

THE NORNS:

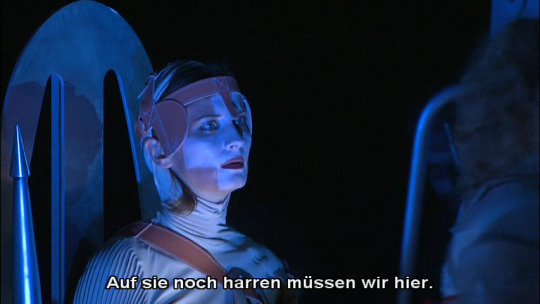

Fricka argues with Wotan:

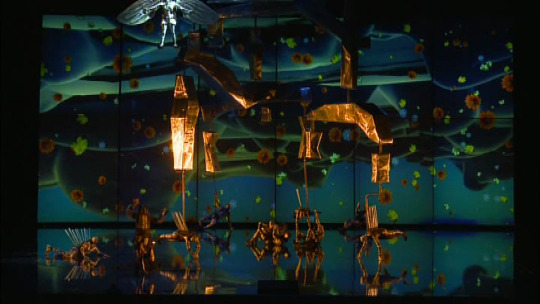

THE VALKYRIES:

A talking bird:

This is what the inside of a dragon lair looks like:

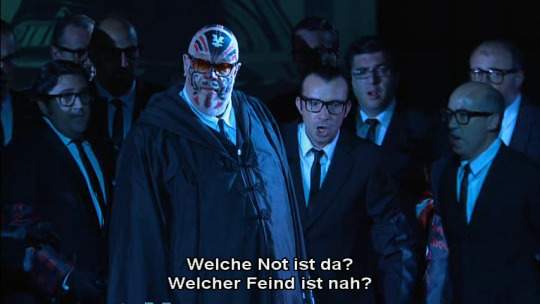

The scheming nobles / corrupt elite are investment bankers or something. First picture: Gutrune and Gunther. Second picture: Hagen and his men.

Alberich visits his son Hagen:

Brünnhilde in her wedding dress, having the worst day of her life in front of Rhine-waves made from empty plastic bottles:

Mime in his chemistry lab (this must be REALLY confusing to anyone who doesn't know the story - why does he have an isolated chemistry lab in the forest? Originally he's a smith.):

Wotan and Mime talk about giants, which are visualized as battle mechs, I was so delighted!

Wotan, who was intensely dramatic for 16 hours straight:

The wall of fire around Brünnhilde's rock bed:

Gutrune always travels in her personal miniature death star:

Finally, Ragnarök:

And those are the 30 pictures per post that I'm allowed.

#wagner#ring cycle#The Opera#norse mythology#music stuff#opera#siegfried#brünnhilde#wotan#germanic mythology

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

the ring cycle is just richard wagner's very elaborate nibelungenlied fanfiction

#yes i finally finished that thing#10/10 would not recommend#richard wagner#opera#ring cycle#the ring of the nibelung

1 note

·

View note

Text

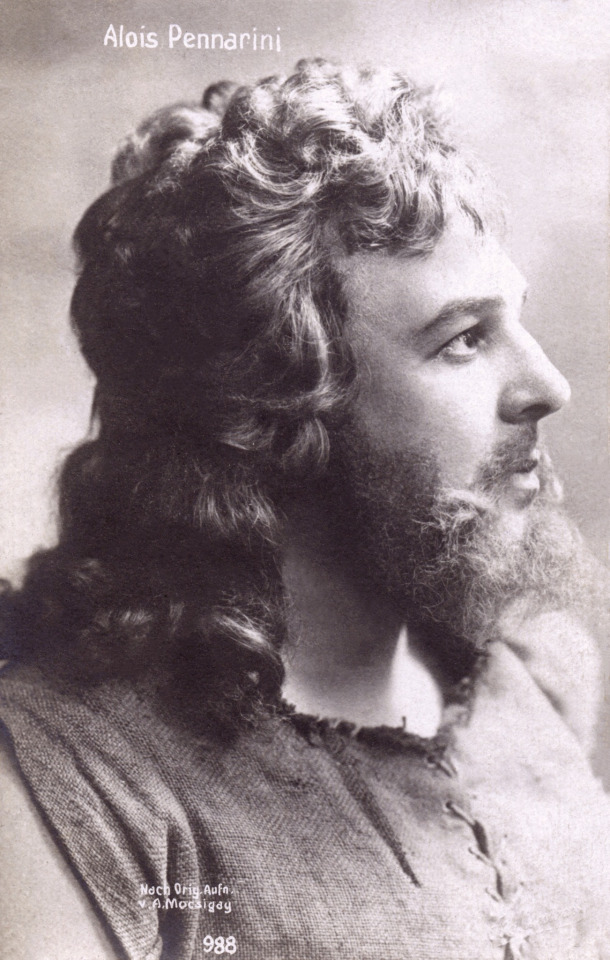

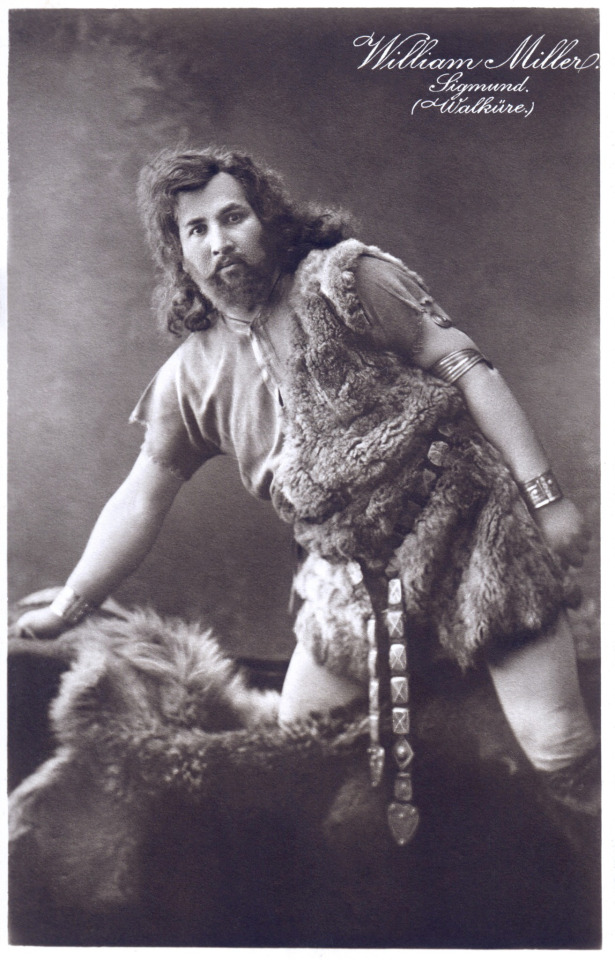

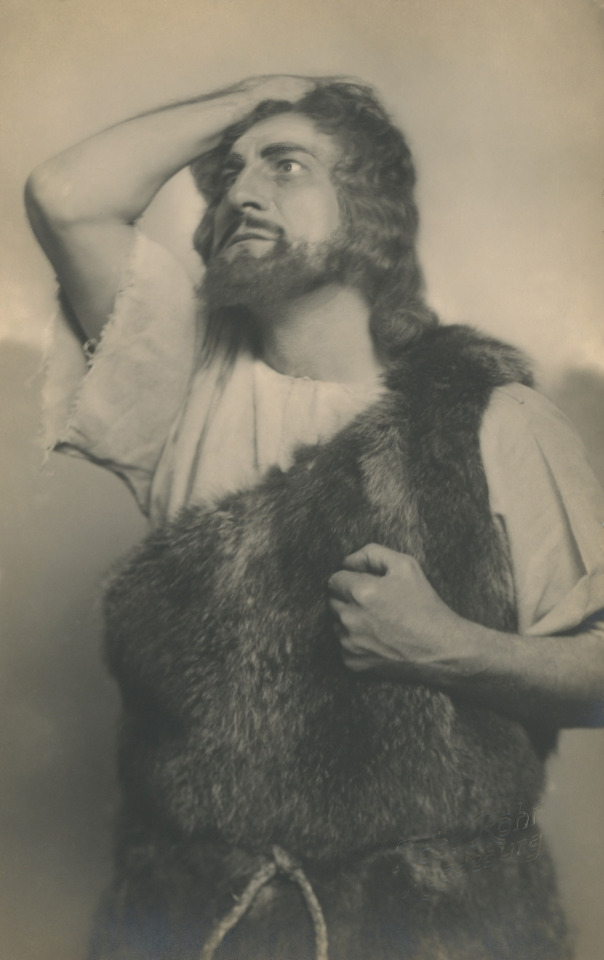

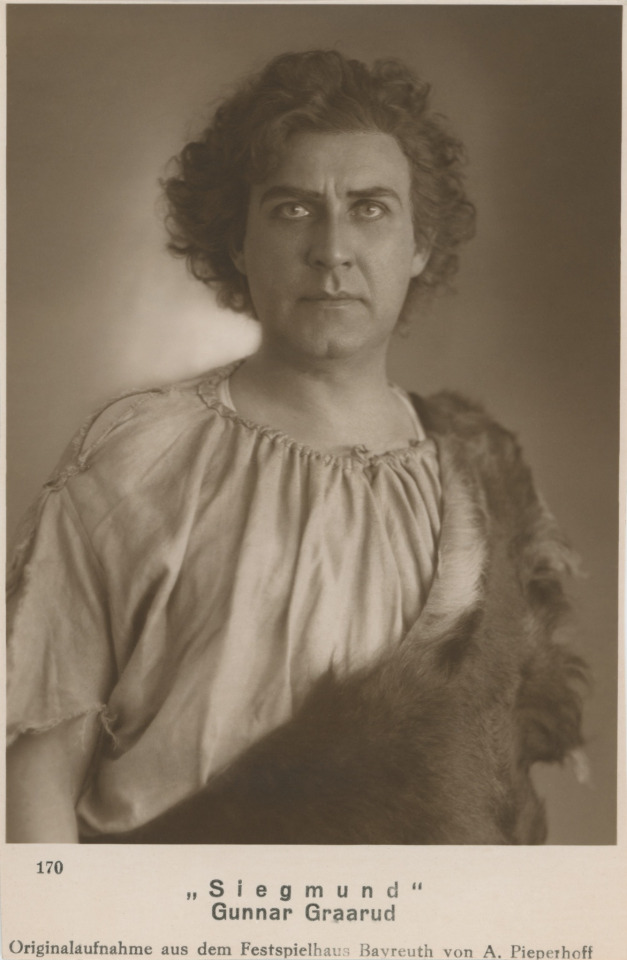

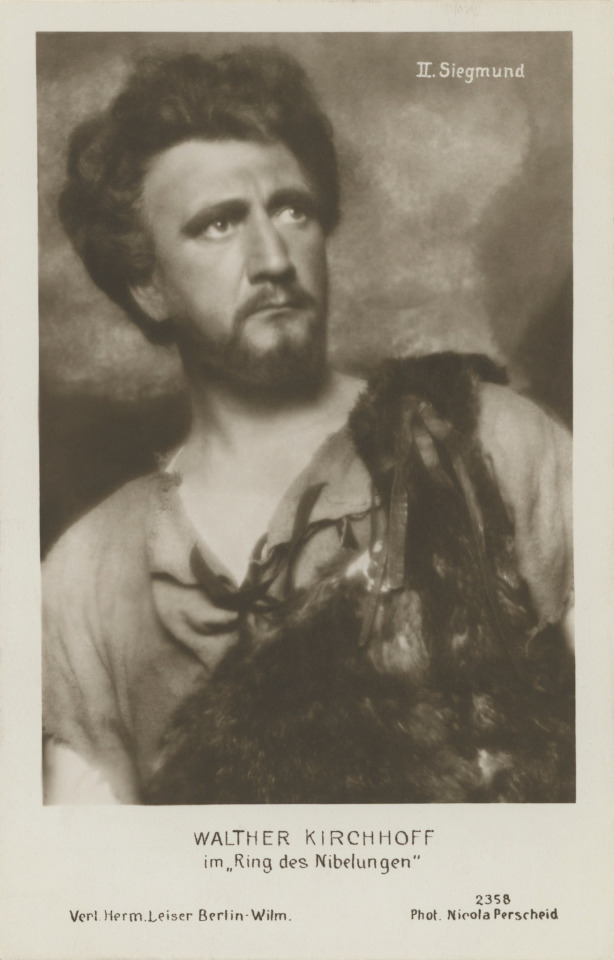

"Durch Wald und Wiese, Heide und Hain, jagte mich Sturm und starke Not" DIE WALKÜRE - R. WAGNER Here some Siegmunds (first act)

Adolf Wallnöfer as Siegmund; Prague, 1890

Ernst van Dyck or Dijck as Siegmund; Paris, 1892

Peter Cornelius as Siegmund; Bayreuth, 1906

Einar Forchhammer as Siegmund; Dresden, ?

Alois Pennarini as Siegmund; ?, ?

Alfred von Bary as Siegmund; Dresden, 1908

Johannes Sembach as Siegmund; Dresden, 1909

Paul Franz as Siegmund; Paris, ?

William Miller as Siegmund; Vienna, ?

Nicolai Reinfeld as Siegmund; Munich, ?

Alois Hadwiger as Siegmund; Graz, ?

Carl Jahn as Siegmund; Magdeburg, ?

Josef Schöffel as Siegmund; Karlsruhe, ?

Oskar Ralf as Siegmund; Bayreuth, 1928

Paul Hansen as Siegmund; Berlin, ?

Gunnar Graarud as Siegmund; Bayreuth, 1930

Paul Wiedemann as Siegmund; Bayreuth, 1928

Walther Kichhoff as Siegmund; Berlin, ?

Richard Schubert as Siegmund; Vienna, ?

Otto Wolf as Siegmund; Munich, ?

Willy Ulmer as Siegmund; Bayreuth, 1914

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Die Walküre#The Valkyrie#Musikdrama#Richard Wagner#Der Ring des Nibelungen#The Ring of the Nibelung#Ring cycle#Bayreuth Festspielhaus#Germanic myth#Bayreuth Festival#Norse mythology#Völsunga saga#Poetic Edda#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#opera history#musician

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reworking old oc concept stuff cuz i've missed drawing my guy Martin and cuz I can't contain Ring Cycle posting anymore

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In the first stages of the operas, Wotan is very concerned with the outcome of what is going to happen. He is frustrated, and he is always seeking to find a way to change the situation. But by this point in the opera, he has become more like Loge, more becoming involved in a scene and teasing, and then extracting himself, not taking any real direct action. And the reason is that Wotan, the Father, wants his son-his spiritual son, his Human Soul-to be strong, to develop his will, to not be weak, but to act when necessary, in the right way, and to know how to do it. This is why Wotan is around, is observing, is always watching, but never interferes. He never tells Siegfried what to do. He never tells him what to do. Meditate on that. Siegfried has to do what he thinks is right. He has to act, but on his own. Wotan does not want to develop a weak soul, a soul that is always lost, without direction, without strength. Wotan needs a warrior. Wotan needs Siegfried to have his own power.”

—Gnostic Instructor

#spirituality#esoteric#suffering#Siegfried#opera#ring of the Nibelungen#Richard Wagner#ring cycle#Wotan#norse mythology#Gnostic#gnosis#Glorian

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

In this week's column, I discuss a trip to Lyon, France, and finally understanding what it would take for me to consider myself a success as 'A Writer'.

#writing#writers life#writer#writers#lyon#france#flaneur#pub#richard wagner#der ring des nibelungen#ring cycle#opera#sir simon rattle

1 note

·

View note

Text

my opera girlies, do u ever get truly sick with rage and longing like in ur heart that a performer that means so much to you was never for you to see live? maybe they died decades before you, or they retired from singing the year you were born, or you just missed what you would love to see now by a few short years. there are recordings, thankfully, and u hold on to those because they're all there is, but the unity of music and stage performance, as is intended by musical theatre, is lost to time, and you were too late. anyway, </3

#currently ragesick over the fact that i missed evelyn herlitzius sing elektra and brünnhilde#if u dont know her imagine someone whose acting style is “women who are actually Absolute Creatures”#luckily theres a fcking brilliant elektra on dvd#but. what i'd give to see her brünnhilde.#i think her in die walküre could probably reduce me to a puddle of tears#bc i am a fan of creaturish little valkyries. dirty-kneed fierce teenage girls.#opera#classical music#richard wagner#opera shitpost#ring cycle#der ring des nibelungen#evelyn herlitzius

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sharing headcanons with you makes me realize...despite Gunther being the oldest Nibelung sibling (and possibly co-king even in his father's lifetime, ala Rosengarten) he's also the least specialized. Hagen/Hogni is the intense and super-strong one, Gernot/Gutthorm is the brave one, Giselher is the young one, and Gudrun/Kriemhild is the sweet one, and Gullrond if she's there might be the smart one. And then of course he gets the most awesome brother-in-law/blood brother who goes around fighting his battles for him. In real history, there's also the fact that his father in fact established their kingdom on the Rhineland, so Gibich must have had some big expectations for his eldest son. While he's no slouch, and rocks some serious musical talents in Norse sources, there's always this subtle feeling of inadequacy to Gunther. He's always pushing himself too hard but it turns out it's never enough. He must have some crippling feelings of inferiority that he's keeping behind that kingly facade.

(And now I imagine Oddrun giving him a "stop trying to be your father, live for yourself for once" speech, that results in him very impulsively doing the sneaky sneak with her.)

... okay, that last bit about Oddrun is just the sweetest thing! And very tragic, too, but I guess that comes with the territory. XD But jokes (and angst) aside, it really does sound like a very genuine and important connection and I love it.

As for Gunnar/Gunther himself, well...

I have to confess that, once, a lot of my ideas used to lowkey fall into the uncahritable "Gunnar/Gunther is kinda useless/weak" interpretation. But thanks to papers like “Mit (un)lobelichen êren”: Authority, Gender, and the Cause of Siegfried’s Death in the Nibelungenlied by Casey Alexis McCreary (about specifically Siegfried, Gunther, and Brunhild in the Nibelungenlied), as well as some influence from dear @galarix and @ivylili, I ended up re-evaluating him a lot both in the continental and Norse sources.

In the latter, I now find it really striking how he did want to leap over the flames, he did want to risk everything to go about the whole thing the right way. But he couldn't, and after that things increasingly spiralled out of his control in all the worst ways... and yet, even in the end, even with some admittedly pretty bad choices in the middle, he was no coward and went out with literally as much dignity as Hagen in the Nibelungenlied, using almost the exact same trick as him to defy his enemies and captors to the end.

In the former, I now find him not a bad king for Burgundy at all, but actually rather clever and resourceful in some moments. The paper I mentioned above actually does a very good job at arguing that he is pretty good at politics, it just that both Siegfried and Brunhild show their royal authority through heroic feats, with impressive shows of brute strength and charisma, so at first glance it's hard to recognize his qualities when they're the ones taking all the spotlight.

But actually having your own, solid good qualities and value, even when other people know about them and acknowledge them, isn't always going to be enough to make you feel satisfied with yourself...

I do still think he has an emotional, hotheaded, and impulsive side that he only learns to control slowly through the years and still gives him trouble sometimes even later on, tho. And as I previously said, I also see him as someone who was forced to take on the responsability of both his kingdom and his family too suddenly, and at too young an age, and always felt the weight of it all hanging above his head like the proverbial Sword of Damocles after that. And, taken together, that would all boil down to a lingering sense of self-doubt, I believe...

When it comes to his place in his family... or rather, families, I tend to see him as the brother who tries to be a proper head of the family, to bring honor and glory to his bloodline while also taking care of his siblings, but sometimes that all becomes too much to bear, and then he feels guilty about it because, is it even okay for him to feel that way? (It's certainly human and understandable, imo, and I think other characters would tell him that, too, but he'd rather keep that all inside until he blows up about some other, unrelated issues due to all the tension that's been building up, lol.)

The harp thing in the Norse stories is fun because it kinda looks like it comes from nowhere to give him a little bit of an Orpheus moment (soothing beasts with music, anyone?) as well as adding that tiny little bit of hope in desperate times only to rip it away right after. But I do like it a lot. I headcanon an interest and a talent for music for both Gunnar and Gunther that, unfortunately, neither of them ever really had the time or the conviction to make into more of a thing. Lately, tho, the multishipper in me who OTPs Volker/Hagen but also loves Gunther/Hagen has actually been playing with the idea of Volker and Gunther becoming closer (either as friends/friendly metamours, or as two people who, perhaps without even really realizing it, are inching their way into forming a throuple with their mutual partner) through Volker encouraging Gunther to revisit his old interest and reconnecting with what made him feel so good about it. But, well, that's another story...

And now, a bit of bonus Wagner because god, those three messed-up Gibichungs: Ring!Gunther is, like, the personification of an inferiority complex. He's literally introduced worrying that all his warring and conquering may not be enough (will maybe never be enough?) to live up to his late father's name. Hagen's mere suggestion that he's been keeping mum about some possible new conquest that could bring him honor pretty much sends him into a panic. He flatters Hagen (the same brother whose illegitimate and only half-human state he'll later callously throw in his face when all's said and done) by saying he's the lucky one who got all of their mother's cunning, but is it all flattery (especially when Alberich pretty much confirms the similarities between Hagen and Grimhild, and he doesn't really need to lie about it after doing his best as far as we know to isolate Hagen from full human beings) or is there some genuine envy there? Brunhhilde literally just needs to tell him he's shaming his family by refusing to kill Siegfried to have him wrapped around her little finger...

(Not that Ring!Hagen and Gutrune aren't also walking talking inferiority complexes in their own respective ways. I am unwell about that family.)

#ask#fate-magical-girls#norse mythology#nibelungenlied#ring cycle#gunnar#gunther#volker x hagen x gunther#(just a bit ;))

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

for those who haven't seen Wagner's Ring Cycle, Siegmund and Sieglinde were brother and sister

and also banging

that's right, they were the original Jaime and Cersei Lannister

(or Luke and Leia if you prefer that >:D )

La Révélation, Brünnhilde découvrant Sieglinde et Siegmund by Gaston Bussière (1894)

#ring cycle#wagner#richard wagner#der ring des nibelungen#a song of ice and fire#game of thrones#asoiaf#jaime lannister#cersei lannister#george rr martin#grrm#the ring of the nibelung#opera#star wars#luke skywalker#princess leia#leia organa#george lucas#art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was this many years old when I learned that Nibelungs are a real tribe that even lead into the Burgundian royal house.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I need a Ring staging that's specifically Dark Souls inspired

bonfire in every scene (except the very first one since it's underwater)

lit or unlit depending on what makes sense

the Gwyn vibes of Wotan

Brünnhilde linking the fire at the end

0 notes