#Pompeii Records

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Hadsel / Beirut (Pompeii Records, 2023)

Hadsel est le premier nouvel album de Beirut depuis la sortie de Gallipoli en 2019 et le premier sur Pompeii Records, le propre label de Zach Condon. Enregistré sur l’île norvégienne de Hadsel peu après qu’une crise physique et mentale l’ait contraint à annuler sa tournée de 2019, Zach cherchait un endroit pour se rétablir après avoir été laissé dans un état de choc et de doute.

Travaillant dans l’isolement, Zach était perdu dans une transe, trébuchant aveuglément sur un effondrement mental mis de côté depuis son adolescence. C’est arrivé brusquement et ça l’a sonné. Il s’est retrouvé confronté à beaucoup de choses passées et présentes tandis que la beauté de la nature, les aurores boréales et les terribles tempêtes jouaient un spectacle impressionnant autour de lui. Les quelques heures de lumière révélaient la beauté insondable des montagnes et des fjords alors que les longs crépuscules le remplissaient d’une excitation méditative. Zach aime penser que ces paysages sont en quelque sorte présents dans la musique. La collection de chansons qui en résulte reflète magnifiquement cette vulnérabilité, ce sens de l’autodétermination et la conviction qu’après l’effondrement, on peut réapprendre à se débrouiller seul.

Hadsel

Arctic Forest

Baion

So Many Plans

Melbu

Stokmarknes

Island Life

Spillhaugen

January 18th

Süddeutsches Ton-Bild

The Tern

Regulatory

0 notes

Text

More than 200 Survivors of Mount Vesuvius Eruption Discovered in Ancient Roman Records

After Mount Vesuvius erupted, survivors from the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum fled, starting new lives elsewhere.

On Aug. 24, in A.D. 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted, shooting over 3 cubic miles of debris up to 20 miles (32.1 kilometers) in the air. As the ash and rock fell to Earth, it buried the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

According to most modern accounts, the story pretty much ends there: Both cities were wiped out, their people frozen in time.

It only picks up with the rediscovery of the cities and the excavations that started in earnest in the 1740s.

But recent research has shifted the narrative. The story of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius is no longer one about annihilation; it also includes the stories of those who survived the eruption and went on to rebuild their lives.

The search for survivors and their stories has dominated the past decade of my archaeological fieldwork, as I’ve tried to figure out who might have escaped the eruption. Some of my findings are featured in an episode of the new PBS documentary, “Pompeii: The New Dig.”

Making it out alive:

Pompeii and Herculaneum were two wealthy cities on the coast of Italy just south of Naples. Pompeii was a community of about 30,000 people that hosted thriving industry and active political and financial networks. Herculaneum, with a population of about 5,000, had an active fishing fleet and a number of marble workshops. Both economies supported the villas of wealthy Romans in the surrounding countryside.

In popular culture, the eruption is usually depicted as an apocalyptic event with no survivors: In episodes of the TV series “Doctor Who” and “Loki,” everyone in Pompeii and Herculaneum dies.

But the evidence that people could have escaped was always there.

The eruption itself continued for over 18 hours. The human remains found in each city account for only a fraction of their populations, and many objects you might have expected to have remained and be preserved in ash are missing: Carts and horses are gone from stables, ships missing from docks, and strongboxes cleaned out of money and jewelry.

All of this suggests that many – if not most – of the people in the cities could have escaped if they fled early enough.

Some archaeologists have always assumed that some people escaped. But searching for them has never been a priority.

So I created a methodology to determine if survivors could be found. I took Roman names unique to Pompeii or Herculaneum – such as Numerius Popidius and Aulus Umbricius – and searched for people with those names who lived in surrounding communities in the period after the eruption. I also looked for additional evidence, such as improved infrastructure in neighboring communities to accommodate migrants.

After eight years of scouring databases of tens of thousands of Roman inscriptions on places ranging from walls to tombstones, I found evidence of over 200 survivors in 12 cities. These municipalities are primarily in the general area of Pompeii. But they tended to be north of Mount Vesuvius, outside the zone of the greatest destruction.

It seems as though most survivors stayed as close as they could to Pompeii. They preferred to settle with other survivors, and they relied on social and economic networks from their original cities as they resettled.

Some migrants prosper:

Some of the families that escaped apparently went on to thrive in their new communities.

The Caltilius family resettled in Ostia – what was then a major port city to the north of Pompeii, 18 miles from Rome. There, they founded a temple to the Egyptian deity Serapis. Serapis, who wore a basket of grain on his head to symbolize the bounty of the earth, was popular in harbor cities like Ostia dominated by the grain trade. Those cities also built a grand, expensive tomb complex decorated with inscriptions and large portraits of family members.

Members of the Caltilius family married into another family of escapees, the Munatiuses. Together, they created a wealthy, successful extended family.

The second-busiest port city in Roman Italy, Puteoli – what’s known as Pozzuoli today – also welcomed survivors from Pompeii. The family of Aulus Umbricius, who was a merchant of garum, a popular fermented fish sauce, resettled there. After reviving the family garum business, Aulus and his wife named their first child born in their adopted city Puteolanus, or “the Puteolanean.”

Others fall on hard times:

Not all the survivors of the eruption were wealthy or went on to find success in their new communities. Some had already been poor to begin with. Others seemed to have lost their family fortunes, perhaps in the eruption itself.

Fabia Secundina from Pompeii – apparently named for her grandfather, a wealthy wine merchant – also ended up in Puteoli. There, she married a gladiator, Aquarius the retiarius, who died at the age of 25, leaving her in dire financial straits.

Three other very poor families from Pompeii – the Avianii, Atilii and Masuri families – survived and settled in a small, poorer community called Nuceria, which goes by Nocera today and is about 10 miles (16.1 kilometers) east of Pompeii.

According to a tombstone that still exists, the Masuri family took in a boy named Avianius Felicio as a foster son. Notably, in the 160 years of Roman Pompeii, there was no evidence of any foster children, and extended families usually took in orphaned children. For this reason, it’s likely that Felicio didn’t have any surviving family members.

This small example illustrates the larger pattern of the generosity of migrants – even impoverished ones – toward other survivors and their new communities. They didn’t just take care of each other; they also donated to the religious and civic institutions of their new homes.

For example, the Vibidia family had lived in Herculaneum. Before it was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius, they had given lavishly to help fund various institutions, including a new temple of Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty and fertility.

One female family member who survived the eruption appears to have continued the family’s tradition: Once settled in her new community, Beneventum, she donated a very small, poorly made altar to Venus on public land given by the local city council.

How would survivors be treated today?

While the survivors resettled and built lives in their new communities, government played a role as well.

The emperors in Rome invested heavily in the region, rebuilding properties damaged by the eruption and building new infrastructure for displaced populations, including roads, water systems, amphitheaters and temples.

This model for post-disaster recovery can be a lesson for today. The costs of funding the recovery never seems to have been debated. Survivors were not isolated into camps, nor were they forced to live indefinitely in tent cities. There’s no evidence that they encountered discrimination in their new communities.

Instead, all signs indicate that communities welcomed the survivors. Many of them went on to open their own businesses and hold positions in local governments. And the government responded by ensuring that the new populations and their communities had the resources and infrastructure to rebuild their lives.

By Steven L. Tuck.

#More than 200 Survivors of Mount Vesuvius Eruption Discovered in Ancient Roman Records#Pompeii#Herculaneum#Mount Vesuvius#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#long post#long reads

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

david gilmour in ‘chit chat with oysters’ dir. adrian maben (1971)

#david gilmour#pink floyd#fave#dark side of the moon#live at pompeii#chit chat with oysters#adrian maben#pinkfloydedit#pinkfloydgifs#gifs*#mine*#david in this interview my beloved <3#also he licks his lips so many times here i love it#i didn’t include them all though because some of them are not when he’s recording#adrian why did you have to make so many of the shots so tight whenever they’re not in the studio#i’m still gonna make another set tho#probably one of him being done with everyone’s shit lol#he’s really funny here#and hot and pretty#but anyway happy birthday david 🥹

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the final Puella Historia event;

PUELLA MAGI AMARYLLIS

VS

PLINY THE ELDER

#why is the time option either just a day to a whole week?#can you tell I’m a history nerd yet?#don’t take this too seriously#magia record#madoka magica#magia record jp#pompeii#pliny the elder#fun fact#Pliny died via hypoxia while investigating the eruption#anime girl vs old man lmao

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Natural History of Fear is an absolutely batshit audio, not least because it leaves you sitting to the sound of a humming top for the final few minutes just so you can process how utterly batshit it just was

#the house of leaves of dw audios#not in the sense that there's a haunted house but in the amount of layers of fiction involved in the story#like you'll be hearing something and like cool standard listenening experience but then it will shift to the right hand side and surprise!#it was a recording all along! we're in the main action now! except then THAT will be a recording too and so on and so forth#and the (re)use of actors was very fun it was kinda the 'haha was 12 actually at pompeii that time with 10 and donna' idea to its#most extreme#and THEN THE END#'how many limbs do you have' 'eight of course' like HELLO.#like i have my problems with it this makes the second (or possibly 3rd depending on what happened in creed of the kromon) audio where#charley gets assaulted like come on.#but My God#doctor who#eight

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man, I was so hoping Amaryllis would be from Victorian period because of her outfit, it really seems similar to that sort of style to me. Or maybe Edwardian, that's already fairly similar to begin with. I everyone so far has had era-related outfits, I'm kinda baffled on this one. On the other hand, the idea of her possibly being responsible for the eruption of Mount Vesuvius is actually really hilarious, I'll admit. And it gives the possibility for her to be a Void type, without violating the game's rules for what makes Void types, Void types (wishing for a curse or misfortune of some form.)

I don't know I have many Thoughts and not all of them are cohesive

#she looks like she has funeral attire almost. or at least the veil gives me that vibe#which is a lil' unnerving given my current situation but it's also really cool#magia record#amaryllis of pompeii#rapo rambles

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#magia record#magireco#puella historia#amaryllis#that girl who is helping a couple I think? looks really pretty.#Also it's about the destruction of Pompeii from Mount Vesuvius#interesting

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Spotify#Pompeii#Bastille#Dan Smith#Mark Crew#Virgin Records#Rock Alternativo#Indie Pop#Synthpop#William Farquarson#Chris Wood#Jon Willoughby#lan Dudfield#Matty Green#Bob Ludwig

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pompeii 99 - Ignorence Is the Control / The Nothing Song / Love Me for My Mind (1982)

1 note

·

View note

Text

#perfect song perfect album!!!!#maybe my fave of 2022??#its like ilyjb and painless#then pompeii and the aldous harding record and bcnr#which tbf bcnr had me in a chokehold but it didnt stick as hard as jockstrap and nilüfer yanya#txt#everybody stream this album im not kidding#Spotify

0 notes

Text

Submerged Roman Villa Emerges in Lake Fusaro

The remains of a Roman village complex have started to emerge from the waters of Lake Fusaro due to a process of geological uplift known as bradysism.

Lake Fusaro is located in the comune of Bacoli in the Italian province of Naples. The lake and surrounding area are situated in the Phlegraean Fields, an active and volatile volcanic region of bradyseismic activity.

Bradyseism refers to the slow rise (positive bradyseism) or fall (negative bradyseism) of a section of the Earth’s surface, driven by the movement of magma or hydrothermal fluids beneath the ground.

The Phlegraean Fields sits within a collapsed caldera, namely a volcanic area formed by several volcanic edifices, which includes the Solfatara volcano, well known for its fumaroles (vents from which hot volcanic gases and vapours are emitted).

Adjacent to the lake are the partially submerged remains of the Roman town of Baiae, a popular resort in antiquity that gained a reputation for a “hedonistic lifestyle”. According to Sextus Propertius, a poet of the Augustan age during the 1st century BC, Baiae was a “vortex of luxury” and a “harbour of vice”.

On the opposite side of the Gulf of Naples are the remains of Roman Pompeii and Herculaneum, both major population centuries in antiquity that were buried under thick layers of ash and pumice during the AD 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

According to a study by the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, the area of Lake Fusaro has been rising since 2005, having rised in elevation by approximately 138 centimetres, 20 centimetres of which were recorded in 2024 alone.

This rapid acceleration has caused the seabed to rise and the shoreline to retreat, causing damage and difficult access to some ports and marinas along the coast.

An unexpected result of the bradyseismic activity is the emergence of a Roman villa visible in aerial photography. Josi Gerardo Della Ragione, the Mayor of Bacoli, explained that the villa likely had thermal baths, which will now be studied by the Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape of Naples.

#Submerged Roman Villa Emerges in Lake Fusaro#Roman town of Baiae#ancient artifacts#archeology#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

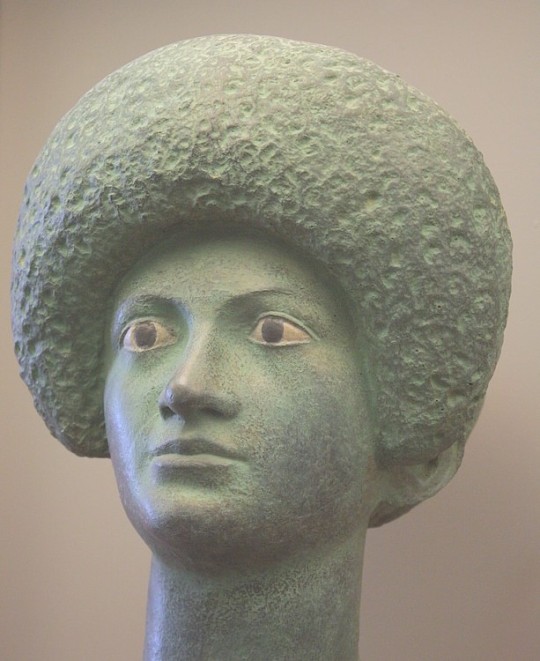

Roman Art

The Romans controlled such a vast empire for so long a period that a summary of the art produced in that time can only be a brief and selective one. Perhaps, though, the greatest points of distinction for Roman art are its very diversity, the embracing of art trends past and present from every corner of the empire and the promotion of art to such an extent that it became more widely produced and more easily available than ever before. In which other ancient civilization would it have been possible for a former slave to have commissioned his portrait bust? Roman artists copied, imitated, and innovated to produce art on a grand scale, sometimes compromising quality but on other occasions far exceeding the craftsmanship of their predecessors. Any material was fair game to be turned into objects of art. Recording historical events without the clutter of symbolism and mythological metaphor became an obsession. Immortalising an individual private patron in art was a common artist's commission. Painting aimed at faithfully capturing landscapes, townscapes, and the more trivial subjects of daily life. Realism became the ideal and the cultivation of a knowledge and appreciation of art itself became a worthy goal. These are the achievements of Roman art.

Art for All: Rome's Contribution

Roman art has suffered something of a crisis in reputation ever since the rediscovery and appreciation of ancient Greek art from the 17th century CE onwards. When art critics also realised that many of the finest Roman pieces were in fact copies or at least inspired by earlier and often lost Greek originals, the appreciation of Roman art, which had flourished along with all things Roman in the medieval and Renaissance periods, began to diminish. Another problem with Roman art is the very definition of what it actually is. Unlike Greek art, the vast geography of the Roman empire resulted in very diverse approaches to art depending on location. Although Rome long remained the focal point, there were several important art-producing centres in their own right who followed their own particular trends and tastes, notably at Alexandria, Antioch, and Athens. As a consequence, some critics even argued there was no such thing as 'Roman' art.

In more recent times a more balanced view of Roman art and a wider one provided by the successes of archaeology have ensured that the art of the Romans has been reassessed and its contribution to western art in general has been more greatly recognised. Even those holding the opinion that Classical Greek art was the zenith of artistic endeavour in the west or that the Romans merely fused the best of Greek and Etruscan art would have to admit that Roman art is nothing if not eclectic. Inheriting the Hellenistic world forged by Alexander the Great's conquests, with an empire covering a hugely diverse spectrum of cultures and peoples, their own appreciation of the past, and clear ideas on the best way to commemorate events and people, the Romans produced art in a vast array of forms. Seal-cutting, jewellery, glassware, mosaics, pottery, frescoes, statues, monumental architecture, and even epigraphy and coins were all used to beautify the Roman world as well as convey meaning from military prowess to fashions in aesthetics.

Artworks were looted from conquered cities and brought back for the appreciation of the public, foreign artists were employed in Roman cities, schools of art were created across the empire, technical developments were made, and workshops sprang up everywhere. Such was the demand for artworks, production lines of standardised and mass produced objects filled the empire with art. And here is another factor in Rome's favour, the sheer quantity of surviving artworks. Such sites as Pompeii, in particular, give a rare insight into how Roman artworks were used and combined to enrich the daily lives of citizens. Art itself became more personalised with a great increase in private patrons of the arts as opposed to state sponsors. This is seen in no clearer form than the creation of lifelike portraits of private individuals in paintings and sculpture. Like no other civilization before it, art became accessible not just to the wealthiest but also to the lower middle classes.

Continue reading...

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889), The Birth of Venus (1863), oil on canvas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The older accounts of the birth of Aphrodite link her to the myth of the Titan Cronos/Saturn castrating his father Uranus, whose severed genitals are thrown into the sea. There, they float past the islands of Cythera and Cyprus, giving rise to alternative epithets for Aphrodite of Cytherea and Cypris. On the shore of Cyprus, Aphrodite is then born from them, with allusions to semen as foam of the waves.

A later origin is given by Homer in his Iliad, in which Aphrodite is the daughter of Zeus by Dione, a Titaness and Oceanid who was one of Zeus’s early wives. Subsequent accounts of the origins of Aphrodite are attempts to reconcile these two conflicting stories.

Depictions of the birth of Aphrodite are among the oldest European mythological paintings of which we have records. Apelles of Kos, one of the most renowned of the great painters of ancient Greece, is claimed to have been active around 330 BCE. Among the eight or more major works attributed to him is Aphrodite Anadyomene, in which the goddess Aphrodite rises from the sea. This achieved fame in part because his model for Aphrodite was a former mistress of Alexander the Great, Campaspe, according to the writings of Pliny the Elder.

Unknown, Aphrodite Anadyomenes (before 79 CE), fresco, dimensions not known, The House of Venus, Pompeii.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

“At a point where some were ready to write off the band as aging, lazy veterans, they came back with Tinderbox, one of their strongest LPs in years. [John Valentine] Carruthers fits in well, his rich playing stylistically similar to both [Robert] Smith’s and [John] McGeoch’s; the rhythm section is as steady as ever. The big plus is punk’s original princess herself – Siouxsie’s voice has never been so warm and tuneful as it is on tracks like “The Sweetest Chill”, “Cannons” and the great single “Cities in Dust.””

/ From The Fourth Edition of the Trouser Press Record Guide (1991) /

Released on this day 39 years ago (21 April 1986): Tinderbox, the seventh studio album by English punk royalty Siouxsie and the Banshees. This one is a sacred text and eternal sentimental favourite of mine dating back to my teens. That naggingly catchy minimalist opening toy piano of “Cities in Dust” immediately plunges me back to “alternative night” at Oliver’s Bar at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario in the eighties. (I inevitably would have been wearing black cut-off jean shorts and a black pocket T from The Gap). In addition to the mighty Pompeii-inspired “Cities in Dust”, I love second single “Candyman”, with Siouxsie reflecting on childhood sexual abuse (“And all the children, he warns, "Don't tell" / Those threats are sold / With their guilt and shame / They think they're to blame for Candyman …”), the gloomy and macabre “This Unrest” (“This unrest crucifies my chest / Without anaesthetic it cuts / Through tumorous flesh ...”) and “The Sweetest Chill”, with lyrics that suggest something Gomez would vow to Morticia (“Fearing you but calling your name / Icy breath encases my skin / Fingers like a fountain of needles / Shiver along my spine / And rain down so divine …”). Now sing along with me: “Hot and burning in your nostrils / Pouring down your gaping mouth / Your molten bodies, blanket of cinders / Caught in the throes …” Pictured: portrait of Siouxsie by Pierre Terrasson, 1986.

#siouxsie and the banshees#siouxsie sioux#tinderbox#lobotomy room#pierre terrasson#punk#high priestess of punk#goth#punk rock#punk royalty#punk veteran#punk icon#gloomy#macabre#morbidly beautiful#goth rock#post punk#cities in dust

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been listening to an audiobook about Pompeii and I wish I had the text itself so I could directly quote something really interesting that the author talks about with regards to sex work in the period.

What she says is that, while brothels were certainly extant, women who sold sex were more often than not the same ones who worked in bakeries or as laundresses or generally had any other day job. It was too lucrative a practice for any woman who had to earn money to survive not to have on the side, and because of that fact—that these women would be identified in official records only by their “actual” trade—it’s extremely hard to quantify exactly how many sex workers there actually were.

Like??? No matter how much time passes things stay the same. Of course today we can probably get a more accurate census thanks to porn site data, but the fact remains that sex work was and still is far, FAR more common than anyone thinks it might be.

Lucretia who dyed your cloak might also accept “visitors” into her quarters late at night. Your coworker Rebecca could be camgirling on weekends with an OF on the side.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carbonized money purse found in Herculaneum.

Because wood is perishable, items like this were not preserved in the archeological record and it is only through excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum that we know these existed at all.

#ancient rome#roman empire#ancient culture#ancient civilisations#daily life in history#herculaneum#mt vesuvius

376 notes

·

View notes