#Property For Sale In France Property For Sale Property In France

Photo

Who would like their own 13th century hamlet about 125 mi. from Paris? It’s 990,000 € $1.f080M

The priory is now the main house.

This is ancient.

It’s nice, though, isn’t it?

It’s actually a spacious open concept.

The stairs are kind of dicey, though.

The stable is very old and sagging.

Lovely cottage.

Look at the nice deck and picturesque building.

Pretty little lake by the barn.

What an idyllic property.

Like a fairy tale.

https://www.patrice-besse.co.uk/property-for-sale-France/pays-de-loire/priory-chapel-15th-century-perche-region/

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Buy apartment in paris france | Living On The Cote d'Azur

#Properties for sale in france#realestate#Paris flat for sale#House for buying France#Property for sale in Dubai

0 notes

Text

Are you looking for New Apartment For Sale French Riviera? If yes, then visit Living on the Côte d'Azur portal! This boutique in real estate gives you an overall insight regarding the new apartments that are available for sale. Whether you want to invest in these luxurious properties for rent or live, we assist you in making the deal. Visit our website or drop your message on Whatsapp at +33783579579 for expert assistance!

#Real Estate French Riviera#Apartment For Sale French Riviera#Property For Sale In French Riviera#New Apartment For Sale French Riviera#Buyer Agent French Riviera#Retirement French Riviera Cote Azur#Personal Service Real Estate Buying France#Apartment For Sale Cannes#Villa For Sale Saint Tropez#Apartment For Sale Nice#Real Estate For Sale Sainte Maxime#Ibiza Villa For Sale#Immobilier Ibiza#Immobilier Portugal#Immobilier Maurice

0 notes

Text

This Property for Sale in Montenegro is a great investment opportunity for those looking to own a piece of real estate in a beautiful and growing country. Located in a prime location, this property offers stunning views of the Adriatic Sea and is surrounded by lush greenery. With a variety of amenities nearby, including restaurants, shops, and beaches, this property is perfect for those looking for a vacation home or a permanent residence.

0 notes

Text

"No one had fought more fanatically in the June days for the salvation of property and the restoration of credit than the Parisian petty bourgeois – keepers of cafes and restaurants, marchands de vins [wine merchants], small traders, shopkeepers, handicraftsman, etc. The shopkeeper had pulled himself together and marched against the barricades in order to restore the traffic which leads from the streets into the shop. But behind the barricade stood the customers and the debtors; before it the creditors of the shop. And when the barricades were thrown down and the workers were crushed and the shopkeepers, drunk with victory, rushed back to their shops, they found the entrance barred by a savior of property, an official agent of credit, who presented them with threatening notices: Overdue promissory note! Overdue house rent! Overdue bond! Doomed shop! Doomed shopkeeper!

Salvation of property! But the house they lived in was not their property; the shop they kept was not their property; the commodities they dealt in were not their property. Neither their business, nor the plate they ate from, nor the bed they slept on belonged to them any longer. It was precisely from them that this property had to be saved – for the house-owner who let the house, for the banker who discounted the promissory note, for the capitalist who made the advances in cash, for the manufacturer who entrusted the sale of his commodities to these retailers, for the wholesale dealer who had credited the raw materials to these handicraftsman. Restoration of credit! But credit, having regained strength, proved itself a vigorous and jealous god; it turned the debtor who could not pay out of his four walls, together with wife and child, surrendered his sham property to capital, and threw the man himself into the debtors’ prison, which had once more reared its head threateningly over the corpses of the June insurgents.

The petty bourgeois saw with horror that by striking down the workers they had delivered themselves without resistance into the hands of their creditors. Their bankruptcy, which since February had been dragging on in chronic fashion and had apparently been ignored, was openly declared after June."

-Marx, The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

French Style Chateau

Have you checked out the video yet!?

youtube

Now on to the primary suite, this main bedroom was huge, including a massive ensuite with a round stained glass window…as well as a few more photos of the staircase from the second floor!!

This mansion was built in 1985 on two lots in The Bridle Path neighbourhood of Toronto, Canada and was designed to resemble a French style chateau. The 30,000 square foot mega mansion had 10 bedrooms and 14 bathrooms, and was located on a huge four acre property that also included a tennis court. It also had a granite cobblestone driveway, a horseshoe staircase at the back and extensive gardens which completed the experience of living in a castle in France.

Originally built by Robert Campeau a financier and real estate developer. Robert began his career by building just one single house in 1949 in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. His company then known as Campeau Corp was also responsible for building Scotia Plaza, a hi rise built in 1988 in the financial district of Toronto, as well as the Harbour Castle Hotel in 1975. In the 80s, Campeau began a series of leveraged buyouts of companies, both in Canada and the United States. The final company was Federated Department Stores, the owners of Bloomingdale's for $7 billion. This was the beginning of the end for Campeau Corp, as they filed for Bankruptcy in 1990, one of the largest in history. Robert was forced to sell the home in 1990.

The home was purchased in 2002 by Harold and Sara Springer who entrusted architect Gordon Ridgely, interior designer Brian Gluckstein, and landscape architect Ronald Holbrook to bring their vision to life. They brought in 17th century antique furniture from france, original royal academy paintings, Italian marble and even crystal chandeliers.

Other features of the large house included a two-story indoor Olympic-size swimming pool with a retractable floor that converts into a ballroom. It also had an elevator, an oak wood bar, recording studio and even its very own bomb shelter!

The mansion has been featured in several movies including Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen's 'It Takes Two', 'Kissinger and Nixon', 'That Old Feeling' as well as most recently in an episode of Suits. A party was also held for Jane Fonda in the two-storey ballroom, which was then disassembled overnight so that Campeau could swim in the pool the next day with Pierre Elliott Trudeau.

The Springer's listed the chateau for sale including all of its contents starting in 2014 for $25 million and was last publicly listed in 2018 for $39,500,000. Finally, the home was purchased by Nascond Holdings in 2020 for $30.8 million.

Nascond Holdings is a company owned by the Muzzo Group which is a well known development company in the area. Marco Muzzo caused a drunk driving crash that killed four people and seriously injured two others. It was a very high profile incident several years ago, because of his ties to such a wealthy family. There was also a guest list of people found in the home including Marco's name as the host of the party.

The mansion was demolished shortly after my visit in August of 2022. Not much happened after that until more recently when some activity began to happen on the property. Ferris Rafauli who was also behind Drake's Bridle Path Mansion, is the designer and builder behind the new mansion that will take shape in the coming years.

#abandoned#urbex#urban exploring#urban exploration#bandos#abandoned buildings#abandoned places#forgotten#abandoned houses#forgotten buildings#abandoned homes#forgotten places#abandoned mansion#abandoned mansions#mansions#mega mansions#mega mansion#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter III. Economic Evolutions. — First Period. — The Division of Labor.

2. — Impotence of palliatives. — MM. Blanqui, Chevalier, Dunoyer, Rossi, and Passy.

All the remedies proposed for the fatal effects of parcellaire division may be reduced to two, which really are but one, the second being the inversion of the first: to raise the mental and moral condition of the workingman by increasing his comfort and dignity; or else, to prepare the way for his future emancipation and happiness by instruction.

We will examine successively these two systems, one of which is represented by M. Blanqui, the other by M. Chevalier.

M. Blanqui is a friend of association and progress, a writer of democratic tendencies, a professor who has a place in the hearts of the proletariat. In his opening discourse of the year 1845, M. Blanqui proclaimed, as a means of salvation, the association of labor and capital, the participation of the working man in the profits, — that is, a beginning of industrial solidarity. “Our century,” he exclaimed, “must witness the birth of the collective producer.” M. Blanqui forgets that the collective producer was born long since, as well as the collective consumer, and that the question is no longer a genetic, but a medical, one. Our task is to cause the blood proceeding from the collective digestion, instead of rushing wholly to the head, stomach, and lungs, to descend also into the legs and arms. Besides, I do not know what method M. Blanqui proposes to employ in order to realize his generous thought, — whether it be the establishment of national workshops, or the loaning of capital by the State, or the expropriation of the conductors of business enterprises and the substitution for them of industrial associations, or, finally, whether he will rest content with a recommendation of the savings bank to workingmen, in which case the participation would be put off till doomsday.

However this may be, M. Blanqui’s idea amounts simply to an increase of wages resulting from the copartnership, or at least from the interest in the business, which he confers upon the laborers. What, then, is the value to the laborer of a participation in the profits?

A mill with fifteen thousand spindles, employing three hundred hands, does not pay at present an annual dividend of twenty thousand francs. I am informed by a Mulhouse manufacturer that factory stocks in Alsace are generally below par and that this industry has already become a means of getting money by stock-jobbing instead of by labor. To SELL; to sell at the right time; to sell dear, — is the only object in view; to manufacture is only to prepare for a sale. When I assume, then, on an average, a profit of twenty thousand francs to a factory employing three hundred persons, my argument being general, I am twenty thousand francs out of the way. Nevertheless, we will admit the correctness of this amount. Dividing twenty thousand francs, the profit of the mill, by three hundred, the number of persons, and again by three hundred, the number of working days, I find an increase of pay for each person of twenty-two and one-fifth centimes, or for daily expenditure an addition of eighteen centimes, just a morsel of bread. Is it worth while, then, for this, to expropriate mill-owners and endanger the public welfare, by erecting establishments which must be insecure, since, property being divided into infinitely small shares, and being no longer supported by profit, business enterprises would lack ballast, and would be unable to weather commercial gales. And even if no expropriation was involved, what a poor prospect to offer the working class is an increase of eighteen centimes in return for centuries of economy; for no less time than this would be needed to accumulate the requisite capital, supposing that periodical suspensions of business did not periodically consume its savings!

The fact which I have just stated has been pointed out in several ways. M. Passy [13] himself took from the books of a mill in Normandy where the laborers were associated with the owner the wages of several families for a period of ten years, and he found that they averaged from twelve to fourteen hundred francs per year. He then compared the situation of mill-hands paid in proportion to the prices obtained by their employers with that of laborers who receive fixed wages, and found that the difference is almost imperceptible. This result might easily have been foreseen. Economic phenomena obey laws as abstract and immutable as those of numbers: it is only privilege, fraud, and absolutism which disturb the eternal harmony.

M. Blanqui, repentant, as it seems, at having taken this first step toward socialistic ideas, has made haste to retract his words. At the same meeting in which M. Passy demonstrated the inadequacy of cooperative association, he exclaimed: “Does it not seem that labor is a thing susceptible of organization, and that it is in the power of the State to regulate the happiness of humanity as it does the march of an army, and with an entirely mathematical precision? This is an evil tendency, a delusion which the Academy cannot oppose too strongly, because it is not only a chimera, but a dangerous sophism. Let us respect good and honest intentions; but let us not fear to say that to publish a book upon the organization of labor is to rewrite for the fiftieth time a treatise upon the quadrature of the circle or the philosopher’s stone.”

Then, carried away by his zeal, M. Blanqui finishes the destruction of his theory of cooperation, which M. Passy already had so rudely shaken, by the following example: “M. Dailly, one of the most enlightened of farmers, has drawn up an account for each piece of land and an account for each product; and he proves that within a period of thirty years the same man has never obtained equal crops from the same piece of land. The products have varied from twenty-six thousand francs to nine thousand or seven thousand francs, sometimes descending as low as three hundred francs. There are also certain products — potatoes, for instance — which fail one time in ten. How, then, with these variations and with revenues so uncertain, can we establish even distribution and uniform wages for laborers?....”

It might be answered that the variations in the product of each piece of land simply indicate that it is necessary to associate proprietors with each other after having associated laborers with proprietors, which would establish a more complete solidarity: but this would be a prejudgment on the very thing in question, which M. Blanqui definitively decides, after reflection, to be unattainable, — namely, the organization of labor. Besides, it is evident that solidarity would not add an obolus to the common wealth, and that, consequently, it does not even touch the problem of division.

In short, the profit so much envied, and often a very uncertain matter with employers, falls far short of the difference between actual wages and the wages desired; and M. Blanqui’s former plan, miserable in its results and disavowed by its author, would be a scourge to the manufacturing industry. Now, the division of labor being henceforth universally established, the argument is generalized, and leads us to the conclusion that misery is an effect of labor, as well as of idleness.

The answer to this is, and it is a favorite argument with the people: Increase the price of services; double and triple wages.

I confess that if such an increase was possible it would be a complete success, whatever M. Chevalier may have said, who needs to be slightly corrected on this point.

According to M. Chevalier, if the price of any kind of merchandise whatever is increased, other kinds will rise in a like proportion, and no one will benefit thereby.

This argument, which the economists have rehearsed for more than a century, is as false as it is old, and it belonged to M. Chevalier, as an engineer, to rectify the economic tradition. The salary of a head clerk being ten francs per day, and the wages of a workingman four, if the income of each is increased five francs, the ratio of their fortunes, which was formerly as one hundred to forty, will be thereafter as one hundred to sixty. The increase of wages, necessarily taking place by addition and not by proportion, would be, therefore, an excellent method of equalization; and the economists would deserve to have thrown back at them by the socialists the reproach of ignorance which they have bestowed upon them at random.

But I say that such an increase is impossible, and that the supposition is absurd: for, as M. Chevalier has shown very clearly elsewhere, the figure which indicates the price of the day’s labor is only an algebraic exponent without effect on the reality: and that which it is necessary first to endeavor to increase, while correcting the inequalities of distribution, is not the monetary expression, but the quantity of products. Till then every rise of wages can have no other effect than that produced by a rise of the price of wheat, wine, meat, sugar, soap, coal, etc., — that is, the effect of a scarcity. For what is wages?

It is the cost price of wheat, wine, meat, coal; it is the integrant price of all things. Let us go farther yet: wages is the proportionality of the elements which compose wealth, and which are consumed every day reproductively by the mass of laborers. Now, to double wages, in the sense in which the people understand the words, is to give to each producer a share greater than his product, which is contradictory: and if the rise pertains only to a few industries, a general disturbance in exchange ensues, — that is, a scarcity. God save me from predictions! but, in spite of my desire for the amelioration of the lot of the working class, I declare that it is impossible for strikes followed by an increase of wages to end otherwise than in a general rise in prices: that is as certain as that two and two make four. It is not by such methods that the workingmen will attain to wealth and — what is a thousand times more precious than wealth — liberty. The workingmen, supported by the favor of an indiscreet press, in demanding an increase of wages, have served monopoly much better than their own real interests: may they recognize, when their situation shall become more painful, the bitter fruit of their inexperience!

Convinced of the uselessness, or rather, of the fatal effects, of an increase of wages, and seeing clearly that the question is wholly organic and not at all commercial, M. Chevalier attacks the problem at the other end. He asks for the working class, first of all, instruction, and proposes extensive reforms in this direction.

Instruction! this is also M. Arago’s word to the workingmen; it is the principle of all progress. Instruction!.... It should be known once for all what may be expected from it in the solution of the problem before us; it should be known, I say, not whether it is desirable that all should receive it, — this no one doubts, — but whether it is possible.

To clearly comprehend the complete significance of M. Chevalier’s views, a knowledge of his methods is indispensable.

M. Chevalier, long accustomed to discipline, first by his polytechnic studies, then by his St. Simonian connections, and finally by his position in the University, does not seem to admit that a pupil can have any other inclination than to obey the regulations, a sectarian any other thought than that of his chief, a public functionary any other opinion than that of the government. This may be a conception of order as respectable as any other, and I hear upon this subject no expressions of approval or censure. Has M. Chevalier an idea to offer peculiar to himself? On the principle that all that is not forbidden by law is allowed, he hastens to the front to deliver his opinion, and then abandons it to give his adhesion, if there is occasion, to the opinion of authority. It was thus that M. Chevalier, before settling down in the bosom of the Constitution, joined M. Enfantin: it was thus that he gave his views upon canals, railroads, finance, property, long before the administration had adopted any system in relation to the construction of railways, the changing of the rate of interest on bonds, patents, literary property, etc.

M. Chevalier, then, is not a blind admirer of the University system of instruction, — far from it; and until the appearance of the new order of things, he does not hesitate to say what he thinks. His opinions are of the most radical.

M. Villemain had said in his report: “The object of the higher education is to prepare in advance a choice of men to occupy and serve in all the positions of the administration, the magistracy, the bar and the various liberal professions, including the higher ranks and learned specialties of the army and navy.”

“The higher education,” thereupon observes M. Chevalier, [14] “is designed also to prepare men some of whom shall be farmers, others manufacturers, these merchants, and those private engineers. Now, in the official programme, all these classes are forgotten. The omission is of considerable importance; for, indeed, industry in its various forms, agriculture, commerce, are neither accessories nor accidents in a State: they are its chief dependence.... If the University desires to justify its name, it must provide a course in these things; else an industrial university will be established in opposition to it.... We shall have altar against altar, etc....”

And as it is characteristic of a luminous idea to throw light on all questions connected with it, professional instruction furnishes M. Chevalier with a very expeditious method of deciding, incidentally, the quarrel between the clergy and the University on liberty of education.

“It must be admitted that a very great concession is made to the clergy in allowing Latin to serve as the basis of education. The clergy know Latin as well as the University; it is their own tongue. Their tuition, moreover, is cheaper; hence they must inevitably draw a large portion of our youth into their small seminaries and their schools of a higher grade....”

The conclusion of course follows: change the course of study, and you decatholicize the realm; and as the clergy know only Latin and the Bible, when they have among them neither masters of art, nor farmers, nor accountants; when, of their forty thousand priests, there are not twenty, perhaps, with the ability to make a plan or forge a nail, — we soon shall see which the fathers of families will choose, industry or the breviary, and whether they do not regard labor as the most beautiful language in which to pray to God.

Thus would end this ridiculous opposition between religious education and profane science, between the spiritual and the temporal, between reason and faith, between altar and throne, old rubrics henceforth meaningless, but with which they still impose upon the good nature of the public, until it takes offence.

M. Chevalier does not insist, however, on this solution: he knows that religion and monarchy are two powers which, though continually quarrelling, cannot exist without each other; and that he may not awaken suspicion, he launches out into another revolutionary idea, — equality.

“France is in a position to furnish the polytechnic school with twenty times as many scholars as enter at present (the average being one hundred and seventy-six, this would amount to three thousand five hundred and twenty). The University has but to say the word.... If my opinion was of any weight, I should maintain that mathematical capacity is much less special than is commonly supposed. I remember the success with which children, taken at random, so to speak, from the pavements of Paris, follow the teaching of La Martiniere by the method of Captain Tabareau.”

If the higher education, reconstructed according to the views of M. Chevalier, was sought after by all young French men instead of by only ninety thousand as commonly, there would be no exaggeration in raising the estimate of the number of minds mathematically inclined from three thousand five hundred and twenty to ten thousand; but, by the same argument, we should have ten thousand artists, philologists, and philosophers; ten thousand doctors, physicians, chemists, and naturalists; ten thousand economists, legists, and administrators; twenty thousand manufacturers, foremen, merchants, and accountants; forty thousand farmers, wine-growers, miners, etc., — in all, one hundred thousand specialists a year, or about one-third of our youth. The rest, having, instead of special adaptations, only mingled adaptations, would be distributed indifferently elsewhere.

It is certain that so powerful an impetus given to intelligence would quicken the progress of equality, and I do not doubt that such is the secret desire of M. Chevalier. But that is precisely what troubles me: capacity is never wanting, any more than population, and the problem is to find employment for the one and bread for the other. In vain does M. Chevalier tell us: “The higher education would give less ground for the complaint that it throws into society crowds of ambitious persons without any means of satisfying their desires, and interested in the overthrow of the State; people without employment and unable to get any, good for nothing and believing themselves fit for anything, especially for the direction of public affairs. Scientific studies do not so inflate the mind. They enlighten and regulate it at once; they fit men for practical life....” Such language, I reply, is good to use with patriarchs: a professor of political economy should have more respect for his position and his audience. The government has only one hundred and twenty offices annually at its disposal for one hundred and seventy-six students admitted to the polytechnic school: what, then, would be its embarrassment if the number of admissions was ten thousand, or even, taking M. Chevalier’s figures, three thousand five hundred? And, to generalize, the whole number of civil positions is sixty thousand, or three thousand vacancies annually; what dismay would the government be thrown into if, suddenly adopting the reformatory ideas of M. Chevalier, it should find itself besieged by fifty thousand office-seekers! The following objection has often been made to republicans without eliciting a reply: When everybody shall have the electoral privilege, will the deputies do any better, and will the proletariat be further advanced? I ask the same question of M. Chevalier: When each academic year shall bring you one hundred thousand fitted men, what will you do with them?

To provide for these interesting young people, you will go down to the lowest round of the ladder. You will oblige the young man, after fifteen years of lofty study, to begin, no longer as now with the offices of aspirant engineer, sub-lieutenant of artillery, second lieutenant, deputy, comptroller, general guardian, etc., but with the ignoble positions of pioneer, train-soldier, dredger, cabin-boy, fagot-maker, and exciseman. There he will wait, until death, thinning the ranks, enables him to advance a step. Under such circumstances a man, a graduate of the polytechnic school and capable of becoming a Vauban, may die a laborer on a second class road, or a corporal in a regiment

Oh! how much more prudent Catholicism has shown itself, and how far it has surpassed you all, St. Simonians, republicans, university men, economists, in the knowledge of man and society! The priest knows that our life is but a voyage, and that our perfection cannot be realized here below; and he contents himself with outlining on earth an education which must be completed in heaven. The man whom religion has moulded, content to know, do, and obtain what suffices for his earthly destiny, never can become a source of embarrassment to the government: rather would he be a martyr. O beloved religion! is it necessary that a bourgeoisie which stands in such need of you should disown you?...

Into what terrible struggles of pride and misery does this mania for universal instruction plunge us! Of what use is professional education, of what good are agricultural and commercial schools, if your students have neither employment nor capital? And what need to cram one’s self till the age of twenty with all sorts of knowledge, then to fasten the threads of a mule-jenny or pick coal at the bottom of a pit? What! you have by your own confession only three thousand positions annually to bestow upon fifty thousand possible capacities, and yet you talk of establishing schools! Cling rather to your system of exclusion and privilege, a system as old as the world, the support of dynasties and patriciates, a veritable machine for gelding men in order to secure the pleasures of a caste of Sultans. Set a high price upon your teaching, multiply obstacles, drive away, by lengthy tests, the son of the proletaire whom hunger does not permit to wait, and protect with all your power the ecclesiastical schools, where the students are taught to labor for the other life, to cultivate resignation, to fast, to respect those in high places, to love the king, and to pray to God. For every useless study sooner or later becomes an abandoned study: knowledge is poison to slaves.

Surely M. Chevalier has too much sagacity not to have seen the consequences of his idea. But he has spoken from the bottom of his heart, and we can only applaud his good intentions: men must first be men; after that, he may live who can.

Thus we advance at random, guided by Providence, who never warns us except with a blow: this is the beginning and end of political economy.

Contrary to M. Chevalier, professor of political economy at the College of France, M. Dunoyer, an economist of the Institute, does not wish instruction to be organized. The organization of instruction is a species of organization of labor; therefore, no organization. Instruction, observes M. Dunoyer, is a profession, not a function of the State; like all professions, it ought to be and remain free. It is communism, it is socialism, it is the revolutionary tendency, whose principal agents have been Robespierre, Napoleon, Louis XVIII, and M. Guizot, which have thrown into our midst these fatal ideas of the centralization and absorption of all activity in the State. The press is very free, and the pen of the journalist is an object of merchandise; religion, too, is very free, and every wearer of a gown, be it short or long, who knows how to excite public curiosity, can draw an audience about him. M. Lacordaire has his devotees, M. Leroux his apostles, M. Buchez his convent. Why, then, should not instruction also be free? If the right of the instructed, like that of the buyer, is unquestionable, and that of the instructor, who is only a variety of the seller, is its correlative, it is impossible to infringe upon the liberty of instruction without doing violence to the most precious of liberties, that of the conscience. And then, adds M. Dunoyer, if the State owes instruction to everybody, it will soon be maintained that it owes labor; then lodging; then shelter.... Where does that lead to?

The argument of M. Dunoyer is irrefutable: to organize instruction is to give to every citizen a pledge of liberal employment and comfortable wages; the two are as intimately connected as the circulation of the arteries and the veins. But M. Dunoyer’s theory implies also that progress belongs only to a certain select portion of humanity, and that barbarism is the eternal lot of nine-tenths of the human race. It is this which constitutes, according to M. Dunoyer, the very essence of society, which manifests itself in three stages, religion, hierarchy, and beggary. So that in this system, which is that of Destutt de Tracy, Montesquieu, and Plato, the antinomy of division, like that of value, is without solution.

It is a source of inexpressible pleasure to me, I confess, to see M. Chevalier, a defender of the centralization of instruction, opposed by M. Dunoyer, a defender of liberty; M. Dunoyer in his turn antagonized by M. Guizot; M. Guizot, the representative of the centralizers, contradicting the Charter, which posits liberty as a principle; the Charter trampled under foot by the University men, who lay sole claim to the privilege of teaching, regardless of the express command of the Gospel to the priests: Go and teach. And above all this tumult of economists, legislators, ministers, academicians, professors, and priests, economic Providence giving the lie to the Gospel, and shouting: Pedagogues! what use am I to make of your instruction?

Who will relieve us of this anxiety? M. Rossi leans toward eclecticism: Too little divided, he says, labor remains unproductive; too much divided, it degrades man. Wisdom lies between these extremes; in medio virtus. Unfortunately this intermediate wisdom is only a small amount of poverty joined with a small amount of wealth, so that the condition is not modified in the least. The proportion of good and evil, instead of being as one hundred to one hundred, becomes as fifty to fifty: in this we may take, once for all, the measure of eclecticism. For the rest, M. Rossi’s juste-milieu is in direct opposition to the great economic law: To produce with the least possible expense the greatest possible quantity of values.... Now, how can labor fulfil its destiny without an extreme division? Let us look farther, if you please.

“All economic systems and hypotheses,” says M. Rossi, “belong to the economist, but the intelligent, free, responsible man is under the control of the moral law... Political economy is only a science which examines the relations of things, and draws conclusions therefrom. It examines the effects of labor; in the application of labor, you should consider the importance of the object in view. When the application of labor is unfavorable to an object higher than the production of wealth, it should not be applied... Suppose that it would increase the national wealth to compel children to labor fifteen hours a day: morality would say that that is not allowable. Does that prove that political economy is false? No; that proves that you confound things which should be kept separate.”

If M. Rossi had a little more of that Gallic simplicity so difficult for foreigners to acquire, he would very summarily have thrown his tongue to the dogs, as Madame de Sevigne said. But a professor must talk, talk, talk, not for the sake of saying anything, but in order to avoid silence. M. Rossi takes three turns around the question, then lies down: that is enough to make certain people believe that he has answered it.

It is surely a sad symptom for a science when, in developing itself according to its own principles, it reaches its object just in time to be contradicted by another; as, for example, when the postulates of political economy are found to be opposed to those of morality, for I suppose that morality is a science as well as political economy. What, then, is human knowledge, if all its affirmations destroy each other, and on what shall we rely? Divided labor is a slave’s occupation, but it alone is really productive; undivided labor belongs to the free man, but it does not pay its expenses. On the one hand, political economy tells us to be rich; on the other, morality tells us to be free; and M. Rossi, speaking in the name of both, warns us at the same time that we can be neither free nor rich, for to be but half of either is to be neither. M. Rossi’s doctrine, then, far from satisfying this double desire of humanity, is open to the objection that, to avoid exclusiveness, it strips us of everything: it is, under another form, the history of the representative system.

But the antagonism is even more profound than M. Rossi has supposed. For since, according to universal experience (on this point in harmony with theory), wages decrease in proportion to the division of labor, it is clear that, in submitting ourselves to parcellaire slavery, we thereby shall not obtain wealth; we shall only change men into machines: witness the laboring population of the two worlds. And since, on the other hand, without the division of labor, society falls back into barbarism, it is evident also that, by sacrificing wealth, we shall not obtain liberty: witness all the wandering tribes of Asia and Africa. Therefore it is necessary — economic science and morality absolutely command it — for us to solve the problem of division: now, where are the economists? More than thirty years ago, Lemontey, developing a remark of Smith, exposed the demoralizing and homicidal influence of the division of labor. What has been the reply; what investigations have been made; what remedies proposed; has the question even been understood?

Every year the economists report, with an exactness which I would commend more highly if I did not see that it is always fruitless, the commercial condition of the States of Europe. They know how many yards of cloth, pieces of silk, pounds of iron, have been manufactured; what has been the consumption per head of wheat, wine, sugar, meat: it might be said that to them the ultimate of science is to publish inventories, and the object of their labor is to become general comptrollers of nations. Never did such a mass of material offer so fine a field for investigation. What has been found; what new principle has sprung from this mass; what solution of the many problems of long standing has been reached; what new direction have studies taken?

One question, among others, seems to have been prepared for a final judgment, — pauperism. Pauperism, of all the phenomena of the civilized world, is today the best known: we know pretty nearly whence it comes, when and how it arrives, and what it costs; its proportion at various stages of civilization has been calculated, and we have convinced ourselves that all the specifics with which it hitherto has been fought have been impotent. Pauperism has been divided into genera, species, and varieties: it is a complete natural history, one of the most important branches of anthropology. Well I the unquestionable result of all the facts collected, unseen, shunned, covered by the economists with their silence, is that pauperism is constitutional and chronic in society as long as the antagonism between labor and capital continues, and that this antagonism can end only by the absolute negation of political economy. What issue from this labyrinth have the economists discovered?

This last point deserves a moment’s attention.

In primitive communism misery, as I have observed in a preceding paragraph, is the universal condition.

Labor is war declared upon this misery.

Labor organizes itself, first by division, next by machinery, then by competition, etc.

Now, the question is whether it is not in the essence of this organization, as given us by political economy, at the same time that it puts an end to the misery of some, to aggravate that of others in a fatal and unavoidable manner. These are the terms in which the question of pauperism must be stated, and for this reason we have undertaken to solve it.

What means, then, this eternal babble of the economists about the improvidence of laborers, their idleness, their want of dignity, their ignorance, their debauchery, their early marriages, etc.? All these vices and excesses are only the cloak of pauperism; but the cause, the original cause which inexorably holds four-fifths of the human race in disgrace, — what is it? Did not Nature make all men equally gross, averse to labor, wanton, and wild? Did not patrician and proletaire spring from the same clay? Then how happens it that, after so many centuries, and in spite of so many miracles of industry, science, and art, comfort and culture have not become the inheritance of all? How happens it that in Paris and London, centres of social wealth, poverty is as hideous as in the days of Caesar and Agricola? Why, by the side of this refined aristocracy, has the mass remained so uncultivated? It is laid to the vices of the people: but the vices of the upper class appear to be no less; perhaps they are even greater. The original stain affected all alike: how happens it, once more, that the baptism of civilization has not been equally efficacious for all? Does this not show that progress itself is a privilege, and that the man who has neither wagon nor horse is forced to flounder about for ever in the mud? What do I say? The totally destitute man has no desire to improve: he has fallen so low that ambition even is extinguished in his heart.

“Of all the private virtues,” observes M. Dunoyer with infinite reason, “the most necessary, that which gives us all the others in succession, is the passion for well-being, is the violent desire to extricate one’s self from misery and abjection, is that spirit of emulation and dignity which does not permit men to rest content with an inferior situation.... But this sentiment, which seems so natural, is unfortunately much less common than is thought. There are few reproaches which the generality of men deserve less than that which ascetic moralists bring against them of being too fond of their comforts: the opposite reproach might be brought against them with infinitely more justice.... There is even in the nature of men this very remarkable feature, that the less their knowledge and resources, the less desire they have of acquiring these. The most miserable savages and the least enlightened of men are precisely those in whom it is most difficult to arouse wants, those in whom it is hardest to inspire the desire to rise out of their condition; so that man must already have gained a certain degree of comfort by his labor, before he can feel with any keenness that need of improving his condition, of perfecting his existence, which I call the love of well-being.” [15]

Thus the misery of the laboring classes arises in general from their lack of heart and mind, or, as M. Passy has said somewhere, from the weakness, the inertia of their moral and intellectual faculties. This inertia is due to the fact that the said laboring classes, still half savage, do not have a sufficiently ardent desire to ameliorate their condition: this M. Dunoyer shows. But as this absence of desire is itself the effect of misery, it follows that misery and apathy are each other’s effect and cause, and that the proletariat turns in a circle.

To rise out of this abyss there must be either well-being, — that is, a gradual increase of wages, — or intelligence and courage, — that is, a gradual development of faculties: two things diametrically opposed to the degradation of soul and body which is the natural effect of the division of labor. The misfortune of the proletariat, then, is wholly providential, and to undertake to extinguish it in the present state of political economy would be to produce a revolutionary whirlwind.

For it is not without a profound reason, rooted in the loftiest considerations of morality, that the universal conscience, expressing itself by turns through the selfishness of the rich and the apathy of the proletariat, denies a reward to the man whose whole function is that of a lever and spring. If, by some impossibility, material well-being could fall to the lot of the parcellaire laborer, we should see something monstrous happen: the laborers employed at disagreeable tasks would become like those Romans, gorged with the wealth of the world, whose brutalized minds became incapable of devising new pleasures. Well-being without education stupefies people and makes them insolent: this was noticed in the most ancient times. Incrassatus est, et recalcitravit, says

Deuteronomy. For the rest, the parcellaire laborer has judged himself: he is content, provided he has bread, a pallet to sleep on, and plenty of liquor on Sunday. Any other condition would be prejudicial to him, and would endanger public order.

At Lyons there is a class of men who, under cover of the monopoly given them by the city government, receive higher pay than college professors or the head-clerks of the government ministers: I mean the porters. The price of loading and unloading at certain wharves in Lyons, according to the schedule of the Rigues or porters’ associations, is thirty centimes per hundred kilogrammes. At this rate, it is not seldom that a man earns twelve, fifteen, and even twenty francs a day: he only has to carry forty or fifty sacks from a vessel to a warehouse. It is but a few hours’ work. What a favorable condition this would be for the development of intelligence, as well for children as for parents, if, of itself and the leisure which it brings, wealth was a moralizing principle! But this is not the case: the porters of Lyons are today what they always have been, drunken, dissolute, brutal, insolent, selfish, and base. It is a painful thing to say, but I look upon the following declaration as a duty, because it is the truth: one of the first reforms to be effected among the laboring classes will be the reduction of the wages of some at the same time that we raise those of others. Monopoly does not gain in respectability by belonging to the lowest classes of people, especially when it serves to maintain only the grossest individualism. The revolt of the silk-workers met with no sympathy, but rather hostility, from the porters and the river population generally. Nothing that happens off the wharves has any power to move them. Beasts of burden fashioned in advance for despotism, they will not mingle with politics as long as their privilege is maintained. Nevertheless, I ought to say in their defence that, some time ago, the necessities of competition having brought their prices down, more social sentiments began to awaken in these gross natures: a few more reductions seasoned with a little poverty, and the Rigues of Lyons will be chosen as the storming-party when the time comes for assaulting the bastilles.

In short, it is impossible, contradictory, in the present system of society, for the proletariat to secure well-being through education or education through well-being. For, without considering the fact that the proletaire, a human machine, is as unfit for comfort as for education, it is demonstrated, on the one hand, that his wages continually tend to go down rather than up, and, on the other, that the cultivation of his mind, if it were possible, would be useless to him; so that he always inclines towards barbarism and misery. Everything that has been attempted of late years in France and England with a view to the amelioration of the condition of the poor in the matters of the labor of women and children and of primary instruction, unless it was the fruit of some hidden thought of radicalism, has been done contrary to economic ideas and to the prejudice of the established order. Progress, to the mass of laborers, is always the book sealed with the seven seals; and it is not by legislative misconstructions that the relentless enigma will be solved.

For the rest, if the economists, by exclusive attention to their old routine, have finally lost all knowledge of the present state of things, it cannot be said that the socialists have better solved the antinomy which division of labor raised. Quite the contrary, they have stopped with negation; for is it not perpetual negation to oppose, for instance, the uniformity of parcellaire labor with a so-called variety in which each one can change his occupation ten, fifteen, twenty times a day at will?

As if to change ten, fifteen, twenty times a day from one kind of divided labor to another was to make labor synthetic; as if, consequently, twenty fractions of the day’s work of a manual laborer could be equal to the day’s work of an artist! Even if such industrial vaulting was practicable, — and it may be asserted in advance that it would disappear in the presence of the necessity of making laborers responsible and therefore functions personal, — it would not change at all the physical, moral, and intellectual condition of the laborer; the dissipation would only be a surer guarantee of his incapacity and, consequently, his dependence. This is admitted, moreover, by the organizers, communists, and others. So far are they from pretending to solve the antinomy of division that all of them admit, as an essential condition of organization, the hierarchy of labor, — that is, the classification of laborers into parcellaires and generalizers or organizers, — and in all utopias the distinction of capacities, the basis or everlasting excuse for inequality of goods, is admitted as a pivot. Those reformers whose schemes have nothing to recommend them but logic, and who, after having complained of the simplism, monotony, uniformity, and extreme division of labor, then propose a plurality as a SYNTHESIS, — such inventors, I say, are judged already, and ought to be sent back to school.

But you, critic, the reader undoubtedly will ask, what is your solution? Show us this synthesis which, retaining the responsibility, the personality, in short, the specialty of the laborer, will unite extreme division and the greatest variety in one complex and harmonious whole.

My reply is ready: Interrogate facts, consult humanity: we can choose no better guide. After the oscillations of value, division of labor is the economic fact which influences most perceptibly profits and wages. It is the first stake driven by Providence into the soil of industry, the starting-point of the immense triangulation which finally must determine the right and duty of each and all. Let us, then, follow our guides, without which we can only wander and lose ourselves.

Tu longe seggere, et vestigia semper adora.

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Political gains & contents of the Concordat of 1801

Agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII on 15 July 1801 in Paris.

Rome seems to have made immense sacrifices. The first advantage won by the First Consul was to seal, by the very act of signing an agreement, the recognition of the French Republic by the Holy See, and hence the rupture of the traditional alliance between Rome and the legitimate monarchies. It was a disastrous blow to French royalism in exile, for it freed the faithful in the interior from scruples about the regime of the Year VIII.

The second advantage was to confirm a church of salaried public servants, amenable to the State and having mainly sociological functions. Here we see a continuation of the Gallican tradition, but also of the thought of philosophes who had urged both the submission of the clergy to the State and its integration within it. The refusal to reestablish the religious orders meant also the rejection of any ecclesiastical life that might escape the authority of the bishops. Even the cathedral chapters were reduced to decorative functions.

Thirdly, no question was raised about the sale of the former Church properties, a matter of great importance for strengthening the prestige of Bonaparte in the eyes of the property-owning segments of French society.

Pius VII, for his part, failed to obtain the recognition of Catholicism as the state religion. He agreed to use his authority for what Consalvi called “the massacre of a whole episcopate,” by requiring the resignation of all French bishops, both constitutional and refractory, since Napoleon judged such a step to be indispensable for effacing all traces of the revolutionary schism. It is right to see in this operation an encouragement to ultramontanism, for it affirmed the powers of the Pope over the French Church. But it also encouraged a tendency in the French episcopate, that is, a whole ecclesiological movement for appeal to an ecumenical council in matters of discipline.

Among the numerous provisions of the Articles we may point out those that legalized all forms of worship in France, and those that strictly subordinated the lower clergy to the bishops (“prefects in violet robes”): only a fifth of the parish priests received the title of curé, and with it secure tenure; all others became simple desservants of succursales, that is assistant pastors.

This is what the Church got out of the deal:

What then did the Pope gain in this Concordat, “more likely to raise difficulties than to solve them” (Bernard Plongeron). Maintenance of the unity of the Roman Church, which a consolidation of the schism in France might have ruined forever; recognition of canonical investiture, which allowed the Pope to overcome the zelanti among the cardinals who opposed the Concordat but favored a reinforcement of spiritual authority; and resumption of regular pastoral life in France, where the new administrative and social status of the priest encouraged a growing number of ordinations, which reached several hundred by the end of the Empire.

Pius VII in any case remained attached to the results accomplished, a fact that deprived the small “shadow church” opposed to the Concordat of the possibility of resistance. His continuing attitude was shown later in his willingness to come to Paris for the Emperor’s coronation.

Source: Louis Bergeron, L'Episode napoléonien. Aspects, intérieurs: 1799-1815

English: France Under Napoleon, tr. R. R. Palmer

#Louis Bergeron#Bergeron#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#french empire#L'Episode napoléonien. Aspects intérieurs: 1799-1815#France Under Napoleon#Napoleon’s reforms#reforms#Concordat#christianity#Christian#19th century#histriy#Catholic Church#Catholic#history#1800s#french revolution#Pope Pius VII#Pius VII#napoleonic reforms

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

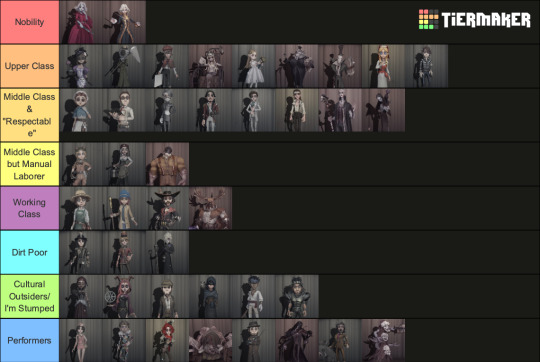

Social Class and Income Levels of IDV Characters

I’m back again with a long, intensive IDV post, this time regarding the quality of life most of Identity V’s characters would likely have led before coming to the manor. This list is not definitive and is based on a little guesswork in some areas, and also doesn’t include every single character, as I couldn’t find relevant information for every career, but I think provides an interesting look at character backgrounds, the sorts of resources they would have access to, and what life was like in the 1890s.

This post assumes that the vast majority of the characters live in the United Kingdom and that most of them were born there. As discussed in an earlier theory post, Oletus Manor is 100% in England and the DeRoss Couple and their daughter were English aristocrats. It also refers to fairly readily available information that can be found in various characters’ deduction systems, seasonal events, background and official videos, and birthday letters.

Lots- and I mean LOTS- of info below.

First, a few notes about the class system in the late Victorian United Kingdom:

- Class was highly stratified, and moving up the social ladder was extremely difficult.

- Class was not necessarily just tied to income. Upbringing, family background, etc were just as large a determinant, which is why you might have an impoverished aristocrat with tons of property but no income who would still be welcome in elite social circles, whereas an up-and coming business owner bringing in £3,000/year would be shunned. Class was who got invited over to dinner; class was whether or not you’d been educated, and if you had to work with your hands.

The Upper Class/Aristocracy/Nobility:

- The top of the class system under the royal family (boo). Men might hold political positions, but members of this class would not have careers, as such. These characters likely have a passive income from investments or land owned and generational wealth. hey own one or more homes and employ extensive live-in household staff, including maids, butlers, drivers, cooks, gardeners etc.They can travel widely and partake of various entertainments, having time to cultivate talents in the arts.

Mary: She is, or believes herself to be (??), Marie Antoinette, an Austrian princess and the Queen of France. Antoinette was infamous for her lavish lifestyle and voracious appetite for fashion.

Joseph: He is referred to as a Count, but French nobility does not actually use that exact title. It’s possible he is a Comte, which is the equivalent of an Earl/Count in England. Either way, this is a middle of the ranking noble title. In the 2021 Christmas Event, he mentions his family owning several manors, so the Desaulniers family has, or had, a considerable amount of property.

An interesting thing that makes me wonder if his family’s wealth is depleted is that he consistently dresses in extremely outdated clothing, but I believe that speaks more to his sentimental obsession with the past than anything else.

Chloe/Vera: The real Vera had the capital to open a store front to sell Chloe’s perfumes. There is no mention of either daughter working prior to this, and the family employs several maids. Presumably, Chloe’s perfumes were a good money maker, as the 1890s marked the “Golden Era” of perfume production and sales. It is unusual, but not impossible, that an upper-class woman would own a business.

Melly: A successful social climber who began as a maid before marrying her employer, who owned a manor. She is well educated, to the extent she has been invited to lecture at a college or university.

Edgar: Edgar does not paint to generate income. His family was able to afford a long-term art tutor for him, and he is not interested in the prize money offered by the manor because his family’s wealth is more than sufficient. He is squarely in the aristocrat category, and enjoyed a lifestyle most of the other characters could only have dreamed of, at least in a fiscal sense.

Galatea: Another individual who pursued art as a passion or hobby rather than actual trade.This would simply not be realistic for anyone outside the upper classes.

Memory/Alice DeRoss: Her father possessed the title of Baron. Her mother is depicted in TOR with an upper-class English accent. Her parents own Oletus manor, which they were able to purchase, and employ two known servants (Burke and Bane). Running such a large estate would require an army of maids, cooks, gardeners, etc, who are not directly mentioned but implied.

Keigan: In her background video, we see her family in very formal dress at a large, lavishly set dinner table. Her brother holds the position of judge at a major court, which brought with it a great deal of respect and import. The average clerk made very little money, but it’s implied she is acting as his unofficial assistant/helper due to sisterly obligation, and does not want for money.

Jack: a bit of conjecture, but Jack at least played at being an artist, and takes on the role of a gentleman. It does not appear he needed to work to support himself.

Annie: Her father is a painter of some note, and her mother was a noted society beauty who left her a considerable inheritance that her father and fiancé conspired to get their hands on.

Luca: A fallen aristocrat with a mother of noble birth. His interests include piano, books, and experiments, all of which point to a privileged upbringing. Only someone with resources could run experiments and futz about with specialized equipment, which is why so many scientists from past eras came from upper class or even noble backgrounds. His father, Herman, blew through their fortune, and after Luca’s incident with Alva, he would not be a socially accepted individual.

The “Educated” Middle Class:

-Individuals or households with an income up to around £1000/ year. The wives do not have to work, but see to the home (oversee staff) and partake in social obligations, plan parties, and help educate the children in the arts. Daughters may become teachers or governesses if they don’t marry or prior to marriage, or in wealthier families, not work at all. They own their home and have live-in staff, such a cook and maids. ( see model yearly budget for a man making £700/year here.) Vacations, domestic and abroad, and high-end entertainments are accessible. They have some time for hobbies, and probably play a musical instrument if also from a culturally upper-middle class family, such as a piano, violin, harpsichord, etc. Guitars, flutes etc would not be counted here, as they are more “common” instruments. These individuals might move in some of the same social circles as the aristocracy.

Emily: A well established Doctor working in a city hospital could expect to make up to £1000/ year, putting them at the upper end of the middle class. However, an independent Doctor would make much less, and in rural areas, would often be paid in food or services. Given Emily’s difficulties keeping her clinic open, she lingers in the border between being a member of the middle class “culturally”— we know she came from a middle class family and is educated— but she struggles with money and lacks for stability like some of the folks in the lower middle and many in the working classes. Despite a low income, her education would mean she’d be welcome in polite society.

Freddy: A top-payed Lawyer could make £1,200/ year, but Freddy is a bit of a failure. His actual financial status cannot be determined, but he is, like Emily, culturally middle class due to his education and white-collar job.

Aesop: Aesop Carl? relatively loaded, actually. The Victorian era was great for the funeral industry. The elaborate rituals surrounding mourning meant that those in adjacent careers were always busy, and it was fashionable to send off a loved one in great style. The lower classes imitated the lavish funerals of the wealthy, often bankrupting themselves in the process, because it was considered shameful to be unable to lay someone to rest properly, and reputation and respectability were of vital importance in the Victorian United Kingdom.

As with today, there was an outcry about the funerary industry driving up prices and taking advantage of grieving people to line their pockets even more.A nice funeral, modest but respectable, cost about £11, and embalming services were an additional £10. A funeral with all the bells and whistles would fall at £21. A skilled Embalmer is capable of tending to several corpses in a day. Even if Aesop and Jerry only handled 50 corpses a year, they’d be making £500. A modern mortician handles about 150 bodies a year, so that’s a cool £1500/year for them. This would mean a nice house with a garden, a maid, and a cook at the very least, presuming Jerry risked having staff around that could possibly catch him on his bullshit. (Though I guess he could just kill them too and replace them with someone who didn’t know better. Fucking Jerry). At least even if he was emotionally starved and groomed into becoming a murderer, he was still eating well, could have nice clothes, and take vacations?

Another downside though is that then as is often true now, people did not want to socialize with someone who worked closely with dead bodies, and funeral industry workers were often ostracized, making his position here a little tenuous.

His mother’s family appears to have been upper or middle class, as suggested by Aesop’s dance emote, in which he performs a pirouette. Ballet was an upper-class entertainment, and formal dance training would not be accessible to children of poorer families, and I doubt Jerry was enrolling him in a lot of extracurriculars, meaning he must have learned while still in his mother’s care.

Jose: A First Officer could make around £900/ year. His family was employed by the Queen, and once had a stellar reputation. Although sailors worked with their hands, a high-ranked officer on a ship was seen as fairly respectable.

Orpheus: Some conjecture here. Orpheus is, like Melly, someone who successfully moved up the social ladder, first being adopted by the aristocratic DeRoss couple and then making a name for himself as a novelist. His Survivor version is well-dressed in neat white clothes that would require maintenance and be antithetical to manual work that would dirty them.

Luchino: As a professor, he is educated and respectable, even if his methods are unconventional and his manner of dress hardly appropriate for the classroom.

Alva: He was a student together with Luca’s father, Herman, at an institute of higher education, meaning he is most likely from a family who could afford the expense of educating him.

EDIT: @ivy0309 pointed out that in the Mandarin version of Alva’s first deduction, the language states he comes from an impoverished place, meaning he was probably granted a scholarship and is another case of a successful social climber.

Ann: Ann’s deductions mention she wore exquisite and ornate mourning clothes after the deaths of her parents, suggesting her family had the money for funerals with pomp. She is also left land and at least two houses after her father’s passing.

Manually Laboring Middle Class:

Income wise these careers are middle class, being able to net £1000/year, but there was a difference between enjoying a good quality of life and being socially accepted. Iif you worked with your hands, no matter how skilled you were, you were still a laborer and seen as lacking in culture.

Tracy: A clockmaker made up to £400/year, which jumped to £840/ year if they also worked on watches as well. Her father, Mark, would have netted them enough money to fall into the working middle class, and this is before Tracy’s mechanical genius became evident. If Tracy’s life had gone differently, it is possible she could have become what was known as a Master Mechanic, a skilled worker who could earn £1000/ year, guaranteeing a high standard of living.

Demi: As a Barmaid alone, Demi would make about £150/ year, which would be difficult to survive on; however, she and her brother own their establishment. Their bar could make about £1000/ year, giving them a comfortable life in terms of amenities, but Barmaids were not respected and often suspected of being easy; many young women in major cities who worked in shops and restaurants took up sex work to supplement their meager incomes.

Leo: At one point appears to have owned two factories, both his initial textile factory and the doomed arms factory.

More or Less Stable Working Class

Emma: A gardener would make, at a maximum, £400/ year, and a young gardener like Emma would certainly not be able to earn that much. In her previous life as Lisa Beck before Leo made a bad investment, she was likely very comfortable, as Leo did own a presumably successful textile factory. She may be especially nostalgic for her childhood with her father because her situation changed drastically very rapidly, going from living in a pleasant environment with two parents, plenty of toys, good food and clothes/household with a steady income, to being placed in a Victorian orphanage and eventually becoming a manual laborer.

Helena: She wishes to attend college, but cannot afford to do so. We aren't exactly sure what her father does for work, but he is likely in the working class, as many middle class families could reasonably afford to educate at least one of their children, and Helena is, to our knowledge, an only child. They seem to have enough money to provide her with certain accommodations, like spectacles and her cane, though these may have been gifts from Sullivan.

Kevin: the lifestyle itself would be rough, but he could make around $480/year (sorry for the currency change, but he lived and worked in the USA, and England did not have cowboys).

Bane: A game keeper often had a relatively low income and would by that definition actually fall into the below category, but housing was almost always provided to men who held this job, taking a stressor off his plate. Steady employment/staying at a position for several years was also common, providing general stability.

Working Class and Extremely Poor:

-Families or households often struggling to scrape by on under or around £300/ year, sometimes with individuals making as little as £25/ year. A frugal family at the top end of this budget would overlap with lower middle class and would be able to employ a maid, putting appearances first and sacrificing other luxuries. There is less money for entertainment, and almost all of the income goes to food and housing. Little or no savings. The vast majority of the population falls in this category because things never change, with only 7.7% of workers making £340 or above, and 42.9% £192 or under.

Norton: Coal miners earned around £260/ year. Norton was looking for gold and gems, but it’s safe to assume his standard of living would have been about the same as a coal minder. Compared to some jobs, this wage may have seemed decent, but mining was brutal and incredibly dangerous. Miners typically lived in housing camps operated by mine owners, and had to buy their daily essentials from in-camp stores and commissaries.

Victor: I had to conjecture a little here, but senior postal service employees were making around £200-300/ year, and newer employees a starting annual wage of £90 so we can guess Victor falls around here as well. We also do not know about his family’s class background.

Andrew: Andrew probably wishes he really was a Train Conductor. In that job, he could have made £900/ year, granting him membership the middle class. Being a Grave Keeper or Grave Digger was an awful job, physically demanding and badly compensated. Cemeteries often stank of rotting bodies, and Grave Diggers had a low social standing because they worked so closely with corpses. I could not find concrete information about how much he would have made, but it would definitely fall below the £300/year mark that is the ceiling for entry into the lower middle class, given that the other Survivors with physical/ unskilled labor jobs seem to peak at the £200ish range.

Worth noting though not necessarily tied to class is the common misconception that Andrew is illiterate, which he certainly isn’t. His dedications include a diary entry he wrote in which he tries to justify to himself his bodysnatching activities, and he also received letters from Percy’s assistant. He might have a little trouble with small print due to his bad eyesight, but he can absolutely read and write. Most people, even the poorer classes, were at least somewhat literate in this period in the United Kingdom.

Outsiders/I Have No Idea

-These are characters with either extremely vague and mysterious pasts or who have extremely unconventional professions.

Patricia: A Voodoo practitioner, it is unclear if she performs the work of a Voodoo priestess, which could be lucrative. Marie Laveau, on whom she is allegedly loosely based, was very financial successful, but to be honest, I think the IDV writers have a very shaky grasp on actual Voodoo practices and beliefs (as do most folks probably who have no idea that a lot of practitioners are also Catholic. It's a syncretic religion so yes, Patricia’s nun costume actually makes some sense.)

Fiona: It is openly stated she comes from an unknown class. There aren’t really historical precedents I could find in my research for occultists of her stripe earning an income, as there’s no indication she goes around giving exhibitions or overseeing seaances. Many Victorians dabbled in the arcane as a hobby, but those who were able to fully devote themselves to their studies tended to come from very comfortable backgrounds, such as Helena Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley.

Kreacher: He is a thief. Nothing else to say.

Eli: Another character with an ambiguous background. We have little information about his family life, but he is considered in his write-up by the organizers of the manor games to be unemployed.

EDIT: @ivy0309 informed me Eli is listed as coming from a middle class background in the official setting book.

Ganji: He is likely extremely poor. I could not find anywhere what a professional athlete might have been paid, but we do at least know he cannot afford travel home to India.

William: He is presumably from a middle class family, given that he attended university. As with Andrew above, I have a seen of lot people claiming William is less intelligent/educated than he is, when he’s actually at least one of the most educated characters in the game. He may have made a poor decision drinking the poisoned wine and come off as a muscle head, but he is far from a himbo. I don’t know what his current social class could be considered, as professional athletes in the Victorian era were not the same was they are now, but William does appear based on his clothes to be a rugby player more or less full time?

Performers/Entertainers

-This is another tricky group to get a handle on, because the role of the entertainer in society meant that one could be exalted and idolized while also not being welcome in polite society. I cannot speak to actual income amounts for these characters, but can provide a few general notes of interest. Also worth noting is that a top-billed musician like Antonio would be treated very differently than the Hullabaloo performers, who were certainly seen as impolite and indecent.

Margaretha/Natalie: Female performers were often characterized as promiscuous and sexually available, and therefore sneered at. Margie is wearing the costume of an exotic dancer (for those who may not be aware, this doesn't meant actually foreign or exotic, it explicitly means a dance intended to arouse or excite). She is not doing well fiscally after Sergei’s death, and is implied by the description of her animal tamer costume to dance/busk for tips.

Her uncle and aunt who raised her lived in Lakeside, and Natalie is described as wearing a cheap cotton dress in a photograph of her living under their care. Her background then would likely fall under manually laboring/working class.

Mike: Mike is one of the circus’ most popular performers, so he makes more than Margaretha, but that's all I can guess.

Joker: He is less popular than Mike and Sergei, but is allowed his own tent because either he has enough status in the Hullabaloo or nobody wants to room with him.

Violetta: Her family abandoned her, and she was seen as an asset by Max. Likely has little to no money of her own.

Servais: He at least considers himself middle class and respectable, and his dress does suggest he is financially solvent.

Antonio: A musician welcomed at court who played for upper-class audiences. Antonio was raised to be a money-maker by a stern father and did receive royal patronage, but based on his personality traits I am willing to bet he has poor money management skills. His real-life inspiration, Niccolo Paganini, died in debt.

Murro: Treated as a possession by Bernard and then living on the run, it's hard to imagine he had any way of earning money after fleeing the circus, nor the necessary knowledge to exist within society.

Willis Brothers: I believe their situation would be similar to Violetta’s. Disabled sideshow performers could occasionally have quite lucrative careers, but this was rare.

This is far from comprehensive, but thank you so much for taking the time to read this far! If you have any questions or wish to discuss anything here, please feel free to talk to me!

A great resource for approximating the income ranges used above is this database, this is invaluable for looking at things like average wages, housing costs, price of goods in different countries (mostly the US, UK, and Western Europe) across decades and eras.

#identity v#idv#idv lore#idv speculation#William Ellis#Fiona Gilman#Edgar Valden#Melly Plinius#Norton Campbell#Servais LeRoy#Patricia Dorval#Annie Lester#Aesop Carl#Victor Grantz#Ganji Gupta#Eli Clark#Kreacher Pierson#Alva Lorenz#Luca Balsa#Emma Woods#Emily Dyer#Joseph Desaulnier#Vera Nair#Galatea Claude#Alice DeRoss#IDV Keigan#IDV Jack#Freddy Riley#Jose Baden#IDV Orpheus

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Keith Woods

Published: Jul 2, 2023

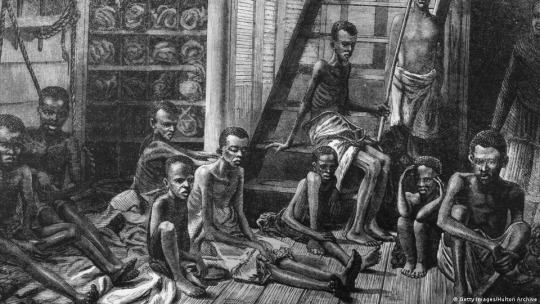

A look at slavery outside of the West

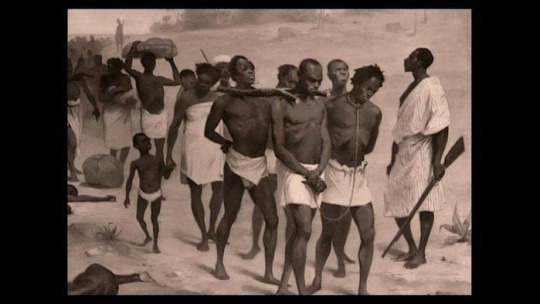

It has become popular to blame White people for slavery, to the point that many actually believe slavery was invented by or exclusively practiced by Europeans.

But the history of slavery outside the West is far more brutal.

The Arab slave trade emerged in the 7th century, 10 centuries before the Atlantic slave trade

Arabs sold Africans to the Middle East for a variety of jobs such as domestic work or harem guards - castrating male slaves was common, causing over half of males to bleed to death

The Arab slave trade was particularly brutal: it's estimated that 3/4 captured slaves died before they reached the market for sale

Historians estimate that between 10 and 18 million people were enslaved by Arab slave traders, including women and children taken as concubines.

Arabs did not create the slave trade out of nothing, in fact, enslaving conquered tribes was already common practice in Central Africa when they arrived.

The West African Songhai Empire relied heavily on captured slaves in all levels of society, even as soldiers.

Africans themselves also played a large role in facilitating the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

African tribes conducted raids on rival groups to provide slaves for sale. African middlemen facilitated trade between European traders and African suppliers.

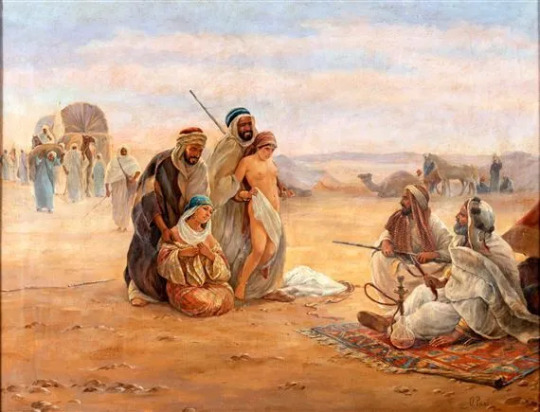

The Arabs also had a slave trade in Europe. Estimates are that up to 1.25 million Europeans were enslaved by Barbary pirates, who would raid villages in coastal countries like Italy, France, England and Ireland, bringing them to North Africa for sale.

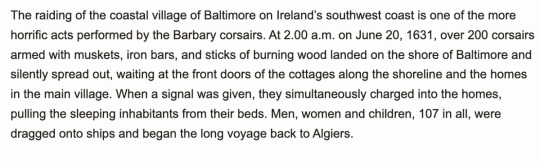

In some cases entire villages would be captured, such as the Irish coastal village of Baltimore, entirely raided in 1631.

These slaves faced a brutal future, engaging in hard labour or sexual servitude, and spending nights hot and overcrowded prisons called bagnios.

Many slaves captured by Barbary pirates were sold eastwards into the Ottoman Empire. Slavery was central to the Ottoman Empire, most towns had dedicated slavery markets called Yesirs.

Slaves came from Africa, the Caucasus, the Balkans and Eastern & Southern Europe.