#Pomerantsev

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Tegen emotionele propaganda hebben argumenten niet veel zin

Omdat de politieke partij D66 het niet zo geweldig had gedaan bij de Kamerverkiezingen van 2022 werd er door het partijbestuur een commissie ingesteld die de dieperliggende oorzaken van het falen bloot moest leggen. Er kwam een rapport waarin onder andere gezegd werd dat de op zich heel redelijke en verstandige standpunten van D66, vertolkt door bewindslieden en andere partijprominenten die…

View On WordPress

#BBC#Blokzijl#D66#Engeland#Ernst Röhm#Goebbels#Hitler#Muriel Spark#Navo#Nazi#Nazi-Duitsland#Pomerantsev#propaganda#PVV#Radio Oranje#Reichstag#Rinus van der Lubbe#SA#Sefton Delmer#Stauffenberg#Tweede Wereldoorlog#Wilders#Woburn

0 notes

Text

Historically, some of the biggest Russian opponents to domestic repressions are imperialists. Solzhenitsyn, most famously, is, on the one hand, bravely fighting the GULAG, and on the other hand - a vile imperialist with a sense of fascism. These aren't new phenomena, in many ways. Somehow one feels that [moving away from imperialism] is unlikely in Russia, because it goes so deep. This is just the latest Russian invasion of Ukraine, this is not just one war, this has been going on for centuries. Russian imperialism is embedded in Russian humour, Russian literature, codes of thinking. It's not about statements. It's not just about policies. When Pushkin writes, I don't know, "Кавказ подо мною" ("The Caucasus lies below me"), one of his famous poems... the amount of imperialist psychology that goes into saying that - that goes very, very deep. So until those much, much deeper sort of deep cultural roots of Russian imperialism, racism and oppression are addressed, nothing is changed. So let's think what we have agency over, in a way. [...] we can change the way Russia is perceived globally and in the West. Because this idea that Russia is a great power that has the right to a sphere of influence and that has the right to suppress others because it's great - that sits very deep in people's heads across the world. We can start working on that. So why don't we start working on that? Let's get people in my world - Britain, America - to re-read the Russian classics and understand how much imperialism and oppression of others there's there. Let's start de-mystifying this idea of "the Russian mystic soul" and really start rooting it to very specific histories of violence and oppression. Let's start changing the way Russia is perceived, so it's no longer seen as inevitable and so vast and huge that you have to drop on your knees in front of it, which still sits in people's heads. That means changing the way the universities overfocus on Russia studies and completely silence the voices of Ukrainians, Georgians, Kazakhs... There's so much we can do that will make people's perceptions of Russia rooted in reality. And they will help gain self-confidence to say, "Stop, we're not dependent on you".

Peter Pomerantsev

#peter pomerantsev#russian imperialism#russian culture#ruscism#russian invasion of ukraine#russian colonialism

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1941 a secret British radio station called on Germans to rise up against Hitler. Run by German exiles, it was explicitly left wing. The station’s target audience was “the Good German”. Its broadcasts were serious and idealistic: a ray of light amid totalitarian darkness. They were also a complete flop. With Nazi propaganda rampant, and Hitler’s armies seemingly invincible and on the march across Europe, few bothered to listen in.

It was at this point that Britain’s wartime intelligence services tried a more radical approach. That summer, a talented journalist called Sefton Delmer was given the job of beating the Nazis at their own information game. Delmer spent his childhood in Berlin and spoke fluent German. In the early 1930s he chronicled Hitler’s rise to power – flying in the Führer’s plane and attending his mass rallies – as a correspondent for the Daily Express.

Working from an English country house, Delmer launched an experimental radio station. He called it Gustaf Siegfried Eins, or GS1. Instead of invoking lofty precepts, or Marxism, Delmer targeted what he called the “inner pig-dog”. The answer to Goebbels, Delmer concluded, was more Goebbels. His radio show became a grotesque cabaret aimed at the worst and most Schwein-like aspects of human nature.

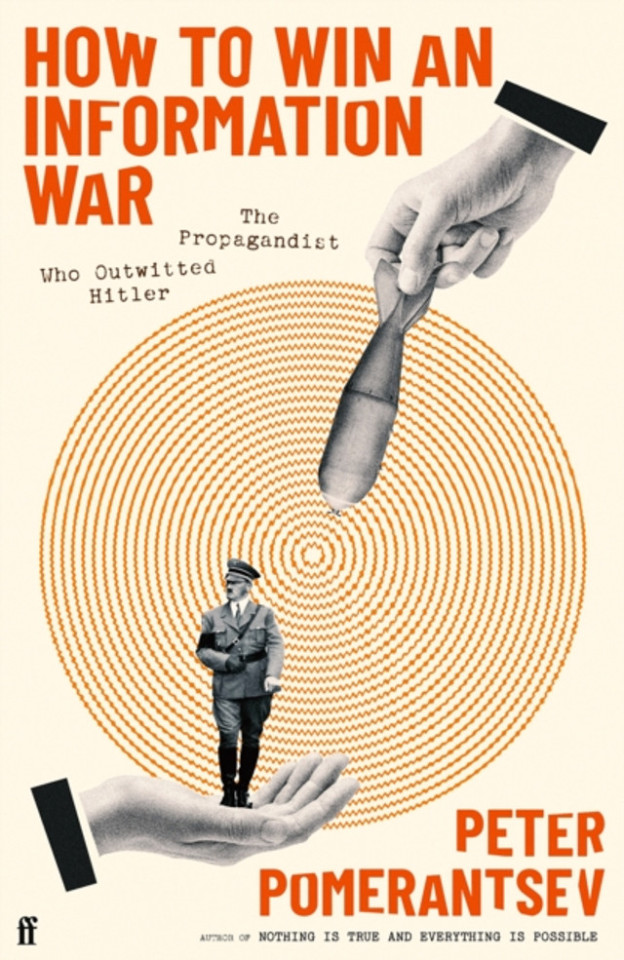

As Peter Pomerantsev writes in his compelling new study How to Win an Information War, Delmer was a “nearly forgotten genius of propaganda”. GS1 backed Hitler and was staunchly anti-Bolshevik. Its mysterious leader, dubbed der Chef, ridiculed Churchill using foul Berlin slang. At the same time the station lambasted the Nazi elite as a group of decadent crooks. They stole and whored, it said, as British planes bombed and decent Germans suffered.

Delmer’s goal was to undermine nazism from within, by turning ordinary citizens against their aloof party bosses. A cast of Jewish refugees and former cabaret artists played the role of Nazis. Recordings took place in a billiards room, located inside the Woburn Abbey estate in Bedfordshire, a centre of wartime operations. Some of the content was real. Other elements were made up, including titillating accounts of SS orgies at a Bavarian monastery.

The station was a sensation. Large numbers of Germans tuned in. The US embassy in Berlin – America had yet to enter the war – thought it to be the work of German nationalists or disgruntled army officers. The Nazis fretted about its influence. One unimpressed person was Stafford Cripps, the future chancellor of the exchequer, who complained to Anthony Eden, the then minister for foreign affairs, about the station’s use of “filthy pornography”.

By 1943, Delmer’s counter-propaganda operation had grown. He and his now expanded team ran a live news bulletin aimed at German soldiers, the Soldatensender Calais, as well as a series of clandestine radio programmes in a variety of languages. Delmer’s artist wife Isabel joined in. She drew explicit pictures showing a blonde woman having sex with a dark-skinned foreigner. Partisans sent the pamphlets to homesick German troops stationed in Crete.

Others who made a contribution to Delmer’s productions included Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, and the 26-year-old future novelist Muriel Spark. Fleming worked for naval intelligence. He brought titbits of information that made the show feel genuine, including the latest results from U-boat football leagues. Many Germans guessed the station was British. But they listened anyway, feeling it represented “them”.

Pomerantsev is an expert on propaganda and the author of two previous books on the subject, Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible and This Is Not Propaganda. The son of political dissidents in Kyiv, he was born in Ukraine and grew up in London. During the 00s he lived in Moscow and worked there as a TV producer. Since Vladimir Putin’s 2022 invasion he has been part of a project that documents Russian war crimes in Ukraine.

Like Delmer, Pomeranstev has personal experience of two rival cultures: one authoritarian, the other liberal and democratic. He draws parallels between the fascist 1930s and our own populist age. The same “underlying mindset” can be seen in dictators such as Putin and Xi Jinping, and wannabe strongmen and bullies such as Donald Trump. “Propagandists across the world and across the ages play on the same emotional notes like well-worn scales,” he observes.

In Pomerantsev’s view, propaganda works not because it convinces, or even confuses. Its real power lies in its ability to convey a sense of belonging, he argues. Those left behind feel themselves emboldened and part of a special community. It is a world of grievance, victimhood and enemies, where facts are meaningless. What matters are feelings and the illusion propaganda lends of “individual agency”. Its practitioners bend reality. And – as with Putin’s fictions about Ukraine – make murder possible.

The book offers a few ideas as to how we might fight back. When horrors were uncovered in Bucha, the town near Kyiv where Russian soldiers executed civilians, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, appealed to the Russian people. This didn’t cut through. Most preferred to believe the version shown on state TV: that Moscow was waging a defensive fight against “neo-Nazis”. It was a comforting lie that absolved Russians of personal responsibility.

Ukrainian activists hit a similar wall when they cold-called Russians and told them about the destruction caused by Kremlin bombing. Many called relatives in St Petersburg and other Russian cities to explain they were under attack. Typically, their family members did not believe them. “They really brainwashed you over there,” one said.

The activists had more success when they mentioned taxes or travel restrictions – issues that spoke to the self-interested “pig-dog”. Pomerantsev suggests that Delmer’s approach worked because he allowed people to care about the truth again, nudging them towards independent thought, while avoiding the pitfall of obvious disloyalty. He brought wit and creativity to his anti-propaganda efforts as well, turning his radio shows into bravura transmissions.

Pomerantsev makes an intriguing comparison between der Chef and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Russian oligarch who in summer 2023 staged a short-lived rebellion against Putin. Two months later, Prigozhin died in a plane crash. The oligarch was a charismatic figure who roasted Russia’s generals for their incompetent handling of the war. He used earthy prison slang. It was this ability to communicate in plain language that made him popular – and a rival.

The book muses on whether Delmer was ultimately good or bad. Are tricks and subterfuge justified in pursuit of noble goals? It concludes that the journalist’s greatest insight was his understanding of his own ordinariness, and how this might be exploited by unscrupulous governments and rabble-rousing individuals. “He was vulnerable to propaganda for the same reasons we all are – through the need to fit in and conform,” Pomerantsev notes.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ukraine Through the Eyes of Peter Pomerantsev

youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 June 2023

Beneath the veneer of Russian military “tactics”, you see the stupid leer of destruction for the sake of it. The Kremlin can’t create, so all that is left is to destroy. Not in some pseudo-glorious self-immolation, the people behind atrocities are petty cowards, but more like a loser smearing their faeces over life. In Russia’s wars the very senselessness seems to be the sense.

After the casual mass executions at Bucha; after the bombing of maternity wards in Mariupol; after the laying to waste of whole cities in Donbas; after the children’s torture chambers, the missiles aimed at freezing civilians to death in the dead of winter, we now have the apocalyptic sight of the waters of the vast Dnipro, a river that when you are on it can feel as wide as a sea, bursting through the destroyed dam at Kakhovka. The reservoir held as much water as the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Its destruction has already submerged settlements where more than 40,000 people live. It has already wiped out animal sanctuaries and nature reserves. It will decimate agriculture in the bread basket of Ukraine that feeds so much of the world, most notably in the Middle East and Africa. To Russian genocide add ecocide.

The dam has been controlled by Russia for more than a year. The Ukrainian government has been warning that Russia had plans to blast it since October.

Seismologists in Norway have confirmed that massive blasts, the type associated with explosives rather than an accidental breach, came from the reservoir the night of its destruction. Some – including the American pro-Putin media personality Tucker Carlson – argue Russia couldn’t be behind the devastation, given the damage has spread to Russian-controlled territories, potentially restricting water supply to Crimea. But if “Russia wouldn’t damage its own people” is your argument then it’s one that doesn’t hold, pardon the tactless pun, much water. One of the least accurate quotes about Russia is Winston Churchill’s line about it being “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” This makes it sound as if Russia is driven by some theory of rational choice – when century after century the opposite appears to be the case.

Few have captured the Russian cycle of self-destruction and the destruction of others as well as the Ukrainian literary critic Tetyana Ogarkova. In her rewording of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Russian classic novel Crime and Punishment, a novel about a murderer who kills simply because he can, Ogarkova calls Russia a culture where you have “crime without punishment, and punishment without crime”. The powerful murder with impunity; the victims are punished for no reason.

When not bringing humanitarian aid to the front lines, Ogarkova presents a podcast together with her husband, the philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko. It’s remarkable for showing two people thinking calmly while under daily bombardment. It reminds me of German-Jewish philosophers such as Walter Benjamin, who kept writing lucidly even as they fled the Nazis. As they try to make sense of the evil bearing down on their country, Ogarkova and Yermolenko note the difference between Hitler and Stalin: while Nazis had some rules about who they punished (non-Aryans; communists) in Stalin’s terror anyone could be a victim at any moment. Random violence runs through Russian history.Reacting to how Vladimir Putin’s Russia is constantly changing its reasons for invading Ukraine – from “denazification” to “reclaiming historic lands” to “Nato expansion” – Ogarkova and Yermolenko decide that the very brutal nature of the invasion is its essence: the war crimes are the point. Russia claims to be a powerful “pole” in the world to balance the west – but has failed to create a successful political model others would want to join. So it has nothing left to offer except to drag everyone down to its own depths.“How dare you live like this,” went a resentful piece of graffiti by Russian soldiers in Bucha. “What’s the point of the world when there is no place for Russia in it,” complains Putin. After the dam at Kakhovka was destroyed, a General Dobruzhinsky crowed on a popular Russian talkshow: “We should blow up the Kyiv water reservoir too.” “Why?” asked the host. “Just to show them.” But, as Ogarkova and Yermolenko explore, Russians also send their soldiers to die senselessly in the meat grinder of the Donbas, their bodies left uncollected on the battlefield, their relatives not informed of their death so as to avoid paying them. On TV, presenters praise how “no one knows how to die like us”. Meanwhile, villagers on the Russian-occupied side of the river are being abandoned by the authorities. Being “liberated” by Russia means joining its empire of humiliation.

Where does this drive to annihilation come from? In 1912 the Russian-Jewish psychoanalyst Sabina Spielrein – who was murdered by the Nazis, while her three brothers were killed in Stalin’s terror -first put forward the idea that people were drawn to death as much as to life. She drew on themes from Russian literature and folklore for her theory of a death drive, but the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, first found her ideas too morbid. After the First World War, he came to agree with her. The desire for death was the desire to let go of responsibility, the burden of individuality, choice, freedom – and sink back into inorganic matter. To just give up. In a culture such as Russia’s, where avoiding facing up to the dark past with all its complex webs of guilt and responsibility is commonplace, such oblivion can be especially seductive.

But Russia is also sending out a similar message to Ukrainians and their allies with these acts of ultra-violent biblical destruction: give in to our immensity, surrender your struggle. And for all Russia’s military defeats and actual socio-economic fragility, this propaganda of the deed can still work.

The reaction in the west to the explosion of the dam has been weirdly muted. Ukrainians are mounting remarkable rescue operations, while Russia continues to shell semi-submerged cities, but they are doing it more or less alone. Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, has been mystified by the “zero support” from international organisations such as the UN and Red Cross.

Perhaps the relative lack of support comes partly because people feel helpless in the face of something so immense, these Cecil B DeMille-like scenes of giant rivers exploding. It’s the same helplessness some feel when faced with the climate crisis. It’s apposite that the strongest response to Russia’s ecocide came not from governments but the climate activist Greta Thunberg, who clearly laid the blame of what happened on Russia and demanded it be held accountable. But there’s been barely a peep out of western governments or the UN.

Pushing the strange lure of death, oblivion and just giving up is the Russian gambit. How much life do we have left in us?

Peter Pomerantsev is the author of Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: Adventures in Modern Russia

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil fuels are not just terrible for the planet, they are bad for democracy. A disproportionate number of major oil and gas exporters are autocracies such as Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela.

Russia in particular uses fossil fuel sales to fund repression at home and imperialism abroad.

Putin appears weaker than ever – and for a ruler who relies on projecting strength, that’s a bad look. To further dull Putin’s fading aura of invincibility, and to ultimately lead to a reversal of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, we need to undermine the pillars his strongman myth is based on: colonial conquest, unregulated capitalism and climate abuse. As questions are raised about his ability to rule, Putin will claim that despite the efforts of the nefarious “collective west”, the Russian economy can stabilise because the world needs Russian fossil fuels; that the need of western companies to make money in Russia means it will never be truly isolated; that for all his blunders on the battlefield, he can still hold on to swathes of Ukraine and its resources, which he will dole out between the Russian system’s stakeholders for whom the risk of sticking with Putin will thus still be smaller than the risk of going against him.

No matter what the source of the oil or gas we consume, we push up the international price of those commodities whenever we use them. It's supply and demand; when we reduce our demand, the price goes down and dictators/theocrats get lower profits.

We need to recognise the fact that human rights, security and economic ties are deeply intertwined, and to alter our behaviour accordingly. Let’s stop selling dictators the rope with which they hang people: our neighbours – and ultimately us. And if there’s one base element that powers Putin’s claims to invincibility, it’s reliance on fossil fuels. The battle against Putin is also the battle against climate crisis. As Prof Alexander Etkind lays out in his new book, Russia Against Modernity, Putin’s economy has been up to two-thirds dependent on oil and gas exports, largely to Europe, and crucially through pipelines that cross Ukraine. Etkind argues that Putin launched his invasion in part to control this flow. Moreover, he wanted to destabilise Europe, flooding it with refugees and instilling so much chaos and fear that Europe would be forced to abandon plans for net zero carbon emissions by 2050. As so often in the course of this war, Putin’s aims have backfired. The invasion has led to a decrease in dependence on Russian energy. Putin’s aura of fossil-fuelled invincibility has been shaken, but we are only part of the way there. Faster decarbonisation is the most sustainable way to not only undermine Putin, but also to limit the opportunity for future Russian leaders and other resource-rich authoritarians to wage aggressive wars.

Decarbonization is also de-Putinization. We contribute to peace and stability when we lessen the amount of fossil fuels we consume. And, of course, we slow down and eventually halt the warming of our planet.

Using these late 19th century sources of energy encourages despotic autocracies while making Earth less livable. It's time to say до свидания to fossil fuels.

#fossil fuels#climate change#invasion of ukraine#dictatorships#autocracies#theocracies#russia#vladimir putin#decarbonization#net zero#peter pomerantsev#alexander etkind#human rights#stability#россия#владимир путин#путин хуйло#диктатура#самодержавие#ископаемое топливо#изменение климата#союз постсоветских клептократических ватников#руки прочь от украины!#геть з україни#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#слава україні!#героям слава!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a gift article

“In normal times, Americans don’t think much about democracy. Our Constitution, with its guarantees of free press, speech, and assembly, was written more than two centuries ago. Our electoral system has never failed, not during two world wars, not even during the Civil War. Citizenship requires very little of us, only that we show up to vote occasionally. Many of us are so complacent that we don’t bother. We treat democracy like clean water, something that just comes out of the tap, something we exert no effort to procure.

“But these are not normal times.”

I wrote those words in October 2020, at a time when some people feared voting, because they feared contagion. The feeling that “these are not normal times” also came from rumors about what Donald Trump’s campaign might do if he lost that year’s presidential election. Already, stories that Trump would challenge the validity of the results were in circulation. And so it came to pass.

This time, we are living in a much different world. The predictions of what might happen on November 5 and in the days that follow are not based on rumors. On the contrary, we can be absolutely certain that an attempt will be made to steal the 2024 election if Kamala Harris wins. Trump himself has repeatedly refused to acknowledge the results of the 2020 election. He has waffled on and evaded questions about whether he will accept the outcome in 2024. He has hired lawyers to prepare to challenge the results.

Trump also has a lot more help this time around from his own party. Strange things are happening in state legislatures: a West Virginia proposal to “not recognize an illegitimate presidential election” (which could be read as meaning not recognize the results if a Democrat wins); a last-minute push, ultimately unsuccessful, to change the way Nebraska allocates its electoral votes. Equally weird things are happening in state election boards. Georgia’s has passed a rule requiring that all ballots be hand-counted, as well as machine-counted, which, if not overturned, will introduce errors—machines are more accurate—and make the process take much longer. A number of county election boards have in recent elections tried refusing to certify votes, not least because many are now populated with actual election deniers, who believe that frustrating the will of the people is their proper role. Multiple people and groups are also seeking mass purges of the electoral rolls.

Anyone who is closely following these shenanigans—or the proliferation of MAGA lawsuits deliberately designed to make people question the legitimacy of the vote even before it is held—already knows that the challenges will multiply if the presidential vote is as close as polls suggest it could be. The counting process will be drawn out, and we may not know the winner for many days. If the results come down to one or two states, they could experience protests or even riots, threats to election officials, and other attempts to change the results.

This prospect can feel overwhelming: Many people are not just upset about the possibility of a lost or stolen election, but oppressed by a sensation of helplessness. This feeling—I can’t do anything; my actions don’t matter—is precisely the feeling that autocratic movements seek to instill in citizens, as Peter Pomerantsev and I explain in our recent podcast, Autocracy in America. But you can always do something. If you need advice about what that might be, here is an updated citizen’s guide to defending democracy.

Help Out on Voting Day—In Person

First and foremost: Register to vote, and make sure everyone you know has done so too, especially students who have recently changed residence. The website Vote.gov has a list of the rules in all 50 states, in multiple languages, if you or anyone you know has doubts. Deadlines have passed in some states, but not all of them.

After that, vote—in person if you can. Because the MAGA lawyers are preparing to question mail-in and absentee ballots in particular, go to a polling station if at all possible. Vote early if you can, too: Here is a list of early-voting rules for each state.

Secondly, be prepared for intimidation or complications. As my colleague Stephanie McCrummen has written, radicalized evangelical groups are organizing around the election. One group is planning a series of “Kingdom to the Capitol” rallies in swing-state capitals, as well as in Washington, D.C.; participants may well show up near voting booths on Election Day. If you or anyone you know has trouble voting, for any reason, call 866-OUR-VOTE, a hotline set up by Election Protection, a nonpartisan national coalition led by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

If you have time to do more, then join the effort. The coalition is looking for lawyers, law students, and paralegals to help out if multiple, simultaneous challenges to the election occur at the county level. Even people without legal training are needed to serve as poll monitors, and of course to staff the hotline. In the group’s words, it needs people to help voters with “confusing voting rules, outdated infrastructure, rampant misinformation, and needless obstacles to the ballot box.”

If you live in Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, or Wisconsin, you can also volunteer to help All Voting Is Local, an organization that has been on the ground in those states since before 2020 and knows the rules, the officials, the potential threats. It, too, is recruiting legal professionals, as well as poll monitors. If you don’t live in one of those states, you can still make a financial contribution.

Wherever you live, consider working at a polling station. All Voting Is Local can advise you if you live in one of its eight states, but you can also call your local board of elections. More information is available at PowerThePolls.org, which will send you to the right place. The site explains that “our democracy depends on ordinary people who make sure every election runs smoothly and everyone's vote is counted—people like you.”

Wherever you live, it’s also possible to work for one of the many get-out-the-vote campaigns. Consider driving people to the voting booth. Find your local group by calling the offices of local politicians, members of Congress, state legislators, and city councillors. The League of Women Voters and the NAACP are just two of many organizations that will be active in the days before the election, and on the day itself. Call them to ask which local groups they recommend. Or, if you are specifically interested in transporting Democrats, you can volunteer for Rideshare2Vote.

If you know someone who needs a ride, then let them know that the ride-hailing company Lyft is once again working with a number of organizations, including the NAACP, the National Council of Negro Women, Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, the National Council on Aging, Asian and Pacific Islander American Vote, and the Hispanic Federation. Contact any of them for advice about your location. Also try local religious congregations, many of whom organize rides to the polls.

Smaller gestures are needed too. If you see a long voting line, or if you find yourself standing in one, report it to Pizza to the Polls and the group will send over some free pizza to cheer everyone up.

Join Something Now

Many people have long been preparing for a challenge to the election and a battle in both the courts and the media. You can help them by subscribing to the newsletters of some of the organizations sponsoring this work, donating money, and sharing their information with others. Don’t wait until the day after the vote to find groups you trust: If a crisis happens, you will not want to be scouring the internet for information.

Among the organizations to watch is the nonpartisan Protect Democracy, which has already launched successful lawsuits to secure voting rights in several states. Another is the States United Democracy Center, which collaborates with police as well as election workers to make sure that elections are safe. Three out of four election officials say that threats to them have increased; in some states, the danger will be just as bad the day after the election as it was the day before, or maybe even worse.

The Brennan Center for Justice, based at NYU, researches and promotes concrete policy proposals to improve democracy, and puts on public events to discuss them. Its lawyers and experts are preparing not only for attempts to steal the election, but also, in the case of a Trump victory, for subsequent assaults on the Constitution or the rule of law.

For voters who lean Democratic, Democracy Docket also offers a wealth of advice, suggestions, and information. The group’s lawyers have been defending elections for many years. For Republicans, Republicans for the Rule of Law is a much smaller group, but one that can help keep people informed.

Talk With People

In case of a real disaster—an inconclusive election or an outbreak of violence—you will need to find a way to talk about it, including a way to speak with friends or relatives who are angry and have different views. In 2020, I published some suggestions from More in Common, a research group that specializes in the analysis of political polarization, for how to talk with people who disagree with you about politics, as well as those who are cynical and apathetic. I am repeating here the group’s three dos and three don’ts:

•Do talk about local issues: Americans are bitterly polarized over national issues, but have much higher levels of trust in their state and local officials. •Do talk about what your state and local leaders are doing to ensure a safe election. •Do emphasize our shared values—the large majority of Americans still feel that democracy is preferable to all other forms of government—and our historical ability to deliver safe and fair elections, even in times of warfare and social strife. •Don’t, by contrast, dismiss people’s concerns about election irregularities out of hand. Trump and his allies have repeatedly raised the specter of widespread voter fraud in favor of Democrats. Despite a lack of evidence for this notion, many people may sincerely believe that this kind of electoral cheating is real. •Don’t rely on statistics to make your case, because people aren’t convinced by them; talk, instead, about what actions are being taken to protect the integrity of the vote. •Finally, don’t inadvertently undermine democracy further: Emphasize the strength of the American people, our ability to stand up to those who assault democracy. Offer people a course of action, not despair.

As a Last Resort, Protest

As in 2020, protest remains a final option. A lot of institutions, including some of those listed above, are preparing to step in if the political system fails. But if they all fail as well, remember that it’s better to protest in a group, and in a coordinated, nonviolent manner. Many of the organizations I have listed will be issuing regular statements right after the election; follow their advice to find out what they are doing. Remember that the point of a protest is to gain supporters—to win others over to your cause—and not to make a bad situation worse. Large, peaceful gatherings will move and convince people more than small, angry ones. Violence makes you enemies, not friends.

Finally, don’t give up: There is always another day. Many of your fellow citizens also want to protect not just the electoral system but the Constitution itself. Start looking for them now, volunteer to help them, and make sure that they, and we, remain a democracy where power changes hands peacefully.

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many people are not just upset about the possibility of a lost or stolen election, but oppressed by a sensation of helplessness. This feeling—I can’t do anything; my actions don’t matter—is precisely the feeling that autocratic movements seek to instill in citizens, as Peter Pomerantsev and I explain in our recent podcast, Autocracy in America. But you can always do something. If you need advice about what that might be, here is an updated citizen’s guide to defending democracy.

First and foremost: Register to vote, and make sure everyone you know has done so too, especially students who have recently changed residence. The website Vote.gov has a list of the rules in all 50 states, in multiple languages, if you or anyone you know has doubts. Deadlines have passed in some states, but not all of them.

After that, vote—in person if you can. Because the MAGA lawyers are preparing to question mail-in and absentee ballots in particular, go to a polling station if at all possible. Vote early if you can, too: Here is a list of early-voting rules for each state.

------

The articles has links on how to help or get help.

Republicans are only 25% of the population. If every eligible voter who disagrees with them would actually vote, we would win in a landslide!

Use the site below to access the article.

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you give book recs? If you do, can you recommend books on post-soviet Russia? (specifically on post-sovietness) thank you in advance.

Nothing Is True And Everything Is Possible, by Peter Pomerantsev.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yuri Annenkov - Illustration of the Italian negatives by Kirill Pomerantsev

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

GUM (XIX c., arch.V. G. Šuchov, A. Pomerantsev) - Moskow, 2012

#travel#russia#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#monochrome#architecture#b&w photography#urban landscape#urban aesthetic#b&w street photography#department stores

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the cultural context and in the historical context, Russia has been attacking Ukraine for hundreds of years. This is just the latest iteration. This is embedded... Russian sense of ownership of Ukraine is embedded in Russian literature, Russian education, and so the idea that Putin just came up with it is absurd. I mean, just historically, this is clearly part of Russian culture and Russian history. This is just what they do. This is not the first time they're trying a genocide [in Ukraine]. So obviously it's not just Putin, that [would be] just ignoring history.

Peter Pomerantsev

#peter pomerantsev#russian imperialism#ruscism#ukraine#russian invasion of ukraine#russian culture#history

375 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the emoji ask game part II: 🦗Do you write in sequence or jump around? 🚿Where do your best ideas seem to strike? 🍎What's something you learned while researching for a fic?

🦗 - it took me an insanely long time to figure out what this emoji was lol. Anyways yes I 100% jump around, I try to have a general idea of the sequence of the story but if there’s a part that’s really grabbing me I’ll write that and set it aside to see if it matches up or find out what I can borrow from it when I’ve written the bridging material that leads up to that part.

🚿- genuinely anyplace. I don’t really have one specific place that I tend to think of fic ideas, but as I’m making dinner or showering or at the gym I’ll definitely think of stuff that would be fun to talk about or to address in the next chapter of whatever current WIP is on my mind.

🍎- there have been a couple of different fun things I’ve learned. Foremost has got to be that I started reading the Poppy War as (sorta) research for a Darklina fic (the commonalities being an exploration of what happens when you have an angry young girl who can wield virtually limitless power and is only hindered by her tenuous bonds to condescending authority figures) and that became. An entire separate obsession lol. I’ve also learned a fair bit about the state of Russia for my various Darklina AUs (Nothing is True and Everything is Possible by Peter Pomerantsev and the Romanovs by Simon Sebag Montefiore have been my favorites).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comment: Useful materials for reflection

Extract 1: Putin’s power is deeply connected to huge generational challenges that we vitally need to confront. First, don’t normalise colonial conquest. When some in the west urge Ukraine to “negotiate” with Russia and cede territory in order to gain “peace”, this is a green light for wannabe imperial powers anywhere to go forth, conquer and extract. Instead, ensure Ukraine receives all the military support it needs to liberate itself from Russian imperialism, and gains all the security guarantees necessary to prevent Russia ever invading again.

Extract 2: Second, push western companies to abandon Russia. Despite some companies leaving Russia at the start of the invasion, many more have remained, including well-known luxury brands. But there are also positive examples of civil society, workers and consumers pushing together for change.

Extract 3: All technology firms must be vigilant about the use of their products in crimes against humanity. From using kill switches to disable their technology, to actively tracking where their machines end up, there are numerous ways tech firms can take responsibility – and they must.

The issue here is not just with one or two companies, but with a whole ideology. For decades, Putin’s crimes were enabled by business and political actors who claimed that greater economic interconnection would lead to a more peaceful Russia.

Extract 4: The battle against Putin is also the battle against climate crisis. As Prof Alexander Etkind lays out in his new book, Russia Against Modernity, Putin’s economy has been up to two-thirds dependent on oil and gas exports, largely to Europe, and crucially through pipelines that cross Ukraine.

Etkind argues that Putin launched his invasion in part to control this flow. Moreover, he wanted to destabilise Europe, flooding it with refugees and instilling so much chaos and fear that Europe would be forced to abandon plans for net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Polls in Russia show that Russians tend to believe anyone who is in authority: truth is not a value in itself, but a subset of power.

[ … ]

If Putin can show he is powerful, through impunity globally and victory on the battlefield, then he is "believed". Defeat him on the battlefield, undermine his system in the courts, and his power to define reality will slip. It’s not just truth that leads to justice, it’s justice that leads to truth.

—Peter Pomerantsev at The Guardian.

The only sure way to undercut Putin in Russia is to defeat him.

Those Russian aircraft lost over Bryansk Oblast recently may have been shot down by Russia itself.

Ukraine Air Force says Russia’s air defenses downed their own two jets and three helicopters near Bryansk on May 13

If Russia is defeating itself then that doesn't bode well for Putin's future.

#invasion of ukraine#russia#vladimir putin#putin is losing credibility#lost aircraft#bryansk oblast#peter pomerantsev#россия#россия проигрывает войну#владимир путин#брянская область#путин хуйло#долой путина#правда#реальность#власть#справедливость#путин – это лжедмитрий iv а не пётр великий#вторгнення оркостану в україну#україна переможе#слава україні!#героям слава!

9 notes

·

View notes