#Presbyterian Church in America

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I just want to say, as a member of the PCA, Revoice is an utter ugly stain on my denomination and everyone involved in its inception should’ve been put under discipline a long time ago, and the leaders expelled from ministry. they are wolves in sheep’s clothing. “Spiritual Friendships” are a trap set by Satan.

#Christianity#Presbyterian Church in America#mobile#sexuality#x#I have been listening to Shepherds for Sale by Megan Basham and she is really good at putting things in perspective#and in such measured journalistic timbre#it’s made me realize how numb I’ve become to things like Side B and people like Tim Keller#and my mom is right when she says God took Tim Keller’s life in a timely manner#his decline in discernment was disastrous for the PCA#the bulk of SfS regards the Southern Baptist Convention (lots veeeery inchresting stuff I didn’t know)#but she certainly has a lot to say about Keller and has dedicated a whole chapter to Side B-ism (AS SHE SHOULD)#every elder/pastor should read this book#we decry how bombastic Martin Luther was in his language against the clergy but we could use him in our own denominations right now.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am a deacon in the PCA. What happened with Scott Sauls solidified a position I already held, that I will never vote in favor of the pastoral salary of any graduate from Covenant Theological Seminary, and that the entire leadership of both the seminary and the Nashville Presbytery should be placed under discipline.

In the aftermath of the American Civil War, there were two major bodies of Presbyterians in the US. For clarity's sake, they will be referred to as the Northern and Southern Presbyterian Churches. In the early 20th century, the Northern Presbyterian Church started slipping doctrinally and its more Biblical orthodox ministers left under the leadership of JG Machen to found the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) in 1936. This nascent denomination had its own problems, with two major factions represented. The ones that were chasing trends in American evangelicalism at the time (being teetotalist and dispensationalist) left to found the Bible Presbyterian Church (BPC) the next year. 19 years later, the BPC established Covenant Theological Seminary.

Wherever evangelical trend-chasers in northern Presbyterianism went, they somehow kept taking CTS with them, and in the late 1970s it was in the hands of the Reformed Presbyterian Church, Evangelical Synod (RPCES). In the meantime, the doctrinal issues that motivated the formation of the OPC made their way south, leading the more Biblically-oriented pastors of the Southern Presbyterian Church to found the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) in 1973. This denomination spent the first several years of its existence lacking a seminary and taking various measures to establish a presence in the northern US and in Canada. This led to entering merger talks with the OPC, the RPCES and another denomination called the Reformed Presbyterian Church in North America (RPCNA), all of which had a northern and Canadian presence, and had seminaries. The PCA retracted its invitation to the OPC because it was embroiled at the time with a controversy over the doctrine of justification (see p. 97), and the RPCNA declined the invitation (see pp. 100-101), leaving only the RPCES, which was successfully absorbed into the PCA in 1982, bringing CTS with it.

The next year, a number of churches left the PCA to form the Reformed Presbyterian Church in the US (RPCUS), citing the denomination's unfriendly attitudes to postmillennial eschatology. The merger was doubtless a contributing factor, as the BPC was founded to promote premillennialism, still promoted it when establishing CTS, and there was a substantial share of premillennialists in the RPCES at the time of merger, including, most notably, Francis Schaeffer.

The merger, and the ensuing departure of postmillennialists, combined with the substantial number of former Southern Baptists in the PCA's existing membership, helped propel, for good or for ill, the PCA towards the mainstream of American evangelicalism, particularly in comparison with other Presbyterian bodies. This is why many PCA congregations have contemporary worship, Passover seders. seeker-sensitive models, are friendlier to dispensationalism and, in recent years, have become more tolerant of sexual antinomianism.

In the early 2000s, a controversy erupted over the doctrine of federal vision in the PCA. Many ministers who promoted it left or were expelled. Notably, federal visionists tend to hold to postmillennialism and hold more strictly to the regulative principle of worship, and their absence from the PCA propelled it even further towards the evangelical mainstream.

Recently, a conference taking place on PCA church grounds, using church funds, called Revoice has promoted unbiblical views of human sexuality. Steve Warhurst criticized the conference, and 181 ministers of the PCA came out of the woodwork to condemn him, including 80 graduates of CTS. In addition, another CTS graduate, Greg Johnson, used his office to further promote unbiblical views (but thankfully left the denomination). More recently, one of the men on the list, Scott Sauls, was known to have promoted a hostile work environment and promoted unbiblical views of church offices (but also thankfully left the denomination).

This leaves the denomination as effectively two in one trenchcoat, classical Presbyterians, and effectively Baptists who happen to sprinkle babies. This year's general assembly will see a number of overtures assessed that will bring the denomination either closer or further away from Big Eva. It has yet to be seen whether the departure of men like Johnson and Sauls will be enough to stem the tide towards trend chasing.

If the OPC had simply not had this controversy in the early 1980s, we wouldn't be in this mess. Thanks for nothing, Norman Shepherd!

#Presbyterian Church in America#Scott Sauls#PCA#Covenant Theological Seminary#Nashville Presbytery#evangelicalism#evanjelly#evanjellies#evanjellyfish#big eva#opc#rpcna#Greg Johnson#Norman Shepherd

0 notes

Text

Love in the Prairie State

#love in the prairie state#my photos#photography#small town#small town photography#church#prairie state#midwest#illinois#churches#rural#rural america#rural photography#countryside#country#carpenter gothic churches#carpenter gothic church#carpenter gothic#feat. the love of my life:#shiloh cumberland presbyterian church#tradition to take its picture every time i pass it

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

BREAKING NEWS: Bob Jones University employees were instructed that they have until the beginning of the 2024-25 school year to leave churches in the Presbyterian Church of America denomination and the Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians.

Information is pouring in. Faculty are mad. Many, many faculty have found solace in churches that are outside BJU's maw. Churches that are not pastored by BJU graduates and churches that preach the Good News.

First Presbyterian, for instance, is part of the ECO and has a boatload of BJU graduates on staff. But you see, that denomination ordains women, so it's outside BJU's standard.

But the PCA is the more conservative of those two. I attend a PCA church, btw. I see BJU employees attending there all the time. They are in the choir and our orchestra. I'm glad they are hearing the Good News like I am.

Even Steve Pettit attended a PCA church when he was here. He attended Second Presbyterian.

And good ol' Sam Horn was consorting with the PCAers too.

But no more. No more non-BJU-approved churches.

The Black List is back, folks.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Criticizes Cuban Religious Freedom

On June 27, 2024, the U.S. State Department released its lengthy 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom. Surprisingly it did not contain an overall summary of this freedom in the world for 2023. [1] Instead it opened with a short Overview and Acknowledgements followed by the texts of the following sources of the law on international religious freedom: Appendix A: Universal Declaration…

View On WordPress

#Cuba#Matanzas (Cuba) Presbyterian Church (Matanzas Cuba)#Pope Francis#religious freedom#State Department#United States of America (U.S.A.)#Westminster Presbyterian Church (Minneapolis)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The American Mind in 1776 Pt 5/6 - Joe Morecraft Lecture on American History

The American Mind in 1776 Pt 5/6 – Joe Morecraft Lecture on American History Joe Morecraft is a preacher of the gospel (https://heritagepresbyterianchurch.com/) and a noted lecturer on contemporary political and historical trends in the United States. Joe was born in 1944 and is a native of Madison, West Virginia. Joe Morecraft earned a Bachelor degree in history from King College in Bristol,…

View On WordPress

#Christian#christian lecture#CHRISTIAN LECTURES#Christianity#christianity in america#God#Jesus Christ#pastor#preacher#Presbyterian#presbyterian authors#presbyterian church#presbyterian church Georgia#presbyterian pastors#Presbyterians#reformed presbyterians

0 notes

Text

youtube

CBC video: Stolen Children | Residential School Survivors Speak Out

Since their first arrival in the “new world” of North America, a number of religious entities began the project of converting Indigenous Peoples to Christianity. This undertaking grew in structure and purpose, especially between 1831 and 1969, when the governing officials of early Canada joined with Roman Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, United, and Presbyterian churches to create and operate the residential school system. The last federally-run residential school, Gordon Indian residential School in Saskatchewan, closed in 1996. One common objective defined this period: the aggressive assimilation of Aboriginal peoples.

[ legacy of hope ]

#chromatic voice#national day for truth and reconciliation#first nations#turtle island#residential schools#every child matters#missing and murdered indigenous women#mmiwg2s#state violence#canadian content#settler terrorism#christianity as colonialism#orange shirt day

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Catholics and Orthodox have got to knock it off with "Protestants have brutalist corporate churches". A particular modern strain of Protestantism has hideous modern churches. It's a depressingly common strain, and arguably the dominant one in America, but it's either ignorant or dishonest to pretend as though all Protestants have ugly churches.

Behold:

Clockwise from top left:

St. Peter's Church, Geneva, canton of Geneva, Switzerland (Swiss Reformed)

Barnes Methodist Church, London, England, UK (Methodist)

Dutch Reformed Church, Newbury, New York state, USA (Dutch Reformed)

St. Jude's Church, Glasgow, Scotland, UK (Presbyterian)

#i'm not arguing for protestantism#i am arguing for honesty and accuracy in apologetics#christianity#theology#churches#protestantism#swiss reformed#methodism#dutch reformed#presbyterian

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Growing up in Lancaster, Ohio, I remember discovering a book in the local library that ultimately helped to change how I viewed my hometown’s history. The book, “Jewish Literacy” by Joseph Telushkin, had a small sticker on the inside cover indicating it was purchased through the B’nai Israel Synagogue of Lancaster Jewish Book Fund. This was surprising, as there hadn’t been an organized Jewish community in Lancaster for years.

I later learned that the fund had been established by the remaining members of the synagogue after its sale in 1993, with the intention of ensuring that the tradition of Jewish education continued in Lancaster, even in the absence of a physical synagogue.

This discovery, along with other signs like a Star of David engraved next to a cross on the town’s war memorial and the presence of the building that once housed the B’nai Israel synagogue downtown, hinted at Lancaster’s former Jewish community. During its nearly seven decades of existence, B’nai Israel not only served its congregants but also hosted groups — including church youth organizations and civic societies — to educate others about Judaism. As in many small towns across the United States, the synagogue provided the only accessible resources for learning about Jewish culture, history and theology.

For the last several years, I’ve dedicated myself to documenting the Jewish histories of small towns in both my home state of Ohio and my adopted state of New York. I am drawn in by the realization that many of these once-active communities, despite their contributions, were in danger of fading into obscurity. As a volunteer, I have spent countless hours piecing together the stories of Jewish families, tracing their lives and legacies in over 20 small towns. In most of these places, the written record of their Jewish past was sparse, with local historical organizations often lacking the resources or staffing to fully explore these stories. These constraints also create opportunities for volunteers and community members to engage in uncovering stories still waiting to be told.

Small-town synagogues often function not just as religious institutions but as unique centers for education and community engagement. In Lancaster, the B’nai Israel synagogue opened its doors to various groups seeking to learn about Judaism. Its book fund ensured that, even after the synagogue’s closure, locals could continue to conveniently access resources devoted to Jewish culture and history.

Eighty miles to the south, in Portsmouth, Ohio, the Jewish community was also engaged in interfaith efforts from its earliest days. When Beneh Abraham, the local synagogue, was consecrated in 1858, Christian residents of the town supported the construction, and the First Presbyterian Church choir even sang during the dedication. Such partnerships went both ways, with Jews contributing to the building funds for nearby churches.

The local rabbi, Judah Wechsler, taught in both English and German. Wechsler’s leadership helped Beneh Abraham function as more than a religious space — it became a center for community engagement in Portsmouth. Portsmouth’s first synagogue, like many other historic religious structures in America, no longer stands today, but this early story from the town’s Jewish community reminds us of how intertwined religious groups in small towns can be. Beneh Abraham continues to exist in Portsmouth and is one of Ohio’s oldest Jewish congregations.

In Auburn, New York, the former B’nai Israel Synagogue played a crucial role in bringing neighbors together and fostering understanding. Throughout much of the 20th and early 21st centuries, B’nai Israel welcomed interfaith activities, particularly through its long-standing relationship with St. Luke’s United Church of Christ. This engagement included an annual exchange of pulpits, novel when it began in 1939, where the rabbi of B’nai Israel and the minister at St. Luke’s would preach at each other’s congregations. This effort, undertaken each year during the national Brotherhood Week campaign, continued for over 30 years, helping strengthen ties between Jewish and Christian communities in Auburn.

In both Auburn, New York, and Lancaster, Ohio, the B’nai Israel synagogues’ efforts to educate non-Jewish neighbors about Judaism often left lasting impressions, in keeping with studies showing that the more people know about Jews, the less they embrace antisemitic tropes. With the closure of these small-town synagogues in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the physical presence of Jewish life in these towns has largely disappeared, raising questions about how this loss impacts interfaith understanding and broader cultural awareness.

As small-town Jewish communities across America continue to contract, preserving their histories becomes not just an act of remembrance, but also an essential part of understanding the broader American story. Though often small in numbers, small-town Jewish communities have played crucial roles in shaping the civic, cultural and economic landscapes of their communities.

As the physical reminders of small-town Jewish life — such as synagogues, social centers and long standing family-owned businesses — fade, there is a danger that their stories will disappear, a loss not only for Jewish history but American history. They remind us that America’s heartland is not as monolithic as it is often portrayed, and that diversity has long been part of the stories of many communities.

In Lancaster and Auburn, the efforts of individuals and institutions to preserve local Jewish histories stand as models of how this work can be done. In its last years, members of Auburn’s former B’nai Israel synagogue donated many of the congregation’s religious artifacts, including the synagogue’s historic stained-glass windows, to the Cayuga Museum of History & Art, ensuring that the congregation’s memory would live on in a public space.

But in most of the communities I’ve studied, there was no such effort until recently. In some towns, synagogues were demolished or fell into disrepair, their histories largely unrecorded. It wasn’t until I began this work as an undergraduate that the stories of these Jewish communities began to be gathered and pieced together, bringing their legacies back into the light.

Preservation alone is not enough. These histories must be shared and integrated into broader conversations about American identity. We not only honor Jewish families who helped to build and sustain so many small-town communities but also ensure that future generations understand the complexity and richness of small-town life in America.

In a time when debates about national identity dominate our public discourse, preserving the histories of small-town Jewish communities offers a crucial reminder: that the American story is, and always has been, one of diversity and change.

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for your blog! It’s exactly what I need right now.

I’m currently trying to construct my beliefs after a lifetime raised in the PCA (Presbyterian Church of America). It’s such a mindfuck because I can see how hateful a lot of PCA beliefs are and how when their theology is applied consistently it inevitably leads to abuse. It seems like the only ppl not fostering abuse in the system have twisted the words of the Bible to mean the opposite (ex: “this verse sounds like it’s saying x but if you go to the Greek blah blah it’s actually saying y.” Or “yes that verse does say that but obviously they’re applying it wrong. It was never meant to be taken that far” etc)

But even seeing all of this my coping mechanisms under stress are all still based in God. He was supposed to be the one constant thing and i don’t know what to do with that gone.

I feel like my beliefs are currently so fucked up. Trying to write down everything I feel is true and it’s ludicrously contradictory:

- there is no God

- Jesus is God

- after we did nothing happens. It’s the same as the space before we were born

- God has a plan to redeem suffering. All the pain in the world can’t be for nothing. People who live their whole lives in extreme duress and then die must get a chance after death to live prosperous lives. I don’t need eternal life but I need to know others will have it.

- hell is ridiculous and not real. I don’t want ppl to suffer like that no matter what they’ve done so a perfect God can’t be more petty than me. All I truly want from ppl who abused me is for them to never speak to me again. The only “punishment” I might want for them is for them to realize the damage they did and that I only want so they don’t do it again to others. I’m not talking to them so I don’t care.

I’m sure there are more but that’s all I can think of right now. It’s so confusing and messy! Does it ever settle a bit? Will I ever have a set of consistent beliefs again?

The short answer is yes and yes. Things also felt messy for me at first, but I did eventually reach a point of stability.

Congrats on being open to investigating and improving your worldview! That's such a cool and kind thing to do for yourself that many people never manage. I'm sure there's a lot to unpack, so I want to encourage you to treat yourself well while you're challenging your beliefs. Take breaks, seek support, and be patient.

Early in my deconstruction, I craved certainty because I believed that that's what truth felt like. I thought I would investigate my beliefs until I had a new and better set of beliefs on the other side of the process. But along the way I figured out that stability and consistency don't need to come from having an unchanging set of beliefs.

What I found was that having a good set of tools for seeking, analyzing, and integrating information into my life was more stable than having a static set of beliefs.

My beliefs used to be precious and protected, like trophies in a glass case, high up and out of reach. When I started deconstructing, that case came crashing down.

I felt ashamed that Christianity wasn't the only tool I needed to build a stable set of beliefs. For so many people around me, that seemed to be all they needed.

I began to question why I thought Christianity was true: love, belonging, fear, authority, loyalty, and stability were the main ones. But my beliefs didn't account for empathy, ethics, or epistemology and many other things. Heck, I didn't even know the word epistemology when I started this journey. I didn't know how to seek knowledge without running it through a Christian filter first.

I'd been told that CHRISTIANITY = TRUTH, so I hadn't considered that there were other methods to seeking, analyzing, and integrating new knowledge into my life.

But then I started exploring logic, philosophy, psychology, history, biology, and other subjects I'd been afraid would challenge my Christian beliefs. I started reading about other religions and comparing them to Christianity. And, most importantly, I started going to trauma-informed therapy. All of those things helped me break out of old patterns, learn how to update my beliefs based on new information, and how not to be afraid of that whole process.

Focusing on the tools I used to build my beliefs instead of the beliefs themselves, I was able to put together my own toolbox that helped me establish a more stable system of belief. I still go by my belief-shelf every once in a while, dust things off, admire beliefs that stood up to testing, and reevaluate beliefs that didn't. But that last part got rarer and rarer and no longer feels like the end of the world. Because ultimately, I'm still working with the same toolbox.

I used think that Christianity was a universal set of tools that worked for anyone in any situation, but now I see it as one very old tool that doesn't work for everybody. And, despite what I'd been told again and again as a Christian, the Bible is not a truth-seeking tool. It's a set of stories that can tell us about what the authors thought about themselves and the world. And, don't get me wrong, I love storytelling. I think it's very important. We can learn a lot about other people, their perspectives, and their philosophies. The problem comes in when people take their specific interpretation of stories in Christianity and try to apply them universally.

But we don't have to rely on the same old tools forever. We can try out new tools and figure out what will help us build the life that we want to have. Equipped with a variety of tools instead of one dusty one, we are more prepared to live and thrive in this constantly changing world.

Looking back, I'm glad my shaky shelf of beliefs fell apart. Because it gave me the opportunity to take responsibility for my beliefs instead of just protecting them.

I want to touch on one more point that you raised before I close, and that is the unbearable weight of suffering in the world. I struggled with this a lot during my deconstruction. It's a tough thing, to come from a worldview that has simple answers and adjust to the reality that reducing suffering is much harder than "let go and let God." My advice is to seek out good news, because it won't show up in social media feeds as much as bad news does. Find the people who are helping others, solving problems, and actively building community. Also, try to find some small way to do good, lessen suffering, or prevent harm if you have the ability and resources to do so.

That's part of why I run this blog, to try to help other people let go of harmful Christian beliefs with more joy and less suffering.

Thank you for sending me this ask. Messages like these inspire me. I see the effort and empathy behind your words and it gives me more hope than I had before!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Jones II and Jennifer Vilcarino at ABC News:

"Think about that -- that nothing is off limits, that raids could go and happen in our public schools," New York Rep. Nydia Velazquez said. "You know, that is the point: cruelty. You got to be heartless to say publicly that we are going to send ICE to our schools -- heartless." In its first press conference of the 119th Congress, the Congressional Hispanic Caucus condemned President Donald Trump's immigration executive orders and the Department of Homeland Security revoking long-standing restrictions that thwarted Immigration and Customs Enforcement from conducting raids on schools and other sensitive areas. "[Trump] says he's targeting criminals, but he just removed the restrictions that stopped ICE from conducting raids on schools, on hospitals and in churches," Texas Rep. Joaquin Castro said at the more-than-hourlong presser. "I would ask you who he believes among those kids is a criminal sitting in a first grade class. Who are the criminals that he's going after in the Catholic Church, in the Presbyterian Church, in the nondenominational churches? Who are those criminals?" Acting Homeland Security Secretary Benjamine Huffman said that to curb the "invasion" at the border, the policy is needed to "return the humanitarian parole program to its original purpose of looking at migrants on a case-by-case basis." "This action empowers the brave men and women in CBP and ICE to enforce our immigration laws and catch criminal aliens -- including murders and rapists -- who have illegally come into our country. Criminals will no longer be able to hide in America's schools and churches to avoid arrest," Huffman wrote in a statement on Tuesday.

Having ICE raid schools is a moral disgrace, as the fear of raids traumatizes immigrant students, teachers, and staff.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the 50th anniversary of the Presbyterian Church in America. 🎉

Fun fact: the PCA congregation I attend was planted by Westminster Presbyterian Church, within whose sanctuary the PCA’s charter was signed.

0 notes

Text

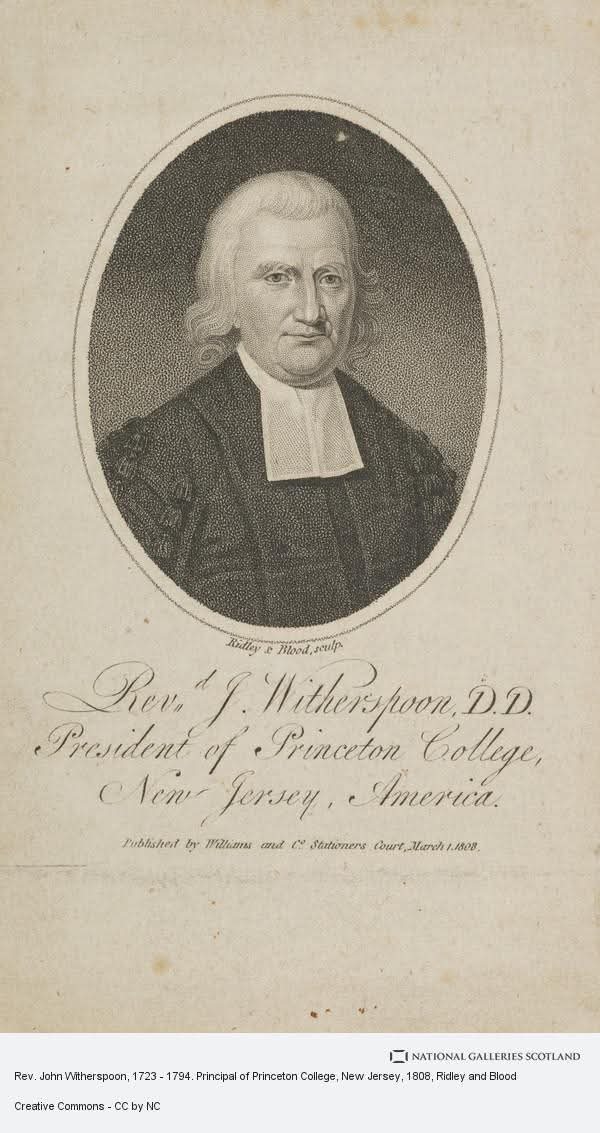

On February 5th 1723 John Witherspoon, clergyman, writer, President of Princeton University, signatory to American Declaration of Independence was born.

Witherspoon was educated at Edinburgh University and was ordained as a minister in 1745. One of his ancestors was John Knox who had been a major force in the Reformation of the church in the middle of the 16th century.

Witherspoon’s first charge was as minister of the Auld Kirk in Beith in Ayrshire where he preached for twelve years. He was regarded as a brilliant orator and was “head hunted” by a number of churches in Scotland (and abroad) before moving to Paisley.

While he was at Paisley, Witherspoon met 21-year-old Benjamin Rush who was born in America of Scottish parents, and attended the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University), Rush had then enrolled at the University of Edinburgh’s medical school. Armed with letters from Benjamin Franklin, Rush convinced the 42 year old Witherspoon to leave Scotland and become president of the College of New Jersey in 1768 and a delegate to the 2nd Continental Congress.

Witherspoon was soon supporting the independence fight in America because he believed that his native land had “gone soft on religion”. Of course, the Presbyterian church’s principles of egalitarianism and the natural antipathy of the Scots to the English rulers were factors too.

Witherspoon became what in today’s politics would be regarded as a senator. And in the first draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he demanded the deletion of a phrase that complained that the king of Britain had sent to America “not only soldiers of our common blood, but Scotch and foreign mercenaries.”

However, when some of the representatives from the thirteen American colonies gathered to decide whether to break completely with Britain, some of the delegates realised the difficulty of taking on the might of the British Empire.

It was Witherspoon who urged them to sign the Declaration of Independence, saying “There is a tide in the affairs of men, a nick of time. We perceive it now before us. To hesitate is to consent to our own slavery.”

It is worth noting also that of the 56 men who signed the document, 21 had some Scottish ancestry. Witherspoon was the only clergyman to sign this historic document, which has been compared to the Declaration of Arbroath which proclaimed Scottish freedom for the first time, although many historians dismiss this nowadays.

Witherspoon also became a member of the congress which conducted the war and later helped to draft the peace agreement which brought the war to an end.

After leaving Congress in 1782, Witherspoon was involved in the rebuilding of Princeton College (destroyed during the war). He was its President from 1768 until his death in 1794. More than any other university, Princeton in those days had students from all over the United States, not just from its home state and so Witherspoon’s influence on the country was that much more significant.

As with most white gentry of the era Witherspoon was involved in the slave trade.

Beginning in 1779, he acquired two enslaved laborers for his country estate. About eight years later, both mysteriously disappeared. New research suggests that at least one may have been freed and settled on his own land. Their demise, sale or escape are other, less cheery, possibilities.

Another two enslaved individuals were listed among Witherspoon’s possessions in an inventory dated November 1794, alongside six cows, 10 horses, 12 pigs and 24 sheep. He also recruited the sons of wealthy Southern planters to finance Princeton through donations and tuition.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music of TURN

Round 17

(I didn't have time to finish round 18 because it's homecoming week and I'm in marching band so only one a day from now on)

Hush

Well I've gone into song histories, why not go into thematics and other observations. One thing I've noticed is that the soundtrack of TURN leans heavily on strings. One would expect that in a score, but it's mostly solo strings instead of an orchestral group.

Now I have no idea if this was intentional, but with strings, piano (technically harpsichord), and voice being the most prevalent melodic instruments in colonial America, it would be fitting to have these instruments dominate the soundtrack. Again, I don't have any experience in this field of music, it might have just have been the easiest instrument to get in the show. But a lack of woodwinds and brass in the featured songs makes me wonder. (For anyone wondering, the reason for a lack of the other instruments is that they would only really be used in orchestras, not soloistically. No court composition in America along with a lack of talent because if you played those instruments, you likely didn't have much reason to go across the Atlantic.)

youtube

A Lyke Wake Dirge

1.10: The Battle of Setauket

So now that we know the history (if you need a refresher. Lyke = corpse, Wake = the time between death and funeral/burial, Dirge = lament/funeral song. And the lyrics tell of a souls journey to purgatory) let's look at how it fits.

It represents the death of not only Mr. Baker, but Abe being his killer. Early season one has Abe swearing to never take a life. This is the death of that part of his character. As we see him more and more willing to kill. First understandably with Simcoe, and to Wakefield (I believe) and finally his worst moment when plotting to kill Hewlett.

The fire of the house plays into the image of purgatory. Most of what we associate with purgatory (including the song) comes from Catholic doctrine. Where a soul goes under temporary punishment to purify/purge the soul of sin before entering heaven. Fire is associated for a multitude of reasons (from pagan, to analogies, to scripture) and I am not a religious studies major so I won't go too in depth.

But in this instance I would see the burning house as almost the opposite. From the ashes of the house comes the root cellar, his base for spywork. Again, I have no clue if I am looking far too into it, but I see the connections.

Complete side note that doesn't add much, I just typed it out hoping it would fit and then realized it didn't. From the show, I'm going to guess that they are Presbyterian. As Ben's father (historically) was Presbyterian and it is known in the show that the Woodhull's attended Reverend Tallmadge's church. I don't know much on 18th century Presbyterianism, but I would imagine that the views on purgatory haven't changed. In that it is not a necessary step. But they would certainly be aware of the concept.

youtube

#turn music bracket#turn: washington's spies#turn amc#turn washingtons spies#culper spy ring#anna strong#mary woodhull#abraham woodhull#18th century music#music history#turn music#Youtube

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.S. Churches and Religious Groups Demand Ending of U.S. Designation of Cuba as a State Sponsor of Terrorism

In a May 9, 2024, letter to the U.S. Department of State 20 U.S. churches and religious groups called for the U.S. to end its designation of Cuba as a state sponsor of terrorism.[1] This letter made the following points: “We write to express our deep concern regarding the plight of the Cuban people. The combined effects of failed U.S. foreign policies and Cuban economic policies have created…

View On WordPress

#"State Sponsor of Terrorism"#Cuba#United States of America (USA)#Westminstere Presbyterian Church (Minneapolis)

0 notes

Text

Post-election day 2!

This is Oregon specific, but maybe there's something like this where you live?

The Rural Organizing Project is having a post-election strategizing meeting (online)! You can register here:

Are you located in rural Oregon? Do you have loved ones in rural Oregon? the ROP supports human dignity groups in rural areas around the state, here's the list - maybe good places to get involved!

BAKER

Baker Radio: KBZR

Baker Community Justice Project

BENTON

Coast Range Association

Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism

Corvallis Daytime Drop-in Center Street Outreach Response Team

Corvallis Latin America Solidarity Committee

Linn-Benton Greens

Linn Benton NAACP

Linn Benton Rapid Response Team

Mid-Valley Health Care Advocates

Mid-Valley Solidarity Coalition

Race Matters, First Congregational UCC

Stop the Sweeps

Sunrise Corvallis

Veterans For Peace, Linus Pauling Chapter 132

CLACKAMAS

Bridging Cultures

Clackamas DSA

Indivisible Clackamas

CLATSOP

Columbia Pacific Alliance for Social Justice

Indivisible North Coast Oregon

COLUMBIA

Columbia County Coalition for Human Dignity

Vernonia Equality & Racial Justice

COOS

Human Rights Advocates of Coos County

South Coast Equity Coalition

Southern Oregon Coast Pride

CROOK

Human Dignity Advocates of Crook County

Latino Community Association

PFLAG Prineville

CURRY

Indivisible North Curry County

South Coast Equity Coalition

Southern Oregon Coast Pride

DESCHUTES

Bend Equity Project

Indivisible Sisters

Latino Community Association

Peace and Social Justice Team of First Presbyterian Church

PFLAG Central Oregon

Redmond Collective Action

Vocal Seniority

DOUGLAS

Support for Asylum-Seekers and Immigrants

GILLIAM

NORCOR Community Resource Coalition

Rural Voices

GRANT

Grant County Positive Action

HARNEY

Rural Alliance for Diversity

HOOD RIVER

Columbia Gorge Women’s Action Network

Gorge Ecumenical Ministries/Somos Uno

Hood River County Rapid Response Team

Hood River Latino Network

NORCOR Community Resource Coalition

JACKSON

Ashland Together

Peace House

Southern Oregon Jobs with Justice

Truth to Power

JEFFERSON

Jefferson Positive Action Group

Latino Community Association

JOSEPHINE

Unitarian Universalists of Grants Pass Social Action Team

KLAMATH

Klamath Peace Readers

LAKE

Indivisible Lake County

Outback Voices

LANE

Blackberry Pie Society

Church Women United

Community Alliance of Lane County

Deadwood Resists

Florence Indivisible

Florence ORganizes

Springfield-Eugene Showing Up For Racial Justice

Support for Asylum-Seekers and Immigrants

LINCOLN

Acompañar

Coastal Network

PFLAG of the Oregon Central Coast

LINN

Albany Peace Seekers

Linn-Benton Greens

Linn-Benton NAACP

Linn Benton Rapid Response Team

Mid-Valley Solidarity Coalition

MALHEUR

Four Rivers Welcome Center

MARION

Silverton Progressives

MORROW

Oregon Rural Action

Rural Voices

POLK

Polk Folks for Human Dignity

Unidos Club at WOU

SHERMAN

Rural Voices

TILLAMOOK

Tillamook Democracy Project

UMATILLA

Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Youth Leadership Council

Oregon Rural Action

Pendleton Community Action Coalition

UNION

Oregon Rural Action

Union County Progressives

WALLOWA

Postcardia

WASCO

NORCOR Community Resource Coalition

Protect Oregon’s Progress / The Dalles Indivisible

Wasco County Rapid Response Team

WASHINGTON

Adelante Mujeres

Western WashCo For Racial Justice

WHEELER

Rural Voices

YAMHILL

Progressive Yamhill

Unidos Bridging Community

#oregon activism#oregon#pdx#portland oregon#portland#portland activism#i cannot personally vouch for any org i'll highight in this series#if you know anything i don't please tell me#if you go to a group and have a bad experience please tell me

14 notes

·

View notes